Introduction

Paracetamol is known as N Acetyl P amino phenol (APAP) [

1]

. It has an analgesic, antipyretic, and very little peripheral anti-inflammatory activities. So it is prescribed mainly for the treatment of mild to moderate pain or fever [

2]

.

Researches working on paracetamol at its therapeutic doses failed to prove any hazards to the fetus in any trimester. Paracetamol is recorded as a category B medication (drugs with no risk in humans) as many authors stated that paracetamol as a single agent does not increase fetal risk in any trimester and is considered safe for use in pregnancy. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]

. On the other hand, there was suspicious evidence about paracetamol use because it crosses the placenta and it carries the risk of exposure to the growing fetus. Despite little studies on paracetamol abuse, growing evidence that chronic and maternal abuse of paracetamol was associated with hypertension, kidney, and lung disorders [

8,

9]

. An important epidemiological study demonstrated that excess maternal exposure to paracetamol was associated with behavioral changes in the children in form of less shyness [

10]

. Another work demonstrated the relation between excess maternal exposure to paracetamol and the development of attention defect hyperactivity in the siblings [

11]

.

In pregnancy, there is a significant increase in paracetamol clearance. Thus, the analgesic effect of paracetamol will decrease faster, and subsequently, there are needs to increase its dose [

2]

. Paracetamol toxicity can result from either an acute overdose or from chronic overuse [

12]

.

On the other hand, in early 2015, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put a report concerning pain medication during pregnancy. They found that the evidence as regarded as the possible connection with paracetamol and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were inconclusive [

13]

.

Paracetamol can cross the blood-brain barrier as it has a low molecular weight as well as low affinity to plasma protein [

14]

.

Neurobehavioral disorders are composed of many varieties of impairments found in association with other conditions causing brain disease or injury. These are characterized by interruption or disturbance in the achievement of skills in a variety of developmental fields, including motor, social, language, and cognition. Neurobehavioral disorders may appear as attention disorders, autistic spectrum disorders, or motor or sensory processing disorders [

15].

In the past decades, there was a rapid increase in the incidence of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, like attention-deficit /hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It has been suggested that this increase is not attributable only to changes in diagnostic procedures or parental awareness but also due to non-genetic risk factors acting during the prenatal period [

16]

. These increased rates of disorders may be due to the exposure to certain infections as rubella or to certain drugs like valproic acid, alcohol, or cocaine during pregnancy [

17].

BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) plays multiple roles in neuroprotection and it is a good indicator that reflects neurogenesis. It is related to many neurological disorders of heterogeneous pathogenesis. In animals, locomotor and behavior may be altered by the administration of therapeutic doses of paracetamol during early development. These alterations may be intervened by the interference of paracetamol with BDNF, neurotransmitter systems (including serotonergic, dopaminergic, adrenergic, as well as the endogenous endocannabinoid systems), or cyclooxygenase--2 [

18]

.

So, this work aims to evaluate the role of prenatal exposure of paracetamol by its therapeutic and high single doses on brains of 1-month-old rat offsprings. The study will combine behavior test parameters, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry to assess the possible experimental evidence of paracetamol-induced autistic-like models in animals. The positive control group will be the gestational exposure to the well-known toxic autistic model induced by valproic acid exposed mothers [

19]

. The current work will test the BDNF immune staining in the cerebellar and the hippocampus samples.

Materials & Method

This experimental study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University Mansoura City, Egypt, by code number (MS/17.05.09).

Material

Chemicals

Paracetamol: In the form of an Injectmol infusion bottle (100 ml) in a concentration of 10 mg/ml, was purchased from Pharco B International Egypt Company.

Sodium valporate: In the form of Depakine ampoule (4ml) in a concentration of 100 mg/1ml, was purchased from Sanofi Aventis France Company.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor antibody (BDNF) (N-20): SC-546: is a purified rabbit polyclonal IgG raised against a peptide mapping inside an interior part of BDNF of the human region used in rats before according to [

20]

. The ampoule contains 200 ug IgG diluted in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with <0.1% sodium azide and 0.1% gelatin. It was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. BDNF is a cellular stain looked at as a diffuse reaction dispersed through the nerve cell cytoplasm and not appears in the nucleus [

21]

.

Animals

This study was conducted on sixteen female pregnant albino Wistar rats in the first trimester obtained from the animal house of Medical Experimental Research Center (MERC), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University. They weigh about 150-200 g. Animals were retained in sanitary cages under normal laboratory situations including good lighting (12 hours’ light/dark cycles) and good aeration at a room temperature of 18–22 oC. They were fed the usual laboratory food and tap water.

Experimental Design

The experimental work was done in the Medical Experimental Research Centre (MERC), Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura City, Egypt.

Pregnant rats were divided into four groups; each group contains four rats:

Group I (negative control group): It received i.p injection of distilled water once daily for 9 days from embryonic day 13 to 21

Group II (positive control group): They received sodium valproate as 600 mg/Kg once i.p at embryonic day 13 [

19]

.

Group III: They were given a dose of paracetamol as 100 mg/Kg i.p daily for 9 days from embryonic day 13 to 21 (late 2nd trimester and 3rd trimester in which brain development occurs) [

22]

.

Group IV: They were given a high single dose of paracetamol as 300 mg/Kg i.p at embryonic day 13 [

23]

.

Methods

After one month of delivery of all pregnant rats, all offspring were examined by a trained observer for various behavioral parameters, assessed via open field test using ANY-box.

Then offspring were sacrificed; the brain was removed and examined histopathologically and immunohistochemically.

Neurobehavior Test Parameters

The ANY-box

® (Stoelting Company, USA), is a multi-configuration behavior apparatus designed to automate a range of standard neuro behavior test parameters. It consists of two components; an ANY-box base and core. The ANY-box base is attached to a camera to track the animals. The ANY-box core consists of the ANY-maze software (an elastic video tracking system planned to computerize the tests in locomotor experiments) and an ANY-maze interface [

24]

.

Open field test is the neurobehavior test parameter that used in this study, as it is broadly used to assess the locomotor parameters and locomotor activity in the offspring of all experimental rat groups at age of one month [

25]

.

This examination was done in a place completely isolated from the external noises. In the center of the apparatus, each animal was put separately and observed for five minutes. The apparatus floor was cleaned between each rat using 70% ethyl alcohol. Each rat trial was recorded using the camera which was placed above the apparatus.

Open field test measured neurobehavioral function for each animal by the following parameters:

Total distance traveled (in centimeters).

Average speed (centimeters per second).

Total time being mobile (in seconds).

Numbers of the mid-zone cross (line crossing).

Immobile, freezing, and mobile episodes.

Clockwise and anticlockwise rotations.

Histopathological Evaluation

After the neurobehavioral test parameters were done and under deep anesthesia, offspring were sacrificed. The brain was dissected, treated, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin [

26]

. Hippocampus and cerebellum were examined microscopically and photographed.

Immunohistochemical Study

Paraffin-embedded sections were immunohistochemically stained with BDNF antibody at dilution of 1/100.

According to the manufacturer, sections were put on positive slides then immunostained by avidin-biotin technique. The sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then washed by tap water. Blocking of endogenous peroxidase action was done by embedding the section in 0.01% H2O2 then the antigenic site was unmasked by putting sections in 0.01M citrate buffer (pH 6) for 30 minutes. To neglect nonspecific background, the sections were incubated for 20 minutes in diluted normal rabbit serum then incubated in the diluted primary antibody at 1/100 dilution (BDNF: rabbit polyclonal antibody) for two hours. After that, incubation of the slides using the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) substrate was done for 1 hour than in peroxidase substrate solution for 6-10 minutes. Lastly, a counterstain by hematoxylin was done. The primary antibody was changed by phosphate buffer saline for a negative control slide. [

27]

.

Digital Morphometric Study

Slides were photographed using Olympus® digital camera (E24-10 megapixel- China) mounted on Olympus® microscope (Olympus ® model CX31RTSF, Tokyo, Japan) with1/2 X photo adaptor, via 40 X objective lens. The obtained photos were examined on Intel® Core I3® based computer by Video Test Morphology® software (Saint Petersburg- Russia) with a specific built-in routine for the study of area percentage of BDNF positive expression.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were analyzed via the computerized statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 16. Normally distributed quantitative data were described as mean and standard deviation. Quantitative data that was not normally distributed was described as median and range (minimum-maximum). Statistically, a significant difference was considered at p-value ≤ 0.05 and highly statistically significant at P value < 0.001. Therefore, the following tests were used:

Kruskal Walis test: to match quantitative data that was not normally distributed between more than two groups.

Mann Whitney test: to match quantitative data that was not normally distributed between two groups.

One-way ANOVA: was used to match the normally distributed quantitative data between three or more groups followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons.

Results

Neurobehavior Test Parameters

Table 1 showed that the offspring of group II& IV had significantly lower mobility episodes when matched with offspring of group I (p1=0.009, p3=0.05 respectively) and had no significant difference when matched with offspring of group III (p4=0.07, p6=0.2).

However, offspring of group II& IV had higher significant increased immobility (p1=0.001, p3=0.003) and freezing episodes (p1=0.01, p3=0.01) as compared with offspring of group I. And had higher significant increased immobility (p4=0.001, p6=0.006) and freezing episodes (p4=0.03, p6=0.02) as compared with offspring of group III respectively.

No statistically significant difference was detected between the offspring of group II and of group IV (p5=0.2, 0.09, 0.9, 0.8) regarding these neurobehavioral test parameters (mobile, immobile, and freezing episodes as well as total mobility time respectively).

Also, no statistically significant difference was detected between the offspring of group I and group III (p2=0.9, 0.9, 0.9, 0.2) regarding these neurobehavioral test parameters (mobile, immobile and freezing episodes as well as total mobility time respectively).

Table 2 showed significant lower distance travelled (p1=0.03, p3=0.02), average speeds (p1=0.001, p3=0.001), line crossing (p1< 0.001) and clock wise rotations (p1< 0.001, p3=0.005) among offspring of group II& IV respectively when matched with that of group I.

Also, higher significant increased distance travelled (p4=0.03, p6=0.02), average speeds (p4=0.007, p6=0.01), line crossing (p4=0.001, p6=0.002) and clockwise rotations (p4=0.001, p6=0.002) were detected among offspring of group II& IV respectively with that group III.

No statistically significant difference was detected between the offspring of group II and of group IV (p5=0.9, 0.5, 0.6, 0.07, 0.1) regarding the neurobehavioral test parameters (distance traveled, average speed, line crossing, clockwise rotation and anticlockwise rotations of the animal body respectively).

Also, no statistically significant difference was detected between the offspring of group I and of group III (p2=0.9, 0.6, 0.9, 0.3, 0.2) regarding the neurobehavioral test parameters (distance traveled, average speed, line crossing, clockwise rotation and anticlockwise rotations of the animal body respectively).

Histopathological Evaluation

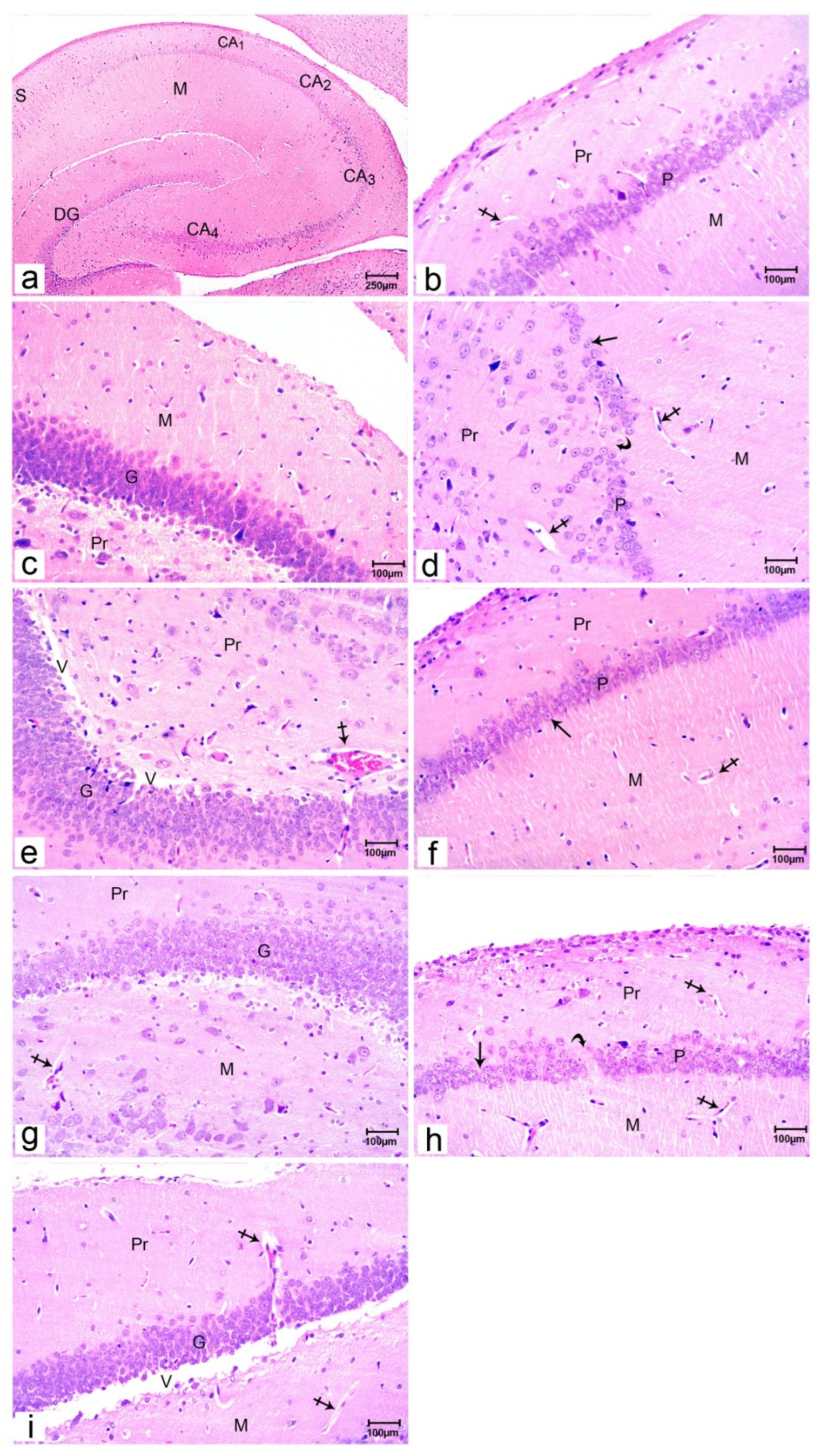

Hippocampus

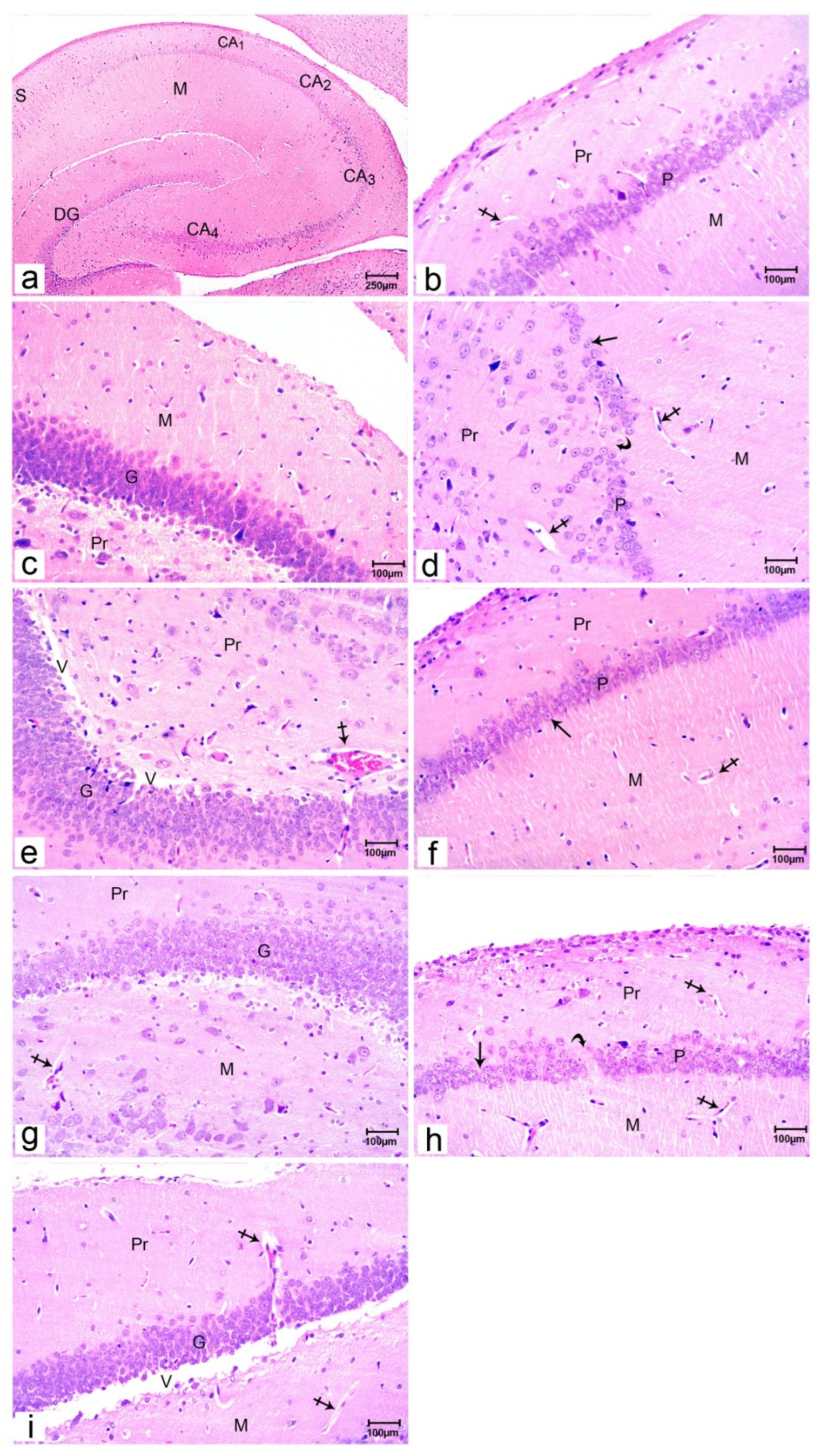

Normal histological design of the hippocampus of group I offspring was noticed by light microscopic examination of sections stained by H&E. It was formed of the hippocampus proper, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. The hippocampus proper made of cornu ammonia (CA) which composed of CA1, CA2, CA3 & CA4 parts, and it was continued as a subiculum. CA4 was surrounded by the dark C shaped dentate gyrus (

Figure 1a). CA1 was composed of molecular, pyramidal, and polymorphic regions. The pyramidal layer was made of 4-5 dense layers of small pyramidal cells with vesicular nuclei. The molecular and polymorphic layers were relatively cell-free layers and contained blood vessels (

Figure 1b). The dentate gyrus is formed of molecular, granular, and polymorphic areas. The granular one instituted the principal layer. It had the extreme cell density formed of compact columns of rounded granule cells with vesicular nuclei. It contained blood vessels. The polymorphic layer had some pyramidal cells and blood vessels (

Figure 1c).

A study of H&E stained sections of the hippocampus of group II offspring showed distinct histological changes. The pyramidal layer in the CA1 region showed a marked decrease in the small pyramidal cell layer with some cell loss (Figure 1d). As regards the dentate gyrus, there was an obvious reduction in the size of the granular cell layer with marked vacuolation. Molecular & polymorphic layers revealed widened and congested blood capillaries (Figure 1e).

A study of H&E stained sections of the hippocampus of group III offspring showed mostly the same general picture of the hippocampi as regard CA1 (Figure 1f) and dentate gyrus (Figure 1g) as detected in the offspring of group 1.

A study of H&E stained sections of the hippocampus of group IV offspring showed distinct histological changes like that detected in the offspring of group II in CA1 (Figure 1h), as well as in dentate gyrus (Figure 1i).

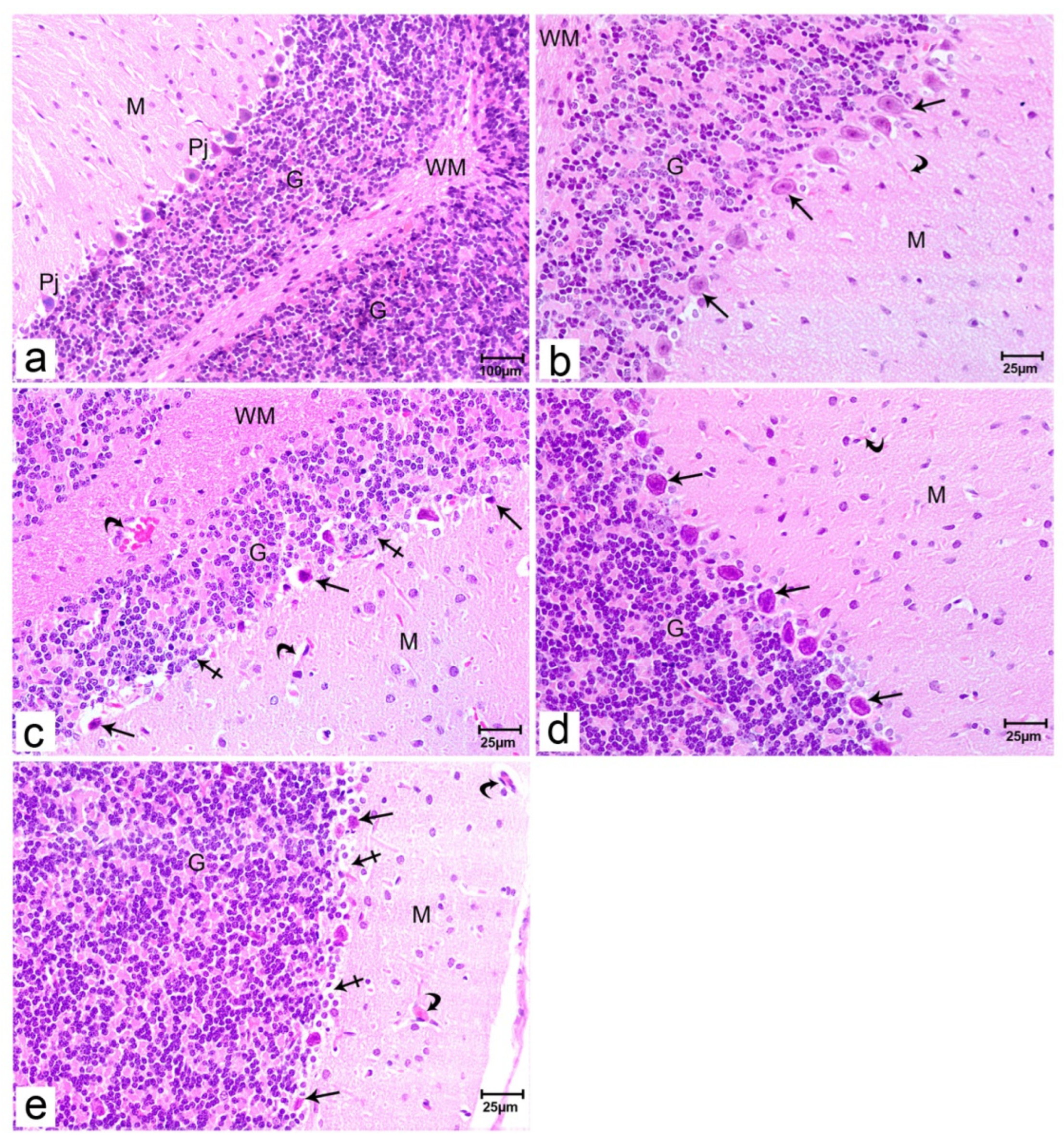

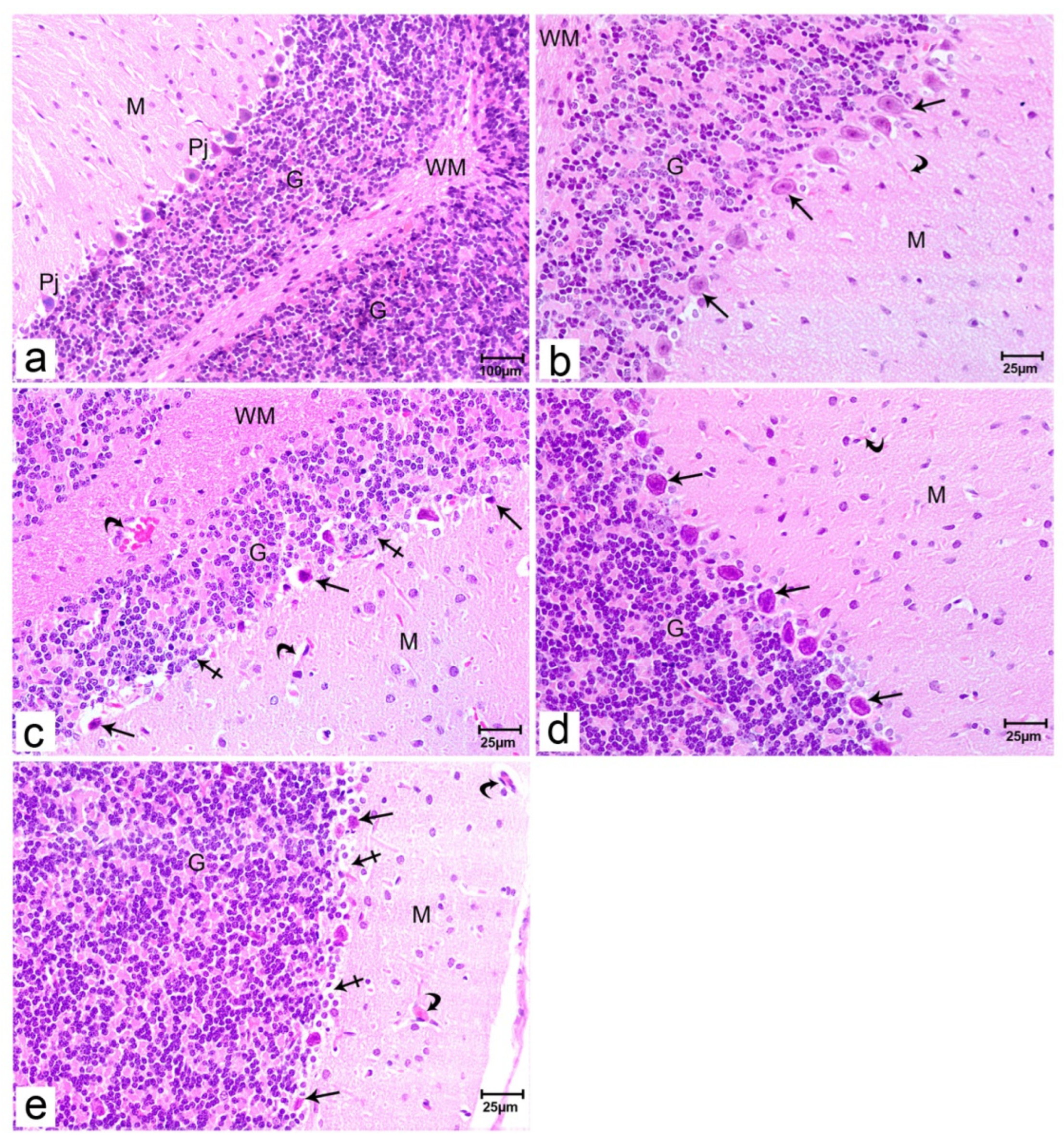

Cerebellum

A study of H&E stained sections of the cerebellum of group I offspring showed the usual cerebellar structural design. The cerebellar cortex is made of three distinct layers: outer molecular, middle Purkinje, and inner granular layers. The granular cell layer was overcrowded with cells; differs from the molecular layer which is considered cells free (Figure 2a). Purkinje layer was formed of Purkinje cells arranged in one row between molecular and granular layers. Those cells had large, pyriform shaped cell bodies, centrally located vesicular nuclei, and apical dendrites extending upward into the molecular layer (Figure 2b). The granular layer was composed of numerous small closely packed granular cells having dark spherical nuclei (Figure 2b).

A study of H&E stained sections of the cerebellum of group II offspring showed distinct histological changes. Some Purkinje cells became smaller in size, had pyknotic nuclei, and vacuolated cytoplasm. Widened congested blood vessels were seen in the molecular layer (Figure 2c).

The microscopic examination of specimens of the offspring of group III revealed mostly the same general picture of the cerebellum as in the offspring of group 1 (Figure 2d).

Microscopic examination of specimens of the offspring of group IV revealed marked histological changes like that detected in the offspring of group II (

Figure 2e).

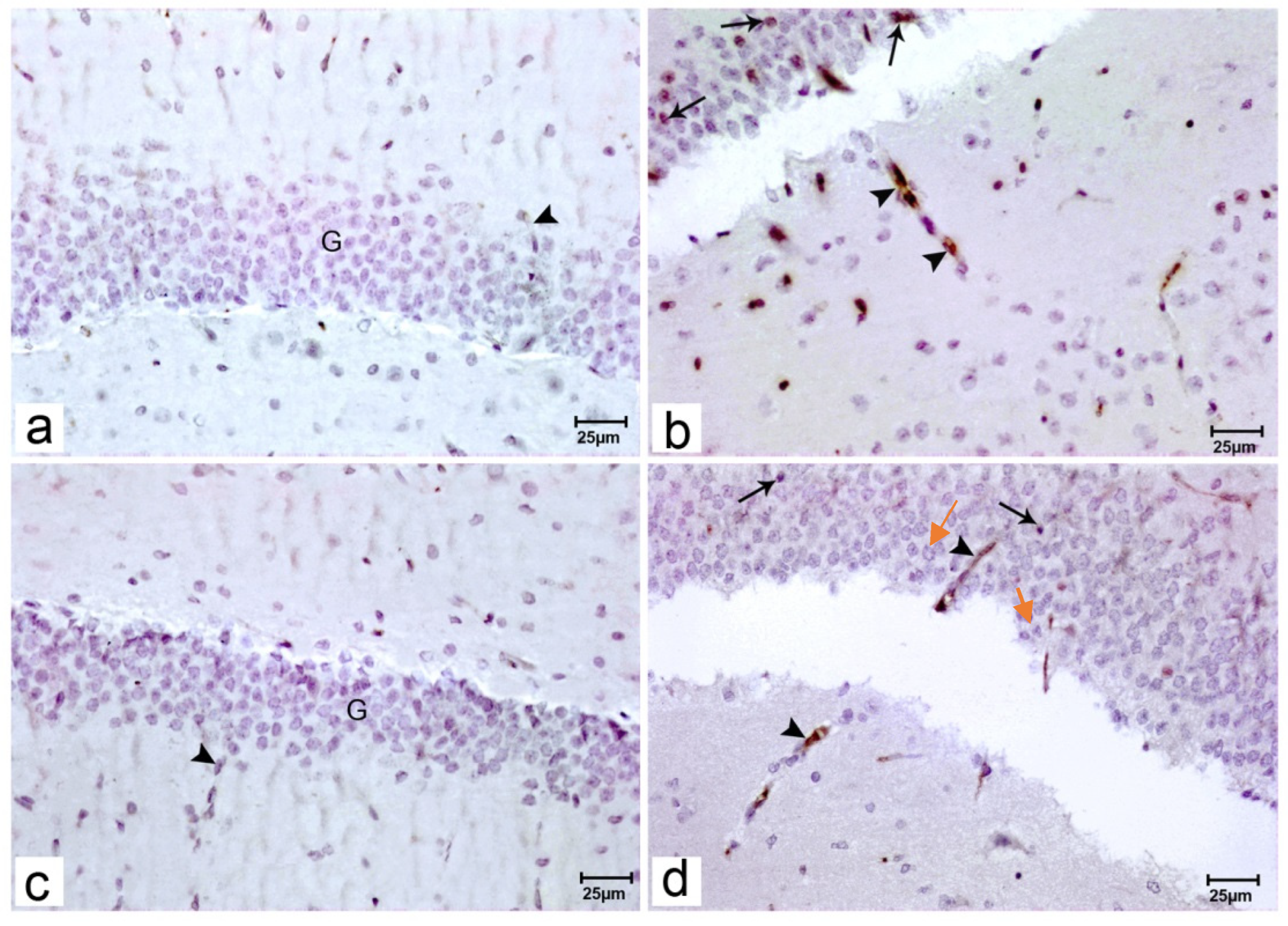

Immunohistochemistry Evaluation

Immunostained sections of the hippocampus of the offspring of group I& III revealed no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the granular cells or around blood vessels (Figure 3a, 3c respectively).

Immunostained sections of the hippocampus of the offspring of group II revealed focal increased BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells and around blood vessels (Figure 3b, 3d respectively).

Immunostained sections of the hippocampus of the offspring of group IV revealed mild focal positivity for BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells pointed by red arrows and around blood vessels pointed by black arrows (

Figure 3d respectively).

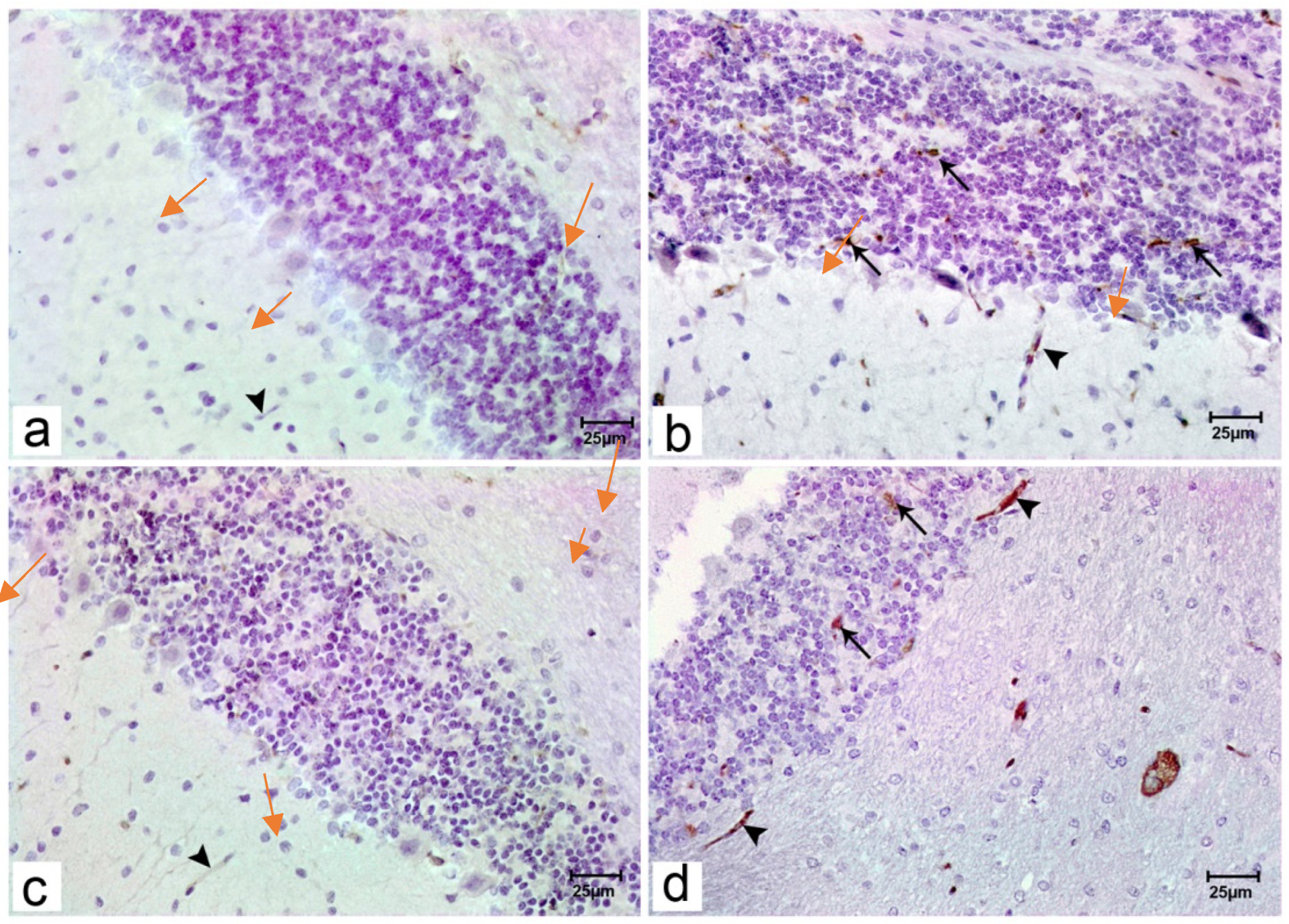

Immunostained sections of the cerebellum of the offspring of group I& III revealed no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje cells or around blood vessels (Figure 4a, 4c respectively).

Immunostained sections of the cerebellum of offspring of group II& IV revealed no BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje cells pointed by red arrows in comparison of focal positivity for granular cells and blood vessels pointed by black arrows (

Figure 4b, 4d respectively).

Statistical comparison between percentage areas of BDNF immunohistochemically stained among the examined groups showing the area %of BDNF immunohistochemically stained is significantly higher among offspring of group II& IV when compared with offspring of group I (p

1 ≤ 0.001, p

3 ≤ 0.001, respectively) or with that of group III (p

4 ≤ 0.001, p

6 ≤ 0.001). However, the % area of BDNF immunoreaction shows no statistical difference among the offspring of group IV when compared with that of group II (p

5= 0.9) and no statistical difference between % offspring of group III and that of group I (p

2= 0.2) (

Table 3).

Discussion

The present study was done to assess the prenatal exposure to paracetamol by two chronic and high single doses aiming to model gestational abuse and toxicity of paracetamol. In the present study, the neurobehavioral test parameters in the offspring of group II& IV showed significantly lower distance traveled, average speed, mobile episodes, line crossing, and clockwise rotations when compared either with the offspring of group I or with group III. At the same time, immobile and freezing episodes were significantly higher among the offspring of group II& IV when compared with the offspring of group I& III. Also, no statistical difference was found neither between the offspring of groups II& IV nor between offspring of groups I and III according to these tests.

The histopathological examination correlated with the behavior test parameters in both the valproic group and the high dose paracetamol variety expressing reductions in the pyramidal and the granular cells in hippocampus samples. A similar adverse response has been noticed in the cerebellar samples regarding the Purkinje cell population. These pathological findings reflected cell injury and apoptotic responses due to the toxicity model. It is suggested that autistic response in the animals was related to loss of function. The BDNF immunohistochemistry showed focal positive cells in the granular cells in the hippocampus samples of valproic autistic model and to less extend in the high dose paracetamol group. The current work demonstrated apoptosis of the Purkinje cell population and possible excitation of the granular cell lines despite associated apoptosis. These findings were related to the focal expression of the BDNF in the granular cells. It was suggested that autism pathogenesis was correlated with increase cerebellar excitability [

28,

29]

. The hyperactive pyramidal cells, proposed by focal BDNF increased expression, may correspond to the hyperactive child, and contributes to ADHD disorders. It was reported that dose-dependent paracetamol exposure improved water maze (a neurobehavior test parameters), while high dose caused spatial memory deficits in the water maze. Also, proposed that usage of paracetamol during pregnancy was interrelated with neurodevelopmental disorders like hyperkinetic disorder, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [

31,

32]

.

The high single dose paracetamol demonstrated valproic-like effects suggesting a similar mechanism. The current study proposed the direct effect of valproic and paracetamol on the animal brains. A similar concept was adopted by other work as paracetamol toxic hepatic dose kill the animal by hepatic failure before affecting the brain. So the released metabolic free radicals are not likely the cause of the current model cell injury [

33]

.

The current work suggested that high single doses of both valproic and paracetamol-induced direct process that could be contributed to the development of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism and hyperactivity [

34,

35]

. The focal BDNF suggests neurogenesis and stem cell activates to overcome the pathology [

36]

.

Met analysis studies demonstrated a high serum level of BDNF in autism unlike schizophrenia and it is noticed that the BDNF is not only a response but it is involved in the disorder pathogenesis [

38,

39]

.

Experimental work examined prenatal long-term exposure (for more than 28 days) of paracetamol at its therapeutic doses on neurodevelopmental outcomes in children at age of 3month. They found that these children had poorer gross motor development and communication skills and also exhibited more hyperactivity [

40]

. Moreover, it was reported that maternal therapeutic dose of paracetamol during pregnancy was linked with high hazard for hyperkinetic disorders and ADHD similar behaviors [

32,

41]

.

Hippocampus is known to be very important for standard development in the child regarding language syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, and the ability for creativity and behavior. Autism was suggested to be the developing disorder of hippocampal dysfunction [

42]

.

Despite that the model used in the study does not fit completely with the routine use of paracetamol in clinical practice, the results strongly correlated with the pathology discovered in the animals. These findings in combination raise the questions about the use of paracetamol in pregnancy. It is suspected that the use of paracetamol augmented by other mixtures or associated inflammatory factors may produce unpredicted autistic risk.

One limitation of the study is that we did not focus on the cortical pathology however, a previous study showed similar cell injury and apoptosis in the cortex as a direct effect of paracetamol in a dose-dependent manner [

33]

.

Conclusions

From the present work, it can be concluded that prenatal exposure to paracetamol in its high doses can induce disturbances in the neurobehavioral test parameters and histopathological changes in the hippocampus and the cerebellum in rats that is too close to the autistic and hyperactivity disorders in humans. Paracetamol abuse induces these adverse effects by mechanisms that need further studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Mohamed Salama, Assistant Professor of Forensic Medicine and Clinical Toxicology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University and director of the Medical Experimental Research Center (MERC) Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University. We also are grateful to Dr. Doaa Ghorab, Assistant Professor of Pathology Department, Mansoura University for her valuable support regarding the help in the assessment of the pathology slides.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies of the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Ethical Approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All rats’ experimental protocols and procedures were approved by the institutional review board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine, the University of Mansoura by a code number: (MS/17.05.09).

References

- Hajian, R.; Afshari, N. The Spectrophotometric Multicomponent Analysis of a Ternary Mixture of Ibuprofen, Caffeine and Paracetamol by the Combination of Double Divisor-Ratio Spectra Derivative and H-Point Standard Addition Method. E-Journal Chem. 2012, 9, 1153–1164. [CrossRef]

- Allegaert, K.; Anker, J.N.v.D. Perinatal and neonatal use of paracetamol for pain relief. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 22, 308–313. [CrossRef]

- Hughey MJ. 2001 Operational Medicine 2001, Health Care in Military Settings ed., Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Department of the Navy, NAVMED P-5139, May 1, 2001.

- Rebordosa, C.; Kogevinas, M.; Bech, B.H.; Sørensen, H.T.; Olsen, J. Use of acetaminophen during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Leuk. Res. 2009, 38, 706–714. [CrossRef]

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, Lee PC, Olsen J. 2014 Paracetamol use during pregnancy, locomotor problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. JAMA Pediatr; 168, 313–20.

- Servey J, Chang J 2014: Over-the-Counter Medications in Pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 15;90(8):548-555.

- Malhotra S, Khanna S. 2016 Safety of analgesics in pregnancy. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 3(1),208-212.

- Thiele, K.; Kessler, T.; Arck, P.; Erhardt, A.; Tiegs, G. Acetaminophen and pregnancy: short- and long-term consequences for mother and child. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 97, 128–139. [CrossRef]

- McCrae, J. C., Morrison, E. E., MacIntyre, I. M., Dear, J. W., & Webb, D. J. (2018). Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol - a review. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 84(10), 2218–2230.

- Trønnes, J.N.; Wood, M.; Lupattelli, A.; Ystrom, E.; Nordeng, H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preschool-aged children. Paediatr. Périnat. Epidemiology 2019, 34, 247–256. [CrossRef]

- Ystrom, E.; Gustavson, K.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Knudsen, G.P.; Magnus, P.; Susser, E.; Davey Smith, G.; Stoltenberg, C.; Surén, P.; Håberg, S.E.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk of ADHD. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20163840. [CrossRef]

- Serper M, Wolf MS, Parikh NA, Tillman H, Lee WM, Ganger DR. 2016 Risk factors, clinical presentation, and outcomes in overdose with paracetamol alone or with combination products: results from the acute liver failure study group. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 50(1),85-91.

- Bauer, A.Z.; Kriebel, D.; Herbert, M.R.; Bornehag, C.-G.; Swan, S.H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A review. Horm. Behav. 2018, 101, 125–147. [CrossRef]

- Nambiar NJ. 2012 Management of Paracetamol Poisoning: The Old and the New. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research, 6(6),1101-1104.

- Capone G, Goyal P, Ares W, Lannigan E. 2006 Locomotor disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 142(3),158-172.

- Lyall, K.; Schmidt, R.J.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Leuk. Res. 2014, 43, 443–464. [CrossRef]

- Ornoy, A.; Weinstein-Fudim, L.; Ergaz, Z. Prenatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 56, 155–169. [CrossRef]

- de Fays, L.; Van Malderen, K.; De Smet, K.; Sawchik, J.; Verlinden, V.; Hamdani, J.; Dogné, J.; Dan, B. Use of paracetamol during pregnancy and child neurological development. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 718–724. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Turczak, J.; Przewłocki, R. Environmental Enrichment Reverses Behavioral Alterations in Rats Prenatally Exposed to Valproic Acid: Issues for a Therapeutic Approach in Autism. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 31, 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Sui, L.; Wang, Y.; Ju, L.-H.; Chen, M. Epigenetic regulation of reelin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor genes in long-term potentiation in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2012, 97, 425–440. [CrossRef]

- Conner, J.M.; Lauterborn, J.C.; Yan, Q.; Gall, C.M.; Varon, S. Distribution of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Protein and mRNA in the Normal Adult Rat CNS: Evidence for Anterograde Axonal Transport. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 2295–2313. [CrossRef]

- Mojarad N, Yousefifard M, Janzadeh A, Damani, S, Golab F, Nasirinezhad F. 2016 Comparison of the antinociceptive effect of intrathecal versus intraperitoneal injection of paracetamol in neuropathic pain condition. Journal of Medical Physiology, 1(1),10-16.

- Samuel SA, Francis AO, Ayomide O, Onyinyechi UO. 2015 Effects of paracetamol-induced liver damage on some hematological parameters: red blood cell (RBC) count, white blood cell (WBC) count, and packed cell volume (PCV) in wistar rats of either sex. Indo American Journal Pharmacology Research, 5(7),2593-2599.

- Ahmed D, Abdel-Rahman RH, Salama M, El-Zalabany LM, El-Harouny MA. 2017 Malathion neurotoxic effects on dopaminergic system in mice. Journal of Biomedical Science, 6(4),1-30.

- Narita, M.; Oyabu, A.; Imura, Y.; Kamada, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Tano, K.; Uchida, A.; Narita, N. Nonexploratory movement and behavioral alterations in a thalidomide or valproic acid-induced autism model rat. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 66, 2–6. [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, K.S.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 8th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008.

- Mooney, S.; Miller, M. Role of neurotrophins on postnatal neurogenesis in the thalamus: prenatal exposure to ethanol. Neuroscience 2011, 179, 256–266. [CrossRef]

- D'ANgelo, E. 2018 Physiology of the cerebellum. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;154:85-108.

- Ingram, J.L.; Peckham, S.M.; Tisdale, B.; Rodier, P.M. Prenatal exposure of rats to valproic acid reproduces the cerebellar anomalies associated with autism. Neurotoxicology Teratol. 2000, 22, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- Medin, T.; Jensen, V.; Skare, Ø.; Storm-Mathisen, J.; Hvalby, Ø.; Bergersen, L.H. Altered α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor function and expression in hippocampus in a rat model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 360, 209–215. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Sato, T.; Irifune, M.; Tanaka, K.-I.; Nakamura, N.; Nishikawa, T. Effect of acetaminophen, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, on Morris water maze task performance in mice. J. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 21, 757–767. [CrossRef]

- Liew Z, Ritz B, Virk J, Olsen J. 2016 Maternal use of paracetamol during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders in childhood: AD anish national birth cohort study. Autism Research, 9(9),951-958.

- Posadas I, Santos P, Blanco A, Muñoz-Fernández M, Ceña V. 2010 Paracetamol induces apoptosis in rat cortical neurons”. PloS one, 5(12):e15360.

- Evason K, Collins JJ, Huang C, Hughes S, Kornfeld K. Valproic acid extends Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. Aging Cell. 2008;7(3):305-317.

- Nicolini, C.; Ahn, Y.; Michalski, B.; Rho, J.M.; Fahnestock, M. Decreased mTOR signaling pathway in human idiopathic autism and in rats exposed to valproic acid. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 3–3. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, J.F.; Zanoni, M.B.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 363. [CrossRef]

- Armeanu, R.; Mokkonen, M.; Crespi, B. Meta-Analysis of BDNF Levels in Autism. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 37, 949–954. [CrossRef]

- Halepoto, D.M.; Bashir, S.; A L-Ayadhi, L. Possible role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in autism spectrum disorder: current status. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan : JCPSP 2014, 24, 274–8.

- Khani-Habibabadi, F.; Askari, S.; Zahiri, J.; Javan, M.; Behmanesh, M. Novel BDNF-regulatory microRNAs in neurodegenerative disorders pathogenesis: An in silico study. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 83, 107153. [CrossRef]

- Brandlistuen, R.E.; Ystrom, E.; Nulman, I.; Koren, G.; Nordeng, H. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. Leuk. Res. 2013, 42, 1702–1713. [CrossRef]

- Avella-Garcia, C.B.; Julvez, J.; Fortuny, J.; Rebordosa, C.; García-Esteban, R.; Galán, I.R.; Tardón, A.; Rodríguez-Bernal, C.L.; Iñiguez, C.; Andiarena, A.; et al. Acetaminophen use in pregnancy and neurodevelopment: attention function and autism spectrum symptoms. Leuk. Res. 2016, 45, dyw115–1996. [CrossRef]

- DeLong, G.R. Autism, amnesia, hippocampus, and learning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1992, 16, 63–70. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of rat offspring’s hippocampus sections stained with H&E.; Offspring of group I (a–c) showing all parts of the hippocampus; hippocampus proper (CA1, CA2, CA3 & CA4 parts), dentate gyrus (DG) and subiculum (S). CA1 composed of molecular (M), pyramidal (P), and polymorphic (Pr) regions, the molecular and polymorphic layers contained blood vessels (crossed arrow), the dentate gyrus composed of the molecular layer (M), granular layer (G) and polymorphic layer (Pr). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group II (d& e) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with a reduction in small pyramidal cell layer (arrow) with some cell loss (curved arrow), reduction in layers of granule cells of the granular layer (G) and marked vacuolation (V), dilated and congested blood capillaries (crossed arrow) are noticed in both molecular (M), and polymorphic layers (Pr). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group III (f& g) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with 4-5 compact layers of small pyramidal cells most with vesicular nuclei (arrow), the molecular layer (M) and polymorphic layer (Pr) has blood capillaries (crossed arrow). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group IV (h& i) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with a reduction in small pyramidal cell layer (arrow) with some cell loss (curved arrow), reduction in layers of granule cells of the granular layer (G) and marked vacuolation (V), dilated and congested blood capillaries (crossed arrow) are noticed in both molecular (M), and polymorphic layers (Pr). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of rat offspring’s hippocampus sections stained with H&E.; Offspring of group I (a–c) showing all parts of the hippocampus; hippocampus proper (CA1, CA2, CA3 & CA4 parts), dentate gyrus (DG) and subiculum (S). CA1 composed of molecular (M), pyramidal (P), and polymorphic (Pr) regions, the molecular and polymorphic layers contained blood vessels (crossed arrow), the dentate gyrus composed of the molecular layer (M), granular layer (G) and polymorphic layer (Pr). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group II (d& e) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with a reduction in small pyramidal cell layer (arrow) with some cell loss (curved arrow), reduction in layers of granule cells of the granular layer (G) and marked vacuolation (V), dilated and congested blood capillaries (crossed arrow) are noticed in both molecular (M), and polymorphic layers (Pr). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group III (f& g) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with 4-5 compact layers of small pyramidal cells most with vesicular nuclei (arrow), the molecular layer (M) and polymorphic layer (Pr) has blood capillaries (crossed arrow). Hippocampal sections of offspring of group IV (h& i) showing the pyramidal layer (P) with a reduction in small pyramidal cell layer (arrow) with some cell loss (curved arrow), reduction in layers of granule cells of the granular layer (G) and marked vacuolation (V), dilated and congested blood capillaries (crossed arrow) are noticed in both molecular (M), and polymorphic layers (Pr). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of rat offspring’s cerebellar sections stained with H&E. Offspring of group I (a& b) showing the 3 regions of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and Purkinje cell layer (Pj); the central medullary region made up of white matter (WM). Blood vessels are seen (curved arrow). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group II (c) showing the different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and some Purkinje cells layer became smaller in size have pyknotic nuclei (arrows) and vacuolated cytoplasm with some cell loss (crossed arrow). Widened and congested blood vessels (curved arrow) are seen in the molecular layer (M) and in white matter (WM). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group III (d) showing a normal architecture of the three different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), in-between them single layer of Purkinje cells (arrows) are seen. Blood vessels are seen in the molecular layer (curved arrow). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group IV (e) showing the different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and Purkinje cells layer between them with shrinkage in the size of some of it with pyknotic nuclei (arrows) and some cell loss (crossed arrow). Widened blood vessels are also seen in the molecular layer (curved arrow). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of rat offspring’s cerebellar sections stained with H&E. Offspring of group I (a& b) showing the 3 regions of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and Purkinje cell layer (Pj); the central medullary region made up of white matter (WM). Blood vessels are seen (curved arrow). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group II (c) showing the different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and some Purkinje cells layer became smaller in size have pyknotic nuclei (arrows) and vacuolated cytoplasm with some cell loss (crossed arrow). Widened and congested blood vessels (curved arrow) are seen in the molecular layer (M) and in white matter (WM). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group III (d) showing a normal architecture of the three different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), in-between them single layer of Purkinje cells (arrows) are seen. Blood vessels are seen in the molecular layer (curved arrow). Cerebellar sections of offspring of group IV (e) showing the different areas of the cerebellum; outer molecular (M), inner granular cell layer (G), and Purkinje cells layer between them with shrinkage in the size of some of it with pyknotic nuclei (arrows) and some cell loss (crossed arrow). Widened blood vessels are also seen in the molecular layer (curved arrow). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of hippocampal sections of the offspring of the studied groups stained with immunohistochemical staining for BDNF. Immunostained sections of the offspring of group I (a) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (G) or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group II (b) showing increased BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (arrows) and around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group III (c) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the granule cells (G) around blood vessels (arrowhead). cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group IV (d) showing mild BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (red arrows) and around blood vessels (black arrowhead). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph of hippocampal sections of the offspring of the studied groups stained with immunohistochemical staining for BDNF. Immunostained sections of the offspring of group I (a) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (G) or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group II (b) showing increased BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (arrows) and around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group III (c) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the granule cells (G) around blood vessels (arrowhead). cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group IV (d) showing mild BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the granular cells (red arrows) and around blood vessels (black arrowhead). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of cerebellar sections of offspring of the studied groups stained with immunohistochemical staining for BDNF. Immunostained sections of the offspring of group I (a) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje and granule cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of offspring of group II (b) showing no BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje pointed by red arrows in comparison to focal strong positivity of granule cells (black arrows) and around blood vessels (black arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group III (c) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje and granule cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of offspring of group IV (d) showing no BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje pointed by red arrows but granule cells (arrows) and blood vessels showed mild focal positivity (arrowhead). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of cerebellar sections of offspring of the studied groups stained with immunohistochemical staining for BDNF. Immunostained sections of the offspring of group I (a) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje and granule cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of offspring of group II (b) showing no BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje pointed by red arrows in comparison to focal strong positivity of granule cells (black arrows) and around blood vessels (black arrowhead). Immunostained sections of the offspring of group III (c) showing no reaction of BDNF in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje and granule cells or around blood vessels (arrowhead). Immunostained sections of offspring of group IV (d) showing no BDNF reactions in the cytoplasm of the Purkinje pointed by red arrows but granule cells (arrows) and blood vessels showed mild focal positivity (arrowhead). (Resolution of photo: 300 Pixel/inch).

Table 1.

Behavior test parameters (mobile, immobile, freezing episodes, and total time mobile) among offspring of studied rats.

Table 1.

Behavior test parameters (mobile, immobile, freezing episodes, and total time mobile) among offspring of studied rats.

| Group |

Mobile episodes

Median (min-max) |

Immobile episodes

Median (min-max) |

Freezing episodes

Median (min-max) |

Total time mobile (sec)

Median (min-max) |

| Group I (n=8) |

8.5(5-11) |

7(3-9) |

0.5(0-2) |

75.7(36.3-96) |

| Group II (n=7) |

5(0-7) |

10(9-13) |

2(1-2) |

81(1.1-120) |

| Group III (n=7) |

9(1-11) |

7(1-9) |

1(0-2) |

60.3(2.6-79.5) |

| Group IV (n=8) |

6.5(1-8) |

9(8-10) |

2(1-2) |

88.4(12.8-96.5) |

| p value |

|

|

|

|

| p1 value |

0.009* |

0.001* |

0.01* |

0.7 |

| p2 value |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

| p3 value |

0.05* |

0.003* |

0.01* |

0.2 |

| p4 value |

0.07 |

0.001* |

0.03* |

0.2 |

| p5 value |

0.2 |

0.09 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

| p6 value |

0.2 |

0.006* |

0.02* |

0.1 |

Table 2.

Behavior test parameters (distance traveled, average speeds, line crossing, and rotations) among offspring of studied rats.

Table 2.

Behavior test parameters (distance traveled, average speeds, line crossing, and rotations) among offspring of studied rats.

| Group |

Distance traveled

(cm)

Median

(min-max) |

Average speeds

(cm/s)

Median

(min-max) |

Line crossing

Median (min-max) |

Clockwise rotations

Median (min-max) |

Anticlockwise rotations of animal body

Median (min-max) |

| Group I(n=8) |

8.6

(4-11) |

0.08

(0.04-0.09) |

21.5

(20-36) |

3

(3-4) |

4.5

(2-7) |

| Group II(n=7) |

3.5

(0-7.5) |

0.03

(0-0.05) |

14

(0-15) |

1

(0-2) |

3

(0-6) |

| Group III(n=7) |

9.5

(3.7-11.8) |

0.08

(0.03-0.09) |

22

(15-34) |

4

(3-4) |

3

(0-5) |

| Group IV(n=8) |

3.6

(0.03-6.8) |

0.03

(0-0.06) |

12.5

(5-20) |

2

(1-3) |

6

(1-10) |

| p value |

|

|

|

|

|

| p1 value |

0.03* |

0.001* |

< 0.001* |

< 0.001* |

0.2 |

| p2 value |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

| p3 value |

0.02* |

0.002* |

0.001* |

0.005* |

0.5 |

| p4 value |

0.03* |

0.007* |

0.001* |

0.001* |

0.9 |

| p5 value |

0.9 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.07 |

0.1 |

| p6 value |

0.02* |

0.01* |

0.002* |

0.002* |

0.2 |

Table 3.

The percentage area of BDNF immunohistochemically stained in the offspring of studied groups.

Table 3.

The percentage area of BDNF immunohistochemically stained in the offspring of studied groups.

| |

offspring of GI (M±SD) |

offspring of GII (M±SD) |

offspring of GIII (M±SD) |

offspring of GIV (M±SD) |

| % area of BDNF |

0.047± 0.001 |

0.708± 0.009

|

0.051±0.002 |

0.701± 0.008

|

| P1≤ 0.001 |

P2= 0.2 |

P3≤ 0.001 |

P4≤ 0.001 |

P5= 0.9 |

| P6≤ 0.001 |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).