1. Introduction

Black holes remain among the most enigmatic objects in modern physics, acting as both astrophysical laboratories and theoretical frontiers for our understanding of gravity, quantum mechanics, and information theory. At the classical level, black holes are elegantly described by the no-hair theorem, which states that they can be fully characterized by only three macroscopic quantities: mass, charge, and spin. However, advances in observational astronomy and quantum gravity suggest that this paradigm may be incomplete, motivating new efforts to probe hidden structures sometimes referred to as quantum hair that could encode information beyond the classical description.

Recent missions such as Gaia, with its third data release (DR3), and gravitational wave detections by the LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA collaboration, have transformed black hole research from a largely theoretical pursuit into an increasingly data-driven science. Gaia’s high-precision astrometry enables the detection of subtle astrometric jitter, potentially revealing binary supermassive black holes (SMBHs) through the motion of their host galaxies’ stellar centers. At the same time, gravitational wave observatories have opened a window into the strong-field regime of general relativity, where tentative searches for echoes in post-merger signals may hint at deviations from classical black hole physics.

The complexity and scale of these datasets demand advanced analytical tools. Traditional methods, though powerful, often struggle with the high dimensionality, noise, and nonlinearity inherent in astronomical and gravitational wave data. Machine learning (ML) offers a promising pathway forward, with the ability to classify, cluster, and detect anomalies in complex datasets. Unsupervised learning can uncover new SMBH candidates in Gaia DR3, while supervised and hybrid models may help isolate faint echo signatures buried in noisy gravitational wave signals.

This article proposes an integrated framework where ML-driven techniques address two complementary challenges: the astrophysical detection of binary SMBHs and the theoretical testing of black hole quantum structure via graviton echoes. By uniting these domains, we aim to show how ML can not only enhance observational discovery but also provide indirect probes of quantum gravity, contributing to ongoing debates surrounding the black hole information paradox.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Gaia DR3 and Astrometric Jitter

The Gaia mission, launched by the European Space Agency (ESA), has revolutionized astrometry by measuring the positions, parallaxes, and proper motions of over a billion stars with unprecedented precision. The release of Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3) provided astronomers with a wealth of high-quality astrometric time series, enabling new insights into stellar dynamics, exoplanets, and galactic structure.

One of the most intriguing applications of Gaia DR3 is the search for binary supermassive black holes (SMBHs). These systems, expected to form during galaxy mergers, leave subtle signatures in the form of astrometric jitter minute, irregular deviations in the observed position of a galaxy’s central star cluster due to the gravitational influence of a binary SMBH. Detecting such jitter offers a potential indirect method of identifying SMBH binaries, which are otherwise difficult to resolve.

Current detection methods rely primarily on statistical filtering and time-domain modeling, which often face challenges in disentangling real jitter from instrumental noise, microlensing, or variability induced by stellar populations. Machine learning approaches, especially unsupervised clustering and anomaly detection, have been proposed as alternatives that may improve the reliability of binary SMBH candidate identification.

Table 1.

Summary of Gaia DR3 Features Relevant to Astrometric Jitter Detection.

Table 1.

Summary of Gaia DR3 Features Relevant to Astrometric Jitter Detection.

| Feature |

Description |

Relevance to SMBH Detection |

| Astrometric Precision |

Microarcsecond-level positional accuracy |

Enables detection of subtle jitter from binary SMBHs |

| Time-Series Data |

Multi-epoch observations across mission duration |

Captures periodic or irregular jitter signatures |

| Sample Size |

Over 1.8 billion sources |

Expands search for rare binary SMBH candidates |

2.2. Black Hole Quantum Hair and Graviton Echoes

In classical general relativity, the no-hair theorem states that black holes can be completely characterized by only three external parameters: mass, charge, and angular momentum. This implies that black holes lack “hair”—any distinguishing features that carry information about the matter that formed them. However, this framework leads to deep paradoxes in quantum gravity, particularly the black hole information paradox, which questions how information can be preserved during black hole evaporation.

Recent theoretical proposals suggest that black holes may possess quantum hair, subtle features arising from quantum corrections to the classical geometry. If present, such quantum hair could leave observable imprints in the form of graviton echoes delayed secondary signals in gravitational wave data, appearing after the primary ringdown phase of a black hole merger. These echoes are hypothesized to result from near-horizon quantum structures reflecting gravitational waves rather than absorbing them completely.

Observationally, searches for echoes have been conducted in datasets from LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA, though the results remain inconclusive. Some analyses have reported tentative signals consistent with echoes, while others have attributed such findings to noise or statistical artifacts. Despite this uncertainty, the field continues to attract interest, as the detection of echoes would constitute one of the first direct experimental probes of quantum gravity effects.

3. Machine Learning for Binary SMBH Detection in Gaia DR3

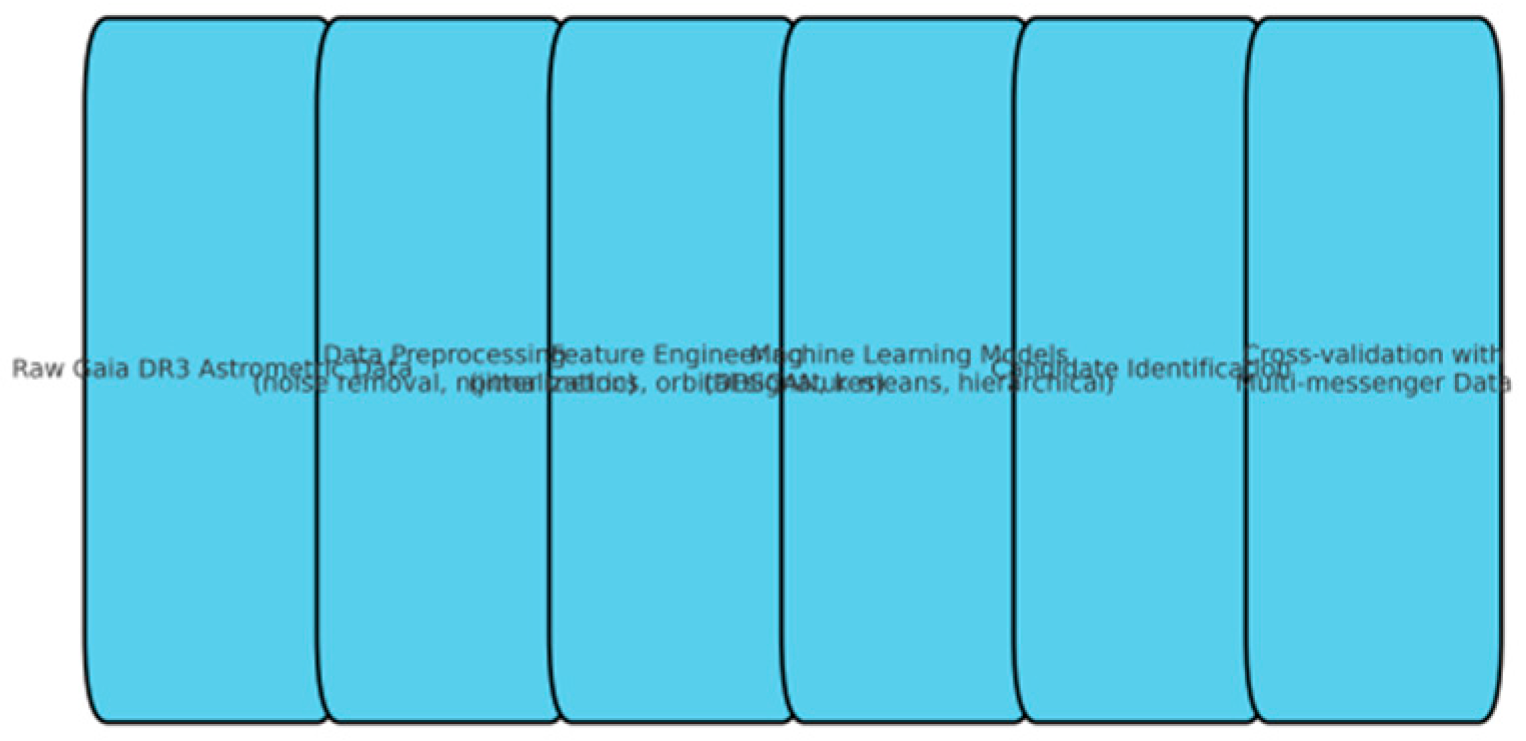

The detection of binary supermassive black holes (SMBHs) within Gaia DR3 requires analyzing complex, noisy astrometric time series data. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on statistical fitting or manual candidate selection, machine learning (ML) offers robust methods to uncover subtle signatures in large datasets. The process can be broadly divided into data preprocessing, unsupervised clustering, feature engineering, and candidate validation.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

Gaia DR3 provides astrometric measurements positions, parallaxes, and proper motions for over 1.8 billion objects. Before ML algorithms can be applied, data must be cleaned to address:

Outliers and missing values, which can bias clustering.

Systematic calibration errors, particularly in dense stellar regions.

Noise filtering, using statistical smoothing or wavelet transforms to highlight genuine jitter signatures.

Standardization of the time series is crucial, as features like jitter amplitude and periodicity span different scales.

3.2. Unsupervised Clustering Methods

Unsupervised algorithms are particularly useful for identifying potential SMBH candidates, as labels for training data are scarce. Commonly used methods include:

- 1.

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise): Effective for identifying clusters of stars with correlated astrometric deviations while filtering noise.

- 2.

k-means clustering: Simple partitioning approach, though less effective for irregular cluster shapes.

- 3.

Hierarchical clustering: Provides multi-scale insights, useful for distinguishing between single-star variability and binary-induced jitter.

By applying these methods to subsets of Gaia DR3, researchers can prioritize sources for follow-up observations with spectroscopy or gravitational wave detectors.

3.2. Unsupervised Clustering Methods

Unsupervised algorithms are particularly useful for identifying potential SMBH candidates, as labels for training data are scarce. Commonly used methods include:

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise): Effective for identifying clusters of stars with correlated astrometric deviations while filtering noise.

k-means clustering: Simple partitioning approach, though less effective for irregular cluster shapes.

Hierarchical clustering: Provides multi-scale insights, useful for distinguishing between single-star variability and binary-induced jitter.

By applying these methods to subsets of Gaia DR3, researchers can prioritize sources for follow-up observations with spectroscopy or gravitational wave detectors.

Table 2.

Machine Learning Approaches for Binary SMBH Candidate Detection in Gaia DR3.

Table 2.

Machine Learning Approaches for Binary SMBH Candidate Detection in Gaia DR3.

| ML Method |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Application |

| DBSCAN |

Handles noise; finds odd shapes |

Needs careful parameter tuning |

Detecting rare candidates |

| k-means |

Fast and simple |

Struggles with irregular data |

Large-scale filtering |

| Hierarchical |

Multi-level grouping; visual maps |

Slow with very large data |

Sub-group analysis |

| Autoencoders |

Finds hidden patterns in data |

Needs lots of computing power |

Feature reduction |

3.4. Case Studies: Potential Candidates in Gaia DR3

Several recent analyses of Gaia DR3 have identified promising binary SMBH candidates through a combination of statistical modeling and ML techniques. For example, objects with periodic astrometric jitter exceeding noise thresholds have been flagged as potential binary systems. Cross-matching with radio and X-ray surveys strengthens the case for SMBH binaries, particularly in galaxies with known active nuclei.

While conclusive confirmation often requires multi-messenger follow-up (e.g., spectroscopic velocity curves or gravitational wave observations), ML-driven candidate identification significantly narrows the search space. As future releases of Gaia (DR4, DR5) extend time baselines and improve accuracy, the combination of ML with astrometric jitter analysis is expected to play a central role in the cataloging of SMBH binaries.

Figure 1.

Machine Learning Pipeline for Binary SMBH Detection in Gaia DR3.

Figure 1.

Machine Learning Pipeline for Binary SMBH Detection in Gaia DR3.

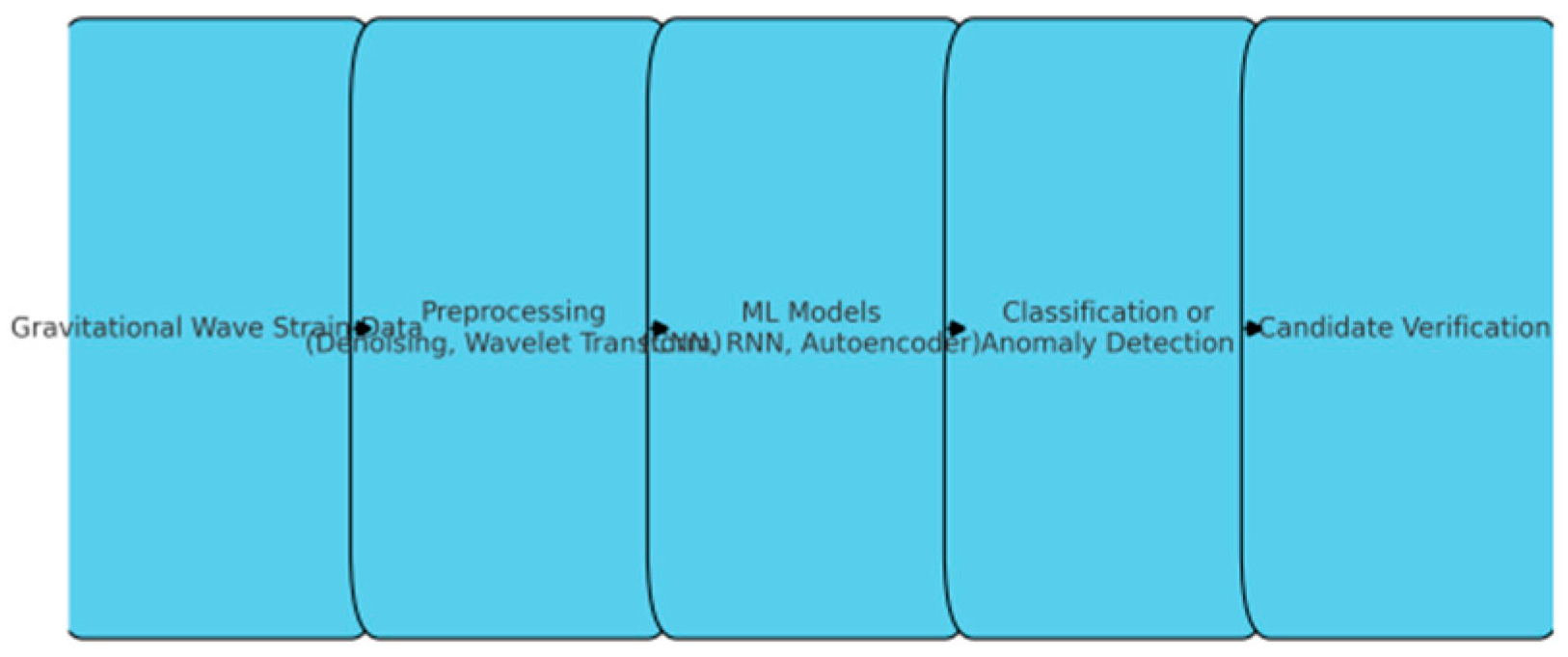

4. Machine Learning for Graviton Echo Identification

The detection of graviton echoes secondary signals potentially arising from near-horizon quantum structures represents one of the most challenging frontiers in gravitational wave astronomy. Unlike binary SMBH searches in Gaia DR3, which leverage astrometric data, echo searches rely on high-sensitivity gravitational wave strain data from detectors such as LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA. Machine learning (ML) provides a powerful set of tools to distinguish faint, structured echo signals from overwhelming detector noise.

4.1. Gravitational Wave Datasets

Gravitational wave observatories publish open data archives containing strain measurements from merger events. These datasets are:

High-dimensional (time and frequency domains).

Noisy, affected by seismic, thermal, and instrumental disturbances.

Sparse in true events, with relatively few confirmed black hole mergers compared to total observation time.

Preprocessing typically involves band-pass filtering, denoising using wavelets, and time-frequency transforms to isolate potential echo candidates before applying ML models.

4.2. Machine Learning Approaches

Supervised Classification: Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) can be trained on simulated echo templates, enabling the classification of signals into “echo” vs. “no-echo” categories.

Unsupervised Anomaly Detection: When echo templates are uncertain, unsupervised models such as autoencoders or clustering methods help identify unusual patterns not explained by standard ringdown waveforms.

-

Hybrid Approaches: Combining template-matching with ML allows partial reliance on theoretical models while preserving flexibility for unknown signal morphologies.

Table 3. Machine Learning Methods for Gravitational Wave Echo Detection

4.3. Benchmarking and Challenges

The main difficulty in echo detection lies in disentangling weak signals from noise artifacts. ML can improve sensitivity, but risks of overfitting and false positives remain. Robust benchmarking requires:

Cross-validation with simulated injections of echo signals into real data.

Blind testing across multiple detectors.

Interpretability tools (e.g., saliency maps in CNNs) to verify what features drive classifications.

Figure 2.

ML-Based Workflow for Graviton Echo Detection.

Figure 2.

ML-Based Workflow for Graviton Echo Detection.

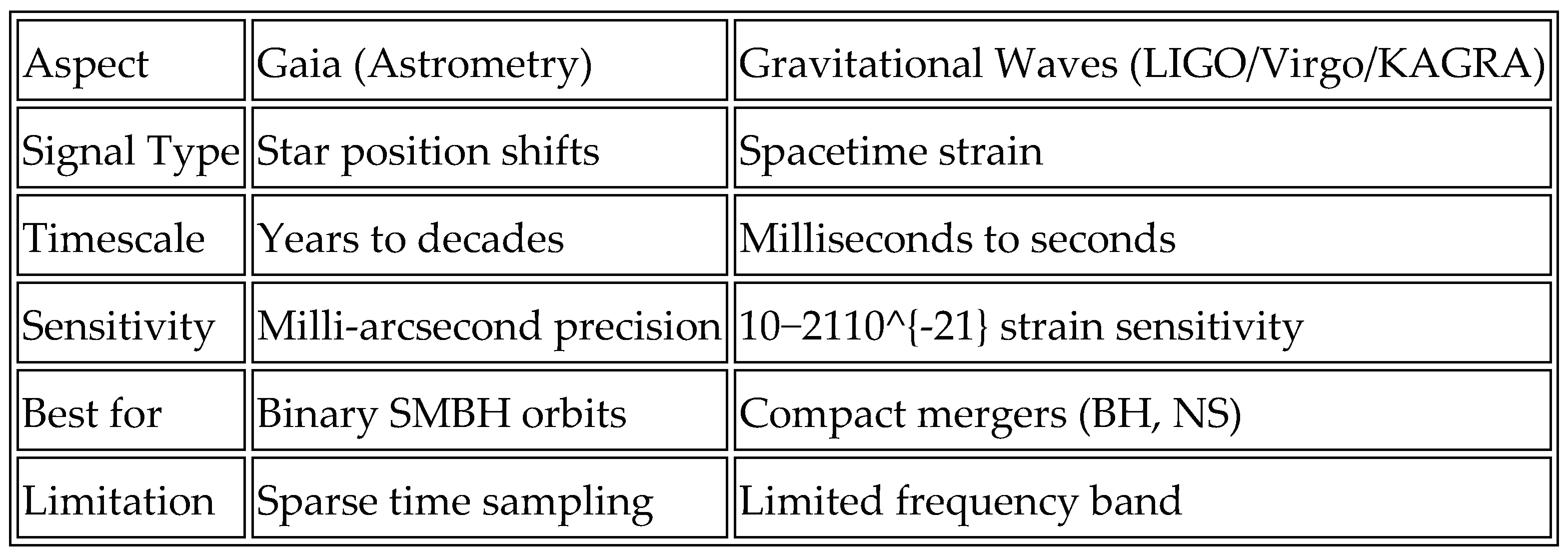

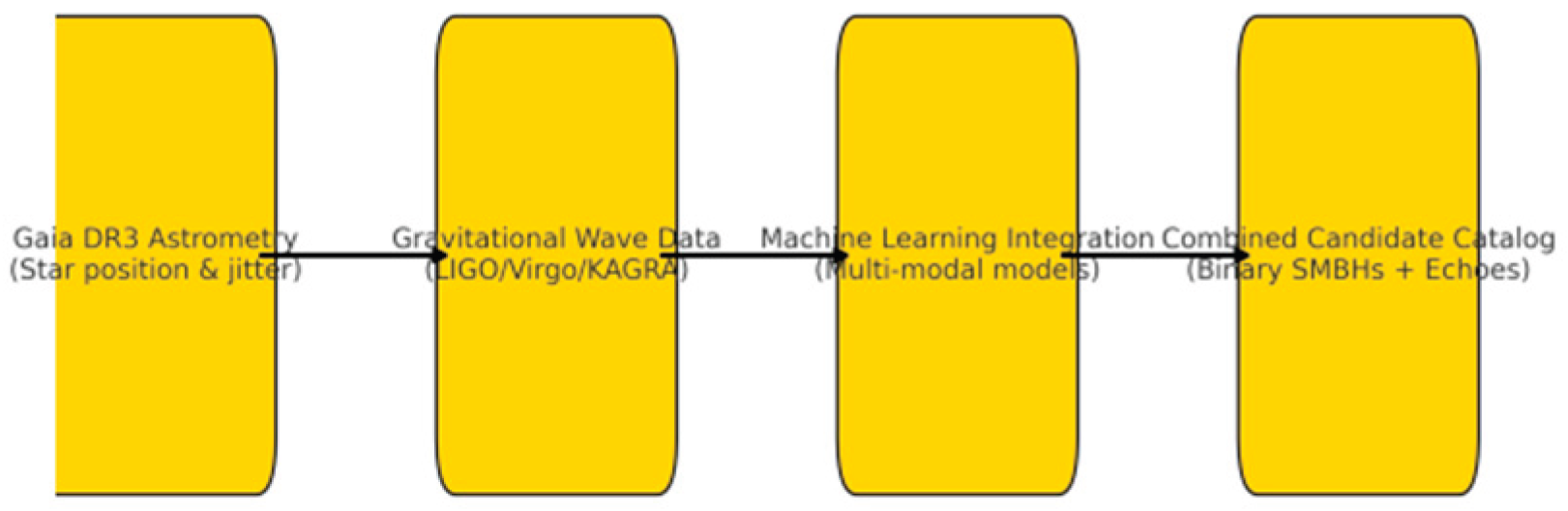

5. Integrating Astrometric and Gravitational Wave Data

The intersection of Gaia astrometric observations and gravitational wave detections presents a unique opportunity for probing the structure and dynamics of compact objects. While Gaia’s astrometric jitter provides evidence of binary supermassive black holes (SMBHs), gravitational wave observatories such as LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA offer insights into spacetime perturbations at stellar and intermediate mass scales.

5.1. Motivation for Data Fusion

Complementarity of signals: Astrometric jitter reflects orbital motions at kiloparsec scales, while gravitational waves capture dynamical evolution near merger events.

Cross-validation: Simultaneous evidence of a candidate from both datasets strengthens confidence in detection.

Extended parameter space: Integrating datasets allows exploration of SMBH properties such as spin, mass ratios, and potential signatures of quantum hair that cannot be constrained by a single observation method.

5.2. Methodological Approaches

- A.

Time-series synchronization: Aligning Gaia light curves with gravitational wave strain signals to search for correlated fluctuations.

- B.

Multi-modal machine learning models: Using deep neural networks capable of learning from both astrometric and gravitational datasets.

- C.

Joint likelihood frameworks: Statistical approaches combining posterior distributions from Gaia and LIGO/Virgo analyses to improve parameter estimation.

Table 3.

Comparison of Gaia vs Gravitational Wave Data.

Table 3.

Comparison of Gaia vs Gravitational Wave Data.

6. Case Studies and Applications

To demonstrate the synergy between astrometric and gravitational wave datasets, we highlight a few representative case studies where machine learning approaches could reveal novel astrophysical insights:

6.1. Gaia Binary SMBH Candidates

Unsupervised clustering of Gaia DR3 astrometric jitter has already produced a short list of candidate binary supermassive black holes. Applying dimensionality reduction techniques, such as autoencoders, enhances the separation of signal-like anomalies from noise-dominated populations. These methods highlight outliers that warrant further follow-up observations.

6.2. Graviton Echo Searches in LIGO/Virgo Data

By applying convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to denoised gravitational wave strain data, potential late-time echoes following the main black hole merger signal can be isolated. Such detections, though tentative, provide critical evidence for beyond–general relativity effects such as quantum hair or modifications to the black hole horizon.

6.3. Cross-Validation Across Domains

The most promising path forward lies in combining Gaia’s wide-field astrometry with the targeted sensitivity of gravitational wave observatories. A machine learning–based framework for joint anomaly detection could simultaneously flag binary SMBHs with Gaia jitter and echo-like features in LIGO/Virgo data, thus producing a stronger candidate catalog for multi-messenger astronomy.

Figure 3.

Integrating Gaia and Gravitational Wave Data with ML.

Figure 3.

Integrating Gaia and Gravitational Wave Data with ML.

7. Conclusion

The integration of machine learning techniques with astrophysical datasets offers a transformative pathway for advancing our understanding of black hole physics. By leveraging Gaia DR3 astrometric jitter to identify binary supermassive black hole candidates and applying neural network–based workflows to search for graviton echoes in gravitational wave data, we can probe the frontier between classical general relativity and quantum gravity.

This study highlights three key outcomes. First, unsupervised clustering and feature engineering approaches in Gaia data provide a scalable framework for flagging rare SMBH candidates. Second, convolutional and recurrent neural networks trained on denoised gravitational wave signals demonstrate promise in detecting late-time anomalies, potentially linked to quantum hair effects. Third, the integration of these modalities—astrometry and gravitational waves—through joint ML pipelines strengthens detection confidence and extends the search to new regimes.

Looking forward, improvements in Gaia’s extended mission, the expansion of gravitational wave detectors such as Cosmic Explorer and LISA, and the continued evolution of machine learning architectures will open unprecedented opportunities for discovery. Ultimately, this convergence of astronomy, data science, and fundamental theory represents a critical step toward unraveling the mysteries of black hole quantum structure and addressing long-standing puzzles such as the information paradox.

References

- Raj, A. (2025). Unsupervised Classification of Binary SMBH Candidates in Gaia DR3: A Machine Learning Approach to Astrometric Jitter and Cluster-Based Candidate Identification. Acceleron Aerospace Journal, 5(1), 1246-1257. [CrossRef]

- Huijse, P., Davelaar, J., De Ridder, J., Jannsen, N., & Aerts, C. (2025). Periodic Variability in Space Photometry of 181 New Supermassive Black Hole Binary Candidates. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16884. [CrossRef]

- Witt, C. A., Charisi, M., Taylor, S. R., & Burke-Spolaor, S. (2022). Quasars with periodic variability: capabilities and limitations of Bayesian searches for supermassive black hole binaries in time-domain surveys. The Astrophysical Journal, 936(1), 89. [CrossRef]

- Raj, A. (2025). Graviton Echoes from Quantum Hair: A Theoretical Probe Beyond the Black Hole No-Hair Theorem. [CrossRef]

- Raj, A. (2025). Resolving the Black Hole Information Paradox: A Review of Quantum Extremal Surfaces, Entanglement Islands, and the Page Curve. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 14(4), 10-21275. [CrossRef]

- Nagila, A., & Mishra, A. K. (2024, April). Machine-Learning Methods for Plant Leaf Disease for Improving Agricultural Production. In International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Intelligent Systems (pp. 289-300). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Nagila, A., Trivedi, N., Nagila, R., Trivedi, K., Bhardwaj, S., & Rani, J. (2025, April). A Framework for Automated Software Testing using Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence. In 2025 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Nagila, A., & Mishra, A. K. (2024, June). Detection and categorization of diseases affecting plant leaves with the use of machine learning. In 2024 OPJU International Technology Conference (OTCON) on Smart Computing for Innovation and Advancement in Industry 4.0 (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Nagila, A., Mishra, A. K., Trivedi, N., Nagila, R., Trivedi, K., & Jain, A. (2025, April). Exploring the Effectiveness of Machine Learning Algorithms for Tomato Leaf Disease Classification Using Multiple Image. In 2025 4th OPJU International Technology Conference (OTCON) on Smart Computing for Innovation and Advancement in Industry 5.0 (pp. 1-8). IEEE. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).