Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

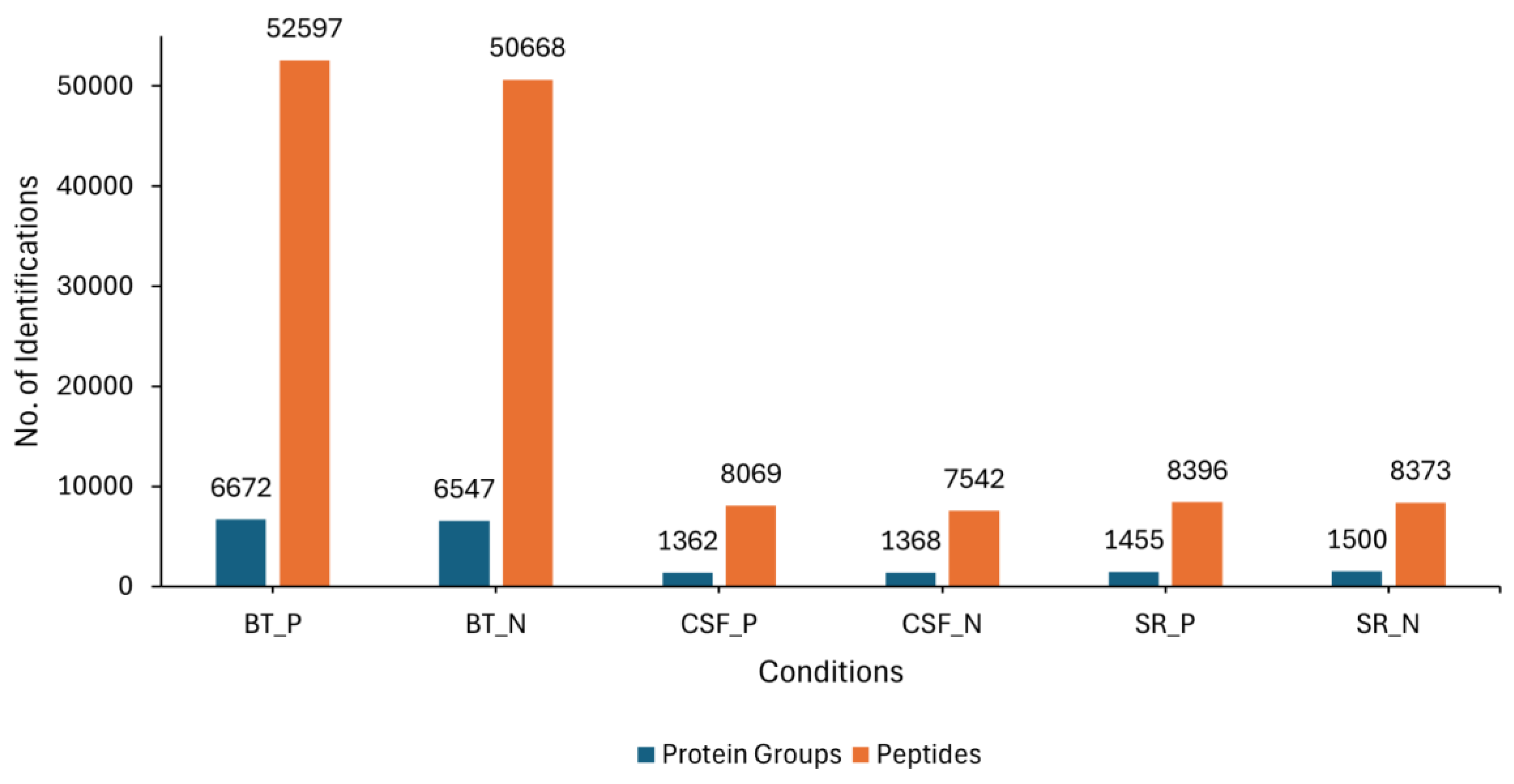

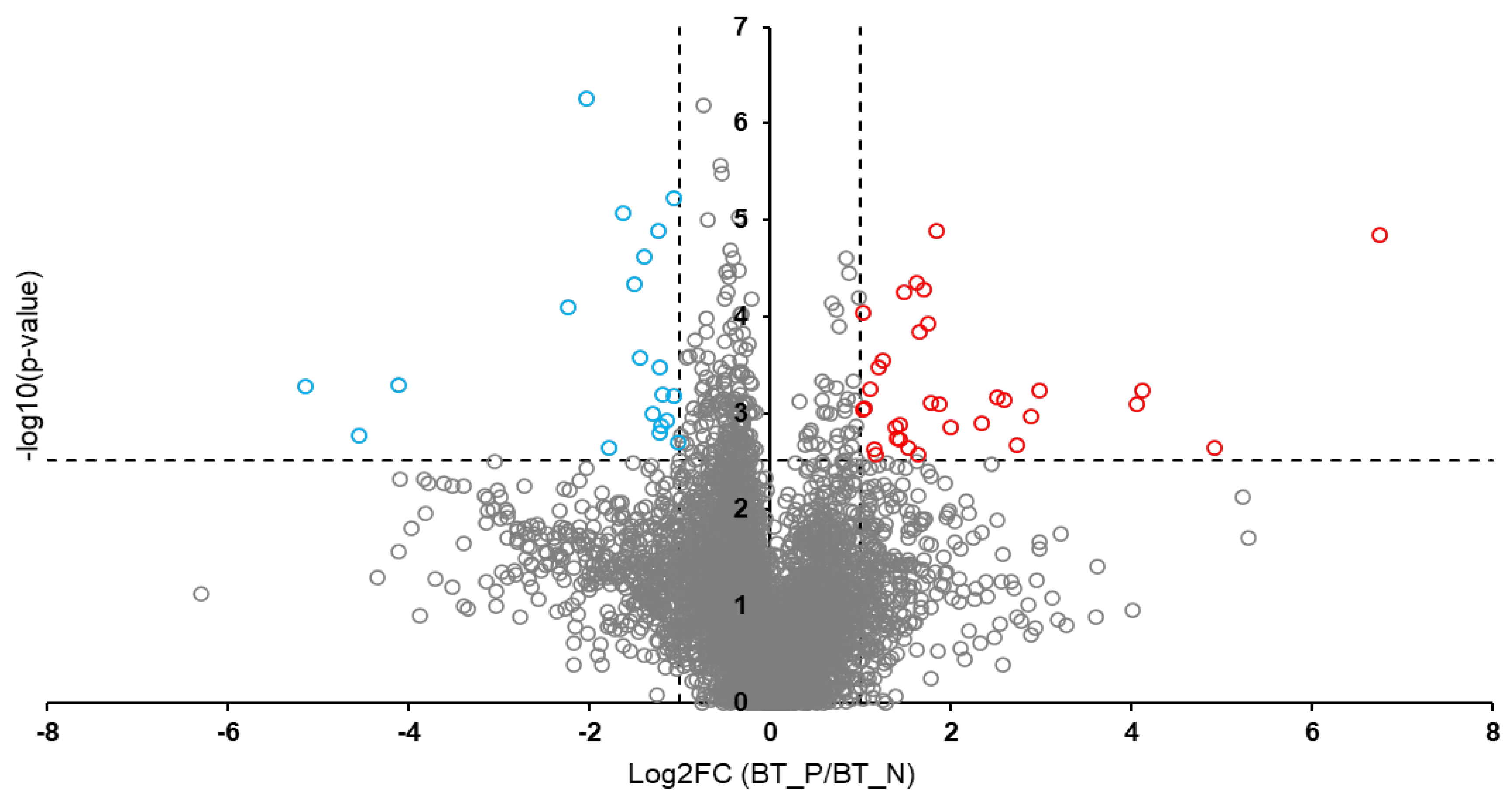

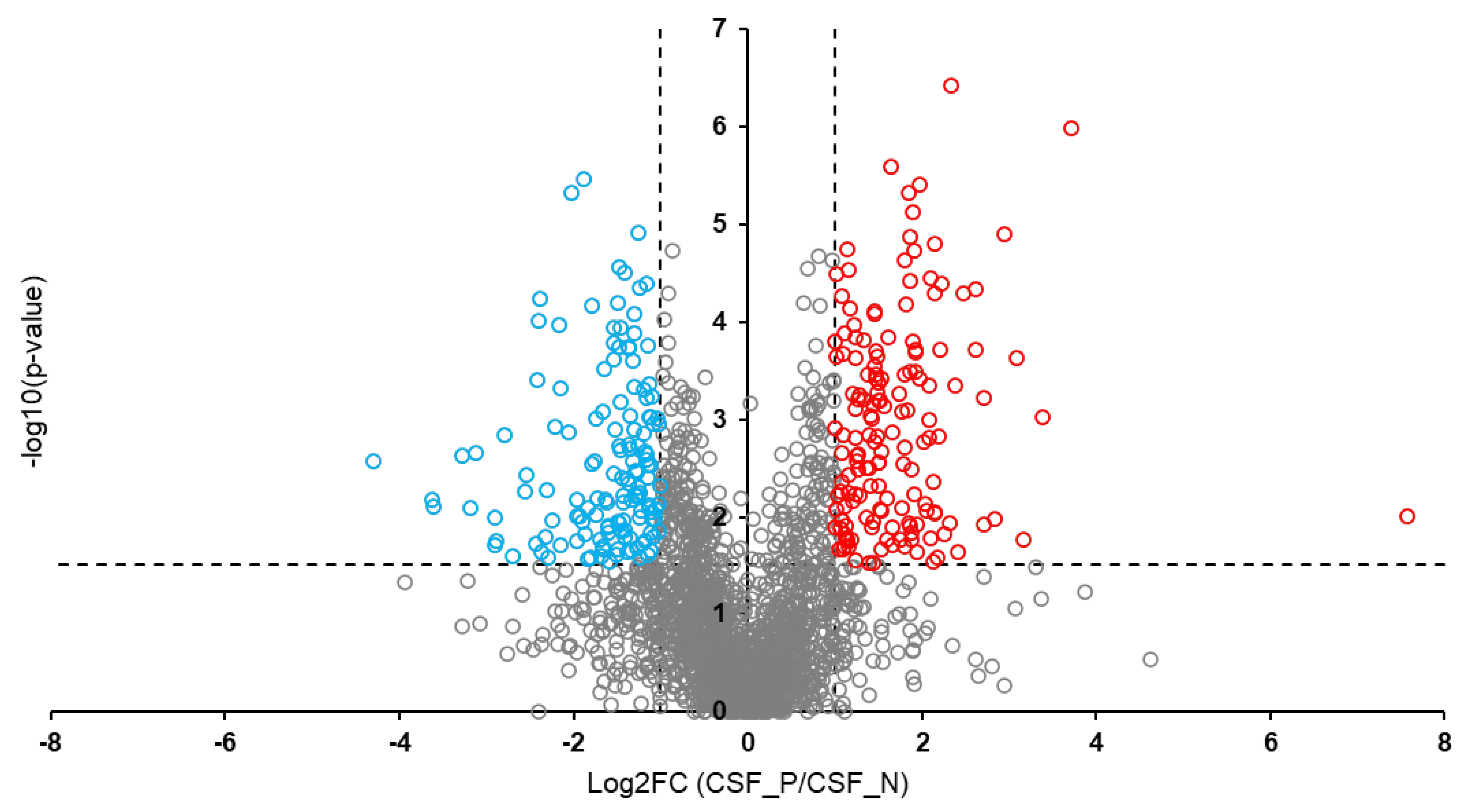

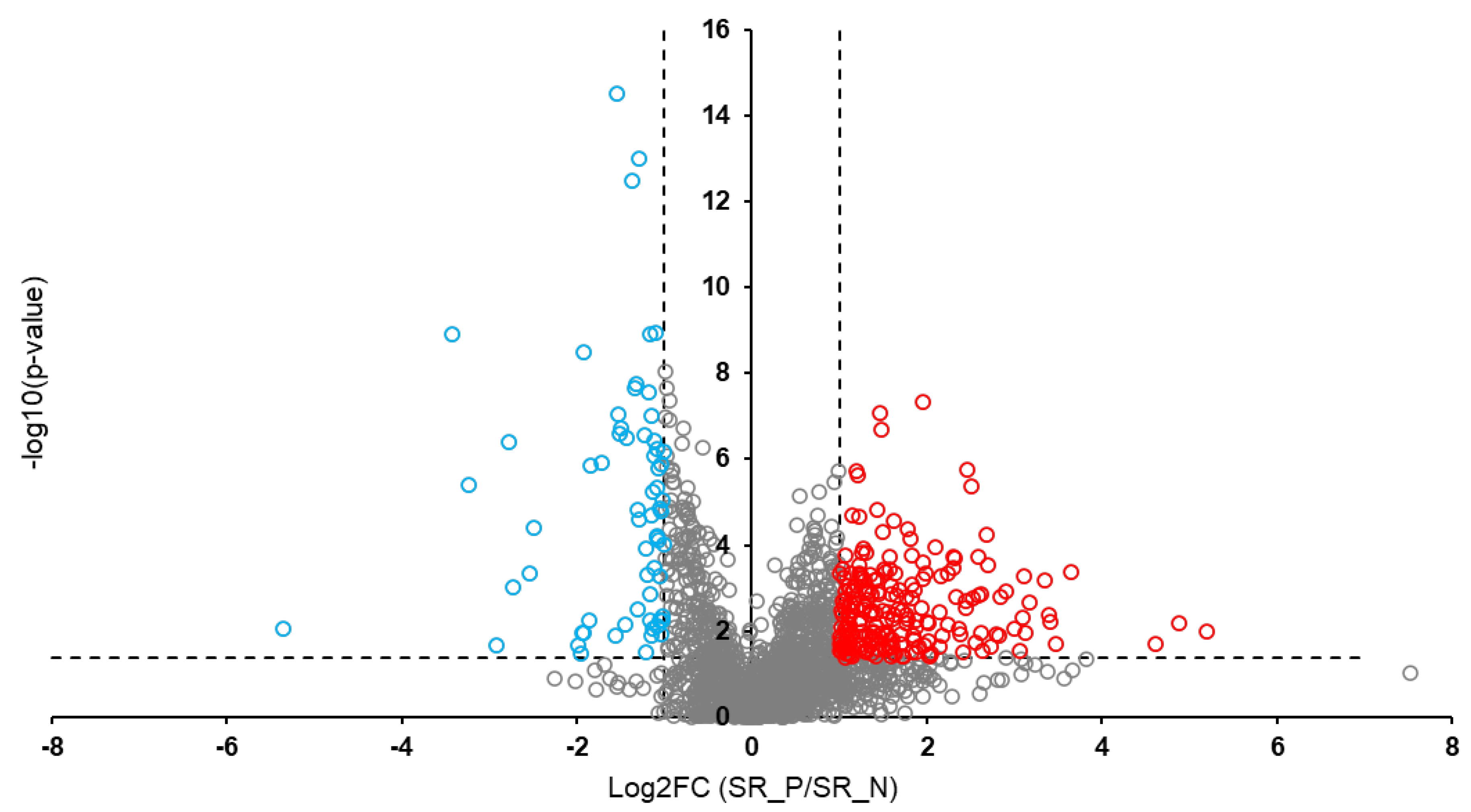

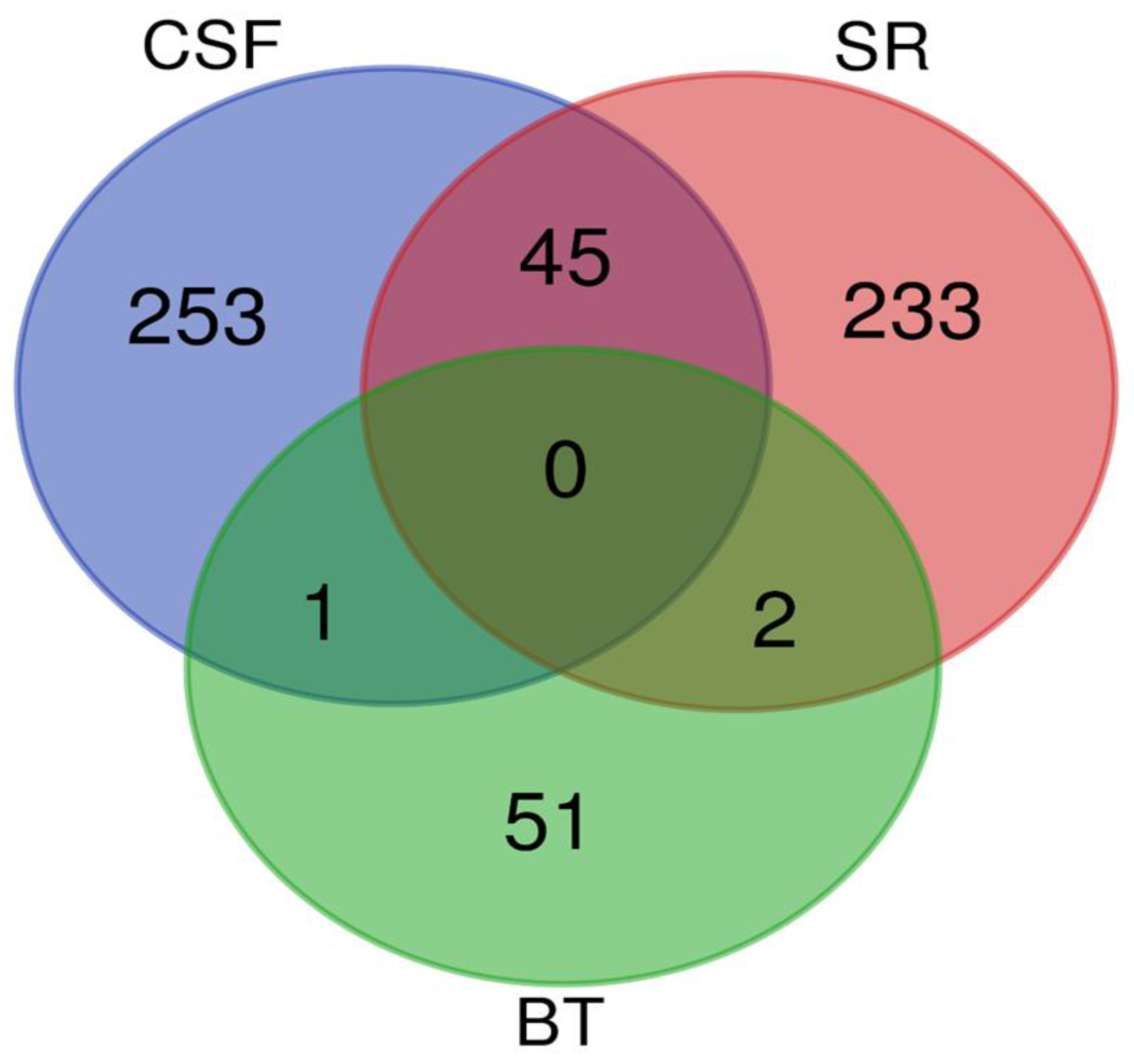

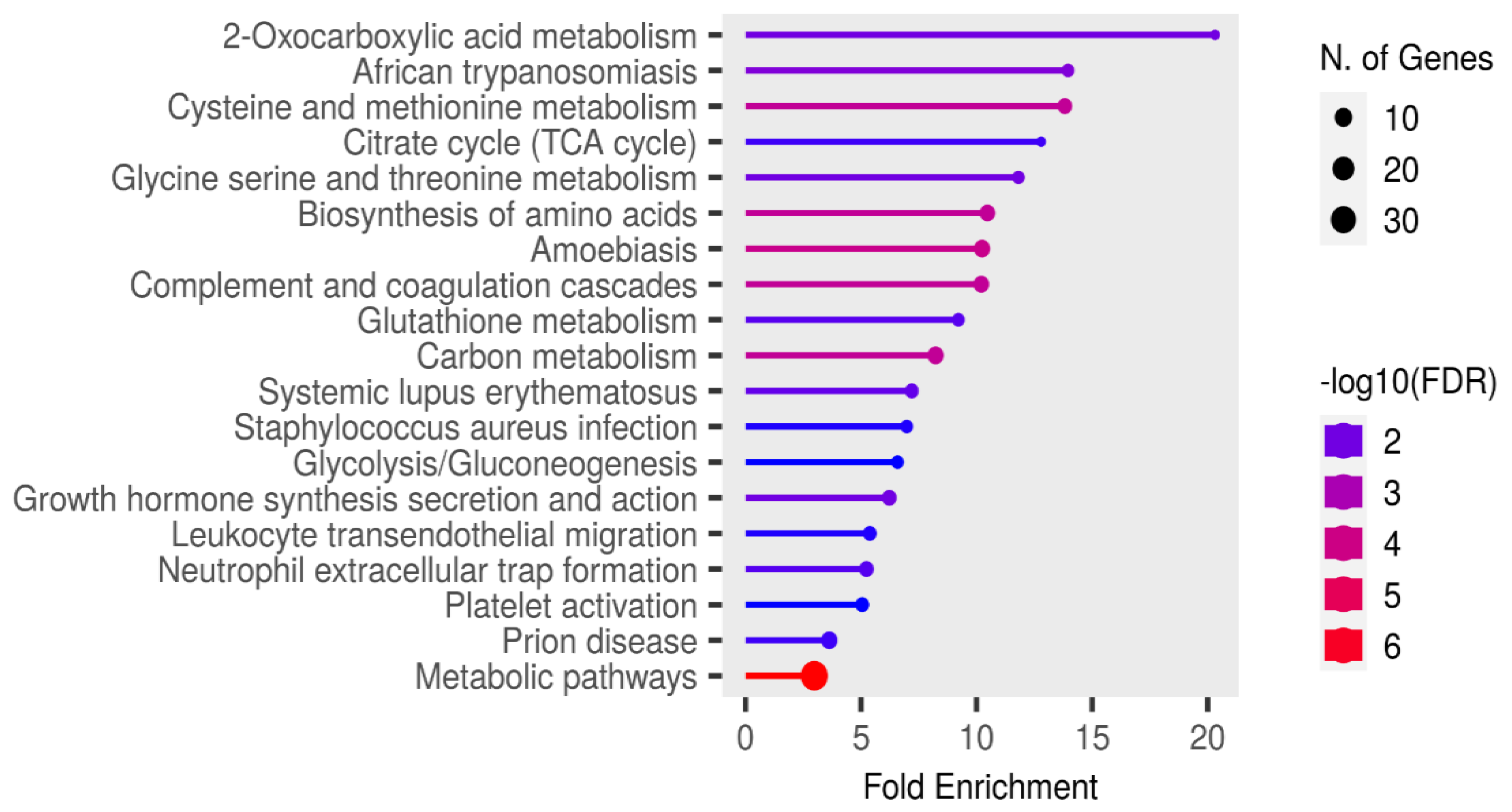

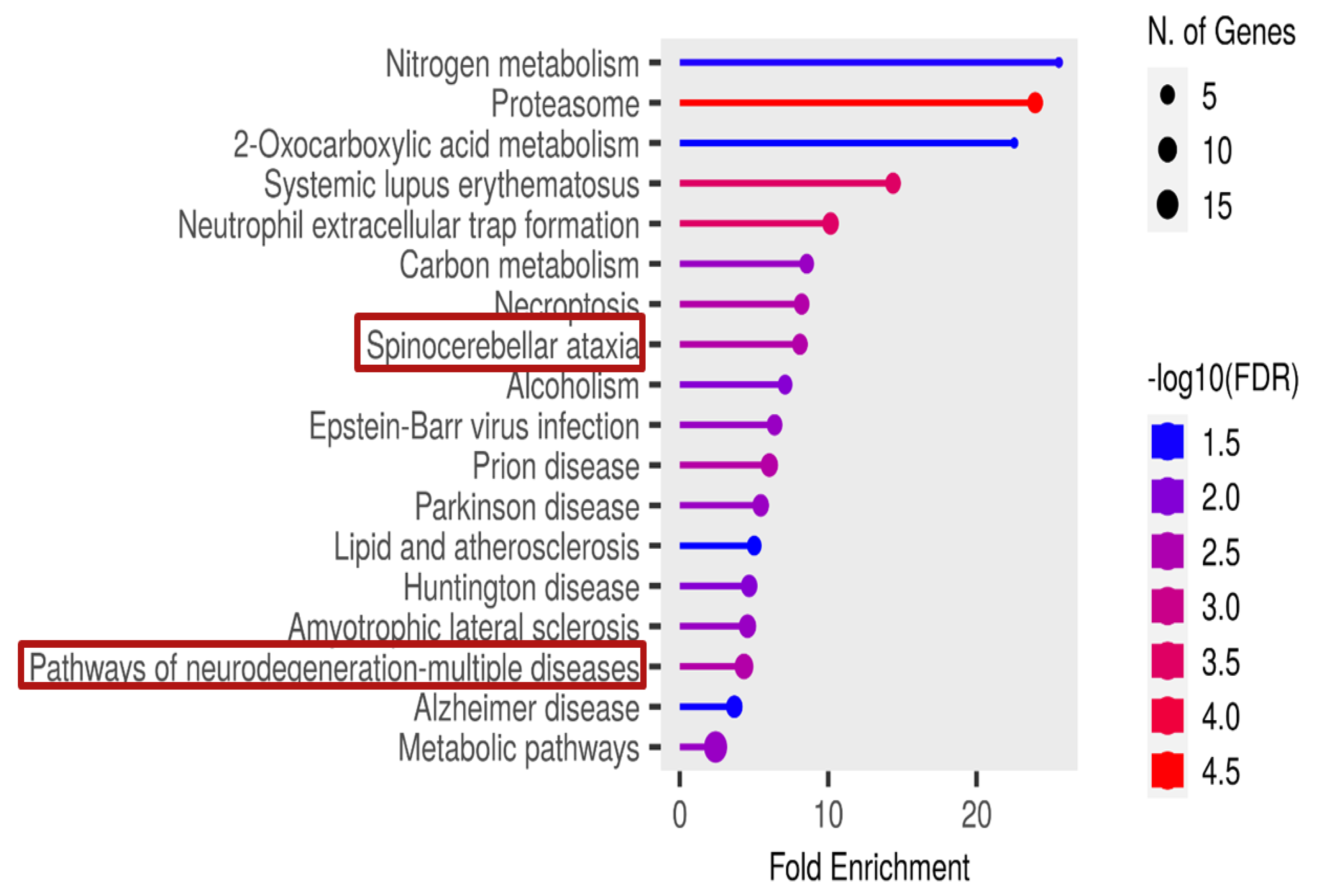

Background: Rabies is among the oldest known zoonotic viral diseases and is caused by members of the Lyssavirus genus. The prototype species, Lyssavirus rabies, effectively evades the host immune response, allowing the infection to progress unnoticed until the onset of clinical signs. At this stage, the disease is irreversible and invariably fatal, with definitive diagnosis possible only post-mortem. Given the advances in modern proteomics, this study aimed to identify potential protein biomarkers for antemortem diagnosis of rabies in dogs, which are the principal reservoir hosts of the rabies virus. Methods: Two hundred and thirty-one samples (brain tissues (BT), cerebrospinal fluids (CSF), and serum (SR) samples) were collected from apparently healthy dogs brought for slaughter for human consumption in South-East and North-Central Nigeria. All the BT were subjected to a direct fluorescent antibody test to confirm the presence of lyssavirus antigen, and 8.7% (n = 20) were positive. Protein extraction, quantification, reduction, and alkylation were followed by on-bead (HILIC) cleanup and tryptic digestion. The resulting peptides from each sample were injected into the Evosep One LC system, coupled to the timsTOF HT MS, using the standard dia-PASEF short gradient data acquisition method. Data was processed using SpectronautTM (v19). An unpaired t-test was performed to compare identified protein groups (proteins and their isoforms) between the rabies-infected and uninfected BT, CSF, and SR samples. Results: The study yielded 54 significantly differentially abundant proteins for the BT group, 299 for the CSF group, and 280 for the SrRgroup. Forty-five overlapping differentially abundant proteins were identified between CSF and SR, one between BT and CSF, and two between BT and SR; none were found that overlapped all three groups. Within the BT group, 33 proteins showed increased abundance, while 21 showed decreased abundance in the rabies-positive samples. In the CSF group, 159 proteins had increased abundance and 140 had decreased abundance in the rabies-positive samples. For the SR group, 215 proteins showed increased abundance, and 65 showed decreased abundance in the rabies-positive samples. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that pathways associated with CSF, spinocerebellar ataxia, and neurodegeneration were among the significant findings. Conclusion: This study identified canonical proteins in CSF and SR that serve as candidate biomarkers for rabies infection, offering insights into neuronal dysfunction and potential tools for early diagnosis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Area and Sample Size

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Protein Extraction

2.6. Protein Quantification, Digestion, and LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Retrospective Power Analysis

2.9. Functional Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proteome Profiling Overview

3.2. Overlapping Proteins Between the Different Sample Types

- Myelin basic protein (MBP)

- Ig-like domain-containing protein

3.3. Significant Pathways Identified from Functional Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Authors contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fooks, A. R.; Banyard, A. C.; Horton, D. L.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L. M.; Jackson, A. C. Current Status of Rabies and Prospects for Elimination. Lancet 2014, 384(9951), 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, Y. A.; El-Duah, P.; Sylverken, A. A.; Owusu, M.; Yeboah, R.; Gorman, R.; Adade, T.; Bonney, J.; Tasiame, W.; Nyarko-Jectey, K.; Binger, T.; Corman, V. M.; Drosten, C.; Phillips, R. O. Rabies Is Still a Fatal but Neglected Disease: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15(1), 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, B.; Shrivastava, N.; Sheikh, N. P.; Singh, P. K.; Jha, H. C.; Parmar, H. S. Rabies vaccines: Journey from classical to modern era. Vet. Vaccine 2025, 4(1), 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, G. B.; Abagero, A.; Addissie, A.; Tadesse, M.; Gelan, A.; Benti, D.; Abdella, A.; Birhanu, Y.; Tesema, A.; Tessema, T.; Kure, A.; Mekonen, A.; Shumuye, N.; Gebremariam, B.; Wubishet, T. Epidemiology of Suspected Rabies Cases in Ethiopia: 2018–2022. One Health Adv. 2024, 2(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses: Online Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. https://ictv.global/report (accessed 2025).

- Coleman, P. G.; Dye, C. Immunization Coverage Required to Prevent Outbreaks of Dog Rabies. Vaccine 1996, 14(3), 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2018, 93(16), 201–220, http://www.who.int/wer. [Google Scholar]

- Mshelbwala, P. P.; Rupprecht, C. E.; Osinubi, M. O.; Njoga, E. O.; Orum, T. G.; Weese, J. S.; Clark, N. J. Factors Influencing Canine Rabies Vaccination among Dog-Owning Households in Nigeria. One Health 2024, 18, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacko, K.; Theeyancheri Parakadavathu, R.; Al-Maslamani, M. Diagnostic Difficulties in Human Rabies: A Case Report and Literature Review. Qatar Med. J. 2016, 2016(15), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C. E.; Hanlon, C. A.; Hemachudha, T. Rabies Re-Examined. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002, 2(6), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemachudha, T.; Laothamatas, J.; Rupprecht, C. E. Human Rabies: A Disease of Complex Neuropathogenetic Mechanisms and Diagnostic Challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12(5), 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A. C. Subversion of the Immune Response by Rabies Virus. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønborg, M.; Kristiansen, T. Z.; Iwahori, A.; Chang, R.; Reddy, R.; Sato, N.; Molina, H.; Jensen, O. N.; Hruban, R. H.; Goggins, M. G.; Maitra, A.; Pandey, A. Biomarker Discovery from Pancreatic Cancer Secretome Using a Differential Proteomic Approach. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2006, 5(1), 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, L. H. Breast Cancer and Protein Biomarkers. World J. Exp. Med. 2012, 2(5), 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, M.; Matsuyama, Y.; Nirasawa, T.; Thiele, H.; Becker, M.; Alexandrov, T.; Saida, T.; Tanaka, M.; Matsuo, H.; Tomimoto, H.; Takahashi, R.; Tashiro, K.; Ikegawa, M.; Kondo, T. Proteomic Pattern Analysis Discriminates among Multiple Sclerosis-Related Disorders. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71(5), 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, N.; Nakagawa, S.; Sun, X.; Hoshida, Y. Cancer Biomarker Discovery and Validation. Transl. Cancer Res. 2015, 4(3), 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, G.; Richardus, J. H.; Jiang, X.; Cao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, B. Quantitative proteomics for identifying biomarkers for rabies. J. Virol. 2008, 82(21), 10412–10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, T. Y.; van Heesch, S.; van den Toorn, H.; Giansanti, P.; Cristobal, A.; Toonen, P.; Schafer, S.; Hübner, N.; van Breukelen, B.; Mohammed, S.; Cuppen, E.; Heck, A. J.; Guryev, V. Quantitative and Qualitative Proteome Characteristics Extracted from In-Depth Integrated Genomics and Proteomics Analysis. Cell Rep. 2013, 5(5), 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, A. K.; Ghantasala, S. S.; Selvan, L. D.; Mahadevan, A.; Renuse, S.; Kumar, P.; Pawar, H.; Sahasrabhuddhe, N. A.; Suja, M. S.; Ramachandra, Y. L.; Prasad, T. S.; Madhusudhana, S. N.; Hc, H.; Chaerkady, R.; Satishchandra, P.; Pandey, A.; Shankar, S. K. Quantitative Proteomics for Identifying Biomarkers for Rabies. Clin. Proteomics 2013, 10(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahtaj, F.; Zandi, F.; Khalaj, V.; Biglari, P.; Fayaz, A.; Vaziri, B. Proteomics Analysis of Human Brain Tissue Infected by Street Rabies Virus. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40(11), 6443–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shandra, P.; Goda, R.; Dhingra, V.; Kirmani, A. R.; Sandhir, R.; Banerjee, A. Delineation of Altered Brain Proteins Associated with Furious Rabies Virus Infection in Dogs by Quantitative Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14(5), 2201–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A. K.; Fultang, N.; Pati, U.; Banerjee, A. Pathway Analysis of Proteomics Profiles in Rabies Infection. OMICS 2015, 19(11), 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Kuribayashi, K.; Inomata, N.; Noguchi, K.; Kimitsuki, K.; Demetria, C. S.; Saito, N.; Inoue, S.; Park, C. H.; Kaimori, R.; Suzuki, M.; Saito-Obata, M.; Kamiya, Y.; Manalo, D. L.; Quiambao, B. P.; Nishizono, A. Validation of serum apolipoprotein A1 in rabies virus-infected mice as a biomarker for the preclinical diagnosis of rabies. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 65(10), 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Tang, R.; Zhang, H.; Kiflu, A. B.; Liu, C.; Liang, J.; Li, X.; Luo, T. R. Apolipoprotein D facilitates rabies virus propagation by interacting with G protein and upregulating cholesterol. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1392804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, USA. 1996.

- Thrusfield, M. Veterinary Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, U.K, 2005; pp. 233–234. [Google Scholar]

- Eze, U. U.; Ngoepe, E. C.; Anene, B. M.; Ezeokonkwo, R. C.; Nwosuh, C.; Sabeta, C. T. Detection of Lyssavirus Antigen and Antibody Levels among Apparently Healthy and Suspected Rabid Dogs in South-Eastern Nigeria. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11(1), 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, D. J.; Abelseth, M. K.; Atanasiu, P. The Fluorescent Antibody Test. In Laboratory Techniques in Rabies, 4th ed.; Meslin, F.-X., Kaplan, M. M., Koprowski, H., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 1996; pp. 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nejadi, N.; Mohammadpoor Masti, S.; Rezaei Tavirani, M.; Golmohammadi, T. Comparison of Three Routine Protein Precipitation Methods: Acetone, TCA/Acetone Wash and TCA/Acetone. Arch. Adv. Biosci. 2014, 5(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baichan, P.; Naicker, P.; Augustine, T. N.; Smith, M.; Candy, G.; Devar, J.; Nweke, E. E. Proteomic Analysis Identifies Dysregulated Proteins and Associated Molecular Pathways in a Cohort of Gallbladder Cancer Patients of African Ancestry. Clin. Proteom. 2023, 20(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProtKB – A0A8C0P9A0 [Protein Entry]. UniProt. https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/A0A8C0P9A0/entry (accessed Jun 12, 2025).

- Choi, M.; Chang, C. Y.; Clough, T.; Broudy, D.; Killeen, T.; MacLean, B.; Vitek, O. MSstats: An R Package for Statistical Analysis of Quantitative Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Experiments. Bioinformatics 2014, 30(17), 2524–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Thompson, S. J.; Loftus, L. T.; Ashley, M. D.; Meller, R. Ubiquitin-Proteasome System as a Modulator of Cell Fate. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8(1), 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Bai, J.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, R.; Kang, K.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, M. Integrative genomic analysis of PPP3R1 in Alzheimer’s disease: a potential biomarker for predictive, preventive, and personalized medical approach. EPMA J. 2021, 12(4), 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. NCBI Reference Sequence: Apolipoprotein C4 (APOC4). Gene ID 346. Alliance of Genome Resources. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/346 (acessed August 23, 2025).

- Gazzeri, S.; Brambilla, E.; Negoescu, A.; Thoraval, D.; Veron, M.; Moro, D.; Brambilla, C. Overexpression of Nucleoside Diphosphate/Kinase A/Nm23-H1 Protein in Human Lung Tumors: Association with Tumor Progression in Squamous Carcinoma. Lab. Invest. 1996, 74(1), 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T., Song, Y., Du, T., Ray, A., Wan, X., Wang, M., Pillai, S. C., Musa, M. A., Hao, M., Qiu, L., Chauhan, D., & Anderson, K. C. (2024). 26S proteasome non-ATPase subunit 3 (PSMD3/Rpn3) is a potential therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Blood, 144(Supplement 1), 1905. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, S. Translation Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Focus on ALS. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H.; Bässler, S.; Balta, D.; Socher, E.; Zunke, F.; Arnold, P. The Role of Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 433, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Kang, S.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, G.; Hong, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; He, S.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Li, K.; Li, X.; Liao, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, S. Crystal Structures of Bat and Human Coronavirus ORF8 Protein Ig-Like Domain Provide Insights into the Diversity of Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 807134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhart, R.; Wong, S. A.; Cao, J.; Tran, M.; Huynh, A.; Ardrey, C.; Park, J. M.; Hsu, C.; Taha, S.; Peterson, R.; Shea, S.; Kurian, J.; Venderova, K. Vacuolar Protein Sorting 35 (Vps35) Rescues Locomotor Deficits and Shortened Lifespan in Drosophila Expressing a Parkinson’s Disease Mutant of Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2). Mol. Neurodegener. 2014, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosic, M.; Ott, J.; Barral, S.; Bovet, P.; Deppen, P.; Gheorghita, F.; Matthey, M. L.; Parnas, J.; Preisig, M.; Saraga, M.; Solida, A.; Timm, S.; Wang, A. G.; Werge, T.; Cuénod, M.; Do, K. Q. Schizophrenia and Oxidative Stress: Glutamate Cysteine Ligase Modifier as a Susceptibility Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79(3), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. C.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Y.; Kim, J. H.; Han, Y.; Lee, S. H.; Kim, S. H.; Cho, B. C. PSMD1 as a Prognostic Marker and Potential Target in Oropharyngeal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Miao, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, S. Deubiquitinase PSMD7 regulates cell fate and is associated with disease progression in breast cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12(9), 5433–5448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Küry, S.; Besnard, T.; Ebstein, F.; Khan, T. N.; Gambin, T.; Douglas, J.; Bacino, C. A.; Craigen, W. J.; Sanders, S. J.; Lehmann, A.; Latypova, X.; Khan, K.; Pacault, M.; Sacharow, S.; Glaser, K.; Bieth, E.; Perrin-Sabourin, L.; Jacquemont, M.-L.; Cho, M. T.; Roeder, E.; Denommé-Pichon, A.-S.; Monaghan, K. G.; Yuan, B.; Xia, F.; Simon, S.; Bonneau, D.; Parent, P.; Gilbert-Dussardier, B.; Odent, S.; Toutain, A.; Pasquier, L.; Barbouth, D.; Shaw, C. A.; Patel, A.; Smith, J. L.; Bi, W.; Schmitt, S.; Deb, W.; Nizon, M.; Mercier, S.; Vincent, M.; Rooryck, C.; Malan, V.; Briceño, I.; Gómez, A.; Nugent, K. M.; Gibson, J. B.; Cogné, B.; Lupski, J. R.; Stessman, H. A. F.; Eichler, E. E.; Retterer, K.; Yang, Y.; Redon, R.; Katsanis, N.; Rosenfeld, J. A.; Kloetzel, P.-M.; Golzio, C.; Bézieau, S.; Stankiewicz, P.; Isidor, B. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100 (2), 352–363. [CrossRef]

- Minelli, A.; Magri, C.; Barbon, A.; Bonvicini, C.; Segala, M.; Congiu, C.; Bignotti, S.; Milanesi, E.; Trabucchi, L.; Cattane, N.; Bortolomasi, M.; Gennarelli, M. Proteasome System Dysregulation and Treatment Resistance Mechanisms in Major Depressive Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5(12), e687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeneCards: The Human Gene Database. SLC25A6 Gene - Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 6. Protein Coding. https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=SLC25A6 (accessed Jul 30, 2025).

- Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, M.; Duan, M.; Guan, Z.; Guo, Y. RABV Induces Biphasic Actin Cytoskeletal Rearrangement through Rac1 Activity Modulation. J. Virol. 2024, 98(7), e00606-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Qiu, H.; Xu, J.; Mo, J.; Liu, Y.; Gui, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, S.; Yao, H.; Huang, X.; Gan, Z. Expression and prognostic potential of GPX1 in human cancers based on data mining. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8(4), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Giese, K. P. Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Brain 2015, 8(1), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rat Genome Database. Gene: Ppp3r1 (Protein Phosphatase 3, Regulatory Subunit B, Alpha Isoform (Calcineurin B, Type I)) Mus musculus. Rat Genome Database. https://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/report/gene/main.html?id=735592 (accessed Aug 3, 2025).

- Watanabe, T.; Urano, E.; Miyauchi, K.; Ichikawa, R.; Hamatake, M.; Misawa, N.; Sato, K.; Ebina, H.; Koyanagi, Y.; Komano, J. The Hematopoietic Cell-Specific Rho GTPase Inhibitor ARHGDIB/D4GDI Limits HIV Type 1 Replication. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2012, 28(8), 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, R.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.; He, M.; Jiang, X.; Ren, C.; Zhou, Q. ARHGDIB as a prognostic biomarker and modulator of the immunosuppressive microenvironment in glioma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74(7), 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Zheng, S.; Liu, X.; Jin, J.; Ren, Y.; Luo, J. Myelin basic protein induces neuron-specific toxicity by directly damaging the neuronal plasma membrane. PLoS One 2014, 9(9), e108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, R. S.; Kunishita, T.; Koike, F.; Tabira, T. Semple Rabies Vaccine: Presence of Myelin Basic Protein and Proteolipid Protein and Its Activity in Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis. J. Neurol. Sci. 1989, 93((2–3)), 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProtKB – A0A8C0MGU9 [Protein Entry]. UniProt. https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/A0A8C0MGU9/entry (accessed Jul 5, 2025).

- Smith, D. K.; Xue, H. Sequence Profiles of Immunoglobulin and Immunoglobulin-like Domains. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 274(4), 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichmann, S. A.; Chothia, C. J. Immunoglobulin Superfamily Proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 296(5), 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, M. D.; Collins, B. M. The PDLIM Family of Actin-Associated Proteins and Their Emerging Role in Membrane Trafficking. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51(6), 2005–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potratz, M.; Zaeck, L. M.; Weigel, C.; Klein, A.; Freuling, C. M.; Müller, T.; Finke, S. Neuroglia Infection by Rabies Virus after Anterograde Virus Spread in Peripheral Neurons. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. C.; Kanter, J. E.; Kothari, V.; Bornfeldt, K. E. Quartet of APOCs and the Different Roles They Play in Diabetes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43(7), 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). Rabies. https://www.woah.org/en/disease/rabies/ (accessed June 2025).

- Randow, F.; Lehner, P. J. Viral Avoidance and Exploitation of the Ubiquitin System. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11(5), 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, K.; Früh, K.; DeFilippis, V. Viral Hijacking of the Host Ubiquitin System to Evade Interferon Responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13(4), 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R. Y.; Yeung, P. S. W.; Mann, M. W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y. K.; Hoofnagle, A. N. Post-Translationally Modified Proteoforms as Biomarkers: From Discovery to Clinical Use. Clin. Chem. 2025, hvaf094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SN | Protein | Gene | Function | Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, ATPase 6 | PSMC6 | a subunit of the 26S proteasome, a crucial protein degradation complex. Ubiquitinated proteins are recognized, unfolded, and degraded by the proteasome. |

As part of the proteasome, it can degrade proteins involved in activating the IFN pathway [34]. |

| 2 | PDZ and LIM domain 1 | PDLIM1 | Cytoskeletal scaffold for assembling protein complexes. Supports synapse formation and maintenance for neuron communication. |

Dysregulated in a variety of tumors and plays essential roles in tumor initiation and progression [35]. |

| 3 | Apolipoprotein C-IV | APOC4 | Plays a role in lipid metabolism, particularly related to triglyceride transport and clearance. | Over-expression of gene may influence circulating lipid levels and may be associated with coronary artery disease risk [36]. |

| 4 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase A | NME1 | This enzyme maintains nucleotide homeostasis, supporting DNA/RNA synthesis, energy metabolism, and signal transduction. | Overexpression of nucleoside diphosphate kinases promotes neurite outgrowth and has been linked to lung tumor progression, while inactive forms suppress nerve growth factor activity [37]. |

| 5 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 | PSMD3 | It is involved in the ATP-dependent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins. participates in numerous cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, or DNA damage repair | Analysis revealed that PSMD3 is highly expressed in multiple myeloma patients, with elevated levels significantly associated with poor patient survival [38]. |

| 6 | RNA transcription, translation and transport factor protein | RTRAF | It is crucial for gene expression, ensuring precise and efficient translation of genetic information into functional proteins. | Dysregulation causes neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and developmental abnormalities [39]. |

| 7 | Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 | TREM2 | The gene encodes a myeloid cell receptor vital for immune regulation, skeletal and neural development, and microglial functions such as inflammation, phagocytosis, and survival. | It has been implicated in neurodegenerative disorders such as Nasu-Hakola disease and Alzheimer’s disease, and may also contribute to Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [40]. |

| 8 | Ig-like domain-containing protein |

LOC102724971 | Their primary role is molecular recognition and binding, supporting key processes such as cell-cell interactions, adhesion, and immune responses. | Viruses exploit Ig-like domain proteins to evade host immunity by suppressing or inhibiting immune responses e.g., SARS-CoV-2 [41]. |

| 9 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein VTA1 homolog | VTA1 | It plays a key role in the endosomal multivesicular body pathway, where it mediates the sorting of membrane proteins destined for degradation. | Dysregulation is linked to malignant choroidal melanoma and neurodegenerative conditions such as frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [42]. |

| 10 | Glutamate--cysteine ligase | GCLC | It catalyzes the first step of glutathione biosynthesis, joining L-glutamate and L-cysteine in an ATP-dependent reaction to form gamma-glutamylcysteine. | Reduced expression has been linked to development of oxidative stress and schizophrenia [43]. |

| Pathway | Protein (Gene symbol) | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Spinocerebellar ataxia | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 1 (PSMD1) (This protein is a subunit of the 26S proteasome, a large protein complex that breaks down ubiquitinated proteins, tagged for destruction). |

Innate immune gene and cancer biomarker, including for oropharyngeal cancer, cystic fibrosis and Alzheimer’s disease [44]. |

| Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 7 (PSMD7) | High expression linked to poor cancer prognosis; potential survival biomarker [45]. | |

| Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 12 (PSMD12) | Dysregulation impairs protein degradation, contributing to neurodevelopmental disorders [46]. | |

| Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 13 (PSMD13) | dysregulation have been linked to endometrial cancer risk and treatment resistance in psychiatric disorders [47]. | |

| Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 6 (SLC25A6) (Mitochondrial carrier protein mediating ADP/ATP exchange across the inner membrane) |

Dysregulation activates inflammatory signalling pathways resulting in the release of inflammatory cytokines, contributing to the progression of inflammation. It has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, Influenza and Bubonic Plague [48]. |

| Pathway | Protein | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative –multiple diseases | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1): A Rho-GTPase involved in cytoskeletal remodeling and survival. |

Closely associated with neuronal dysfuntion. RABV infection led to the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton as well as the biphasic kinetics of the Rac1 signal transduction leading to neurological disorder [49]. |

| Glutathione Peroxidase 1 (GPX1): A key antioxidant enzyme that helps protect cells from the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

GPX1 is overexpressed in most human cancers, eg Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma [50]. | |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II B (CAMK2B): Function in long-term potentiation and neurotransmitter release essential for learning and memory |

Activity is dysregulated in Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and ischaemic stroke [51]. | |

| Protein phosphatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha isoform (PPP3R1). It regulates neuronal calcium signalling, synaptic transmission, receptor internalization, and the synaptic vesicle cycle. |

It is associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, schizophrenia, and has also been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease [52]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).