Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

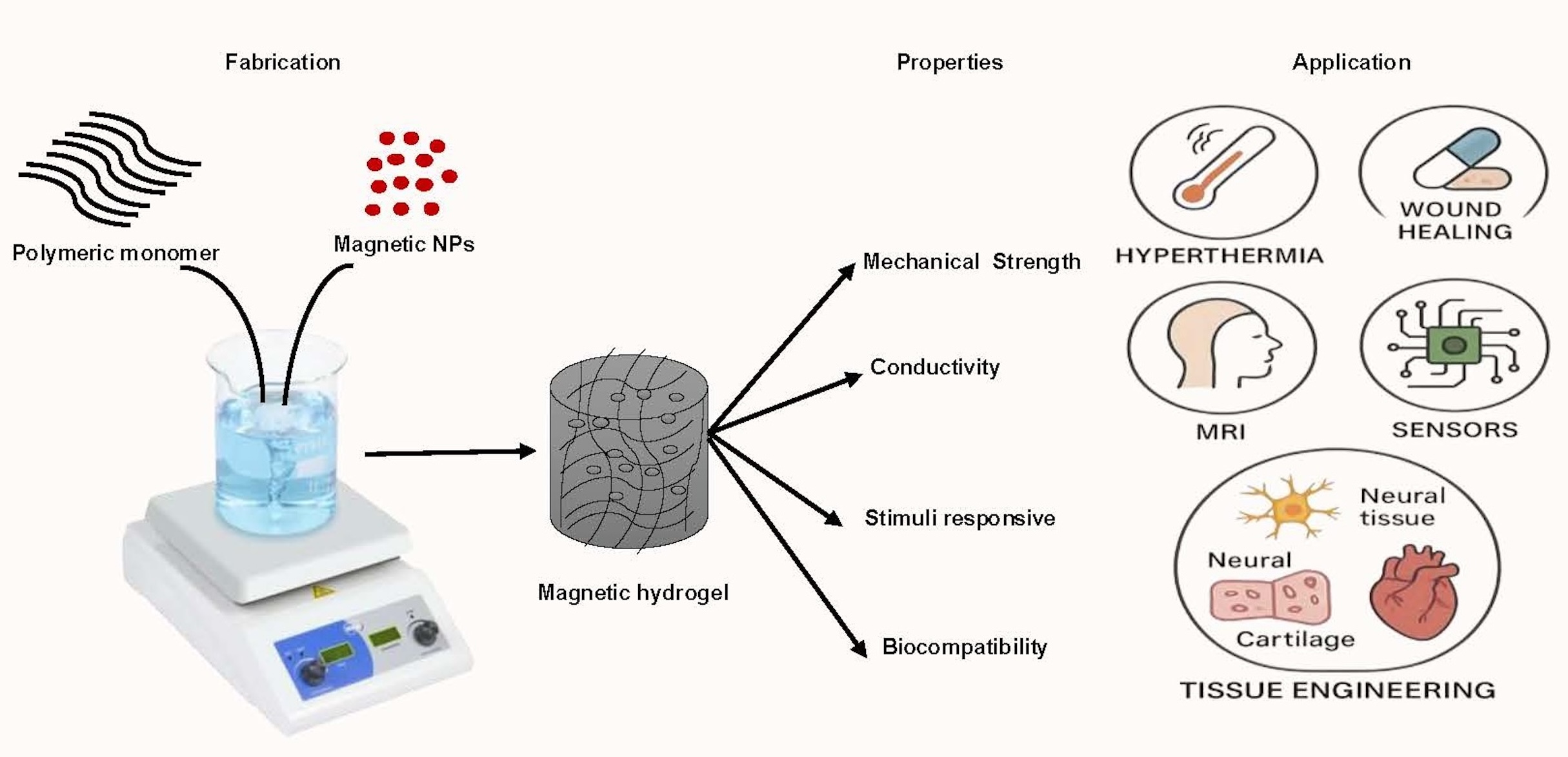

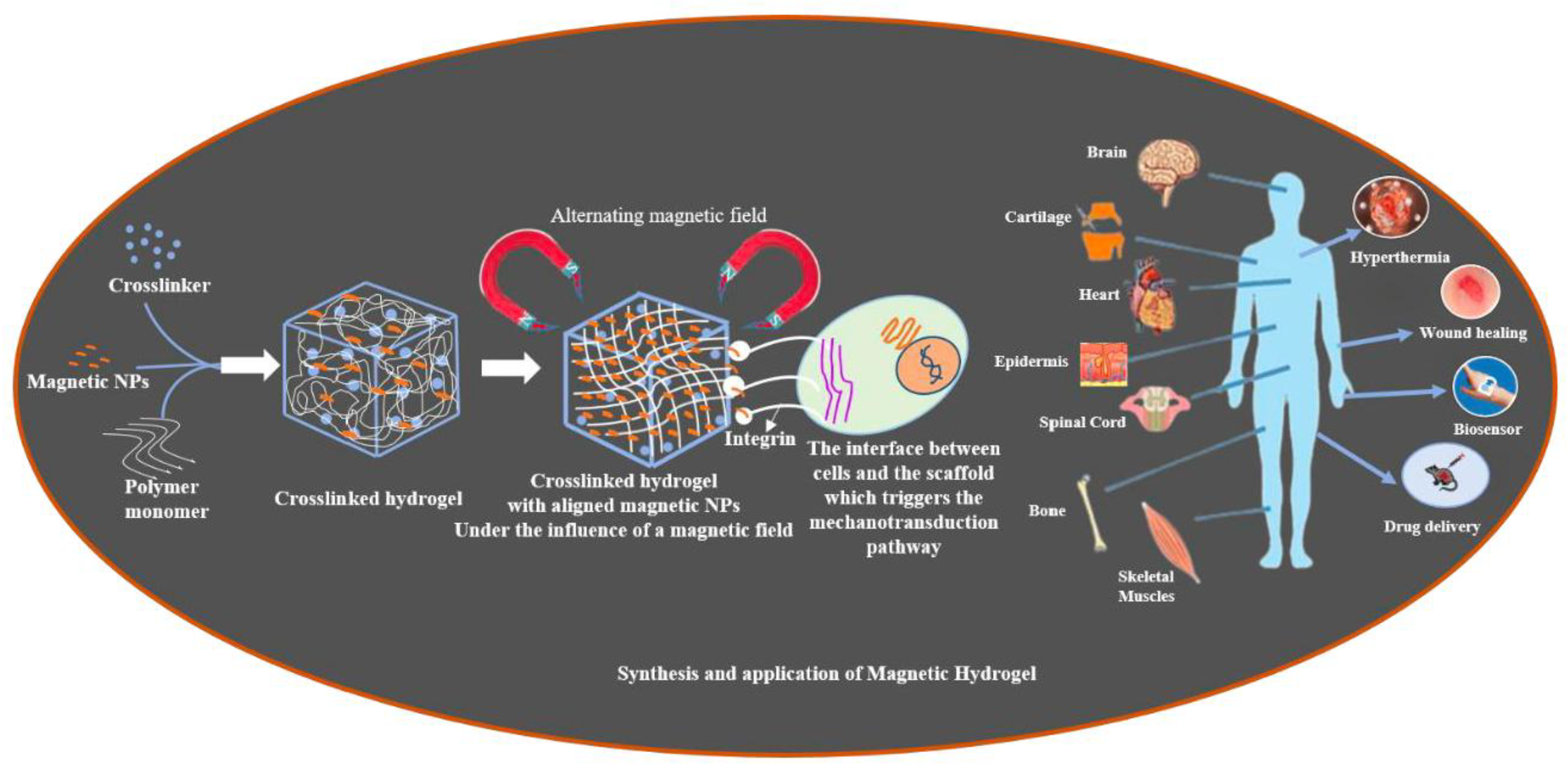

2. Fabrication and Characteristics of MHs

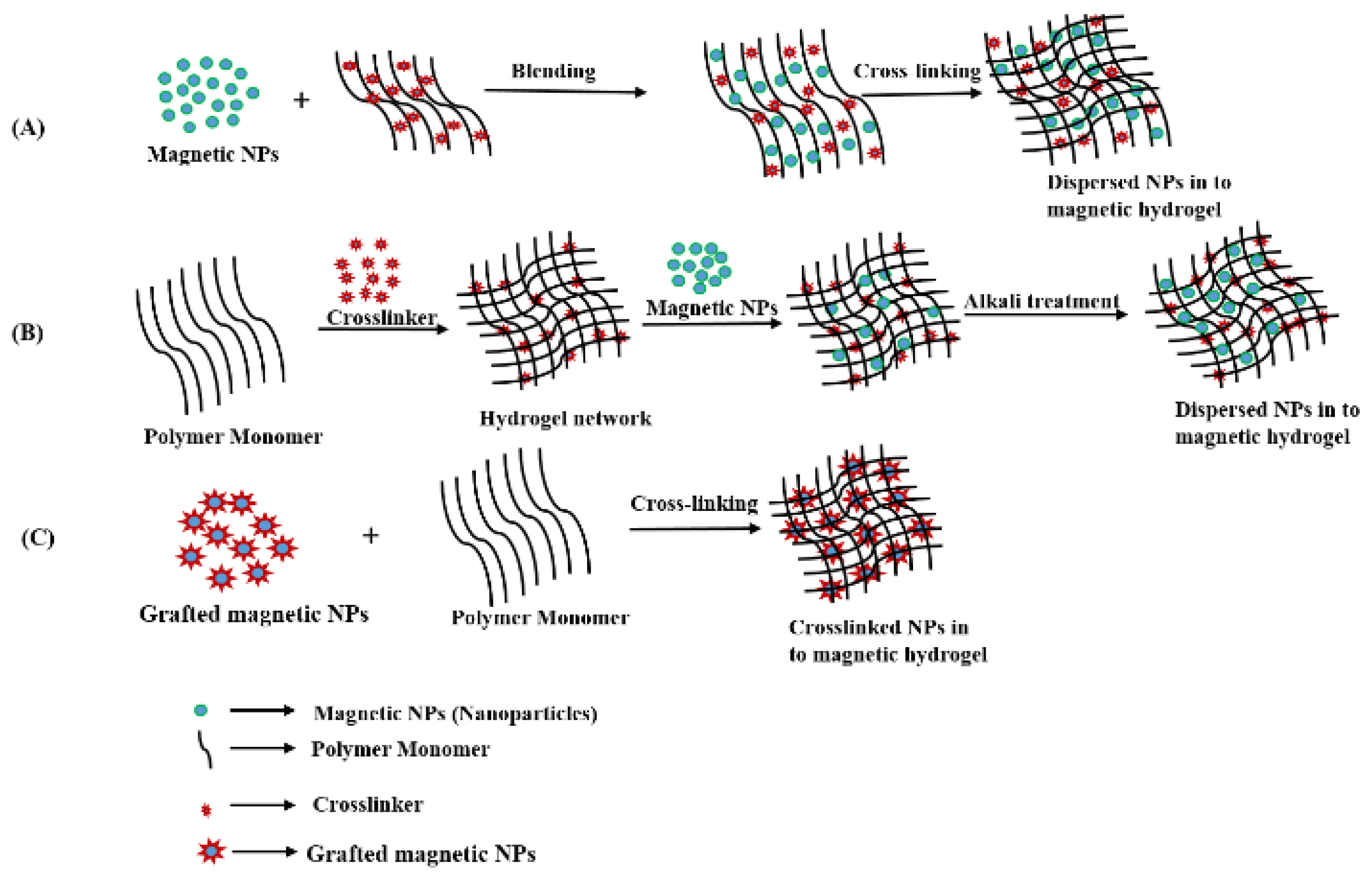

2.1. Strategies for Fabrication of Magnetic Hydrogels with Homogeneous Structure

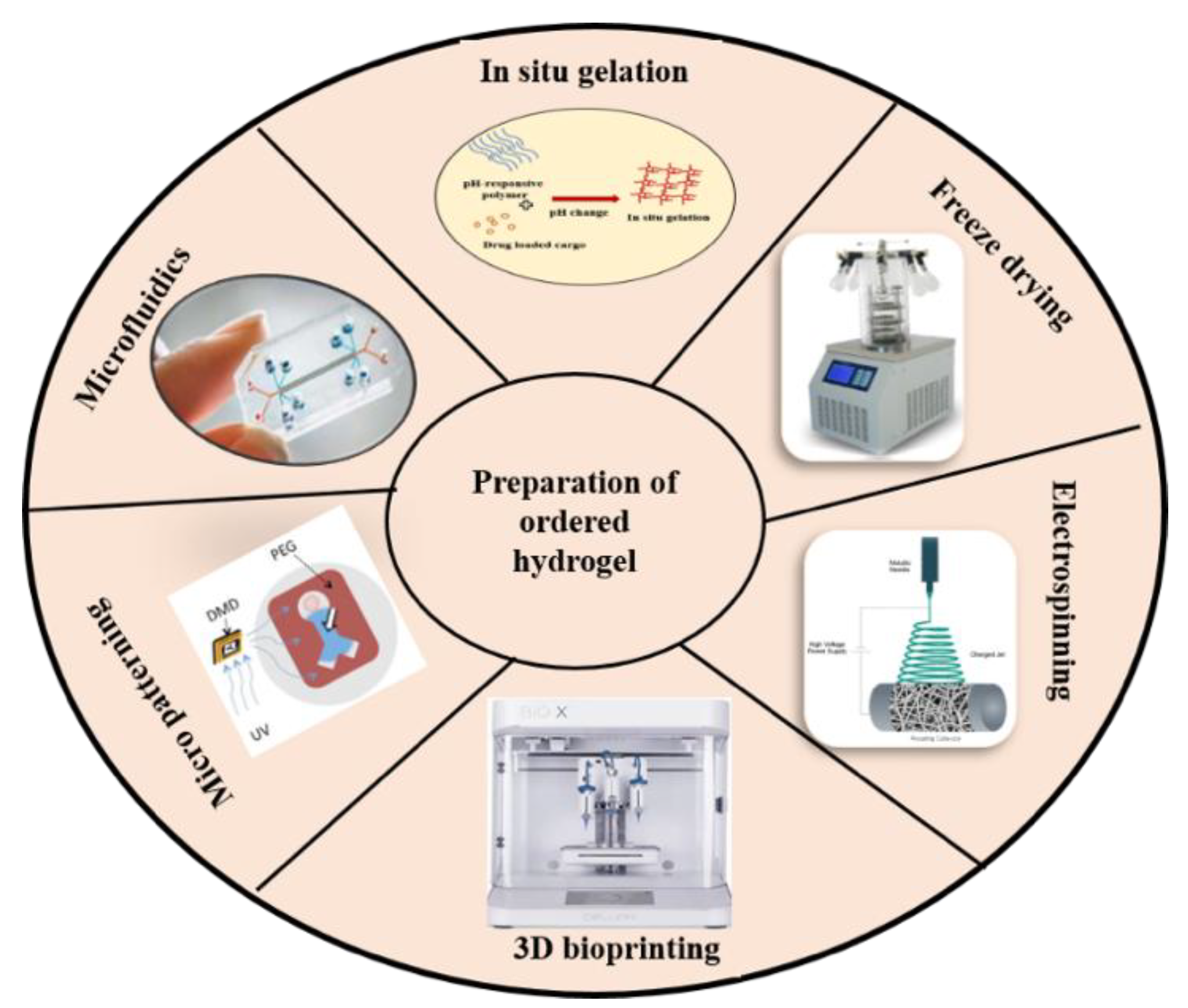

2.2. Strategies for Fabrication of Magnetic Hydrogels with Ordered Structure

) in a polyacrylamide hydrogel [38]. These MHs with oriented structure find applications in tissue engineering [39,40], drug delivery [41,42], hyperthermia [22,43] , and others (e.g., photonic, actuation).

) in a polyacrylamide hydrogel [38]. These MHs with oriented structure find applications in tissue engineering [39,40], drug delivery [41,42], hyperthermia [22,43] , and others (e.g., photonic, actuation).2.3. Fundamental Characteristic of MHS

2.3.1. Surface Properties

2.3.2. Biocompatibility

2.3.3. Diffusive Properties

2.3.4. Biodegradability

2.3.5. Stimuli Sensitivity

2.4. Properties and Functionalities of Magnetic Hydrogels

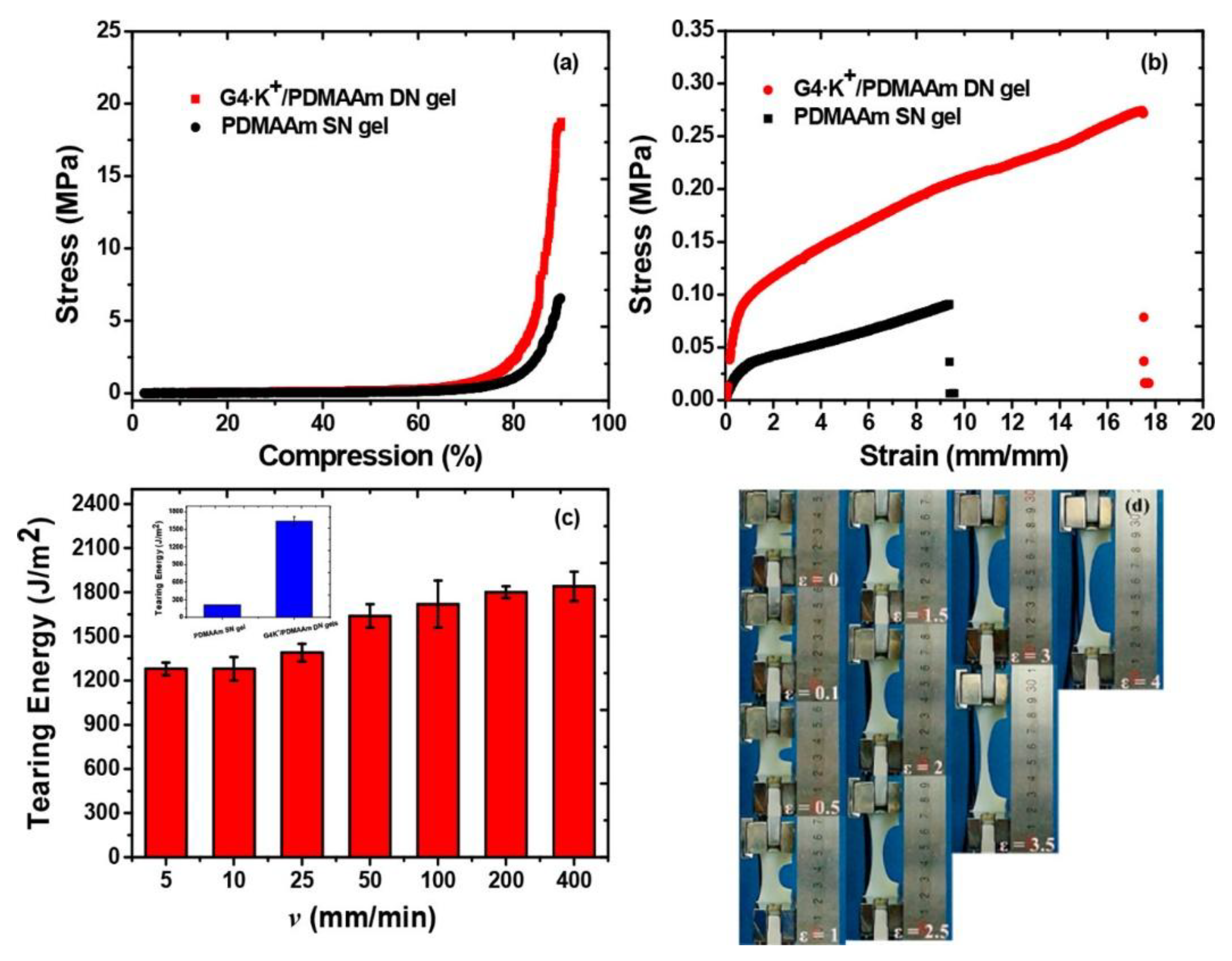

2.4.1. Mechanical Properties

- (1)

- The ‘‘sacrificial bond’’ is used to reduce the increasing energy in the hydrogels by dissipation which enhances the mechanical characteristics of the hydrogels. Different non-covalent bonds such as hydrogen bond self-assembly, complexation, supramolecular recognition, and hydrophobic association have been used in the design of high-strength hydrogels [90].

- (2)

- The “pulley effect” also helps to lower the internal stress in the crosslinking network and improve significantly the mechanical properties of hydrogels. Thus, topological hydrogel such as polyrotaxane is formed by many cyclic molecules threaded on a single polymer chain terminated by bulky end groups. Such hydrogel has high strength due to O ring-shaped crosslinking points that have high mobility along the polymer chain and equalize the tension in the hydrogel [91].

- (3)

- The reversible non covalent bonds can also give high strength to the hydrogels and a self-healing character by reform after breaking [92].

- (4)

- The hydrogels mechanical properties also change when NPs are incorporated into them. Several authors have incorporated nanofillers (e.g., MWCNTs, SWCNTs, GO, metal particles, Laponite, polymeric nanoparticles, clay) in the hydrogels to achieve better mechanical properties. These nanocomposite hydrogels are made through the process of radical polymerization of the monomer solution incorporating nanoparticles. Specifically, the reagents are adsorbed onto the surface of the nanoparticles then they start the process of polymerization. It was found that the capping of the polymer ends occurred on the nanoparticles with the formation of clay/brush particles when clay was used as a nanofiller and the interactions that occur were adsorption/desorption and were in no way covalent [93].

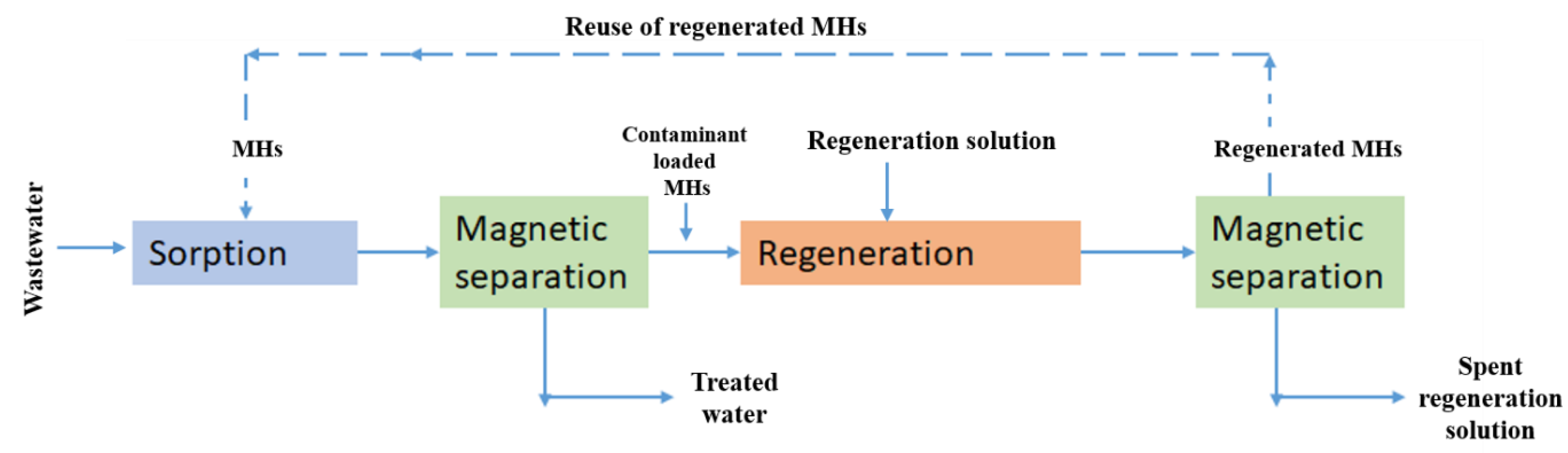

2.4.2. Adsorption

2.4.3. Magnetocaloric Effects

2.4.4. Swelling Behavior

2.4.5. Intelligent Response

/s. Following NIR irradiation, the hydrogel matrix underwent degradation resulting in the retention of drug-loaded particles and magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) at the tumor site. Ultimately, after 6 hours of treatment facilitated by EMA, the disintegrated MNPs were segregated from the targeted site, while the residual anticancer drug-loaded particles persisted in releasing the drug to exert therapeutic effects. This hydrogel actuator addresses the limitations associated with MNPs potential accumulation and toxicity, by eliminating MNPs while simultaneously preserving the benefits conferred by electromagnetic drive, including targeted delivery and drug release [106,107].

/s. Following NIR irradiation, the hydrogel matrix underwent degradation resulting in the retention of drug-loaded particles and magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) at the tumor site. Ultimately, after 6 hours of treatment facilitated by EMA, the disintegrated MNPs were segregated from the targeted site, while the residual anticancer drug-loaded particles persisted in releasing the drug to exert therapeutic effects. This hydrogel actuator addresses the limitations associated with MNPs potential accumulation and toxicity, by eliminating MNPs while simultaneously preserving the benefits conferred by electromagnetic drive, including targeted delivery and drug release [106,107].3. Biomedical Applications of MHs

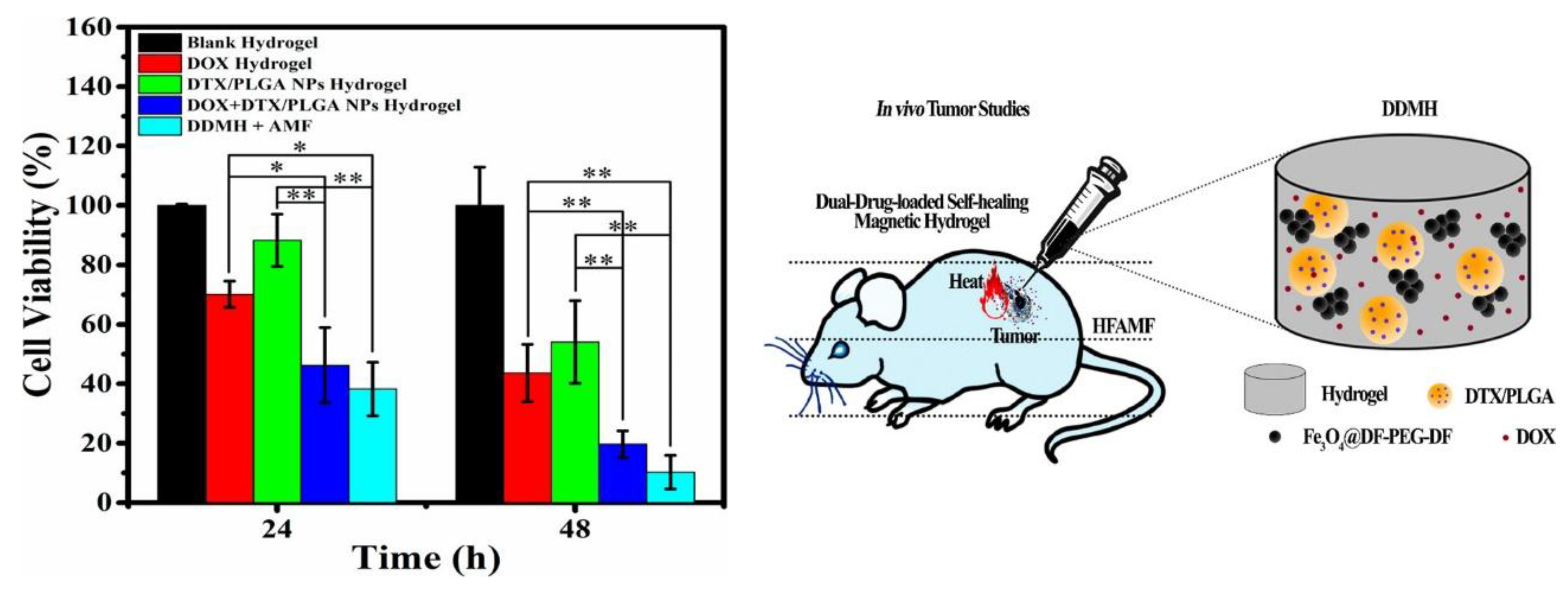

3.1. MHs in Drug Delivery

3.2. MHs in Hyperthermia

g/mL DOX loaded patches, the viability of B16F10 murine melanoma cells was reduced of 79.55 % in five days [121]. Mild hyperthermia usually uses a thermal window of 41-46 °C. However, tumor cells under heat stress may activate autophagy process as a mechanism of defense and restoration that may result in some thermal resistance. To overcome this and to boost mild magnetic hyperthermia therapy (MHT) Wang et al. chose to fabricate a nitric oxide (NO) releasing MH because NO impairs the autophagy process. Thus, they developed an injectable hydrogel of thermosensitive poly(ethylene glycol)-polypeptide copolymers modified with NO groups on their side chains (Figure 16). They also synthesized ferrimagnetic Zno.5Fe2.5O4 MNPs (cubes, 70 nm) that are very popular for their ability to deliver high magnetic–thermal conversion and incorporated them directly within the hydrogel to form MNPs@NO-Gel. The MNPs@NO-Gel was tested in vivo in mice bearing CT-26 tumor cells (~100 mm3) who received three mild MHT treatment (20 min at 42.5 °, H 17.6 kA/m, f 282 kHz) at days 0, 2, and 4 after the injection of MNPs@NO-Gel. At day 14 mice were euthanized and tumor analyzed. The results showed that in the group of mice treated by MNPs@NO-Gel with MHT three times, the tumors were eliminated, and the survival of mice was 100% with no recurrence. Furthermore, the study globally showed that several sessions of MHT were possible after only one injection of gel due to the homogeneous distribution and strong adhesion of MNPs in the gel-phase. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) was continuously released from NO-Gel and this release was boosted by MHT. The degradation of MNPs@NOGel in vivo was slow with 30% of MNPs@NO-Gel remaining after 35 days, whereas the dispersion of the released MNPs concentrated in the spleen. Due to the released of NO controlling the autophagy activity, there was suppression of the formation of autophagosomes and lysosomes during MHT, which boosted the efficiency of MHT [122]. In a recent study, Barra et al. assessed the performances of chitosan-based magnetic composite films in terms of film thickness, MNPs content, and heating efficiency. Especially, the spatiotemporal heating was evaluated with a thermal camera and heat map were generated. Furthermore, the polymeric films were used in MHT treatment under AMF (663 kHz, 12.8 kA/m) with MNT-1 human melanoma cells. The polymeric films of chitosan/glycerol/MNPs obtained with a casting method were very thin with thicknesses ranging from 34

g/mL DOX loaded patches, the viability of B16F10 murine melanoma cells was reduced of 79.55 % in five days [121]. Mild hyperthermia usually uses a thermal window of 41-46 °C. However, tumor cells under heat stress may activate autophagy process as a mechanism of defense and restoration that may result in some thermal resistance. To overcome this and to boost mild magnetic hyperthermia therapy (MHT) Wang et al. chose to fabricate a nitric oxide (NO) releasing MH because NO impairs the autophagy process. Thus, they developed an injectable hydrogel of thermosensitive poly(ethylene glycol)-polypeptide copolymers modified with NO groups on their side chains (Figure 16). They also synthesized ferrimagnetic Zno.5Fe2.5O4 MNPs (cubes, 70 nm) that are very popular for their ability to deliver high magnetic–thermal conversion and incorporated them directly within the hydrogel to form MNPs@NO-Gel. The MNPs@NO-Gel was tested in vivo in mice bearing CT-26 tumor cells (~100 mm3) who received three mild MHT treatment (20 min at 42.5 °, H 17.6 kA/m, f 282 kHz) at days 0, 2, and 4 after the injection of MNPs@NO-Gel. At day 14 mice were euthanized and tumor analyzed. The results showed that in the group of mice treated by MNPs@NO-Gel with MHT three times, the tumors were eliminated, and the survival of mice was 100% with no recurrence. Furthermore, the study globally showed that several sessions of MHT were possible after only one injection of gel due to the homogeneous distribution and strong adhesion of MNPs in the gel-phase. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) was continuously released from NO-Gel and this release was boosted by MHT. The degradation of MNPs@NOGel in vivo was slow with 30% of MNPs@NO-Gel remaining after 35 days, whereas the dispersion of the released MNPs concentrated in the spleen. Due to the released of NO controlling the autophagy activity, there was suppression of the formation of autophagosomes and lysosomes during MHT, which boosted the efficiency of MHT [122]. In a recent study, Barra et al. assessed the performances of chitosan-based magnetic composite films in terms of film thickness, MNPs content, and heating efficiency. Especially, the spatiotemporal heating was evaluated with a thermal camera and heat map were generated. Furthermore, the polymeric films were used in MHT treatment under AMF (663 kHz, 12.8 kA/m) with MNT-1 human melanoma cells. The polymeric films of chitosan/glycerol/MNPs obtained with a casting method were very thin with thicknesses ranging from 34  to 93

to 93  . The thermal efficiency of the films increases significantly when exposed to an AMF with a maximum of 82 °C recorded within 270 s. The temperature increased with the increase of the film thickness and the increase on MNPs content. Moreover, in the MHT treatment experiment with the 78

. The thermal efficiency of the films increases significantly when exposed to an AMF with a maximum of 82 °C recorded within 270 s. The temperature increased with the increase of the film thickness and the increase on MNPs content. Moreover, in the MHT treatment experiment with the 78  film thickness (labelled 2.25 M-0.75G-T), the temperature reached 42 °C within 300 s, and after this temperature was maintained for 10 min, the viability of MNT-1 cells decreased drastically to 8% [123].

film thickness (labelled 2.25 M-0.75G-T), the temperature reached 42 °C within 300 s, and after this temperature was maintained for 10 min, the viability of MNT-1 cells decreased drastically to 8% [123].3.3. MHs in MRI

3.4. MHs in Wound Healing

3.5. MHs in Bio-Sensing

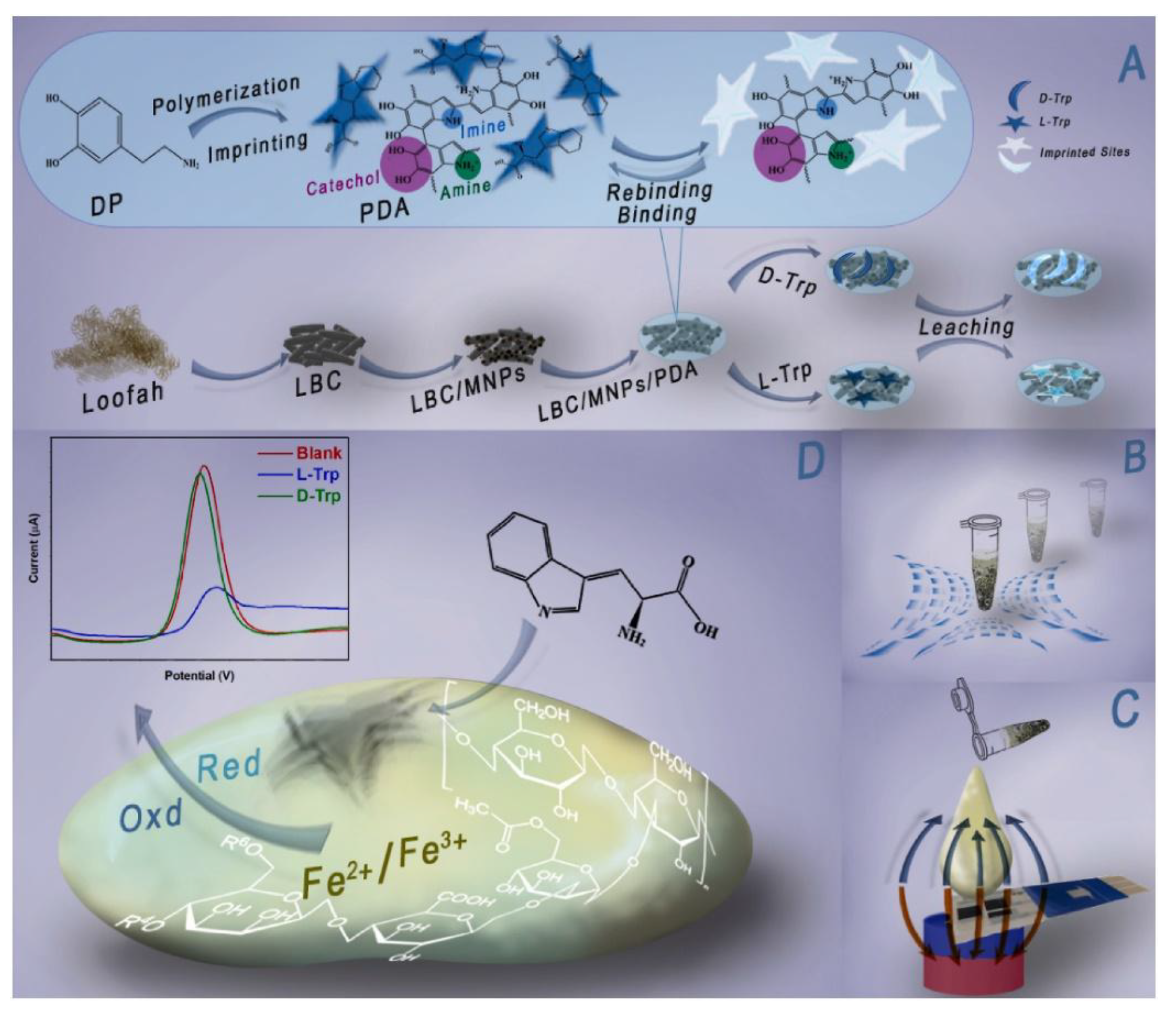

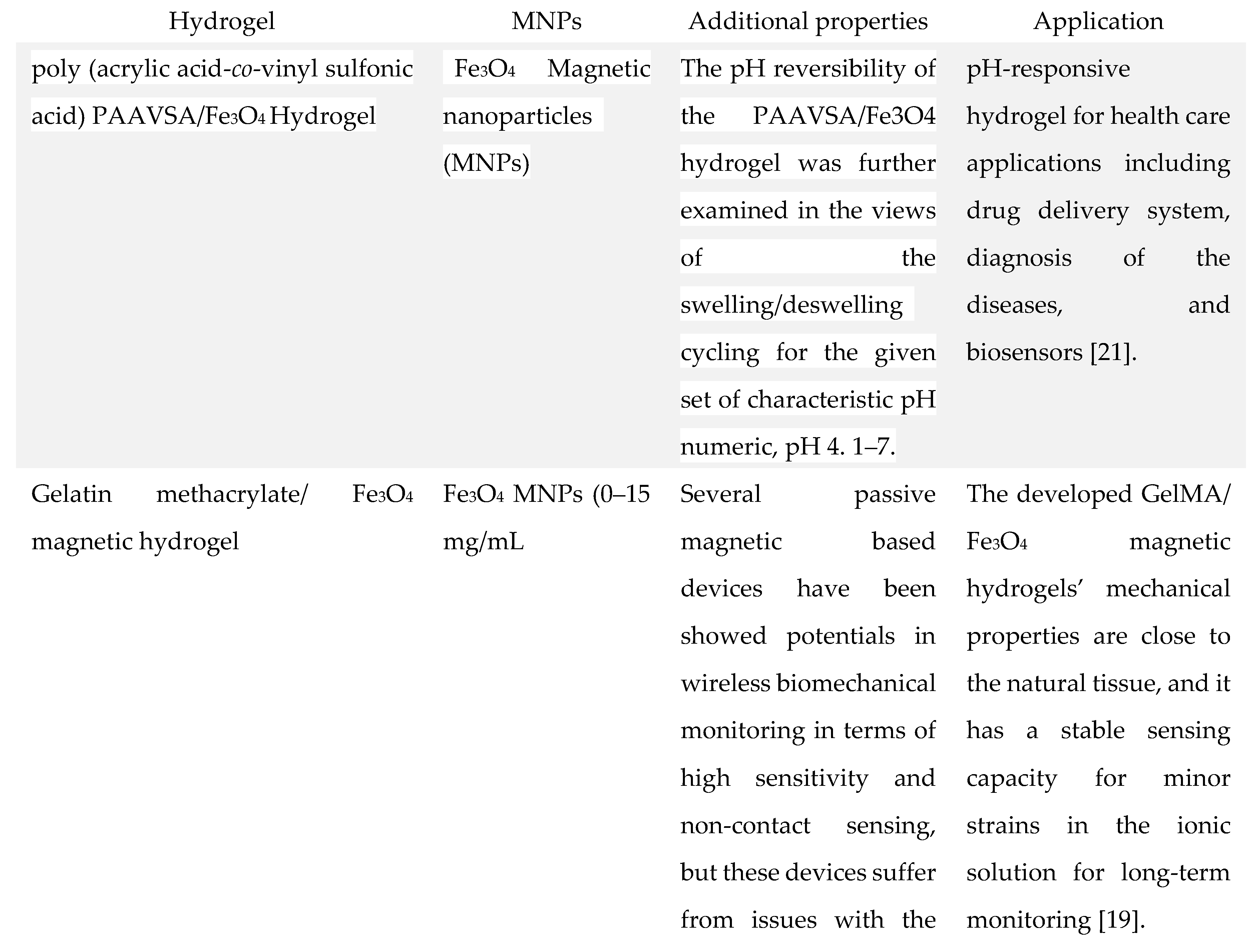

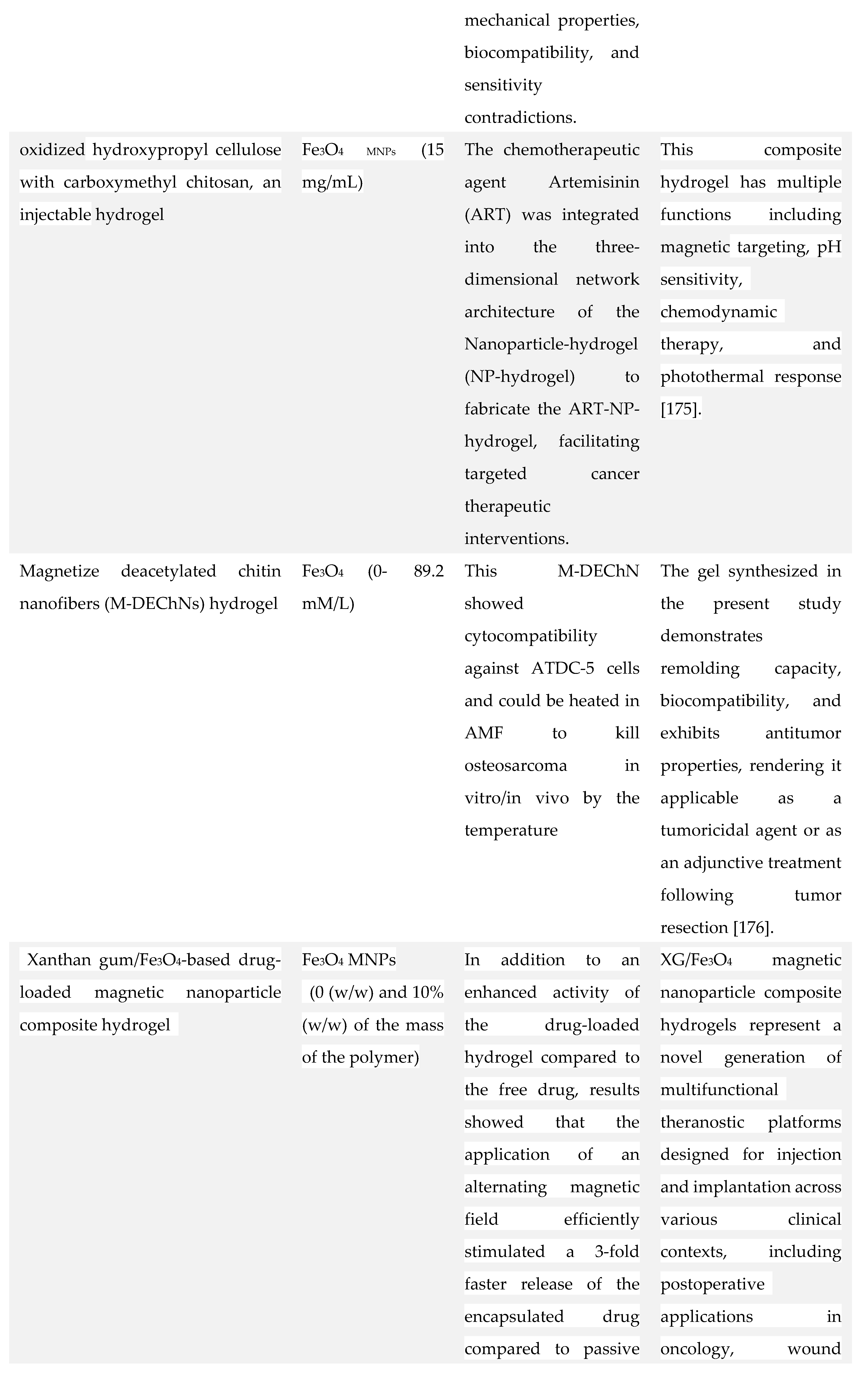

M with an LOD of 3 M, allowing to diagnose hyperglycemia in human blood. Furthermore, the sensor showed high stability and magnetic reusability [140]. In another study, Zhang et al. fabricated wireless and passive flexible strain sensor based on gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)/Fe3O4 as MH. These sensors have the advantages of real-time and continuous monitoring without the disadvantages of wires and power supplies. The sensor is compliant with ultrasoft mechanical behavior (Young’s modulus 1.2 kPa), possesses robust magnetic attributes (12.74 emu/g), good biocompatibility, long term stability (>20 days), can function for long hours in saline solution, and it is sensitive enough to detect small strains down to 50 μm. The study comprises a model on the appropriate positioning of the sensors and on its magnetic permeability and sensitivity. Moreover, cardiomyocytes were seeded on the strain sensor and the effects of the cell density, contractibility, and drugs were evaluated. This research showed the feasibility of using a magnetic-sensing approach for biomechanical measurements and highlights the developments of wireless and fully passive implantable devices [19]. Recently, Hosseini et al. fabricated a magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) sensor (Figure 21) for the enantiomeric detection of the essential amino acid L-Tryptophan (L-Trp). The sensor was developed utilizing oriented biochar derived from Loofah (LBC), Fe3O4, and molecularly imprinted polydopamine (MIPDA) embedded within xanthan gum (XG) hydrogel. The template (L-Trp) was removed by immersion in a solution of methanol/acetic acid (ratio 9:1) under sonication. To form the sensor, the prepared hydrogel (XG-LBC-Fe3O4/MIPDA) was then drop-cast on a screen-printed electrode (SPE). The synthesis of these components was validated through comprehensive physicochemical and electrochemical analyses. Several operational parameters, including pH, response time, sample loading volume, and the quantity of active materials to be incorporated were meticulously optimized. The SPE-XG-LBC-Fe3O4/MIPDA sensor showed a linear detection range of L-Trp from 1–6 μM and from 10-60 μM, with a LOD of 0.44 μM. Moreover, the electrochemical sensor exhibits good reproducibility and selectivity. In addition, the detections of L-Trp in milk, blood and urine samples were good with a relative standard deviation (RSD) ranging from 97% to 106%. The strategy provided in the development of the sensor is promising, convenience, and effective. It uses xanthan hydrogel for enhancing mass transfer and adhesion strength, Fe3O4 supported biochar for orientating magnetic field and accelerating mass transfer and sensitivity and polydopamine MIP for selectivity. This approach makes it easy to assess the L-Trp levels on-site which is quite useful in health assessment and early diagnosis associated with L-Trp [141].

M with an LOD of 3 M, allowing to diagnose hyperglycemia in human blood. Furthermore, the sensor showed high stability and magnetic reusability [140]. In another study, Zhang et al. fabricated wireless and passive flexible strain sensor based on gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)/Fe3O4 as MH. These sensors have the advantages of real-time and continuous monitoring without the disadvantages of wires and power supplies. The sensor is compliant with ultrasoft mechanical behavior (Young’s modulus 1.2 kPa), possesses robust magnetic attributes (12.74 emu/g), good biocompatibility, long term stability (>20 days), can function for long hours in saline solution, and it is sensitive enough to detect small strains down to 50 μm. The study comprises a model on the appropriate positioning of the sensors and on its magnetic permeability and sensitivity. Moreover, cardiomyocytes were seeded on the strain sensor and the effects of the cell density, contractibility, and drugs were evaluated. This research showed the feasibility of using a magnetic-sensing approach for biomechanical measurements and highlights the developments of wireless and fully passive implantable devices [19]. Recently, Hosseini et al. fabricated a magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) sensor (Figure 21) for the enantiomeric detection of the essential amino acid L-Tryptophan (L-Trp). The sensor was developed utilizing oriented biochar derived from Loofah (LBC), Fe3O4, and molecularly imprinted polydopamine (MIPDA) embedded within xanthan gum (XG) hydrogel. The template (L-Trp) was removed by immersion in a solution of methanol/acetic acid (ratio 9:1) under sonication. To form the sensor, the prepared hydrogel (XG-LBC-Fe3O4/MIPDA) was then drop-cast on a screen-printed electrode (SPE). The synthesis of these components was validated through comprehensive physicochemical and electrochemical analyses. Several operational parameters, including pH, response time, sample loading volume, and the quantity of active materials to be incorporated were meticulously optimized. The SPE-XG-LBC-Fe3O4/MIPDA sensor showed a linear detection range of L-Trp from 1–6 μM and from 10-60 μM, with a LOD of 0.44 μM. Moreover, the electrochemical sensor exhibits good reproducibility and selectivity. In addition, the detections of L-Trp in milk, blood and urine samples were good with a relative standard deviation (RSD) ranging from 97% to 106%. The strategy provided in the development of the sensor is promising, convenience, and effective. It uses xanthan hydrogel for enhancing mass transfer and adhesion strength, Fe3O4 supported biochar for orientating magnetic field and accelerating mass transfer and sensitivity and polydopamine MIP for selectivity. This approach makes it easy to assess the L-Trp levels on-site which is quite useful in health assessment and early diagnosis associated with L-Trp [141].4. Other Applications of MHs in Tissue Engineering

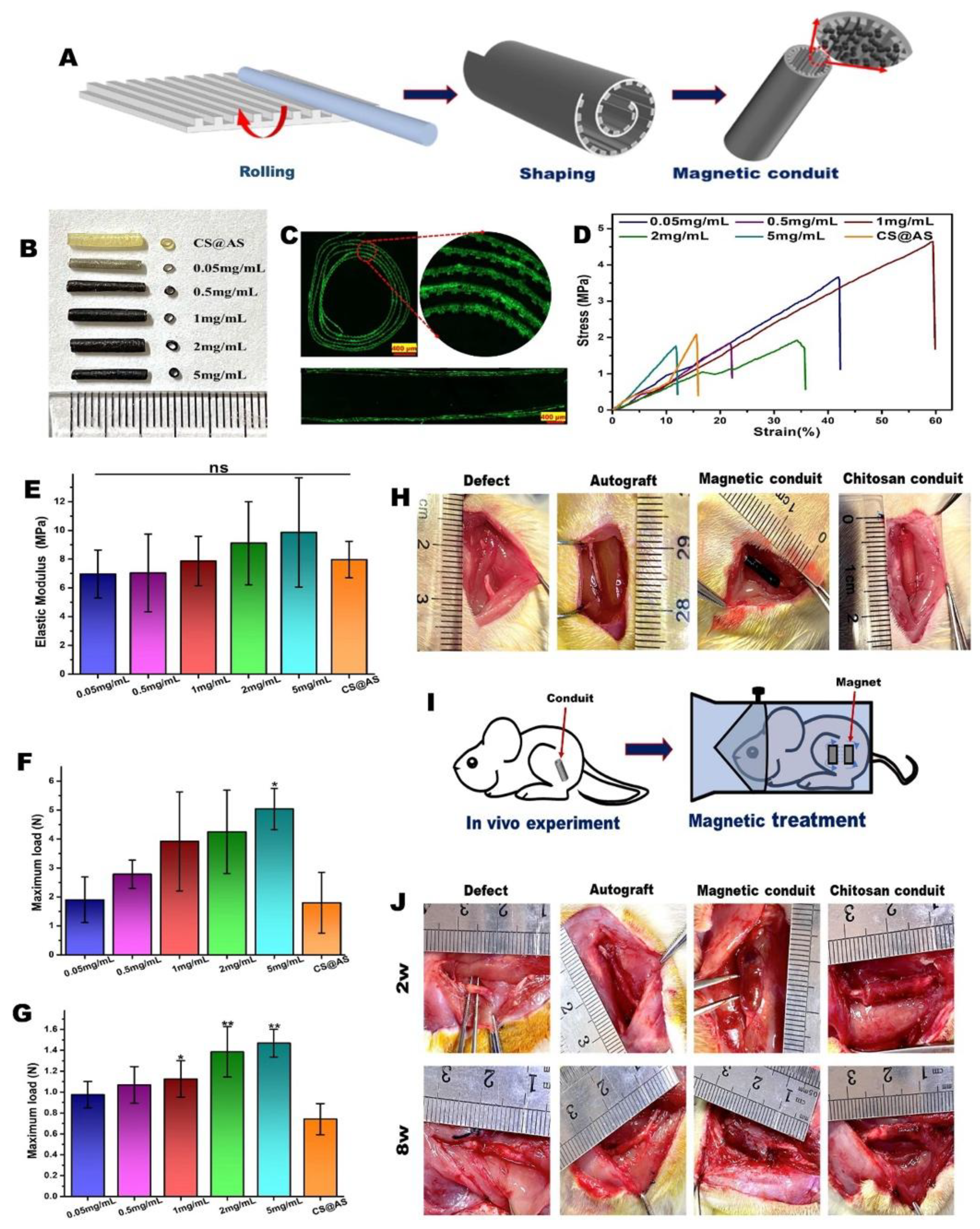

4.1. Applications of MHs in Neural Tissue Engineering

4.2. Applications of MHs in Cartilage Tissue Engineering

) do not move while larger objects (5-15

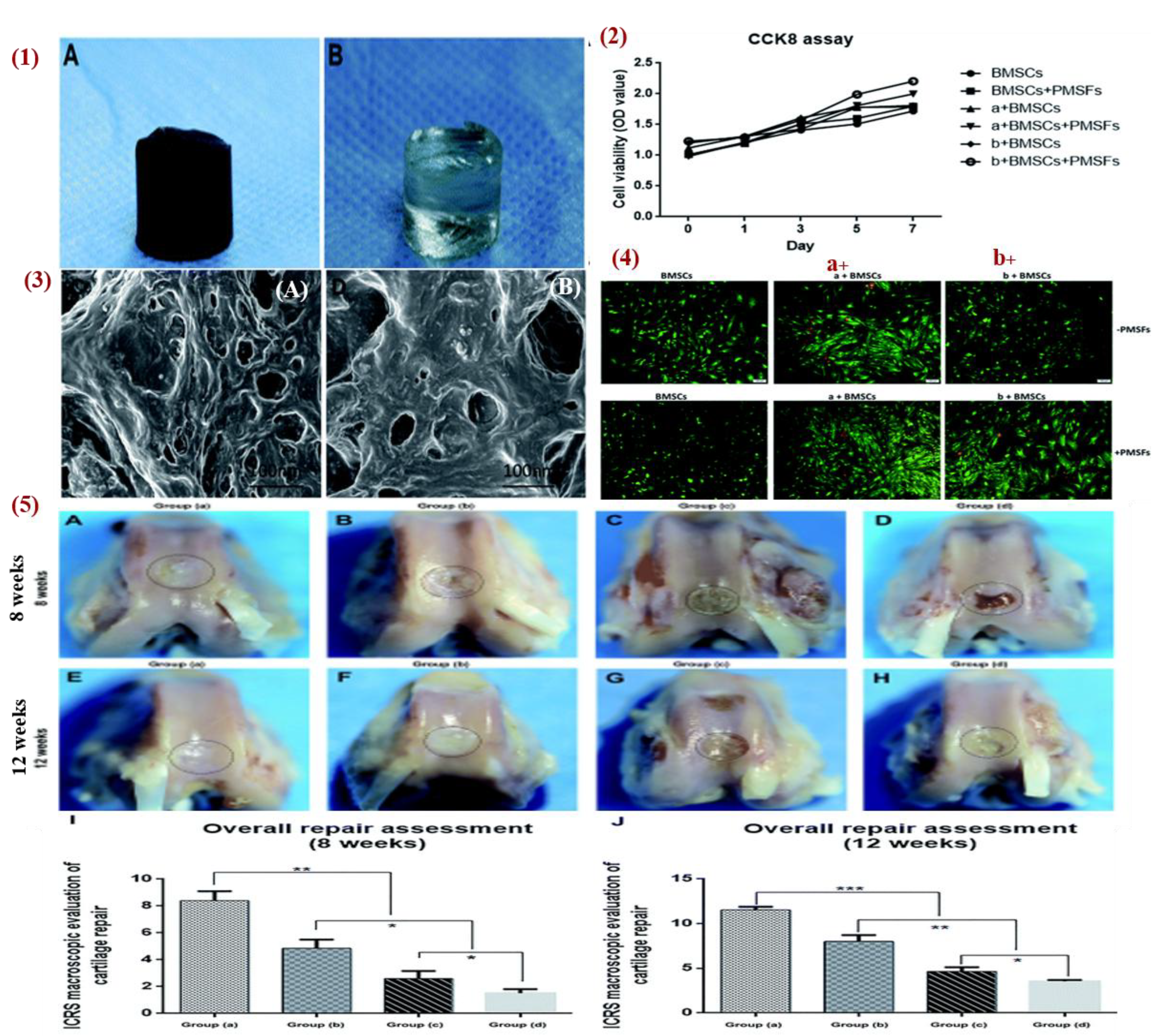

) do not move while larger objects (5-15  ) ascended toward the surface of the hydrogel solution. The technique was used for cartilage regeneration by patterning magnetically MSCs with 5 min exposure to the magnet, and then the cells were cultured for 3 to 6 weeks in chondrogenic medium. The analysis showed a cellular gradient (from top to bottom), and the formation of cartilaginous matrix with a gradient of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) [153]. In another study, Huang et al. studied the combined effect of hydrogel material with pulse electromagnetic fields (PEMFs). Figure 23 showed that PEMFs promoted the repair of defective articular cartilage. Thus, they fabricated a gelatin/

) ascended toward the surface of the hydrogel solution. The technique was used for cartilage regeneration by patterning magnetically MSCs with 5 min exposure to the magnet, and then the cells were cultured for 3 to 6 weeks in chondrogenic medium. The analysis showed a cellular gradient (from top to bottom), and the formation of cartilaginous matrix with a gradient of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) [153]. In another study, Huang et al. studied the combined effect of hydrogel material with pulse electromagnetic fields (PEMFs). Figure 23 showed that PEMFs promoted the repair of defective articular cartilage. Thus, they fabricated a gelatin/ -cyclodextrin (

-cyclodextrin ( -CD)/Fe3O4 MNPs hydrogel and its characterization revealed good mechanical properties (compressive modulus 2.79 MPa) with microporous surface and unevenness that promotes cell adhesion and growth. The result of infrared spectroscopy analysis revealed that the MNPs were uniformly dispersed into the hydrogel, which had reasonably good super paramagnetic characteristics. In addition, when bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) were cultured on the hydrogel and PEMFs were applied, the expression of cartilage specific gene markers (COL1, COL2, and Aggrecan) were significantly enhanced and BMSCs differentiated into chondrocytes. The hydrogel was also tested in vivo in a knee-defect rabbit model for 8 and 12 weeks. Four groups were tested: group A (gelatin/

-CD)/Fe3O4 MNPs hydrogel and its characterization revealed good mechanical properties (compressive modulus 2.79 MPa) with microporous surface and unevenness that promotes cell adhesion and growth. The result of infrared spectroscopy analysis revealed that the MNPs were uniformly dispersed into the hydrogel, which had reasonably good super paramagnetic characteristics. In addition, when bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) were cultured on the hydrogel and PEMFs were applied, the expression of cartilage specific gene markers (COL1, COL2, and Aggrecan) were significantly enhanced and BMSCs differentiated into chondrocytes. The hydrogel was also tested in vivo in a knee-defect rabbit model for 8 and 12 weeks. Four groups were tested: group A (gelatin/ -CD)/Fe3O4 with BMSCs and PEMFs), group B (gelatin/

-CD)/Fe3O4 with BMSCs and PEMFs), group B (gelatin/ -CD)/Fe3O4 with BMSCs), group C (gelatin/

-CD)/Fe3O4 with BMSCs), group C (gelatin/ -CD)/Fe3O4), and group D (no treatment). The results showed that group A has the best cartilage repair at 8 weeks and at 12 weeks the defect was completely filled with new cartilage and restored. In group B, the defect was restored with new cartilage at 50% and 70% at week 8 and week 12, respectively. Therefore, PEMFs combined with MHs promote cartilage repair. In group C, the regenerated tissue was fibrous with a gap between the new tissue and the host at week 8 while at week 12 the regenerated tissue was mainly fibrous hyperproliferative tissue with only few cartilage tissue. In group D, there were cavities and fibrous tissue at week 8, while at week 12 there was only inflammatory tissue [100]. Furthermore, Choi et al. fabricated a ferrogel of oxidized hyaluronate (OHA)/glycol chitosan (GC)/adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH)/SPIONs with 3D printing. Mouse teratocarcinoma ATDC5 cells were encapsulated in the ferrogel for chondrocytes differentiation and a magnetic field was applied. The results showed that the application of this magnetic stimulation enhances the expression level of gene SOX-9 and COL-2 proving that the ferrogel has potential for cartilage tissue engineering [154].

-CD)/Fe3O4), and group D (no treatment). The results showed that group A has the best cartilage repair at 8 weeks and at 12 weeks the defect was completely filled with new cartilage and restored. In group B, the defect was restored with new cartilage at 50% and 70% at week 8 and week 12, respectively. Therefore, PEMFs combined with MHs promote cartilage repair. In group C, the regenerated tissue was fibrous with a gap between the new tissue and the host at week 8 while at week 12 the regenerated tissue was mainly fibrous hyperproliferative tissue with only few cartilage tissue. In group D, there were cavities and fibrous tissue at week 8, while at week 12 there was only inflammatory tissue [100]. Furthermore, Choi et al. fabricated a ferrogel of oxidized hyaluronate (OHA)/glycol chitosan (GC)/adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH)/SPIONs with 3D printing. Mouse teratocarcinoma ATDC5 cells were encapsulated in the ferrogel for chondrocytes differentiation and a magnetic field was applied. The results showed that the application of this magnetic stimulation enhances the expression level of gene SOX-9 and COL-2 proving that the ferrogel has potential for cartilage tissue engineering [154].4.3. Applications of MHs in Bone Tissue Engineering

4.4. Application of MHs in Cardiac Tissue Engineering

-MHC, and c-TnT in ECCs cultured on SF-SPIONs-casein compared to those cultured on SF nanofibrous scaffolds. In addition, real-time PCR analysis indicated the upregulation of functional genes involved in cardiac muscularity including GATA-4, cardiac troponin, Nkx 2. 5 and

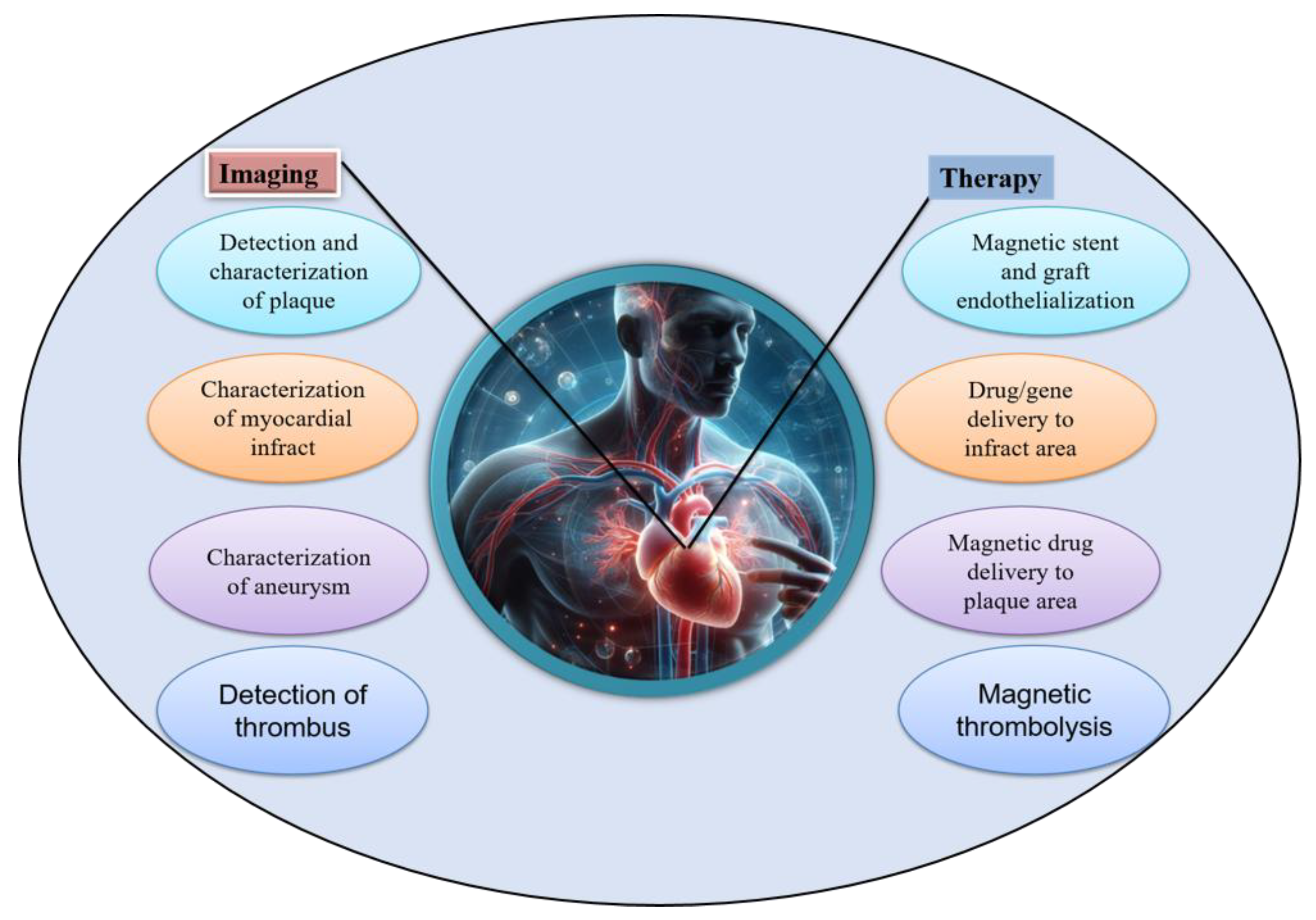

-MHC, and c-TnT in ECCs cultured on SF-SPIONs-casein compared to those cultured on SF nanofibrous scaffolds. In addition, real-time PCR analysis indicated the upregulation of functional genes involved in cardiac muscularity including GATA-4, cardiac troponin, Nkx 2. 5 and  -MHC for ECCs cultured on SF/SPION-casein scaffolds compared to ECCs cultured on SF scaffolds only [173]. Therefore, nanoparticles are important components for cardiac tissue engineering and that there have been many advancements on the use of MNPs both for diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases as shown in Figure 25. Especially, iron oxide based MNPs have been described in detail as nanosized agents with superparamagnetic properties used for therapy in the frame of cardiac vascular diseases and also used for imaging and the visualization of plaques, thrombus, drug delivery, new reendothelialization of stents, and blood vessel regeneration [174].

-MHC for ECCs cultured on SF/SPION-casein scaffolds compared to ECCs cultured on SF scaffolds only [173]. Therefore, nanoparticles are important components for cardiac tissue engineering and that there have been many advancements on the use of MNPs both for diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases as shown in Figure 25. Especially, iron oxide based MNPs have been described in detail as nanosized agents with superparamagnetic properties used for therapy in the frame of cardiac vascular diseases and also used for imaging and the visualization of plaques, thrombus, drug delivery, new reendothelialization of stents, and blood vessel regeneration [174].5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| AA | acrylamide |

| AMF | alternating magnetic field |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CS | chitosan |

| DOX | doxorubicin |

| EPC(s) | endothelial progenitor cell(s) |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| GelMA | gelatin methacrylate |

| GOx | glucose oxidase |

| LCST | low critical solution temperature |

| MH(s) | magnetic hydrogel(s) |

| MHT | magnetic hyperthermia therapy |

| MNPs | magnetic nanoparticles |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSC(s) | mesenchymal stem cell(s) |

| MWCNTs | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| PCL | polycaprolactone |

| PEG | poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PGA | poly(glycolic acid) |

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid |

| PNIPAM | poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) |

| PVA | polyvinyl alcohol |

| SF | silk fibroin |

| SMC(s) | smooth muscle cell(s) |

| SPIONs | superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles |

| SWCNTs | single-walled carbon nanotubes |

| VSA | vinyl sulfonic acid |

References

- Aswathy, S. H.; Narendrakumar, U.; Manjubala, I. Commercial hydrogels for biomedical applications. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03719. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. C.; Kwon, I. K.; Park, K. Hydrogels for delivery of bioactive agents: A historical perspective. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 17-20. [CrossRef]

- Chirani Naziha; Yahia L’Hocine ; Gritsch Lukas; Motta Federico Leonardo; Chirani Soumia; Silvia, F. History and applications of hydrogels. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 4, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. Recent advances in hydrogels. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 1987-1989. [CrossRef]

- Badeau, B. A.; DeForest, C. A. Programming stimuli-responsive behavior into biomaterials. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 21, 241-265. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Tang, P. Recent advances on magnetic sensitive hydrogels in tissue engineering. Front. Chem. 2020, 8,00124. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Sun, J. Magnetic hydrogels with ordered structure for biomedical applications. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1040492. [CrossRef]

- Frachini, E. C. G.; Petri, D. F. S. Magneto-responsive hydrogels: Preparation, characterization, biotechnological and environmental applications. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2019, 30, 2010–2028. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Xie, W.; Miao, Y.; Wang, D.; Guo, Z.; Ghosal, A.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Feng, S.-S.; Zhao, L.; et al. Magnetic hydrogel with optimally adaptive functions for breast cancer recurrence prevention. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900203. [CrossRef]

- Manjua, A. C.; Alves, V. D.; Crespo, J. G.; Portugal, C. A. M. Magnetic responsive PVA hydrogels for remote modulation of protein sorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21239-21249. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, M.; Tan, H.; Ren, B.; Yuan, G.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Xiong, D.; Xing, X.; Niu, X.; et al. Magnetic and self-healing chitosan-alginate hydrogel encapsulated gelatin microspheres via covalent cross-linking for drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 101, 619-629. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Ren, E.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, G.; Mao, C.; Zheng, L. Cartilage-targeting and dual MMP-13/pH responsive theranostic nanoprobes for osteoarthritis imaging and precision therapy. Biomaterials 2019, 225, 119520. [CrossRef]

- Munaweera, I.; Aliev, A.; Balkus, K. J., Jr. Electrospun cellulose acetate-garnet nanocomposite magnetic fibers for bioseparations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 244-251. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Song, L.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zang, F.; An, Y.; Lyu, H.; Ma, M.; Chen, J.; et al. Injectable thermosensitive magnetic nanoemulsion hydrogel for multimodal-imaging-guided accurate thermoablative cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 16175-16182. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bae, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, P.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Hydrogels and hydrogel-derived materials for energy and water sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7642-7707. [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Jose, V. K.; Lee, J.-M. Hydrogels for medical and environmental applications. Small Methods 2020, 4, 1900735. [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Lu, J.; Li, C.; He, Z.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, L. Injectable magnetic hydrogel filler for synergistic bone tumor hyperthermia chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 1569-1578. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tian, C.; Zhang, H.; Xie, H. Biodegradable magnetic hydrogel robot with multimodal locomotion for targeted cargo delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 28922-28932. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; Xue, L.; Dong, G.; Su, W.; Cui, M. j.; Wang, Z. g.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X. Ultrasoft and biocompatible magnetic-hydrogel-based strain sensors for wireless passive biomechanical monitoring. ACS nano 2022, 16 (12), 21555-21564.

- Ishihara, K.; Narita, Y.; Teramura, Y.; Fukazawa, K. Preparation of magnetic hydrogel microparticles with cationic surfaces and their cell-assembling performance. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 5107-5117. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Pal, D.; Chattopadhyay, S. Target-specific superparamagnetic hydrogel with excellent pH sensitivity and reversibility: A promising platform for biomedical applications. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 21768-21780. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yin, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, T. Shape morphing of hydrogels in alternating magnetic field. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21194-21200. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Huang, H. Review on magnetic natural polymer constructed hydrogels as vehicles for drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 2574-2594. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Cheng, Y. Magnetic-responsive hydrogels: From strategic design to biomedical applications. J. Control. Release 2021, 335, 541-556. [CrossRef]

- Phalake, S. S.; Somvanshi, S. B.; Tofail, S. A. M.; Thorat, N. D.; Khot, V. M. Functionalized manganese iron oxide nanoparticles: a dual potential magneto-chemotherapeutic cargo in a 3D breast cancer model. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 15686-15699. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, J.; Barati, A.; Ai, J.; Nooshabadi, V. T.; Mirzaei, Z. Employing hydrogels in tissue engineering approaches to boost conventional cancer-based research and therapies. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10646-10669. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Q.; Song, S.-C. Thermosensitive/superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded nanocapsule hydrogels for multiple cancer hyperthermia. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Rose, J. C.; Cámara-Torres, M.; Rahimi, K.; Köhler, J.; Möller, M.; De Laporte, L. Nerve cells decide to orient inside an injectable hydrogel with minimal structural guidance. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 3782-3791. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, M.; Taylor, A.; Fuentes-Caparrós, A. M.; Sharkey, J.; Daniels, L. M.; Mandal, P.; Park, B. K.; Murray, P.; Rosseinsky, M. J.; Adams, D. J. SPIONs for cell labelling and tracking using MRI: magnetite or maghemite? Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 101-106. [CrossRef]

- Haas, W.; Zrinyi, M.; Kilian, H. G.; Heise, B. Structural analysis of anisometric colloidal iron(III)-hydroxide particles and particle-aggregates incorporated in poly(vinyl-acetate) networks. Colloid and Polymer Science 1993, 271, 1024-1034. [CrossRef]

- Fiejdasz, S.; Gilarska, A.; Horak, W.; Radziszewska, A.; Strączek, T.; Szuwarzyński, M.; Nowakowska, M.; Kapusta, C. Structurally stable hybrid magnetic materials based on natural polymers – preparation and characterization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 3149-3160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, D. In situ mineralization of magnetite nanoparticles in chitosan hydrogel. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 1041. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Lu, T.; Lu, T. J.; Xu, F. Magnetic hydrogels and their potential biomedical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 660-672. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 426. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Huang, J.; Fang, R.; Liu, M. Imparting functionality to the hydrogel by magnetic-field-induced nano-assembly and macro-response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 5177-5194. [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Azcón, J.; Ahadian, S.; Estili, M.; Liang, X.; Ostrovidov, S.; Kaji, H.; Shiku, H.; Ramalingam, M.; Nakajima, K.; Sakka, Y.; et al. Dielectrophoretically aligned carbon nanotubes to control electrical and mechanical properties of hydrogels to fabricate contractile muscle myofibers. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4028-4034. [CrossRef]

- Ahadian, S.; Ramón-Azcón, J.; Estili, M.; Liang, X.; Ostrovidov, S.; Shiku, H.; Ramalingam, M.; Nakajima, K.; Sakka, Y.; Bae, H.; et al. Hybrid hydrogels containing vertically aligned carbon nanotubes with anisotropic electrical conductivity for muscle myofiber fabrication. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 4271. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Sun, J.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Hu, K.; Wang, P.; Ma, M.; Gu, N. Rotating magnetic field-controlled fabrication of magnetic hydrogel with spatially disk-like microstructures. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 61, 1112-1122. [CrossRef]

- Antman-Passig, M.; Shefi, O. Remote magnetic orientation of 3D collagen hydrogels for directed neuronal regeneration. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2567-2573. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Jin, D.; Zheng, K.; Liu, X.; Chai, M.; Wang, Z.; Chi, A.; et al. Magnetic soft microrobots for erectile dysfunction therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121, e2407809121. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-Y.; Chan, T.-Y.; Wang, K.-S.; Tsou, H.-M. Influence of magnetic nanoparticle arrangement in ferrogels for tunable biomolecule diffusion. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 90098-90102. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Das, P.; Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A. R.; Tang, X. S.; Margel, S. Superparamagnetic Amine-Functionalized Maghemite Nanoparticles as a Thixotropy Promoter for Hydrogels and Magnetic Field-Driven Diffusion-Controlled Drug Release. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2024, 7 (5), 5272-5286. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Margel, S. 3D printed magnetic polymer composite hydrogels for hyperthermia and magnetic field driven structural manipulation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 131, 101574. [CrossRef]

- Tumarkin, E.; Kumacheva, E. Microfluidic generation of microgels from synthetic and natural polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2161-2168. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. G.; Unnithan, A. R.; Moon, M. J.; Surendran, S. P.; Batgerel, T.; Park, C. H.; Kim, C. S.; Jeong, Y. Y. Electromagnetic manipulation enabled calcium alginate Janus microsphere for targeted delivery of mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 110, 465-471. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zou, M.; Liu, Y.; Bian, F.; Zhao, Y. Peanut-inspired anisotropic microparticles from microfluidics. Compos. Commun. 2018, 10, 129-135. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Bian, F.; Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Anisotropic microparticles from microfluidics. Chem 2021, 7, 93-136. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Bioinspired helical micromotors as dynamic cell microcarriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 16097-16103. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Valenzuela, C.; Xue, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, X. Magnetic structural color hydrogels for patterned photonic crystals and dynamic camouflage. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3618-3626. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Ramalingam, M.; Bae, H.; Orive, G.; Fujie, T.; Shi, X.; Kaji, H. Bioprinting and biomaterials for dental alveolar tissue regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2023, 11, 991821. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Murugan, R.; Hojae, B.; Gorka, O.; Toshinori, F.; Xuetao, S.; and Kaji, H. Latest developments in engineered skeletal muscle tissues for drug discovery and development. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2023, 18, 47-63. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Salehi, S.; Costantini, M.; Suthiwanich, K.; Ebrahimi, M.; Sadeghian, R. B.; Fujie, T.; Shi, X.; Cannata, S.; Gargioli, C.; et al. 3D Bioprinting in skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Small 2019, 15, 1805530. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Tang, D.; Xu, H.; Zhao, P.; Fu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y. 3D Printing of functional magnetic materials: From design to applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2102777. [CrossRef]

- Simińska-Stanny, J.; Nizioł, M.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Brożyna, M.; Junka, A.; Shavandi, A.; Podstawczyk, D. 4D printing of patterned multimaterial magnetic hydrogel actuators. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 49, 102506. [CrossRef]

- Grenier, J.; Duval, H.; Barou, F.; Lv, P.; David, B.; Letourneur, D. Mechanisms of pore formation in hydrogel scaffolds textured by freeze-drying. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Haugh, M. G.; Murphy, C. M.; O’Brien, F. J. Novel Freeze-drying methods to produce a range of collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds with tailored mean pore sizes. Tissue Eng. Part C: Methods 2009, 16, 887-894. [CrossRef]

- Rouhollahi, A.; Ilegbusi, O.; Florczyk, S.; Xu, K.; Foroosh, H. Effect of mold geometry on pore size in freeze-cast chitosan-alginate scaffolds for tissue engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 1090-1102. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gong, X.; Fan, Y.; Xia, H. Physically crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels with magnetic field controlled modulus. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 6205-6212. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, X.; Tian, L.; Xie, J.; Xiang, Y.; Liang, X.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, L. Preparation and properties of chitosan/dialdehyde sodium alginate/dopamine magnetic drug-delivery hydrogels. Colloids Surf. A: Phys. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132739. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Ebrahimi, M.; Bae, H.; Nguyen, H. K.; Salehi, S.; Kim, S. B.; Kumatani, A.; Matsue, T.; Shi, X.; Nakajima, K.; et al. Gelatin–polyaniline composite nanofibers enhanced excitation–contraction coupling system maturation in myotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 42444-42458. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Shi, X.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Kim, S. B.; Fujie, T.; Ramalingam, M.; Chen, M.; Nakajima, K.; Al-Hazmi, F.; et al. Myotube formation on gelatin nanofibers – Multi-walled carbon nanotubes hybrid scaffolds. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 6268-6277. [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.; Park, S. M.; Hong, H.; Kwon, J.; Oh, S.-R.; Kim, J.; Kim, D. S. Hydrogel-assisted electrospinning for fabrication of a 3D complex tailored nanofiber macrostructure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 51212-51224. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298-5415. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, S.; Wang, R.; Che, Y.; Han, C.; Feng, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, W. Electrospun nanofiber/hydrogel composite materials and their tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 162, 157-178. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J. P. M.; Monteiro, C. F.; Deus, I. A.; Completo, A.; Stratakis, E.; Mano, J. F.; Marques, P. A. A. P. Magnetoresponsive anisotropic fiber-integrating hydrogels for neural tissue regeneration. Small Struct. 2024, 5, 2400213. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, G.; Wei, T.; Zhong, S.; Lu, L.; Yan, C.; Wang, Y.; Fang, M.; Yang, M.; et al. Electrospinning aligned SF/magnetic nanoparticles-blend nanofiber scaffolds for inducing skeletal myoblast alignment and differentiation. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 7710-7718. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Z.; Ni, R.; Feng, P.; Hu, Z.; Song, L.; Shen, X.; Gu, C.; Li, J.; et al. Engineered muscle from micro-channeled PEG scaffold with magnetic Fe3O4 fixation towards accelerating esophageal muscle repair. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 23, 100853. [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.; Choi, Y. H.; An, Y.-H.; Tahk, D.; Cho, S.; Yoon, J. W.; Jeon, N. L.; Park, T. H.; Kim, J.; Hwang, N. S. Magnetic nanoparticle-embedded hydrogel sheet with a groove pattern for wound healing application. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3909-3921. [CrossRef]

- Sahiner, N.; Singh, M.; De Kee, D.; John, V. T.; McPherson, G. L. Rheological characterization of a charged cationic hydrogel network across the gelation boundary. Polymer 2006, 47, 1124-1131. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ostrovidov, S.; Shu, Y.; Liang, X.; Nakajima, K.; Wu, H.; Khademhosseini, A. Microfluidic generation of polydopamine gradients on hydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir 2014, 30, 832-838. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Burgess, D. J. Chapter 5 - Impact of biomaterials’ physical properties on cellular and molecular responses. In Handbook of Biomaterials Biocompatibility, Mozafari, M. Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, Sawston UK, 2020; pp 69-84.

- Kim, D.-N.; Park, J.; Koh, W.-G. Control of cell adhesion on poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel surfaces using photochemical modification and micropatterning techniques. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2009, 15, 124-128. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yao, Y.; Yim, E. K. F. The effects of surface topography modification on hydrogel properties. APL Bioeng. 2021, 5, 031509. [CrossRef]

- Mantha, S.; Pillai, S.; Khayambashi, P.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, O.; Pham, H. M.; Tran, S. D. Smart hydrogels in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Materials, 2019, 12, 3323. [CrossRef]

- Niinomi, M. Mechanical biocompatibilities of titanium alloys for biomedical applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2008, 1, 30-42. [CrossRef]

- Crippa, F.; Moore, T. L.; Mortato, M.; Geers, C.; Haeni, L.; Hirt, A. M.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Petri-Fink, A. Dynamic and biocompatible thermo-responsive magnetic hydrogels that respond to an alternating magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 427, 212-219. [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Xu, M.; Qin, M.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, D.; Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, W. Physicochemical properties and biocompatibility of the bi-layer polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel for osteochondral tissue engineering. Mater. Des. 2021, 204, 109652. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zhou, F.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ni, C.; Pan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Yang, L.; Lin, Q.; et al. A strongly adhesive hemostatic hydrogel for the repair of arterial and heart bleeds. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2060. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Lan, G.; Hu, E.; Lu, F.; Qian, P.; Liu, J.; Dai, F.; Xie, R. Targeted delivery of hemostats to complex bleeding wounds with magnetic guidance for instant hemostasis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130916. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Gao, Q.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Gao, F.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, L. Injectable and self-healing thermosensitive magnetic hydrogel for asynchronous control release of doxorubicin and docetaxel to treat triple-negative breast cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 33660-33673. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Behzadi, S.; Laurent, S.; Forrest, M. L.; Stroeve, P.; Mahmoudi, M. Toxicity of nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2323-2343.

- Liu, G.; Gao, J.; Ai, H.; Chen, X. Applications and potential toxicity of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Small 2013, 9, 1533-1545. [CrossRef]

- Axpe, E.; Chan, D.; Offeddu, G. S.; Chang, Y.; Merida, D.; Hernandez, H. L.; Appel, E. A. A multiscale model for solute diffusion in hydrogels. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 6889-6897. [CrossRef]

- Nicolella, P.; Koziol, M. F.; Löser, L.; Saalwächter, K.; Ahmadi, M.; Seiffert, S. Defect-controlled softness, diffusive permeability, and mesh-topology of metallo-supramolecular hydrogels. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 1071-1081. [CrossRef]

- Vinchhi, P.; Rawal, S. U.; Patel, M. M. Chapter 19 - Biodegradable hydrogels. In Drug Delivery Devices and Therapeutic Systems, Chappel, E. Ed.; Academic Press, Cambridge MA, 2021; pp 395-419.

- Zong, H.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Yan, S.; Zhang, K.; Shou, Y.; Yin, J. Biodegradable high-strength hydrogels with injectable performance based on poly(l-glutamic acid) and gellan gum. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4702-4713. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-González, M.; Willner, I. Stimuli-responsive biomolecule-based hydrogels and their applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15342-15377. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Tian, H. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels: Fabrication and biomedical applications. VIEW 2022, 3, 20200112. [CrossRef]

- Gang, F.; Jiang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X. Multi-functional magnetic hydrogel: Design strategies and applications. Nano Sel. 2021, 2, 2291-2307. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, L.; Tang, Z.; Li, Q.; Qin, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, B.; Zheng, J. General strategy to fabricate strong and tough low-molecular-weight gelator-based supramolecular hydrogels with double network structure. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1743-1754. [CrossRef]

- Bin Imran, A.; Esaki, K.; Gotoh, H.; Seki, T.; Ito, K.; Sakai, Y.; Takeoka, Y. Extremely stretchable thermosensitive hydrogels by introducing slide-ring polyrotaxane cross-linkers and ionic groups into the polymer network. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5124. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.; Song, F.; Qian, D.; He, Y.-D.; Nie, W.-C.; Wang, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-Z. Strong and tough fully physically crosslinked double network hydrogels with tunable mechanics and high self-healing performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 349, 588-594. [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K. Synthesis and properties of soft nanocomposite materials with novel organic/inorganic network structures. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 223-241. [CrossRef]

- Ispas, G.-M.; Porav, S.; Gligor, D.; Turcu, R.; Crăciunescu, I. Magnetic hydrogel composites based on cross-linked poly (acrylic acid) used as a recyclable adsorbent system for nitrates. Water Environ. J. 2020, 34, 916-928. [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinia, G. R.; Soleymani, M.; Etemadi, H.; Sabzi, M.; Atlasi, Z. Model protein BSA adsorption onto novel magnetic chitosan/PVA/laponite RD hydrogel nanocomposite beads. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 719-729. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; He, W.; Shen, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Su, P.; Yang, Y. Self-assembly of a magnetic DNA hydrogel as a new biomaterial for enzyme encapsulation with enhanced activity and stability. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2449-2452. [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Sun, J.; Guo, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Q.; Ma, M.; Gu, N. A novel magnetic hydrogel with aligned magnetic colloidal assemblies showing controllable enhancement of magnetothermal effect in the presence of alternating magnetic field. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 2507-2514. [CrossRef]

- Ram, N. R.; Prakash, M.; Naresh, U.; Kumar, N. S.; Sarmash, T. S.; Subbarao, T.; Kumar, R. J.; Kumar, G. R.; Naidu, K. C. B. Review on magnetocaloric effect and materials. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 1971-1979. [CrossRef]

- Ashikbayeva, Z.; Tosi, D.; Balmassov, D.; Schena, E.; Saccomandi, P.; Inglezakis, V. Application of nanoparticles and nanomaterials in thermal ablation therapy of cancer. Nanomaterials, 2019, 9, 1195. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jia, Z.; Liang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Rong, Z.; Xiong, J.; Wang, D. Pulse electromagnetic fields enhance the repair of rabbit articular cartilage defects with magnetic nano-hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 541-550. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, X.; Li, F.; Qiu, J.; Umair, M. M.; Ren, W.; Ju, B.; Zhang, S.; Tang, B. Magnetochromic photonic hydrogel for an alternating magnetic field-responsive color display. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1701093. [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, Z. Tailoring the swelling-shrinkable behavior of hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303326. [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H.; Kushiro, K.; Takai, M.; Chung, U.-i.; Sakai, T. Non-osmotic hydrogels: A rational strategy for safely degradable hydrogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9282-9286. [CrossRef]

- Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Gasik, M. Smart hydrogels for advanced drug delivery systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2022, 23, 3665. [CrossRef]

- Rashidzadeh, B.; Shokri, E.; Mahdavinia, G. R.; Moradi, R.; Mohamadi-Aghdam, S.; Abdi, S. Preparation and characterization of antibacterial magnetic-/pH-sensitive alginate/Ag/Fe3O4 hydrogel beads for controlled drug release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 134-141. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Go, G.; Ko, S. Y.; Park, J.-O.; Park, S. Magnetic actuated pH-responsive hydrogel-based soft micro-robot for targeted drug delivery. Smart Mater. Struct. 2016, 25, 027001. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-i.; Lee, H.; Kwon, S.-h.; Choi, H.; Park, S. Magnetic nano-particles retrievable biodegradable hydrogel microrobot. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem. 2019, 289, 65-77. [CrossRef]

- Shibaev, A. V.; Smirnova, M. E.; Kessel, D. E.; Bedin, S. A.; Razumovskaya, I. V.; Philippova, O. E. Remotely self-healable, shapeable and pH-sensitive dual cross-linked polysaccharide hydrogels with fast response to magnetic field. Nanomaterials, 2021, 11, 1271. [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Liu, X.-L.; Ma, H.; Xie, W.; Huang, S.; Wen, H.; Jing, G.; Zhao, L.; Liang, X.-J.; Fan, H. M. AMF responsive DOX-loaded magnetic microspheres: transmembrane drug release mechanism and multimodality postsurgical treatment of breast cancer. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 2289-2303. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Annabi, N.; Seidi, A.; Ramalingam, M.; Dehghani, F.; Kaji, H.; Khademhosseini, A. controlled release of drugs from gradient hydrogels for high-throughput analysis of cell–drug interactions. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 1302-1309. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Gong, C. Injectable hydrogel-based drug delivery systems for enhancing the efficacy of radiation therapy: A review of recent advances. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109225. [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Bennici, S.; Brendle, J.; Dutournie, P.; Limousy, L.; Pluchon, S. Systems for stimuli-controlled release: Materials and applications. J. Control. Release 2019, 294, 355-371. [CrossRef]

- Jalili, N. A.; Muscarello, M.; Gaharwar, A. K. Nanoengineered thermoresponsive magnetic hydrogels for biomedical applications. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 297-305. [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zheng, J.; Guo, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dong, B.; Lin, C.; Huang, B.; Lu, B. Smart cellulose-derived magnetic hydrogel with rapid swelling and deswelling properties for remotely controlled drug release. Cellulose 2019, 26, 6861-6877. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Boudoukhani, M.; Belmonte-Reche, E.; Genicio, N.; Sillankorva, S.; Gallo, J.; Rodríguez-Abreu, C.; Moulai-Mostefa, N.; Bañobre-López, M. Xanthan-Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite hydrogels for non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging and magnetically assisted drug delivery. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 7712-7729. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jian, W.; Huixiang, J.; and Fang, Z. Magnetic nano-Fe3O4 particles targeted gathering and bio-effects on nude mice loading human hepatoma Bel-7402 cell lines model under external magnetic field exposure in vivo. Electromag. Biol. Med. 2015, 34, 309-316. [CrossRef]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Soleimani, K.; Derakhshankhah, H.; Haghshenas, B.; Rezaei, A.; Massoumi, B.; Farnudiyan-Habibi, A.; Samadian, H.; Jaymand, M. Multi-stimuli-responsive magnetic hydrogel based on Tragacanth gum as a de novo nanosystem for targeted chemo/hyperthermia treatment of cancer. J. Mater. Res. 2021, 36, 858-869. [CrossRef]

- Paulino, A. T.; Guilherme, M. R.; de Almeida, E. A. M. S.; Pereira, A. G. B.; Muniz, E. C.; Tambourgi, E. B. One-pot synthesis of a chitosan-based hydrogel as a potential device for magnetic biomaterial. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 2636-2642. [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Sharma, P. K.; Malviya, R. Hyperthermia: Role and risk factor for cancer treatment. Achievements Life Sci. 2016, 10, 161-167. [CrossRef]

- Moros, M.; Idiago-López, J.; Asín, L.; Moreno-Antolín, E.; Beola, L.; Grazú, V.; Fratila, R. M.; Gutiérrez, L.; de la Fuente, J. M. Triggering antitumoural drug release and gene expression by magnetic hyperthermia. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 138, 326-343. [CrossRef]

- Sumitha, N. S.; Krishna, N. G.; Sailaja, G. S. Chitosan-TEMPO-oxidized nanocellulose magnetic responsive patches with hyperthermia potential for smart melanoma therapy. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 9170-9179. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhai, H.; Ding, J.; Yu, L. Autophagy inhibition mediated via an injectable and NO-releasing hydrogel for amplifying the antitumor efficacy of mild magnetic hyperthermia. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 336-353. [CrossRef]

- Barra, A.; Wychowaniec, J. K.; Winning, D.; Cruz, M. M.; Ferreira, L. P.; Rodriguez, B. J.; Oliveira, H.; Ruiz-Hitzky, E.; Nunes, C.; Brougham, D. F.; et al. Magnetic chitosan bionanocomposite films as a versatile platform for biomedical hyperthermia. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2024, 13, 2303861. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Mishkovsky, M.; Junk, M. J. N.; Münnemann, K.; Comment, A. Producing radical-free hyperpolarized perfusion agents for in vivo magnetic resonance using spin-labeled thermoresponsive hydrogel. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2016, 37, 1074-1078. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Hu, K.; Zhang, M.; Sheng, J.; Xu, X.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Si, G.; Mao, Y.; et al. Extracellular magnetic labeling of biomimetic hydrogel-induced human mesenchymal stem cell spheroids with ferumoxytol for MRI tracking. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 418-428. [CrossRef]

- Mistral, J.; Ve Koon, K. T.; Fernando Cotica, L.; Sanguino Dias, G.; Aparecido Santos, I.; Alcouffe, P.; Milhau, N.; Pin, D.; Chapet, O.; Serghei, A.; et al. Chitosan-coated superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic hyperthermia, and drug delivery. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 7097-7110. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; He, J.; Guo, B. Functional hydrogels as wound dressing to enhance wound healing. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 12687-12722. [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, E. A.; Kenawy, E.-R. S.; Chen, X. A review on polymeric hydrogel membranes for wound dressing applications: PVA-based hydrogel dressings. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 8, 217-233. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E. M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105-121. [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Yin, J.; Yan, S. Progress in hydrogels for skin wound repair. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2100475. [CrossRef]

- Bal-Öztürk, A.; Özkahraman, B.; Özbaş, Z.; Yaşayan, G.; Tamahkar, E.; Alarçin, E. Advancements and future directions in the antibacterial wound dressings–A review. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 703-716.

- Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Deng, D.; Gu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Q. Multiple stimuli-responsive MXene-based hydrogel as intelligent drug delivery carriers for deep chronic wound healing. Small 2022, 18, 2104368.

- Pires, F.; Silva, J. C.; Ferreira, F. C.; Portugal, C. A. Heparinized acellular hydrogels for magnetically induced wound healing applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 9908-9924. [CrossRef]

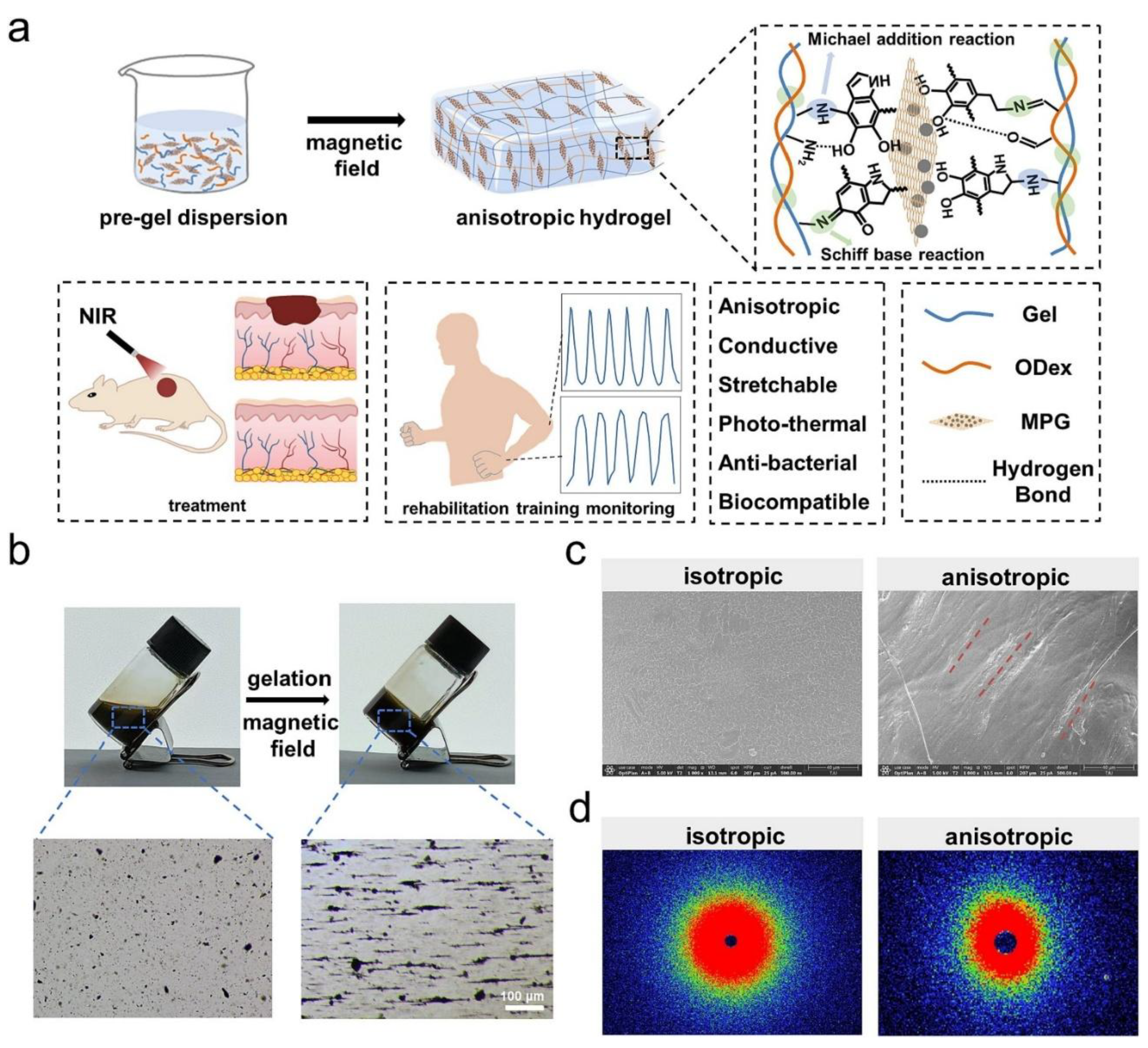

- Li, X.; Tan, Z.; Guo, B.; Yu, C.; Yao, M.; Liang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yao, F.; Zhang, H.; et al. Magnet-oriented hydrogels with mechanical–electrical anisotropy and photothermal antibacterial properties for wound repair and monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142387. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jin, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, P.; Lai, J.; Li, S.; Jin, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. Thermoresponsive, magnetic, adhesive and conductive nanocomposite hydrogels for wireless and non-contact flexible sensors. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 636, 128113. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovidov, S.; Ramalingam, M.; Bae, H.; Orive, G.; Fujie, T.; Hori, T.; Nashimoto, Y.; Shi, X.; Kaji, H. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based sensors for the detection of skeletal- and cardiac-muscle-related analytes. Sensors, 2023, 23, 5625. [CrossRef]

- Banan Sadeghian, R.; Han, J.; Ostrovidov, S.; Salehi, S.; Bahraminejad, B.; Ahadian, S.; Chen, M.; Khademhosseini, A. Macroporous mesh of nanoporous gold in electrochemical monitoring of superoxide release from skeletal muscle cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 88, 41-47. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, R. B.; Ostrovidov, S.; Han, J.; Salehi, S.; Bahraminejad, B.; Bae, H.; Chen, M.; Khademhosseini, A. Online monitoring of superoxide anions released from skeletal muscle cells using an electrochemical biosensor based on thick-film nanoporous gold. ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 921-928. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Mao, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, T.; Ren, J.; et al. Functional hydrogels and their application in drug delivery, biosensors, and tissue engineering. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2019, 2019, 3160732. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S.; Lee, J. S.; Kim, M. I. Poly-γ-glutamic acid/chitosan hydrogel nanoparticles entrapping glucose oxidase and magnetic nanoparticles for glucose biosensing. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 5333-5337. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Dashtian, K.; Golzani, M.; Ejraei, Z.; Zare-Dorabei, R. Remote magnetically stimulated xanthan-biochar-Fe3O4-molecularly imprinted biopolymer hydrogel toward electrochemical enantioselection of l-tryptophan. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1316, 342837.

- Doblado, L. R.; Martínez-Ramos, C.; Pradas, M. M. Biomaterials for neural tissue engineering. Front. Nanotechnol. 2021, 3, 643507. [CrossRef]

- Leipzig, N. D.; Shoichet, M. S. The effect of substrate stiffness on adult neural stem cell behavior. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6867-6878. [CrossRef]

- Vijayavenkataraman, S. Nerve guide conduits for peripheral nerve injury repair: A review on design, materials and fabrication methods. Acta Biomater. 2020, 106, 54-69. [CrossRef]

- Tay, A.; Sohrabi, A.; Poole, K.; Seidlits, S.; Di Carlo, D. A 3D magnetic hyaluronic acid hydrogel for magnetomechanical neuromodulation of primary dorsal root ganglion neurons. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800927.

- Koffler, J.; Zhu, W.; Qu, X.; Platoshyn, O.; Dulin, J. N.; Brock, J.; Graham, L.; Lu, P.; Sakamoto, J.; Marsala, M. Biomimetic 3D-printed scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 263-269.

- Lacko, C. S.; Singh, I.; Wall, M. A.; Garcia, A. R.; Porvasnik, S. L.; Rinaldi, C.; Schmidt, C. E. Magnetic particle templating of hydrogels: Engineering naturally derived hydrogel scaffolds with 3D aligned microarchitecture for nerve repair. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17, 016057. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ye, D.; An, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, M.; Li, P. Nerve tissue regeneration based on magnetic and conductive bifunctional hydrogel scaffold. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109120. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Guan, W.; Sun, S.; Zheng, T.; Wu, L.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, G. Anisotropic topological scaffolds synergizing non-invasive wireless magnetic stimulation for accelerating long-distance peripheral nerve regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 153809. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.; Tayebi, L.; Akbarzadeh, M.; Lohrasbi, P.; Savardashtaki, A. Magnetic hydrogel applications in articular cartilage tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2024, 112, 260-275. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, C.; Yan, S.; Liu, Q.; Hou, M.; Xu, Y.; Guo, R. Non-invasive monitoring of in vivo hydrogel degradation and cartilage regeneration by multiparametric MR imaging. Theranostics 2018, 8, 1146-1158. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhu, P.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Guo, H.; Tang, S.; Guo, R. Functionalization of novel theranostic hydrogels with kartogenin-grafted USPIO nanoparticles to enhance cartilage regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 34744-34754. [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, H. M.; Clark, A. T.; Gullbrand, S. E.; Carey, J. L.; Cheng, X. M.; Mauck, R. L. Magneto-driven gradients of diamagnetic objects for engineering complex tissues. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2005030. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, C.; Kim, H. S.; Moon, C.; Lee, K. Y. 3D Printing of dynamic tissue scaffold by combining self-healing hydrogel and self-healing ferrogel. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112108. [CrossRef]

- Alford, A. I.; Kozloff, K. M.; Hankenson, K. D. Extracellular matrix networks in bone remodeling. Int. j. biochem. cell biol. 2015, 65, 20-31. [CrossRef]

- Katsamenis, O. L.; Chong, H. M.; Andriotis, O. G.; Thurner, P. J. Load-bearing in cortical bone microstructure: Selective stiffening and heterogeneous strain distribution at the lamellar level. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 17, 152-165. [CrossRef]

- 157 Arjmand, M.; Ardeshirylajimi, A.; Maghsoudi, H.; Azadian, E. Osteogenic differentiation potential of mesenchymal stem cells cultured on nanofibrous scaffold improved in the presence of pulsed electromagnetic field. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1061-1070. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Cai, H.; Yang, X.; Xue, Y.; Wan, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Magnetic scaffold constructing by micro-injection for bone tissue engineering under static magnetic field. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3554-3565. [CrossRef]

- Babakhani, A.; Peighambardoust, S. J.; Olad, A. Fabrication of magnetic nanocomposite scaffolds based on polyvinyl alcohol-chitosan containing hydroxyapatite and clay modified with graphene oxide: Evaluation of their properties for bone tissue engineering applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 150, 106263. [CrossRef]

- Bolonduro, O. A.; Duffy, B. M.; Rao, A. A.; Black, L. D.; Timko, B. P. From biomimicry to bioelectronics: Smart materials for cardiac tissue engineering. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 1253-1267. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. R.; Zihlmann, C.; Akbari, M.; Assawes, P.; Cheung, L.; Zhang, K.; Manoharan, V.; Zhang, Y. S.; Yüksekkaya, M.; Wan, K.-T., et al. Reduced graphene oxide-GelMA hybrid hydrogels as scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering. Small 2016, 12, 3677-3689. [CrossRef]

- 162 Qazi, T. H.; Rai, R.; Dippold, D.; Roether, J. E.; Schubert, D. W.; Rosellini, E.; Barbani, N.; Boccaccini, A. R. Development and characterization of novel electrically conductive PANI–PGS composites for cardiac tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2434-2445. [CrossRef]

- Kai, D.; Prabhakaran, M. P.; Jin, G.; Ramakrishna, S. Polypyrrole-contained electrospun conductive nanofibrous membranes for cardiac tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2011, 99A, 376-385. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Shin, S. R.; van Kempen, T.; Li, Y.-C.; Ponraj, V.; Nasajpour, A.; Mandla, S.; Hu, N.; Liu, X.; Leijten, J. et al. Gold nanocomposite bioink for printing 3D cardiac constructs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1605352. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A. M.; Eng, G.; Caridade, S. G.; Mano, J. F.; Reis, R. L.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Electrically conductive chitosan/carbon scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 635-643. [CrossRef]

- Ahadian, S.; Yamada, S.; Ramón-Azcón, J.; Estili, M.; Liang, X.; Nakajima, K.; Shiku, H.; Khademhosseini, A.; Matsue, T. Hybrid hydrogel-aligned carbon nanotube scaffolds to enhance cardiac differentiation of embryoid bodies. Acta Biomater. 2016, 31, 134-143. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. R.; Jung, S. M.; Zalabany, M.; Kim, K.; Zorlutuna, P.; Kim, S. b.; Nikkhah, M.; Khabiry, M.; Azize, M.; Kong, J. et al. Carbon-nanotube-embedded hydrogel sheets for engineering cardiac constructs and bioactuators. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2369-2380. [CrossRef]

- Bonfrate, V.; Manno, D.; Serra, A.; Salvatore, L.; Sannino, A.; Buccolieri, A.; Serra, T.; Giancane, G. Enhanced electrical conductivity of collagen films through long-range aligned iron oxide nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 501, 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Vannozzi, L.; Yasa, I. C.; Ceylan, H.; Menciassi, A.; Ricotti, L.; Sitti, M. Self-folded hydrogel tubes for implantable muscular tissue scaffolds. Macromol. Biosci. 2018, 18, 1700377. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, K.; Chang, Q.; Darabi, M. A.; Lin, B.; Zhong, W.; Xing, M. Highly flexible and resilient elastin hybrid cryogels with shape memory, injectability, conductivity, and magnetic responsive properties. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7758-7767. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kim, B.; Shin, J.-Y.; Ryu, S.; Noh, M.; Woo, J.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, N.; Hyeon, T. et al. Iron oxide nanoparticle-mediated development of cellular gap junction crosstalk to improve mesenchymal stem cells’ therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2805-2819. [CrossRef]

- Kankala, R. K.; Zhu, K.; Sun, X.-N.; Liu, C.-G.; Wang, S.-B.; Chen, A.-Z. Cardiac tissue engineering on the nanoscale. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 800-818. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, H.; Heirani-Tabasi, A.; Hajiabbas, M.; Salimi Bani, M.; Nazari, M.; Pirhajati Mahabadi, V.; Rad, I.; Kehtari, M.; Ahmadi Tafti, S. H.; Soleimani, M. Incorporation of SPION-casein core-shells into silk-fibroin nanofibers for cardiac tissue engineering. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 2981-2993. [CrossRef]

- Cicha, I.; Alexiou, C. Cardiovascular applications of magnetic particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 518, 167428. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yu, G.; Cheng, J.; Song, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, L.; Wei, X.; Yang, M. Design of an injectable magnetic hydrogel based on the tumor microenvironment for multimodal synergistic cancer therapy. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 868-885. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, P.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Fan, Y. One-step preparation of Fe3O4/nanochitin magnetic hydrogels with remolding ability by ammonia vapor diffusion gelation for osteosarcoma therapy. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 1314-1325. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Etxeberria, A. E.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, P.; Song, P.; Min, L.; Luo, Y.; Nand, A. V.; et al. Dual-cross-linked magnetic hydrogel with programmed release of parathyroid hormone promotes bone healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 35815-35831. [CrossRef]

- Abenojar, E. C.; Wickramasinghe, S.; Ju, M.; Uppaluri, S.; Klika, A.; George, J.; Barsoum, W.; Frangiamore, S. J.; Higuera-Rueda, C. A.; Samia, A. C. S. Magnetic glycol chitin-based hydrogel nanocomposite for combined thermal and d-amino-acid-assisted biofilm disruption. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1246-1256. [CrossRef]

- Mañas-Torres, M. C.; Gila-Vilchez, C.; Vazquez-Perez, F. J.; Kuzhir, P.; Momier, D.; Scimeca, J.-C.; Borderie, A.; Goracci, M.; Burel-Vandenbos, F.; Blanco-Elices, C.; et al. Injectable magnetic-responsive short-peptide supramolecular hydrogels: Ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 49692-49704. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Lock, J.; Sallee, A.; Liu, H. Magnetic nanocomposite hydrogel for potential cartilage tissue engineering: Synthesis, characterization, and cytocompatibility with bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20987-20998. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Meng, Z.; Yang, K.; He, Z.; Hou, Z.; Yang, J.; Lu, J.; Cao, Z.; Yang, S.; Chai, Y.; et al. External magnetic field non-invasively stimulates spinal cord regeneration in rat via a magnetic-responsive aligned fibrin hydrogel. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 035022. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Bagher, Z.; Najmoddin, N.; Simorgh, S.; Pezeshki-Modaress, M. Alginate-magnetic short nanofibers 3D composite hydrogel enhances the encapsulated human olfactory mucosa stem cells bioactivity for potential nerve regeneration application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 796-806. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, P.; Li, K.; Xu, J.; Liu, M.; Fan, Y. The effect of magnetic poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) microsphere-gelatin hydrogel on the growth of pre-osteoblasts under static magnetic field. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2020, 16, 1658-1666. [CrossRef]

- Silva, E. D.; Babo, P. S.; Costa-Almeida, R.; Domingues, R. M. A.; Mendes, B. B.; Paz, E.; Freitas, P.; Rodrigues, M. T.; Granja, P. L.; Gomes, M. E. Multifunctional magnetic-responsive hydrogels to engineer tendon-to-bone interface. Nanomedicine: NBM 2018, 14, 2375-2385. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Xia, Z.; Cai, K. Osteogenic differentiation of the MSCs on silk fibroin hydrogel loaded Fe3O4@PAA NPs in static magnetic field environment. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2022, 220, 112947. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.-P.; Liang, H.-F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Su, D.-H.; Lu, S.-Y.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Wu, T.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Precipitation-based silk fibroin fast gelling, highly adhesive, and magnetic nanocomposite hydrogel for repair of irregular bone defects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2302442. [CrossRef]

- Santhamoorthy, M.; Thirupathi, K.; Kumar, S. S. D.; Pandiaraj, S.; Rahaman, M.; Phan, T. T. V.; Kim, S.-C. k-Carrageenan based magnetic@polyelectrolyte complex composite hydrogel for pH and temperature-responsive curcumin delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125467. [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Mohammadi, A.; Aghamirza Moghim Aliabadi, H.; Kashtiaray, A.; Bani, M. S.; Karimi, A. H.; Maleki, A.; Mahdavi, M. A novel ternary magnetic nanobiocomposite based on tragacanth-silk fibroin hydrogel for hyperthermia and biological properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8166. [CrossRef]

- Carrelo, H.; Escoval, A. R.; Vieira, T.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Silva, J. C.; Romero, A.; Soares, P. I. P.; Borges, J. P. Injectable thermoresponsive microparticle/hydrogel system with superparamagnetic nanoparticles for drug release and magnetic hyperthermia applications. Gels 2023, 9, 982. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. Design of a pH-sensitive magnetic composite hydrogel based on salecan graft copolymer and Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles as drug carrier. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1811-1820. [CrossRef]

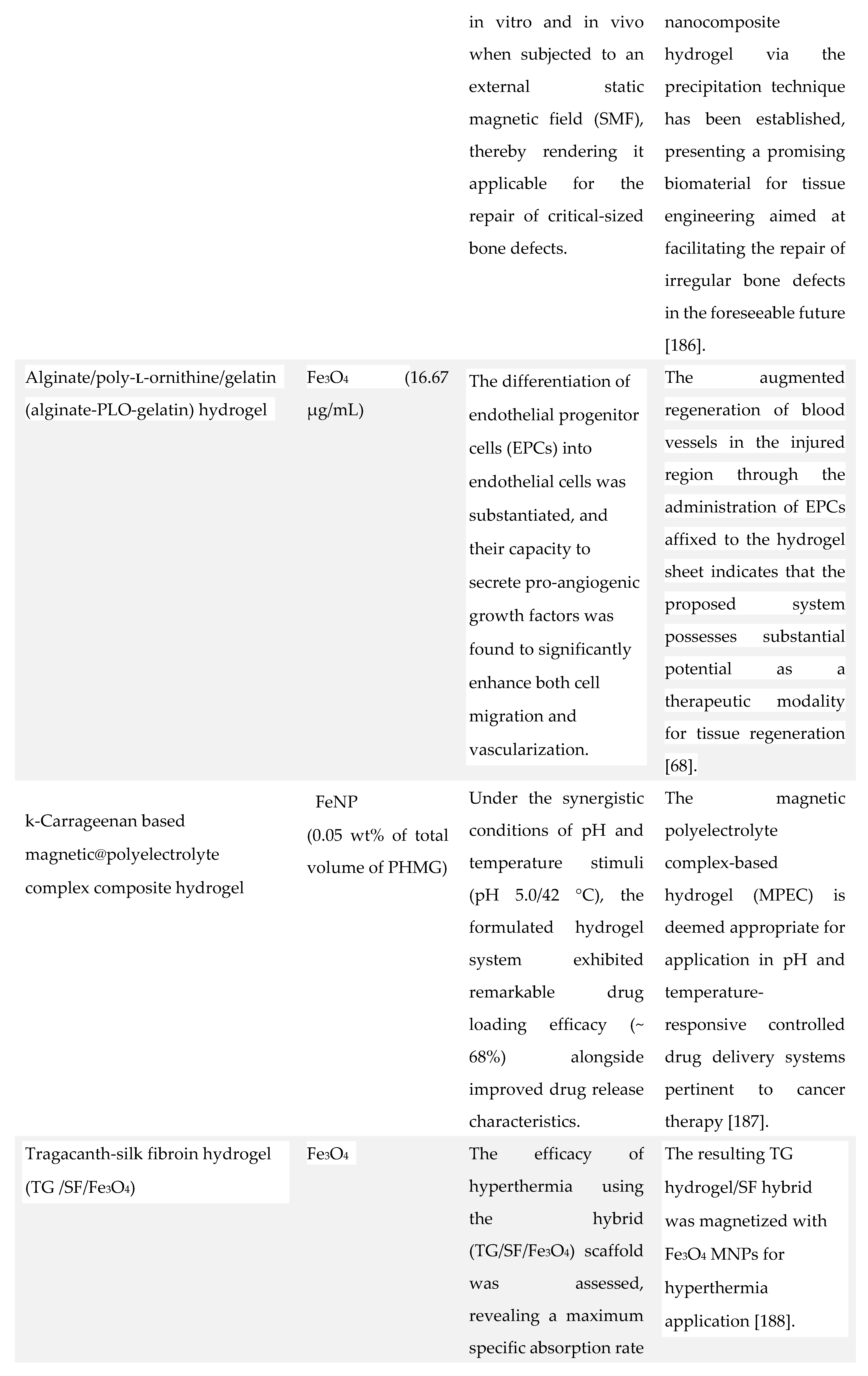

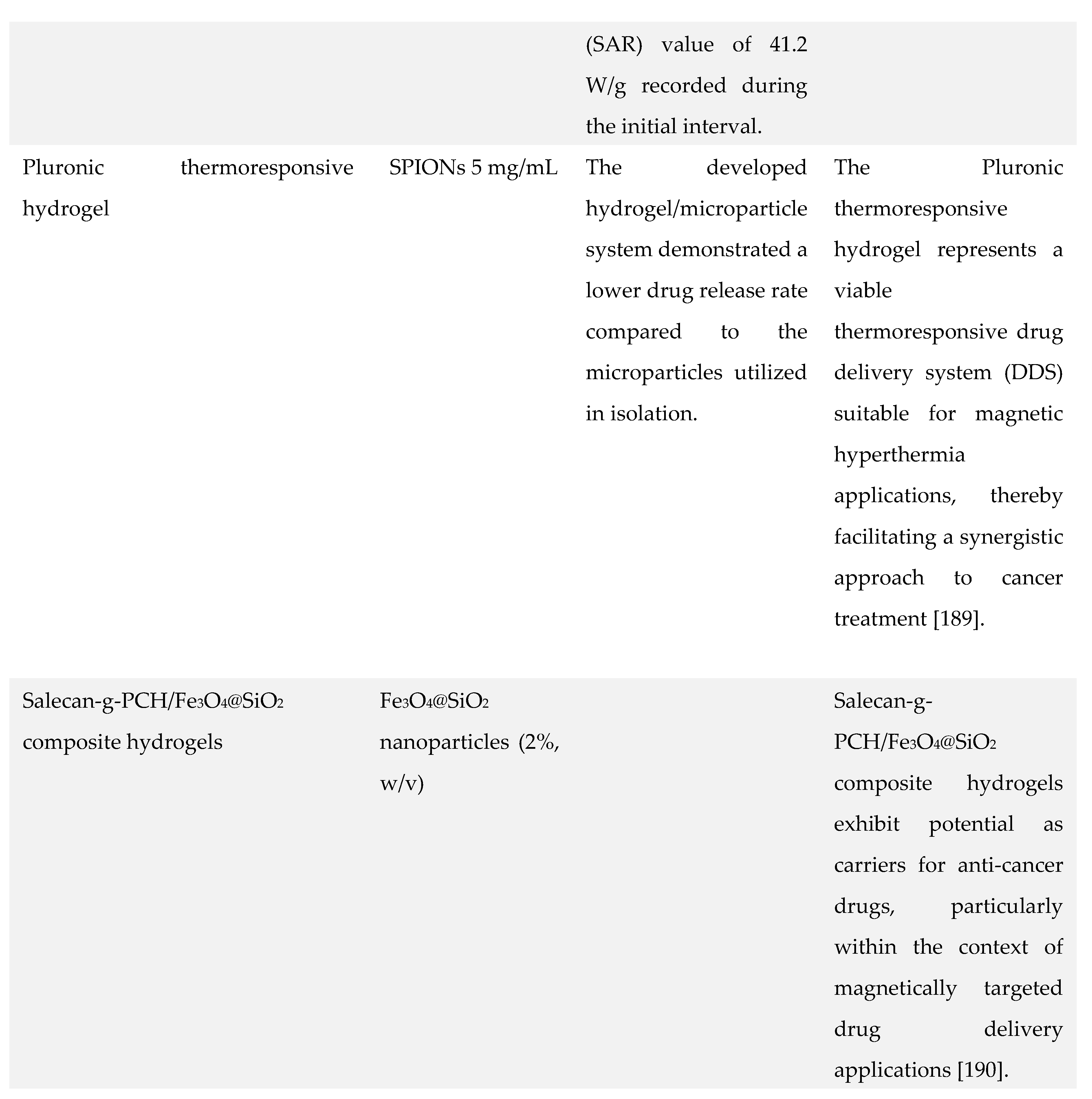

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).