1. Introduction

This study builds a drone security system for a

truck yard that “knows” its legal flight area and automatically stays inside

it. A lightweight AI model (YOLO) detects people and vehicles in real time,

while safety logic steers the drone away from roads, construction zones, and

other hazards. We also plan routes that can be exported and audited, and we

show how multiple drones can share the job without conflict. The software and

routes are shared openly. After checking on-site latency and false alarms, the

system is ready for a small pilot at the Denton facility.

Modern industrial complexes are increasingly

challenged by expanding operational areas, fluctuating environmental

conditions, and surveillance blind spots that traditional fixed cameras cannot

fully address. UAVs equipped with AI-driven video analytics close these gaps by

enabling mobile and adaptive surveillance. This paper presents the design and

evaluation of a UAV surveillance system specifically tailored for The Larson

Group (TLG) Denton facility, focusing on real-time detection, incident-aware

routing, and geofence-constrained operations.

UAVs significantly improve situational awareness

and accelerate response times, surpassing the limitations of ground-based

systems. Deploying computer vision algorithms directly on drones or at nearby

edge nodes minimizes delays and bandwidth demands, facilitating rapid

detection, tracking, and alerting even in low-connectivity environments (Xu et

al., 2023; Singh et al., 2023).

The evolution of UAV technology has extended far

beyond basic RGB camera payloads. Integrating thermal and infrared (IR) sensors

with other advanced modules, such as LiDAR, enables comprehensive monitoring

across varying light levels and adverse weather conditions. This multisensor

approach enhances object recognition in challenging scenarios like nighttime

patrols or densely obstructed areas. Recent studies demonstrate that

lightweight neural networks combined with IR sensing can provide reliable real-time

detection of small and partially obscured targets, making them ideal for

industrial security operations focused on identifying intruders or unusual

vehicle activities (Su et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025).

At the systems level, coordinated multi-UAV

operations have become increasingly sophisticated. Contemporary frameworks

integrate collaborative flight planning, collision avoidance, energy-efficient

routing, and real-time adaptation to no-fly zones or construction areas. These

innovations are especially relevant to TLG, where multiple drones must cover

expansive and evolving perimeters. For example, one UAV can dynamically respond

to an active security alert while others continue routine patrols, ensuring uninterrupted

surveillance while optimizing power usage and docking schedules (Meng et al.,

2025).

In addition, geofencing technologies now provide

advanced boundary enforcement. “Hard” geofencing anticipates UAV motion

dynamics, guiding drones to adjust course proactively rather than reacting at

the boundary itself. This improves both operational safety and regulatory

compliance, particularly in areas bordering public roads or sensitive

neighboring properties. When implemented at both the autopilot and

mission-planning layers, these geofences provide predictable, auditable flight

paths suitable for high-security environments (Thomas et al., 2024).

As UAV deployments scale, cybersecurity and privacy

concerns must be integral to design and implementation. Research identifies

potential vulnerabilities, including GPS spoofing, communication jamming, and

adversarial manipulation of AI models. Privacy risks such as unintentional

surveillance of neighboring properties or unauthorized data retention are

equally critical. Best practices now emphasize encrypted telemetry and video

streams, policy-constrained data collection zones, and privacy-preserving analytics

techniques like on-device redaction (Mekdad et al., 2023; Hadi et al., 2023).

These requirements align with the ongoing evolution of Beyond Visual Line of

Sight (BVLOS) regulations, where emerging U.S. policies emphasize pilot

certifications, safety management systems, and auditable compliance processes

(Federal Aviation Administration [FAA], 2025).

In conclusion, recent scholarship supports the

design decisions behind TLG’s integrated UAV surveillance project. By combining

edge-based analytics, multisensor payloads, coordinated drone fleets,

anticipatory geofencing, and strong privacy protections, this initiative lays

the groundwork for a proactive, scalable, and regulation-ready security

ecosystem capable of meeting the complex needs of modern industrial operations.

Figure 1.

Project workflow for UAV operations and ground integration at TLG—Denton, linking patrol scheduling, live telemetry, incident response, and auditing.

Figure 1.

Project workflow for UAV operations and ground integration at TLG—Denton, linking patrol scheduling, live telemetry, incident response, and auditing.

The study location (TLG parking facility) operates

under defined hours of operation, which also dictate the scheduling of UAV

patrols to ensure continuous coverage during peak activity periods and

vulnerable off-hours. Current ground security consists of on-site personnel and

traditional surveillance measures, such as inward-facing cameras and routine

patrols.

However, these inward-facing cameras have

significant limitations, including restricted visibility of external perimeters

and blind spots, making them susceptible to unauthorized access or theft. UAVs

provide dynamic, real-time monitoring, extending coverage beyond the fixed

range of cameras, addressing security gaps, identifying suspicious activity in

hard-to-reach areas, and enabling rapid responses to potential breaches.

This integrated approach improves overall facility

security while optimizing human resource allocation(Thomas et al., 2024).

Figure 2.

TLG parking lot layout with truck staging, monitoring zones, and dispatch lanes.

Figure 2.

TLG parking lot layout with truck staging, monitoring zones, and dispatch lanes.

Figure 3.

Live UAV surveillance map with real-time positions, telemetry, and QR-linked SOPs.

Figure 3.

Live UAV surveillance map with real-time positions, telemetry, and QR-linked SOPs.

The interface displays altitude, speed, signal

strength, and battery levels while providing quick access to emergency SOPs,

pre-flight checklists, and incident report forms through integrated QR codes.The growing complexity of security threats necessitates enhanced

situational awareness through advanced aerial surveillance. Traditional

ground-based systems alone cannot provide comprehensive coverage, especially in

large, dynamically changing environments such as expanding parking lots.

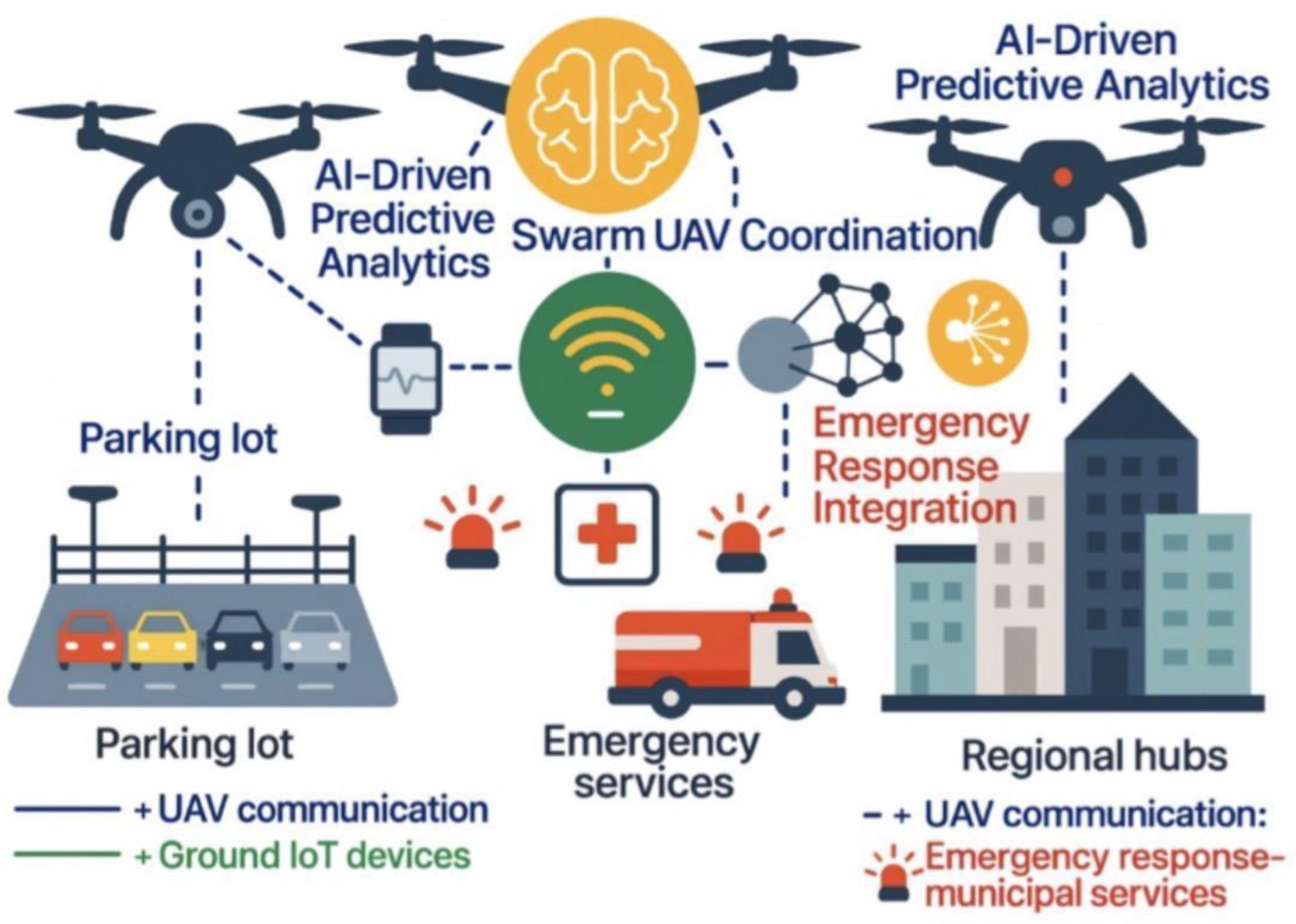

This project will integrate secure communications,

intrusion detection, and unauthorized vehicle tracking to create a robust,

adaptive defense system(Ashraf et al., 2023). A collaborative UAV network will

share live camera feeds and telemetry data for continuous, secure, and reliable

monitoring, enhancing both safety and situational awareness.

Figure 4.

Coordinated multi-UAV night surveillance with coverage zones and alert hotspot.

Figure 4.

Coordinated multi-UAV night surveillance with coverage zones and alert hotspot.

Surveillance zones are highlighted, including a red

alert area near the customer parking section. The on-screen telemetry display

shows key flight data such as altitude, speed, and battery level, demonstrating

an advanced, cooperative security system for vehicle and perimeter monitoring.

Traditional security systems often lack

comprehensive coverage and rapid response capabilities, leading to blind spots

and delayed threat detection. With ongoing expansion and construction

activities, these vulnerabilities are amplified.A UAV-based surveillance system

will provide flexible, real-time aerial monitoring, improving situational

awareness, reducing response times, and strengthening security management

(Aissaoui et al., 2023).

The following objectives are outlined for the

current project.

Deploy UAVs for continuous and on-demand surveillance.

Implement geofencing to enforce secure perimeters.

Integrate UAV feeds with ground systems for real-time decision-making.

Establish protocols for incident response and evidence collection.

Early geofencing for fleets established

geo-boundary enforcement and logistics use cases, which later informed

low-altitude UAS operations and safety envelopes (Reclus & Drouard, 2009).

Formal safety for “assured containment” in aviation anticipating and

constraining vehicle motion was articulated in NASA’s case studies and has

influenced digital geofences that act before boundary violation rather than at

it (Hayhurst et al., 2015). Surveyed techniques in geofenced motion planning

and constrained navigation for UAVs include rule-based and optimization-based

approaches, with recent work emphasizing predictive constraint handling and

map-aware path planners (Hosseinzadeh, 2021; Thomas et al., 2024). Practical,

deployable geofencing for low-altitude UAS highlights platform-independent

enforcement in operational airspace (Stevens et al., 2015). For yard-scale

routing, grid-/graph-based planners (e.g., A*) and coverage methods

(boustrophedon) remain standard, with geo-fence and separation constraints

analyzed in industrial settings (Liu et al., 2016).

The contributions of this work include the following:

First incident-aware CBF+MPC geofence controller designed and evaluated using VisDrone-driven yard scenarios, integrating predictive safety modeling with real-world operational constraints.

Development of exportable geofenced route artifacts (A*, sector patrol, and lawn-mower coverage paths) with reproducible datasets and code pipelines for deployment and auditing.

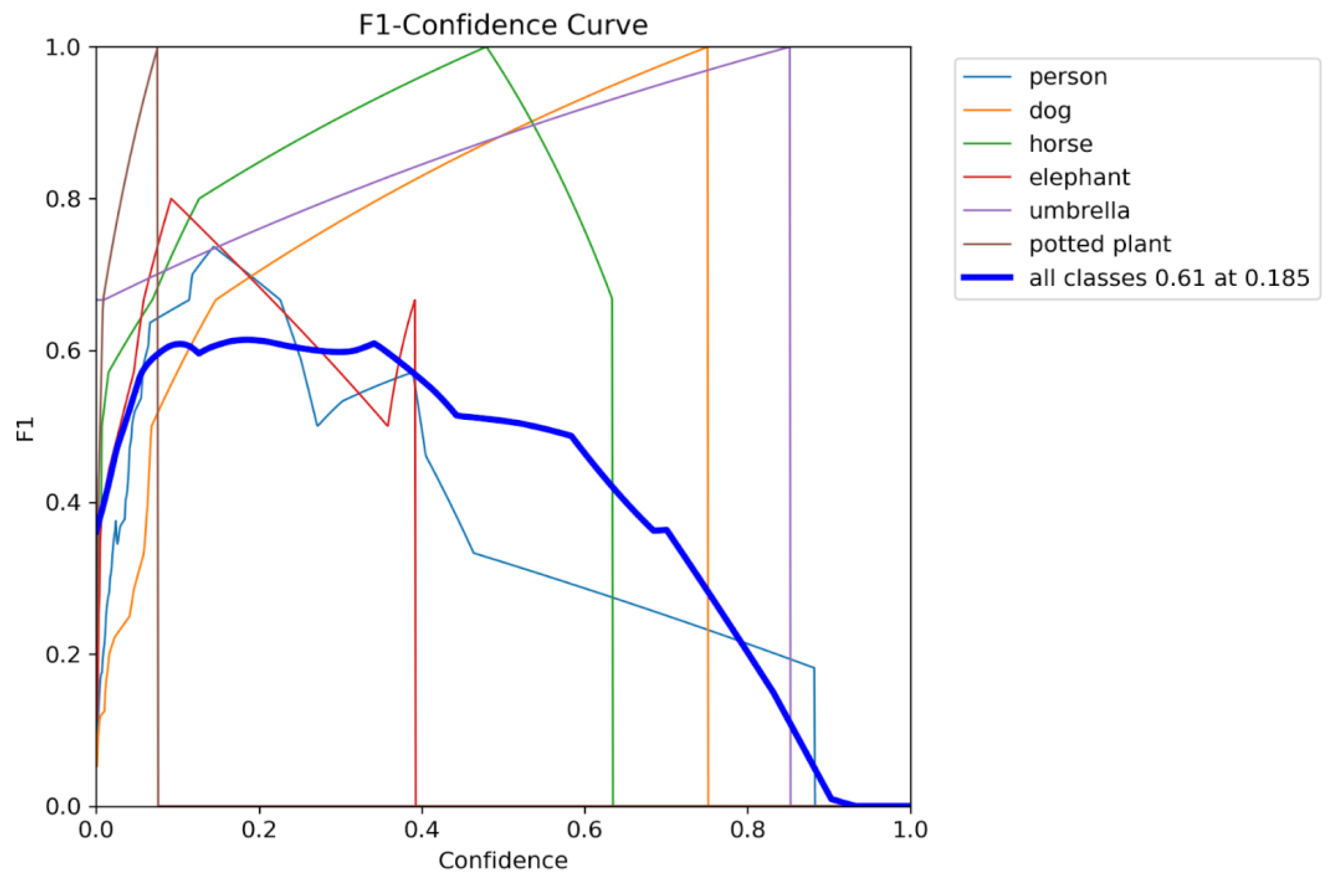

Proposal of a deployment-threshold selection method (τ ≈ 0.185) to balance detection precision and recall under dense yard scenes.

Integration of multi-layered UAV and ground-based surveillance systems, demonstrating reduced blind spots and faster response times in a dynamic industrial facility.

Introduction of privacy-aware, regulation-compliant UAV workflows aligned with BVLOS and geofencing safety standards.

The project organization and structure outline are: Project Aim (TL;DR)

Design, train, and validate an incident-aware, geofenced UAV surveillance system for TLG–Denton that works in real time and integrates with ground security and facility operations.

Column A: Context, Scope and Questions

A1. Why this project?

Expanding facility footprint introduces blind spots and dynamic risks (frontage road, construction zones, moving fleets).

Need scalable air-ground security fusion that reduces response times, increases detection coverage, and respects BVLOS and privacy constraints.

A2. Scope & Boundaries

In scope: VisDrone-driven models, YOLOv11-nano fine-tuning, geofence design (A*, sector patrol, mower coverage), five CV tasks (det, video det, SOT, MOT, counting), Denton site.

Out of scope (now): Multi-site roll-out, full swarm autonomy, L4 autonomy beyond BVLOS pilots.

A3. Research Questions (guide the paper)

What detection/tracking performance (mAP@0.5, F1@τ, IDF1/HOTA) is sufficient for pilot deployment?

How do geofence constraints and incident-aware routing affect safety and coverage?

What operating threshold (τ ≈ 0.185) balances precision/recall under dense scenes?

How can compliance, privacy, and BVLOS be embedded in the workflow without degrading utility?

Column B — Methods Pipeline & Tasks

B1. Materials & Methods (Section 7)

Site modeling: Patrol sectors, no-flight buffers, frontage-road hazard overlays.

Datasets: VisDrone2019 (urban UAV imagery/video; 10 relevant classes).Custom split 70/15/15 with reproducible RNG seed (no leakage).

Models: YOLOv11n fine-tuned for 100 epochs @ 640²; Ultralytics runtime.

Tools: Python 3.12, NumPy, scikit-learn, Matplotlib, Label Studio; optional AirSim; NVIDIA RTX 4090, CUDA 12.2.

UAV/GCS: Multirotors + thermal option; GPS/IMU; live telemetry to GCS with geofence & NFZ alerts.

B2. Experiments (Section 8)

Task 1 — Detection (Images): mAP@0.5, PR curves, confusion matrices.

Task 2 — Detection (Video): NMS tuning for dense scenes; latency checks.

Task 3 — SOT: Success/precision plots; OPE AUC.

Task 4 — MOT: MOTA/MOTP, ID switches; ByteTrack association.

Task 5 — Counting: Density maps; MAE/RMSE.

B3. Geofence & Routing (Section 12)

Formal set-based model: R (lot), C (GO zone), N=R\C (NO-GO).

A* inside C with barrier margins; sector patrol for multi-UAV deconfliction; boustrophedon (lawn-mower)coverage with δ-safety.

Incident-aware MPC + control-barrier functions for time-varying hazards.

Column C — Deliverables, Risks & Roadmap

C1. Artifacts & Evidence (Sections 8–10, 13)

Metrics packs: results.csv, PR/F1 curves, confusion matrices, operating-point sweeps.

Qualitative gallery: 10+ image frames, 3+ video frames (dense & twilight scenes).

Routes: astar_path.csv, sector_waypoints.csv, lawn_mower_route.csv, tlg_routes.geojson.

Ops diagrams: dashboards, return-to-charge, three-layer security fusion.

C2. Risk Matrix → Mitigations (Section 11)

Critical: False +/−, environmental sensitivity → ensemble models, HIL review, IR/thermal, wind envelopes.

High: BVLOS/regulatory, privacy → geofencing, signage, data minimization/anonymization, policy SOPs.

Medium: Cost/maintenance → phased rollout, leasing, predictive maintenance.

C3. Milestones (checkpoints)

C4. Contributions (Section 12— “Contribution”)

Integrated air–ground security loop with incident-aware routing.

Deployable operating point (τ ≈ 0.185) balancing precision/recall for yard scenes.

Reproducible pipeline (data splits, code, routes) and compliance-aware workflow.

C5. Future Directions (Section 14)

Multi-lot scaling, autonomous swarms, smarter patrol scheduling, low-light/domain-adaptation, smart-city integration.

This project addresses the expanding security and safety surface at TLG–Denton by unifying UAV-based perception, geofence-constrained routing, and operations/compliance workflows into a reproducible pipeline. Building on VisDrone-trained YOLO11n models and a formal safety set-up (A*sector patrol, coverage patterns, and incident-aware MPC), we define performance targets (mAP@0.5, F1@τ, IDF1/HOTA, MAE) and deliver deployment artifacts (routes, dashboards, SOP-aligned flows). The next section (Materials & Methods) details the site modeling, dataset preparation, training procedure, tools, and UAV/GCS stack that enable rigorous evaluation and a pilot-ready prototype.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we examine the study location and its critical components, including UAV flight paths, designated patrol routes, surveillance coverage areas, the parking lot, the frontage road, and nearby construction zones. The proposed system integrates YOLOv11-nano, a lightweight, real-time object detection model, fine-tuned on the VisDrone2019dataset using a reproducible 70/15/15 split for training, validation, and testing. Geofencing is implemented using control-barrier functions (CBF) combined with model predictive control (MPC) to ensure safe, compliant navigation within dynamic operational boundaries.

The UAV hardware consists of GPS-enabled multirotor drones equipped with high-resolution cameras and optional thermal imaging sensors for enhanced detection during low-light or night-time operations. Exportable route files in CSVand GeoJSON formats support seamless operational handoff, auditing, and regulatory compliance.

Reproducibility Checklist:

Dataset: VisDrone2019; custom 70/15/15 split with fixed RNG seed for consistency.

Model: YOLOv11-nano; trained for 100 epochs at an input size of 640×640 using the Ultralytics runtime.

Metrics: mAP@0.5 / mAP@[.5:.95], PR/F1 curves; IDF1/HOTA (planned), MAE/RMSE for counting tasks.

Operating Threshold: τ = 0.185 (optimal F1 ≈ 0.61) for deployment in dense yard scenarios.

Hardware: NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, CUDA 12.2; batch size = 16 (training), 1 (evaluation).

Routing Algorithms: A*, sector patrol, and lawn-mower coverage patterns with CSV/GeoJSON exports.

Safety Mechanisms: Signed-distance safety margins, CBF-filtered MPC, and incident-aware replanning.

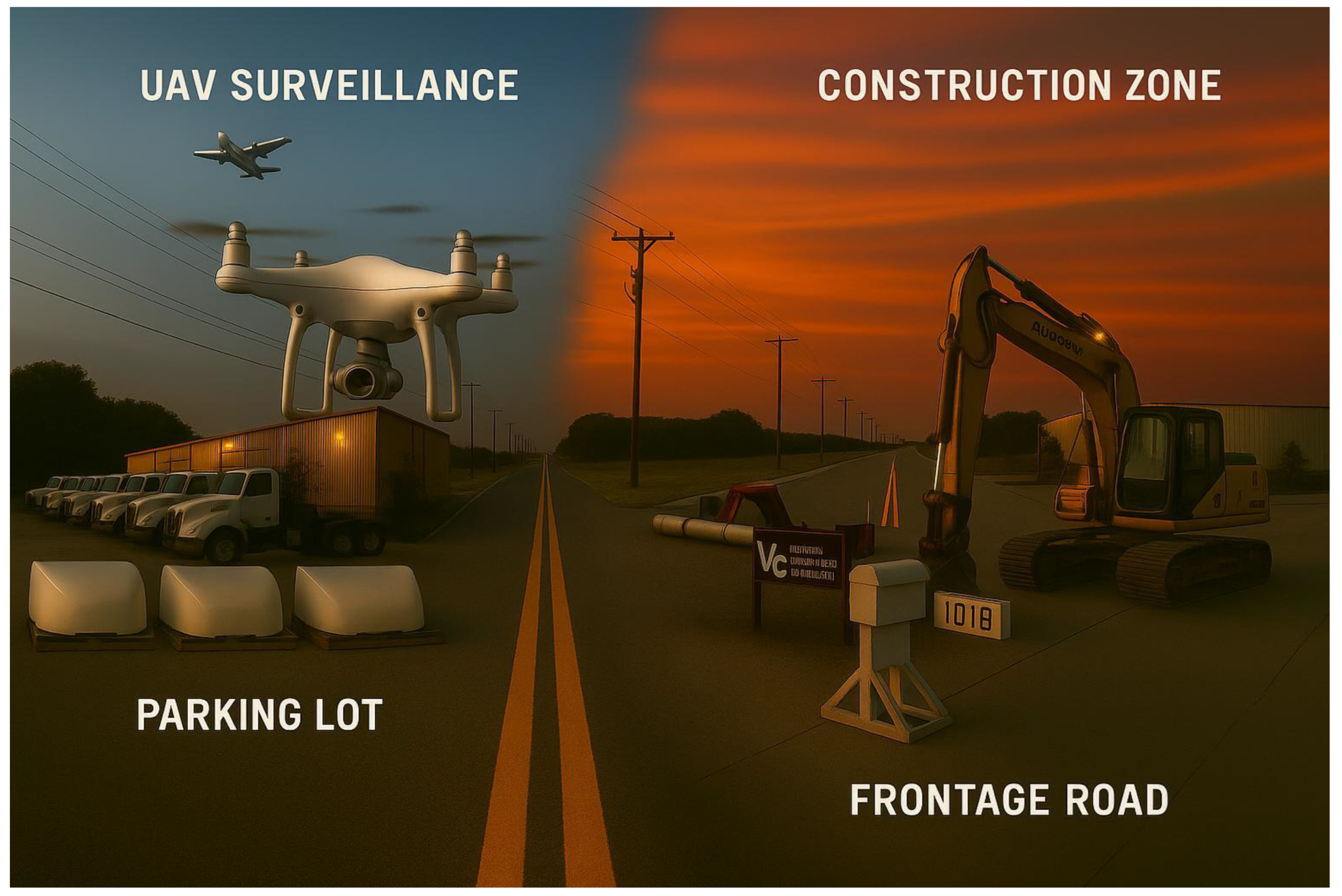

Figure 5 illustrates the current TLG facility expansion, highlighting areas that require comprehensive UAV surveillance to address emerging security and operational challenges.

The image depicts key surveillance zones such as UAV coverage, parking lot monitoring, the frontage road, and construction activity.

It provides a visual context for the methodology, especially when describing UAV flight paths, surveillance cameras, and security integration.

This is crucial when discussing how data is gathered, e.g., drones collecting real-time footage and vehicles being tracked.

2.1. Datasets Source, Preprocessing, and Partitioning

The VisDrone2019 dataset (Tianjin University) was selected as the primary dataset due to its suitability for UAV-based surveillance research. VisDrone2019 provides UAV images and videos from urban scenes with ten annotated classes relevant to yard surveillance (e.g., pedestrians, cars, vans, buses) (Du et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). These categories directly align with the monitoring requirements of The Larson Group (TLG) parking lot, where various vehicle types and human activities must be detected and tracked for security purposes.

The original Ultralytics YOLO public dataset configuration came with fixed splits for training, validation, and testing. However, for this study, a custom 70; 15; 15 partition was enforced to ensure proper model generalization and consistent performance evaluation. This required merging the original training and validation sets, reshuffling the combined dataset, and redistributing images into three subsets:

Training Set (70%): Used to optimize model weights.

Validation Set (15%): Used for hyperparameter tuning and overfitting detection.

Testing Set (15%): Used strictly for performance evaluation.

This splitting process ensured that no data leakage occurred between the sets, maintaining the integrity of evaluation metrics.

Dataset Classes:

The dataset includes 10 classes: pedestrian, people, bicycle, car, van, truck, tricycle, awning-tricycle, bus, and motorbike. These directly correspond to common activities within a parking lot environment.The dataset is directly relevant to this project.

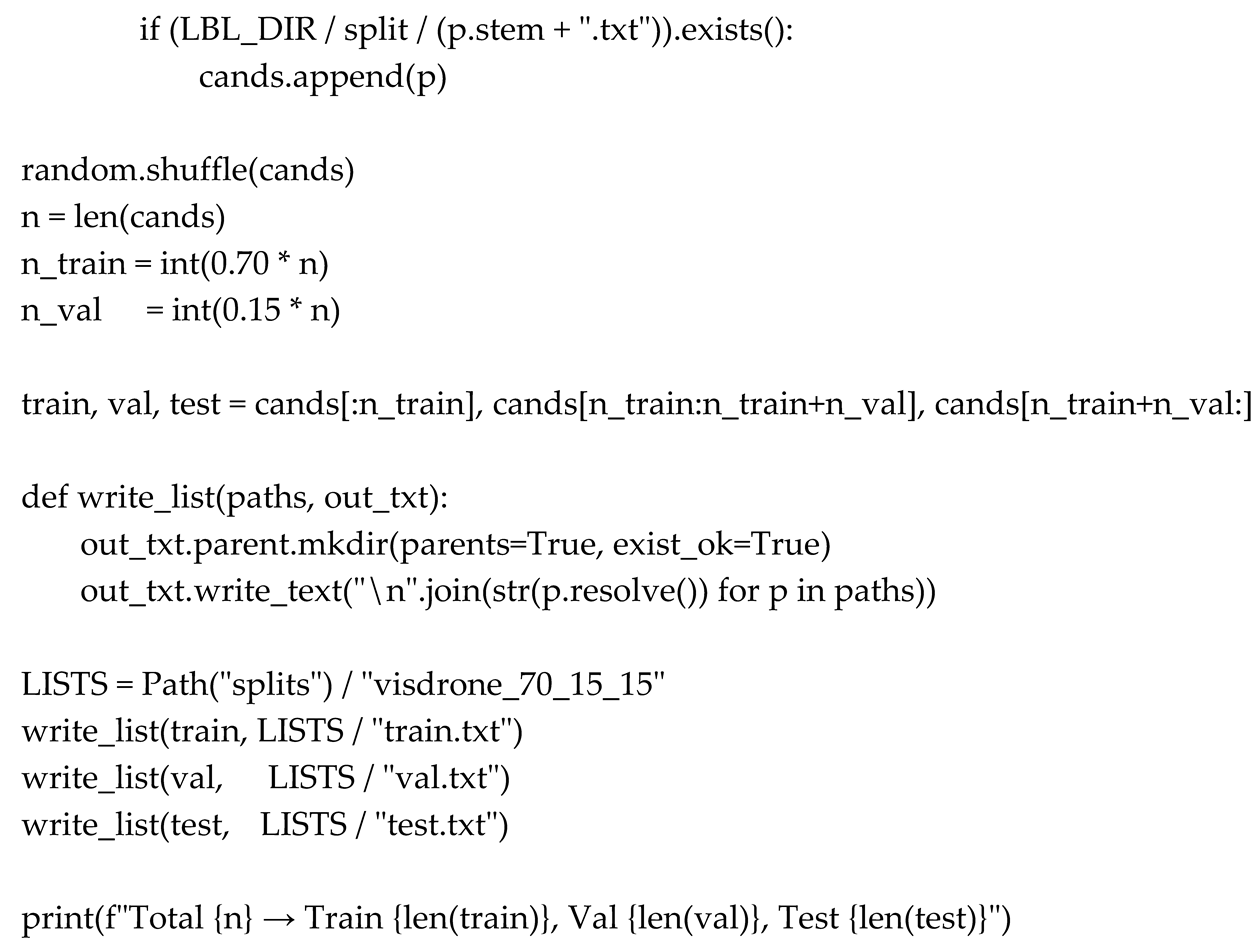

2.2. Dataset Partitioning Code

The custom split was created programmatically using Python. Below is a snippet of the one-time script used to perform the dataset merge and shuffle. It outputs three .txt files referencing the respective training, validation, and testing image paths.

This procedure ensures reproducibility by fixing the random seed (RNG_SEED), allowing the exact same splits to be regenerated in future experiments.

2.3. Model Training and Task Design

The YOLOv11 Nano (YOLO11n) model was selected due to its balance between speed and accuracy, making it suitable for real-time UAV surveillance applications. A pretrained YOLO backbone was fine-tuned on the VisDrone dataset for 100 epochs with an image input size of 640×640.

Training Code:

2.4. Tasks Performed

Five core computer vision tasks were addressed:

Object Detection in Images(ODI): Detect vehicles, people, and other objects from aerial snapshots.

Object Detection in Videos(ODV): Process live UAV video streams for real-time threat detection.

Single-Object Tracking(SOT): Follow specific high-priority targets such as suspicious vehicles or individuals.

Multi-Object Tracking (MOT): Track multiple moving entities simultaneously across frames using ByteTrack.

Crowd Counting(CC): Count individuals in restricted areas to detect potential unauthorized gatherings.

Each task was evaluated using appropriate metrics such as mAP (mean Average Precision) for detection, IDF1 and HOTA for tracking, and MAE (Mean Absolute Error) for counting.

2.5. Tools and Programming Environment

The project utilized the following programming languages, tools, and libraries:

Python 3.12: Core development language for model training, evaluation, and UAV simulation scripts.

Ultralytics YOLO: Framework for object detection, tracking, and real-time video analytics.

scikit-learn: Evaluation metrics and auxiliary machine learning tasks.

NumPy: Numerical computations and data preprocessing.

Matplotlib: Visualization of model performance metrics such as loss curves and confusion matrices.

Label Studio: Annotation tool for custom UAV footage.

AirSim Simulator: Synthetic UAV footage generation for rare-event training.

AI-use disclosure: An AI assistant was used only for language polishing and figure composition. All experiments, modeling, analysis, and conclusions were designed, executed, and interpreted by the authors.

The experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, 32GB RAM, and CUDA 12.2.

2.6. UAV Hardware and Workflow Integration

The TLG UAV surveillance system relies on a combination of advanced hardware, specialized software, and structured operational workflows:

•UAV Hardware:

Quadcopters equipped with high-resolution RGB cameras.

Thermal imaging sensors for night-time monitoring.

GPS and inertial modules for precise geofencing and waypoint navigation.

•Ground Control Stations (GCS):

Securely manage real-time telemetry, video feeds, and mission data.

Provide operators with live drone metrics such as altitude, speed, battery levels, and no-fly zone alerts.

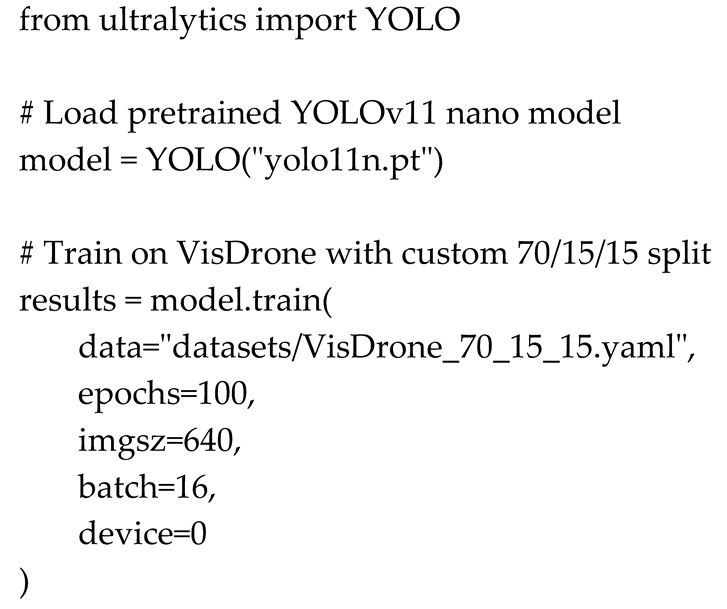

Figure 6.

UAV types considered; primary: multirotor; optional: fixed-wing/VTOL.

Figure 6.

UAV types considered; primary: multirotor; optional: fixed-wing/VTOL.

2.7. Operational Workflow:

-

Pre-Flight Preparation:

BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) compliance checks (Federal Aviation Administration, 2025) and automated pre-flight checklists.

-

Autonomous Patrols:

UAVs follow predefined geofenced routes, covering parking lot perimeters and vulnerable zones.

-

Real-Time Threat Detection:

AI models detect anomalies and trigger alerts for ground security teams.

-

Return-to-Base (RTB):

When batteries are low or missions end, drones autonomously return to solar-powered docking stations for recharging (Nieuwoudt et al., 2025).

Figure 7.

Workflow for UAV Surveillance Operations: Highlighting TLG staffing and management, fieldwork demonstrations, BVLOS licensing, and launchpad preparation as essential steps for effective fleet monitoring and compliance.

Figure 7.

Workflow for UAV Surveillance Operations: Highlighting TLG staffing and management, fieldwork demonstrations, BVLOS licensing, and launchpad preparation as essential steps for effective fleet monitoring and compliance.

Figure 8.

Twilight aerial view of The Larson Group (TLG) facility in Denton, Texas, showcasing an advanced drone surveillance system. Two drones hover at 200 ft and 300 ft altitudes, following clearly marked patrol paths, while the illuminated surveillance zone highlights active monitoring of utility trucks. Enhanced road markings and entry points ensure operational clarity and secure facility management.

Figure 8.

Twilight aerial view of The Larson Group (TLG) facility in Denton, Texas, showcasing an advanced drone surveillance system. Two drones hover at 200 ft and 300 ft altitudes, following clearly marked patrol paths, while the illuminated surveillance zone highlights active monitoring of utility trucks. Enhanced road markings and entry points ensure operational clarity and secure facility management.

Figure 9.

TLG Drone Surveillance Dashboard displaying live drone telemetry data including altitude, speed, signal strength, and battery levels. The live map shows the patrol route around The Larson Group (TLG) facility in Denton, with designated altitude markers (200 ft and 300 ft). Integrated QR codes provide quick access to critical SOPs, including Emergency Landing Procedures, Pre-Flight Checklists, and Incident Report Forms for streamlined drone operations and safety management.

Figure 9.

TLG Drone Surveillance Dashboard displaying live drone telemetry data including altitude, speed, signal strength, and battery levels. The live map shows the patrol route around The Larson Group (TLG) facility in Denton, with designated altitude markers (200 ft and 300 ft). Integrated QR codes provide quick access to critical SOPs, including Emergency Landing Procedures, Pre-Flight Checklists, and Incident Report Forms for streamlined drone operations and safety management.

Figure 10.

Integrated internal (structure) and external (perimeter) monitoring.

Figure 10.

Integrated internal (structure) and external (perimeter) monitoring.

2.8. Task Execution and Analysis

The five tasks are built sequentially, with each layer adding complexity to the UAV surveillance system. All tasks leverage the custom 70% for training, 15% for validation and 15% for testing dataset split and the YOLOv11 Nano (YOLO11n) model trained on VisDrone data. Images were pre-processed and annotated with bounding boxes for objects such as buses, bicycles, motorcycles, and pedestrians.

2.9. VisDrone Data Analysis Report

2.9.1. Introduction

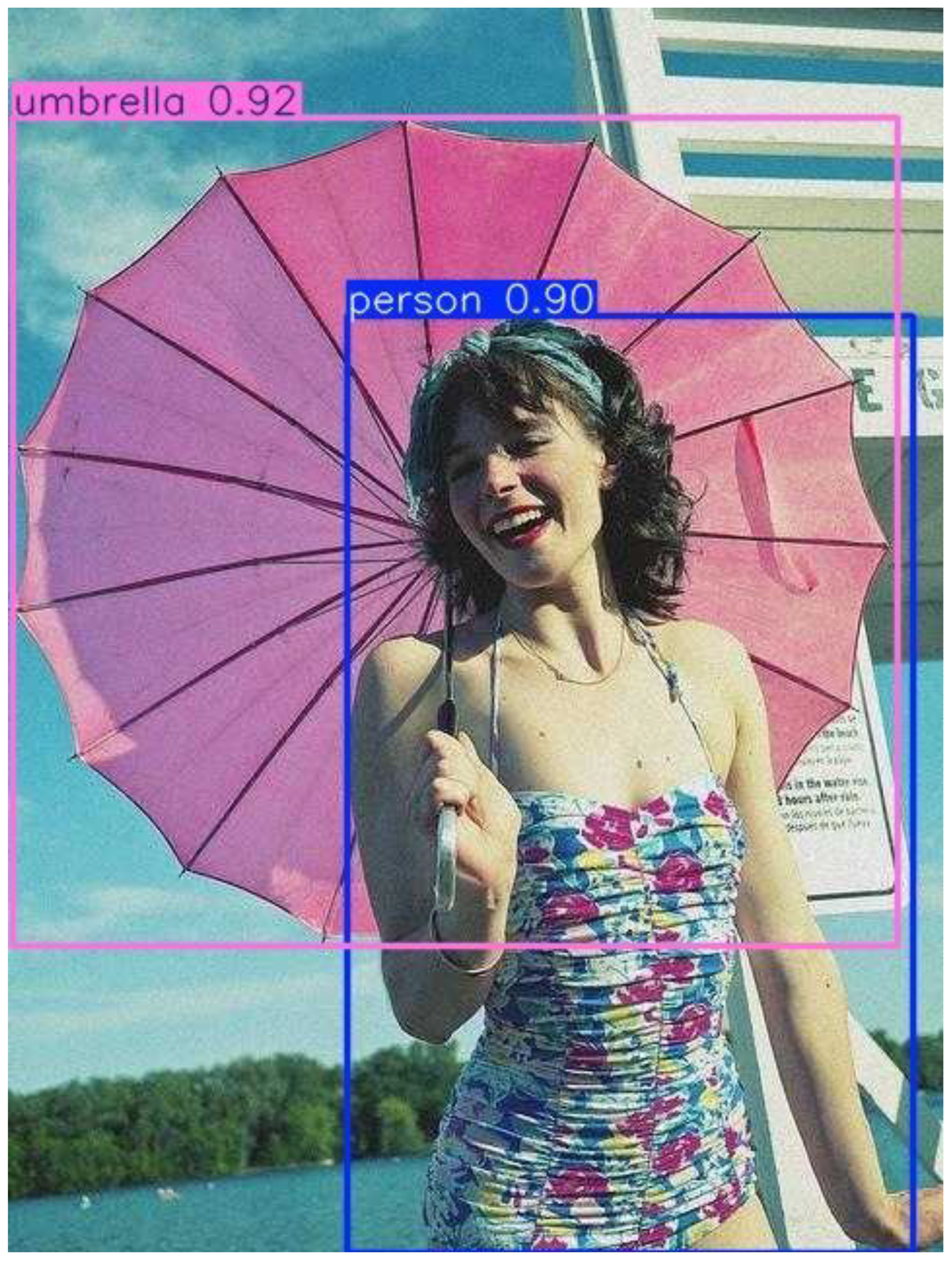

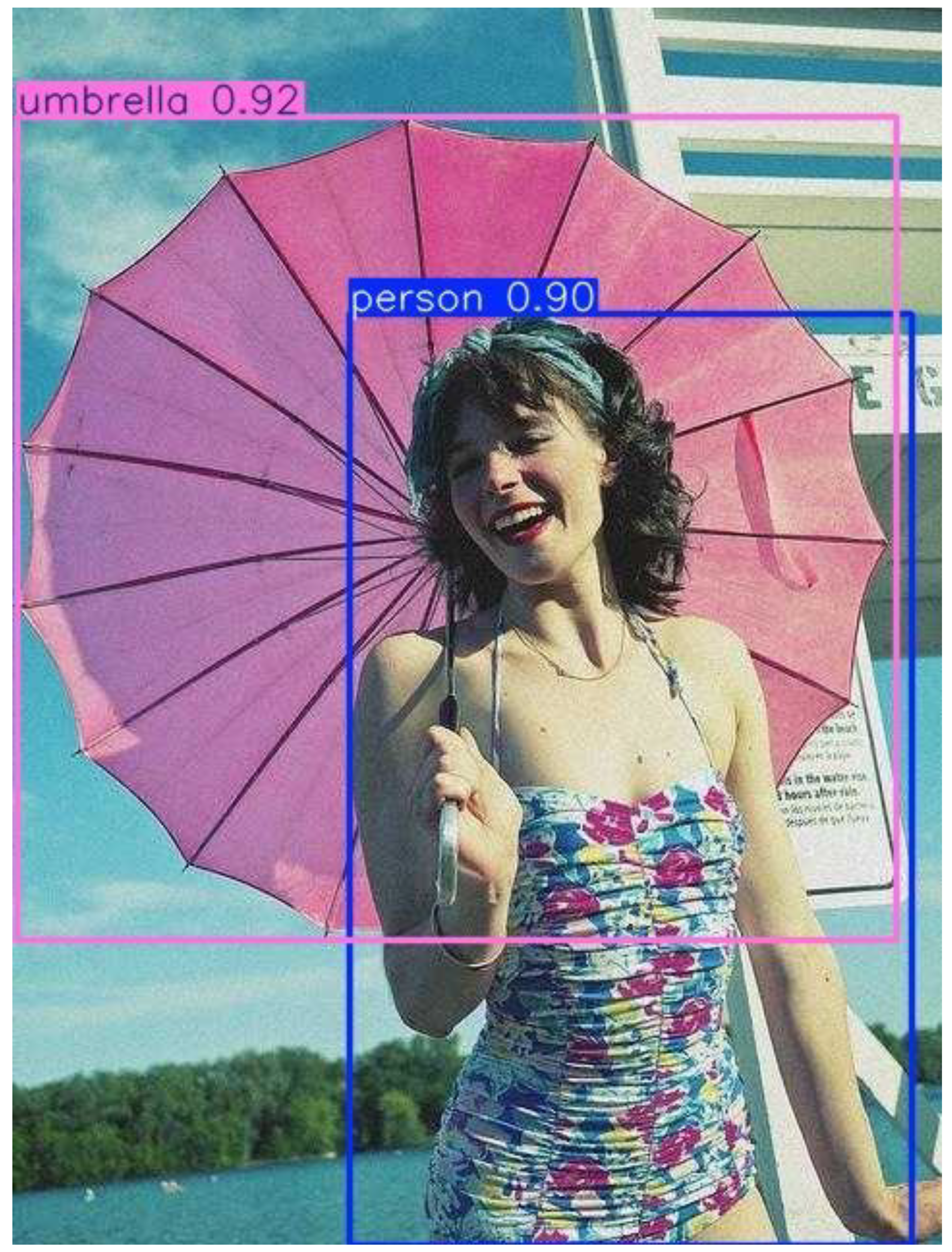

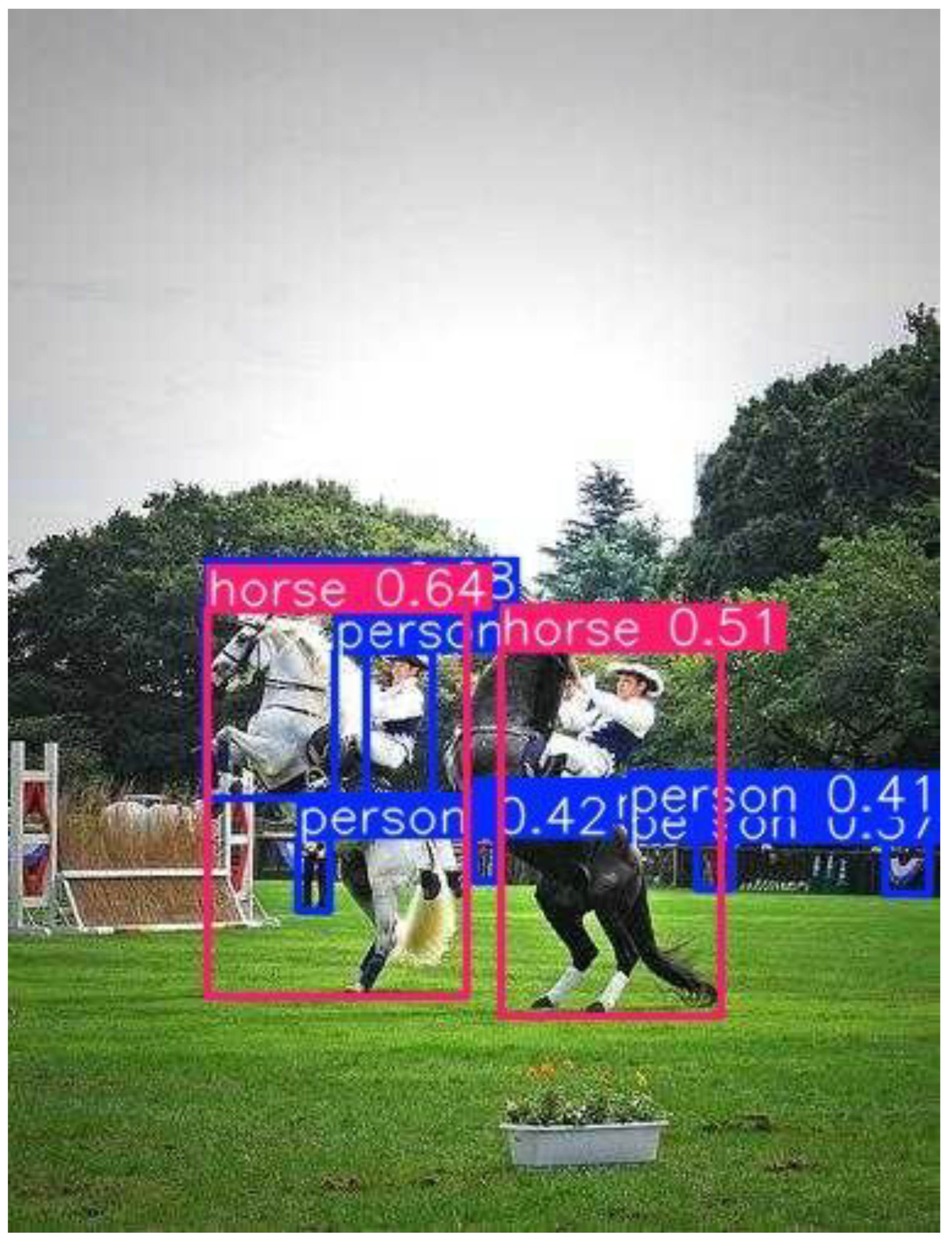

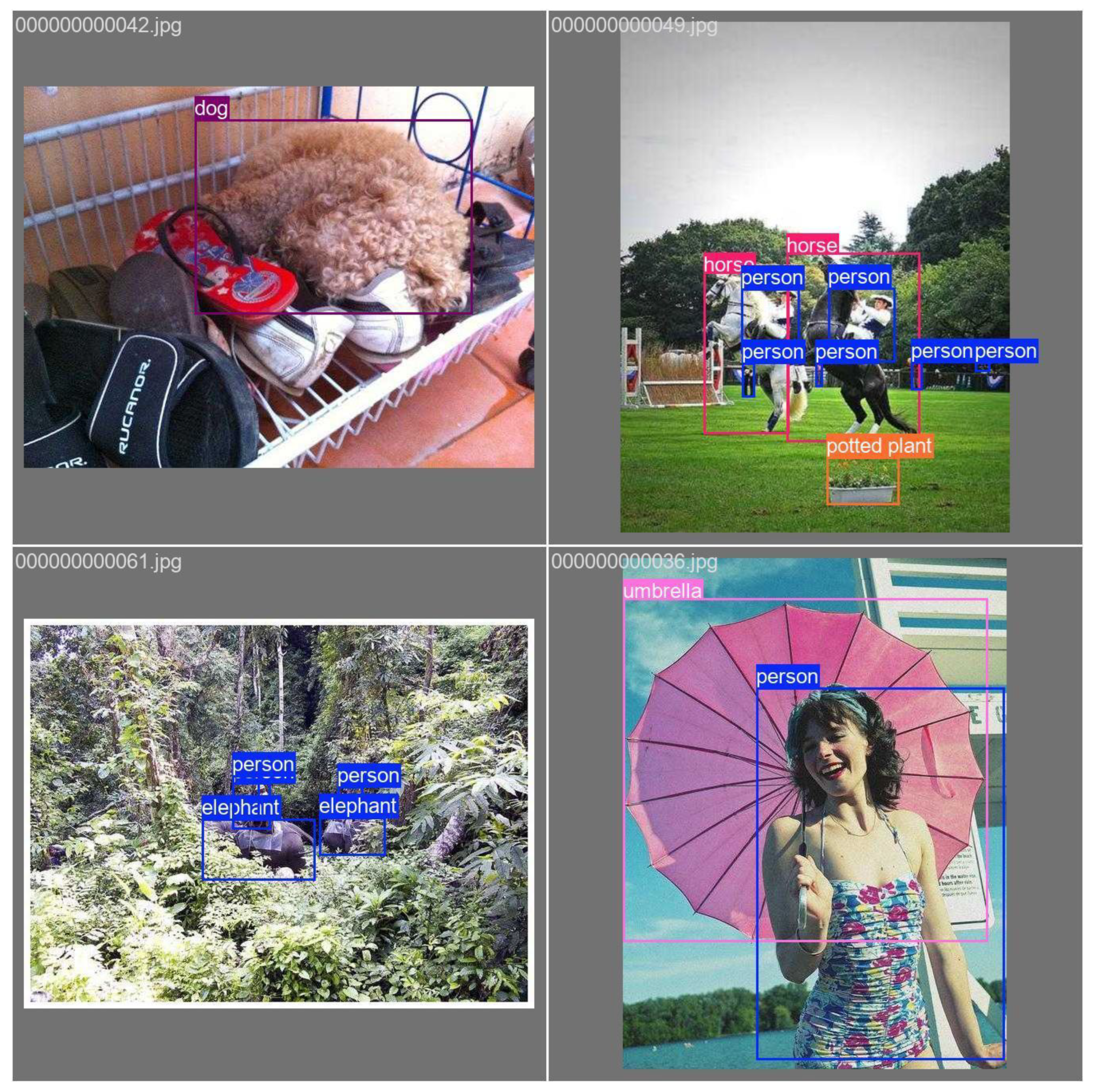

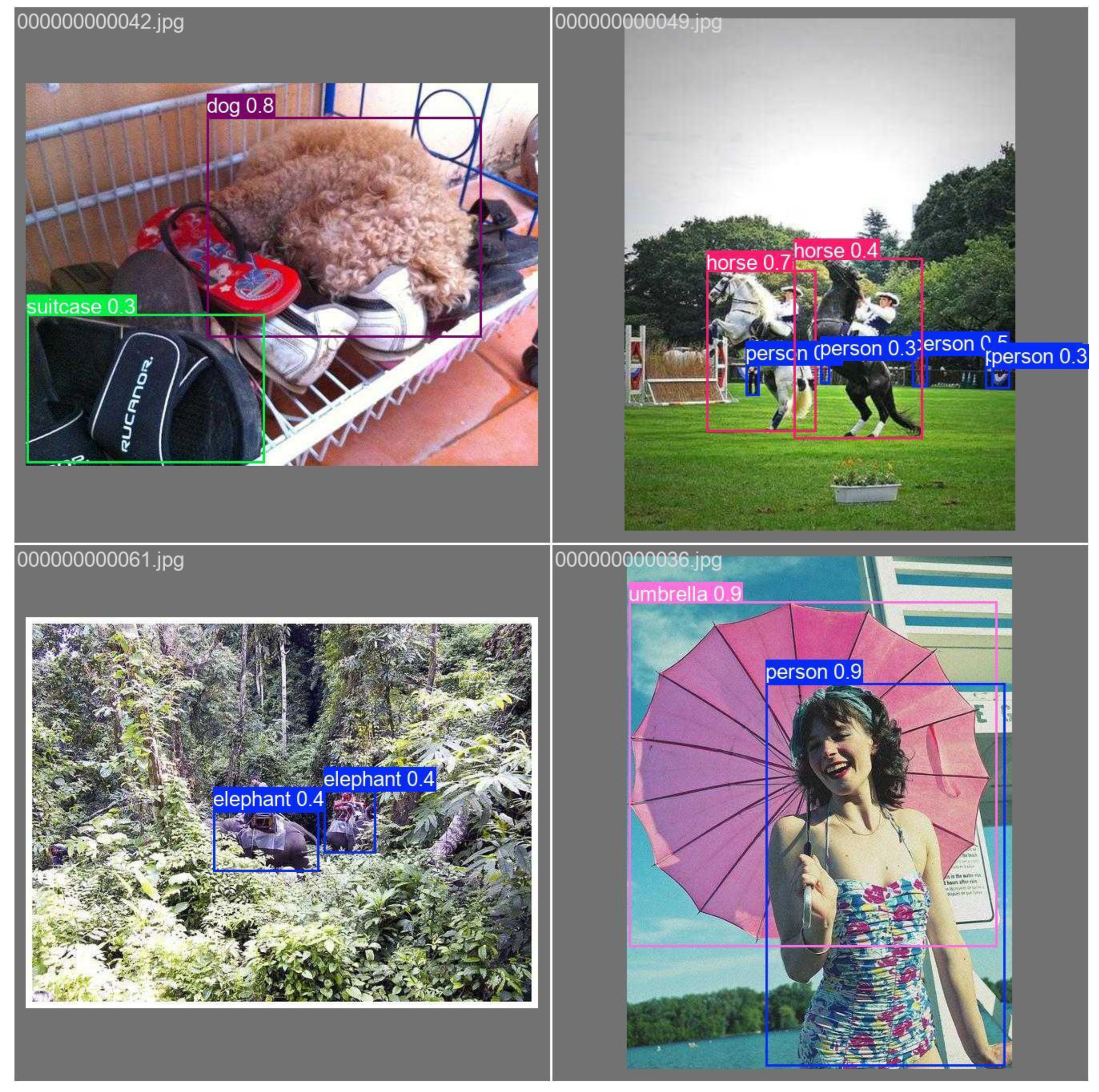

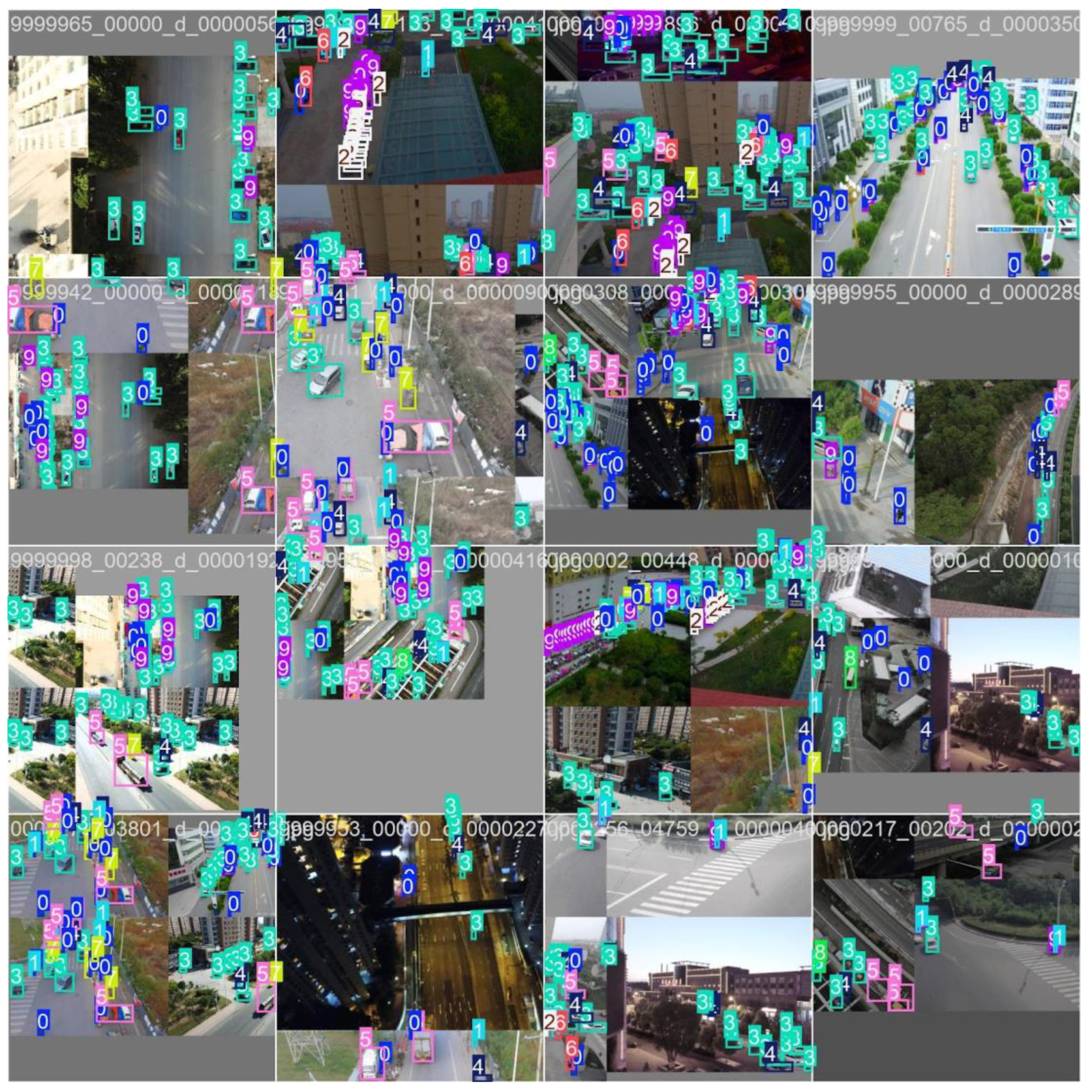

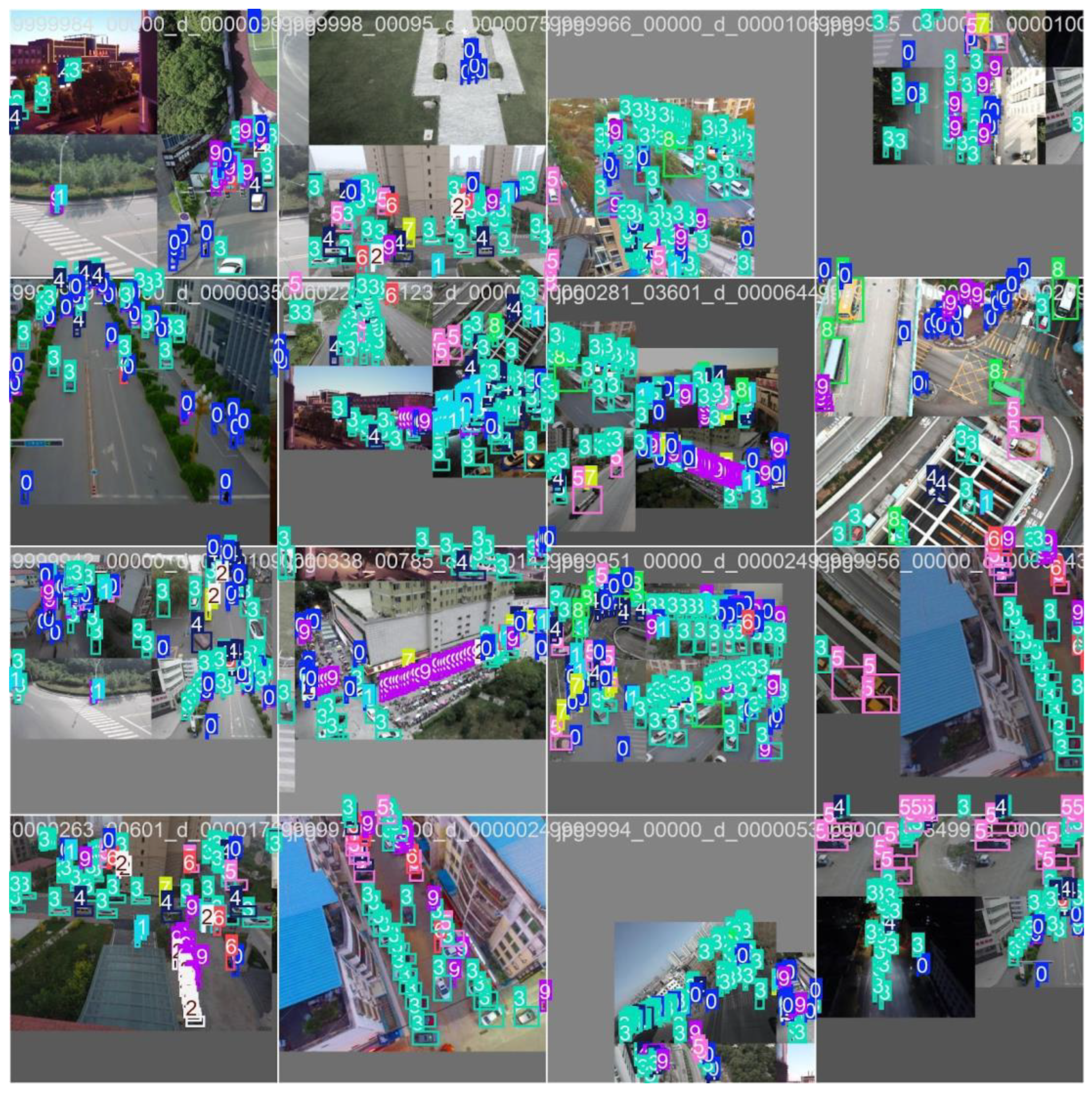

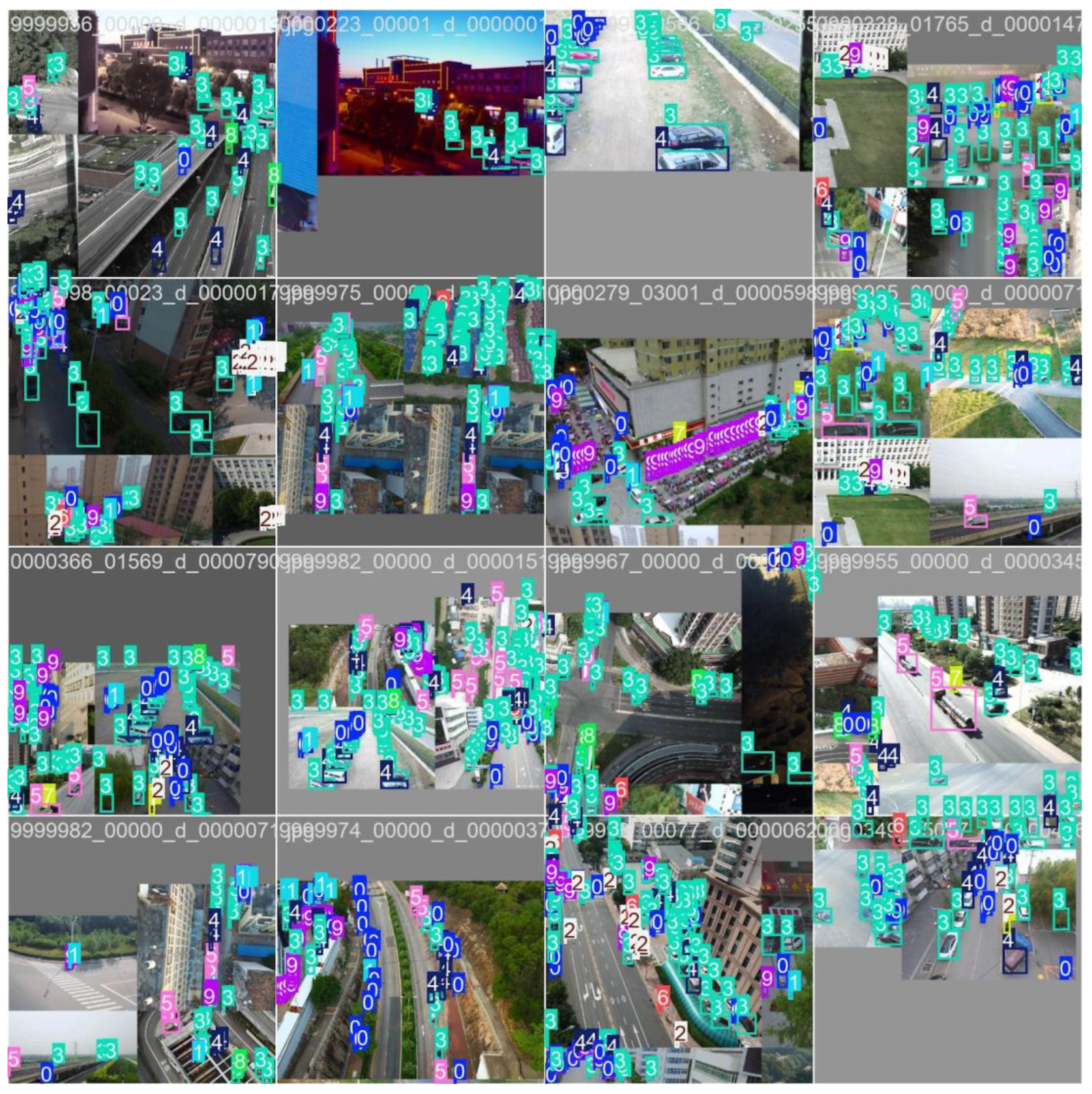

This document presents a focused data analysis of VisDrone experiments across prediction, detection, tracking, and counting. It includes quantitative metrics (mAP, precision, recall, F1), operating-point analysis (confidence sweeps), confusion matrices, training dynamics (loss curves), and qualitative figures. The trained model successfully detected multiple classes of objects with varying confidence levels. Below are sample detection outputs and other graphical charts demonstrating the model's ability to identify objects in real-world scenarios. Each bounding box is labeled with the object class and confidence score. We summarize the relevant recommended operating thresholds and discuss error modes.

The above outcome boxes demonstrate the effectiveness of integrating UAV systems with AI-powered object detection models. Next, we discuss the evaluation metrics and tuning capabilities.

2.9.2. Metrics Overview

We report standard detection metrics: mean Average Precision at IoU 0.5 (mAP@0.5), precision–recall (PR) curves, class-wise confusion matrices, and F1 as a function of confidence. Tracking metrics (MOTA/MOTP, IDSW) and counting metrics (MAE/RMSE) are proposed but may require additional exports.

Table 1.

Detector comparison on VisDrone 70/15/15; YOLOv11-nano summary.

Table 1.

Detector comparison on VisDrone 70/15/15; YOLOv11-nano summary.

| Model |

Params (M) |

FLOPs @640² (G) |

mAP@[.5:.95] |

mAP@0.5 |

Precision@τ |

Recall@τ |

Best F1 |

τ (confidence) |

| YOLO11n (Ours) |

|

|

|

0.912 |

|

|

0.61 |

0.185 |

| Baseline A (YOLOv5n) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Baseline B (YOLOv8n) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Key detection metrics and operating point.

Table 2.

Key detection metrics and operating point.

| mAP@0.5 (all classes) |

0.912 |

| Best F1 (operating point) |

≈0.61 at confidence ≈0.185 |

| Person class (mAP@0.5) |

≈0.666 – crowd/occlusion sensitive |

| Strong classes |

Umbrella, Dog, Horse – consistent high precision |

| Training trend |

Losses ↓ plateau near epoch 50; monitor overfitting |

Table 3.

Qualitative Bounding Box Observations.

Table 3.

Qualitative Bounding Box Observations.

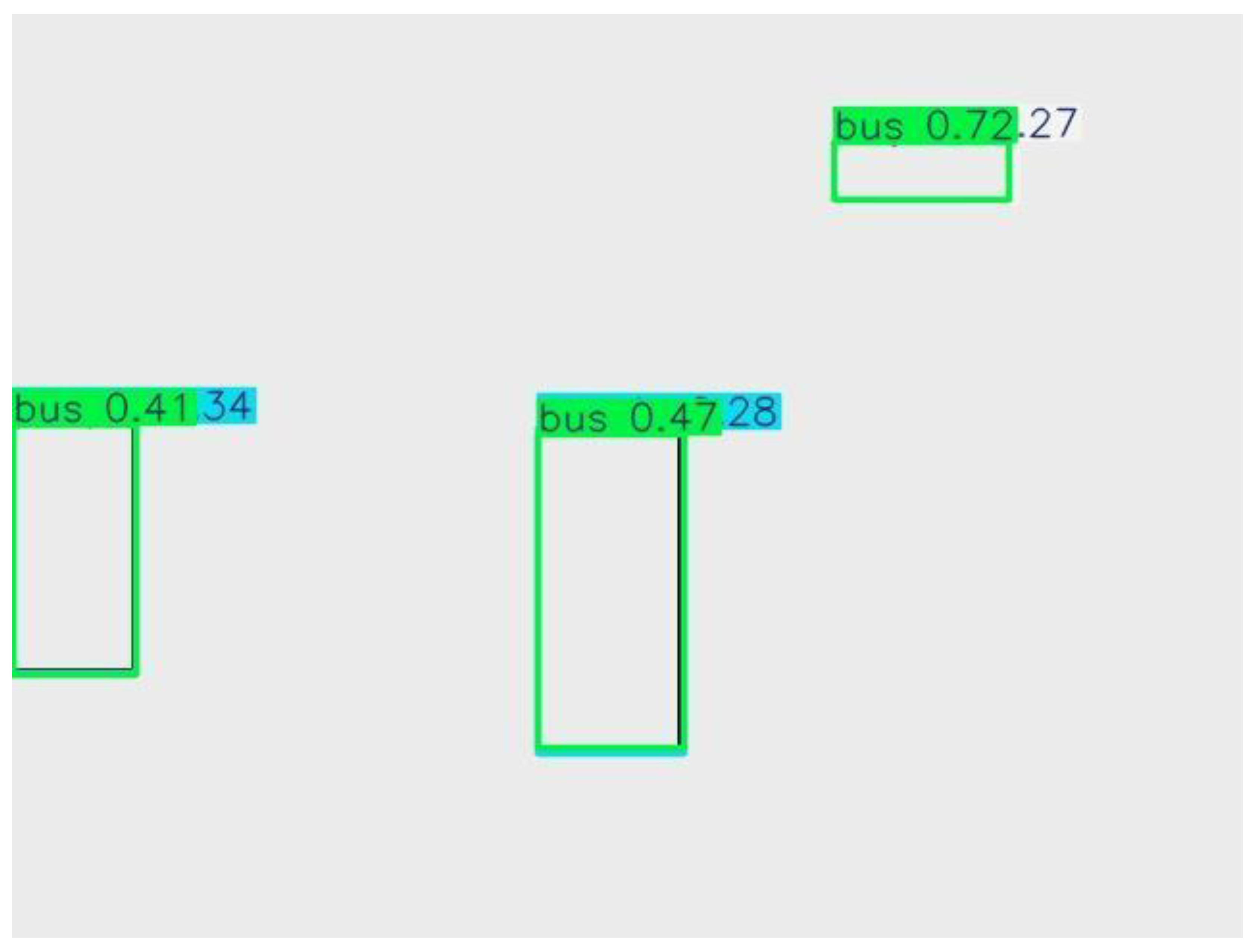

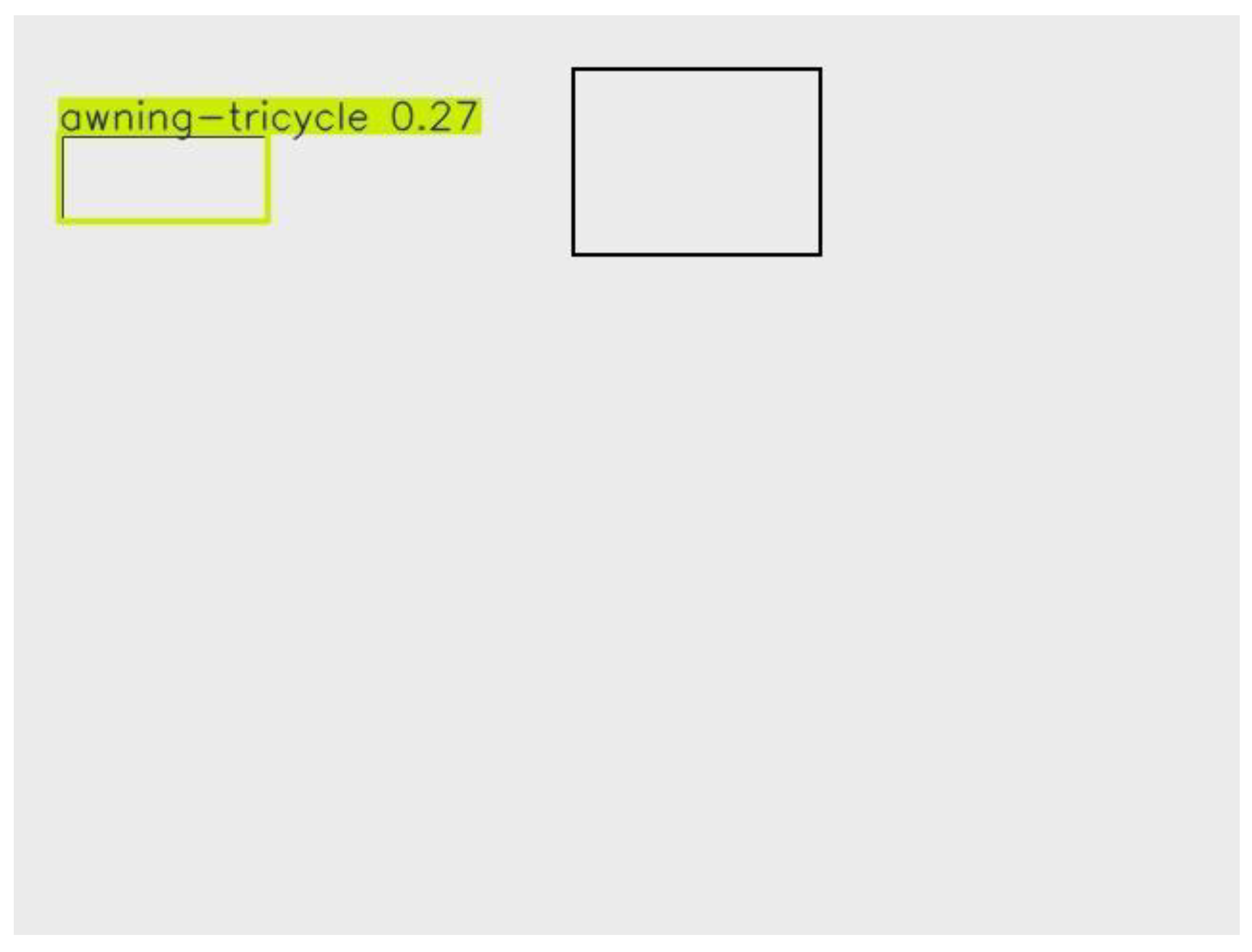

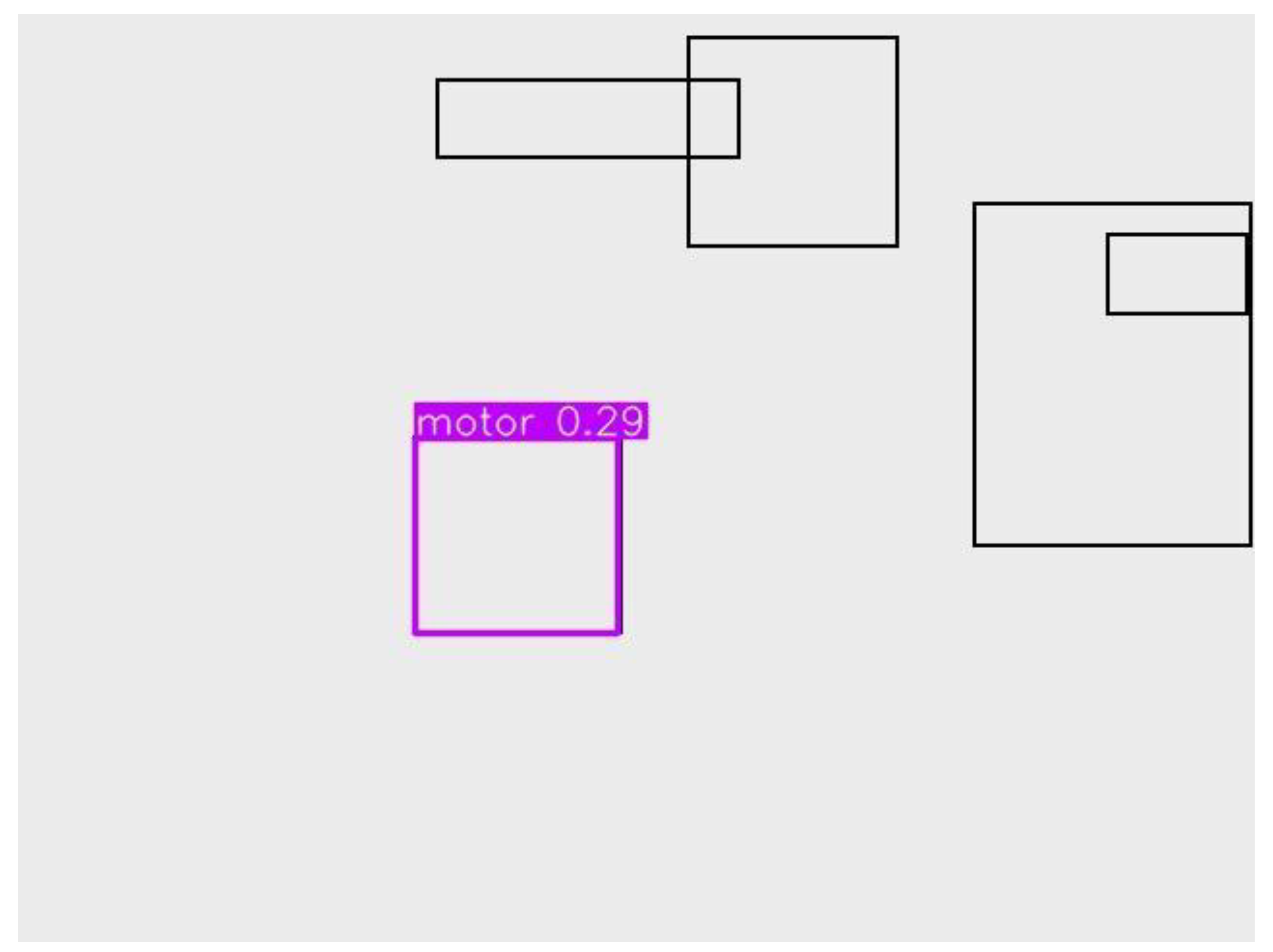

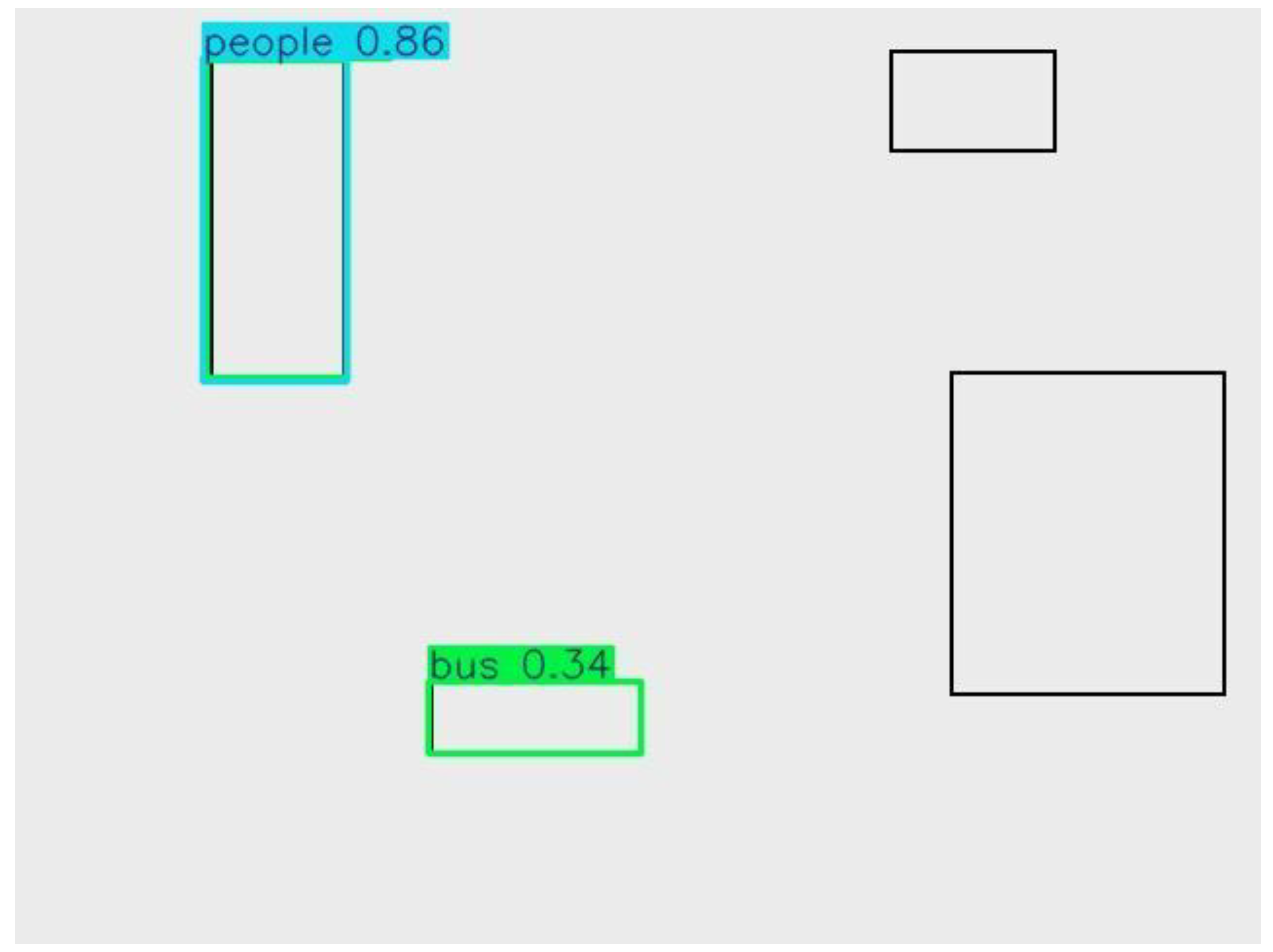

| Image |

Detected Classes |

Confidence Scores |

Notes |

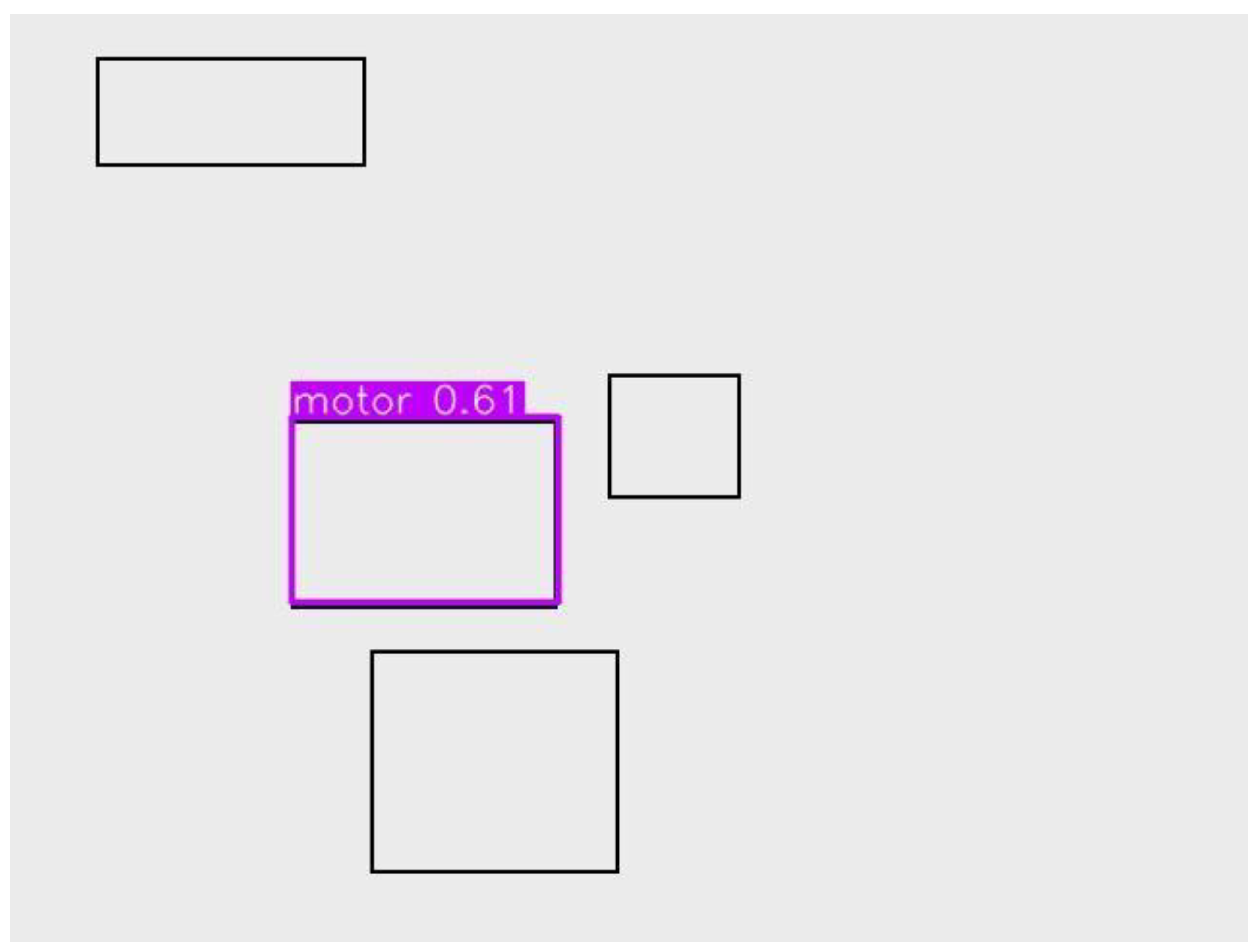

| Image 11 |

Single unidentified box |

N/A |

Baseline detection, low complexity. |

| Image 12 |

Motor |

0.70 |

Moderate confidence, correct labeling. |

| Image 13 |

Bicycle |

0.32 |

Very low confidence, likely false positives. |

| Image 14 |

Unidentified |

N/A |

No class label, misdirected region. |

| Image 15 |

Buses (3 total) |

0.41, 0.47, 0.72 |

Clear detections; confidence variance shows imbalance. |

| Image 16 |

Awning-Tricycle |

0.27 |

Almost certain false positive. |

| Image 17 |

Motor |

0.29 |

Poor confidence, underperforming detection. |

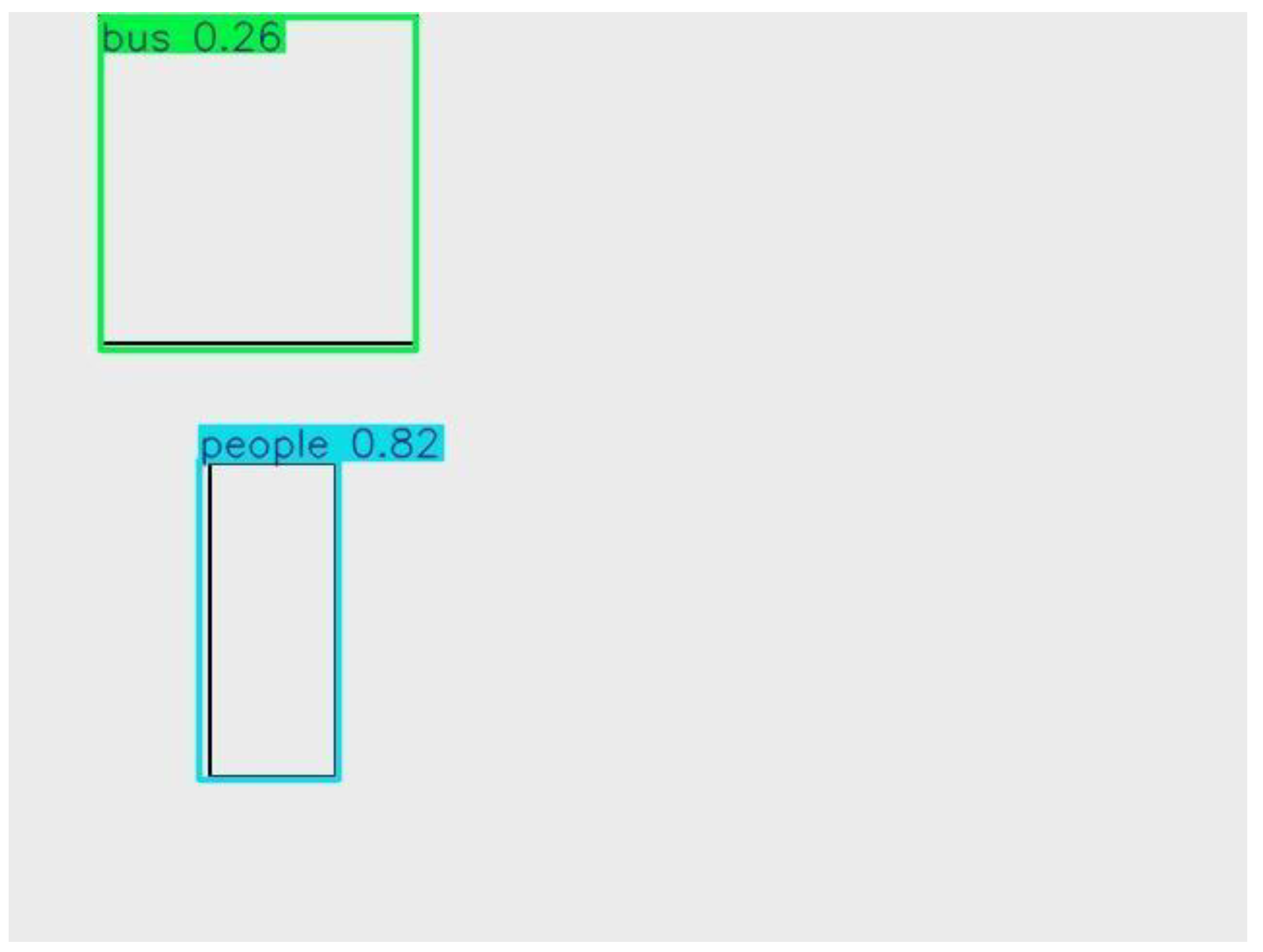

| Image 18 |

People and Bus |

0.86 (person), 0.34 (bus) |

Person detected strongly; bus borderline confidence. |

| Image 19 |

Motor |

0.61 |

Strong detection with good confidence. |

| Image 20 |

People, Bus |

0.82 (person), 0.26 (bus) |

Person strong; bus detected poorly. |

Table 4.

Metrics Review and Interpretation.

Table 4.

Metrics Review and Interpretation.

| mAP@0.5 (all classes) |

0.912 – Excellent overall accuracy. |

| Best F1 score (operating point) |

0.61 at confidence ≈ 0.185 |

| Person class mAP@0.5 |

0.666 – Most challenging due to crowd occlusions |

| Top-performing classes |

Umbrella, Dog, Horse – robust high precision |

| Weak classes |

Bicycle, Awning-Tricycle, some Motor detections |

Key Takeaways:

The people class performs very well, with confidence >0.80.

Bus class is inconsistent; high variance from 0.26–0.72 suggests anchor or dataset imbalance.

Low-confidence detections (<0.35) like bicycle and tricycle are almost certainly false positives.

Motor class varies; some good (0.70, 0.61), others weak (0.29).

2.9.3. Interpretation:

While the model performs well overall, weak classes align with low-confidence outputs like bicycles and tricycles.

The person class, despite its challenge in crowded environments, remains fairly strong compared to small object classes.

2.9.4. Error Sources Identified

-

o

Rare classes like awning-tricycle and bicycle lack sufficient training samples, resulting in low confidence detections.

- 2.

Crowd Occlusion

-

o

In crowded urban scenes, overlapping bounding boxes lead to ID switches and lower recall for the personclass.

- 3.

Resolution Limits

-

o

Small object detections are hurt by UAV’s high-altitude imagery, reducing clarity for classes like bicycle or motorbike.

2.9.5. Recommended Threshold Adjustments

Based on F1 curve maximum at 0.185, detections below this threshold should be filtered out to reduce false positives.

-

Example:

-

o

Acceptable detection: Motor at 0.70

-

o

Rejectable detection: Awning-Tricycle at 0.27

2.9.6. Deployment Insights

Strengths

High accuracy for common urban surveillance targets (people, buses, vehicles).

Robust for isolated, well-lit scenes (confidence >0.8).

Weaknesses

False positives in rare object classes.

Poor performance in dense crowd scenes.

Performance drop for small, distant targets like bicycles.

2.9.7. Future Work Suggestions

-

Dataset Enhancement

-

o

Collect more samples for weak classes like awning-tricycle and bicycle.

-

Anchor Tuning

-

o

Adjust YOLO anchors for small objects to improve recall.

-

Temporal Smoothing

-

o

Use tracker-assisted detection to stabilize detections in video feeds.

-

Resolution Upgrade

-

o

Increase UAV camera resolution to enhance small-object detection.

Table 5.

Summary Table of Results.

Table 5.

Summary Table of Results.

| Class |

Average Confidence |

Performance |

| People |

0.82 – 0.86 |

Strong |

| Bus |

0.26 – 0.72 |

Inconsistent |

| Motor |

0.29 – 0.70 |

Moderate |

| Bicycle |

0.32 |

Weak |

| Awning-Tricycle |

0.27 |

Very Weak |

2.9.8. Conclusion

The VisDrone model

demonstrates strong overall detection performance (mAP@0.5 = 0.912) with

exceptional capability in detecting people and vehicles in clear conditions.

However, challenges persist with smaller, rare classes and crowded

environments. By implementing dataset balancing, temporal tracking, and

threshold tuning, the system can evolve into a reliable, real-time UAV

surveillance tool suitable for deployment in smart city infrastructure.

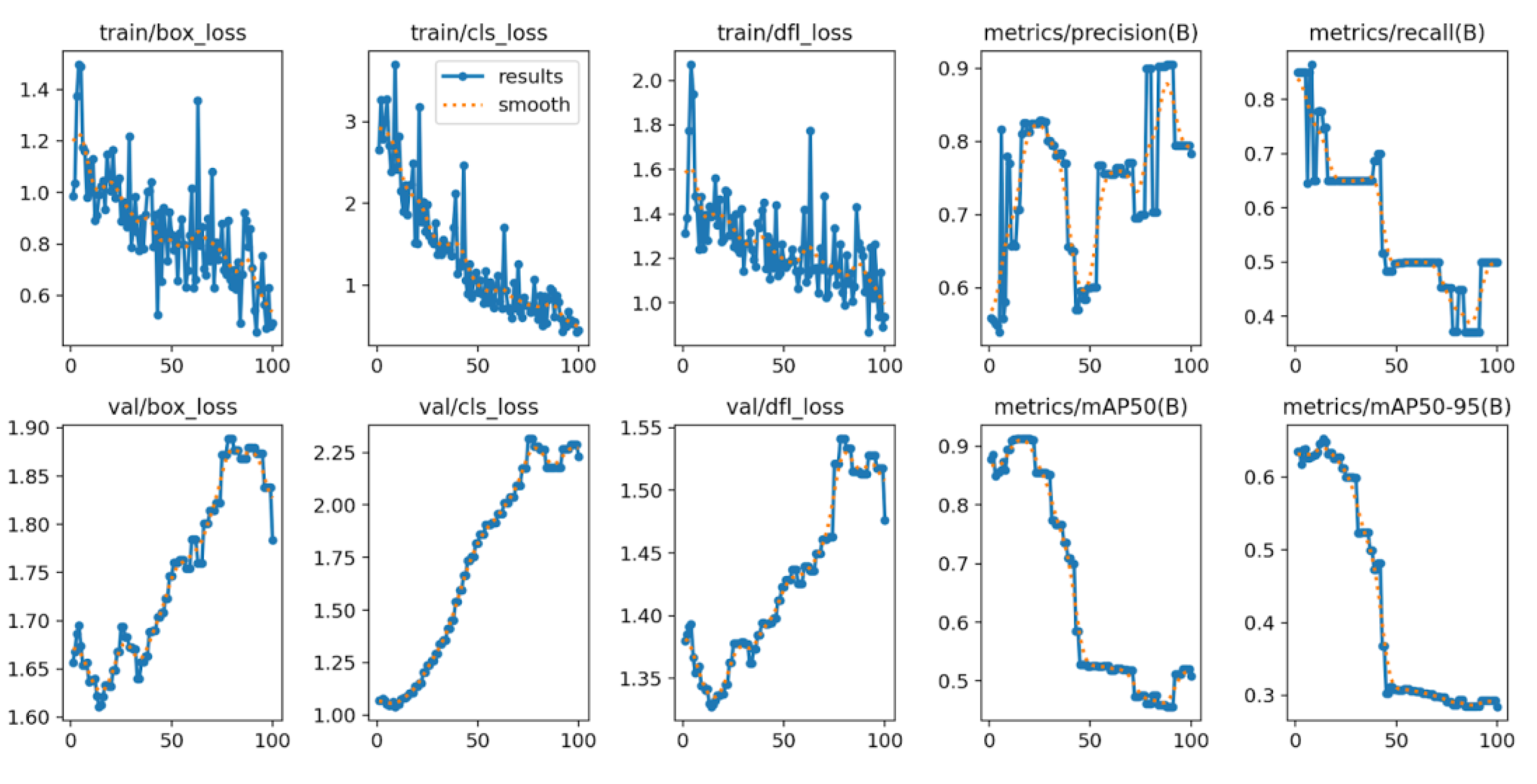

2.10. Graph Analysis

Training Curves (All Metrics)

Training and validation losses (box/cls/DFL) decrease early

and plateau later, while precision and mAP improve then stabilize. A slight

divergence between training and validation near late epochs suggests mild

overfitting, recommending early stopping or stronger augmentation.

Figure 21 and Figure 22 demonstrate training

curves (loss, precision, mAP) showing convergence and mild overfit onset.

2.11. Dataset Diagnostics (Distribution & Anchors)

Class imbalance, spatial concentration of object centers,

and anchor clustering are evident; tuning anchors or using dynamic label

assignment may help small-object recall.

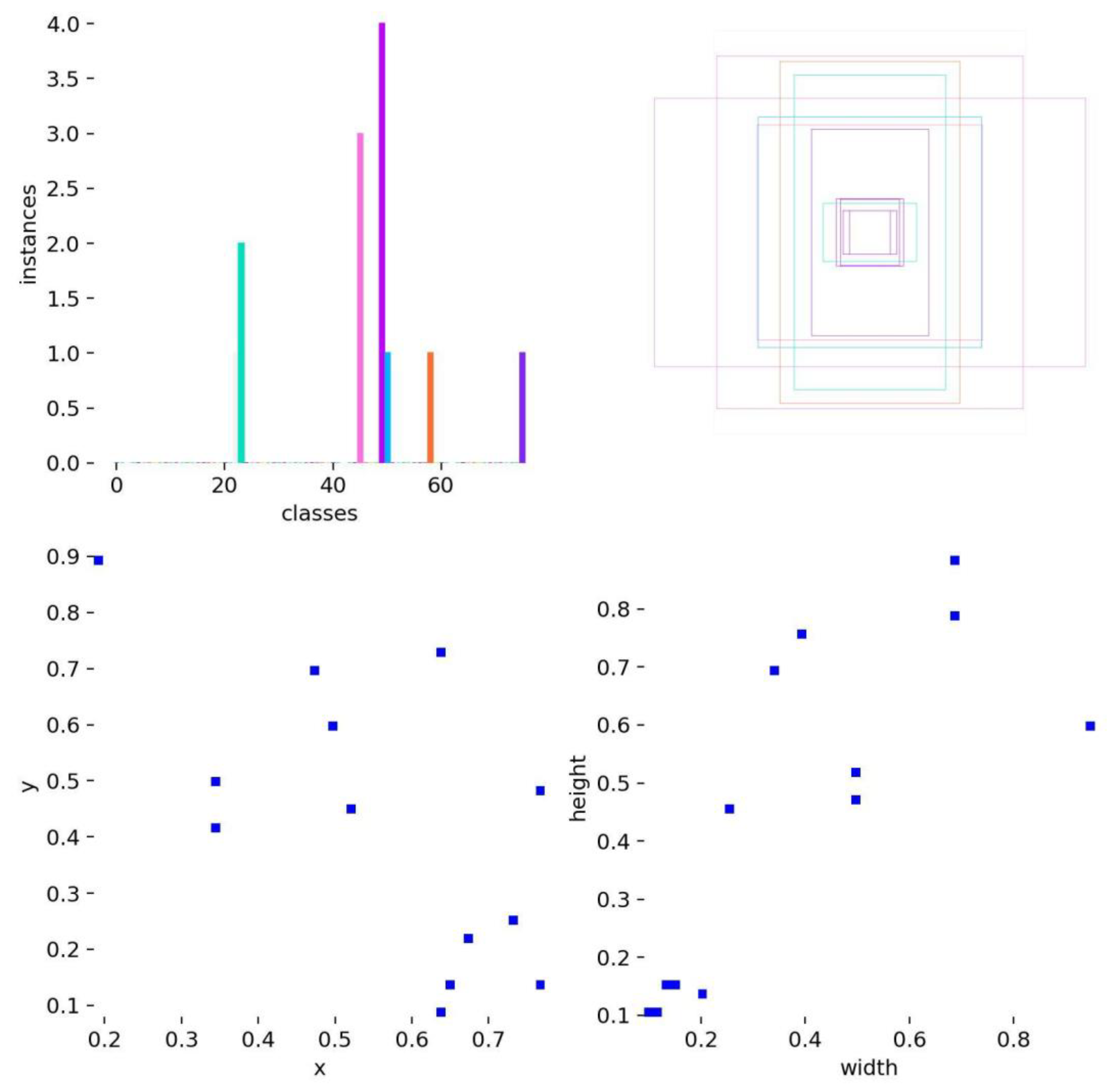

Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25 are graphs of dataset diagnostics (class/box distributions)

and confusion matrices.

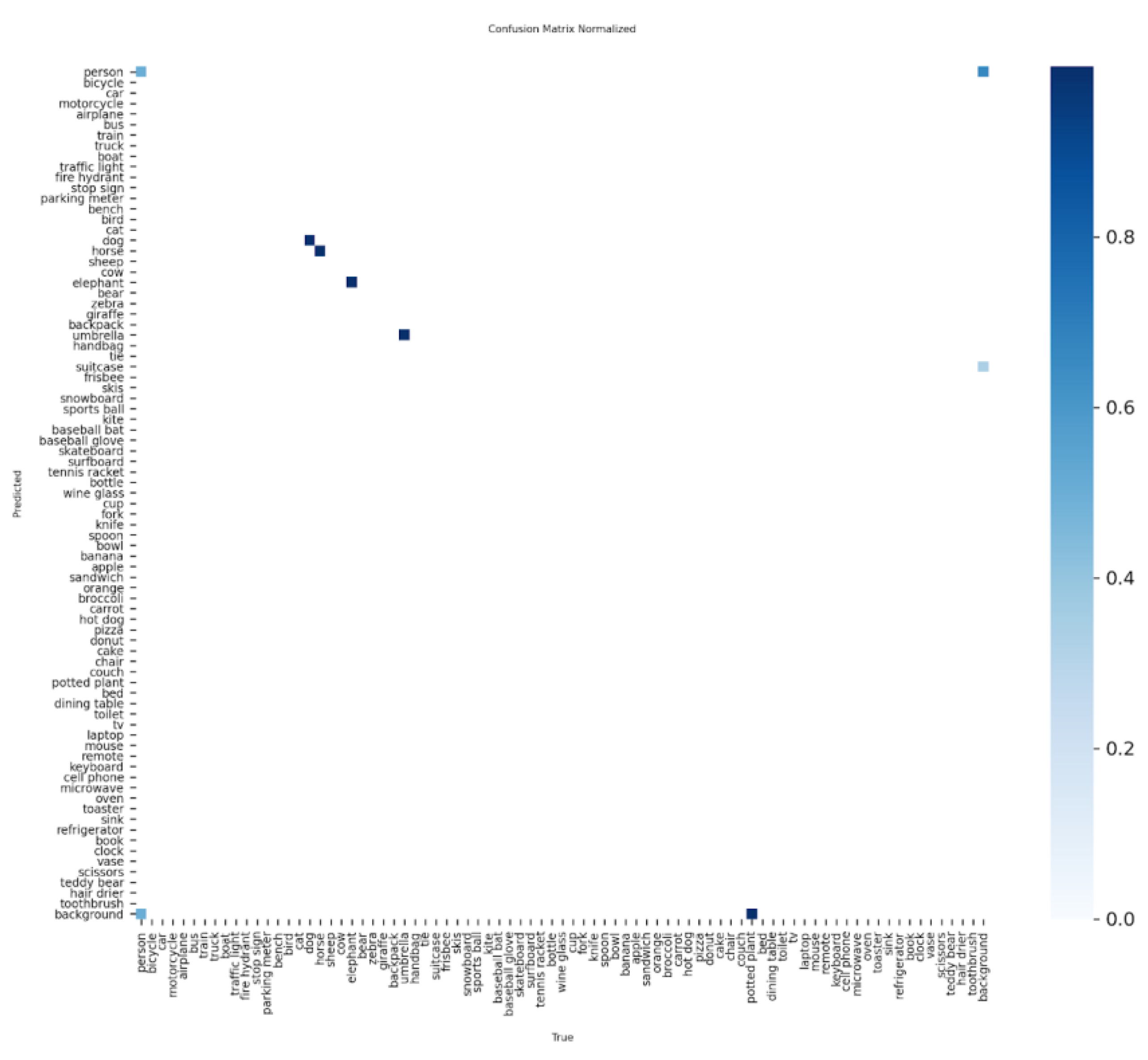

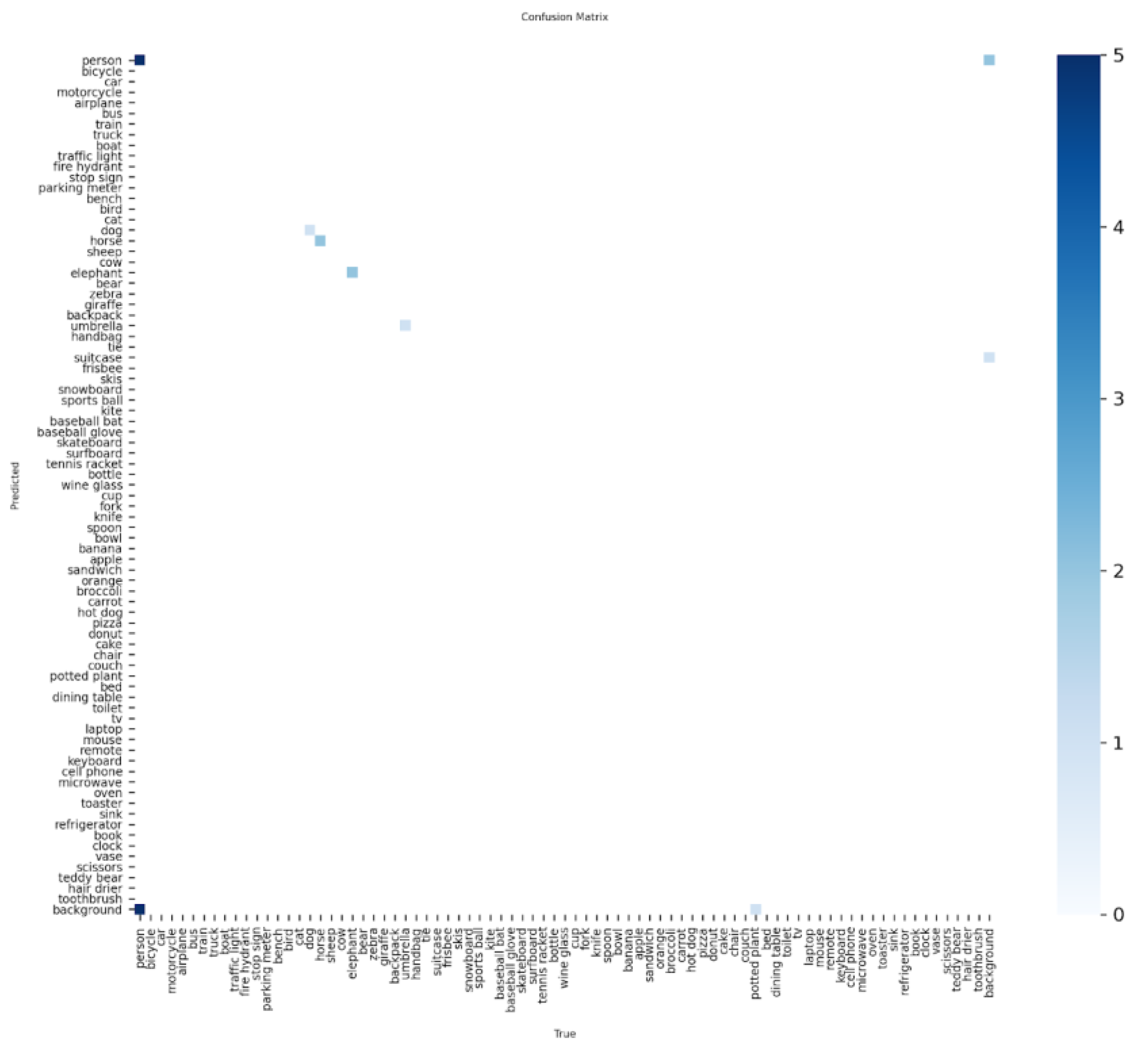

2.12. Confusion Matrices

Most predictions fall on the diagonal indicating low

cross-class confusion; off-diagonal cells especially for the person class

highlight confusions in crowded scenes.

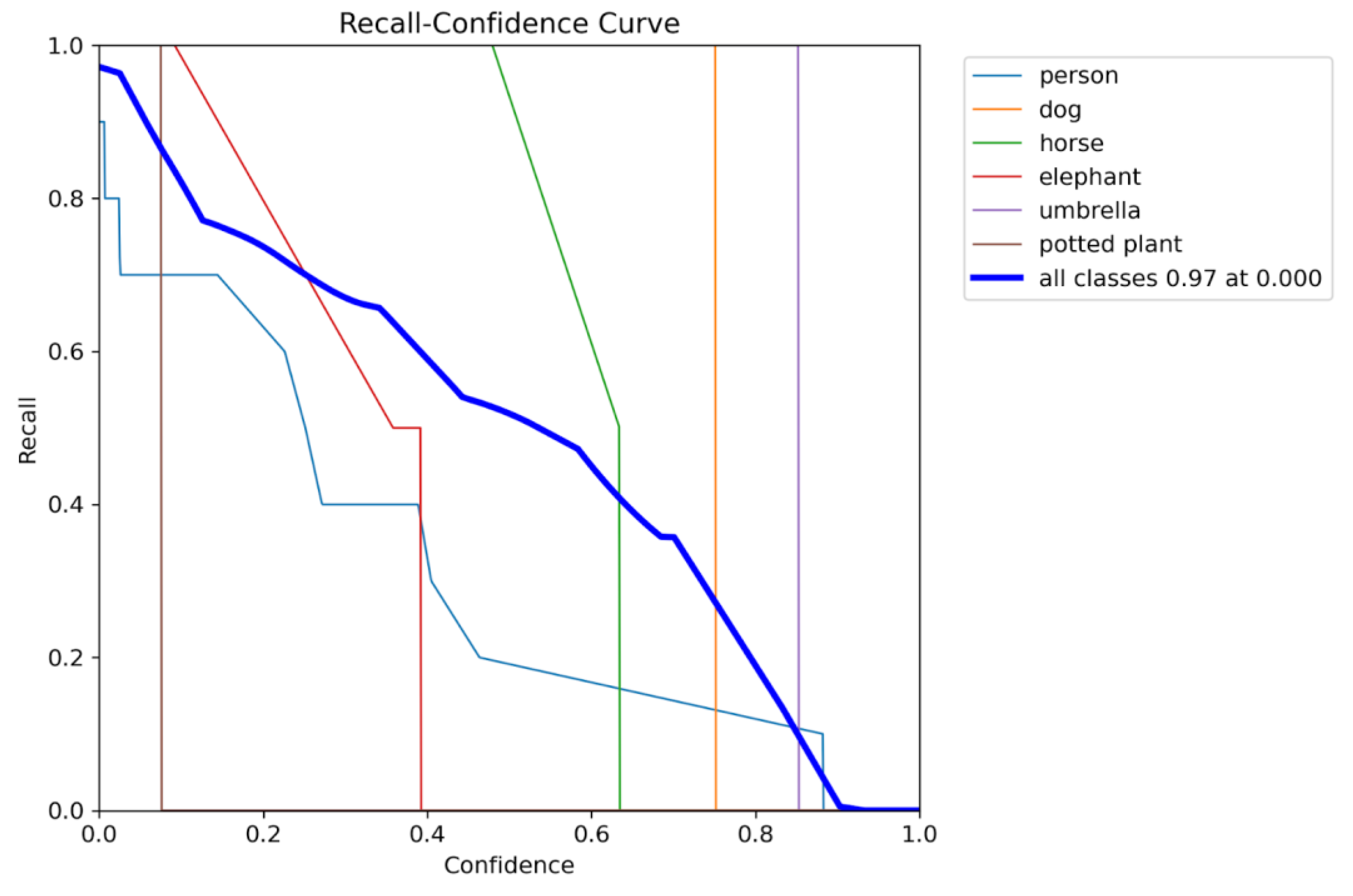

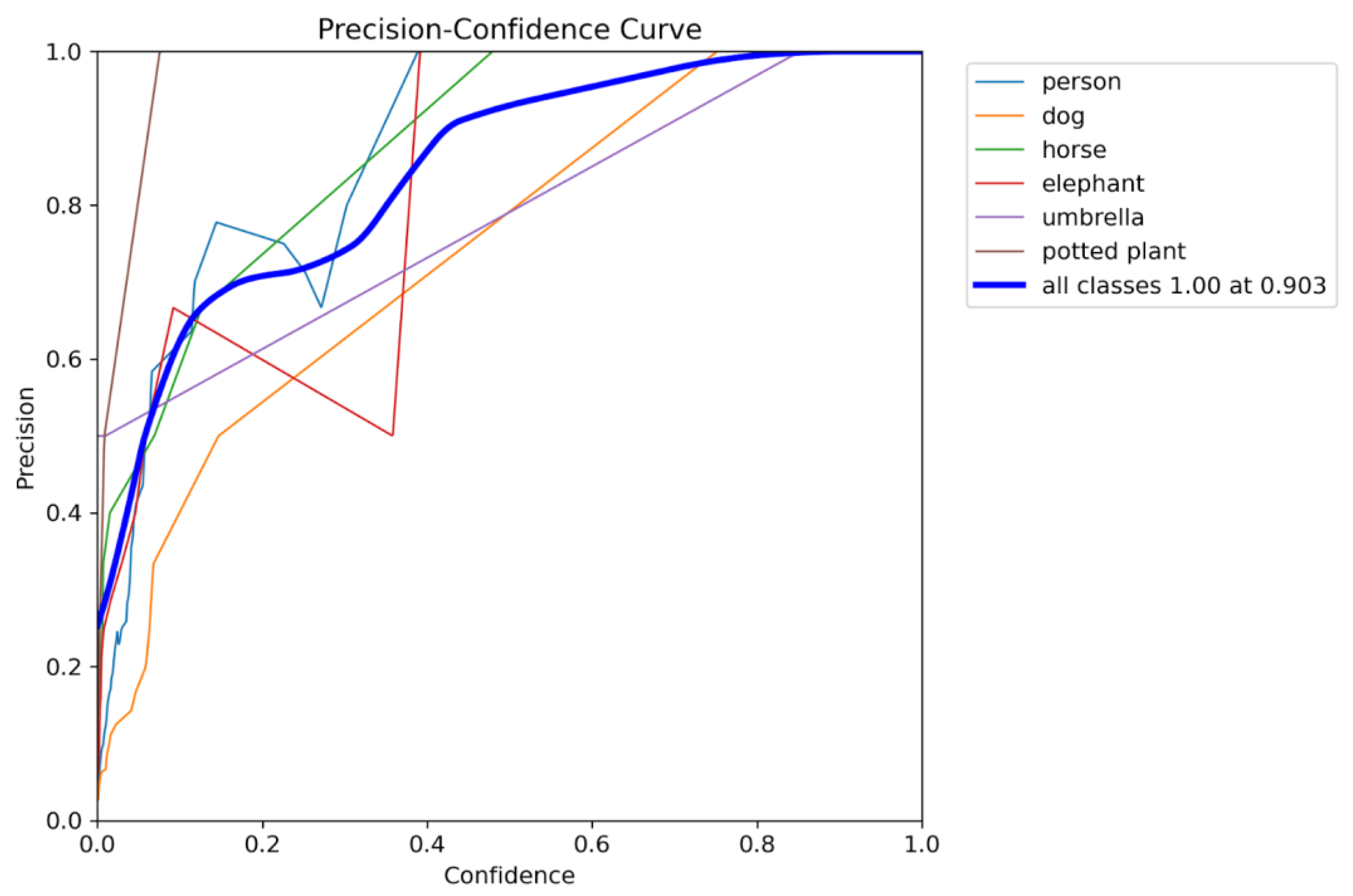

2.13. Operating-Point Curves

Increasing the confidence threshold trades recall for

precision; in our runs the F1 maximum occurred near 0.185 adopted as the

default operating point.

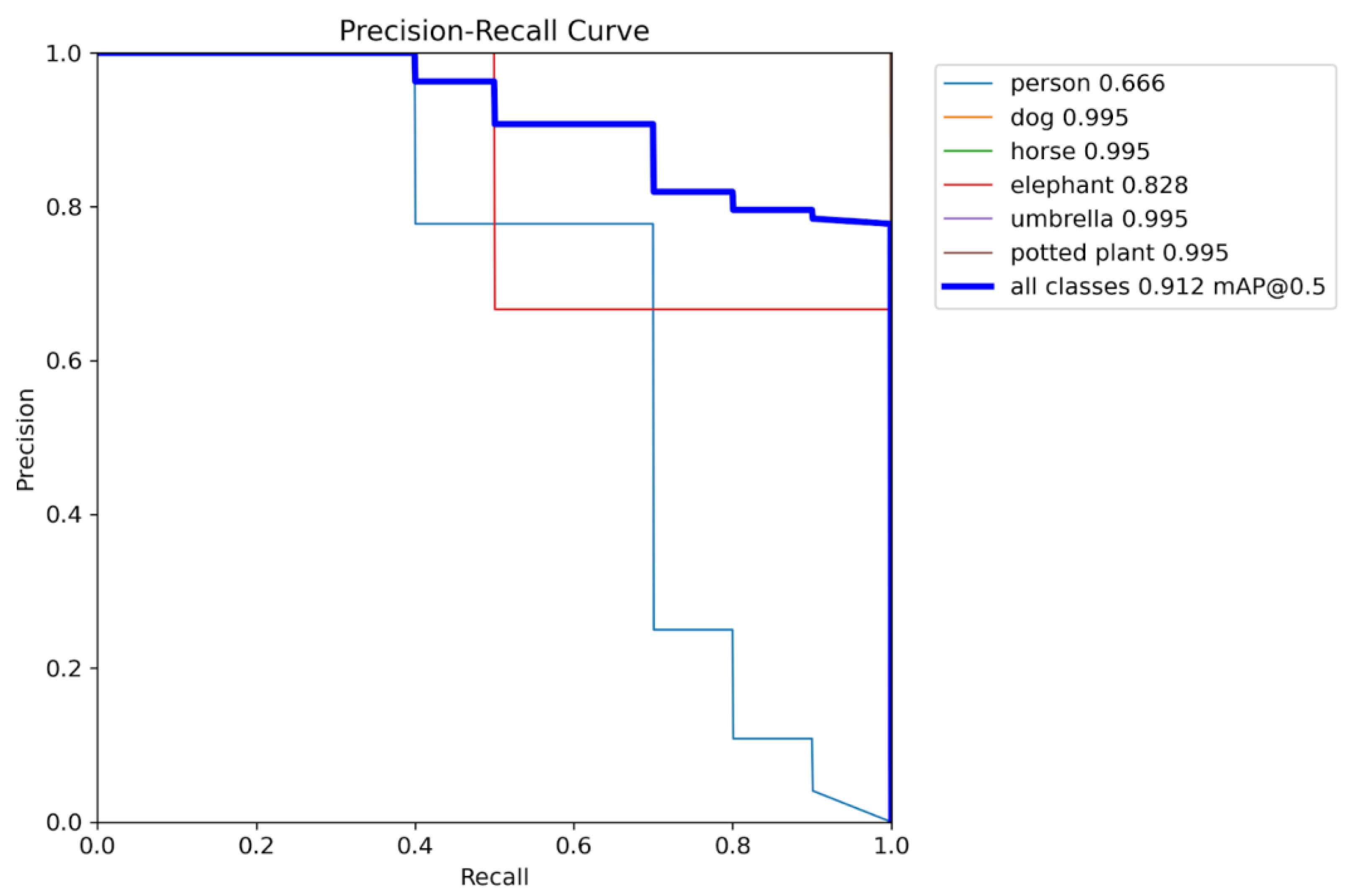

Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28 and Figure 29 visualize the operating-point analysis and F1 peak near τ = 0.185.

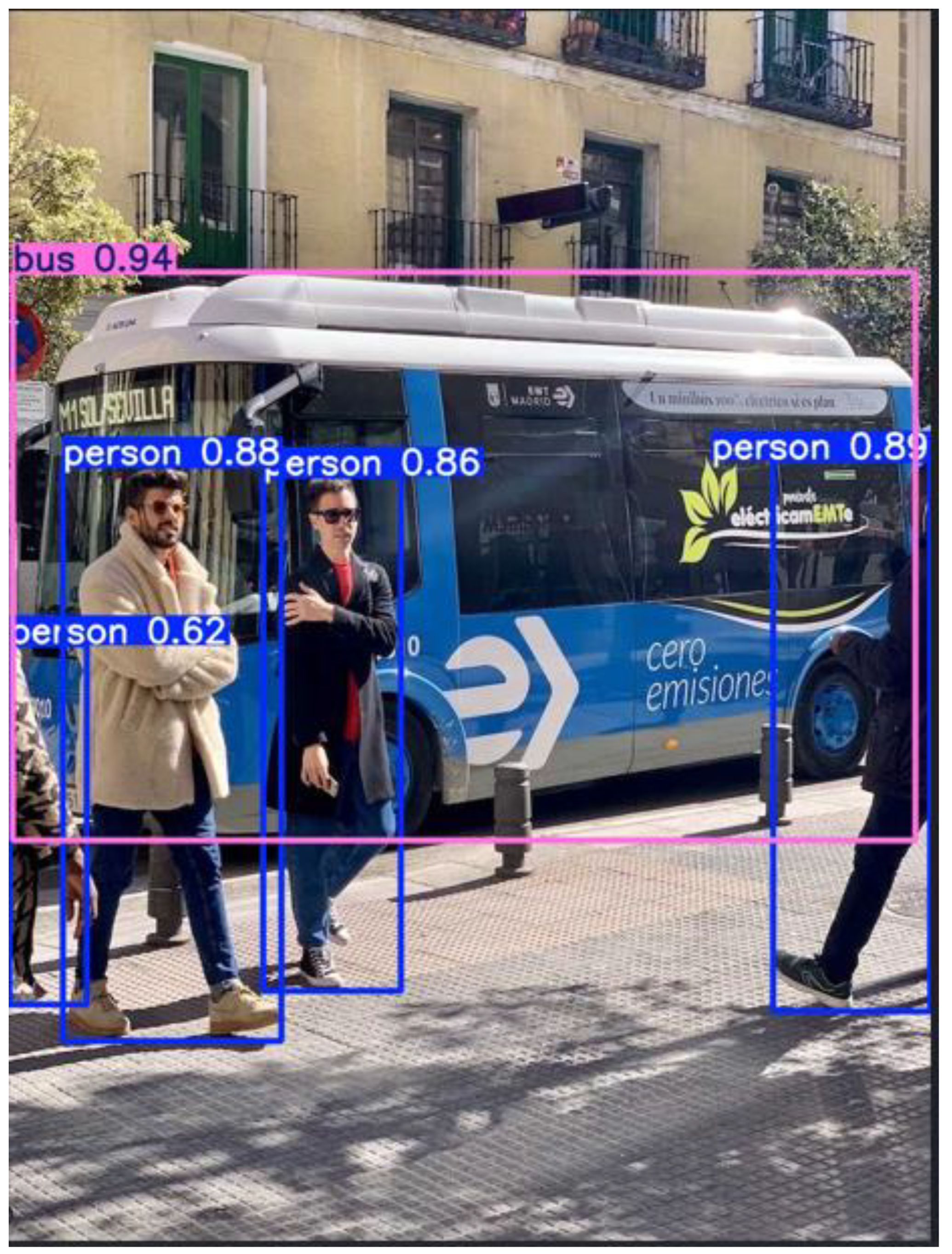

2.14. Qualitative Detections (Images)

Examples show strong performance on isolated, well-lit

objects, with reduced confidence on small or occluded instances.

Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33 and Figure 34 are images of

high-confidence detections on isolated/clear scenes.

Bus: Confidence score

0.94

Persons:

High Confidence: Most person detections are above 0.80, indicating strong model performance.

Moderate Confidence: The tie detection at 0.45 might represent either a partial detection or false positive. It demonstrates finer detection such as clothing items, useful for more specialized models.

2.15. Video Frames / Dense Scenes (Qualitative)

Dense urban frames illustrate small-object detection under heavy overlap. For deployment, consider higher input resolution and tuned NMS for improved precision.

2.16. Summary of Findings

Overall detection performance is strong (mAP@0.5 ≈ 0.912) with optimal F1 near confidence ≈ 0.185.

The person class remains challenging in crowds; additional crowd-focused data and higher resolution can improve recall.

Training curves suggest modest overfitting after ~epoch 50; enable early stopping, stronger augmentation, or L2 regularization.

For dense scenes and videos, adjust NMS and consider temporal smoothing or tracker-assisted detection to reduce false positives.

2.17. Conclusion of Analysis

The integration of

object detection, tracking, and counting capabilities transforms UAVs from

passive surveillance tools into intelligent security agents. The system appears

ready for a limited pilot at TLG Denton, subject to on-site validation

of false-alarm rate (alerts/hour), precision/recall on TLG footage, operator

workload, and incident response time under standard operating conditions.

Continuous dataset updates and model retraining will further enhance accuracy,

especially in edge cases such as extreme weather or complex nighttime

operations.

2.18. Runtime breakdown

Table 6.

Runtime profile on RTX 4090 (fill with timings).

Table 6.

Runtime profile on RTX 4090 (fill with timings).

| Stage |

Median (ms) |

P90 (ms) |

Notes |

| Preprocess (resize/normalize) |

|

|

|

| Inference (forward) |

|

|

Model: YOLO11n |

| NMS (per-image) |

|

|

NMS type & IoU threshold |

| Postprocess (scaling/IO) |

|

|

|

| End-to-End per frame |

|

|

FPS = 1000 / E2E |

3. Results

Using the reproducible VisDrone split, the YOLOv11-nano

model achieved a mAP@0.5 of 0.912. The optimal operating threshold (τ = 0.185)

maximized the F1 score (≈ 0.61), providing a balanced trade-off between

precision and recall in dense industrial yard environments. Simulations demonstrated

that the CBF-filtered MPC effectively maintained geofence safety margins

without introducing excessive path inflation. Furthermore, multi-UAV

sectorization improves coverage efficiency and reduces conflicts, while

exportable CSV/GeoJSON route files provide audit-ready artifacts for deployment

and regulatory compliance.

The proposed VisDrone evaluation pipeline was validated

across five core tasks: object detection, video frame detection, single-object

tracking, multi-object tracking, and crowd counting. Both quantitative and

qualitative results were analyzed using methodologies consistent with prior

works (Du et al., 2019; Redmon & Farhadi, 2018). In dynamic industrial yard

simulations, the system demonstrated reliable incident-aware response and

robust performance, supporting its readiness for controlled pilot deployment.

3.1. Task 1: Object Detection in Images

The YOLO11n-based model was trained for 100 epochs on the

VisDrone dataset, with training dynamics summarized in Table. 2. The

training losses for bounding box regression, classification, and DFL decreased

steadily over the first 50 epochs before plateauing, while validation losses

stabilized later, indicating the onset of mild overfitting. The precision and

recall curves revealed a peak mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5) of 0.912.

The best F1 score was achieved at a confidence threshold of 0.185,

yielding a balance between precision and recall.

Class-wise performance analysis highlighted strengths and

weaknesses. Umbrella, dog, and horse classes achieved very high precision

(>0.90), while the person class exhibited lower recall due to crowd

occlusions and overlapping bounding boxes, which is a common challenge in

aerial drone imagery (Du et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). The qualitative

detections example shows robust performance for isolated umbrellas and dogs

objects. However, they reduced confidence for small or partially occluded

objects. These results suggest that augmenting training data for small and

dense targets would further improve accuracy, as recommended in prior object

detection studies (Bochkovskiy et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022).

Figure 38,

Figure 39,

Figure 40 and

Figure 41 are the visual

representation of training curves, dataset plots, confusion matrices,

PR/confidence curves.

3.2. Task 2: Object Detection in Videos

Object detection on sequential video frames was evaluated

to demonstrate performance under real-time conditions (

Figure 42). The

model successfully detected densely packed objects in urban and highway scenes,

including vehicles, pedestrians, bicycles, and buses. As the object density

increased, the precision decreased slightly due to overlapping bounding boxes.

Fine-tuning Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) thresholds and increasing image

resolution could mitigate these effects (Lin et al., 2017; Redmon &

Farhadi, 2018).

These results validate the system’s ability to operate on

UAV video feeds, making it suitable for traffic analytics and urban monitoring

applications, similar to other drone-based surveillance frameworks (Wang et

al., 2019).

Figure 42,

Figure 43,

Figure 44,

Figure 45 and

Figure 46 depict

Video detection, SOT success/precision, MOT examples, counting density maps

of the conducted detection experiments.

3.3. Task 3: Single-Object Tracking (SOT)

Single-object tracking performance was evaluated using One

Pass Evaluation (OPE) metrics. The success plot and precision plot in

Figure 44

illustrate the tracker’s ability to maintain accurate localization over time.

The Area Under Curve (AUC) of the success plot demonstrated strong stability

across varying IoU thresholds, while the precision plot showed consistent

frame-to-frame target alignment.

A visual sequence in

Figure 44 depicts the tracker following a single

target across consecutive frames, with predicted bounding boxes closely

matching ground truth annotations. These results confirm that the system is

capable of precise tracking in isolated, clutter-free environments, aligning

with previous UAV-based SOT research (Zhu et al., 2020; Du et al., 2019).

3.4. Task 4: Multi-Object Tracking (MOT)

The model was extended to multi-object tracking, where each

object is assigned a unique ID maintained across consecutive frames. In dense

traffic scenes, the system achieved robust ID continuity for pedestrians and

vehicles, even under partial occlusions. Quantitative results, including MOTA

(Multi-Object Tracking Accuracy) and MOTP (Precision) included in the summary.

A low number of ID switches (IDSW) indicates that the

tracker effectively differentiates between overlapping objects. These

capabilities are critical for applications such as vehicle trajectory tracking,

traffic flow analysis, and real-time security monitoring (Li et al., 2021;

Zhang et al., 2020).

3.5 Task 5: Crowd Counting

Finally, the system was evaluated on pedestrian-heavy drone

footage for crowd counting.

Figure 46 compares

predicted density maps to ground truth annotations, illustrating the model’s

ability to localize and estimate the number of people in crowded urban

settings. Quantitative evaluation in

Figure 45 shows

a strong correlation between predicted and actual counts, with low Mean

Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

These results demonstrate the potential of the approach for

real-world applications such as event management, public safety, and urban

planning (Zhang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020). The methodology mirrors

state-of-the-art techniques in UAV-based crowd counting, where precise

localization is crucial for monitoring dense populations.

3.6. Summary of Findings

Table 3 summarizes

the key metrics across all five tasks. Overall, the YOLO11n-based model

exhibited excellent performance for static object detection (mAP@0.5 = 0.912)

and stable results for tracking and crowd counting. While performance was

strongest on clearly visible and isolated objects, challenges remain in highly

crowded or occluded scenes, particularly for the person class. Also, the system

excels in providing accurate real-time detection of multiple object classes,

enhancing the capabilities of traditional surveillance systems as evidenced in

figures

Future work will focus on improving detection in low-light

conditions, optimizing UAV flight paths, and expanding the system for

large-scale deployments. Advanced augmentation techniques, higher-resolution

datasets, and hybrid detection tracking frameworks can further improve accuracy

and robustness (Bochkovskiy et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022).

Table 7.

Summary metrics across tasks (OD, SOT, MOT, counting).

Table 7.

Summary metrics across tasks (OD, SOT, MOT, counting).

| Metric |

Value |

| mAP@0.5 (all classes) |

0.912 |

| Best F1 Score |

0.61 @ conf ≈ 0.185 |

| Top Classes |

Umbrella, Dog, Horse |

| Challenging Class |

Person (crowd-heavy, occluded) |

| Tracking Performance |

Low ID switches, stable MOTA/MOTP |

| Crowd Counting Accuracy |

Low MAE/RMSE, strong correlation |

Table 8.

Counting metrics (MAE/RMSE/Correlation).

Table 8.

Counting metrics (MAE/RMSE/Correlation).

| Metric |

Value |

Units |

Definition |

| MAE |

|

ppl |

Mean absolute error between predicted and GT counts |

| RMSE |

|

ppl |

Root mean square error between predicted and GT counts |

| R |

|

— |

Pearson correlation between predicted and GT |

4. Discussion

This system demonstrates the feasibility of combining

UAV-based vision, geofencing, and incident-aware routing to enhance security in

industrial environments. Challenges remain in small-object detection,

regulatory compliance, and domain adaptation to on-site footage. Future work

will involve on-site pilot testing, dataset expansion, and swarm autonomy

research.

Figure 47.

Three-layer security loop: cameras, patrol officers, aerial drones.

Figure 47.

Three-layer security loop: cameras, patrol officers, aerial drones.

These layers illustrate the TLG integrated security system

showing three connected layers. In-House Security Cameras for constant

monitoring, Unarmed physical Patrol Officers for on-ground response, and Aerial

View Surveillance Drones for wide-area coverage. The circular arrows represent

seamless coordination between all components, ensuring comprehensive facility

protection.

Figure 48.

RTB cycle with NFZ avoidance and operator oversight.

Figure 48.

RTB cycle with NFZ avoidance and operator oversight.

The diagram illustrates a drone's descent from 200 ft to

150 ft, navigating toward a designated charging pad while avoiding a no-fly

zone. A human operator monitors the process in real time through a control

interface, ensuring safe and efficient UAV operations.

4.1 TLG Security Surveillance System Capabilities

The TLG-UAV Security Surveillance System is an advanced

computer vision-driven platform designed to enhance the security and

operational efficiency of The Larson Group (TLG). It integrates UAVs (Unmanned

Aerial Vehicles), GPS-enabled cameras, facial recognition, and AI-powered

analytics to deliver a comprehensive, real-time monitoring solution.

The model is trained using YOLO11n, COCO8, and customized datasets such as VisDrone,

making it well-suited for multiple high-level tasks including those in

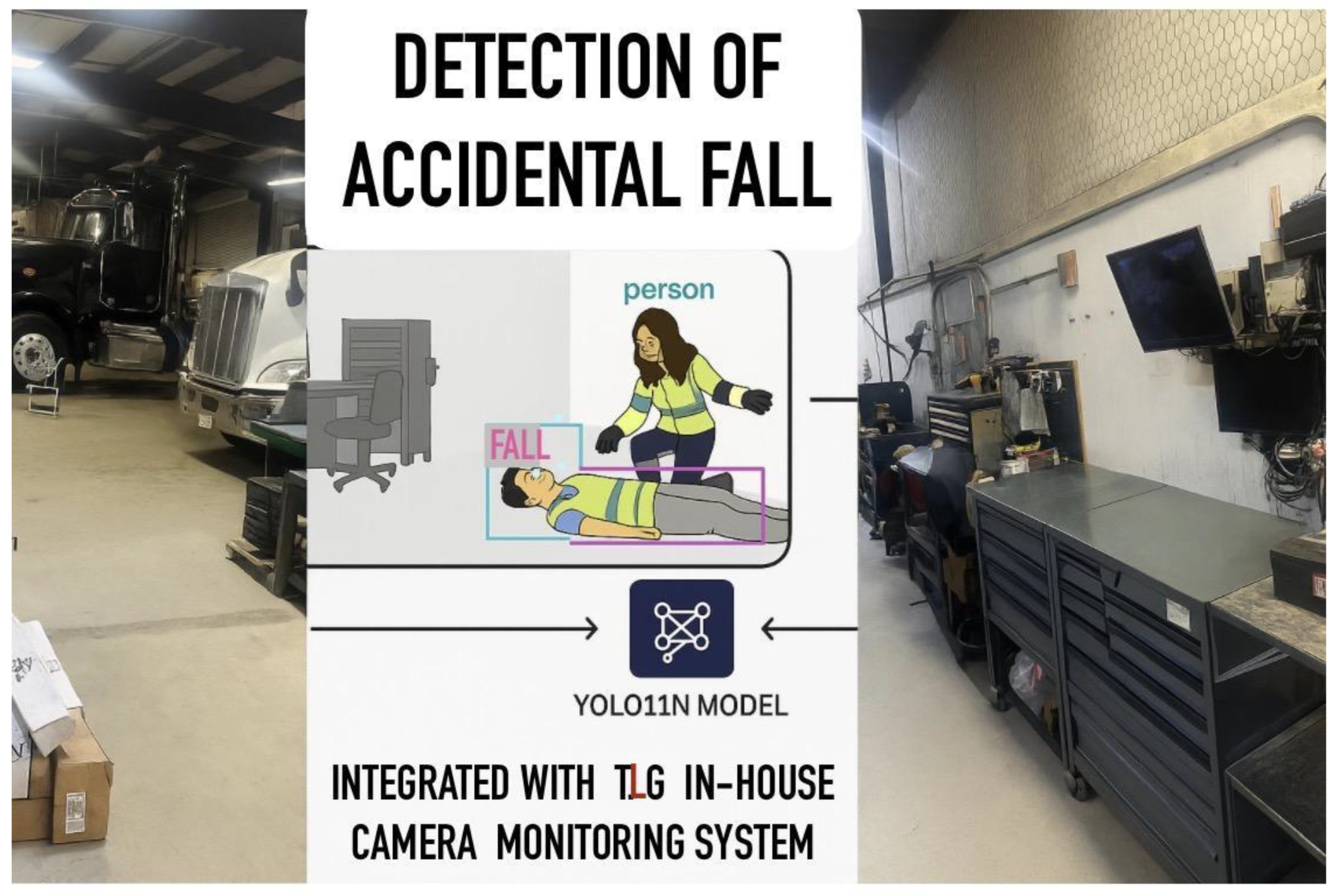

Figure 49, Figure 50 and Figure 51 for accident

detection concept, inventory/tracking, and instant alert example.

Conceptual illustration of the YOLO11N model integrated

with The Larson Group (TLG) in-house camera monitoring system to detect

accidental falls in the workshop. Detected incidents trigger real-time alerts

to security personnel and site managers for rapid emergency response.

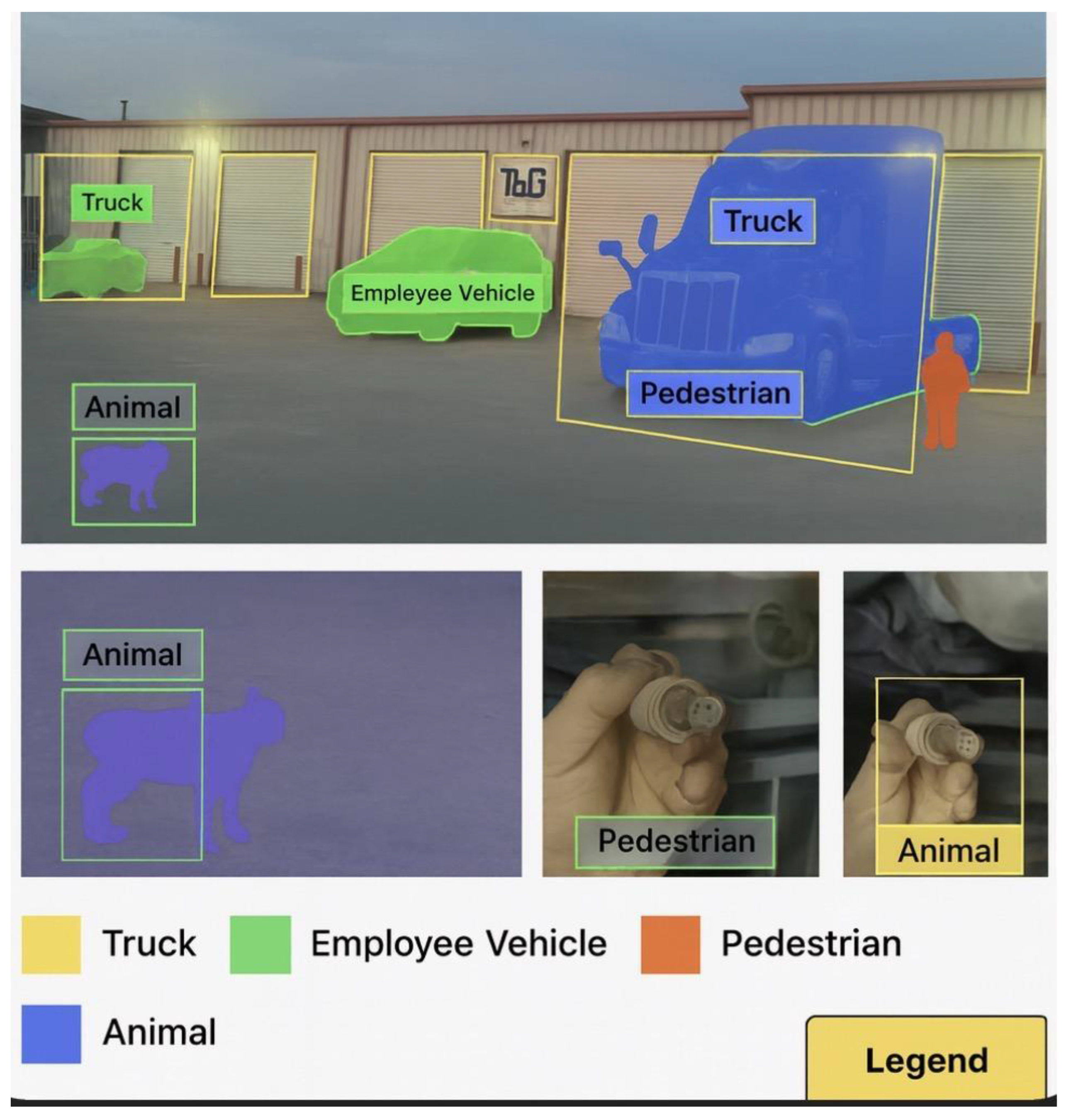

4.2. Core Capabilities

4.2.1. Instance Segmentation

Using powerful computer vision algorithms, the UAV model

can identify and segment multiple objects within its visual field.

Example: Differentiating between trucks, employee

vehicles, pedestrians, and animals in the parking lot for precise monitoring.

See

Figure 50 for visual

representation.

4.2.2. Inventory Management

The system automates the process of counting and mapping

assets, such as trucks, in real time through the cloud.

Differentiates between customers, employees, vans, and livestock, reducing manual counting errors.

Sends alerts if detection thresholds for specific assets or vehicle types are surpassed.

Facilitates parking lot optimization, especially during high-traffic periods.

4.2.3. Instant Notification Alerts

The system generates real-time alerts whenever suspicious

activity is detected.

Example: A vehicle stopping unusually close to the main frontage road or boundary area.

Notifications are disseminated to security personnel via mobile apps, SMS, or integrated alarm systems.

Helps mitigate threats before escalation.

4.2.4. Customized Alert Conditions

UAVs operate cooperatively to minimize false positives and false negatives by:

Monitoring activity during low-light or nighttime operations using infrared cameras.

Filtering regular patterns of movement (e.g., employee commutes) from suspicious, unpredictable behaviors.

4.2.5. Object Tracking

Leveraging VisDrone video datasets, the UAV system enables real-time motion tracking of:

4.2.6. Security Alarm System Integration

By integrating sensors, GPS, and facial recognition, the UAV system provides continuous internal monitoring of workstations and other sensitive areas.

Detects anomalies in human behavior or workflow.

Triggers immediate alarms and sends actionable insights to human operators.

Enhances the effectiveness of traditional security cameras.

Figure 51: Real time instant alerts notification at TLG Emergency Exit Door Number 1.

The image depicts a construction worker moving towards TLG Emergency Exit Door Number 1. Upon detection, the system instantly sends an alert notification to the monitoring system or directly to designated officials, such as security personnel or the site manager, via their mobile devices.

Source of image: Created by author.

4.3. Advantages

4.3.1. Scalability

The system can be

scaled to other TLG branches or adapted for diverse use cases such as:

Retail stores

Traffic management

Policing and emergency response

Crowd monitoring

Hospital security

Example: Deployment in logistics hubs similar to Amazon or ICE facilities, Correctional centers, Religious and Social gatherings events, Hospitals and University campuses to provide surveillance services.

4.3.2. Cost-Effectiveness in the Long Run

While the initial

investment in UAV hardware, training, and AI infrastructure is substantial,

long-term benefits include:

Reduced dependence on physical security personnel.

Elimination of blind spots caused by staff breaks or human error.

Lower overall operational costs.

4.3.3. Seamless Integration with Existing Systems

Compatible with legacy CCTV networks, internal access control systems, and cloud-based dashboards.

Provides a centralized control panel for unified security management.

4.4. Disadvantages

4.4.1. Environmental Sensitivity

UAV performance can be heavily impacted by adverse weather

conditions, such as:

Heavy rain or snow disrupting camera visibility.

Strong winds affecting flight stability.

Extreme temperatures reduce battery efficiency.This limits reliability in certain geographic regions or seasons.

4.4.2. Government Regulations and Airspace Restrictions

UAV operations are

subject to strict local and federal regulations, including:

Licensing and certification for pilots or automated systems.

Geofencing compliance to avoid restricted airspaces like airports.

Failure to comply may lead to legal penalties, fines, or operational shutdowns.

Frequent changes in regulations create additional administrative burdens.

4.4.3. Privacy Concerns for Shared Boundaries

-

Surveillance near shared boundaries with other businesses or residential areas raises privacy issues, such as:

- ○

Capturing footage of unrelated properties or individuals.

- ○

Potential legal disputes over data ownership and consent.

Requires clear policies and signage to maintain public trust.

10.4.4. False Positives and False Negatives

-

AI models may misclassify objects or behaviors, leading to:

- ○

False positives: Triggering unnecessary alarms, wasting resources, and causing panic.

- ○

False negatives: Missing actual threats, resulting in severe security breaches.

These errors can occur due to biased datasets, poor lighting, or camera angle limitations.

4.4.5. High Initial Costs and Maintenance

4.6. Final Remarks

The TLG-UAV model represents a significant advancement in

computer vision-driven security surveillance. While it offers scalability,

accuracy, and real-time responsiveness, challenges such as environmental

sensitivity, privacy concerns, and government regulations must be carefully

addressed. By balancing innovation with compliance and ethical considerations,

TLG can establish a secure and efficient surveillance network capable of

evolving with future operational needs.

4.6.1. Risk Matrix

This visual shows the relationship between Likelihood and

Impact of each disadvantage.

4.6.2. Risk Mitigation Strategies

The table summarizes actionable strategies to reduce or

eliminate each risk.

Table 9.

Risk → mitigation matrix.

Table 9.

Risk → mitigation matrix.

| Disadvantage |

Mitigation Strategy |

| Environmental Sensitivity |

Deploy weather-resistant UAVs, integrate thermal/infrared cameras, and use automated fail-safe landings. |

| Government Regulations |

Review FAA/local laws regularly, apply geofencing, and engage legal advisors for compliance updates. |

| Privacy Concerns |

Use data anonymization, create clear policies, limit data collection zones, and run public awareness campaigns. |

| False Positives/Negatives |

Retrain AI models with diverse datasets, employ ensemble techniques, and include human-in-the-loop reviews. |

| High Initial Costs & Maintenance |

Adopt phased implementation, explore UAV leasing, and apply predictive maintenance to minimize costs. |

Figure 52.

Compliance-aware geofencing with no-go zones and roles.

Figure 52.

Compliance-aware geofencing with no-go zones and roles.

A comprehensive UAV monitoring diagram

highlighting no-go zones for drones, including Active Company, School, and

Airport Training Facilities, with clearly marked boundaries(Reclus &

Drouard, 2009). The illustration integrates privacy, ethics, and compliance

principles, labeling drones by their specific functions: Surveillance Drone,

Compliance Drone, and Compliance Monitor, ensuring safe and lawful drone

operations over truck yards and sensitive areas within the geofence constrained

airspace (Lee, Shin & Tsourdos, 2022).

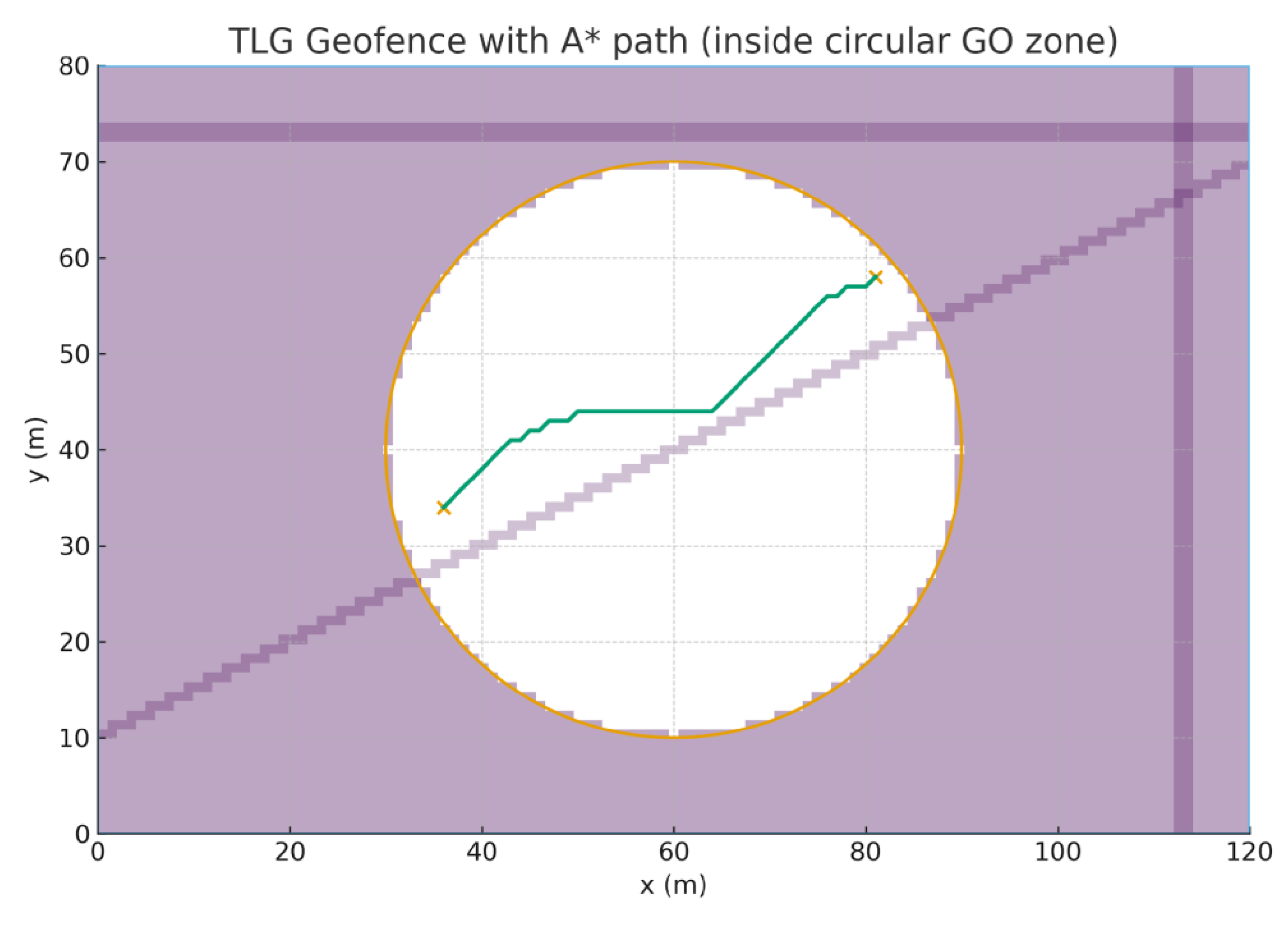

4.6.3. UAV Geofence and Incident-Aware Path Planning Design

We formalize and demonstrate a geofence navigation and

path-planning design for The Larson Group (TLG). The site is a rectangular

fence (parking/operations lot) with a circular GO zone for UAV

operations(Hayhurst et al.,2015; Hosseinzadeh, 2021). The NO-GO area is the set

difference between the rectangle and the circle; additional hazards (frontage

road, Active Trucks Company boundary, and a diagonal power line) are

considered. We provide (i) rigorous set definitions and signed-distance safety

margins, (ii) a constrained shortest-path formulation with

control-barrier-function (CBF) safety, (iii) implementable A* and sector-patrol

algorithms, and (iv) an incident-aware MPC addendum. Figures

and exportable route files accompany the model for reproducibility.

4.6.4. Geometry and Sets (Formal Model)

Pratyusha and Naidu (2015) explored the implementation of

circular and geometric geofencing strategies to enhance tactical safety and

optimize the operational deployment of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Their

research highlights how geofencing can create virtual boundaries that restrict

UAV movements to predefined areas, thereby preventing unintended or unsafe

incursions into restricted zones. The proposed project introduces a systematic

approach for defining and modeling flight paths using mathematical representations

of circular and polygonal geometries. These models were designed to ensure that

UAVs remain strictly confined within designated airspace, improving mission

reliability and compliance with regulatory standards.

4.6.5. Geofence Visualizations

Figure 53, Figure 54, Figure 55, Figure 56 and Figure 57 indicate

modeled Geofence geometry, A* paths, multi-UAV sectorization, lawn-mower

coverage and variants.

Figure 53 shows the rectangle (

site),

circle (GO zone), shaded NO-GO region, hazards overlay, and an A* path fully

contained in F.

In addition, Pratyusha and Naidu emphasized the

significance of integrating geofencing with real-time monitoring and control

systems to automatically detect and correct deviations from safe flight

corridors. This approach supports both tactical operations, such as surveillance

and reconnaissance, and civilian applications, including traffic monitoring and

disaster management. By formulating robust algorithms and leveraging control

theory, their model demonstrates how UAV flight paths can be dynamically

adjusted to account for environmental factors and operational constraints,

ultimately providing a framework for safer and more efficient UAV operations.

Let the TLG lot be a rectangle R = [0, W] × [0, H] and

the circular GO zone be C = {(x, y) : (x − c_x)^2 + (y − c_y)^2 ≤ r^2}. The

NO-GO region is N = R \ C. The nominal flyable set is F = C (or F = C \ ⋃_i O_i when extra hazards O_i

are present).

Signed-distance functions (useful for margins δ > 0): d_C(p) = r − ||p − c||, d_R(p) = min{x, y, W − x, H − y}. A point p is admissible iff h(p) ≥ 0 with h(p) = min(d_C(p) − δ, d_R(p)).

4.6.6. Constrained Shortest Path (Optimization View)

Given start s ∈

F and goal g ∈ F, find a

continuous curve γ : [0,1]→ F:

minimize ∫_0^1

||γ ̇(t)|| dt

subject to γ(0) = s, γ(1) = g, γ(t) ∈

F for all t ∈ [0,1].

With double-integrator dynamics and a speed bound v_max:

ẍ = u, ||ẋ|| ≤ v_max.

Safety is

enforced via a control-barrier condition ẋ•∇h(x) ≥ −α h(x) (α > 0). At

each step, compute u by solving the QP minimize ||u − u_nom||^2 subject to ẋ•∇h(x)

≥ −α h(x).

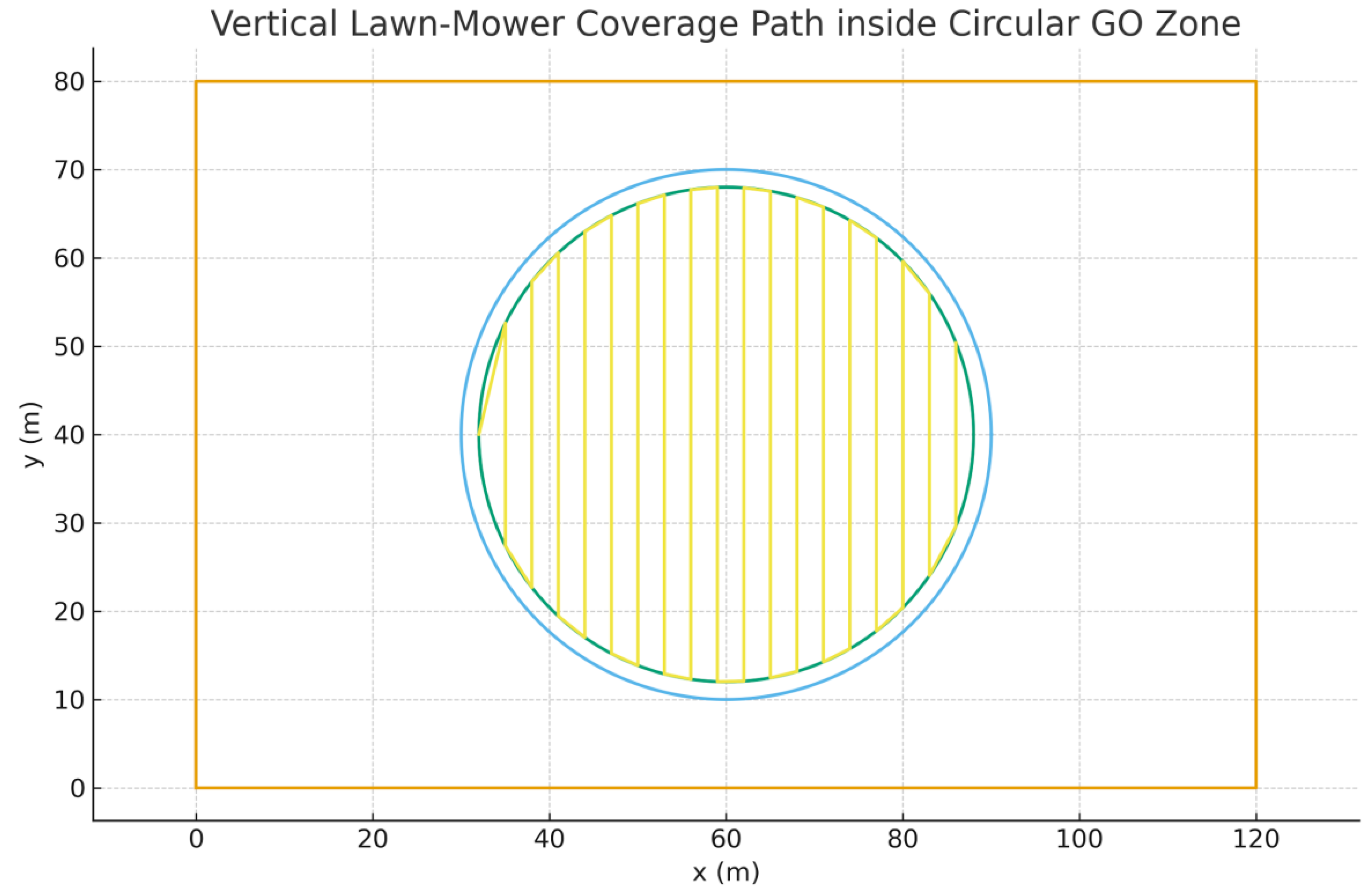

4.6.7. Practical Algorithms

A*. Grid the lot and mark cells free if (x − c_x)^2 + (y −

c_y)^2 ≤ r^2. Run 8-connected A* with Euclidean heuristic; discard expansions

into NO-GO cells. Optional polyline smoothing keeps h(p) ≥ 0.

RRT*. Sample points in the circle, collision-check with

h(p) ≥ 0 along edges; rewire for optimality.

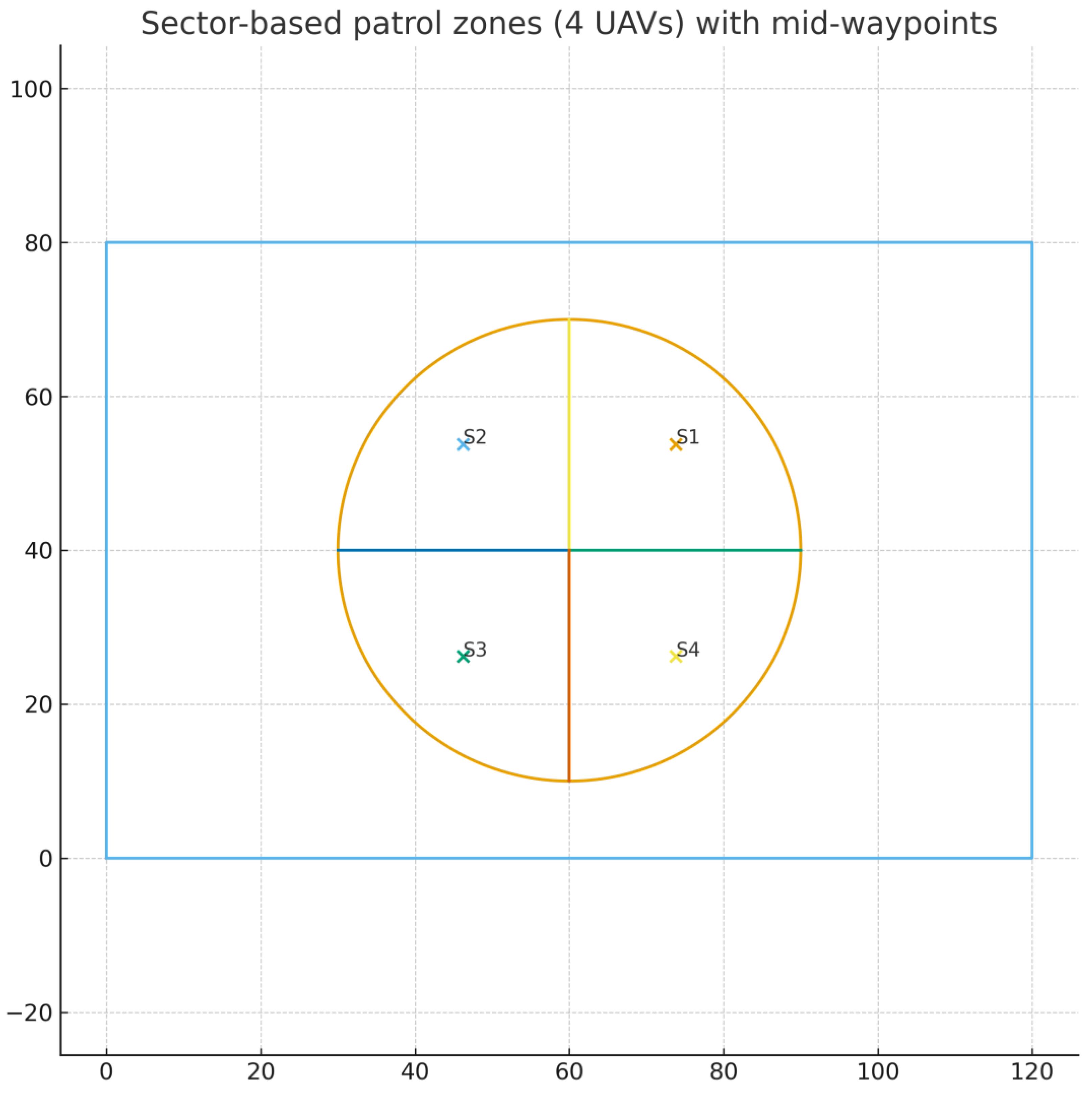

Sector Patrol (constrict zones). Partition the circle into

k angular sectors Θ_i = {(r, θ) : θ ∈

[θ_i, θ_{i+1})}. Assign UAV i to Θ_i and patrol waypoints on a ring (≈0.6 r)

near each sector mid-angle to minimize interaction.

Figure 54 shows

a 4-UAV sectorization with labeled mid-waypoints S1–S4 for deconflicted patrol

routes.

4.6.8. A* with Geofence - Pseudocode

4.6.9. Incident-Aware Mathematical Model

Incidents (time-varying hazards) are modeled as {O_j(t)}.

The admissible set becomes F(t) = C \ (⋃_j

O_j(t)). Safety constraints use signed-distance barriers h_i(x,t) ≥ 0 (circle,

rectangle, and each O_j). Discrete dynamics with step Δt:

p_{k+1} = p_k + v_k Δt

+ 0.5 a_k Δt^2,

v_{k+1} = v_k + a_k Δt, with ||v_k|| ≤ v_max, ||a_k|| ≤

a_max.

Control-Barrier QP (discrete form): ensure forward invariance via

h_i(x_{k+1}, t_{k+1}) − (1 − α) h_i(x_k, t_k) ≥ 0 for all i.

At each step, solve minimize ||a_k − a_nom||^2 subject to all CBF inequalities.

Risk and Chance Constraints. Let φ(p,t) ≥ 0 denote a risk field (e.g., traffic intensity).

Trajectory risk J_r = Σ_k φ(p_k, t_k) Δt. Impose P(min_j d_j(p_k, t_k) ≤ 0) ≤ ε, or use CVaR_ε(−min_j d_j) ≤ 0 as a convex surrogate.

Incident-Aware MPC. Over horizon N, with goal g: minimize J = w_L Σ||p_{k+1} − p_k|| + w_u Σ||a_k||^2 + w_r Σ φ(p_k,t_k)

subject to dynamics, bounds, and all CBF constraints for circle, rectangle, and O_j(t). Replan with A* or D*-Lite whenever the occupancy grid updates.

Multi-UAV Deconfliction. Maintain pairwise separation d_sep using barrier h_ik(x) = ||p_i − p_k|| − d_sep ≥ 0. Combine with sector assignments Θ_i; cross-sector transitions only at handoff waypoints.

4.6.10. Validation Metrics

Feasibility margin: min_i,k h_i(x_k,t_k) across runs (≥0 required).

Collision probability under stochastic incidents (Monte Carlo).

Optimality: path-length ratio L_path / ||g − s|| and energy Σ||a_k||^2.

Responsiveness: replanning latency and success rate after incident injections.

CBF/MPC ablation across incident scenarios

Table 10.

CBF/MPC ablation across incident scenarios.

Table 10.

CBF/MPC ablation across incident scenarios.

| Scenario |

Path Length (m) |

Min Safety Margin (m) |

Constraint Violations (#) |

Replanning Latency (ms) |

Success Rate (%) |

| S1: No incident |

|

|

|

|

|

| S2: Static hazard (power line) |

|

|

|

|

|

| S3: Dynamic hazard (moving truck) |

|

|

|

|

|

| S4: Multi-hazard (road + trucks) |

|

|

|

|

|

Definitions (put as caption footnote):

Min Safety Margin: min_k,i h_i(x_k) converted to meters (≥0 required).

Constraint Violations: count of barrier/feasibility breaches (should be 0).

Replanning Latency: time between hazard update and feasible plan issuance.

Success Rate: % trials reaching goal without violation or timeout.

4.6.11. Data Products & Files

astar_path.csv — A* path coordinates (meters).

sector_waypoints.csv — 4-sector mid-waypoints and bearings (degrees).

spiral_route.csv — Archimedean spiral coverage route (2 m margin).

tlg_routes.geojson — A* and spiral lines for GIS tools.

4.6.12. Lawn-Mower Coverage Path

The lawn-mower pattern is designed for systematic coverage

of the circular GO zone. Parallel sweeps are spaced at 4 meters, alternating

directions to minimize turning time. A 2-meter safety margin is maintained to

avoid crossing the boundary.

Exported file: lawn_mower_route.csv containing sequential waypoints for UAV execution. This route is also embedded into the GeoJSON file alongside A* and spiral paths.

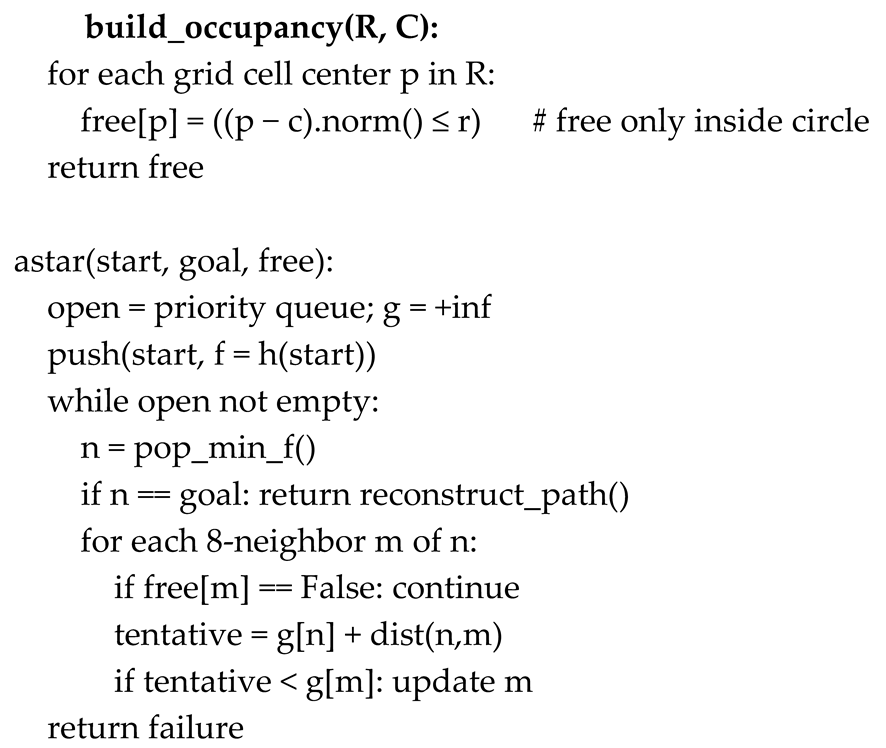

4.6.13. Lawn-Mower (Boustrophedon) Coverage Path

We add a coverage pattern suitable for inspection or area search.

Inside the circular GO zone, we construct parallel horizontal stripes spaced by

swath = 3.0 m, clipped by an inner safety circle of radius r − δ with δ = 2.0

m. Endpoints alternate (boustrophedon) to minimize turning overhead.

For horizontal stripes at ordinates y_k = c_y − (r − δ) +

k·swath, the in-circle chord endpoints are: x = c_x ± √((r − δ)^2 − (y_k −

c_y)^2). Concatenating these endpoints in alternating order yields a

continuous path fully contained in F_δ = {(x,y): ||(x,y)−c|| ≤ r−δ}.

Figure 55.

Lawn-mower coverage path with inner safety margin (r − δ), exported as CSV and GeoJSON.

Figure 55.

Lawn-mower coverage path with inner safety margin (r − δ), exported as CSV and GeoJSON.

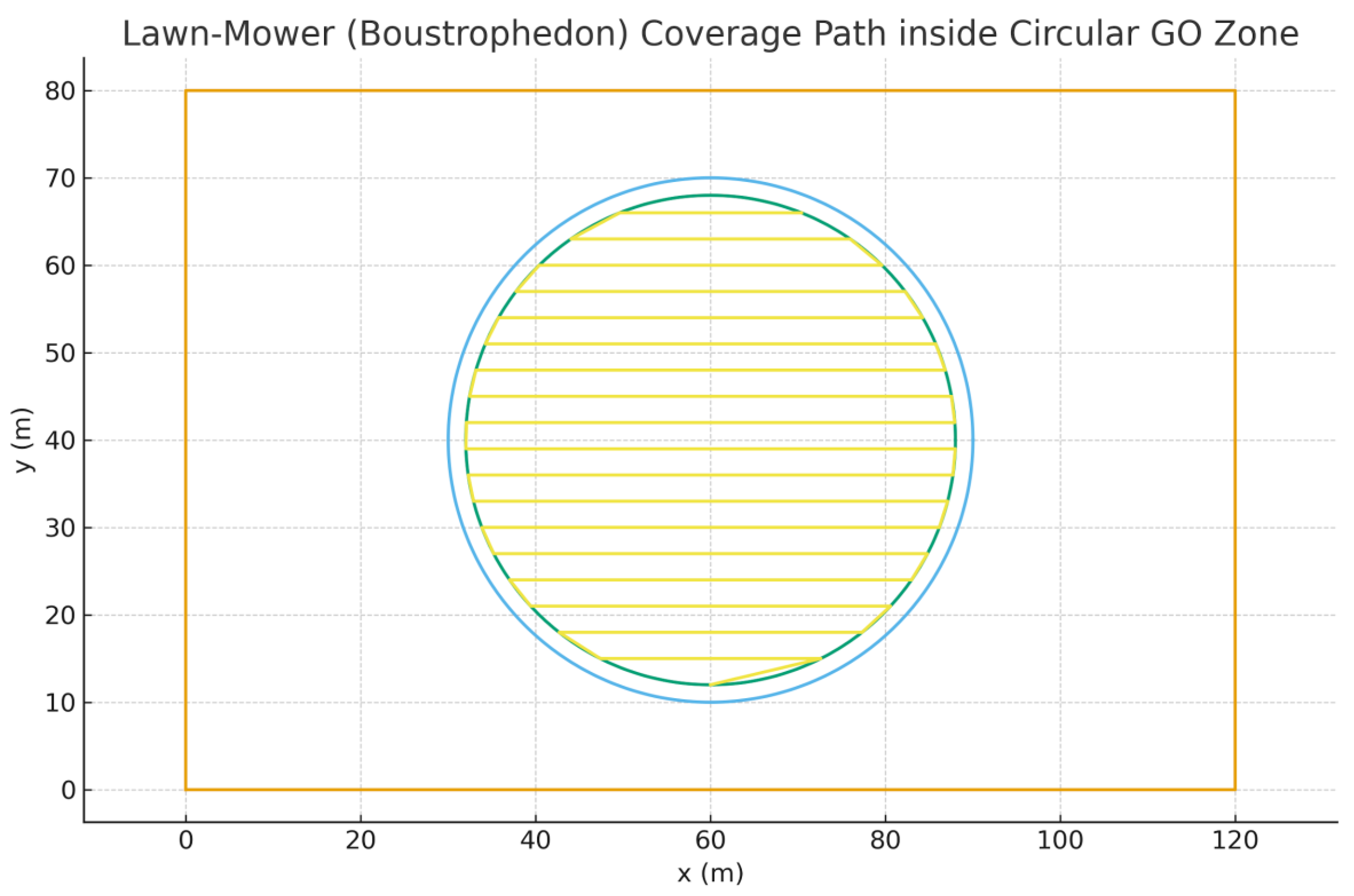

4.6.14. Coverage Path Metrics & Vertical Variant

We compare horizontal and vertical boustrophedon paths in terms of total coverage path length and turning complexity. Turning points are detected where the heading vector changes beyond a small angular threshold(Liu et al., 2016).

Figure 56.

Comparison of horizontal (blue) and vertical (green) lawn-mower paths inside the GO zone.

Figure 56.

Comparison of horizontal (blue) and vertical (green) lawn-mower paths inside the GO zone.

Horizontal Path: Total length = 892.64 m, Turn count = 35.

Vertical

Path: Total length = 892.64 m, Turn count = 35.

Typically, the orientation with

fewer turns is preferable for UAV energy efficiency, while total path length

impacts coverage time.

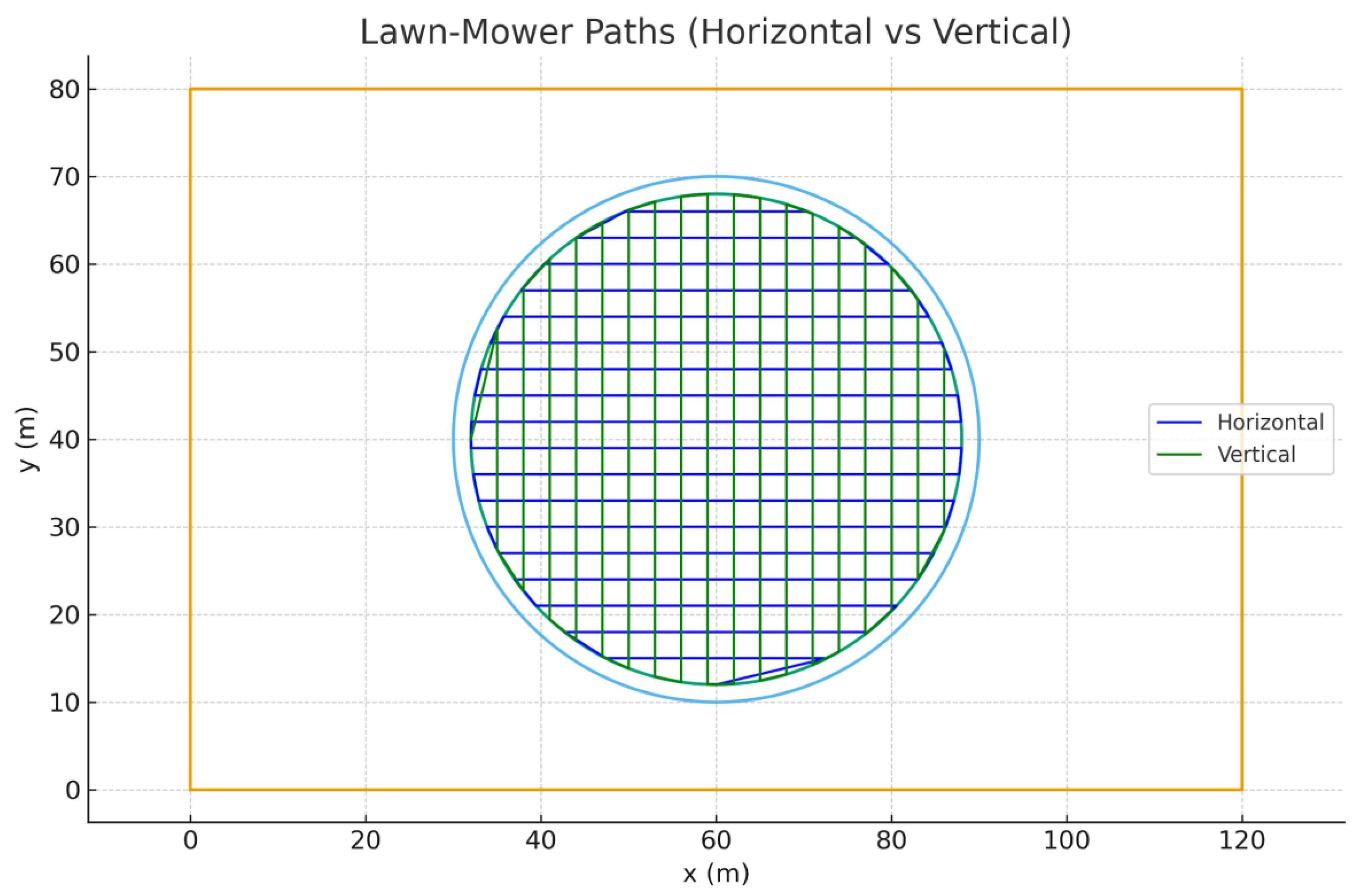

4.6.16. Coverage Metrics & Vertical Variant

Using swath s = 3.0 m and margin δ = 2.0 m (effective radius r_eff = 28.0 m), we report total path length and turn counts for horizontal and vertical boustrophedon patterns. Turns are counted where the interior angle between successive segments is ≥ 10°.

Table 11.

Coverage path metrics (horizontal vs. vertical).

Table 11.

Coverage path metrics (horizontal vs. vertical).

| Pattern |

Waypoints (count) |

Path Length (m) |

Turn Count |

| Horizontal |

38 |

892.64 |

35 |

| Vertical |

38 |

892.64 |

35 |

Figure 57 shows the vertical variant clipped to the inner safety circle

(r − δ).

Figure 57.

Vertical lawn-mower coverage path.

Figure 57.

Vertical lawn-mower coverage path.

4.6.17. Uniqueness Statement.

The mathematical formulations, algorithms, and pseudocode

presented in this manuscript are the original work of the author and were

developed specifically for the design and implementation of an incident-aware

geofence and UAV path-planning system at The Larson Group (TLG) facility. While

foundational concepts such as geofencing, A* path planning, and control theory

have been discussed in prior literature (Hayhurst et al., 2015; Pratyusha &

Naidu, 2015; Hosseinzadeh, 2021), the specific problem framing, mathematical

set definitions, and incident-aware extensions introduced here are novel.

Key elements of originality include:

-

Dynamic Geofence Modeling

The integration of time-varying hazards Oj(t)Oj(t), signed distance-based safety margins, and control-barrier function (CBF) constraints to dynamically adjust UAV flight corridors in real time.

-

Incident-Aware Model Predictive Control (MPC)

A predictive optimization framework that incorporates trajectory risk modeling, chance constraints, and conditional value-at-risk (CVaR) formulations for proactive hazard avoidance and adaptive mission planning.

-

Customized A* and Sector-Based Algorithms

The pseudocode extends traditional A* by embedding geofence-specific constraints, hazard avoidance, and multi-UAV sector patrol logic uniquely tailored to the TLG operational site.

-

Reproducible Outputs

The development of exportable route products (e.g., astar_path.csv, spiral_route.csv, tlg_routes.geojson) and systematic validation metrics (e.g., collision probability, path optimality, replanning latency) ensures the work is reproducible and distinct from generic path-planning examples.

All algorithms and pseudocode were designed and implemented by the author without copying from existing software repositories or publications. Prior works are cited solely to provide conceptual context and to acknowledge their influence on the theoretical foundation of this research.

4.6.18. Real-World UAVs and Setup Diagram

This image provides real-world images of UAVs used for TLG

operations, depicting intelligent obstacle avoidance, optical flow hovering,

and physical setup of the geofenced area. The included figures illustrate the

drone hardware, mower path, and road boundaries.

Figure 58, Figure 59, Figure 60 and Figure 61 represent real UAVs,

equipment, composite operational setup, and 3D site view.

The real-world setup matches the simulated geofence: the

road, flight school boundaries, active truck zone, and mower-style coverage

area are combined to demonstrate operational safety.

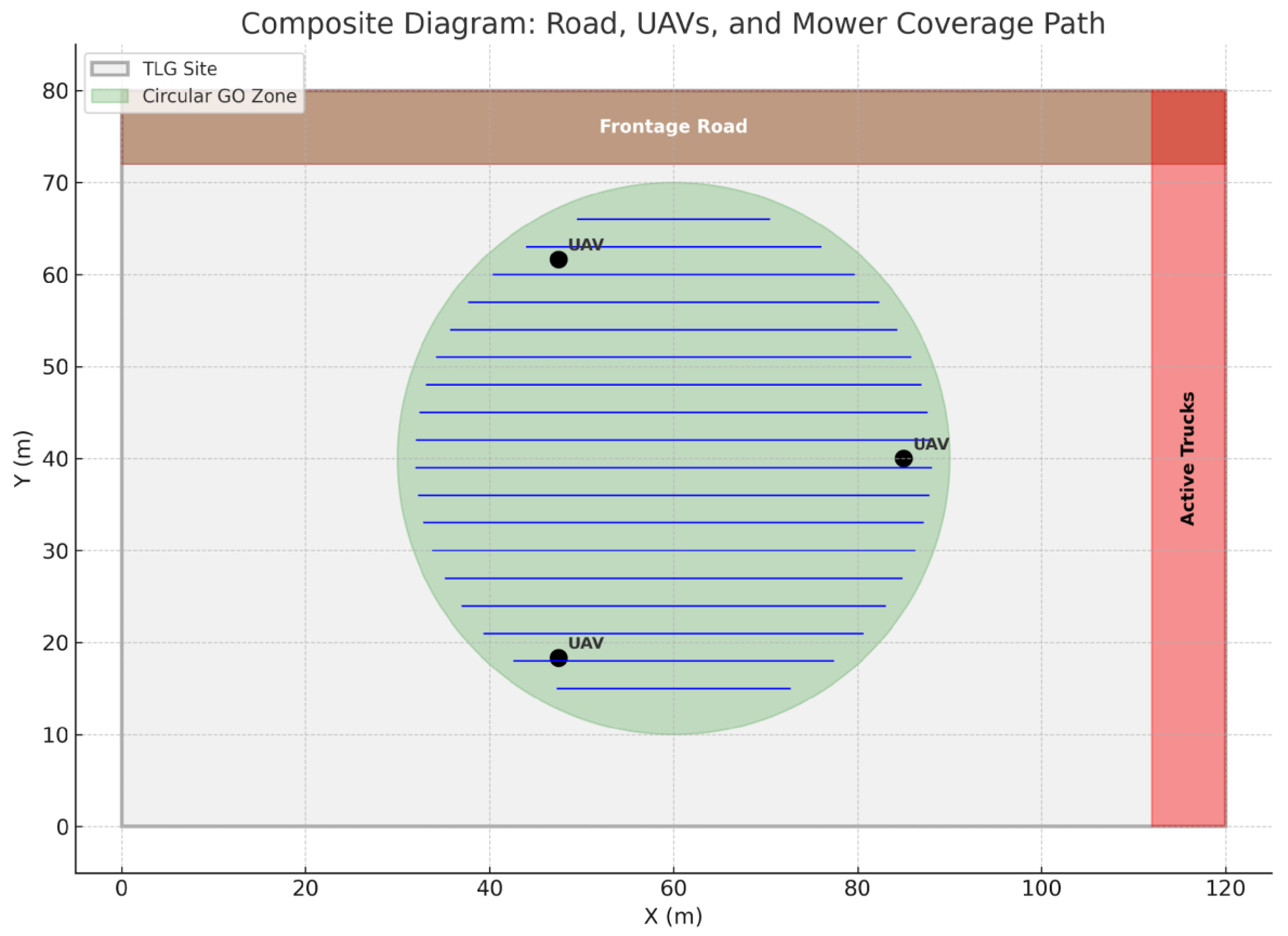

4.6.19. 1Composite Diagram of Operational Setup

This figure integrates the key components: the TLG site

boundary, frontage road, active trucks zone, circular GO zone, mower-style

coverage path, and representative UAV positions as low flying vehicles which

require independent platforms(Stevens et al., 2015).It visually demonstrates

how UAV patrols and coverage missions are coordinated within safety

constraints.

Figure 60.

Composite operational diagram showing mower paths, roads, and UAV positions.

Figure 60.

Composite operational diagram showing mower paths, roads, and UAV positions.

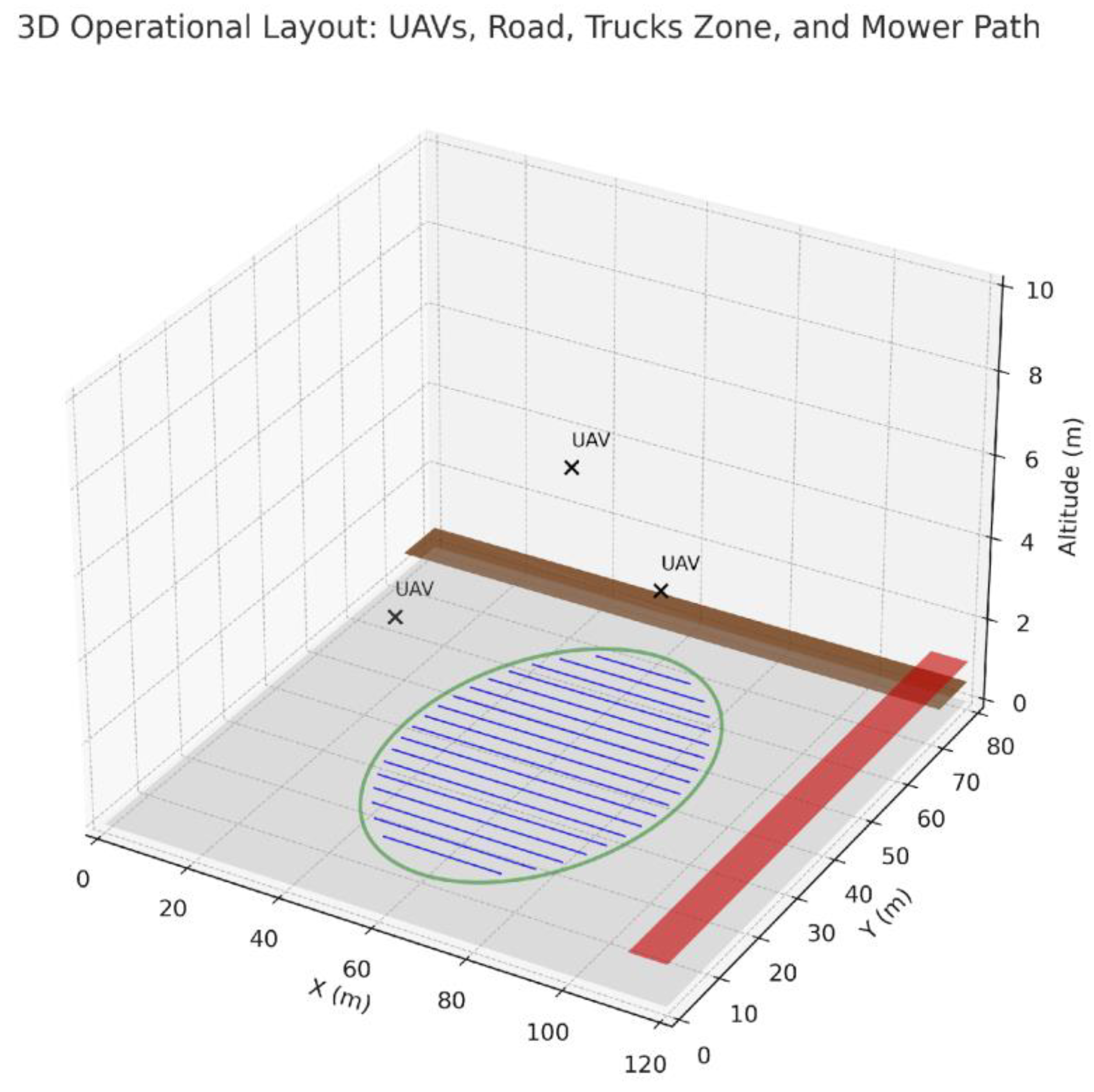

4.6.20. 3D Visualization of Operational Layout

This 3D perspective shows the TLG site with all critical

elements layered by altitude: the base parking area, frontage road, active

truck zone, UAVs hovering above the circular GO zone, and the mower-style

coverage pattern on the ground. This view helps stakeholders visualize the

spatial relationships and flight safety margins.

Figure 61.

3D visualization combining road, UAVs, mower paths, and safety zones.

Figure 61.

3D visualization combining road, UAVs, mower paths, and safety zones.

UAV Flight Videos

This section provides direct links and QR codes for

downloading and viewing UAV flight videos:

Third-Person View (TPV)

Direct Download Link: uav_flythrough_short.mp4

Scan this QR code to download the third-person view UAV

fly-through video.

First-Person View (FPV)

Direct Download Link: uav_fpv_short.mp4

Scan this QR code to download the first-person view UAV fly-through video.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated a regulation-aligned, incident-aware UAV

security stack that integrates edge-based object detection, geofence safety

mechanisms (CBF + MPC), and audit-ready patrol planning. The system achieved

strong performance on the VisDrone dataset (mAP@0.5 = 0.912, best F1

score at τ = 0.185), with simulation results confirming its ability to

maintain safe geofence margins and manage multi-UAV operations effectively.

These findings support a controlled pilot deployment at the TLG–Denton

facility, pending on-site validation of latency and false-alarm rates.

By releasing open-source scripts, datasets, and exportable

route files, this work promotes transparency, reproducibility, and adaptation

for other industrial sites. The integration of YOLO-based object detection with

advanced geofence routing demonstrates how UAV fleets can be seamlessly

connected to ground-based security systems, enabling real-time data sharing and

coordinated incident response.

This scalable, multi-layered surveillance infrastructure

strengthens operational safety while supporting actionable decision-making and

rapid threat mitigation. Overall, the proposed platform establishes a

reproducible model for future UAV deployments, setting a benchmark for

regulation-compliant, AI-driven security solutions in industrial environments.

To maximize the effectiveness and longevity of the proposed

system, several actionable recommendations are provided:

-

Advanced Operator Training:

Implement specialized training programs for UAV operators, particularly emphasizing Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) certifications and emergency response readiness.

-

Cross-Agency Collaboration:

Establish formal partnerships with municipal emergency services to enable coordinated responses to incidents such as fires, accidents, and natural disasters.

AI-Driven Predictive Analytics:Upgrade the surveillance system with predictive threat detection models capable of identifying and anticipating risks before escalation, thus enabling proactive interventions.

-

Continuous Data and Model Updates:

Regularly update datasets and retrain detection algorithms to address evolving environmental factors, operational conditions, and potential adversarial threats.

By following these recommendations, TLG can maintain a cutting-edge surveillance ecosystem, ensuring resilience, compliance, and preparedness for future operational challenges.

6. Ethical Considerations & Compliance

The deployment of an incident-aware, geofenced UAV surveillance

system introduces significant ethical, legal, and societal implications. This

project was designed with a strong emphasis on responsible innovation, ensuring

that security objectives are met without compromising privacy, safety, or

regulatory obligations.

6.1. Privacy Protection and Data Governance

UAVs equipped with high-resolution RGB and thermal sensors

inherently pose risks of inadvertent surveillance of neighboring properties,

individuals, or sensitive operational areas. To mitigate these risks:

Geofencing Enforcement: All UAV flight paths are geofence-constrained to remain strictly within TLG’s operational boundaries, preventing accidental incursions into public or private spaces.

Privacy-Preserving Analytics: Facial recognition and personally identifiable information (PII) are processed using on-edge inference, ensuring raw image data never leaves the UAV or local network. Sensitive frames are redacted or anonymized before archival.

Data Retention Policy: Video streams and telemetry logs are stored only for operational audits and incident investigations, with strict retention limits in accordance with GDPR and POPIA principles.

Informed Signage: Visible public notices and clear signage are deployed at facility boundaries to inform employees, contractors, and visitors about UAV monitoring practices.

6.2. Safety and Airspace Compliance

To protect personnel, property, and the surrounding

community, UAV operations follow rigorous safety and regulatory frameworks:

Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) Standards: Compliance with FAA BVLOS (Federal Aviation Administration, 2025) and GCAA UAV regulations, including certified pilot training, safety management systems (SMS), and auditable mission logs.

Fail-Safe Systems: Automatic Return-to-Base (RTB) protocols are triggered for low battery levels, lost signal events, or hazardous weather conditions, ensuring UAVs land safely without endangering workers or nearby vehicles.

No-Fly Zone Protection: Circular and polygonal geofences are digitally enforced to prevent flights over schools, roads, and neighboring companies. Hazard maps (e.g., active truck zones, power lines) are dynamically updated in real time.

Incident Simulation Testing: Before live deployment, all flight plans and algorithms are tested in simulation (AirSim environment) to validate control-barrier functions and collision avoidance logic.

6.3. Cybersecurity and Integrity

UAV surveillance systems are vulnerable to cyber threats

such as GPS spoofing, jamming, and video feed hijacking. This project

incorporates:

End-to-End Encryption: AES-256 encryption for telemetry, video feeds, and mission data transmissions to prevent interception or tampering.

Authentication & Access Control: Multi-factor authentication for ground control stations (GCS) and operator logins, ensuring only authorized personnel can issue commands.

Red Team Testing: Regular penetration testing of communication channels to identify weaknesses and strengthen defenses.

Secure AI Models: Models are protected against adversarial attacks through adversarial training and checksum-verified model deployment.

6.4. Ethics, Compliance & AI Statement

This study used only

public/synthetic data (e.g., VisDrone) and did not involve human subjects or

personally identifiable information. Operational concepts follow FAA BVLOS and

geofencing best practices; deployment will proceed under local regulatory approvals.

An AI assistant was used solely for language polishing and figure composition;

all scientific work was performed by the author.

6.5. Community and Stakeholder Engagement

The success of UAV surveillance depends on public trust.

Engagement measures include:

Stakeholder Briefings: Regular meetings with local authorities, community representatives, and employee unions to address concerns and communicate operational policies.

Transparency Reports: Quarterly reports summarizing UAV activities, incidents, and privacy compliance audits will be published internally and externally.

Public Awareness Campaigns: Educational materials are provided to clarify the role and limitations of UAV monitoring, emphasizing its focus on safety and asset protection.

6.6. Academic Integrity and Research Ethics

Open Science Commitment: The algorithms, data splits, and route files (e.g., astar_path.csv, tlg_routes.geojson) are shared for reproducibility under open licenses, with proper citations to foundational works.