1. Introduction

Contemporary China is undergoing a profound transformation in its educational paradigm. The comprehensive implementation of the "Double Reduction" policy (i.e., the Opinions on Further Reducing the Homework Burden and Off-campus Training Burden for Students in Compulsory Education) has not only reshaped the ecology of basic education but also posed new demands on urban spaces. By systematically alleviating students’ excessive academic workload and off-campus training burdens, this policy restores time and agency for self-development to children, marking a significant shift in China’s educational philosophy from an “exam-oriented” approach to one emphasizing “holistic development.” However, changes in educational policy often trigger ripple effects beyond the educational sphere. Among these, one of the most notable yet easily overlooked impacts is its profound influence on the urban built environment—particularly on the usage patterns of spaces surrounding schools.

With the relative extension of students’ in-school hours and the increase in after-school free time, the function and usage of pick-up and drop-off zones near schools are undergoing a qualitative metamorphosis. These once-transient spaces, previously used only briefly during peak school hours, are gradually transforming into potential important venues for children’s after-school socializing, play, waiting, and relaxation. This shift represents not merely a quantitative change, but a fundamental evolution in spatial function and nature: from mere “passage areas” and “distribution points” to multifunctional “urban public spaces.” This transformation brings unprecedented opportunities while also exposing numerous deficiencies in the existing urban environment, thereby presenting new challenges for urban planning and design.

Unfortunately, the planning and design of school drop-off and pick-up spaces in most Chinese cities currently lag significantly behind this social demand. Most of these spaces are products of planning and construction based on an "adult perspective" that prioritizes efficiency and traffic flow in high-density urban environments. Their design logic primarily focuses on the rapid passage and brief parking of motor vehicles, rather than accommodating children's needs for staying and activities. This deviation in design philosophy has led to widespread spatial alienation: chaotic interweaving of pedestrian and vehicle traffic flows, lacking effective safety segregation; dominance of hard paving, with insufficient greenery and shading facilities; severe shortage of resting amenities, and an environment devoid of playfulness and explorability.

A more profound issue is that these spatial designs reflect a deep-seated "adultism" tendency—decision-makers and designers habitually use their own experiences and needs as a blueprint, unintentionally neglecting the behavioral patterns, perceptual scales, and psychological needs of children as an important user group, resulting in the "passive silence" of children in terms of spatial rights.

This mismatch between space and demand not only causes inconvenience in use but may also negatively impact children's physical and mental development. Environmental psychology research shows that the quality of the built environment directly affects children's spatial cognition, social interaction, and mental health. Drop-off and pick-up spaces lacking humanized design may exacerbate children's anxiety, inhibit their willingness to engage in social interactions, and even impair the development of their independent activity abilities. Meanwhile, high-quality public space experiences can promote children's social development and foster their environmental exploration skills and sense of spatial belonging. Therefore, improving the environmental quality of school drop-off and pick-up spaces is not only an urban design issue but also an important matter related to the healthy development of children.

In this context, promoting the transformation of school drop-off and pick-up spaces into "child-friendly" ones holds multiple significant meanings. First, it is a deep response to and extension of the connotations of the "Double Reduction" policy. The core goal of the policy is to promote the holistic development and healthy growth of students, and a high-quality off-campus environment is crucial for achieving this goal. Second, it is a concrete practice of implementing the "Child-Friendly City" concept. The UNICEF-led Child-Friendly Cities Initiative emphasizes that children have the right to enjoy various services provided by the city and to participate in the city's decision-making processes. As one of the most frequently used urban public spaces by children daily, the environmental quality of areas around schools directly affects the effectiveness of building child-friendly cities. Finally, it is an important opportunity to enhance the humanistic care in urban public spaces. By focusing on the needs of this specific group, it can drive a shift in urban design philosophy from "vehicle-oriented" to "people-oriented," thereby improving the environmental quality of the entire city.

However, achieving this transformation faces significant intellectual challenges. Current research on school pickup and drop-off spaces exhibits notable shortcomings: on one hand, existing studies predominantly focus on the field of traffic engineering, prioritizing vehicle flow organization and transportation efficiency, while lacking in-depth exploration of children's behaviors and needs; on the other hand, prevailing spatial design research often relies on designers' subjective experiences or standardized norms, lacking support from evidence-based behavioral studies. This research gap results in design decisions being made without scientific foundation, failing to genuinely address the actual needs of children. More importantly, traditional research methods often treat children as passive subjects rather than active participants, making it difficult to capture their authentic spatial experiences and requirements.

To address this challenge, this study proposes a behavior simulation-based, child-centered design research paradigm. We argue that to truly understand children's spatial needs, an immersive and interpretative research approach must be adopted, employing in-depth qualitative methods to "simulate" and interpret children's "behavioral language" in specific spatial contexts. This methodological innovation enables us to move beyond superficial observations of space usage and delve into the underlying mechanisms of children's interactions with their environment. By integrating environmental psychology, behavioral architecture, and participatory design methodologies, this study constructs a comprehensive research framework through multi-dimensional methods.

Specifically, this study aims to achieve the following core objectives: First, through systematic field observations and behavioral mapping, to document and analyze the typical behavioral patterns, gathering characteristics, and social interactions of school-aged children in pickup and drop-off spaces following the "double reduction" policy, establishing correlations between behavioral modes and spatial features. Second, via in-depth interviews and participatory workshops, to uncover children's perceptions, experiences, and latent aspirations regarding such spaces, revealing the interaction mechanisms between environmental elements (e.g., scale, interfaces, facilities, natural elements) and their behavioral psychology. Finally, based on empirical findings, to develop a theoretically grounded and practically actionable design strategy framework for child-friendly school pickup and drop-off spaces, offering precise design insights for urban micro-renewal in high-density city contexts.

The theoretical value of this study lies in deepening the understanding of the interaction mechanisms between environment and children's behavior, enriching the application of child-friendly city theory at the micro-spatial level, particularly within the context of high-density Chinese cities. On a practical level, the research outcomes will provide urban planners, architects, and educational administrators with specific, operable design guidelines and policy recommendations, contributing to the creation of urban environments that genuinely support children's healthy development.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 will provide a systematic review of theoretical and practical research related to the "double reduction" policy, child-friendly cities, and environmental behavior studies, clarifying the theoretical positioning and innovations of this research.

Section 3 will elaborate on the multi-method research design centered on qualitative approaches.

Section 4 will present core findings through in-depth analysis of typical cases.

Section 5 will engage in comprehensive discussion based on the findings and propose a systematic design strategy framework. Finally,

Section 6 will summarize the conclusions and indicate the study's limitations and future research directions. Through this structured approach, we aim to provide solid theoretical foundation and practical guidance for the child-adaptive transformation of school pickup and drop-off spaces, contributing professional expertise to the advancement of child-friendly urban development in Chinese cities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The "Double Reduction" Policy and the Restructuring of Children’s Spatiotemporal Behavior Patterns

As a significant reform in China’s basic education system, the "Double Reduction" policy has exerted influence far beyond the educational domain, profoundly reshaping the daily spatiotemporal structure and behavioral patterns of school-aged children. By systematically alleviating students’ excessive homework burdens and reducing off-campus training, the policy essentially reconfigures children’s daily time allocation and spatial arrangements for activities. Previous studies have predominantly focused on evaluating the educational outcomes of the policy, often overlooking its impact on spatial usage. In reality, following the implementation of the policy, children’s time spent at school has relatively increased, while their after-school discretionary time has expanded. This shift in temporal structure directly contributes to a transformation in their spatial activity patterns.

In conventional research, school pickup and drop-off zones are generally regarded merely as nodes of transportation transition, with design and management principles primarily aimed at maximizing efficiency and ensuring safety. However, in the context of the "Double Reduction" policy, the function of these spaces is undergoing a fundamental change: transitioning from purely circulatory areas into multifunctional spaces that integrate waiting, social interaction, play, and other activities. This transformation poses new demands on the urban built environment, yet existing studies have not systematically explored this shift in spatial function or its implications for child development.

It is worth noting that the high-density nature of China’s urbanization process has led to particularly strained spatial resources around schools, exacerbating issues such as vehicle-pedestrian conflicts and spatial compression [

1]. Against this backdrop, changes in spatial usage patterns brought about by the "Double Reduction" policy further intensify the contradiction between existing spatial supply and emerging demands. Nevertheless, current research predominantly approaches the topic from perspectives of transportation planning or educational policy, lacking systematic investigation from a spatial design standpoint—especially in-depth understanding of children’s own spatial experiences and needs.

2.2. Evolution of Spatial Design Theory Under the Child-Friendly City Concept

Since its initial proposal by UNICEF in 1996, the Child-Friendly City (CFC) concept has evolved into a significant direction for global urban development. This concept emphasizes the rights of children as urban citizens, including their right to equitable access to urban services, participation in urban decision-making, and growth in a safe and inclusive environment [

2]. In recent years, the CFC concept has transitioned from macro-level policy advocacy to micro-level spatial practices, with a particular focus on the role of the everyday built environment in supporting child development [

3].

In the context of school-adjacent environment design, international research has established a relatively mature theoretical framework. For instance, the "walkable school" concept highlights the enhancement of children’s independent mobility through physical environment design [

4], while the "safe routes to school" program employs multidimensional interventions to improve the safety of school travel environments [

5]. These studies generally agree that well-designed school-adjacent environments not only address safety concerns but also directly influence children’s physical activity levels, social interaction quality, and environmental cognitive development.

However, existing research exhibits notable limitations in cultural adaptability. Theories and methods developed in Western urban contexts are difficult to directly apply to high-density urban environments in China. The unique characteristics of Chinese cities—such as high-density development, multifunctional land use, and high-intensity spatial utilization—necessitate the development of localized design theories and approaches. This is especially critical for highly integrated micro-spaces like school drop-off and pick-up zones, which require innovative exploration within the local context.

2.3. Mechanisms of Child–Environment Interaction from an Environmental Psychology Perspective

Environmental psychology offers a critical theoretical framework for understanding the interaction between children and the built environment. According to Gibson’s (2014) theory of affordance, the environment is not a passive container but an active medium that provides various possibilities for action [

6]. For children, the richness of environmental affordances directly influences their behavioral patterns and developmental opportunities. As one of the most frequently encountered urban public spaces in children’s daily lives, school drop-off and pickup zones impact children’s behavior and experiences through multiple psychological mechanisms, shaped by their physical environmental characteristics.

The first dimension is spatial cognition. Lynch’s (2020) research on urban imagery reveals that children’s spatial cognition exhibits distinct age-related and experiential traits [

7]. Clear spatial structures, recognizable landmarks, and appropriately scaled spaces contribute to the formation of positive environmental cognitive maps in children. However, many current school drop-off and pickup spaces lack well-defined spatial organization and sign systems, increasing children’s cognitive load in environmental perception.

The second dimension involves place attachment theory. Studies indicate that children readily develop emotional bonds with frequently used spaces, which play a significant role in their psychological well-being and social identity [

8]. Participatory design and opportunities for personalized expression can enhance children’s sense of belonging and ownership toward these spaces. Nevertheless, standardized, adult-centric designs often overlook children’s emotional needs, resulting in spaces that lack individuality and warmth.

The third dimension is rooted in behavior setting theory. This theory emphasizes the interaction between the physical environment and social behavior [

9]. In school drop-off and pickup spaces, specific combinations of spatial elements—such as waiting areas, play corners, and green facilities—can foster corresponding behavioral patterns. Through carefully designed behavior settings, positive spatial usage can be encouraged, promoting social interaction and autonomous activities among children.

2.4. Methodological Evolution and Practical Challenges in Participatory Design with Children

The methodology of participatory design with children has undergone a paradigm shift from designing for children to designing with children [

10]. In traditional design practices, children were often regarded as passive recipients, with their needs and preferences indirectly represented through adult perspectives [

11]. In contrast, participatory design approaches recognize children as experts in their own right, emphasizing that they hold the most relevant insights regarding their lived experiences and spatial needs.

On a methodological level, participatory tools tailored to children’s cognitive characteristics continue to diversify and evolve. Visual methods (e.g., drawing, model-making), gamified approaches (e.g., role-playing, scenario simulation), and experiential techniques (e.g., walking interviews, behavioral observation) have proven effective in facilitating participation. These methods not only help elicit children’s spatial preferences but, more importantly, stimulate their creativity and imagination, yielding design ideas that transcend the limitations of adult-centric thinking.

However, participatory design with children faces unique challenges within the Chinese context. On one hand, traditional cultural norms emphasizing adult authority may inhibit children’s willingness and ability to express themselves openly. On the other hand, high-density urban environments often lead to scarce spatial resources, resulting in more frequent design compromises. Furthermore, methodological questions remain regarding how to accommodate varying capabilities among children of different ages, and how to translate their imaginative ideas into feasible design solutions.

2.5. Research Gaps and Positioning of this Study

Through a systematic review of existing literature, several significant research gaps have been identified.

First, current studies pay insufficient attention to the spatial impacts of the "double reduction" policy. While much research focuses on evaluating educational outcomes, there is a lack of in-depth exploration of how the policy alters spatial usage patterns and its implications for design. The functional transformation of school drop-off and pick-up spaces following policy implementation remains understudied. Second, research on the application of the child-friendly city concept in high-density urban environments in China is still relatively weak. Particularly for intensive micro-spaces such as school drop-off and pick-up areas, targeted design theories and guiding principles are lacking. The localization of international experiences requires further empirical support. Third, the application of environmental psychology perspectives in research on school surroundings is not yet systematic. Although theories such as affordance and place attachment have been introduced, there is limited in-depth exploration of how these theories can be concretely applied in design practice. Specifically, the relationship between physical environmental elements and children's psychological behaviors needs further refinement. Fourth, the practical application of child participatory design methods in school space design remains underdeveloped. Existing studies often focus on describing participatory processes but fall short of examining how participatory outcomes can be effectively translated into design strategies. The applicability and effectiveness of different participatory methods also require more empirical comparison.

Based on these research gaps, this study is positioned as follows: against the backdrop of the "double reduction" policy, it employs environmental psychology and participatory design methodologies to explore child-adaptive design strategies for school drop-off and pick-up spaces in high-density urban environments. Using qualitative research methods, the study aims to gain a deep understanding of children's spatial needs and behavioral patterns, thereby providing theoretical support and practical guidance for the implementation of the child-friendly city concept at the micro-spatial level.

The significance of this research is threefold: Theoretically, it enriches and expands the application of child-friendly city theory at the micro-spatial level, particularly contributing to theoretical innovation in the context of high-density Chinese cities. Practically, it offers actionable design guidelines for urban designers, planners, and educational administrators to enhance the quality of school surroundings. Methodologically, it explores child participatory design approaches suitable for China’s cultural context, promoting a paradigm shift in design practice.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Paradigm and Overall Design

This study adopts an interpretivist research paradigm, grounded in constructivist epistemology, which emphasizes the construction of knowledge through in-depth understanding and interpretation of social phenomena. At the methodological level, the research employs an integrated mixed-methods strategy with a qualitative dominance, exploring the complex mechanisms of children’s behavioral patterns and environmental interactions within school pickup/drop-off zones under the "Double Reduction" policy through immersive engagement and contextualized comprehension. The overall research design is structured as a multiple case study [

12], incorporating participatory observation, in-depth interviews, and participatory design workshops to gather rich first-hand data from multiple perspectives.

The research design adheres to the principles of depth and holism characteristic of qualitative inquiry, prioritizing data collection in natural settings and focusing on the meaning-making and understanding of research participants. Aligned with the research objectives, a longitudinal approach is adopted, with continuous tracking and observation of selected cases throughout a full semester from February to July 2025, aiming to capture the dynamic evolution of school pickup/drop-off space usage patterns following the implementation of the "Double Reduction" policy.

3.2. Case Selection and Characteristics

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to select three representative primary schools in the Yangtze River Delta region as research cases. Case selection was based on the following dimensions: (1) urban location: covering central urban areas, urban-rural junctions, and emerging urban districts; (2) school size: including large (over 2,000 students), medium (1,000–2,000 students), and small (under 1,000 students) categories; and (3) establishment period: encompassing traditional old schools, renovated/expanded schools, and newly built schools. This sampling strategy ensures diversity and representativeness of the cases, laying a solid foundation for subsequent comparative analysis.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the research case.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the research case.

| Case ID |

Location |

Student Population |

Year Established |

Surrounding Environment Features |

Pick-up/Drop-off Space Type |

| Case A |

Central urban area |

2,700 students |

2017 |

High-density built-up area |

Curb-side temporary pick-up |

| Case B |

Emerging urban area |

4,650 students |

2017 |

Mixed-development area |

Dedicated parking lot |

| Case C |

Urban-rural fringe |

1,200 students |

2016 |

Transitional urban zone |

Hybrid space |

| |

The selection of cases was based on their potential to provide rich information and maximum comparative value. Each case is typical in specific dimensions, offering unique perspectives for understanding the use of school pickup and drop-off spaces across different contexts.

3.3. Data Collection Methods

This study employed a multi-method approach for data collection, which primarily included the following four techniques:

3.3.1. Participatory Observation

The observation was conducted over one full academic term, with a focus on periods before and after school, as well as during after-school service hours. A semi-structured approach was adopted using a self-developed observation protocol. Documented aspects included: spatial usage patterns, organization of pedestrian and vehicle flows, types of children’s activities, forms of social interaction, and utilization of environmental elements. Special attention was paid to children’s unsolicited behaviors and their ways of interacting with the environment. In order to ensure systematic and comprehensive observation, a detailed observation schedule (

Table 2) was developed.

3.3.2. In-Depth Interviews

The interviewees comprised four groups: children (stratified by lower, middle, and upper grades), parents, teachers, and school administrators. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using tailored guides for each group, focusing on their perceptions, experiences, and expectations regarding school pickup/drop-off spaces. Interviews with children employed a contextualized approach, conducted in real-world settings with visual aids such as drawings and photographs to facilitate expression. A total of 62 interviews were completed: 28 with children, 18 with parents, 10 with teachers, and 6 with administrators.

3.3.3. Participatory Design Workshops

Two workshops were organized in each case school, utilizing a variety of child-friendly participatory tools and methods: (1) Drawing Expression: Children sketched "My Ideal School Entrance"; (2) Model Building: Three-dimensional spatial models were constructed using materials like Lego and clay; (3) Role-Playing: Simulations of spatial experiences in different usage scenarios; (4) Scenario Storytelling: Narratives of stories occurring at school entrances. All workshops were video-recorded, and physical outputs were collected as analytical materials.

3.3.4. Visual Data Collection

Extensive visual materials were gathered, including spatial photographs, video recordings, children’s drawings, and design models. A systematic photographic approach was adopted, encompassing fixed-point timed shots, tracking shots, and event-based documentation to comprehensively capture spatial usage patterns and environmental features.

3.4. Data Analysis Methods

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis [

13], following the six-step framework proposed by Braun and Clarke: familiarization with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. The analysis combined manual coding with software-assisted support using NVivo 12.

3.4.1. Coding Framework Development

A theoretically grounded multi-level coding framework was established [

14]. First-level codes were derived from environmental psychology theories, encompassing dimensions such as affordance perception, spatial cognition, and place attachment. Second-level codes emerged from patterns identified during field observations. Third-level codes remained open to incorporate newly emerging themes. This hybrid top-down and bottom-up coding strategy ensured theoretical depth and empirical grounding.

3.4.2. Visual Data Analysis

Visual materials were analyzed through a combination of content analysis and semiotic analysis. Photographs and videos were initially categorized and annotated to identify recurring patterns and behavioral types. Semiotic analysis was then applied to interpret cultural meanings and social representations embedded in visual elements. Particular attention was paid to metaphors and symbolic expressions in children’s drawings and models.

3.4.3. Spatial Behavior Analysis

Behavioral observation data were integrated with spatial characteristics and analyzed using the behavioral mapping method [

15] to examine the interaction between space and behavior. By overlaying spatial usage patterns across different time periods and user groups, key behavioral hotspots and spatial design issues were identified (

Figure 1).

3.5. Research Quality Assurance

To ensure the reliability and validity of the study, multiple strategies were employed to safeguard research quality:

3.5.1. Triangulation

Methodological, data source (multiple cases), and investigator triangulation were applied to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings.

3.5.2. Constant Comparative Analysis

The constant comparative method was used throughout data collection to facilitate ongoing comparison and reflection, allowing for adjustments in research focus and methods to maintain reflexivity and adaptability.

3.5.3. Member Checking

Preliminary findings were shared with selected participants (particularly teachers and older children) to solicit feedback and interpretations, ensuring that the conclusions aligned with local contexts.

3.5.4. Peer Debriefing

Regular discussions were held with peer experts outside the research team to address potential biases and incorporate external critiques and suggestions.

3.5.5. Rich Contextual Description

Detailed contextual descriptions and verbatim quotations were provided to enable readers to assess the transferability of conclusions and support subsequent research with sufficient contextual information.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

This study strictly adhered to academic ethical standards. Given the specificities of research involving children, the following ethical measures were implemented:

First, authentic informed consent was obtained. Child-friendly assent forms using visual and verbal explanations were provided to ensure children understood the research purpose and process. Written consent was also acquired from parents and schools. Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time.

Second, privacy and confidentiality were protected. All personal identifiers were anonymized, and pseudonyms were used in place of real names. Identifiable images or information were excluded in public dissemination.

Third, a non-harmful approach was adopted. Research settings were designed to avoid discomfort or risk, and all activities took place in safe environments. Emotional responses were monitored closely, and psychological support was provided when necessary.

Finally, beneficence was ensured. Research outcomes were shared with participating schools and communities to provide practical recommendations for improving school pick-up and drop-off spaces, enabling tangible benefits from the study.

3.7. Limitations and Reflexivity

This study has several limitations. First, all cases were selected from the Yangtze River Delta region, which may affect the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Second, while qualitative methods allow in-depth understanding, large-scale validation remains challenging. Third, although participatory methods with children yielded rich data, the limited expressive abilities of younger children may affect data comprehensiveness.

The researchers continuously reflected on their roles, balancing professional distance for objective observation with engaged rapport-building through participatory methods to gather authentic data [

16]. Regular memos were maintained to document reflections and insights throughout the study, enhancing transparency and trustworthiness.

Through the integration of these multiple approaches, this study aims to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of children’s behavioral patterns and environmental needs in school pick-up and drop-off spaces under the “Double Reduction” policy, laying a solid empirical foundation for subsequent design strategies.

4. Case Analysis and Findings

4.1. Case Background and Spatial Characteristics

The three case study schools selected for this research exhibit distinct spatial characteristics (

Table 3 and

Table 4), providing a robust foundation for comparative analysis. Case A is situated in a high-density built-up area, with a site area of only 1.2 hectares yet accommodating 2,700 students—resulting in a severe shortage of per capita site area. Its pick-up and drop-off zone is confined to a sidewalk less than 5 meters wide, lacking effective separation from vehicular traffic. Case B, located in an emerging urban district, features a relatively spacious dedicated pick-up/drop-off plaza (approximately 800 m²). However, the space is monotonous in design, dominated by hard paving, and lacks functional zoning or human-centered amenities. Case C demonstrates transitional characteristics, with its pick-up and drop-off area comprising both on-campus grounds and external sidewalks, forming a unique “gray space” transition zone.

Through spatial behavior annotation, significant differences in peak pedestrian flow were observed among the three cases. Case A experienced extreme crowd density of up to 850 persons per square meter within 15 minutes after school dismissal, resulting in severe spatial congestion. Case B exhibited a crowd density of 4.6 persons per square meter but demonstrated low spatial utilization efficiency. In contrast, Case C displayed a dual-peak pattern corresponding to after-school care services and regular dismissal periods.

4.2. Mapping Children's Behavioral Patterns

Based on over 120 hours of on-site observation and behavioral notes, we identified four typical behavioral patterns:

4.2.1. Linear Traversal Behavior

This represents the most fundamental form of spatial usage, accounting for approximately 65% of all observed behaviors. Children traversed the pick-up area via the shortest path, demonstrating clear goal-directed movement. However, significant variations were observed across cases: In Case A, children frequently avoided obstacles and changed directions, with an average speed of merely 0.4 m/s; in Case B, they maintained a relatively steady walking speed of 0.8 m/s; whereas Case C exhibited notable speed fluctuations, reflecting the impact of access control measures.

4.2.2. Patch-Type Staying Behavior

Approximately 28% of children formed temporary aggregates in specific areas. These "patches" typically emerged at: (1) waiting zones near school exits; (2) peripheral areas of green facilities or buildings; (3) surroundings of snack shops or vendors. The duration of these staying patches ranged from 3 to 25 minutes, forming transient social spaces. Notably, in Case B, despite the presence of a dedicated plaza, children showed a distinct preference for gathering around tree pits and building recesses at the plaza edges, indicating a particular affinity for boundary areas.

4.2.3. Social Play Behavior

Following the implementation of the "Double Reduction" policy, social play behaviors increased significantly, comprising about 7% of observed activities. These play behaviors exhibited three characteristics: (1) Spontaneity: 93% of play activities were initiated by children themselves; (2) Adaptability: environmental elements were fully utilized, such as using tile patterns as game grids and railings as balance beams; (3) Brevity: constrained by pick-up schedules, the average duration was 8.5 minutes. The most diverse play types were observed in Case C, including traditional games (hopscotch, tag) and imaginative play (pretend scenario dramas).

4.2.4. Exploratory Behavior

Primarily observed among younger children (aged 6-8), these behaviors manifested as active environmental exploration: touching wall textures, observing insects, chasing falling leaves, etc. Although accounting for only 2% of all behaviors, they reflect children's innate curiosity and desire to explore. Exploratory behaviors were severely suppressed in Case A due to safety concerns and spatial constraints; in Case B, they predominantly occurred in limited green areas (

Figure 2); whereas Case C provided relatively rich exploratory opportunities owing to its abundant natural elements.

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution density of different behavioral types within the pickup/drop-off area of Case B, revealing distinct regional differentiation phenomena.

4.3. Mechanisms of Interaction Between Environmental Elements and Behavior

In-depth analysis reveals complex interactions between physical environmental elements and children’s behaviors. These findings provide critical insights for designing interventions.

4.3.1. Spatial Scale and Boundary Effects

The study found that children exhibit high sensitivity to spatial dimensions. Excessively large and unshielded open spaces (e.g., the plaza in Case B) tend to induce unease, whereas children show a preference for intimate, enclosed areas with clear boundaries. In Case A, despite the limited space, the "street canyon" effect formed by building facades provided a sense of psychological security. Boundary zones (e.g., building edges and greenbelt margins) emerged as the most favored activity spaces, offering both back support and prospect visibility—consistent with evolved human environmental preferences [

17].

4.3.2. Emotional Value of Natural Elements

Natural elements such as trees, grass, and water bodies hold significant emotional value for children [

18]. Observations indicated that even inaccessible lawns (e.g., in Case B) exerted a calming effect through visual presence. In Case C, isolated plants served as key landmarks and gathering points, with shaded areas forming "natural living rooms" that hosted various social activities. Natural elements appeared in 78% of children’s drawings, reflecting a strong desire for natural environments.

4.3.3. Operability and Creative Use

The manipulability and variability of environmental elements significantly influenced how children utilized spaces. Fixed stone benches in Case B were rarely used, whereas movable plastic barrels in Case C were repurposed creatively as play props. During participatory workshops, children showed a strong preference for interactive elements such as water features, movable seating, and tactile walls, which support their propensity to actively shape their environment.

4.3.4. Color and Visual Stimuli

Visual environments directly affected children’s emotions and behaviors. Large wall paintings in Case B became key visual anchors and orientation reference points, prolonging children’s stay in these areas. Pavement patterns with high color contrast naturally elicited playful behaviors (e.g., hopscotch, balance beam games), whereas monotonous gray pavements generated little interaction. Children preferred bright yet non-glaring color schemes, with moderately saturated primary colors being the most favored.

4.4. In-Depth Interpretation of Children’s Perceptions and Experiences

Through in-depth interviews and participatory workshops with 28 children, we identified four core experiential dimensions of children’s engagement with pickup and drop-off spaces.

4.4.1. Tension Between Safety and Autonomy

Older children (ages 10–12) widely expressed a strong desire for independent activities, preferring areas “where we can play by ourselves for a while.” Younger children, however, placed greater emphasis on visual connection with caregivers and a sense of security. All children expressed concerns about the threat posed by motor vehicles, with comments such as “the cars get too close” being a common complaint in Case A. Interestingly, children’s definitions of safety differed from those of adults: they were more concerned with social safety (“I don’t want to be bumped into by bigger kids”) and psychological safety (“I don’t want teachers watching me”), whereas adults focused more on physical and traffic safety.

4.4.2. Playfulness and the Need for Exploration

“Fun” emerged as a central criterion in children’s evaluations of a space. They preferred places “where you can discover things” (such as the ant colony in Case C), “where you can invent new ways to play” (e.g., movable equipment), and areas that “feel like a secret corner” (small-scale enclosed spaces). Monotonous environments were often described as “places where you just wait and there’s nothing to do.”

4.4.3. Social Opportunities and Peer Interaction

Children regarded pickup and drop-off spaces as important social environments. Common activities included “chatting with friends,” “watching others play,” and “making new friends.” Older children especially valued these relatively free social opportunities, as school hours are often highly regulated. Spatial design directly influenced the quality of social interaction: in Case B, a lack of seating led to complaints that “standing and talking is exhausting,” while varied seating opportunities in Case C supported longer and more comfortable social exchanges.

4.4.4. Nature Contact and Sensory Experience

Children demonstrated a strong preference for and sensitivity to natural elements. Expressions such as “the wind blowing feels nice,” “I like seeing the different shades of green in the leaves,” and “puddles are fun when it rains” highlighted their desire for multisensory experiences. Contact with nature was also imbued with emotional significance: for instance, “the big tree is like an umbrella protecting us.”

Table 5.

A Comparison of Spatial Preferences Across Different Age Groups in Children.

Table 5.

A Comparison of Spatial Preferences Across Different Age Groups in Children.

| Experience Dimension |

Lower Grades (6-8 years) |

Middle Grades (9-10 years) |

Upper Grades (11-12 years) |

| Safety Needs |

Physical safety and visual contact |

Activity safety and social security |

Psychological safety and autonomy |

| Spatial Preferences |

Small-scale, clearly defined boundaries |

Flexible and versatile spaces |

Semi-private spaces with autonomy |

| Activity Types |

Imaginative play, exploration |

Rule-based games, socializing |

Conversation, observation, self-directed activities |

| Nature Interaction |

Sensory exploration, touching |

Play materials, background element |

Aesthetic experience, relaxation |

4.5. Comparison and Conflict Among Multiple Stakeholder Perspectives

The study reveals significant differences and even conflicts in the needs and evaluations of various stakeholders regarding pick-up spaces. This tension among multiple perspectives presents a practical challenge that must be addressed in design.

4.5.1. Differences Between Children’s and Parents’ Perspectives

Parents prioritize efficiency and traffic safety (“quickly picking up the child and avoiding accidents”) over spatial quality. They generally exhibit caution toward children’s independent activities due to safety concerns. This protective attitude directly conflicts with children’s desire for autonomous exploration. In Case B, parents expressed concerns about children using plaza play facilities: “They might bump into each other while running around” and “What if they fall on the hard ground?”

4.5.2. School Management Perspective

School administrators prioritize management efficiency and liability risks. Phrases such as “easy to manage,” “avoid crowding,” and “clear responsibilities” are commonly used. They tend to simplify spatial functions and eliminate elements that may cause management difficulties, such as movable facilities or complex terrain. This managerialist approach inherently conflicts with children’s need for diverse environmental experiences.

4.5.3. Community and Neighboring Perspectives

Residents and local businesses hold divergent views on the impact of pick-up spaces. Residents complain about noise and congestion during pick-up hours, while businesses see commercial opportunities (e.g., opening stationery stores or snack stalls). Such externalities increase the complexity of spatial design, necessitating a balance among multiple interests (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

The figure illustrates the primary needs and potential conflicts among the four key stakeholders—children, parents, schools, and communities—as well as possible strategies for design integration.

4.6. Design Implications and Innovative Opportunities

Based on the findings above, we have distilled the following key design implications:

4.6.1. Spatial Zoning and Temporal Sharing

A “spatial–temporal sharing” strategy is recommended, utilizing movable facilities and flexible design to allow the same space to serve different functions at different times. For instance, a space may function as an efficient circulation zone during school hours and transform into a social or play area after school. Clearly defined yet adaptable functional zones should be established—including quick-passage areas, waiting zones, play sections, and nature experience areas—while maintaining visual connections between them.

4.6.2. Boundary Optimization and Scale Management

Enhance the design value of boundary areas by replacing rigid barriers with “soft boundaries” such as low hedges and varied paving materials. These define spaces without compromising visual permeability. Create a series of spatial pockets of varying scales to accommodate needs ranging from individual solitude to small-group gatherings. Special attention should be paid to the integrated design of building facades and ground-level spaces to form active spatial interfaces.

4.6.3. Natural Integration and Sensory Enrichment

Incorporate natural elements as core components of the design, not only providing greenery but also creating opportunities for interaction with nature—such as touching, smelling, and observing. Introduce multi-sensory experiences including visual (color, light and shadow), auditory (sound of water, wind chimes), and tactile (varied textures) elements to enhance the emotional value of the space.

4.6.4. Flexibility and Participatory Design

Incorporate modifiable environmental features such as movable seating, modular play components, and seasonal planting to support children’s creative use of space. Reserve “unfinished” spaces that allow children to participate in the ongoing shaping of their environment, thereby strengthening their sense of place identity.

4.6.5. Redefining Safety and Balancing Autonomy

Reconceptualize safety by shifting from purely physical protection toward environmental design that supports appropriate risk-taking. Balance safety and autonomy through a strategy of “visible yet not immediately accessible”—maintaining visual connection between children and caregivers while providing relatively independent activity spaces. Employ design techniques such as combining soft and hard materials, and incorporating subtle elevation changes, to provide opportunities for managed risk experiences.

These findings provide a solid empirical foundation for subsequent design strategies, revealing both the complexity and innovative possibilities inherent in designing school-related transition spaces under the Double Reduction policy. By deeply understanding children’s behavioral patterns and environmental experiences, we can create urban spaces that genuinely support their healthy development.

5. Discussion and Design Strategies

5.1. Theoretical Insights and Scholarly Dialogue

The behavioral patterns revealed in this study (

Section 4.2) not only corroborate the core tenets of the “affordance” theory in environmental psychology but also extend its interpretive dimensions within Chinese educational settings. In contrast to Gibson’s assertions, children’s perception of spatial functions extends beyond the physical level to incorporate socio-emotional needs and creative imagination—for instance, curbstones are not merely for sitting but also serve as mediums for play and social interaction. This multi-layered and creative mechanism of environmental perception highlights the agency and autonomy of children as active users of space.

The findings engage with Malone’s theory of “child-friendly cities” while further suggesting that in high-density urban contexts, improving the quality of micro-spaces holds greater practical significance than macro-level planning [

19]. Unlike the emphasis on “independent mobility” in Western urban contexts, child-friendly spaces in China require a more nuanced balance between safety and autonomy, as well as between efficiency and experiential quality. This insight provides an important contribution to the localization of child-friendly urban theories.

Furthermore, this study critically challenges the “adult-centric bias” in spatial design. Data indicate a significant discrepancy between what adults consider “high-quality space” (such as the expansive plaza in Case B) and children’s actual preferences. This cognitive misalignment not only reflects limitations in design methodology but also reveals the lack of children’s voice in the process of spatial production. Accordingly, this research aligns with the participatory design paradigm advocated by Derr et al., emphasizing that children should be involved as collaborators rather than passive recipients in the design process [

20].

5.2. A Framework for Design Strategies for Child-Friendly Pick-Up Spaces

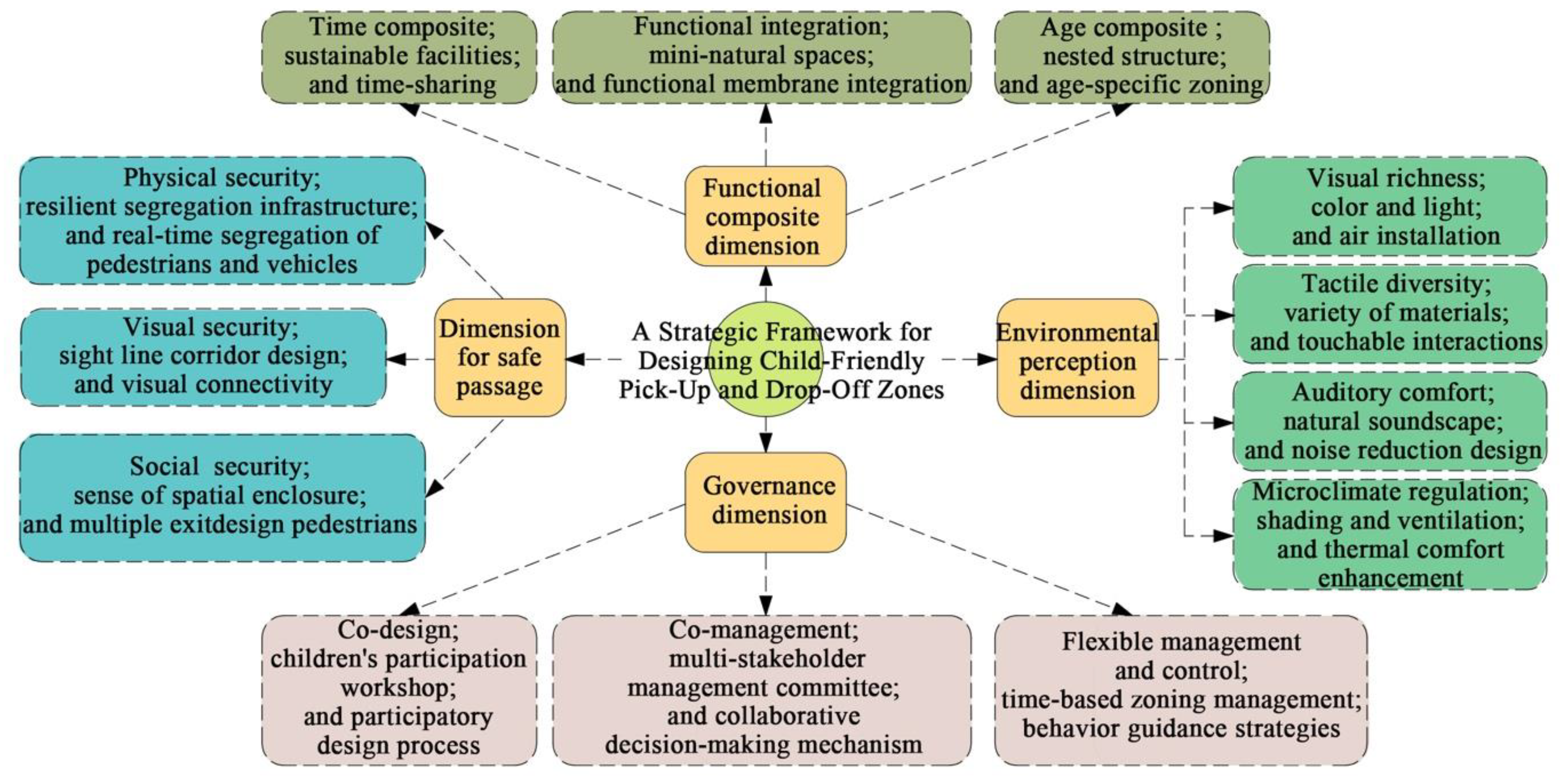

Based on the research findings, a design strategy framework comprising four dimensions is proposed (

Figure 5), with each dimension encompassing specific design principles and implementation guidelines.

5.2.1. Safety and Accessibility Dimension

Safety serves as the foundation but not the ultimate goal. A "layered safety" strategy is recommended:

(1)Physical Safety: Achieve dynamic separation between pedestrians and vehicles through resilient isolation facilities (e.g., movable planters, retractable bollards), ensuring safe passage during peak school hours while releasing space for activities at other times.

(2)Visual Safety: Maintain visual connectivity between children and caregivers through reasonable elevation changes and visual corridor design, ensuring psychological safety without creating a sense of over-surveillance [

21].

(3)Social Safety: Create an appropriately enclosed spatial atmosphere to avoid the helplessness caused by large open areas, while ensuring multiple exit options to reduce trapped anxiety.

5.2.2. Functional Complexity Dimension

Move beyond single-purpose pick-up/drop-off functions to achieve temporal sharing and functional integration of spaces:

(1) Temporal Dimension: Design convertible spatial elements, such as modular furniture that functions as waiting seats during the day and transforms into play equipment after school. Utilize paving variations and lightweight partitions to indicate dominant spatial functions across different time periods.

(2) Functional Dimension: Integrate waiting, play, social, and nature experience functions through "functional cluster" designs, forming an organic whole rather than a mere collage. The introduction of "micro-nature" spaces is particularly recommended—even in limited areas, opportunities for nature contact can be provided via vertical greening and rooftop gardens.

(3) Age-Specific Dimension: Adopt a "nested" spatial structure to provide suitable sub-spaces for different age groups: protected zones near exits for younger children, and relatively independent boundary areas for older children.

Table 6.

Guidelines for Multifunctional Design of School Pick-up and Drop-off Spaces.

Table 6.

Guidelines for Multifunctional Design of School Pick-up and Drop-off Spaces.

| Time Period |

Dominant Function |

Spatial Configuration |

Facility Status |

| Morning Peak Hours |

Rapid Transit |

Pedestrian-Vehicle Separation Mode |

Retractable Facilities Stowed |

| After-school Waiting |

Social Waiting |

Seating Deployed |

Partial Availability of Play Facilities |

| After-school Activities |

Play and Exploration |

Fully Open Mode |

Full Availability of Facilities |

| Weekends and Holidays |

Community Shared Use |

Mixed-use Mode |

On-demand Adjustment |

5.2.3. Environmental Perception Dimension

In environmental design, emphasis should be placed on the holistic creation of a multi-sensory experience [

22]. Visually, monotonous gray tones should be avoided in favor of warm and vibrant color combinations. Dynamic atmospheres can be enhanced through variations in light and shadow, along with art installations and displays of children’s creative works to increase visual richness. Tactile diversity can be achieved by incorporating various ground materials such as wood, rubber, and stone, along with interactive touchable installations and natural elements like water features, sand areas, and plants to enrich tactile experiences. Auditory environments can be improved by using natural soundscapes—such as water flows and wind chimes—to mask traffic noise, while terrain design and green buffers can help reduce noise pollution. Additionally, microclimate conditions can be regulated through strategies like tree shading, evaporative cooling from water bodies, and windbreak designs, collectively enhancing thermal comfort in the environment.

5.2.4. Participatory Governance Dimension

In terms of participatory governance, innovative spatial management models should be adopted to ensure sustainability [

23]. This can be achieved by establishing regular children’s participatory design workshops, fully integrating participatory design into the standard process of campus renewal, and forming effective co-design mechanisms. Simultaneously, a management committee comprising representatives from the school, parents, the community, and children should be established to promote collaborative decision-making regarding space use and maintenance rules, thereby enabling co-management. Furthermore, flexible control strategies—such as replacing absolute prohibitions with “temporal zoning” to clarify encouraged, permitted, or prohibited activities across different times and areas—can enhance the adaptability and operability of management.

5.3. Innovative Design Strategies in High-Density Environments

In response to the unique conditions of high-density cities in China, this study proposes the following innovative strategies:

5.3.1. Vertical Dimension Development

This strategy emphasizes transcending conventional two-dimensional planning by actively leveraging the vertical dimension for spatial development. This includes incorporating functional building façades—such as climbing walls, vertical gardens, and cantilevered play structures—as well as creating multi-level activity platforms that use elevation changes to enrich spatial experiences. Additionally, a "ground+" approach integrates underground areas, elevated walkways, and rooftops into the pickup and drop-off space network, thereby achieving efficient use of spatial resources (

Figure 6).

5.3.2. Innovation in Street Furniture

The development of street furniture should be oriented toward multifunctional and composite designs. For instance, transformable furniture can be adopted to allow waiting seats to convert into play facilities when needed. Interactive elements such as acoustic, visual, and water features should be introduced to enhance public engagement and amusement. Additionally, a modular system should be established to enable flexible combination and adjustment according to varying usage demands, thereby improving the adaptability and vitality of street spaces.

5.3.3. Activation of Boundary Spaces

The “gray space” [

24] between buildings and streets should be fully activated. Building setback areas can be designed as semi-outdoor activity zones with overhead covers to enhance spatial functionality. Structures such as eaves can be utilized to provide shelter from sun and rain, offering protective functions. By creating transitional zones that bridge indoor and outdoor environments, the sense of spatial boundaries can be softened, strengthening spatial continuity and enriching experiential layers.

Table 7.

Optimization Model of School Drop-off and Pick-up Space in High-Density Environments.

Table 7.

Optimization Model of School Drop-off and Pick-up Space in High-Density Environments.

| Space Type |

Main Characteristics |

Vertical Space Utilization Strategies |

Spatial Boundary Activation Strategies |

Spatio-Temporal Management Strategies |

| Street-adjacent Type |

Borders urban arterial roads; narrow sidewalks; severe pedestrian-vehicle mixing |

Utilize building facades for vertical greening, climbing walls, and suspended planters |

Create sheltered waiting areas in building setback zones; activate arcade spaces |

Time-based pedestrian-vehicle separation: transit mode during morning peak hours; activity mode after school |

| Street-corner Type |

Located at street intersections; space is relatively open but circulation is complex |

Install multi-level activity platforms; utilize elevation changes to create play spaces |

Design curved seating and movable planters at corners to form gathering points |

Functional switching across time slots: transit, socializing, play, community events |

| Embedded Type |

Situated within building complexes; shares space with the community; relatively poor accessibility |

Develop underground pick-up/drop-off zones, elevated corridor systems, and rooftop gardens |

Utilize corridors and eaves to create covered "grey space" for weather protection |

Shared scheduling with the community; open as children's activity grounds on weekends |

The three spatial optimization strategies for typical high-density scenarios—frontage, corner, and embedded types—each demonstrate how to maximize the value of limited space through vertical utilization, boundary activation, and time-sharing.

5.4. Policy Recommendations and Implementation Pathways

To ensure the effective implementation of the proposed design strategies, supporting policy measures and implementation mechanisms are essential:

5.4.1. Revision of Standards and Regulations

To effectively incorporate child-friendly principles into practice, systematic revisions of current design standards should be conducted, integrating relevant requirements into mandatory clauses. Specific measures include:

Adding dedicated provisions for pick-up and drop-off zones in school design standards, specifying requirements for layout, safety, and comfort;

Establishing comprehensive evaluation criteria for the surrounding school environment, incorporating children’s actual experiences and behavioral needs into the assessment system to promote more human-centered environmental development;

Developing child-adaptive design guidelines to provide clear and specific technical guidance and implementation basis for the renovation of various facilities and spaces, thereby systematically supporting the construction of a child-friendly environment from a regulatory perspective.

5.4.2. Cross-Departmental Collaboration Mechanism

The development of child-friendly campuses and surrounding environments requires multi-departmental collaboration [

25]. A joint working mechanism involving education, urban planning, and transportation management departments should be established. This includes:

Collaboratively formulating comprehensive improvement plans for school surroundings, integrating resources and management functions to systematically address traffic congestion and safety risks during peak school hours;

Incorporating school pick-up and drop-off space renovations into key urban micro-renewal project portfolios, strengthening implementation priorities and resource allocation;

Establishing a co-creation and sharing mechanism involving schools, communities, and families to encourage multi-stakeholder participation in space operation and maintenance, achieving sustainable co-governance.

5.4.3. Financial Support and Incentives

To facilitate the smooth progression of renovation projects, innovative investment and financing mechanisms should be introduced, along with strengthened financial support and policy incentives. Specific actions include:

Creating a special fund for child-friendly space renovations, prioritizing projects with high demonstrative value and significant social benefits;

Promoting public-private partnership models to diversify funding sources and enhance project construction and operational efficiency;

Establishing incentive mechanisms to provide financial rewards and public recognition for projects with notable implementation results and positive feedback from children and parents, thereby fostering a demonstrative effect and systematizing child-friendly initiatives.

5.5. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Significance

The theoretical contributions of this study are threefold:

First, it extends the application of environmental behavior theory in the context of Chinese educational spaces, particularly offering a theoretical explanation for spatial behavior changes under the Double Reduction policy.

Second, it enriches the practical implications of child-friendly city theory at the micro-level by proposing spatial design strategies suited to high-density urban conditions.

Finally, it innovates participatory design methodologies by developing a child participation framework adapted to the Chinese cultural context.

In practical terms, this study provides concrete guidance for ongoing urban renewal and school renovation projects. The proposed design strategy framework can be directly applied to design practices, and the policy recommendations serve as a reference for government decision-making. Especially amid the full implementation of the Double Reduction policy, this study timely addresses the urgent need for renovating school surrounding spaces, holding significant practical relevance.

5.6. Future Research Directions

Based on the findings and limitations of this study, future research should focus on the following areas:First, conducting long-term tracking studies to evaluate the actual usage effects and sustained impacts of design interventions;Second, expanding the research scope to include more city types and regional characteristics;Third, deepening thematic studies on specific issues, such as the spatial needs of children with special requirements and the application of digital technology in facility design;Fourth, developing assessment tools to establish a scientific evaluation system for child-adaptive spaces.

By exploring these directions, the theoretical framework and practical methodologies of child-friendly space design can be further enriched, providing continuous knowledge support for creating urban environments that truly support children’s healthy development.

6. Conclusions and Prospects

This study employs qualitative research methods to explore the child-friendly design of school drop-off and pick-up spaces within the context of the Double Reduction policy. Key findings indicate that the functional demands of these spaces have undergone a fundamental shift following policy implementation—transitioning from mere transportation exchange areas into multifunctional spaces that support social interaction, play, and exploratory activities among children. The research identifies four typical behavioral patterns (linear movement, patchy staying, social play, and exploratory behavior) and reveals complex interaction mechanisms between environmental elements and children’s behaviors.

Theoretically, this study enriches the practical implications of child-friendly city theory at the micro-level and proposes a design framework for school drop-off and pick-up spaces suitable for high-density urban environments. Findings reveal significant differences between children and adults in their perception and utilization of space, underscoring the importance of participatory design in spatial production. The research also advances the affordance theory in environmental psychology by elucidating how children creatively interpret and utilize environmental functions.

On a practical level, the design strategy framework proposed in this study offers concrete guidance for ongoing urban renewal and school renovations. It includes a four-dimensional strategy system encompassing safe accessibility, functional complexity, environmental perception, and participatory governance, which can be directly applied in design practice. Innovative strategies such as vertical development, innovative street furniture, and activation of boundary spaces—specifically tailored to high-density urban conditions—provide feasible pathways for enhancing spatial quality under limited conditions [

26].

However, this study has several limitations. First, the case selection was concentrated in the Yangtze River Delta region, and the generalizability of the conclusions to other regions requires further validation. Second, while qualitative methods allow for in-depth understanding, broader applicability of the findings needs more empirical support. Moreover, the effectiveness of participatory design methods involving children may be influenced by cultural and social contexts, necessitating further localization and adaptation.

Based on these limitations, future research could develop in the following directions: conducting cross-regional comparative studies to test and refine design strategies under different geographical conditions; carrying out long-term follow-up studies to evaluate the sustained effects and impacts of design interventions; deepening research on special groups by examining the spatial needs of children of different ages, genders, and abilities; and exploring the application of digital technologies—such as virtual reality—in participatory design processes with children.

In summary, through systematic empirical research and theoretical exploration, this study provides a theoretical foundation and practical guidance for the design of school drop-off and pick-up spaces under the Double Reduction policy. Future research should further expand and deepen these insights to collectively promote the innovative development of child-friendly urban construction.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Junshuang Sha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ChengNian Xu: Investigation, Data curation, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing finan- cial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish declaration

Not applicable. (No identifiable personal data is included.).

Consent to Participate Declaration

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. For participants under 18 years old, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians.

Ethics Declaration

This study strictly adhered to international ethical guidelines involving human participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or legal guardians of the participating children, and assent was appropriately acquired from the children themselves. Rigorous measures were implemented to ensure anonymity and confidentiality, with all personally identifiable information removed. The research design was guided by the core principles of avoiding harm and respecting children’s dignity. All activities were conducted in a safe and supportive environment, and efforts were made to ensure that the research outcomes would be returned to the school community to benefit the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

References

- X. Zhou, Y. Li, and L. Wang, “High-density urban development and its challenges for school environments in China,” Land Use Policy, vol. 105, p. 105427, 2021.

- UNICEF, Child Friendly Cities and Communities: Handbook. New York, NY, USA: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2018.

- K. Malone, Children in the Anthropocene: Rethinking Sustainability and Child Friendliness in Cities. London, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

- S. Foster, B. Giles-Corti, and M. Knuiman, “The role of neighborhood design in promoting children’s walking to school,” Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ., vol. 98, p. 102987, 2022.

- N. C. McDonald, A. E. Asgarzadeh, and A. Zhang, “Safe Routes to School: A systematic review of interventions,” J. Plan. Lit., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 432–451, 2020.

- J. J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York, NY, USA: Psychology Press, 2014.

- K. Lynch, The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2020.

- L. Chawla, “Childhood place attachment and adult environmentalism,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 75, p. 101597, 2021.

- M. Scott, “Behavior settings and urban design: A review of theory and evidence,” Cities, vol. 95, p. 102376, 2019.

- R. A. Hart, Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care. London, U.K.: Routledge, 1997.

- M. Francis and R. Lorenzo, “Children and city design: Proactive process,” Environ. Behav., vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 495–523, 2021.

- R. K. Yin, Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, 2018.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, 2022.

- M. B. Miles, A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña, Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, 2020.

- J. Zeisel, Inquiry by Design: Environment/Behavior/Neuroscience in Architecture, Interiors, Landscape, and Planning. New York, NY, USA: Norton & Company, 2022.

- D. Silverman, Doing Qualitative Research, 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, 2021.

- J. Gehl, Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Washington, DC, USA: Island Press, 2019.

- R. Kaplan and S. Kaplan, The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- K. Malone, “Children, youth and sustainable cities,” Local Environ., vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 803–811, 2021.

- V. Derr, L. Chawla, and M. Mintzer, Placemaking with Children and Youth: Participatory Practices for Planning Sustainable Communities. New York, NY, USA: New Village Press, 2018.

- B. Appleyard, Livable Streets, 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press, 2020.

- J. Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

- H. Sanoff, Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2022.

- K. Lynch, Good City Form. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2020.

- T. Beatley, Handbook of Biophilic City Planning & Design. Washington, DC, USA: Island Press, 2020.

- J. Gehl, Cities for People. Washington, DC, USA: Island Press, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).