Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

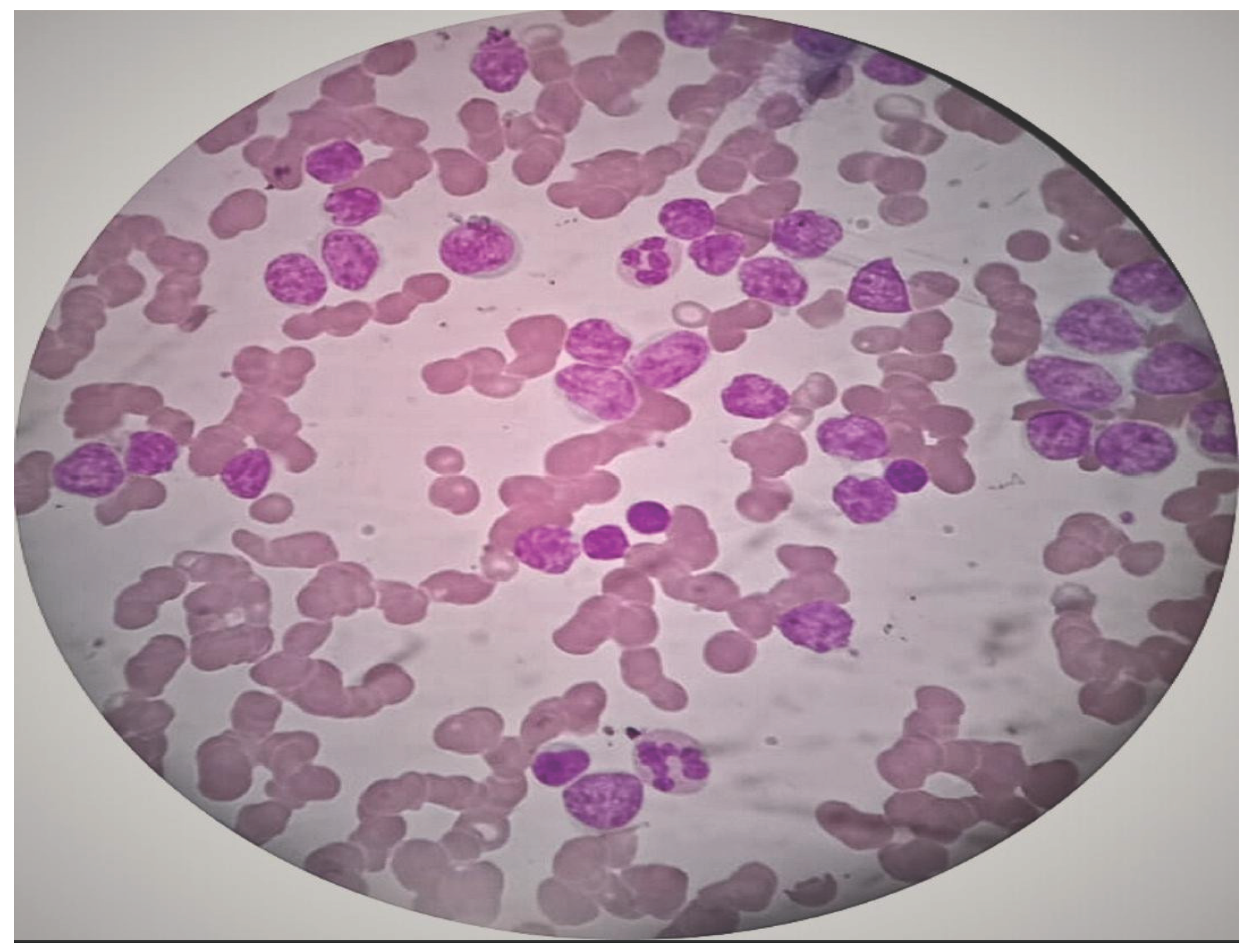

2. Case Presentation

| Test Name | Results | Units | Bio. Ref. Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEUKEMIA DIAGNOSTIC PANEL (Flow Cytometry) | |||

| MARKERS | RESULT (%) | INTENSITY | INTERPRETATION |

| T cell markers | |||

| CD3 (cyto) | 3.8 | Negative | Negative |

| CD5 | 20.2 | Dim pos | Positive |

| CD7 | 11.9 | Negative | Negative |

| B cell markers | |||

| CD19 | 94.0 | Moderate | Positive |

| CD20 | 4.6 | Negative | Negative |

| CD22 | 52.6 | Dim to mod | Positive |

| CD22 (cyto) | 23.4 | Dim pos | Positive |

| CD79a (cyto) | 96.8 | Mod to bright | Positive |

| CD58 | 71.1 | Dim to mod | Positive |

| Myeloid markers | |||

| CD13 | 64.0 | Partial dim to mod | Positive |

| CD15 | 0.4 | Negative | Negative |

| CD33 | 56.0 | Partial dim to mod | Positive |

| CD66c | 0.0 | Negative | Negative |

| MPO | 5.1 | Negative | Negative |

| Precursor markers | |||

| CD34 | 36.8 | Dim to mod | Positive |

| CD117 | 0.2 | Negative | Negative |

| TdT | 89.6 | Moderate | Positive |

| CD99 | 98.8 | Moderate | Positive |

| Other markers | |||

| CD45 | 99.3 | Dim pos | Positive |

| CD9 | 3.1 | Negative | Negative |

| CD10 | 97.9 | Mod to bright | Positive |

| HLA-DR | 96.4 | Mod to bright | Positive |

| CD38 | 94.1 | Dim to mod | Positive |

3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

References

- Vakiti A, Reynolds SB, Mewawalla P. Acute Myeloid Leukemia. [Updated 2024 Apr 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Key statistics for acute lymphocytic leukemia [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sept 21]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html?

- Blick C, Nguyen M, Jialal I. Thyrotoxicosis. [Updated 2025 Jan 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482216/?

- JIANG, YAJIAN, KEYUE HU, WANZHUO XIE, et al. 2014. “Hyperthyroidism with Concurrent FMS-like Tyrosine Kinase 3-Internal Tandem Duplication-Positive Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature.” Oncology Letters 7 (2): 419–22. [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, Komal, Ralph Emerson, Girish Kumar Parida, Prapti Acharya, Somanath Padhi, and Kanhaiyalal Agrawal. 2023. “Acute Myeloid Leukemia Following Radioactive Iodine Therapy for Metastatic Follicular Carcinoma of the Thyroid.” Indian Journal of Nuclear Medicine 38 (1): 56–58. [CrossRef]

- Nehara HR, Gupta BK, Parmar S, Kumar V, and Sihag D, Beniwal S. 2025. “(PDF) Antithyroid Drug-Induced Pancytopenia Followed by Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Rare Case.” ResearchGate, ahead of print, May 24. [CrossRef]

- Oka, Satoko, Taiji Yokote, Tetuya Hiraiwa, et al. 2006. “Hyperthyroidism Associated With Philadelphia-Chromosome-Positive–Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 24 (21): 3500–3502. [CrossRef]

- Tsabouri, S. E., A. Tsatsoulis, Chr. Giannoutsos, and K. L. Bourantas. 2000. “Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia Presenting as an Enlarged Goitre in a Pregnant Woman with Graves’ Disease.” European Journal of Haematology 65 (1): 84–85. [CrossRef]

- Niles, Denver, Juri Boguniewicz, Omar Shakeel, et al. 2019. “Candida Tropicalis Thyroiditis Presenting With Thyroid Storm in a Pediatric Patient With Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia.” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 38 (10): 1051–53. [CrossRef]

- Fadlalbari, Ghassan Faisal, Samar Sabir Hassan, Asmahan T Abdallah, Samar Omer Abusamra, Abeer Mohamed Abdalrhman, and Mohamed Ahmed Abdullah. 2021. “Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Complicating Graves’ Disease in a Sudanese Adolescent Girl: A Case Report and Exploration of the Underlying Mechanism Possibilities.” Preprint, In Review, August 18. [CrossRef]

- Perillat-Menegaux, Florence, Jacqueline Clavel, Marie-Françoise Auclerc, et al. 2003. “Family History of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease and Childhood Acute Leukemia1.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 12 (1): 60–63.

- Thomson, John A. 1963. “ACUTE LEUKÆMIA FOLLOWING ADMINISTRATION OF RADIOIODINE FOR THYROTOXICOSIS.” The Lancet 282 (7315): 978–79. [CrossRef]

- Al-Anazi, Khalid A., Sohail Inam, MT Jeha, and R Judzewitch. 2005. “Thyrotoxic Crisis Induced by Cytotoxic Chemotherapy.” Support Care Cancer 13 (3): 196–98. PubMed (15459765). [CrossRef]

- McBride, J. A. 1964. “Acute Leukaemia After Treatment for Hyperthyroidism with Radioactive Iodine.” British Medical Journal 2 (5411): 736.

- Aksoy, Muzaffer, Sakir Erdem, Hikmet Tezel, and Tuna Tezel. 1974. “ACUTE MYELOBLASTIC LEUKÆMIA AFTER PROPYLTHIOURACIL.” The Lancet 303 (7863): 928–29. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, John E., Jr. 1962. “Acute Myelomonocytic Leukemia After Radioiodine Therapy of Hyperthyroidism.” JAMA 179 (7): 572–73. [CrossRef]

- Imai, Chihaya, Toshio Kakihara, Akihiro Watanabe, et al. 2002. “ACUTE SUPPURATIVE THYROIDITIS AS A RARE COMPLICATION OF AGGRESSIVE CHEMOTHERAPY IN CHILDREN WITH ACUTE MYELOGENEOUS LEUKEMIA.” Pediatric Hematology and Oncology 19 (4): 247–53. [CrossRef]

- Kolade, Victor O., Timothy J. Bosinski, and Enrico L. Ruffy. 2005. “Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia After Iodine-131 Therapy for Graves’ Disease.” Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy 25 (7): 1017–20. [CrossRef]

- Fadilah, SAW, I Faridah, and S K Cheong. 2000. Transient Hyperthyroidism Following L-Asparaginase Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. 55 (4).

- Laurenti, L., P. Salutari, S. Sica, et al. 1998. “Acute Myeloid Leukemia after Iodine-131 Treatment for Thyroid Disorders.” Annals of Hematology 76 (6): 271–72. [CrossRef]

- McCormack, Kenneth R., and Glenn E. Sheline. 1963. “LEUKEMIA AFTER RADIOIODINE THERAPY FOR HYPERTHYROIDISM.” California Medicine 98 (4): 207–9.

- Burns, Thomas W. 1960. “Acute Leukemia After Radioactive Iodine (I131) Therapy for Hyperthyroidism.” Archives of Internal Medicine 106 (1): 97. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, William M., and Robert G. Fish. 1959. “Acute Granulocytic Leukemia after Radioactive-Iodine Therapy for Hyperthyroidism.” New England Journal of Medicine 260 (2): 76–77. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, Lalchand, and Sandeep Jasuja. 2025. “Carbimazole-Induced Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Very Rare Case Report and Review of the Literature.” Indian Journal of Cancer 62 (1): 142–44. [CrossRef]

- Khanna G, Damle NA, Agarwal S, et al. Mixed Phenotypic Acute Leukemia (mixed myeloid/B-cell) with Myeloid Sarcoma of the Thyroid Gland: A Rare Entity with Rarer Asssociation - Detected on FDG PET/CT. Indian J Nucl Med. 2017;32(1):46-49. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg D, Joshi M, Malysz J, Claxton D, Cottrill EE. Myeloid sarcoma of the thyroid. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96(12):460-461.

- Hemminki, Kari, Wuqing Huang, Jan Sundquist, Kristina Sundquist, and Jianguang Ji. 2020. “Autoimmune Diseases and Hematological Malignancies: Exploring the Underlying Mechanisms from Epidemiological Evidence.” Autoimmune Disease and Comorbidity 64 (August): 114–21. [CrossRef]

- Umesono, Kazuhiko, Vincent Giguere, Christopher K. Glass, Michael G. Rosenfeld, and Ronald M. Evans. 1988. “Retinoic Acid and Thyroid Hormone Induce Gene Expression through a Common Responsive Element.” Nature 336 (6196): 262–65. [CrossRef]

- Dayton, A. I, J R Selden, G Laws, et al. 1984. “A Human C-erbA Oncogene Homologue Is Closely Proximal to the Chromosome 17 Breakpoint in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 81 (14): 4495–99. [CrossRef]

- Stunnenberg, Hendrik G., Custodia Garcia-Jimenez, and Joan L. Betz. 1999. “Leukemia: The Sophisticated Subversion of Hematopoiesis by Nuclear Receptor Oncoproteins.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1423 (1): F15–33. [CrossRef]

- Graupner, Gerhart, Ken N. Wills, Maty Tzukerman, Xiao-kun Zhang, and Magnus Pfahl. 1989. “Dual Regulatory Role for Thyroid-Hormone Receptors Allows Control of Retinoic-Acid Receptor Activity.” Nature 340 (6235): 653–56. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Vanessa E., and Catherine C. Smith. 2020. “FLT3 Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Key Concepts and Emerging Controversies.” Frontiers in Oncology Volume 10-2020. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.612880.

| Parameter | Value | Units | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 8.9 | g/dl | 12–16 (F), 13–17 (M) |

| Total Leukocyte Count (TLC) | 185,290 | /mm3 | 4,000–11,000 |

| Red Blood Cells (RBC) | 4.05 | million/mm3 | 4.2–5.4 (F), 4.7–6.1 (M) |

| Packed Cell Volume (PCV) | 28.9 | % | 36–46 (F), 40–54 (M) |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) | 71.4 | fL | 80–100 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) | 22 | pg | 27–32 |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration | 30.8 | g/dl | 32–36 |

| Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW) | 22.7 | % | 11.5–14.5 |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate | 40 | mm/hr | <20 (M), <30 (F) |

| Total Bilirubin | 0.7 | mg/dl | 0.3–1.2 |

| Direct Bilirubin |

0.4 | mg/dl | <0.3 |

| AST (SGOT) | 22 | U/L | 5–40 |

| ALT (SGPT) |

11 | U/L | 5–45 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | 96 | U/L | 44–147 |

| Total Protein | 7.7 | g/dl | 6.0–8.3 |

| Albumin | 3.5 | g/dl | 3.5–5.0 |

| Gamma Glutamyl Transferase(GGT) | 31 | U/L | 9–48 (M), 8–35 (F) |

| Urea | 20 | mg/dl | 15–40 |

| Creatinine | 0.9 | mg/dl | 0.6–1.3 |

| Uric Acid | 9.2 | mg/dl | 3.5–7.2 (M), 2.6–6.0 (F) |

| Sodium (Na+) | 131 | mmol/L | 135–145 |

| Potassium (K+) | 3.7 | mmol/L | 3.5–5.0 |

| Chloride (Cl−) | 99 | mmol/L | 98–106 |

| Test | Result | Reference/Normal Range | |

| Iron Profile | |||

| Serum Iron | 42 | 60 – 170 µg/dL | |

| TIBC | 220 | 240 – 450 µg/dL | |

| UIBC | 177 | 150 – 375 µg/dL | |

| Transferrin saturation | 19% | 20 – 50% | |

| Ferritin | Not reported | ||

| Vitamin Profile | |||

| Vitamin B12 | 481 | 200 – 900 pg/mL | |

| Folic Acid | 1.4 | 2.7 – 17 ng/mL | |

| Hematology | |||

| Reticulocyte count | 0.8 % | 0.5 – 1.5 % | |

| Corrected Reticulocyte Count | 0.34 % | 0.5 – 1.5 % | |

| Platelet | Pending | 150 – 400 ×109/L | |

| PCV | Pending | 36 – 46 % | |

| Serology | |||

| HIV | Negative | Negative | |

| HBsAg | Negative | Negative | |

| HEV | Negative | Negative | |

| VDRL | Pending | Negative |

| Test | Result | Normal/Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Urinalysis | ||

| Specific Gravity | 1.010 | 1.005 – 1.030 |

| pH | 7 | 4.6 – 8.0 |

| Protein | Trace | Nil / Negative |

| Glucose | Nil | Nil / Negative |

| Ketone | Nil | Nil / Negative |

| Urobilinogen | Normal | Normal |

| Bilirubin | Nil | Nil / Negative |

| Microscopy | ||

| Pus cells | 1 /hpf | 0–5 /hpf |

| Epithelial cells | 1 /hpf | 0–5 /hpf |

| RBC | Nil | 0–2 /hpf |

| Casts | Nil | Negative |

| Crystals | Nil | Negative |

| Nitrite | Nil | Negative |

| Leukocyte esterase | Nil | Negative |

| Other tests | ||

| Dengue | Negative | Negative |

| Malaria | Negative | Negative |

| Sl no. | AUTHOR | Country | Age | Type of Hyperthyroidism |

Treatment Received |

Type Of Acute Leukemia |

Treatment Received For Leukemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jiang et al. [5] | China | 42/ M | The patient was initially treated with propylthiouracil (PTU) at the time of diagnosis; however, due to drug-induced leukopenia, the therapy was switched to methimazole (MMI) in 2010 | M3 leukemia harboring the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication. |

ATRA (25 mg/m 2 /d, per os) |

|

| 2 | Bishnoi et al. [6] | India | 52/ F | Follicular thyroid carcinoma | The patient underwent a total thyroidectomy in 2011. Between 2012 and 2016, she received 8 cycles of radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy (200 mCi per cycle), with a cumulative dose of 1600 mCi. Subsequently, she was given palliative radiotherapy foran L4 spinal metastasis | AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (WHO category II) as per the 2017 revised WHO classification | N/A |

| 3 | Nehara et al. [7] | India | 26/M | Graves disease | The patient was started on carbimazole 20 mg twice daily and propranolol 40 mg three times daily, followed by radioiodine ablation after achieving remission from acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | ALL with 85% blasts |

Multicentric protocol (MCP 841) chemotherapy for 2.5 years (Oka et al. 2006) |

| 4 | Oka S et al. [8] | Japan | 35/M | D/t to metastatic involvement | N/A | Philadelphiaa-chromosome-PPositive– acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | chemotherapy for ALL with lenograstim 5g/kg per day by subcutaneous injection |

| 5 | Tsabouri et al. [9] | Greece | 24/F Pregnant |

Graves’ disease | She was initially managed with carbimazole, which was later switched to propylthiouracil 50 mg/day during her pregnancy | Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) |

Chemotherapy and 18 months later, achieved complete haematologic remission. Her current maintenance therapy for ALL |

| 6 | Niles D et al. [10] |

USA | 15/ M | Candia tropicalis thyroiditisisis | Started on methimazole, followed by propylthiouracil and eventually thyroidectomy after 9 weeks of treatment. | Acute lymphocytic leukemia | Induction chemotherapy with vincristine, daunorubicin, polyethylene glycol-asparaginase, and intrathecal methotrexate |

| 7 | Fadlalbari et al. [11] |

SUDAN | 16/F | Graves’ disease | The patient was initially started on carbimazole, and after 14 months, was transitioned to levothyroxine due to the development of hypothyroidism | ALL | N/A(Perillat-Menegaux et al. 2003) |

| 8 | Perillat-Menegaux F et al. [12] | France | Autoimmune thyroid diseases (Graves’ disease and/or hyperthyroidism and Hashimoto’s disease, and/or hypothyroidism) | N/A | ALL ANLL |

N/A | |

| 9 | Thomson [13] | Edinburgh | 40/ F | Thyrotoxicosis | Radioiodine therapy | Acute leukemia | treated with prednisone 40 mg daily and 6-mercaptopurine 50 mg. t.i.d. (Al-Anazi et al. 2005) |

| 10 | Al-Anazi et al. [14] |

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 25/F | Thyrotoxic crisis occurring in a patient with Graves’ disease induced by the course of chemotherapy given earlier. | The patient was started on carbimazole 20 mg twice daily, atenolol 100 mg per day, and hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenously, followed by 100 mg IV every 6 hours. By September 7, the thyrotoxic features had slightly improved; however, tachycardia had worsened with a pulse rate of 130/min. Consequently, the atenolol dose was increased to 600 mg/day, while the carbimazole dose was adjusted to 40 mg/day. | Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML, M2 type) | Induction course of chemotherapy (3+7 protocol) composed of cytarabine (Ara-C, Cytosar) 100 mg/m2 i.v. daily for 7 days and daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 i.v. daily for 3 days. |

| 11 | McBride [15] |

Edinburgh | 64/F | N/A | Carbimazole followed by radioactive iodine | Acute leukemia | Prednisolone 60mg followed by 6 6-mercaptopurine 100mg daily |

| 12 | Aksoy et al. [16] |

Istanbul, Turkey | 74/F | Grave’s disease | Propylthiouracil | Acute myeloblastic leukemia | Corticosteroid, mercaptopurine, vincristine |

| 13 | Johnson et al. [17] |

Texas | 55/M | Diffuse toxic goiter with congestive heart failure. | Methimazole and reserpine, followed by radioactive iodine | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | N/A |

| 14 | Imai et al. [18] |

Niigata, Japan |

11/M 14/F |

Acute suppurative Thyroiditis with bacterial etiology Acute suppurative Thyroiditis with bacterial etiology |

Clindamycin Clindamycin |

AML (FAB classification: M1) AML (FAB classification: M2) |

High- does cytarabine (AraC) and etoposide (ETP) with intrathecal injection of methotrexate (MTX), AraC, and hydrocortisone (HDC), pirarubicin, vincristine, and 5 days’ continuous infusion of AraC |

| 15 | Kolade et al. [19] |

New york | 47/M | Graves disease | Propylthiouracil, propranolol, followed by radioactive iodine | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | All trans retinoic acid with anthracycline-based chemotherapy |

| 16 | Fadilah et al. [20] |

Kuala lumpur | 18/M 52/M |

Transient hyperthyroidism Transient hyperthyroidism |

No anti-thyroid therapy No anti-thyroid therapy |

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

L asparginase L asparginase |

| 17 | Laurenti et al. [21] | Italy | 48/F 44/F |

Nodular thyroid Medullary thyroid carcinoma |

Radioiodine therapy Radioiodine therapy |

AML M2, AML M6 |

Mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 days 1, 3, and 5, VP16 100 mg/m2 days 1–5, and cytosine arabinoside 100 mg/m2 days 1–10. Complete remission was achieved, and consolidation chemotherapy- motherapy with mitoxantrone 12 mg/m2 days 4, 5, and 6 and cytosine arabinoside 500 mg/m2 days 1–6. Not considered eligible for aggressive chemotherapy |

| 18 | McCormack et al. [22] | San Francisco | 48/M | Radioiodine therapy | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | N/A | |

| 19 | Burns et al. [23] | Missouri | 65/M 64/F |

Graves disease Goiter |

Radioiodine therapy | Acute monocytic leukemia | Prednisone, 20 mg per day, |

| 20 |

Kennedy et al. [24] | North Carolina | 38/M | Radioiodine therapy | Acute granulocytic leukemia | N/A | |

| 21 | Mittal et al. [25] | India | 34/M | Thyrotoxicosis | Carbimazole | Acute myeloid leukemia | Induction chemotherapy (daunorubicin and cytarabine) for 7 days and three cycles of high-dose cytarabine chemotherapy as consolidation chemotherapy. |

| 22 |

Khanna et al. [26] |

India | 58/F |

Clinically and biochemically euthyroid. Midline neck swelling that moved with deglutition. |

Mixed phenotypic Acute leukemia (mixed myeloid/B/B/cell) with myeloid sarcoma, involving the thyroid gland |

Hoelzer’s protocol, comprising daunorubicin, vincristine, methylprednisolone, and L-asparaginase, along with intrathecal methotrexate. |

|

| 23 | Dana Goldenberg et al. [27] | USA | 48/F | Myeloid sarcoma of the thyroid | Cladribine, cytarabine, and filgrastim with mitoxantrone |

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) |

Allogeneic stem cell transplant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).