Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

Instruments

Data Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Comparison Between Majority and Minority Ethnic Groups

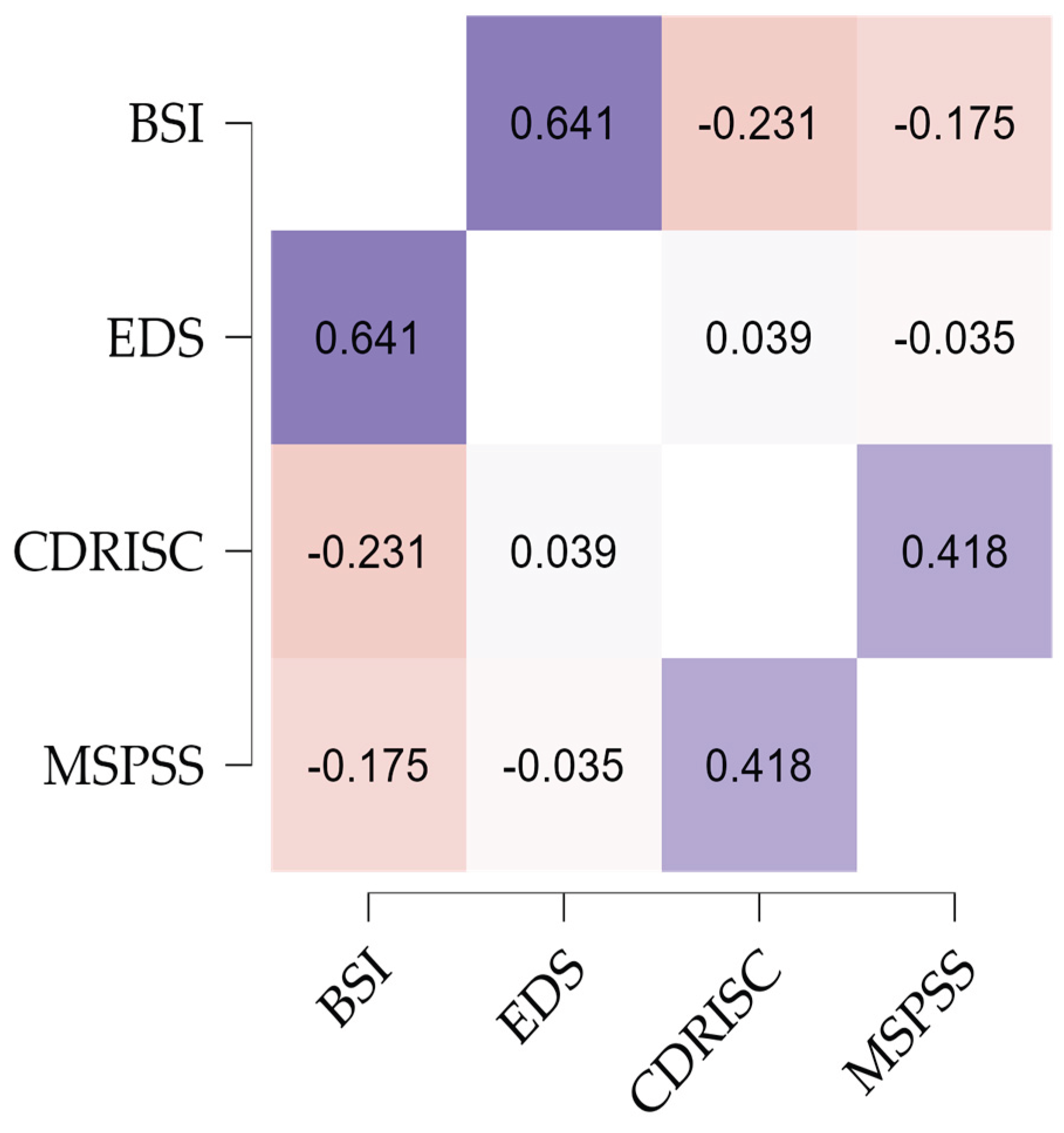

Correlations Between Psychological Distress, Social Discrimination, Perceived Social Support, and Resilience

Predictive Effect of Independent Variables on Psychological Distress

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gee, G.C.; Hing, A.; Mohammed, S.; Tabor, D.C.; Williams, D.R. Racism and the life course: Taking time seriously. Am J Public Health 2019, 109(S1), 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Bhopal, R.; Netto, G.; Lyons, D.; Steiner, M.F.; Sashidharan, S.P. Disparate patterns of hospitalisation reflect unmet needs and persistent ethnic inequalities in mental health care: The Scottish Health and Ethnicity Linkage Study. Ethnicity Health. 2014, 19, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Karlsen, S.; Sashidharan, S.P.; Cohen, R.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Malpass, A. Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: A meta-ethnography. PLoS Med. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, P.; Mackay, E.; Matthews, H.; Gate, R.; Greenwood, H.; Ariyo, K. Ethnic variations in compulsory detention under the Mental Health Act: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019, 6, 30027–30033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K.; Halvorsrud, K.; Nazroo, J. Making a difference: Ethnic inequality and severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2018, 213, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.; Amartey, A.; Wang, X.; Kurdyak, P. Ethnic differences in mental health status and service utilization: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018, 63, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsrud, K.; Nazroo, J.; Otis, M.; Hajdukova, E.B.; Bhui, K. Ethnic inequalities in the incidence of diagnosis of severe mental illness in England: A systematic review and new meta-analyses for non-affective and affective psychoses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prady, S.L.; Pickett, K.E.; Gilbody, S.; Petherick, E.S.; Mason, D.; Sheldon, T.A. Variation and ethnic inequalities in treatment of common mental disorders before, during and after pregnancy: Combined analysis of routine and research data in the Born in Bradford cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.; Jayaweera, H.; Redshaw, M.; Quigley, M. Migration, ethnicity, and mental health: Evidence from mothers participating in the Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health 2019, 171, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponizovsky, A.M.; Haklai, Z.; Goldberger, N. Association between psychological distress and mortality: The case of Israel. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018, 72, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, N.; Marzban, M.; Sebar, B.; Harris, N. Perceived discrimination and subjective well-being among Middle Eastern migrants in Australia: The moderating role of perceived social support. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021, 67, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, C.; Liebau, E.; Mühlau, P. How often have you felt disadvantaged? Explaining perceived discrimination. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 2021, 73, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnois, C.E. Are perceptions of discrimination unidimensional, oppositional, or intersectional? Examining the relationship among perceived racial-ethnic, gender-, and age-based discrimination. Sociol Perspect. 2014, 57, 470–487. [Google Scholar]

- Semu, L.L. The intersectionality of race and trajectories of African women into the nursing career in the United States. Behav Sci 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauderdale, D.S.; Wen, M.; Jacobs, E.A.; Kandula, N.R. Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: The California Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 2003, 44, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Abelsen, B.; Olsen, J.A. Clarifying associations between childhood adversity, social support, behavioral factors, and mental health, health, and well-being in adulthood: A population-based study. Front Psychol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Liebkind, K.; Perhoniemi, R. Perceived discrimination and well-being: A victim study of different immigrant groups. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2006, 16, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.O.; Melle, I.; Rossberg, J.I.; Romm, K.L.; Larsson, S.; Lagerberg, T.V. Perceived discrimination is associated with severity of positive and depression/anxiety symptoms in immigrants with psychosis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.N.; Carlo, G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I. The longitudinal associations between discrimination, depressive symptoms, and prosocial behaviors in U. S. Latino/a recent immigrant adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, C.; Tagliabue, S.; Regalia, C. Psychological well-being, multiple identities, and discrimination among first- and second-generation immigrant Muslims. Eur J Psychol. 2018, 14, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezsar, C.M.; Mcgrath, J.J.; Herzig, A.J.M.; Miller, S.B. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Z.; Maqsood, M.H.; Yahya, T.; Amin, Z.; Acquah, I.; Valero-Elizondo, J. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardio- vascular disease. Circulation Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.; Risica, P.M.; Gans, K.M.; Kirtania, U.; Kumanyika, S.K. Association of perceived racial discrimination with eating behaviors and obesity among participants of the SisterTalk study. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2012, 23, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Junior, O.L.; Do, A.; Menegazzo, G.R.; Fagundes, M.L.B.; Sousa, J.L.D.; Torres, L.H.; Do, N.; Giordani, J.M.; Do, A. Perceived discrimination in health services and preventive dental attendance in Brazilian adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, G.; Newbold, K.B.; Lafrenière, G.; Edge, S. Discrimination in the doctor’s office: Immigrants and refugee experiences. Crit Soc Work. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski, T.C.B.; Rowe, A.T.; Banks, D.E.; Faidley, M. Perceived discrimination and substance use among adolescents: Examining the moderating effect of distress tolerance and negative urgency. Subst Use Misuse. 2019, 54, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, E.A.; Richman, L.S. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.L.; Sørlie, T. Ethnic discrimination and psychological distress: A study of Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012, 49, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Oluboyede, R.W.; Jewison, J.; House, A.O. The factor structure of the GHQ-12: The interaction between item phrasing, variance and levels of distress. Qual Life Res. 2013, 22, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romppel, M.; Braehler, E.; Roth, M.; Glaesmer, H. What is the general health questionnaire-12 assessing? Dimensionality and psychometric properties of the general health questionnaire-12 in a large-scale German population sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2013, 54, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deasy, C.; Coughlan, B.; Pironom, J.; Jourdan, D.; Mannix-Mcnamara, P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: A mixed method enquiry. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.R. [Title missing]. 2009. p. 91–92.

- Caron, J.; Fleury, M.J.; Perreault, M.; Crocker, A.; Tremblay, J.; Tousignant, M.; et al. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal south-west. BMC Psychiatry. 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Mansbach-Kleinfeld, I.; Abu-Kaf, S.; Ifrah, A.; Sheikh-Muhammad, A. Correlates of psychological distress and self-rated health among Palestinian citizens of Israel: Findings from the Health and Environment Survey (HESPI). Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Loureiro, A.; Cardoso, G. Social determinants of mental health: A review of the evidence. Eur J Psychiatry. 2016, 30, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, L.; Brown, K.; Quinn, T. Analyzing community resilience as an emergent property of dynamic social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc. 2018, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, M.; Monacelli, N.; Cocimano, L. Promotion of resilience in migrants: A systematic review of study and psychosocial interven- tion. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022, 24, 1328–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.; Ruiz, L.L.; Gracia, M. ; M Resilience and integration: Analysis of the influence of resilience on immigrant integration. J Immigr Refuge Stud. 2019, 17, 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V. Resilience in immigrant populations. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Ramírez, M.G.; Castillo, J.D.D.; Estévez, A. Resilience in adult immigrants: Protective and risk factors. J Soc Psychol. 2018, 33, 421–453. [Google Scholar]

- Javdani, S.; Allen, J.G.; Elsayed, N. Resilience and psychological well-being among young immigrants: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2019, 50, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- López, T.T.; Viladrich, C.; Cruz, J.; Carrasco, P. Identity and resilience in second-generation immigrants: The role of ethnic and cultural identity. J Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 1625–1641. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xie, T.; Li, W.; Tao, Y.; Liang, P.; Zhao, Q. The relationship between perceived discrimination and wellbeing in impoverished college students: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and belief in a just world. Curr Psychol. 2023, 42, 6711–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara, C.; Abbate, C.S.; Garro, M.; Lavanco, G. The welfare of immigrants: Resilience and sense of community. J Prev Interv Community. 2021, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sang, Z.; Zhang, X.-C.; Margraf, J. The relationship between resilience and mental health in Chinese college students: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Front Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Shinar, O. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford University Press; 2000.

- Sharp, P.; Oliffe, J.L.; Kealy, D.; Rice, S.M.; Seidler, Z.E.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. Social support buffers young men’s resilient coping to psychological distress. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023, 17, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Abelsen, B.; Olsen, J.A. Clarifying associations between childhood adversity, social support, behavioral factors, and mental health, health, and well-being in adulthood: A population-based study. Front Psychol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, R.; Johnson, D.J.; De, V.; Vijver, F.J.R. Ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, life satisfaction, and school achievement of Roma ethnic minority youth. J Adolesc. 2018, 62, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, Q.-L.; Devos, T.; Goldberg, R. The role of ethnic and national identifications in perceived discrimination for Asian Americans: Toward a better understanding of the buffering effect of group identifications on psychological distress. Asian Am J Psychol. 2014, 5, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspal, R.; Lopes, B. Discrimination and mental health outcomes in British Black and South Asian people during the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2021, 24, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.S.; Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, R.J. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among Black Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995, 50, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Aziz, I.A.; Vostanis, P.; Hassan, M.N. Associations among resilience, hope, social support, feeling belongingness, satisfac- tion with life, and flourishing among Syrian minority refugees. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2022, 22, 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Hirst, G. Mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and wellbeing of refugees. Int Migr. 2018, 56, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Liebkind, K.; Jaakkola, M.; Reuter, A. Perceived discrimination, social support networks, and psychological well-being among three immigrant groups. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2006, 37, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. 2001.

- Canavarro, M.C.; Pereira, M. BSI - Psychopathological Symptom Inventory: Short version (BSI-18). In: S., Machado C, Gonçalves MM, Almeida LS, editors. Psychological assessment: Validated instruments for the Portuguese population. Vol. 3. Quarteto Editora; 2007. p. 109–130.

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Pimentel, P.; Maia, D. Mota-Pereira J. Psychometric characteristics of the Portuguese version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Psychologica 2011, 54, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, D.; Gato, J.; Petrocchi, N.; Carreiras, D.; Azevedo, J.; Martins, L.; Salvador, M.D. Everyday Discrimination Scale: Dimensionality in a Portuguese community sample and specific versions for sexual and gender minorities. Curr Psychol. 2023:1-12.

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Statistics. Survey on Living Conditions, Origins, and Trajectories of the Resident Population 2023. Available from: https://www.ine.pt/ngt_server/attachfileu.jsp?att_display=n&;att_download=y&;look_parentBoui=680073092.

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1988.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 2014.

- Berger, R.; Rahav, G.; Ronen, T.; Roziner, I.; Savaya, R. Ethnic density and psychological distress in Palestinian Israeli adolescents: Mediating and moderating factors. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2020, 37, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Kang, E. Informal and formal support as moderators between racial discrimination and mental distress among Black, Asian, and Latino Americans. Front Psychol. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shaheen, M. Impact of minority perceived discrimination on resistance to innovation and moderating role of psychological distress: Evidence from ethnic minority students of China. Front Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, C.; O’connor, R.C.; Howe, C.; Warden, D. Perceived discrimination and psychological distress: The role of personal and ethnic self-esteem. J Couns Psychol. 2004, 51, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcsorley, K.; Bacong, A.M. Associations between socioeconomic status and psychological distress across Latinx subgroups: The unequal role of education and income. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023, 20, 4751–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuru-Jeter, A.M.; Williams, C.T.; Laveist, T.A. A methodological note on modeling the effects of race: The case of psychological distress in low-income urban African Americans. Stress Health. 2008, 24, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Ethnic Majority (n=609, 80.56%) |

Ethnic Minority (n=147, 19.44%) |

Total sample(n=756, 100%) | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | p | Cramer’s V | ||

| Gender | Men | 183 | 30 | 93 | 63.3 | 276 | 36.5 | 56,690 | <.001 | .274 |

| Women | 422 | 66.3 | 54 | 36.7 | 476 | 63 | ||||

| Sexual orientation | Straight | 540 | 88.8 | 127 | 86.4 | 667 | 88.2 | .590 | .442 | .028 |

| LGBTQIA+ | 69 | 11.3 | 20 | 13.6 | 89 | 11.8 | ||||

| Marital Status |

Single/Not dating | 139 | 22.8 | 32 | 21.8 | 171 | 22.6 | 10.95 | .027 | .120 |

| Single/Dating | 140 | 23 | 34 | 23.1 | 174 | 23 | ||||

| Married / Cohabitation | 271 | 44.5 | 75 | 51 | 346 | 45.8 | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | 51 | 8.4 | 2 | 1.4 | 53 | 7 | ||||

| Widow | 8 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.7 | 12 | 1.6 | ||||

| Children | No | 312 | 51.2 | 68 | 46.3 | 380 | 50.3 | 1,171 | .279 | .039 |

| Yes | 297 | 48.8 | 79 | 53.7 | 376 | 49.7 | ||||

| Number of children | 1 | 125 | 41.8 | 5 | 6.4 | 130 | 34.6 | 78.64 | .001 | .459 |

| 2 | 130 | 43.5 | 30 | 38.5 | 160 | 42.6 | ||||

| 3 | 27 | 9 | 27 | 34.6 | 54 | 14.4 | ||||

| 4 | 8 | 2.7 | 12 | 15.4 | 20 | 5.3 | ||||

| 5 or more | 8 | 2.7 | 4 | 5.1 | 12 | 3.2 | ||||

| Education | Up to 4 years | 3 | 0.5 | 8 | 5.4 | 11 | 1.5 | 187.66 | .001 | .498 |

| Up to 6 years | 9 | 1.5 | 20 | 13.6 | 29 | 3.8 | ||||

| Up to 9 years | 25 | 4.1 | 42 | 28.6 | 67 | 8.9 | ||||

| Up to 12 years | 135 | 22.2 | 40 | 27.2 | 175 | 23.1 | ||||

| Degree | 235 | 38.6 | 20 | 13.6 | 255 | 33.7 | ||||

| Master’s Degree | 201 | 33 | 17 | 11.6 | 218 | 28.8 | ||||

| Other | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Household | 1 | 84 | 13.8 | 9 | 6.1 | 93 | 12.3 | 203.34 | .001 | .519 |

| 2 | 176 | 28.9 | 20 | 13.6 | 196 | 25.9 | ||||

| 3 | 176 | 28.9 | 10 | 6.8 | 186 | 24.6 | ||||

| 4 | 138 | 22.7 | 35 | 23.8 | 173 | 22.9 | ||||

| 5 | 27 | 4.4 | 45 | 30.6 | 72 | 9.5 | ||||

| More than 5 people | 8 | 1.3 | 28 | 19 | 36 | 4.8 | ||||

| Professional situation | Unemployed | 74 | 12.2 | 66 | 44.9 | 140 | 18.5 | 118.28 | .001 | .396 |

| Employed | 330 | 54.2 | 25 | 17 | 355 | 47 | ||||

| Self-employed worker | 48 | 7.9 | 3 | 2 | 51 | 6.7 | ||||

| Worker/student | 28 | 4.6 | 11 | 7.5 | 39 | 5.2 | ||||

| Student | 106 | 17.4 | 30 | 20.4 | 136 | 18 | ||||

| Retired | 18 | 3 | 11 | 7.5 | 29 | 3.8 | ||||

| Other | 5 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.8 | ||||

| Income | Up to 522.50 euros | 46 | 7.6 | 38 | 25.9 | 84 | 11.1 | 175.19 | .001 | .481 |

| From 522.50 to 1045 euros | 74 | 12.2 | 66 | 44.9 | 140 | 18.5 | ||||

| From 1045 to 1567.5 euros | 101 | 16.6 | 31 | 21.1 | 132 | 17.5 | ||||

| From 1567.5 to 2090 euros | 115 | 18.9 | 3 | 2 | 118 | 15.6 | ||||

| From 2,090 to 2,612.5 euros | 98 | 16.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 100 | 13.2 | ||||

| From 2612.5 to 3135 euros | 61 | 10 | 4 | 2.7 | 65 | 8.6 | ||||

| From €3,135 to €3,657.5 | 37 | 6.1 | 1 | 0.7 | 38 | 5 | ||||

| More than 3657.5 euros | 77 | 12.6 | 2 | 1.4 | 79 | 10.4 | ||||

| Variables |

Ethnicity |

Mean | SD | p | Cohen’s dd |

| Psychological distress | Majority | .82 | .69 | <.001 | 0.997 |

| Minority | 1.57 | .80 | |||

| Social discrimination | Majority | .81 | .81 | <.001 | 1.798 |

| Minority | 2.62 | 1.17 | |||

| Perceived social support | Majority | 5.58 | 1.17 | <.001 | 0.447 |

| Minority | 6.09 | 1.09 | |||

| Resilience | Majority | 2.64 | .73 | <.001 | 0.84 |

| Minority | 3.17 | .52 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

| Psychological distress | B |

SEB |

Β | B |

SEB |

Β | B |

SEB |

Β |

| Gender | .041 | .935 | .001 | -1.504 | .766 | -.054* | -1,698 | .767 | -.061* |

| Sexual orientation | 6,178 | 1,474 | .144 | 2,628 | 1,203 | .061 | 2,651 | 1,198 | .062 |

| Age | -.203 | .036 | -.202** | -.091 | .030 | -.090 | -.087 | .030 | -.086 |

| Education | -2.205 | .472 | -.187 | -.342 | .398 | -.029 | -.257 | .398 | -.022 |

| Household | .672 | .377 | .065 | -.037 | .312 | -.004 | -.135 | .313 | -.013 |

| Per capita income | -4,906 | 1,146 | -.175 | -1,010 | .946 | -.036 | -.605 | .955 | -.022 |

| Social discrimination | 7.253 | .397 | .601 | 6,717 | .446 | .556** | |||

| Perceived social support | -.705 | .347 | -.060 | -.811 | .348 | -.069 | |||

| Resilience | -3,898 | .565 | -.204** | -4,295 | .583 | -.224** | |||

| Ethnicity | 3,412 | 1,312 | .098 | ||||||

| R 2 | 0.218 | 0.497 | 0.502 | ||||||

| Z | 34.73 | 81.99 | 75.04 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).