Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biological Characteristics and Functions of OX40/OX40L

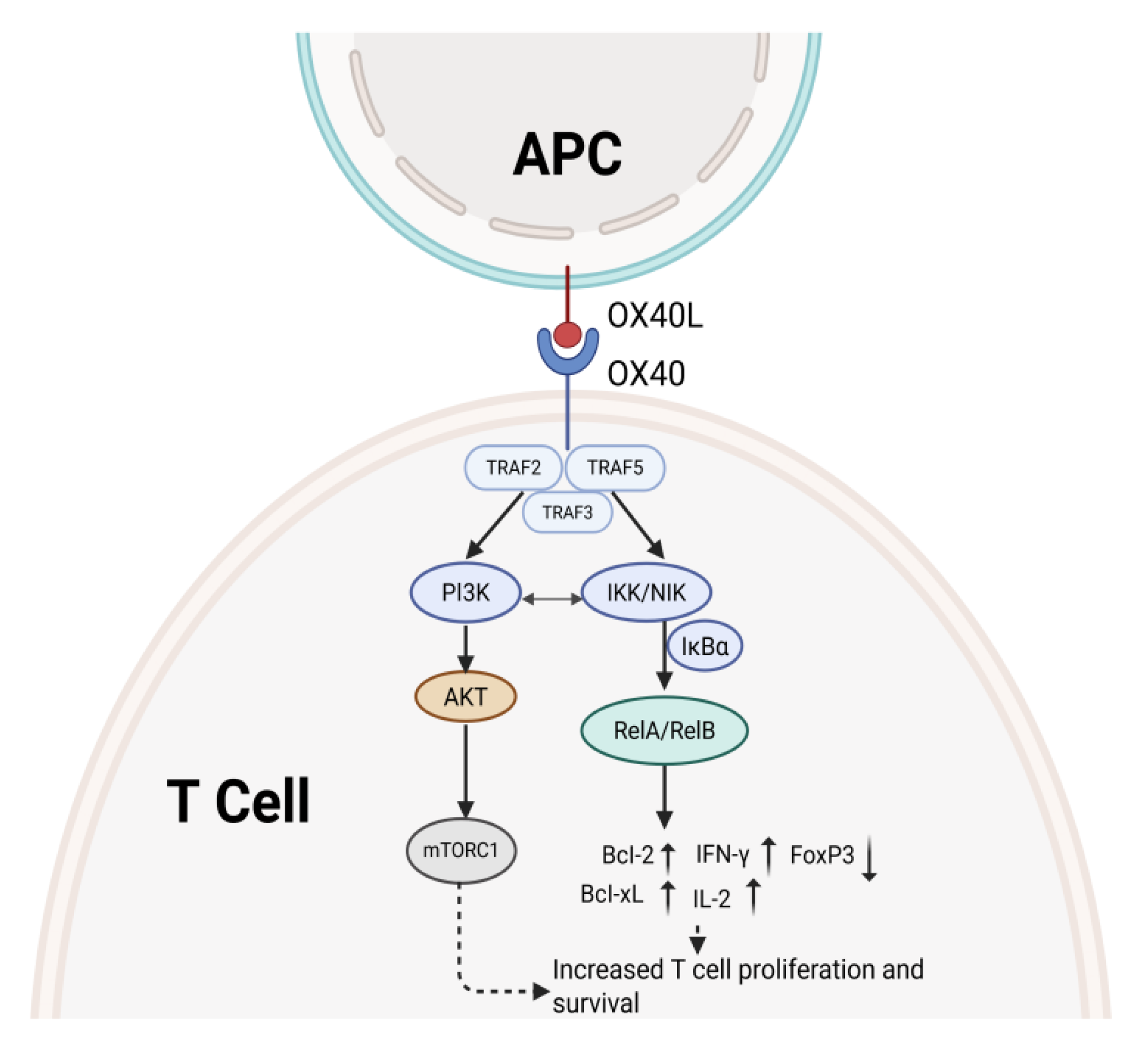

3. Overview of Signaling Pathways

3.1. PI3K/AKT Pathway

3.2. The NF-κB Pathway

3.3. MAPK Pathway

3.4. Calcium Ion Signaling and PKC Activation

4. Role of OX40 Pathway in Tumor Immunity

4.1. Enhanced T Cell Activity and Persistence

4.2. Regulates the Action of Immune Cells Against Tumors

4.2.1. B Cells

4.2.2. Dendritic Cells

4.2.3. Natural Killer Cells

4.2.4. Tumor-Associated Macrophages

5. Targeted Therapy Strategies

5.1. Agonist Therapy

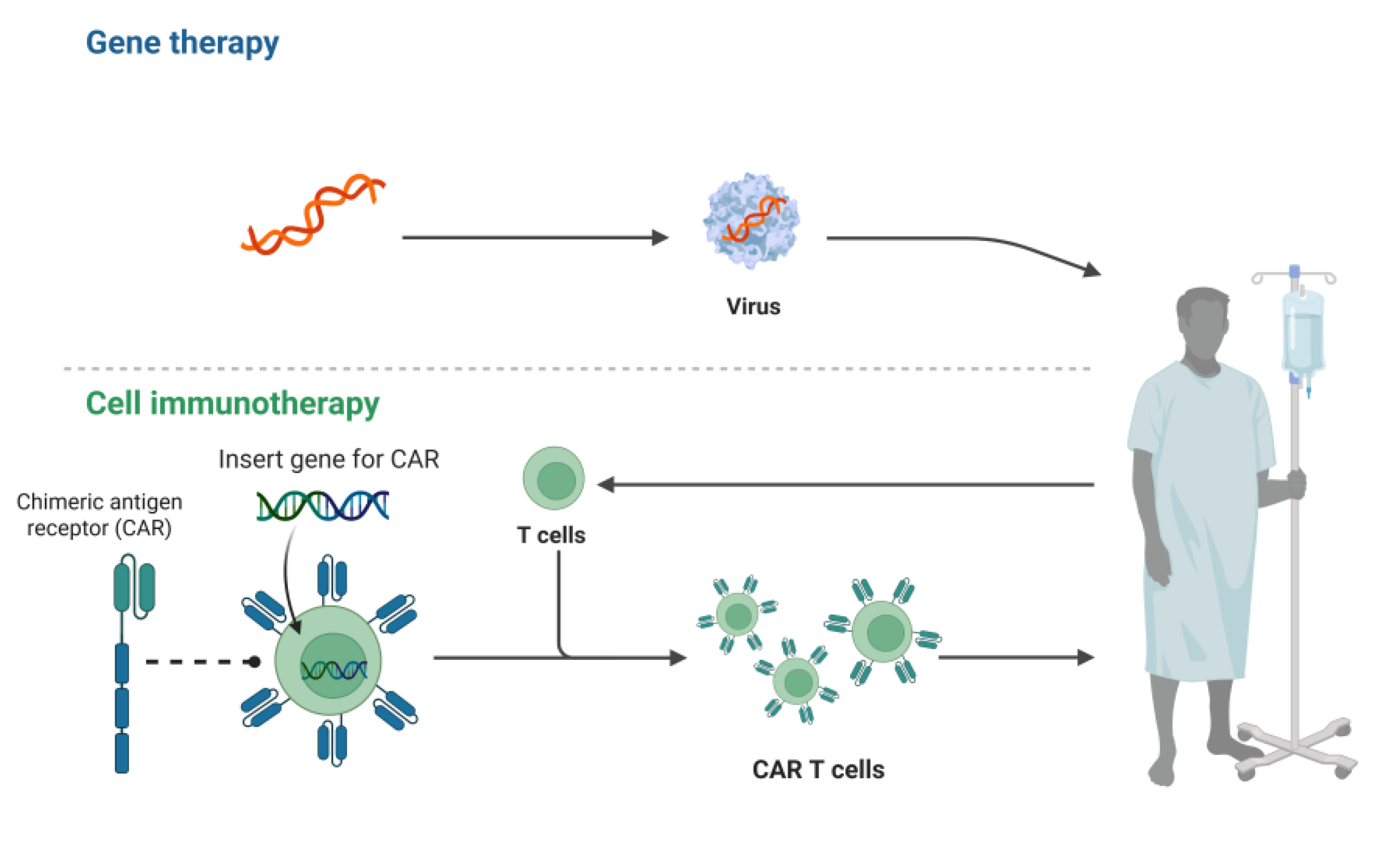

5.2. Genetic Engineering and Cell Therapy

5.3. Combination Treatment Strategies

5.3.1. Combined with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

5.3.2. Combination with Radiotherapy or Chemotherapy

6. Research Progress

6.1. Preclinical Studies

6.2. Clinical Trials of OX40 Agonist Monotherapy in Tumor Intervention

6.3. Combination Therapy Trials

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Xu, L.; Lin, B.; et al. DNA Nanostructures: Advancing Cancer Immunotherapy. Small (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany). 2024, 20, e2405231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, J.; Agudo, J. Metastatic Colonization: Escaping Immune Surveillance. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, Z. The application of nanotechnology in immune checkpoint blockade for cancer treatment. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2018, 290, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews Cancer. 2012, 12, 252–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi-Hajivar, S.; Zakeri-Milani, P.; Mohammadi, H.; Niazi, M.; Soleymani-Goloujeh, M.; Baradaran, B.; et al. Overview on experimental models of interactions between nanoparticles and the immune system. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2016, 83, 1365–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Yu, A.; Xiao, X.; Tang, J.; Zu, X.; Chen, W.; et al. CD4(+) T cell exhaustion leads to adoptive transfer therapy failure which can be prevented by immune checkpoint blockade. American journal of cancer research. 2020, 10, 4234–50. [Google Scholar]

- Woroniecka, K.; Chongsathidkiet, P.; Rhodin, K.; Kemeny, H.; Dechant, C.; Farber, S.H.; et al. T-Cell Exhaustion Signatures Vary with Tumor Type and Are Severe in Glioblastoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2018, 24, 4175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Lee, E.J.; Han, J.H.; Chung, H.S. Caryophylli Cortex Suppress PD-L1 Expression in Cancer Cells and Potentiates Anti-Tumor Immunity in a Humanized PD-1/PD-L1 Knock-In MC-38 Colon Cancer Mouse Model. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hai, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Lv, Y.; Cui, D.; et al. OX40 ligand promotes follicular helper T cell differentiation and development in mice with immune thrombocytopenia. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2025, 26, 240–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Nagai, H.; Suzuki, A.; Ito, A.; Matsuyama, S.; Shibui, N.; et al. Generation and characterization of OX40-ligand fusion protein that agonizes OX40 on T-Lymphocytes. Frontiers in immunology. 2024, 15, 1473815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharshawi, K.; Marinelarena, A.; Kumar, P.; El-Sayed, O.; Bhattacharya, P.; Sun, Z.; et al. PKC-ѳ is dispensable for OX40L-induced TCR-independent Treg proliferation but contributes by enabling IL-2 production from effector T-cells. Scientific reports. 2017, 7, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberst, M.D.; Auge, C.; Morris, C.; Kentner, S.; Mulgrew, K.; McGlinchey, K.; et al. Potent Immune Modulation by MEDI6383, an Engineered Human OX40 Ligand IgG4P Fc Fusion Protein. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2018, 17, 1024–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrolashrafi, K.; Guo, L.; Kikuchi, R.; Hao, A.; Yamamoto, R.K.; Tolson, H.C.; et al. An OX-Tra’Ordinary Tale: The Role of OX40 and OX40L in Atopic Dermatitis. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladi, S.; Masjedi, M.; Ghasemi, R. ; MGH; Eskandari, N. The In Vitro Impact of Glycyrrhizic Acid on CD4+ T Lymphocytes through OX40 Receptor in the Patients with Allergic Rhinitis. Inflammation. 2018, 41, 1690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imianowski, C.J.; Kuo, P.; Whiteside, S.K.; von Linde, T.; Wesolowski, A.J.; Conti, A.G.; et al. IFNgamma Production by Functionally Reprogrammed Tregs Promotes Antitumor Efficacy of OX40/CD137 Bispecific Agonist Therapy. Cancer research communications. 2024, 4, 2045–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdasik, D.W.; Gaspal, F.; Halford, E.E.; Fiancette, R.; Dutton, E.E.; Willis, C.; et al. Th1 responses in vivo require cell-specific provision of OX40L dictated by environmental cues. Nature communications. 2020, 11, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.; Deng, M.; Jin, W.; Hong, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. BGB-A445, a novel non-ligand-blocking agonistic anti-OX40 antibody, exhibits superior immune activation and antitumor effects in preclinical models. Frontiers of medicine. 2023, 17, 1170–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahiliani, V.; Hutchinson, T.E.; Abboud, G.; Croft, M.; Salek-Ardakani, S. OX40 Cooperates with ICOS To Amplify Follicular Th Cell Development and Germinal Center Reactions during Infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2017, 198, 218–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, M.; Yan, Y.; Gu, W.; Zhang, X.; Tan, J.; et al. OX40L induces helper T cell differentiation during cell immunity of asthma through PI3K/AKT and P38 MAPK signaling pathway. Journal of translational medicine. 2018, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yu, H.; Sun, G.; Sun, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. OX40 promotes obesity-induced adipose inflammation and insulin resistance. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2017, 74, 3827–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Croft, M.; Geng, B.; Rynkiewicz, N.; Lucchesi, D.; Peakman, M.; et al. The role of OX40 ligand/OX40 axis signalling in atopic dermatitis. The British journal of dermatology. 2024, 191, 488–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, T.; Choi, H.; Croft, M. OX40 complexes with phosphoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase B (PKB) to augment TCR-dependent PKB signaling. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2011, 186, 3547–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, M.; So, T.; Duan, W.; Soroosh, P. The significance of OX40 and OX40L to T-cell biology and immune disease. Immunological reviews. 2009, 229, 173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, C.; Sun, C.; Zhao, X.; Tian, D.; Shi, W.; et al. OX40 expression in neutrophils promotes hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. JCI insight. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, G.; Sun, X.; Li, W.; Liu, K.; Tian, D.; Dong, Y.; et al. Critical role of OX40 in the expansion and survival of CD4 T-cell-derived double-negative T cells. Cell death & disease. 2018, 9, 616. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata, S.; Hori, T.; Imura, A.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Uchiyama, T. Activation of OX40 signal transduction pathways leads to tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 2- and TRAF5-mediated NF-kappaB activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998, 273, 5808–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestas, J.; Crampton, S.P.; Hori, T.; Hughes, C.C. Endothelial cell co-stimulation through OX40 augments and prolongs T cell cytokine synthesis by stabilization of cytokine mRNA. International immunology. 2005, 17, 737–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Du, R.; Liu, P.; Chen, G. OX40-OX40 ligand interaction may activate phospholipase C signal transduction pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Chemico-biological interactions. 2009, 180, 460–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.W.; Chen, Y.; Lv, H.T.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.J.; Qian, W.G.; et al. Kawasaki disease OX40-OX40L axis acts as an upstream regulator of NFAT signaling pathway. Pediatric research. 2019, 85, 835–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.K.; Carlin, S.; Pack, R.A.; Arndt, G.M.; Au, W.W.; Johnson, P.R.; et al. Detection and characterization of OX40 ligand expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: a possible role in asthma? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2004, 113, 683–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A.D.; Rivera, M.M.; Prell, R.; Morris, A.; Ramstad, T.; Vetto, J.T.; et al. Engagement of the OX-40 receptor in vivo enhances antitumor immunity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2000, 164, 2160–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaergaard, J.; Tanaka, J.; Kim, J.A.; Rothchild, K.; Weinberg, A.; Shu, S. Therapeutic efficacy of OX-40 receptor antibody depends on tumor immunogenicity and anatomic site of tumor growth. Cancer research. 2000, 60, 5514–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wherry, E.J.; Kurachi, M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015, 15, 486–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauken, K.E.; Wherry, E.J. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends in immunology. 2015, 36, 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, G.; de Silva, S.; Giffin, L.; Xu, X.; Rose, J.; Schreiber, T.H. Gp96-Ig/Costimulator (OX40L, ICOSL, or 4-1BBL) Combination Vaccine Improves T-cell Priming and Enhances Immunity, Memory, and Tumor Elimination. Cancer immunology research. 2016, 4, 766–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, J.M.; Alejo, A.; Avia, J.M.; Rodriguez-Martin, D.; Sanchez, C.; Alcami, A.; et al. Activation of OX40 and CD27 Costimulatory Signalling in Sheep through Recombinant Ovine Ligands. Vaccines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jia, W.; Zhou, X.; Ma, Z.; Liu, J.; Lan, P. CBX4 suppresses CD8(+) T cell antitumor immunity by reprogramming glycolytic metabolism. Theranostics. 2024, 14, 3793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.C.; Moller, S.H.; Ho, P.C. Re-”Formate” T-cell Antitumor Responses. Cancer discovery. 2023, 13, 2507–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, G.; Yin, J.; Tan, B.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; et al. Amino-acid transporters in T-cell activation and differentiation. Cell death & disease. 2017, 8, e2655. [Google Scholar]

- Polesso, F.; Weinberg, A.D.; Moran, A.E. Late-Stage Tumor Regression after PD-L1 Blockade Plus a Concurrent OX40 Agonist. Cancer immunology research. 2019, 7, 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Cui, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. The OX40-TRAF6 axis promotes CTLA-4 degradation to augment antitumor CD8(+) T-cell immunity. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2023, 20, 1445–56. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Enhanced Antitumor Immunity Through T Cell Activation with Optimized Tandem Double-OX40L mRNAs. International journal of nanomedicine. 2025, 20, 3607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, H.; Oshima, H.; Takeda, K.; Atsuta, M.; Nakano, H.; Nakajima, A.; et al. CD28-independent costimulation of T cells by OX40 ligand and CD70 on activated B cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 1999, 162, 7058–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, A.M.; Suo, S.; Wang, Y.; Gunasti, L.; Porter, C.B.M.; Nabilsi, N.; et al. Tissue-resident memory and circulating T cells are early responders to pre-surgical cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2022, 185, 2918–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utzschneider, D.T.; Delpoux, A.; Wieland, D.; Huang, X.; Lai, C.Y.; Hofmann, M.; et al. Active Maintenance of T Cell Memory in Acute and Chronic Viral Infection Depends on Continuous Expression of FOXO1. Cell reports. 2018, 22, 3454–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Chiu, Y.; Kingsley, C.V.; Fry, D.; et al. Combination of PD-1 Inhibitor and OX40 Agonist Induces Tumor Rejection and Immune Memory in Mouse Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020, 159, 306–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortini, A.; Ellinghaus, U.; Malik, T.H.; Cunninghame Graham, D.S.; Botto, M.; Vyse, T.J. B cell OX40L supports T follicular helper cell development and contributes to SLE pathogenesis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2017, 76, 2095–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, L.; Feng, X.; Yin, H.; Fan, X.; Gao, C.; et al. Blockade of OX40/OX40L signaling using anti-OX40L alleviates murine lupus nephritis. European journal of immunology. 2024, 54, e2350915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, X.; Lan, P.; Li, J.; Dou, Y.; Chen, W.; et al. OX40 Costimulation Inhibits Foxp3 Expression and Treg Induction via BATF3-Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Cell reports. 2018, 24, 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, W.; Fu, N.; Wang, Q.; Shi, B. Regulation of the Function of T Follicular Helper Cells and B Cells in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus by the OX40/OX40L Axis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2024, 109, 2823–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Sui, B.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Recombinant Rabies Virus Overexpressing OX40-Ligand Enhances Humoral Immune Responses by Increasing T Follicular Helper Cells and Germinal Center B Cells. Vaccines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chtanova, T.; Tangye, S.G.; Newton, R.; Frank, N.; Hodge, M.R.; Rolph, M.S.; et al. T follicular helper cells express a distinctive transcriptional profile, reflecting their role as non-Th1/Th2 effector cells that provide help for B cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2004, 173, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Wei, Y.; Hu, B.; Liao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wan, W.H.; et al. c-Myc-driven glycolysis polarizes functional regulatory B cells that trigger pathogenic inflammatory responses. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2022, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.; Giladi, A.; Barboy, O.; Hamon, P.; Li, B.; Zada, M.; et al. The interaction of CD4(+) helper T cells with dendritic cells shapes the tumor microenvironment and immune checkpoint blockade response. Nature cancer. 2022, 3, 303–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.J.; et al. Tumor microenvironment-related dendritic cell deficiency: a target to enhance tumor immunotherapy. Pharmacological research. 2020, 159, 104980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; Jia, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; et al. OX40L enhances the immunogenicity of dendritic cells and inhibits tumor metastasis in mice. Microbiology and immunology. 2023, 67, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fang, L.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, G.; Li, W.; et al. Control of T(reg) cell homeostasis and immune equilibrium by Lkb1 in dendritic cells. Nature communications. 2018, 9, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poropatich, K.; Dominguez, D.; Chan, W.C.; Andrade, J.; Zha, Y.; Wray, B.; et al. OX40+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment promote antitumor immunity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2020, 130, 3528–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badillo-Godinez, O.; Niemi, J.; Helfridsson, L.; Karimi, S.; Ramachandran, M.; Mangukiya, H.B.; et al. Brain tumors induce immunoregulatory dendritic cells in draining lymph nodes that can be targeted by OX40 agonist treatment. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S.; Dai, D.; Horton, B.; Gajewski, T.F. Tumor-Residing Batf3 Dendritic Cells Are Required for Effector T Cell Trafficking and Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cancer cell. 2017, 31, 711–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuebling, T.; Schumacher, C.E.; Hofmann, M.; Hagelstein, I.; Schmiedel, B.J.; Maurer, S.; et al. The Immune Checkpoint Modulator OX40 and Its Ligand OX40L in NK-Cell Immunosurveillance and Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer immunology research. 2018, 6, 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, J.; Andarini, S.; Tahara, M.; Saijo, Y.; Ishii, N.; Kawakami, K.; et al. OX40 ligand expressed by DCs costimulates NKT and CD4+ Th cell antitumor immunity in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007, 117, 3330–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, S.; Phan, M.T.; Chun, S.; Yu, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Expansion of Human NK Cells Using K562 Cells Expressing OX40 Ligand and Short Exposure to IL-21. Frontiers in immunology. 2019, 10, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, S.; Barsoumian, H.B.; Schoenhals, J.E.; Jackson, H.L.; Yanamandra, N.; Caetano, M.S.; et al. Radiation Followed by OX40 Stimulation Drives Local and Abscopal Antitumor Effects in an Anti-PD1-Resistant Lung Tumor Model. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2018, 24, 5735–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, M.; Lin, D.; Yan, N.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Huang, Z. Oxaliplatin facilitates tumor-infiltration of T cells and natural-killer cells for enhanced tumor immunotherapy in lung cancer model. Anti-cancer drugs. 2022, 33, 117–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Li, T.; Ou, M.; Luo, R.; Chen, H.; Ren, H.; et al. OX40L-expressing M1-like macrophage exosomes for cancer immunotherapy. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2024, 365, 469–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, K.; Xu, L.; Wu, H.; Liao, H.; Luo, L.; Liao, M.; et al. OX40 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a distinct immune microenvironment, specific mutation signature, and poor prognosis. Oncoimmunology. 2018, 7, e1404214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yang, K.; Zhang, D.; Li, F.; Chen, J.; et al. Reprogramming macrophage by targeting VEGF and CD40 potentiates OX40 immunotherapy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2024, 698, 149546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeaux, M.D.; Rolig, A.S.; Agnello, G.; Enzler, D.; Kasiewicz, M.J.; Priddy, L.; et al. Arginase Therapy Combines Effectively with Immune Checkpoint Blockade or Agonist Anti-OX40 Immunotherapy to Control Tumor Growth. Cancer immunology research. 2021, 9, 415–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C.Y.X.; Jain, P.; Susnjar, A.; Rhudy, J.; Folci, M.; Ballerini, A.; et al. Nanofluidic drug-eluting seed for sustained intratumoral immunotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2018, 285, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.J.; Munoz-Rojas, A.R.; Meeth, K.M.; Kellman, L.N.; Amezquita, R.A.; Thakral, D.; et al. Myeloid-targeted immunotherapies act in synergy to induce inflammation and antitumor immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2018, 215, 877–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Therapeutic strategies for the costimulatory molecule OX40 in T-cell-mediated immunity. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2020, 10, 414–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.E.; Polesso, F.; Weinberg, A.D. Immunotherapy Expands and Maintains the Function of High-Affinity Tumor-Infiltrating CD8 T Cells In Situ. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2016, 197, 2509–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polesso, F.; Sarker, M.; Weinberg, A.D.; Murray, S.E.; Moran, A.E. OX40 Agonist Tumor Immunotherapy Does Not Impact Regulatory T Cell Suppressive Function. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2019, 203, 2011–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Jing, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Ni, H.; et al. Development and characterization of a novel anti-OX40 antibody for potent immune activation. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2020, 69, 939–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, K.A.; Gooderham, M.J.; Girard, G.; Raman, M.; Strout, V. Phase I randomized study of KHK4083, an anti-OX40 monoclonal antibody, in patients with mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2017, 31, 1324–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Simpson, E.L.; Reich, K.; Kabashima, K.; Igawa, K.; Suzuki, T.; et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. Lancet (London, England). 2023, 401, 204–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, N.J.; Borthakur, G.; Pemmaraju, N.; Dinardo, C.D.; Kadia, T.M.; Jabbour, E.; et al. A multi-arm phase Ib/II study designed for rapid, parallel evaluation of novel immunotherapy combinations in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2022, 63, 2161–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, K.; Muller, T.R.; Busch, D.H. Orthotopic T-Cell Receptor Replacement-An “Enabler” for TCR-Based Therapies. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restifo, N.P.; Dudley, M.E.; Rosenberg, S.A. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: harnessing the T cell response. Nature reviews Immunology. 2012, 12, 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, P.; Giordano Attianese, G.M.P.; Ouchen, K.; Cribioli, E.; Triboulet, M.; Ash, S.; et al. A lentiviral vector for the production of T cells with an inducible transgene and a constitutively expressed tumour-targeting receptor. Nature biomedical engineering. 2023, 7, 1063–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, X.; Alvarez Calderon, F.; Wobma, H.; Gerdemann, U.; Albanese, A.; Cagnin, L.; et al. Human OX40L-CAR-T(regs) target activated antigen-presenting cells and control T cell alloreactivity. Science translational medicine. 2024, 16, eadj9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Li, F.; Wang, R.; Cen, T.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; et al. An armed oncolytic virus enhances the efficacy of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy by converting tumors to artificial antigen-presenting cells in situ. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2022, 30, 3658–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, S.; Toellner, K.M.; Raykundalia, C.; Goodall, M.; Lane, P. CD4 T cell cytokine differentiation: the B cell activation molecule, OX40 ligand, instructs CD4 T cells to express interleukin 4 and upregulates expression of the chemokine receptor, Blr-1. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998, 188, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Yoon, S.E.; Kim, W.S. Current Challenges in Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy in Patients With B-cell Lymphoid Malignancies. Annals of laboratory medicine. 2024, 44, 210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Qi, K.; et al. A chimeric antigen receptor with antigen-independent OX40 signaling mediates potent antitumor activity. Science translational medicine 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Cortes, E.; Franco-Fuquen, P.; Garcia-Robledo, J.E.; Forero, J.; Booth, N.; Castro, J.E. ICOS and OX40 tandem co-stimulation enhances CAR T-cell cytotoxicity and promotes T-cell persistence phenotype. Frontiers in oncology. 2023, 13, 1200914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhong, R.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Li, F.; Liang, J.; et al. OX40-heparan sulfate binding facilitates CAR T cell penetration into solid tumors in mice. Science translational medicine. 2025, 17, eadr2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, M.; Fu, C.; Tuhin, I.J.; Ye, J.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptors containing the OX40 signalling domain enhance the persistence of T cells even under repeated stimulation with multiple myeloma target cells. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2022, 15, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Rittig, S.M.; Lutz, M.S.; Clar, K.L.; Zhou, Y.; Kropp, K.N.; Koch, A.; et al. Controversial Role of the Immune Checkpoint OX40L Expression on Platelets in Breast Cancer Progression. Frontiers in oncology. 2022, 12, 917834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, A.; An, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, X.; et al. B cells enhance EphA2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells cytotoxicity against glioblastoma via improving persistence. Human immunology. 2024, 85, 111093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Guo, J.; Li, T.; Jia, L.; Tang, X.; Zhu, J.; et al. c-Met-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Journal of biomedical research. 2021, 36, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Williams, L.J.; Xu, C.; Melendez, B.; McKenzie, J.A.; Chen, Y.; et al. Anti-OX40 Antibody Directly Enhances The Function of Tumor-Reactive CD8(+) T Cells and Synergizes with PI3Kbeta Inhibition in PTEN Loss Melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019, 25, 6406–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrimali, R.K.; Ahmad, S.; Verma, V.; Zeng, P.; Ananth, S.; Gaur, P.; et al. Concurrent PD-1 Blockade Negates the Effects of OX40 Agonist Antibody in Combination Immunotherapy through Inducing T-cell Apoptosis. Cancer immunology research. 2017, 5, 755–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Physical- and Chemical-Dually ROS-Responsive Nano-in-Gel Platforms with Sequential Release of OX40 Agonist and PD-1 Inhibitor for Augmented Combination Immunotherapy. Nano letters. 2023, 23, 1424–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Redmond, W.L. Current Clinical Trial Landscape of OX40 Agonists. Current oncology reports. 2022, 24, 951–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.R.; Hoffmann, F.W.; Premeaux, T.A.; Fujita, T.; Soprana, E.; Panigada, M.; et al. Multi-antigen Vaccination With Simultaneous Engagement of the OX40 Receptor Delays Malignant Mesothelioma Growth and Increases Survival in Animal Models. Frontiers in oncology. 2019, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, J.D.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Ranasinghe, S.; Kao, K.Z.; Lako, A.; Tsuji, J.; et al. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab alone or in combination with low-dose or hypofractionated radiotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer refractory to previous PD(L)-1 therapy: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2022, 23, 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Cao, L.; Li, Z.W.; Zhao, L.; Wu, H.F.; Yue, D.; et al. Fluorouracil-based neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with or without oxaliplatin for treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 45513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.G.; Wee, C.W.; Kang, M.H.; Kim, M.J.; Jeon, S.H.; Kim, I.A. Combination of OX40 Co-Stimulation, Radiotherapy, and PD-1 Inhibition in a Syngeneic Murine Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Model. Cancers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Q.; Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; et al. Nanomaterial-mediated modulation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Acta biomaterialia. 2024, 176, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramser, M.; Eichelberger, S.; Daster, S.; Weixler, B.; Kraljevic, M.; Mechera, R.; et al. High OX40 expression in recurrent ovarian carcinoma is indicative for response to repeated chemotherapy. BMC cancer. 2018, 18, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Meng, S.; Bi, C.; Guan, Q.; et al. OX40 shapes an inflamed tumor immune microenvironment and predicts response to immunochemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clinical immunology (Orlando, Fla). 2023, 251, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschhorn-Cymerman, D.; Rizzuto, G.A.; Merghoub, T.; Cohen, A.D.; Avogadri, F.; Lesokhin, A.M.; et al. OX40 engagement and chemotherapy combination provides potent antitumor immunity with concomitant regulatory T cell apoptosis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009, 206, 1103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyás, D.; Kovács, G.; Jankovics, I.; Mészáros, L.; Lőrincz, M.; Dénes, B. Effects of the combination of a monoclonal agonistic mouse anti-OX40 antibody and toll-like receptor agonists: Unmethylated CpG and LPS on an MB49 bladder cancer cell line in a mouse model. PloS one. 2022, 17, e0270802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Sun, X.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yang, C.; et al. SHR-1806, a robust OX40 agonist to promote T cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Cancer biology & therapy. 2024, 25, 2426305. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, N.; Talat, H.; Curry, W.T. Agonist OX40 immunotherapy improves survival in glioma-bearing mice and is complementary with vaccination with irradiated GM-CSF-expressing tumor cells. Neuro-oncology. 2018, 20, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Cheng, D.; Xia, Z.; Luan, M.; Zhang, S. PD-1 blockade and OX40 triggering synergistically protects against tumor growth in a murine model of ovarian cancer. PloS one. 2014, 9, e89350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, K.; Hahn, T.; Lee, W.C.; Ling, L.E.; Weinberg, A.D.; Akporiaye, E.T. The small molecule TGF-β signaling inhibitor SM16 synergizes with agonistic OX40 antibody to suppress established mammary tumors and reduce spontaneous metastasis. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2012, 61, 511–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, G.; et al. Anti-OX40 antibody BAT6026 in patients with advanced solid tumors: A multi-center phase I study. iScience. 2025, 28, 112270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhen, R.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Frye, A.K.; Tran, E.; Rajamanickam, V.; Chang, S.C.; et al. Neoadjuvant anti-OX40 (MEDI6469) therapy in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma activates and expands antigen-specific tumor-infiltrating T cells. Nature communications. 2021, 12, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glisson, B.S.; Leidner, R.S.; Ferris, R.L.; Powderly, J.; Rizvi, N.A.; Keam, B.; et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of MEDI0562, a Humanized OX40 Agonist Monoclonal Antibody, in Adult Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2020, 26, 5358–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.J.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Kristeleit, R.; Cho, D.C.; Blagden, S.P.; Berthold, D.; et al. First-in-human phase I/II, open-label study of the anti-OX40 agonist INCAGN01949 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Burris, H.A.; de Miguel Luken, M.J.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Bang, Y.J.; Gordon, M.; et al. First-In-Human Phase I Study of the OX40 Agonist MOXR0916 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2022, 28, 3452–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracp, J.D. A phase 1 study of the OX40 agonist BGB-A445, with or without tislelizumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting 2023, June 2-6, 2023, Chicago, IL, USA2023.

- Postel-Vinay, S.; Lam, V.K.; Ros, W.; Bauer, T.M.; Hansen, A.R.; Cho, D.C.; et al. First-in-human phase I study of the OX40 agonist GSK3174998 with or without pembrolizumab in patients with selected advanced solid tumors (ENGAGE-1). Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Kang, Y.K.; Kim, T.Y.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Santoro, A.; Sangro, B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated With Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA oncology. 2020, 6, e204564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, O.; Chiappori, A.A.; Thompson, J.A.; Doi, T.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Eskens, F.; et al. First-in-human study of an OX40 (ivuxolimab) and 4-1BB (utomilumab) agonistic antibody combination in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2022, 10(10).

- Knisely, A.; Ahmed, J.; Stephen, B.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Karp, D.; Zarifa, A.; et al. Phase 1/2 trial of avelumab combined with utomilumab (4-1BB agonist), PF-04518600 (OX40 agonist), or radiotherapy in patients with advanced gynecologic malignancies. Cancer. 2024, 130, 400–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, T.; Czerwinski, D.; Haebe, S.; Sathe, A.; Grimes, S.; Martin, B.; et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial Adding OX40 Agonism to In Situ Therapeutic Cancer Vaccination in Patients with Low-Grade B-cell Lymphoma Highlights Challenges in Translation from Mouse to Human Studies. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2025, 31, 868–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, B.D.; Kovacsovics-Bankowski, M.; Morris, N.; Walker, E.; Chisholm, L.; Floyd, K.; et al. OX40 is a potent immune-stimulating target in late-stage cancer patients. Cancer research. 2013, 73, 7189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, WL. Challenges and opportunities in the development of combination immunotherapy with OX40 agonists. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2023, 23, 901–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Pu, P.; Wu, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; et al. A Novel Bispecific Antibody with PD-L1-assisted OX40 Activation for Cancer Treatment. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2020, 19, 2564–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holay, N.; Yadav, R.; Ahn, S.J.; Kasiewicz, M.J.; Polovina, A.; Rolig, A.S.; et al. INBRX-106: a hexavalent OX40 agonist that drives superior antitumor responses via optimized receptor clustering. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseyenko, A.; Muggia, F.; Condamine, T.; Pulini, J.; Janik, J.E.; Cho, D.C. Sequential therapy with INCAGN01949 followed by ipilimumab and nivolumab in two patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology reports. 2020, 34, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Dangi, T.; Awakoaiye, B.; Lew, M.H.; Irani, N.; Fourati, S.; et al. Delayed reinforcement of costimulation improves the efficacy of mRNA vaccines in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yang, Z.; Su, Q.; Fang, L.; Xiang, Q.; Tian, C.; et al. Bivalent OX40 Aptamer and CpG as Dual Agonists for Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2025, 17, 7353–62. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, B.; Pan, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, L.; et al. Endothelial OX40 activation facilitates tumor cell escape from T cell surveillance through S1P/YAP-mediated angiogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Kato, S.; Nishizaki, D.; Miyashita, H.; Lee, S.; Nesline, M.K.; et al. OX40/OX40 ligand and its role in precision immune oncology. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2024, 43, 1001–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical ID | Format | Phase Status | Name | Tumor Type | information by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01862900 | IgG1 | I/II | MEDI6469 | Metastatic breast cancer | Providence Health Services |

| NCT02274155 | IgG1 | I | MEDI0562 | Head and neck cancer/Solid tumors/Ovarian cancer | Providence Health Services |

| NCT02315066 | IgG2 | I/II | PF-04518600 | Metastatic carcinoma/malignancies | Pfizer |

| NCT02410512 | IgG1 | I | MOXR0916 | Metastatic Solid tumors | Genentech |

| NCT02737475 | IgG1 | I/II | BMS-986178 | Solid tumors | Bristol-Myers Squibb |

| NCT03410901 | IgG1 | I | BMS-986178 | Low-grade B-Cell non-Hodg-kin lymphomas | Ronald Levy Stanford university |

| NCT04387071 | IgG4 | I/II | INCAGN01949 | Pancreatic cancer | University of southern california |

| NCT03758001 | IgG4 | I | IBI101 | Solid tumors | Innovent Biologics |

| NCT05229601 | IgG1 | I | HFB301001 | Solid tumors | HiFiBio Therapeutics |

| NCT03092856 | IgG2 | I/II | PF-04581600 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Pfizer |

| NCT01775631 | IgG2 | I/II | BMS-663513 | B-Cell non-Hodg-kin lymphomas | Bristol-Myers Squibb |

| NCT02598960 | IgG2 | I/II | BMS-986156 | Advanced-stage Solid tumors | Bristol-Myers Squibb |

| NCT02221960 | IgG2 | I/II | MEDI6383 | Recurrent or metastatic solid tumors | MedImmune LLC |

| NCT04215978 | IgG1 | I/II | BGB-A445 | Advanced solid tumors | BeiGene |

| NCT02274155 | IgG2 | I/II | 9B12 | Head and neck cancer | Providence Health Services |

| Name | Phase | Combination |

Type of mouse tumor | Type of OX40 therapy | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAT6026 | I | Single agent | Advanced cancer | Anti-OX40,0.01-10mg/kg, IV, Q3W. | N=30, ORR 0%, DCR 38.5% | [110] |

| MEDI6469 | I/II | Single agent | HNSCC | Anti-OX40,0.4mg/kg, IV, day1.3.5 | n=17, OS 82%; PFS 71% at 3 years | [111] |

| MEDI0562 | I | Single agent | Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,0.03-10mg/kg, IV, Q2W. | N=55, ORR 4%; PR1, DCR 22% | [112] |

| INCAGN01949 | I/II | Single agent | Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,7-1400mg, IV, Q2W. | N=87, ORR 1.5%; PR1 | [113] |

| MOXR0916 | I | Single agent | Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,0.2-1200mg, IV, Q3W. | N=172, ORR 1.2% PR2, DCR66% | [114] |

| BGB-A445 | Ib | Tislelizumab | Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,0.03-40mg/kg, IV, Q3W. Anti-PD-1,200mg, IV, Q3W. | N=30, ORR 23%; PR 7 | [115] |

| GSK3174998 | I | Pembrolizumab | Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,0.03-10mg/kg, IV, Q3W. Anti-PD-1,200mg, IV, Q3W. | N=138, Single agent ORR0%; Combination with aPD-1, ORR 8%; CR 2; PR 4 | [116] |

| PF-04518600 | I/II | Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,0.1-3mg/kg, IV, Q2W. Anti-4-1BB,20/100mg, IV, Q4W. | N=57, ORR 3.5%; PR 2; DCR 35% | [118] |

| BMS986178 | I | SD-101 Radiation |

LG-B-NHL | Anti-OX40,0.3mg/kg, IV, Day8.15.22 SD-101,1-8mg, IT, Day8.15.22.29.36 RT, Day1. |

N=29, ORR 31%; CR 4; PR 5 | [120] |

| BMS986178 | I/II | Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

Advanced Solid tumors | Anti-OX40,20-320mg, IV, Q2W Anti-PD-1,240-480mg, IV, Q2W Anti-CTLA-4,1-3mg/kg, IV, Q3W |

N=165, Single agent ORR 0%(n=20), Combination therapy ORR 0-13%(n=145) |

[117] |

| PF-04518600 | I/II | Avelumab UtomilumabRadiation |

Advanced gynecologic malignancies | Anti-OX40,0.3mg/kg, IV, Q2W Anti-PD-L1,10mg/kg, IV, Q2W Anti-4-1BB,20/100mg, IV, Q4W |

N=35,Avelumab+Utomilumab:ORR11%;PR1(n=9),Avelumab+Utomilumab+PF04518600:ORR2.9%,DCR37.1%,(n=35) | [119] |

| 9B12 | I/II | Single agent | Advanced cancer | Anti-OX40,0.1-2mg/kg, IV, Day1,3,5 | N=30, ORR 0%, tumors remission | [121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).