Submitted:

19 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Critical analysis of recent work and benchmarks: We review and synthesize techniques proposed in the literature, showing how approaches have evolved over the past three years and how they align with benchmark design.

- Experimental evaluation of state-of-the-art LLMs: We show that baseline techniques, such as single-shot generation and simple ReAct-style [24] reflection, achieve strong performance on current benchmarks, indicating that these benchmarks may no longer stress the limits of today’s models. This highlights the need for richer, more complex benchmarks to drive further progress.

- Identification of recurring failure modes: By analyzing failed designs in depth, we surface systematic issues such as finite state machine mis-sequencing, handshake protocol drift, and misuse of blocking vs. non-blocking semantics, offering insight into why LLMs struggle with hardware concurrency and temporal reasoning.

2. Prior Work on LLM Based RTL Generation

2.1. Survey Methodology

2.2. Per-Paper Summaries

- AIVRIL

- AssertLLM

- Uses a multi-agent method for specification extraction, signal mapping, and System Verilog Assertion(SVA) generation. Techniques include in-context learning and prompt engineering, with evaluations performed using Formal Property Verification(FPV) tools (e.g., Jasper [32]) against a golden RTL. [33]

- AutoBench

- Automates testbench creation by generating JSON-based scenarios, Verilog drivers, and Python checkers from RTL. Iterative corrections are applied, with syntactic and functional correctness validated while mutating the RTL under test for coverage. Evaluated on Verilog-HumanEval. [34]

- AutoChip

- Early ReAct framework that feeds compiler and simulation errors back to the LLM for self-correction. [35]

- AutoVCoder

- Autosilicon

- Multi-agent framework with dedicated agents for decomposition, implementation, and debugging, augmented by persistent vector-memory, serialized waveforms, and automated testbench generation. Evaluated on VerilogEval, RTLLM, and large-scale open-source designs (CPUs, I/O, accelerators), with PPA analysis via Synopsys Silicon Compiler on TSMC 65 nm technology. [37]

- BetterV

- C2HLSC

- Proposes a flow from C implementations to HLS-compatible C, synthesizable by tools such as Catapult. Stages include function hierarchy analysis, refactoring to HLS-compatible code, and insertion of pragmas via LLM prompts. Benchmarks include cryptographic primitives, randomness tests, and quickSort. Results show correctness and efficiency approaching hand-coded RTL with reduced effort, though evaluation is limited. [40]

- ChipNeMo

- NVIDIA’s 70 B-parameter model domain-adapted for chip design via continued pre-training and instruction alignment. Demonstrations include EDA script generation and bug summarisation. [41]

- CorrectBench

- Uses LLMs as both generator and judge of RT. A pool of imperfect RTLs and testbench scenarios are cross-validated via majority voting with safeguards against over-rejection. [42]

- HLSPilot

- Introduces a set of C-to-HLS optimization strategies tailored to patterns such as nested loops and local arrays. These strategies are applied via in-context learning, where exemplary C/C++–to–HLS prompts guide code refactoring. A design space exploration tool (GenHLSOptimizer) tunes pragma parameters, while software profiling identifies bottlenecks for selective hardware acceleration. [43]

- LHS

- Applies LLMs to improve high level synthesis of deep learning workloads. Error logs guide code refactoring into synthesizable forms with loop optimizations, accumulator insertion, and structural changes. Pragmas for pipelining, unrolling, and partitioning are applied based on synthesis feedback and performance-gain metrics. [44]

- LLM-based Formal Verification

- Represents early work on generating System Verilog Assertion (SVAs) directly from RTL. Consistency between RTL and properties is checked with Formal Property Verification(FPV) tools, leaving resolution of conflicts to designers. [45]

- MAGE

- Multi-agent engine that samples high-temperature RTL candidates, uses checkpoint-based waveform checks, and lets a judge agent steer regeneration, reaching 95.7% functional correctness on VerilogEval-Human. [46]

- Paradigm-based

- Prompt-engineering scheme that classifies each task as combinational or sequential, then applies a tailored “paradigm block” of sub-prompts and tool calls, boosting pass@1 without extra data or tuning. [47]

- PyHDLEval

- Benchmark spanning Verilog and five Python-embedded DSLs; emphasises in-context learning and provides a uniform harness to compare LLMs across HDLs. [48]

- RTLCoder

- Publishes an open dataset for finetuning, plus a lightweight RL fine-tuning recipe (policy-gradient with KL regularisation). Mistral- and DeepSeek-based variants beat GPT-3.5 on VerilogEval. [49]

- RTLFixer

- Specialises in debugging: retrieves compiler-error exemplars and feeds them through ReAct prompting to correct syntax faults, repairing more than 98% of build failures in VerilogEval-Human. [50]

- RTLLM

- Earliest open specification-to-RTL benchmark; groups 30 designs into arithmetic, control, memory, and miscellaneous categories and encourages Chain-of-Thought prompting. [17]

- RTL-Repo

- Large-scale corpus of 4 000 multi-file GitHub projects with full context for code-completion evaluation, stressing the long-context reasoning absent from earlier suites. [51]

- VeriAssist

- Self-verifying assistant that iteratively simulates, reasons over waveforms, patches code, and reports FPGA resource utilisation as a quality metric. [52]

- Verigen

- Among the early works in supervised fine-tune of CodeGen-16B on curated GitHub and textbook data; shows that domain data alone can outperform GPT-3.5 on HDLBits completion. [53]

- VeriOpt

- Employs a multi-agent workflow with planning, programming, reviewing, and evaluation roles. Its key contribution lies in PPA-aware prompting, incorporating techniques such as clock gating, power gating, resource sharing, FSM encoding, pipelining, and loop unrolling. Multi-modal feedback—synthesis reports, timing diagrams, and hardware metrics—is fed back to the LLM, enabling optimization for power, performance, and area. [54]

- VeriReason

- Adds human-style reasoning traces and high-quality testbenches, then fine-tunes Qwen 2.5 models using Guided Reward Proximal Optimisation; evaluated on VerilogEval. [55]

- VerilogCoder

- Task-Circuit Relation Graph planner with four collaborating agents (planner, coder, verifier, AST-tracer). AST (Abstract Syntex Tree) back-tracing pinpoints faulty signals before regeneration. Evaluated on VerilogEval. [56]

- VerilogEval

- Widely used benchmark offering code-completion and spec-to-RTL tasks plus reference testbenches; later releases add a failure taxonomy and in-context prompts. [16].

2.3. Technique Taxonomy

2.4. Observations

- Fine-tuning as a starting point. Early systems such as Verigen, AutoVCoder, BetterV, and ChipNeMo rely primarily on supervised fine-tuning over GitHub-style datasets. More recent work (e.g., VeriReason, RTLCoder) incorporates RL to improve functional correctness on benchmark suites like VerilogEval.

- Rise of agentic frameworks. Projects such as MAGE and VerilogCoder demonstrate that multi-agent orchestration with simulation feedback can outperform monolithic prompting. This trend extends to AssertLLM (multi-role pipeline for SVA generation), VeriOpt (PPA-aware agent loop), and CorrectBench (LLM-as-generator-and-judge). A key challenge is enabling agents to reason collectively over a shared context.

- Retrieval and in-context learning address edge cases. Systems like AutoVCoder and RTLFixer incorporate RAG to retrieve relevant design examples or compiler-error templates. PyHDLEval extends this to multiple Python based DSLs. Recent HLS-oriented work (C2HLSC, HLSPilot, LHS) relies heavily on in-context strategies and synthesis-feedback prompting to refactor C code, while VeriOpt incorporates exemplar-guided design optimizations.

- Debugging strategies are becoming more sophisticated. Early work relied on binary pass/fail simulation outcomes. Recent methods integrate Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) back-tracing (VerilogCoder), checkpoint-based waveform inspection (MAGE), and pattern-matching against compiler diagnostics (RTLFixer). AutoBench and CorrectBench add iterative correction and voting-based self-judgment, while VeriOpt leverages synthesis reports and timing diagrams for reflective corrections. Nevertheless, accurate fault attribution remains an open problem.

- Post-RTL metrics are underexplored. BetterV introduces design-time metrics such as Yosys node count and SAT solve time. VeriAssist adds FPGA resource utilization. VeriOpt advances this trend further with explicit PPA-aware prompting, while LHS optimizes for latency/area trade-offs. However, systematic integration of such post-RTL metrics remains limited.

- Benchmarks shape progress. VerilogEval and RTLLM remain the dominant evaluation suites, while HDLBits and RTL_Repo expand test coverage to code-completion and long-context inference. AssertLLM contributes a dedicated SVA benchmark. Still, few datasets stress synthesis quality, timing closure, or end-to-end hardware viability.

2.5. Evolution Over Time

- 2023. Initial efforts such as ChipChat and ChipNeMo demonstrated the feasibility of applying large language models to hardware design tasks, including code generation and EDA tool interaction. These systems primarily focused on exploratory use cases and domain adaptation of general-purpose models.

- Early 2024. Projects such as Verigen and BetterV established a baseline for RTL generation using LLMs through domain-specific supervised fine-tuning and basic prompt engineering. These approaches improved performance on benchmark tasks but lacked structured reasoning or interactive workflows.

- Mid 2024. Research shifted toward more structured prompting methods, including instruction prompting, chain-of-thought reasoning, in-context learning, and retrieval-augmented generation. Most systems in this phase remained single-agent, relying on static prompt composition or few-shot exemplars with limited use of external tool feedback. Notable examples include AutoVCoder, RTLFixer, and PyHDLEval.

- Late 2024. Agentic execution emerged as a dominant paradigm, with systems such as MAGE, VerilogCoder, and AIVRIL introducing multi-agent workflows capable of decomposing tasks, coordinating generation and verification, and iteratively refining outputs based on simulation and analysis. AutoBench extended this line of work to automatic testbench generation, integrating iterative correction and evaluation strategies.

-

2025. Specialized agentic methods expanded to verification and debugging. AssertLLM applied multi-agent pipelines for specification extraction and assertion generation, while CorrectBench introduced voting-based self-judgment to sidestep the need for a golden DUT. These works marked a shift toward autonomous verification flows beyond RTL generation.High-Level Synthesis (HLS) emerged as a parallel research trajectory. C2HLSC and HLSPilot demonstrated how LLMs can refactor C/C++ code into HLS-compatible implementations with pragma insertion and design space exploration. LHS further advanced this direction by integrating synthesis feedback to optimize latency/area trade-offs in deep learning accelerators.Reinforcement learning was integrated into the RTL generation workflow, with projects such as VeriReason and RTLCoder applying policy-gradient or reward-based fine-tuning to optimize model outputs for functional correctness and benchmark performance, particularly on suites like VerilogEval.

3. Evaluation of Benchmarks with State-of-the-Art LLMs

- RQ1: How well do current LLMs perform on prompt-to-RTL generation when evaluated without auxiliary agents, planning mechanisms, or external optimization?

- RQ2: To what extent do observed failures stem from intrinsic model limitations versus artifacts of benchmark design (e.g., incomplete prompts, incorrect or underspecified testbenches)?

- RQ3: Are existing benchmarks sufficiently well designed to provide a reliable and comprehensive measure of RTL generation capability, or do they require refinement to more accurately capture task challenges?

3.1. Benchmarks

3.2. Tool Integration via Model Context Protocol (MCP)

3.3. Agentic System Architecture

3.4. Results

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. RTLLM

- Specification ambiguity: Prompts leave degrees of freedom (restoring vs. non-restoring, tie-breaking, don’t-care handling), and models often pick a valid but incompatible variant.

- Cycle accuracy: Precise per-cycle sequencing (shift–subtract–restore, final commit) is required; off-by-one or misordered steps corrupt results.

- Bit-width arithmetic: Restoring division needs a 9-bit remainder path and borrow detection; models frequently implement 8-bit compares/subtracts.

- Finalization: The last quotient bit and final remainder must be explicitly committed; this step is often omitted.

- Sign rules: Signed division requires internally, quotient sign via , and remainder sign matching the dividend; frequently mishandled.

- Handshake logic: Misuse of res_ready/res_valid and level vs. edge confusion produce deadlocks or stale outputs.

- State control: Incorrect sequencing of start/active/done leads to premature termination or extra cycles.

- Edge cases: Divide-by-zero, , are often unspecified or incorrectly handled.

- Syntax vs. semantics: Syntactically valid code with semantic errors (e.g., blocking in sequential logic, replacing borrow-detect with simple compare).

- Lack of internal verification: No internal symbolic trace or truth-table reasoning to catch subtle algorithmic mistakes during generation.

4.2. VerilogEval

- Protocol violation: done became level-sensitive, not a one-cycle pulse after three valid bytes.

- Frame misalignment: Without explicit states, frame boundaries drifted, yielding frequent cycle-shifted outputs at valid times.

- In the testbench, this produced widespread mismatches (thousands of incorrect done cycles; hundreds of output miscompares at valid times). The case highlights a broader trend: models often succeed on combinational logic but falter on temporal protocols requiring explicit FSM reasoning and gated validity.

4.3. Observations on Errors Made by LLMs

- Transition priority mistakes: Missing explicit precedence for mutually exclusive conditions (e.g., read vs. write) yields nondeterministic behavior.

- Moore vs. Mealy confusion: Outputs meant to depend on registered state are derived combinationally from inputs, causing glitches.

- Over/under-registering signals: Poor register placement adds latency or instability (e.g., exposing next-state directly as output).

- Missing hysteresis/invariants: Lack of memory of past events (e.g., debouncing) leads to flapping outputs.

- Boundary/off-by-one errors: Incorrect thresholding (> vs. ≥) or counter endpoints violate protocols.

- Handshake timing drift: Valid/ready asserted one cycle early/late desynchronizes modules; overloading a single signal (e.g., done) conflates phases.

- Event vs. level detection: Edge detection used where level is required (or vice versa) causes missed/repeated triggers.

- Asymmetry violations: Treating asymmetric inputs as symmetric breaks intended control policies.

- Algebraic incompleteness: Dropping terms in SOP/POS simplifications passes some tests but fails corners.

- Output-validity contract ignored: Driving outputs outside validity windows risks latching garbage downstream.

- Error-path underspecification: No clear recovery/rollback sequence leads to repeated faults.

- Bit-ordering/shift-direction mistakes: MSB/LSB swaps and left/right confusion misalign data.

- Reset semantics drift: Wrong polarity or missing init causes invalid post-reset states.

- Blocking vs. non-blocking misuse: Using = in sequential logic (or mixing with <=) induces races and sim/synth mismatches.

- State-space oversimplification: Collapsing required states skips timing gaps and induces premature transitions.

4.4. Future Work: Toward Reliable Spec-to-RTL Generation

- Contract-based synthesis: Embedding explicit temporal and structural contracts into the design process can ensure that generated control logic respects precedence rules, handshake timing, and reset semantics by construction.

- Schema-driven specifications: Capturing I/O, signal roles, invariants, and protocol semantics in machine-checkable schemas can reduce ambiguity and provide stronger guardrails against misinterpretation during generation.

- Counterexample-guided refinement: Leveraging simulation and formal verification traces to drive iterative repair can help address subtle corner cases such as off-by-one errors, algebraic incompleteness, and state-space underspecification.

- Automated protocol and invariant checkers: Integrating lightweight protocol monitors and invariant analyzers into the workflow can catch timing drift, invalid outputs, and missing recovery sequences early in the design loop.

- Persistent error memory: Maintaining a record of past errors and their fixes in a structured knowledge base can help prevent recurrence and enable models to learn corrective patterns over time.

- Symbolic and structural reasoning aids: Combining language models with symbolic execution, AST-based debugging, and circuit-graph reasoning may improve robustness in handling concurrency, bit-level manipulations, and complex state machines.

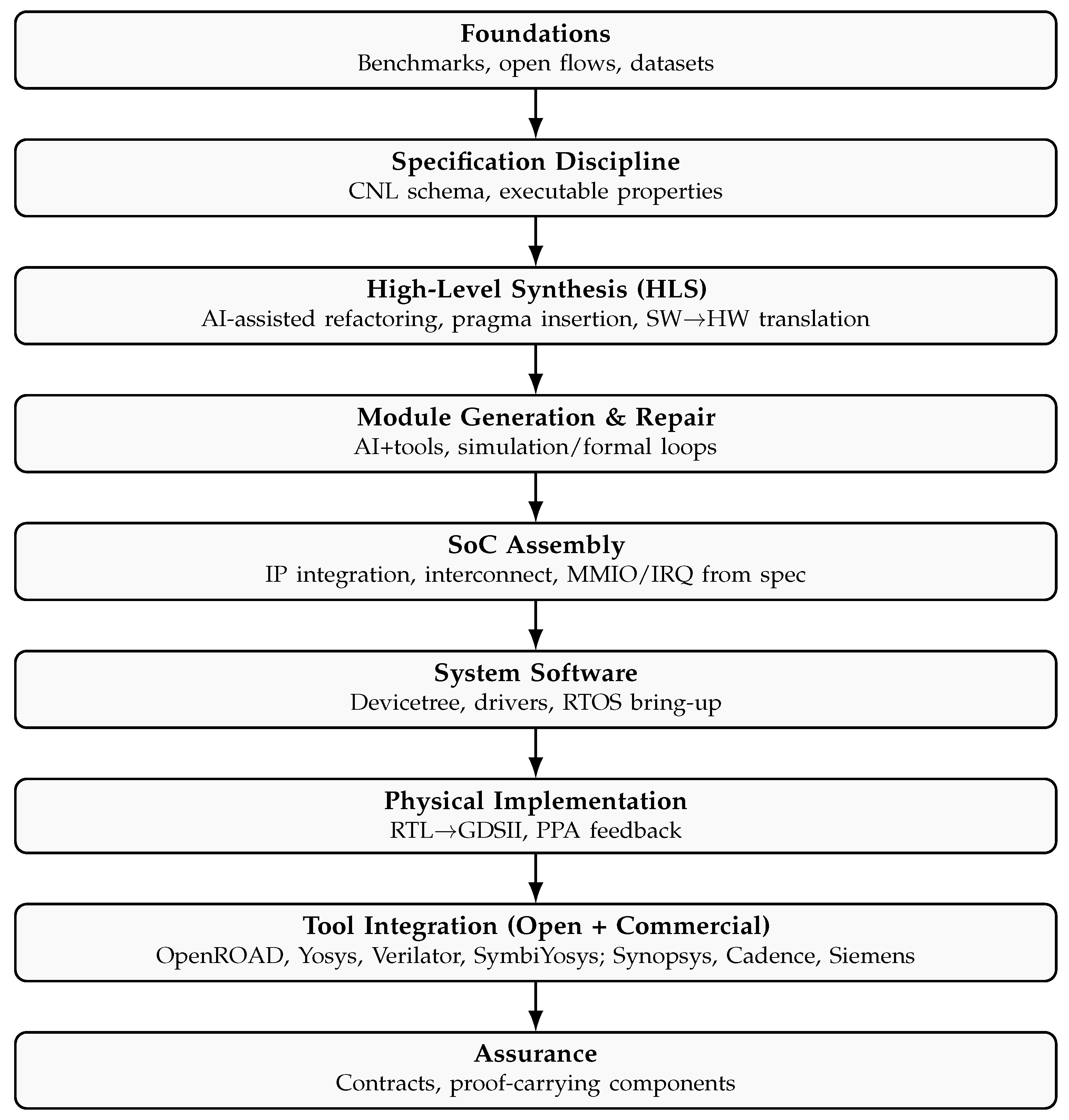

5. Future Work: Toward Natural-Language-to-SoC Design

5.1. Current Landscape and Gaps

5.2. Open Foundations

5.3. Specification Discipline

5.4. AI-Assisted Generation and Repair

5.5. SoC Assembly and Software Interfaces

5.6. Physical Design and PPA-Informed Feedback

5.7. Assurance and Proof-Carrying Design

5.8. Outlook

6. Conclusion

References

- Flynn, M.J.; Luk, W. Computer system design: system-on-chip; John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Dally, W.J.; Turakhia, Y.; Han, S. Domain-specific hardware accelerators. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The OpenROAD Project and contributors. OpenLane. GitHub repository, 2025. An automated RTL to GDSII flow.

- Synopsys, Inc. Fusion Compiler. Synopsys, Inc., 2024. Accessed: September 13, 2025.

- Abdelazeem, A. Cadence-RTL-to-GDSII-Flow. GitHub, 2023.

- Siemens EDA. Aprisa. Siemens EDA, 2025. Accessed: September 13, 2025.

- The OpenROAD Project and contributors. OpenROAD: Open-Source RTL-to-GDSII Flow. GitHub repository, 2025. An open-source RTL-to-GDSII flow for semiconductor digital design.

- Matarazzo, A.; Torlone, R. A survey on large language models with some insights on their capabilities and limitations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.04040. [Google Scholar]

- Schulhoff, S.; Ilie, M.; Balepur, N.; Kahadze, K.; Liu, A.; Si, C.; Li, Y.; Gupta, A.; Han, H.; Schulhoff, S.; et al. The prompt report: a systematic survey of prompt engineering techniques. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.06608. [Google Scholar]

- Schulhoff, S.; Ilie, M.; Balepur, N.; Kahadze, K.; Liu, A.; Si, C.; Li, Y.; Gupta, A.; Han, H.; Schulhoff, S.; et al. The prompt report: a systematic survey of prompt engineering techniques. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.06608. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Treude, C.; Lo, D. LLM-Based Multi-Agent Systems for Software Engineering: Literature Review, Vision, and the Road Ahead. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology 2025, 34, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi, A.; Kongari, B.; Naguru, R.; Pasnoor, S.; Vilipala, S.V. The Rise of Agentic AI: A Review of Definitions, Frameworks, Architectures, Applications, Evaluation Metrics, and Challenges. Future Internet 2025, 17, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Lu, H.; Heng, P.A.; Lam, W. Unveiling the generalization power of fine-tuned large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.09162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Dai, S.; Wei, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Xu, J.; Wen, J.R. Tool learning with large language models: A survey. Frontiers of Computer Science 2025, 19, 198343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.S.; Aggarwal, V. A Technical Survey of Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.04136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckney, N.; Batten, C.; Liu, M.; Ren, H.; Khailany, B. Revisiting verilogeval: A year of improvements in large-language models for hardware code generation. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z. Rtllm: An open-source benchmark for design rtl generation with large language model. In Proceedings of the 2024 29th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 722–727.

- Pan, J.; Zhou, G.; Chang, C.C.; Jacobson, I.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y. A survey of research in large language models for electronic design automation. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2025, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Schwachhofer, D.; Blocklove, J.; Polian, I.; Domanski, P.; Pflüger, D.; Garg, S.; Karri, R.; Sinanoglu, O.; Knechtel, J.; et al. Large Language Models (LLMs) for Electronic Design Automation (EDA). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.20030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, W.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qu, G.; Li, A. MCP4EDA: LLM-Powered Model Context Protocol RTL-to-GDSII Automation with Backend Aware Synthesis Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.19570. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wong, S.Z.; Wan, G.W.; Wang, X.; Yang, J. EDA-Debugger: An LLM-Based Framework for Automated EDA Runtime Issue Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2025 26th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–7.

- Wu, H.; He, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Zheng, S.; Zheng, H.; Yu, B. Chateda: A large language model powered autonomous agent for eda. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024, 43, 3184–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Au, H.I.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y. AutoEDA: Enabling EDA Flow Automation through Microservice-Based LLM Agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.01012. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2023.

- Purini, S.; Garg, S.; Gaur, M.; Bhat, S.; Ravindran, A. ArchXBench: A Complex Digital Systems Benchmark Suite for LLM Driven RTL Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Machine Learning for CAD (MLCAD), Santa Cruz, California, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Rozière, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.L.; Lample, G.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Kossakowski, K.; et al. Code Llama: Open Foundation Models for Code. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12950. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.19437. [Google Scholar]

- Team, G.; et al. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen Technical Report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, H.; Gaillardon, P.E.; Tenace, V.; et al. Aivril: Ai-driven rtl generation with verification in-the-loop. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11411. [Google Scholar]

- Cadence Design Systems. Jasper Formal Property Verification App. Website, 2024. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- Yan, Z.; Fang, W.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, H. Assertllm: Generating hardware verification assertions from design specifications via multi-llms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference, 2025, pp. 614–621.

- Qiu, R.; Zhang, G.L.; Drechsler, R.; Schlichtmann, U.; Li, B. Autobench: Automatic testbench generation and evaluation using llms for hdl design. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Machine Learning for CAD, 2024, pp. 1–10.

- Thakur, S.; Blocklove, J.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Garg, S.; Karri, R. Autochip: Automating hdl generation using llm feedback. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.04887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Z.; Ding, W.; Hou, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, C.; Guo, M. Autovcoder: A systematic framework for automated verilog code generation using llms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 42nd International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD). IEEE, 2024, pp. 162–169.

- Li, C.; Chen, C.; Pan, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Chang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Autosilicon: Scaling up rtl design generation capability of large language models. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; the Yosys Community. Yosys Open Synthesis Suite (Yosys). GitHub repository, 2025. Framework for Verilog RTL synthesis. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- Pei, Z.; Zhen, H.L.; Yuan, M.; Huang, Y.; Yu, B. Betterv: Controlled verilog generation with discriminative guidance. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.03375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collini, L.; Garg, S.; Karri, R. C2HLSC: Leveraging large language models to bridge the software-to-hardware design gap. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ene, T.D.; Kirby, R.; Cheng, C.; Pinckney, N.; Liang, R.; Alben, J.; Anand, H.; Banerjee, S.; Bayraktaroglu, I.; et al. Chipnemo: Domain-adapted llms for chip design. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.00176. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Zhang, G.L.; Drechsler, R.; Schlichtmann, U.; Li, B. Correctbench: Automatic testbench generation with functional self-correction using llms for hdl design. In Proceedings of the 2025 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference (DATE). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–7.

- Xiong, C.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Li, X. Hlspilot: Llm-based high-level synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 43rd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, 2024, pp. 1–9.

- Reddy, E.B.E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Sarmah, A.; Nongpoh, F.; Maddala, K.; Karfa, C. Lhs: Llm assisted efficient high-level synthesis of deep learning tasks. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenes-Vera, M.; Martonosi, M.; Wentzlaff, D. Using llms to facilitate formal verification of rtl. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.09437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, J. Mage: A multi-agent engine for automated rtl code generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.07822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, G.L.; Yin, X.; Zhuo, C.; Schlichtmann, U. Paradigm-based automatic hdl code generation using llms. In Proceedings of the 2025 26th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED). IEEE, 2025, pp. 1–8.

- Batten, C.; Pinckney, N.; Liu, M.; Ren, H.; Khailany, B. Pyhdl-eval: An llm evaluation framework for hardware design using python-embedded dsls. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Machine Learning for CAD, 2024, pp. 1–17.

- Liu, S.; Fang, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z. Rtlcoder: Fully open-source and efficient llm-assisted rtl code generation technique. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.; Liu, M.; Ren, H. Rtlfixer: Automatically fixing rtl syntax errors with large language model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Allam, A.; Shalan, M. Rtl-repo: A benchmark for evaluating llms on large-scale rtl design projects. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE LLM Aided Design Workshop (LAD). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5.

- Huang, H.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Ding, K.; Zhao, J. Towards llm-powered verilog rtl assistant: Self-verification and self-correction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00115. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, S.; Ahmad, B.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Karri, R.; Garg, S. Verigen: A large language model for verilog code generation. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems 2024, 29, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnia, K.; Garcia, A.; Farheen, T.; Rahman, S. VeriOpt: PPA-Aware High-Quality Verilog Generation via Multi-Role LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.14776. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, G.; Ye, W.; Qu, G.; Li, A. VeriReason: Reinforcement Learning with Testbench Feedback for Reasoning-Enhanced Verilog Generation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.11849. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.T.; Ren, H.; Khailany, B. Verilogcoder: Autonomous verilog coding agents with graph-based planning and abstract syntax tree (ast)-based waveform tracing tool. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 300–307.

- Williams, S. Icarus Verilog. GitHub repository, 2023. Open-source Verilog compiler. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- Anthropic Team. Model Context Protocol (MCP), 2024. Initial release in November 2024. Accessed on 2025-09-09.

- Snyder, W.; the Verilator Community. Verilator: Fast Verilog/SystemVerilog Simulator. GitHub repository, 2025. Open-source SystemVerilog simulator and lint system. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- YosysHQ.; contributors. SymbiYosys (sby). GitHub repository, 2025. Front-end for Yosys-based formal verification flows. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- LangChain-ai. LangGraph: A library for building robust and stateful multi-actor applications with LangChain. GitHub repository, 2024. Accessed: 2025-09-15.

- Purini, S.; Garg, S.; Gaur, M.; Bhat, S.; Ravindran, A. ArchXBench: A Complex Digital Systems Benchmark Suite for LLM Driven RTL Synthesis, 2025.

| Paper | FT | RL | Ag | RAG | Dbg | Beyond | BM | PE |

| MAGE (1) | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| VerilogCoder (2) | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Aivril (3) | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| RTLFixer (4) | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| AutoVCoder (5) | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| PyHDLEval (6) | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| VeriReason (7) | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Verigen (8) | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Autochip (9) | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| BetterV (10) | ✓ | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × |

| VerilogEval (11) | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| RTLLM (12) | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| RTLCoder (13) | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| RTL_repo (14) | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| VeriAssist (15) | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| ChipNeMo (16) | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Paradigm-based (17) | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| AssertLLM (18) | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| AutoBench (19) | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| CorrectBench (20) | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| C2HLSC (21) | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

| HLSPilot (22) | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

| LHS (23) | × | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| LLM-based Formal Verification (24) | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| VeriOpt (25) | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Autosilicon (26) | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Model | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-4.1 | $2.00 | $8.00 |

| GPT-4.1-mini | $0.40 | $1.60 |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | $3.00 | $15.00 |

| Name | GPT 4.1 | GPT 4.1mini | Sonnet 4 | |||

| Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | |

| Prob001_zero | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob002_m2014_q4i | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob003_step_one | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob004_vector2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob005_notgate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob006_vectorr | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob007_wire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob008_m2014_q4h | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob009_popcount3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob010_mt2015_q4a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob011_norgate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob012_xnorgate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob013_m2014_q4e | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob014_andgate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob015_vector1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob016_m2014_q4j | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob017_mux2to1v | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob018_mux256to1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob019_m2014_q4f | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob020_mt2015_eq2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob021_mux256to1v | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob022_mux2to1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob023_vector100r | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob024_hadd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob025_reduction | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob026_alwaysblock1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob027_fadd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob028_m2014_q4a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob029_m2014_q4g | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob030_popcount255 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob031_dff | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob032_vector0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob033_ece241_2014_q1c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob034_dff8 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob035_count1to10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob036_ringer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob037_review2015_count1k | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob038_count15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob039_always_if | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob040_count10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob041_dff8r | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob042_vector4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob043_vector5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob044_vectorgates | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob045_edgedetect2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob046_dff8p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob047_dff8ar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob048_m2014_q4c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob049_m2014_q4b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob050_kmap1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob051_gates4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob052_gates100 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob053_m2014_q4d | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob054_edgedetect | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob055_conditional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob056_ece241_2013_q7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob057_kmap2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Prob058_alwaysblock2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob059_wire4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob060_m2014_q4k | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob061_2014_q4a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob062_bugs_mux2 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob063_review2015_shiftcount | 1 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob064_vector3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob065_7420 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob066_edgecapture | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Prob067_countslow | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob068_countbcd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob069_truthtable1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob070_ece241_2013_q2 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob071_always_casez | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob072_thermostat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob073_dff16e | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob074_ece241_2014_q4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob075_counter_2bc | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Name | GPT 4.1 | GPT 4.1mini | Sonnet 4 | |||

| Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | |

| Prob076_always_case | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob077_wire_decl | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob078_dualedge | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob079_fsm3onehot | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob080_timer | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob081_7458 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob082_lfsr32 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob083_mt2015_q4b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob084_ece241_2013_q12 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob085_shift4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob086_lfsr5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob087_gates | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob088_ece241_2014_q5b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob089_ece241_2014_q5a | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob090_circuit1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob091_2012_q2b | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob092_gatesv100 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob093_ece241_2014_q3 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob094_gatesv | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Prob095_review2015_fsmshift | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob096_review2015_fsmseq | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob097_mux9to1v | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob098_circuit7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob099_m2014_q6c | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob100_fsm3comb | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob101_circuit4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob102_circuit3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Prob103_circuit2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob104_mt2015_muxdff | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob105_rotate100 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob106_always_nolatches | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob107_fsm1s | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob108_rule90 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob109_fsm1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob110_fsm2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob111_fsm2s | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob112_always_case2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob113_2012_q1g | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob114_bugs_case | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob115_shift18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob116_m2014_q3 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob117_circuit9 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob118_history_shift | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob119_fsm3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob120_fsm3s | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob121_2014_q3bfsm | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob122_kmap4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob123_bugs_addsubz | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob124_rule110 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob125_kmap3 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Prob126_circuit6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob127_lemmings1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob128_fsm_ps2 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Prob129_ece241_2013_q8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob130_circuit5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob131_mt2015_q4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob132_always_if2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob133_2014_q3fsm | 5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| Prob134_2014_q3c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob135_m2014_q6b | 5 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| Prob136_m2014_q6 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob137_fsm_serial | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Prob138_2012_q2fsm | 1 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob139_2013_q2bfsm | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob140_fsm_hdlc | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob141_count_clock | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob142_lemmings2 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob143_fsm_onehot | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob144_conwaylife | 1 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob145_circuit8 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob146_fsm_serialdata | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob147_circuit10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob148_2013_q2afsm | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob149_ece241_2013_q4 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob150_review2015_fsmonehot | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob151_review2015_fsm | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob152_lemmings3 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Prob153_gshare | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Prob154_fsm_ps2data | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob155_lemmings4 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 10 |

| Prob156_review2015_fancytimer | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Name | GPT 4.1 | GPT 4.1mini | Sonnet 4 | |||

| Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | Baseline | Agentic | |

| Arithmetic | ||||||

| comparator_4bit | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| comparator_3bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| accumulator | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| adder_pipe_64bit | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| adder_bcd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| adder_16bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| adder_32bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| adder_8bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| sub_64bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| multi_8bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| multi_booth_8bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| multi_pipe_8bit | 2 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| multi_pipe_4bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| multi_16bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| fixed_point_sub | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| fixed_point_adder | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| float_multi | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 1 |

| div_16bit | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| radix2_div | 5 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

| Control | ||||||

| sequence_detector | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| fsm | 1 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| ring_counter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| JC_counter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| up_down_counter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| counter_12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Memory | ||||||

| asyn_fifo | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| LIFObuffer | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| LFSR | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| barrel_shifter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| right_shifter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| freq_div | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| freq_divbyeven | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| freq_divbyfraq | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| freq_divbyodd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| signal_generator | 5 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 10 |

| square_wave | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| edge_detect | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| calendar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| serial2parallel | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| synchronizer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| pulse_detect | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| width_8to16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| traffic_light | 5 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| parallel2serial | 1 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| RISC-V/ROM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| RISC-V/clkgen | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RISC-V/alu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| RISC-V/instr_reg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RISC-V/RAM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RISC-V/pe | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Error Type | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Transition priority | Ambiguous handling of mutually exclusive conditions | Nondeterminism, conflicts |

| Moore/Mealy confusion | Outputs derived from inputs instead of registered state | Glitches, unstable signals |

| Over/under-registering | Misplaced pipeline/register boundaries | Extra latency or instability |

| Missing hysteresis | No memory of past events (e.g., debounce) | Flapping outputs |

| Boundary/off-by-one | Incorrect counter/timer comparisons | Protocol violations by cycle |

| Handshake drift | Misaligned valid/ready | Desynchronization, data loss |

| Event vs. level | Edge used where level needed (or vice versa) | Missed/repeated triggers |

| Asymmetry violation | Treating asymmetric inputs as symmetric | Wrong transition gating |

| Algebraic incompleteness | Incorrect Boolean simplification | Corner-case failures |

| Output-validity contract | Driving outputs outside valid window | Downstream latches invalid data |

| Error-path underspecified | No recovery after fault | Re-triggered errors |

| Bit-ordering/shifts | MSB/LSB swaps, wrong shift direction | Misaligned/corrupted data |

| Reset semantics drift | Wrong polarity/init | Invalid post-reset state |

| Blocking/non-blocking | = in sequential or mixing with <= | Races, sim/synth mismatch |

| State-space oversimplified | Missing required FSM states | Premature transitions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).