1. Introduction

Virtual clinics have been increasingly used as part of modern healthcare. There was a step change in the use of virtual clinics around the time of COVID and are now established as a part of normal care. The NHS moved to a contractual arrangement with Attend Anywhere to provide video software that supported the appointments. However, the use of telephone to conduct the appointments remains more popular than the use of such software. By whatever means they are provided, virtual appointments are widely accepted as being convenient [

1] and they are popular with patients.[

2,

3] Their outcomes have been less well established.

When virtual appointments were first provided, the benefit was not based on reduction in travel time or convenience, but the need for a consultation that was not face to face during the time of COVID [

4]. It was an essential part of infection control. In the time since COVID, virtual appointments continued to be used because they are more convenient. There was an assumption that they also led to less travelling thereby reducing the carbon footprint of healthcare. While work has been done to establish that they actually lead to less travelling for the initial appointment,[

5,

6,

7] some have hypothesised that because Doctors are less confident about the information in a virtual appointment, they will compensate by ordering more investigations and increased follow up from the initial virtual appointment [

8]. It is suggested that the inability to examine patients will lead to more investigation. Offiah et al indicated that there were fewer investigations done after Virtual Appointments but the study was during COVID and couldn’t account for selection bias.[

9] Were virtual appointments to lead to more investigations, travelling distances might actually be higher and the appointments neither save time nor reduce the carbon footprint of healthcare. This work evaluates whether virtual clinic appointments lead to more investigations and thus increased total travel distance and whether the care provided by virtual appointments was equitable with face to face visits. Previous published work has indicated that Virtual appointments are equitable with face to face appointments in terms of value and information.[

10] Further work is needed to establish whether investigation for both groups is equitable and is addressed in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of 9,445 patients who attended either virtual (4672 patients) or face to face (4773 patients) cardiac clinic appointments. The appointments were allocated according to space in the clinic rather than patient preference. The booking team indicated that there was no selection criteria applied to the appointment selection. We retrospectively gathered data on the number of tests ordered and distance travelled for the cohorts. We also gathered data on the demographics of the patients to establish that the 2 groups were matched.

Ordering of the tests was completed at the time of the appointment by the Cardiologist. Orders are all electronic and can be tracked and linked to the investigation that is completed. Investigations are resulted electronically and so the timing of the test is available from available data retrospectively. The demographic details of the patient are held electronically and checked at the time of attendance. These details include a post code and this was used for calculation of distance travelled.

2.2. Setting

Participants were seen in either face to face clinic or virtual clinic appointments at the outpatient clinics of the Trust. Virtual appointments could be video or telephone.

2.3. Time Scale of Data

The study included data from 9445 patients seen during 2023 to 25. Data from earlier years was accessed and is available. However, that time was influenced by the COVID pandemic and movement restrictions. The data from this time was not included as there was a potential for bias around travel. The last travel restriction in the UK was lifted in March 2022 [

11] and there were no travel restrictions by 2023 with society having returned to normal behaviours. The study was restricted to a stable time period where restrictions were absent and the clinics ran without any changes to the format or the booking arrangements.

2.4. Participants

Participants were allocated by the booking teams between virtual and face to face clinic appointments from a shared pool of new referrals from either GP, A+E or inpatient referrals. The booking teams indicated that they did not select patients for slots in clinics, but that patients were allocated a slot according to availability. This would be expected to lead to a random distribution of patients between virtual and face to face clinics. Further testing of that assumption will be conducted using demographics of patients.

The study was conducted retrospectively and consequently patients could not be consented for their inclusion in the data. Individual patient data was not identifiable.

2.4. Data Source

Data within the Trust is collected as a component of the process of booking and clinical appointments with patients. The booking clerks use PAS (Patient Administration System) to allocate and book patients. Consultants use the Trust Electronic Patient Record System (based on Altera Sunrise) to record the consultation and order tests. Most tests are resulted directly into the EPR system. Cardiac specific tests such as ECG are recorded within PRISM which is an electronic system specific to cardiac investigations. Data from all these systems could be accessed and pulled to analyse for the purposes of this study.

All tests ordered under the consultant cardiologist who saw the participant were assumed to be related to clinic appointments and counted. Distance travelled was calculated using the postcodes patients had given as current living address at the time of the appointment being booked. If 2 tests were conducted on the same day they were assumed to be done in a single visit such that travel was only counted once for the 2 tests.

Validation work to ensure that these assumptions were appropriate was completed on a random selection of 50 patients. Discrepancies were investigated initially to correct the search methodology and later to verify its accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Allocation of Appointments

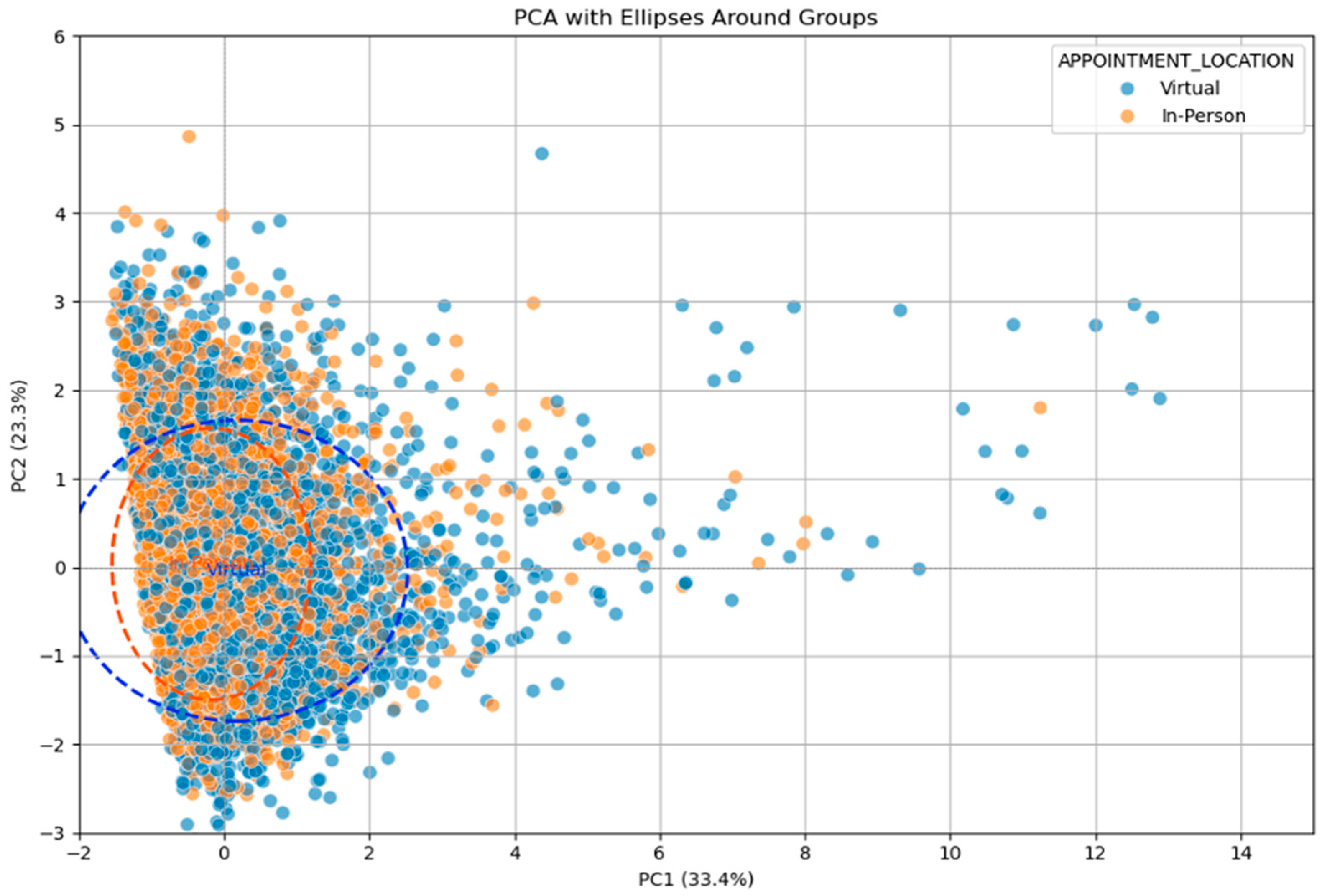

The allocation of patients between virtual and face to face appointments was considered to be non-selected by the booking team. However, logically people who have large distances to travel are likely to ask for virtual appointments more than the ones who live next to the hospital. Whilst there is no policy or attempt to implement this strategically, we gathered data on the 2 groups and performed a Principle Component Analysis (PCA) to examine the similarity of the groups. The booking clerks had indicated there was no process for selection of patients between Virtual and Face to Face appointment. The PCA however indicates there is a difference between the 2 groups. The Virtual group of patients is more likely to travel further (

Figure 1). This is a small effect however and there is a high degree of similarity between patients.

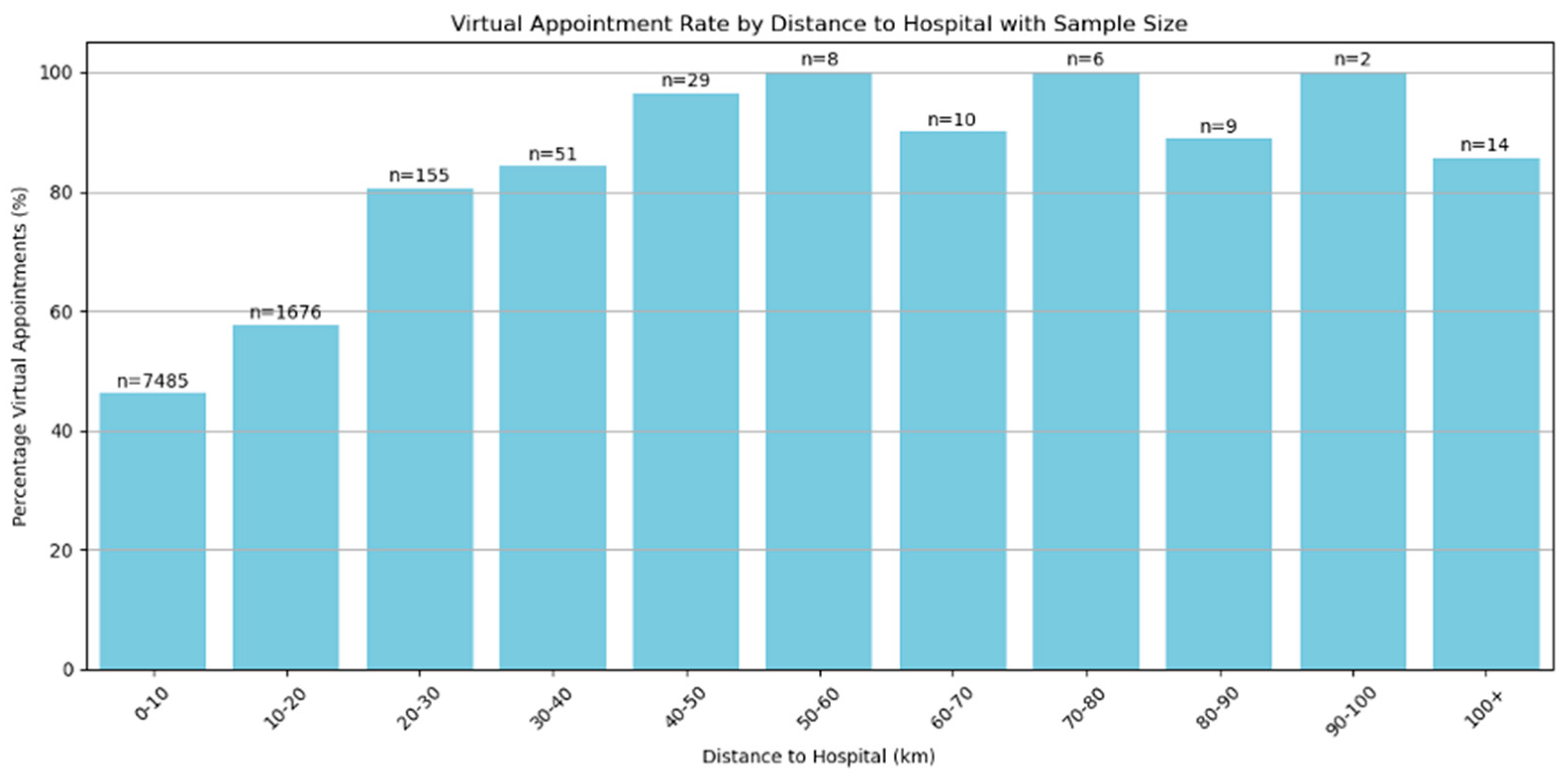

When travelling distances are small, there is little difference in the allocation of appointments between virtual and face to face (

Figure 2). Only when distances exceed 20km does the difference become important. However, there were only 284 patients from the total study population of 9445 (3.1%) who travelled over 20km for an appointment.

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

Is there a difference in groups virtual and in person patients.

3.3. Allocation of Appointments

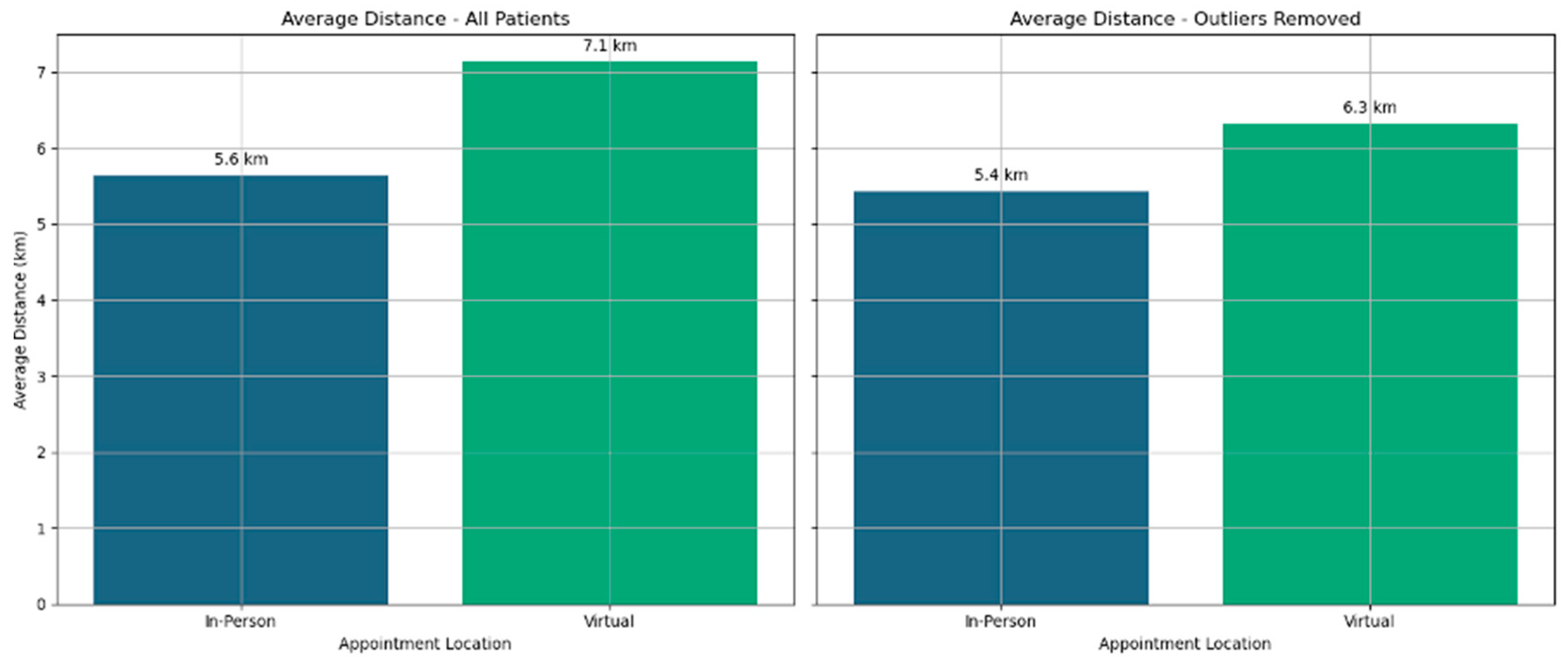

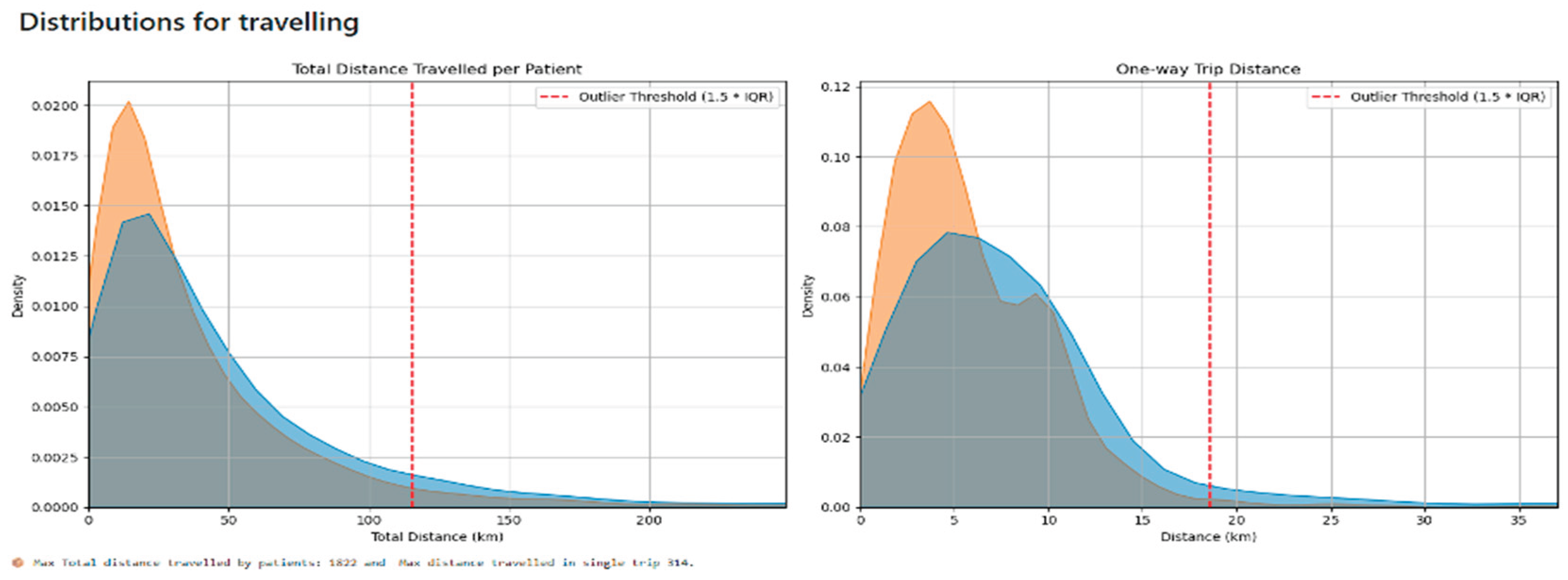

Distance travelled by patients was typically under 20km. Just a very small number of patients travelled large distances and they were likely to represent a very different population from the main cohort of patients. Potentially they were no longer living in the area but attending a review after an emergency appointment. Validation work could not establish the reasons for the larger travelling distance as it was rarely recorded in the records. Calculation of the distance travelled by patients was completed for all patients. To reduce the effect of extreme outliers for distance travelled, the extreme outliers were excluded and averaged distances travelled were also calculated. (

Figure 3). Distance for patients who attended virtually was higher in both calculations.

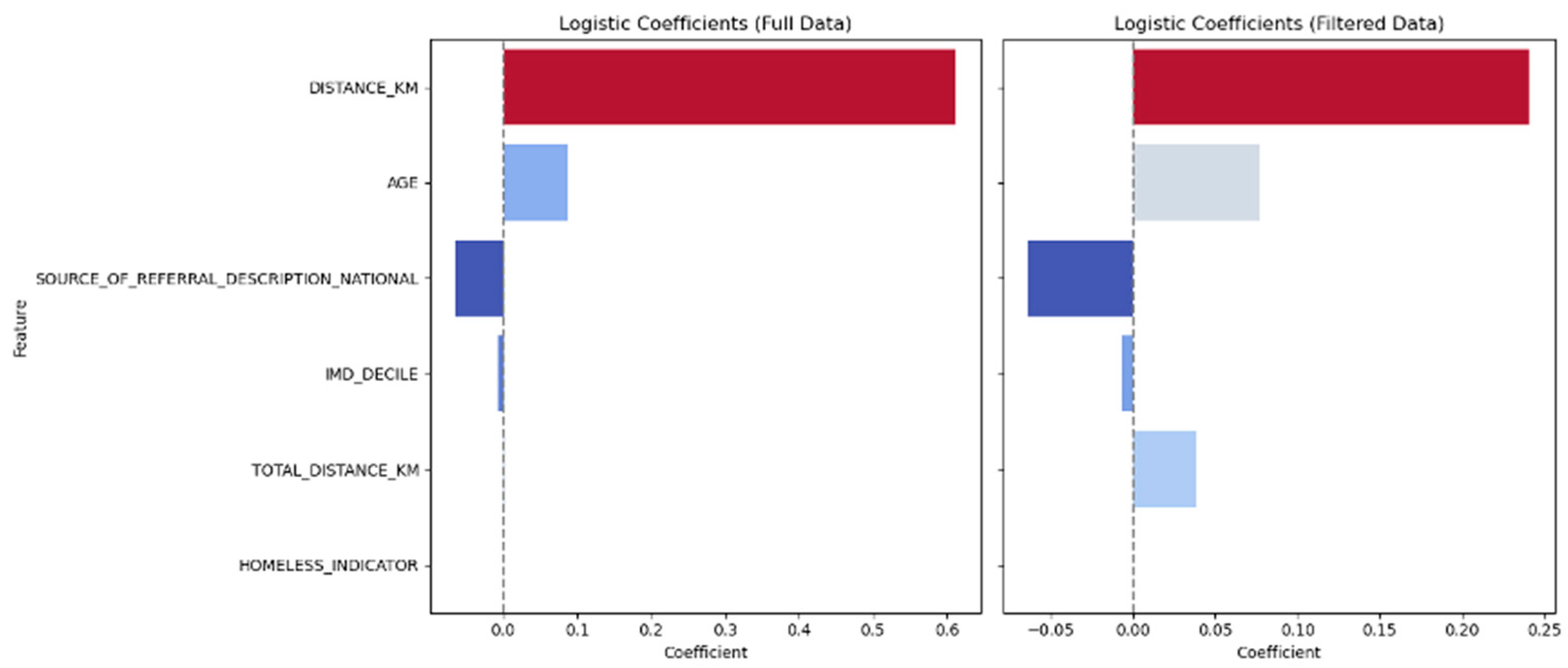

Further analysis of the differences between Virtual and Face to Face appointments shows that there is a significant difference between the 2 groups for distance travelled but not for age, type of referral, frailty and being homeless. This remains true after removal of large distance outliers (

Figure 4)

3.4. Number of Investigations Performed

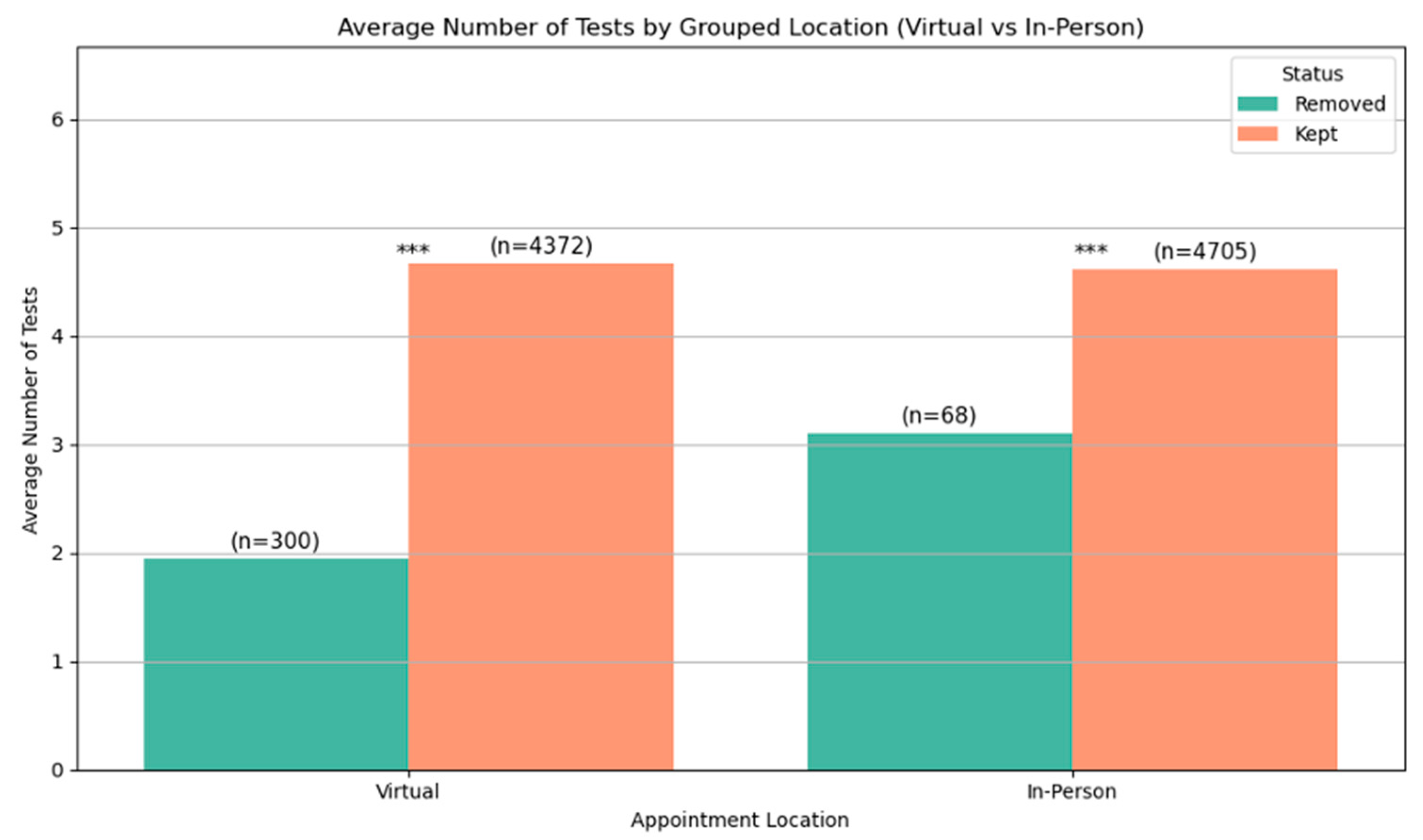

The number of investigations performed after each appointment type was accessed and is represented in

Figure 5. The average number of investigations performed was the same for both Virtual and Face to Face patients. Analysis using Welchs T Test demonstrates statistical significance of less than 0.05. Welchs T Test was used as it does not require equal sample sizes. Patients who were outliers for distance travelled were excluded from the analysis, but their data is represented for comparison.

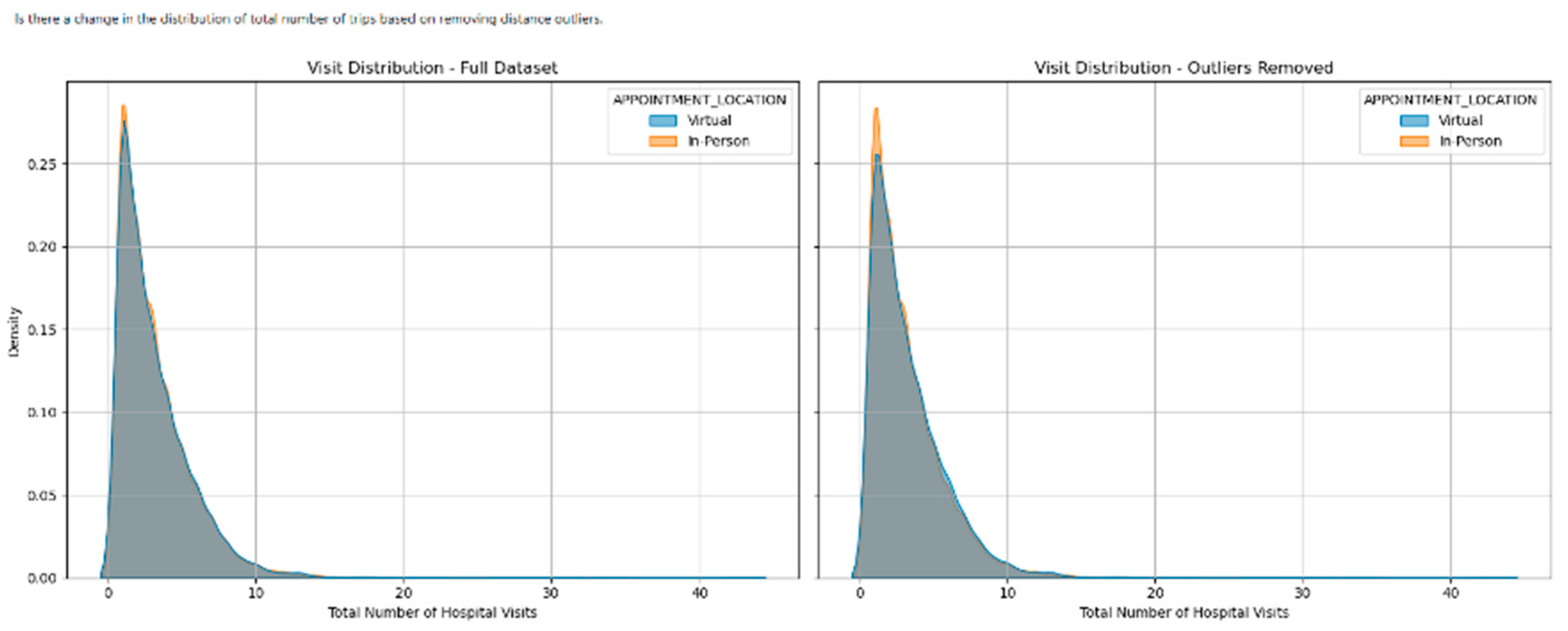

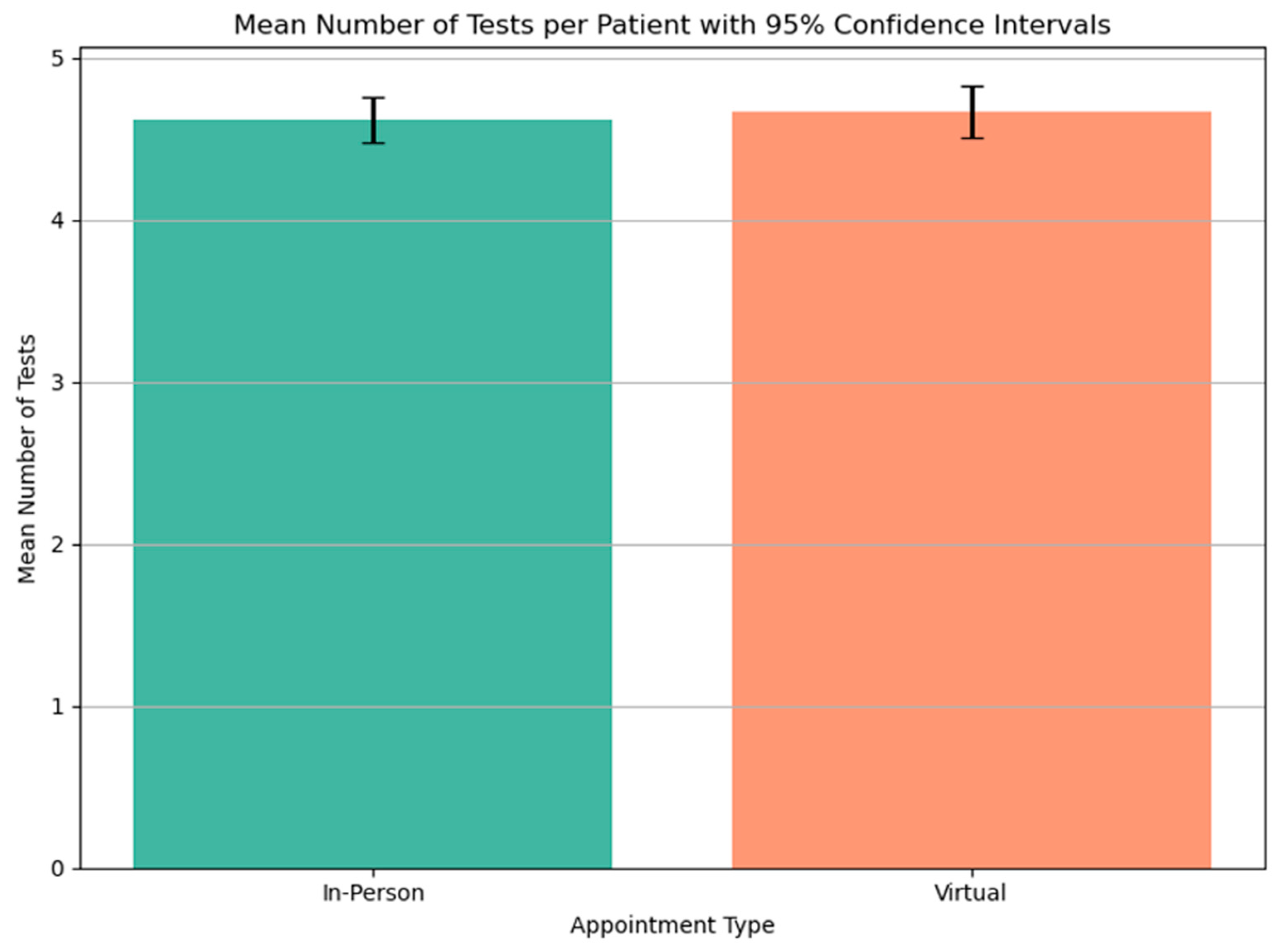

3.5. Number of Visits

The number of visits for investigations was taken from the total number of investigations performed and corrected for investigations that were performed on the same day. It was common for an ECG to be performed at the same time as another investigation and so patients did not need to travel simply to have an ECG done when they were attending for another test on the same day. The frequency distribution of the number of visits for each group are plotted on

Figure 6. There was no significant difference in the number of visits made by the 2 groups (

Figure 7)

3.5. Distance Traveled

The distance travelled for the tests performed is shown in

Figure 8. The distance travelled is marginally greater for the patients seen in Virtual Clinics because of larger distance (6.4 vs 5.3 km) that they travel to have the investigations performed. The data represented only considers the distance travelled for investigations and does not include the initial consultation where there is no travel for Virtual Clinic attendance.

The total distance travelled by patients in the Virtual Clinic group when considering the initial appointment and the investigations is less than for the Face to Face group because of the initial visit. The total reduction in distance travelled amounts to 5,002 km.

4. Discussion

This study looks at the distances travelled by patients attending virtual cardiac appointments in comparison to those attending Face to Face cardiac appointments. We include 9,445 patients split between the 2 groups.

It was initially considered that patients were randomly distributed between Virtual and Face to Face appointments because of the way that appointments are distributed by the booking clerks. The analysis shows that there is some bias towards patients who live further away. It is likely that the booking clerks do not provide that bias but patients who make contact with the cardiac team and ask for a virtual appointment are then allocated such an appointment. This is a small effect, but because of the patients who live far away, it is evident on PCA.

Other factors that might be expected to have an effect on appointment selection did not show a significant effect. Patients who were old or frail might be more likely to have virtual appointments in order to save them from a difficult journey, but this is not evidenced within our data. Homelessness might also make attendance at a virtual appointment more difficult but again there is no evidence to support this. It is possible that patients who are homeless are simply unable to access virtual services without owning a smartphone, but this cannot be evidenced within this data.

The number of visits made by patients after an initial cardiology appointment is the same whether they are Virtual or Face to Face appointments. This indicates that care is the same between the 2 groups. The cardiology team arranges no increased number of investigations because they didn’t have face to face interaction with the patient. There has been suggestion that investigations are used as a way of examining patients who have not been examined at the initial appointment but that is not evidenced here. Care between the 2 groups is shown to be the same. Other studies have suggested that there may be a reduction in the number of investigations done but the largest of these indicated greater follow up and included many different specialities.[

8,

9]

Consequently, distances travelled by both groups for investigation is shown to be the same. There is an overall reduction in distance travelled by the patients who are initially seen in Virtual Clinic appointments. They will have 1 fewer visit as a consequence of the initial virtual visit and that visit will require no travel. The average number of visits made for investigations was between 3 and 4 for both the virtual and face to face groups. The reduction in travel for the Virtual appointments was around 25% amounting to a reduction of 5,002 km and a carbon saving of 784kg CO2eq (assuming typical car engine types, all cars upper medium and typical public transport usage).

5. Conclusion

This study looks at virtual care within cardiac clinics. Whilst clinics of other disciplines will have other types of clinical work, the nature of decision making is likely to be similar. The process of history taking and decision making will follow similar patterns and as such the study is likely to reflect clinical decision making rather than the specific nature of cardiology. The equitability of care within other clinic types and in other settings is likely to follow similar patterns.

Virtual cardiac appointments are well received by patients.[

2,

3] They offer an alternative to attending a clinic Face to Face. This study indicates that they offer equitable care to patients and don’t lead to additional investigations. However, the initial appointment is only 1 visit out of a sequence. The process of investigation requires the patient attends between 3 and 4 times in-person. The reduction in travelling is therefore relatively small. Co-ordinating the process of investigation could be achieved and might have a greater impact on the reduction in travel than the initial type of appointment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Brian Wood and Martin Farrier; methodology, Brian Wood and Martin Farrier.; validation, Matthew Farrier and Zoubaida Yahia; formal analysis, Matthew Farrier and Brian Wood; data curation, Brian Wood.; writing—original draft preparation, Matthew Farrier.; writing—review and editing, Matthew Farrier and Martin Farrier. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Audit Committee of Wrightington Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust (Cardio/SE/2025-26/05 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not obtained because this data is routinely collected and retrospectively analysed. All data was anonymized.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available by reasonable request by email with the corresponding author Martin Farrier at martin.farrier@wwl.nhs.uk.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the cardiology department and the Cardiology Consultants whose work was the basis for this work. We recognize the time that they committed to advising and assisting. We further acknowledge the administrative teams assistance and their advice on how systems worked and the coding they used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Yao Z, Farag A, Mullineux P, Matthews W, Carimichael M, Barlow C. 82 Out of sight but not out of mind. A district hospital cardiology teleclinic setup… patients’, sustainability and environmental benefits. Heart. 2021 June 1;107(Suppl 1):A66-7. [CrossRef]

- Healy P, McCrone L, Tully R, Flannery E, Flynn A, Cahir C, et al. Virtual outpatient clinic as an alternative to an actual clinic visit after surgical discharge: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Jan;28(1):24–31. [CrossRef]

- Miah S, Dunford C, Edison M, Eldred-Evans D, Gan C, Shah TT, et al. A prospective clinical, cost and environmental analysis of a clinician-led virtual urology clinic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019 Jan;101(1):30–4. [CrossRef]

- Vas V, North S, Rua T, Chilton D, Cashman M, Malhotra B, et al. Delivering outpatient virtual clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic: early evaluation of clinicians’ experiences. BMJ Open Qual. 2022 Jan;11(1):e001313. [CrossRef]

- King J, Poo SX, El-Sayed A, Kabir M, Hiner G, Olabinan O, et al. Towards NHS Zero: greener gastroenterology and the impact of virtual clinics on carbon emissions and patient outcomes. A multisite, observational, cross-sectional study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023;14(4):287–94. [CrossRef]

- Croghan S, Rohan P, Considine S, Salloum A, Smyth L, Ahmad I, et al. Time, cost and carbon-efficiency: a silver lining of COVID era virtual urology clinics? annals. 2021 Sept;103(8):599–603. [CrossRef]

- Paquette S, Lin JC. Outpatient Telemedicine Program in Vascular Surgery Reduces Patient Travel Time, Cost, and Environmental Pollutant Emissions. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2019 Aug 1;59:167–72. [CrossRef]

- Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, Barber J, Thompson S, Jacklin P, et al. Joint teleconsultations (virtual outreach) versus standard outpatient appointments for patients referred by their general practitioner for a specialist opinion: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 June 8;359(9322):1961–8. [CrossRef]

- Offiah G, O’Connor C, Waters M, Hickey N, Loo B, Moore D, et al. The impact of a virtual cardiology outpatient clinic in the COVID-19 era. Ir J Med Sci. 2022 Apr 1;191(2):553–8. [CrossRef]

- Palen TE, Price D, Shetterly S, Wallace KB. Comparing virtual consults to traditional consults using an electronic health record: an observational case–control study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2012 July 8;12(1):65. [CrossRef]

- Department for Transport. All COVID-19 travel restrictions removed in the UK. Available from: All COVID-19 travel restrictions removed in the UK –.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).