1. Introduction

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) is the second and third most common cancer in women and men [

1] and currently the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [

2]. Its particularity is that colonoscopy, the gold standard for its diagnosis, is also the treatment for stage 0 colon cancers that have not grown beyond the inner lining of the colon, as it is possible to remove polyps or cancerous areas by a local excision during the colonoscopy. This dual use of colonoscopy means that even if CRC were diagnosed by another method, a patient with CRC should undergo a colonoscopy to evaluate the extent of the cancer and/or remove the cancerous areas that can be removed during the procedure.

Its prognosis is strongly linked to early detection, yet screening and diagnostic strategies remain constrained by resource limitations, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In Chile, the challenge is critical: colonoscopy waiting times for symptomatic patients in public hospitals often exceed one year, significantly delaying diagnosis and reducing survival rates. Current screening is done by doctors, who refer symptomatic patients to hospitals, where a colonoscopy is typically prescribed. Consequently, many patients undergo unnecessary colonoscopies, while others at high risk remain undiagnosed, because no global screening (even based on a single FIT test) is proposed.

Indeed, on top of being invasive and not harmless, colonoscopies are expensive and resource-intensive: the cost of a colonoscopy ranges from around

$100 to over

$4,500 USD, depending on the country and whether it is performed in the private or public sector [

3,

4]. However, several other CRC detection methods exist that look for the presence of blood in stool [

5] such as Faecal immunochemical tests (FIT). They are:

Very simple to perform: a stool sample can be collected at home in a jar and sent to a lab without any prior preparation or diet,

Very cheap: the reported average cost of

$3.04, with a range from

$0.83 to

$6.41 per test [

6]) meaning that a FIT test costs around 100x less than a colonoscopy.

Non-invasive: they do not have associated risks, do not require sedation or recovery time.

Immediately available: there is no waiting list for this very cheap test.

However, they are less precise in their diagnosis:

They have a higher False Positive rate (lower specificity) because they test for occult blood in stool, which is not specific to CRC (haemorrhoids can also cause rectal bleeding) and

They have a higher False-Negative rate (lower sensitivity) due to the intermittent bleeding nature of cancerous polyps (cf. Section 1.1 below).

Despite their lower quality (lower specificity and sensitivity), FIT tests have been studied a lot [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12],…]. For general screening purpose on asymptomatic patients, their sensitivity is typically of 73% (i.e., 27% False Negatives) for people with stage 1 CRC and their specificity is around 94% (i.e., 6% False Positives) [

9].

However, it is important to note that most papers focus on using FIT tests to diagnose colorectal cancer, not to determine which people do not have CRC, in order to reduce waiting lists, which is what this paper is about. But for this purpose, the sensitivity of the test is too low. Suppose we want to screen a cohort of 1 000 000 people of which 1 000 have CRC with a single FIT test (as currently done in France [

13]) with 27% False Negatives. This means that 270 persons will receive a falsely negative FIT test, meaning that they will not be contacted for a colonoscopy even though they have CRC.

By reading the literature on FIT tests, we realised that its low sensitivity does not so much come from the test itself, but from the important observation that polyp bleeding is intermittent but could come from manipulation errors, meaning that repeating several FIT tests on the same person may yield different results.

In this paper, we therefore introduce Compound Bayesian Inference (CBI), a Bayesian statistical framework that combines sequential evidence from independent repeated tests to update disease incidence in subsequent sub-cohorts. In this study, we demonstrate —using clinical data— that applying CBI to a four-round FIT protocol shows that urgent colonoscopies are unnecessary for over 85% of symptomatic patients. Moreover, statistical modelling on Chile’s metropolitan region indicates that effective population-level screening could be achieved with as few as 0.01% of the colonoscopies currently needed, representing a paradigm shift for all countries that (including Chile) do not propose global population screening for CRC.

The primary objective of this work is to evaluate the clinical and operational impact of CBI-based screening and prioritization strategies in CRC detection, and to highlight its potential as an interpretable, evidence-based tool for precision medicine.

2. Presentation of the Method

In this paper, we posit (based on published papers) that the irregularity of observed occult blood in patients with confirmed CRC means that different FIT tests on the same patient could yield different results: a FIT test could be positive one day, negative the next day, and positive again the day after, depending on the stage of the CRC or other factors.

2.1. On the Independence of FIT Tests

[

14] showed a Nonuniform distribution of occult blood in feces while [

15] studies Bleeding patterns in colorectal cancer up to the point that [

16] concludes (from a very small sample study) that the immunochemical faecal occult bloodtest is unsuitable for the diagnosis of rectal cancer, due to a low sensitivity of the diagnostic test combined with a slight haemorrhage or intraintestinal degeneration of haemoglobin, inappropriate site and amount of stool sampling, poor preservation of the specimen. A more recent paper [

17] on a larger cohort also “showed a low concordance between daily consecutive [FIT] tests results.”

2.2. Bayesian Analysis of the Results of a FIT Test in the Metropolitan Region of Chile

A recent article [

18] shows that in 2018, the age-standardized incidence of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) in Chile ranges from 14.6/100 000 inhabitants in Region III (Atacama and Coquimbo) to 23.0/100 000 inhabitants in Region XI (Magallanes) with 19.6/100 000 inhabitants for Region XI (Metropolitan area around Santiago, the capital).

Basic Bayesian inference [

19,

20] needs 3 values (called prior knowledge) in order to make obvious predictions, provided the prior knowledge is correct.

If we use as a reference:

the Chilean Metropolitan Region with an observed incidence of CRC of 19.6/100 000 and

-

FIT tests with 73% sensitivity (27% False Negatives) and a 94% specificity (6% False Positives),

It mathematically follows that for every 100 000 inhabitants submitted to a single FIT test:

19.6 are sick, but due to the 27% False Negatives (FN), statistically, 5.29 will falsely test negative (and 14.31 will truly test positive = TP),

99 980.4 are healthy, but due to the 6% False Positives (FP), 5 998.82 will falsely test positive (and 93 981.58 will truly test negative = TN).

So, from the point of view of the tested person who receives a positive FIT test, this person will be among the 14.31 Real Positives or the 5 998.82 False Positives. So this person only has a 0.238% chance to be sick.

Conversely, if a person of Chile’s Metropolitan Region receives a Negative FIT test, this person is among the 93 981.58 True Negatives or the 5.29 False Negatives, meaning that they have a 99.995% probability to be healthy. But in a very large population of several millions, 99.995% probability is not enough to remove all False Negatives.

2.3. Bibliographic Analysis

Contrary to nearly all other papers on the topic, we do not try to diagnose CRC. We propose a new approach to find out which people very probably do not need urgent colonoscopies, in order to allow people at risk to have faster access to colonoscopies. We did not find any papers proposing multiple testing combined with Bayesian inference to assess the probability that patients do not need an urgent colonoscopy, which is one of the key innovative ideas of our paper.

[

21] proposes a similar multi-faecal immunochemical testing strategy, but the authors do not propose to use Bayes’ theorem to infer predictions. The paper describes quite well what we want to do, but with 3 FIT tests (not 4) and with a frequentist analysis, meaning that the authors cannot give precise estimations of the probability that the patients of their study have (or do not have) CRC depending on their number of positive and negative FIT tests. A similar study was also performed with 3 FIT tests, in [

22] and [

17], but here again, Bayesian inference was not used, meaning that the conclusions of the study remain vague. Other papers also propose to perform several FIT tests, but separated by several months during which the state of the patient can evolve, therefore invalidating the purpose of our approach.

2.3. Proposed Compound Bayesian Inference (CBI) and Application to Colonoscopy Priorization

In order to improve on the sensitivity of FIT tests, we propose to use the observation that several tests on the same person could yield different results to propose to combine several FIT tests for determining who urgently needs (or not) a colonoscopy. Here is the mathematics behind our reasoning: after the first FIT test, remember that we computed that being positive meant that the person had a 0.238% chance to have CRC, while being negative meant that the person had 99.995% chance to be healthy (i.e., 0.005% chance to have CRC).

Based on these calculations, we propose to distinguish 2 sub-populations for which we can replace the CRC incidence with the computed probability number:

As the inconclusiveness of FIT tests may stem from intermittent bleeding or bad test processing (which renders the tests independent), we propose exploring the mathematical outcomes of additional FIT tests performed on each subpopulation with their newly associated incidence rates.

The reason why this is interesting is that incidence (and related predictions) will evolve as a sigmoid, and the interesting part of a sigmoid is not its beginning (around 0%) or end (around 100%) part, but its “middle part” where the first derivative has a high value. It seems to us that other researchers have not seen Compound Bayesian Inference performed on independent tests as a way to update prior knowledge as a sigmoid curve.

3. Results

3.1. Application of 4-FIT Compound Bayesian Inference to Colonoscopy Priorization in Chile’s Metropolitan Region

In Germany, CRC screening is done by proposing a colonoscopy to all men above 50 or women above 55 [

23]. In France, a single FIT test is proposed [

13]. In Chile, no screening exists but CRC is the fastest increasing cancer, with studies showing its incidence could increase by 60% in 2030 [

24].

The incidence of CRC for FIT+ people is now 237.9/100 000, i.e., 11.9 times more than the original cohort (asymptomatic patients from the Metropolitan region). For FIT– patients, the incidence is now 5.631/100 000, i.e., 3.55 times less than before. Using these new values for incidence for each sub-cohort, we can now compute the results of

Table 1.

Out of the mathematically 6 013.13 FIT+ patients and using the same values for specificity and sensitivity (but with an updated incidence of 237.9/100 000) it follows that there will statistically be 370.37 people who will test positive twice (FIT++), out of which 10.44 will be Real Positives and 359.93 False Positives. It also follows that there will be 5 642.76 positive then negative people (FIT+–) out of which 5 638.89 will be True Negatives and 3.86 will be False Negatives and so on for FIT+– and FIT–– people.

The interesting thing to see is that we now have 3 subgroups: 370.27 FIT++ people for which the CRC incidence is now 2820/100 000, 5 642.76+5 642.76 FIT+– or FIT–+ people for whom the incidence is 68.4/100 000 and 88 344.11 FIT–– people for whom the incidence is 1.62/100 000. The probability for a FIT++ person to have CRC is still low (2.82%) but it is already increasing.

Our proposition is to repeat this more times, until results are really significant as we reach the “middle part” of the sigmoid.

Table 2 shows the theoretical results of performing 4 consecutive FIT tests on 100 000 inhabitants of the Metropolitan region.

Looking at

Table 2, we see that 6.86+89.43 = 96.29 of the 100 000 people urgently need a colonoscopy: the 6.86 FIT

++++ because they have >81% chance of having CRC and the 89.43 FIT

+++– because they have a still life-threatening 9.2% chance of having CRC.

Performing 96 colonoscopies rapidly is a reduction of 99.9% over a colonoscopy screening of 100 000 people, that would take years without the proper infrastructure and cost millions.

Then, 1 913 FIT++–– persons have 0.24% chance to have CRC, which is 12.25x more than the original observed incidence of 0.0196%. But here again, 1 913 additional colonoscopies could be performed much easier than 100 000. An alternative could be to offer these at-risk people more FIT tests (still cheaper and easier to do than a colonoscopy) to discern who needs a colonoscopy and who does not.

19 931.24 FIT+––– people have a 0.005652% chance to have CRC, which is 3.47 times less than the original asymptomatic population of the Metropolitan region (which is currently not screened in Chile). They could be tested again in following years.

Finally, 78 059.7 FIT–––– people have virtually 0% chance of having CRC. It may not be necessary to test them in the near future. We show in section 3.1 that even on a symptomatic cohort, many more FIT tests would be needed to bring other significant results, so it seems that 4 tests is an optimum value for Faecal Immunochemical Tests.

As a conclusion, a CBI CRC screening with 4 FIT without-waiting-list tests:

would single out only 96 high-risk people out of 100 000 to whom a colonoscopy could be prescribed,

could reasonably allow to avoid performing 78 058 colonoscopies and possibly 19 931 more, resulting in replacing 98.99% of colonoscopies with 4xFIT tests.

3.1.1. Cost Evaluation

If we take a cost of

$5 USD for a FIT test and

$500 USD for a colonoscopy [

3], screening the whole 100 000 cohort would cost

$50m USD and would be very difficult, if not impossible to perform rapidly without adequate infrastructure and personnel.

Performing a 4-FIT CBI screening protocol + necessary urgent colonoscopies would cost 100 000x4x5 + 71x500 = $2 035 500 USD, i.e., 24.5 times less than a full-colonoscopy screening as proposed in Germany, with virtually no colonoscopy waiting list after the FIT tests are returned. The 71 high-risk patients would be identified and their treatment started immediately. If judged necessary, performing a colonoscopy on the other 1 913 FIT++–– people would cost an additional $956 500 USD, i.e., around $1m more and this could be performed in several months in the public hospitals of the Metropolitan region.

3.2. Result of the Application of 4 Consecutive FIT Compound Bayesian Inference (4-FIT CBI) on a Symptomatic Cohort

A recent study on 1,315 Chilean symptomatic patients [

25] observed the predictive quality of a single FIT test for colorectal cancer. Out of the initial cohort, a certain number of patients were removed from the FIT study: those who previously had a CRC diagnosis and those who were given priority for a colonoscopy due to their symptom-based classification as High Risk (HR) patients. 808 Low-to Moderate risk (L/MR) patients were prescribed a FIT test (and returned it) before the validation colonoscopy.

Table 3 (replicate of

Table 2 of the study) gives us all the necessary data to infer the results that can be obtained by a 4-FIT Compound Bayesian Inference method.

The three pieces of prior information needed for Bayesian Inference (incidence, test specificity and sensitivity) can be computed from

Table 3. Out of the 808 Low to Moderate Risk (L/MR) symptomatic patients, 27 were diagnosed (with colonoscopy) with CRC:

Sickness (CRC) incidence for this L/MR cohort was 3.34% (27 out of 808), i.e., 170 times higher than for the asymptomatic cohort.

Out of the 808 – 27 = 781 non-CRC patients, 256 were FP, corresponding to a specificity of 67,22%.

Out of the 27 CRC patients, 1 was FN, corresponding to a sensitivity of 96.3%.

FP and FN values are very different from those published in the literature for FIT tests because generally, studies are performed on asymptomatic patients for screening purposes. However, as stated in [

25], CRC symptoms are nonspecific: rectal bleeding can come from haemorrhoids or ulcerative colitis, or other factors that may not be cancerous tumors. So, if occult blood in stool is what is tracked for CRC detection, more false positives will be found in ``symptomatic patients” than in an asymptomatic population. We now see that the specificity of the test does not only depend on the test itself as it also depends on the cohort. However, sensitivity will not be affected. This is important if the objective is to detect who does not have CRC.

Using these values, we can infer the results of more FIT tests on this specific cohort (cf.

Table 4.).

We see that the probability of being sick if tested positive (FIT+) is 9.21%, which is 2.76 times higher than in the original cohort. The probability of being sick if tested negative (FIT–), is now 0.19%, so the sub-cohort incidence has been divided by 17.58. Unfortunately, 0.19% chance of having CRC is still much too important, because every 1000 patients, 2 patients will unknowingly have CRC.

As for the simple example, our proposition is to now consider two sub-cohorts: one cohort of 308 FIT+ patients and a second cohort of 500 FIT– patients and repeat FIT tests (rather than performing costly and resource-intensive colonoscopies, noting that every time a FIT test is done on a sub-cohort, the incidence rates will compound.

3.2.1. Results of 4 FIT Tests on the Low-Moderate Risk Cohort of [25]

We now present both an aggregated table for the 4-FIT Compound Bayesian Inference in

Table 5 and

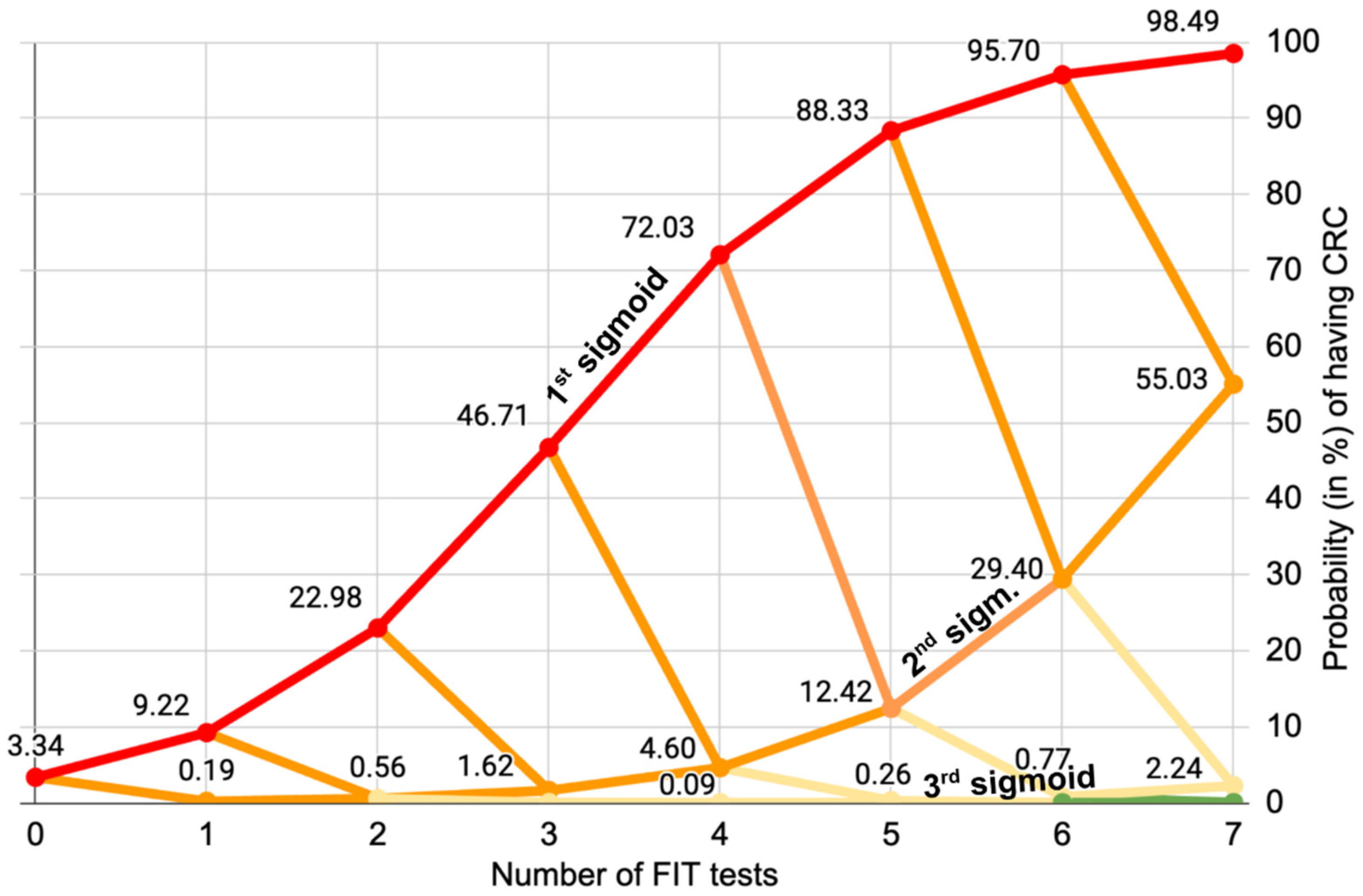

Figure 1, which represents the sigmoid evolution of the probability for patients to have CRC over multiple consecutive tests:

The 32 FIT

++++ patients must clearly be prioritized for a colonoscopy, as they have 72% chance of having CRC: they are on the 1st sigmoid of

Figure 1. The 4xFIT CBI screening shows its efficiency here, because they would be immediately prioritized (this is already what the team of [

25] has done on their High-Risk priority patients, who benefited immediately from a colonoscopy).

The 77 FIT

+++– patients who have a 4.6% chance of having CRC should also be prescribed a colonoscopy because they are on the 2nd orange sigmoid of

Figure 1. Altogether the cumulated number of FIT

++++ and FIT

+++– patients of the Low-Moderate Risk cohort is only 109.

One could think that the 228 FIT

++–– patients are more problematic because they have a 0.09% chance of having CRC, which is 4.6 times more than the incidence of CRC in the asymptomatic population of the Metropolitan region, to which they belong. However,

Figure 1. shows us that even if they were positive to a 5th FIT test, it would not be conclusive. The 3rd (pale yellow) sigmoid evolves really slowy. The decision of whether or not to lower their priority in accessing colonoscopy could lie with the hospital ethics committee.

Figure 1. clearly shows that performing a fifth or sixth test would not yield any additional significant information, showing a limit of the multiple FIT tests for this cohort. This is why we posit that for this cohort, four FIT tests represent the optimal balance between significance and number of tests.

The 470 FIT+––– and FIT–––– patients have a really low probability of having CRC (less than 0.002%, i.e., 10 times less than the incidence of CRC in the asymptomatic people of the Metropolitan region to which they belong). Their acces to a colonoscopy could probably have been safely lowered, in spite of their initial belonging to the Low to Moderate Risk cohort, therefore giving the opportunity to other higher-risk patients to get access to a colonoscopy sooner.

To summarise, we posit that 4 FIT tests would indicate whether previous patients from the same hospital were on the first two “dangerous sigmoids”. If priority to a colonoscopy was given to patients on the 1st and 2nd sigmoid (FIT++++ and FIT+++–) their number would be 109, which means that their waiting list could be reduced by 86.5%.

3.2.2. Potential Results of 4 FIT CBI on the High Risk Patients Cohort [25]

[

25] also gives us the incidence of CRC on the High-Risk cohort: it is composed of 345 patients of which 16 were diagnosed with CRC thanks to a high-priority colonoscopy. Because they are patients of the same hospital, we could assume they come from a similar population but more importantly, they would be tested the same way as the L/MR cohort. The specificity of FIT on this High-Risk cohort would be lower than in the Low to Moderate Risk cohort, but remember that what we are interested in is the sensitivity of the test, that has no known reason to vary.

Table 6 shows the aggregated results for the High Risk cohort.

We see that had a 4-FIT CBI protocol been used on this cohort, 51 patients could have been prioritised but more importantly: 96+131+67 = 294 out of 345 patients could have been given a lower colonoscopy priority, reducing the waiting list by 85.2% for the FIT++++ and FIT+++– patients.

More importantly, these 345 patients had a much lower probability to have CRC (<= 0.127%) than the FIT++++ and FIT+++– of the L/MR cohort, but due to their “High-Risk” symptoms, they were given direct access to a colonoscopy, even though we showed that there were patients of the L/MR cohort who had a much higher probability to have CRC. Using a 4-FIT CBI test on the whole HR and L/MR cohort could really have improved the 5 year survival chance of the 110 “Low to Moderate Risk patients” who were on the 1st and 2nd sigmoid and did not have fast access to colonoscopy, of whom 10 died between the date of the study (2019) and the date of the submission of the paper to The Lancet (before March 2025).

3.3. Mathematical Analysis of the Performance of Multiple FIT Compound Bayesian Inference Tests on the L/MR Cohort of [25]

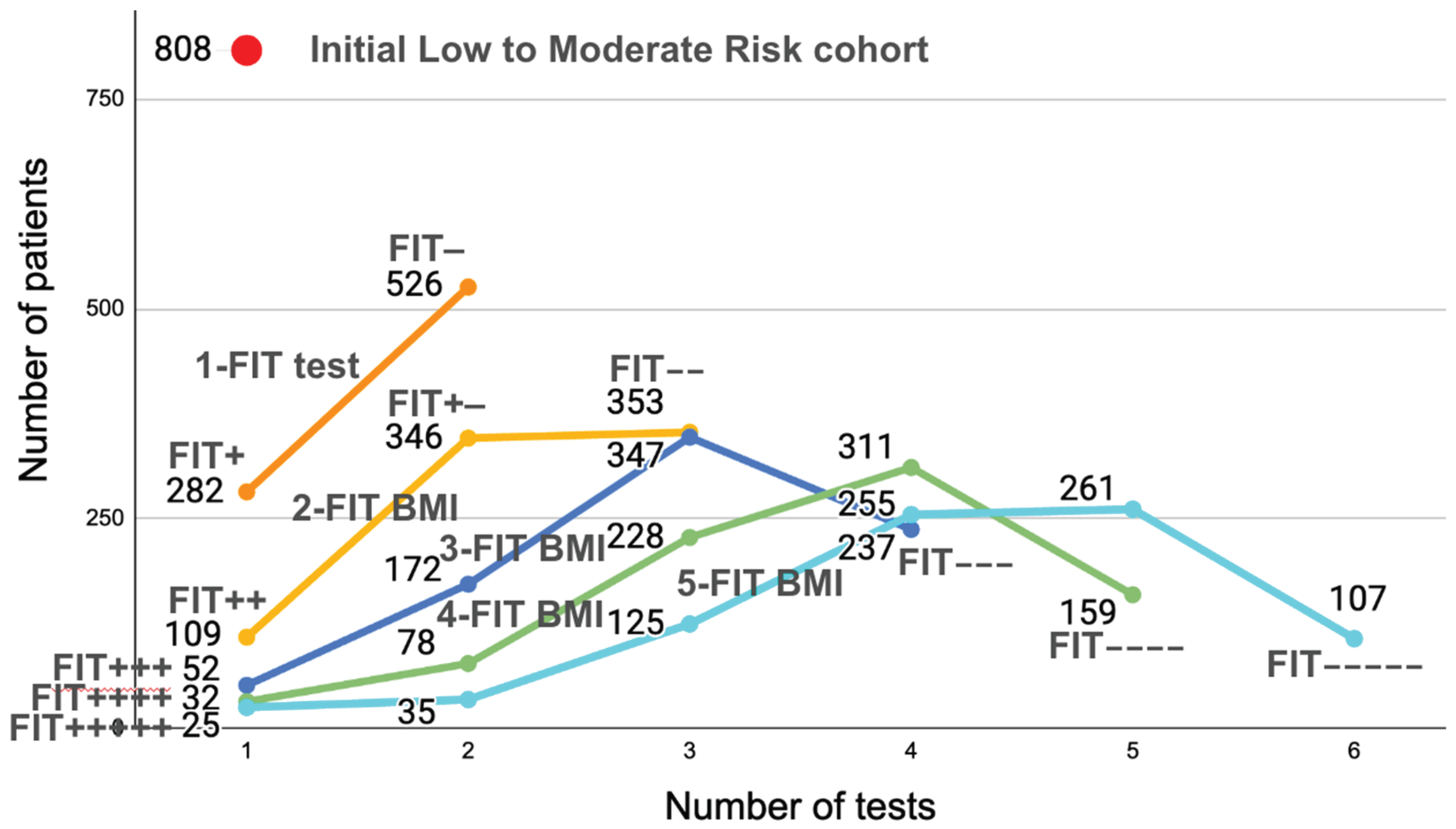

Figure 2 is very interesting because it shows the evolution of the number of positive or negative patients for 1 to 5 FIT CBI tests on [

25]’s L/MR cohort.

After 1 FIT test is performed (top dark orange curve), 2 categories appear: 282 patients will be positive and 526 negative. However, we know that only 27 of the 808 have been diagnosed for CRC. So the 282 positives reflects the imprecision of a single test (too low specificity). As the number of tests increases (2-FIT CBI, 3-FIT CBI, etc.), we see that there are fewer and fewer continuously positive patients: 109 FIT++ (in a 2-FIT test), 52 FIT+++ (in a 3-FIT test) etc., until, for 5-FIT tests, we see that there are only 25 FIT+++++, when we know that there were 27 diagnosed patients. We see here the imprecision linked to imperfect sensitivity: 2 of the 27 diagnosed patients had at least one negative FITs, which is where the problem lies: the more tests will be performed, the more chance some tests will be False Negatives, showing (mathematically) that increasing the number of FIT tests in hope that they would precisely detect the number of sick patients is illusory. Because there are False Negatives (due to intermittent bleeding), there will always be patients with CRC who will have negative FITs.

The graph of

Figure 2 shows in a different way why 4 consecutive tests seems to be the optimal number for FIT tests: performing fewer than 3 tests leads to too many colonoscopies. Performing more than 4 tests does not provide sufficient additional information for reducing significatively the number of needed colonoscopies.

4. Discussion

The use of Bayesian inference for making predictions is certainly not a novel technique, as it has been described as early as 1763 [

19] and 1771 [

26]. However, we have not found any references to the method we propose of creating sub-cohorts with improved compound incidence to enhance the predictive value of data collected from previous clinical trials, including in books specialised in Bayesian statistics such as [

27,

28]. As stated in [

16], colon polyps in the early stages of development bleed intermittently, which is why a single negative FIT test is not conclusive enough to remove a patient from a waiting list. This intermittent bleeding makes two consecutive FIT tests independent of each other, enabling us to combine the results of successive tests to improve their predictive power.

We mathematically show that 4xFIT CBI tests can tell if a patient is on the first of second sigmoid of

Figure 1, or on a much less risky third sigmoid. Although articles have been published on predicting CRC using a Bayesian methodology [

29,

30], we could not find any papers showing a similar approach, or proposing to use independent FIT tests with Bayesian inference to prioritise patients or reduce the number of patients on the colonoscopy waiting list, which is the focus of this paper.

If our method had been applied on the totality of the High-Risk and Low/Moderate Risk cohorts of [

25], the 33 patients with 72% probability of CRC of the L/MR cohort would have had access to a colonoscopy before the 326 patients of the HR cohort who had 6.35% (or less) probability to have CRC. 10 of the L/MR cohort died between the clinical study and the preprint publication of [

25]. Having had a colonoscopy earlier may have improved their survival chances.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this research is to show that using 4 very cheap (and immediately accessible) FIT tests could determine the probability of a patient to have CRC. It is important to understand that the proposed CBI approach is descriptive, i.e., the only information it can provide to the doctors is the following:

In this hospital (or region, or country), it is observed from previous data that people with 4 positive FIT tests had an xx% of having CRC.

A new person is being tested for CRC. If this person is FIT++++, it is observed that in the past, in this hospital (or region or country) FIT+++++ people had yy% chance of having CRC.

We think that this information could help a doctor (with the validation of an ethics committee) prioritize the access of people (or patients) to colonoscopies when they cannot be performed immediately to all.

Many countries cannot afford to offer free colonoscopies to all their population over 50 or 55, like what Germany is offering, but as shown in other papers, 1-FIT test screening (as proposed in other countries such as France) is insufficient. The 4-FIT CBI approach that we propose is mathematically sound and could provide health institutions with valuable information to rapidly detect and prioritize patients in need for a colonoscopy by reducing their number by over 98.9% for screening of asymptomatic patients, and over 85% on the symptomatic cohort of [

25] who, in Chilean public hospitals can face a >1 year waiting list for colonoscopies, during which cancers will develop.

We hope that the purely mathematical analysis in this paper will convince hospitals to conduct real-world clinical trials to validate the approach experimentally. If verified, this screening method based on mathematical Bayesian Inference could save lives (and millions of dollars to all world health systems (including Germany) if enough validation data could show that some colonoscopies are unnecessary.

Then, Compound Bayesian Inference could also be used to integrate other markers [

31] or for screening other types of cancers or sicknesses if cheaper / less invasive / less resource-intensive tests (such as blood tests with lower specificity and sensitivity) are available [

32] as this new multi-purpose Bayesian-based statistical method for establishing the incidence in subcohorts that we are proposing here were used, because it can exploit the combined descriptive power of several independent tests.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. A spreadsheet file is provided for reviewers to replicate the different tables and curves presented in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: PC, CT, FQ; Funding Acquisition: CT; Methodology: PC, CT, FQ; Prepared figures : PC, CT, FQ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: PC; Writing – Review & Editing: CT, FQ

Funding

This research was funded by the ANID FONDAP 152220002 (CECAN).

References

- Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A. and et al., “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries,” CA Cancer J Clin., pp. 71(3):209–249, 2021. [PubMed]

- WHO facts sheet on colorectal cancer https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/colorectal-cancer.

- Zauber AG. Cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010 Oct;20(4):751-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- R Haslam, S El-Khassawneh, The cost of colonoscopy – a worldwide view, Gut 62(Suppl 2): A16.1-A16. 2013. ISSN/ISBN: 0017-5749. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Molina R, Suárez M, Martínez R, Chilet M, Bauça JM, Mateo J. Utility of Stool-Based Tests for Colorectal Cancer Detection: A Comprehensive Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(16):1645. [CrossRef]

- Coury, J., Ramsey, K., Gunn, R. et al. Source matters: a survey of cost variation for fecal immunochemical tests in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 204 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Daly JM, Xu Y, Levy BT. Which Fecal Immunochemical Test Should I Choose? J Prim Care Community Health. 2017 Oct;8(4):264-277. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Niedermaier T, Tikk K, Giess A, Bieck S, Brenner H, Sensitivity of Fecal Immunochemical Test for Colorectal Cancer Detection Differs According to Stage and Location, Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Volume 18, Issue 13, 2920 - 2928.e6 https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(20)30104-X/fulltext#app-1.

- Niedermaier T, Balavarca Y, Brenner H. Stage-Specific Sensitivity of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Detecting Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Jan;115(1):56-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Imperiale TF, Gruber RN, Stump TE, Emmett TW, Monahan PO. Performance Characteristics of Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Colorectal Cancer and Advanced Adenomatous Polyps: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Mar 5;170(5):319-329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza N, Brzezicki A, Abulafi M. Faecal immunochemical testing in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Feb;69(679):60-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, et al. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:171–81.

- Pellat A, Deyra J, Husson M, Benamouzig R, Coriat R, Chaussade S. Colorectal cancer screening programme: is the French faecal immunological test (FIT) threshold optimal? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021 May 7;14:17562848211009716. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosenfield R., E., Kochwa S., Kaczera Z. et al.: Non-uniform distribution of occult blood feces. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1978: 71:204-9.

- J Doran, J D Hardcastle, Bleeding patterns in colorectal cancer: The effect of aspirin and the implications for faecal occult blood testing, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 69, Issue 12, December 1982, Pages 711–713. [CrossRef]

- Nakama H, Kamijo N, Fujimori K, Horiuchi A, A S M Abdul Fattah, Zhang B, Characteristics of Colorectal Cancer with False Negative Result on Immunochemical Faecal Occult Blood Test, Journal of Medical Screening 1996;3: 115-1, Medical Screening Society. [CrossRef]

- Santiago L, Toro DH. Effectiveness of Multiple Consecutive Fecal Immunohistochemical Testing for Colorectal Cancer Screening. P R Health Sci J. 2022 Sep;41(3):117-122. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mondschein S, Subiabre F, Yankovic N, Estay C, Von Mühlenbrock C, Berger Z. Colorectal cancer trends in Chile: A Latin-American country with marked socioeconomic inequities. PLoS One. 2022 Nov 10;17(11):e0271929. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- T. Bayes, An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 53:370-418, 1763.

- A. I. Dale, A History of Inverse Probability: From Thomas Bayes to Karl Pearson, Springer, 1999.

- Nicholas G. Farkas, Lampros Palyvos, James W. O’Brien, Kai Shing Yu, Carolyn Pigott, Martin Whyte, Iain Jourdan, Timothy Rockall, Callum G. Fraser, Sally C. Benton, The repeat FIT (RFIT) study: Does repeating faecal immunochemical tests provide reassurance and improve colorectal cancer detection?, Colorectal Disease Volume26, Issue 9, September 2024, Pages 1711-1719. [CrossRef]

- Dong Wu, Han-Qing Luo, Wei-Xun Zhou, Jia-Ming Qian, Jing-Nan Li, The Performance of Three-Sample Qualitative Immunochemical Fecal Test to Detect Colorectal Adenoma and Cancer in Gastrointestinal Outpatients: An Observational Study, PLoS ONE 9(9): e106648 2014. [CrossRef]

- Heisser T, Hoffmeister M, Tillmann H, Brennera H, Impact of demographic changes and screening colonoscopy on long-term projection of incident colorectal cancer cases in Germany: A modelling study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe, Volume 20, 100451, September 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Michaus, E. Ruiz-Garcia, Colorectal Cancer in Latin America: Quick comment, Oncodaily Medical Journal, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Díaz, Felipe and Acevedo, Johanna and González, Maite and Tello, Andrea and Castillo, Richard and Morales Mora, Carlos and Manríquez Alegría, Erik and Durán Espinoza, Valentina and Le-Bert, Catherine and Cabreras, Manuel and Fulle, Angello and Carvajal, Gonzalo and Briones, Pamela and Nervi Nattero, Bruno and Kusanovich, Rodrigo, Assessing the Impact of a Single Qualitative Fecal Immunochemical Test on Colonoscopy Prioritization and Mortality in Risk-Stratified Patients with Suspected Colorectal Cancer. Preprints with The Lancet Regional Americas, March 2025, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5188039. [CrossRef]

- Pierre-Simon de Laplace, Mémoire sur la probabilité des causes par les événements, Mémoire de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, Tome VI p621, 1774, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k77596b/f32.item.

- Jim Albert and Jingchen Hu, Probability and Bayesian Modeling, 552p, Chapman & Hall, 2019, ISBN 9781138492561.

- Broemeling, L.D. (2015). Bayesian Methods for Repeated Measures (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., Lau, M.C., Haruki, K. et al. Bayesian risk prediction model for colorectal cancer mortality through integration of clinicopathologic and genomic data. npj Precis. Onc. 7, 57 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, A., Musheer Aziz, R. & verma, N.K. Applications and Techniques of Machine Learning in Cancer Classification: A Systematic Review. Hum-Cent Intell Syst 3, 588–615 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Daniel C. Chung, Darrell M. Gray II, Harminder Singh, Rachel B. Issaka, Victoria M. Raymond, Craig Eagle, Sylvia Hu and William M. Grady, A Cell-free DNA Blood-Based Test for Colorectal Cancer Screening, N Engl J Med 2024; 390:973-983, VOL. 390 NO. 11. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Xiao J, Yang Y, Chen G, Hu D, Zeng J. Strategies for five tumour markers in the screening and diagnosis of female breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2023 Jan 23;12:1055855. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).