Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) complicate 6% to 8% of all pregnancies [

1]. HDP are among the major contributors to adverse maternal health outcomes in the United States [

2]. HDP varies in severity and includes preeclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia, and gestational hypertension, as defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) [

3]. Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes and Low Platelets (HELLP) Syndrome is considered to be a severe complication of HDP [

4], though there may be some variability in risk factors between HDP and HELLP Syndrome [

4]. These conditions can have significant short- and long-term complications for both maternal and child health.

Short-term maternal complications include heart failure, hemorrhage from placental abruption, stroke, renal dysfunction, and pulmonary edema [

5,

6]. Long-term postpartum complications include increased risk of cardiovascular events, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes [

7,

8]. Fetal and neonatal complications include fetal growth restriction and preterm birth, while

long-term effects include poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes, and higher risk for metabolic disorder and cardiovascular disease in adulthood [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Preeclampsia (PE) is characterized by new onset hypertension (≥140 systolic or ≥90 diastolic/mmHg) and proteinuria (>300mg/24h) or other signs of organ dysfunction (e.g., elevated liver enzymes) occurring after 20 weeks of pregnancy [

13].

While the public health significance of PE is well recognized, the molecular pathogenesis has yet to be completely understood. PE is known to be associated with changes in expression of placental genes, however, the specific patterns of risk related gene expression in PE are incompletely elucidated, highlighting the need for further research into the underlying molecular mechanisms. [

15] Serine protease inhibitors (SERPINs) such as SERPINA3, A5, A8, B2, B5, andB7 are among the placentally expressed genes associated with PE [

16]. Among the SERPINs, SERPINA3 has drawn particular attention due to its potential role in placental dysfunction.

SERPINA3, also called α-1-antichymotrypsin, is involved in a wide range of biological processes including inflammation. Maternal tolerance of the semi-allogenic fetus is tightly regulated in pregnancy. SERPINA3 helps regulate the maternal inflammatory response by binding to serine proteases and undergoing a conformational change that prevents proteolytic activity [

17,

18]. As reviewed by Chelbi et al., SERPINA3 is up-regulated in human placental diseases in association with a hypomethylation of the 5′ region of the gene [

19]. A study by Auer et al. found that protein levels of SERPINA3 are higher in serum of pregnant women affected by PE and fetal growth restriction. [

14].

In addition to placental diseases, SERPINA3 has been found to be associated with various human diseases, such asAlzheimer’s disease [

20], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [

21], and multiple forms of cancer including glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma [

22].

Our study adds to the current knowledge of SERPINA3 in several ways. First, few studies have explored SERPINA3 polymorphisms in relation to PE risk, especially for the Hispanic population. Second, we explored mother-child dyads and mother-father-child triads to provide a more comprehensive understanding of genetic contributions to PE risk, including PoO effects. Lastly, the existing studies on SERPINA3 polymorphisms related to pregnancy complications are limited, our study helps to add and expand the current knowledge in SERPINA3’s role in HDP.

The main objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between two SERPINA3 alleles and HDP/sPE/HELLP syndrome.

Methods

Subjects

HDP: This retrospective case-control study included mother-baby dyads, of which 142 were diagnosed with HDP and 168 had normotensive pregnancies. Participants were recruited from a large, urban, safety-net hospital in Los Angeles. Participants were identified via delivery logs between 1999-2006 (n=105, 33.8%) and during their postpartum hospital stay from 2007-2008 (n=206, 66.2%). Cases were women diagnosed with eclampsia, PE (including superimposed PE), gestational hypertension, or HELLP syndrome, and were verified through chart review. Controls were women from the same population and time period with no clinical diagnosis of HDP during pregnancy.

Severe PE/HELLP: This retrospective internet-based cohort includes mother-father-baby triads (n= 217). Participants were recruited through two HELLP syndrome-centered websites (

www.hellpsyndromesociety.org or https://

www.facebook.com/pages/Hellp-Syndrome-Research-at-USC/163745723652843). The case cohort (n= 189) consisted of women with self-identified HELLP syndrome, with verification through medical record review for 66.1% of cases. Some participants in the case cohort recruited friends who gave birth within five years of the affected pregnancy and reported no HDP history during pregnancy for the control cohort (n=28 triads).

Case Definition

HDP: PE cases were identified if the participants had a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg on two measurements taken at least 6 hours apart, accompanied by proteinuria, as defined by dipstick reading of ≥1 or a total of ≥300 mg/dL within a 24-hour urine sample. Participants with high blood pressure without proteinuria were classified as gestational hypertension. As there was no significant difference observed between these groups, they were combined as a group for analysis.

Severe PE/HELLP: Self-reported HELLP cases were confirmed based on the following criteria: (1) Hemolysis as indicated by either abnormal red blood cells on a peripheral blood smear or an LDH level of ≥600 IU/L, (2) Liver enzymes elevation, defined as AST or ALT ≥ 70 U/ L, (3) Platelet count < 100,000/µL, regardless of the presence of proteinuria or hypertension. Participants meeting at least two of these three criteria were categorized as severe PE, as all exhibited hypertension (BP ≥ 160/110 mmHg on two separate readings taken at least 6 hours apart) and proteinuria (≥500 mg/dL in a 24-hour urine sample or a +3 dipstick reading on two occasions at least 6 hours apart).

Questionnaire

A standardized risk questionnaire in English or Spanish was used for data collection. Information on personal and family medical history, reproductive and sexual history, obstetric history, and other risk factors were collected.

Chart Abstraction

For the HDP population, medical records were obtained from the delivery hospital for both cases and controls. For the severe PE/HELLP population, medical records were requested from the treating obstetrician and delivery hospital. Medical records were reviewed by one of the investigators (MLW) to verify diagnoses. Data abstraction was conducted using a standardized data abstraction form, which included information about obstetric history, prenatal visits, delivery, and coexisting medical conditions.

Polymorphisms Selection

Two SNPs within the SERPINA3 gene were selected for analysis to represent the majority of genetic variation within the gene: rs4934 and rs1884082. SNPs were selected if at least one of the following criteria was met: (1) recognized as a functional polymorphism in published studies, (2) related to health outcomes in peer-reviewed literature, (3) located in a coding region and causing a non-synonymous amino acid change, or (4) found in a regulatory or upstream region. Information about the selected SNPs are shown in

Table 1a,

Table 1b, and

Table 1c. We repeated genotyping for 5% of all samples as a validation measure and found no discrepancies.

Sample Collection

DNA samples were collected using buccal swabs (87%) or mouthwash (13%) for both mothers and infants in the HDP cohort. DNA samples of the severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohort were obtained via Oragene saliva kits (DNA Genotek, Ottawa, Canada) (89%) or buccal swabs (11%). All mouthwash and saliva samples were extracted using ethanol precipitation . Buccal swabs were extracted using QIAmp DNA mini kits following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genotyping failure rates were not affected by the DNA sample collection method.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the mother-baby dyads in the HDP cohort and mother-father-baby triads in PE/HELLP syndrome cohort was performed by using the

Haplin package (Version 7.3.2) for R programming language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [

25]. Haplin is a software tool designed for genetic association analysis of case-parent triad data with multiple markers. It incorporates both complete and incomplete control triads and estimates relative risks (RR), confidence intervals, and p-values associated with each variant/haplotype. Haplin also evaluates parent-of-origin (PoO) effects, and uses maximum likelihood estimation to utilize data from dyads and triads with missing genotypic data [

27]. It is statistically expressed as RRR = RR

M,j / RR

F,j, which is a measure of the relative risk of an allele A

j inherited from the mother as opposed to father [

27]. Post-hoc power calculations and free response models were also performed by Haplin [

33]. All analyses were performed in R programming software (Version 4.4.2).

The analysis for continuous variables from the maternal demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in means ± standard deviations or median with interquartile range, while categorical variables are presented in counts and percentages. Demographic and clinical characteristics are described for both cohorts stratified by disease status.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for parent-of-origin effects, single- and double-dose effects, and haplotypes were evaluated using a two-sided significance level of α = 0.05.

We calculated the effect size we can detect with 142 case dyads and 168 control dyads as well as with 189 case triads and 28 control triads. Assuming a minor allele frequency of 10% and a Type I error rate of 5%, we detected an OR of 1.5 for both lowest minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.27 and highest MAF of 0.48 for the HDP cohort, and ORs of 1.7 and 1.6 at the same respective MAFs for the severe PE/HELLP cohort.

Results

Participants

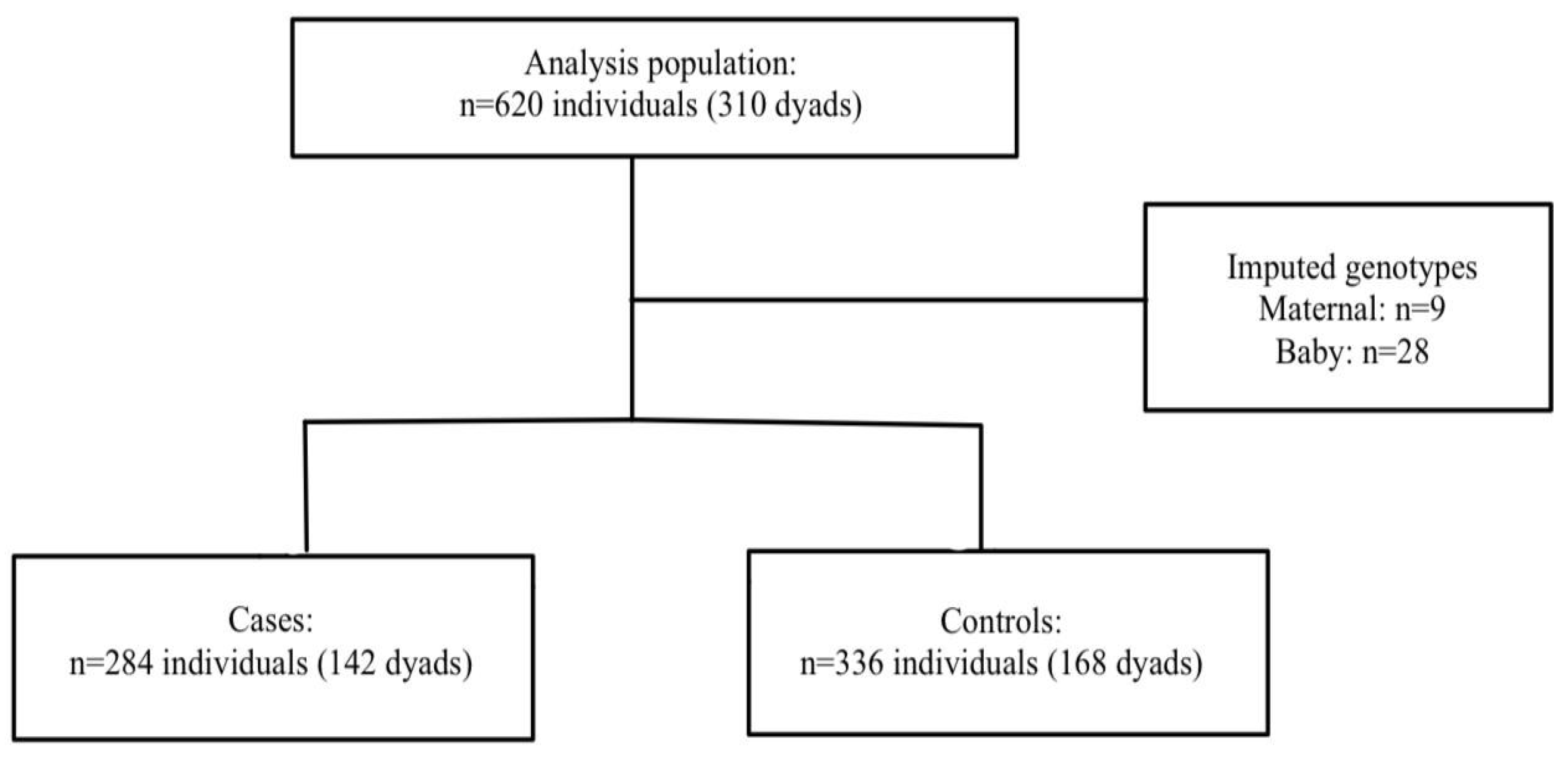

HDP: A total of 620 mothers and babies (n=310 dyads) were included in the final analysis. Nine mothers and 28 babies were missing at least one of the genotype data points. Haplin’s EM algorithm, implemented as part of the analysis, was used to impute the missing genotypes. Among the 142 cases, 68.3% were diagnosed as PE, 2.1% were superimposed PE, and 29.6% were gestational hypertension. The participant flow chart is shown in

Figure 1.

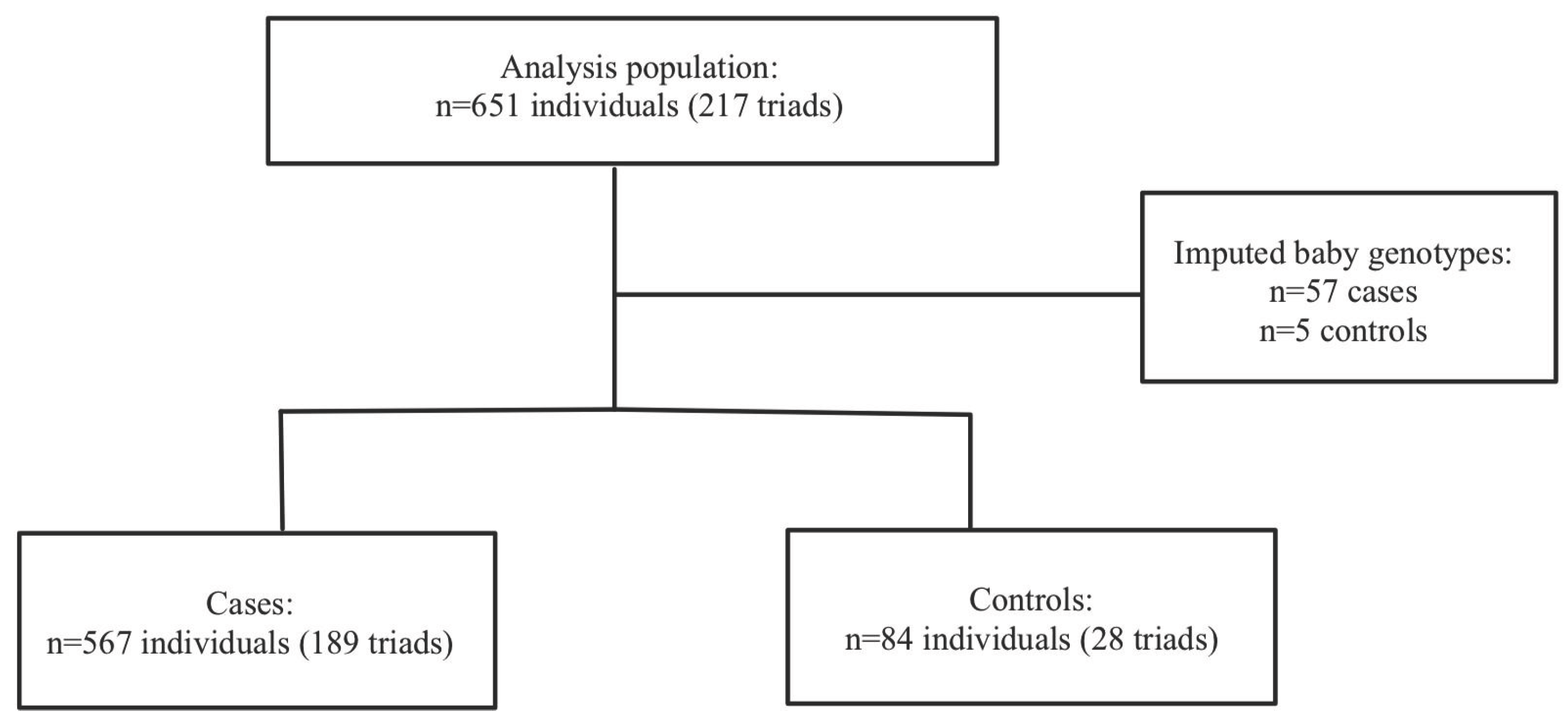

Severe PE/HELLP: A total of 217 mother-father-baby triads, 189 cases triads and 29 control triads, were included in the analysis. Haplin’s EM algorithm imputed the missing genotypes for 57 cases (10.1%) and 5 controls (5.7%). Within the sPE/HELLP cohort, 59.2% of the cases in the severe PE/HELLP syndrome population were classified as severe PE and 40.8% were classified as HELLP syndrome. The participants flow chart is shown in

Figure 2.

Maternal Demographics

HDP:

Table 2 shows the maternal demographics and clinical characteristics divided into HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohorts with corresponding case-control status. The HDP cohort included primarily women of Hispanic ancestry (95.8% for cases, 96.4% for controls).

The cases exhibited lower gestational ages at birth (cases: 36.8 ± 3.4 and controls: 38.7 ± 2) and lower average birth weights (cases: 3060.0g and controls: 3288.0g) compared to controls.

Nulliparity rate was higher among the cases (43% for cases, 30.7% for controls).

Severe PE/HELLP: All the participants in the severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohort were White. Cases exhibited lower gestational ages compared to controls (cases: 33.7 ± 3.8 and controls: 39.6 ± 1.8). In addition, the case cohort had a lower average birth weight than the control cohort (cases: 2540.1g, controls: 3242.3g).

Table 2 shows the maternal demographics and clinical characteristics divided into HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohorts with corresponding case-control status.

Individual SNP Analysis

HDP: There were no statistically significant associations between SERPINA SNPs and HDP for either mother or child observed in the study cohort (

Table 3a).

Severe PE/HELLP: No statistically significant associations between maternal and child SERPINA3 polymorphisms and severe PE/HELLP syndrome was observed in this study cohort (

Table 3b). Associations between paternal and child were assessed through imprinting status.

Combined: A combined analysis was performed due to the similarity of RR ratios in both the HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohort. The combined data of 527 triads were included in the analysis. For rs1884082, 5 triads were excluded from the original 527 triads due to Mendelian inconsistencies. For rs4934, 4 triads were removed due to Mendelian inconsistencies and 2 triads were removed due to low frequencies. No statistically significant associations were observed among the combined cohort (

Table 3c).

Haplotype Analysis

HDP: 16 of the 310 dyads were excluded due to low frequency haplotypes, leaving 294 dyads for analysis. No statistically significant associations with risk of HDP were found in either mother or child haplotypes (

Table 4a).

Severe PE/HELLP: 29 triads of the 217 triads were excluded from the analysis due to Mendelian inconsistencies (n=7) and low frequency haplotypes (n=22). The remaining 188 case-control triads did not show any statistically significant relationship between maternal and child SERPINA3 haplotypes and risk of severe PE/HELLP syndrome (

Table 4b). A suggestion of possible association was observed for the g-a haplotype (relative to T-G haplotype), suggestive of a possible protective effect when maternally carried (Single dose: RR=0.69, 95% CI: (0.46, 1.05), p=0.08).

Combined: 45 dyads or triads were removed from the analysis due to Mendelian inconsistencies (n=7) and low frequency haplotypes (n=38). No statistically significant associations were observed between the g-a haplotype (relative to T-G haplotype) and HDP in the combined cohort for maternal allele, but were borderline significant for child allele (Double dose: RR=1.58, 95% CI: (1.00, 2.52), p=0.05) (

Table 4c).

Parent-of-Origin Analysis

No PoO effects were observed in either HDP and sPE/HELLP cohorts. However, in the combined cohort, we found statistically significant PoO effects. First, we observed an increased risk of HDP if the mother carries a double copy for both rs4934 (RR=3.03, 95% CI (1.50, 6.09), p<0.01) and rs1884082 (RR=2.38, 95% CI (1.22, 4.71), p=0.01). We also observed a decreased risk of HDP for rs4934 (RR=0.54, 95% CI (0.31, 0.98), p= 0.04) and rs1884082 (RR= 0.52, 95% CI (0.30, 0.91), p= 0.02) associated with child carriage of the maternal copy. Conversely, child carriage of the paternal copy of rs4934 is associated with an increased risk of HDP (RR= 1.54, 95% CI (1.09, 2.20), p= 0.02).

Table 5.

Combined parent-of-origin analysis of associations between maternal and child SERPINA3 haplotypes and risk of HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome.

Table 5.

Combined parent-of-origin analysis of associations between maternal and child SERPINA3 haplotypes and risk of HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome.

| SNP |

Allele |

Allele frequenc y (%) |

Maternal |

Child |

| Single dose RR (95% CI) |

P |

Double dose RR (95% CI) |

P |

Single- mat dose RR (95% CI) |

P |

Single- pat dose RR (95% CI) |

P |

Double dose RR (95% CI) |

P |

Ratio m-p (95% CI) |

P |

| rs4934 |

A |

30.4 |

1.19

(0.83,

1.72) |

0.35 |

3.03

(1.50,

6.09) |

<0.01 |

0.54

(0.31,

0.98) |

0.04 |

1.54

(1.09,

2.20) |

0.02 |

1.13

(0.69,

1.88) |

0.63 |

0.35

(0.18,

0.71) |

<0.01 |

| rs1884082 |

G |

36.4 |

1.21

(0.85,

1.72) |

0.29 |

2.38

(1.22,

4.71) |

0.01 |

0.52

(0.30,

0.91) |

0.02 |

1.38

(0.98,

1.94) |

0.07 |

1.09

(0.68,

1.75) |

0.72 |

0.38

(0.19,

0.74) |

<0.01 |

Discussion

This study analyzed maternal and child polymorphisms and haplotypes in the SERPINA3 gene for associations with HDP and severe PE/HELLP syndrome. No evidence of statistically significant risk of HDP or severe PE/HELLP was observed in either cohort, nor in the combined cohort. While no significant PoO effects were detected in the HDP or severe PE/HELLP cohorts individually, the combined cohort analysis was significant for PoO effects for both rs1884082 and rs4934. Specifically, we observed (1) an increased risk of HDP/sPE/HELLP if the mother carries double copy of the variant allele, (2) a decreased risk of HDP/sPE/HELLP if the child carries the maternally-inherited copy, and (3) an increased risk of HDP/sPE/HELLP if the child carries the paternally-inherited copy. The statistically significant RRR suggests that child carriage of a maternal copy has a protective effect compared to the paternal copy, suggesting a potential imprinting effect. These findings suggest that PoO effects play a role in predisposing pregnant women toHDP and HELLP syndrome, however, further studies are needed to confirm these observations.

Our analysis on individual SNPs did not find a statistically significant association between rs1884082 and rs4934 polymorphisms and HDP, severe PE/HELLP syndrome, or the combined cohort. However, a study by Chelbi et al. found that the T allele of the rs1884082 SNP was a potential risk factor IUGR, while the rs4934 SNP was related to an increased risk of PE, particularly in the Hispanic population [

19]. Our combined PoO analysis suggests that the source of the inherited risk allele–whether maternal or paternal–contributes to HDP risk, implicating possible maternal-fetal genotype incompatibility.

Our findings suggest that similar maternal-fetal genotype mismatches in genes such as SERPINA3 may increase the risk of HDP. This is consistent with a study by Sinsheimer et al., in which a maternal-fetal genotype incompatibility where the mother is homozygous for a null allele, and the baby inherits an antigen-coding allele from the father, triggers a harmful maternal immune response [

28]. Similarly, Palmer et al. showed that specific maternal-fetal genotype combinations can increase susceptibility to schizophrenia [

29]. These results support the idea that maternal-fetal genetic interactions likely contribute to pregnancy outcomes.

The lack of statistically significant associations for individual SNPs and haplotypes may be a reflection of relatively small sample sizes, though we cannot exclude the possibility that a mixture of maternally- and paternally-inherited alleles obscured any associations due to parental imprinting. In support of this possibility, we observed that, among the combined cohorts, both rs1884082 and rs4934 demonstrated PoO-specific effects, whereby a single copy of the maternally inherited allele is associated with a reduction in HDP risk and a single copy of the paternally inherited allele increases HDP risk. A parent-of-origin effect was defined by the interaction effect of maternally derived and paternally derived alleles [

27].

There are several limitations in this study that should be considered. First, both rs1884082 and rs4934 SNPs in the combined analysis show deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). This could be due to various reasons including, but not limited to, genotyping error, maternal-fetal genotypic interaction, selection bias, and population stratification [

30,

31,

32]. Cases in the severe-spectrum cohort were identified via self-report, with 66.1% confirmed via chart abstraction. Of the chart abstracted cases, however, all self-reported diagnoses were correctly identified. Misclassification of a control as a case is highly unlikely, but had this occurred, it would have led to a reduction in the estimated effect. The study was limited by sample size, though post-hoc power calculations indicate sufficient power to detect effect sizes larger than RR=1.8. Thus, smaller effect sizes would not be detectable in each cohort.

Lastly, the HDP cohort was predominantly Hispanic, while the severe PE/HELLP syndrome cohort were White. The lack of racial and ethnic diversity within each cohort could limit the applicability of our results.

This study also has strengths. The case-parent dyad and triad designs enable the assessment of maternal, fetal, and parent-of-origin effects. Using log-linear models, we can account for the correlation between familial genotypes [

26]. Although the study population was ethnically homogeneous within each cohort, the analysis provides insights for White and Hispanic populations and should be generalizable to any population in which these variants exist.

Conclusion

While polymorphisms and haplotypes in the SERPINA3 gene were not associated with HDP risk, a reduction in risk was observed for maternally-inherited copies of both evaluated SNPs, suggesting that genomic imprinting or maternal-fetal interaction effects may be involved. Further studies should investigate these gene associations using larger, and more diverse cohorts to reproduce these findings and improve generalizability.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme #262700 (H.K.G.). Partial support was also provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R21 HD046624-02.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the families that participated in this study for making this research possible as well as the many graduate students who volunteered their time and energy.

References

- Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(1):S1-S22.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: US Preventive Services Task Force Final Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2023;330(11):1074–1082. [CrossRef]

- Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(5):1122-1131. [CrossRef]

- Sep S, Verbeek J, Koek G, Smits L, Spaanderman M, Peeters L. Clinical differences between early-onset HELLP syndrome and early-onset preeclampsia during pregnancy and at least 6 months postpartum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Mar;202(3):271.e1-5. Epub 2009 Dec 22. PMID: 20022586. [CrossRef]

- Rachel Mathew, Benita P. Devanesan, Srijana, N.S. Sreedevi, Prevalence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, associated factors and pregnancy complications in a primigravida population, Gynecol. Obstet. Clini. Medi. 3 (2) (2023) 119–123. ISSN 2667-1646. [CrossRef]

- Martin JN Jr, Thigpen BD, Moore RC, Rose CH, Cushman J, May W. Stroke and severe preeclampsia and eclampsia: a paradigm shift focusing on systolic blood pressure. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):246-254. [CrossRef]

- Khosla K, Heimberger S, Nieman KM, et al. Long-Term Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Women After Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Recent Advances in Hypertension. Hypertension. 2021;78(4):927-935. [CrossRef]

- Fox R, Kitt J, Leeson P, Aye CYL, Lewandowski AJ. Preeclampsia: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Management, and the Cardiovascular Impact on the Offspring. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1625. Published 2019 Oct 4. [CrossRef]

- Huang YD, Luo YR, Lee MC, Yeh CJ. Effect of maternal hypertensive disorders during pregnancy on offspring’s early childhood body weight: A population-based cohort study. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 61, 761–767.

- Maher GM, O’Keeffe GW, Kearney PM, et al. Association of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy With Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):809–819. [CrossRef]

- Huang C, Li J, Qin G, et al. Maternal hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and offspring early-onset cardiovascular disease in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood: A national population-based cohort study. PLOS Medicine. 2021;18(9):e1003805. [CrossRef]

- Zhen Lim TX, Pickering TA, Lee RH, Hauptman I, Wilson ML. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and occurrence of ADHD, ASD, and epilepsy in the child: A meta-analysis. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2023 Sep;33:22-29. Epub 2023 Jun 23. PMID: 37356382. [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e1–e25.

- Auer J, Camoin L, Guillonneau F, et al. Serum profile in preeclampsia and intra-uterine growth restriction revealed by iTRAQ technology. J Proteomics. 2010;73(5):1004-1017. [CrossRef]

- Brew O, Sullivan F, Woodman A. Comparison of Normal and Pre-Eclamptic Placental Gene Expression: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0161504-e0161504. [CrossRef]

- Chelbi ST, Mondon F, Jammes H, et al. Expressional and epigenetic alterations of placental serine protease inhibitors: SERPINA3 is a potential marker of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):76-83. [CrossRef]

- de Mezer M, Rogaliński J, Przewoźny S, et al. SERPINA3: Stimulator or Inhibitor of Pathological Changes. Biomedicines. 2023;11(1):156. Published 2023 Jan 7. [CrossRef]

- Kalsheker NA. α1-antichymotrypsin. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 1996;28(9):961-964. [CrossRef]

- Chelbi ST, Wilson ML, Veillard AC, et al. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms collaborate to control SERPINA3 expression and its association with placental diseases. Human molecular genetics online/Human molecular genetics. 2012;21(9):1968-1978. [CrossRef]

- Kamboh MI, Minster RL, Kenney M, et al. Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin (ACT or SERPINA3) polymorphism may affect age-at-onset and disease duration of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(10):1435-1439. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Navarro A, González-Soria I, Caldiño-Bohn R, Bobadilla NA. Integrative view of serpins in health and disease: the contribution of serpinA3. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. Published online October 28, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Vanni S, F. Moda, M. Zattoni, et al. Differential overexpression of SERPINA3 in human prion diseases. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1). [CrossRef]

- dbSNP. NIH National Library of Medicine. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/.

- LDlink. NIH. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://ldlink.nih.gov/?tab=home.

- Gjessing HK, Lie RT. Case-parent Triads: Estimating Single- and Double-dose Effects of Fetal and Maternal Disease Gene Haplotypes. Annals of Human Genetics. 2008;70(3):382-396. [CrossRef]

- Shi M, Umbach DM, Vermeulen SH, Weinberg CR. Making the most of case-mother/control-mother studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(5):541-547. [CrossRef]

- Gjerdevik M, Jugessur A, Haaland ØA, et al. Haplin power analysis: a software module for power and sample size calculations in genetic association analyses of family triads and unrelated controls. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20(1):165. [CrossRef]

- Sinsheimer JS, Palmer CG, Woodward JA. Detecting genotype combinations that increase risk for disease: maternal-fetal genotype incompatibility test. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;24(1):1-13. [CrossRef]

- Palmer CG. Evidence for maternal-fetal genotype incompatibility as a risk factor for schizophrenia. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:576318. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Turner A, Little J, et al. Positive results in association studies are associated with departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium: hint for genotyping error? Hum Genet. 2002;111:573-4.

- Namipashaki, A., Razaghi-Moghadam, Z., & Ansari-Pour, N. (2015). The Essentiality of Reporting Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Calculations in Population-Based Genetic Association Studies. Cell journal, 17(2), 187–192. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, H. F., Unwin, J., Jamison, D. L., & Cordell, H. J. (2011). Investigation of maternal effects, maternal-fetal interactions and parent-of-origin effects (imprinting), using mothers and their offspring. Genetic epidemiology, 35(1), 19–45. [CrossRef]

- Gjerdevik M, Jugessur A, Haaland ØA, Romanowska J, Lie RT, Cordell HJ, Gjessing HK. Haplin power analysis: a software module for power and sample size calculations in genetic association analyses of family triads and unrelated controls. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019 Apr 2;20(1):165. PMID: 30940094; PMCID: PMC6444579. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).