1. Introduction

Gas turbines remain a cornerstone of modern energy infrastructure, delivering both primary and dispatchable power generation while also supporting propulsion systems and industrial mechanical drives. As energy systems transition toward decarbonization and incorporate a larger share of renewable sources, the role of gas turbines is evolving. First, they are increasingly being adapted to operate on carbon-free fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia, as well as carbon-neutral synthetic fuels and low-carbon biofuels. Second, they are playing a growing role as reliable backup power sources for intermittent renewables [1,2]. The shift from steady baseload operation to flexible service—characterized by rapid load changes, frequent cycling, and extended part-load operation—has introduced new operational challenges, particularly for aging fleets. Under these conditions, multiple degradation mechanisms act simultaneously, at varying rates, including (but not limited to) fatigue crack growth, hot corrosion, erosion, tip clearance increases, and blade twist. Together, these effects reduce aerodynamic performance and overall efficiency. Frequent load fluctuations also increase the occurrence of thermal–mechanical stress cycles, making traditional degradation patterns less predictable and accelerating the overall deterioration process. These evolving operational demands underscore the need for advanced monitoring and predictive capabilities, such as hybrid AI–based digital twins, that combine physics-based degradation models with operational data to enable proactive maintenance, optimize performance, and extend the service life of critical turbomachinery assets [2,3,4,5].

The concept of the digital twin, detailed in [6], describes a virtual representation of a physical asset, system, or process that mirrors its state and behavior in real time, enabling monitoring, simulation, and analysis throughout its lifecycle. This definition has since evolved into structured frameworks for product and system design that integrate multi-source data and lifecycle considerations [7,8]. Building on this foundation, the intelligent digital twin integrates artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced analytics to enable learning from multi-source data, adaptive behavior under changing operating conditions, and support predictive decision-making [9]. This progression from descriptive and predictive modeling toward adaptive, autonomous operation represents a critical step in applying digital twin technology for complex, high-performance systems such as gas turbines [10,11].

This represents a substantial progression beyond purely physics-based methods such as conventional gas turbine diagnostic approaches, which predominantly depend on physics-based methods such as thermodynamic cycle simulations, component performance maps, and gas path analysis (GPA) [12,13,14]. Physics-based methods are interpretable and reproducible but often computationally intensive, require proprietary geometric details, but they are limited in their ability to adapt to degraded, off-design, or transient operating conditions [12,13]. In contrast, purely data-driven approaches—particularly those employing artificial neural networks (ANNs)—can capture complex, highly nonlinear relationships between sensor measurements and performance metrics, enabling rapid inferences. However, data-driven models frequently struggle to generalize beyond their training domain and typically lack physical interpretability [14,15,16,17].

The limitations of both purely physics-based and purely data-driven methods have motivated the emergence of hybrid artificial intelligence (AI) approaches, commonly referred to as physics-informed machine learning (PIML). For instance, hybrid diagnostic frameworks that integrate artificial neural networks (ANNs) with gas path analysis (GPA) have demonstrated notable improvements in diagnostic sensitivity and degradation tracking [14,15]. Nevertheless, they remain challenged by issues such as limited data quality, sparse fault representation, and the need to maintain alignment with underlying physical principles [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. These methods embed physical constraints, simulation outputs, or governing equations directly into learning architectures, enhancing predictive accuracy while preserving consistency with physical laws. Hybrid AI research for gas turbine modeling is progressing along several parallel and interrelated trajectories, many of which share common mathematical and computational foundations. For example, equation discovery methods, such as Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) and its open-source implementation (PySINDy) extract governing equations directly from measurement data, enabling the development of interpretable dynamic models [24]. Physics-constrained neural networks, including Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Navier–Stokes Flow Net (NSFnet) variants, embed conservation laws directly into loss functions to model laminar and turbulent flows, with residual-based attention mechanisms improving convergence [5,25,26,27]. Operator learning frameworks, such as the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) and Fourier DeepONet, learn resolution-invariant mappings for parametric partial differential equations (PDE)s, enabling scalable, mesh-independent aerodynamic and thermal predictions [28,29,30,31,32]. Architectures that preserve physical invariants, such as Lagrangian Neural Networks (LNNs) and graph neural networks (GNNs), offer scalable inference for coupled thermo fluid–structural systems [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Physics-informed ML methods have also been applied to high-fidelity thermal processes that are directly relevant to gas turbine operation and related manufacturing and coating processes. In manufacturing applications [39], these methods enable accurate prediction of complex, transient temperature fields during processes such as thermal barrier coating deposition, additive manufacturing, and component heat treatment, where precise thermal control is critical for microstructural integrity and lifespan of hot section gas turbine components. In forced convection systems [40], physics-informed architectures have achieved real time prediction of transient thermal behavior by embedding governing heat transfer equations into neural networks, allowing for fast, physically consistent simulation under changing flow and boundary conditions.

These capabilities are directly applicable to gas turbine intelligent digital twins and their embedded sub-simulations, enhancing preventive maintenance strategies and remaining life assessments when and where required.

2. Hybrid AI Methodologies for Gas Turbine Applications: Description and Advantages and limitations

Hybrid artificial intelligence (AI) for gas turbines real-time diagnostics, predictive maintenance, and performance optimization, make use of the strengths of data-driven learning and physics-based modeling. This is to overcome the limitations each approach has when applied independently. Based on a comprehensive literature review, four distinct categories of hybrid methods are identified:

ANN-augmented thermodynamic models;

Physics-integrated operational architectures;

Physics-constrained neural networks and Computational Fluid Dynamics surrogates;

Generative and model discovery approaches.

Each category presents distinct trade-offs in terms of generalizability, accuracy, computational cost, and suitability for real-time implementation.

2.1. ANN-Augmented Thermodynamic Models

ANN-augmented thermodynamic models couple classical thermodynamic simulations and gas path analysis with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to improve diagnostic sensitivity, robustness, and real-time applicability. These methods are widely used for component-level diagnostics, degradation tracking, and health assessment [41].

ANN modules learn nonlinear relationships from synthetic or historical datasets, enabling rapid inference while retaining interpretability through their physics-based foundation [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. For example, [46] developed a hybrid diagnostic framework that couples artificial neural network modules with thermodynamic performance maps to infer compressor flow capacity reduction and turbine efficiency loss, enhancing fault detection accuracy and enabling earlier warnings.

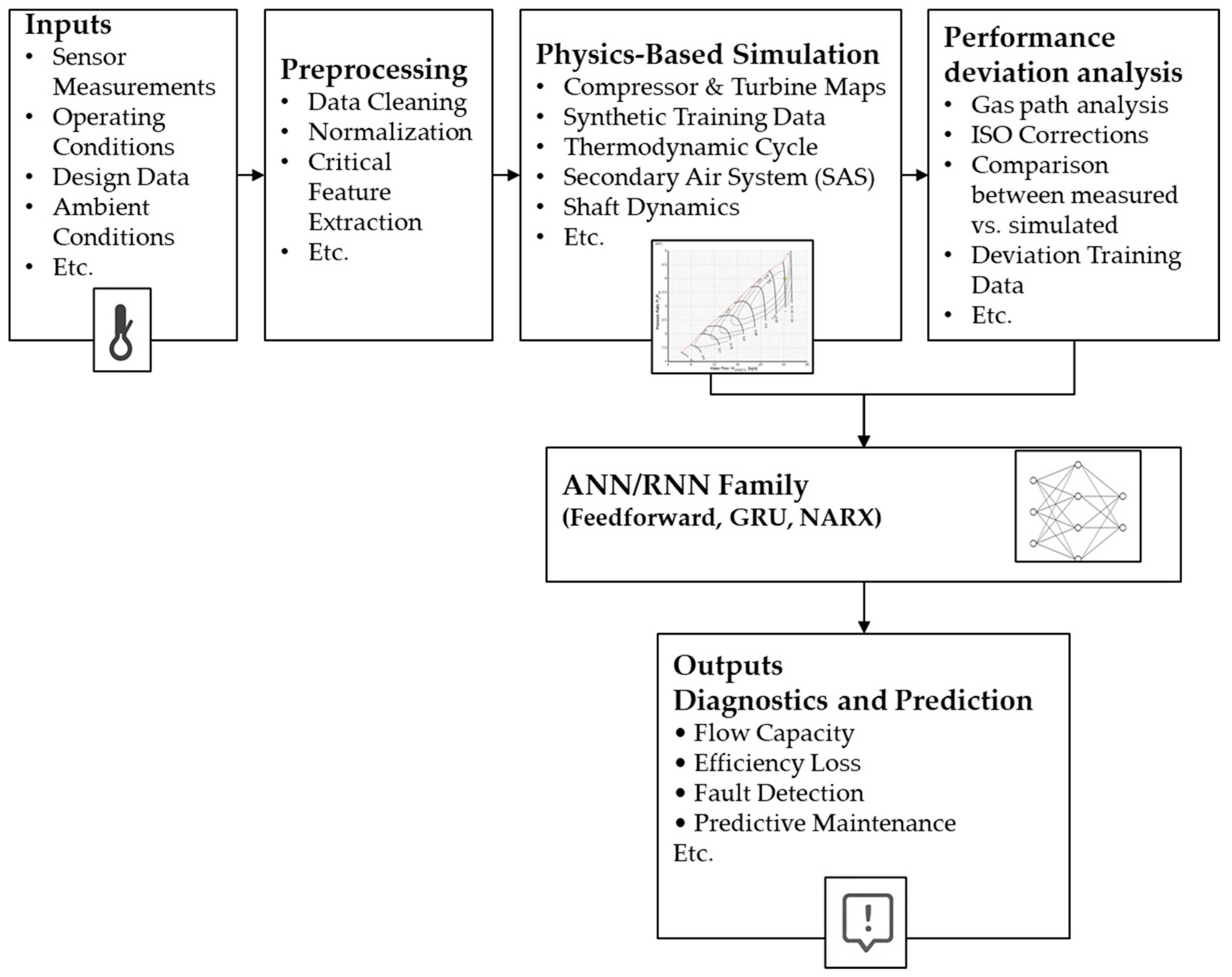

As illustrated in Figure 1, these models use process-map-based thermodynamic simulations to generate training data under both nominal and degraded scenarios, enabling the prediction of critical gas path parameters. Physics-based thermodynamic cycle or component simulations are used to create synthetic datasets representing degradation modes such as compressor fouling or turbine efficiency loss. ANNs are then trained to map measurable engine parameters such as pressures, temperatures, or fuel flow. These mappings are then used to estimate unmeasured health and performance indicators such as flow capacity, efficiency loss, or fault severity [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. By learning nonlinear relationships between observed sensor data and hidden degradation states, these hybrid models extend the capability of classical GPA while enabling robust, real-time health monitoring.

ANN-augmented thermodynamic models have demonstrated robustness to noisy sensor data and adaptability under off-design operating conditions [17,50,51,52]. They rely largely on synthetic datasets generated from thermodynamic simulations, preserve interpretability through their grounding in cycle physics, and focus on component-level health indicators. However, such models often require domain adaptation or retraining when transitioning from simulation-generated datasets to real engine environments, owing to mismatches in operating conditions, sensor noise characteristics, and unmodeled degradation effects [4,13].

[42,43,44,45] developed hybrid diagnostic models for gas turbines that integrate ANNs with thermodynamic cycle simulations to estimate component degradation levels such as compressor flow capacity loss and turbine efficiency reduction, thereby improving early fault detection using simulated deterioration data. Similarly, [46,47,48] proposed a distributed ANN-based gas path analysis (GPA) framework employing classification, auto-associative, and approximation networks to isolate and quantify multiple simultaneous faults. Their system demonstrated robust fault identification, localization, and severity estimation under nonlinear and noisy operating conditions, outperforming conventional GPA approaches [53].

2.1.1. Advantages:

Improved diagnostic accuracy compared with purely physics-based models, particularly in nonlinear or multivariate degradation scenarios [43,48];

Fast inference speeds suitable for real-time and field-deployed applications. While inference is computationally efficient, the training phase can involve substantial overhead depending on the fidelity and validity of the underlying thermodynamic simulations [8,11];

Ability to leverage synthetic training datasets even when historical fault data are limited [9,11];

Demonstrated robustness to noisy sensor data and adaptability to off-design operating conditions [17,50,51,52].

2.1.2. Limitations:

Strong dependence on the quality and completeness of simulation data; any inaccuracies or biases in the input data directly propagate into the trained model, reducing its reliability in real-world applications [9,25];

Limited coverage of degradation modes in the simulation dataset may bias predictions and reduce the model’s ability to generalize to unobserved faults [9,25];

Limited extrapolation beyond the design space represented in the simulation or training dataset [3,10];

The “black-box” characteristics of ANNs can reduce physical interpretability unless explainable AI techniques are applied [17,50,51,52,53].

To address the former limitation, hybrid approaches increasingly incorporate physics-informed neural networks [41], grey-box models that combine thermodynamic principles with data-driven ANN modules [9], or explainable AI methods [54]. These strategies aim to ensure predictions remain physically meaningful while retaining the flexibility and adaptability of data-driven learning.

2.2. Physics-Integrated Operational Architectures

Physics-integrated operational architectures combine real-time data with modular physical models and embedded AI elements such as physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), ANN surrogates, and advanced optimization algorithms to deliver full system-level decision support and operational intelligence. These architectures extend beyond algorithm development, focusing instead on control, load allocation, predictive maintenance, and fleet-level operational planning [9,11,22,54,55].

Thermodynamic cycle models and component conservation equations provide the physically consistent backbone for these frameworks, ensuring accurate estimation of critical parameters such as turbine inlet temperature (TIT) and specific fuel consumption (SFC). Embedded AI modules enhance computational speed, improve robustness to sensor uncertainty, and capture nonlinear degradation effects that classical physics models alone cannot fully represent.

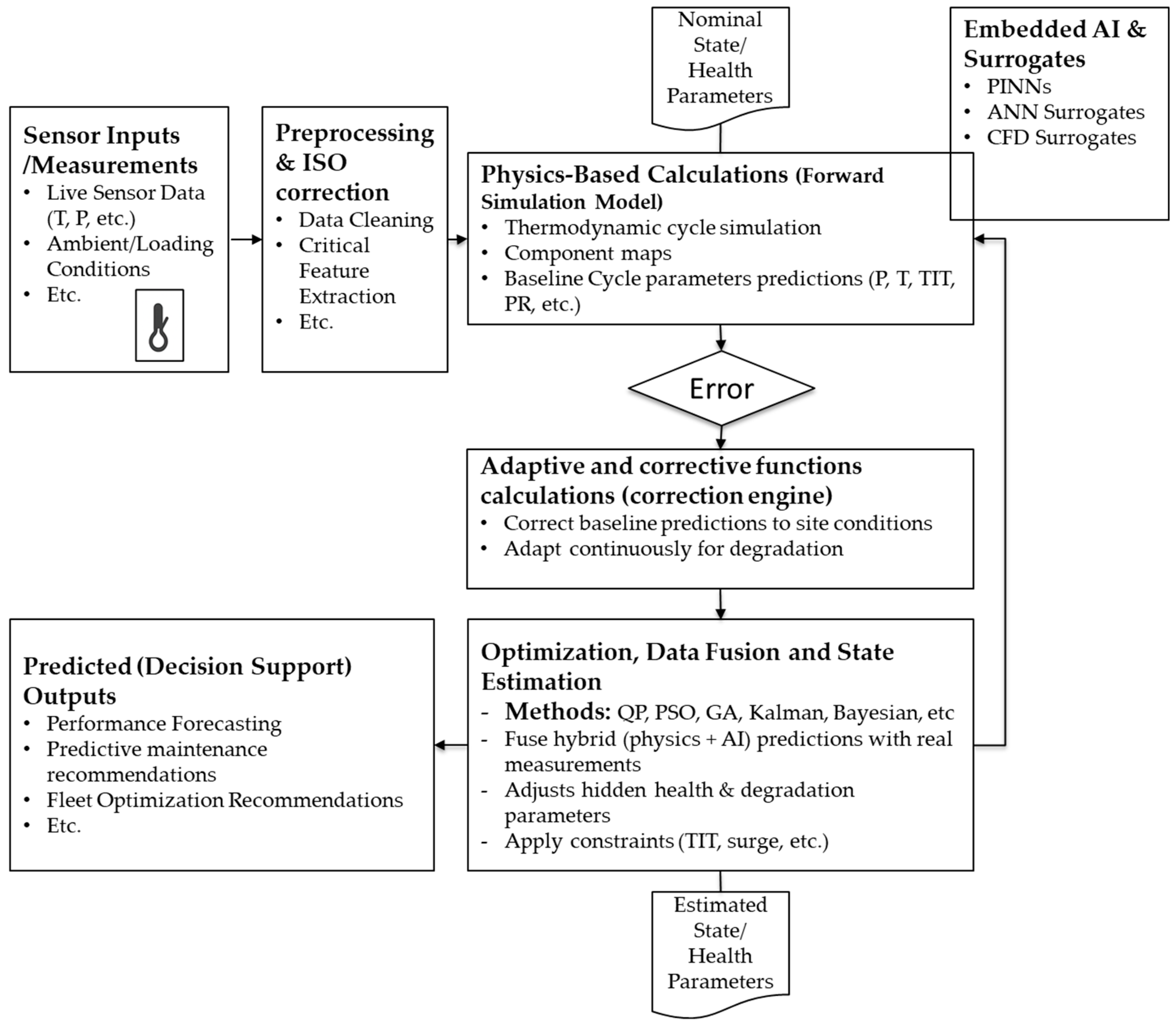

Figure 2 illustrates a representative architecture in which live measurements are fused with simulation models and AI surrogates to infer hidden states, optimize performance, and deliver actionable control recommendations. PINNs integrate physical constraints directly into their loss functions [19,54], while ANN surrogates trained on high-fidelity simulations replace computationally expensive physics modules to enable fast, real-time operation [11,55]. Optimization layers, such as particle swarm optimization (PSO), quadratic programming (QP) and other advanced techniques, are employed. In the case of PSO, this evolutionary algorithm which is inspired by swarm behavior, efficiently explores the solution space, while QP provides a deterministic, mathematically rigorous approach for constrained optimization. Combined, these methods improve control performance and overall energy efficiency [22,54,55]

A representative example is the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) Turbine Digital Twin, which integrates live sensor data with Numerical Propulsion System Simulation (NPSS)–based thermodynamic modules and AI-enabled virtual sensors to provide operator-focused performance forecasting, anomaly detection, and predictive maintenance capabilities [56]. General Electric (GE) Vernova applies digital twin technologies such as SmartSignal predictive analytics and three-dimensional visualization twins to optimize power plant performance, increase reliability, and reduce operating costs across more than 7,000 monitored assets worldwide [57]. Siemens employs its Autonomous Turbine Operations and Maintenance (ATOM) framework, an agent-based intelligent digital twin that combines system-level physical modeling with AI optimization layers to support fleet operations, load sharing, and long-term operational planning [58].[54] demonstrated a PINN-enabled intelligent digital twin that accurately predicted hidden variables such as turbine inlet temperature (TIT) and specific fuel consumption (SFC) under sensor uncertainty, while [55] implemented an ANN-surrogate-based architecture for combined heat and power (CHP) gas turbines, enabling real-time modeling of degradation, load sharing, and control.

2.2.1. Advantages:

Real-time, system-wide representation of engine behavior using live sensor data integrated with physics-based thermodynamic cycle models such as NPSS [56];

Embedded AI modules (ANN surrogates, PINNs, PcNNs) support adaptive performance modeling, virtual sensing, anomaly detection, and predictive maintenance [16,22,34,54,55];

Demonstrated improvements in diagnostic accuracy and degradation tracking under nonlinear, noisy, or off-design operating conditions compared to classical gas path analysis [9,10,33];

Computational efficiency through surrogate models (ANNs, operator-learning networks, CFD surrogates), enabling rapid virtual prototyping, design iteration, and real-time optimization [27,32,42];

Scalable architectures suitable for plant-wide integration and fleet-level deployment, as demonstrated in EPRI’s operator-focused twin, GE Vernova’s SmartSignal platform, and Siemens’ ATOM framework [56,57,58];

Generative and model discovery methods (GANs, RNNs, SINDy) augment sparse datasets and extract interpretable governing equations, enhancing model robustness for rare-event prognostics and transient validation [39,45,63].

2.2.2. Limitations:

Integration complexity, including sensor synchronization, model calibration, and the need for robust data pipelines when interfacing with existing Condition Monitoring Systems (CMS)s [56];

Dependence on the quality and coverage of training data; poor representation of degraded or transient conditions may bias predictions [9,42,49];

ANN-heavy approaches exhibit “black box” behavior with reduced interpretability unless constrained by physics-informed or explainable AI methods [42,47,51];

High computational costs during training for PcNNs, PINNs, and generative surrogates due to embedded PDE residuals and automatic differentiation, with additional challenges in stability and convergence [20,21,29];

Cross-platform generalization is limited; calibrated twins often require domain adaptation, and standardized benchmarks for validation are lacking [42,49,55];

Cybersecurity and latency concerns in interconnected SCADA and historian environments, exposing vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure [56,57];

High development and lifecycle costs, requiring multidisciplinary expertise in thermodynamics, control systems, data science, and IT infrastructure [16,22,54].

2.3. Physics-Constrained Neural Networks and CFD Surrogates

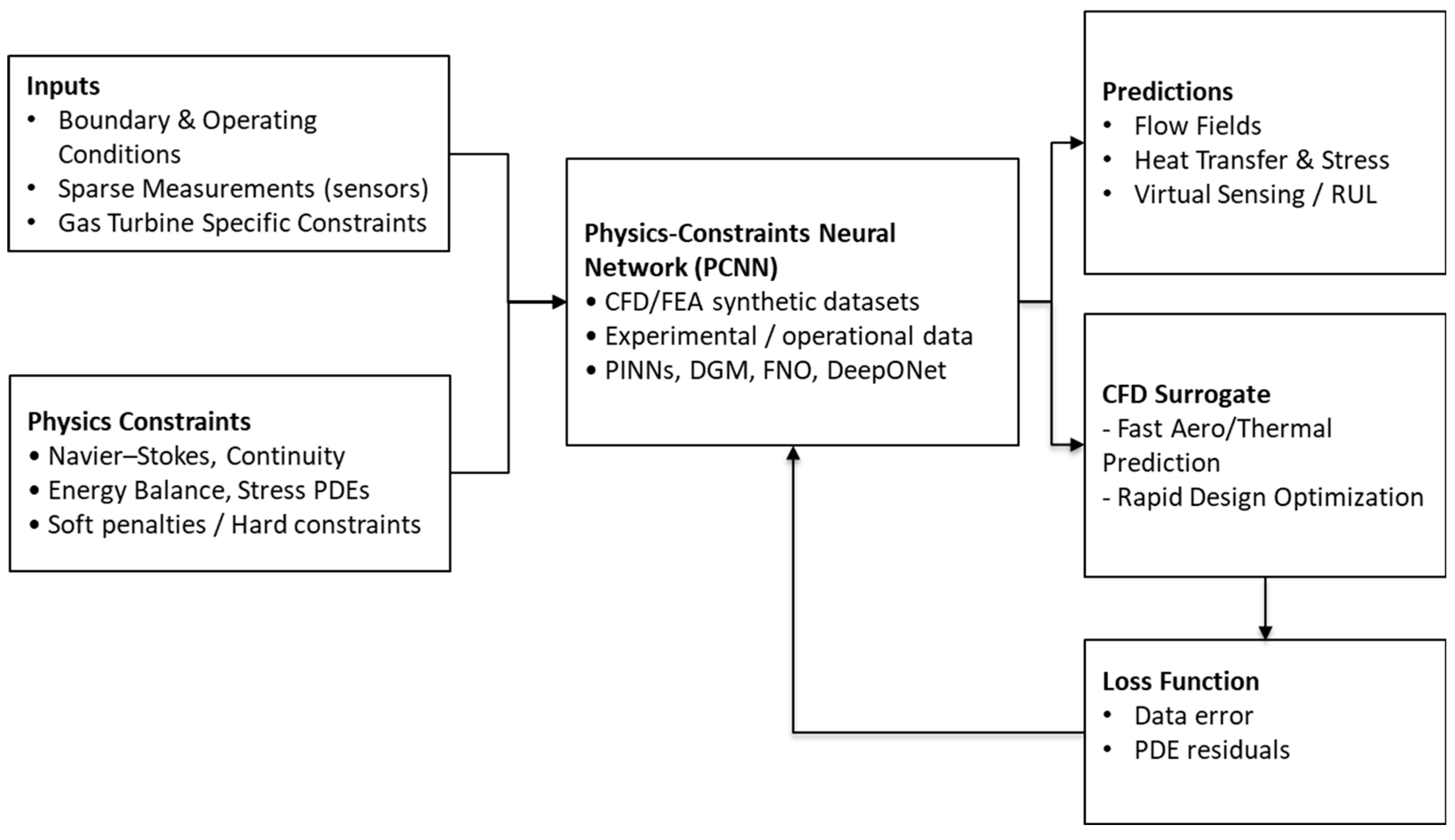

Physics-constrained neural networks embed governing physical laws such as Navier–Stokes, continuity, and energy balance equations directly into the training process, ensuring physically consistent predictions even when labeled data are sparse or noisy [8,10,21,23,31,59]. These constraints may be imposed as soft penalties in the loss function or as hard constraints within the network architecture, thereby enforcing adherence to conservation laws such as the non-isothermal Navier–Stokes equations [26] and energy balance principles. By integrating these physical priors, PcNNs reduce dependence on dense experimental datasets and bridge the gap between purely data-driven models and high-fidelity physics-based simulations. A typical PcNN workflow and CFD surrogate pipeline for gas turbine applications is illustrated in

Figure 3, where geometry, boundary conditions, and operating parameters are provided as inputs, and embedded constraints ensure flow, thermal, and structural predictions that remain consistent with fundamental physics.

Applications in gas turbines include flow-field inference, heat-transfer analysis, structural stress estimation, and virtual sensing. For example [19] applied Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) to reconstruct temperature and velocity fields within turbine passages using sparse sensor measurements, embedding Navier–Stokes and energy equation residuals into the loss function to improve generalization and physical fidelity. [21] reviewed broader PINN applications in industrial gas turbines, including aerodynamic and aero-acoustic field estimation, blade flutter and fatigue prediction, combustion instability diagnostics, and turbine vane heat-transfer modeling. Likewise, [39] demonstrated how physics-informed learning can solve conductive and convective heat-transfer PDEs in high-temperature engineering applications, showing that embedded physics constraints can yield reliable predictions even when experimental thermal data are limited. Foundational approaches include Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [31] and the Deep Galerkin Method (DGM) [32], which enable solving forward and inverse problems for nonlinear PDEs without requiring structured meshes. These examples highlight the suitability of PcNNs for predicting coupled aero-thermal behavior in turbine components, where flow and heat transfer are closely linked to degradation mechanisms such as thermal fatigue and creep. PcNNs also enable the development of CFD surrogate models, significantly reducing computational cost compared to conventional solvers. [60] introduced a transformer-based surrogate for three-dimensional compressible flow prediction in axial compressors without mesh generation, enabling near-instantaneous aerodynamic predictions for early-stage design optimization. [61] applied deep learning to model the impact of manufacturing and build variations on multistage axial compressor aerodynamics, showing how high-fidelity synthetic datasets can improve surrogate accuracy for complex multistage flows. Other surrogate models leveraging convolutional neural networks, graph neural networks, and generative models trained on high-fidelity CFD datasets [1,13,17,29,62,63] have achieved substantial speed-ups while maintaining accuracy. [45] developed a transformer-based, data-driven AI model for turbomachinery compressor aerodynamics that enables rapid approximation of 3D flow solutions from CFD data. Although accuracy decreases for designs far outside the training distribution, the method provides a computationally efficient surrogate for aerodynamic design and optimization. Trained on high-resolution compressor flow simulations, the model reproduces key aerodynamic features and allows derivation of performance metrics such as efficiency. Operator learning architectures extend these capabilities further: the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) and Fourier DeepONet can learn full solution operators for entire families of PDEs, enabling mesh-independent, resolution-invariant predictions across different geometries and operating regimes [25,28,64,65]. These approaches support virtual sensing of otherwise unmeasurable states, accelerated aerodynamic and thermal design iterations, and physically consistent diagnostics and prognostics.

2.3.1. Advantages:

Physically consistent outputs even when labeled data are sparse or noisy [13,22,60];

Reduced reliance on labeled datasets through embedded physical laws [3,8,10,21,23,59];

Fast surrogate predictions for flow, thermal, and stress analyses, enabling rapid design optimization and diagnostics [1,13,17,29,60,62,63];

Resolution-invariant learning using operator learning frameworks Fourier Neural Operator (FNO), Fourier DeepONet for generalization across geometries and operating conditions [25,28,64,65,66,67,68].

2.3.2. Limitations:

High computational cost during training due to embedded PDE residuals and automatic differentiation [10,23];

Numerical stability and convergence challenges, especially in multi-physics environments [13,62,63];

Limited transferability across turbine platforms unless domain adaptation or transfer learning is applied [1,17,29];

Lack of standardized benchmarks and evaluation protocols for cross-platform validation [8,21].

2.4. Generative and Model Discovery Approaches

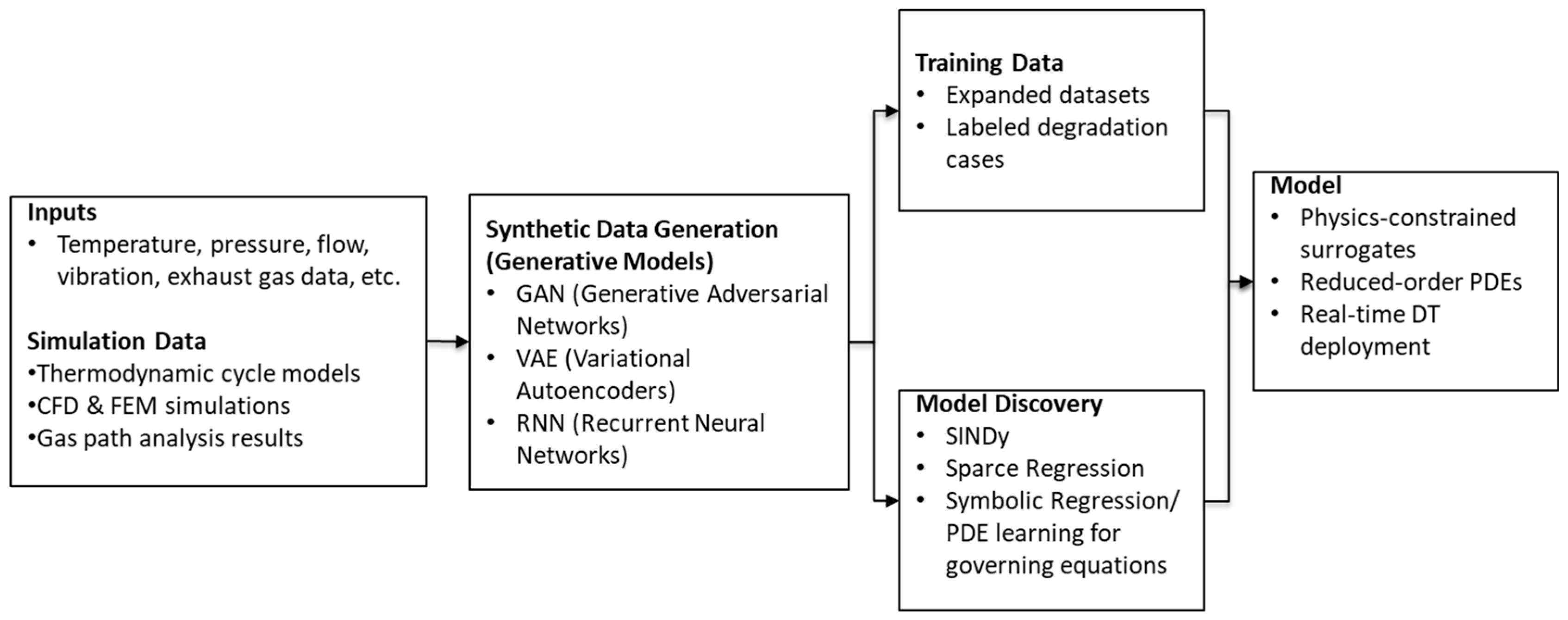

Generative and model discovery approaches address challenges related to data scarcity, interpretability, and modeling of complex multi-component interactions in gas turbine systems. These methods are particularly valuable when operational fault data are rare, extreme events are underrepresented, or physics-based models are incomplete or too computationally expensive for real-time deployment [8,69]. Generative and model discovery can be further classified into three methods: generative models, which create synthetic operating scenarios to expand scarce datasets [8]; model discovery methods, which extract governing equations from data to improve interpretability [24,30,69]; and emerging architectures, which extend these capabilities to complex geometries and multi-physics systems [27,28,36,37,65].

2.4.1. Generative Models

Techniques such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) generate synthetic sensor data representing rare or extreme scenarios, enabling robust model training under limited data conditions [8]. Beyond diagnostics, generative AI has been applied to engineering design, where neural network–aided approaches systematically explore design spaces, integrate multidisciplinary objectives, and accelerate concept evaluation. For example, [48] demonstrated how a neural network–aided technological evolution system optimized product development by learning from prior designs. Similar methodologies have been used for circular design [66], process control and fault diagnosis [67], and multidisciplinary product specification [68]. For gas turbines, such generative frameworks improve rare-event coverage, enhance design robustness, and reduce validation costs. [40] further showed that RNN architectures can provide super real-time transient thermal predictions in convection systems, demonstrating potential for virtual sensing and rare-event prognostics.

2.4.2. Model Discovery

Model discovery methods complement data generation by extracting parsimonious governing equations directly from data. Approaches such as Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) [69] and its PySINDy implementation [24] produce interpretable reduced-order models suitable for control, fault detection, and diagnostics in regimes not captured by classical simulations. However, applying model discovery in practice requires careful feature engineering, noise filtering, and domain knowledge to prevent spurious dynamics from being identified as governing equations.

Figure 4 illustrates the combined workflow: synthetic data generation expands scenario coverage, while model discovery identifies simplified yet physically meaningful system dynamics. This integration improves rare-event representation and strengthens hybrid intelligent digital twins.

2.4.3. Emerging Architectures

Recent advances extend these methods to scalable multi-physics inference. Physics-informed graph neural Galerkin networks [36], graph convolutional neural networks [37], and Discretization Net [27] embed mesh connectivity and discretization principles into learning architectures, achieving high accuracy on irregular domains, accelerating Navier–Stokes solutions, and improving virtual sensing from sparse measurements [30]. Energy-preserving designs such as Lagrangian Neural Networks (LNNs) [33] further enable robust inference across interdependent subsystems. Together, these advances move beyond data augmentation and equation discovery toward physics-consistent digital twins, with applications in hot-gas-path monitoring, secondary air system modeling, and adaptive flow/thermal field reconstruction.

2.4.4. Advantages:

Synthetic data augmentation, improving model robustness under rare or previously unobserved conditions [8,40];

Equation discovery and interpretability, supporting reduced-order modeling, control and diagnostics [24,69];

Scalable graph-based and energy-preserving architectures for complex multi-component systems [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

2.4.5. Limitations:

Generative models may produce physically unrealistic signals if not properly constrained [8,40];

Equation discovery methods such as SINDy are sensitive to noise and feature selection [69];

Graph-based and energy-preserving neural architectures can be computationally demanding when scaled to full-system or fleet-level applications [27,30,36,37].

Integrating generative, discovery, and graph-based methods into industrial digital twins requires rigorous validation to ensure regulatory compliance, user confidence, and robustness under unseen operating conditions. Without explicit physical constraints, generative models may produce infeasible outputs such as negative mass flow rates, unrealistic efficiency values, or fail to capture the coupled thermo-fluid–structural dynamics of gas turbines. Likewise, model discovery techniques risk misidentifying governing equations when trained on noisy or incomplete datasets. To ensure reliability, validation mechanisms are essential. Emerging strategies include embedding physics-consistency checks, such as conservation of mass and energy laws, into training pipelines, applying adversarial filtering to reject non-physical synthetic signals, and cross-validating synthetic scenarios against high-fidelity CFD or thermodynamic simulations before deployment [8,69]. Analogous safeguards are already being adopted in other domains. In aerospace, physics-informed GANs have been used to generate turbulence-consistent flow fields. In manufacturing, VAEs constrained by metallurgical rules ensure plausible microstructural evolution [8,39,40]. These parallels underscore that combining generative AI with physics-based validation is critical to ensuring that synthetic data strengthens—rather than undermines—the robustness of intelligent gas turbine digital twins.

3. Results

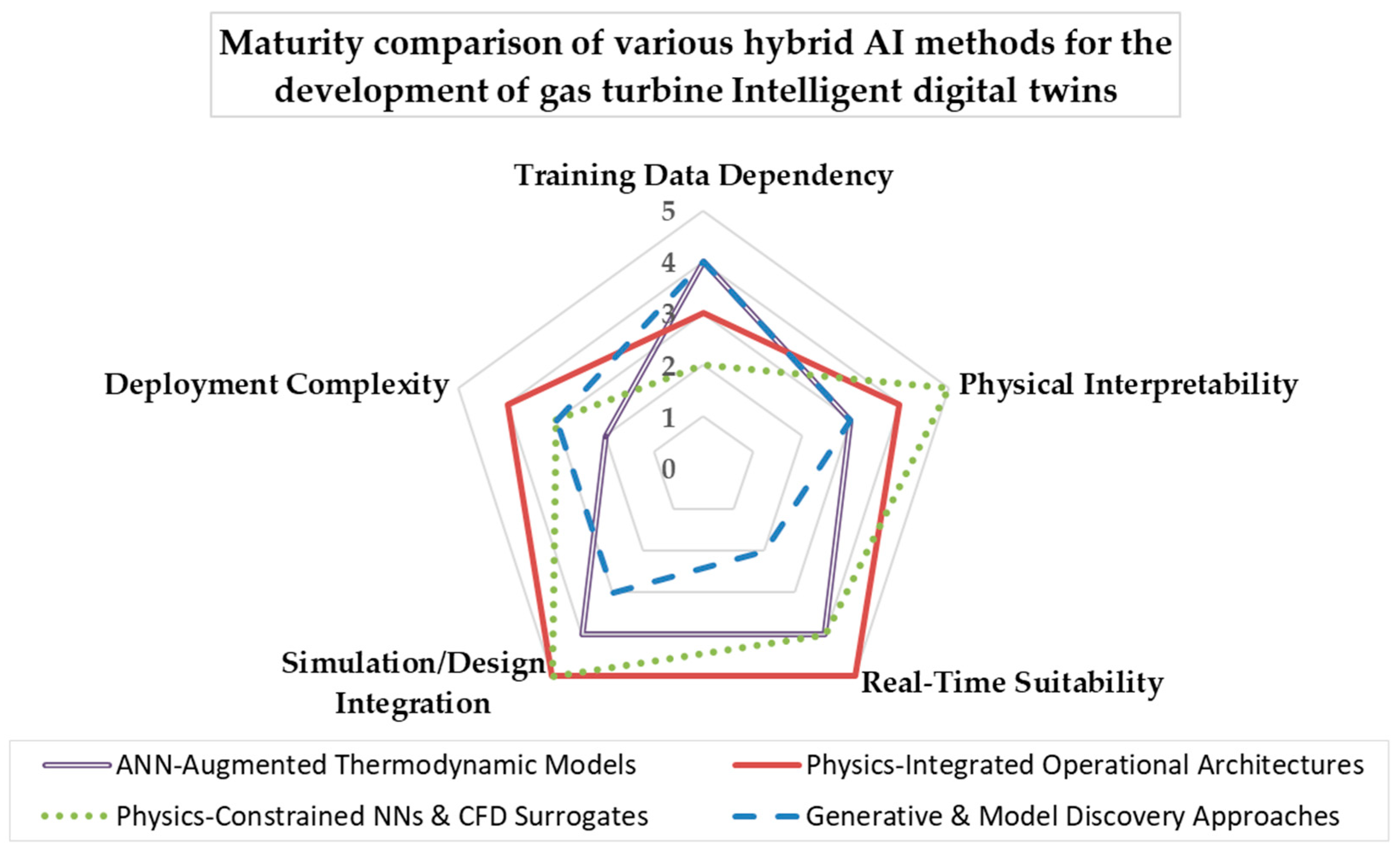

The comparative analysis shows that no single hybrid AI method is best for all gas turbine digital twins. Each approach works better in certain contexts. The choice depends on the goal such as online diagnostics, component-level optimization, or fleet-wide asset management. Results also depend strongly on available computational resources and the quality of data. To evaluate these approaches systematically, a novel maturity classification framework is developed based on five key criteria:

Data dependency (simulation-driven, sensor-driven, or physics-driven);

Physical interpretability (low, medium, or high transparency of learned relationships);

Deployment complexity (computational effort and integration burden);

Compatibility with simulation/design workflows (ability to integrate with thermodynamic models, CFD, or structural solvers);

Real-time capability (suitability for online diagnostics, control, or prognostics).

The radar plot in

Figure 5 illustrates the comparative maturity of hybrid AI approaches across five key criteria. Maturity is evaluated on a 1-5 scale:

1–2 indicate low maturity, representing methods that are limited or not widely deployable;

3 reflects medium maturity, covering approaches with potential but notable gaps;

4–5 denote high maturity, corresponding to robust, proven, or scalable methods suitable for practical deployment.

First, ANN-augmented thermodynamic models are entry-level solutions. They require substantial amounts of synthetic or historical datasets [10,42]. Their interpretability is moderate, as they retain some transparency from the thermodynamic baseline but depend on black-box ANN layers. Deployment complexity is relatively low, which makes them practical for component-level diagnostics and degradation tracking. They integrate reasonably well with simulation workflows such as gas path analysis and provide medium–high real-time suitability, making them effective for rapid health monitoring [10,41,43,70,71].

Second, physics-integrated operational architectures represent the most mature category. They combine live sensor data with modular physics-based models, AI surrogates, and optimization algorithms [56,57,58]. Their interpretability is high because the physics modules anchor the AI components, and they integrate strongly with simulation and design tools. These systems achieve the highest maturity for real-time suitability, enabling adaptive control, predictive maintenance, and fleet-level decision support. However, they require substantial volumes of operational data and present high deployment complexity, including the need for robust data pipelines and advanced computing infrastructure [56].

Third, physics-constrained neural networks (PcNNs) and CFD surrogates provide a balanced trade-off. By embedding governing equations directly into training, they reduce data dependency and achieve very high interpretability [17,21,29,31]. They are particularly suitable for virtual sensing, thermal and flow field reconstruction, and rapid design iteration. Their strong alignment with CFD and structural analysis workflows ensures excellent simulation compatibility, while their real-time suitability is medium to high once training is complete. Deployment complexity is moderate, reflecting the significant training demands and computational cost [25,36,62].

Finally, generative and model discovery approaches remain at an early stage of maturity. Generative models such as GANs, VAEs, and RNNs can create synthetic datasets to address data scarcity, while discovery methods such as SINDy extract simplified governing equations [8,24,69]. These approaches show promise for rare-event prognostics, transient validation, and synthetic data augmentation, but their interpretability is only moderate and their reliance on diverse datasets remains high [8,39,40]. Real-time suitability is limited, as most applications remain experimental or offline. Their simulation and design integration is also low-to-moderate, since they typically complement rather than directly embed within engineering workflows. Deployment complexity is moderate but validation requirements are significant, as unconstrained generative models may produce non-physical signals. Overall, these methods should be regarded as exploratory rather than production-ready, representing a frontier for future research rather than a proven industrial standard.

Together, these categories show a clear path of development. It begins with ANN models for component-level monitoring, moves through physics-constrained surrogates and mature hybrid operational architectures, and extends to generative and discovery methods. These newer approaches are still in the research stage, but they offer ways to handle rare events and data gaps. This progression reflects an evolution toward fully adaptive, fleet-integrated intelligent digital twins.

4. Discussion and Future trends

This section examines the maturity of hybrid AI methods, the barriers that limit their deployment, and the opportunities for advancing intelligent gas turbine digital twins. It also highlights practical integration challenges and proposes a layered hybrid AI framework for future development.

4.1. Comparative Maturity of Hybrid AI Methods

The maturity comparison presented in the results section 3 shows a clear progression from component-level entry points to fully integrated, adaptive system-level platforms. ANN-augmented thermodynamic models remain practical early-stage solutions due to their low deployment complexity and ease of implementation. However, their heavy reliance on synthetic datasets and limited interpretability restricts their adaptability to evolving operational scenarios [47,49]. At the opposite end, hybrid intelligent digital twins with embedded AI represent the highest maturity level, enabling real-time adaptive control, predictive maintenance, and fleet-wide optimization through continuous sensor data integration [5,11,21,50,56]. These advanced capabilities, however, come at the cost of high deployment complexity, requiring significant infrastructure and robust data pipelines.

Physics-constrained neural networks (PcNNs) and CFD surrogates provide a middle ground. By embedding governing equations, they reduce data needs and improve interpretability. This makes them well suited for virtual sensing, thermal and flow field reconstruction, and rapid design iteration [17,25,27,28,31,33,34,35,36,39,45,59].

Generative and model discovery approaches remain less mature. They address rare-event data scarcity and improve interpretability by generating synthetic scenarios and discovering governing equations [8,24,30,37,40,69]. However, most applications are still offline, with limited real-time use. Similar patterns are visible in aerospace, where physics-informed operators, neural fields, and graph-based surrogates provide scalable alternatives to high-fidelity CFD for aerodynamic flow prediction and aeroelastic analysis [72,73,74,75]. These advances show lessons that can transfer to gas turbine digital twins, which face similar challenges of nonlinear dynamics, multiphysics coupling, and real-time requirements.

Overall, the trajectory is clear: starting with ANN-based models, moving through physics-constrained surrogates and hybrid operational frameworks, and extending to generative approaches for rare-event readiness. This aligns with evidence that hybrid AI outperforms purely data-driven or purely physics-based methods under degraded or uncertain conditions [19,22,42,43]. It also reflects industry trends toward multi-fidelity data fusion [71] and Bayesian PINNs for uncertainty-aware decision-making [70].

4.2. Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the clear progress across hybrid AI categories, several common challenges continue to limit their full-scale deployment in intelligent gas turbine digital twins. Data scarcity remains a primary barrier: high-quality degraded-condition datasets are rare, and there is no standardized, open benchmarking framework for training and validation [3,4,8,11,62], making it difficult to evaluate competing approaches or accelerate technology adoption. High computational cost is another constraint, as real-time CFD surrogates and physics-constrained networks require substantial processing resources to operate within industrial timeframes [25,27,28]. Integration complexity adds further difficulty. Embedding hybrid AI into existing SCADA and plant control networks demands secure, low-latency data pipelines and strict compatibility with established operational protocols [56]. Integration must not compromise these core functions.

At the same time, the opportunities are significant. Generative models can expand limited datasets with realistic rare-event scenarios, improving model robustness under critical fault conditions [8]. Transfer learning offers a pathway to cross-platform generalization, enabling models trained on one turbine type to adapt efficiently to others [9]. Multimodal sensor fusion can strengthen situational awareness by integrating vibration, temperature, acoustic, and operational logs into a unified operational picture [71]. Embedding hybrid AI into secure, cloud-enabled digital twin platforms would support fleet-level lifecycle optimization, centralized monitoring, and coordinated decision-making across assets [56,57,58]. Finally, uncertainty quantification methods such as Bayesian PINNs can improve the trustworthiness of predictions, providing operators with confidence in AI-driven recommendations under uncertain or degraded conditions [70].

Operational Integration of Hybrid AI Intelligent Digital Twins

A critical but often underexplored challenge for hybrid AI digital twins is their integration into the operational ecosystem of gas turbine plants. While SCADA and cybersecurity concerns are frequently mentioned, successful deployment also depends on alignment with control room practices, reliability standards, and regulatory compliance.

First, control room practices and operator trust are decisive for adoption. Hybrid AI predictions must be communicated through operator-facing dashboards in terms of conventional key performance indicators (e.g., efficiency, heat rate, turbine inlet temperature) rather than opaque anomaly scores. Experience from the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) Turbine Digital Twin shows that embedding AI-driven virtual sensors and predictive health indicators directly into SCADA displays improves operator acceptance and supports daily decision-making [56]. Similarly, GE Vernova’s digital twin integrates AI outputs into performance dashboards that enable load adjustments and cost-optimization strategies [57]. Siemens’ ATOM platform extends this approach to fleet operations, combining AI with physical models for load sharing and maintenance planning [58]. These examples demonstrate that human–machine interface considerations are as critical as modeling accuracy.

Second, reliability standards and safety protocols define the operational envelope within which hybrid AI must function. Gas turbine fleets operate under strict reliability and safety requirements, with condition-based maintenance strategies ensuring that inspection intervals and load allocations do not compromise safety margins. Hybrid AI systems must therefore embed physical constraints into optimization loops to guarantee that recommendations remain within certified operational limits. Previous reviews of diagnostic and monitoring practices [6,41,62] emphasize that long-term adoption of hybrid AI depends on demonstrable improvements in reliability and compliance with established maintenance frameworks.

Third, cybersecurity and data pipeline integrity impose additional restrictions on integration architectures. Since SCADA systems are designated as critical infrastructure, hybrid AI models must be deployed within secure, low-latency data pipelines that preserve both availability and resilience. [11] highlighted that predictive maintenance platforms must address issues of sensor synchronization, robust pipelines, and secure integration with existing supervisory control systems. Likewise, [51] emphasized that embedding advanced ML frameworks into physical systems introduces additional complexity in ensuring stable and secure operation. These studies underscore that operational integration is not only a technical challenge but also a regulatory and organizational one.

Together, these considerations highlight that hybrid AI deployment requires not only algorithmic advances but also the design of secure, operator-trusted, standards-compliant integration pathways that enable intelligent digital twins to be adopted at scale in critical energy infrastructure.

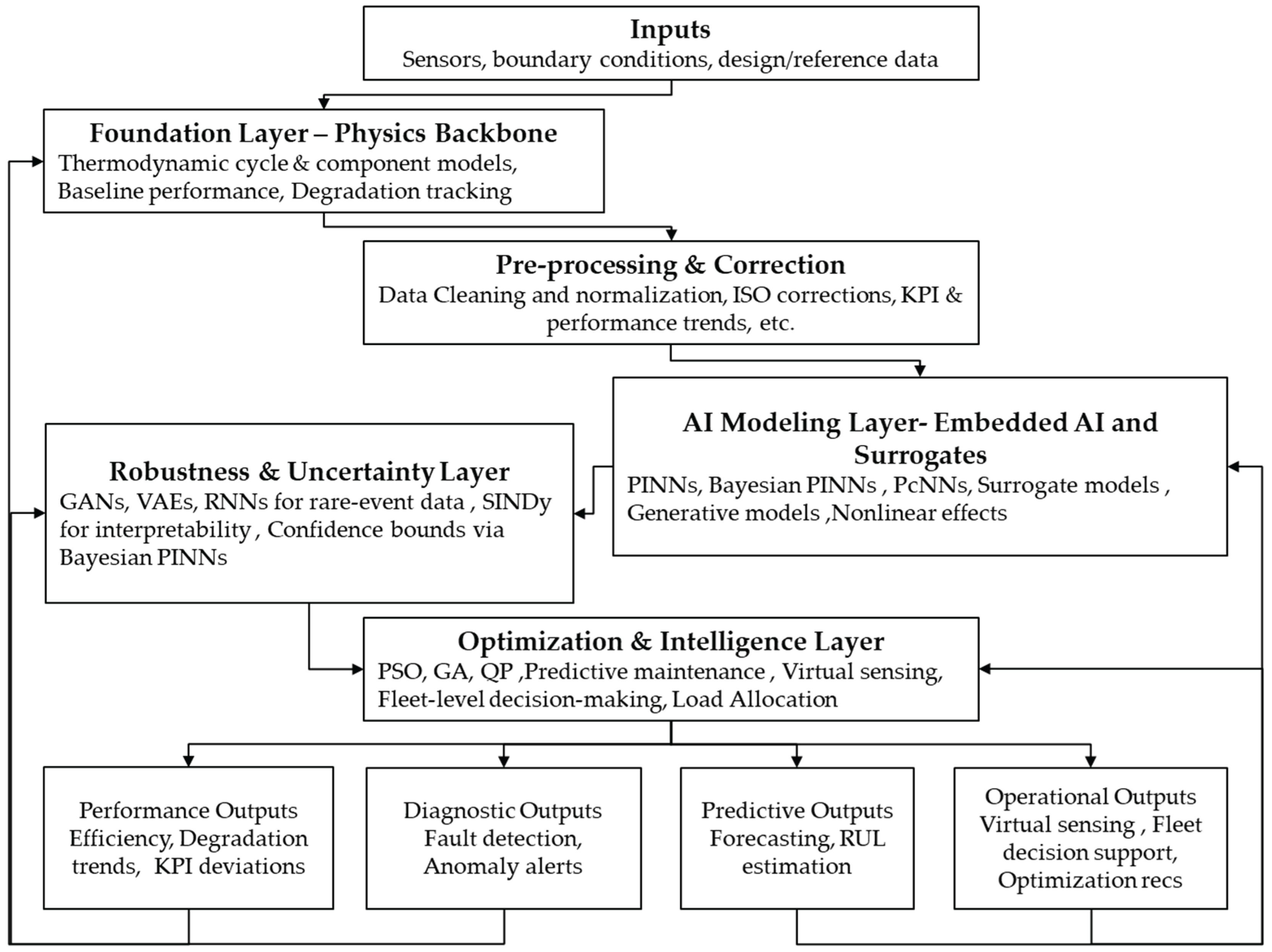

4.3. Future Research Directions and Proposed Hybrid AI Framework

Future research in hybrid AI for intelligent gas turbine digital twins should focus on four complementary priorities. First, developing standardized benchmarks and open datasets is essential to accelerate model innovation and ensure fair, transparent performance comparisons across hybrid AI methodologies [3,4,8,11,62]. Second, advancing uncertainty quantification and physics-informed transfer learning offers a pathway to more robust and generalizable intelligent digital twin solutions, capable of adapting across diverse turbine platforms and operating conditions [9,19,70]. Third, the industry must establish secure, scalable integration strategies that support plant-wide intelligent digital twins with real-time monitoring and predictive control, while ensuring cyber resilience and operational reliability [11,51,56,57,58]. Finally, there is significant potential in ensemble and layered hybrid AI architectures that merge ANN-based diagnostics, physics-constrained surrogates, and generative models to deliver rare-event readiness, improved interpretability, and faster deployment timelines [17,22,24,30,47]. To address these priorities, this review presents a layered hybrid AI framework for gas turbine intelligent digital twins. The framework shown in

Figure 6 is organized into four synergistic layers: a Physics Backbone anchoring thermodynamic and component models, an AI Modeling Layer integrating advanced learning architectures, a Robustness and Uncertainty Layer incorporating generative models and uncertainty quantification, and an Optimization and Intelligence Layer enabling predictive control and fleet-level decision-making.

4.3.1. Physics Backbone (Foundation Layer)

Physics Backbone (Foundation Layer). At the base, physics-based thermodynamic and component models provide consistent performance predictions and interpretable degradation characterization. This ensures that the digital twin remains grounded in established conservation laws and engineering principles, offering trustworthy baseline estimates for critical parameters such as efficiencies, flow capacity, and heat balance residuals.

4.3.2. AI Modeling Layer

Building upon this foundation, advanced machine learning modules extend model fidelity and speed. This includes Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [31] and Bayesian/variational PINNs [29,70] for uncertainty-aware diagnostics, as well as operator-learning surrogates—such as LSTMs, graph neural networks [34,35], and neural operators like Fourier Neural Operators (FNO) and DeepONet [28,65]. These models capture nonlinear degradation effects and accelerate computationally intensive CFD and structural simulations. In practice, PINNs can infer unmeasured combustion parameters (e.g., air–fuel ratio, combustion efficiency), while ANNs optimized with metaheuristics such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) enable rapid, multi-output predictions of turbine inlet temperature, specific fuel consumption, and power output for real-time decision support [5].

4.3.3. Robustness and Uncertainty Layer

To strengthen reliability under sparse or rare-event conditions, a dedicated layer addresses data augmentation and uncertainty quantification. Generative models such as GANs, VAEs, and RNNs [8] expand training datasets, while physics-informed data generation and model discovery techniques (e.g., PySINDy [24], sparse PDE learning [30], and SINDy [69]) extract interpretable governing equations for unseen scenarios. Uncertainty-aware approaches—including Bayesian PINNs [70] and conformal prediction—attach confidence bounds to predictions, improving operator trust and providing actionable confidence levels for decision-making.

4.3.4. Optimization and Intelligence Layer

At the highest level, embedded optimization and adaptive control modules enable predictive maintenance, virtual sensing, and fleet-wide decision-making. Low-latency optimization methods such as PSO, GA, and quadratic programming integrate with the digital twin workflow to recommend constraint-aware set-point adjustments and maintenance actions. As demonstrated in [5], these optimization loops can recover lost performance during alarm conditions while meeting industrial requirements for safety and responsiveness.

These integrated layers bridge design-phase simulations with real-time operational intelligence, creating a framework that is interpretable, scalable, and physics-consistent. By accurately capturing nonlinear behaviors and degradation mechanisms, the proposed architecture is particularly well suited to gas turbines, where high-fidelity physics and robust adaptability are essential for dependable operation. Overcoming persistent barriers—especially data scarcity, integration complexity, and computational cost—will require coordinated efforts across research communities, industrial partners, and standardization bodies.

The proposed framework aligns with emerging industrial implementations of intelligent digital twins, demonstrating both scalability and practical relevance. The EPRI turbine digital twin [56], designed for operator-focused integrated diagnostics, exemplifies how hybrid AI can be embedded into utility-scale platforms to enhance decision support. Similarly, the GE Vernova case [57] and the Siemens ATOM platform [58] illustrate fleet-wide deployment of intelligent digital twins, where cloud-enabled architectures and embedded AI modules deliver predictive maintenance, lifecycle optimization, and coordinated decision-making. These case studies validate the layered hybrid AI approach and highlight the pathway toward widespread adoption of intelligent digital twins in the gas turbine industry.

5. Conclusions

This review introduced a classification and maturity framework for hybrid AI approaches in gas turbine intelligent digital twins. The analysis showed that no single method is universally superior. Each category including ANN-augmented thermodynamic models, physics-integrated operational architectures, physics-constrained neural networks with CFD surrogates, and generative/model discovery approaches, offers distinct trade-offs in data needs, interpretability, real-time suitability, and deployment complexity. Hybrid AI methods consistently outperform purely data-driven or purely physics-based approaches by improving diagnostic accuracy, computational efficiency, and resilience under degraded or uncertain conditions. Future progress will depend on standardized benchmarks, open datasets, secure integration with SCADA systems, and uncertainty-aware techniques such as Bayesian PINNs and physics-constrained generative augmentation to strengthen rare-event readiness. Overall, physics-informed hybrid AI provides a robust foundation for next-generation intelligent digital twins, enabling interpretable real-time monitoring and supporting the energy sector’s transition to cleaner, more flexible, and resilient systems.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, H.F.; review and editing, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| CFD |

Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CHP |

Combined Heat and Power |

| CMS |

Condition Monitoring System |

| FNO |

Fourier Neural Operator |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| GAN |

Generative Adversarial Network |

| GNN |

Graph Neural Network |

| GPA |

Gas Path Analysis |

| LNN |

Lagrangian Neural Network |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| NPSS |

Numerical Propulsion System Simulation |

| NSFnet |

Navier–Stokes Flow Network |

| PcNN |

Physics-Constrained Neural Network |

| PDE |

Partial Differential Equation |

| PINN |

Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| PIML |

Physics-Informed Machine Learning |

| PySINDy |

Python implementation of Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics |

| QP |

Quadratic Programming |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| RUL |

Remaining Useful Life |

| SCADA |

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SFC |

Specific Fuel Consumption |

| SINDy |

Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics |

| TIT |

Turbine Inlet Temperature |

| VAE |

Variational Autoencoder |

References

- Farhat, H.; Salvini, C. Novel Gas Turbine Challenges to Support the Clean Energy Transition. Energies 2022, 15, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, H. Models for Gas-Turbine Performance Deterioration Predictions for Optimum Operation Management. PhD Thesis, Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Genrup, M. Theory for Turbomachinery Degradation and Monitoring Tools. Licentiate Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ge, X.; Wei, M. Physics Informed Machine Learning Approach for Performance Degradation Monitoring of Gas Turbine. PHM Soc. Asia-Pacific Conf. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.T.; Habibullah, A.; Ng, E.Y.K. Towards a Digital Twin for Gas Turbines: Thermodynamic Modeling, Critical Parameter Estimation, and Performance Optimization Using PINN and PSO. Energies 2025, 18, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Sui, F.; Liu, A.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Song, B.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S.C.-Y.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twin-driven product design framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3935–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Fink, O.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y. Controlled physics-informed data generation for deep learning-based remaining useful life prediction under unseen operation conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschler, B.; Braun, D.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. Transfer learning as an enabler of the intelligent digital twin. Procedia CIRP 2021, 100, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, M.; Palmé, T. Application of artificial neural networks to the condition monitoring and diagnosis of a combined heat and power plant. Energy 2010, 35, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, M.; Graziano, A.; Badora, M.; Di Stazio, A.; Bellani, L.; Compare, M.; Zio, E. A physics-informed machine learning framework for predictive maintenance applied to turbomachinery assets. J. Glob. Power Propuls. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentaye, A.D.; Gilani, S.I.U.-H.; Baheta, A.T.; Ghani, S.C.; Alias, A.; Mamat, R.; Rahman, M. Gas turbine gas path diagnostics: A review. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 74, 00005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaji, S.O.; Singh, R. Advanced Gas-Path Fault Diagnostics for Stationary Gas Turbines. PhD Thesis, Cranfield University, Cranfield, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cerri, G.; Borghetti, S.; Salvini, C. Models for Simulation and Diagnosis of Energy Plant Components. ASME 2006 Power Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 711–720.

- Cerri, G.; Borghetti, S.; Salvini, C. Inverse Methodologies for Actual Status Recognition of Gas Turbine Components. ASME 2005 Power Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 299–306.

- Panov, V. Model-based control and diagnostic techniques for operational improvements of gas turbine engines. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Turbomachinery—Fluid Dynamics & Thermodynamics (ETC10), Lappeenranta, Finland, 15–19 April 2013; Paper No. ETC2013-123. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Cola, V.S.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific Machine Learning Through Physics–Informed Neural Networks: Where we are and What’s Next. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, H.; Chen, X.; Menhaj, M.B.; Sainudiin, R. Artificial Neural Network–Based System Identification for a Single-Shaft Gas Turbine. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2013, 135, 092601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.A.; Kulkarni, C.; Goebel, K.; Fink, O. Fusing physics-based and deep learning models for prognostics. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez-Zárate, J.; Trujillo, L.; de Lara, S.; Castelli, M.; Z-Flores, E.; Muñoz, L.; Popovič, A. Automatic modeling of a gas turbine using genetic programming: An experimental study. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 50, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophiya, A.A.; Maleki, S.; Bruni, G.; Krishnababu, S.K. Physics-informed neural networks for industrial gas turbines: Recent trends, advancements and challenges. arXiv arXiv:2506.19503, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Towards an Automated Biodiversity Modelling Process for Forest Animals using Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles. THE 11TH INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP ON SIMULATION FOR ENERGY, SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT & ENVIRONMENT. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Cerri, G.; Monacchia, S.; Seyedan, B. Optimum Load Allocation in Cogeneration Gas-Steam Combined Plants. ASME 1999 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- de Silva, B.; Champion, K.; Quade, M.; Loiseau, J.-C.; Kutz, J.; Brunton, S. PySINDy: A Python package for the sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems from data. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Cai, S.; Li, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. NSFnets (Navier–Stokes flow nets). arXiv arXiv:2003.06496, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Al Sayed, N.; Hamdouni, A.; Liberge, E.; Razafindralandy, D. The Symmetry Group of the Non-Isothermal Navier–Stokes Equations and Turbulence Modelling. Symmetry 2010, 2, 848–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.T.; Bui, T.Q.; Chijiwa, N.; Hirose, S. A new implicit gradient damage model based on energy limiter for brittle fracture: Theory and numerical investigation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kovachki, N.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Liu, B.; Stuart, A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Anandkumar, A. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); Virtual Conference, 3–7 May 2021; arXiv: .08895, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi, E.; Zhang, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. Variational physics-informed neural networks for solving partial differential equations. arXiv arXiv:1912.00873, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, H. Learning partial differential equations via data discovery and sparse optimization. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 473, 20160446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirignano, J.; Spiliopoulos, K. DGM: A deep learning algorithm for solving partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 375, 1339–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, M.; Greydanus, S.; Battaglia, P.; Spergel, D.; Ho, S. Lagrangian neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) Workshop, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020; arXiv: .04630, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Pfaff, T.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J.; Battaglia, P. Learning to simulate complex physics with graph networks. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 12–18 July 2020; arXiv: .09405, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, A.; Heess, N.; Springenberg, J.T.; Merel, J.; Riedmiller, M.; Hadsell, R.; Battaglia, P.W. Graph networks as learnable physics engines for inference and control. arXiv arXiv:1806.01242, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zahr, M.J.; Wang, J.-X. Physics-informed graph neural Galerkin networks: A unified framework for solving PDE-governed forward and inverse problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, A.; Baiges, J.; Codina, R. Finite element approximation of wave problems with correcting terms based on training artificial neural networks with fine solutions. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Yao, W. A novel graph modeling method for GNN-based hypersonic aircraft flow field reconstruction. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobeiry, N.; Humfeld, K.D. A physics-informed machine learning approach for solving heat transfer equation in advanced manufacturing and engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-X.; Wu, Z.; Zhong, M.-L.; Yao, S. Data-driven modeling of a forced convection system for super-real-time transient thermal performance prediction. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, S.; Furbo, S. Thermal stratification in vertical mantle heat-exchangers with application to solar domestic hot-water systems. Appl. Energy 2003, 78, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, A.; Fernandez-Ramirez, K.I.; Aranda-Sanchez, J.I. A study of chaotic searching paths for their application in an ultrasonic scanner. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 74, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawasam, L.; Jayasena, A.; Afnan, M.; Ranasinghe, R.; Wijewardane, M. Waste heat recovery from thermo-electric generators (TEGs). Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, R.; Ogaji, S.; Singh, R.; Probert, S. Gas-turbine diagnostics using artificial neural-networks for a high bypass ratio military turbofan engine. Appl. Energy 2004, 78, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulich, M.; Goinis, G.; Voß, C. Data-Driven AI Model for Turbomachinery Compressor Aerodynamics Enabling Rapid Approximation of 3D Flow Solutions. Aerospace 2024, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, G.; Chennaoui, L.; Giovannelli, A.; Salvini, C. Gas Path Analysis and Gas Turbine Re-Mapping. ASME 2011 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, CanadaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 375–383.

- Capata, R. An artificial neural network-based diagnostic methodology for gas turbine path analysis—part II: case study. Energy, Ecol. Environ. 2016, 1, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tan, R.; Peng, Q.; Wang, F.; Shao, P.; Gao, Z. A holistic method of complex product development based on a neural network-aided technological evolution system. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2021, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreslassie, B.H.; Guillén-Gosálbez, G.; Jiménez, L.; Boer, D. Design of environmentally conscious absorption cooling systems via multi-objective optimization and life cycle assessment. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, Y.; Yee, K.; Maulik, R.; Kang, N. Data-driven physics-informed neural networks: A digital twin perspective. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.B.; Mansouri, M.; Fentaye, A.D.; Ahsan, S.; Kyprianidis, K. An Artificial Neural Network-Based Fault Diagnostics Approach for Hydrogen-Fueled Micro Gas Turbines. Energies 2024, 17, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Yao, W.; Zheng, X.; Wang, N.; Sun, J. Implicitly physics-informed multi-fidelity physical field data fusion method based on Taylor modal decomposition. Adv. Eng. Informatics 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaji, S.; Sampath, S.; Singh, R.; Probert, D. Novel approach for improving power-plant availability using advanced engine diagnostics. Appl. Energy 2002, 72, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghuge, S.; Dohale, V.; Akarte, M. Spare part segmentation for additive manufacturing – A framework. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Bodyanskiy, Y.V.; Tyshchenko, O.K.; Boiko, O.O. A neuro-fuzzy Kohonen network for data stream possibilistic clustering and its online self-learning procedure. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 68, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Perullo, C.A.; Milton, J.; Whitacre, R.; Jackson, C.; Griffin, C.; Noble, D.; Boche, L.; Seachman, S.; Angello, L.; et al. The EPRI Gas Turbine Digital Twin – a Platform for Operator Focused Integrated Diagnostics and Performance Forecasting. ASME Turbo Expo 2021: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- GE Vernova. How CPV used digital twin to increase power output and reduce costs. GE Vernova—Customer Stories, 2023. Available online: https://www.gevernova.com/software/customer-stories/how-cpv-used-digital-twin-to-increase-power-output-reduce-costs (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- DecisionLab Ltd. ATOM digital twin of Siemens gas turbine fleet operations. AnyLogic—Case Studies, 2023. Available online: https://www.anylogic.com/resources/case-studies/atom-digital-twin-of-siemens-gas-turbine-fleet-operations/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Soltani, M.; Akbari, G.; Montazerin, N. Trade-off between reconstruction accuracy and physical validity in modeling turbomachinery particle image velocimetry data by physics-informed convolutional neural networks. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, K.; Kumar, M.S.; Yuvaraj, N. Multi objective taguchi–grey relational analysis and krill herd algorithm approaches to investigate the parametric optimization in abrasive water jet drilling of stainless steel. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, G.; Maleki, S.; Krishnababu, S.K. Deep learning modeling of manufacturing and build variations on multistage axial compressors aerodynamics. Data-Centric Eng. 2025, 6, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahan, M.; Tsoutsanis, E.; Muhammad, M.; Karim, Z.A. Performance-based health monitoring, diagnostics and prognostics for condition-based maintenance of gas turbines: A review. Appl. Energy 2017, 198, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollinger, J.P. Status of Silicon Nitride Component Fabrication Processes, Material Properties, and Applications. ASME 1997 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exhibition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Anagnostopoulos, S.J.; Toscano, J.D.; Stergiopulos, N.; Karniadakis, G.E. Residual-based attention in physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jin, P.; Pang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. Learning nonlinear operators via DeepONet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishi, S. Assessing the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Product Design Towards Circularity. PhD Dissertation, Lappeenranta-Lahti University of Technology, Lappeenranta/Lahti, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hadian, M.; Ebrahimi Saryazdi, S.M.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Babaei, M. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Modeling, Control, and Fault Diagnosis. In Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Process Systems Engineering; Zamarripa, M., Espuña, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, C.; Jiang, H.; Luo, X. AI-based methodology of integrating affective design, engineering, and marketing for defining design specifications of new products. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2016, 47, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Proctor, J.L.; Kutz, J.N. Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 3932–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chung, W.T.; Akoush, B.; Ihme, M. A Review of Physics-Informed Machine Learning in Fluid Mechanics. Energies 2023, 16, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaria, V.; Fentaye, A.D.; Kyprianidis, K. Bayesian Information Fusion for Gas Turbines Diagnostics and Prognostics. ASME Turbo Expo 2023: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Suarez, G.; Özkaya, E.; Gauger, N.R.; Steiner, H.-J.; Schäfer, M.; Naumann, D. Nonlinear Surrogate Model Design for Aerodynamic Dataset Generation Based on Artificial Neural Networks. Aerospace 2024, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalani, G.; Agarwal, S.; Bertrand, X.; Tost, F.; Bauerheim, M.; Morlier, J. Neural fields for rapid aircraft aerodynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roznowicz, D.; Stabile, G.; Demo, N.; Fransos, D.; Rozza, G. Large-scale graph-machine-learning surrogate models for 3D-flowfield prediction in external aerodynamics. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 2024, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalani, R.; Fesquet, J.; Bertrand, M.; Tost, D.; Morlier, J. Towards scalable surrogate models based on neural fields for large-scale aerodynamic simulations. arXiv arXiv:2505.14704, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).