Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

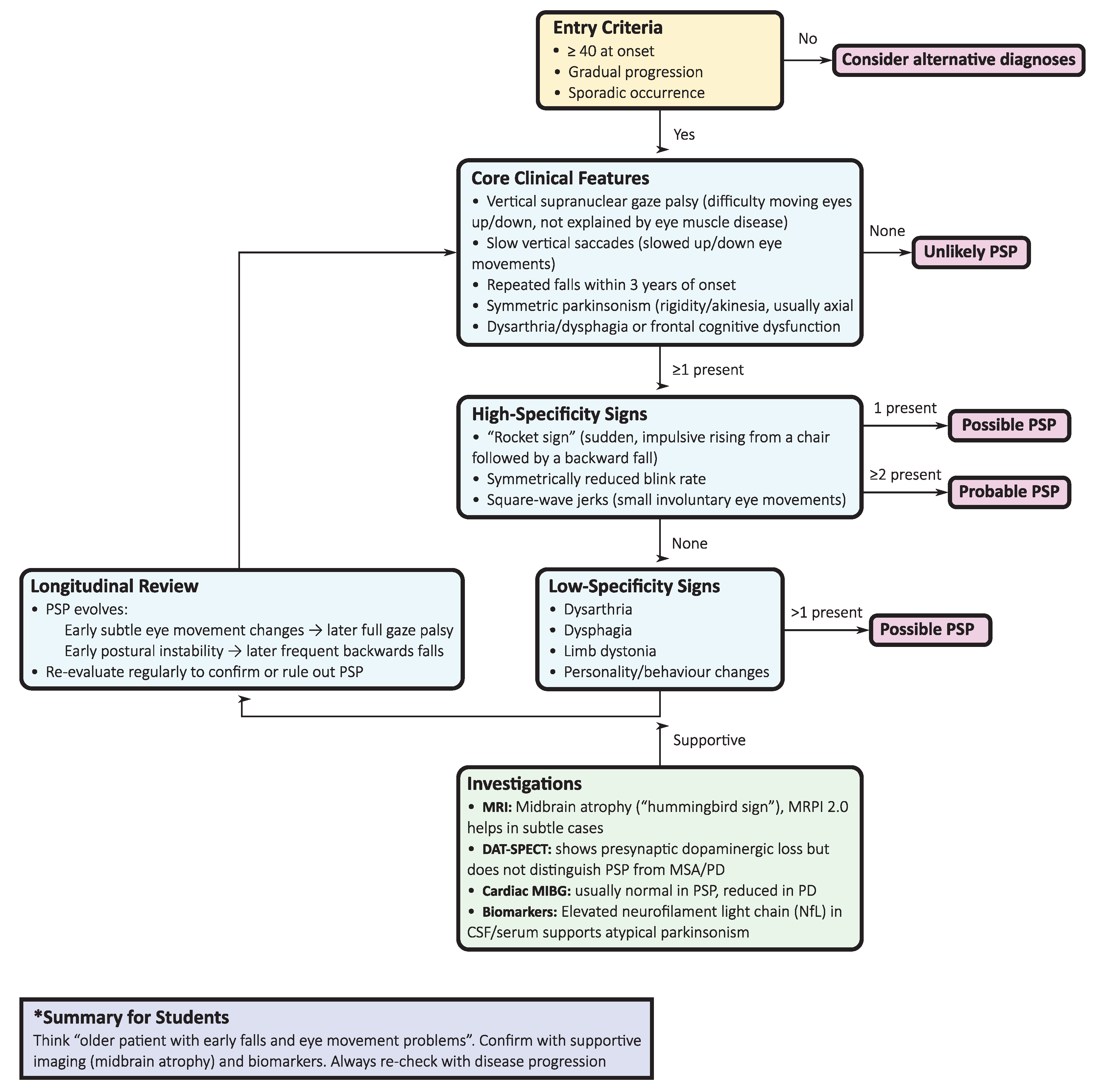

2. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)

2.1. Etiology and genetics

2.2. Diagnostic approach

- Initial clinical evaluation: Symmetric, axial-predominant parkinsonism with early postural instability, vertical gaze impairment, dysarthria/dysphagia, and dysexecutive profile should raise early suspicion of PSP, contrasting with the asymmetric onset, rest tremor, and levodopa responsiveness typical of PD.

- Ocular motor testing: Slowing of vertical saccades progressing to gaze palsy, together with square-wave jerks, is highly specific; video-oculography offers objective quantification.

- Phenotype classification: Applying the 2017 MDS-PSP criteria allows early recognition not only of PSP-RS but also of variant phenotypes (e.g., PSP-parkinsonism, PSP with predominant gait freezing, PSP-CBS, PSP-FTD).

- Neuroimaging: Midbrain atrophy with pontine sparing (“hummingbird sign”) is supportive, but MRPI 2.0, computed via automated tools, provides superior discrimination, especially between PSP-parkinsonism and PD/MSA.

- Supportive imaging: DAT-SPECT confirms presynaptic nigrostriatal degeneration but lacks nosological resolution. In contrast, cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy is typically normal in PSP but reduced in Lewy body disorders, supporting differential diagnosis.

- Fluid biomarkers: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or plasma NfL levels are consistently higher in PSP than in PD, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values greater than 0.90 for PD compared to atypical parkinsonism. Although not diagnostic in isolation, NfL has prognostic and triage value, particularly when combined with MRI measures.

- Longitudinal reassessment: Diagnostic certainty increases as the disease evolves. Repeated clinical, ocular motor, and imaging assessments capture the progression from subtle ocular motor slowing to frank gaze palsy, thereby consolidating diagnostic accuracy.

2.3. Phenotypic spectrum

2.4. Investigations and biomarkers

2.4.1. MRI

2.4.2. Tau PET

2.4.3. Dopaminergic imaging and autonomic tracers

2.4.4. Fluid biomarkers

2.5. Pathology

2.6. Treatment and management

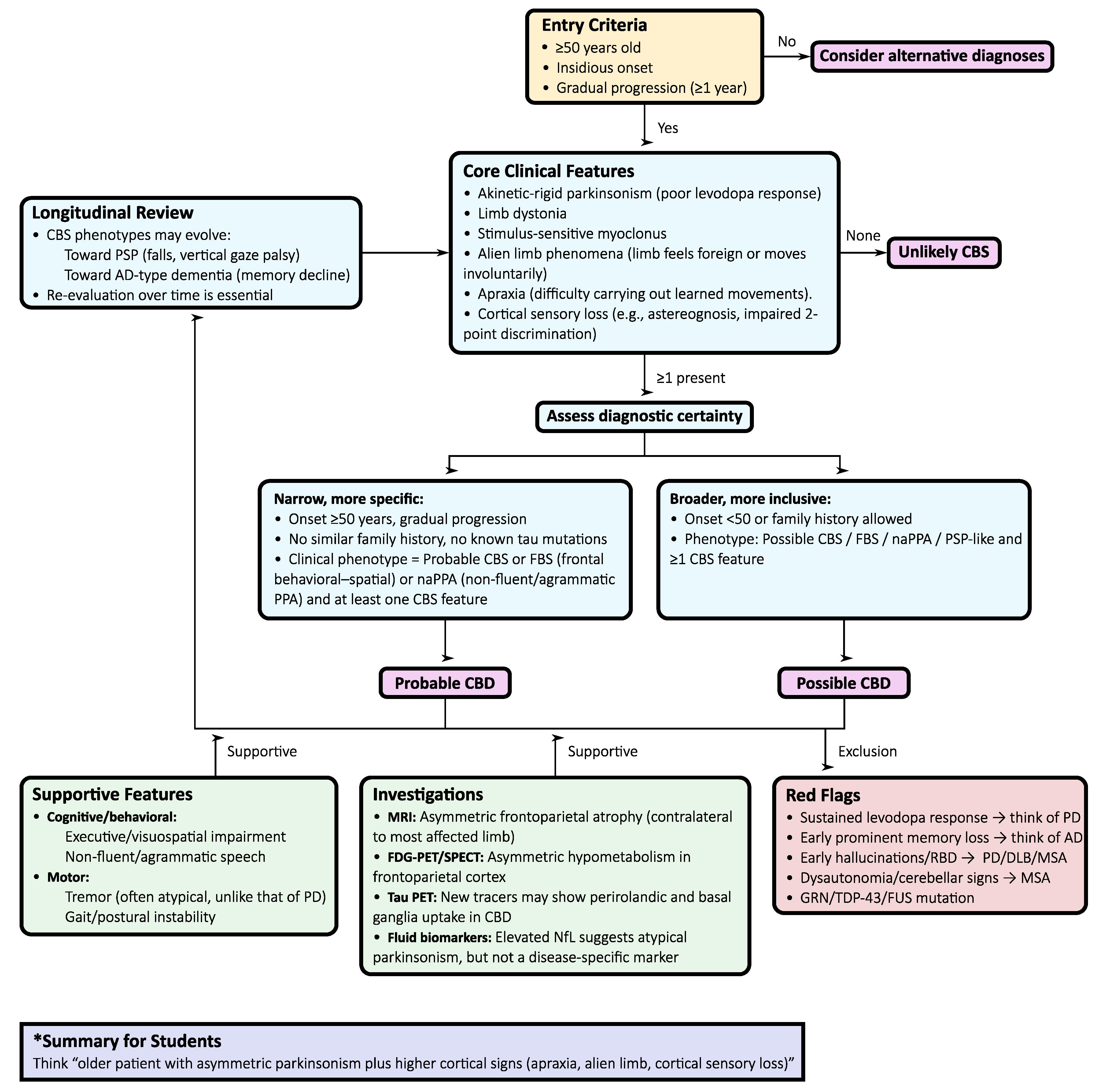

3. Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD)

3.1. Etiology and genetics

3.2. Diagnostic approach

- Initial presentation: Asymmetric, levodopa-resistant parkinsonism with cortical signs such as apraxia, cortical sensory loss, or alien limb phenomena is the core entry point for CBS and the most common clinical phenotype of CBD.

- Application of the Armstrong criteria: Differentiating between probable and possible CBD provides a standardized clinical framework, although with limited sensitivity and specificity in practice.

- Neuropsychological evaluation: Formal testing of executive, visuospatial, and language domains is crucial. A non-fluent/agrammatic language profile supports CBD, while early episodic memory loss points toward AD-related CBS.

- MRI assessment: Characteristically reveals asymmetric frontoparietal atrophy contralateral to the most affected limb, sometimes with basal ganglia atrophy. Although not specific, it strengthens the clinico-anatomical correlation.

- Functional imaging, such as [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) or perfusion SPECT, typically demonstrates asymmetric hypometabolism or hypoperfusion in the frontoparietal cortex and basal ganglia, with relative sparing of the midbrain and cerebellum. These features help separate CBD from PSP/MSA but overlap with AD-related CBS.

- Tau PET: New-generation tracers ([18F]PI-2620, [18F]florzolotau) show asymmetric uptake in perirolandic and basal ganglia regions in pathologically confirmed CBD, complementing MRI for early detection of 4R tau pathology.

- Fluid biomarkers: Elevated NfL is a common finding and correlates with disease progression. Combined with imaging and neuropsychological testing, it improves discrimination between CBS due to CBD and CBS from AD or other pathologies.

- Longitudinal reassessment: Phenotypes may evolve toward PSP-like Richardson’s syndrome, behavioral variant FTD, non-fluent aphasia, or posterior cortical atrophy. Ongoing clinical review is essential, as early labels often shift with disease progression.

3.3. Phenotypic spectrum

3.4. Investigations and biomarkers

3.4.1. MRI

3.4.2. FDG-PET and perfusion SPECT

3.4.3. Tau PET

3.4.4. Fluid biomarkers

3.5. Pathology

3.6. Treatment and management

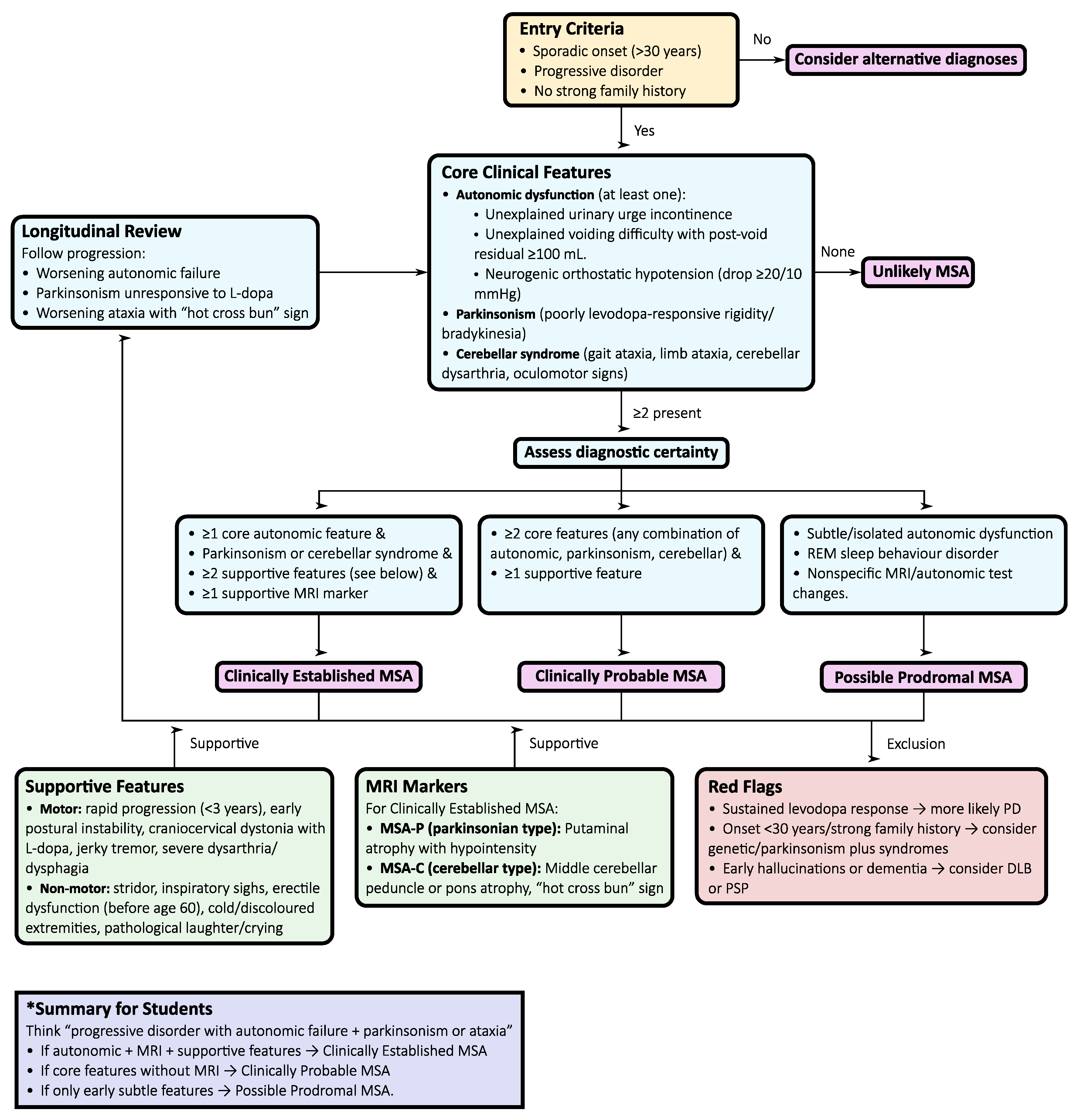

4. Multiple System Atrophy (MSA)

4.1. Etiology and genetics

4.2. Diagnostic approach

- Initial presentation: Suspect MSA when symmetric parkinsonism (MSA-P) or cerebellar syndrome (MSA-C) co-occurs with autonomic dysfunction. Autonomic features frequently precede motor involvement and are diagnostically pivotal.

- Autonomic assessment: Comprehensive evaluation—including tilt-table testing, Valsalva maneuver, and urodynamics—documents cardiovascular and urogenital dysfunction, confirming autonomic failure as a diagnostic cornerstone.

- Motor examination: Poor or transient levodopa response, jerky cortical myoclonus, or focal dystonia support MSA over PD, in which sustained levodopa benefit and classic rest tremor are typical.

- MRI assessment: Characteristic signs include the “hot cross bun” sign in the pons, putaminal atrophy or hypointensity, and middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP) hyperintensity/atrophy. Quantitative morphometry of MCP width and pons-to-MCP ratios enhances early diagnostic accuracy.

- Dopaminergic imaging: DAT-SPECT confirms presynaptic dopaminergic loss but does not differentiate MSA from PD or PSP, serving only to establish neurodegeneration.

- Cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy: Normal uptake in MSA versus markedly reduced uptake in PD/dementia with Lewy bodies helps distinguish between synucleinopathies.

- FDG-PET: Hypometabolism in the putamen, pons, and cerebellum, with cortical sparing, supports MSA and helps separate it from PSP and PD.

- Pathology: The definitive diagnosis rests on the demonstration of α–synuclein–positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions in oligodendrocytes, but this is typically confirmed post-mortem.

- Longitudinal reassessment: As motor, autonomic, and cerebellar features evolve, ongoing clinical review is critical to ensure accurate classification, prognosis, and trial eligibility.

4.3. Phenotypic spectrum

4.4. Investigations and biomarkers

4.4.1. MRI

4.4.2. Functional imaging

4.4.3. Autonomic testing

4.4.4. Fluid and molecular biomarkers

4.5. Pathology

4.6. Treatment and management

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α-syn | Alpha-synuclein |

| 123I-IBZM | [123I]Iodobenzamide |

| 123I-MIBG | [123I]Metaiodobenzylguanidine |

| 4R tau | 4-repeat tauopathy |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APD | Atypical parkinsonian disorder |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CBS | Corticobasal syndrome |

| CBD | Corticobasal degeneration |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DAT-SPECT | Dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography |

| FDG-PET | [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| FTLD | Frontotemporal lobar degeneration |

| FTLD-TDP | FTLD with TPD-43-immunoreactive pathology |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| MCP | Middle cerebellar peduncle |

| MDS | Movement Disorder Society |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRPI 2.0 | Magnetic Resonance Parkinsonism Index 2.0 |

| MSA | Multiple system atrophy |

| MSA-C | Multiple system atrophy, cerebellar phenotype |

| MSA-P | Multiple system atrophy, parkinsonian phenotype |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PSP | Progressive supranuclear palsy |

| PSP-CBS | PSP with corticobasal syndrome |

| PSP-FTD | PSP with frontotemporal dementia |

| PSP-P | PSP-parkinsonism |

| PSP-PGF | PSP with predominant gait freezing |

| PSP-RS | PSP–Richardson’s syndrome |

References

- Hoglinger, G.U.; Respondek, G.; Stamelou, M.; Kurz, C.; Josephs, K.A.; Lang, A.E.; Mollenhauer, B.; Muller, U.; Nilsson, C.; Whitwell, J.L., et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017, 32, 853-864. [CrossRef]

- Wenning, G.K.; Stankovic, I.; Vignatelli, L.; Fanciulli, A.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Seppi, K.; Palma, J.A.; Meissner, W.G.; Krismer, F.; Berg, D., et al. The Movement Disorder Society Criteria for the Diagnosis of Multiple System Atrophy. Mov Disord 2022, 37, 1131-1148. [CrossRef]

- Iankova, V.; Respondek, G.; Saranza, G.; Painous, C.; Camara, A.; Compta, Y.; Aiba, I.; Balint, B.; Giagkou, N.; Josephs, K.A., et al. Video-tutorial for the Movement Disorder Society criteria for progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020, 78, 200-203. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Le Heron, C.; Anderson, T. Corticobasal syndrome: a practical guide. Practical Neurology 2021, 21, 276-285. [CrossRef]

- Nouh, C.D.; Younes, K. Diagnosis and Management of Progressive Corticobasal Syndrome. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2024, 26, 319-338. [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Robles, E.; de Celis Alonso, B.; Cantillo-Negrete, J.; Carino-Escobar, R.I.; Arias-Carrion, O. Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Early Diagnosis and Monitoring of Movement Disorders. Brain Sci 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Quattrone, A.; Bianco, M.G.; Antonini, A.; Vaillancourt, D.E.; Seppi, K.; Ceravolo, R.; Strafella, A.P.; Tedeschi, G.; Tessitore, A.; Cilia, R., et al. Development and Validation of Automated Magnetic Resonance Parkinsonism Index 2.0 to Distinguish Progressive Supranuclear Palsy-Parkinsonism From Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord 2022, 37, 1272-1281. [CrossRef]

- Quattrone, A.; Morelli, M.; Nigro, S.; Quattrone, A.; Vescio, B.; Arabia, G.; Nicoletti, G.; Nistico, R.; Salsone, M.; Novellino, F., et al. A new MR imaging index for differentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy-parkinsonism from Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018, 54, 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Catalan, M.; Dore, F.; Polverino, P.; Bertolotti, C.; Sartori, A.; Antonutti, L.; Cucca, A.; Furlanis, G.; Capitanio, S.; Manganotti, P. (123)I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine Myocardial Scintigraphy in Discriminating Degenerative Parkinsonisms. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8, 717-724. [CrossRef]

- Demiri, S.; Veltsista, D.; Siokas, V.; Spiliopoulos, K.C.; Tsika, A.; Stamati, P.; Chroni, E.; Dardiotis, E.; Liampas, I. Neurofilament Light Chain in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood in Multiple System Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrion, O.; Guerra-Crespo, M.; Padilla-Godinez, F.J.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Manjarrez, E. alpha-Synuclein Pathology in Synucleinopathies: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Challenges. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Gomes, B.; Farris, C.M.; Ma, Y.; Concha-Marambio, L.; Lebovitz, R.; Nellgard, B.; Dalla, K.; Constantinescu, J.; Constantinescu, R.; Gobom, J., et al. alpha-Synuclein seed amplification assay as a diagnostic tool for parkinsonian disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2023, 117, 105807. [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, A.; Konitsiotis, S.; Sioka, C. Differentiating Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Corticobasal Syndrome: Insights from Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers-A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61. [CrossRef]

- Gogola, A.; Lopresti, B.J.; Minhas, D.S.; Lopez, O.; Cohen, A.; Villemagne, V.L. Tau Imaging: Use and Implementation in New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Paradigms for Alzheimer's Disease. Geriatrics (Basel) 2025, 10. [CrossRef]

- Mena, A.M.; Strafella, A.P. Imaging pathological tau in atypical parkinsonisms: A review. Clin Park Relat Disord 2022, 7, 100155. [CrossRef]

- Stamelou, M.; Respondek, G.; Giagkou, N.; Whitwell, J.L.; Kovacs, G.G.; Hoglinger, G.U. Evolving concepts in progressive supranuclear palsy and other 4-repeat tauopathies. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 601-620. [CrossRef]

- Barer, Y.; Chodick, G.; Cohen, R.; Grabarnik-John, M.; Ye, X.; Zamudio, J.; Gurevich, T. Epidemiology of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Real World Data from the Second Largest Health Plan in Israel. Brain Sci 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.; Trepel, D.; Lynch, T.; Walsh, R.; O'Dowd, S. The prevalence and incidence of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 4451-4465. [CrossRef]

- Street, D.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Malpetti, M.; Jones, P.S.; Passamonti, L.; Ghosh, B.C.; Rittman, T.; Coyle-Gilchrist, I.T.; Allinson, K.; Dawson, C.E., et al. Structural correlates of survival in progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2023, 116, 105866. [CrossRef]

- Nysetvold, E.; Lopez, L.N.; Cogell, A.N.; Fryk, H.; Pace, N.D.; Taylor, S.S.; Rhoden, J.; Nichols, C.A.; Pillas, D.; Klein, A., et al. Progressive Supranuclear palsy (PSP) disease progression, management, and healthcare resource utilization: a retrospective observational study in the US and Canada. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 215. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Chen, Z.; Won, H.; Huang, A.Y.; Lowe, J.K.; Wojta, K.; Yokoyama, J.S.; Bensimon, G.; Leigh, P.N.; Payan, C., et al. Joint genome-wide association study of progressive supranuclear palsy identifies novel susceptibility loci and genetic correlation to neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 41. [CrossRef]

- Farrell, K.; Humphrey, J.; Chang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Leung, Y.Y.; Kuksa, P.P.; Patil, V.; Lee, W.P.; Kuzma, A.B.; Valladares, O., et al. Genetic, transcriptomic, histological, and biochemical analysis of progressive supranuclear palsy implicates glial activation and novel risk genes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7880. [CrossRef]

- Hoglinger, G.U.; Melhem, N.M.; Dickson, D.W.; Sleiman, P.M.; Wang, L.S.; Klei, L.; Rademakers, R.; de Silva, R.; Litvan, I.; Riley, D.E., et al. Identification of common variants influencing risk of the tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 699-705. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Contreras, M.Y.; Kouri, N.; Cook, C.N.; Serie, D.J.; Heckman, M.G.; Finch, N.A.; Caselli, R.J.; Uitti, R.J.; Wszolek, Z.K.; Graff-Radford, N., et al. Replication of progressive supranuclear palsy genome-wide association study identifies SLCO1A2 and DUSP10 as new susceptibility loci. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 37. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chang, T.S.; Dombroski, B.A.; Cheng, P.L.; Patil, V.; Valiente-Banuet, L.; Farrell, K.; McLean, C.; Molina-Porcel, L.; Rajput, A., et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis reveals new susceptibility loci and structural variants associated with progressive supranuclear palsy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 61. [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, P.W.; Fumi, R.; Theilmann Jensen, M.; Jabbari, E.; Warner, T.T.; Revesz, T.; Morris, H.R.; Rohrer, J.D.; Jaunmuktane, Z. MAPT-Associated Familial Progressive Supranuclear Palsy with Typical Corticobasal Degeneration Neuropathology: A Clinicopathological Report. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2023, 10, 691-694. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Lu, J.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Liang, X.N.; Jiao, F.Y.; Ge, J.J.; Wu, P.; Li, G.; Shen, B.; Wu, B., et al. (18)F-Florzolotau PET imaging captures the distribution patterns and regional vulnerability of tau pathology in progressive supranuclear palsy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 1395-1405. [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.C.; Roemer, S.; Petrucelli, L.; Dickson, D.W. Cellular and pathological heterogeneity of primary tauopathies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 57. [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa-Escamilla, E.; Velasco-Martinez, R.A.; Adalid-Peralta, L. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Syndrome: An Overview. IBRO Neurosci Rep 2024, 16, 598-608. [CrossRef]

- Chovatiya, H.; Pillai, K.; Reddy, C.; Thalakkattu, A.; Avarachan, A.; Chacko, M.; Kishore, A. Video-Oculography for Enhancing the Diagnostic Accuracy of Early Oculomotor Dysfunction in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. J. Mov. Disord. 2025, 18, 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Facchin, A.; Buonocore, J.; Crasa, M.; Quattrone, A.; Quattrone, A. Systematic assessment of square-wave jerks in progressive supranuclear palsy: a video-oculographic study. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6639-6646. [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, J.; Behler, A.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Ludolph, A.C.; Pinkhardt, E.H.; Kassubek, J. Diagnostic value of video-oculography in progressive supranuclear palsy: a controlled study in 100 patients. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 3467-3475. [CrossRef]

- Brendel, M.; Barthel, H.; van Eimeren, T.; Marek, K.; Beyer, L.; Song, M.; Palleis, C.; Gehmeyr, M.; Fietzek, U.; Respondek, G., et al. Assessment of 18F-PI-2620 as a Biomarker in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1408-1419. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lu, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Clement, C.; Lopes, L.; Brendel, M.; Rominger, A.; Yen, T.C., et al. Uncovering distinct progression patterns of tau deposition in progressive supranuclear palsy using [(18)F]Florzolotau PET imaging and subtype/stage inference algorithm. EBioMedicine 2023, 97, 104835. [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, K.; Barthel, H.; Brendel, M.; Scherlach, C.; Hoffmann, K.T.; Rauchmann, B.S.; Rullmann, M.; Marek, K.; Villemagne, V.L.; Rumpf, J.J., et al. (18)F-PI-2620 Tau PET Improves the Imaging Diagnosis of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 1754-1760. [CrossRef]

- Wallert, E.D.; van de Giessen, E.; Knol, R.J.J.; Beudel, M.; de Bie, R.M.A.; Booij, J. Imaging Dopaminergic Neurotransmission in Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 63, 27S-32S. [CrossRef]

- Ebina, J.; Mizumura, S.; Shibukawa, M.; Morioka, H.; Nagasawa, J.; Yanagihashi, M.; Hirayama, T.; Ishii, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Inaba, A., et al. Comparison of MIBG uptake in the major salivary glands between Lewy body disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Clin Park Relat Disord 2024, 11, 100287. [CrossRef]

- Pitton Rissardo, J.; Fornari Caprara, A.L. Cardiac 123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) Scintigraphy in Parkinson's Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, S.; Rossi, M.; Giannini, G.; Mammana, A.; Polischi, B.; Sambati, L.; Mastrangelo, A.; Magliocchetti, F.; Cortelli, P.; Capellari, S., et al. Head-to-head comparison of four cerebrospinal fluid and three plasma neurofilament light chain assays in Parkinsonism. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2025, 11, 98. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; Li, J.Q.; Hou, X.H.; Ou, Y.N.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. Neurofilament Light Chain in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood as a Biomarker for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 1353-1361. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Cai, T.; He, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative susceptibility mapping and blood neurofilament light chain differentiate between parkinsonian disorders. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 909552. [CrossRef]

- Apetauerova, D.; Scala, S.A.; Hamill, R.W.; Simon, D.K.; Pathak, S.; Ruthazer, R.; Standaert, D.G.; Yacoubian, T.A. CoQ10 in progressive supranuclear palsy: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016, 3, e266. [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E.; Litvan, I.; Hoglinger, G.U.; Burn, D.; Lees, A.; Andres, M.V.; Gomez-Carrillo, B.; Leon, T.; Del Ser, T.; Investigators, T. A phase 2 trial of the GSK-3 inhibitor tideglusib in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2014, 29, 470-478. [CrossRef]

- Hoglinger, G.U.; Litvan, I.; Mendonca, N.; Wang, D.; Zheng, H.; Rendenbach-Mueller, B.; Lon, H.K.; Jin, Z.; Fisseha, N.; Budur, K., et al. Safety and efficacy of tilavonemab in progressive supranuclear palsy: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 182-192. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.B.; Holland, N.; Rittman, T. Progressive supranuclear palsy: diagnosis and management. Pract Neurol 2021, 21, 376-383. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; Bak, T.H.; Bhatia, K.P.; Borroni, B.; Boxer, A.L.; Dickson, D.W.; Grossman, M.; Hallett, M., et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 2013, 80, 496-503. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Mayo, M.C.; Wilson, S.M.; Seeley, W.W.; DeArmond, S.J.; Huang, E.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Growdon, M.E.; Jang, J.Y., et al. Clinicopathological correlations in corticobasal degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 327-340. [CrossRef]

- Aiba, I.; Hayashi, Y.; Shimohata, T.; Yoshida, M.; Saito, Y.; Wakabayashi, K.; Komori, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Ikeuchi, T.; Tokumaru, A.M., et al. Clinical course of pathologically confirmed corticobasal degeneration and corticobasal syndrome. Brain Commun 2023, 5, fcad296. [CrossRef]

- Valentino, R.R.; Koga, S.; Walton, R.L.; Soto-Beasley, A.I.; Kouri, N.; DeTure, M.A.; Murray, M.E.; Johnson, P.W.; Petersen, R.C.; Boeve, B.F., et al. MAPT subhaplotypes in corticobasal degeneration: assessing associations with disease risk, severity of tau pathology, and clinical features. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 218. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, J.S.; Karch, C.M.; Fan, C.C.; Bonham, L.W.; Kouri, N.; Ross, O.A.; Rademakers, R.; Kim, J.; Wang, Y.; Hoglinger, G.U., et al. Shared genetic risk between corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol 2017, 133, 825-837. [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, V.C.; Paraskevas, G.P.; Paraskevas, P.G.; Stefanis, L.; Kapaki, E. Corticobasal degeneration and corticobasal syndrome: A review. Clin Park Relat Disord 2019, 1, 66-71. [CrossRef]

- Mimuro, M.; Iwasaki, Y. Age-Related Pathology in Corticobasal Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Wenning, G.K.; Litvan, I.; Jankovic, J.; Granata, R.; Mangone, C.A.; McKee, A.; Poewe, W.; Jellinger, K.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; D'Olhaberriague, L., et al. Natural history and survival of 14 patients with corticobasal degeneration confirmed at postmortem examination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998, 64, 184-189. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. Visual signs and symptoms of corticobasal degeneration. Clin Exp Optom 2016, 99, 498-506. [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. The Spectrum of Cognitive Impairment in Atypical Parkinsonism Syndromes: A Comprehensive Review of Current Understanding and Research. Diseases 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.; Bak, T.H.; Hodges, J.R. Diagnostic criteria for corticobasal syndrome: a comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012, 83, 405-410. [CrossRef]

- Unti, E.; Mazzucchi, S.; Calabrese, R.; Palermo, G.; Del Prete, E.; Bonuccelli, U.; Ceravolo, R. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of dystonia and pain in corticobasal syndrome. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01182. [CrossRef]

- Chelban, V.; Catereniuc, D.; Aftene, D.; Gasnas, A.; Vichayanrat, E.; Iodice, V.; Groppa, S.; Houlden, H. An update on MSA: premotor and non-motor features open a window of opportunities for early diagnosis and intervention. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2754-2770. [CrossRef]

- Krismer, F.; Wenning, G.K. Multiple system atrophy: insights into a rare and debilitating movement disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 232-243. [CrossRef]

- Fanciulli, A.; Wenning, G.K. Multiple-system atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 249-263. [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, J.; Tsuji, S. Plasma Coenzyme Q10 Levels and Multiple System Atrophy-Reply. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 1499-1500. [CrossRef]

- Porto, K.J.; Hirano, M.; Mitsui, J.; Chikada, A.; Matsukawa, T.; Ishiura, H.; Japan Multiple System Atrophy Registry, C.; Toda, T.; Kusunoki, S.; Tsuji, S. COQ2 V393A confers high risk susceptibility for multiple system atrophy in East Asian population. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 429, 117623. [CrossRef]

- Cortelli, P.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Benarroch, E.E.; Giannini, G.; Iranzo, A.; Low, P.A.; Martinelli, P.; Provini, F.; Quinn, N.; Tolosa, E., et al. Stridor in multiple system atrophy: Consensus statement on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Neurology 2019, 93, 630-639. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, G.; Provini, F.; Cani, I.; Cecere, A.; Mignani, F.; Guaraldi, P.; Di Mirto, C.V.F.; Cortelli, P.; Calandra-Buonaura, G. Tracheostomy is associated with increased survival in Multiple System Atrophy patients with stridor. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 2232-2240. [CrossRef]

- Krismer, F.; Fanciulli, A.; Meissner, W.G.; Coon, E.A.; Wenning, G.K. Multiple system atrophy: advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2024, 23, 1252-1266. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, A.; Allocca, M.; Di Dato, R.; Puccini, G.; Laghai, I.; Rubino, F.; Nerattini, M.; Ramat, S.; Lombardi, G.; Ferrari, C., et al. FDG PET in the differential diagnosis of degenerative parkinsonian disorders: usefulness of voxel-based analysis in clinical practice. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 5333-5341. [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Dai, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, K.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. The value of PET/CT in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Parkinson's disease: a dual-tracer study. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 171. [CrossRef]

- Di Luca, D.G.; Perlmutter, J.S. Time for Clinical Dopamine Transporter Scans in Parkinsonism?: Not DAT Yet. Neurology 2024, 102, e209558. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Miyamoto, M. Reduced cardiac (123)I-MIBG uptake is a robust biomarker of Lewy body disease in isolated rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Brain Commun 2024, 6, fcae148. [CrossRef]

- Kimpinski, K.; Iodice, V.; Burton, D.D.; Camilleri, M.; Mullan, B.P.; Lipp, A.; Sandroni, P.; Gehrking, T.L.; Sletten, D.M.; Ahlskog, J.E., et al. The role of autonomic testing in the differentiation of Parkinson's disease from multiple system atrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 317, 92-96. [CrossRef]

- Pena-Zelayeta, L.; Delgado-Minjares, K.M.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Leon-Arcia, K.; Santiago-Balmaseda, A.; Andrade-Guerrero, J.; Perez-Segura, I.; Ortega-Robles, E.; Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Arias-Carrion, O. Redefining Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chelban, V.; Nikram, E.; Perez-Soriano, A.; Wilke, C.; Foubert-Samier, A.; Vijiaratnam, N.; Guo, T.; Jabbari, E.; Olufodun, S.; Gonzalez, M., et al. Neurofilament light levels predict clinical progression and death in multiple system atrophy. Brain 2022, 145, 4398-4408. [CrossRef]

- Singer, W.; Schmeichel, A.M.; Sletten, D.M.; Gehrking, T.L.; Gehrking, J.A.; Trejo-Lopez, J.; Suarez, M.D.; Anderson, J.K.; Bass, P.H.; Lesnick, T.G., et al. Neurofilament light chain in spinal fluid and plasma in multiple system atrophy: a prospective, longitudinal biomarker study. Clin. Auton. Res. 2023, 33, 635-645. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C.; Wang, N.; Rajan, S.; Kern, D.; Palma, J.A.; Kaufmann, H.; Freeman, R. Cutaneous alpha-Synuclein Signatures in Patients With Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2023, 100, e1529-e1539. [CrossRef]

- Shahnawaz, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Pritzkow, S.; Mendez, N.; Rabadia, P.; Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Schmeichel, A.; Singer, W.; Wu, G., et al. Discriminating alpha-synuclein strains in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Nature 2020, 578, 273-277. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Capotosti, F.; Schain, M.; Ohlsson, T.; Vokali, E.; Molette, J.; Touilloux, T.; Hliva, V.; Dimitrakopoulos, I.K.; Puschmann, A., et al. The alpha-synuclein PET tracer [18F] ACI-12589 distinguishes multiple system atrophy from other neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6750. [CrossRef]

- Valera, E.; Masliah, E. The neuropathology of multiple system atrophy and its therapeutic implications. Auton. Neurosci. 2018, 211, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Buur, L.; Wiedemann, J.; Larsen, F.; Ben Alaya-Fourati, F.; Kallunki, P.; Ditlevsen, D.K.; Sorensen, M.H.; Meulien, D. Randomized Phase I Trial of the alpha-Synuclein Antibody Lu AF82422. Mov Disord 2024, 39, 936-944. [CrossRef]

- Alterity Therapeutics. Alterity Therapeutics Reports Positive Topline Data from Open-Label Phase 2 Clinical Trial of ATH434 in Multiple System Atrophy. Availabe online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/07/28/3122359/0/en/Alterity-Therapeutics-Reports-Positive-Topline-Data-from-Open-Label-Phase-2-Clinical-Trial-of-ATH434-in-Multiple-System-Atrophy.html (accessed on 2025/09/08).

- Respondek, G.; Kurz, C.; Arzberger, T.; Compta, Y.; Englund, E.; Ferguson, L.W.; Gelpi, E.; Giese, A.; Irwin, D.J.; Meissner, W.G., et al. Which ante mortem clinical features predict progressive supranuclear palsy pathology? Mov Disord 2017, 32, 995-1005. [CrossRef]

- Concha-Marambio, L.; Pritzkow, S.; Shahnawaz, M.; Farris, C.M.; Soto, C. Seed amplification assay for the detection of pathologic alpha-synuclein aggregates in cerebrospinal fluid. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 1179-1196. [CrossRef]

| Feature | Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) | Corticobasal Syndrome (CBS/CBD) | Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) | Parkinson’s Disease (PD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | ~7 per 100,000 | ~4 per 100,000 | ~4 per 100,000 | Much higher than atypical parkinsonisms |

| Onset Age | ~63 years | >60 years, variable | 53–55 years | Typically >60 years |

| Motor Symptoms | Symmetric parkinsonism, early axial rigidity, backwards falls | Asymmetric rigidity, dystonia, myoclonus, apraxia | MSA-P: symmetric parkinsonism (poor levodopa response); MSA-C: cerebellar signs (ataxia, dysarthria) | Asymmetric parkinsonism, classic rest tremor, shuffling gait |

| Ocular Signs | Vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, slow vertical saccades | Difficulty initiating voluntary saccades, gaze apraxia | Rare, nonspecific ocular signs | Rare ocular involvement |

| Cognitive Profile | Subcortical dementia (executive dysfunction, slowed processing) | Frontal-executive and parietal dysfunction; alien limb; cortical sensory loss | Cognitive impairment may occur, but not early or prominent | Cognitive impairment usually occurs late (dementia in advanced PD) |

| Autonomic Dysfunction | Not prominent early; may appear late | Rare or mild | Prominent: orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence/retention, erectile dysfunction, constipation | Mild compared with MSA |

| Key Pathology | 4R-tauopathy (globose tangles, tufted astrocytes) | 4R-tauopathy (astrocytic plaques, ballooned neurons) | α-synucleinopathy (glial cytoplasmic inclusions) | α-synucleinopathy (Lewy bodies) |

| Imaging | Midbrain atrophy (“hummingbird sign”); ↑MRPI 2.0 | Asymmetric frontoparietal atrophy (contralateral to the affected limb) | “Hot cross bun” sign (pons), putaminal atrophy/hypointensity | Often, normal or nonspecific changes |

| Levodopa Response | Poor, transient at best | Poor or absent | Poor or transient (rare sustained response) | Good, especially early |

| Other Key Features | Early falls (<3 yrs), pseudobulbar palsy, reduced blink, square-wave jerks | Alien limb, cortical sensory loss, asymmetric apraxia | Early stridor, rapid progression, cold extremities, REM sleep behavior disorder | Classic pill-rolling tremor, clear honeymoon response to levodopa |

| Teaching tip for students | Falls and eye movement problems early | Asymmetric parkinsonism with cortical signs (apraxia, alien limb phenomenon). | Autonomic failure plus parkinsonism/ataxia | Asymmetric, tremor-dominant, levodopa-responsive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).