Submitted:

13 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

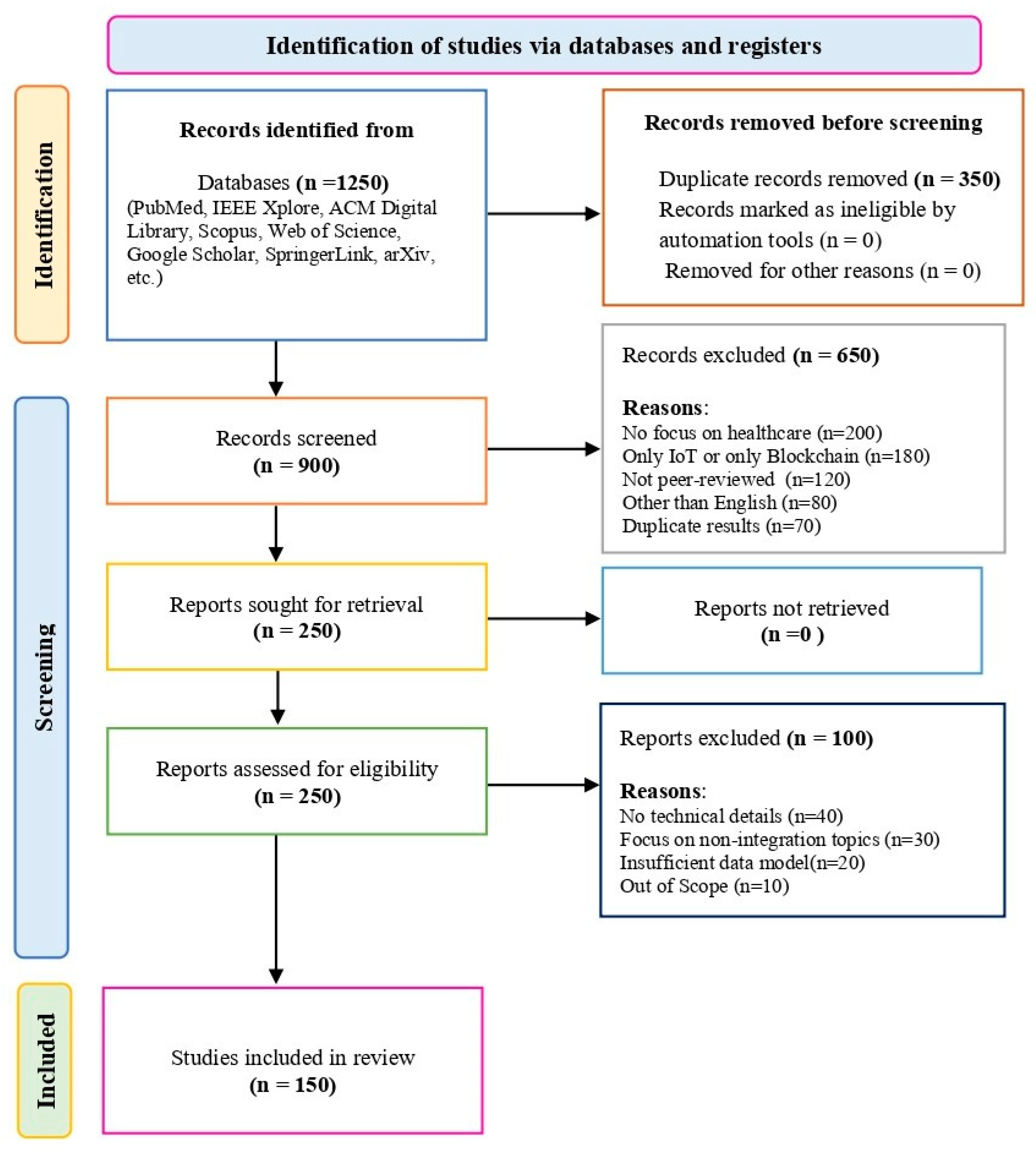

2. Methodology

3. Background and Fundamentals

4. Medical Application and Analysis

4.1. Reducing Emergency Department (ED) Wait Times

4.2. Telehealth and Remote Monitoring

4.3. Information Monitoring and Data Collection

4.4. Medication Management

4.5. Food and Nutrition Management

4.6. Glucose Level Monitoring

4.7. Electrocardiogram (ECG) Monitoring

4.8. Blood Pressure Monitoring

4.9. Oxygen Saturation Monitoring

4.10. Rehabilitation Systems

5. IoT and Machine Learning in Healthcare

5.1. Module for Machine Learning

5.2. Data Exchange and Integration

5.3. Blockchain-Based Solution Frameworks for Distributed Data Exchange

5.4. Current Situation with Medical Records

6. Services of IoT Healthcare Blockchain

6.1. Identification and Tracking via RFID Technology

6.2. Edge Computing for Improved Healthcare Performance

6.3. Semantics and Interoperability in IoT

6.4. Cloud Computing for Healthcare Data Management

6.5. Big Data in Healthcare

6.6. Grid Computing for Healthcare Innovation

6.7. Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) in Healthcare

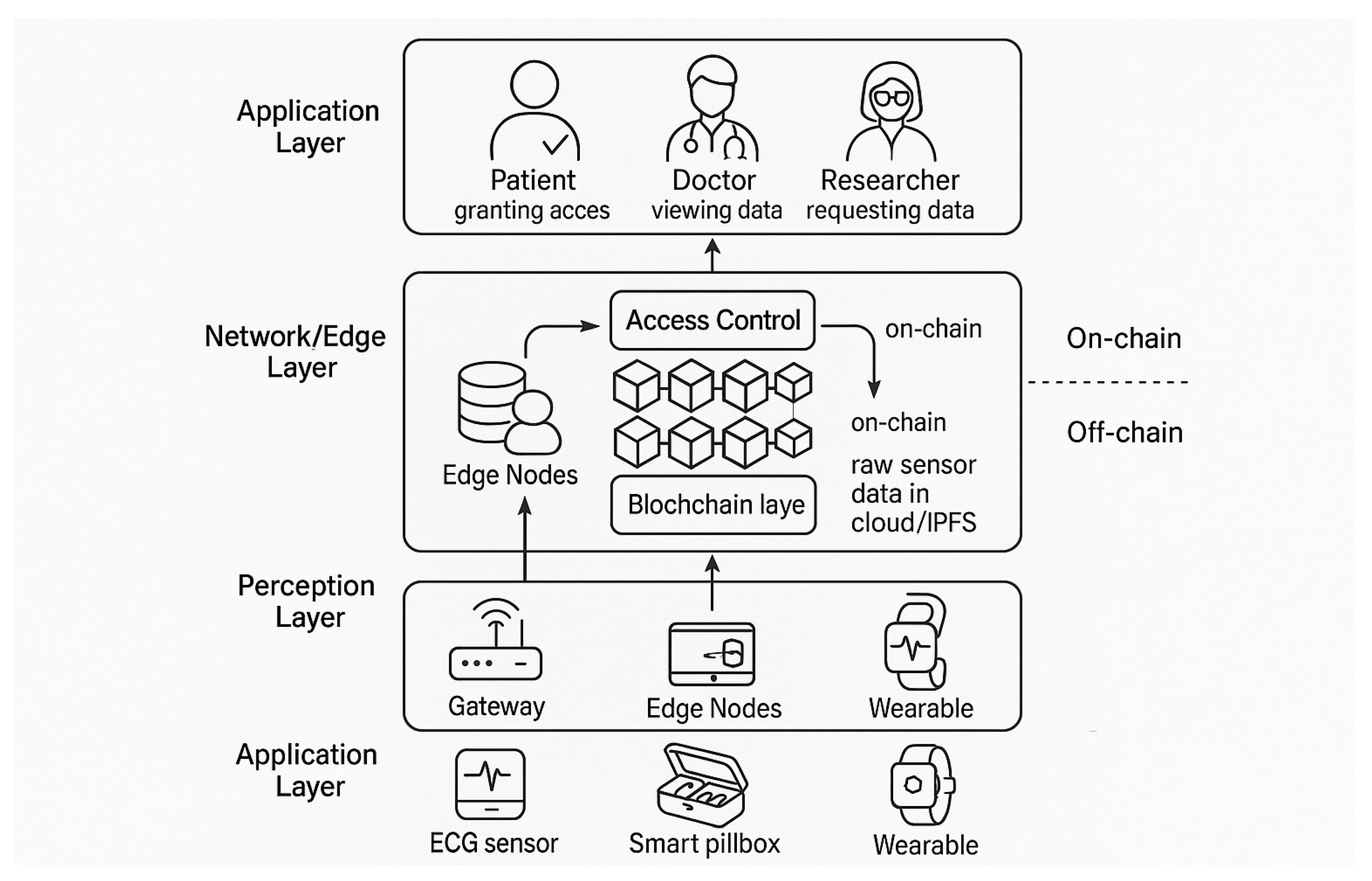

7. IoT Healthcare Blockchain Networks

7.1. Design of the IoThNet

7.2. IoThNet Organization

- Composition: Organizing the network components and data flow.

- Signalization: Ensuring the Quality of Service (QoS) and resource allocation.

- Data Transmission: Facilitating data exchange across the network with efficiency and security.

7.3. IoThNet Platforms

7.4. Blockchain Transaction and Access Management:

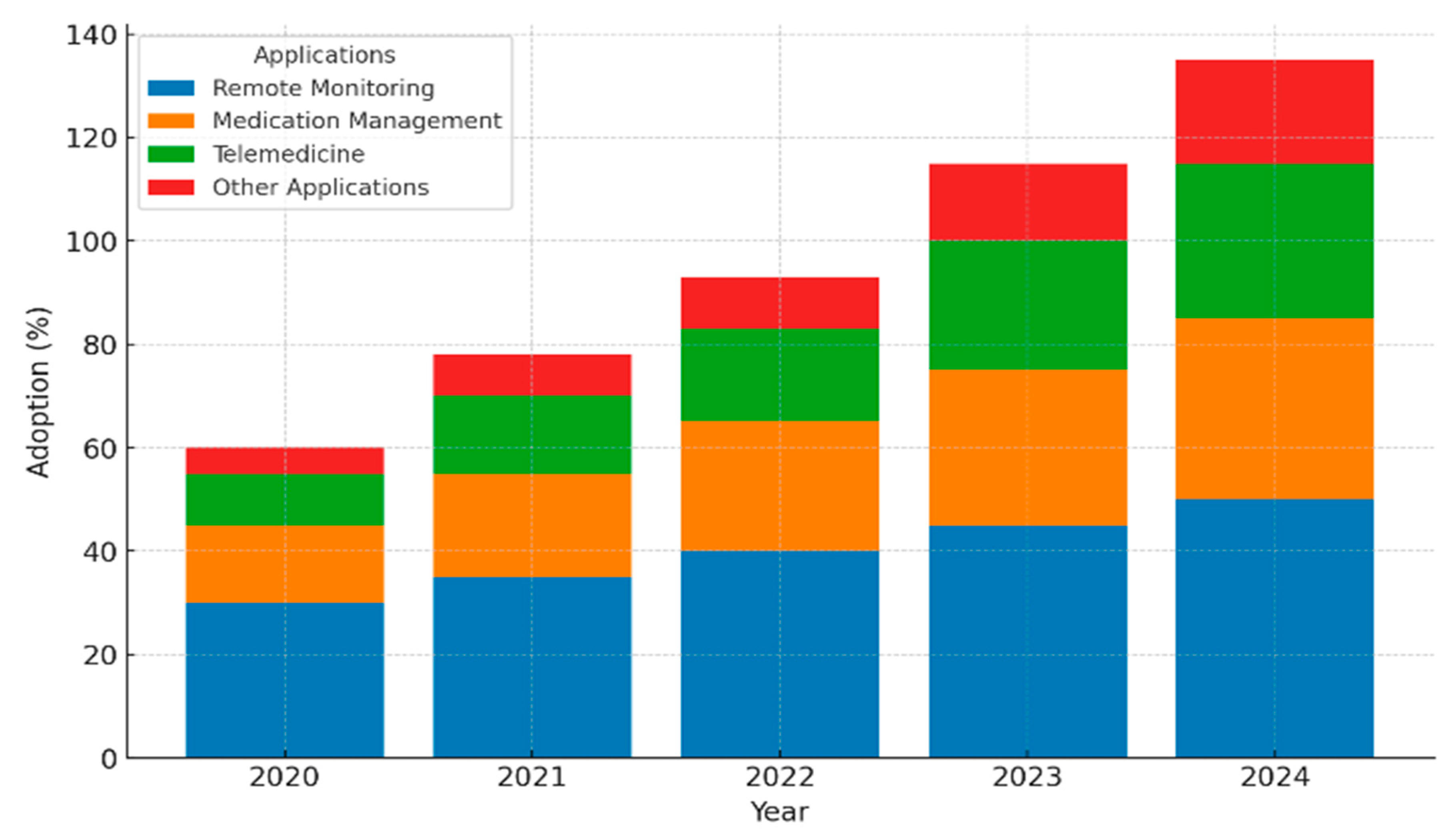

8. Market Overview

9. Open Research Challenges and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Siyal, A.A.; Junejo, A.Z.; Zawish, M.; Ahmed, K.; Khalil, A.; Soursou, G. Applications of blockchain technology in medicine and healthcare: Challenges and future perspectives. Cryptography 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Dhar, S.; Singh, R. Decentralized privacy-preserving healthcare blockchain for IoT. Sensors 2019, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubovitskaya, A.; Xu, Z.; Ryu, S.; Schumacher, M.; Wang, F. (2017). Secure and trustable electronic medical records shared using blockchain. In AMIA annual symposium proceedings (Vol. 2017, p. 650). American Medical Informatics Association.

- Zheng, Z.; et al. (2017). An overview of blockchain technology: Architecture, consensus, and future trends. In Big Data (BigData Congress), 2017 IEEE International Congress on. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; et al. (2017). Lightweight Backup and Efficient Recovery Scheme for Health Blockchain Keys. In Autonomous Decentralized System (ISADS), 2017 IEEE 13th International Symposium on. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.M.; Johnson, S.D. (2018). The consumer security index for IoT: A protocol for developing an index to improve consumer decision making and to incentivize greater security provision in IoT devices. In Proc. Living Internet Things Cybersecurity IoT (IET), London, U.K.; p. 7.

- Amendola, S.; Lodato, R.; Manzari, S.; Occhiuzzi, C.; Marrocco, G. RFID technology for IoT-based personal healthcare in smart spaces. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2014, 1, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.F. (2017). Health care monitoring system in Internet of Things (IoT) by using RFID. In Proc. 6th Int. Conf. Ind. Technol. Manag. (ICITM), 198–204.

- Abinaya, G.; Sampoornam, K.P. An efficient healthcare system in IoT platform using RFID system. Int. J. Adv. Res. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2017, 5, 421–424. [Google Scholar]

- Oueida, S.; Kotb, Y.; Aloqaily, M.; Jararweh, Y.; Baker, T. An edge computing-based smart healthcare framework for resource management. Sensors Multidiscipl. Digit. Publ. Inst. 2018, 18, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otoum, S.; Ahmed, M.; Mouftah, H.T. (2015). Sensor medium access control (SMAC)-based epilepsy patients monitoring system. In Proc. IEEE 28th Can. Conf. Elect. Comput. Eng. (CCECE), Halifax, NS, Canada, 1109–1114.

- Jabbar, S.; Ullah, F.; Khalid, S.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Semantic interoperability in heterogeneous IoT infrastructure for healthcare. Wireless Commun. Mobile Comput. 2017, 2017, Art. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Sheth, A.; Anantharam, P. (2015). Semantic gateway as a service architecture for IoT interoperability. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Mobile Serv.; New York, NY, USA, 313–319.

- Yrard, A.; Serrano, M. (2016). Connected smart cities: Interoperability with SEG 3.0 for the Internet of Things. In Proc. 30th Int. Conf. Adv. Inf. Netw. Appl. Workshops (WAINA), Crans-Montana, Switzerland, 796–802.

- Baker, S.B.; Xiang, W.; Atkinson, I. Internet of Things for smart healthcare: Technologies, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 26521–26544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N. Making use of cloud computing for healthcare provision: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access 2014, 34, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, L.A.; Mehmood, R.; Benkhlifa, E.; Song, H. Mobile cloud computing model and big data analysis for healthcare applications. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 6171–6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargheese, R.; Viniotis, Y. (2014). Influencing data availability in IoT enabled cloud based e-health in a 30-day readmission context. In Proc. 10th IEEE Int. Conf. Collab. Comput. Netw. Appl. Worksharing, Miami, FL, USA, 475–480.

- Xu, B.; Xu, L.D.; Cai, H.; Xie, C.; Hu, J.; Bu, F. Ubiquitous data accessing method in IoT-based information system for emergency medical services. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2014, 10, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanavati, S.; Abawajy, J.; Izadi, D. (2016). An alternative sensor cloud architecture for vital signs monitoring. In Proc. Int. Joint Conf. Neural Netw. (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2827–2833.

- Lin, K.; Xia, F.; Wang, W.; Tian, D.; Song, J. System design for big data application in emotion-aware healthcare. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 6901–6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, H.; Lee, E.K.; Pompili, D. (2012). Mobile grid computing for data- and patient-centric ubiquitous healthcare. In Proc. 1st IEEE Workshop Enabling Technol. Smartphone Internet Things (ETSIoT), Seoul, South Korea, 36–41.

- Brust, C. (2009). Grid computing in a healthcare environment: A framework for enterprise design and implementation. In Proc. Annu. Conf. Midwest United States Assoc. Inf. Syst. (MWAIS), 33.

- Weisbecker, A.; Falkner, J.; Rienhoff, O. (2009). MediGRID—Grid computing for medicine and life sciences. In Grid Computing. Springer, 57–65.

- Hamza-Lup, F.G.; Rolland, J.P.; Hughes, C. (2018). A distributed augmented reality system for medical training and simulation. arXiv:1811.12815, arXiv:1811.12815.

- Ha, H.-G.; Hong, J. Augmented reality in medicine. Hanyang Med. Rev. 2016, 36, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State, A.; et al. (1994). Observing a volume rendered fetus within a pregnant patient. In Proc. Vis.; Washington, DC, USA, 364–368.

- Argotti, Y.; Davis, L.; Outters, V.; Rolland, J.P. Dynamic superimposition of synthetic objects on rigid and simple-deformable real objects. Comput. Graph. 2002, 26, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Wu, S.-L. Analyzing healthcare big data with prediction for future health condition. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 9786–9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majeed, S.S.; Al-Mejibli, I.S.; Karam, J. (2015). Home telehealth by Internet of Things (IoT). In Proc. IEEE 28th Can. Conf. Elect. Comput. Eng. (CCECE), Halifax, NS, Canada, 609–613.

- Pallavi, K.; Tripti, K. Secure health monitoring of soldiers with tracking system using IoT: A survey. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Develop. 2019, 3, 693–696. [Google Scholar]

- Jara, A.J.; Zamora, M.A.; Skarmeta, A.F. Drug identification and interaction checker based on IoT to minimize adverse drug reactions and improve drug compliance. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2014, 18, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.; Durgaprasadarao, P.; Raj, V.N.P. (2018). Intelligent medicine box for medication management using IoT. In Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Inventive Syst. Control (ICISC), Coimbatore, India, 32–34.

- Prajapati, B.; Parikh, S.M.; Patel, J. (2018). An IoT-based model to monitor real-time effect of drug. In Proc. 3rd Int. Conf. Internet Things Connected Technol. (ICIoTCT), 26–27.

- Sundaravadivel, P.; Kesavan, K.; Kesavan, L.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E. Smart-Log: A deep-learning-based automated nutrition monitoring system in the IoT. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2018, 64, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendi, E.; Ozyavuz, O.; Pekesen, E.; Bayrak, C. (2013). Food intake monitoring system for mobile devices. In Proc. 5th IEEE Int. Workshop Adv. Sens. Interfaces (IWASI), Bari, Italy, 31–33.

- Istepanian, R.S.H.; Hu, S.; Philip, N.Y.; Sungoor, A. (2016). The potential of Internet of m-health things ‘m-IoT’ for non-invasive glucose level sensing. In Proc. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc.; 5264–5266.

- Lijun, Z. (2013). Multi-parameter medical acquisition detector based on Internet of Things. Chinese Patent CN202 960 774U.

- Deshpande, U.U.; Kulkarni, M.A. (2014). IoT-based real-time ECG monitoring system using Cypress WICED. Int. J. Adv. Res. Elect. Electron. Instrum. Eng.; 6.

- Castillejo, P.; Martinez, J.-F.; Rodriguez-Molina, J.; Cuerva, A. Integration of wearable devices in a wireless sensor network for an e-health application. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2013, 20, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, E.; et al. (2013). The smartphone as a medical device: Assessing enablers, benefits, and challenges. In Proc. IEEE Int. Workshop Internet Things Netw. Control (IoT-NC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 48–52.

- Liu, M.-L.; Tao, L.; Yan, Z. (2012). Internet of Things-based electrocardiogram monitoring system. Chinese Patent CN102 764 118A.

- Xin, T.J.; Min, B.; Jie, J. (2013). Carry-on blood pressure/pulse rate/blood oxygen monitoring location intelligent terminal based on Internet of Things. Chinese Patent CN202 875 315U.

- Puustjärvi, J.; Puustjärvi, L. (2011). Automating remote monitoring and information therapy: An opportunity to practice telemedicine in developing countries. In Proc. IST Africa Conf.; 1–9.

- Tarouco, L.M.R.; et al. (2012). Internet of Things in healthcare: Interoperability and security issues. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Commun. (ICC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 6121–6125.

- Dohr, A.; Modre-Opsrian, R.; Drobics, M.; Hayn, D.; Schreier, G. (2010). The Internet of Things for ambient assisted living. In Proc. 7th Int. Conf. Inf. Technol. New Gener.; Las Vegas, NV, USA, 804–809.

- Larson, E.C.; Lee, T.; Liu, S.; Rosenfeld, M.; Patel, S.N. (2011). Accurate and privacy-preserving cough sensing using a low-cost microphone. In Proc. 13th Int. Conf. Ubiquitous Comput.; 375–384.

- Khattak, H.A.; Ruta, M.; Di Sciascio, E.E. (2014). CoAP-based healthcare sensor networks: A survey. In Proc. 11th Int. Bhurban Conf. Appl. Sci. Technol. (IBCAST), Islamabad, Pakistan, 499–503.

- Larson, E.C.; Goel, M.; Boriello, G.; Heltshe, S.; Rosenfeld, M.; Patel, S.N. (2012). SpiroSmart: Using a microphone to measure lung function on a mobile phone. In Proc. ACM Conf. Ubiquitous Comput.; 280–289.

- Guangnan, Z.; Penghui, L. (2012). IoT (Internet of Things) control system facing rehabilitation training of hemiplegic patients. Chinese Patent CN202 587 045U.

- Fan, Y.J.; Yin, Y.H.; Xu, L.D.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, F. IoT-based smart rehabilitation system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2014, 10, 1568–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.; Tian, O. (2014). Short paper: Using BSN for tele-health application in upper limb rehabilitation. In Proc. IEEE World Forum Internet Things (WF-IoT), Seoul, South Korea, 169–170.

- Liang, S.; Zilong, Y.; Hai, S.; Trinidad, M. (2011). Childhood autism language training system and Internet-of-Things-based centralized training center. Chinese Patent CN102 184 661A.

- Sreekanth, K.U.; Nitha, K.P. A study on health care in Internet of Things. Int. J. Recent Innovat. Trends Comput. Commun. 2016, 4, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- ED wait times in the news - 3 keys to lower them for patients. (2020). Retrieved April 26, 2020. Available online: http://www.healthcarebusinesstech.com/ed-wait-times-analytics/.

- Healthcare Business Tech. (n.d.). Future of IoT in hospitals. Retrieved April 26, 2020. Available online: http://www.healthcarebusinesstech.com/iothospital-future.

- Will Edge Computing Transform Healthcare? (2019). Retrieved April 26, 2020. Available online: https://healthtechmagazine.net/article/2019/08/will-edge-computing-transform-healthcare.

- 5 Use Cases to Know for Edge Computing and Healthcare. (2019). Retrieved April 26, 2020. Available online: https://www.vxchnge.com/blog/edge-computing-use-cases-healthcare.

- How IoT Is Enabling the Telemedicine of Tomorrow. (2018). Available online: https://www.iotforall.com/how-iot-enables-tomorrows-telemedicine/.

- Medication Management for Patients Through IoT-Enabled Smart Pillboxes. (2017). Available online: https://iiot-world.com/smarthealthcare/medication-management-for-patients-through-iot-enabled-smart-pillboxes/.

- Ojas, S.; Akshay, S.; Rohitkumar, S.; Trupti, A. (2017). IoT-based telemedicine system. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Power Control Signals Instrum. Eng. (ICPCSI), Chennai, India, 2840–2842.

- Saminathan, S.; Geetha, K. Real-time health care monitoring system using IoT. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Dhar, S.; Singh, R. A decentralized privacy-preserving healthcare blockchain for IoT. Sensors Multidiscipl. Digit. Publ. Inst. 2019, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Tripathi, R.C. (2020). Performance of Internet of Things (IoT) based healthcare secure services and its importance: Issue and challenges. In Proc. Int. Conf. Innovat. Comput. Commun. (ICICC), 4.

- Kadhim, K.T.; Alsahlany, A.M.; Wadi, S.M.; Kadhum, H.T. An overview of patient’s health status monitoring system based on Internet of Things (IoT). Wireless Pers. Commun. 2020, 114, 2235–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemlouma, T.; Laborie, S.; Roose, P.; Rachedi, A.; Abdelaziz, K. (2014). A study of mobility support in wearable health monitoring systems: Design framework. Cleveland, OH, USA: CRC Press.

- Boulemtafes, A.; Rachedi, A.; Badache, N. (2015). A study of mobility support in wearable health monitoring systems: Design framework. In Proc. IEEE/ACS 12th Int. Conf. Comput. Syst. Appl. (AICCSA), Marrakech, Morocco, 1–8.

- Lemlouma, T.; Rachedi, A.; Chalouf, M.A.; Chellouche, S.A. (2013). A new model for NGN pervasive e-Health services. In Proc. 1st Int. Symp. Future Inf. Commun. Technol. Ubiquitous HealthCare (Ubi-HealthTech), Jinhua, China, 1–5.

- He, D.; Zeadally, S.; Kumar, N.; Lee, J.H. Anonymous authentication for wireless body area networks with provable security. IEEE Syst. J. 2017, 11, 2590–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngankam, H.K.; et al. An IoT architecture of microservices for ambient assisted living environments to promote aging in smart cities. In Proc. Int. Conf. Smart Homes Health Telematics 2019, 11, 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Minoli, D.; Sohraby, K.; Occhiogrosso, B. (2017). IoT security (IoTSec) mechanisms for e-Health and ambient assisted living applications. In Proc. IEEE/ACM Int. Conf. Connected Health Appl. Syst. Eng. Technol. (CHASE), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 13–18.

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Wilson, J.T.; Clauson, K.A. Geospatial blockchain: promises, challenges, and scenarios in health and healthcare. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2018, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, S.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yang, S. Blockchain-based medical records secure storage and medical service framework. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 43, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.-T.; Kim, H.-E.; Ohno-Machado, L. Blockchain distributed ledger technologies for biomedical and health care applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamoshina, P.; Ojomoko, L.; Yanovich, Y.; Ostrovski, A.; Botezatu, A.; Prikhodko, P.; et al. Converging blockchain and next-generation artificial intelligence technologies to decentralize and accelerate biomedical research and healthcare. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 5665–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, M. (2016). Blockchain technology in healthcare: The revolution starts here. In 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), 1–3. IEEE. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7749510.

- Furlonger, D.; Kandaswamy, R. (2018). Hype Cycle for Blockchain Business. Retrieved December 3, 2018. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/doc/3884146/hype-cycle-blockchain-business.

- Kuo, T.-T.; Kim, H.-E.; Ohno-Machado, L. Blockchain distributed ledger technologies for biomedical and health care applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angraal, S.; Krumholz, H.M.; Schulz, W.L. Blockchain technology: applications in health care. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2017, 10, e003800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, M. (2016). Blockchain technology in healthcare: The revolution starts here. In 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), 1–3. IEEE. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7749510.

- Kuo, T.-T.; Zavaleta Rojas, H.; Ohno-Machado, L. (2019). Comparison of blockchain platforms: a systematic review and healthcare examples. JAMIA. [CrossRef]

- Ivan, D. (2016). Moving Toward a Blockchain-based Method for the Secure Storage of Patient Records. ONC/NIST Use of Blockchain for Healthcare and Research Workshop. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/9-16-drew_ivan_20160804_blockchain_for_healthcare_final.pdf.

- Azaria, A.; Ekblaw, A.; Vieira, T.; Lippman, A. (2016). MedRec: Using Blockchain for Medical Data Access and Permission Management. In International Conference on Open and Big Data (OBD), Vienna: IEEE, 25–30.

- Kuo, T.-T.; Ohno-Machado, L. (2018). ModelChain: decentralized privacy-preserving healthcare predictive modeling framework on private blockchain networks. arXiv. arXiv:1802.01746.

- Kuo, T.-T.; Gabriel, R.A.; Ohno-Machado, L. (2019). Fair compute loads enabled by blockchain: sharing models by alternating client and server roles. JAMIA. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. Simple demographics often identify people uniquely. Health 2000, 671, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, D. (2015). Data Breaches in Healthcare Totaled Over 112 Million Records in 2015. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/danmunro/2015/12/31/data-breaches-in-healthcare-total-over-112-million-records-in-2015/#15b74ef7b07f.

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Y.; Cui, L.; Cheng, S.; Ohno-Machado, L. Expectation propagation logistic regression (explorer): distributed privacy-preserving online model learning. J. Biomed. Inform. 2013, 46, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Kim, J.; Ohno-Machado, L. Grid Binary LOgistic REgression (GLORE): building shared models without sharing data. JAMIA 2012, 19, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, F. (2020). Apple and Google partner on COVID-19 contact tracing technology. Apple News. Available online: https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2020/04/apple-and-google-partner-on-covid-19-contact-tracing-technology/.

- Mackey, T.K.; Kuo, T.; Gummadi, B.; et al. ‘Fit-for-purpose?’ - Challenges and opportunities for applications of blockchain technology in the future of healthcare. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Institute for Business Value. (2018). Team medicine: how life sciences can win with blockchain. IBM Corporation. Retrieved March 12, 2018. Available online: https://public.dhe.ibm.com/common/ssi/ecm/03/en/03013903usen/team-medicine.pdf.

- Rosenbaum, L. (2019). Anthem will use blockchain to secure medical data for its 40 million members in three years. Forbes, December 12. Retrieved March 17, 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/leahrosenbaum/2019/12/12/anthem-says-its-40-million-members-will-be-using-blockchain-to-secure-patient-data-in-three-years/#305bc9be6837.

- Kuo, T.-T.; Kim, H.-E.; Ohno-Machado, L. Blockchain distributed ledger technologies for biomedical and health care applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, M.B. An introduction to the blockchain and its implications for libraries and medicine. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2017, 36, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaeger, K.; Martini, M.; Rasouli, J.; et al. Emerging blockchain technology solutions for modern healthcare infrastructure. J. Sci. Innov. Med. 2019, 9, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, K. (2018). How is blockchain revolutionizing healthcare? The Startup, October 23. Retrieved January 17, 2020. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/how-is-blockchain-revolutionizing-healthcare-d971d351528f.

- Pirtle, C.; Ehrenfeld, J.M. Blockchain for healthcare: the next generation of medical records? J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjape, K.; Parker, M.; Houlding, D.; et al. (2019). Implementation considerations for blockchain in healthcare institutions. Blockchain in Healthcare Today, 2.

- Singh, N. Blockchain for healthcare: use cases and applications. 101 Blockchains, November 21. Retrieved January 18 2019, 2020. Available online: https://101blockchains.com/blockchain-for-healthcare/.

- Hillestad, R.; Bigelow, J.; Bower, A.; et al. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff. 2019, 24, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaeger, K.; Martini, M.; Rasouli, J.; et al. Emerging blockchain technology solutions for modern healthcare infrastructure. J. Sci. Innov. Med. 2019, 9, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, D. (2016). Blockchain Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction in 25 Steps. ISBN 13: 978-1484226032.

- Laurence, T. (2018). Blockchain For Dummies (For Dummies (Computers)). ISBN 978-1-119-36559-4.

- Reed, J. (2018). Blockchain, Smart Contracts, Investing in Ethereum, FinTech (Kindle Edition).

- Mitnick, G. (2018). Blockchain: Learn Blockchain Technology FAST! Everything You Need to Know About Blockchain in 1 Hr! (Kindle Edition).

- Ethereum Foundation. (2017). Update on integrating Zcash with Ethereum. Available online: https://blog.ethereum.org/2017/01/19/update-integrating-zcash-ethereum.

- Gordon, W.J.; Catalini, C. Blockchain technology for healthcare: facilitating the transition to patient-driven interoperability. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postelnicu, L. (2020). How the world of health and tech is looking at the coronavirus outbreak. Mobihealthnews, March 11. Retrieved March 22, 2020. Available online: https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/europe/how-world-health-and-tech-looking-coronavirus-outbreak.

- Paranjape, K.; Parker, M.; Houlding, D.; et al. (2019). Implementation considerations for blockchain in healthcare institutions. Blockchain in Healthcare Today, Volume 2, July.

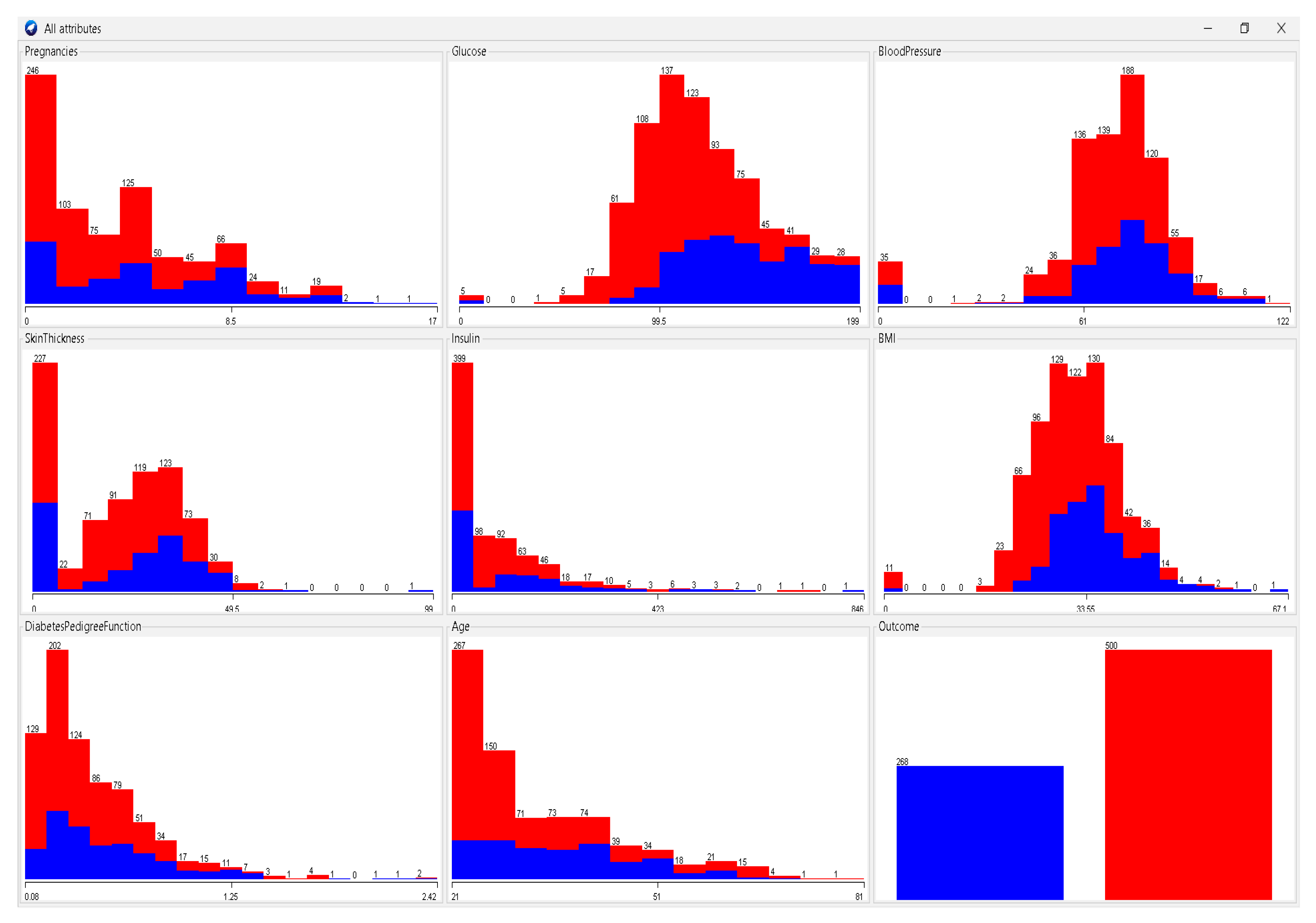

- Diabetes Prediction. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/mvanshika/diabetes-prediction/data.

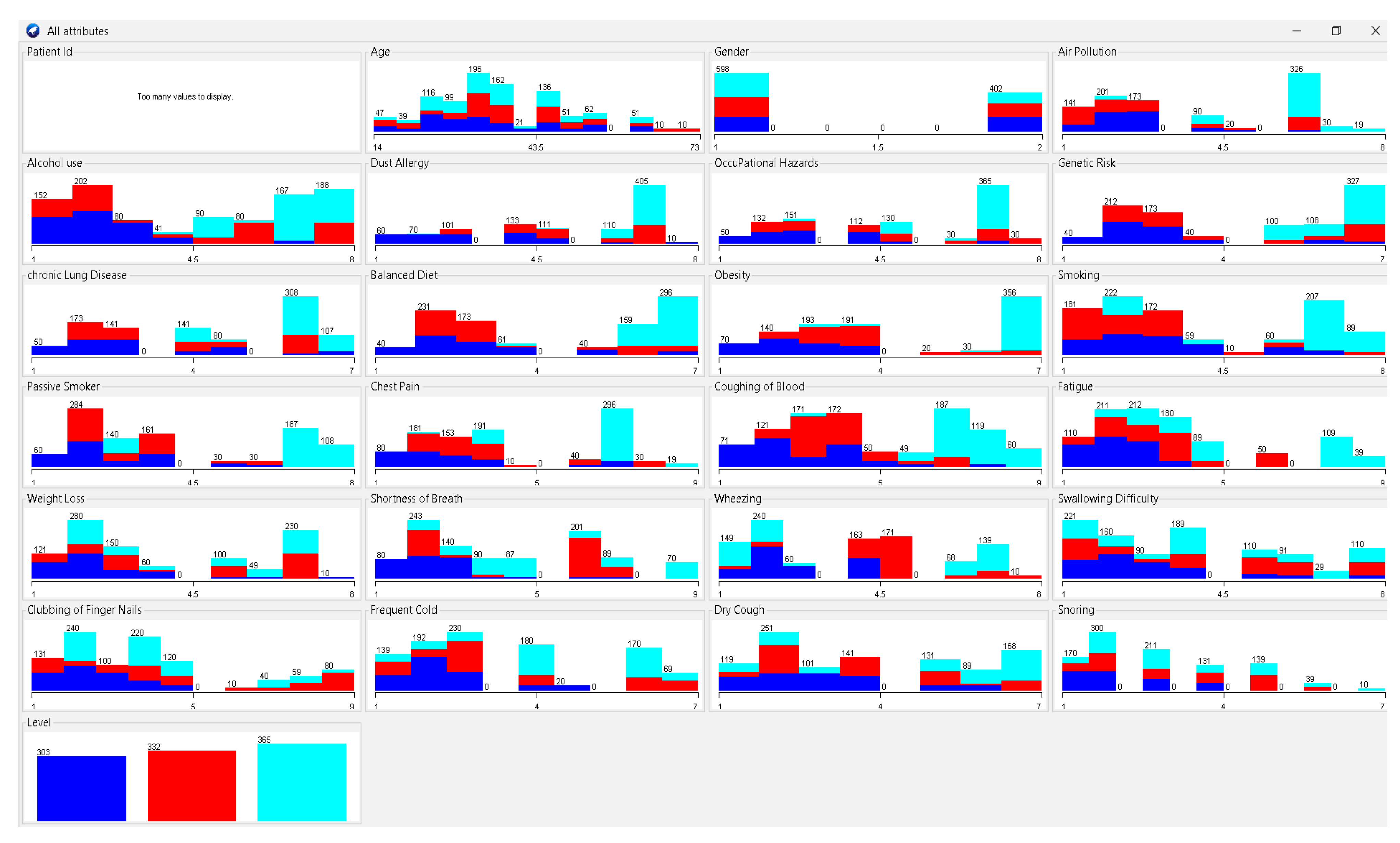

- Cancer Patients Data. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rishidamarla/cancer-patients-data.

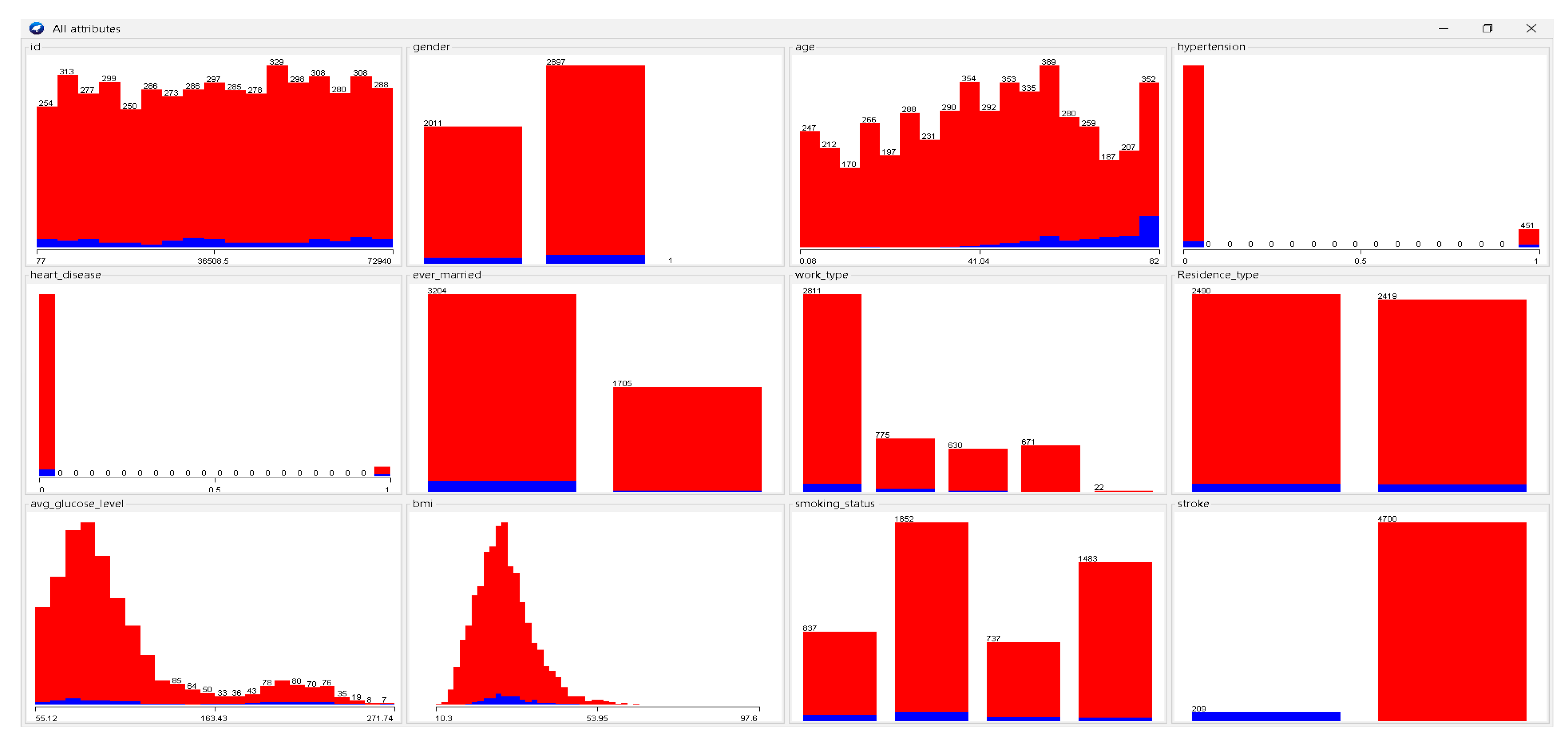

- Stroke Prediction Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/fedesoriano/stroke-prediction-dataset.

- Vavekanand, R.; Sam, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, T. Cardiacnet: A neural networks based heartbeat classifications using ecg signals. Studies in Medical and Health Sciences 2024, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavekanand, R.; Kumar, T. Data augmentation of ultrasound imaging for non-invasive white blood cell in vitro peritoneal dialysis. Biomedical Engineering Communications 2024, 3, 10–53388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavekanand, R. SUBMIP: smart human body health prediction application system based on medical image processing. Studies in Medical and Health Sciences 2024, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.B.; Rashid, M.; Vavekanand, R.; Singh, V. Integrating explainable AI for skin lesion classifications: A systematic literature review. Studies in Medical and Health Sciences 2025, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.; Nawaz, S.; Vavekanand, R. CardioMix: A Multimodal Image-Based Classification Pipeline for Enhanced ECG Diagnosis. Med Data Min 2025, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M. Blockchain technology in healthcare: Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Healthcare Management 2022, 15, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressi, D.; Romanello, R.; Piazza, C.; Rossi, S. AI-enhanced blockchain technology: A review of advancements and opportunities. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 225, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawashin, D.; Nemer, M.; Gebreab, S.A.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Khan, M.K.; Damiani, E. Blockchain applications in UAV industry: Review, opportunities, and challenges. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2024, 230, 103932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.B.; Ahmed, Y.; Mahmoud, H.; Shah, S.A.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Taramonli, S.; Aneiba, A. A survey on blockchain technology in the maritime industry: Challenges and future perspectives. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 157, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, E. Blockchain for finance: A survey. IET Blockchain 2024, 4, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taloba, A.I.; Elhadad, A.; Rayan, A.; Abd El-Aziz, R.M.; Salem, M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Park, C. A blockchain-based hybrid platform for multimedia data processing in IoT-Healthcare. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 65, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Bourouis, S.; Kamruzzaman, M.M.; Hadjouni, M.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Dhahbi, S. Data security in healthcare industrial internet of things with blockchain. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 25144–25151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbeg, K.; Ouchetto, O.; Andaloussi, S.J.; Fetjah, L. A taxonomic review of the use of IoT and blockchain in healthcare applications. Irbm 2022, 43, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasudra, S.; Sharma, P.; Crespo, R.G.; Shanmuganathan, V. Blockchain-based medical certificate generation and verification for IoT-based healthcare systems. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine 2022, 12, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.M.; Yan, B.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Alruwaili, O.; Wu, M.; Alrashdi, I. Blockchain and fog computing in IoT-driven healthcare services for smart cities. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2022, 2022, 9957888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, K.; Kumar, T.; Mileo, A.; Bendechache, M. (2024, August). OxML Challenge 2023: Carcinoma classification using data augmentation. In IET Conference Proceedings CP887 (Vol. 2024, No. 10, pp. 303–306). Stevenage, UK: The Institution of Engineering and Technology.

- Barua, M.; Kumar, T.; Raj, K.; Roy, A.M. Comparative analysis of deep learning models for stock price prediction in the Indian market. FinTech 2024, 3, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Mileo, A. (2024, September). Towards Understanding Graph Neural Networks: Functional-Semantic Activation Mapping. In International Conference on Neural-Symbolic Learning and Reasoning (pp. 98–106). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Darwish, A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Elhoseny, M.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Muhammad, K. The impact of the hybrid platform of internet of things and cloud computing on healthcare systems: opportunities, challenges, and open problems. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2019, 10, 4151–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sasirekha, S.P.; Dhakne, A.; Thrinath, B.S.; Ramya, D.; Thiagarajan, R. IOT enabled hybrid model with learning ability for E-health care systems. Measurement: Sensors 2022, 24, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, B.; Cao, A.; He, Z.; Wu, D. (2018, December). EdgeCNN: A hybrid architecture for agile learning of healthcare data from IoT devices. In 2018 IEEE 24th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS) (pp. 852–859). IEEE.

- Rathee, G.; Sharma, A.; Saini, H.; Kumar, R.; Iqbal, R. A hybrid framework for multimedia data processing in IoT-healthcare using blockchain technology. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 9711–9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, A.; Catal, C.; Kar, G.; Mishra, A. Hybrid blockchain platforms for the internet of things (IoT): A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Meesad, P. (2021). Hybrid AI and IoT Approaches Used in Health Care for Patients Diagnosis. In Hybrid Artificial Intelligence and IoT in Healthcare (pp. 97–108). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Bibani, O.; Mouradian, C.; Yangui, S.; Glitho, R.H.; Gaaloul, W.; Hadj-Alouane, N.B.; Polakos, P. (2016, December). A demo of IoT healthcare application provisioning in hybrid cloud/fog environment. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing Technology and Science (CloudCom) (pp. 472–475). IEEE.

- Palanisamy, S.; Thangaraju, V.; Kandasamy, J.; Salau, A.O. Towards precision in IoT-based healthcare systems: a hybrid optimized framework for big data classification. Journal of Big Data 2025, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabha, P.; Chatterjee, K. Design and implementation of hybrid consensus mechanism for IoT based healthcare system security. International Journal of Information Technology 2022, 14, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyema, E.M.; Lilhore, U.K.; Saurabh, P.; Dalal, S.; Nwaeze, A.S.; Chijindu, A.T.; Simaiya, S. Evaluation of IoT-Enabled hybrid model for genome sequence analysis of patients in healthcare 4.0. Measurement: Sensors 2023, 26, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Singh, H.; Goyal, V.; Parah, S.A.; Wani, A.R. (2021). Big data based hybrid machine learning model for improving performance of medical Internet of Things data in healthcare systems. In Healthcare Paradigms in the Internet of Things Ecosystem (pp. 47–62). Academic Press.

- Naik, N.; Surendranath, N.; Raju, S.A.B.; Madduri, C.; Dasari, N.; Shukla, V.K.; Patil, V. Hybrid deep learning-enabled framework for enhancing security, data integrity, and operational performance in Healthcare Internet of Things (H-IoT) environments. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, B.; Guo, B.; Yang, J.; Peng, W. Combination of cloud computing and internet of things (IOT) in medical monitoring systems. International Journal of Hybrid Information Technology 2015, 8, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, P.; Rahmani, A.M.; Haj Seyyed Javadi, H. A medical monitoring scheme and health-medical service composition model in cloud-based IoT platform. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies 2019, 30, e3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Hajjej, F.; Ali, A.; Pasha, M.F.; Almomani, O. A novel hybrid trustworthy decentralized authentication and data preservation model for digital healthcare IoT based CPS. Sensors 2022, 22, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Park, E.; Cho, B.H.; Lee, K.S. (2018). Recent patient health monitoring platforms incorporating internet of things-enabled smart devices. International neurourology journal, 22(Suppl 2), S76.

- Thota, C.; Sundarasekar, R.; Manogaran, G.; MK, P. (2018). Centralized fog computing security platform for IoT and cloud in healthcare system. In Exploring the convergence of big data and the internet of things (pp. 141–154). IGI global.

- Catarinucci, L.; De Donno, D.; Mainetti, L.; Palano, L.; Patrono, L.; Stefanizzi, M.L.; Tarricone, L. An IoT-aware architecture for smart healthcare systems. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2015, 2, 515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, F.; Liu, D.; Zhao, P.; Kryvinska, N.; Abbas, S.; Rizwan, M. Trustworthy intrusion detection in e-healthcare systems. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9, 788347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, K.; Ramshankar, N.; Shathik, J.A.; Lavanya, R. Blockchain assisted cloud security and privacy preservation using hybridized encryption and deep learning mechanism in IoT-Healthcare application. Journal of Grid Computing 2023, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbagoury, B.M.; Vladareanu, L.; Vlădăreanu, V.; Salem, A.B.; Travediu, A.M.; Roushdy, M.I. A hybrid stacked CNN and residual feedback GMDH-LSTM deep learning model for stroke prediction applied on mobile AI smart hospital platform. Sensors 2023, 23, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abikoye, O.C.; Oladipupo, E.T.; Imoize, A.L.; Awotunde, J.B.; Lee, C.C.; Li, C.T. Securing critical user information over the internet of medical things platforms using a hybrid cryptography scheme. Future Internet 2023, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, M.P.; Bareja, L.; Gupta, M.; Malviya, A.; Dev, S.; Iqbal, M.A. (2025). Revolutionizing healthcare: data privacy based on novel approach in hybrid cloud networks. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 1–9.

- Kar, E.; Fakhimi, M.; Turner, C.; Eldabi, T. Hybrid simulation in healthcare: a systematic exploration of models, applications, and emerging trends. Journal of Simulation 2025, 19, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damery, S.; Jones, J.; Harrison, A.; Hinde, S.; Jolly, K. Technology-enabled hybrid cardiac rehabilitation: Qualitative study of healthcare professional and patient perspectives at three cardiac rehabilitation centres in England. PloS One 2025, 20, e0319619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, N.; Ghoodjani, E.; Majd, S.S.; Maleki, A.; Khamoushi, S. Evaluation and prioritization of artificial intelligence integrated blockchain factors in healthcare supply chain: A hybrid Decision Making Approach. Computer and Decision Making: An International Journal 2025, 2, 374–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Kumar, A. A blockchain based solution for efficient and secure healthcare management. International Journal of Critical Infrastructures 2025, 21, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, E.; Solaiman, E. (2025). EHSAN: Leveraging ChatGPT in a Hybrid Framework for Arabic Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis in Healthcare. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2508.02574.

- Adapa, C.S.R. Leveraging integrated master data management for enhanced healthcare decision-making. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2025, 15, 2397–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Park, G.T.; Shukla, A.K.; Kwon, B.; Kim, J.H.; Sung, E.S.; Kim, B.S. (2025). 3D Bioprinting-Assisted Engineering of Stem Cell-Laden Hybrid Biopatches With Distinct Geometric Patterns Considering the Mechanical Characteristics of Regular and Irregular Connective Tissues. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2502763.

- Kasralikar, P.; Polu, O.R.; Chamarthi, B.; Rupavath, R.V.S.S.B.; Patel, S.; Tumati, R. (2025). Blockchain for securing AI-driven healthcare systems: a systematic review and future research perspectives. Cureus, 17.

- Zahed, M.A.; Rana, S.S.; Faruk, O.; Islam, M.R.; Reza, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.Y. Self-Powered Wireless System for Monitoring Sweat Electrolytes in Personalized Healthcare Wearables. Advanced Functional Materials 2025, 35, 2421021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghanim, M.H.; Attar, H.H.; Rezaee, K.; Solyman, A.A. Medical diagnosis decision-making framework on the internet of medical things platform using hybrid learning. Wireless Networks 2024, 30, 6901–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | References | Technologies/Methodologies | Merits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | [17,26,54] | Cloud Computing, Big Data, Augmented Reality, Wearable Devices | Efficient data storage, enhances perception, patient alert systems | High memory requirements, costly AR devices, wearables not always standalone |

| 2017 | [8,15,122] | RFID, Body Sensor Networks, Open Systems IoT Reference Model (OSIRM) | Health history monitoring, long-distance data collection, precise activity differentiation | Expensive, vulnerable to security attacks, service duplication issues |

| 2018 | [6,10,33] | Consumer Security Index (CSI), Resource Preservation Net (RPN) Framework, Intelligent Medicine Box | Improves consumer security, optimized patient waiting times, timely medication notifications | Implementation delays, storage issues, potential incorrect drug dispensing |

| 2019 | [31,63,120] | Healthcare Monitoring System for Soldiers, Ambient Assisted Living, Blockchain Security Models | Tracking soldier’s location, resilient data storage, optimized daily activities | Battery drain, high cost, limited data modification options |

| 2020 | [64,65] | WSN Security Model, IoT-based Healthcare Monitoring Systems | Secures data collection, real-time health tracking | Data theft risks, expensive maintenance |

| 2021 | [125,126,127,128,129] | Smart Health Systems, e-Health Frameworks, mHealth | Effective for remote health management, better accessibility in emergencies | Simulation-based validation required, security concerns |

| 2022 | [129,130,131,133] | IoT-based Health Monitoring, Data Collection with IoT Devices | Enhances patient monitoring, supports real-time health data analysis | Connectivity issues, requires high security, high data storage needs |

| 2023 | [132,134,135] | Smart Hospitals with RFID, IoT, and Blockchain | Real-time location tracking of devices, secure data exchange | High setup costs, security vulnerabilities |

| 2024 | [136,137,138,140,161] | IoT-enabled Diagnostic Tools, Smart Medication Management | Improves diagnostic speed and accuracy, optimizes medication adherence | Limited scalability, dependency on reliable connectivity |

| 2025 | [141,142,150] | Blockchain for Interoperability, AI-powered IoT Healthcare | Provides transparency, secure data exchange, enhanced patient privacy | Energy consumption in consensus mechanisms, compliance with regulations (e.g.; GDPR, HIPAA) |

| Year | Application | Advantages | Limitations | Accessing Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Dropping Emergency Room Waiting Time [2,55,56] |

Use predictive analytics for flow of patients Monitor physiological data during emergency |

Scalability needs to be improved. increase energy consumption | Special sensors based on IoT, wireless sensor network MEDiSN |

| 2018 | Telehealth [30,59,61] |

Minimum time for separating messages Ensure wear ability and data quality Track bed-ridden patients |

Requires a high-quality security module, requires technical training, server problems can make virtual communication impossible |

Real-time monitoring, telemetric system. CyberMed |

| 2018 | Tracking of Information [7,71,72,106] |

Track patient information Continuous monitor human location |

Security of information, continuous Internet connections | RFID tag ZigBee, and GSM wireless technology Wireless body area networks (WBASNs) sensor |

| 2017 | Drug Management [32,33,34,60] |

Drug identification and monitoring of medication 10T-enabled smart pillboxes Give alerts for medication |

Interruption can cause problem | Wisepill technologies and Aeris wireless connection |

| 2018 | Food Management [35,36] |

Real-time food intake monitoring system Construct a smart dining table |

Need cost effective sensor system A Bayesian Network |

Novel 5-layer perceptron neural network Weighing sensor |

| 2016 | Glucose Level [37,38,80] |

Ensure the long-distance data transmission's stability and correctness. Keep track of blood glucose |

Need operator technique, exposure, environmental and patient factors 6LoWPAN protocol |

ZigBee wireless network, Bluetooth radio network IEEE 802.15.4 |

| 2014 | Electrocardiogram [39,40,41,42,83,84] |

Detect threshold parameters Transform of ECG signal Determine a certain form The P and T wave (QRS) wave group's position. |

Data stream mining and context awareness technologies MATLAB simulation |

CoAP/HTTP, MQTT, TLS/TCP, DTLS/UDP |

| 2012 | Blood Pressure (BP) [43,44,45,46] |

Real-time BP measurement | Continuous Internet connection Keep in Touch (KIT) blood pressure meter RFID |

NFC stands for Near-Field Communication |

| 2014 | Oxygen Saturation [47,48,49] |

Monitor blood oxygen saturation | Low power/low-cost pulse oximeter Realtime monitoring |

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) wearable pulse oximeter CoAP protocol |

| 2016 | Rehabilitation System [50,51,52,53,54] |

Provide rehabilitation exercise Rehabilitation training of hemiplegic patients |

Proper knowledge about training IOT sensors. |

Body Sensor Networks (BSN) |

| Platform | Consensus Mechanism | Throughput (TPS) | Latency | Permissioned | Smart Contracts | Suitability for Healthcare IoT | Key Challenges | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperledger Fabric | PBFT/RAFT | High (100s-1000s) | Low (secs) | Yes | Yes (Chaincode) | High | Complex setup, Steep learning curve | [73,81] |

| Ethereum (PoW) | Proof-of-Work (PoW) | Low (10-15) | High (mins) | No | Yes (Solidity) | Low | High gas fees, Low scalability, High energy consumption | [4,81] |

| Ethereum (PoS) | Proof-of-Stake (PoS) | Medium (10-100) | Medium | No | Yes (Solidity) | Medium | Evolving ecosystem, Past scalability concerns | [107] |

| IOTA | Tangle (DAG) | Very High | Low | No | Yes | High | Network maturity, Centralization concerns in Coordinator node | [120] |

| Quorum | QBFT/RAFT | High (100s) | Low | Yes | Yes (Solidity) | High | Enterprise-focused, Less community data than Fabric | [81] |

| Year | Technology | Contributions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) [7,8,9] |

Collect data on the user's living surroundings. Monitor the health condition and boost the power of IOT. Allows for pharmaceutical packing (iMedPack). |

High costs, interference issues, and certain signal problems |

| 2018 | Edge Computing [10,11,57,58] |

Calculate the average patient waiting time, length of stay (LOS), and resource consumption rate. Use wireless body area networks. and increases the power of IOT. Closed-loop processes keep the body in a state of equilibrium. Rural medicine, enhanced patient experience, and cost reductions |

Less scalable, lacks cloud awareness, and cannot do resource pooling |

| 2017 | Semantic [12,13,14] |

Provide data annotations. Enable XMPP, CoAP, and MQTT protocol communication. less scalable security level Provide Semantic Interoperability in 10T domain. |

Reduce scalability and flexibility, high level processing, lack data confidentiality technical problem and privacy |

| 2017 | Cloud Computing [15,16,17,18,57] |

E Patient records are stored electronically. Keep a vast database. Time spent waiting. Enforce regulations and forecast cloud data mobility for IOT enabled e-health. |

Relying on an internet connection, a lower degree of security, and a technological issue |

| 2016 | Big Data [1,20,21,29] |

During an emergency, organize disparate physiological data. The patient's data is completely protected. and personal. Remove unnecessary data and extract crucial information. |

Data quality, cyber security risk, compliance, and cost are all considerations. |

| 2012 | Computing on the Grid [22,23,24] |

Drug development Extends healthcare and private decision making. Provide infrastructure for medical and bioinformatical research. |

Lack of grid software and standards |

| 2018 | Augmented Reality [25,26,27,28] |

Train medical practitioners’ hand-eye coordination. Participants' sensation of presence is increased. technology, low performance level Make infrastructure available for medical and bioinformatics research. |

AR is expensive to deploy and develop, and it lacks security. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).