1. Introduction

Before we attempt to discuss or examine the “conditions” for productivity, it is necessary to consider the contexts under which productive efficiency (Farell, 1957) is attained. Without reducing it to simple quantitative measure of output efficiency, it would be germane if we assume something more pragmatic to describe its philosophy. If we consider productivity not merely as doing more, but beyond it, about doing what really matters, it would do more justice to the term. Six things must be brought to mind when defining conditions that support productivity, for conditions are necessary prerequisites to effective outcomes (Cohen, 1994). These are as follows:

Conscious choice of actions, to which is attached responsibility

Purpose, goal, and clarity of thought, to which purpose aligns clearly with actions, goals and values

Intentional stance, for no action becomes “productive” if it is not tied to clear intentions

Balance between the “will to act” and execution of actions. Freedom of thought is a necessary condition which depends on the decision to focus and align our attention to goals

All productive acts begin with a selection, which help engage our attention to the course of actions directed by the path chosen. Conscious selection and choice (of a path) is a higher-order decision-making function applicable to both human beings and AI agents (Farhadi, 2025), and

Emotional state, motivation, and temporal awareness, to do the right thing at the right time to help time and action converge to produce productive outcomes

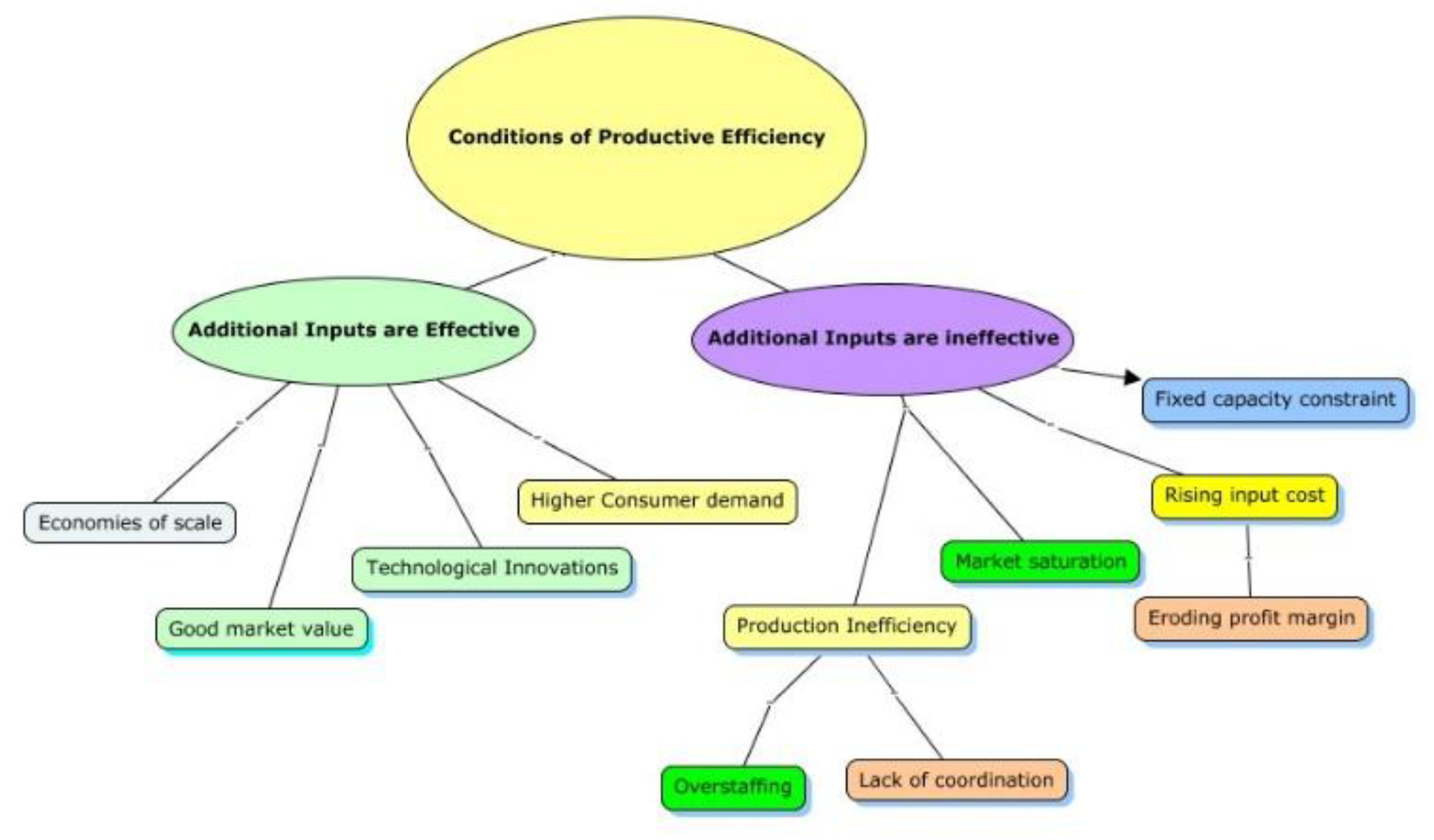

Conditions of productivity are more explicitly defined in production and manufacturing sectors of the economy (kaldor, 1968; Bernard et al 2009), as well as for effective teaching and learning outcomes for productive small groups (Cohen, 1994). Just as any scientific, e.g., physical, chemical or biological experiment becomes successful only under a given controlled conditions, to achieve higher productivity, it is necessary to define a specific set of conditions as well. Hence, there must exist certain conditions for achieving a desired rate of productivity. Thoughts on productivity direct our attention to changeable situations and settings that are conducive to support maximum efficiency. However, there are economic problems which one might face while measuring changes in productivity levels (Stigler, 1961) in order to determine the productive efficiency of a system. This is more or less relevant to “marginal productivity rate”, although this statement has some ambiguity, for productivity levels are average measures, whereas marginal productivity is incremental increase in output from increase in a unit of input.

Measuring incremental output from additional usage of inputs cannot actually assess

productive efficiency of a production system, in economic sense, but the concepts are correlated. The question is, how effective could be additional input usage to derive incremental outputs that has more “utility and value” to the producer? The answer relates to the Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns. Measuring productivity rate or changes in it requires some adjustments for data quality and technological variability. For example, Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is a good proxy for measuring productive functions, in terms of how efficiently systems turn inputs into outputs (Gatto, Liberto & Petraglia, 2011; Beveren, 2012). The overall idea of productive efficiency should touch on these core concepts (See

Figure 1 below):

That the product should be marketable and sellable

Have a cost which is lower than revenue/profit

Create market demand and have higher utility and value to customers, and

A product having just higher value to producer doesn’t make sense

Productivity measurement is also necessary to assess efficient use of resources. This is crucial, for changes in a specific set of conditions (i.e., including inputs) affect marginal productivity levels (Syverson, 2011). A pre-determined set of conditions may act as a priori preceding productivity of a firm, R&D, or a manufacturing unit (a microeconomic system).

But such a priori would be “theoretical” in context, without much value to a productive system, if it is not efficient in practice. Rather, the set of conditions that determine productive efficiency is determined as a result of a posteriori which is like deriving the logic of production requiring evidence from tested methods that yielded facts about such “specific conditions” promoting productivity. This explains the fundamental role of productive factors (Coccia, 2009) as well as of the conditions optimal for the theory of production (Stigler, 1961).

“Productivity is skilful practice which is to be valued… It’s important how consciously we chose to do in what we want to excel.”

Productivity can be sustained by mastery, not just legwork. In economic sense, productivity is seen as one of the prime variables governing economic activities related to manufacturing and industrial outputs (Tangen, 2005). It also constitutes as the key factor whose improvement contributes to competitive advantage of a firm or an enterprise. However, any increase or decrease in productivity level can only be ascertained if it is measured with reference to a standard. When compared with a standard reference to determine its increase or decrease, it becomes a relative concept. Although there are many measures of productivity (Gatto, Di Liberto & Petraglia, 2011), the Malmquist productivity index (Pastor and Lovell, 2005) seems apparently the best suited to measure industrial productivity across sectors. But our goal in this paper is not to debate on or invent any new measure of productivity nor discuss about different methods of measuring it. We are concerned less with how it is measured and more with the “conditions” that favour or support a desired level of productivity, both at the individual, collective and group level, or organisational level. Abrey and Smallwood (2014) reports that unsatisfactory, poor working conditions characterised by poor health and safety hazards constantly affect productivity of construction workers. This is also true for most industrial manufacturing sectors in developing countries as well, where, mass production aims for higher productivity rate under difficult conditions that the workers are made to face. It shall be noted that improvements in production environments not only boost employee morale, but contribute to higher productivity rate.

2. Principle Ideas of Productive Transformation

This paper aspires to add an important knowledge on productivity: pursuing heuristic search process for ideas of productive transformation of the mind. These ideas are helpful in creating conducive conditions for supporting or promoting organisational-level productivity among the workforces. According to the principles of productivity, there must exist certain ‘conditions’ conducive to production of things, products: e.g., knowledge, ideas, goods, services, etc. (Syverson, 2011). These conditions generally define the nature of “productiveness” of a system, which characterise the forms of productive outcomes. In this context, the “choice of action” is an important prerequisite to being productive. Our choices decide the future course of actions, for instance, whether we want to become more proactive, maintain the status quo, or do nothing. That is to say, to make things happen, a proactive state of motivation is necessary to sustain goal striving (Parker, Bindl and Strauss, 2010). We may call these as “productive choices” for actions. The forces acting on us to help us become more productive is the powerful influence of ideas, thoughts, and activities of others that inspire us. Besides these, strategic intelligence also guide us towards productivity. But it is, in essence, the decision of our “own will” that helps us to decide whether to become more productive, if we really want that to be so.

To undergo productive transformation, three things are categorically indispensable: IDEAS, INSPIRATION, and MEANS (resources) and METHODS (processes) of production. Discovery of new or more efficient means of production techniques lead to innovations in “conditions” that improve productivity. The discoveries have been the long process of gradual developments in production techniques, the history of which is abundant with rich examples. In modern context, however, if it is desired that we need to raise the productivity level of a firm, it would necessitate “specific conditions” be set upon the production processes, i.e., to bring about improvements in methods, and to enable more efficient technology adoption. It is also necessary to maintain effective communication channels to help design more effective processes and methods of production, and bring about certain improvements in working conditions (Segal et al, 2003), which has many sub-elements corresponding to workers’ benefits, optimal ambience and the nature of work culture (Clements-Croome, 2015; Hamed et al., 2024). These improve principles and morale, all of which mould together to determine productivity level of an individual in a firm or an organisation. Besides, improvements in methods lead to work efficiency as well (Aft, 2000).

Now, all these boil down to several outcomes defined by specific “conditions” for productivity: specific settings. Conditions are those under which output increases proportionately to inputs, or outputs increase but there is observed decrease in input. Conditions may also characterise decrease in both outputs and inputs but the magnitude of decrease in input is larger than that of output, and vice versa. Every firm’s nightmare is to control production function. Managers often strive hard to increase production with fewer inputs to achieve greater efficiency, or achieve more output with a reduction in input (Tangen, 2005). It is also a desirable condition to achieve more output from same given quantity of input, which also increases the ‘productive efficiency’ of a firm (Tangen, 2005). Many factors may bring these positive productive changes in a firm, and there exists many types of productivity measurements owing to the complexity of measuring different kinds of or different subsets of outputs from a related subcategories of inputs.

More than that, conditions can also become conducive to productivity when innovations occur in methods and processes and operations, which help increase outputs from same given amount of inputs. Besides, firms often adopt more advanced technologies and machineries which add to their efficiencies. Now, all it depends on is the strategic choice of actions and management decision-making that govern productivity of manufacturing firms (Baum & Wally, 2003; Teryima & Anna, 2016). In this respect, factors like technology, logistics, government policies and social knowledge of products are, in essence, exogenous variables, whereas human effort is considered as an endogenous variable (determinant) of successful, productive outcomes.

3. Choice of Actions

Outcomes depend on actions. Without any action there’s no outcome, and without being productive, it would be unreasonable to think about results. Organisations excel in managing actions that make them productive. They manage people, processes and activities to obtain results, as reflected in the words of Drucker (2012); i.e., managers manage actions, and they manage for results. The wisdom in choosing strategic course of actions can result in increased “managed” productivity. It is not just action ‘alone’ that defines it—rather, in choosing an action, one must decide by virtue of values while making informed choices. In choosing actions, it’s necessary to take aid of the power of reflection as well.

Productive, positive outcomes and results are unequivocally reliant on the choice of actions. It depends, rather it varies substantially on how the agents choose a course of action, i.e., what path do they take, which invariably determines the outcomes often modulated by contingencies (Garud, Kumaraswamy & Karnøe, 2010). In this respect, according to Garud, Kumaraswamy & Karnøe (2010), contingencies are emergent contexts for action. Besides, both productivity and productivity-related outcome variations have been observed and reviewed by Hoffman & Stanton (2024) among workers in the same roles, implying the important role of training and technology adoption and usage. However, given all these rudiments, the “principles of effect” are insured in actions. Now, there could be innumerable reasons for each of us to become productive, for we choose our paths in full view of the probable outcomes that may be conceived from acting and behaving in most optimal manner. Often, we choose wrongly or make bad choices with resultant poor or suboptimal outcomes. Sometimes, even though we make correct choices, the results we obtain seem unfavourable. It is for the reason that the “principle of action is obedient to the laws of its own nature.” By this, we mean that there are specific reasons for becoming productive, but those “reasons” vary in degrees of importance to the agent or the organisation to which they are obedient and dutiful.

Efficient methods expand growth, whereas inefficient methods limit productivity as well as growth.

Here, we call upon the ‘noetic sphere’ of reasons to consider the importance of specific actions that we choose, based upon which outcomes take shape. Therefore, our choice of actions determine the “conditions” of productivity. This can provide us with formal explanations of the fundamental concept of the metaphysics of productivity, and productive actions. Productivity can thus be stated as:

“…productivity is a tool which can be mastered with adequate practice and effort.”

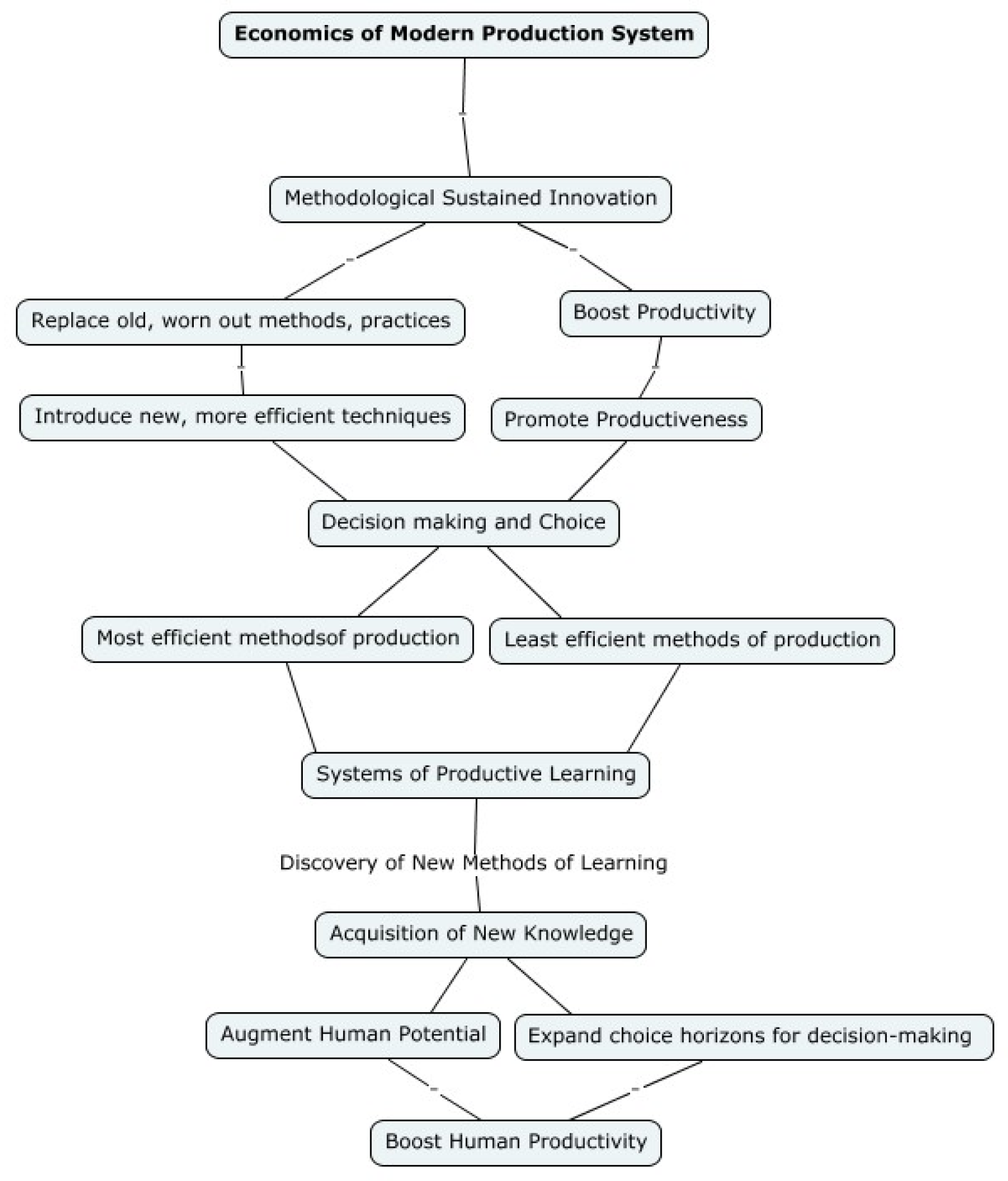

Take for example the modern systems of production (see

Figure 2). New methods, far more efficient and innovative ones are being continuously developed that replaces the old ones and help boost our productivity level and productiveness. Similarly, with the discovery of new methods of learning, new knowledge is obtained to augment human capabilities that expand our horizons and which offer us with new prospects, choices, and options. Here, once again, we need to

choose. The choice is

between most efficient modes and least effective ones that constrain and limit our productive capabilities. The diagram below (See

Figure 2) depicts the dynamicity of a modern economic system of production which specifies the conditions of efficiency employed to boost human (

workforce) productivity. In this diagram, what is shown is an elaboration of how the most efficient methods

enhance capabilities and

expand possibilities, and how the least effective methods

constrain capabilities and

limit productivity.

The choice of a method also determines the results to be obtained from applying it. In choosing well lies the virtue of merit. The virtues of a method lie within the design process, the variables included that define how it should work, and how far it would be successful and effective in deriving results. Hence, one may ask, in what respect a particular method of working is more effective than others. The most useful division of this is to impart it with value. Value is embedded in choice of actions—, in the act of choosing. Methodological choice of actions depends on the decision making ability of an agent who makes optimal choices in executing actions. It results in the cultivation of efficiency. Efficient methods augment both human and machine productivity. They augment the influence of actions, whereas, inefficient and useless methods decrease productivity and lead to waste of energy. From these, we can derive a “maxim” or axiom of productivity:

Axiom 1: The efficient means of actions are sufficient to create conditions optimal for productive equilibrium.

The axiom of productivity constructed above reflects on the philosophy and metaphysics of productivity. It points to the direction of methodological way of doing things that are effective to establish a certain state of stability and steadiness. In other words, to attain conditions for balanced productivity, actions that are efficient are sufficient for an ideal state of economic affair. Tis orients us towards productivity, and efficient means of becoming productive.

4. Orientation to Productivity

We are discussing about conditions for productivity. It appears to be an inadequate explanation of the principle of productivity without reference to orientation of the mind to productive environments. Massoudi & Hamdi (2017) note that employee productivity is affected by work environments, with better ambience stimulating and supporting productive activities. It is thought of as to provide the reference relative to which the mind can orient itself towards attaining efficiency. Fruckter (2005) had previously showed an improved level of workforce engagement in interactive workspaces through adoption of innovative patented technology. In this respect, noetic orientation to such stimulating, productive environments for productivity gain and enhancement would require the mind to acquire the knowledge and wisdom necessary to become efficient and productive. Indeed, we must mention the various modes of individual productivity—for it is not a restrictive factor and neither should it constrain our understanding on a narrow domain of activity.

Productivity is a dynamic function, and for any productive system, there are certain principles that apply to it. The rate of productivity fluctuates with variances in different factors that contribute to it. For example, productivity in new product development saw decline in the past as Cooper & Edgett (2008) indicated in their study. Now, we are noticing improved productivity in new product development owing to deeper penetration of AI tools of automation, widely being adopted and applied to the design and development (R&D), and production of more innovative goods. Indeed, it matters what things are being produced, how they are produced, and by what rate something is produced with more efficiency and accuracy. But where’s the need for a principle of productivity? There is a definite need for it to provide the foundation for a physical description of noetic productivity, take for example, but without restricting ourselves to this mode alone. For any intellectual mode of productive activity aimed towards attaining noetic outcomes by means of applying cognitive machineries of the mind (or machines), it requires a rational noetic principle valid for any productive system, natural or automated (artificial). But it must be considered as a priori that most human activities tend to be relatively non-invariant compared to machine activities. So, how can a single principle be adopted to explain both? Back in the mid past century, Georgopoulos et al. (1957) determined the effective role of ‘rational aspects’ in determining productive behavior, and showed that both assistive and inhibitory forces affected productivity function. This was apparent in their path-goal approach to understanding human productivity, where productivity is perceived as a path to attaining personal goals.

Given likewise that the individual pool of knowledge is ever changing—or rather increasing, and each individual’s knowledge pool is slightly different from all others—for not every one of us have similar knowledge pools, nor expertise, experience and ability, it matters when it comes to the domain of noetic productivity that encompasses creativity, intuitions, insights, and imaginations. For example, an agent ’s pool of knowledge at time cannot be at rest with respect to other agents in an organisational setting. This could be mathematically expressed as follows: . Hence, a general orientation to a standard model of reference as a mark of equivalence is necessary for streamlining individual effort at a collective, organisational level. Mathematically, such an equivalence can be represented as . Hence arise the need for training, practice, and orientation programs. All these help create a “culture” of productive practice. This culture of productivity at the individual and organisational level is possible when agents adopt efficient practices, routines that tend to augment overall productiveness. This we call “orientation” to productivity. In the next section, we apply a simple mathematical model of productivity function to examine and understand the conditions that act as promoters of productivity, and practical tactics that can be modelled to explain how agents can augment their efficiency towards increased productiveness. Hence, several key points can be enumerated to help explain how one can become productive, which are as follows:

Adopt productive practices that increase your efficiency level

Practiceofproductivelearning(Lillejord&Dysthe,2008;Lave,2009)isanecessarysteptowardsgeneralisationoftheconceptsofheightenedproductivity

Attaingreatestpossibleexpertiseinyourdomain

Movewithinacircleofknowledgeandproductivity

Beinastateofdynamiclearningmode(Lave,2009)

Plottherelativemotionoftheoutcomeofproductivepracticeandlearning

Createnewworksthatdefineanewcultureofdynamicpracticeoflearning(Conner&Clawson,2004)forproductivity

Adoptanimmersivevirtualecosystemofcoordinatedlearning(Dedeetal.,2017)toachievehighergoalsbymeansofhigherproductivityastheoutcomeoflearning

Overcomenoetic(intellectual)inertia,and

Engageyourmindincreativethinking.

In organisational context, various exogenous and endogenous factors promote productivity growth, as for example, optimal rate of R&D investment can stimulate productivity growth in manufacturing firms, as noted by Coccia (2009). According to Cooper & Edgett (2008), taking a more holistic approach to product innovation and building production metrics, team accountability, continuous learning and facilitating organisation-wide information sharing will stimulate new product development and productivity growth. In the next section, we shall discuss the full implications of the foregoing analytical study which we have undertaken thereof in support of productivity growth. Productivity growth is the primary theme of this research, let’s not forget this, as we discuss the various means—the efficient ones of course, to expound upon the strategic techniques and methods that one could adopt to boost productivity level and expand the productive capabilities of an individual or a unit. It also explains how the choice of actions could have effect on the outcomes of productive endeavors.

5. Discussion

In this research, we sought the root of an idea that concerns the conditions conducive to higher level of productiveness of human agents. Productivity is practically marked by expression of intention exhibited by actions of an agent. Ideas serve the purpose and intention to do and become active, and hence, productive thinking is an important “noetic component” of productivity (Chatterjee, 2024; Chatterjee & Samanta, 2025). The conditions of higher efficiency and throughput are met when agents choose actively and make optimal decisions that satisfy actions according to certain rules (instructions), which, nevertheless, fulfill the conditions congenial to such heightened states.

5.1. Graphic Depiction of the Ten Principles of Productive Expertise

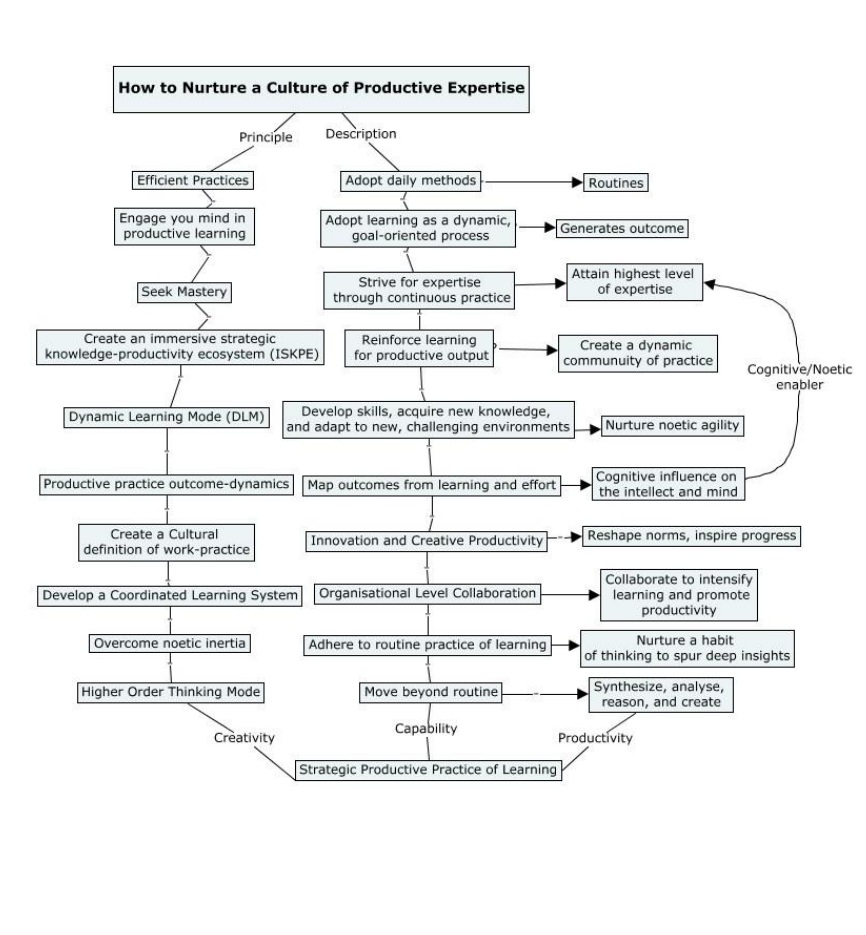

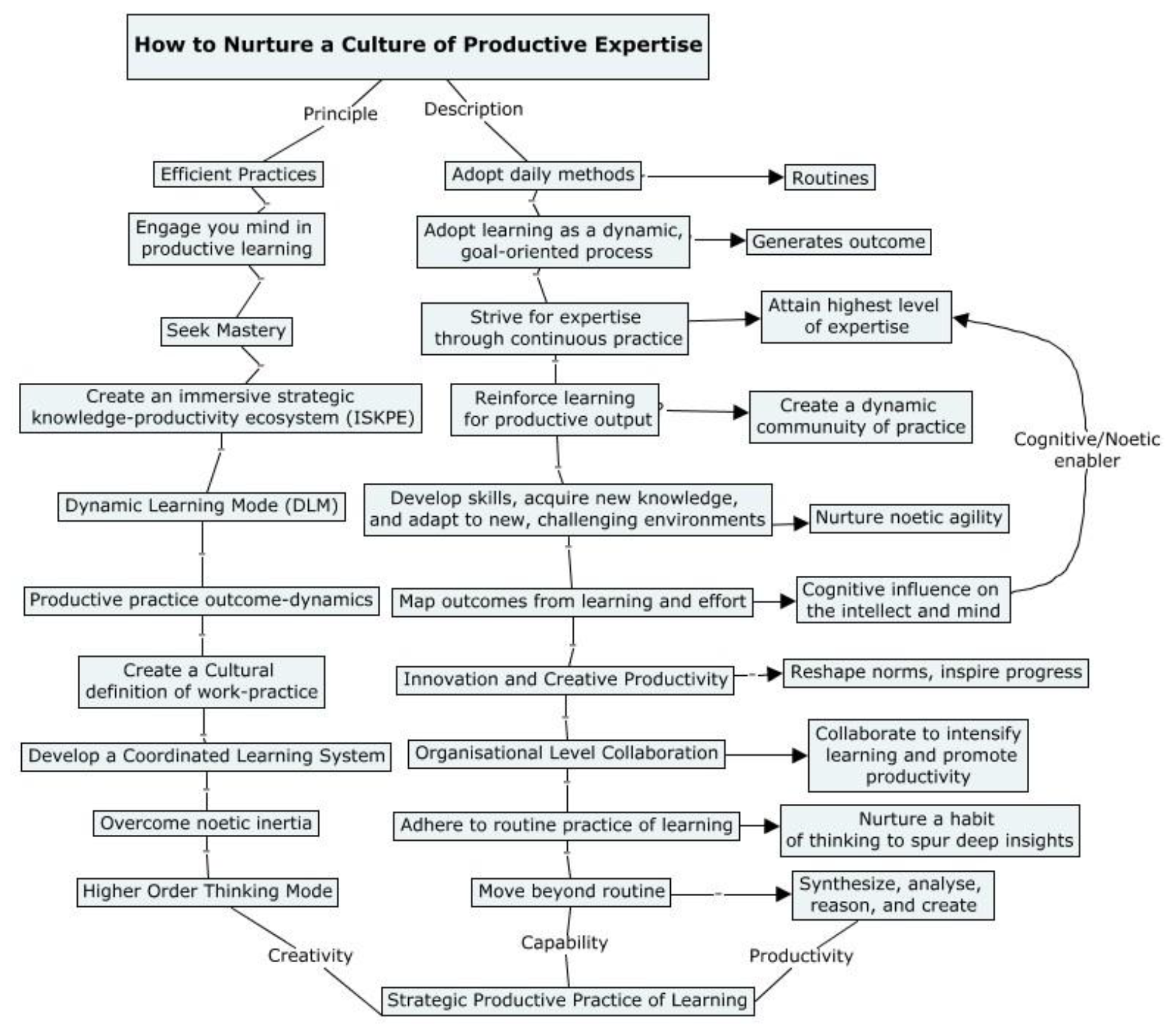

This base diagram (see

Figure 3 below) represents a contextual basis for nurturing a culture of “productive expertise,” based upon the Ten Edicts as mentioned above in

Section 3.

First, the aims and objectives of a productive endeavor should be made clear with greatest possible clarity. Random assertions about productivity shouldn’t be entertained, for they diminish the results of the generality of actions aimed towards enhancing it. The goal is to express the nature of work in terms of aims and final results, which must be met by committing a certain amount of effort that expresses the productiveness of an active agent.

5.2. Immersive Strategic Knowledge Productivity Ecosystem: ISKPE

To nurture a culture of productive expertise, several conditions are absolutely essential as principles to follow. These would most likely improve our productive efficiency in work and practice. Efficient practice should involve the mind in getting engaged in productive learning. Mastery can be attained by higher order learning in dynamic modes with the help of a coordinated learning system powered by today’s most advanced technologies, including AI. It will help overcome any noetic inertia from the part of the learner and aid the learner in nurturing an immersive strategic knowledge productivity ecosystem (ISKPE). The aim is to create conditions that promote creativity, productivity, and cultivate capabilities, which can be attained through strategic productive practice of learning. The learner must adopt an efficient routine as part of a daily methodological practice of learning to create conditions of optimal productivity. For this to happen, it is better for a practitioner or an employee to adopt learning as a dynamic, goal-oriented process. Through continuous practice of learning, agents can strive for expertise, reinforce learning for productive outcomes, develop skills, acquire new knowledge, or adapt to new emerging and challenging environments with much ease. Furthermore, to attain highest levels of expertise, continuous practice of productivity is a must.

For every learner to make learning effective, it is necessary to map outcome from the effort thus made. Organisational level collaboration and cooperation further help in moving beyond a fixed culture of productivity to help create a dynamic community of practice. This will help develop individual noetic agility necessary in performing complex tasks, thus proving itself as a noetic enabler. Progress can further be inspired by reshaping norms and adjusting to prevailing conditions and accepting challenges as conditions to achieving higher success. The cognitive influences on the mind and the intellect which noetics is primarily concerned with, thus having its effects felt on the outcomes from productive efforts. Which means that the science of the intellect (

noetics) plays a positive role in augmenting productivity levels of the agents by intensifying learning to promote positive outcomes. While moving beyond capabilities, it is also necessary for active agents to synthesise, analyse, reason, and create a new order of effects conducive to higher productivity.

Figure 3 above exactly maps these factors to help shape the culture of strategic productive practice, which is much on demand in today’s organisational context.

6. Conclusions

The significance of this study is restricted to analysing the conditions of productivity, and conditions that help increase productivity levels of individuals and firms. We did not define any new framework nor any innovative principles of productivity, but at its core, our attempt has been one that discusses positive settings and circumstances that seem highly conducive to promotion of productivity. We have outlined 10 edicts of productivity that people may find convenient and useful to their practice. The research combines a good depth of knowledge in this field discussing the secrets of higher productivity, which is an aim for most companies that are in the business of production and manufacturing of goods. Though we didn’t discuss any new framework, we have, in fact, created a “productive framework” for analysing the nature of human productivity.

Acknowledgments

The author extends his gratitude to the V.S. Krishna Central Library, Andhra University for providing access to conduct this research.

References

- Abrey, M., & Smallwood, J. J. (2014). The effects of unsatisfactory working conditions on productivity in the construction industry. Procedia Engineering, 85, 3-9. [CrossRef]

- Aft, L. S. (2000). Work measurement and methods improvement. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ashkan Farhadi,"Can AI Ever Become Conscious?," Journal of Advances in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 141-153, 2025. doi: 10.18178/JAAI.2025.3.2.141-153. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2009). Products and productivity. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 111(4), 681-709.

- Van Beveren, I. (2012). Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. Journal of economic surveys, 26(1), 98-128.

- Chatterjee, S., & Samanta, M. (2025). Noetic Capital and the Economics of Productivity (No. 125071). University Library of Munich, Germany.

- Chatterjee, S. (2024). The Noetics of Learning and Productivity: Quantum Noetic Metaphysics (QNM). Available at SSRN 4965732.

- Clements-Croome, D. (2015). Creative and productive workplaces: a review. Intelligent Buildings International, 7(4), 164-183. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. (2009). What is the optimal rate of R&D investment to maximize productivity growth?. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76(3), 433-446. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of educational research, 64(1), 1-35.

- Conner, M. L., & Clawson, J. G. (Eds.). (2004). Creating a learning culture: Strategy, technology, and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Cooper, R. G., & Edgett, S. J. (2008). Maximizing productivity in product innovation. Research-Technology Management, 51(2), 47-58.

- Dede, C., Grotzer, T. A., Kamarainen, A., & Metcalf, S. (2017). EcoXPT: Designing for deeper learning through experimentation in an immersive virtual ecosystem. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 166-178.

- Del Gatto, M., Di Liberto, A., & Petraglia, C. (2011). Measuring productivity. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(5), 952-1008.

- Drucker, P. (2012). Managing for results. Routledge.

- Farrell, M. J. (1957). The measurement of productive efficiency. Journal of the royal statistical society series a: statistics in society, 120(3), 253-281.

- Fruchter, R. Degrees of engagement in interactive workspaces. AI & Soc 19, 8–21 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation?. Journal of management studies, 47(4), 760-774.

- Georgopoulos, B. S., Mahoney, G. M., & Jones Jr, N. W. (1957). A path-goal approach to productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 41(6), 345.

- Hamed, S. A., Hussain, M. R. M., Jani, H. H. M., Sabri, S. S. S., & Rusli, N. (2024). The Influence of Physical Workplace Environment (PWE) for A Healthy Culture of Employees. Journal of Health and Quality of Life, 2(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Hanna Massoudi, A., & Salah Aldin Hamdi, S. (2017). The Consequence of work environment on Employees Productivity. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 19(1), 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M., & Stanton, C. T. (2024). People, practices, and productivity: A review of new advances in personnel economics.

- Kaldor, N. (1968). Productivity and growth in manufacturing industry: a reply. Economica, 35(140), 385-391. [CrossRef]

- Lave, J. (2009). The practice of learning. In Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 208-216). Routledge.

- Lillejord, S. L., & Dysthe, O. (2008). Productive learning practice–a theoretical discussion based on two cases. Journal of Education and Work, 21(1), 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of management, 36(4), 827-856. [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J. T., & Lovell, C. K. (2005). A global Malmquist productivity index. Economics letters, 88(2), 266-271. [CrossRef]

- Robert Baum, J., & Wally, S. (2003). Strategic decision speed and firm performance. Strategic management journal, 24(11), 1107-1129. [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G. J. (1961). Economic problems in measuring changes in productivity. In Output, input, and productivity measurement (pp. 47-78). Princeton University Press.

- Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity?. Journal of Economic literature, 49(2), 326-365.

- Teryima, S. J., & Anna, U. V. (2016). Perception management: a strategy for effective decision making and productive managerial performance in business organizations: a survey of selected manufacturing firms in Nigeria. Journal of Business and Economics, 7(1), 163-181.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).