Submitted:

14 September 2025

Posted:

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

2.1. Protein Structures

2.2. Ligand Preparation

2.3. Docking Protocol

ADMET

3. Results and Discussion

- Achieve multi-target binding across several human interleukins.

- Improve pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties.

- Reduce predicted toxicity relative to the parent compounds.

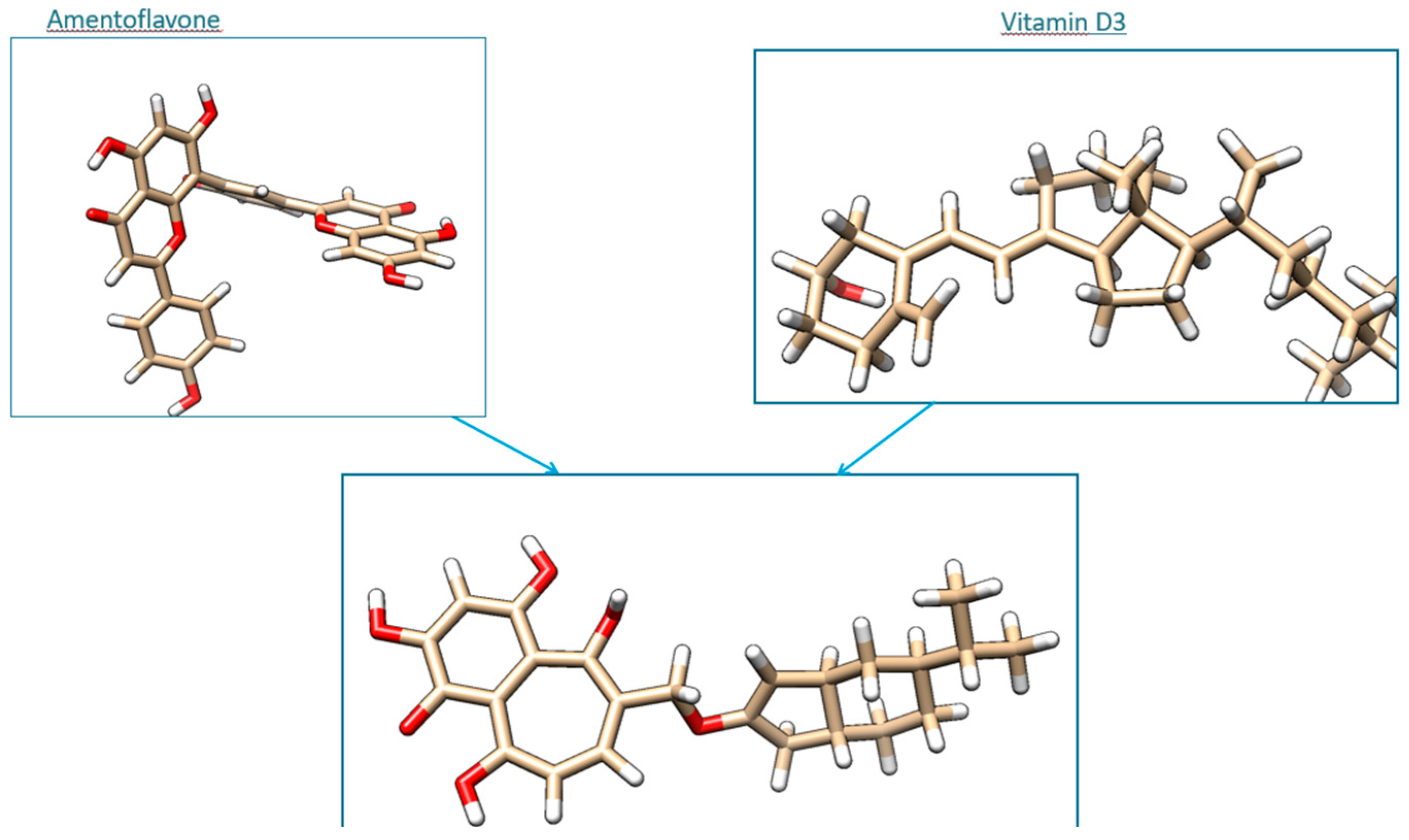

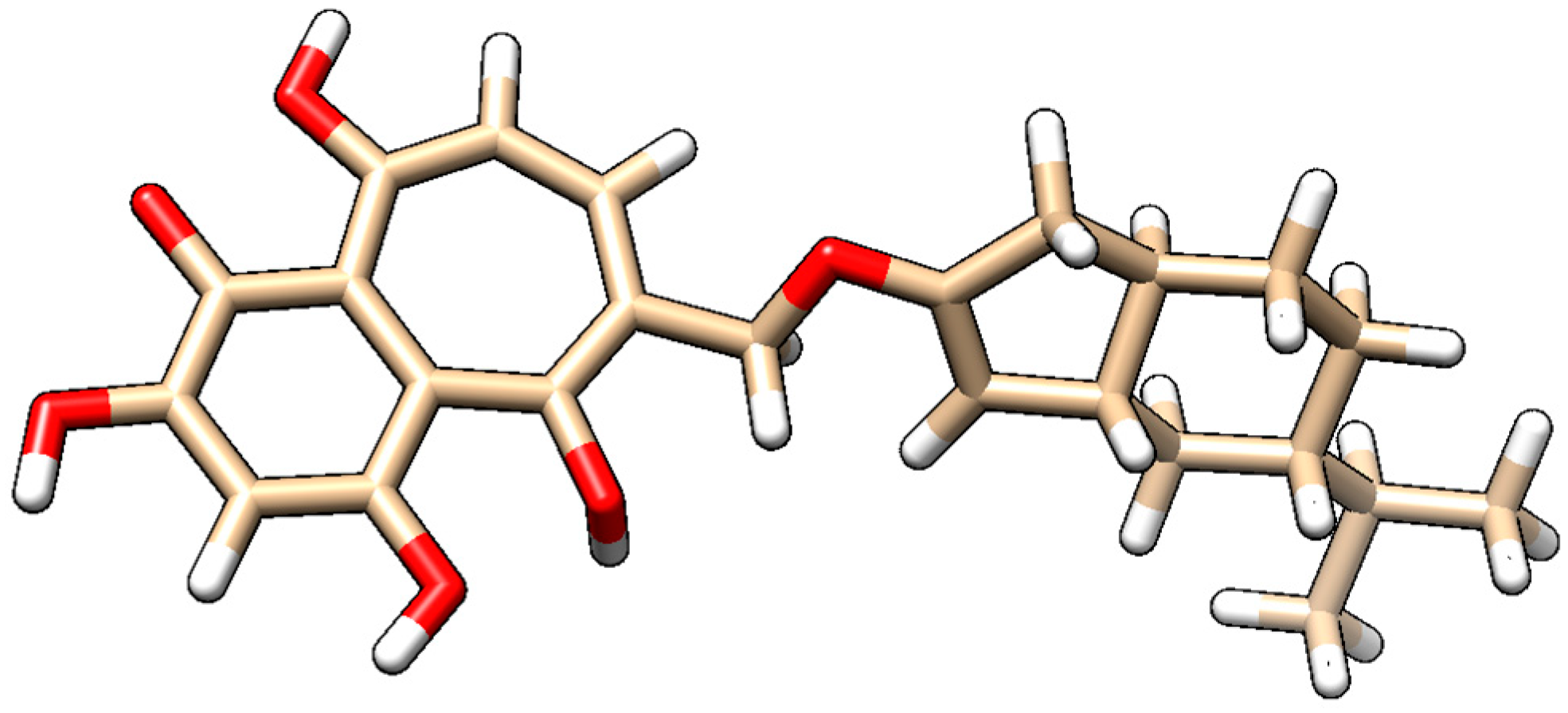

- Steroid-derived core: The cyclic backbone mimics the sterol scaffold of vitamin D3, providing a hydrophobic, rigid structure favorable for interaction with protein targets and cellular membranes.

- Flavonoid-derived fragment: The aromatic portion features hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, characteristic of amentoflavone, allowing hydrogen bonding, π–π interactions, and enhanced polarity.

- Linkage: A methylene-oxygen bridge covalently connects the two domains, preserving the integrity and independent functionality of each scaffold.

- Achieve multi-target binding across several human interleukins.

- Improve pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties.

- Reduce predicted toxicity relative to the parent compounds.

- A – Absorption: How a drug enters the bloodstream.

- D – Distribution: How the drug spreads through tissues and organs.

- M – Metabolism: How the body chemically modifies the drug.

- E – Excretion: How the drug or its metabolites are eliminated from the body.

- T – Toxicity: The potential harmful effects of the drug on the body.

Docking Analysis

Conclusions from Docking Results

- Binding Potency – Amentoflavone: Exhibits the strongest affinities across all tested interleukins (–7.4 to –10.2 kcal/mol), likely due to extensive hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic interactions.

- Binding Potency – Vitamin D3: Shows weaker binding (–6.1 to –7.9 kcal/mol), primarily through hydrophobic contacts, with fewer stabilizing polar interactions.

- Binding Potency – Hybrid: Displays intermediate affinities (–7.2 to –8.8 kcal/mol), combining Amentoflavone’s hydrogen-bonding capability with Vitamin D3’s hydrophobic character.

- Interleukin-Specific Trends: IL-12 and IL-17A exhibit the strongest binding for both Amentoflavone and the Hybrid molecule, whereas IL-4 shows minimal discrimination among the three molecules.

- Molecular Design Implications: The Hybrid molecule offers potential for multi-target interleukin modulation; further residue-level analysis is recommended to identify critical interaction hotspots.

- Overall Ranking: Amentoflavone > Hybrid > Vitamin D3, highlighting Amentoflavone as the primary candidate for interleukin modulation.

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

References

- Mizel, S. B. (1989). The interleukins 1. The FASEB journal, 3(12), 2379-2388.

- Kaiser, P.; Rothwell, L.; Avery, S.; Balu, S. Evolution of the interleukins. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2004, 28, 375–394. [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C. A., & Mier, J. W. (1986). Interleukins. Annual review of medicine, 37, 173-178.

- Strober, W., & James, S. P. (1988). The interleukins. Pediatric research, 24(5), 549-557.

- Chung, K.F. Targeting the interleukin pathway in the treatment of asthma. Lancet 2015, 386, 1086–1096. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P. M. (2019). Anticytokine agents: targeting interleukin signaling pathways for the treatment of atherothrombosis. Circulation research, 124(3), 437-450.

- Kim, H.K.; Son, K.H.; Chang, H.W.; Kang, S.S.; Kim, H.P. Amentoflavone, a plant biflavone: A new potential anti-inflammatory agent. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 1998, 21, 406–410. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Shan, M.; Chen, P.; Ding, A.; Li, S.F.Y. A Review on the Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Pharmacokinetics of Amentoflavone, a Naturally-Occurring Biflavonoid. Molecules 2017, 22, 299. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Tang, N.; Lai, X.; Zhang, J.; Wen, W.; Li, X.; Li, A.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. Insights Into Amentoflavone: A Natural Multifunctional Biflavonoid. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 768708. [CrossRef]

- Di Rosa, M.; Malaguarnera, M.; Nicoletti, F.; Malaguarnera, L. Vitamin D3: A helpful immuno-modulator. Immunology 2011, 134, 123–139. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Meza, M.R.; Ruiz-Ballesteros, A.I.; de la Cruz-Mosso, U. Functional effects of vitamin D: From nutrient to immunomodulator. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 3042–3062. [CrossRef]

- Adorini, L. Immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D receptor ligands in autoimmune diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002, 2, 1017–1028. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Q.; Mao, S.; Wu, W. Evaluation on absorption risks of amentoflavone after oral administration in rats. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2021, 42, 435–443. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, T.; Niu, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. Facile Fabrication of an Amentoflavone-Loaded Micelle System for Oral Delivery To Improve Bioavailability and Hypoglycemic Effects in KKAy Mice. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 12904–12913. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.A.; Mirshafiey, A.; Vahedi, H.; Hemmasi, G.; Khameneh, A.M.N.; Parastouei, K.; Saboor-Yaraghi, A.A. Immunoregulation of Inflammatory and Inhibitory Cytokines by VitaminD3 in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Scand. J. Immunol. 2017, 85, 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Guha, C.; Osawa, M.; Werner, P.A.; Galbraith, R.M.; Paddock, G.V. Regulation of human Gc (vitamin D — binding) protein levels: Hormonal and cytokine control of gene expression in vitro. Hepatology 1995, 21, 1675–1681. [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.S.; Badshah, Y.; Shabbir, M.; Rafiq, M. Molecular Docking Using Chimera and Autodock Vina Software for Nonbioinformaticians. JMIR Bioinform. Biotechnol. 2020, 1, e14232. [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R. P., & Rohane, S. H. (2021). Role of autodock vina in PyRx molecular docking. Asian Journal of Research in Chemistry, 14(2), 132-134.

- Dallakyan, S.; Olson, A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with pyrx. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1263, 243–250.

- Viegas-Junior, C.; Danuello, A.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Barreiro, E.J.; Fraga, C.A.M. Molecular Hybridization: A Useful Tool in the Design of New Drug Prototypes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1829–1852. [CrossRef]

- Bosquesi, P. L., Melo, T. R. F., Vizioli, E. O., Santos, J. L. D., & Chung, M. C. (2011). Anti-inflamm.

- Norinder, U.; Bergström, C.A.S. Prediction of ADMET Properties. ChemMedChem 2006, 1, 920–937. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, B.; Abed, S.N.; Al-Attraqchi, O.; Kuche, K.; Tekade, R.K. (2018). Computer-aided prediction of pharmacokinetic (ADMET) properties. In Dosage form design parameters (pp. 731-755). Academic Press.

- Dearden, J. C. (2007). In silico prediction of ADMET properties: how far have we come?. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 3(5), 635-639.

| Interleukin (PDB) | Amentoflavone (kcal/mol) | Vitamin D3 (kcal/mol) | Hybrid (kcal/mol) |

| IL-6 (1ALU) | –8.2 | –6.4 | –7.2 |

| IL-12 (1F45) | –10.2 | –7.0 | –8.8 |

| IL-8 (1IKL) | –7.8 | –6.1 | –7.3 |

| IL-2 (1M47) | –7.4 | –6.4 | –7.3 |

| IL-17A (4HR9) | –9.5 | –7.8 | –8.8 |

| IL-11 (6O4O) | –9.1 | –7.3 | –7.8 |

| IL-4 (8A4F) | –8.1 | –7.9 | –7.8 |

| IL-1β (9ILB) | –8.8 | –6.9 | –7.5 |

| IL-1β site (8C3U) | –8.4 | –6.8 | –7.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).