Submitted:

11 September 2025

Posted:

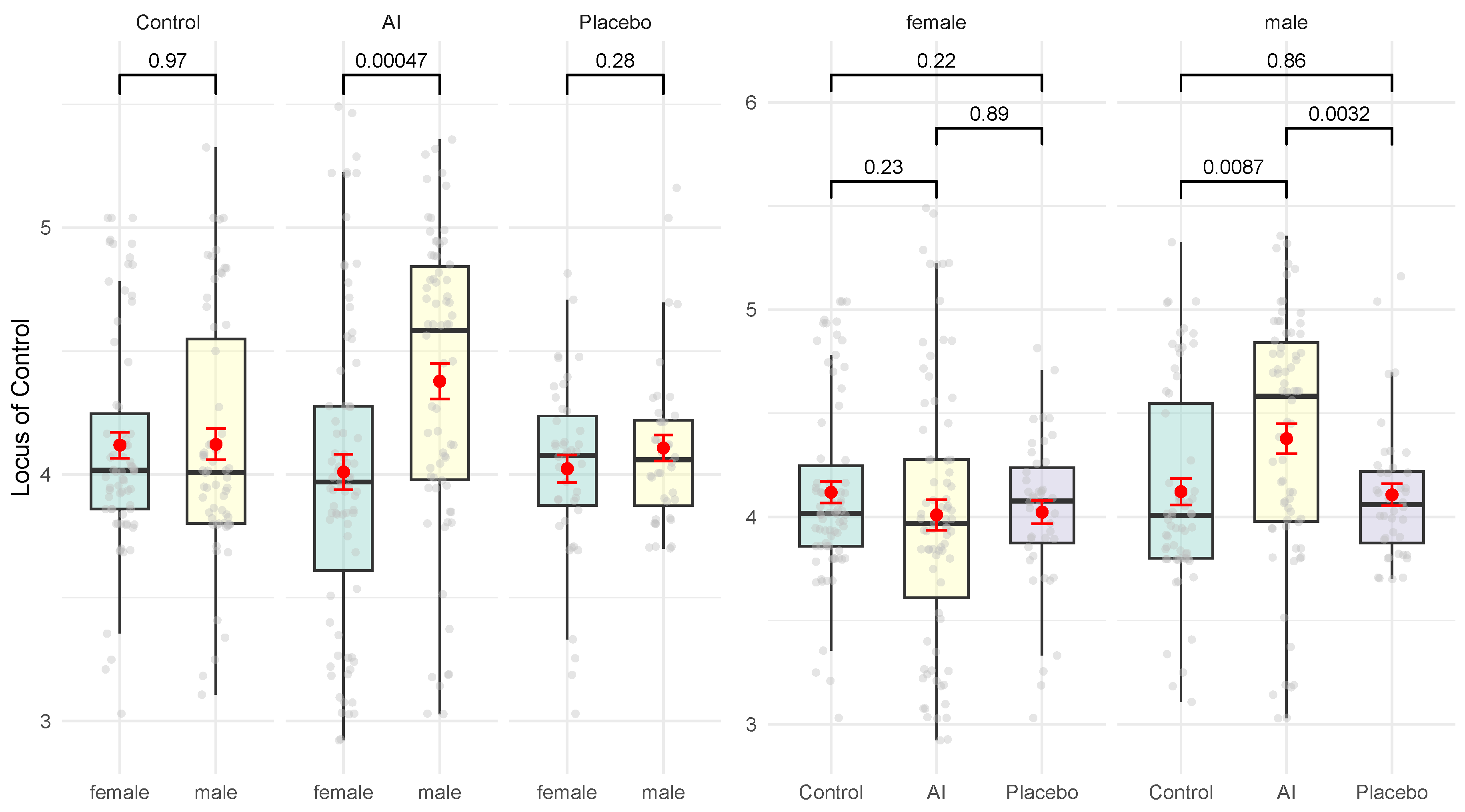

15 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Econometric Model

2.3. Arguments of Gender as a Proxy for Social Class

2.4. Arguments of Possessing a Car or More as a Proxy for Social Classes

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Balance Ckeck

3.2. Exploratory Factory Analysis for Perceived Behavioral Control

3.3. Main Results and Robustness Checks

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| AI Revolution | Control | Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| When you imagine the labor market in the next 10 to 15 years, which professions, from doctors and lawyers to drivers and artists, do you believe will be mostly carried out by artificial intelligence rather than by humans? | Who is your favorite and least favorite artist, and why? | What if a computer could understand what your body feels, such as pain or illness, simply by scanning you, without needles or surgery? |

| Historians speak of the Industrial and Digital Revolutions as moments that completely transformed society. On a scale from 1 to 10, how likely is it that the changes brought by AI will represent a transformation just as significant, or even greater, in our lives? | What is your favorite and least favorite sport (football, basketball, tennis, …) and why? | We have mapped the moon, but what about the ocean floor? What would it take to explore the depths of the oceans as easily as we explore a new city? |

| Thinking about your daily life, how likely do you find the scenario where major personal decisions—such as managing your health, planning your finances, or even choosing a life partner—are primarily guided by AI recommendations? | Between Bukavu and Goma, which city is more populated? What is the approximate population of these cities? | What if you could have perfect Internet connection anywhere on Earth—on a mountain, in the middle of the ocean, or in a rainforest—without cables or relay antennas? |

| Considering the skills needed for the future, how concerned are you that the education and professional training received today will become obsolete due to the rapid advancement of AI systems? | Talk about your favorite and least favorite leisure activity | What if you could travel anywhere in the world in less than two hours? |

| As AI becomes integrated into our economy and society, do you think this change is something we can control and shape, or rather an inevitable force to which we must simply adapt? | What is your favorite and least favorite meal, and why? | What if we could grow any kind of food, anywhere, in any season, without needing a large farm or perfect weather? |

| Imagine a future where AI manages critical infrastructures such as power grids, traffic systems, and supply chains. How much confidence do you have in our current social and legal systems to deal with the consequences if these AI systems make large-scale mistakes? | Who is your favorite African person, from the one you like most to the one you like least | What if you could have a smooth and natural conversation with anyone on the planet, in real time, without knowing their language? |

| When you consider the current pace of technological change, does the idea of a world fundamentally reshaped by AI seem to you like a distant science-fiction possibility, or an urgent reality that is already unfolding? | Tell us about a “crazy experience” you have lived through | What if you could learn a complex skill, like playing the guitar or speaking a new language, in a fraction of the time? |

References

- Lund, B.D.; Agbaji, D.; Mannuru, N.R. Perceptions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and AI’s Impact on Society. https://ci.unt.edu/computational-humanities-information-literacy-lab/4irlund.pdf, 2025. Accessed: 2025-08-31.

- Philbeck, T.; Davis, N. THE FOURTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: SHAPING A NEW ERA. Journal of International Affairs 2018, 72, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, S.Y. THE FOURTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: DIGITAL FUSION WITH INTERNET OF THINGS. Journal of International Affairs 2018, 72, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, C. Is this time different? Impact of AI in output, employment and inequality across low, middle and high-income countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2025, 73, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, J.; Clifton, L.; Dung, N.T.; et al. Mitigating Machine Learning Bias between High Income and Low-Middle Income Countries for Enhanced Model Fairness and Generalizability. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Matthews, L.; Dagher, G.K. Need for achievement, business goals, and entrepreneurial persistence. Management Research News 2007, 30, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive Psychological Capital: Measurement and Relationship with Performance and Satisfaction. Personnel Psychology 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. Bridging the intention–behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychology & Health 2005, 20, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, G.Y.; Chang, C.Y.; Lin, C.F.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, L.W.; Yeh, T.K. Perceived Behavioral Control as a Mediator between Attitudes and Intentions toward Marine Responsible Environmental Behavior. Water 2021, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Ajzen, I.; Hamilton, K. Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology 2022, 41, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D.D.; Mazanov, J.; Meacheam, D.; Heaslip, G.; Hanson, J. Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: Flow-on effects for online learning behavior. The Internet and Higher Education 2016, 29, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getenet, S.; Cantle, R.; Redmond, P.; et al. Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Prida, V.; Chuquin-Berrios, J.G.; Moreno-Menéndez, F.M.; Sandoval-Trigos, J.C.; Pariona-Amaya, D.; Gómez-Bernada, K.O. Digital Competencies as Predictors of Academic Self-Efficacy: Correlations and Implications for Educational Development. Societies 2024, 14, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brändle, L.; Kuckertz, A. Inequality and Entrepreneurial Agency: How Social Class Origins Affect Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Business & Society 2023, 62, 1203–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.A.; Howard, J.A. Social Psychological Theories on Social Inequalities. Social Psychology Quarterly 2000, 63, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, M.B.; MacMillan, I.C. Entrepreneurship: Past research and future challenges. Journal of Management 1988, 14, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-31.

- House of Commons International Development Committee. DFID’s work on education: Leaving no one behind? https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmintdev/99/9904.htm, 2017. Accessed: 2025-08-31.

- UNICEF. Youth at the Forefront of Change in the Democratic Republic of Congo. https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/stories/youth-forefront-change, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-31.

- Abramson, L.Y.; Seligman, M.E.; Teasdale, J.D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1978, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Digital Transformation Drives Development in Africa. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/01/18/digital-transformation-drives-development-in-afe-afw-africa, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- Lake, M. Building the Rule of War: Postconflict Institutions and the Micro-Dynamics of Conflict in Eastern DR Congo. International Organization 2017, 71, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, S.S.; George, N.S.; Iseghehi, L. Protecting the health of the most vulnerable in the overlooked Democratic Republic of Congo crisis. Health Science Reports 2024, 7, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titeca, K.; Edmond, P. The political economy of oil in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): Corruption and regime control. The Extractive Industries and Society 2019, 6, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, A.S.; Green, D.P. Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, D.J.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Gonzalez, R. Are manipulation checks necessary? Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://africa.unwomen.org/en/where-we-are/west-and-central-africa/democratic-republic-of-congo, 2024. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- Pugliese, F. Mining companies and gender(ed) policies: The women of the Congolese Copperbelt, past and present. The Extractive Industries and Society 2021, 8, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Changing social norms and values to end widespread violence against women and girls in DRC. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/changing-social-norms-and-values-end-widespread-violence-against-women-and-girls-drc, 2022. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- World Bank. Obstacles and Opportunities for Women’s Economic Empowerment in DRC. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/obstacles-and-opportunities-womens-economic-empowerment-drc, 2023. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- UN Women. Gender Country Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. https://www.lauradavis.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Gender-Country-Profile-DRC-2014.pdf, 2014. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- PeaceWomen. Gender Inequality in the DRC. https://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/hrinst_genderinequalityinthedrc_wilpf_december2010english_0.pdf, 2010. Accessed: 2025-08-30.

- Filmer, D.; Pritchett, L.H. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001, 38, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. Places to play, places in play. In Tourism Mobilities: Places to Play, Places in Play; Sheller, M., Urry, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2004; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; McKenzie, D. In Pursuit of Balance: Randomization in Practice in Development Field Experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2009, 1, 200–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.W.; Piff, P.K.; Keltner, D. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of personality and social psychology 2009, 97, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.M.; Markus, H.R.; Phillips, L.T. Social class culture cycles: How three gateway contexts shape selves and fuel inequality. Annual Review of Psychology 2014, 65, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much; Times Books: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standing, G. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class; Bloomsbury Academic: London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donou-Adonsou, F. Technology, education, and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy 2019, 43, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 1999, 3, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. Moral disengagement. Current Opinion in Psychology 2015, 6, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalvi, S.; Dana, J.; Handgraaf, M.J.J.; De Dreu, C.K.W. Justified ethicality: Observing desired counterfactuals modifies ethical perceptions and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2011, 115, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment groups | p value for test of: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | AI | Space (placebo) | 1=2 | 1=3 | 1=(2 ∪ 3) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Age | 28.14 | 28.12 | 24.28 | 0.980 | 0.000 | 0.034 |

| (1.37) | (2.05) | (1.15) | ||||

| male | 0.460 | 0.470 | 0.481 | 0.867 | 0.752 | 0.791 |

| (0.49) | (0.43) | 0.47) | ||||

| Single | 0.452 | 0.456 | 0.638 | 0.948 | 0.007 | 0.20 |

| (0.52) | (0.40) | (0.44) | ||||

| Protestant | 0.430 | 0.396 | 0.457 | 0.554 | 0.696 | 0.814 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.46) | ||||

| Possess at least one car | 0.386 | 0.550 | 0.434 | 0.005 | 0.497 | 0.022 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Number of Kids | 2.08 | 1.99 | 1.14 | 0.719 | 0.0003 | 0.073 |

| (0.49) | (0.49) | (0.51) | ||||

| Originate from Goma | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| (0.49) | (0.51) | (0.50) | ||||

| FC barcelona Fan | 0.510 | 0.450 | 0.602 | 0.301 | 0.187 | 0.902 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Is the Eldest | 0.474 | 0.442 | 0.518 | 0.595 | 0.533 | 0.931 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Has a college Degree | 0.540 | 0.436 | 0.530 | 0.079 | 0.885 | 0.193 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Possess and Iphone | 0.576 | 0.510 | 0.554 | 0.26 | 0.747 | 0.344 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Has a sister | 0.584 | 0.644 | 0.590 | 0.297 | 0.925 | 0.439 |

| (0.51) | (0.50) | (0.49) | ||||

| Retained Items | Dimensions | Communalities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | Locus of control | |||

| Selfficacy1 | I am confident in my ability to start and run my own business even if it is difficult | 0.74 | 0.55 | |

| Selfficacy2 | For me, starting and running a business would be easy. | 0.73 | 0.53 | |

| Selfficacy3 | I am certain that I can successfully start and manage a business if I really want to. | 0.72 | 0.52 | |

| Selfficacy4 | I believe I have the skills necessary to start and run a business. | 0.80 | 0.64 | |

| Selfficacy5 | Even with limited resources, I am sure I could still manage to start a business. | 0.74 | 0.54 | |

| Locontrol1 | Whether or not I start and run a business is entirely up to me. | 0.83 | 0.69 | |

| Locontrol2 | External circumstances prevent me from starting and running a business. (reverse-coded) | 0.62 | 0.48 | |

| Locontrol3 | The decision to become an entrepreneur lies within my control. | 0.80 | 0.63 | |

| Locontrol4 | Other people often prevent me from starting and running a business. (reverse-coded) | 0.76 | 0.58 | |

| Locontrol5 | Successfully starting and managing a business depends mostly on me, not on factors outside my control. | 0.68 | 0.82 | |

| Variance explained | 0.28 | 0.27 | ||

| Eigenvalues | 3.3503523 | 3.0584156 | ||

| Indices | df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA [90% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFA Model | 1571.39 | 26 | 0.985 | 0.97 | 0.025 | 0.053 [0.032, 0.073] |

| Dependent variable: | |||||

| Selfficacy | Locontrol | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| AI | 0.017 | 0.057 | 0.045 | −0.273** | −0.176 |

| (0.065) | (0.090) | (0.069) | (0.106) | (0.119) | |

| Car | −0.061 | −0.067 | 0.060 | −0.106 | −0.024 |

| (0.061) | (0.088) | (0.054) | (0.078) | (0.079) | |

| Placebo | 0.023 | 0.022 | −0.048 | −0.041 | −0.041 |

| (0.087) | (0.088) | (0.059) | (0.058) | (0.058) | |

| male | −0.018 | 0.024 | 0.167*** | 0.003 | 0.075 |

| (0.056 | (0.0799) | (0.058) | (0.078) | (0.080) | |

| AI:Car | 0.017 | 0.343*** | 0.140 | ||

| (0.109) | (0.122) | (0.171) | |||

| male:Car | 0.054 | −0.122 | |||

| (0.122) | |||||

| AI:male | −0.104 | 0.327*** | 0.112 | ||

| (0.106) | (0.124) | (0.182) | |||

| AI:male:Car | 0.433* | ||||

| (0.245) | |||||

| Constant | 4.108*** | 4.095*** | 3.974*** | 4.079** | 4.055*** |

| (0.123) | (0.127) | (0.112) | (0.113) | (0.114) | |

| Observations | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 |

| R2 | 0.044 | 0.047 | 0.056 | 0.105 | 0.115 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.067 | 0.075 |

| F Statistic | 1.377 | 1.237 | 1.751* | 2.773*** | 2.856*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).