1. Introduction

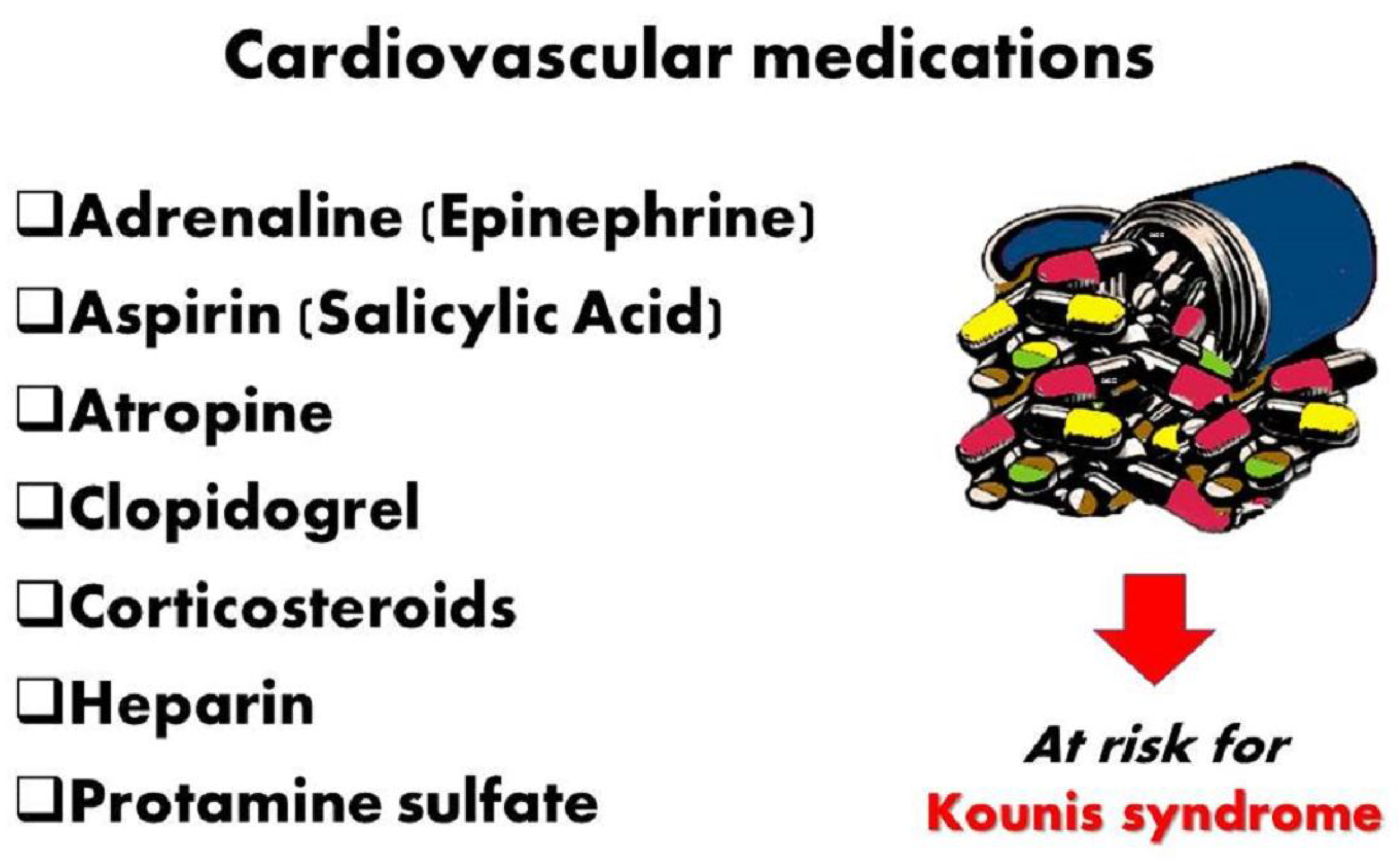

The primary causes of Kounis syndrome include the degranulation of mast cells and other interacting and associated cells, such as T-lymphocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and platelets, as well as a variety of inflammatory mediators generated during an anaphylactic or allergic reaction or attack. Histamine, tryptase, derivatives of arachidonic acid, and chymase can all contribute to acute ischemia events, coronary spasm, atheromatous plaque erosion/rupture, and platelet activation in the Kounis syndrome cascade. Kounis syndrome is now recognized as a unique kind of acute vascular syndrome that impacts the cerebral, mesenteric, peripheral, and venous systems in addition to the coronary arteries. Furthermore, Kounis syndrome is a multisystem and interdisciplinary illness rather than a single-organ vascular ailment. Drugs, hymenopteran stings, metals, foods, environmental exposures, diseases, and vaccinations are some of the things that might cause Kounis syndrome. Moreover, a number of peculiar, uncommon, fascinating, and important causes of Kounis syndrome have been identified in recent years. The kiss of death is one of them, in which kissing a person or pet kissing can cause deadly Kounis syndrome. In a paradoxical clinical scenario, Kounis syndrome may be brought on by important drugs and substances used to treat thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and Kounis syndrome. These include adrenaline (epinephrine), aspirin, atropine, clopidogrel, corticosteroids, heparins, protamine sulfate and hirudotherapy.

2. Current Perspectives on Kounis Syndrome

The first classification of cardiovascular symptoms linked to anaphylactic, anaphylactoid, allergy, or hypersensitive responses as acute carditis, morphologic cardiac reactions, or rheumatic carditis of uncertain pathogenesis was based on blood pathology. In 1991, the allergic angina syndrome was first thoroughly characterized as a cardiac spasm [

1]. Later known as Kounis syndrome, this was a sign of endothelial dysfunction or microvascular angina that resulted in allergic acute myocardial infarction [

2,

3]. The primary causes of Kounis syndrome include a variety of inflammatory mediators generated after an anaphylactic or allergic reaction or insult, from the degranulation of mast cells and other interacting and connected cells, such as T-lymphocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and platelets. Histamine, tryptase, and arachidonic acid derivatives, as well as chymase, which functions as a converting enzyme, can all contribute to acute ischemia event coronary spasm, atheromatous plaque erosion/rupture, and platelet activation in the Kounis syndrome cascade. Drugs, hymenoptera stings, metals, foods, environmental exposures, medical disorders, and vaccinations are all possible triggers for Kounis syndrome. According to recent studies, the incidence of this condition varies from 1.1% to 3.4% in individuals who have an allergic, hypersensitive, anaphylactic, or anaphylactoid insult [

4]. It can impact not only the coronary arteries but also the mesenteric, cerebral, and peripheral arteries. Despite this, Kounis syndrome seems to be underdiagnosed. Initially, it was believed to be an uncommon ailment. The best way to diagnose it and administer the appropriate therapy is to employ a high rate of suspicion [

3].

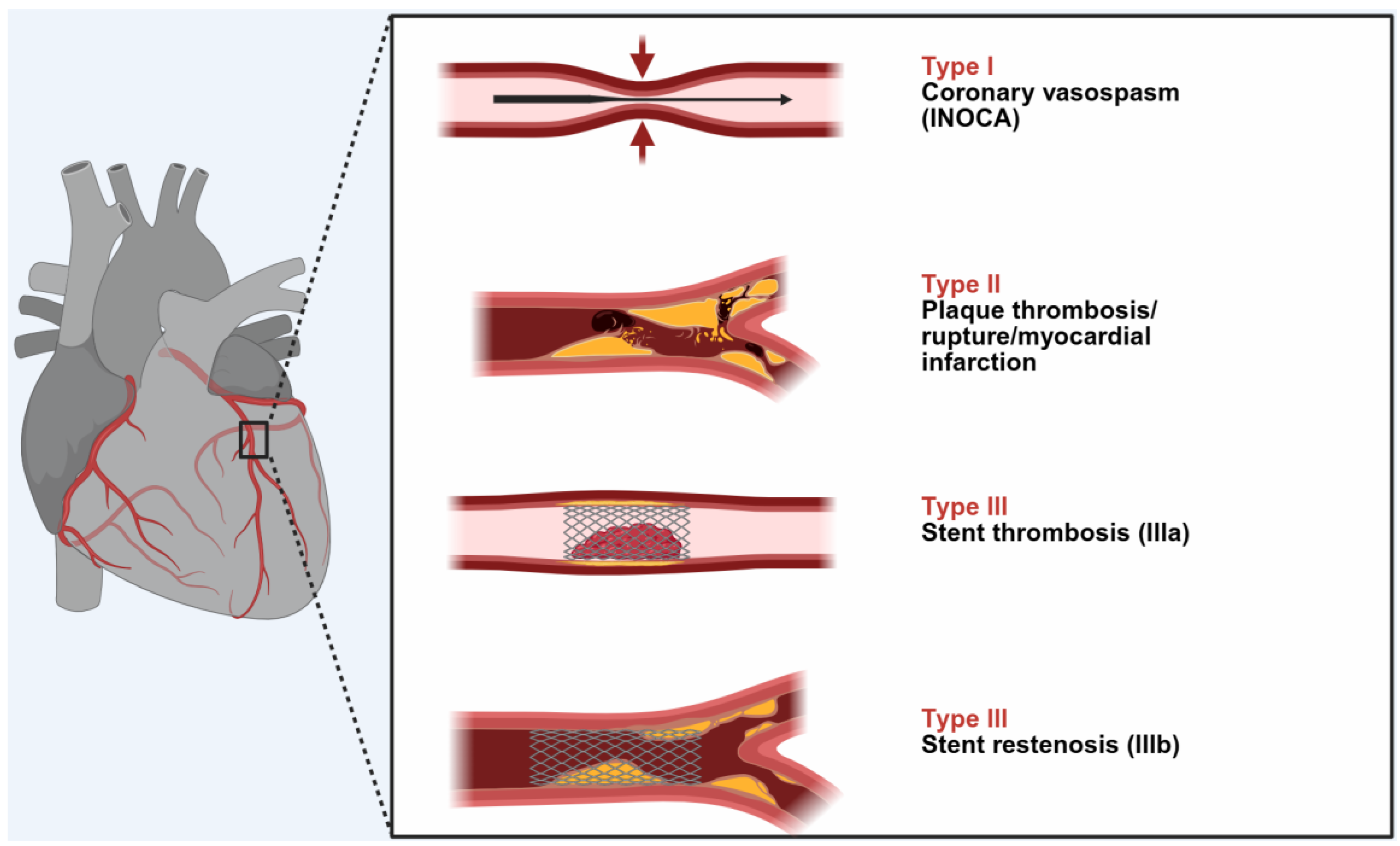

Three types of this condition have been identified thus far

Figure 1:

A myocardial infarction of type I or INOCA (Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries) affects 76.6% of patients with normal or nearly normal coronary arteries and is brought on by histamine, chymase, or arachidonic acid products (leukotrienes, platelet-activating factor). Acute myocardial infarction with platelet activation and the same conditions that produce type I also induce type II, which affects 22.3% of patients with quiescent prior coronary disease. 5.1% of patients had type III stent thrombosis (subtype IIIa) or stent restenosis (subtype IIIb), which is caused by stent polymers, stent metals, eluted drugs, dual antiplatelets, and environmental exposures [

5].

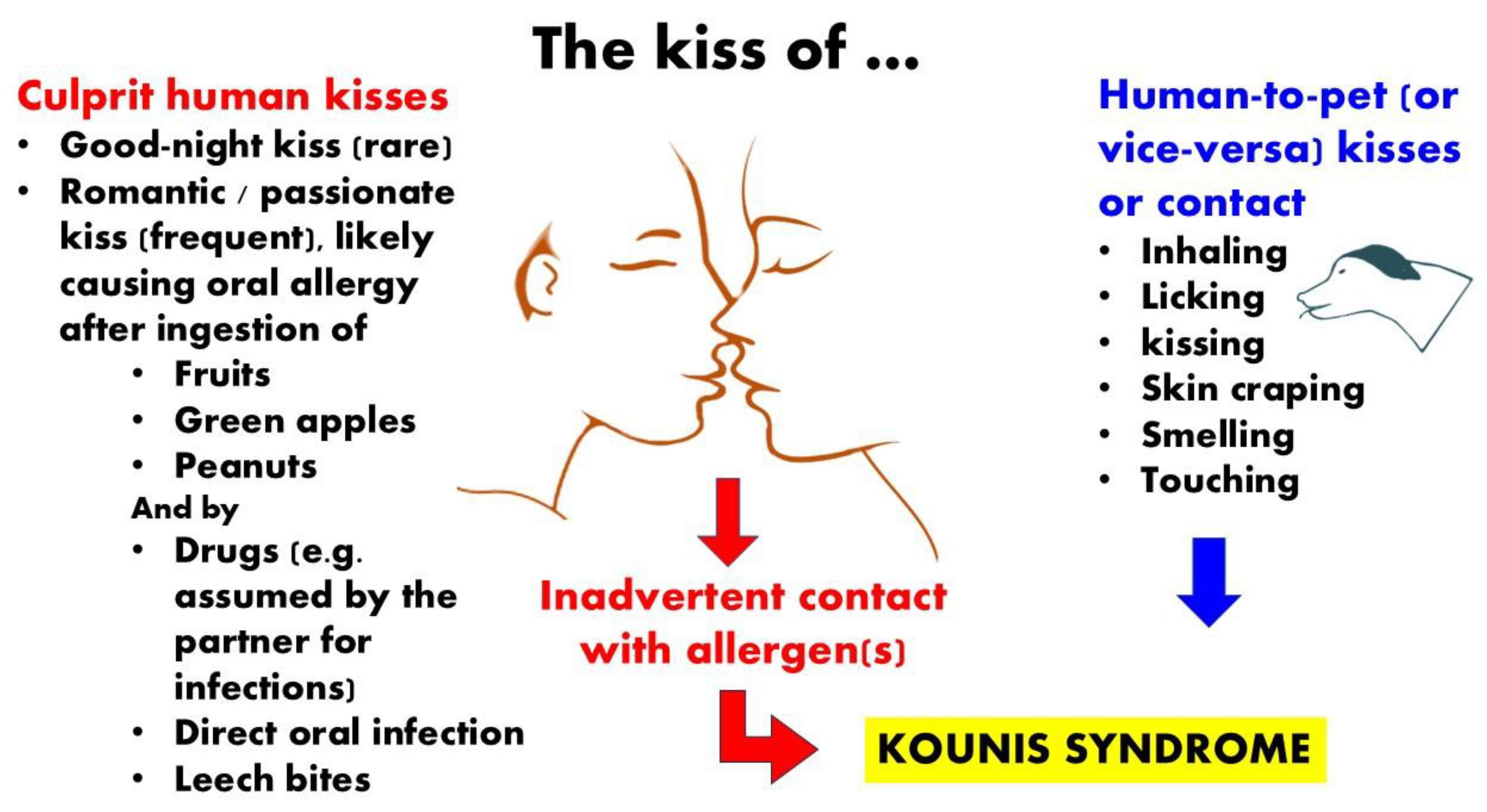

3. The Kiss of Death

3.1. Gereral Considerations

Kissing is an age-old method of expressing affection or simple erotic desire. "Kiss of death" is a phrase used to describe a behavior or relationship that has lethal or catastrophic outcomes. While the most well-known example is Judas' "kiss," which betrayed Jesus Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane and identified him to his executioners, "kiss" also serves as a mafia signal that someone has been marked for execution. In a variety of social contexts, including movies, sports, literature, music, technology, and even medicine, this type of expression is common. In the context of loving pets, "kissing" by insects and bugs refers to an offensive, defensive, feeding biting that has all negative effects. Licking and kissing are displays of love and submission to their owners that can spread allergens and bacteria to people. Utilizing super-resolution microscopy to demonstrate how gold nanoparticles can effectively kill cancer cells by inducing a crucial "golden" kiss of death on the nuclei and mitochondria is a metaphorical medical example of kissing [

6]. In the real world, passionate kisses can sometimes have disastrous or even fatal outcomes. Unexpectedly deadly outcomes can arise from a friend's passionate kiss, a pet's tender kiss or licking, and a flying kisser bug's hostile kiss. Kissing involves touching the saliva, skin, and oral mucosa as well as inhaling substances. Consequently, it is anticipated that disease transmission may become feasible. Because of its flushing action, human saliva has a natural cleansing function. Nevertheless, human saliva can act as a vector for bacteria, viruses, and allergens even though it contains antimicrobial defenses like antibodies and other antimicrobial proteins like lysozyme [

7]

3.2. Human Kissing Inducing Allergy and Kounis Syndrome

There are reports of food allergens that can cause an allergic reaction when they are transferred from one person to another through physical contact, such as kissing. If one lover is sensitized to the food that the other just consumed, the close contact of two oral mucosae during kissing may result in an oral allergy syndrome. Some examples include: severe allergic reaction to a shellfish brought on by a good-night kiss [

8], kiss-induced allergy to peanuts [

9], and oral allergy syndrome to green apples following a lover's kiss [

10]. Kiwi fruit-induced oral allergy syndrome following a romantic kiss [

11]. Kounis syndrome is an acute coronary syndrome linked to allergies FIGURE 2 that is brought on by eating actinidia chinensis [

12]. After eating a piece of kiwifruit, a young man, age 23, who had previously experienced oral allergy syndrome to kiwifruit, suffered an acute myocardial infarction [

13]. A second case of kiwifruit-induced Kounis syndrome has been documented in the literature since the first one [

14]. When her grandfather kissed her on the cheek after eating fish two hours prior, a 2-year-old girl with a fish allergy developed facial urticaria and angioedema [

15]. On multiple occasions, a 45-year-old woman who became sensitized to bacampicillin after her husband kissed her while he was taking the medication for gingivitis has also been reported to have contracted a drug allergy spread by passionate kissing [

16]. The skin, oral mucosa, and saliva can spread bacteria and viruses in addition to allergens. One remarkable instance is the "kiss of death" of a 23-year-old South African man who, after oral contact with a woman who was found to have evidence of an active herpes simplex virus infection, developed fulminant hepatic failure and passed away from multiorgan failure as a result of overwhelming sepsis [

17].

Figure 2.

Green apples, shrimp, peanuts, and kiwi fruits can cause allergies after a passionate kiss. Adorable dogs can act as "indirect hosts" that contaminate humans by licking, kissing, caressing, dandering, inhaling, or smelling.

Figure 2.

Green apples, shrimp, peanuts, and kiwi fruits can cause allergies after a passionate kiss. Adorable dogs can act as "indirect hosts" that contaminate humans by licking, kissing, caressing, dandering, inhaling, or smelling.

3.3. Pet Kissing Inducing Allergy and Kounis Syndrome

Humans may be impacted by the transmission of allergens and microbes through pet kissing, licking, and dander. According to data from skin-prick tests, pet allergies may be the most prevalent perennial allergen in the Unted States, while small, suspended, particulate animal allergens may be present in 90% of all homes and the majority of public indoor spaces [

15]. There are five other well-described allergens for both cats and dogs, even though Fel d 1 and Can f 1 are the most significant allergens for both. Car seats contain levels of dog and cat allergen that are significantly higher than the threshold levels for human sensitization and symptoms, and homes with pets have significantly higher levels of Fel d 1 or Can f 1 allergen than homes without pets [

19]. Antibiotics are the primary treatment agents for microbial pet infections. In a report, 17 patients developed Kounis syndrome, which was confirmed by cardiac catheterization, positive skin tests for antibiotics, elevated IgEs, histamine, tryptase, and a positive leukocyte transformation test [

20]. Beta-lactams were among the common causes of Kounis syndrome. The beta-lactam antibiotics were given intramuscularly, intravenously, and orally. All patients survived cardiac catheterization, even though type I and type II variants of this syndrome were found. Men accounted for 76% of the patients. In a somewhat intriguing study [

21], an atopic patient who was sensitive to beta-lactams and had experienced two myocardial infarctions after ingesting amoxicillin orally experienced a third episode of Kounis syndrome-like acute myocardial infarction after being licked on the face by his devoted dog. Amoxicillin had been used to treat the dog. It has been discovered that when amoxicillin-containing saliva comes into contact with an atopic patient's skin, it can cause an allergic reaction and Kounis syndrome. Additionally, it has been discovered that following oral administration of 750 mg of amoxicillin, sputum concentrations of the antibiotic are between 0.4 and 0.5 mg/l [

22]. According to this report, sensitized people can develop Kounis syndrome without necessarily coming into contact with, breathing in, or consuming the responsible allergen [

23]. By licking, kissing, touching, dandering, inhaling, or smelling, affectionate pets can serve as "indirect hosts" that can spread illness to people

4. A Clinical Paradox: Key Medications and Substances Used to Treat Myocardial Infarction and Kounis Syndrome Can Cause Kounis Syndrome

4.1. Adrenaline (Epinephrine)

Ironically, the medication that can save lives in cases of anaphylaxis, adrenaline, can also cause anaphylaxis on its own [

24]. According to Drug Facts and Comparisons, a standard pharmacy reference published by Wolters Kluwer and updated monthly, sodium metabisulfite is a preservative found in all commercially available preparations of adrenaline [

25]. A common antioxidant in the food and pharmaceutical industries is sodium metabisulfite. Metabisulfite, an additive agent of local anesthetics containing adrenaline, has been implicated in cases of anaphylactic shock that occurred during the administration of epidural anesthesia for caesarian sections. When sulfite-sensitive patients experience anaphylactic shock, this presents a therapeutic conundrum. This association should be known by medical professionals who treat anaphylactic shock. Thankfully, sulfite-sensitive patients can now receive free sulfite adrenaline from a commercial source (American Regent Inc., USA) [

26]. Glucagon, which has been effectively used to treat anaphylaxis in patients on β-blockers, is a potential substitute in this case. Specifically, International guidelines recommend injecting exogenous adrenaline intramuscularly at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg of a 1:1000 (1 mg/mL) solution11, up to a maximum dose of 0.5 mg in adults. This procedure can save lives. Twelve Properly diluted solutions (1:10 000 [0.1 mg/mL] or 1:100 000 [0.01 mg/mL]) for intravenous administration may exacerbate coronary spasm. A challenging contemporary clinicopharmacological combination is the Adrenaline, Takotsubo, Anaphylaxis, and Kounis (ATAK) complex [

27]. "Attacking" is required to clarify its pathophysiology and etiology and to put preventative and therapeutic measures into action. Although adrenaline is the preferred medication for treating anaphylactic shock, administering it may cause coronary spasm

Figure 3. Furthermore, Takotsubo syndrome can result from direct myocardial stunning that causes coronary spasms [

28]. The mediators released during anaphylaxis can also cause Τakotsubo and coronary spasms [

29]. In addition to providing hemodynamic support during anaphylactic shock, administering adrenaline may raise plasma catecholamine levels, which would further feed this vicious cycle has also been linked to Kounis syndrome [

30].

4.2. Aspirin

Over the past 30 years, basic and clinical research has shed a great deal of light on the role that thromboxane A2 (TXA2)-dependent platelet activation plays in intestinal inflammation, atherothrombosis, primary hemostasis, tissue repair, and colorectal cancer. The cytochrome c oxidase complex's primary subunit, the cytochrome c oxidase I gene (COX-1 gene), is manipulated to produce these effects. Low-dose aspirin is also used, and TXA2 biosynthesis is measured in both human and mouse models [

31]. Despite that, the field of antiplatelets has advanced over these years, the use of aspirin plays a key role in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The focus has shifted from efficacy to safety, supporting aspirin-free antiplatelet regimens following percutaneous coronary intervention, and there have been multiple attempts to create antiplatelet medications that are safer and more effective than aspirin. There is now more proof that low-dose aspirin can prevent not only atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease but also can prevents colorectal (and other digestive tract) cancer by acting as a chemopreventive agent [

32]. Aspirin can cause Kounis syndrome, despite its positive effects on cardiovascular conditions. Kounis syndrome, also referred to as the Samter-Beer triad, is a combination of nasal polyps, asthma, and aspirin allergy that causes vasospasm and myocardial infarction. In order to identify the Kounis syndrome quickly and focus treatment on reducing the allergic reaction, all doctors should be aware of this special clinical entity [

33]. Another report describes a case of Kounis syndrome secondary to asthma brought on by taking aspirin, which was meant to treat angina pectoris [

34]. Furthermore, a case study of a patient with a history of aspirin allergy who developed coronary vasospasm after taking an aspirin dosage is presented in another paper [

35].

4.3. Atropine

Atropine can be used to treat a number of conditions, such as anticholinergic poisoning, pupil dilatation, and symptomatic bradycardia without reversible causes. The alkaloid atropine was first produced by synthesizing it from Atropa belladonna. Just l-hyoscyamine is pharmacologically active out of the racemic mixture of d- and l-hyoscyamine. There are only combination products that contain oral atropine. Atropine inhibits the effects of acetylcholine and other choline esters by acting as a competitive, reversible antagonist of muscarinic receptors. Usually found as a sulfate salt, atropine can be given intravenously, subcutaneously, intramuscularly, intraosseously, endotracheally, or ophthalmically. Even though severe allergic reactions to atropine are extremely uncommon, patients who have experienced an allergic reaction in the past are more likely to experience a severe reaction in the future. We believe that the sulfate salt for intravenous use may be the cause of the allergic reaction leading to Kounis syndrome. Free sulfate salt preparations of atropine might need to be developed. The following two reports of atropine-induced Kounis syndrome have been already published 1. The authors of this first report [

36] express the opinion that this is the first pediatric instance of Kounis syndrome caused by intravenous atropine that they are aware of. Silent myocardial ischemia can cause coronary vasospasm, which can lead to sudden death. A variety of pharmacological agents are among the numerous precipitant factors. They came to the conclusion that acute coronary syndromes linked to anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions are what characterize Kounis syndrome. 2. In a different study [

37] the authors stated that atropine is rarely associated with allergic reactions. However, they detailed a case of a male patient, age 25, who had a history of persistent bradycardia, psychotic disorder, and cannabis dependent syndrome. When given atropine, he experienced urticarial rash, dyspnea, and chest pain. The electrocardiogram displayed ST segment alterations that subsided following symptom relief. Coronary arteries were found to be normal by coronary angiography. Despite being rarely reported, it is one of the serious conditions that treating physicians find difficult to diagnose and underdiagnose, even though it may mimic ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

4.4. Clopidogrel

Aspirin and more modern antiplatelet drugs, are employed in antiplatelet therapy because platelet aggregation is a biological target for the treatment of thromboembolisms and other clotting disorders. These agents include: clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelol. Clinical professionals treating patients need to be well-versed on the pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical effectiveness, and safety of routinely used antiplatelet treatment [

38]. The most typical symptom of a clopidogrel allergy is a rash. It's critical to differentiate this from other reasons why patients who recently received a coronary stent develop rash. The majority of clopidogrel hypersensitivity reactions can be effectively treated with antihistamines and short-term oral corticosteroids, but some persistent reactions may necessitate stopping clopidogrel. It has long been practiced to substitute an alternative thienopyridine, such as ticlopidine, when stopping clopidogrel is necessary. However, according to a recent study, there may be a 27% chance that non-life-threatening allergic reactions, which are typically comparable to those that happened with clopidogrel, will recur in these patients [

39]. Three reports of clopidrogrel-induced Kounis syndrome have been reported so far. In the first report [

40], a 61-year-old man was hospitalized due to increasing chest pain. For ten years, he experienced frequent episodes of excruciating chest pain during normal activities and at rest. He had smoked 20 cigarettes a day for almost 30 years, making him a heavy smoker. In addition, he had previously experienced allergic reactions, atopic eczema, and hypertension.

The final diagnosis was Type I Kounis syndrome secondary to an allergic reaction to clopidogrel. Another report described a 56-year-old male patient with Kounis Syndrome who experienced angioedema, respiratory distress, and vasospasm in the right coronary artery following a loading dose of clopidogrel [

41]

. Moreover, recurrent acute stent thrombosis associated with clopidogrel-induced allergic reaction leading to Kounis syndrome was in a 44-year-old male patient [

42]. Desensitization to clopidogrel has become necessary as a result of all these incidents. For clopidogrel-sensitive individuals who need long-term dual antiplatelet medication desensitization is safe and very successful [

43].

4.5. Corticosteroids

Although corticosteroids are frequently used to treat allergic responses, they can also cause anaphylaxis with Kounis syndrome and acute, delayed, local, or systemic allergic reactions [

44]. By inhibiting phospholipase A2 and eicosanoid production, they can prevent the release of arachidonic acid from mast cell membranes. In addition to mediating the manufacture of annexin or lipocortin, which are chemicals that regulate inflammatory cell activation, adhesion molecule expression, transmigratory, and phagocytic processes, corticosteroids can also induce cell death. Among the implicated reasons are hapten production, antigen-antibody interaction, and drug pollutants. The following pathways allow systemic corticosteroids to cause allergic reactions [

45]: 1. There have been reports of anaphylactic reactions to methylprednisolone involving IgE antibodies. 2. The medications that most commonly cause type 1 (immediate) adverse responses are succinate esters of hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone. 3. The hapten synthesis is aided and functions as a full antigen because succinate esters have a stronger affinity for serum proteins and a greater solubility in water. 4. The medications that most commonly cause type 1 (immediate) adverse responses include methylprednisolone and hydrocortisone succinate esters.

A patient with polymalformative syndrome who had previously undergone a gastrostomy for necrotizing enterocolits and experienced anaphylaxis to cow's milk proteins experienced multiple episodes of anaphylaxis, including urticaria, eyelid edema, laryngospasm, and severe dyspnea, just a few minutes after receiving 10 mg of methylprednisolone sodium succinate intravenously [

45]. Moreover, after receiving methylprednisolone succinate pulse treatment for neuromyelitis optica and systemic lupus erythematosus, two patients had anaphylactic shock with cutaneous and systemic symptoms [

46]. Another 52-year-old lady who had previously had an allergy to anti-haemorrhoid lotions and ointments experienced a widespread symmetrical pruritic eruption after receiving 1 milliliter of triamcinolone acetonide intra-articularly [

47]. Atopic diathesis patients are especially at risk. Before administering any specific medicine, including corticosteroids, a full and comprehensive history of drug reactions or allergies is required.

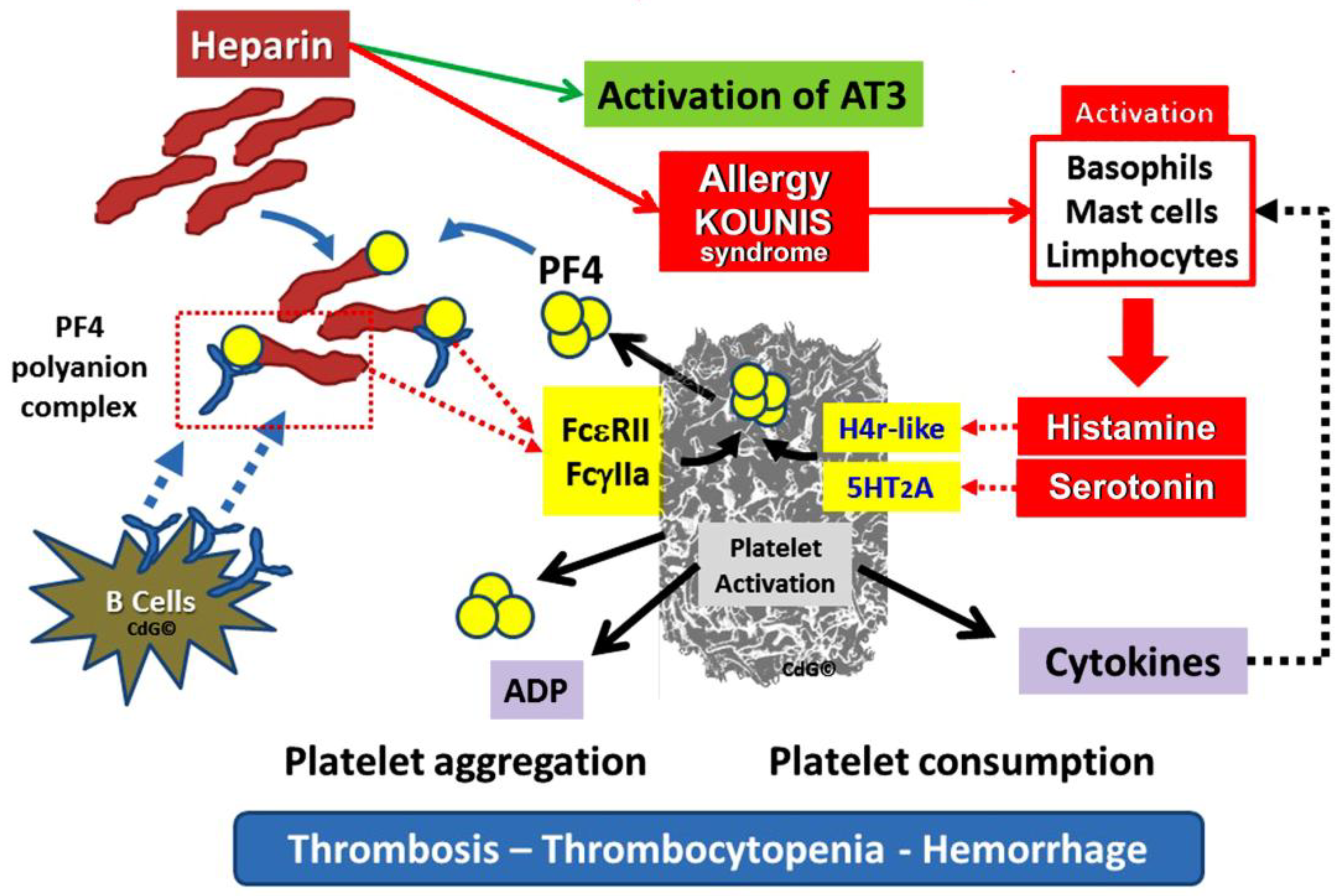

4.6. Heparines

Heparin, is a blood anticoagulant, that makes antithrombin more active. Antithrombin inactivates its physiological target enzymes, Thrombin, Factor Xa and Factor. The clinical paradox is that physicians are cautious of the potential for bleeding side effects when they prescribe heparins since they might cause, occasionally, thrombocytopenia, which can worsen bleeding. However, thrombocytopenia may result in unanticipated severe thrombosis. Indeed, the primary antigen that activates platelets via the Fc gamma receptor II (FcγRII) and causes thrombosis is the three-component immunological complex, which is made up of heparin, platelet factor 4 (PF4), and Immunoglobulin G (IgG). The ensuing extensive thrombosis increases platelet consumption and worsens thrombocytopenia.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is characterized by a decrease in platelet counts and a hypercoagulable condition [

48]. Significant morbidity and death are linked to thromboembolic problems that patients who undergo HIT may also endure

Figure 4. Given the widespread use of heparin for line flushes, heparin-coated catheters, and the prevention and treatment of thromboembolism, this represents a substantial burden [

49].

Heparin, rarely, can cause Kounis syndrome as in the following 5 days of age, patient: Kounis Syndrome was suspected in a full-term newborn who had a Rashkind-atrioseptostomy and stenting and had intermittent episodes of acute coronary syndrome. Tests on the skin of nickel and titanium yielded no results. The suspected medications were tested using basophil activation test and lymphocyte transformation (LTT). A heparin-positive LTT and non-respond to basophils were found in the BAT (Basophil Activation Test). After a fresh heparin dose was inadvertently administered, a new acute coronary syndrome was developed. According to the authors, this was the first case of Kounis syndrome in an infant brought on by heparin therapy [

50]. Moreover, heparin treatment for a 67-year-old lady with deep vein thrombosis in her lower limbs resulted in an acute thrombus development and an ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Her heparin-PF4 IgG antibody and serotonin release assay were both positive, supporting the diagnosis of HIT [

51]. Therefore, the clinical conundrum is that heparin used to treat thrombotic events such as Kounis syndrome can also induce thrombosis and Kounis syndrome.

4.7. Protamine Sulfate

Protamine sulfate is a drug used to counteract heparin's effects. It is used primarily to counteract the effects of heparin after delivery and cardiac surgery, as well as to treat heparin overdose and low molecular weight heparin overdose. It is administered intravenously. Effects usually start to show up within five minutes. Hypersensitivity responses, vomiting, low blood pressure, and a sluggish heartbeat are typical adverse effects. Anaphylaxis is one of the severe allergic responses. For patients who have undergone a vasectomy, the risk is higher. The fifth Pregnancy-related use has not been thoroughly investigated, despite the fact that there is no proof of any negative effects. Protamine functions by binding itself to heparin. For many years, protamine has been utilized to speed up the removal of the sheath while still in the lab following catheter ablation and percutaneous coronary interventions. It has been demonstrated to speed up walking without raising the risk of thrombosis or problems with the access site. Hypersensitivity responses may result in pulmonary edema, dermatitis, hypotension, and, in rare cases, Kounis syndrome. There have been several reports of Kounis syndrome linked to the use of protamine sulfate. Although protamine sulfate shock is prevalent, Kounis syndrome might be concealed within it [

52,

53,

54]. Therefore, such situations shouldn't be handled as a straightforward protamine shock. The mechanism of protamine shock and associated risk factors, as well as the pathophysiology and type of Kounis syndrome in patients who had protamine shock, should be highlighted in these publications [

55]. Furthermore, one should consider the Kounis syndrome while considering the importance of ST-elevation during anaphylactic shock [

56].

5. Leech Is Used to Remove Thrombosis but It Can Induce Kounis Syndrome and Thrombosis

Since bloodletting was a widespread custom in ancient Greece, leeches (βδελα-λες, vthela-les in Greek) have been used medicinally for thousands of years. At the time, medical professionals thought that drawing blood from a patient could both prevent and treat illness. Leeches were used more frequently for bloodletting than rudimentary tools. One must first comprehend the paradigm of disease from Hippocrates' (~460–370 BC) time 2300 years ago in order to understand the justification for bloodletting. According to Hippocrates, four fundamental elements of life—earth, air, fire, and water-were analogous to Hippocrates the four basic humors of humans: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Each humor was associated with a specific personality type (sanguine, phlegmatic, melancholic, and choleric) and was centered in a specific organ (brain, lung, spleen, and gall bladder) [

58]. Approximately 650 species of leeches have been described worldwide. There are over 45 species in Australia alone. Leech therapy was developed in the 20th century as a preventative measure against venous congestion and as a means of preserving the flaps and replanted digits in plastic surgery and microsurgery. Leeches are being used for cosmetic purposes in a lot of plastic surgery clinics around the world. The significance of leeches as a supplemental medical therapy source for a wide range of conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, cancer and its metastases, plastic surgery, diabetes mellitus, and its complications is impotant. Although leech therapy has proven effective, there is ongoing debate regarding its safety and potential side effects [

59]. Hirudotherapy (leech therapy) made a comeback in the 1970s, the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, became the most widely used leech species for a variety of medical purposes, especially in complementary medicine for ailments like osteoarthritis and microsurgery for post-operative venous congestion. Hirudotherapy can be a useful adjunctive treatment; however, in order to get the greatest outcomes, careful consideration of both positive and negative factors must be made. Leech saliva contains physiologically active compounds including hirudin, which have anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilating effects. Recently, a hirudin-based fusion protein prodrug combined with microneedles for long-term antithrombotic treatment has been successful in achieving continuous protection, on-demand antithrombotic bioactivity recovery, and a streamlined dosage schedule [

60]. However, despide the anticoaculant action, six cases were found in a review of the published literature on leech allergies, five of which included mild allergic reactions like pruritus [

60]. Moreover, despite having no previous history of allergies, a 58-year-old man had anaphylaxis after being bitten by a leech, which resulted in myocardial infarction [

61]. Two cases documented the onset of Kounis syndrome [

62].

6. Perspectives

Allergy responses can result from a variety of drugs, situations, exposures, and chemical compounds. However, there are several unusual, uncommon, fascinating, and important causes of Kounis syndrome. Several drugs and substances that are used to treat thrombosis and Kounis syndrome have the potential to cause both the condition and anaphylactic responses. Atropine is often administered intravenously as a sulfate salt. Metabisulfite is a substance that is added to local anesthetics that include adrenaline. Protamine sulfate is used to reverse the effects of heparin. Sulfate is among the most often used drugs in clinical practice. On rare occasions, it might result in Kounis syndrome and anaphylactic reactions. Therefore, it is advisable to consider this response before to giving the drug. Moreover, those who are susceptible to allergic myocardial infarction and allergic angina can be protected by reducing their immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels. This can explain the reason why not every patient who has an allergic reaction also does not have Kounis syndrome seems to be addressed by the following: because their blood's IgE levels are lower. There may be hope for reducing allergy associated Kounis syndrome by focusing on the IgE route and the inflammatory processes linked to it [

63].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G.K., S.N.K., M.A.M., N.P. and U.O.; methodology, N.G.K., M.-Y.H. and A.C.; validation, N.G.K., C.d.G., I.K. and A.C.; investigation, A.C., A.S., M.B, I.K. and U.O.; original draft preparation, N.G.K., A.S., P.D. and S.N.K.; review and editing of the manuscript draft, S.N.K., A.C., V.M. and N.G.K.; project administration, I.K., N.G.K., S.P., K.-M.N.: and C.d.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kounis NG, Zavras GM. Histamine-induced coronary artery spasm: the concept of allergic angina. Br J Clin Pract 1991; 45: 121-8. [CrossRef]

- Zavras GM, Papadaki PJ, Kokkinis CE, Kalokairinov K, Kouni SN, Batsolaki M, Gouvelou-Deligianni GV, Koutsojannis C. Kounis syndrome secondary to allergic reaction following shellfish ingestion. Int J Clin Pract 2003; 57: 622-4. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Mplani V, de Gregorio C, Koniari I. Attack the ATAK; A Challenging Contemporary Complex: Pathophysiologic, Therapeutic, and Preventive Considerations. Balkan Med J 2023; 40: 308-311.

- Nanyoshi M, Hayashi T, Sugimoto R, Nishisaki H, Kenzaka T. Type I Kounis syndrome in a young woman without chest pain: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2024; 24: 467. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Mplani V, Koniari I. Kounis syndrome: A natural paradigm for preventing mast cell activation-degranulation. Int J Cardiol. 2025; 419: 132704. [CrossRef]

- Zou W, Yang L, Lu H, Li M, Ji D, Slone J, Huang T. Application of super-resolution microscopy in mitochondria-dynamic diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023; 200: 115043. [CrossRef]

- Vila T, Rizk AM, Sultan AS, Jabra-Rizk MA. The power of saliva: Antimicrobial and beyond. PLoS Pathog 2019; 15: e1008058. [CrossRef]

- Steensma DP. The kiss of death: a severe allergic reaction to a shellfish induced by a good-night kiss. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78: 221-2. [CrossRef]

- Wuthrich B, Dascher M, Borelli S. Kiss-induced allergy to peanut. Allergy 2001; 56: 913.

- Wuthrich B. Oral allergy syndrome to apple after a lover’s kiss. Allergy 1997; 52: 235-236. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Oral allergy syndrome from kiwi fruit after a lover’s kiss. Contact Dermatitis 2001; 45: 41. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Koniari I, Velissaris D, Tzanis G, Hahalis G. Kounis Syndrome—not a Single-organ Arterial Disorder but a Multisystem and Multidisciplinary Disease. Balkan Med J. 2019; 36: 212-221. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Giannopoulos S, Soufras GD, Kounis GN, Goudevenos J. Foods, Drugs and Environmental Factors: Novel Kounis Syndrome Offenders. Intern Med 2015;v54:1 577-82. [CrossRef]

- Gazquez V, Dalmau G, Gaig P, Gomez C, Navarro S, Mercι J. Kounis syndrome: report of 5 cases. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2010; 20: 162-165.

- Monti G, Bonfante G, Muratore MC, Peltran A, Oggero R, Silvestro L, Mussa GC. Kiss-induced facial urticaria and angioedema in a child allergic to fish. Allergy 2003; 58: 684-5. [CrossRef]

- Liccardi G, Gilder J, D'Amato M, D'Amato G. Drug allergy transmitted by passionate kissing. Lancet 2002; 359(9318): 1700. [CrossRef]

- Graham BB, Kaul DR, Saint S, Janssen WJ. Clinical problem-solving. Kiss of death. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 2564-8.

- Wallace DV. Pet dander and perennial allergic rhinitis: therapeutic options. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2009; 30: 573-83. [CrossRef]

- Neal JS, Arlian LG, Morgan MS. Relationship among house-dust mites, Der 1, Fel d 1, and Can f 1 on clothing and automobile seats with respect to densities in houses. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002; 88: 410-5. [CrossRef]

- Ridella M, Bagdure S, Nugent K, Cevik C. Kounis syndrome following beta-lactam antibiotic use: review of literature. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2009; 8:11-6. [CrossRef]

- Tosoni C, Cinquini M, Gretter V, Minetti S, Rizzini FL. Beware of the dog: a case report on cardiac involvement in drug allergy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2010; 12: 686-8.

- Davies B, Maesen F. Serum and sputum antibiotic levels after ampicillin, amoxycillin and bacampicillin chronic bronchitis patients. Infection 1979; 7 (Suppl 5): S465–S468. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Giannopoulos S, Goudevenos J. Beware of, not only the dogs, but the passionate kissing and the Kounis syndrome. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2011; 12: 149-50. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Koniari I, Tsigkas G, Soufras GD, Plotas P, Davlouros P, Hahalis G. Angina following anaphylaxis: Kounis syndrome or adrenaline effect? Malays Fam Physician. 2020; 15 :97-98.

- Roth JV, Shields A. A dilemma: How does one treat anaphylaxis in the sulfite allergic patient since epinephrine contains sodium metabisulfite? Anesth Analg. 2004; 98: 1499; author reply 1500. [CrossRef]

- Ameratunga R, Webster M, Patel H. Unstable angina following anaphylaxis. Postgrad Med J. 2008; 84: 659–61. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Mplani V, de Gregorio C, Koniari I. Attack the ATAK; A Challenging Contemporary Complex: Pathophysiologic, Therapeutic, and Preventive Considerations. Balkan Med J 2023; 40: 308-311.

- Yalta K, Madias JE, Kounis NG, Y-Hassan S, Polovina M, Altay S, Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Lopatin Y, Mamas MA,et al. Takotsubo Syndrome: An International Expert Consensus Report on Practical Challenges and Specific Conditions (Part-1: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges). Balkan Med J. 2024; 41: 421-441.

- Yalta K, Madias JE, Kounis NG, Y-Hassan S, Polovina M, Altay S, Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Lopatin Y, Mamas MA, et al Takotsubo Syndrome: An International Expert Consensus Report on Practical Challenges and Specific Conditions (Part-2: Specific Entities, Risk Stratification and Challenges After Recovery). Balkan Med J 2024; 41: 442-457.

- Di Filippo C, Giovannini M, Gentile S, Mori F, Porcedda G, Manfredi M, Calabri GB, De Simone L, Favilli S, Kounis NG. Kounis Syndrome Associated With Takotsubo Syndrome in an Adolescent With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. JACC Case Rep. 2021; 3 :1602–1606. [CrossRef]

- Patrono C. Low-dose aspirin for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2024; 45: 2362-2376. [CrossRef]

- Pulumati A, Algarin YA, Jaalouk D, Kim S, Latta S, Nouri K. Aspirin as a chemopreventive agent for cutaneous melanoma: a literature review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024; 316: 367. [CrossRef]

- Doghmi N, Zarzur J, Cherti M. Kounis syndrome induced by oral intake of aspirin: case report and literature review. Pan Afr Med J. 2018; 30: 301. Erratum in: Pan Afr Med J. 2019; 33: 172. [CrossRef]

- Oshima T, Ikutomi M, Ishiwata J, Ouchi K, Kato M, Amaki T, Nakamura F. Kounis syndrome caused by aspirin-induced asthma. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 175: e37-9. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Kouni SN, Koutsojannis CM. Myocardial infarction after aspirin treatment, and Kounis syndrome. J R Soc Med. 2005; 98: 296.

- Castellano-Martinez A, Rodriguez-Gonzalez M. Coronary artery spasm due to intravenous atropine infusion in a child: possible Kounis syndrome. Cardiol Young 2018; 28: 616-618. [CrossRef]

- Hussain A, Raj Regmi S, Mani Dhital B, Thapa S, Dhungana T, Khan A, Thapa S, Murarka R, Shrestha A, Chaudhary R, etc. Atropine and Kounis syndrome, a rare association mimicking ST segment elevation myocardial infarction in a young patient: A Case Report. Nepal Respir J 2023; 2: 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Dobesh PP, Varnado S, Doyle M. Antiplatelet Agents in Cardiology: A Report on Aspirin, Clopidogrel, Prasugrel, and Ticagrelor. Curr Pharm Des 2016; 22: 918-32. [CrossRef]

- Lokhandwala J, Best PJ, Henry Y, Berger PB. Allergic reactions to clopidogrel and cross-reactivity to other agents. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011; 11 :52-7. [CrossRef]

- Liping Z, Bin H, Qiming F. An Extraordinary Case Associated with an Allergic Reaction to Clopidogrel: Coronary Artery Spasm or Kounis Syndrome? Heart Lung Circ. 2015; 24: e180-3. [CrossRef]

- Ballı M, Tekin K, Taşolar H, Çağlayan E, Pekdemir H. Kounis Syndrome Due To Clopidogrel: A Rare Case Report [Turkish]. J Turgut Ozal Med Cent 2013; 20: 182-184.

- Karabay CY, Can MM, Tanboğa IH, Ahmet G, Bitigen A, Serebruany V. Recurrent acute stent thrombosis due to allergic reaction secondary to clopidogrel therapy. Am J Ther 2011; 18: e119-22. [CrossRef]

- von Tiehl KF, Price MJ, Valencia R, Ludington KJ, Teirstein PS, Simon RA. Clopidogrel desensitization after drug-eluting stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50: 2039-43. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG, Koniari I, Soufras GD, Chourdakis E. Anaphylactic shock with methylprednisolone, Kounis syndrome and hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: a clinical paradox. Ital J Pediatr. 2018; 44: 143. [CrossRef]

- Porcaro F, Paglietti MG, Diamanti A, Petreschi F, Schiavino A, Negro V, Pecora V, Fiocchi A, Cutrera R. Anaphylactic shock with methylprednisolone sodium succinate in a child with short bowel syndrome and cow's milk allergy. Ital J Pediatr. 2017; 43: 104. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi K, Asano T, Higashiyama Y, Koyano S, Doi H, Takeuchi H, Tanaka F. Two cases of anaphylactic shock by methylprednisolone in neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler. 2018; 24: 1514-1516. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Alarcón S, Benavente-Villegas FC, Farzanegan-Miñano R, Pérez-Francés C, Sánchez-Motilla JM, Mateu-Puchades A. Delayed hypersensitivity to topical and systemic corticosteroids. Contact Dermatitis. 2018 Jan;78(1):86-88. [CrossRef]

- Kounis NG. Kounis syndrome: a monster for the atopic patient. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2013; 3: 1-4. [CrossRef]

- May JE, Allen AL, Samuelson Bannow BT, O'Connor C, Sylvester KW, Kaatz S. Safe and effective anticoagulation use: case studies in anticoagulation stewardship. J Thromb Haemost. 2025; 23: 779-789. [CrossRef]

- López Ortego P, Queiruga Parada J, Bravo Gallego L. Y, Gómez Traseira C, Arreo V, Rey J, Rodríguez Mariblanca A, Seco Meseguer E, González-Muñoz M, Ramírez E. Utility of a computer tool for detection of potentially inappropriate medications in older patients in a tertiary hospital. IBJ Clin Pharmacol 2020; 1: e0015.

- Almeqdadi M, Aoun J, Carrozza J. Native coronary artery thrombosis in the setting of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2018; 2: yty138. [CrossRef]

- Leung LWM, Gallagher MM, Evranos B, Bolten J, Madden BP, Wright S, Kaba RA. Cardiac arrest following protamine administration: a case series. Europace. 2019 Jun 1;21(6):886-892. [CrossRef]

- Canpolat U. Aware of the evils of life-saving antidote of heparin: clues from 12-lead electrocardiogram during protamine-mediated adverse events. Europace. 2019; 21: 991. [CrossRef]

- Leung LWM, Gallagher MM. Aware of the evils of life-saving antidote of heparin: clues from 12-lead electrocardiogram during protamine-mediated adverse events-Authors' reply. Europace. 2019; 21: 991-992. [CrossRef]

- Amro M, Mansoor K, Amro A, Okoro K, Okhumale PI. Kounis Syndrome Induced by Protamine Sulfate. Cureus 2020; 12: e6972. [CrossRef]

- Itoh T, Kanaya Y, Komuro K, Sugawara S, Ishikawa Y, Onodera M, Goto I, Fusazaki T, Nakamura M. Kounis syndrome caused by protamine shock after coronary intervention: A case report. J Cardiol Cases. 2021; 25: 23-25. [CrossRef]

- Papavramidou N, Christopoulou-Aletra H. Medicinal use of leeches in the texts of ancient Greek, Roman and early Byzantine writers. Intern Med J. 2009; 39: 624-7. [CrossRef]

- Kleisiaris CF, Sfakianakis C, Papathanasiou IV. Health care practices in ancient Greece: The Hippocratic ideal. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014; 15: 7: 6.

- Abdualkader AM, Ghawi AM, Alaama M, Awang M, Merzouk A. Leech therapeutic applications. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2013; 75: 127-37.

- Wanandy T, Bradley I, Tovar Lopez CD, Cotton BTB, Handley SA, Mulcahy EM, Adriana Le TT, Lau WY. Leech-bite induced anaphylaxis with or without Hymenoptera venom sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024; 12: 2877-2880.e4. [CrossRef]

- Çakmak T, Çaltekin I, Gökçen E, Savrun A, Yas¸ar E. Kounis syndrome due to hirudotherapy (leech therapy) in emergency department: a case report. Turk J Emerg Med 2018; 18: 85-7.

- Tas S, Yildiz BS, Ersin A, Tas U. Time to Reconsidering the Potential Role of Leech Salivary Proteins in Medicine: Type-II Kounis Syndrome Triggered by Leech Bite. Pak J Med Sci. 2025; 41: 341-343. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas G. Kounis, Alexandros Stefanidis, Ming-Yow Hun, Ugur Ozkan, Cesare de Gregorio, Alexandr Ceasovschih, Virginia Mplani, Christos Gogos, Stelios F. Assimakopoulos, Christodoulos Chatzigrigoriadis et al. From Acute Carditis, Rheumatic Carditis, and Morphologic Cardiac Reactions to Allergic Angina, Allergic Myocardial Infarction, and Kounis Syndrome: A Multidisciplinary and Multisystem Disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2025; 12: 325. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).