1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) describes a group of conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels, which includes coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, or heart failure[

1]. CVD is the world’s biggest killer, causing 1 in 3 deaths globally and 20.5 million deaths in 2021[

2]. In the UK, 7.6 million people live with CVD and it accounts for 26% of all UK deaths, amounting to £12 billion in healthcare costs annually[

3].

Part of best-practice cardiovascular care is to offer cardiac rehabilitation (CR) to patients following a cardiac event[

4,

5]. CR is a secondary prevention programme designed to help individuals recover from a cardiac event and reduce their risk factor status to prevent any subsequent cardiac events. This is largely achieved through medically supervised exercise, as well as education on key topics such as smoking cessation, healthy diet, medication compliance and stress management[

6]. It has been demonstrated to effectively reduce emergency department visits, hospital admissions and mortality by 20-26%, as well as improve social and mental wellbeing[

7,

8], and is therefore a valuable approach to help alleviate the burden CVD presents.

While much progress has been made to help reduce death rates from CVD, several inequalities exist in CVD outcomes due to factors such as socioeconomic status, sex and ethnicity[

9]. Ethnic minorities face increased risk of mortality and morbidity from CVD due to cardiometabolic, lifestyle and socioeconomic risk factors[

10,

11]. CR attendance often remains significantly lower than age and gender match counterparts among ethnic minorities across several Western countries such as the UK, USA, Canada and Australia despite its numerous documented benefits[

8,

11,

12]. This is despite meta-analytical data showing significant health improvements and reduced mortality and morbidity for ethnic minority groups who attend CR[

13].

There is currently limited research evaluating culturally competent models of CR specifically designed to encourage attendance and adherence for ethnic minorities. Currently only one scoping review has assessed culturally adapted CR education for ethnic patients with heart disease, finding that these interventions show promise in improving cardiac outcomes among ethnic minority patients[

14]. Further reviews of adapted interventions are needed to understand the complex barriers facing ethnic minorities. For instance, research has identified barriers that require further understanding include cultural, language, religion, socioeconomic status and lack of knowledge from stakeholders[

11,

15]. A mixed methods-based review would be well placed to bring this information together as it can consider both the impact of interventions and identify the factors that influence that impact. By integrating both forms of data, this review can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how culturally adapted CR programmes impact ethnic minority patients[

16].

Therefore, the aims of this review are to 1) identify research that has developed and evaluated culturally sensitive CR, and 2) describe the cultural adaptations in these interventions and their effectiveness to help establish key uptake facilitators for ethnic minorities.

2. Methods

A convergent segregated mixed methods review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for mixed methods systematic reviews [

17].

2.1. Search Strategy

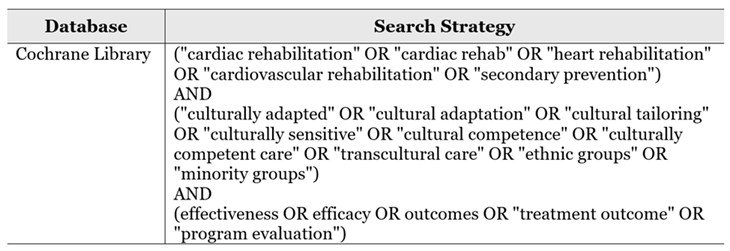

A systematic search[

18] was conducted by two blind reviewers between January 2025 – June 2025. Nine electronic databases were searched including; Amed, CINAHL Plus, PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Medline, Scopus, SPORTDiscus and Web of Science from inception to June 2025. These databases were chosen due to their coverage of health and medical research. An example of the search strategy can be found in

Table 1. There were no filters applied regarding publication date, study design or language. Additionally, grey literature was searched using the Grey Matters search engines, the first 20 pages of three search engines (ProQuest, Google Scholar and ScienceDirect) were considered for additional articles and the reference lists of included studies and relevant articles were searched to identify eligible papers.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were established based on the PICOS acronym (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study design and other) terms.

2.2.1. Population

Studies were included if they involved adult male or female patients eligible for CR that belong to an ethnic, cultural or racial group with a distinct language, traditions or customs that differ from the majority population in the study country. Studies with multi-ethnic participants were also included if the CR intervention included adaptations targeted to an ethnic, cultural or racial group involved in the study. Studies involving participants under 18 or who did not have heart disease were excluded.

2.2.2. Intervention

Studies that involve a CR programme containing cultural adaptations tailored to the target population(s) were included. Studies were excluded if they described a CVD primary prevention programme rather than CR, detailed another rehabilitation programme such as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), or described an intervention protocol that has not yet been conducted or assessed.

2.2.3. Comparator

Studies with standard treatment controls, active or inactive controls were included.

2.2.4. Outcome(s)

Studies were included if they reported outcomes related to the experience of or views regarding a specifically named culturally tailored CR service or intervention. Outcomes could include programme utilisation (referral, attendance, adherence), risk factor improvement, or patient perspectives.

2.2.5. Study Design and Other

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods study designs were included in this review to reflect the many approaches of assessing CR outcomes[

19]. Only articles available in English were included in this review due to the author’s language proficiency and because no means of translating articles existed.

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

Search results were imported into Covidence for screening and removal of duplicates[

20]. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers, manually removing any duplicates not identified by Covidence. Potential studies were then reviewed in full-text and included/excluded based on the eligibility criteria. A third reviewer (librarian) was available to assist with disagreements. No disagreements were identified.

Data from the included studies was then extracted by an independent reviewer inputting relevant information into a self-developed Excel spreadsheet, which contained categories such as study design, sample size and population, intervention characteristics, cultural adaptations described, outcomes measures, and key findings.

2.4. Quality Appraisal and Confidence in Findings

Selected studies were critically appraised by one reviewer using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018[

21]. This tool was selected as the papers included in this study had diverse study designs, as it enables assessment of methodological quality across qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods designs. Studies received a quality score out of 5 based on the number of key methodological criteria met for their respective study design - a higher score indicates stronger quality.

Two tools were used to identify confidence in findings. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence (OCEBM)[

22] was used to determine the strength of quantitative evidence presented within the review of quantitative studies. The CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) approach was used to assess confidence in qualitative studies[

23].

2.5. Synthesis and Integration

A narrative synthesis was conducted due to the variability of study designs and outcomes. Data was integrated using a convergent segregated approach as outlined in the JBI approach to mixed method systematic reviews[

17]. Cohen’s d was calculated to determine effect sizes in quantitative data where possible[

24].

3. Results

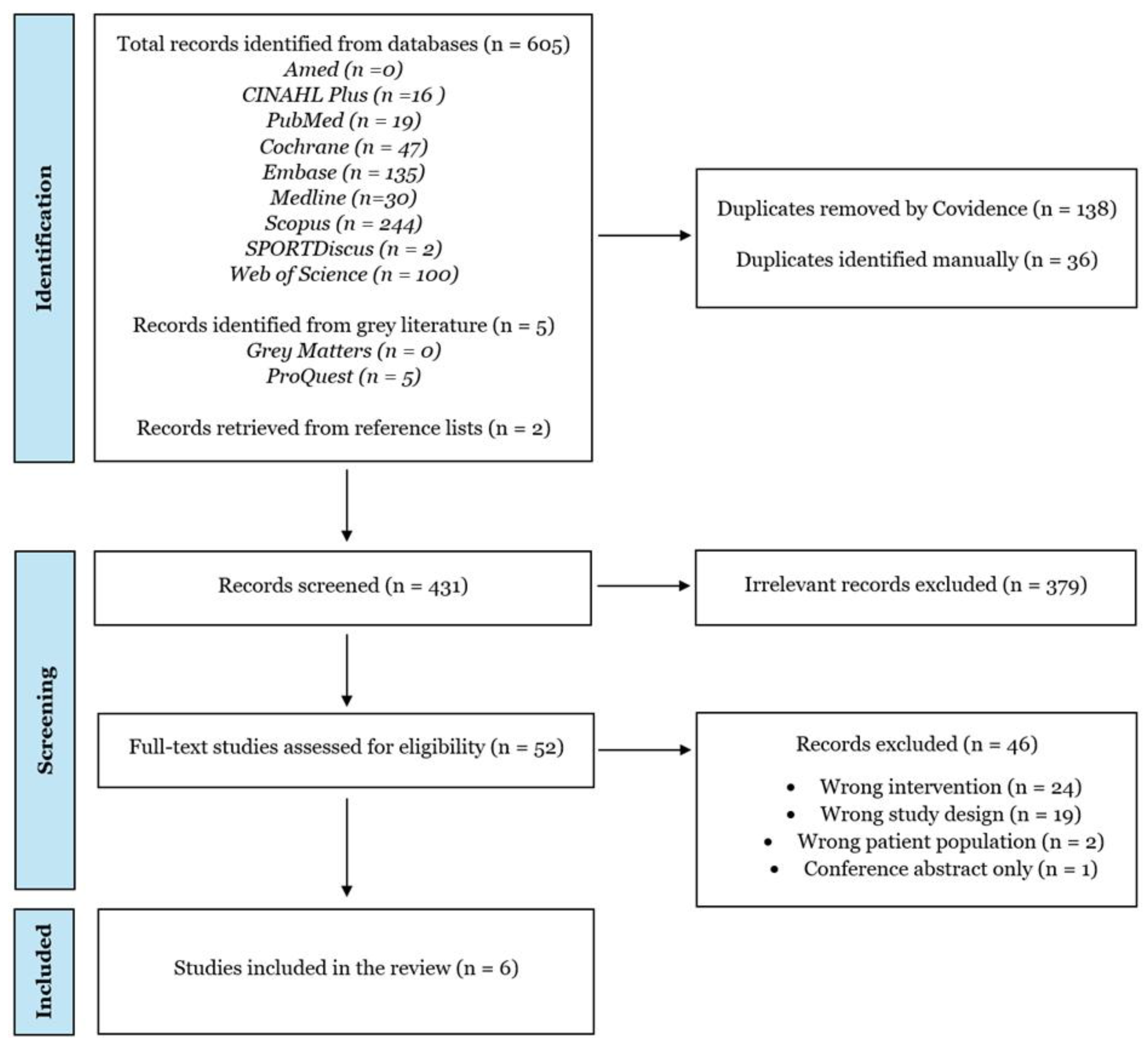

3.1. Study Selection

The database search yielded a total of 605 studies. An additional 2 papers were identified from reference lists of relevant systematic reviews. After duplicate removal, and title and abstract screening, 52 full-text manuscripts were assessed for eligibility. This led to a total of 6 studies being included in this review[

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Figure 1 details the search and selection process of the total studies.

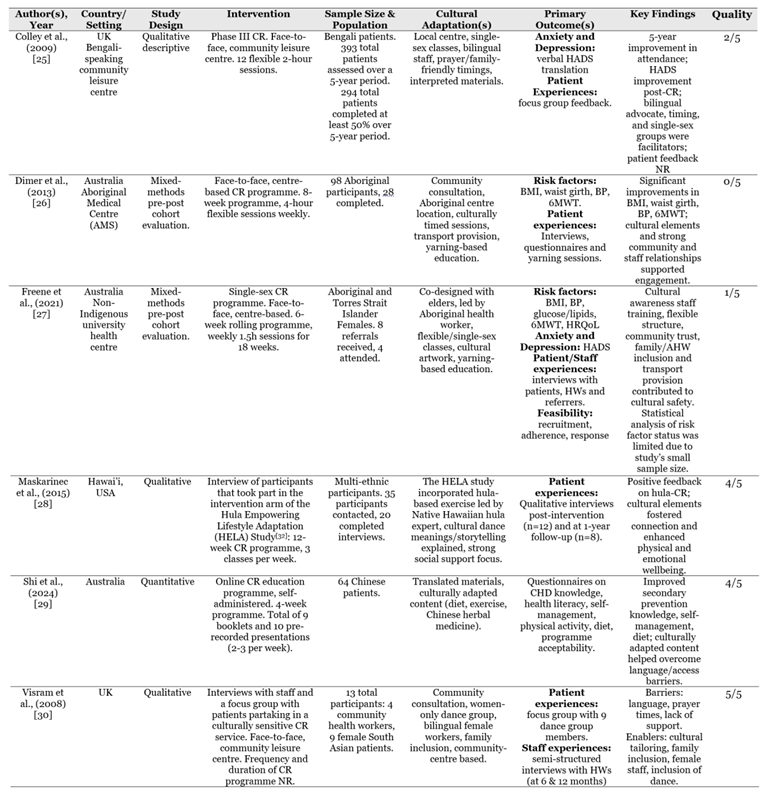

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of all six studies. The included studies had various study designs: three were qualitative, two were mixed methods and one was quantitative. Studies were conducted in Australia (n=3), the United Kingdom (n=2), and the United States (n=1). There were 423 participants in total. A majority of the total participants was made up by Colley et al[

25] which had 294 total participants completing CR over the course of 5 years. Of the papers that reported gender demographics, a total of 98 participants were female and 97 were male. The gender of 228 participants was not reported.

Two studies included participants of South Asian backgrounds (n=303)[

25,

30], two included Australian Aboriginals (n=32)[

26,

27], one had a Chinese immigrant population (n=64)[

29], and one involved a multi-ethnic population which included Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, Filipinos and Caucasians (n=NR)[

28].

Five studies had in-person CR interventions; four were centre-based[

25,

26,

27,

30] and one was hospital-based[

28]. One study involved an online self-administered CR education programme[

29]. CR sessions ranged from 4–12 weeks, with one study not reporting the CR programme duration.

3.3. Quality Appraisal and Confidence in Findings

The overall methodological quality of the studies is moderate. Three studies were of low quality, scoring either 0, 1, or 2 out of 5. Three were of high quality, scoring either 4 or 5 out of 5. The full quality assessment can be found in Supplementary File 1.

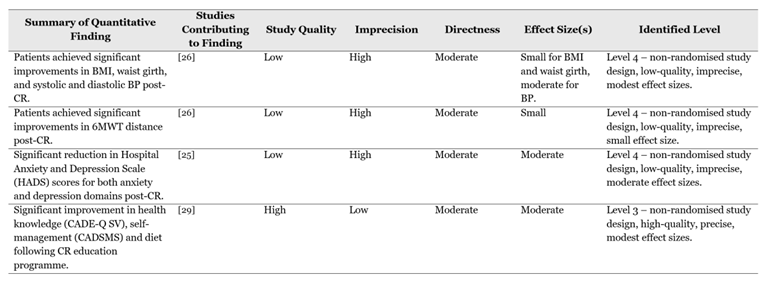

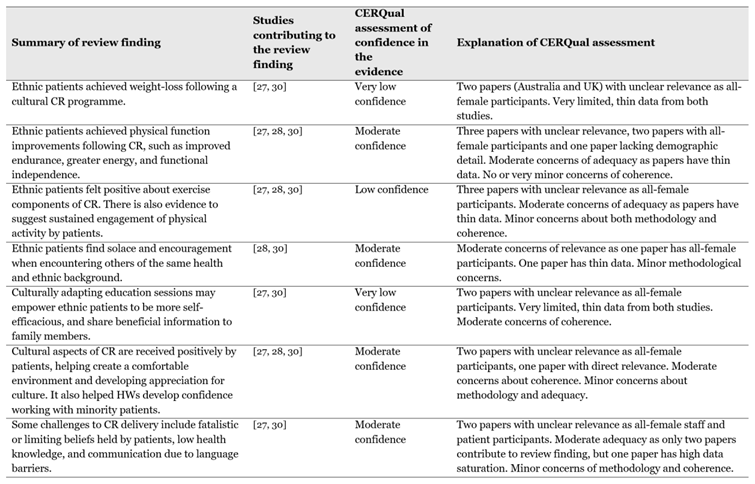

See

Table 3 for certainty of quantitative findings using OCEBM, and

Table 4 for a summary of qualitative findings assessed with CERQual; the full CERqual assessment can be found in the Supplementary File 2.

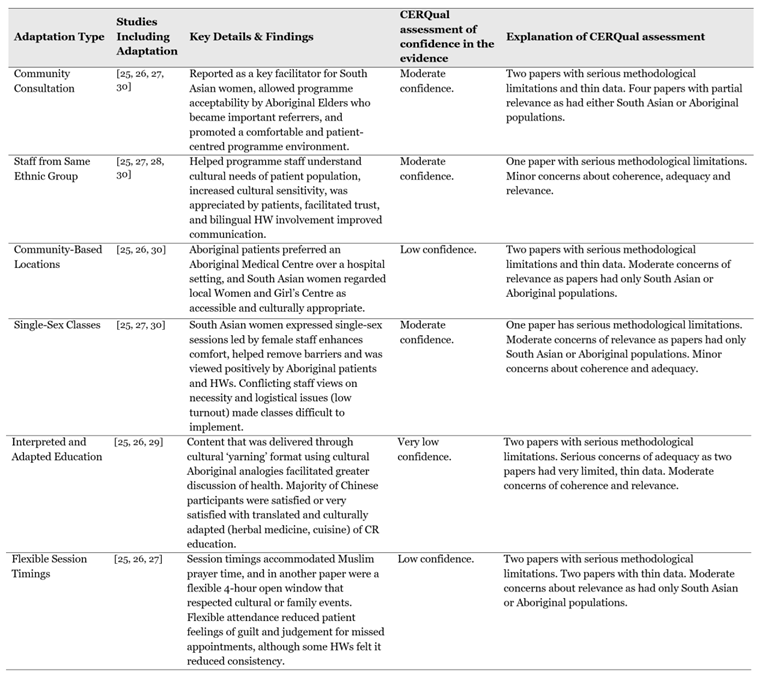

3.4. Cultural Adaptations

Six major types of cultural adaptations were described in the studies.

Table 5 provides a summary of these adaptations and the CERQual assessment for each finding.

3.4.1. Community Consultation

Community consultation to inform service design was described in four papers[

25,

26,

27,

30], which was reported to be a key facilitator for participation in South Asian women[

30] and helped promote programme acceptability with Aboriginal community elders which then became an important referral source[

26]. Freene et al[

27] reported this helped the programme environment feel more comfortable for patients, and Colley et al[

25] described this to be key in making the programme more patient-centred.

3.4.2. Staff From The Same Ethnic Group

Four studies had healthcare workers (HWs) involved in the programme that belonged to the same ethnic group as the patients[

25,

27,

28,

30]. The cultural expertise that was provided by them was appreciated by patients[

28], and their involvement helped other programme workers improve their understanding of the patient population[

25], facilitated trust with patients[

27] and increased the cultural sensitivity of the programme[

25,

30]. The use of HWs that were fluent in the patient’s language improved communication with patients through interpretation of educational talks[

25] and allowing patient experiences to be heard[

30].

3.4.3. Local Community-Based Locations

Three studies describe their CR programme taking place in a local community centre[

25,

26,

30]. The use of an Aboriginal Medical Centre was strongly preferred by Aboriginal patients compared to a hospital base and felt more culturally secure[

26]. The CR programme described in Visram et al[

30] took place in a local Women and Girl’s Centre which was regarded by female South Asian patients as familiar, accessible and culturally appropriate, and they felt this contributed to the programme’s success.

3.4.4. Single-Sex Classes

Three studies incorporated single-sex CR classes[

25,

27,

30]. Visram et al[

30] describe developing a successful women’s dance group that was informed by South Asian female patients expressing they would feel more comfortable attending single-sex sessions led by a female staff member. Freene et al[

27] describe more conflicting results; making a gender-specific CR programme was viewed positively by referrers, Aboriginal patients and an Aboriginal HW, however some HWs questioned its necessity, although the authors do not describe why. Colley et al[

25] reported that single-sex classes helped remove barriers to CR attendance. Although low numbers meant some classes had to be cancelled altogether. The authors speculate that a women-only centre compared to a mixed-gender venue may improve attendance.

3.4.5. Interpreted and Adapted Education

Three studies interpreted or adapted education sessions or content to be more relevant to the patient population[

25,

26,

29]. Colley et al[

25] utilised bilingual advocates to interpret education sessions that were delivered by HWs. Dimer et al[

26] incorporated Aboriginal culture into analogies used to promote physical activity, and delivered sessions through the Aboriginal process of ‘yarning’, which was described as respectful and allowed greater discussion and opportunity for patients to address health-related behaviours. Shi et al[

29] translated Cardiac College™, an online CR education resource developed by CR professionals, into simplified Chinese, and adapted content to be more culturally relevant; for example, dietary advice included Chinese cuisine, and Chinese herbal medicine was included instead of vitamins and supplements as that is more commonly used by the Chinese community. The majority of patients were satisfied (53.1%) or very satisfied (46.9%) with the content, and 64.1% of patients found it useful.

3.4.6. Flexible Session Timings

Three studies incorporated flexible and culturally informed session timings for their CR programmes[

25,

26,

27]. Colley et al[

25] ensured timings did not interfere with Muslim prayer times as the majority of patients were Muslim. Dimer et al[

26] conducted sessions with a 4-hour open window where patients could choose when to come in and carried them out midweek to avoid conflict with funerals, cultural or family events. Freene et al[

27] incorporated a flexible system where patients did not have to attend consecutive sessions if they have familial or cultural commitments to attend to; this was reported to be highly valued by patients as a less rigid structure reduced feelings of guilt and judgement for being unable to attend, although some HWs argued that the lax structure does not encourage consistency.

3.5. Physical Health

3.5.1. Physiological Markers

Two studies evaluated physiological changes using measures of BMI, BP and waist circumference[

26,

27]. Freene et al[

27] did not report any statistical outcomes post-CR for Aboriginal female patients, and authors caution interpretation of their data due to the study’s small sample size (n=4). Dimer et al[

26] found significantly improved BMI (p<0.05, d=0.14), waist girth (p<0.01, d=0.25) and systolic (p<0.01, d=0.75) and diastolic (p<0.05, d=0.5) blood pressure in Aboriginal male and female patients post-CR. They also reported a non-significant decrease in body weight (p=0.09, d=0.09).

Two qualitative findings indicate that patients perceived improvements in body weight. Freene et al[

27] describe that one Aboriginal female participant reported she was able to achieve weight-loss following the cultural CR programme where other interventions had failed, and Visram et al[

30] describe South Asian female patients taking part in a women’s dance group felt it helped them lose weight.

3.5.2. Physical Function and Capacity

Dimer et al[

26] evaluated exercise capacity using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), finding significant improvement in 6MWT distance (p<0.01, d=0.43), for Aboriginal male and female participants post-CR. While Freene et al[

27] also measured 6MWT, they did not report any statistical outcomes post-CR.

Shi et al[

29] evaluated physical activity in Chinese patients using self-reported average moderate-intensity exercise per week and calculating patients’ average daily step-count over 9 days using devices such as Apple Watch or Fitbits. No significant improvement was found in the weekly amount of moderate-intensity exercise (p=0.829, d=0.03) or average daily step-count (p=0.216, d=0.08) from pre to post intervention. This paper evaluated an online CR education programme with no supervised physical activity portion, unlike all other papers included in the review, and had the shortest intervention duration of 4-weeks. The absence of supervised, in-person exercise sessions and the relatively short intervention time may have contributed to the lack of change in physical activity from pre to post intervention seen in these participants.

Qualitative findings indicate physical function improvements in patients. Maskarinec et al[

28] report that patients engaging in hula-based CR described feeling improved endurance, strength, coordination and flexibility. South Asian women in Visram et al[

30] described feeling greater energy and reduced symptoms from other comorbidities besides heart disease after taking part in the dance programme. In Freene et al[

27] patients describe the ability to walk farther with less effort and achieving greater functional independence post-CR, with one HW describing a patient began shopping independently where before she would have to rely on others to do this for her.

3.5.3. Perceptions of Exercise Interventions

Qualitative evidence suggests patients felt positively about the exercise components of CR. Freene et al[

27] report that Aboriginal patients enjoyed implementing activity recommendations, and Visram et al[

30] describes that South Asian women found a dance class fun and suitable, and deemed the physical health benefits of CR to be the key motivator for their attendance.

There is also qualitative evidence to suggest sustained engagement of physical activity by patients. Both Maskarinec et al[

28] and Visram et al[

30] report patients continuing to incorporate exercise at home by following a beat while completing household activities[

30], or replaying songs used in the programme a year later and still dancing to them[

28].

3.5.4. Summary of Evidence

Findings indicate that ethnic patients can achieve risk factor improvements from culturally adapted CR. One study demonstrated significant improvements in BMI, BP and waist circumference; however this evidence is considered Level 4 due to a low-quality study design and only modest effect sizes - as such, only limited confidence can be placed in the findings, and results should be interpreted with caution. Qualitative data suggests patients experienced weight-loss, however there is low confidence in this finding due to serious concerns regarding data adequacy and relevance.

Culturally adapted CR may improve physical function in ethnic patients. Qualitative data indicates patients describe improvements in endurance, energy and functional independence - there is moderate confidence in this finding due to concerns regarding relevance and data adequacy. Quantitative findings are mixed - one low-quality study demonstrated significant improvements in 6MWT distances with small effect size (p<0.01, d=0.43), while a high-quality study found no change in physical activity. The quantitative evidence in this domain is overall Level 4, therefore only limited confidence can be placed in the findings, and results should be interpreted with caution.

Qualitative data suggests ethnic minority patients viewed the exercise components of CR positively, with some evidence of sustained engagement in physical activity following programme completion, however there is low confidence in this finding due to serious concerns about relevance and moderate concerns regarding data adequacy and coherence.

3.6. Psychosocial Health

3.6.1. Anxiety and Depression

Two studies evaluated patient anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[

25,

27], however one study had too small of a sample size to conduct statistical interpretation[

27]. In Colley et al[

25], the HADS scores of 20% of patients who completed the programme were randomly selected for analysis, finding significant reduction in anxiety (p=0.001, d=0.56) and depression (p=0.03, d=0.48) post-CR.

3.6.2. Peer Support

Findings from qualitative papers describe how when patients engaged in a shared activity with individuals from the same background, it helped foster connection and compassion[

28], and helped reduce stress and social isolation[

30].

3.6.3. Summary of Evidence

One study showed significant improvements in HADS scores for anxiety (p=0.001, d=0.56) and depression (p=0.03, d=0.48), suggesting ethnic patients may experience reduced anxiety and depression following culturally adapted CR. This is considered Level 4 evidence due to low study quality and moderate effect sizes - limited confidence can be placed in the findings, and caution should be taken when interpreting results.

Qualitative data suggests culturally adapted CR provides social benefits, as patients indicate they find solace and encouragement when encountering others of the same health and ethnic background. There is moderate confidence in this finding due to moderate concerns about relevance and data adequacy.

3.7. Health-Related Behaviours

3.7.1. Health Knowledge and Self-Management Behaviour

Shi et al[

29] reported significant improvements in CHD secondary knowledge measured using the short-form Coronary Artery Disease Education Questionnaire (CADE-Q SV) (p<0.05, d=0.65), self-management behaviours using the Coronary Artery Disease Self-Management Scale (CADSMS) (p<0.001, d=0.59), and diet assessed by patient-self-reported daily average fruit and vegetable servings (p<0.001, d=0.5).

3.7.2. Confidence and Engagement With Health Knowledge

Data from qualitative findings indicate that culturally-informed education sessions facilitated more patient-led discussions of health for Aboriginal patients, with both patients and HWs feeling that patients’ health literacy had improved as they became more confident to seek health advice[

27]. Patients in both Freene et al[

27] and Visram et al[

30] describe going on to educate family members about the information learned during the programme.

3.7.3. Summary of Evidence

Quantitative data suggests culturally adapted CR education improved patients’ CHD knowledge and self-management behaviours. This evidence is considered Level 3 as it is a high-quality cohort study, however its non-randomised design and moderate effect sizes mean the findings should still be interpreted with some caution.

Qualitative findings indicate that making education talks more relevant to individuals of different ethnic backgrounds may empower them to be more self-efficacious, and help not only themselves but also their family members make healthier lifestyle choices. However, there is low confidence in this finding due to serious concerns about data adequacy and relevance, and moderate concerns about coherence.

3.8. Patient and Staff Overall Perception

Five studies reported gathering patient experiences, however only three studies detail these in their results[

27,

28,

30]. In these three studies, experiences were gathered through a focus group with patients[

30], unstructured interviews[

27], and loosely structured interviews immediately post-programme and at 1-year follow-up[

28]. Staff experiences (programme HWs and referrers) were also gathered in two of these studies through semi-structured interviews[

27,

30].

3.8.1. Positive Experiences of Cultural CR Programmes

The experiences described by patients relating to the cultural aspects of the respective CR programmes were largely positive. In Maskarinec et al[

28], patients emphasised the cultural Hawaiian elements incorporated in the programme made it particularly memorable, with patients finding these added emotional and spiritual benefits beyond physical health. They also report both Native and non-Native Hawaiians developed a deeper appreciation for Hawaiian culture following the programme. South Asian women in Visram et al[

30] felt the programme had a positive impact on their mental wellbeing. Freene et al[

27] report that Aboriginal female participants felt the cultural considerations were important and created a safe and comfortable environment.

Papers that evaluated staff experiences found that working within a cultural CR programme helped HWs develop skills and confidence to work with minority patients[

27]. They also identify that developing strong relationships and trust between patients and staff is key to patient engagement[

27,

30], however building these can take time[

27].

3.8.2. Challenges in CR Delivery

Freene et al[

27] identified fatalistic beliefs held by patients to be a major challenge for attendance in an Aboriginal population; HWs and referrers involved in this programme suggest trust should be built with this community to help mitigate this challenge, recommending building relationships with Aboriginal organisations and forming direct relationships with potential Aboriginal patients.

Staff in Visram et al[

30] identified other challenges and barriers within mainstream CR prior to implementation of their culturally adapted CR intervention; staff expressed that patients held limiting beliefs about physical activity being the cause of their chest pain that often prevented full participation, and that patients’ health knowledge was often low, with many staff making assumptions about what participants would know regarding human anatomy. Communication was also a major barrier, finding that the use of interpreters was rather distracting for both staff and patients attempting to listen to education talks - the involvement of a qualified, bilingual HW was able to aid communication within this programme instead[

30].

3.8.3. Summary of Evidence

Patients and staff generally reported positive experiences of culturally adapted CR programmes; patients appreciated cultural elements and felt this contributed to a sense of safety, and staff in one study reported the programme helped improve their confidence working with an ethnic minority group. There is moderate confidence in this finding due to moderate concerns regarding coherence and relevance.

Staff describe experiencing challenges within CR services such as fatalistic or limiting beliefs among patients, poor health knowledge and communication due to language barriers within CR services. There is moderate confidence in this finding due to serious concerns about relevance and moderate concerns about data adequacy.

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Key Findings

This review is the first mixed methods review describing and evaluating culturally adapted CR delivery, which is currently an area with limited research. The evidence presented in this review demonstrates that culturally adapted CR interventions are received positively, provide further spiritual and emotional benefits, and have the potential to enhance engagement and motivation. Previous research helped identify that culturally tailored CR education interventions show promise in improving health knowledge, risk factor status and self-care behaviours among Hispanic, Italian and Greek populations[

14]. This review has expanded these findings by showing culturally adapted CR can also improve outcomes among Aboriginal, South Asian, Chinese, Filipino, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders populations.

The main cultural facilitators identified in this review include community collaboration to inform service design, utilisation of staff who are either bilingual or share the same cultural background as the patient population and incorporation of single-sex classes. These adaptations help address commonly reported barriers to CR participation, such as language barriers[

11,

15], and discomfort exercising in mixed-gender classes often felt by ethnic women[

33]. Previous research has also identified bilingual and cultural staff to be an element that ethnic patients appreciate in rehabilitation programmes[

10,

34]. Many ethnic individuals face linguistic barriers, creating disadvantages in communication that must be thoughtfully addressed. Relying on family members to bridge communication may be inefficient as clinical messages could be misinterpreted due to confusing medical jargon, however the use of interpreters may also be distracting[

30]; incorporating bilingual staff in programme delivery has been identified in this review to both facilitate communication, and enhance the cultural sensitivity of the programme, and could be a consideration for future CR designs. Cultural staff and single-sex classes are elements also recommended in NICE guidelines[

5]. However, implementation of single-sex classes would require further considerations such as demand and venue availability, as these were identified as challenges within the papers.

The review findings indicate that ethnic patients are able to receive risk factor improvements and physical health benefits from CR, which is in line with previous research demonstrating that CR services provide important health benefits to these populations[

13,

35]. Culturally adapted CR can therefore help alleviate CVD burden among ethnic populations by providing more tailored access to crucial care. Most papers within this review incorporated supervised exercise sessions and many found positive benefits to patients’ physical health, whereas one paper that did not include this within their programme found no change in physical activity among patients[

29]. Previous research has also shown that ethnic minority patients show preference for supervised sessions with healthcare professionals[

15], indicating the importance of providing a dedicated, supervised exercise component to encourage a sense of safety and uptake amongst these populations.

The qualitative findings in this review describe positive patient experiences of culturally adapted CR, indicating such interventions to be enjoyable and beneficial. Enjoyment positively influences physical activity levels[

36,

37], therefore ensuring the programme is enjoyable could be important for encouraging exercise within ethnic populations, particularly ethnic women as they tend to have lower levels of physical activity[

38]. Enjoyment can be enhanced through providing a range of exercises for patients with tailored support[

37]. For example, adapting the exercise component of CR to incorporate dance seemed to encourage exercise maintenance following programme completion in two papers within this review[

28,

30]. Similarly, a hula-based hypertension prevention programme found higher retention rates compared to conventional exercise[

39]. Studies have shown dance-based exercise within CR may be comparable to conventional exercise in improving risk factor status, exercise capacity, lower limb strength and quality of life[

39,

40,

41]. Dance-based exercise may therefore be a creative and suitable exercise adaptation that can encourage enjoyability, engagement and sustainability of physical activity among ethnic patients.

Another main finding was the positive impact on emotional health through reducing feelings of loneliness and isolation. Previous research of ethnic patient experiences of CR found that peer support encourages motivation and contributes to enjoyability and successfully completing CR[

42]. Strong social support is also crucial in mitigating anxiety and depression, which are both factors associated with increased risk of CHD development and mortality[

43,

44]. Therefore, culturally tailored CR services could provide a safe environment for ethnic groups to form social bonds that enhance mental wellbeing, and encourage attendance and compliance.

4.2. Limitations of Review

The findings of this review should be interpreted with some caution as there was only moderate or limited confidence in data due to low methodological quality of studies, small to moderate effect sizes and papers lacking detail of outcomes and data analysis methods. Furthermore, none of the research included in this review were randomised control trials (RCTs) with a comparator group, meaning it is difficult to establish a causal effect between culturally adapted CR and the findings presented. However, while RCTs provide methodological rigor, this study design could be alienating for ethnic communities[

27,

45], meaning pre-post cohort evaluations may be the more appropriate choice for assessing targeted interventions. Moreover, the diverse ethnic groups included within this review will have unique social, economic and cultural contexts within Western countries[

46], presenting a challenge when making comparisons between groups. A limited range of ethnic groups were included within this review, excluding several other prominent populations within Western countries and thereby reducing generalisability.

Limitations also exist within the systematic review process. The evidence included is limited to the databases selected for search as well as only English-language papers, which could have reduced the scope of literature identified. Critical appraisal was also carried out by only one reviewer, which may introduce some bias. Moreover, the highly variable methodological approaches and outcome measures of the included studies made meta-analysis unfeasible, which could have provided a more comprehensive analysis of the findings.

4.3. Limitations of Studies

While the qualitative data describing patient experiences identified several perceived benefits to physical, social and mental wellbeing, there is little high quality quantitative data to support these claims. Most of the included studies did not assess patients’ risk factor status; only one study of low quality reported significant improvements in BMI, waist girth, BP and exercise capacity with modest effect sizes[

26] and another had too small of a sample size to conduct statistical analyses[

27]. Similarly, only one low quality study reported significant improvements in HADS scores[

25]. This indicates a gap of high-quality studies in the literature regarding risk factor profiles, quality of life and mental health data which future studies should focus on. There should also be more research on service utilisation, such as uptake and referral rates, compared to standard care to gather information on service feasibility and sustainability.

Another common hindrance to CR uptake and adherence among ethnic minorities is religion[

11,

15,

33]. While arranging session times to not conflict with religious practices was considered in Colley et al[

25], many studies in this review do not detail further faith-based considerations. Many ethnic groups hold a strong religious identity, and can often hold fatalistic beliefs and prioritise faith over medical advice when making health-related lifestyle choices[

15,

47]; such beliefs must be addressed sensitively in order to better support patients. Freene et al[

27] recognised fatalistic beliefs held by patients to be a challenge that inhibits motivation to attend CR - patients in this study recommended HWs forge strong relationships with community members and organisations to improve trust for the CR service. While this study was conducted with Aboriginal participants - limiting its generalisability - building relationships with religious leaders and organisations could present a means to help improve ethnic patients’ trust and health-seeking behaviours. Research has shown utilising religious organisations and places of worship can effectively enable wider outreach to ethnic minorities with strong religious identities[

48], thereby presenting a means to help improve CR attendance.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) such as health literacy, education and socioeconomic status are also known to impact patient outcomes[

49], however, these SDOH were not recorded and not explicitly considered in the design and implementation of the CR interventions included within this review. Low socioeconomic status and educational levels are associated with lower CR attendance[

6,

11,

15]. Therefore, alongside cultural and linguistic barriers, the social context surrounding patients plays an important role in their likelihood to attend or adhere to CR and should be a key consideration in future research, particularly as this can impact the long-term success of an intervention.

Another crucial consideration is the lack of knowledge many ethnic patients have of CR[

11,

15,

50], which is a system- and provider-level barrier that can result in patients not gaining access to relevant care. Dimer et al[

26] showed that by making a cultural CR programme accepted by Aboriginal Elders, these became an important referral source; this indicates that community collaboration, particularly with influential community leaders, can be a means to get across crucial information about the service to ethnic populations. However, more should be done to improve physician referral rates to these communities. Studies have shown inconsistencies in referral across some ethnic populations[

7,

49,

51], contributing to the disparities seen in CR attendance. Previous research has suggested strategies to mitigate this such as automatic CR referrals following patient discharge or staff liaisons to explain CR to patients prior to discharge[

51].

4.4. Implications for Practice, Policy and Future Research

The findings in this review indicate that culturally adapted CR shows promise in enhancing physical, mental and social wellbeing among ethnic minorities with cardiac disease. Several key facilitators have been identified, such as community consultation, cultural and bilingual staff, and use of a local community centre setting, which offer guidance on adapting CR programmes to be more culturally sensitive and appropriate to different ethnic minority groups. As ethnic minorities are at a higher risk of cardiac-related mortality, this should be a key focus of health professionals to enhance health equity across disadvantaged groups. CR services must also integrate strategies to mitigate barriers presented by patients’ faith, SDOH and lack of knowledge or referral from physicians to further enhance effects and longevity of such interventions. There is a clear need for further research of high quality to be conducted with comparisons to standard care, focusing on risk factor modification, quality of life, and service utilisation, to help strengthen the validity and confidence of the findings in this review. This can help establish whether culturally adapted CR can effectively tackle the barrier that ethnic minorities face in CR attendance and adherence.

5. Conclusions

This mixed methods review described and evaluated culturally adapted CR programmes for ethnic minority populations. The review findings suggest that cultural adaptations such as community collaboration during service design, involvement of bilingual or culturally matched staff and single-sex classes may support better engagement by ethnic minority patients. The evidence also indicates that culturally tailored CR has the potential to improve physical, social and mental wellbeing, with patients reporting largely positive experiences. However, confidence in these results is moderate due to a lack of high-quality studies and only limited quantitative data to support findings. Further high-quality research is required to more effectively assess the impact of culturally adapted CR on service uptake and patient outcomes. Nonetheless, this review provides valuable insight into a field with limited research that may guide the design of more culturally competent CR services to help address disparities and enhance cardiovascular care to underrepresented communities.

Funding

No financial are non-financial interests that directly or indirectly relate to this work are identified.

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgements are made.

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [Internet]. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- British Heart Foundation. Global Heart & Circulatory Diseases Factsheet [PDF]. 2025. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/for-professionals/research/heart-statistics/bhf-cvd-statistics-global-factsheet.pdf?rev=e61c05db17e9439a8c2e4720f6ca0a19&hash=6350DE1B2A19D939431D876311077C7B.

- British Heart Foundation. UK Fact Sheet [PDF]. 2025. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/for-professionals/research/heart-statistics/bhf-cvd-statistics-uk-factsheet.pdf?

- The National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation. National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NCP_CR) Report 2024 [PDF]. Available at: https://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/site/docs/NCP_CR%20Certification_Report_2024_Final.pdf.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute coronary syndromes: guidance [Internet]. 2020. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng185/chapter/Recommendations#cardiac-rehabilitation-after-an-mi.

- Filippini T, Malavolti M. Education and Disparities in Cardiac Rehabilitation Effectiveness. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2023 Nov 15;207:499. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos LR, Viramontes O, Bains NK, Zepeda IA. Disparities in cardiac rehabilitation among individuals from racial and ethnic groups and rural communities—a systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2019 Feb 15;6:1-1. [CrossRef]

- Galdas PM, Ratner PA, Oliffe JL. A narrative review of South Asian patients’ experiences of cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of clinical nursing. 2012 Jan;21(1-2):149-59. [CrossRef]

- World Heart Federation. World Health Report 2023: Confronting the World’s Number One Killer. 2023. Available at: https://world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/World-Heart-Report-2023.pdf.

- Ahmed F, Eberhardt J, van Wersch A, Ling J. Cultural influences on adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programmes: perspectives from South Asian healthcare professionals. International Journal of Therapy And Rehabilitation. 2022 Nov 2;29(11):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Vanzella LM, Oh P, Pakosh M, Ghisi GL. Barriers to cardiac rehabilitation in ethnic minority groups: a scoping review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2021 Aug;23:824-39. [CrossRef]

- British Heart Foundation. The National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation: Quality and Outcomes Report 2021 [PDF]. 2021. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/information-and-support/publications/research/nacr_report_final_2021.pdf?rev=fcfe3c330daf4a469e257d0fb2ba0f0e#page=8.99.

- Duggan S, Candelaria D, Zhang L, Ghisi G, Gallagher R. Mortality, morbidity, and cardiovascular risk factor outcomes from cardiac rehabilitation, in ethnic minorities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2022 Jul 1;21(Supplement_1):zvac060-045. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, de Melo Ghisi GL, Shi W, Pakosh M, Main E, Gallagher R. Patient education in ethnic minority and migrant patients with heart disease: a scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2024 Oct 23:108480. [CrossRef]

- Carew Tofani A, Taylor E, Pritchard I, Jackson J, Xu A, Kotera Y. Ethnic minorities’ experiences of cardiac rehabilitation: a scoping review. InHealthcare. 2023 Mar 4 (Vol. 11, No. 5, p. 757). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P, Loveday H. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI evidence synthesis. 2020 Oct 1;18(10):2108-18.

- JBI. 8.3 The JBI approach to mixed method systematic reviews [Internet]. 2024 March 26. Available at: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/355829259/8.3+The+JBI+approach+to+mixed+method+systematic+reviews.

- MacMillan F, McBride KA, George ES, Steiner GZ. Conducting a systematic review: A practical guide. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. 2019 Jan 13:805-26.

- Gough, D. Qualitative and mixed methods in systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2015 Dec;4:1-3. [CrossRef]

- McKeown S, Mir ZM. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Systematic reviews. 2021 Dec;10:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau M-C, Vedel I. Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group*. “The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2” [online]. Available at: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Colvin CJ, Garside R, Carlsen B. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation Science. 2018 Jan;13:1-0. [CrossRef]

- Aarts S, Van Den Akker M, Winkens B. The importance of effect sizes. The European Journal of General Practice. 2014 Mar 1;20(1):61-4. [CrossRef]

- Colley J, Whitfield D, Grayer J. Developing a culturally appropriate cardiac rehabilitation programme for Bengali speakers. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2009 Feb;4(2):81-5. [CrossRef]

- Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Cheetham C, Thomas T, Smith J, McManus A, Maiorana AJ. Build it and they will come: outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an Aboriginal Medical Service. Australian Health Review. 2012 Dec 21;37(1):79-82. [CrossRef]

- Freene N, Brown R, Collis P, Bourke C, Silk K, Jackson A, Davey R, Northam HL. An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cardiac Rehabilitation program delivered in a non-Indigenous health service (Yeddung Gauar): a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2021 May 1;21(1):222. [CrossRef]

- Maskarinec GG, Look M, Tolentino K, Trask-Batti M, Seto T, de Silva M, Kaholokula JK. Patient perspectives on the Hula Empowering Lifestyle Adaptation Study: benefits of dancing hula for cardiac rehabilitation. Health Promotion Practice. 2015 Jan;16(1):109-14.

- Shi W, Zhang L, Ghisi GL, Panaretto L, Oh P, Gallagher R. Evaluation of a digital patient education programme for Chinese immigrants after a heart attack. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2024 Aug;23(6):599-607. [CrossRef]

- Visram S, Crosland A, Unsworth J, Long S. Engaging women from South Asian communities in cardiac rehabilitation. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2008 Jul;15(7):298-305.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Look MA, Kaholokula JK, Carvhalo A, Seto T, de Silva M. Developing a culturally based cardiac rehabilitation program: the HELA study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2012;6(1):103-10. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan U, Baker D, Lester H, Edwards R. Exploring uptake of cardiac rehabilitation in a minority ethnic population in England: a qualitative study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2010 Mar;9(1):68-74. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee AT, Grace SL, Thomas SG, Faulkner G. Cultural factors facilitating cardiac rehabilitation participation among Canadian South Asians: a qualitative study. Heart & Lung. 2010 Nov 1;39(6):494-503. [CrossRef]

- Findlay B, Oh P, Grace SL. Cardiac rehabilitation outcomes by ethnocultural background: results from the Canadian Cardiac Rehab Registry. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2017 Sep 1;37(5):334-40.

- Henderson KA, Ainsworth BE. Enjoyment: A Link to Physical Activity, Leisure, and Health. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration. 2002 Dec 1;20(4).

- Hagberg LA, Lindahl B, Nyberg L, Hellénius ML. Importance of enjoyment when promoting physical exercise. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2009 Oct;19(5):740-7. [CrossRef]

- Im EO, Ko Y, Hwang H, Chee W, Stuifbergen A, Walker L, Brown A. Racial/ethnic differences in midlife women's attitudes toward physical activity. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2013 Jul;58(4):440-50. [CrossRef]

- Kaholokula JK, Look M, Mabellos T, Ahn HJ, Choi SY, Sinclair KI, Wills TA, Seto TB, de Silva M. A cultural dance program improves hypertension control and cardiovascular disease risk in Native Hawaiians: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2021 Oct 1;55(10):1006-18. [CrossRef]

- Vordos Z, Kouidi E, Mavrovouniotis F, Metaxas T, Dimitros E, Kaltsatou A, Deligiannis A. Impact of traditional Greek dancing on jumping ability, muscular strength and lower limb endurance in cardiac rehabilitation programmes. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2017 Feb 1;16(2):150-6. [CrossRef]

- Gomes Neto M, Menezes MA, Carvalho VO. Dance therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2014 Dec;28(12):1172-9. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh N, Fix GM, Allsup K, Charns M, McDannold S, Manning K, Forman DE. A qualitative study of participation in cardiac rehabilitation programmes in an integrated health care system. Military medicine. 2017 Sep 1;182(9-10):e1757-63. [CrossRef]

- Hughes JW, Tomlinson A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson J, Sketch Jr MH, Watkins LL. Social support and religiosity as coping strategies for anxiety in hospitalized cardiac patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004 Oct 1;28(3):179-85.

- Compare A, Zarbo C, Manzoni GM, Castelnuovo G, Baldassari E, Bonardi A, Callus E, Romagnoni C. Social support, depression, and heart disease: a ten year literature review. Frontiers in psychology. 2013 Jul 1;4:384. [CrossRef]

- Pressick EL, Gray MA, Cole RL, Burkett BJ. A systematic review on research into the effectiveness of group-based sport and exercise programmes designed for Indigenous adults. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2016 Sep 1;19(9):726-32. [CrossRef]

- Halder M, Binder J, Stiller J, Gregson M. An overview of the challenges faced during cross-cultural research. Enquire. 2016;8:1-8.

- Beattie JM, Castiello T, Jaarsma T. The importance of cultural awareness in the management of heart failure: a narrative review. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2024 Dec 31:109-23. [CrossRef]

- Khanji MY, Waqar S, Khawaja Z, Ali B. How delivering cardiopulmonary resuscitation and basic life support skills training through places of worship can help save lives and address health inequalities. [CrossRef]

- White-Williams C, Rossi LP, Bittner VA, Driscoll A, Durant RW, Granger BB, Graven LJ, Kitko L, Newlin K, Shirey M, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Addressing so.

- Scheppers E, Van Dongen E, Dekker J, Geertzen J, Dekker J. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Family practice. 2006 Jun 1;23(3):325-48.

- Mathews L, Brewer LC. A review of disparities in cardiac rehabilitation: evidence, drivers, and solutions. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and prevention. 2021 Nov 1;41(6):375-82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).