Introduction

Breast reconstruction has become an integral component of comprehensive breast cancer care with autologous microsurgical techniques offering superior long-term aesthetic and functional outcomes compared to implant-based reconstruction in many patients [

1]. With the passage of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1998 and the rise in breast conserving therapy, a growing group of patients present with breast reconstructive needs after prior radiation therapy, previous failed reconstruction, or both [

2,

3]. These patients represent a relatively high-risk cohort where the reconstructive landscape may be altered by compromised vascularity, scarred recipient sites, tissue fibrosis, and distorted anatomy resulting in elevated complication rates [

4,

5,

6,

7].

In these radiated and revision scenarios, microsurgical reconstruction remains not only feasible but often the most definitive and durable option [

8]. Advances in perforator flap techniques, alternative donor site utilization, and recipient vessel planning have expanded the reconstructive toolbox available to surgeons managing these high-risk cases. Further, intraoperative imaging technologies such as indocyanine green (ICG) angiography, and the widespread adoption of enhanced recovery protocols have additionally contributed to improved outcomes in this population [

9,

10,

11]. Nevertheless, the challenge of these patients demands careful preoperative planning, surgical adaptability, and diligent postoperative management. This review provides a comprehensive overview of current microsurgical strategies for breast reconstruction in post-radiation and revision settings and offers a practical framework for breast reconstructive surgeons facing these challenging clinical scenarios.

Patient Evaluation and Risk Stratification

Successful microsurgical breast reconstruction in the post-radiation or revision setting begins with rigorous patient evaluation and individualized risk stratification. A structured preoperative assessment is essential to guide surgical planning, minimize complications, and set realistic expectations. Particular attention should be paid to radiation history (total dose, timing, modality, and associated skin changes), prior reconstruction (implant-based, autologous, or hybrid techniques; any prior flap failures, infections, or explantations), surgical scars (chest wall incisions, port sites, or history of vascular access that may influence recipient vessel availability), and comorbid conditions (smoking, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and/or prior thromboembolic events). Noninvasive imaging also plays an important role in preoperative evaluation and operative planning. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is the gold standard for perforator mapping and donor site assessment and can also aid in evaluating internal mammary and thoracodorsal donor vessels if there is any reason for concern [

12]. It is important to note that the timing of the study relative to contrast administration is very important for optimal perforator and vessel mapping, and we recommend finding and using specific radiologists and radiology technologists experienced in performing this type of study whenever possible. Some authors also advocate for the use of color duplex ultrasound (CDU) for preoperative flap planning and design though we do not perform this [

13].

Patient risk stratification can be broadly based on systemic and local factors. High-risk systemic factors include active smoking or nicotine use, poorly controlled diabetes, morbid obesity, recent chemotherapy (<6 weeks), chronic steroid use and/or history of thromboembolic or hypercoagulable states. High-risk local factors include prior chest wall radiation, previous flap or axillary dissection, history of infected or exposed implants, severe capsular contracture, or thin mastectomy skin flaps [

14]. A thorough risk assessment should guide decision making, and patients with multiple risk factors may benefit from a more staged approach. Whenever possible, prehabilitation by addressing modifiable risk factors such as smoking cessation or glycemic control should be pursued. Additionally, any new or chronic wounds noted on evaluation, especially in the setting of prior radiation, must be formally analyzed by surgical pathology for possible breast cancer recurrence.

Flap Selection and Design

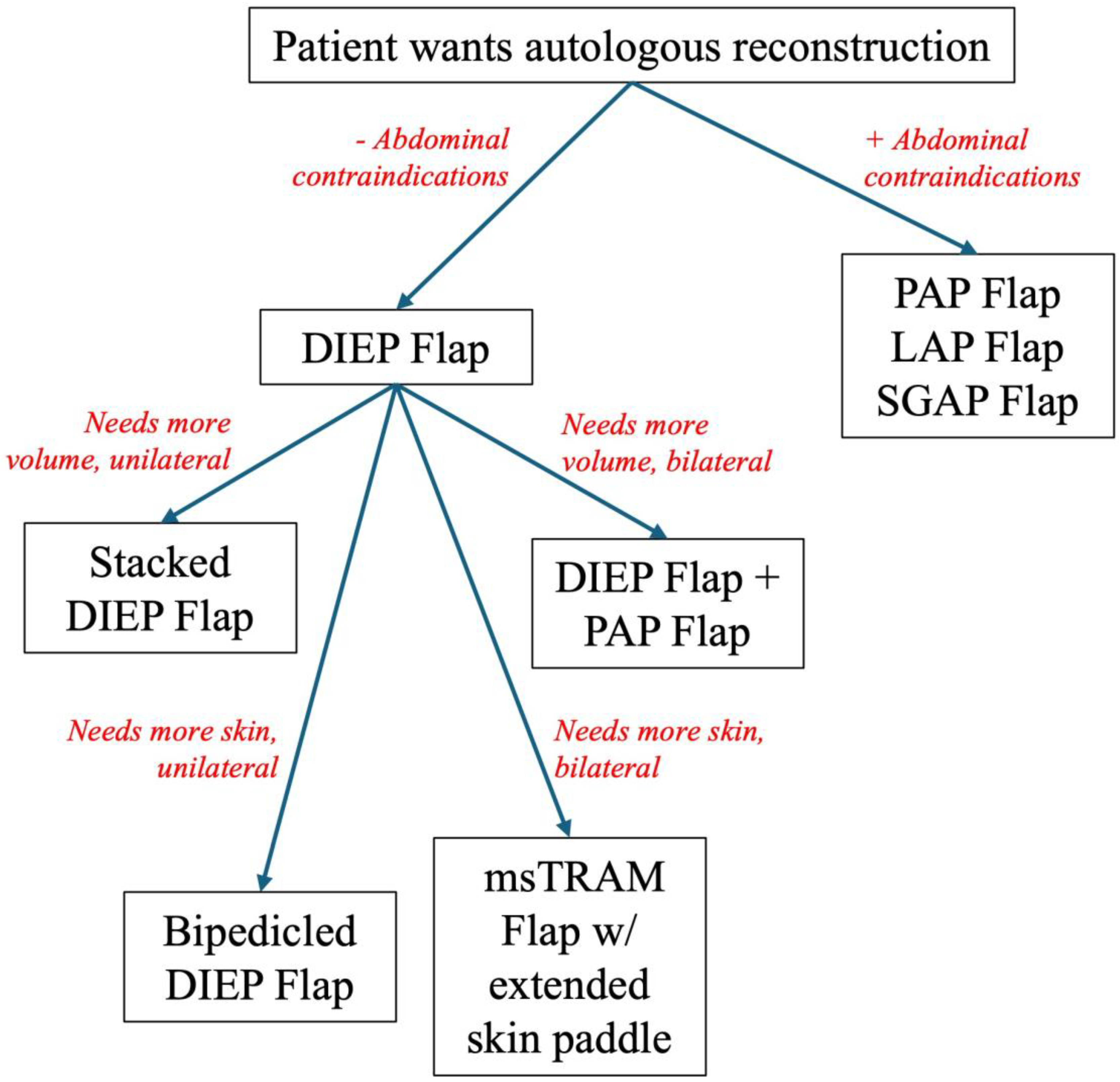

In higher-risk patients (i.e. those with prior radiation or previously failed reconstruction), traditional reconstructive paradigms often need reimagining. Abdominal-based flaps (e.g. deep inferior epigastric perforator [DIEP] flap) remain foundational, but surgeons must be prepared to employ alternative donor sites (e.g. thigh, back), utilized stacked or bipedicled flaps, or customize flap design to optimize perfusion, volume and inset into a compromised recipient site [

15] (

Figure 1).

Abdominal-Based Flaps: The Gold Standard

Even in radiated or revision breasts, the DIEP flap remains the workhorse for autologous reconstruction due to its reliable anatomy, low donor site morbidity, and favorable aesthetic contour. However, in thin patients with larger defects, volume requirements may exceed what a unilateral DIEP can offer. In these scenarios, a surgeon can consider stacked DIEP flaps (bilateral flaps used for unilateral reconstruction), which can augment volume without breast implants with lower risk of fat necrosis compared to non-stacked flaps [

16,

17,

18]. Alternatively, for patients with extensive irradiated skin or unreliably thin skin envelope, a bipedicled DIEP flap or muscle-sparing transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (MS-TRAM) flap can be especially helpful at providing more robust perfusion across a wider skin paddle with an acceptable complication profile, though we find that often sufficient skin can be obtained with a standard unipedicled DIEP alone [

19]. However, patients with midline scars, prior abdominal surgeries or inadequate tissue volume may not be ideal abdominal-based flap candidates, indicating the need for secondary donor sites.

Alternative Donor Sites

When necessary, several alternative donor sites have emerged as valuable alternatives. The profunda artery perforator (PAP) flap is a reliable option with a concealed donor site that is ideal for thin patients without adequate abdominal tissue [

20]. This tissue is particularly pliable for irradiated fields with constricted breast envelopes and can also be stacked or used bilaterally. Lumbar artery perforator (LAP) and superior gluteal artery perforator (SGAP) flaps are high density fat flaps that are less pliable but ideal for volume replacement [

21,

22]. However, these flaps demand a highly technical pedicle dissection and require a patient position change between flap harvest and inset making them generally less ideal than the PAP flap [

23]. If a smaller reconstruction is required and these options are not available, the transverse upper gracilis (TUG) or vertical upper gracilis (VUG) flaps have a reliable pedicle but much decreased volume [

24,

25]. In certain situations, these alternative donor sites can be combined with abdominal donor sites successfully if needed [

26,

27].

Modifying Flaps for Irradiated Fields

Radiated mastectomy beds present particularly hostile environments for flap integration, and there are some strategies to improve outcomes. In patients with thin mastectomy skin, we like to place deepithelialized flaps underneath the mastectomy skin flaps to reinforce and better vascularize the field. Further, some authors like to externalize a skin island to help expand the skin envelope, even in the setting of NSM [

28]. Volume overcorrection is also a useful strategy to account for flap resorption in irradiated beds, though care must be taken to prevent fat necrosis from overextending the vascular pedicle [

18]. Lastly, utilize geometric principles and inset flaps in conical shape to restore maximum projection which can be useful in contracted breast pockets [

20]. In certain circumstances with substantial contraction, we find breast capsulectomy helpful though it should only be performed judiciously if there is concern for mastectomy skin flap viability [

29]. In these severely contracted capsules, radial scoring is useful if capsulectomy is not possible.

Hybrid and Fat-Augmented Flaps

Lastly, in cases where complete autologous reconstruction is not feasible or the patient desires minimal donor site morbidity, hybrid reconstruction with flap plus implant or flap plus fat grafting may be viable options [

30]. In patients desiring breast volume without a large volume flap, implants can be used successfully under smaller autologous tissue, which provides healthy, vascularized coverage over the implant to reduce capsular contracture and overall complication risk in irradiated fields [

5,

31]. Finally, serial fat grafting with has been shown to improve contour and quality of overlying irradiated skin with patients experiencing improved skin quality and reduced capsular contracture at six months [

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, it is important to note that there is an increased rate of fat necrosis and infection in irradiated breasts as compared to non-irradiated ones [

36,

37]. There are numerous protocols, but most recommend repeated fat implantation no fewer than every 20 days until obtaining a stable result and the patient is satisfied [

36].

Intraoperative Techniques and Adjuncts

In the setting of post-radiation and revision breast reconstruction, the margin for error is slim, and novel intraoperative technologies have become critical tools for microsurgeons seeking to minimize variables. One of the most impactful advances in microsurgical decision-making is real-time perfusion imaging, particularly with indocyanine green (ICG) angiography, which has been found to reduce rates of fat necrosis, mastectomy flap necrosis, and reoperation [

38,

39]. When performing immediate reconstruction in radiated settings, we especially use this tool to assess for skin flap vascularity after mastectomy before flap inset and identify hypoperfused zones for excision [

9]. If we anticipate extensive skin flap loss due to hypoperfusion, we will inset the fully epithelialized flap with epidermis buried in anticipation of future use after the mastectomy skin demarcates and requires debridement. We do not routinely use ICG when performing delayed reconstruction in radiated or revision settings unless there is concern after managing the capsule and preparing the breast pocket for the flap. Other emerging tools include hyperspectral imaging (HSI), which is noninvasive and dye-free and provides tissue oxygenation maps, and laser-assisted fluorescence angiography (LAFA) which can provide quantitative flow metrics, though definitive data are still unsettled [

40]. We do not routinely use either of these technologies.

Flap inset in high-risk patients also requires strategic forethought. When present, skin paddle orientation should anticipate scar lines, prior incisions, and areas of skin deficiency. In thin mastectomy skin flaps, deepithelialized flap placement beneath native skin can help to provide an extra buffer of vascularized tissue and support wound healing. Importantly, in cases of previous implant-based reconstruction, excision of any residual breast capsule should be performed as necessary to ensure tension-free inset and prevent area for fluid accumulation. This also releases areas of constriction and allows the breast pocket to expand, which helps to improve final breast shape. Additionally, the use of quilting sutures to laterally control the pocket and judicious use of closed-suction drains minimize seroma formation, particularly in revision or radiated patients where tissue planes are disrupted.

Recipient Vessel Strategies in The Vessel-Depleted Chest

In microsurgical breast reconstruction, the choice of recipient vessels is pivotal in high-risk patients. Prior radiation, axillary dissection, central venous access, or failed ABR attempts may compromise first line recipient vessels and make them inaccessible. These “vessel-depleted” scenarios require flexibility, familiarity with alternative options, and creative intraoperative problem-solving.

The Internal Mammary System: First Line but Not Infallible

The internal mammary artery and vein (IMA/V) remain the preferred recipient vessels for most microsurgical breast reconstructions due to their consistent anatomy, location, and caliber [

41]. However, in irradiated or previously operated fields, these vessels are highly prone to insult or injury due to their central location in the chest and can be calcified or fibrotic, complicating the anastomosis. These valuable vessels must be handled extremely delicately as inadvertent injury may render them useless. Strategies for successfully using these vessels include performing end-to-end anastomoses, avoiding artery clamps on calcified vessels, and using a limited amount of double-armed microsutures with inside-outside directed bites which can prevent dislodgement of calcific plaques. Some even advocate for use of fibrin sealants instead of “rescue” sutures to minimize intravascular trauma [

42]. In patients with prior ABR, prior costal cartilage resection may prevent preferred access (third intercostal space) to the IMA/V for anastomosis. In these situations, before looking to alternative sites, anastomosis can be performed proximally in the second intercostal space if still available or distally using retrograde flow.

The Thoracodorsal System: Secondary but Valuable

The thoracodorsal artery and vein (TDA/V) is a valuable second choice but may be unusable in patients with prior axillary lymph node dissection, prior

latissimus dorsi (LD) muscle flap harvest, or radiation-induced scarring in the axilla [

43]. However, when viable, the TDA/V can still be a valuable option in hybrid reconstruction based around the LD muscle. Surgeons must be highly wary of fibrosis or thrombosis and should be prepared for a proximal dissection if the distal pedicle has been previously compromised. Additionally, the overall reduced pedicle length generally restricts the location of the flap tissue to a more lateral position on the chest.

Salvage Options in the Vessel-Depleted Chest

If the IMA/V or TDA/V are unusable, there are several alternatives to consider. The thoracoacromial vessels are often available in the clavipectoral triangle and can be accessed via an infraclavicular incision or through the breast pocket [

44,

45]. The serratus branch of the thoracodorsal is often unusable after prior surgeries but may be available in select cases; the downside is a short pedicle which also restricts the location of the flap tissue to a more lateral position on the chest. In situations of extreme salvage, the contralateral IMA/Vs may be a viable option [

46]. Similarly, the intercostal vessels are rarely used but can be valuable in cases of extreme salvage [

47]. For salvage venous outflow, the cephalic vein is superficial, easily accessible in the deltopectoral groove and very reliable for providing outflow in vein graft scenarios.

Vein Grafts and Arteriovenous (AV) Loops

When recipient vessels are too short, scarred, or absent, interpositional vein grafts or AV loops may be required [

48,

49]. There are numerous sources throughout the body. The saphenous vein is long, of appropriate caliber, and easily harvestable from the leg to use as an interpositional vein graft [

50]. The cephalic vein can be used as a free interpositional vein graft or turned up and used for short bridging situations (reverse flow) [

51,

52]. Lastly, in cases of extreme salvage, the saphenous vein can be used as a one-stage or two-stage AV loop with the axillary or subclavian artery/vein to allow sufficient pedicle length to tunnel into the flap site. Especially in irradiated or damaged fields, vein grafts and AV loops are associated with increased complications but can remain crucial salvage tools for capable surgeons [

53].

Intraoperative Decision-Making and Contingency Planning

In these patients, preoperative evaluation must include vessel imaging to maximize preoperative planning and minimize intraoperative surprises. Preoperative imaging (CTA or MRA) should always include recipient vessel mapping and a close working relationship with the radiologist is critical initially to obtain valuable imaging studies in the correct phase. Lastly, during these challenging cases, surgeons must be prepared to explore multiple intercostal spaces, perform extensive pedicle dissection, convert to an alternative recipient vessel plan intraoperatively, including the use of vein grafts or AV loops when pedicle reach is marginal.

Revision-Specific Strategies

Revision breast reconstruction is among the most technically and psychologically complex domains in reconstructive surgery. Patients may present requiring prior IBBR explantation, after ABR flap loss, or with capsular contracture or another unsatisfactory cosmetic outcome. These situations may also be layered atop a background of radiation, further complicating reconstruction. These cases demand a tailored, multidisciplinary approach that prioritizes safety, aesthetic restoration, and reasonable patient-centered goals.

Management of IBBR Explantation and Re-Reconstruction

A patient with IBBR requiring explantation due to seroma or implant exposure represents a high-stakes challenge as these patients frequently end up with extensive scarring and soft tissue loss from mastectomy skin flap necrosis and infection. After removing the implant, numerous strategies exist to attempt to preserve the breast pocket and reconstruction, including use of continuous pocket irrigation and intravenous (IV) antibiotics, but delayed reconstruction is often preferred, with interval healing followed by autologous reconstruction [

54,

55,

56].

In select cases with early exposure and clean wound beds, reconstruction salvage with immediate flap coverage (e.g., local flap or free flap) may be attempted, though success rates are variable [

57]. Depending on the severity, in these situations the implant can be explanted and replaced immediately or in a delayed fashion after the pocket has a chance to heal. Regardless, even superficial infections should prompt aggressive interventions, including IV antibiotics and possible washout, to minimize progression and potential reconstruction loss. Ultimately, these patients typically have a prolonged clinical course and must be counselled as such to minimize surprises and reconstruction fatigue, and those patients with periprosthetic infection have greater than 10 times odds for conversion to autologous reconstruction [

58].

Management of Unsatisfactory Cosmetic Outcomes

Capsular contracture remains one of the most frequent reasons for revision in IBBR, particularly in the setting of radiation. These scenarios require a multimodal treatment approach, including complete capsulectomy, especially in the setting of Baker grade III/IV contracture or suspected biofilm [

59]. In addition, conversion to autologous reconstruction with free tissue transfer as well as with pedicled

Latissimus dorsi flap can provide vascularized tissue to previously irradiated, fibrotic space which often results in improved outcomes and patient satisfaction though is not without risks [

58,

60,

61]. This autologous reconstruction can be combined with breast implants in certain patients for a hybrid reconstruction approach which can help to augment volume in situations where flap mass is not enough and prevent future capsular contracture and improving breast contour. Finally, biologic or bioresorbable mesh (e.g., P4HB, ADM) can be used successfully in well-vascularized beds to stabilize implant position within the neo-pocket [

62].

Staged and Delayed Approaches

In the highest-risk patients, including those with highly scarred breast pockets and/or fibrotic skin due to infection or radiation effects, a staged approach with TE can be very challenging, so we will often go straight to autologous reconstruction and use more skin from the donor. If desired, additional stages can involve fat grafting, implant placement or symmetrizing procedures for final aesthetic optimization.

Managing Expectations and Psychological Recovery

Importantly, reconstruction following radiation or prior reconstruction failure requires extensive physical and psychological stamina from the patient as they are frequently skeptical or fearful after prior (large) surgeries and complications. For optimal surgeon and patient success in these scenarios, there must be clear communication of risks and limitations of future surgeries emphasizing realistic outcomes and potential for multiple stages, and we recommend the involvement of cancer-specific psychosocial support services [

63]. Ultimately, even in the best hands no result is guaranteed, and it is important to reset expectations and shift focus from perfection to stability, safety, and improved quality of life.

Postoperative Management and Enhanced Recovery

Postoperative care plays a pivotal role in determining the long-term success of microsurgical breast reconstruction as even technically flawless reconstructions are vulnerable to failure if not supported by structured postoperative protocols. For enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), we attempt to optimize patients preoperatively as much as possible with smoking cessation, nutritional support, and medical comorbidity control as time allows. Intraoperatively, we use regional blocks as indicated to improve early ambulation and minimize the use of opioid analgesics.

Reliable flap monitoring is essential in the early postoperative period, especially in patients with irradiated or previously operated recipient beds. Strategies include traditional clinical monitoring with color, turgor, capillary refill and Doppler signal though some of these may be limited by radiation effects. Thus, additional strategies may be warranted including implanted Doppler probes or near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and surface temperature probes which are useful for continuous monitoring and earlier detection of perfusion compromise [

64,

65]. As usual, any concerns of vascular compromise warrant immediate re-exploration, as salvage rates decline rapidly with time, especially in these revision or irradiated patients.

Routine breast flap patients are frequently discharged on post-operative day (POD) two or three depending on the procedure, but these complex or revision patients are frequently kept in the hospital longer for additional monitoring. Upon discharge, clear, structured instructions are especially important in these patients, including signs of flap compromise, drain care and infection prevention, activity restrictions, and avenues for psychosocial support during the healing process. Empowering patients with education and frequent follow-up improves early detection of issues and promotes engagement in long-term care and optimal outcomes.

Outcomes

Assessing outcomes in high-risk breast reconstruction patients requires a nuanced interpretation of the available evidence. While microsurgical reconstruction offers durable, aesthetically favorable results in experienced hands, the literature reflects significant variability in complication rates, success metrics, and patient-reported outcomes in this subgroup.

Flap Survival and Complication Rates

Autologous free flap reconstruction continues to demonstrate high overall success rates (>95%) even in high-risk populations [

15]. However, radiation-associated cases have been found to have substantially increased risk of wound healing complications, higher rates of fat necrosis, and increased rates of unplanned return to the OR, particularly within the first 30 days [

4]. Recommendations generally favor autologous reconstruction in a delayed fashion after radiation therapy [

66,

67]. Revision cases, especially those involving prior implant removal, infected fields, or multiple surgeries, tend to have higher technical difficulty and ischemia times, higher use of vein grafts or salvage vessel strategies, and longer hospital stays and increased drain durations [

68,

69].

Aesthetic and Functional Outcomes

Several studies using validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as the BREAST-Q, have found higher satisfaction with autologous reconstruction, especially in irradiated patients, and substantially improved psychosocial and physical well-being scores after successful revision [

70,

71,

72]. Further, patients who undergo salvage autologous reconstruction also report quality-of-life improvements (though less than had they undergone immediate or delayed autologous reconstruction initially) highlighting the restorative potential of well-executed microsurgical revision [

57].

Evidence Gaps and Limitations

Despite a growing body of literature, evidence specific to post-radiation and revision patients remains limited as most large studies combine primary and revision cases, obscuring differential risks. Furthermore, radiation regimens are heterogeneous, making comparison difficult, and few prospective studies stratify outcomes by vessel depletion or prior surgical history. There is a need for prospective, risk-adjusted outcome registries and standardized reporting of complications, particularly in flap salvage scenarios and staged reconstructions.

Conclusions

Microsurgical breast reconstruction in the setting of prior radiation or failed reconstruction represents one of the most technically demanding challenges in modern reconstructive surgery. These high-risk patients often arrive with depleted recipient vessels, compromised skin envelopes, and a history of surgical disappointment. Yet with thoughtful patient selection and counselling, careful preoperative planning, and strategic use of novel technologies and recovery protocols, favorable outcomes with microsurgical techniques are not only possible but consistently achievable.

Author Contributions

TJS, CB participated in conceptualizing ideas, writing, and reviewing manuscript. OC, MC, NK participated in conceptualizing ideas and reviewing manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgments related to this paper to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this paper to report.

References

- Santosa KB, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Wilkins EG, Pusic AL. Long-term Patient-Reported Outcomes in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. JAMA Surg 2018, 153, 891–899. [CrossRef]

- Lee CH, Cheng MH, Wu CW, Kuo WL, Yu CC, Huang JJ. Nipple-sparing Mastectomy and Immediate Breast Reconstruction After Recurrence From Previous Breast Conservation Therapy. Ann Plast Surg 2019, 82 Suppl. S1, S95–S102. [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein RN, Nelson JA, Azoury SC, et al. Disparity Reduction in U.S. Breast Reconstruction: An Analysis from 2005 to 2017 Using 3 Nationwide Data Sets. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 154, 1065e–1075e. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiman AJ, Gabbireddy SR, Kotamarti VS, Ricci JA. A Meta-Analysis of Autologous Microsurgical Breast Reconstruction and Timing of Adjuvant Radiation Therapy. J Reconstr Microsurg 2021, 37, 336–345. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella D, Calabrese C, Orzalesi L, et al. Current trends and outcomes of breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy: results from a national multicentric registry with 1006 cases over a 6-year period. Breast Cancer 2017, 24, 451–457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran NV, Chang DW, Gupta A, Kroll SS, Robb GL. Comparison of immediate and delayed free TRAM flap breast reconstruction in patients receiving postmastectomy radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001, 108, 78–82. [CrossRef]

- Roostaeian J, Yoon AP, Ordon S, et al. Impact of Prior Tissue Expander/Implant on Postmastectomy Free Flap Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016, 137, 1083–1091. [CrossRef]

- Polanco TO, Shamsunder MG, Parikh RP, et al. Quality of Life in Breast Reconstruction Patients after Irradiation to Tissue Expander: A Propensity-Matched Preliminary Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2023, 152, 259–269. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen CL, Dayaratna N, Easwaralingam N, et al. Developing an Indocyanine Green Angiography Protocol for Predicting Flap Necrosis During Breast Reconstruction. Surg Innov 2025, 32, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Dalli J, Nguyen CL, Jindal A, et al. A feasibility study assessing quantitative indocyanine green angiographic predictors of reconstructive complications following nipple-sparing mastectomy. JPRAS Open 2024, 40, 32–47. [CrossRef]

- Tange FP, Verduijn PS, Sibinga Mulder BG, et al. Near-infrared fluorescence angiography with indocyanine green for perfusion assessment of DIEP and msTRAM flaps: A Dutch multicenter randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2023, 33, 101128. [CrossRef]

- Chow L, Dziegielewski P, Chim H. The Role of Computed Tomography Angiography in Perforator Flap Planning. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2024, 36, 525–535. [CrossRef]

- Cowan R, Mann G, Salibian AA. Ultrasound in Microsurgery: Current Applications and New Frontiers. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Matkin A, Redwood J, Webb C, Temple-Oberle C. Exploring breast surgeons' reasons for women not undergoing immediate breast reconstruction. Breast 2022, 63, 37–45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidekrueger PI, Moellhoff N, Horch RE, et al. Overall Complication Rates of DIEP Flap Breast Reconstructions in Germany-A Multi-Center Analysis Based on the DGPRÄC Prospective National Online Registry for Microsurgical Breast Reconstructions. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Boyd CJ, Sorenson TJ, Hemal K, Karp NS. Maximizing volume in autologous breast reconstruction: stacked/conjoined free flaps. Gland Surg 2023, 12, 687–695. [CrossRef]

- Haddock NT, Teotia SS. Modern Approaches to Alternative Flap-Based Breast Reconstruction: Stacked Flaps. Clin Plast Surg 2023, 50, 325–335. [CrossRef]

- Salibian AA, Bekisz JM, Frey JD, et al. Comparing outcomes between stacked/conjoined and non-stacked/conjoined abdominal microvascular unilateral breast reconstruction. Microsurgery 2021, 41, 240–249. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed Z, Ioannidi L, Ghali S, et al. A Single-center Comparison of Unipedicled and Bipedicled Diep Flap Early Outcomes in 98 Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2023, 11, e5089. [CrossRef]

- Haddock NT, Teotia SS, Farr D. Robotic Nipple Sparing Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction with Profunda Artery Perforator Flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock NT, Lakatta AC, Steppe C, Teotia SS. DIEP Flap versus PAP Flap versus LAP Flap: A Propensity-Matched Analysis of Aesthetic Outcomes, Complications, and Satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 154, 41S–51S. [CrossRef]

- Haddock NT, Teotia SS. Lumbar Artery Perforator Flap: Initial Experience with Simultaneous Bilateral Flaps for Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020, 8, e2800. [CrossRef]

- Haddock NT, Ercan A, Teotia SS. Bilateral Simultaneous Lumbar Artery Perforator Flaps in Breast Reconstruction: Perioperative Outcomes Addressing Safety and Feasibility. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024, 153, 895e–901e. [CrossRef]

- Cho MJ, Schroeder M, Flores Garcia J, Royfman A, Moreira A. The Current State of the Art in Autologous Breast Reconstruction: A Review and Modern/Future Approaches. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Trignano E, Fallico N, Dessy LA, et al. Transverse upper gracilis flap with implant in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a case report. Microsurgery 2014, 34, 149–152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele TN, Teotia SS, Haddock NT. Multi-Flap Microsurgical Autologous Breast Reconstruction. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Karir A, Stein MJ, Zhang J. The Conjoined TUGPAP Flap for Breast Reconstruction: Systematic Review and Illustrative Anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021, 9, e3512. [CrossRef]

- Andree C, Munder BI, Seidenstuecker K, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with DIEP flap after breast-conserving therapy. Med Sci Monit 2012, 18, CR716–CR720. [CrossRef]

- Dvali LT, Dagum AB, Pang CY, et al. Effect of radiation on skin expansion and skin flap viability in pigs. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 106, 624–629. [CrossRef]

- Demiri EC, Dionyssiou DD, Tsimponis A, Goula CO, Pavlidis LC, Spyropoulou GA. Outcomes of Fat-Augmented Latissimus Dorsi (FALD) Flap Versus Implant-Based Latissimus Dorsi Flap for Delayed Post-radiation Breast Reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2018, 42, 692–701. [CrossRef]

- Kim YH, Lee JS, Park J, Lee J, Park HY, Yang JD. Aesthetic outcomes and complications following post-mastectomy radiation therapy in patients undergoing immediate extended latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction and implant insertion. Gland Surg 2021, 10, 2095–2103. [CrossRef]

- Rigotti G, Marchi A, Galiè M, et al. Clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007, 119, 1409–1422. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgarello M, Visconti G, Farallo E. Autologous fat graft in radiated tissue prior to alloplastic reconstruction of the breast: report of two cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2010, 34, 5–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgarello M, Visconti G, Barone-Adesi L. Fat grafting and breast reconstruction with implant: another option for irradiated breast cancer patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012, 129, 317–329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Renom JM, Muñoz-Olmo JL, Serra-Mestre JM. Fat grafting in postmastectomy breast reconstruction with expanders and prostheses in patients who have received radiotherapy: formation of new subcutaneous tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010, 125, 12–18. [CrossRef]

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. The serial free fat transfer in irradiated prosthetic breast reconstructions. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2009, 33, 695–700. [CrossRef]

- Fodor J, Gulyás G, Polgár C, Major T, Kásler M. [Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: the issue of compatibility]. Orv Hetil 2003, 144, 549–555.

- Hembd AS, Yan J, Zhu H, Haddock NT, Teotia SS. Intraoperative Assessment of DIEP Flap Breast Reconstruction Using Indocyanine Green Angiography: Reduction of Fat Necrosis, Resection Volumes, and Postoperative Surveillance. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020, 146, 1e–10e. [CrossRef]

- Duggal CS, Madni T, Losken A. An outcome analysis of intraoperative angiography for postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthet Surg J 2014, 34, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Kleiss SF, Michi M, Schuurman SN, de Vries JPM, Werker PMN, de Jongh SJ. Tissue perfusion in DIEP flaps using Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Angiography, Hyperspectral imaging, and Thermal imaging. JPRAS Open 2024, 41, 61–74. [CrossRef]

- Nahabedian, M. The internal mammary artery and vein as recipient vessels for microvascular breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2012, 68, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaoud J, Honart JF, Bennis Y, Leymarie N. How to manage calcified vessels for head and neck microsurgical reconstruction. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020, 121, 439–441. [CrossRef]

- Lemdani MS, Crystal DT, Ewing JN, et al. Reevaluation of Recipient Vessel Selection in Breast Free Flap Reconstruction. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto T, Kageyama T, Sakai H, Fuse Y, Tsukuura R, Yamamoto N. Thoracoacromial artery and vein as main recipient vessels in deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap transfer for breast reconstruction. J Surg Oncol 2021, 123, 1232–1237. [CrossRef]

- Changchien CH, Fang CL, Hsu CH, Yang HY, Lin YL. Creating a context for recipient vessel selection in deep inferior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2023, 84, 618–625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen CK, Tai HC, Chien HF, Chen YB. Various modifications to internal mammary vessel anastomosis in breast reconstruction with deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. J Reconstr Microsurg 2010, 26, 219–223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follmar KE, Prucz RB, Manahan MA, Magarakis M, Rad AN, Rosson GD. Internal mammary intercostal perforators instead of the true internal mammary vessels as the recipient vessels for breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011, 127, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Kapila AK, Wakure A, Morgan M, Belgaumwala T, Ramakrishnan V. Characteristics and outcomes of primary interposition vascular grafts in free flap breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2020, 73, 2142–2142. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka W, Karakawa R, Yoshimatsu H, Yano T. Breast reconstruction using a superficial inferior epigastric artery flap with pedicle elongation via an arteriovenous loop: A case report. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31183. [CrossRef]

- Flores JI, Rad AN, Shridharani SM, Stapleton SM, Rosson GD. Saphenous vein grafts for perforator flap salvage in autologous breast reconstruction. Microsurgery 2009, 29, 236–239. [CrossRef]

- Chang EI, Fearmonti RM, Chang DW, Butler CE. Cephalic Vein Transposition versus Vein Grafts for Venous Outflow in Free-flap Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2014, 2, e141. [CrossRef]

- Silhol T, Suffee T, Hivelin M, Lantieri L. [Transposition of the cephalic vein in free flap breast reconstruction: Technical note]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 2018, 63, 75–80. [CrossRef]

- Langdell HC, Shammas RL, Atia A, Chang EI, Matros E, Phillips BT. Vein Grafts in Free Flap Reconstruction: Review of Indications and Institutional Pearls. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 149, 742–749. [CrossRef]

- Gowda MS, Jafferbhoy S, Marla S, Narayanan S, Soumian S. A Simple Technique Using Peri-Prosthetic Irrigation Improves Implant Salvage Rates in Immediate Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [CrossRef]

- Haque S, Kanapathy M, Bollen E, Mosahebi A, Younis I. Patient-reported outcome and cost implication of acute salvage of infected implant-based breast reconstruction with negative pressure wound therapy with Instillation (NPWTi) compared to standard care. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2021, 74, 3300–3306. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Hulsman L, Imeokparia F, et al. Implant-based Breast Reconstruction Salvage with Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with Instillation: An Evaluation of Outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2024, 12, e6116. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Glinski M, Holler N, Kümmel S, et al. Autologous Reconstruction After Failed Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Comparative Multifactorial Outcome Analysis. Ann Plast Surg 2023, 91, 42–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitoiu B, Schlagintweit S, Zhang Z, Bovill E, Isaac K, Macadam S. Conversion from Alloplastic to Autologous Breast Reconstruction: What Are the Inciting Factors? Plast Surg (Oakv) 2024, 32, 213–219. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim DS, Moon YJ, Lee HC, Chung JH, Jung SP, Yoon ES. Risk factor analysis and clinical experience of treating capsular contracture after prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction. Gland Surg 2024, 13, 987–998. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigdeli AK, Tee JW, Vollbach FH, et al. "Microsurgical breast reconstruction - A salvage option for failed implant-based breast reconstruction". Breast 2025, 82, 104480. [CrossRef]

- Holmes WJM, Quinn M, Emam AT, Ali SR, Prousskaia E, Wilson SM. Salvage of the failed implant-based breast reconstruction using the Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap: A single centre experience with tertiary breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2019, 72, 1075–1083. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karp N, Sorenson TJ, Boyd CJ, et al. The GalaFLEX "Empanada" for Direct-to-Implant Prepectoral Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2025, 155, 488e–491e. [CrossRef]

- Foppiani J, Lee TC, Alvarez AH, et al. Beyond Surgery: Psychological Well-Being's Role in Breast Reconstruction Outcomes. J Surg Res 2025, 305, 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Johnson BM, Egan KG, He J, Lai EC, Butterworth JA. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Tissue Oximetry Versus Conventional Methods for Postoperative Monitoring of Autologous Breast Reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2023, 91, 617–621. [CrossRef]

- Kumbasar DE, Hagiga A, Dawood O, Berner JE, Blackburn A. Monitoring Breast Reconstruction Flaps Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Tissue Oximetry. Plast Surg Nurs 2021, 41, 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Clemens MW, Kronowitz SJ. Current perspectives on radiation therapy in autologous and prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg 2015, 4, 222–231. [CrossRef]

- Rogers NE, Allen RJ. Radiation effects on breast reconstruction with the deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 1919–1924. [CrossRef]

- Song JH, Kim YS, Jung BK, et al. Salvage of Infected Breast Implants. Arch Plast Surg 2017, 44, 516–522. [CrossRef]

- Francis SD, Thawanyarat K, Johnstone TM, et al. How Postoperative Infection Affects Reoperations after Implant-based Breast Reconstruction: A National Claims Analysis of Abandonment of Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2023, 11, e5040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim M, Vingan P, Boe LA, et al. Satisfaction with Breasts following Autologous Reconstruction: Assessing Associated Factors and the Impact of Revisions. Plast Reconstr Surg 2025, 155, 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Zong AM, Leibl KE, Weichman KE. Effects of Elective Revision after Breast Reconstruction on Patient-Reported Outcomes. J Reconstr Microsurg 2025, 41, 100–112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi M, Sowa Y, Tsuge I, Kodama T, Inafuku N, Morimoto N. Long-Term Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life Following Breast Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 815498. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).