Introduction

Informal help from adult children is often essential to the well-being of older individuals, particularly when physical or cognitive impairments limit their ability to manage daily activities. This is evident not only in contexts with strong traditions of family-based care, but also in countries where public institutions serve as the primary providers of elder care. In both contexts, adult children and other relatives play a vital complementary role in supporting older parents (Motel-Klingebiel et al., 2005; Dykstra, 2009; Dykstra and Fokkema, 2011; Von Saenger et al., 2023).

However, reliance on family-based care presents a challenge for a significant proportion of Europe’s ageing population, as many older individuals do not have children or live without a partner (Pittavino et al., 2025). Consequently, many must manage on their own or depend on professional services, or on assistance from friends, neighbours, or the extended family. While children living far away may offer some support remotely, providing consistent, hands-on assistance with daily tasks is considerably more difficult. A previous study based on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) found that approximately 15% of older parents in Europe had no child living within 25 kilometres (Hank, 2007). In the most recent wave of SHARE (wave 9), this figure was 18.6%. Older individuals without adult children living nearby represent a potentially vulnerable group when it comes to access to informal care.

In this study, we use data from SHARE to examine the provision of informal and professional care to individuals aged 70 and above. Our focus is on older adults whose children live far away, comparing their experiences with those of parents whose children live nearby or in the same household, as well as with older people without children.

The dataset includes respondents from countries with differing welfare state arrangements, enabling comparisons between contexts where families play a central role in elder care and those where public institutions bear primary responsibility. To explore how the availability of adult children is associated with informal and professional support, we use data from the most recent SHARE wave (Wave 9). Additionally, we draw on Wave 8 and the first SHARE Corona Survey (SC1) to compare patterns of support before and during the pandemic, and to investigate whether the COVID-19 crisis altered the overall provision of support to older individuals. This study thereby contributes to existing research by using more recent data on informal care for older adults in Europe than earlier studies (e.g. Fihel et al., 2022). Furthermore, it adds to the growing body of literature on informal care during COVID-19 (e.g. Tur-Sinai et al., 2021; Bergmann & Wagner, 2021), by focusing on older parents without proximate adult children.

Background and Previous Research (3)

Nearness of Adult Children

Data from the United Nations (UN 2005; UN 2017) indicate a global trend toward a higher proportion of older individuals living alone, living independently with a spouse, and a declining share co-residing with adult children. However, these figures vary significantly: 26.5% of older adults live alone in high-income countries, compared to 9.8% in upper-middle-income countries and just 7.1% in lower-middle and low-income countries. Globally, approximately half of the population aged 60 and above live with their children, whereas in Europe this figure is only 20.6%, and in Northern Europe just 13% (UN 2017). Previous research highlights shrinking family networks and raises concerns about kinlessness and ageing alone (Carr, 2019; Verdey et al., 2019).

Studies have shown a higher tendency for adult children to remain geographically close to their parents in countries with family-based elder care models, while universal welfare states tend to facilitate geographic mobility among younger generations, often for employment or education (e.g., Borbone, 2009). Hank (2007), using SHARE data, identified substantial differences in intergenerational proximity across Europe, with less co-residence and greater distances between generations in Northern Europe compared to countries with family-oriented welfare systems. Regarding trends of intergenerational proximity, national-level studies have produced mixed findings (Kalmijn, 2021; Malmberg et al., 2025).

Intergenerational distance is primarily shaped by the mobility of the younger generation, but can also result from older adults relocating—often in mid-life or post-retirement—to attractive regions, thereby distancing themselves from their family networks (Malmberg et al., 2025). In both scenarios, migration can weaken local support systems, leaving older individuals who rely on adult children for assistance without key providers of care. Conversely, remaining in the same location may foster the development of informal support networks, where neighbours, friends, and extended family can partially compensate for the absence of adult children.

Care Provision

Previous research has consistently highlighted the central role of adult children in providing help to older individuals, even though other relatives and non-kin are also frequent sources of support (Silverstein & Bengtson, 1997; Kalwij et al., 2014; von Saenger et al., 2023). Unsurprisingly, members of proximate family networks tend to have more frequent contact and greater exchange than those in more distant networks, and proximity to adult children significantly influences the amount and type of care provided (Fors & Lennartsson, 2008; Kalmijn, 2006; Fihel et al., 2022; von Saenger, 2023). This holds true although distant children can provide some support remotely, for example through information and communication technologies (ICT) (Compton & Pollak, 2015; Peng et al., 2018). As Pihel et al. (2022) found, the share of help from non-family members increases as the distance to adult children grows.

While the literature emphasizes the importance of family in care provision, some studies have also pointed to the ambivalence inherent in family relationships. The presence or proximity of family members does not always guarantee support and may, in some cases, lead to conflict or estrangement (Silverstein & Gianrusso, 2010). Moreover, long distances between parents and adult children can sometimes reflect strained or poor family relations. Conversely, other studies have shown that increased care needs among older adults may prompt adult children to relocate closer to their parents (Artamonova et al., 2020).

Friends and neighbours also play a significant role in informal care, particularly for older individuals without children living nearby (Fihel et al., 2022). As Djundeva et al. (2019) noted, living alone does not necessarily equate to social isolation. Nevertheless, various studies on informal care and support underscore the vulnerability of older adults who are unpartnered and childless, as well as those whose children live at a considerable distance (Arpino et al., 2022; Verdey et al., 2019). Fihel et al. (2022), using data from SHARE Waves 1 and 2 (2006), found that both the likelihood and amount of family support declined with increasing intergenerational distance. They also observed that help from non-family members was more common among childless individuals than among parents with children living far away.

These findings underscore the importance of examining the circumstances of older adults without children and those with children living at a distance, while also distinguishing between these two groups. A key question in our study is whether the patterns observed in the early 2000s still hold today.

Welfare Models and Care

The consequences of lacking a dense and proximate family network vary across countries and are shaped by the relative roles of family and professional care within different welfare models. Previous research has examined intergenerational support across welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, 2013; Hank, 2007; Fokkema et al., 2008), and how these regimes influence the extent and nature of family-based care (Fors & Lennartsson, 2008; Fokkema et al., 2008; Dykstra & Fokkema, 2011). In countries with universal welfare models, professional care often substitutes for family-provided support. However, several studies have highlighted the continued importance of family as a complementary source of care, even in these contexts (Motel-Klingebiel et al., 2005; Dykstra, 2009; Dykstra & Fokkema, 2011). Moreover, recent trends suggest a re-familization of care, where families are becoming increasingly central to elder support (Szebehely & Meagher, 2018).

While some Northern and Western European countries—traditionally characterized by high coverage of professional care—are now scaling back residential and institutional services, others, such as Spain and Portugal, are expanding professional care from previously low levels to meet growing demand (Kröger, 2024). These developments underscore the diversity of care models across Europe. The Nordic countries, along with parts of Western and Central Europe, typically rely more on formal care services, contrasting with Southern and Eastern European countries where families bear a larger share of the caregiving burden. In these latter contexts, co-residence with adult children is more common, and help from individuals outside the household is less frequent.

The Pandemic

During the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic spread across Europe, initially affecting countries in Southern Europe, followed by Central and Northern Europe, and eventually more intensively in Eastern Europe. The outbreak led to a rapid decline in daily out-of-home activities due to policy-induced restrictions and widespread fear of infection. These changes had significant consequences for the provision of both personal and instrumental care and support (Fors et al., 2021; Olofsson et al., 2023; Bergmann et al., 2022; Arpino et al., 2022; Lestari et al., 2024). For many older individuals, the pandemic disrupted everyday routines such as shopping, walking, and social interaction, increasing their reliance on support from family members, neighbours, friends, public institutions, or civic organisations (Fors et al., 2021; 2024). At the same time, restrictions and concerns about contagion limited the ability of family members to provide direct care and support (Bergmann et al., 2022; Lestari et al., 2024). As a result, the pandemic posed particular challenges for older adults without children or with children living far away.

Tur-Sinai et al. (2021) found that many individuals experienced difficulties in providing home care during the pandemic but also observed an increase in informal help from children, neighbours, friends, and colleagues. Bergmann & Wagner (2021), using SHARE data from 26 European countries, reported a decline in downward intergenerational support (from parents to children), while personal care provided to parents increased during the initial phase of the pandemic. Notably, they found that approximately one-fifth of older individuals did not receive adequate care. Similarly, Lestari et al. (2024), in a study based on SHARE data, reported higher levels of instrumental support received by people aged 50 and above during the pandemic, but lower levels of support provided. Bergmann et al. (2022) confirmed these findings, noting increased support to parents but reduced support in the opposite direction. They also observed that in Western Europe, instrumental help to non-kin was relatively common during the early phase of the pandemic but declined in later stages.

This study focuses on the consequences of the pandemic for help provision to older individuals without adult children living nearby. A central question is whether the patterns of support observed before the pandemic persisted or changed in the post-pandemic period, particularly for those who may be more vulnerable due to limited access to proximate family support.

Data and Methods

This study uses data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a large cross-national survey of people aged 50 and over from 28 European countries and Israel (Börsch-Supan, 2013). This study draws on information from the regular face-to-face surveys conducted in waves 8 (2019/2020) and 9 (2021/2022), which were collected before and after the COVID-19 pandemic (SHARE-ERIC, 2024a; SHARE-ERIC, 2024b). We analyse data on the receipt of professional and informal help from individuals outside the household, as well as information on childlessness and the proximity of adult children. Sociodemographic variables are derived from the wave 8 and 9 interviews.

For information on informal help during the COVID-19 pandemic, we use data from the Wave 8 SHARE Corona Survey (SCS1) (Bergmann et al., 2024; SHARE-ERIC, 2024c). The SCS1 is a subsample of the regular SHARE panel, conducted through computer-assisted telephone interviews between June and August 2020 (Scherpenzeel et al. 2020). For the present study, the sample is restricted to community-dwelling adults aged 70 and older and includes only data from the first wave of the SHARE Corona Survey. The sample consist of 31,294 respondents of whom 57.4% are women. Specifically, 20,448 participate in wave 8 (57.6% women), 23,541 in SC1 (57.8% women), and 29,748 in wave 9 (57.1% women).

Nearness of Children

To examine the association between the availability of adult children and the receipt of informal and professional help, we construct a categorical variable distinguishing four groups of respondents: (1) no children, (2) only adult children living more than 25 km away (3) at least one adult child living within 25 km, and (4) living in the same household as an adult child. This classification is based on the SHARE wave 8 and 9 question Where does [child] live? with response categories: “In the same household” “In the same building”, “Less than 1 kilometre away”, “Between 1 and 5 kilometres away”, “Between 5 and 25 kilometre away”, “Between 25-100 kilometres away”, “Between 100 and 500 kilometres away” and “More than 500 kilometres away”. We define “having an adult child nearby” as having at least one child living within 25 km and “having adult children far away” as having only adult children living more than 25 km away. We acknowledge that this threshold may not be optimal, as some children living just beyond 25 km may still be able to provide regular or daily help.

Help Provision

For waves 8 and 9, receipt of professional help is based on the question: During the last twelve months did you receive in your own home any professional or paid services due to a physical, mental, emotional or memory problem? Respondents answer “yes” or “no” to the categories “Help with personal care”, “Help with domestic tasks”, “Meals-on-wheels” and “Help with other activities”. We create a binary variable coded 1 (received professional help) if a respondent answers “yes” to any category.

Informal, non-financial help is based on the question: “Thinking about the last twelve months, has any family member from outside the household, any friend or neighbour given you any kind of help listed on this card? Responses are coded as 1= “yes” and 0= “no”. Respondents may indicate up to three helpers and specify the types of help received. Information of help providers is based on the following question: Which family member from outside the household, friend or neighbour has helped you in the last twelve months? Responses are divided into three categories: “Own children”, “Other relatives (including partner)” and “Other non-relatives”. Types of help include personal care and practical household help (including paperwork). The first-mentioned helper by the respondents is defined as the key provider.

In the Wave 8 SHARE Corona Survey (SC1), questions on professional and informal help from the regular SHARE waves are not included. Instead, we use the following question on informal help: Since the outbreak of Corona, were you helped by others from outside of home to obtain necessities, e.g. food, medications or emergency household repairs? (yes or no).

Covariates

To analyse help provision across different welfare contexts, we classify participating countries into four regional groups reflecting differences in the role of the family in providing care to older people who are no longer able to manage on their own. These groups are:

- (a)

North (Sweden, Finland and Denmark), with the Scandinavian welfare model, where the public institutions have the main responsibility and family mainly has a complementary role for provision of care to older people,

- (b)

South (Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus), where the family has the main responsibility for care to older people,

- (c)

East (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary, Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia) that includes post-communist countries where the family is the main provider of care to older people, but with large variations between the countries, and

- (d)

West (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands) that includes Central and West European countries with rather diverse models for organising welfare and where the family hasan important complementary role to public, private and insurance-based institutions for care and support.

Additional covariates include sociodemographic variables such as sex, age (70-79, 80-89, 90+) education, partnership status, and subjective health. Education is measured according to the International Standard Classification of Education Scale (ISCED-97), ranging from 0 (none/early childhood education) to 6 (doctoral or equivalent level). In this study, education is categorised into “low” (ISCED 0, 1, 3, 4) and “high” (ISCED 5, 6). Partner is coded as 1=living with a partner 0=not living with a partner). Subjective health is coded in wave 8 and 9 as 1= less than very good and 0= very good to excellent. In SC1 the respondents were asked about their health status before the outbreak of Corona and was coded 1=Good to excellent and 0= Fair or poor.

Analytical Strategy

We first present descriptive statistics on the receipt of informal and professional help, the types of help provided and the help providers, broken down by accessibility of adult children and country groups. These descriptives provide an overview of patterns in help provision in wave 9.

We then estimate logistic regression models to examine the likelihood of receiving informal and professional help among adults aged 70 and older. From these models, we calculate predicted probabilities, adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status. Comparisons are made between older parents having their children far away, to those with children close or in the same household, and to individuals without children. Pairwise comparisons of predicted probabilities are computed to test for statistically significant differences between groups.

Since the wording of help-related questions differs between the regular SHARE waves and the SC1, results on help provision during the pandemic cannot be directly compared with those from waves 8 and 9. However, in all three survey we compare differences in the receipt of help across the four child-availability groups. All results from the regular SHARE waves and the SC1 are weighted using calibrated individual cross-sectional weights (age, gender, and NUTS1 regions) unless stated otherwise. All analyses are conducted using Stata v19 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Descriptive Findings

The overall figures from wave 9 on the presence and proximity of adult children, reveal that 70.3% of respondents, aged 70 and above live together with or close to their adult children, a physical nearness that facilitates frequent intergenerational help. However, many older people in the sample either do not have adult children (11.1%) or live far away from them (18.6%). We also found much higher proportions of older adults living together with their children in countries with a family-based welfare model: 22.8% in the South and 25.2% in the East, compared to only 3.3% in the North and 7.8% in the West. By contrast, the share of older adults living far away from their children is much higher in the North (29.3%) and the West (25.7%) than in the South (7.6%) and the East (16.2%), with an overall sample average of 18.6%. In addition, the percentage without children varies considerably, from 13.4% in the South to 7.1% in the East, while among those with children living nearby, differences between country groups are relatively small. Altogether, these findings reveal a diverse pattern of accessibility to adult children, shaping the physical opportunity structure for intergenerational relations and help across European countries.

Table 1.

Presence and proximity to adult children, by country groups. Wave 9.

Table 1.

Presence and proximity to adult children, by country groups. Wave 9.

| |

Children far away >25km |

No children |

Children close <25 km |

In same household |

| North |

29.3% |

8.3% |

59.1% |

3.3% |

| West |

25.7% |

11.8% |

54.7% |

7.8% |

| South |

7.6% |

13.4% |

56.2% |

22.8% |

| East |

16.2% |

7.1% |

51.6% |

25.2% |

| Total |

18.6% |

11.1% |

54.8%% |

15.5% |

The percentage of the overall sample aged 70 and above who received help from outside the household was 29.6% in wave 9 of SHARE, (see

Table 2). Many older people in Europe are clearly dependent on help from persons outside the household, but a majority seem to manage on their own or with support from household members, such as a co-residing children or a partner. However, the data do not reveal how many are in fact in need of care and must struggle on their own, for example due to the absence of a proximate family network.

Furthermore, we found that 27,3% of those without children received informal help from outside the household, and the figures for parents with children living far away were very similar (26,6%) (

Table 2). Expectedly, the percentage of older people receiving help from people outside the household was higher for parents with children living close (34.5%), and lower for those living in the same household as an adult child (19.4%).

Similar figures on receiving professional help (

Table 2) show the highest percentage among those without children (21.4%), followed by parents with children living nearby (20.0%) and those with children living far away (18.0%). As expected, professional help for older people living with children in the same household is less common (11.9%). The figures for receiving both professional and informal help from outside the household were somewhat higher in wave 9 than in wave 8. However, this difference was not observed in the predicted probabilities, where we controlled for age and various other covariates (see below).

Figures on help providers (

Table 3) highlight the importance of adult children for the provision of help from outside the household. We found that two-thirds of the parents with children living close have an adult child as their key provider, compared to only about one-third of parents whose children live far away (

Table 3). In the latter group, key providers were mainly among non-relatives (48.2%). Similarly, among people without children, non-relatives were the main providers for many (55.6%). Obviously, friends and neighbours play a key role in supporting those who do not have adult children or whose children live far away. In line with previous findings (Fihel et al 2022), we noted a much higher percentage among people without children (44.4%) who reported other relatives as their key provider. This suggests that siblings, nieces and other relatives play an important role for older people who do not have children, but a much smaller role for those whose children live far away (17.4%).

In figures on key providers, we did not find any major differences across country groups (

Table 4). To some extent, however, the figures reflect the role of families in countries with different welfare models. We found the highest percentages of help from non-relatives in the West (33.5%) and the North (29.0%), and the lowest in the East (18.6%) and the South (19.8%). Conversely, the highest percentage of help from a child was observed in the South (64.6%) and the lowest in the West (47.9%), where support from non-relatives plays a more important role than in other country groups.

When examining differences by kind of help, we found that only 18.9 % of the overall sample in wave 9 received personal care, with the lowest percentage among parents whose children live far away (10.9%) and highest among those with children in the same household (32.3%) (

Table 5). At the same time, almost all respondents who received help also (or only) received domestic help (98.0%). The figures show that distance matters for the provision of more intimate personal help.

Logistic Regressions

In the logistic regression analyses based on SHARE Wave 8 and Wave 9 data, we found a significantly higher likelihood of receiving informal help among women, older individuals, those without a partner, and respondents reporting less than very good health. Additionally, the probability of receiving informal help from someone outside the household was lower in Southern and Eastern European countries compared to Northern Europe. For Wave 8, no significant differences were observed for Western European countries (see

Table A1).

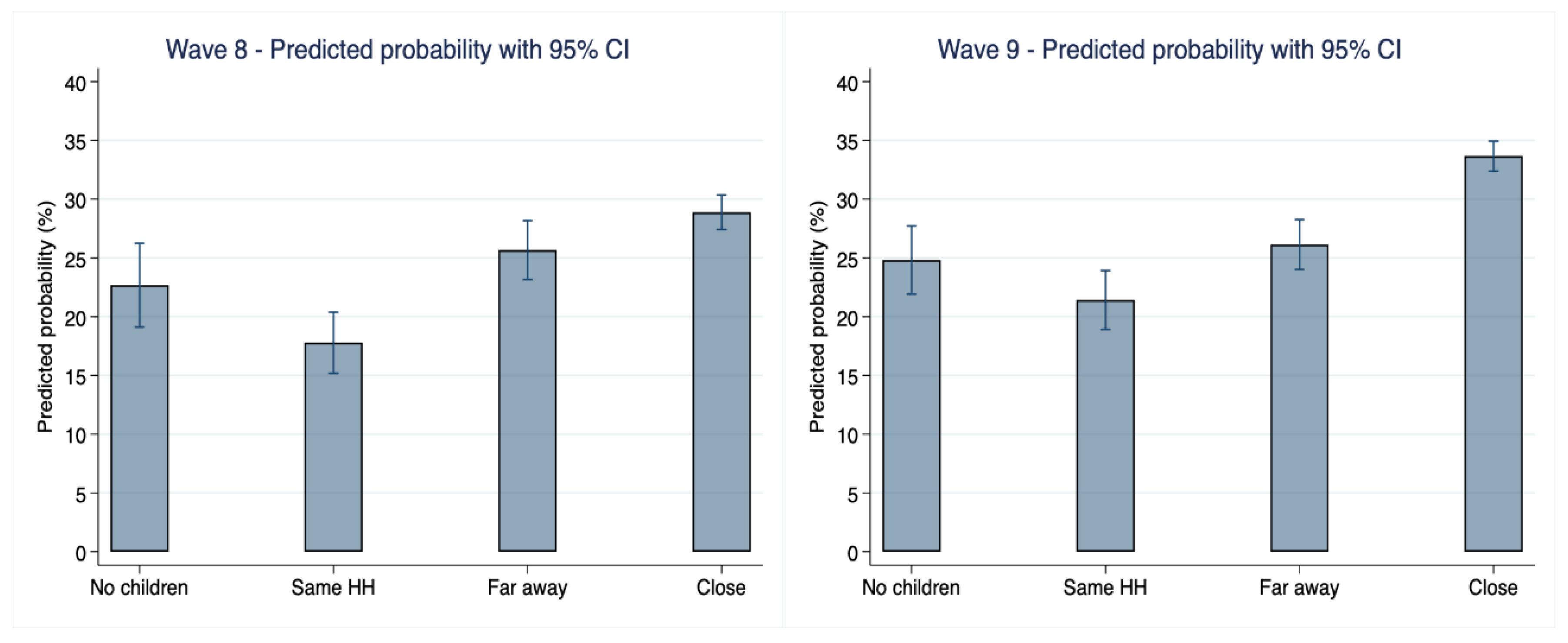

When comparing groups based on the availability of children, we used “children living close” as the reference category. In Wave 9, we found significant negative associations between receiving informal help from outside the household and having children living far away (−0.399), having no children (−0.475), and living with children in the same household (−0.684). Predicted probabilities, illustrated in

Figure 1, confirm these findings. The highest probability of receiving informal help was observed among parents with children living nearby, followed by those with children living far away, then those without children, and the lowest probability was found among those co-residing with adult children.

To further examine the differences between these groups, we conducted pairwise comparisons (

Table 6). The results showed a significantly higher probability of receiving informal help for parents with children living close compared to all other groups: those with children living far away, those co-residing with children, and those without children. We also found a significantly higher probability for the group with children living far away compared to those living in the same household. However, the differences between the group without children and the groups with children far away or co-residing were not statistically significant.

When comparing regression results and predicted probabilities between Wave 8 and Wave 9, we observed only minor differences in the associations between receiving informal help and the independent variables. Notably, in Wave 8, the difference between individuals with children living far away and those without children was not statistically significant. Taken together, these findings suggest that the overall patterns of informal help provision remained relatively stable before and after the pandemic, with only marginal changes observed.

When analysing the probability of receiving professional help (see

Table A2), we observed some differences compared to the patterns found for informal help. As with informal support, women, older individuals, those without a partner, and those reporting less than good health were more likely to receive professional assistance. However, in contrast to informal help, older adults with higher education were significantly more likely to receive professional help in Wave 9, a pattern not observed in Wave 8. Compared to Northern Europe, the likelihood of receiving professional help was lower in Eastern Europe but higher in Western Europe, while no significant difference was found for Southern Europe.

When comparing groups based on child availability, the results were somewhat contradictory. In Wave 8, older parents co-residing with adult children were least likely to receive professional help from outside the household, but no significant differences were found between those without children, those with children living far away, and those with children living nearby. In Wave 9, however, we found a significantly lower probability of receiving professional help among those without children and those with children living far away, compared to parents with children living close.

We also examined the likelihood of receiving help from outside the household for tasks such as obtaining food, medications, or emergency household repairs since the outbreak of COVID-19 (see

Table A3). As in previous analyses, women, older individuals, those without a partner, and those in poorer health were more likely to receive such support. Regarding country groups we find that older adults in Southern Europe were significantly less likely to receive informal help from outside the household compared to those in Northern Europe, while no significant differences were observed between Western and Eastern Europe relative to the North.

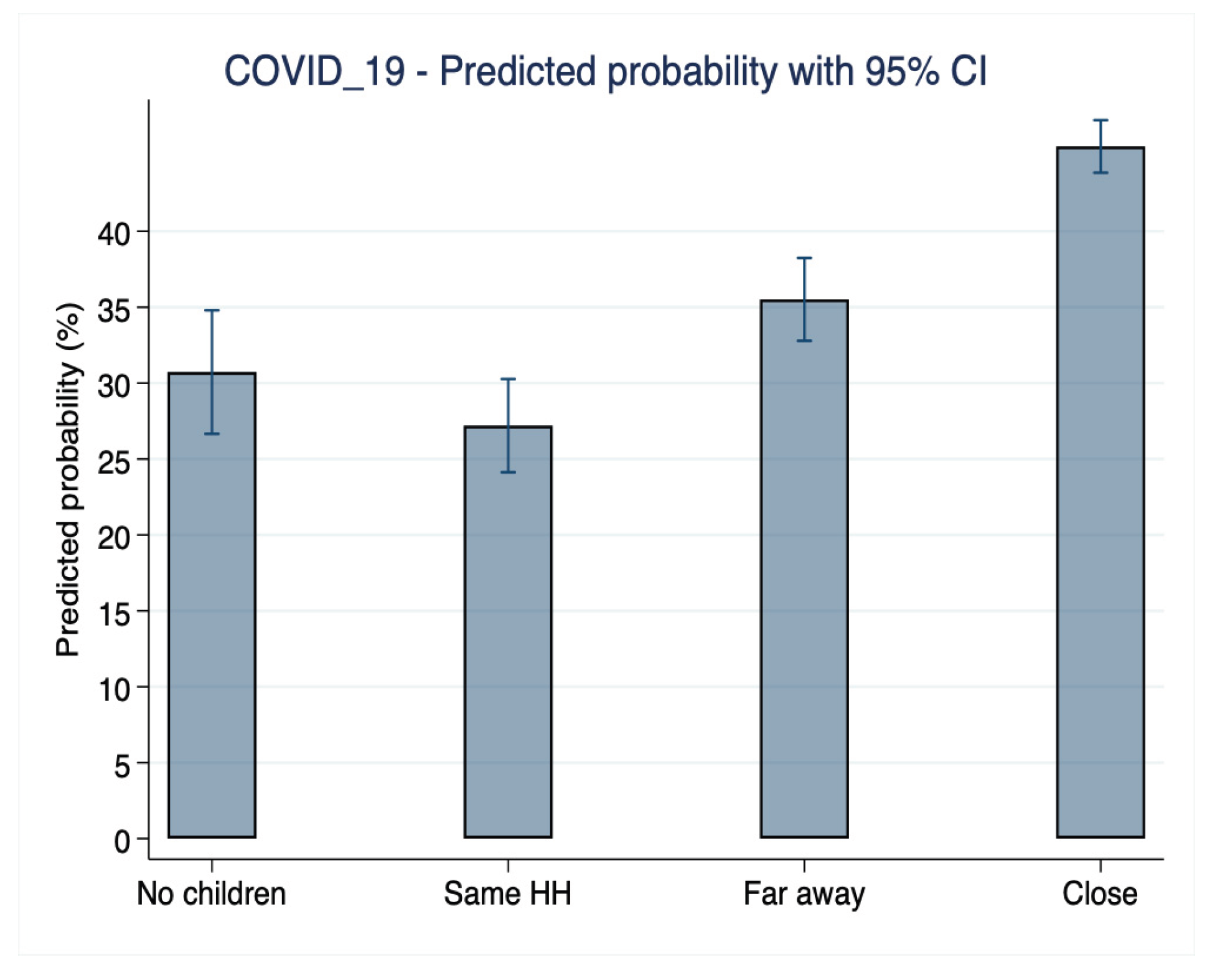

Predicted probabilities (

Figure 2) further illustrate these findings. As expected, older individuals with children living nearby had a significantly higher probability of receiving informal help during the pandemic compared to other groups. However, the difference between parents with children living far away and individuals without children was not statistically significant.

Overall, our comparison of informal help provision before, during, and after the pandemic reveals only minor differences. The results suggest that the dramatic experience of the COVID-19 pandemic did not substantially alter the well-established patterns of informal support to older adults. This may seem surprising, given the substantial increase in informal help from individuals outside the household during the pandemic. However, it is important to note that the survey item measuring “informal help” during the pandemic was based on a slightly different question, which may partly explain the observed increase.

In summary, our findings align with previous research in showing that older individuals in Europe without children, as well as those with adult children living far away, are less likely to receive both informal and professional help from outside the household compared to older parents with children living nearby. This is expected, given that adult children are key providers of informal support and proximity facilitates care. Importantly, our results underscore that not only childless older adults, but also those with distant children, constitute vulnerable groups in terms of access to care and support.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we used data from the most recent waves of SHARE, covering 26 European countries, to examine the provision of help to individuals aged 70 and above. Consistent with findings from earlier SHARE waves (e.g., Hank, 2007; Fihel et al., 2022), we found that adult children continue to play a central role in supporting older parents. This presents a challenge for the growing number of older individuals who either do not have children or whose children live far away. Our results also reveal substantial variation across country groups in the proportion of parents with children living at a distance. A key aim of this study was to investigate how help is provided to older adults without proximate children, and we emphasize the importance of distinguishing between those without children and those with children living far away.

The absence of adult children may pose a more serious problem in countries where public care provision is limited. Conversely, the proportion of older adults with children living far away is notably higher in countries with more developed public and private care systems. Clearly, the consequences of lacking nearby family depend on how welfare is organized and how care models evolve—whether toward de-familization or re-familization—and whether dependency on adult children increases. Recognizing the situation of older adults without children or with distant children is therefore crucial in policy discussions on elder care.

Proximity between older parents and adult children is shaped by migration patterns—both among younger generations moving for work or education, and older generations relocating post-retirement. Migration trends will inevitably influence the availability of informal support, and a key question for future research is whether these trends are leading to convergence or divergence in intergenerational distances across Europe, and how this affects care provision.

Our analysis focused on the extent and sources of informal help received by older adults from outside the household. As expected, the likelihood of receiving such help was lower among those co-residing with adult children and in countries with family-based welfare models. We conclude that intra-household family support remains essential in Southern and Eastern Europe, while in Northern and Western Europe, families play a vital role in providing informal help from outside the household - a role that may be challenged by increasing intergenerational distances.

While older parents with children living nearby were most likely to receive informal help, we were struck by the finding that older individuals without children received help at nearly the same rate as those with children living far away. One possible explanation is that childless older adults may have long-established informal networks of neighbours, friends and other relatives while those with distant children may be perceived as having family support, even if it is not readily available. This is supported by data showing a higher proportion of help from other relatives among childless individuals compared to those with children living far away. Additionally, older adults without children were less likely to co-reside with a partner, increasing their need for external support. This highlights the importance of further research into the role of partners in care provision, in relation to support from children.

We also compared findings from three cross-sectional surveys—SHARE Wave 8, the SHARE Corona Survey, and Wave 9. Our analyses revealed only minor differences in the association between access to adult children and the likelihood of receiving informal or professional help before and after the pandemic. This suggests that, despite the dramatic circumstances of the pandemic and the emergence of new support mechanisms, the long-term impact on informal help provision was limited, and patterns largely returned to pre-pandemic status quo.

However, we acknowledge limitations in our analysis, particularly the lack of consideration for the spread of the pandemic and the stringency of country-specific restrictions. Our findings are based solely on data from the first wave of the pandemic. Future research could benefit from incorporating data from the second SHARE Corona Survey and examining the impact of restriction severity on help provision.

Further research should also explore the amount of help received, the contribution of multiple providers, and the combined effect of professional and informal support. Investigating differences across countries, genders, urban versus rural settings, and socioeconomic groups would enrich the understanding of help provision and offer sensitivity tests for varying intergenerational distances. While this study relied on cross-sectional data, future research could adopt longitudinal methods to better assess the long-term consequences of the pandemic on support for older adults without proximate children.

To conclude, we emphasize the challenges faced by older individuals without adult children living nearby. While many older adults manage independently, those in need of care and support may find themselves struggling due to limited access to both informal and professional help. Recognizing and addressing the needs of these vulnerable groups is essential for developing inclusive and responsive elder care policies across Europe.

Acknowledgements

Research in this article is part of the project “Nearness of family – geographic proximity and care of older people in Sweden and Europe”, funded by the Swedish Research Council (Dnr 2020-02542). The research received ethical approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority No. 2021-01221.

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 8 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w8.800, 10.6103/SHARE.w8ca.800), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details.

The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission, DG RTD through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982, DASISH: GA N°283646) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SHARE-COHESION: GA N°870628, SERISS: GA N°654221, SSHOC: GA N°823782, SHARE-COVID19: GA N°101015924) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion through VS 2015/0195, VS 2016/0135, VS 2018/0285, VS 2019/0332, and VS 2020/0313. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C, RAG052527A) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see

www.share-project.org).

Appendix

Table A1.

Logistic regressions. Receiving informal help, wave 8 and 9.

Table A1.

Logistic regressions. Receiving informal help, wave 8 and 9.

| |

Wave 8 |

Wave 9 |

| Sex (ref.= Male) |

|

|

| Female |

0.259*** |

0.270*** |

| |

|

|

| Age group (ref.= 70-79 yrs) |

|

|

| 80-89 yrs |

0.632*** |

0.560*** |

| 90+ yrs |

1.157*** |

1.015*** |

| |

|

|

| Education level (ref.= Low educated) |

|

|

| Highly educated |

-0.082 |

-0.006 |

| |

|

|

| Welfare system (ref. = North) |

|

|

| West |

-0.073 |

-0.154** |

| South |

-0.998*** |

-0.911*** |

| East |

-0.386*** |

-0.558*** |

| |

|

|

| Subjective health (ref.= Very good to excellent) |

|

|

| Less than very good |

0.478*** |

0.626*** |

| |

|

|

| Partnership status (ref.= No partner) |

|

|

| Partner in HH |

-0.848*** |

-0.756*** |

| |

|

|

| Child accessibility (ref.= Child close) |

|

|

| No children |

-0.362*** |

-0.475*** |

| In same HH |

-0.696*** |

-0.684*** |

| Children far away |

-0.182** |

-0.399*** |

| |

|

|

| Constant |

-0.984*** |

-0.952*** |

| N |

15,414 |

23,326 |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood |

-20654838 |

-27106508 |

| Pseudo R2 |

0.0978 |

0.0904 |

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 |

|

|

Table A2.

Logistic regressions. Receiving professional help, wave 8 and 9.

Table A2.

Logistic regressions. Receiving professional help, wave 8 and 9.

| |

Wave 8 |

Wave 9 |

| Sex (ref.= Male) |

|

|

| Female |

0.514*** |

0.322*** |

| |

|

|

| Age group (ref.= 70-79 yrs) |

|

|

| 80-89 yrs |

0.792*** |

0.910*** |

| 90+ yrs |

2.138*** |

2.017*** |

| |

|

|

| Education level (ref.= Low educated) |

|

|

| Highly educated |

0.159 |

0.242*** |

| |

|

|

| Welfare system (ref. = North) |

|

|

| West |

0.443*** |

0.335*** |

| South |

-0.004 |

-0.053 |

| East |

-0.936*** |

-1.086*** |

| |

|

|

| Subjective health (ref.= Very good to excellent) |

|

|

| Less than very good |

0.941*** |

0.897*** |

| |

|

|

| Partnership status (ref.= No partner) |

|

|

| Partner in HH |

-0.524*** |

-0.517*** |

| |

|

|

| Child accessibility (ref.= Child close) |

|

|

| No children |

0.130 |

-0.451*** |

| In same HH |

-0.584*** |

-0.074 |

| Children far away |

-0.123 |

-2.913*** |

| |

|

|

| Constant |

-3.270*** |

|

| N |

15,311 |

23,060 |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood |

-13748246 |

-19872336 |

| Pseudo R2 |

0.129 |

0.128 |

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 |

|

|

Table A3.

Logistic regressions. Receiving informal help during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table A3.

Logistic regressions. Receiving informal help during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| |

COVID-19 |

| Sex (ref.= Male) |

|

| Female |

0.635*** |

| |

|

| Age group (ref.= 70-79 yrs) |

|

| 80-89 yrs |

0.660*** |

| 90+ yrs |

1.384*** |

| |

|

| Education level (ref.= Low educated) |

|

| Highly educated |

-0.142* |

| |

|

| Welfare system (ref. = North) |

|

| West |

0.031 |

| South |

-0.443*** |

| East |

-0.110 |

| |

|

| Subjective health (ref.= Very good to excellent) |

|

| Good to excellent |

-0.611*** |

| |

|

| Partnership status (ref.= No partner) |

|

| Partner in HH |

-0.316*** |

| |

|

| Child accessibility (ref.= Child close) |

|

| No children |

-0.712*** |

| In same HH |

-0.903*** |

| Children far away |

-0.471*** |

| |

|

| Constant |

-0.156 |

| N |

13,761 |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood |

-30224351 |

| Pseudo R2 |

0.102 |

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 |

|

References

- Arpino, B., Mair, C.A., Quashie, N.T. et al. (2022) Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—are unpartnered and childless older adults at higher risk? European Journal of Ageing 19, 1327–1338. [CrossRef]

- Artamonova, A. Gillespie, B.J., and Brandén, M. (2020) Geographic mobility among older people and their adult children: The role of parents’ health issues and family ties. Population, Space and Place. 2020; 26(8):e2371. [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, V.L. (2001) Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family 63(1): 1-16.

- Bergmann, M., & Wagner, M. (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on informal caregiving and care receiving across Europe during the first phase of the pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 673874.

- Bergmann, M., Hecher, M. V., & Sommer, E. (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the provision of instrumental help by older people across Europe. Frontiers in Sociology, 7, 1007107.

- Bergmann, M.M. Wagner, Y. Yilmaz, K. Axt, J. Kronschnabl, Y. Pettinicchi, D. Schmidutz, K. Schuller, S. Stuck and A. Börsch-Supan (2024) SHARE Corona Surveys: study profile. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies: 15 (4), pp. 506-525. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [CrossRef]

- Borbone V. (2009) Contact and Proximity of Older People to their Adult Children: A comparison between Italy and Sweden. Population Space and Place, 15, 359 -380. [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A., M. Brandt, C. Hunkler, T. Kneip, J. Korbmacher, F. Malter, B. Schaan, S. Stuck and S. Zuber (2013) Data Resource Profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology. [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A. (2020). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release version: 0.0.1. beta. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. (2019) ‘Aging Alone? International Perspectives on Social Integration and Isolation’, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(8), pp. 1391–1393. [CrossRef]

- Compton, J., & Pollak, R. A. (2015) Proximity and Co-residence of Adult Children and their Parents in the United States: Descriptions and Correlates. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 117/118, 91–114.

- Djundeva, M. , Dykstra P. A. and Fokkema T. (2019) Is living Alone”Ageing Alone”? Solitary Living, Network Types, and Well-Being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 2019, 74, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dykstra, P. A. (2009) Older adult loneliness: myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing, 6(2): 91-100.

- Dykstra, P. and Fokkema, T. (2011) Relationships between parents and their adult children: A West European typology of late-life families. Ageing and Society 31(4): 545‒569. [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2013) The Three worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Polity Press. Cambridge.

- Fihel, A. , Kalbarczyk, M., & Nicińska, A. Childlessness, geographical proximity and non-family support in 12 European countries. Ageing & Society, 2022, 42, 2695–2720. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., & Birditt, K. S. (2020) Mothers, Fathers, Daughters, and Sons: Gender Differences in Adults’ Intergenerational Ties. Journal of Family Issues, 41(9), 1597-1625. [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, T., Ter Bekke, S., and Dykstra, P.A. (2008) Solidarity between Parents and their Adult Children in Europe. Amsterdam University Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp66q.

- Fors, S. , & Lennartsson, C. Social Mobility, Geographical Proximity and Intergenerational Family Contact in Sweden. Ageing & society, 2008, 28, 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fors Connolly, F., Olofsson, J., Malmberg, G., & Stattin, M. (2021) Adjustment of daily activities to restrictions and reported spread of the COVID-19 pandemic across Europe. SHARE Working Paper Series 62-2021.

- Fors Connolly, F., Olofsson, J., & Josefsson, M. (2024) Do reductions of daily activities mediate the relationship between COVID-19 restrictions and mental ill-health among older persons in Europe? Aging & Mental Health, 28(7), 1058–1065. [CrossRef]

- Hank, K. (2007) Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family 69(1): 157‒173. [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M., (2006) Educational Inequality and Family Relationships: Influences on Contact and Proximity, European Sociological Review, Volume 22, Issue 1, February 2006, Pages 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M. (2021) Long-term trends in intergenerational proximity: Evidence from a grandchild design. Population, Space and Place, 27(8), e2473. [CrossRef]

- Kalwij, A., Pasini, G. & Wu, M. (2014) Home care for the elderly: the role of relatives, friends and neighbors. Rev Econ Household 12, 379–404. [CrossRef]

- Kröger, T. (2024). Towards the caring or the uncaring state? : A social policy perspective on longterm care trends. In K. Leichsenring, & A. Sidorenko (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Ageing and Social Policy (pp. 203-218). Edward Elgar. [CrossRef]

- Lestari, S.K., Eriksson, M., de Luna, X. Malmberg, G., & Ng, N. (2024) Volunteering and instrumental support during the first phase of the pandemic in Europe: the significance of COVID-19 exposure and stringent country’s COVID-19 policy. BMC Public Health 24, 99. [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, G. , Lundholm, E. & Olofsson, J. (2025) Nearness of Adult Children: Long-term Trends and Sociodemographic Patterns in Sweden. International Journal of Population Ageing ( 2025. [CrossRef]

- Margolis, R., & Verdery, M., (2017) Older Adults Without Close Kin in the United States, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 72, Issue 4, July 2017, Pages 688–693. [CrossRef]

- Mendolia, S., O. Stavrunova and O. Yerokhin (2020) Determinants of the Community Mobility during the COVID-19 Epidemic: The Role of Government Regulations and Information. IZA Discussion Paper Series no. 13778, IZA-Institute of Labour Economics, Bonn.

- Motel-Klingebiel, A., Tesch-Roemer, C., and Von Kondratowitz, H. (2005) Welfare states do not crowd out the family: Evidence for mixed responsibility from comparative analyses. Ageing and Society 25(6): 863-882. [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J., Fors Connolly, F., Malmberg, G., Josefsson, M., & Stattin, M. (2023) Sociodemographic Factors and Adjustment of Daily Activities During the COVID-19 Pandemic – Findings from the SHARE Corona Survey. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 36(6), 1544–1566. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. , Silverstein, M., Suitor, J. J., Gilligan, M., Hwang, W., Nam, S., & Routh, B. (2018) "Nine: Use of communication technology to maintain intergenerational contact: toward an understanding of ‘digital solidarity’". In Connecting Families?. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [CrossRef]

- Pittavino, M., Bruno Arpino, Elena Pirani, (2025) Kinlessness at Older Ages: Prevalence and Heterogeneity in 27 Countries, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Volume 80, Issue 1, January 2025, gbae180. [CrossRef]

- von Saenger, I., Dahlberg, L., Augustsson, E., Fritzell, J., & Lennartsson, C. (2023) Will your child take care of you in your old age? Unequal caregiving received by older parents from adult children in Sweden. European Journal of Ageing, 20(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Scherpenzeel, A. , Axt, K., Bergmann, M., Douhou, S., Oepen, A., Sand, G.,... & Börsch-Supan, A. (2020) Collecting survey data among the 50+ population during the COVID-19 outbreak: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). In Survey Research Methods (Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 217-221).

- SHARE-ERIC (2024a) Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC (2024b) Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 9. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- SHARE-ERIC (2024c) Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release version: 9.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M., & Bengtson, V. L. (1997) Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child-parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 429-460. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M. and Giarrusso, R. (2010. Aging and Family Life: A Decade Review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72: 1039-1058. [CrossRef]

- Szebehely, M., and Meagher, G. (2018) Nordic eldercare – Weak universalism becoming weaker? Journal of European Social Policy, 28(3), 294 - 308. [CrossRef]

- Tur-Sinai, A. , Bentur, N., Fabbietti, P., & Lamura, G. Impact of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic on formal and informal care of community-dwelling older adults: Cross-national clustering of empirical evidence from 23 countries. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 7277. [Google Scholar]

- UN (2017) United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Living Arrangements of Older Persons: A Report on an Expanded International Dataset (ST/ESA/SER.A/407).

- UN (2005) United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Living Arrangements of Older Persons Around the World. New York: United Nations. Sales No. E.05.XIII.9.

- Verdery, A. M. Margolis, R., Zhou, Z., Chai, X., and Rittirong J. (2019) ‘Kinlessness Around the World’, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. Edited by J. Raymo, 74(8), pp. 1394–1405. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities to receive informal help from outside the household wave 8 and 9. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities to receive informal help from outside the household wave 8 and 9. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities to receive informal help from others outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities to receive informal help from others outside the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

Table 2.

Percentage of persons over age 70 who received informal and professional informal help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

Table 2.

Percentage of persons over age 70 who received informal and professional informal help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

| |

Informal help |

Professional help |

| No children |

27.3% |

21.4% |

| Children far away |

26.6% |

18.0% |

| Children close |

34.5% |

20.0% |

| In same household |

19.4% |

11.9% |

| Total |

29.6% |

18.3% |

Table 3.

Key providers of informal help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

Table 3.

Key providers of informal help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

| |

Own child |

Other relatives |

Others |

| No children |

- |

44.4% |

55.6% |

| Children far away |

34.3% |

17.4% |

48.2% |

| Children close |

67.7% |

14.8% |

17.5% |

| In same household |

68.9% |

15.1% |

16.1% |

| Total |

55.4% |

18.3% |

26.3% |

Table 4.

Key providers of informal help percentage of own children, other relatives and others by country group. SHARE wave 9.

Table 4.

Key providers of informal help percentage of own children, other relatives and others by country group. SHARE wave 9.

| |

Own child |

Other relatives |

Others |

| North |

51.1% |

19.9% |

29.0% |

| West |

47.9% |

18.6% |

33.5% |

| South |

64.6% |

15.5% |

19.8% |

| East |

62.5% |

18.9% |

18.6% |

| Total |

55.4% |

18.3% |

26.3% |

Table 5.

Percentage of persons over age 70 who received personal and domestic help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

Table 5.

Percentage of persons over age 70 who received personal and domestic help from someone outside the household, by availability of adult children, no children, children far away, children close and children in the same household. SHARE wave 9.

| |

Personal help |

Domestic help |

| No children |

18.3% |

98.4% |

| Children far away |

10.9% |

98.1% |

| Children close |

19.2% |

98.0% |

| In same household |

32.3% |

97.6% |

| Total |

18.9% |

98.0% |

Table 6.

Pairwise comparisons wave 8 and 9. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

Table 6.

Pairwise comparisons wave 8 and 9. Adjusted for sex, age, country group, education level, subjective health, and partnership status.

| |

Wave 8 |

Wave 9 |

| |

Contrast |

95% CI |

Contrast |

95% CI |

| Same HH vs no children |

-.0490005 |

-.0934215 |

-.0045795 |

-.0340006 |

-.0726524 |

.0046512 |

| Far away vs no children |

.0297757 |

-.014008 |

.0735594 |

.0131397 |

-.0230331 |

.0493126 |

| Close vs no children |

.0620167 |

.0229719 |

.1010615 |

.0883937 |

.056336 |

.1204514 |

| Far away vs same HH |

.0787762 |

.0422 |

.1153524 |

.0471403 |

.013963 |

.0803177 |

| Close vs same HH |

.1110172 |

.0810804 |

.1409541 |

.1223943 |

.0943761 |

.1504125 |

| Close vs far away |

.0322411 |

.0036949 |

.0607872 |

.075254 |

.050681 |

.0998269 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).