Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cancer: A Growing Global Burden and Therapeutic Challenge

- FDA (2000–2016): Among 90 approved cancer drugs, the median overall survival (OS) benefit was only 2.4 months, with most approvals based on tumor shrinkage—not life extension [4].

- UK Cancer Drugs Fund: Despite £1.3 billion in expenditures, most drugs showed no meaningful benefit in survival or quality of life [5].

- China (2005–2020): Among 68 approved drugs, 50% showed no survival benefit, and the rest extended life by only ~4 months, often with high toxicity [6].

- Nature (2017): Review of 277 global oncology trials found that 85% of drugs had no clinical benefit; the most expensive drugs often performed worst [7].

- Australia–US (2004): Cytotoxic chemotherapy contributed only ~2% to 5-year survival in adult solid tumors [8].

- Lancet Oncology (2024): Of 223 FDA approvals based on immature survival data, only 32% showed statistically significant OS benefit upon follow-up [9].

- Global Meta-Analysis (2023): Across nearly 400 approved drugs, only ~1/3 improved survival, while ~2/3 showed no meaningful benefit [10].

- Pooled RCTs (2023): Median OS benefit from 234 modern trials was just 2.8 months, reinforcing earlier findings [11].

1.2. The Hallmarks of Cancer: Describing What Cancer Does, Not How It Begins

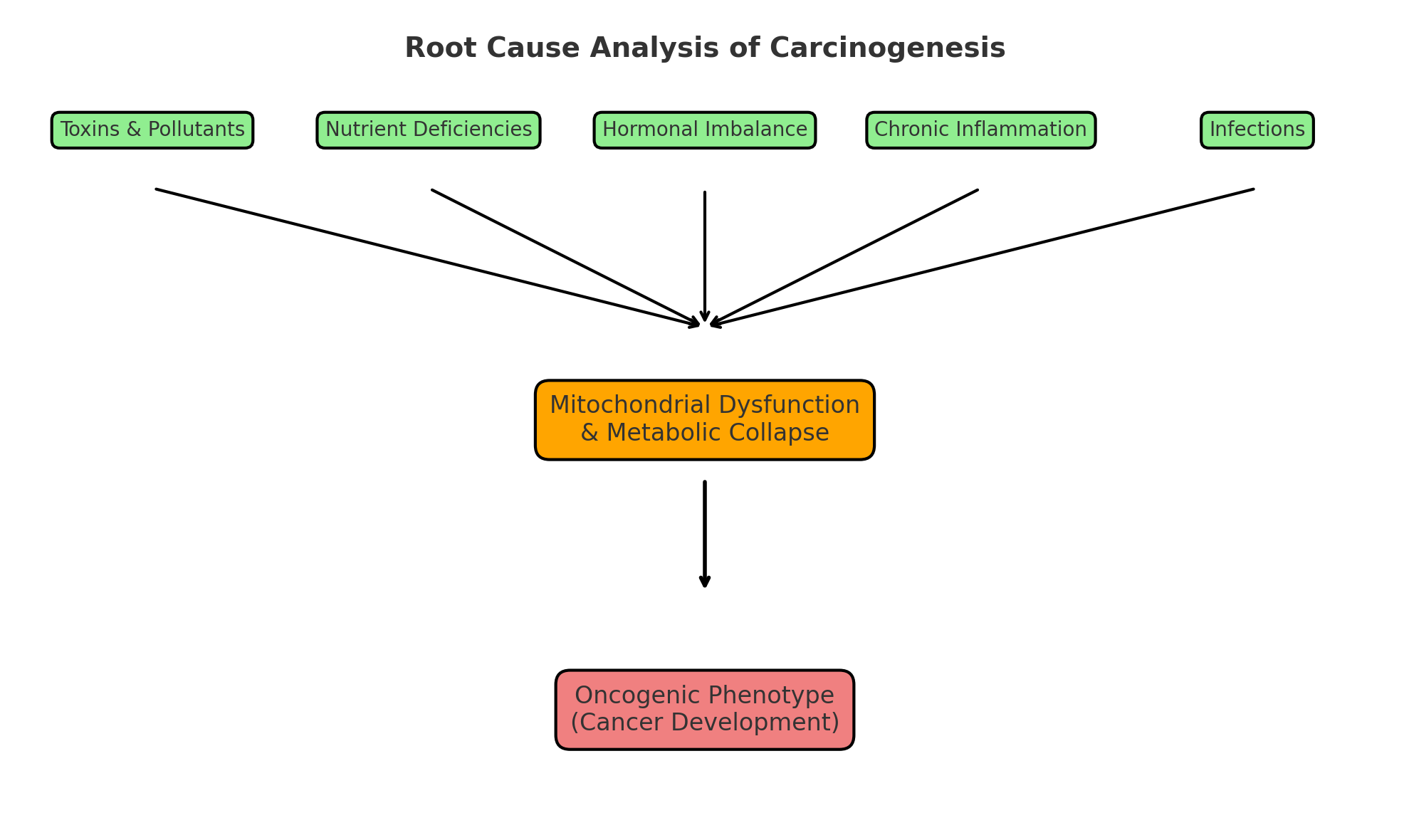

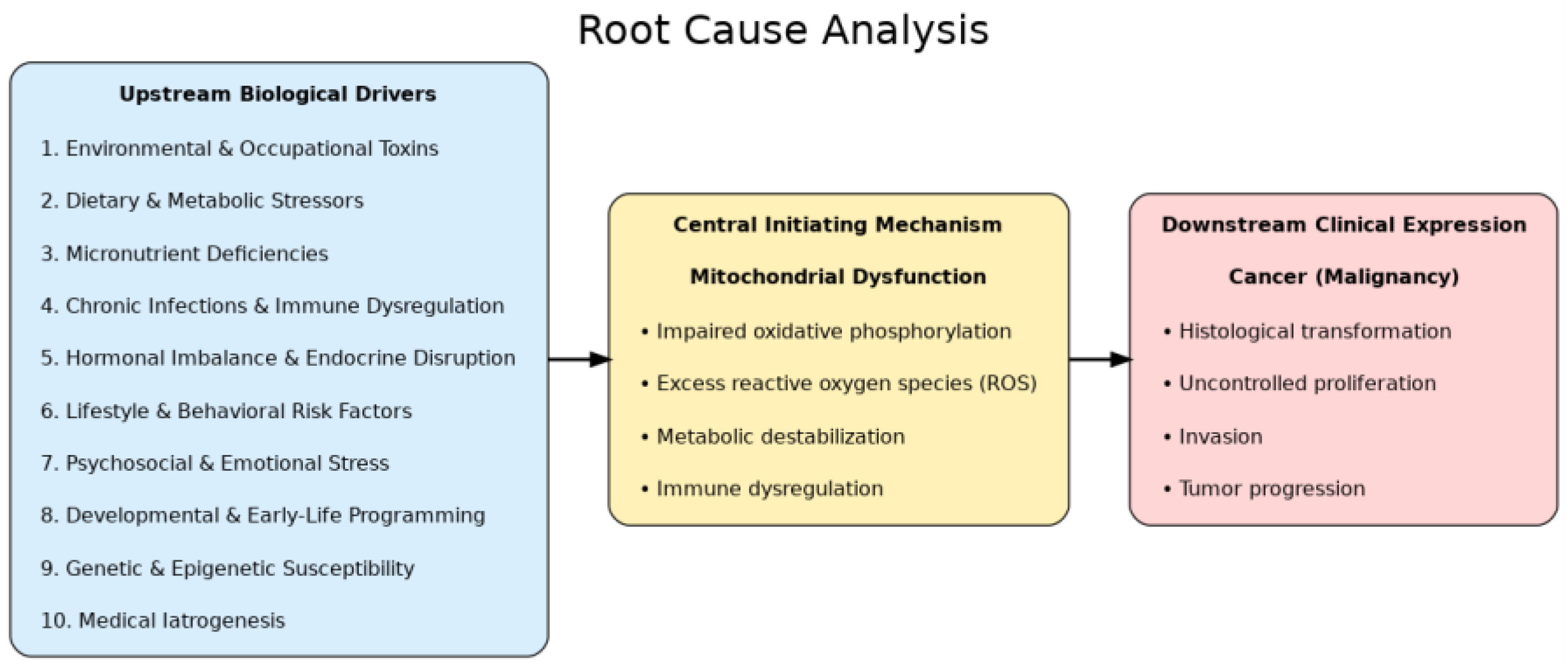

2. Conceptual Framework: Applying Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to Carcinogenesis

-

Upstream biological drivers include

- Environmental & Occupational Toxins;

- Dietary & Metabolic Stressors;

- Micronutrient Deficiencies;

- Chronic Infections & Immune Dysregulation;

- Hormonal Imbalance & Endocrine Disruption;

- Lifestyle & Behavioral Risk Factors;

- Psychosocial & Emotional Stress;

- Developmental & Early-Life Programming;

- Genetic & Epigenetic Susceptibility;

- Medical Iatrogenesis

- Central initiating mechanism is mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by impaired oxidative phosphorylation, excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), metabolic destabilization, and immune dysregulation.

- Downstream clinical expression is cancer (malignancy), manifesting as histological transformation, uncontrolled proliferation, invasion, and tumor progression.

2.1. Scientific Justification of RCA in Complex, Nonlinear Systems like Cancer

- Convergent failure modes (e.g., mitochondrial collapse) can arise from diverse upstream inputs [23];

- Complements reductionist models by embedding them in a systems logic;

- Supports mechanistic mapping from exposure to phenotype;

- Offers practical, testable hypotheses at molecular, cellular, and population levels.

3. Overview of Major Theories of Carcinogenesis

3.1. Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT) – The Prevailing Paradigm

- Has dominated cancer research, drug development, and public messaging since the 1970s.

-

- Many tumors lack clear driver mutations.

- Fails to account for non-genetic causes of transformation.

- Targeted therapies based on this model often show limited durability and modest survival benefit.

- SMT has not only failed to account for the majority of cancers, but its dominance has actively delayed the exploration of more plausible upstream metabolic explanations.

3.2. Viral and Infectious Theories

- Examples: HPV (cervical cancer), EBV (nasopharyngeal carcinoma), H. pylori (gastric cancer), HBV/HCV (hepatocellular carcinoma).

- Estimated to contribute to ~15–20% of global cancer burden, especially in low-income regions [28].

3.3. Epigenetic Dysregulation

- Attributes cancer to reversible changes in gene expression—including DNA methylation, histone modification, and chromatin remodeling—rather than irreversible mutations [31].

-

Explains key cancer features:

- ○

- Cell plasticity

- ○

- Phenotypic heterogeneity

- ○

- Therapy resistance [32].

- Enabled therapeutic approaches such as HDAC inhibitors and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors [33].

3.4. Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Theory

- Proposes that a subpopulation of stem-like tumor-initiating cells drives cancer initiation, progression, and recurrence [36].

-

CSCs exhibit:

- ○

- Self-renewal

- ○

- Metabolic flexibility

- ○

- Chemoresistance and radioresistance [37].

-

Notably, CSCs show metabolic traits consistent with the mitochondrial model:

- Their behavior is shaped by a permissive tumor microenvironment involving hypoxia, inflammation, and immune suppression [40].

3.5. Immune Surveillance and Immune Escape Theories

-

Forms the theoretical foundation for immunotherapies, including checkpoint inhibitors [16].Limitation: Immune dysfunction is often a consequence of upstream issues such as:

3.6. Mitochondrial Metabolic Theory (Warburg–Seyfried Model)

- Warburg first observed a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis—known as the Warburg effect [15].

-

Seyfried extended the model by demonstrating:

- ○

- Mitochondrial damage precedes genetic instability

- ○

- Restoring mitochondrial function suppresses tumorigenesis—even in cells with nuclear mutations.

- Cytoplasmic–nuclear transfer experiments further show that healthy mitochondria can reverse tumorigenic potential.

- The ketogenic diet exploits this vulnerability—targeting cancer cells’ dependence on glucose and glutamine—but it does not fully address the upstream initiating drivers of cancer. Without simultaneous attention to toxins, infections, nutrient deficiencies, and hormonal disruption, the root causes of mitochondrial collapse remain uncorrected. Thus, diet should be seen as a critical but partial tool within a broader framework.

- While the MMT correctly centers mitochondrial dysfunction, it often risks being interpreted in isolation. This limitation sets the stage for expansion: mitochondria are not ultimate causes, but vulnerable sentinels shaped by upstream biological stressors.

3.7. Chromosomal Instability and Aneuploidy Theory

-

Aneuploidy induces:

- Poor predictive power in early tumor development.

- Fails to explain what initiates aneuploidy [47].

3.8. Synthesis and Transition: Toward a Systems-Based RCA Framework

4. From Mutation to Metabolism—and Beyond

5. Initiating Drivers of Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Systems-Based Overview

5.1. Environmental & Occupational Toxins

- Nanoparticles & microplastics: industrial and food-chain exposure [50]

5.2. Dietary & Metabolic Stressors

5.3. Micronutrient Deficiencies

5.4. Chronic Infections & Immune Dysregulation

-

Oncoviruses:

-

Bacterial infections:

-

Chronic fungal and parasitic infections:

-

Immune exhaustion and dysregulation:

5.5. Hormonal Imbalance & Endocrine Disruption

- Estrogen dominance & low progesterone: linked to breast and endometrial cancer via proliferative signaling and impaired apoptosis [85].

- Insulin resistance & hyperinsulinemia: activate IGF-1 and mTOR pathways, promoting anabolic, pro-cancer metabolism [86].

- Thyroid dysfunction: impairs mitochondrial oxygen use and ATP production [87].

- Cortisol dysregulation & HPA axis stress: suppress immune surveillance and promote chronic inflammation [88].

-

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs):

5.6. Lifestyle & Behavioral Risk Factors

- High-risk sexual behavior: increases exposure to oncogenic viruses (e.g., HPV)

5.7. Psychosocial & Emotional Stress

- Sleep deprivation and circadian disruption: Disturbances in daylight exposure, shift work, and poor sleep quality suppress melatonin (an oncostatic hormone), impair DNA repair, and disturb antioxidant cycling. Night shift work is classified as "probably carcinogenic" by IARC (Group 2A) due to these mechanisms [108,109].

- Social isolation & emotional loneliness: Meta-analyses find that chronic loneliness and isolation are associated with increased all-cause and cancer-specific mortality—likely through immune dysfunction and elevated inflammatory markers [110].

5.8. Developmental & Early-Life Programming

- Gestational metabolic stress: maternal obesity, insulin resistance, and gestational diabetes increase childhood cancer risk [117]

5.9. Genetic & Epigenetic Susceptibility

- Family history of cancer in high-risk environments: reflects both shared genes and shared exposures [134]

5.10. Medical Iatrogenesis

- Excessive antibiotic use: disrupts the gut microbiome, weakens immune defenses, and promotes inflammation

6. From Mechanism to Policy: Implications for Public Health

6.1. Environmental Regulation

- Ban or restrict high-risk exposures such as glyphosate, PFAS, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and EMF-emitting infrastructure in residential zones.

- Enforce industrial detoxification mandates and environmental remediation.

- Mandate transparency and labeling of known carcinogenic or mitochondrial-disrupting chemicals.

6.2. Nutritional Policy

- Eliminate subsidies for refined grains, added sugars, and industrial seed oils.

- Prioritize nutrient-dense, whole-food dietary models (e.g., low-carbohydrate, anti-inflammatory) in public nutrition programs.

- Implement targeted micronutrient fortification based on population-level deficiency data.

6.3. Infection Control

- Screen for chronic latent infections (e.g., HPV, EBV, H. pylori) in high-risk groups.

- Integrate immune-nutritional interventions (vitamins C, D, zinc, selenium) into preventive protocols.

- Reassess vaccine formulations with regard to mitochondrial safety and adjuvant toxicity.

6.4. Medical Reform

- Shift clinical care from pharma-driven symptom suppression to nutritional, metabolic, and detoxification therapies.

- Redirect research funding toward prevention, environmental detoxification, and metabolic oncology.

- Incorporate systems-based RCA training into medical education, emphasizing initiating drivers and early mitochondrial disruption.

7. Discussion: Toward an IOM Framework for Cancer Prevention and Reversal

- Cellular health as the foundation of systemic health

- Safety, accessibility, and sustainability over drug-centric interventions

- Prevention-first strategies, grounded in nutrition, detoxification, and metabolic repair

- Nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diets

- Mitochondrial support and metabolic flexibility

- Toxin exposure reduction and detoxification support

- Circadian alignment and lifestyle rhythm restoration

8. Conclusion: Reframing Cancer as a Systems-Initiated, Mitochondrial Disease

- From reaction to proactive prevention

- From genetic determinism to metabolic resilience

- From symptom suppression to initiating driver mitigation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| RCA | Root Cause Analysis |

| SMT | Somatic Mutation Theory |

| MMT | Mitochondrial Metabolic Theory |

| IOM | Integrative Orthomolecular Medicine |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

References

- Zarocostas, J. Global Cancer Cases and Deaths Are Set to Rise by 70% in next 20 Years. BMJ 2010, 340, c3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilleron, S.; Sarfati, D.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Global Cancer Incidence in Older Adults, 2012 and 2035: A Population-Based Study. Int J Cancer 2019, 144, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladanie, A.; Schmitt, A.M.; Speich, B.; Naudet, F.; Agarwal, A.; Pereira, T.V.; Sclafani, F.; Herbrand, A.K.; Briel, M.; Martin-Liberal, J.; et al. Clinical Trial Evidence Supporting US Food and Drug Administration Approval of Novel Cancer Therapies Between 2000 and 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e2024406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Fojo, T.; Chamberlain, C.; Davis, C.; Sullivan, R. Do Patient Access Schemes for High-Cost Cancer Drugs Deliver Value to Society?-Lessons from the NHS Cancer Drugs Fund. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 2017, 28, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Naci, H.; Wagner, A.K.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ji, J.; Shi, L.; Guan, X. Overall Survival Benefits of Cancer Drugs Approved in China From 2005 to 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2225973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Pramesh, C.S.; Booth, C.M. Cancer Patients Need Better Care, Not Just More Technology. Nature 2017, 549, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.; Ward, R.; Barton, M. The Contribution of Cytotoxic Chemotherapy to 5-Year Survival in Adult Malignancies. Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)) 2004, 16, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naci, H.; Zhang, Y.; Woloshin, S.; Guan, X.; Xu, Z.; Wagner, A.K. Overall Survival Benefits of Cancer Drugs Initially Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration on the Basis of Immature Survival Data: A Retrospective Analysis. Lancet Oncol 2024, 25, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, J.; Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. An Empirical Analysis of Overall Survival in Drug Approvals by the US FDA (2006-2023). Cancer Med 2024, 13, e7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, D.T.; Michaeli, J.C.; Michaeli, T. Advances in Cancer Therapy: Clinical Benefit of New Cancer Drugs. Aging (Albany NY) 2023, 15, 5232–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimets, T. Cancer Research and the Mainstream of Biology. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1623849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, T.N. Cancer as a Metabolic Disease: On the Origin, Management, and Prevention of Cancer, 1st ed.; Wiley, 2012; ISBN 0-470-58492-0. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Shelton, L.M. Cancer as a Metabolic Disease. Nutrition & Metabolism 2010, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Patel, R.H.; Vaqar, S.; Boster, J. Root Cause Analysis and Medical Error Prevention. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Peerally, M.F.; Carr, S.; Waring, J.; Dixon-Woods, M. The Problem with Root Cause Analysis. BMJ Qual Saf 2017, 26, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinicola, S.; D’Anselmi, F.; Pasqualato, A.; Proietti, S.; Lisi, E.; Cucina, A.; Bizzarri, M. A Systems Biology Approach to Cancer: Fractals, Attractors, and Nonlinear Dynamics. OMICS 2011, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A.M.; Sonnenschein, C. The Somatic Mutation Theory of Cancer: Growing Problems with the Paradigm? Bioessays 2004, 26, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. Perspective: Reductionist Nutrition Research Has Meaning Only within the Framework of Holistic and Ethical Thinking. Adv Nutr 2018, 9, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondria and Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLoS Med 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genes and the Pathways They Control. Nat Med 2004, 10, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Flores, R.E.; Poff, A.M.; D’Agostino, D.P. Cancer as a Metabolic Disease: Implications for Novel Therapeutics. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses in the Causation of Human Cancers - a Brief Historical Account. Virology 2009, 384, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global Burden of Cancer Attributable to Infections in 2018: A Worldwide Incidence Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, M.; de Martel, C.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Franceschi, S. Global Burden of Cancers Attributable to Infections in 2012: A Synthetic Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016, 4, e609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damania, B.; Münz, C. Immunodeficiencies That Predispose to Pathologies by Human Oncogenic γ-Herpesviruses. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2019, 43, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetic Determinants of Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016, 8, a019505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easwaran, H.; Tsai, H.-C.; Baylin, S.B. Cancer Epigenetics: Tumor Heterogeneity, Plasticity of Stem-like States, and Drug Resistance. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.K.; De Carvalho, D.D.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetic Modifications as Therapeutic Targets. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feil, R.; Fraga, M.F. Epigenetics and the Environment: Emerging Patterns and Implications. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillycrop, K.A.; Burdge, G.C. Epigenetic Changes in Early Life and Future Risk of Obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011, 35, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem Cells, Cancer, and Cancer Stem Cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Fojo, T.; Bates, S. Tumour Stem Cells and Drug Resistance. Nat Rev Cancer 2005, 5, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlashi, E.; Lagadec, C.; Vergnes, L.; Matsutani, T.; Masui, K.; Poulou, M.; Popescu, R.; Della Donna, L.; Evers, P.; Dekmezian, C.; et al. Metabolic State of Glioma Stem Cells and Nontumorigenic Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 16062–16067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P.; Barneda, D.; Heeschen, C. Hallmarks of Cancer Stem Cell Metabolism. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, D.; Blanpain, C. Cancer Stem Cells: Basic Concepts and Therapeutic Implications. Annu Rev Pathol 2016, 11, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnet, F.M. The Concept of Immunological Surveillance. Prog Exp Tumor Res 1970, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.P.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. The Immunobiology of Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunoediting. Immunity 2004, 21, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzat, V.; Macedo Rogero, M.; Noel Keane, K.; Curi, R.; Newsholme, P. Glutamine: Metabolism and Immune Function, Supplementation and Clinical Translation. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.D.; Marty, M.A. Impact of Environmental Chemicals on Lung Development. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesberg, P.; Li, R.; Fabarius, A.; Hehlmann, R. The Chromosomal Basis of Cancer. Cell Oncol 2005, 27, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesberg, P.; Mandrioli, D.; McCormack, A.; Nicholson, J.M. Is Carcinogenesis a Form of Speciation? Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2100–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasnick, D. Aneuploidy Theory Explains Tumor Formation, the Absence of Immune Surveillance, and the Failure of Chemotherapy. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2002, 136, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of Lead: A Review with Recent Updates. Interdisciplinary Toxicology 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Hospital, C.; Tête, A.; Brial, F.; Benoit, L.; Koual, M.; Tomkiewicz, C.; Kim, M.J.; Blanc, E.B.; Coumoul, X.; Bortoli, S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Hallmark of Environmental Injury. Cells 2021, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddam, A.; McLarnan, S.; Kupsco, A. Environmental Chemical Exposures and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Review of Recent Literature. Curr Environ Health Rep 2022, 9, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G.; Srinivasan, S.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K.; Avadhani, N.G. Dioxin-Mediated Tumor Progression through Activation of Mitochondria-to-Nucleus Stress Signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolet, T.; Srour, B.; Sellem, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Deschasaux, M.; Fassier, P.; Latino-Martel, P.; Beslay, M.; et al. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Cancer Risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé Prospective Cohort. BMJ 2018, 360, k322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Nakagawa, T.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G.; Shafiu, M.; Sundaram, S.; Le, M.; Ishimoto, T.; Sautin, Y.Y.; Lanaspa, M.A. Sugar, Uric Acid, and the Etiology of Diabetes and Obesity. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Sun, T.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Tian, L. Carbohydrate Quality vs Quantity on Cancer Risk: Perspective of Microbiome Mechanisms. Journal of Functional Foods 2024, 118, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmin Stan, M.; Paul, D. Diabetes and Cancer: A Twisted Bond. Oncol Rev 2024, 18, 1354549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.E.; Zamora, D.; Leelarthaepin, B.; Majchrzak-Hong, S.F.; Faurot, K.R.; Suchindran, C.M.; Ringel, A.; Davis, J.M.; Hibbeln, J.R. Use of Dietary Linoleic Acid for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Death: Evaluation of Recovered Data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and Updated Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2013, 346, e8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.T.; Nara, T.Y. Structure, Function, and Dietary Regulation of Delta6, Delta5, and Delta9 Desaturases. Annu Rev Nutr 2004, 24, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet. J Am Diet Assoc 2010, 110, 911–916.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, Y.-G.; Lin, Y.-C.; Kuo, C.-H.; Tsai, M.-L.; Kuo, C.-H.; Liao, W.-T. Acrylamide Induces Mitophagy and Alters Macrophage Phenotype via Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Soeters, M.R.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Houtkooper, R.H. Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. Endocr Rev 2018, 39, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Fu, K.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D.; He, W.; Yang, L.-L. Energy Metabolism in Health and Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, D.I.; Stuelcken, M.; Eagles, A. Exercise Testing for Metabolic Flexibility: Time for Protocol Standardization. Sports Med Open 2025, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Wimalawansa, S.J.; Pludowski, P.; Cheng, R.Z. Vitamin D: Evidence-Based Health Benefits and Recommendations for Population Guidelines. Nutrients 2025, 17, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, C.F.; Garland, F.C.; Gorham, E.D.; Lipkin, M.; Newmark, H.; Mohr, S.B.; Holick, M.F. The Role of Vitamin D in Cancer Prevention. Am J Public Health 2006, 96, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, K.A. Vitamin C in Human Health and Disease Is Still a Mystery? An Overview. Nutr J 2003, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.; Conry-Cantilena, C.; Wang, Y.; Welch, R.W.; Washko, P.W.; Dhariwal, K.R.; Park, J.B.; Lazarev, A.; Graumlich, J.F.; King, J.; et al. Vitamin C Pharmacokinetics in Healthy Volunteers: Evidence for a Recommended Dietary Allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 3704–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, B.C.; Mack, M.M.; Wehr, C.M.; MacGregor, J.T.; Hiatt, R.A.; Wang, G.; Wickramasinghe, S.N.; Everson, R.B.; Ames, B.N. Folate Deficiency Causes Uracil Misincorporation into Human DNA and Chromosome Breakage: Implications for Cancer and Neuronal Damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 3290–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucock, M. Folic Acid: Nutritional Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Role in Disease Processes. Mol Genet Metab 2000, 71, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagallo, M.; Veronese, N.; Dominguez, L.J. Magnesium in Aging, Health and Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, R. Magnesium Metabolism and Its Disorders. Clin Biochem Rev 2003, 24, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rayman, M.P. Selenium and Human Health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W.; Sandstead, H.H. Zinc Requirements and the Risks and Benefits of Zinc Supplementation. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2006, 20, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zur Hausen, H. The Search for Infectious Causes of Human Cancers: Where and Why. Virology 2009, 392, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, F.X.; Lorincz, A.; Muñoz, N.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Shah, K.V. The Causal Relation between Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. J Clin Pathol 2002, 55, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, L.S.; Rickinson, A.B. Epstein-Barr Virus: 40 Years On. Nat Rev Cancer 2004, 4, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; He, S.; Zhu, W.; Ru, P.; Ge, X.; Govindasamy, K. Human Cytomegalovirus in Cancer: The Mechanism of HCMV-Induced Carcinogenesis and Its Therapeutic Potential. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1202138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 2002, 36, S74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, L.E.; Peek, R.M.; Wilson, K.T. Helicobacter Pylori and Gastric Cancer: Factors That Modulate Disease Risk. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010, 23, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, E.; Saed Abdul-Wahab, O.M.; Al-Shyarba, M.H.; Ben Abdelmoumen Mardassi, B. The Relationship between Mycoplasmas and Cancer: Is It Fact or Fiction ? Narrative Review and Update on the Situation. J Oncol 2021, 2021, 9986550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, J.D.; Davidson, N.E. Estrogen Carcinogenesis in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2006, 354, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M. Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factor Signalling in Neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer 2008, 8, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrutniak-Cabello, C.; Casas, F.; Cabello, G. Thyroid Hormone Action in Mitochondria. J Mol Endocrinol 2001, 26, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiche, E.M.V.; Nunes, S.O.V.; Morimoto, H.K. Stress, Depression, the Immune System, and Cancer. Lancet Oncol 2004, 5, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.-P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocrine Reviews 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heindel, J.J.; Blumberg, B.; Cave, M.; Machtinger, R.; Mantovani, A.; Mendez, M.A.; Nadal, A.; Palanza, P.; Panzica, G.; Sargis, R.; et al. Metabolism Disrupting Chemicals and Metabolic Disorders. Reprod Toxicol 2017, 68, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Millán, I. The Key Role of Mitochondrial Function in Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Ruisoto, P.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Metabolic Health, Mitochondrial Fitness, Physical Activity, and Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, J.L.; Sammy, M.J.; Ballinger, S.W. Mitochondrial Toxicity of Tobacco Smoke and Air Pollution. Toxicology 2017, 391, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Harrison, C.M.; Chuang, G.C.; Ballinger, S.W. The Role of Tobacco Smoke Induced Mitochondrial Damage in Vascular Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Mutat Res 2007, 621, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Acetaldehyde as an Underestimated Risk Factor for Cancer Development: Role of Genetics in Ethanol Metabolism. Genes Nutr 2010, 5, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, H.K.; Becker, P. Alcohol Metabolism and Cancer Risk. Alcohol Res Health 2007, 30, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alcohol and Cancer Risk Fact Sheet - NCI. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/alcohol/alcohol-fact-sheet (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Rodríguez-Santana, C.; Florido, J.; Martínez-Ruiz, L.; López-Rodríguez, A.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D.; Escames, G. Role of Melatonin in Cancer: Effect on Clock Genes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szataniak, I.; Packi, K. Melatonin as the Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation and Immune Dysregulation: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Cancer, Sunlight and Vitamin D. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2014, 1, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond-Lezman, J.R.; Riskin, S.I. Benefits and Risks of Sun Exposure to Maintain Adequate Vitamin D Levels. Cureus 2023, 15, e38578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.J.; Alenezi, S.K.; Alhowail, A.H. Molecular Insights into the Pathogenic Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency in Neurological Disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lei, M.; Bai, Y. Chronic Stress Mediates Inflammatory Cytokines Alterations and Its Role in Tumorigenesis. J Inflamm Res 2025, 18, 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignjević Petrinović, S.; Milošević, M.S.; Marković, D.; Momčilović, S. Interplay between Stress and Cancer-A Focus on Inflammation. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1119095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Jackson, B.; Manzo, L.L.; Jeon, S.; Poghosyan, H. Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Self-Reported Health-Risk Behaviors among Cancer Survivors: A Population-Based Study. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0299918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.; Thacker, L.R.; Cohen, S.A. Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Diagnosis of Cancer. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e65524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, Y.; Luo, M.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zou, Z. Chronic Stress in Solid Tumor Development: From Mechanisms to Interventions. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, L.B.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Roecklein, K.A.; Hall, M.H. Sleep and Circadian Disruption and Incident Breast Cancer Risk: An Evidence-Based and Theoretical Review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018, 84, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, M.; Chen, F.; Chen, L. Circadian Rhythm Regulates the Function of Immune Cells and Participates in the Development of Tumors. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheldon, C.W.; Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A.; McCormick, B.P.; Albertorio-Díaz, J.R. Loneliness among Adult Cancer Survivors in the United States: Prevalence and Correlates. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommarito, P.A.; Martin, E.; Fry, R.C. Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors and Toxic Metals on the Fetal Epigenome. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ma, C.; Li, Q.; Hang, J.G.; Shen, J.; Nakayama, S.F.; Kido, T.; Lin, Y.; Feng, H.; Jung, C.-R.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Heavy Metals and Adverse Birth Outcomes: Evidence From an E-Waste Area in China. Geohealth 2023, 7, e2023GH000897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gernand, A.D.; Schulze, K.J.; Stewart, C.P.; West, K.P.; Christian, P. Micronutrient Deficiencies in Pregnancy Worldwide: Health Effects and Prevention. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016, 12, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordeleau, M.; Fernández de Cossío, L.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Tremblay, M.-È. From Maternal Diet to Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Story of Neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F. The Impact of Nutritional Deficiencies During Pregnancy: A Comprehensive Overview. Maternal and Pediatric Nutrition 2024, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, S. They Are What You Eat: Can Nutritional Factors during Gestation and Early Infancy Modulate the Neonatal Immune Response? Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marley, A.R.; Domingues, A.; Ghosh, T.; Turcotte, L.M.; Spector, L.G. Maternal Body Mass Index, Diabetes, and Gestational Weight Gain and Risk for Pediatric Cancer in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2022, 6, pkac020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.L.; Jiang, X.P.; Baucom, C.C. Antibiotic Overusage Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction Which May Promote Tumorigenesis. J. Cancer Treat. Res. 2017, 5, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antibiotics-Induced Obesity: A Mitochondrial Perspective | Public Health Genomics | Karger Publishers. Available online: https://karger.com/phg/article-abstract/20/5/257/272852/Antibiotics-Induced-Obesity-A-Mitochondrial?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Monzer, N.; Hartmann, M.; Buckert, M.; Wolff, K.; Nawroth, P.; Kopf, S.; Kender, Z.; Friederich, H.-C.; Wild, B. Associations of Childhood Neglect With the ACTH and Plasma Cortisol Stress Response in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 679693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlman, K.R.; Vargas, I.; Geiss, E.G.; Lopez-Duran, N.L. Age of Trauma Onset and HPA Axis Dysregulation Among Trauma-Exposed Youth. J Trauma Stress 2015, 28, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Amavizca, B.E.; Orozco-Castellanos, R.; Ortíz-Orozco, R.; Padilla-Gutiérrez, J.; Valle, Y.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, N.; García-García, G.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.; Figuera, L.E. Contribution of GSTM1, GSTT1, and MTHFR Polymorphisms to End-Stage Renal Disease of Unknown Etiology in Mexicans. Indian J Nephrol 2013, 23, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, G.S.; Cheng, R.Z. The Immature Infant Liver: Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Their Relevance to Vaccine Safety and SIDS Research. Int J Med Sci 2025, 22, 2434–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, L.; Ordovas, J.M.; Volkov, A.; Lamb, J.J.; Stone, P.M.; Minich, D.; Leary, M.; Class, M.; Metti, D.; Larson, I.A.; et al. Genetic Biomarkers of Metabolic Detoxification for Personalized Lifestyle Medicine. Nutrients 2022, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, E.A.; DiMauro, S.; Hirano, M. Human Mitochondrial DNA: Roles of Inherited and Somatic Mutations. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanka, N.; Moraes, C.T. Mitochondrial DNA Damage and Reactive Oxygen Species in Neurodegenerative Disease. FEBS Lett 2018, 592, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprani, S.M.; Mordukhovich, I.; McNeely, E.; Nagel, Z.D. Suppressed DNA Repair Capacity in Flight Attendants after Air Travel. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 16513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Y.; Haj, M.; Ziv, Y.; Elkon, R.; Shiloh, Y. Broad Repression of DNA Repair Genes in Senescent Cells Identified by Integration of Transcriptomic Data. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, gkae1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, U.S.; Tan, B.W.Q.; Vellayappan, B.A.; Jeyasekharan, A.D. ROS and the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría-Torres, J.A.; Baccarelli, A.; Bollati, V. Epigenetics and Lifestyle. Epigenomics 2011, 3, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekdash, R.A. Epigenetics, Nutrition, and the Brain: Improving Mental Health through Diet. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savic, B.; Savic, B.; Stanojlovic, S. Epigenetic DNA Methylation Under the Influence of Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation, and Supplementation with Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid: Harmful or Beneficial for Professionals? Epigenomes 2025, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, P.; Holm, N.V.; Verkasalo, P.K.; Iliadou, A.; Kaprio, J.; Koskenvuo, M.; Pukkala, E.; Skytthe, A.; Hemminki, K. Environmental and Heritable Factors in the Causation of Cancer--Analyses of Cohorts of Twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 2000, 343, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominic, A.; Hamilton, D.; Abe, J.-I. Mitochondria and Chronic Effects of Cancer Therapeutics: The Clinical Implications. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2021, 51, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Ma, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Shi, R.; Zhou, Q. DNA Damage Caused by Chemotherapy Has Duality, and Traditional Chinese Medicine May Be a Better Choice to Reduce Its Toxicity. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1483160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Boogaard, W.M.C.; Komninos, D.S.J.; Vermeij, W.P. Chemotherapy Side-Effects: Not All DNA Damage Is Equal. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-X.; Zhou, P.-K. DNA Damage Response Signaling Pathways and Targets for Radiotherapy Sensitization in Cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Second Cancers Related to Treatment. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/survivorship/long-term-health-concerns/second-cancers-in-adults/treatment-risks.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Indari, O.; Ghosh, S.; Bal, A.S.; James, A.; Garg, M.; Mishra, A.; Karmodiya, K.; Jha, H.C. Awakening the Sleeping Giant: Epstein–Barr Virus Reactivation by Biological Agents. Pathogens and Disease 2024, 82, ftae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Rasizadeh, R.; Sharaflou, S.; Aghbash, P.S.; Shamekh, A.; Jafari-Sales, A.; Bannazadeh Baghi, H. Coinfection of EBV with Other Pathogens: A Narrative Review. Front. Virol. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewavisenti, R.V.; Arena, J.; Ahlenstiel, C.L.; Sasson, S.C. Human Papillomavirus in the Setting of Immunodeficiency: Pathogenesis and the Emergence of next-Generation Therapies to Reduce the High Associated Cancer Risk. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1112513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Does Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) Increase the Risk of Cancer? Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/hormones-and-cancer/does-hormone-replacement-therapy-increase-cancer-risk (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Vinogradova, Y.; Coupland, C.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Use of Hormone Replacement Therapy and Risk of Breast Cancer: Nested Case-Control Studies Using the QResearch and CPRD Databases. BMJ 2020, 371, m3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-F.; Ma, K.-L.; Shan, H.; Liu, T.-F.; Zhao, S.-Q.; Wan, Y.; Jun-Zhang, null; Wang, H.-Q. CT Scans and Cancer Risks: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, D. Radiation Exposure in Recurrent Medical Imaging: Identifying Drivers and High-Risk Populations. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Definition | Representative Factors / Mechanisms | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Upstream Biological Drivers | Modifiable exposures and conditions that destabilize cellular homeostasis and predispose to mitochondrial damage | Environmental & Occupational Toxins; Dietary & Metabolic Stressors; Micronutrient Deficiencies; Chronic Infections & Immune Dysregulation; Hormonal Imbalance & Endocrine Disruption; Lifestyle & Behavioral Risk Factors; Psychosocial & Emotional Stress; Developmental & Early-Life Programming; Genetic & Epigenetic Susceptibility; Medical Iatrogenesis | Identifies modifiable drivers for prevention and early intervention |

| 2. Central Initiating Mechanism: Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Collapse of oxidative phosphorylation and loss of metabolic stability that directly trigger malignant transformation | Impaired oxidative phosphorylation; excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress; metabolic destabilization; immune dysregulation | Provides proximate target for therapeutic strategies (metabolic, nutritional, pharmacologic) |

| 3. Downstream Clinical Expression | Phenotypic outcomes of mitochondrial dysfunction manifesting as cancer | Histological transformation; uncontrolled proliferation; invasion; tumor progression | Guides clinical diagnosis, staging, and integrative disease management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).