1. Introduction

In the 1920’s, Tsander and Tsiolkvosy proposed using radiation pressure from the stars to propel objects in space[

1,

2]. Over the past half century numerous organizations (e.g., NASA, JAXA, ESA, and The Planetary Society) have developed mission concepts and in-space demonstrations [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, studies on both transmissive and reflective sails have been conducted analyzing the sail’s flight dynamics and survivability on low-earth-orbit trajectories as well as diffractive sails in displaced orbits for asteroid deflection [

7,

8]. Perhaps the most promising class of such missions achieves inward (outward) spiral trajectories by decreasing (increasing) the orbital velocity, i.e., by producing a force perpendicular to the sun line. This force is attributed to the change of optical momentum owing to light scattering. A reflective solar sail tilted by roughly

from the sun line was originally proposed for this mission type. At that angle an ideal reflective sail converts

of the available optical momentum into the component of force perpendicular to the sun line. In practice the efficiency will be smaller than this value owing to a combination of absorption in the metallic layer, wrinkling and bowing, diffuse scattering, and re-radiated heat [

9]. Additionally, the

cant angle of a reflective sail may introduce a misalignment between science instruments and the sail axis, posing engineering challenges such as momentum management and thermal control. More technically difficult solar sailing missions seek to achieve large accelerations along the sun line, placing for example a solar sail at the gravitational lensing point of the sun [

10,

11].

The law of conservation of linear momentum suggests that the transverse momentum transfer efficiency may reach

if two ideal conditions are satisfied: the sail is sun-facing (i.e., not tilted), and all available sunlight scatters in a single

direction. There is no known optical phenomenon that satisfies these conditions for wavelengths spanning the entire solar spectrum. Diffractive sails were proposed as a means to address the sun-facing condition [

12] and to explore whether large momentum transfer efficiencies can be reached. Radiation pressure has been directly measured on commercially available diffraction gratings [

13], as well as geometric phase gratings [

14]. Measurements have also been recently reported on a microscopic metasurface [

15]. Orbital trajectories of diffractive sails in the sun-facing condition have also been explored [

16,

17,

18].

In the ideal case long period gratings were found to be more favorable for achieving large values of the net transverse momentum transfer efficiency (MTE) compared to short period gratings [

19] . In practice light does not exhibit ideal scattering. For example surface relief gratings impose obstructions from the facets, scattering light in undesirable directions. Here, we propose a potential solution to this problem by designing a partially reflective hybrid grating that reflects light from the front facets and transmits light through the side facets, as depicted in

Figure 1. If a significant fraction of sunlight can be cast at a large average angle then a hybrid diffractive sail may have advantages that differ from those of a flat canted reflective sail.

This report is organized into the following sections. The principle of momentum transfer is used to describe radiation pressure in

Section 2. Ray tracing using geometric optics principles is used to estimate radiation pressure on a right prism in

Section 3. The reflected and refracted ray directions may be used to describe the optical field near a grating comprised of a periodic array of such prisms. Wavelength dispersion and polarization are ignored in

Section 3. Far from the grating the optical field is described with wave theory, which is reviewed in

Section 4. In this section the MTE is wavelength dependent owing to diffraction, and thus the net MTE is found by integration over the spectral irradiance distribution of the light source. Both

Section 2 and

Section 3 provide tractable equations that aid in the design of diffractive light sail. These two approaches do not account for physical phenomena such as polarization-dependent Fresnel reflection and transmission coefficients, and internal reflections within the structure. More accurate modeling requires the use of a numerical Maxwell solver. Using such solvers we calculate the MTE using two methods: The Maxwell stress tensor in

Section 6, and in

Section 7 a rigorous modal analysis that is closely aligned with

Section 4. Results from the latter two approaches are discussed in

Section 8. Preliminary experimental results are presented in

Section 9 for a long period grating (

) [

20]. The concluding section includes a comparison between the MTE values obtained using both the geometric optics approximation and the Maxwell solver solutions. For example, at a refractive index of

, a prism angle of

, and a grating period of

the geometric optics approximation

greatly overestimates the Maxwell solver value

. We attribute this discrepancy to the fact that the wavelength of light are on the same order of magnitude as the grating period, resulting in strong diffraction effects not accounted for by the geometric model. On the other hand, when the grating period is much greater than the illuminating wavelengths, geometric optics is expected to provide a better agreement. In fact, the experimentally measured MTE values using a grating period of

is in good agreement with the geometric optics value:

v.s.

, respectively.

2. Radiation Pressure Review

The force owing to radiation pressure may be understood by combining Newton’s second law, which asserts that the force on a body is equal to the change of momentum per unit time, and Newton’s third law, stating that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction [

21]. Let us describe light of wavelength

as a collection of rays or photons having momentum

where

ℏ is the Planck constant and

is the magnitude of the wave vector. If incident and elastically scattered wave vectors,

and

subtend the optical axis with angles

and

respectively, then the relative change of the momentum provided to the scatter may may be expressed

In the case

there is no scattering and Equation (

1) provides

as expected. Further, if light is back scattered (e.g., light normal incident upon an ideal mirror) such that

then

, providing a magnitude

is the direction of the incident beam. As another example, consider light scattered at right angles to the incident beam such that

so that

. Projecting

onto the incident direction provides a relative momentum change of

in that direction. Furthermore, projecting

onto the scattering direction provides

in that direction. The latter represents the optimal transverse MTE; the ability to attain it is desirable for solar sailing missions where a large radiation pressure component of force perpendicular to the sun line allows a lightsail to spiral toward or away from the sun [

9]. If a bundle of rays of combined power

all participate identically in the scattering process then the radiation pressure on the scatterer is given by

. On the other hand, a correction factor is required if for any reason all the rays do not participate, e.g., when a flat solar sail is not sun-facing, reducing its effective cross-section by

where

is the sun incidence angle.

3. Geometric Optics Approximation

Our proposed hybrid diffractive sail, illustrated in

Figure 1 (A), shows light incident from the left at normal incident to the plane of the sail. The sail is comprised of a series of right triangular prisms of base length

and apex angle

. A portion of the beam is reflected from the front facet (blue colored rays in the diagram), and the remainder of the beam is transmitted through the side facet and then out the back face. The fraction of reflected and transmitted beam power is given by the respective ratios

and

, where

is the incident beam power. Expressions for the characteristic front and back “window" widths

and

may be found by defining an effective threshold height

delineating which rays are reflected and which are transmitted:

from which we obtain

Note that the powers and lengths must all be positive, and thus . Also note that equal amounts of power are transmitted and reflected when .

Radiation pressure on the hybrid sail has two sources: the reflected beam and the transmitted beam. At normal incidence

the weighted radiation pressure force may be expressed

where

where use has been made of the following front and back surface angles: Front surface scattering angle

where the law of reflection provides

; Back surface scattering angle

. The transmitted deviation angle

is governed by Snell’s law at the back face:

The internal angle

is governed by refraction through the side facet and internal reflection from the front facet:

where

. A critical condition may exist at the output face where light undergoes total internal reflection, i.e., if

. Solving for the value of

n at the critical condition when

provides

. Calculated values of the back deviation angle

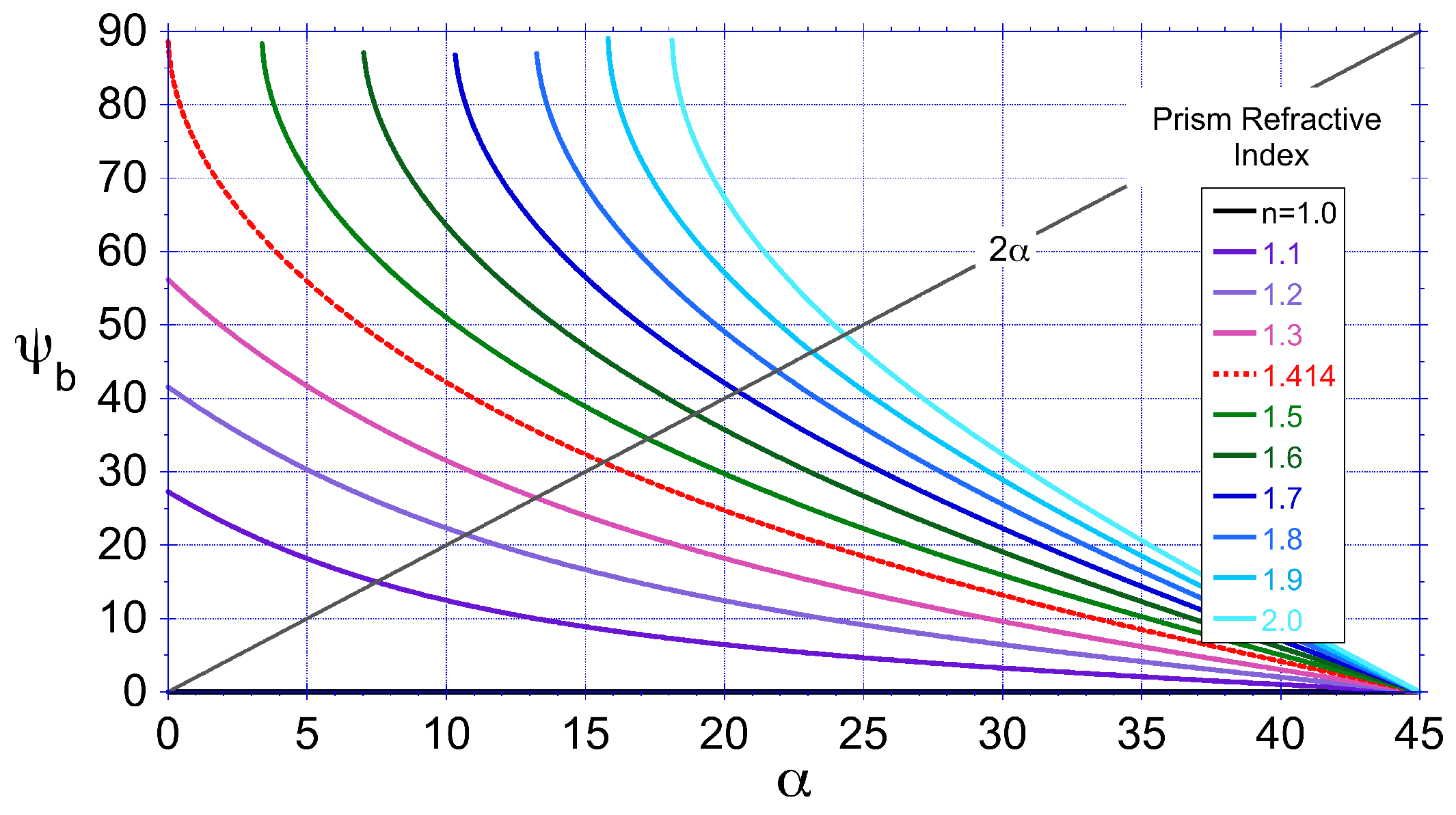

are plotted in

Figure 2, along with the front deviation angle

for comparison.

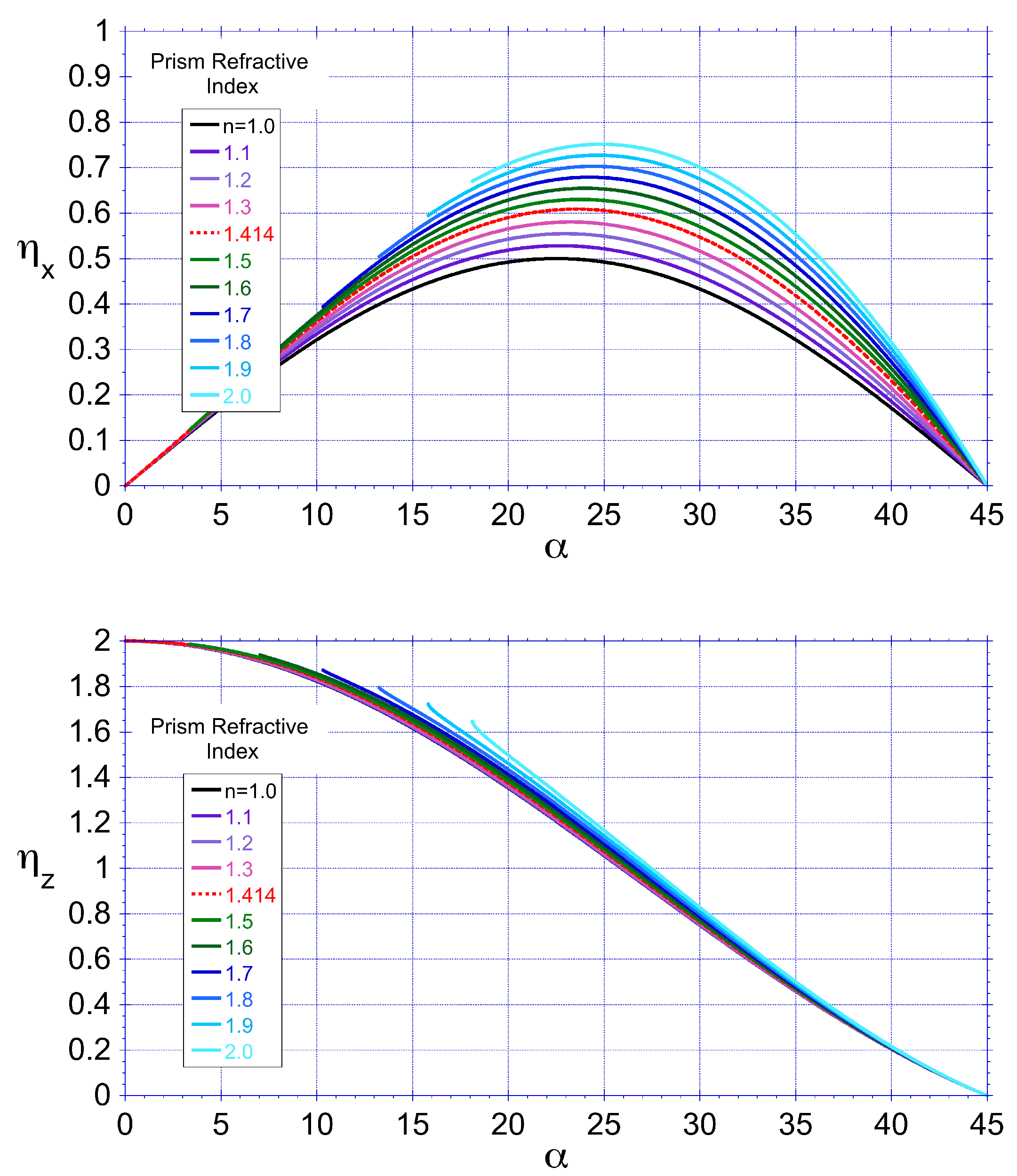

The net transverse and longitudinal components of the momentum transfer efficiencies are therefore

Values of

and

are plotted in

Figure 3 as a function of the apex angle

for different refractive index values. Larger values of refractive index provide larger values of

. For example when

the values

and

at

.

4. Wave Optics Approach

Whereas the foregoing geometric optics analysis describes the direction of light at the front and back faces of the structure, a diffractive wave analysis is required to describe the distribution of light in the far field. First we make use of the Floquet-Bloch theory for a function having period

and wave vector magnitude

:

If

describes a transmission function and

describes an incident planar electric field at

, then the propagating transmitted field in the half space

for the wavelength

may be expressed

where

is the transverse component of the incident wave vector,

is the angle the incident wave subtends the optical axis, and

is the longitudinal component of the propagating field, described below.

The transmission function of the prism grating described above may be approximated by

over a range of length

and zero valued otherwise, where

, and

is the refraction angle found from geometrical optics. Setting the dummy variable

we write

and hence the total propagating field is given by

Hence the field is a superposition of

order components having the phase,

where

. Since the wavelength can not change, the wave vectors magnitudes must all be equal

and thus

The value of must be real for the field to propagate to infinity, and thus m can only assume the values satisfying .

If we equate the

component of

to a single term:

then we obtain the so-called grating equation:

The irradiance of the

order plane wave described by Equation (

11b) is given by

The intensity is a maximum for the value of

m that best satisfies

, i.e.,

The same formalism can be applied to the optical field reflected from the front facet by replacing with the front deviation angle , with , and by changing the sign of .

Although a simple closed form expression for

does not generally exist, one may expect stronger scattering at angles that satisfy either the law of reflection for reflected light, or Snell’s law for the transmitted light, especially in the geometric optic limit

(see

Section 5).

For a light source having the spectral irradiance distribution

the momentum transfer efficiency of the transmitted light can be estimated from diffraction theory. Integration over frequency

where

c is the speed of light is adopted instead of integration over wavelength because the former provides equal sampling intervals across the diffraction orders.

where

,

,

,

,

, and

. The extremum mode values are given by

and

, where INT is the operation that returns the integer value of the argument, rounded toward zero.

For front surface reflections at the deviation angle

where

,

,

,

,

, and

.

A factor of

must be in included in Equations (

16) and (

17) in the event the light source overfills the sail, as occurs in space. In the laboratory, the light source may be a small pencil of light that underfills the sail and thus does not acquire the

projection factor. At normal sun incidence

Equations (

16) and (

17) may be expressed

where

. Note that these equations do not account for effects such as polarization and internal reflections.

Section 6 will address such issues.

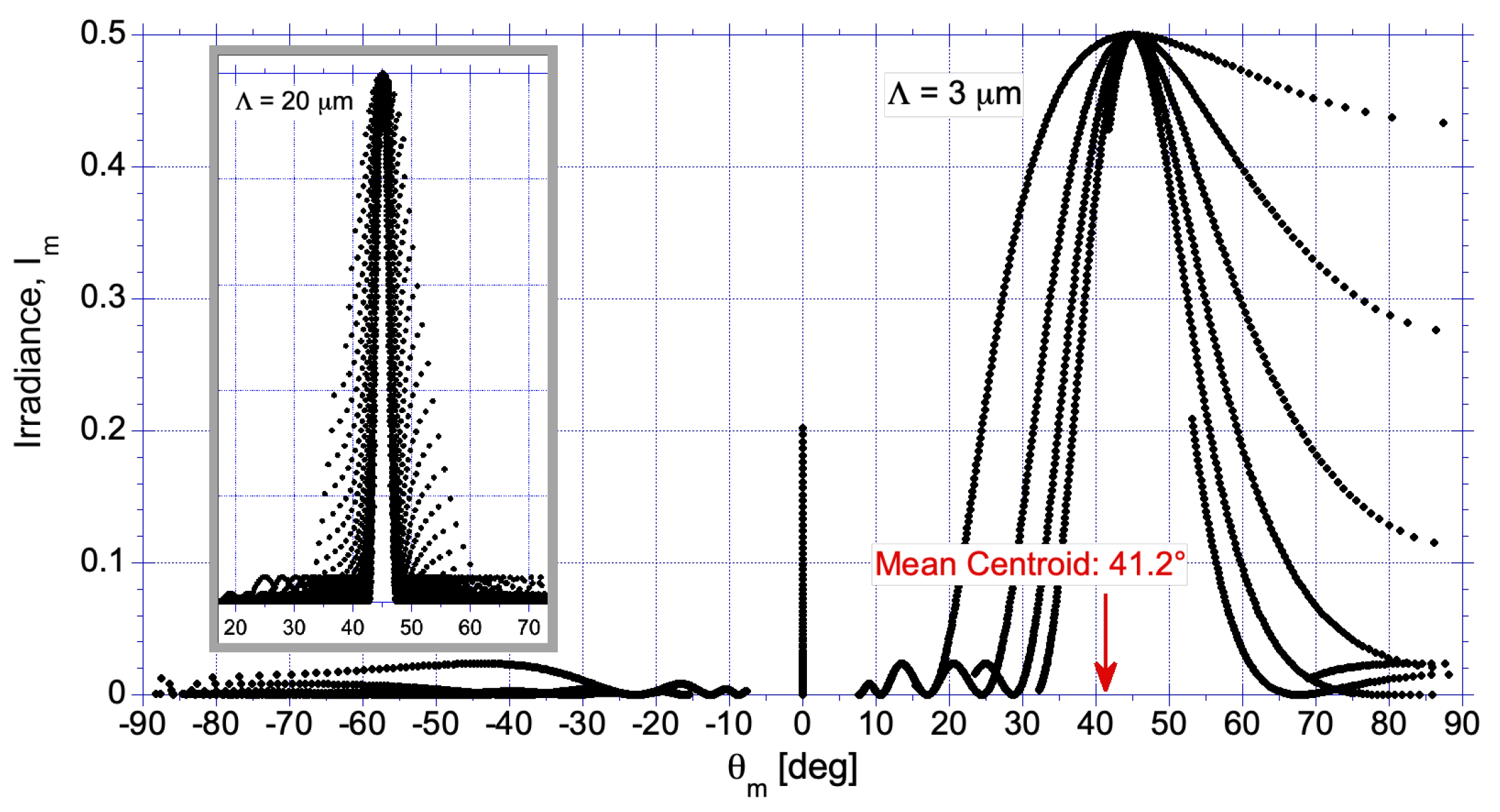

5. Wave - Ray Comparison

Let us briefly compare the ray and wave optics predictions for

, which allows a solar sail to propel toward or away from the sun via a spiral trajetory. We expect the two approaches to agree in the small wavelength limit,

. A more complete description is provided in the next section. In the case of normal sun incidence

and refractive index

, the transmitted rays are undeviated

. Therefore the MTE is solely attributed to front surface reflections. To make use of the above diffractive analysis we simply replace

with

. For example, the ray optic analysis predicts a peak value of

at

, resulting from the product of

and the sine of the deviation angle

; whence

. For comparison a scatter plot of the angular distribution of diffracted modal intensities for a grating of period

and wavelengths ranging from

is shown in

Figure 4. As expected from diffraction theory, the peak modal intensity agrees with

. Although this peak appears at

, the mean centroid is slightly lower

owing to the diffractive cut-off at

. The net transverse MTE is

, a loss of efficiency compared to the geometric optics value of

. The inset in

Figure 4 depicts the narrowing of the angular distribution when the period greatly exceeds the wavelengths of the light source (e.g., when

), in which case the two models agree.

We expect the deviation angle of the transmitted rays to be greater than zero when and thus the net transverse MTE is predicted to increase.

6. Maxwell Stress Tensor Numerical Analysis

To account for the effects of polarization-dependent Fresnel reflections and multiple internal reflections within the hybrid structure, a model that satisfies Maxwell’s equations is required. Although this approach does not provide tractable closed forms solutions, numerical open source and commercial software packages are readily available [

22,

23,

24]. Another approach involves a rigorously coupled wave analysis [

25]. These packages typically compute radiation pressure from the Maxwell stress tensor (MST) which represents the momentum flux density of the electromagnetic field:

where

and

are the permittivity and permeability of free space respectively,

is the Kronecker delta function, and

and

are the electric and magnetic field amplitudes respectively for the

s and

p polarized component of light at the optical frequency

, with indexes corresponding to cartesian coordinates

and

. The components of force in the

x and

z directions may be found by integrating over a close surface

S. For a infinite periodic grating the net momentum flux into a unit cell of length

from the two adjacent unit cells must cancel. Thus it suffices to integrate over a front surface in the

direction and back surface in the

direction over one unit cell of area

. The total area of the sail may be expressed

where

and

are the side lengths of a rectangular sail, and

and

. At a given optical frequency

the components of force on a single cell of area

may be expressed

These expressions can be calculated by Maxwell solvers such as MEEP. For example, Srivastava [

26] showed using MEEP that a low-refractive-index metasurface grating produces a larger transverse radiation pressure force compared to gratings comprised of silicon nitride. For

s-polarized light (TE) the electric field is perpendicular to the plane of incidence:

, whereas for

p-polarized light (TM) the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of incidence:

. Thus the stress tensors needed for the radiation pressure on the grating may be expressed

It is important to note that MEEP calculates the MST at a given frequency for a unit irradiance, (i.e., not for an arbitrary value consistent with the spectral irradiance of the light source). Thus, for given spectral irradiance distributions

the net components of force are found by integration over all frequencies:

For unpolarized light

. For example the solar irradiance incident on the Earth may be approximated by the blackbody frequency spectral irradiance distribution:

where

[m] is solar radius,

[m],

[J· s] is the Planck constant,

c is the speed of light, and

[J/K] is the Boltzmann constant. We let

[K] as the effective surface temperature of the sun whereupon integrating over all frequencies provides the so-called solar constant

[W/m

2]. Thus for a light sail orbiting at the semi-major axis of the Earth, the force on each element of area

at normal sun incidence is given by

The components of the MTE are then found by dividing by the characteristic force magnitude

:

Note that MEEP is unable to account for the illumination projection factor in the event the illumination source overfills the sail area, in which case must be replaced by .

It is not practical to determine the MST across all frequencies in MEEP, as computational resource demands and computing times becomes unwieldy when

. For this reason we limit the integration from an arbitrary minimum frequency somewhat below the diffractive cut-off condition,

, to an arbitrary upper value

. Unless stated otherwise, a normal sun incidence angle

is assumed, as well as a grating period

, a minimum frequency

, and a maximum frequency

corresponding to

. This range of frequencies encompasses 75% of the solar frequency spectrum as illustrated in

Figure 5 (right).

In the geometric optics model described in

Section 3 for the case where the prism refractive index was unity, the peak value of

was found at the prism angle

(see

Figure 3). Larger peak values of

were predicted for larger value of

n, in which case the value of

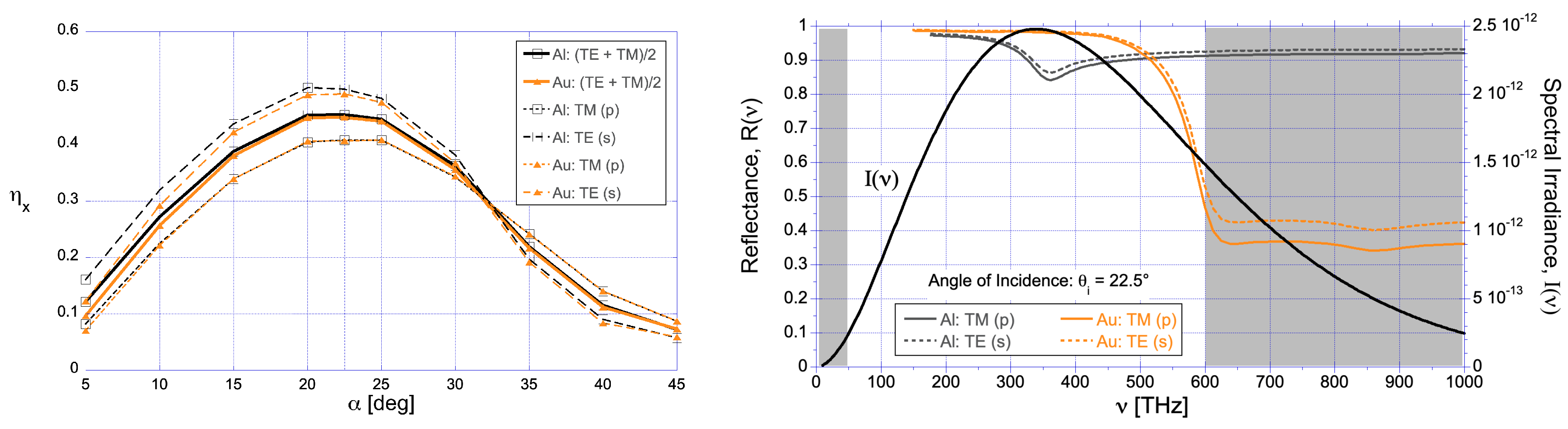

was marginally larger. Using MEEP to calculate

across the frequency range 50-600 THz, and making use of the complex refractive index values of gold and aluminum, we found similar results for a prism index of

. The front facet was metallized with

thick coating. The calculated variation of

vs.

is plotted in

Figure 5 (left). The spectral reflectance curves plotted in

Figure 5 (right) illustrate the general trend for metals, e.g., the

s-polarized field (which is tangential to the interface) is more strongly reflected than the

p-polarized field (which has a component normal to the interface). The higher reflection values are expected to provide larger values of

. The average (unpolarized) value peaks at

at

.

The polarization-averaged differences between aluminum and gold are negligible and the choice of material depends on other concerns such as mass density, spectral bandwidth, and space weathering. The low reflectance of gold at wavelengths shorter than (above 600 THz) is also a concern. A comparison of the values of for the numerical MST analysis and the geometric optics analysis shows a smaller value in the former case, which we attribute to p-polarized light.

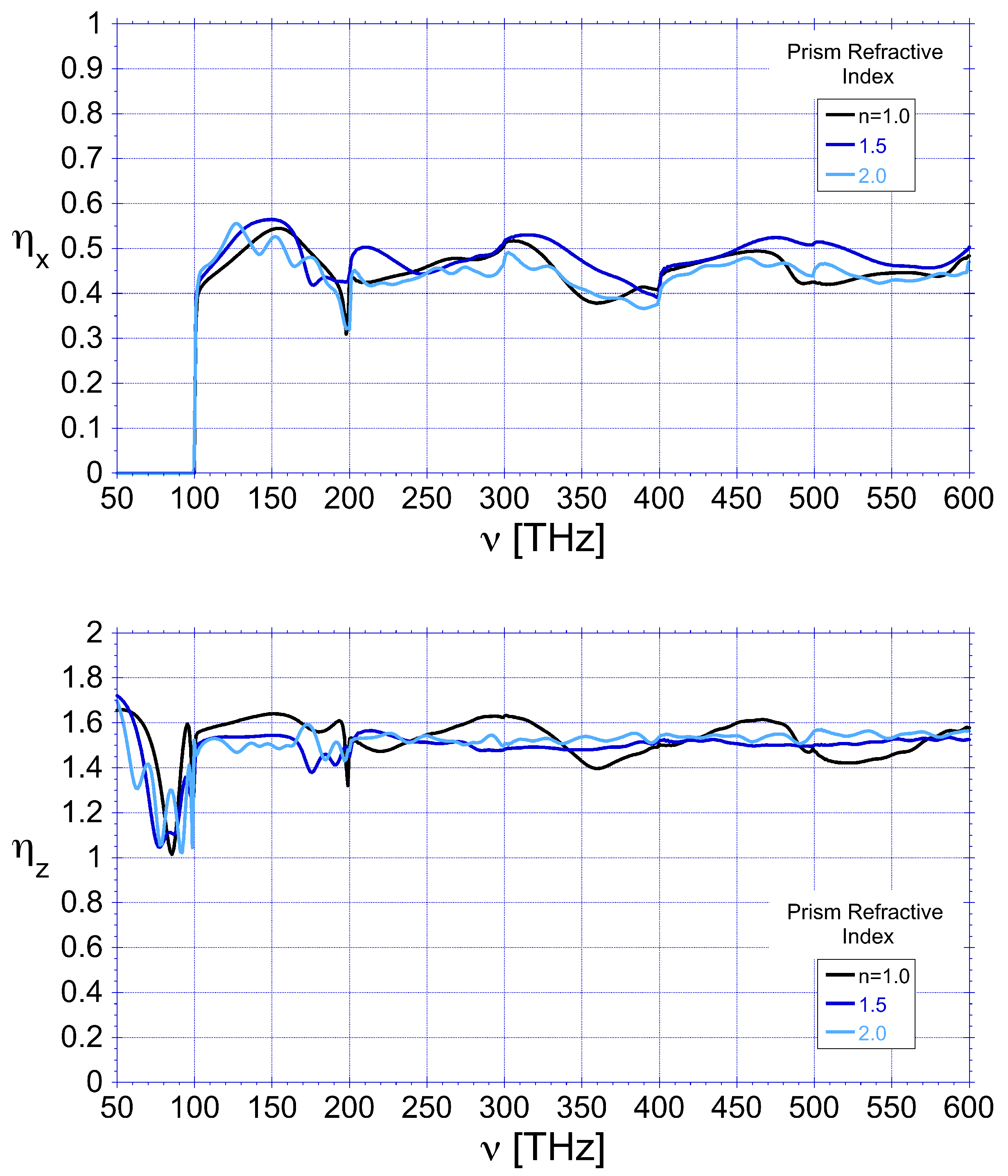

The geometric optics model also predicted that for a given value of

, the value of

increases with increasing refractive index (see

Figure 3). Let us compare this prediction with the MEEP model. The polarization averaged spectral distributions for aluminum are plotted in

Figure 6 for three different prism refractive index values,

, resulting in the corresponding frequency-integrated values

,

,

, and

,

,

The grating period

corresponds to a fundamental frequency

THz which corresponds to the diffractive cut-off frequency. Evidence of strong diffractive effects at multiples of

is evident in

Figure 6.

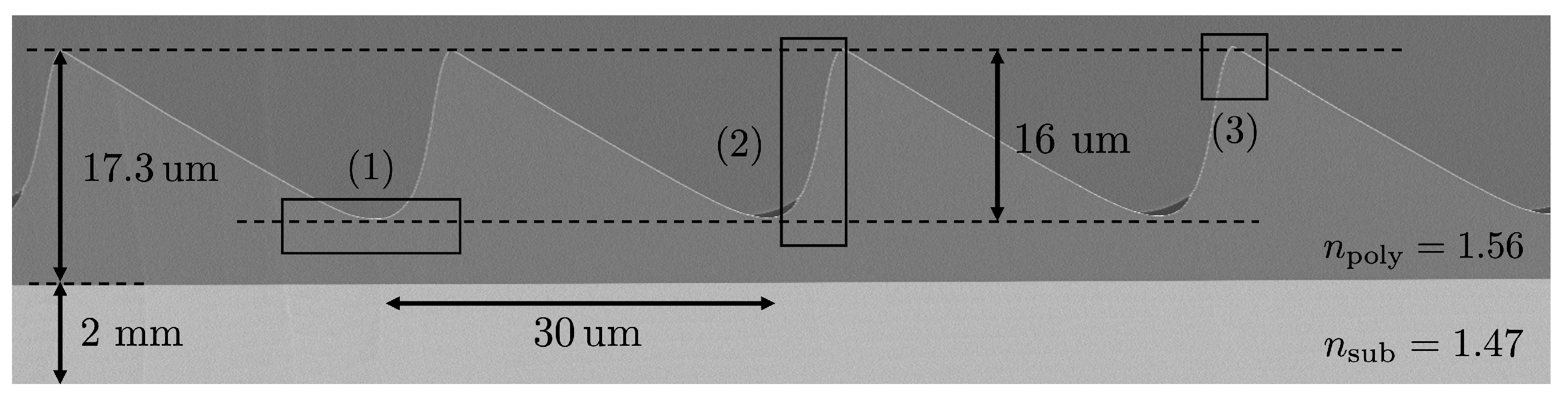

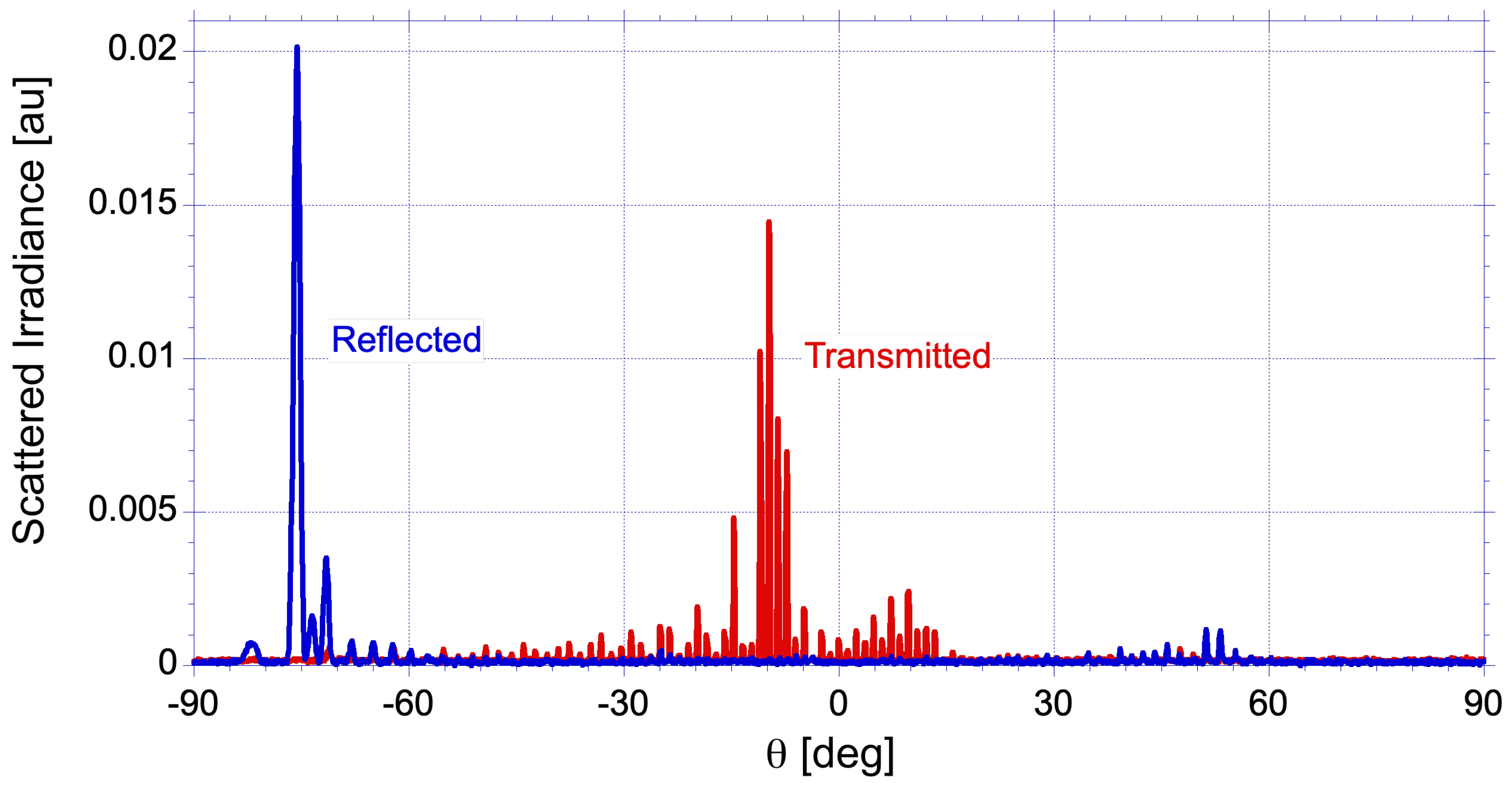

9. Hybrid Grating Fabrication and Verification

To help assess the veracity of the above calculations direct-write grayscale lithography (DWL) was used to fabricated a hybrid grating comprised of a low index polymer via a polymer replication process. This technique is suitable for long period structures (compared to visible wavelengths) and may therefore be expected to agree with the high optical frequency results from our MEEP simulations. To provide structural stiffness the polymer grating (

= 1.56) was applied to a 2 mm thick boro-float substrate (

= 1.47). The long slanted facet of the grating was coated with 70 nm of aluminum using physical vapor deposition, leaving the shorter side facet uncoated. An scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a replicated hybrid grating, depicted in

Figure 8, indicates rounded features owing to the fabrication process. To lessen the degree of non-ideal scattering from the rounded regions we elected to produce a grating of period

, height

, and prism angle

. The angular scattering distribution shown in

Figure 9 was measured with a purpose-built in-house scatterometer at the HeNe laser wavelength

[nm]. As many as

diffraction orders are expected on each side of the optical axis.

The scattering data was used to calculate the theoretically expected momentum transfer efficiencies:

where

is the scattered HeNe beam power and the irradiance values have been adjusted for bias and gain:

where

is the sum of the average value of

in the range

and one standard deviation,

is the sum of the average value of

in the range

and one standard deviation,

is the estimated relative gain factor of the two measurements, and the STEP function sets negative values to zero. The corresponding high optical frequency MEEP values are

and

. The measured and calculated values of

are in good agreement. The discrepancy between the values of

may be attributed less back-reflection from the fabricated structure.

10. Conclusions

We examined a hybrid reflection/transmission grating comprised of metallized front facing facets and transmissive side facing facets as shown in

Figure 1 for solar sailing missions requiring spiral trajectories toward (or away from) the sun. The hybrid grating is designed to reduce the effects of undesired scattering from the side facets while maintaining a sun-facing orientation. We compared the radiation pressure force efficiency on the grating using geometric optics approximations and numerical finite difference time domain methods. Additionally, a prototype hybrid grating was fabricated to verify the momentum transfer efficiency predicted in the geometric and numerical studies.

Making use of the Maxwell solver MEEP we computed the momentum transfer efficiency of a hybrid grating of period

and apex angle

, finding the net transverse MTE in a sun facing configuration reaches

when the refractive index of the sail material is 1.5. At optical frequencies beyond our upper computational range of 600 THz (i.e., shorter than

) a geometrical optics limit (where diffraction effects become increasingly negligible) is expected whereupon the MTE becomes weakly independent of wavelength (for example, owing to material dispersion). However, the geometrical optics model presented in

Section 3 is insufficient for computing this limit as it does not account for Fresnel reflection and transmission coefficients at the interface between vacuum and the substrate. Nevertheless, the geometrical optics value of

when

(i.e., no dielectric boundary) is in remarkably good agreement with the Maxwell solver value of

. What is more, a hybrid grating designed for the geometrical optics range (with period

much greater than the wavelength

) was found to have an angular scattering distribution in excellent agreement with our predicted value of

47% vs 48%. Finally, our numerical model found no significant difference between the use of gold and aluminum for the reflective coating. Aluminum may be preferable, however, owing to absorption in gold beyond 600 THz.

Figure 1.

(A) Near-field geometric optics diagram of a hybrid gratings of height h, period , refractive index n (gray), reflective surface (black), and apex angle depicting reflected (blue lines) and transmitted (red lines) rays. Normal incidence upon the grating plane is assumed. The angles and are the respective front and back surface ray deviation angles. (B) Diffraction grating of period with incident and -order reflected and transmitted wave vectors, , , and making angles , , and respectively. The z and x axes are normal and tangential to the plane of the grating. Diffraction is attributed to the addition of integer multiples of the grating momentum where .

Figure 1.

(A) Near-field geometric optics diagram of a hybrid gratings of height h, period , refractive index n (gray), reflective surface (black), and apex angle depicting reflected (blue lines) and transmitted (red lines) rays. Normal incidence upon the grating plane is assumed. The angles and are the respective front and back surface ray deviation angles. (B) Diffraction grating of period with incident and -order reflected and transmitted wave vectors, , , and making angles , , and respectively. The z and x axes are normal and tangential to the plane of the grating. Diffraction is attributed to the addition of integer multiples of the grating momentum where .

Figure 2.

Back deviation angle as a function of prism apex angle for different values of the prism refractive index n. The front deviation angle is shown for comparison. For a critical condition may exist at some values of where is undefined. When rays exit the back surface undeviated.

Figure 2.

Back deviation angle as a function of prism apex angle for different values of the prism refractive index n. The front deviation angle is shown for comparison. For a critical condition may exist at some values of where is undefined. When rays exit the back surface undeviated.

Figure 3.

Geometric optics estimates of the net transverse (top) and longitudinal (bottom) momentum transfer efficiencies, and respectively, for different values of the prism apex angle and refractive index n. Values not shown when total internal reflection occurs at the output face.

Figure 3.

Geometric optics estimates of the net transverse (top) and longitudinal (bottom) momentum transfer efficiencies, and respectively, for different values of the prism apex angle and refractive index n. Values not shown when total internal reflection occurs at the output face.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of the angular spectrum of diffracted modes across a band of wavelengths , assuming reflection from the front facet of a prism of apex angle , period , window width and a deviation angle of . Inset depicts quasi-geometric regime for the same conditions, except .

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of the angular spectrum of diffracted modes across a band of wavelengths , assuming reflection from the front facet of a prism of apex angle , period , window width and a deviation angle of . Inset depicts quasi-geometric regime for the same conditions, except .

Figure 5.

Left: Polarization dependent net transverse radiation pressure force efficiency for a hybrid grating of

m] and varying prism angle

. Dark gray (Orange) curves represent a hybrid grating coated with aluminum (gold). Values are frequency averaged across the range 100 THz to 600 THz. Right: Vacuum spectral reflectance calculated from tabulated values of the complex refractive index for aluminum and gold, assuming an incidence angle of

([

27]). Solar blackbody irradiance spectrum also shown in units of [W m

−2 Hz

−1] for

[K].

Figure 5.

Left: Polarization dependent net transverse radiation pressure force efficiency for a hybrid grating of

m] and varying prism angle

. Dark gray (Orange) curves represent a hybrid grating coated with aluminum (gold). Values are frequency averaged across the range 100 THz to 600 THz. Right: Vacuum spectral reflectance calculated from tabulated values of the complex refractive index for aluminum and gold, assuming an incidence angle of

([

27]). Solar blackbody irradiance spectrum also shown in units of [W m

−2 Hz

−1] for

[K].

Figure 6.

Spectral momentum transfer efficiency values (Equation (

Section 6) ) for three values of refractive index,

n, assuming a grating period

and an aluminum coating.

(top),

(bottom).

Figure 6.

Spectral momentum transfer efficiency values (Equation (

Section 6) ) for three values of refractive index,

n, assuming a grating period

and an aluminum coating.

(top),

(bottom).

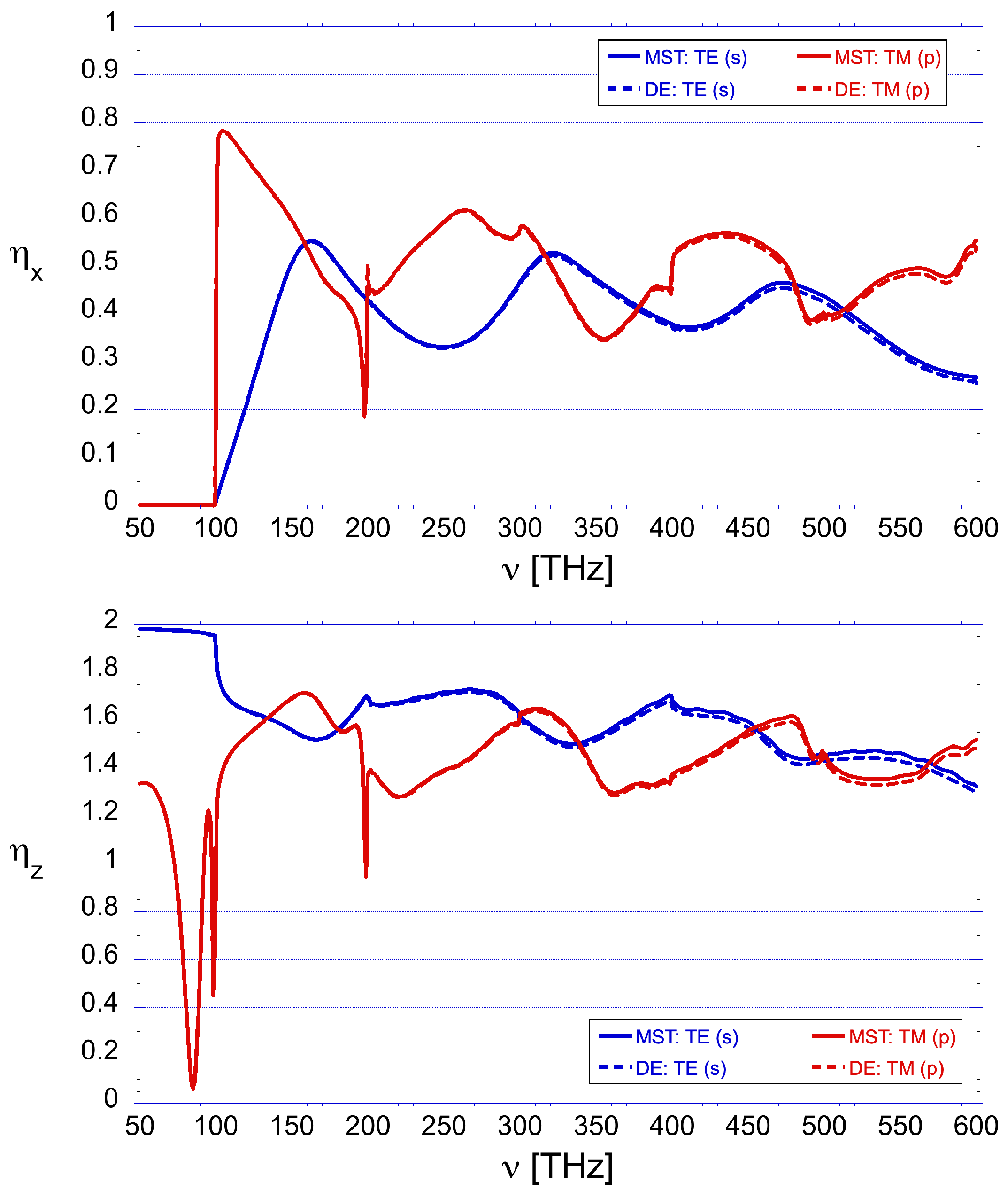

Figure 7.

Polarization dependent spectral radiation momentum transfer efficiencies for a hybrid grating of period and substrate refractive index . Solid line: Maxwell stress tensor method. Dashed line: Modal numerical analysis. Additional diffraction orders are added at integer multiples of the first order cut-off frequency, THz.

Figure 7.

Polarization dependent spectral radiation momentum transfer efficiencies for a hybrid grating of period and substrate refractive index . Solid line: Maxwell stress tensor method. Dashed line: Modal numerical analysis. Additional diffraction orders are added at integer multiples of the first order cut-off frequency, THz.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the profile of the fabricated hybrid grating. Undesirable fabrication features are shown in boxed regions. (1) Rounding of the troughs; (2) rounding of the side facets; and (3) rounding of the top vertex of the prisms. These features lead to discrepancies in the designed and fabricated grating period and influence the transverse momentum transfer efficiency.

Figure 8.

SEM image of the profile of the fabricated hybrid grating. Undesirable fabrication features are shown in boxed regions. (1) Rounding of the troughs; (2) rounding of the side facets; and (3) rounding of the top vertex of the prisms. These features lead to discrepancies in the designed and fabricated grating period and influence the transverse momentum transfer efficiency.

Figure 9.

Reflected (top) and transmitted (bottom) scattering angles for a hybrid grating of m] and .

Figure 9.

Reflected (top) and transmitted (bottom) scattering angles for a hybrid grating of m] and .