1. Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by atypical social communication, restricted and repetitive behaviours, focused interests and distinct sensory processing. Cognitive functioning in autistic individuals vary from intellectual disability to high intelligence. These traits typically emerge in early childhood by 24 months of age and exhibit substantial heterogeneity in both presentation and intensity across individuals [

1]. As of 2021, autism ranked among the top 10 non-fatal health conditions of individuals under 20 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 61.8 million people worldwide [

2]. Its complex aetiology includes genetic, epigenetic, environmental, and immune factors, with heritability estimates of 60-90%[

3,

4]. Neuroimaging, especially Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), has become central in research of brain structure and function in autism.

Structural MRI enables detailed assessment of cortical thickness, gray matter volume, and brain morphology, revealing differences in regions associated with social cognition, communication, and sensory processing. These differences affect multiple brain regions such as the hippocampus, basal ganglia, cerebellum and thalamus rather than being confined to a specific localized area [

5]. Other findings include early brain overgrowth, and altered gyrification patterns [

6,

7]. Functional MRI (fMRI), especially resting-state fMRI reveals disrupted connectivity in brain networks like the default mode network (DMN), with increased local connectivity in children and decreased long-range coherence in adults.[

8]. Diffusion MRI and DTI show atypical white matter connectivity, especially reductions in long-range tracts affecting the DMN and other cognitive networks reinforcing the concept that autism involves widespread network-level disruptions rather than isolated regional abnormalities [

9]. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) studies have reported neurotransmitter imbalances, such as in GABA and glutamate levels [

10].

Despite these technological advancements, no single neuroimaging or biological marker has been validated for the definitive diagnosis of autism. Formal diagnosis remains reliant on behavioural criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) with the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS 2) -a standardized series of tasks and social interactions designed to observe communication and repetitive behaviours- [

11] and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)[

12], -a structured caregiver interview that gathers developmental history and symptom patterns- being considered the gold standard diagnostic instruments. Increasing criticism has also been directed toward deficit-based diagnostic frameworks, which are often inconsistent with the neurodiversity paradigm that conceptualizes autism as a natural variation in cognitive functioning [

13,

14]. The variability in symptomatology and neurobiological underpinnings complicates the development of a universal biomarker and supports the view of autism as a constellation of phenotypes rather than a singular entity [

15].

Given these limitations of current diagnostic approaches which are time consuming, clinician-dependent, and structured with deficit-based behavioural criteria, there is increasing interest in objective, biologically grounded tools capable of capturing the neurodevelopmental heterogeneity of autism. In this context, quantitative MRI offers a means to detect reproducible brain-based differences in structure, connectivity, and neurochemistry, yet interpreting high-dimensional imaging data remains a challenge. Among the earliest quantitative approaches, voxel-based morphometry (VBM) provided voxel-wise assessments of gray matter volume and has been applied in some machine learning studies for autism. More recently, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems have emerged as promising approaches for detecting subtle, distributed neurobiological patterns from MRI data that may align with phenotypic variability within the autism spectrum [

16,

17].

A notable advancement in this area is the emergence of radiomics, an application of advanced computational techniques which converts standard MRI scans into large sets of quantitative descriptors that capture tissue texture, shape, and spatial complexity [

18]. Traditionally, this involves handcrafted features such as first-order statistics (i.e., intensity-based metrics), shape descriptors, and texture patterns derived from methods like the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and gray-level-run-length-matrix (GLRLM) [

19]. In more recent publications, the scope of radiomics seems to have expanded to encompass a wider array of quantitative imaging biomarkers. Notably, features extracted from advanced MRI techniques such as Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) for brain iron content [

20],Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) from arterial spin labelling (ASL)[

21] and Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging (DKI) metrics (i.e., mean kurtosis, radial kurtosis, mean diffusivity)[

22], are increasingly integrated into radiomics pipelines. While VBM is traditionally a group-wise morphometric tool, several studies have repurposed VBM-derived gray matter maps as high-dimensional features in machine learning pipelines functioning like radiomic descriptors particularly in studies aiming to characterize structural brain phenotypes at a spatial scale[

23]. These imaging biomarkers capture functional activity (CBF), microstructural integrity (diffusion metrics), molecular composition (iron, QMS) and density and morphological properties of tissue (VBM), offering complementary information to conventional structural descriptors, reflecting a conceptual shift toward comprehensive quantitative imaging.

Machine learning algorithms have been proven to be powerful tools for pattern recognition and classification using high-dimensional quantitative imaging data as input. In parallel, Deep learning (DL) models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformer-based architectures, have enabled automatic feature learning directly from raw neuroimaging data, bypassing the need for handcrafted inputs and manual bias. When applied to radiomic or raw MRI data (structural, diffusion and/or functional), these models have demonstrated promising performance in distinguishing autistic from non-autistic groups, and in some cases identifying subgroups within the spectrum [

24]. These methods may reduce diagnostic delays by offering scalable, data-driven, and less subjective diagnostic support -an especially critical goal, given the importance of early intervention in autism where timely support can significantly influence developmental trajectories [

25].

1.1. Related Work

Previous systematic reviews have assessed the role of artificial intelligence in autism classification, yet few have addressed the comparative performance of radiomics and deep learning. For example, the authors of this study [

26] evaluate the diagnostic performance of 134 MRI-based machine and deep learning methods for identifying autism, with a focus on sensitivity, specificity and heterogeneity across studies using different MRI modalities but do not analyse ML-DL separately.

Machine learning applications to MRI have been reviewed in this study [

27], highlighting improved diagnostic performance in structural compared to functional modalities and noting methodological heterogeneity with focus on machine learning without differentiation between deep learning architectures. Another study [

28] focused on deep learning applied only to resting-state fMRI and reported consistently high classification accuracy across architectures while others [

29] briefly reviewed AI-based imaging tools for early autism detection, referencing both radiomics and DL but without a direct comparison. That review also addressed the types of imaging markers associated with autism and the relevance of parcellation strategies. This study [

30] focused on the application of deep learning techniques for the automatic diagnosis and rehabilitation of autism. It is also discussed how DL models like CNNs and autoencoders have been used to automatically extract and classify features, often outperforming traditional ML approaches while the authors of this study [

31] reviewed the use of vision transformer architectures for autism classification from neuroimaging data, highlighting their potential to capture distributed neural patterns more effectively than traditional CNNs.

Despite increasing interest in AI-based neuroimaging for autism, the authors are not aware of prior review systematically comparing radiomics, deep learning and hybrid (radiomics used in deep learning) models in terms of methodology, performance, interpretability, and modality-specific application. A comparison of these approaches could be beneficial because previous reviews have focused on radiomics and deep learning in isolation without providing a cohesive framework for evaluating their relative strengths and limitations, while hybrid models have not been sufficiently highlighted, possibly limiting progress toward clinically applicable AI tools in autism diagnostics. Furthermore, the distribution of these computational approaches across structural, functional, and diffusion MRI has not been thoroughly mapped. Methodological robustness, cohort size, and clinical relevance are also inconsistently reported across studies. This review attempts to address these gaps by providing a structured, modality-stratified comparison of radiomics-based machine learning and deep learning studies in autism classification. In doing so, it aims to offer insights into their respective capabilities and potential as objective, neuroimaging AI-based diagnostic tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

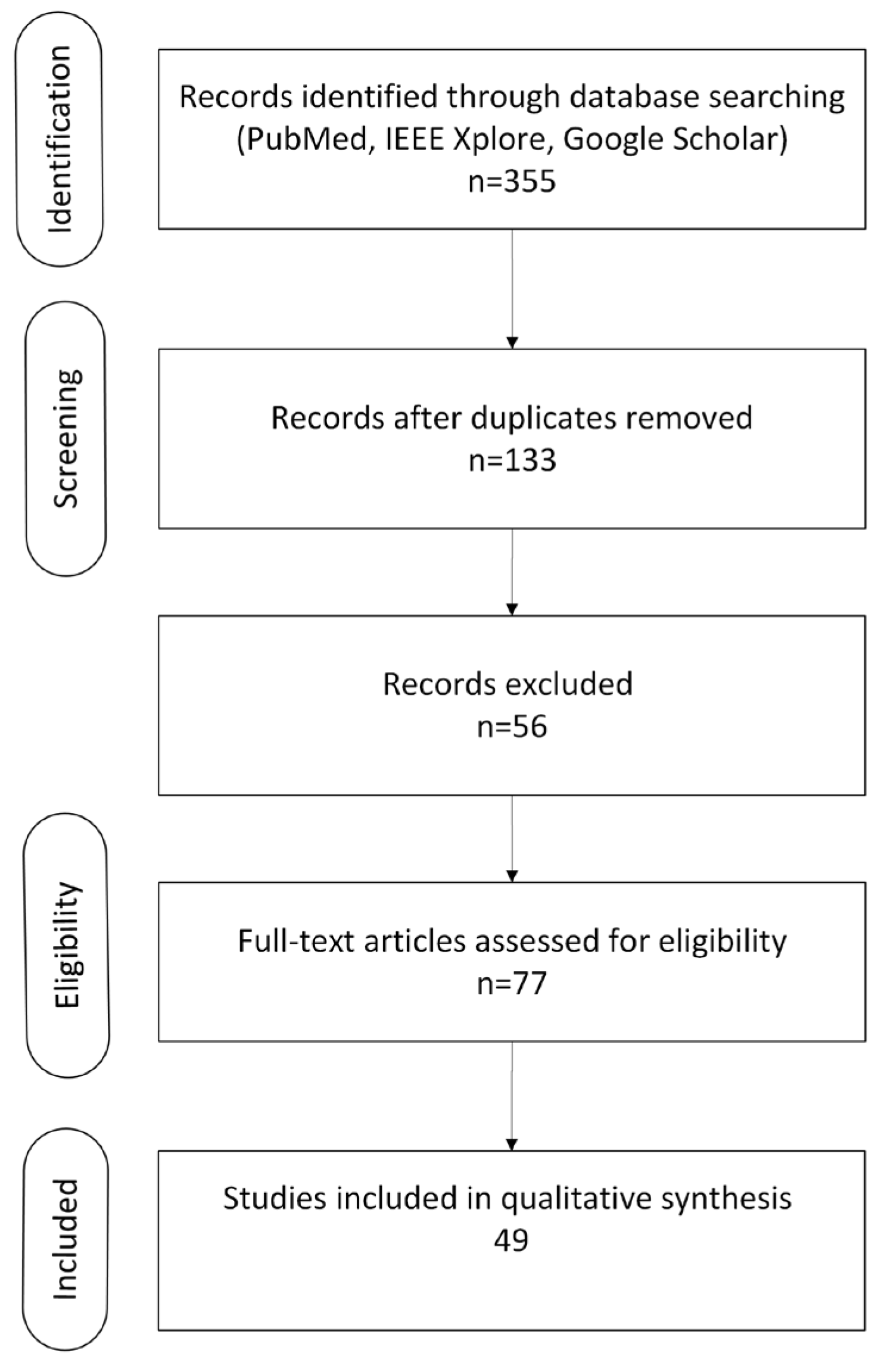

A systematic literature review was conducted across relevant databases (PubMed, IEEE Xplore and Google Scholar) by two reviewers to identify peer-reviewed articles published between 2011 and 2025. The search aimed to capture studies on MRI-based classification of autism using radiomics, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) methods. The search strategy used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text keywords, including: “autism” OR “autism spectrum disorder” OR “autism” “AND” “MRI” OR “magnetic resonance imaging” “AND” “classification” OR “diagnosis” OR “prediction” “AND” “radiomics” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “artificial intelligence”. Filters were applied to include only original articles, conference proceedings, and systematic reviews, and to exclude case reports, non-peer reviewed material, and non-English publications. Additional references were identified through manual screening of relevant bibliographies. The initial database search identified n = 355 unique hits relevant to “autism + MRI+ classification + radiomics/ML/DL”. After removing duplicates n = 222, n =133 records remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, n = 56 were excluded based on irrelevance to MRI, autism, or AI methods. The full texts of 77 articles were assessed for eligibility, resulting in the exclusion of 28 studies due to insufficient methodological detail, lack of quantitative data, or not meeting inclusion criteria, resulting in the inclusion of a total of 49 studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

2.2.1. Overview of Included Studies

A total of 49 studies were included in this systematic review, published between 2011 and 2025, all investigating MRI-based classification of autism using computational approaches of radiomics-based machine learning and deep learning. Publicly available datasets, especially ABIDE I and II either in full or subsets, were frequently used, and several studies also used institutional or locally acquired cohorts. Sample sizes ranged from small single-site cohorts (n<50) to large multi-center datasets exceeding 1,000 participants. The studies included in this review investigated autism across a broad age range, from 2 to 57 years. The majority (~82%) of the studies focused on pediatric and adolescent populations (ages 2-18), reflecting the clinical emphasis on early diagnosis of autism. A smaller proportion (~10-15%) involved adult-only cohorts, while a few studies examined mixed-age or lifespan samples. However, in many cases, age-specific results were not reported, and some used datasets with mixed age groups without stratification. Classification performances varied, with reported accuracies typically ranging between 70% and 95%, depending on the modeling approach, data source, and validation design. The methodologies employed span a diverse range of analytical strategies, including 27 studies utilizing deep learning (DL) architectures, 19 studies based on radiomics or traditional machine learning (ML) pipelines, and a smaller subset of 3 studies comprising hybrid models of deep learning and radiomics combined.

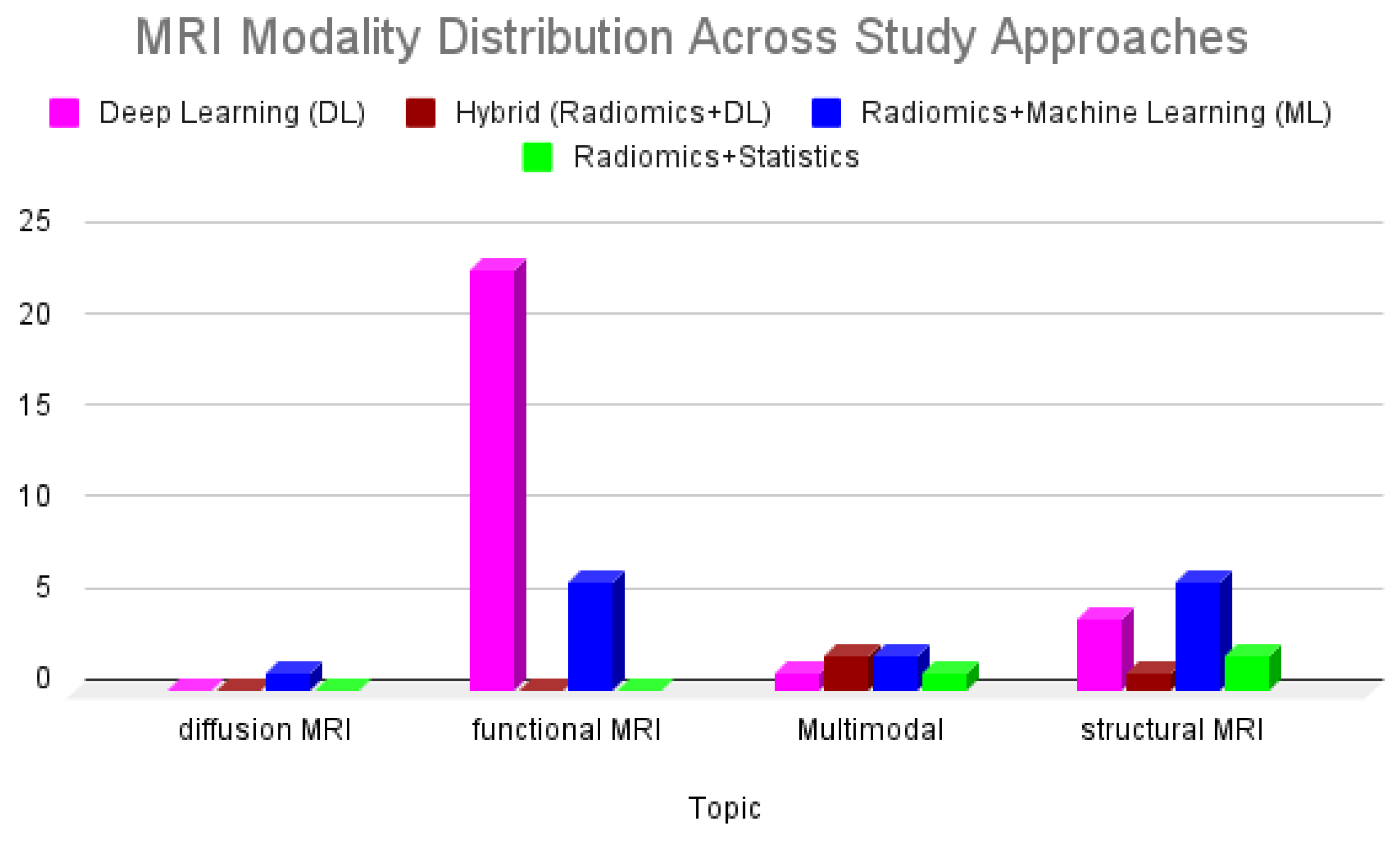

The MRI modalities examined across these studies include structural MRI (sMRI), predominantly T1-weighted sequences; functional MRI (fMRI), primarily resting-state (rs-fMRI); and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI/DTI), which was less commonly used. Radiomics and handcrafted feature-based studies primarily relied on structural MRI to extract morphometric or texture-based features, while deep learning studies often leveraged functional data to model complex brain connectivity patterns.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of MRI modalities used across these methodological approaches. Functional MRI was the most used modality in deep learning studies, whereas structural MRI was more frequently employed in radiomics-based approaches. Hybrid models and multimodal pipelines remain limited. Radiomics combined with statistical analysis appeared earlier and only in structural MRI studies and remain steady but less dominant in the literature. In contrast, deep learning applied to functional MRI shows a rise in publication frequency after 2018, peaking in 2020. Hybrid models combining radiomics with deep learning remain limited, with only sparse representation in recent years.

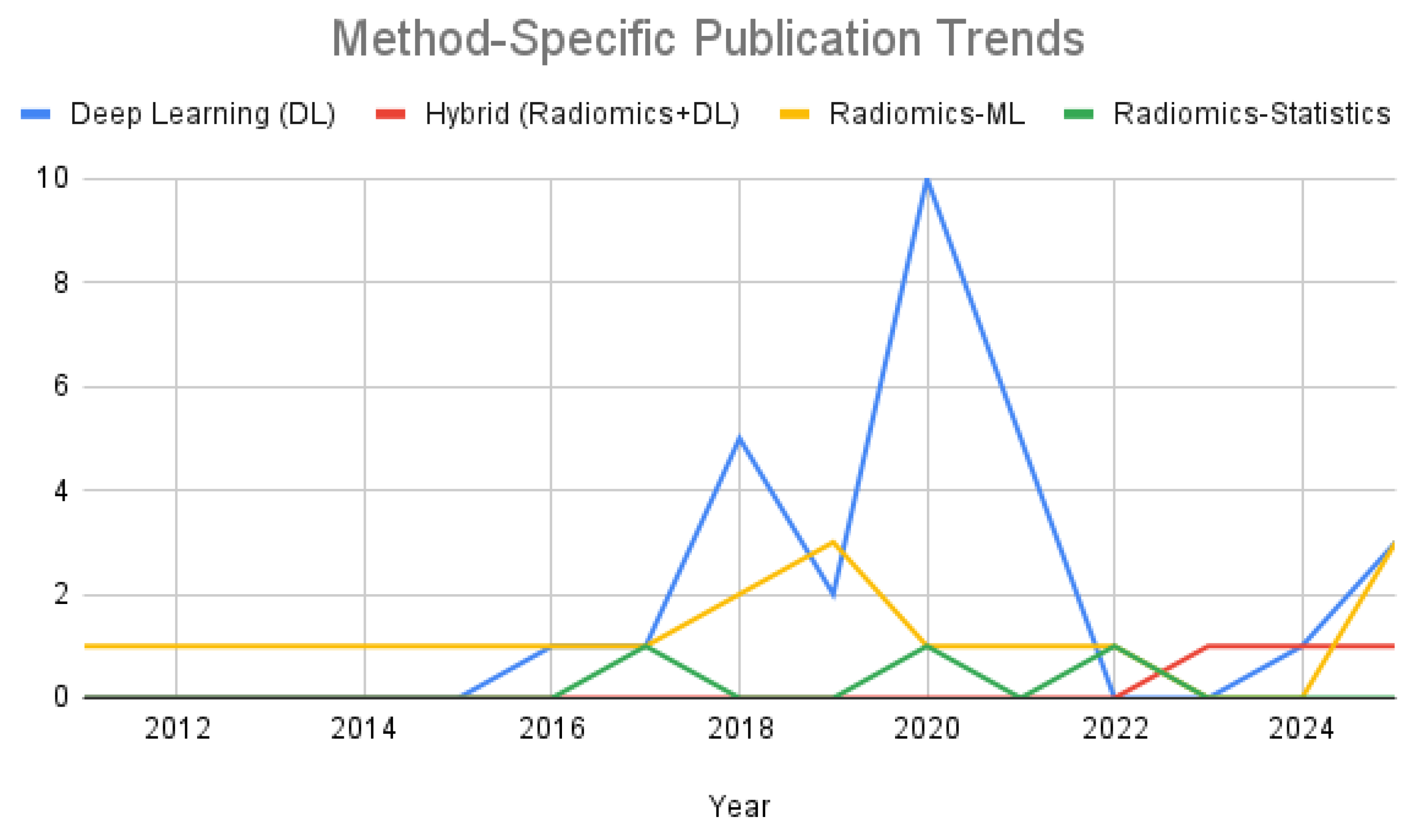

Figure 3 presents a heatmap of the temporal distribution of included studies by MRI modality and analytical method. The temporal pattern presents highlights a shift in focus from handcrafted to automatically learned features, as deep learning gained traction due to applications of it being enabled from the advancements in computing hardware.

Figure 4 further emphasizes this trend through a line graph of method-specific publication frequency. Deep learning approaches exhibit a sharp rise beginning in 2018, reflecting growing interest in data driven feature extraction for autism classification. Meanwhile, radiomics machine learning studies maintained a modest but consistent presence. Hybrid approaches emerged only after 2020, indicating a preliminary but evolving direction in the field. Radiomics combined with solely univariate statistical analysis remained marginal throughout the studied period.

2.2.2. Preprocessing and Modelling Approaches

Preprocessing and feature extraction are critical steps in MRI-based texture analysis aiming for classification using machine learning. These steps shape the quality of the input data but also influence the reliability and generalizability of the analysis. Studies in this domain typically rely on structural MRI data, and differ in how they handle scanner variability, subject demographics and feature selection strategies. Below is presented the preprocessing methodology and modelling approach of selected studies of this review.

Table 1 presents the main differences between radiomics, deep learning and hybrid approaches.

2.2.3. Radiomics-Based Studies

The authors in this study [

32] used ABIDE-I data (1,100 subjects, 20 sites) with standard preprocessing and Desikan-Killiany parcellation. A Random Forest model with 3-fold cross-validation achieved varying accuracy across sites (0.70–0.96), suggesting site effects. No harmonization was applied (i.e., ComBat), and the lack of normalization across scanners and acquisition protocols was a key limitation. Feature selection used a genetic algorithm, but demographics and scanning parameters showed no correlation with performance.

A diagnostic model has been also developed [

33] for classifying autism in children aged 18-37 months using structural MRI-derived features from T1-weighted sequences. Cortical parcellation was based on the Desikan-Killiany atlas, and three types of structural features were extracted: regional cortical thickness, surface area, and volume. Cortical thickness was the most predictive feature, outperforming both volume- and surface area-based models. Random Forest (RF) classifier achieved the highest performance (accuracy: 80.9%, AUC: 0.88). Feature importance analysis identified the top 20 cortical regions (e.g., entorhinal cortex, cuneus, paracentral gyrus), which were used to build the optimal RF model.

In this study, [

34] the authors used 64 T1-weighted MRI scans from the ABIDE I database to study radiomic differences in the hippocampus and amygdala. The data consisted of two subsets drawn from different sites to account for age-related and site-related variability. Manual segmentation was performed by two radiologists, ensuring high inter-rater reliability, followed by intensity normalization to 32 gray levels. Gray-level co-occurrence matrices (GLCM) were derived using four directions and a fixed offset, and eleven Haralick features were extracted for each slice. These features were averaged across slices and directions for a robust representation of each region. Z-score normalization was applied to standardize the feature distributions before classification. Feature selection was conducted using ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni correction, followed by classification using support vector machines (SVM) and random forest models. The hippocampus features, particularly GLCM correlation, showed strong discriminative power, while amygdala features were less consistent. No harmonization techniques were applied for scanner differences. Despite the small sample size and reliance on manual segmentation, the approach highlights the potential of radiomic texture analysis for autism classification based on hippocampal microstructural patterns.

The same authors in another study [

35] investigated whether T1-weighted radiomic texture analysis could capture differences in brain tissue associated with autism, sex and age. The preprocessing pipeline followed included standard steps such as skull-stripping, intensity normalization, atlas registration and segmentation into 31 subcortical brain regions. For texture analysis, a Laplacian-of-Gaussian filter (LoG) was applied at the spatial scales to highlight fine, medium, and coarse textures. Within each region, statistical descriptors were calculated (mean, standard deviation and entropy). These features were compared across groups using statistical tests (permutation testing and corrected p-values) but no machine learning models were used for classification or prediction purposes. Texture differences were noted in hippocampus, choroid plexus, and cerebellar white matter. Sex- and age-related differences appeared in the amygdala and brain stem. No harmonization was applied.

[

36] used multimodal quantitative MRI techniques to identify structural and physiological brain differences in young children with autism. The study included 60 children with autism and 60 without (ages 2-3). Radiomic features such as mean diffusivity (MD) and kurtosis were extracted from 38 brain regions using the AAL3 atlas. Post-processing involved image registration, segmentation, and atlas-based parcellation using SPM12 and CAT12. The study found lower iron content (QSM), CBF, and kurtosis-based measures in brain regions linked to language, memory and cognition. ROC analysis showed that combining QSM, CBF and DKI features resulted in the highest classification accuracy (AUC = 0.917). However, the study has several limitations including single-center data and a narrow age range, limiting generalizability. The study’s strengths lie in the integration of radiomics across multiple MRI contrasts.

2.2.4. Deep Learning Studies

In this study [

37] the authors used resting-state fMRI data from ABIDE I, preprocessed with Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes (CPAC) such as motion correction, bandpass filtering, MNI space normalization. Functional connectivity matrices (19,900 features) were input into a stacked denoising autoencoder and MLP, achieving 70% accuracy (sensitivity 74%, specificity 63%), outperforming SVM and RF. Despite no harmonization, the model showed modest generalization across sites. Identified patterns included anterior–posterior underconnectivity and posterior hyperconnectivity, supporting autism theories. However, low positive predictive value (4.3%) limits clinical utility. The authors of this study [

38] trained a stacked autoencoder (SAE) on rs-fMRI from 84 ABIDE-NYU participants (age 6–13). After preprocessing, 20 frequency-enriched independent components (3,400 features) were input into an SAE-SoftMax model, achieving 87.2% accuracy (sensitivity 92.9%, specificity 84.3%). Strengths included multi-band features and unsupervised learning; limitations included small, single-site data. The pipeline outperformed SVM and probabilistic neural networks.

In this study, [

39] a deep attention neural network (DANN) integrating rs-fMRI and personal characteristic (PC) data was proposed from 809 ABIDE participants. Data were preprocessed with the CPAC pipeline. The architecture fused attention layers and multilayer perceptrons. Accuracy was 73.2% (F1 score: 0.736), outperforming SVM, RF, and standard DNNs. Leave-one-site-out validation confirmed robustness. Inclusion of PC data enhanced the study’s results. A key limitation was lack of harmonization across sites.

[

40] used rs-fMRI data from the ABIDE I and II datasets were preprocessed to reduce the inherent dimensionality of the 4D volumes and enable their use in deep learning workflows. To achieve this, the temporal dimension was summarized using a series of voxel-wise transformations that preserved full spatial resolution, resulting in 3D feature volumes suitable for 3D convolutional neural networks (3D-CNNs). These features were designed to capture different aspects of local and global brain activity over time. This resulted in achieving a maximum accuracy of approximately 66%. Interestingly, combining all summary measures did not improve classification results, and support vector machine (SVM) models trained on the same features yielded comparable performance, suggesting limited added value from deep learning in this specific temporal transformation framework.

The authors of this study [

41] developed and compared 14 deep learning models, including 2D/3D CNNs, spatial transformer networks (STNs), RNNs, and RAMs, using structural MRI data from the ABIDE and Yonsei datasets. Preprocessing differed by site (e.g., MNI registration for ABIDE). No harmonization was applied, limiting generalizability. 3D CNNs performed best on ABIDE, RAMs on YUM. Attention maps highlighted basal ganglia involvement, consistent with repetitive behaviour theories. Despite no multimodal data or harmonization, the study's model diversity and interpretability are notable.

Table 1.

Comparison of radiomics and deep learning approaches for MRI-based autism classification.

Table 1.

Comparison of radiomics and deep learning approaches for MRI-based autism classification.

| |

Radiomics |

Deep Learning |

Hybrid |

| Feature Type |

Handcrafted (texture, shape, intensity) |

Learned automatically from image tensors |

Combination of handcrafted and learned features |

| Segmentation |

Required for ROI definition |

Optional (whole-brain or patch-based input) |

Usually required for handcrafted features; optional for deep inputs |

| Interpretability |

High |

Low |

Moderate |

| Preprocessing |

Strict normalization, harmonization, segmentation |

Variable; less dependent on-site harmonization |

Needed for handcrafted features, DL branches not as sensitive |

| Model Type |

Classical ML (i.e., SVM, RF, XGBoost) |

CNNs, 3D CNNs, ViTs |

Dual of fused architectures (i.e. AE+CN, GCN+ML) |

| Data Need |

Small to moderate datasets |

Large datasets, especially for training from scratch |

Moderate to large; depends on model complexity and fusion strategy |

| Pipeline |

Modular (multi-step) |

End-to-end |

Semi-modular; parallel or fused branches integrated in final layers |

Finally in this study [

42] the authors analyzed rs-fMRI from ABIDE I and II (2,226 samples) using pre-trained VGG-16 and ResNet-50. NIfTI images were converted to 2D JPEG axial slices and resized to 224×224. ResNet-50 achieved 87.0% accuracy, outperforming VGG-16 (63.4%). A GUI was developed for clinical deployment. However, the lack of 3D context and harmonization limits applicability.

3. Results

This systematic review included 49 studies conducted between 2011 and 2025, encompassing three major methodological paradigms in MRI-based classification of Autism: radiomics-based machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid models integrating elements of both. Among these, 21 studies employed radiomics and traditional machine learning algorithms, 25 utilized deep learning architectures, and 3 applied hybrid approaches that combined handcrafted radiomic features with neural network frameworks. The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I and II) datasets were the most used sources, either in full or partially, with additional studies relying on locally acquired or institutional datasets. Sample sizes ranged considerably, from fewer than 50 to over 1,000 participants, with a predominant focus on paediatric populations.

Performance metrics across studies varied by methodology and was typically reported in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and, less frequently, AUC (Area Under the Curve). Reported accuracies ranged from moderate (around 70%) to high (>90%), though often within limited or homogeneous datasets.

Stratified by modality, deep learning models trained on resting-state functional MRI i.e. [

37,

39] generally outperformed radiomics-based approaches demonstrated higher classification accuracies, often exceeding 80% and in some cases reaching 94.7%. These models, including autoencoders and CNNs, were trained end-to-end on connectivity matrices or voxel data. Despite strong internal validation results, deep learning models were rarely validated externally and often lacked harmonization across imaging sites, leading to concerns regarding their robustness and clinical translatability. However, structural MRI i.e. [

35] paired with radiomics features yielded respectable performance as well (i.e., accuracy of 80.9%), especially when using Random Forest or SVM classifiers. Diffusion MRI-based models, such as [

36] reported significance through correlation coefficients and permutation p-values rather than direct classification metrics, reflecting their exploratory nature. When considering datasets, the ABIDE I and II repositories were most frequently used and often associated with higher performance claims, though these were subject to site and scanner variability. Models trained on smaller, single-site cohorts tended to overfit and reported inflated accuracies without external validation. For instance, studies using personalized or statistical pipelines on restricted clinical populations i.e., [

43] often lacked generalization capability.

Notably, no single method demonstrated universal superiority across all settings. Deep learning models showed consistently strong results in internal cross-validation, especially when trained on rs-fMRI-derived connectivity matrices, but they often failed to generalize well due to limited external validation and demographic diversity. Radiomics approaches, while less accurate on average, offered greater transparency and interpretability, particularly when paired with atlas-based parcellations and explainability frameworks like LIME. Thus, while DL methods tend to outperform in terms of raw metrics, hybrid models integrating multimodal data and interpretable features may offer more balanced clinical applicability. Hybrid studies combining radiomic features with deep learning architectures were sparse but demonstrated classification performance reaching up to an accuracy of 89.47% and increased potential for interpretability. These models incorporated dual-branch autoencoders, graph convolutional networks, or feature-level fusion strategies to integrate anatomical and functional data. However, none of the included studies employed Vision Transformers (ViTs) within a radiomics-based hybrid framework. This absence may reflect the current architectural and computational limitations in integrating tabular, handcrafted radiomic features with the token-based, high-dimensional input structure required by ViTs. Structural MRI remained the dominant modality in radiomics studies, while deep learning approaches favoured rs-fMRI. Multimodal studies incorporating both data types were limited, and diffusion MRI was comparatively underutilized.

Preprocessing strategies across the reviewed literature varied greatly. While most studies employed standard steps such as motion correction, normalization, and segmentation, only a minority applied formal harmonization techniques to correct for site effects in multi-centre datasets. The lack of harmonization emerged as a recurrent limitation across both radiomics and deep learning pipelines, contributing to reduced reproducibility and generalizability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Challenges

This review is not currently registered in a systematic review database such as PROSPERO (

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) and only basic descriptive statistics were included. All three approaches mentioned in this study (radiomics, deep learning, hybrid) for autism classification using MRI present distinct methodological challenges and limitations (

Figure 5) that impact their reliability and clinical translation. In radiomics pipelines, segmentation sensitivity remains a critical challenge. The quality and reproducibility of radiomic features are heavily dependent on accurate brain segmentation, typically performed using tools like FreeSurfer or manual delineation. Variability in segmentation, whether due to differences in MRI acquisition, preprocessing, or atlas definitions, can introduce substantial bias into feature extraction, particularly for small or anatomically variable regions such as the amygdala or cerebellum. Additionally, the lack of standardization in feature definitions and extraction protocols (i.e., differences in texture calculation algorithms or intensity normalization) limits the comparability of radiomics studies across institutions and hinders reproducibility. Despite emerging efforts to define standardized radiomic feature sets (i.e., through the IBSI initiative), inconsistencies in preprocessing pipelines remain a concern.

Deep learning models, on the other hand, are well known for their dependance on large datasets. These models require large volumes of labeled data to generalize effectively and avoid overfitting. In autism research, the available datasets, such as ABIDE I and II are demographically imbalanced, and affected by inter-site variability, posing a significant limitation for training robust deep architectures. Furthermore, among the studies reviewed, relatively few explicitly employed explainable AI techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), or saliency maps with few exceptions [

44]. Most deep learning studies lacked systematic evaluation of feature importance or brain region relevance, limiting their clinical trustworthiness. This weakness makes it difficult for clinicians to trust and validate the biological plausibility of the learned features, particularly when predictions are not accompanied by transparent justifications.

Across all methodologies, small sample sizes and class imbalance are recurring issues. Many studies rely on datasets with fewer than a few hundred autism subjects, often skewed toward male or high-functioning individuals. This not only compromises the statistical power of classification models but also limits their generalizability to the broader autism spectrum, particularly among underrepresented subgroups (i.e., females, low-IQ individuals). Class imbalance, where the number of autism cases differs substantially from non-autistic cases, can lead to biased model training and inflated accuracy if not properly addressed through techniques like resampling, class weighting, or balanced evaluation metrics (i.e., AUC or F1-score).

Overall, these limitations underscore the importance of methodological rigor, data harmonization, and transparent reporting. Addressing them will be essential for converting AI-based autism classification models from research settings into reliable, real-world clinical tools.

5. Conclusions

This review synthesizes the state-of-the-art AI approaches in MRI-based classification of autism, revealing a methodological divergence between radiomics and deep learning approaches. From a clinical perspective, radiomics-based models are better suited for interpretability and integration into diagnostic workflows, whereas deep learning models may capture more subtle and distributed neurobiological patterns. The lack of standardized pipelines, inconsistent reporting of validation strategies, and limited exploration of multimodal fusion remain critical limitations across the field. Most studies continue to rely heavily on the ABIDE dataset, which, despite its size, suffers from site variability and demographic imbalances that compromise model generalizability. Additionally, few studies report performance metrics beyond accuracy, such as AUC or F1-score, which are essential for evaluating models in imbalanced classification tasks. The few existing hybrid studies favour more traditional DL architectures that are easier to merge with handcrafted features. In contrast, combining ViT embeddings with radiomics would require custom fusion strategies, such as cross-modal transformers, attention-based feature gating, or mutual redundancy filtering, to avoid overlap and overfitting. Without these advanced integration methods, naïve hybridization could dilute model performance and obscure interpretability, possibly deterring researchers from attempting this approach. To date, no studies involve the hybrid approach of radiomic features and deep learning approaches using Vision Transformers. A possible explanation for this could be the different representational domains of Vision Transformers (ViTs) and radiomics. ViTs operate on raw imaging data, typically represented as fixed-size 2D or 3D patches tokens. These patches are embedded and passed through a transformer encoder that captures global contextual relationships via self-attention. In contrast, radiomics generates handcrafted, tabular features from predefined regions of interest (ROIs), focusing on intensity, texture, shape, and statistical descriptors. These are not image tensors, but feature vectors, which don’t naturally integrate with the image-token-based ViT pipeline. Radiomic features are often low-dimensional and tabular, while ViT embeddings are high-dimensional and hierarchical. There is no standard practice for injecting external feature vectors into the transformer architecture, unlike CNNs where radiomics can be concatenated with fully connected layers. Also, Vision Transformers require large-scale pretraining to generalize well. Most autism-related datasets have limited sample sizes. Researchers usually prioritize either radiomics and ML -small and data friendly approach or ViT and transfer learning but not both due to architectural and training complexities. In autism imaging, radiomics and ViT-extracted features may partially overlap in what they represent (i.e. shape, edge structure). Integrating both without feature redundancy handling (via feature selection, attention gating, or cross-modal transformers) could lead to overfitting or reduced performance, discouraging experimental attempts.

To advance the field, future research should focus on developing explainable hybrid models that integrate radiomic features with deep learning and multimodal fusion strategies such as attention mechanisms, graph-based representations, or cross-modal transformers. Harmonization techniques are essential to reduce site effects, alongside external validation and stratified analysis by age and sex. Standardized preprocessing, open benchmarking datasets, and tailored explainability frameworks are also critical. These steps will support the clinical translation of AI tools for autism diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized subtype identification.

Table 2.

Summary of reviewed publications.

Table 2.

Summary of reviewed publications.

| Author |

Topic |

MRI modality |

Dataset size |

Performance |

Model Type |

(Yahata et al., 2016) [45] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=107, autism=74 |

accuracy=85% |

Sparse logistic regression (SLR) |

|

(Jahani et al,, 2024) [46] |

DL |

sMRI, rs-fMRI |

HC=359,

autism=343 |

Accuracy=72.9% |

Multi-channel 3D-DenseNet |

(Abraham et al., 2017) [47] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=468, autism=403 |

accuracy=67% |

SVC (Support Vector Classification) |

(Heinsfeld et al., 2018) [37] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=530, autism=505 |

accuracy=70% |

Deep neural network (stacked denoising autoencoders + MLP) |

(Zhao et al., 2018) [48] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=46, autism=54 |

accuracy=81% |

SVM ensemble classifier |

(Z. Xiao et al., 2018) [49] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=42, autism=42 |

accuracy=88.10% |

stacked autoencoder (SAE) with softmax classifier |

|

(Yan Tang et al., 2021)[50] |

DL |

sMRI |

HC= 450,

autism=421 |

accuracy=72.5% |

Self-attention deep learning model using graph-based structural covariance networks (SCNs) |

(H. Li et al., 2018) [51] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=161, autism=149 |

accuracy=70.4% |

Deep transfer learning NN (DTL-NN), stacked sparse autoencoder, softmax regression |

(X. Li et al., 2018) [52] |

DL |

task fMRI |

HC=48, autism=82 |

accuracy=85.7% |

2CC3D deep convolutional neural network |

(Wang, Xiao, & Wu, 2019) [53] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=553, autism=501 |

accuracy=93.59% |

Stacked Sparse Auto-Encoder (SSAE) with softmax classifier |

(Yang et al., 2019) [54] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=530, autism=505 |

accuracy=75.27% |

DNN (MLP) |

(Ke et al., 2020) [41] |

DL |

sMRI |

HC=1046, autism=946 |

accuracy=66% |

3D CNN, RAM, RNN, STN, CAM |

(Thomas et al., 2020) [40] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=542, autism=620 |

accuracy=66% |

3D convolutional neural network (3D-CNN), linear SVM |

|

(Sherkatghanet al., 2020) [55] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=530, autism=505 |

accuracy=70.22% |

CNN |

|

(Sewani & Kashef, 2020) [56] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=573, autism=539 |

accuracy=84.05% |

Autoencoder-CNN |

(Niu et al., 2020) [39] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=401, autism=408 |

accuracy=73.2% |

Multichannel Deep Attention Neural Network (DANN) |

(M. Leming et al., 2020) [57] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=15,903, autism=1,711 |

accuracy=67.03% |

CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) ensemble |

(Rakić et al., 2020) [58] |

DL |

sMRI, rs fMRI |

HC=449, autism=368 |

accuracy=85.06% |

Stacked Autoencoders + Multilayer Perceptrons |

(Ahammed et al., 2021) [59] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=105, autism=79 |

accuracy=94.7% |

DarkautismNet (based on modified DarkNet-19) |

|

(Gao et al., 2021) [60] |

DL |

sMRI |

HC=567, autism=518 |

accuracy=71.8% |

ResNet (deep convolutional neural network) |

(Almuqhim & Saeed, 2021) [61] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=530, autism=505 |

accuracy=70.8% |

autism-SAENet (Sparse Autoencoder + Deep Neural Network) |

|

(Husna et al., 2021) [42] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=1146, autism=1060 |

accuracy=87.0% |

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): VGG-16 and ResNet-50 |

(M. J. Leming et al., 2021) [62] |

DL |

sMRI |

HC=12623, autism=1555 |

AUC=73.54% |

CNN |

(Jung et al., 2023) [63] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=462, autism=418 |

accuracy=78.1% |

Stacked Autoencoder (SAE), MLP-based classifier |

|

(Vidya et al., 2025) [64] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=476, autism=408 |

accuracy=98.2% |

Stacked Sparse Autoencoder with softmax classifier |

|

(Khan & Katarya, 2025) [65] |

DL |

rs fMRI |

HC=505, autism=530 |

accuracy=93.4% |

CNN and BERT |

|

(Ashraf et al., 2025) [66] |

DL |

sMRI |

HC=1090, autism=1012 |

accuracy=93.49% |

CNN (NeuroNet57), fineKNN classifier |

|

(Manikantan & Jaganathan, 2023) [67] |

hybrid |

rs fMRI, sMRI |

HC=573, autism=539 |

accuracy=81.23% |

Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) |

|

(Song et al., 2024) [68] |

hybrid |

sMRI |

HC=62, autism=85 |

accuracy=89.47% |

SVM, CNN, RF, LR, KNN |

|

(Zheng et al., 2025) [69] |

hybrid |

sMRI, rs fMRI |

HC=111, autism=103 |

accuracy=70.7% |

Autoencoder-dual branch |

|

(Reiter et al., 2020) [70] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=350, autism=306 |

accuracy=73.7% |

random forest (RF), conditional random forest (CRF) |

|

(Anderson et al., 2011) [71] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=53, autism=48 |

accuracy=89% |

Linear classifier |

|

(Plitt et al., 2015) [72] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=148, autism=148 |

accuracy=76.67% |

L2-regularized logistic regression (L2LR), Linear SVM (L-SVM) |

(X. Xiao et al., 2015) [33] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=0, autism=46 |

accuracy=80.9% |

Random Forest |

(Chaddad, Desrosiers, Hassan, et al., 2017) [34] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=30, autism=34 |

accuracy=75% |

SVM, Random Forest |

|

(Zhang et al., 2018) [73] |

radiomics-ML |

DTI |

HC=79, autism=70 |

accuracy=78.33% |

Random forest |

|

(Soussia & Rekik, 2018) [74] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=186, autism=155 |

accuracy=61.69% |

Unsupervised SIMLR (Similarity Learning via Multiple Kernels), ensemble SVM |

(Dekhil et al., 2019) [75] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI, sMRI |

HC=113, autism=72 |

accuracy=81% |

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF) |

|

(Spera et al., 2019) [76] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=88, autism=102 |

accuracy=77% |

Linear SVM |

|

(Kazeminejad & Sotero, 2019) [77] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=403, autism=413 |

accuracy=95% |

SVM (Gaussian kernel) |

|

(Chaitra et al., 2020) [78] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=556, autism=432 |

accuracy=70.1% |

SVM |

|

(Squarcina et al., 2021) [79] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=36, autism=40 |

accuracy=84.2% |

Support Vector Machine (SVM) with RBF kernel |

|

(Ali et al., 2022) [80] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=336, autism=328 |

accuracy=71.6% |

Neural network (NN) |

|

(Dong et al., 2025) [81] |

radiomics-ML |

rs fMRI |

HC=467, autism=403 |

accuracy=72.2% |

SVM, FCN, AE-FCN, GCN, EV-GCN |

|

(Raj et al., 2025) [82] |

radiomics-ML |

sMRI |

HC=0, autism=51 |

N/A |

k-means clustering |

|

(He et al., 2025) [83] |

radiomics-ML |

DTI, sMRI, rs fMRI |

HC=47, autism=50 |

accuracy=82.69% |

SVM |

|

(Chaddad, Desrosiers, & Toews, 2017) [35] |

radiomics-statistics |

sMRI |

HC=573, autism=539 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

(Sarovic et al., 2020) [43] |

radiomics-statistics |

sMRI |

HC=21, autism=24 |

accuracy=78.9% |

SVM, logistic regression, decision tree |

|

(Tang et al., 2022) [36] |

radiomics-statistics |

DTI, sMRI |

HC=60, autism=60 |

AUC=91.7% |

N/A |

References

- American Psychiatric Association, “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Santomauro et al., “The global epidemiology and health burden of the autism spectrum: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021,” Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 111–121, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Sandin, P. Lichtenstein, R. Kuja-Halkola, C. Hultman, H. Larsson, and A. Reichenberg, “The heritability of autism spectrum disorder,” JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 318, no. 12, pp. 1182–1184, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Modabbernia, E. Velthorst, and A. Reichenberg, “Environmental risk factors for autism: an evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses,” Molecular Autism 2017 8:1, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Van Rooij et al., “Cortical and subcortical brain morphometry differences between patients with autism spectrum disorder and healthy individuals across the lifespan: Results from the ENIGMA ASD working group,” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 175, no. 4, pp. 359–369, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Emerson et al., “Functional neuroimaging of high-risk 6-month-old infants predicts a diagnosis of autism at 24 months of age,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 9, no. 393, p. eaag2882, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Ecker, S. Y. Bookheimer, and D. G. M. Murphy, “Neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorder: Brain structure and function across the lifespan,” Lancet Neurol, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 1121–1134, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Padmanabhan, C. J. Lynch, M. Schaer, and V. Menon, “The Default Mode Network in Autism,” Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, vol. 2, no. 6, p. 476, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Ameis and M. Catani, “Altered white matter connectivity as a neural substrate for social impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Cortex, vol. 62, pp. 158–181, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Horder et al., “Glutamate and GABA in autism spectrum disorder-a translational magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in man and rodent models,” Transl Psychiatry, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. McCrimmon and K. Rostad, “Test Review: Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part II): Toddler Module,” J Psychoeduc Assess, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 88–92, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. H. (Sophy) Kim, V. Hus, and C. Lord, “Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised,” Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders, pp. 345–349, 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Happé and U. Frith, “Annual Research Review: Looking back to look forward – changes in the concept of autism and implications for future research,” J Child Psychol Psychiatry, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 218–232, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Kapp, K. Gillespie-Lynch, L. E. Sherman, and T. Hutman, “Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity.,” Dev Psychol, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 59–71, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Klin, “Biomarkers in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Challenges, Advances, and the Need for Biomarkers of Relevance to Public Health,” Focus: Journal of Life Long Learning in Psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 135, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Arbabshirani, S. Plis, J. Sui, and V. D. Calhoun, “Single subject prediction of brain disorders in neuroimaging: Promises and pitfalls,” Neuroimage, vol. 145, no. Pt B, pp. 137–165, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Bone, M. S. Goodwin, M. P. Black, C. C. Lee, K. Audhkhasi, and S. Narayanan, “Applying Machine Learning to Facilitate Autism Diagnostics: Pitfalls and Promises,” J Autism Dev Disord, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 1121–1136, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. Lambin et al., “Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis,” Eur J Cancer, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 441–446, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. J. W. L. Aerts et al., “Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach,” Nat Commun, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. Xiao et al., “Quantitative susceptibility mapping based hybrid feature extraction for diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease,” Neuroimage Clin, vol. 24, p. 102070, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Hashido, S. Saito, and T. Ishida, “A radiomics-based comparative study on arterial spin labeling and dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion-weighted imaging in gliomas,” Scientific Reports 2020 10:1, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Su et al., “T2-FLAIR, DWI and DKI radiomics satisfactorily predicts histological grade and Ki-67 proliferation index in gliomas,” Am J Transl Res, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 9182, 2021, Accessed: Jun. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8430185/.

- M. L. Tsai et al., “Morphometric and radiomics analysis toward the prediction of epilepsy associated with supratentorial low-grade glioma in children,” Cancer Imaging, vol. 25, no. 1, p. 63, Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Singh, V. S. Jain, and J. P. J. Yu, “Diffusion radiomics for subtyping and clustering in autism spectrum disorder: A preclinical study,” Magn Reson Imaging, vol. 96, p. 116, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Zwaigenbaum et al., “Early Intervention for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder Under 3 Years of Age: Recommendations for Practice and Research,” Pediatrics, vol. 136, no. Supplement_1, pp. S60–S81, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. J. C. Schielen, J. Pilmeyer, A. P. Aldenkamp, and S. Zinger, “The diagnosis of ASD with MRI: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Translational Psychiatry 2024 14:1, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Moon, J. Hwang, R. Kana, J. Torous, and J. W. Kim, “Accuracy of machine learning algorithms for the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of brain magnetic resonance imaging studies,” Dec. 01, 2019, JMIR Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- S. Huda, D. M. Khan, K. Masroor, Warda, A. Rashid, and M. Shabbir, “Advancements in automated diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder through deep learning and resting-state functional mri biomarkers: a systematic review,” Dec. 01, 2024, Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdelrahim et al., “AI-based non-invasive imaging technologies for early autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: A short review and future directions,” Artif Intell Med, vol. 161, p. 103074, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Khodatars et al., “Deep learning for neuroimaging-based diagnosis and rehabilitation of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A review,” Comput Biol Med, vol. 139, p. 104949, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Alharthi and S. M. Alzahrani, “Do it the transformer way: A comprehensive review of brain and vision transformers for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis and classification,” Comput Biol Med, vol. 167, p. 107667, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Ma, Y. Huang, Y. Pan, Y. Wang, and Y. Wei, “Meta-data Study in Autism Spectrum Disorder Classification Based on Structural MRI,” Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, pp. 1–1, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Xiao et al., “Diagnostic model generated by MRI-derived brain features in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder,” Autism Research, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 620–630, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Chaddad, C. Desrosiers, L. Hassan, and C. Tanougast, “Hippocampus and amygdala radiomic biomarkers for the study of autism spectrum disorder,” BMC Neurosci, vol. 18, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, C. Desrosiers, and M. Toews, “Multi-scale radiomic analysis of sub-cortical regions in MRI related to autism, gender and age,” Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Tang et al., “Application of Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Autism in Children,” Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 9, p. 818404, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Heinsfeld, A. R. Franco, R. C. Craddock, A. Buchweitz, and F. Meneguzzi, “Identification of autism spectrum disorder using deep learning and the ABIDE dataset,” Neuroimage Clin, vol. 17, pp. 16–23, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang, Z. Xiao, B. Wang, and J. Wu, “Identification of Autism Based on SVM-RFE and Stacked Sparse Auto-Encoder,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 118030–118036, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Niu et al., “Multichannel Deep Attention Neural Networks for the Classification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Neuroimaging and Personal Characteristic Data,” Complexity, vol. 2020, no. 1, p. 1357853, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Thomas, S. Gallo, L. Cerliani, P. Zhutovsky, A. El-Gazzar, and G. van Wingen, “Classifying Autism Spectrum Disorder Using the Temporal Statistics of Resting-State Functional MRI Data With 3D Convolutional Neural Networks,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 11, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Ke, S. Choi, Y. H. Kang, K. A. Cheon, and S. W. Lee, “Exploring the Structural and Strategic Bases of Autism Spectrum Disorders with Deep Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 153341–153352, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. N. S. Husna, A. R. Syafeeza, N. A. Hamid, Y. C. Wong, and R. A. Raihan, “Functional magnetic resonance imaging for autism spectrum disorder detection using deep learning,” J Teknol, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 45–52, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Sarovic, N. Hadjikhani, J. Schneiderman, S. Lundström, and C. Gillberg, “Autism classified by magnetic resonance imaging: A pilot study of a potential diagnostic tool,” Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1–18, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Lundberg, P. G. Allen, and S.-I. Lee, “A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions”. [CrossRef]

- N. Yahata et al., “A small number of abnormal brain connections predicts adult autism spectrum disorder,” Nat Commun, vol. 7, p. 11254, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Jahani, I. Jahani, A. Khadem, B. B. Braden, M. Delrobaei, and B. J. MacIntosh, “Twinned neuroimaging analysis contributes to improving the classification of young people with autism spectrum disorder,” Scientific Reports 2024 14:1, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abraham et al., “Deriving reproducible biomarkers from multi-site resting-state data: An Autism-based example,” Neuroimage, vol. 147, pp. 736–745, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhao, H. Zhang, I. Rekik, Z. An, and D. Shen, “Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders Using Multi-Level High-Order Functional Networks Derived From Resting-State Functional MRI,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 12, p. 184, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xiao, C. Wang, N. Jia, and J. Wu, “SAE-based classification of school-aged children with autism spectrum disorders using functional magnetic resonance imaging,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 77, no. 17, pp. 22809–22820, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, D. Peng, Y. Shang, and J. Gao, “Autistic Spectrum Disorder Detection and Structural Biomarker Identification Using Self-Attention Model and Individual-Level Morphological Covariance Brain Networks,” Front Neurosci, vol. 15, p. 756868, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, N. A. Parikh, and L. He, “A novel transfer learning approach to enhance deep neural network classification of brain functional connectomes,” Front Neurosci, vol. 12, no. JUL, p. 491, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, N. C. Dvornek, Y. Zhou, J. Zhuang, P. Ventola, and J. S. Duncan, “Efficient Interpretation of Deep Learning Models Using Graph Structure and Cooperative Game Theory: Application to ASD Biomarker Discovery,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 11492 LNCS, pp. 718–730, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Xiao, and J. Wu, “Functional connectivity-based classification of autism and control using SVM-RFECV on rs-fMRI data,” Physica Medica, vol. 65, pp. 99–105, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, M. S. Islam, and A. M. A. Khaled, “Functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging classification of autism spectrum disorder using the multisite ABIDE dataset,” 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics, BHI 2019 - Proceedings, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sherkatghanad et al., “Automated Detection of Autism Spectrum Disorder Using a Convolutional Neural Network,” Front Neurosci, vol. 13, p. 1325, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Sewani and R. Kashef, “An Autoencoder-Based Deep Learning Classifier for Efficient Diagnosis of Autism,” Children, vol. 7, no. 10, p. 182, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Leming, J. M. Górriz, and J. Suckling, “Ensemble Deep Learning on Large, Mixed-Site fMRI Datasets in Autism and Other Tasks,” Int J Neural Syst, vol. 30, no. 7, p. 2050012, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Rakić, M. Cabezas, K. Kushibar, A. Oliver, and X. Lladó, “Improving the detection of autism spectrum disorder by combining structural and functional MRI information,” Neuroimage Clin, vol. 25, p. 102181, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Ahammed, S. Niu, M. R. Ahmed, J. Dong, X. Gao, and Y. Chen, “DarkASDNet: Classification of ASD on Functional MRI Using Deep Neural Network,” Front Neuroinform, vol. 15, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao et al., “Multisite Autism Spectrum Disorder Classification Using Convolutional Neural Network Classifier and Individual Morphological Brain Networks,” Front Neurosci, vol. 14, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Almuqhim and F. Saeed, “ASD-SAENet: A Sparse Autoencoder, and Deep-Neural Network Model for Detecting Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Using fMRI Data,” Front Comput Neurosci, vol. 15, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Leming, S. Baron-Cohen, and J. Suckling, “Single-participant structural similarity matrices lead to greater accuracy in classification of participants than function in autism in MRI,” Mol Autism, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Jung, E. Jeon, E. Kang, and H. I. Suk, “EAG-RS: A Novel Explainability-guided ROI-Selection Framework for ASD Diagnosis via Inter-regional Relation Learning,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 1400–1411, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Vidya, K. Gupta, A. Aly, A. Wills, E. Ifeachor, and R. Shankar, “Explainable AI for Autism Diagnosis: Identifying Critical Brain Regions Using fMRI Data,” Sep. 2025, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2409.15374.

- K. Khan and R. Katarya, “MCBERT: A multi-modal framework for the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder,” Biol Psychol, vol. 194, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Ashraf, Q. Zhao, W. H. Bangyal, M. Raza, and M. Iqbal, “Female autism categorization using CNN based NeuroNet57 and ant colony optimization,” Comput Biol Med, vol. 189, p. 109926, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Manikantan and S. Jaganathan, “A Model for Diagnosing Autism Patients Using Spatial and Statistical Measures Using rs-fMRI and sMRI by Adopting Graphical Neural Networks,” Diagnostics, vol. 13, no. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Song et al., “Combining Radiomics and Machine Learning Approaches for Objective ASD Diagnosis: Verifying White Matter Associations with ASD,” May 2024, Accessed: Mar. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.16248v1.

- Q. Zheng, P. Nan, Y. Cui, and L. Li, “ConnectomeAE: Multimodal brain connectome-based dual-branch autoencoder and its application in the diagnosis of brain diseases,” Comput Methods Programs Biomed, vol. 267, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Reiter, A. Jahedi, A. R. J. Fredo, I. Fishman, B. Bailey, and R. A. Müller, “Performance of machine learning classification models of autism using resting-state fMRI is contingent on sample heterogeneity,” Neural Comput Appl, vol. 33, no. 8, p. 3299, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Anderson et al., “Functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging classification of autism,” Brain, vol. 134, no. 12, p. 3739, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Plitt, K. A. Barnes, and A. Martin, “Functional connectivity classification of autism identifies highly predictive brain features but falls short of biomarker standards,” Neuroimage Clin, vol. 7, p. 359, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhang et al., “Whole brain white matter connectivity analysis using machine learning: An application to autism,” Neuroimage, vol. 172, pp. 826–837, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Soussia and I. Rekik, “Unsupervised Manifold Learning Using High-Order Morphological Brain Networks Derived From T1-w MRI for Autism Diagnosis,” Front Neuroinform, vol. 12, p. 70, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- O. Dekhil et al., “A Personalized Autism Diagnosis CAD System Using a Fusion of Structural MRI and Resting-State Functional MRI Data,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 10, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Spera et al., “Evaluation of altered functional connections in male children with autism spectrum disorders on multiple-site data optimized with machine learning,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 10, p. 620, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Kazeminejad and R. C. Sotero, “Topological properties of resting-state FMRI functional networks improve machine learning-based autism classification,” Front Neurosci, vol. 13, no. JAN, p. 414728, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Chaitra, P. A. Vijaya, and G. Deshpande, “Diagnostic prediction of autism spectrum disorder using complex network measures in a machine learning framework,” Biomed Signal Process Control, vol. 62, p. 102099, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Squarcina et al., “Automatic classification of autism spectrum disorder in children using cortical thickness and support vector machine,” Brain Behav, vol. 11, no. 8, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Ali et al., “The Role of Structure MRI in Diagnosing Autism,” Diagnostics, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 165, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, D. Batalle, and M. Deprez, “A Framework for Comparison and Interpretation of Machine Learning Classifiers to Predict Autism on the ABIDE Dataset,” Hum Brain Mapp, vol. 46, no. 5, p. e70190, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Raj, R. Ratnaik, S. S. Sengar, and A. R. J. Fredo, “Characterizing ASD Subtypes Using Morphological Features from sMRI with Unsupervised Learning,” Stud Health Technol Inform, vol. 327, pp. 1403–1407, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. He et al., “Combining functional, structural, and morphological networks for multimodal classification of developing autistic brains,” Brain Imaging Behav, pp. 1–13, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).