Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Imaging in Ovarian Carcinoma

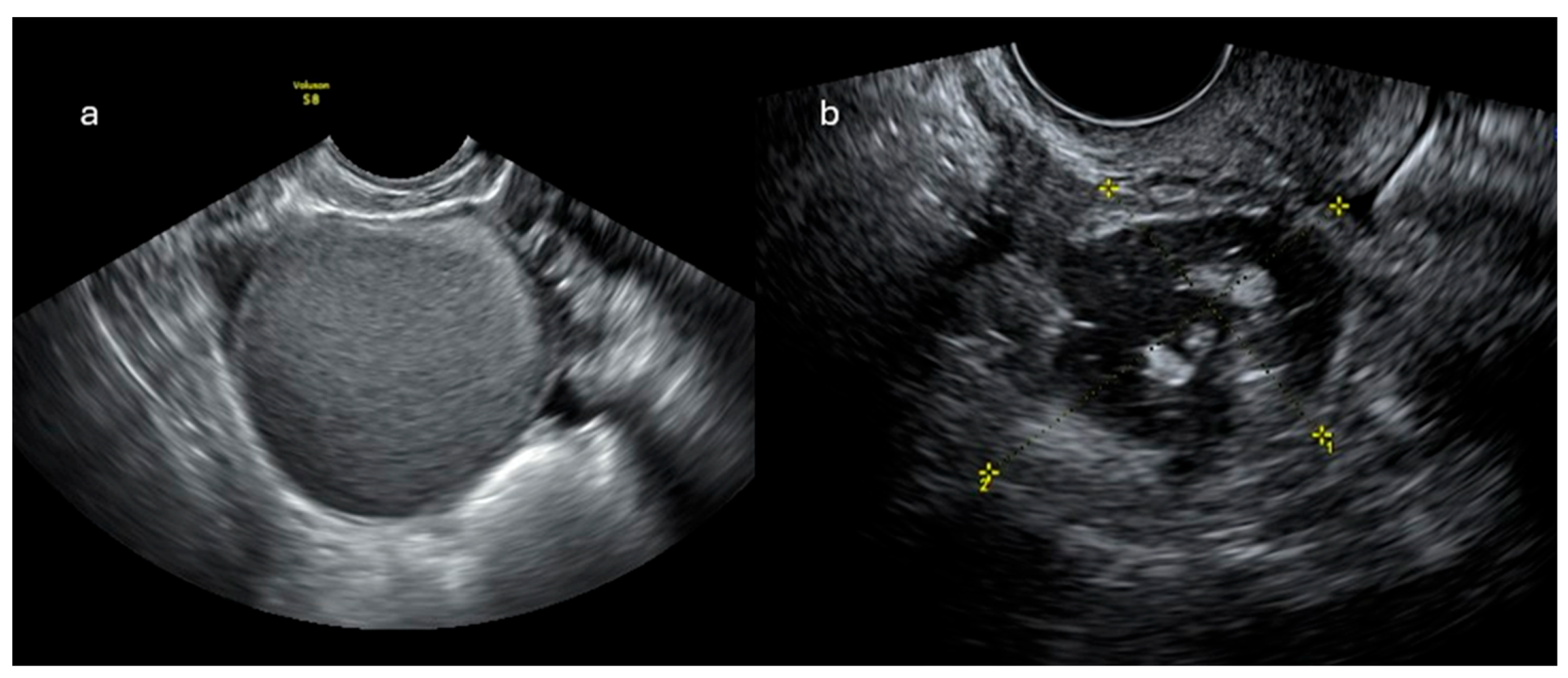

2.1. Ultrasonographic Imaging

2.1.1. IOTA ADNEX Model

2.1.2. O-RADS US

- O-RADS 0: incomplete evaluation

- O-RADS 1: physiological findings

- O-RADS 2: lesions almost certainly benign (<1% risk of malignancy)

- O-RADS 3: lesions with low risk of malignancy (1-10%)

- O-RADS 4: lesions with intermediate risk of malignancy (10-50%)

- O-RADS 5: lesions with high risk of malignancy (>50%)

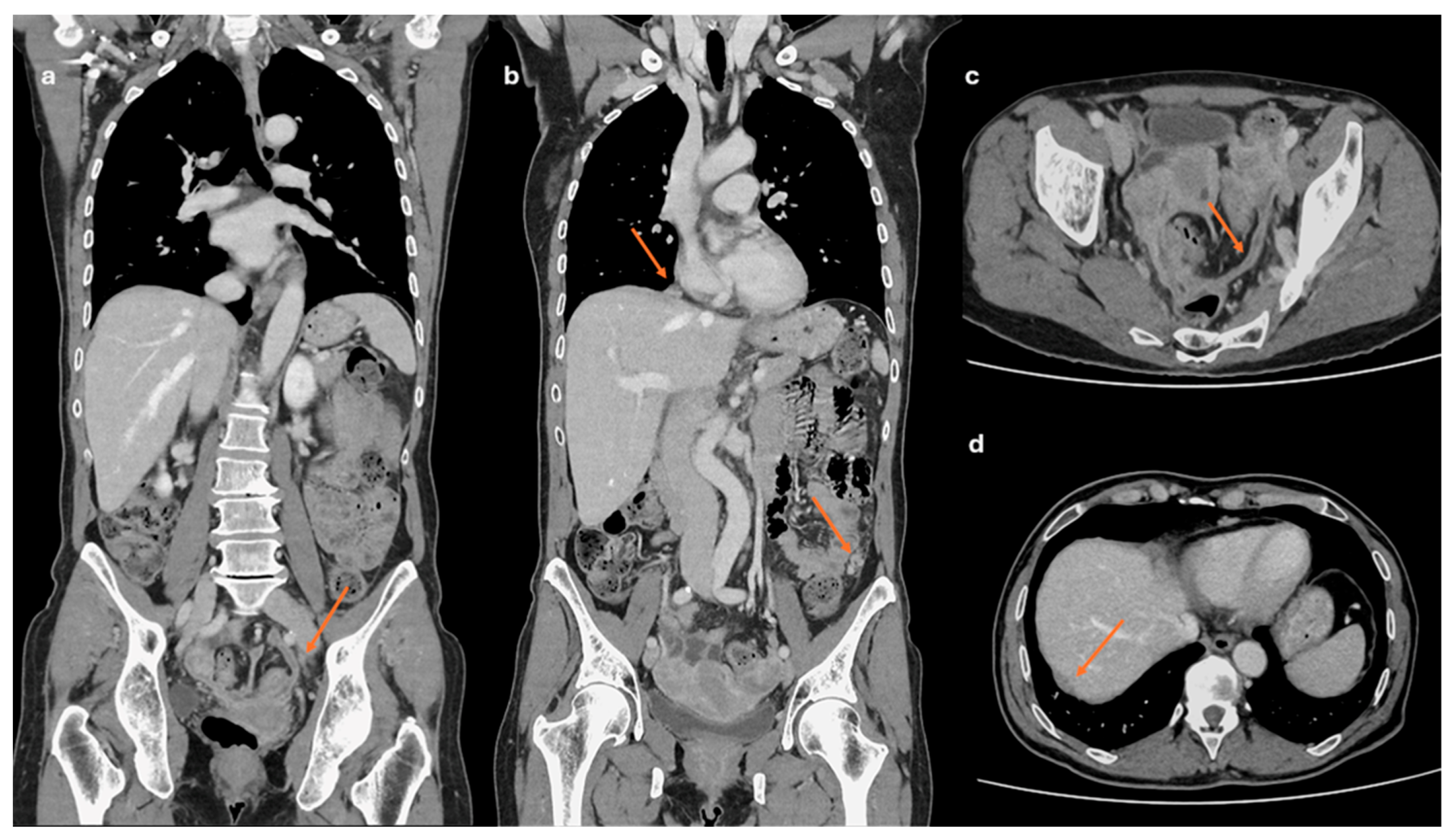

2.2. CT Imaging

2.3. MRI Imagingg

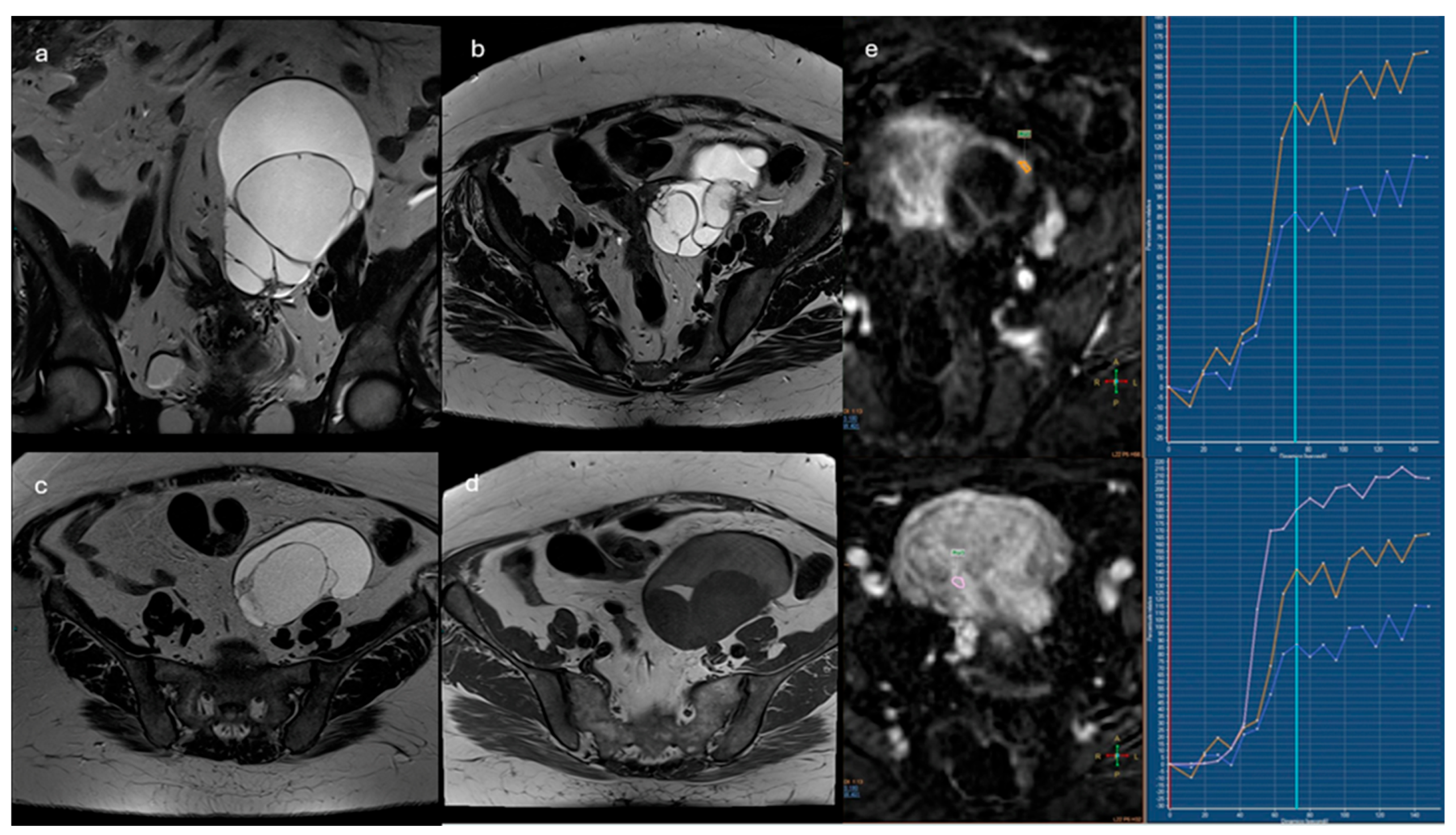

2.3.1. ADNEX-MR Scoring System

- Absence of ovarian lesions

- Benign lesions: lesions with homogeneous content (serous, blood, fat) and the absence of wall enhancement and/or with hypointense solid tissue signal in T2 sequences and at high b values

- Probably benign lesions: absence of solid tissue or solid tissue with type 1 enhancement curve

- Indeterminate lesions: presence of solid tissue with type 2 curve

- Likely malignant lesions: type 3 enhancement curve and presence of peritoneal implants

2.3.2. O-RADS MRI Score

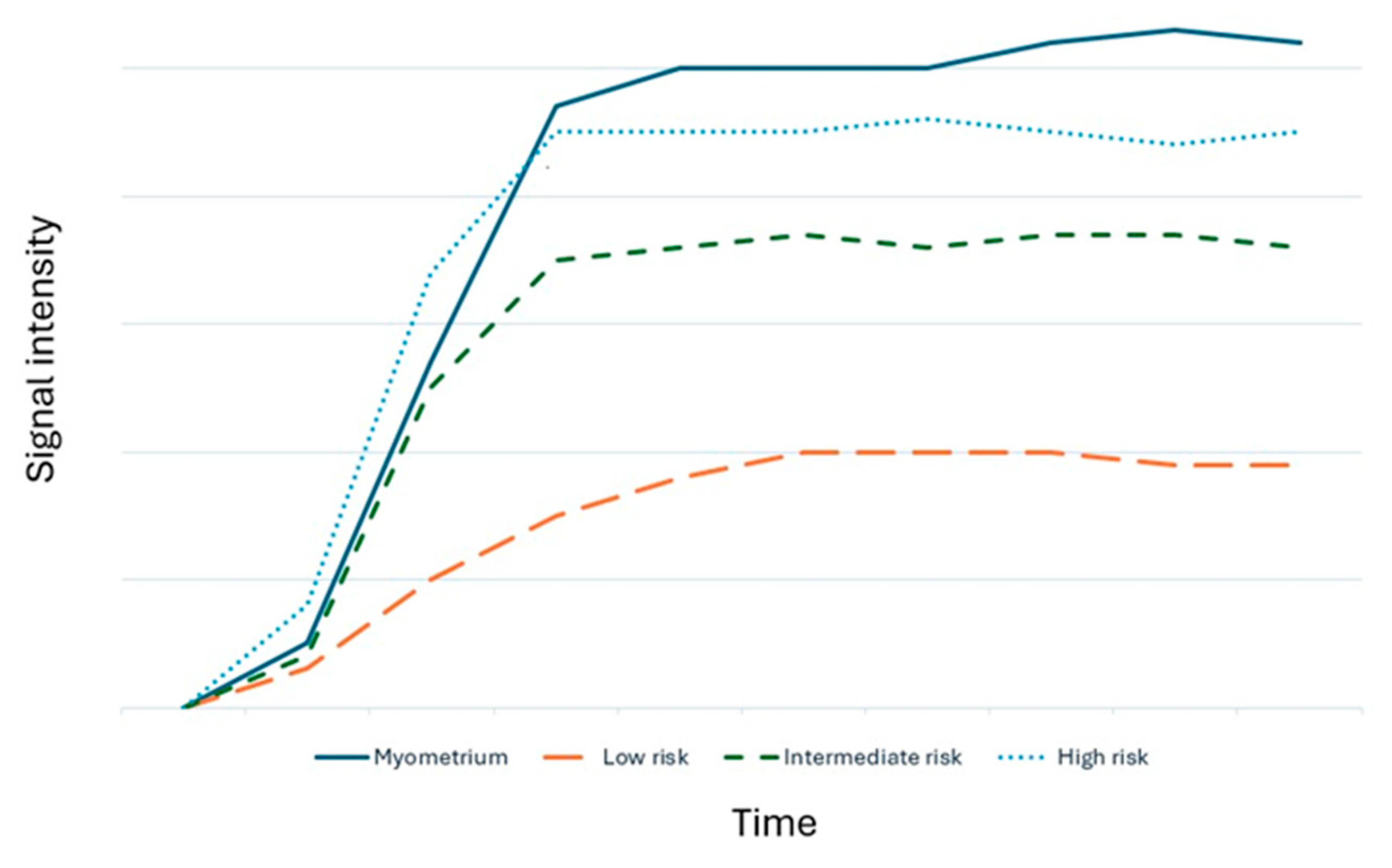

- Type1(low risk): slower increase in signal intensity (enhancement) of solid tissue than that of the myometrium, without a peak or plateau

- Type 2 (intermediate risk): moderate initial increase in solid tissue signal with a slower or equal slope to that of the myometrial, followed by a plateau

- Type 3 (high risk): pronounced signal increase with an early peak compared with that of myometrium

- Unilocular cysts with uncomplicated fluid or endometrioid content, with mild wall enhancement but without intracystic solid portions (e.g., endometrioma)

- Adipose-content lesions without intralesional solid tissue; in this case, the adipose tissue shows hyperintense signal in T2- and T1-weighted sequences, with signal drop in fat-sat sequences. It is necessary to distinguish Rokitansky nodule, which may show enhancement, from solid tissue (e.g., mature teratoma).

- Solid lesions with homogeneously hypointense signal both in T2w and DWI sequences at high b-values, regardless of the type of enhancement after mdc (e.g., ovarian fibroma)

- Fallopian tubes dilated by simple fluid, with mild and subtle wall enhancement in the absence of solid tissue

- Para-ovarian cysts at any type of fluid content, which may or may not show wall enhancement, without intralesional solid tissue.

- Unilocular cysts (proteinaceous/hemorrhagic/mucinous fluid content) with wall enhancement but without solid tissue

- Multilocular cysts at any type of fluid content, with thin septa that may show enhancement and absence of solid tissue

- Lesions with solid tissue (excluding solid lesions described in score 2) that show low-risk enhancement curve (type1).

- Fallopian tubes with non-simple fluid content, thickened walls, no solid tissue.

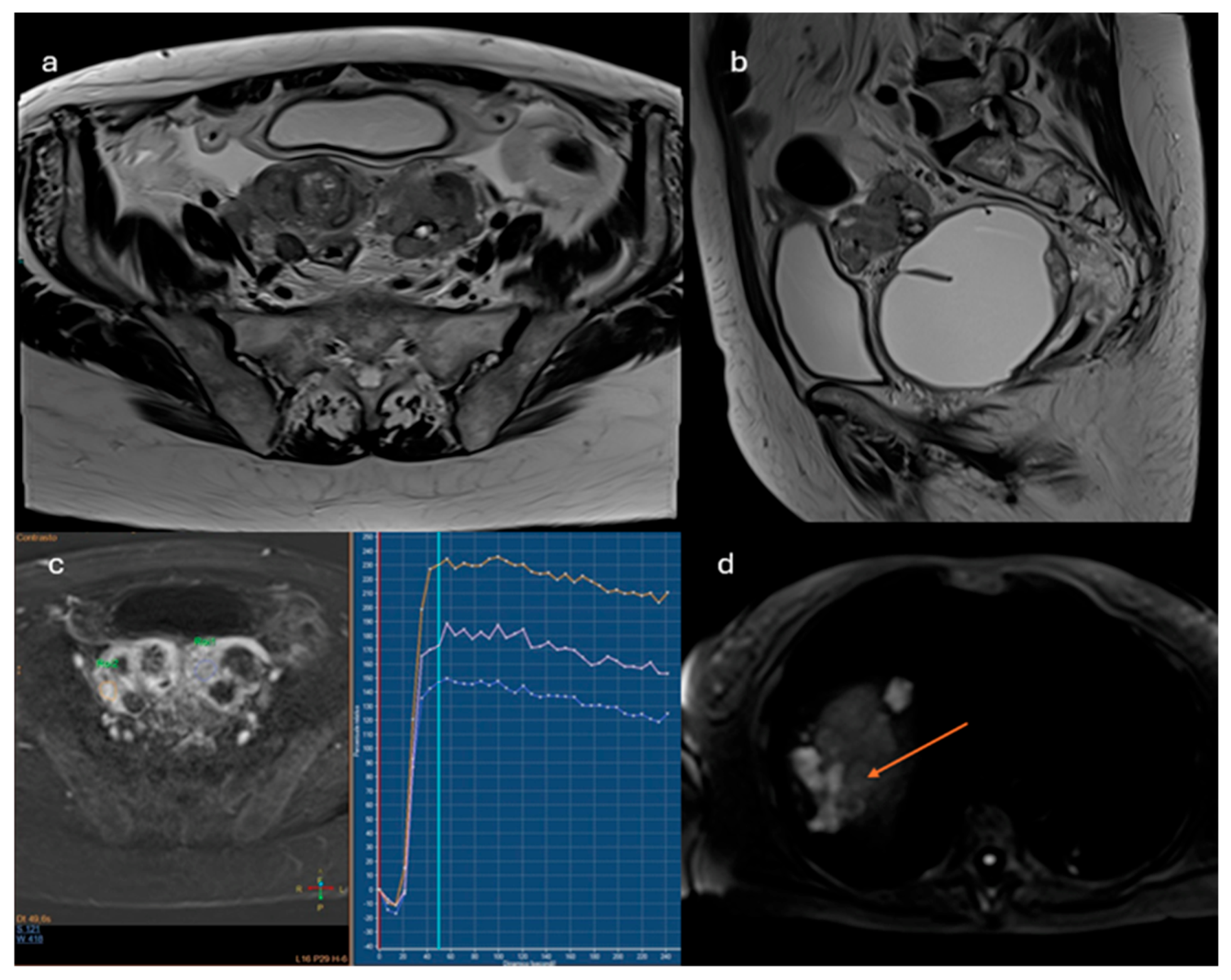

- Lesions with solid tissue (excluding solid lesions described in score 2) showing type 2 enhancement curve (intermediate risk; Figure 4)

- Solid lesions showing enhancement < myometrial at 30-40 seconds, if perfusion study is not available

- Lesions with lipid components and solid tissue with enhancement

- Lesions showing a type 3 enhancement curve (high risk)

- Solid lesions showing enhancement > myometrium at 30-40 seconds, if perfusion study is not available

- Lesions associated with the presence of peritoneal implants and/or secondary disease localization (Figure 5)

3. New Perspectives and AI in Ovarian Cancer

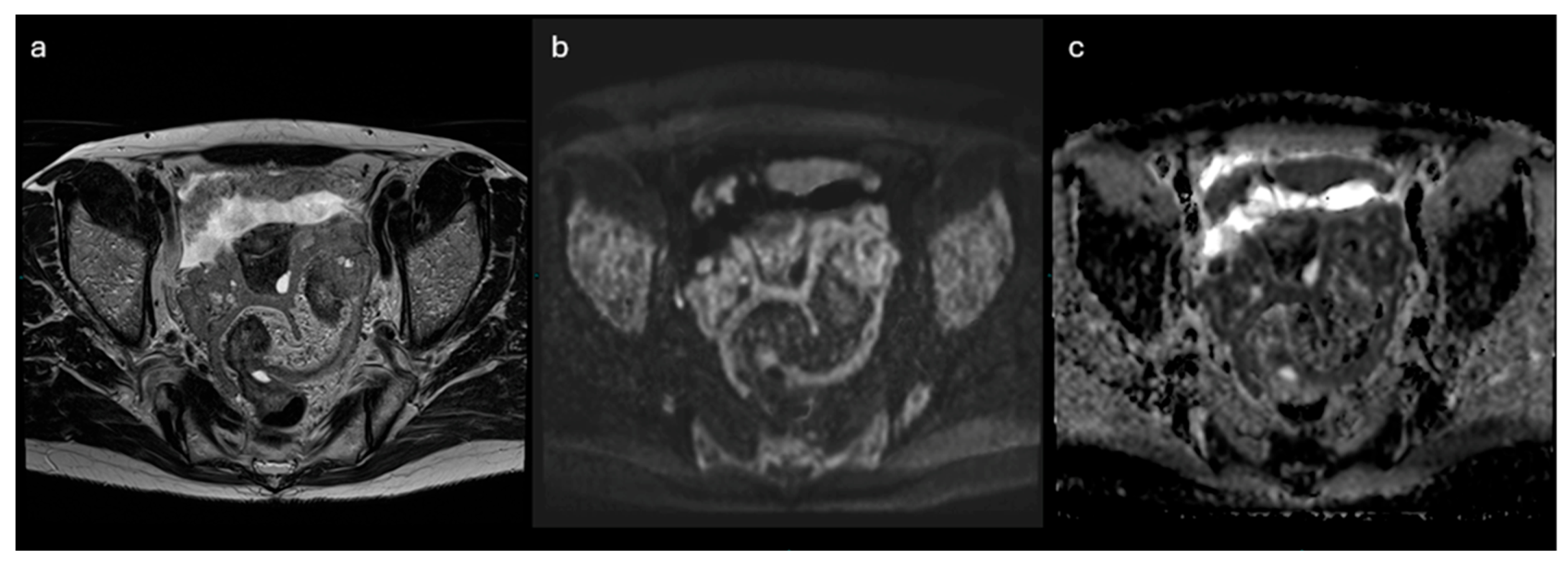

3.1. O-RADS MRI/ADC Score

3.2. NON- CONTRAST- MRI Score

3.3. PET-MRI

| Modality | Main Uses | Sensitivity / Specificity | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transvaginal Ultrasound (TVUS) | First-line evaluation of adnexal masses. Assessment of morphology and vascularization. | Sensitivity: ~85% / Specificity: ~90% (for mass characterization) | Widely available, non-invasive, no radiation. High-resolution for pelvic organs. | Operator-dependent. Limited for staging and evaluation of peritoneal spread. |

| Computed Tomography (CT) | Staging (especially peritoneal, nodal, and distant metastases). Preoperative planning. | Sensitivity: ~70–85% / Specificity: ~90% (for staging) | Good overview of abdomen and pelvis. Useful for surgical planning and monitoring recurrence. | Limited soft tissue contrast. Poor detection of small peritoneal implants (<1 cm). |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Characterization of indeterminate masses. Local staging. Evaluation of complex cystic lesions. | Sensitivity: ~93% / Specificity: ~88–98% | Excellent soft tissue contrast. No radiation. Functional imaging (DWI) adds value in lesion analysis. | More expensive, time-consuming. Contraindicated in patients with certain implants. |

| FDG-PET/CT | Detection of recurrence, metastases. Useful in equivocal cases. | Sensitivity: ~80–95% / Specificity: ~90–95% (in recurrence) | Functional and anatomical data. High sensitivity in detecting active disease and distant spread. | Limited role in primary diagnosis. False positives in inflammation/endometriosis. Costly. |

| PET/MRI (emerging) | Research setting. Combines metabolic and high-resolution anatomic data. | Under investigation | Potentially best of both PET and MRI. Promising for advanced imaging and radiomic studies. | Limited availability. High cost. Not yet widely implemented in clinical practice. |

3.4. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Classification of lesions: although histopathological examination after biopsy is still considered the gold standard for discriminating benign from malignant lesions, deep learning algorithms (a subcategory of machine learning) can classify ovarian lesions as either benign or malignant with greater accuracy than traditional techniques used by radiologists. Li et al [40] described a radiomics model capable of differentiating malignant and benign ovarian lesions in CT images of about 143 patients. Good diagnostic accuracy has also been found in radiomics applied to MRI imaging, as described by Saida et al [41] and Wang et al [38]. In the latter study, DL algorithms were able to differentiate borderline ovarian lesions from malignant ones with higher accuracy than radiologists. Also in the field of ultrasonography recent studies have demonstrated levels of diagnostic accuracy by DL algorithms comparable to O-RADS-US and experienced sonographers [42,43].

- Prediction of genetic alterations: as already well known, in patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer it is critical to establish whether the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes are mutated, since BRCA-mutated tumors are associated with increased chemosensitivity to platinum-based drugs resulting in increased PFS. [44] Despite Meier et al. found no significant correlation between radiomic features and BRCA mutational status [45], other authors were able to predict Ki-67 status by analyzing radiomic features derived from PET-CT images [46].

- Prediction of disease spread at diagnosis: AI can automate the process of image segmentation, i.e. the isolation and analysis of suspicious areas in medical images. This segmentation allows radiologists to focus more accurately and quickly on potentially pathological areas. In fact, although CE-CT is the gold standard for staging ovarian cancer, it has accuracy limitations in identifying small peritoneal implants (< 1 cm) and localizations in specific areas such as the small bowel and mesentery. In addition, lesions are often “unmeasurable” according to RECIST 1.1 criteria [47]. Several studies describe how AI can predict the presence of peritoneal carcinosis and lymph node metastasis in HGSOCs on both CT and MR imaging by integrating radiomics with both clinical and laboratory factors such as age and CA-125 blood-levels [48,49,50].

- Prediction of treatment response: the prediction of treatment response according to radiomics models deeply traces the analysis of the previously described intrinsic heterogeneity of the tumor and various microenvironments. It is evident that different “subclones” of tumor tissue exhibit varied responses to different drugs in relation to their histological and molecular features. Indeed, it has been shown that while the number of disease localizations at diagnosis correlates significantly with treatment response, there is no correlation between disease volume and therapy response [51]. Conversely, when combined with clinical and laboratory data, radiomic biomarkers have been found to accurately predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) [51,52]. Similarly, some studies based on ML and DL algorithms seem to be able to predict the probability of platinum-resistance of high-grade serous carcinoma [36,53]. Consequently, even in post-NACT imaging re-evaluations, any residual tumor and/or new disease localization can be accurately characterized by describing the microarchitecture and estimating the “subclone” of origin. The same applies to patients who are candidates for immunotherapy, in whom reduced intratumoral heterogeneity seems to be associated with better response [54].

- Prediction of Risk of Recurrence: Several studies have focused on estimating progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in order to identify patients at higher risk of recurrence [55]. Some studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between radiomic features in CT imaging and OS, specifically showing that lower tumor heterogeneity values are associated with higher OS [45,56]. Similarly, other studies have examined the relationship between CT radiomic features of ovarian masses [57,58] and peritoneal implants [56] and PFS, which has also been found to correlate with tissue heterogeneity. Rizzo et al. [57] demonstrated that three radiomic variables—specifically, the gray level run length matrix (GLRLM), 3D morphological features, and the gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM)—are significantly associated with disease progression at 12 months. According to Zagari et al., among the variables considered in their study that significantly correlated with PFS, shape and density appeared to have the strongest correlation [59]. Furthermore, high tumor tissue heterogeneity values have been associated with a higher risk of incomplete surgical resection (R≠0) in non-BRCA-mutated patients [45]. Conversely, Vargas et al. reported that lower heterogeneity values were associated with greater surgical resectability [56] and, consequently, with higher OS and PFS values [5]. The integration of PET radiomic features with CT features, in addition to clinical variables, further improves prognostic accuracy compared to models based solely on CT imaging [60]. Even in the context of MRI imaging, a nomogram based on radiomic features derived from MRI images, combined with clinical variables, has shown a good ability to identify patients at risk of disease recurrence [61].

- Integration with Other Data Sources: AI can combine information from different diagnostic modalities (e.g., imaging, clinical history and laboratory results) to provide a more comprehensive and precise overview of the patient’s condition. As previously mentioned, most of the studies cited have incorporated alongside imaging features clinical variables such as age, FIGO stage, serum CA-125 levels, and the presence of residual tumor. The integration of such data into ML and DL algorithms is essential for obtaining more accurate information and achieving higher levels of diagnostic precision (Figure 7).

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OC | Ovarian cancer |

| US | Ultrasound |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| PFS | Progression-Free Survival |

| OS | Overall Survival |

References

- Tavares, V.; Marques, I.S.; Melo, I.G.D.; Assis, J.; Pereira, D.; Medeiros, R. Paradigm Shift: A Comprehensive Review of Ovarian Cancer Management in an Era of Advancements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Gu, H.; Mao, Z.; Beeraka, N.M.; Zhao, X.; Anand, M.P.; et al. Global burden of gynaecological cancers in 2022 and projections to 2050. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Barroilhet, L.; Behbakht, K.; Berchuck, A.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Ovarian Cancer, Version 1.2019. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2019, 17, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Martín, A.; Harter, P.; Leary, A.; Lorusso, D.; Miller, R.E.; Pothuri, B.; et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti, A.; Ferrandina, M.G.; Vizzielli, G.; Pasciuto, T.; Fanfani, F.; Gallotta, V.; et al. Randomized trial of primary debulking surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (SCORPION-NCT01461850). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, R.F.; Timmerman, D.; Strachowski, L.M.; Froyman, W.; Benacerraf, B.R.; Bennett, G.L.; et al. O-RADS US Risk Stratification and Management System: A Consensus Guideline from the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System Committee. Radiology 2020, 294, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, D.; Van Calster, B.; Testa, A.; Savelli, L.; Fischerova, D.; Froyman, W.; et al. Predicting the risk of malignancy in adnexal masses based on the Simple Rules from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis group. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuri, S.; Jajoo, S.; Dewani, D. The International Ovarian Tumor Analysis-Assessment of Different Neoplasias in the Adnexa (IOTA-ADNEX) Model Assessment for Risk of Ovarian Malignancy in Adnexal Masses. Cureus, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, R.F.; Timmerman, D.; Benacerraf, B.R.; Bennett, G.L.; Bourne, T.; Brown, D.L.; et al. Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting Lexicon for Ultrasound: A White Paper of the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System Committee. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2018, 15, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, S.; Avesani, G.; Panico, C.; Manganaro, L.; Gui, B.; Lakhman, Y.; et al. Ovarian cancer staging and follow-up: Updated guidelines from the European Society of Urogenital Radiology female pelvic imaging working group. Eur. Radiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinagare, A.B.; Sadowski, E.A.; Park, H.; Brook, O.R.; Forstner, R.; Wallace, S.K.; et al. Ovarian cancer reporting lexicon for computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging developed by the SAR Uterine and Ovarian Cancer Disease-Focused Panel and the ESUR Female Pelvic Imaging Working Group. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 3220–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avesani, G.; Panico, C.; Nougaret, S.; Woitek, R.; Gui, B.; Sala, E. ESR Essentials: Characterisation and staging of adnexal masses with MRI and CT—Practice recommendations by ESUR. Eur. Radiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischerova, D.; Pinto, P.; Burgetova, A.; Masek, M.; Slama, J.; Kocian, R.; et al. Preoperative staging of ovarian cancer: Comparison between ultrasound, CT and whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI ( ISAAC study). Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 59, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Poncelet, E.; Jalaguier-Coudray, A.; Guerra, A.; Fournier, L.S.; Stojanovic, S.; et al. Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting Data System Magnetic Resonance Imaging (O-RADS MRI) Score for Risk Stratification of Sonographically Indeterminate Adnexal Masses. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1919896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Cozzi, A.; Dolciami, M.; Del Grande, F.; Scarano, A.L.; Papadia, A.; et al. O-RADS MRI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Performance and Category-wise Malignancy Rates. Radiology 2023, 307, e220795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, E.A.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Rockall, A.; Maturen, K.E.; Forstner, R.; Jha, P.; et al. O-RADS MRI Risk Stratification System: Guide for Assessing Adnexal Lesions from the ACR O-RADS Committee. Radiology 2022, 303, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, B.C.; Hosseinzadeh, K.; Qasem, S.A.; Varner, A.; Leyendecker, J.R. Practical Approach to MRI of Female Pelvic Masses. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014, 202, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, L.R.; Freitas, L.B.; Rosa, D.D.; Silva, F.R.; Silva, L.S.; Birtencourt, L.T.; et al. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in ovarian tumor: A systematic quantitative review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, e1–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazot, M.; Daraï, E.; Nassar-Slaba, J.; Lafont, C.; Thomassin-Naggara, I. Value of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for the Diagnosis of Ovarian Tumors: A Review. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2008, 32, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forstner, R.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Cunha, T.M.; Kinkel, K.; Masselli, G.; Kubik-Huch, R.; et al. ESUR recommendations for MR imaging of the sonographically indeterminate adnexal mass: An update. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 2248–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Aubert, E.; Rockall, A.; Jalaguier-Coudray, A.; Rouzier, R.; Daraï, E.; et al. Adnexal Masses: Development and Preliminary Validation of an MR Imaging Scoring System. Radiology 2013, 267, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, D.; Valentin, L.; Bourne, T.H.; Collins, W.P.; Verrelst, H.; Vergote, I. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: A consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) group. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 16, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Belghitti, M.; Milon, A.; Abdel Wahab, C.; Sadowski, E.; Rockall, A.G.; et al. O-RADS MRI score: Analysis of misclassified cases in a prospective multicentric European cohort. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 9588–9599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, C.; Rockall, A.; Sadowski, E.A.; Siegelman, E.S.; Maturen, K.E.; Vargas, H.A.; et al. Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting Lexicon for MRI: A White Paper of the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data Systems MRI Committee. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2021, 18, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Dabi, Y.; Florin, M.; Saltel-Fulero, A.; Manganaro, L.; Bazot, M.; et al. O-RADS MRI SCORE: An Essential First-Step Tool for the Characterization of Adnexal Masses. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 59, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, V.; Dabi, Y.; Jalaguier-Coudray, A.; Stojanovic, S.; Millet, I.; Reinhold, C.; et al. How to improve O-RADS MRI score for rating adnexal masses with cystic component? Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 5943–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottat, N.A.; Van Pachterbeke, C.; Vanden Houte, K.; Denolin, V.; Jani, J.C.; Cannie, M.M. Magnetic resonance scoring system for assessment of adnexal masses: Added value of diffusion-weighted imaging including apparent diffusion coefficient map. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganaro, L.; Ciulla, S.; Celli, V.; Ercolani, G.; Ninkova, R.; Miceli, V.; et al. Impact of DWI and ADC values in Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System (O-RADS) MRI score. Radiol Med (Torino) 2023, 128, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, H.; Panico, C.; Ursprung, S.; Simeon, V.; Chiodini, P.; Frary, A.; et al. Non-contrast MRI can accurately characterize adnexal masses: A retrospective study. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 6962–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyoshi, H.; Tsujikawa, T.; Yamada, S.; Okazawa, H.; Yoshida, Y. Diagnostic value of [18F]FDG PET/MRI for staging in patients with ovarian cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2020, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenzer, N.F.; Schmidt, H.; Gatidis, S.; Brendle, C.; Müller, M.; Königsrainer, I.; et al. Measurement of apparent diffusion coefficient with simultaneous MR/positron emission tomography in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis: Comparison with 18F-FDG-PET. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2014, 40, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, M.; Lovrec, P.; Sadowski, E.A.; Pirasteh, A. PET/MRI in Gynecologic Malignancy. Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 2023, 61, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panico, C.; Avesani, G.; Zormpas-Petridis, K.; Rundo, L.; Nero, C.; Sala, E. Radiomics and Radiogenomics of Ovarian Cancer. Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 2023, 61, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Chang, X.; Hu, W.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Single-Cell Dissection of the Multiomic Landscape of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3903–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Cosgrove, P.A.; Mirsafian, H.; Christie, E.L.; Pflieger, L.; Copeland, B.; et al. Evolution of core archetypal phenotypes in progressive high grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, H.; Vargas, H.; Jimenez-Sanchez, A.; Micco, M.; Mema, E.; Lakhman, Y.; et al. Integrated Multi-Tumor Radio-Genomic Marker of Outcomes in Patients with High Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, B.; Vargas, H.A.; Selenica, P.; Geyer, F.C.; Mazaheri, Y.; Blecua, P.; et al. Radiogenomics Analysis of Intratumor Heterogeneity in a Patient With High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, W.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Advances in artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 51, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamikia, S.; Nougaret, S.; Panico, C.; Avesani, G.; Nero, C.; Boldrini, L.; et al. Ovarian cancer beyond imaging: Integration of AI and multiomics biomarkers. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2023, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Pang, P.; Lei, P.; Zou, H.; et al. A radiomics approach for automated diagnosis of ovarian neoplasm malignancy in computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saida, T.; Mori, K.; Hoshiai, S.; Sakai, M.; Urushibara, A.; Ishiguro, T.; et al. Diagnosing Ovarian Cancer on MRI: A Preliminary Study Comparing Deep Learning and Radiologist Assessments. Cancers 2022, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zeng, S.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Yao, S.; Song, K.; et al. Deep learning-enabled pelvic ultrasound images for accurate diagnosis of ovarian cancer in China: A retrospective, multicentre, diagnostic study. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, B.-W.; Qian, L.; Meng, Y.-S.; Bai, X.-H.; Hong, X.-W.; et al. Deep Learning Prediction of Ovarian Malignancy at US Compared with O-RADS and Expert Assessment. Radiology 2022, 304, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, S.S. Effect of Screening on Ovarian Cancer Mortality: The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2011, 305, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Nougaret, S.; Lakhman, Y.; Sosa, R.; Soslow, R.A.; et al. Association between CT-texture-derived tumor heterogeneity, outcomes, and BRCA mutation status in patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 2040–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Grzegorzek, M.; Sun, H. Habitat radiomics analysis of pet/ct imaging in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: Application to Ki-67 status and progression-free survival. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 948767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, F.V.; Choi, P.H.; Gougoutas, C.A.; Pothuri, B.; Venkatraman, E.; Chi, D.; et al. Peritoneal Metastases: Detection with Spiral CT in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Radiology 2002, 223, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.-L.; Ren, J.-L.; Yao, T.-Y.; Zhao, D.; Niu, J. Radiomics based on multisequence magnetic resonance imaging for the preoperative prediction of peritoneal metastasis in ovarian cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 8438–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Ren, J.; Jia, Y.; Wu, H.; Niu, G.; Liu, A.; et al. Multiparameter MRI Radiomics Model Predicts Preoperative Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 765652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Jin, X. Preoperative Prediction of Metastasis for Ovarian Cancer Based on Computed Tomography Radiomics Features and Clinical Factors. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 610742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispin-Ortuzar, M.; Woitek, R.; Reinius, M.A.V.; Moore, E.; Beer, L.; Bura, V.; et al. Integrated radiogenomics models predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundo, L.; Beer, L.; Escudero Sanchez, L.; Crispin-Ortuzar, M.; Reinius, M.; McCague, C.; et al. Clinically Interpretable Radiomics-Based Prediction of Histopathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 868265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Xiang, W.; Deng, A.; Fu, Y.; et al. Incorporating SULF1 polymorphisms in a pretreatment CT-based radiomic model for predicting platinum resistance in ovarian cancer treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 111013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himoto, Y.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Zheng, J.; Zamarin, D.; Snyder, A.; Capanu, M.; et al. Computed Tomography–Derived Radiomic Metrics Can Identify Responders to Immunotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Manganaro, L.; Dolciami, M.; Gasparri, M.L.; Papadia, A.; Del Grande, F. Computed Tomography Based Radiomics as a Predictor of Survival in Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, H.A.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Micco, M.; Nougaret, S.; Lakhman, Y.; Meier, A.A.; et al. A novel representation of inter-site tumour heterogeneity from pre-treatment computed tomography textures classifies ovarian cancers by clinical outcome. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Botta, F.; Raimondi, S.; Origgi, D.; Buscarino, V.; Colarieti, A.; et al. Radiomics of high-grade serous ovarian cancer: Association between quantitative CT features, residual tumour and disease progression within 12 months. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 4849–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liu, Z.; Rong, Y.; Zhou, B.; Bai, Y.; Wei, W.; et al. A Computed Tomography-Based Radiomic Prognostic Marker of Advanced High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Recurrence: A Multicenter Study. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargari, A.; Du, Y.; Heidari, M.; Thai, T.C.; Gunderson, C.C.; Moore, K.; et al. Prediction of chemotherapy response in ovarian cancer patients using a new clustered quantitative image marker. Phys. Med. Biol. 2018, 63, 155020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z. Radiomics Analysis of PET and CT Components of 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging for Prediction of Progression-Free Survival in Advanced High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 638124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Fang, M.; Zhu, C.; Gao, Y.; et al. A Nomogram Combining MRI Multisequence Radiomics and Clinical Factors for Predicting Recurrence of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 0 | Incomplete Evaluation [N/A] | N/A |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal Ovary [N/A] | Follicle defined as a simple cyst ≤ 3 cm; Corpus Luteum ≤ 3 cm |

| 2 | Almost Certainly Benign [<1%] | Simple cyst ≤ 3 cm |

| Simple cyst > 3 cm to 5 cm | ||

| Simple cyst > 5 cm but < 10 cm | ||

| Classic Benign Lesions (dermoid, endometrioma, etc…) | ||

| Non-simple unilocular cyst, smooth inner margin ≤ 3 cm | ||

| Non-simple unilocular cyst, smooth inner margin > 3 cm but < 10 cm | ||

| 3 | Low Risk Malignancy [1–<10%] | Unilocular cyst ≥ 10 cm (simple or non-simple) |

| Typical dermoid cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts ≥ 10 cm | ||

| Unilocular cyst (any size) with irregular inner wall < 3 mm height | ||

| Multilocular cyst < 10 cm, smooth inner wall, CS = 1–3 | ||

| Solid smooth, any size, CS = 1 | ||

| 4 | Intermediate Risk [10–<50%] | Multilocular cyst, no solid component, ≥ 10 cm, smooth inner wall, CS = 1–3 |

| Multilocular cyst, no solid component, any size, smooth inner wall, CS = 4 | ||

| Multilocular cyst, no solid component, any size, irregular inner wall and/or irregular septation, any color score | ||

| Unilocular cyst with solid component, any size, 0–3 papillary projections, CS = any | ||

| Multilocular cyst with solid component, any size, CS = 1–2 | ||

| Solid smooth, any size, CS = 2–3 | ||

| 5 | High Risk [≥ 50%] | Unilocular cyst, any size, ≥ 4 papillary projections, CS = any |

| Multilocular cyst with solid component, any size, CS = 3–4 | ||

| Solid smooth, any size, CS = 4 | ||

| Solid irregular, any size, CS = any | ||

| Ascites and/or peritoneal nodules |

| ADNEX MR SCORE | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. No mass | No mass |

| 2. Benign mass | Purely cystic mass Purely endometriotic mass Purely fatty mass Absence of wall enhancement Low b = 1000 sec/mm2 – weighted and low T2-weighted signal intensity within solid tissue |

| 3. Probably benign mass | Absence of solid tissue Curve type 1 within solid tissue |

| 4. Indeterminate MR mass | Curve type 2 within solid tissue |

| 5. Probably malignant mass | Curve type 3 within solid tissue Peritoneal implants |

| Non-contrast MRI score | Definition | MRI features |

|---|---|---|

| Score 1 | No mass | No adnexal mass is demonstrated in pelvic MRI study |

| Score 2 | Benign/likely benign | Radiologically characterized with radiological diagnosis (e.g. endometrioma, dermoid, fibroma) |

| Score 3 | Indeterminate | Not classified in other scores; it may have a solid appearing component without reaching criteria for “solid tissue” |

| Score 4 | Suspicious for malignancy | Solid tissue criteria reached |

| Score 5 | Highly suspicious for malignancy | Solid tissue criteria reached and presence of - Peritoneal implants - Lymphadenopathy and/or - Ascites in the presence of solid tissue, after benign diagnoses are excluded |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).