Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

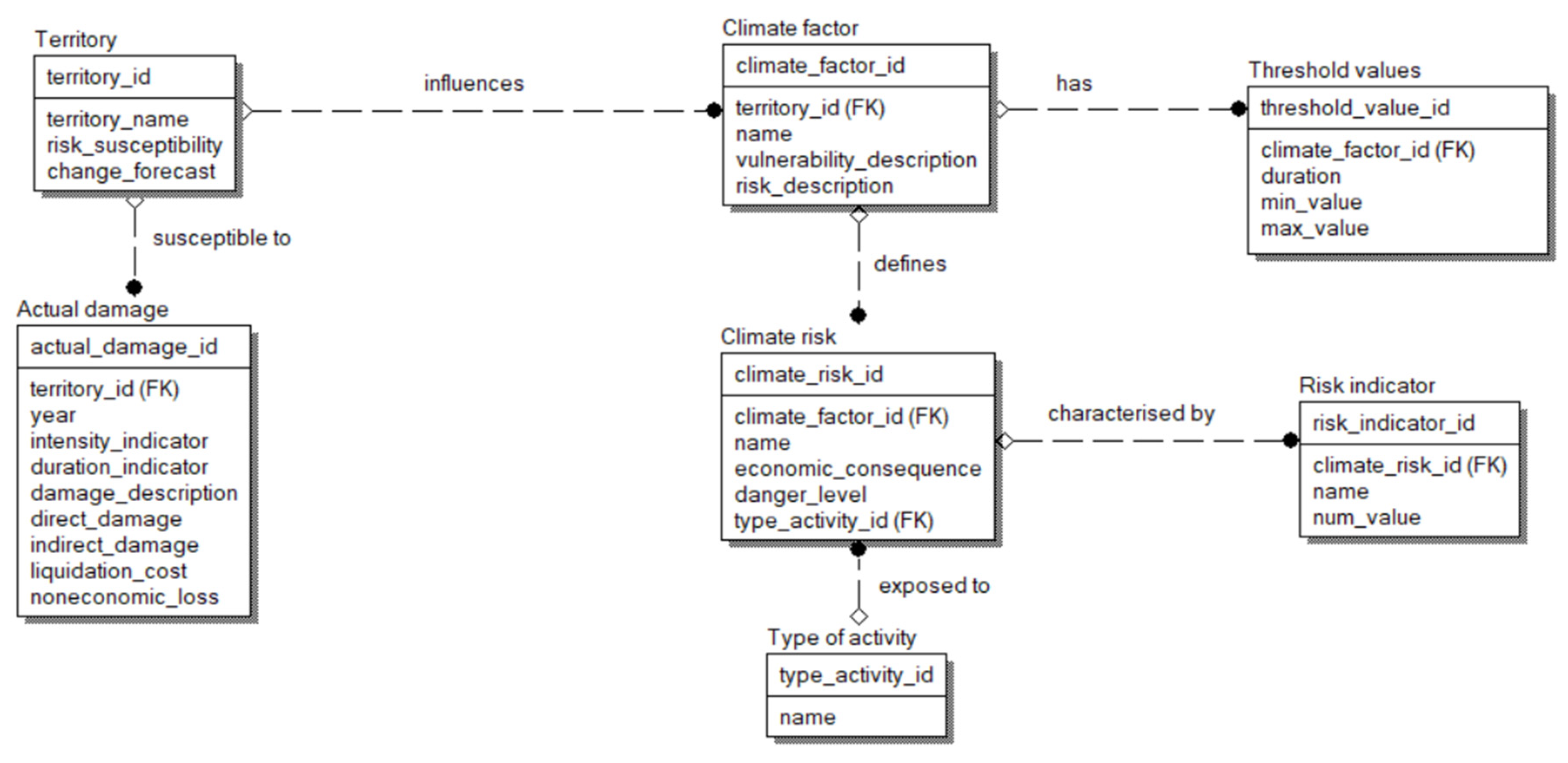

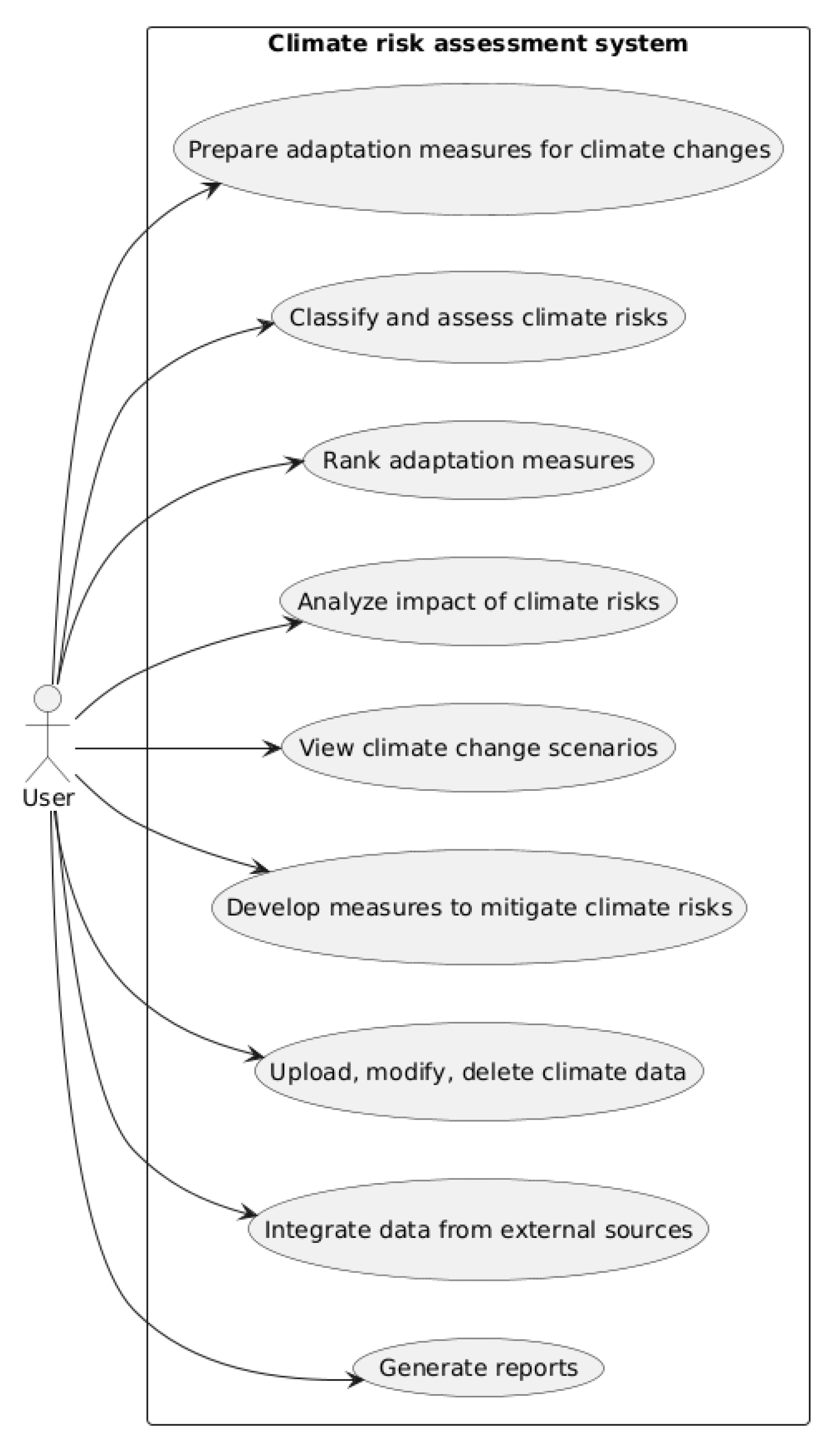

2. Materials and Methods

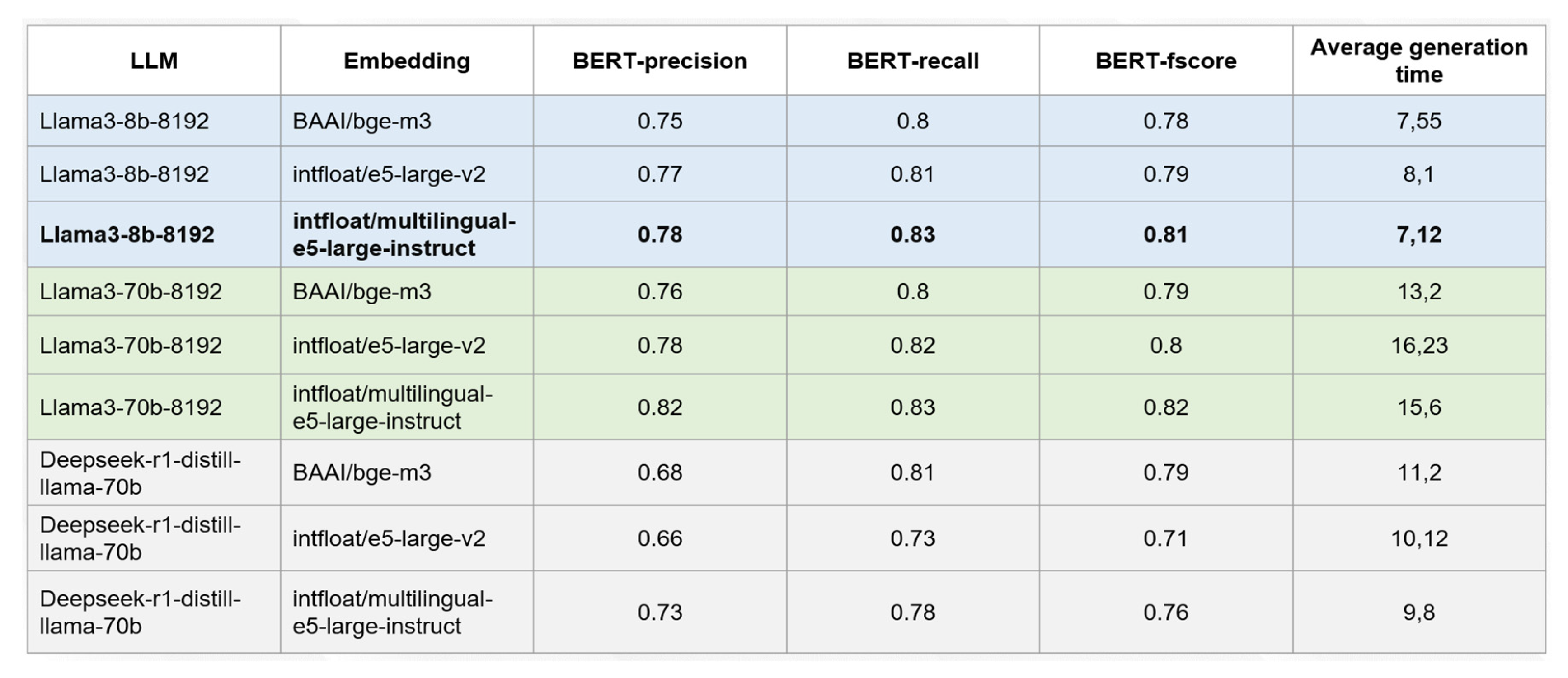

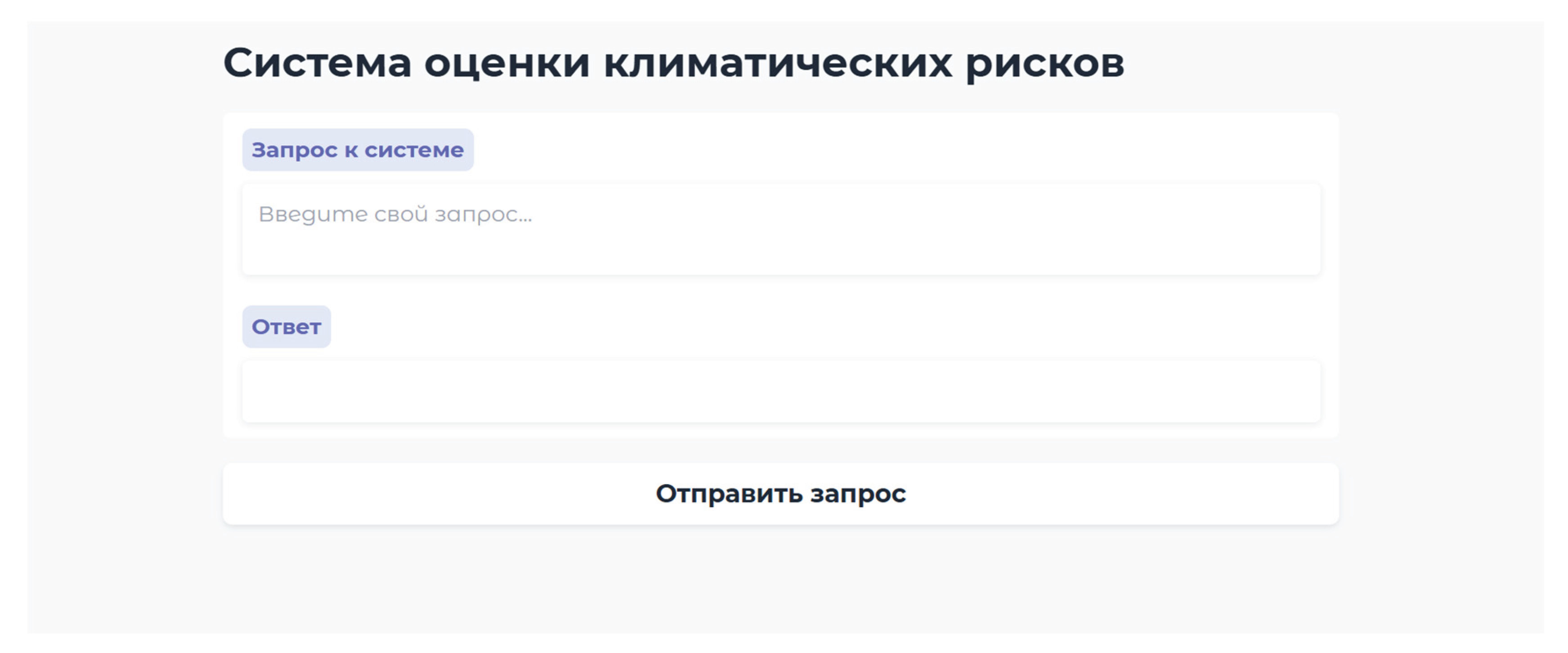

3. Results

4. Conclusions

References

- N. P. Simpson et al., “A framework for complex climate change risk assessment,” One Earth, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 489–501, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- NASA, “SOTO by Worldview,” nasa.gov. Accessed: Mar. 20, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://soto.podaac.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov/.

- NASA, “Sea Level Projection Tool,” nasa.gov. Accessed: Mar. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool#.

- NOAA, “Sea Level Rise Viewer,” coast.noaa.gov. Accessed: Mar. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://coast.noaa.gov/slr/#.

- IQAir, “Animated real-time air quality map,” iqair.com. Accessed: Mar. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/ru/air-quality-map.

- J. Ni et al., “CHATREPORT: Democratizing Sustainability Disclosure Analysis through LLM-based Tools,” 2023. arXiv:2307.15770.

- I.N. Glukhikh, T. Y. Chernysheva, and Y. A. Shentsov, “Decision support in a smart greenhouse using large language model with retrieval augmented generation,” in Proc. Third Int. Conf. Digital Technologies, Optics, and Materials Science (DTIEE 2024), Bukhara, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Ramdurai, “Large Language Models (LLMs), Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) in Application systems,” Int. J. Marketing and Technology, vol. 15, no. 01, Jan. 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2025/IJMT_JANUARY2025/IJMT1Jan2025.pdf.

- K. S. Izosimova, A. Y. Solovyeva, V. V. Popov, and T. Y. Chernysheva, “Using retrieval-augmented generation in book recommendation systems,” Informacionnye technologiy v obrazovaniy, vol. 7, pp. 120–125, Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=80287737.

- LlamaIndex, “LlamaIndex,” lamaindex.ai. Accessed: Apr. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.llamaindex.ai.

- R. K. Malviya, V. Javalkar, and R. Malviya, “Scalability and Performance Benchmarking of LangChain, LlamaIndex, and Haystack for Enterprise AI Customer Support Systems,” JGIS Fall of 2024 Conf., Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Groq, “Groq,” groq.com. Accessed: Apr. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://groq.com.

- Groq, “ArtificialAnalysis.ai LLM Benchmark Doubles Axis To Fit New Groq LPU Inference Engine Performance Results,” groq.com. Accessed: Mar. 29, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://groq.com/blog/artificialanalysis-ai-llm-benchmark-doubles-axis-to-fit-new-groq-lpu-inference-engine-performance-results.

- H. Yu, A. Gan, K. Zhang, S. Tong, Q. Liu, and Z. Liu, “Evaluation of Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Survey,” 2024. arXiv:2405.07437.

- T. Zhang, V. Kishore, F. Wu, K. Q. Weinberger, and Y. Artzi, “BERTScore: Evaluating Text Generation with BERT,” 2019. arXiv:1904.09675.

- Hugging Face, “meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B.

- Hugging Face, “meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-70B,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-70B (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Hugging Face, “deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B.

- Hugging Face, “BAAI/bge-m3,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/BAAI/bge-m3.

- Hugging Face, “intfloat/e5-large-v2,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/intfloat/e5-large-v2.

- Hugging Face, “intfloat/multilingual-e5-large-instruct,” huggingface.co. Accessed: Jul. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://huggingface.co/intfloat/multilingual-e5-large-instruct.

- Meta Research, “A library for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors,” github.com. Accessed: Jul. 27, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/faiss.

- R. Rabata, “FAISS vs Chroma? Let’s Settle the Vector Database Debate!” capellasolutions.com. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.capellasolutions.com/blog/faiss-vs-chroma-lets-settle-the-vector-database-debate.

- Gradio, “Gradio,” gradio.app. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://gradio.app/.

- Ministry of Economic Development of Russia, “Order No. 267, dated 13 May 2021, ‘On Approval of the Methodological Recommendations and Indicators on Adaptation to Climate Change’.”.

- M. L. Gillenson, Fundamentals of Database Management Systems, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2023.

- Bates, R. Vavricka, S. Carleton, R. Shao, and C. Pan, “Unified Modeling Language Code Generation from Diagram Images Using Multimodal Large Language Models,” 2025, arxiv:2503.12293.

- Abid, A. Abdalla, A. Abid, D. Khan, A. Alfozan, and J. Zou, “Gradio: Hassle-Free Sharing and Testing of ML Models in the Wild,” 2019, arxiv:1906.02569.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).