1. Introduction

Tyrosinase, a key enzyme responsible for melanin biosynthesis, plays an important role in the pigmentation of human skin, hair and eyes, as well as in the browning of fruits and vegetables. Excessive activity of this enzyme is associated with dermatological problems such as hyperpigmentation and with adverse effects in the food industry. Therefore, the search for effective tyrosinase inhibitors has become the subject of intensive research in the fields of medicine, cosmetology and food technology [

1].

Among the many compounds studied for tyrosinase inhibition, those containing ketone and hydroxyl groups draw special attention. These functional chemical groups enable effective chelation of copper ions present in the active center of the enzyme or access to catalytic site, which in both cases lead to the inhibition of its activity. Examples of such compounds are kojic acid, tropolone or α-hydroxyketones, which exhibit both competitive and mixed mechanisms of inhibition depending on the type of substrate and reaction conditions [

2].

This article discusses the mechanisms of action of tyrosinase inhibitors containing ketone and hydroxyl groups, with particular emphasis on their mode of interaction within the catalytic site, based on the results of molecular modeling. Additional attention is paid also to their role as depigmenting agents in cosmetology, antioxidants in food technology and potential drugs in the treatment of diseases associated with hyperpigmentation. The article also presents the prospects for the development of new inhibitors based on these chemical structures and the challenges associated with their use [

3].

One of the most dangerous skin disease connected with hyperpigmentation is melanoma characterized by high mortality, especially in advanced stages. The epidemiology of melanoma shows significant geographical differences, with the highest incidence in Australia and New Zealand, as well as in Scandinavian countries and North America. In recent decades, there has been an increase in the number of melanoma cases, which is associated with changes in lifestyle, including increased exposure to UV radiation. The main risk factor for the development of melanoma is exposure to UV radiation, both natural (sun) and artificial (solariums). Episodes of intensive tanning are particularly dangerous, especially in childhood and adolescence [

4].

Even for that single reason research on new tyrosinase inhibitors is becoming more and more important. It is focusing on designing compounds that will be even more effective, while maintaining low toxicity. The use of advanced computational chemistry techniques allows for precise modeling of interactions between ketone and hydroxyl groups and the active center of tyrosinase, which allows for the development of new, highly selective inhibitors. In recent years, there has been growing interest in finding new tyrosinase inhibitors of natural origin. Plants, fungi, and microorganisms are a rich source of potential inhibitors but thorough analysis of their mode of interaction can be very useful in designing of new synthetic compounds with improved efficacy and specificity of action [

5].

Tyrosinase inhibitors antagonise the activity of the enzyme tyrosinase, which controls the rate of melanin formation, leading to decreased melanin production in melanoma cells and potentially limiting tumor growth [

7]. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that tyrosinase inhibitors can not only inhibit melanin production but also can increase the sensitivity of melanoma cells to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, improving the efficacy of treatment. Compounds such as kojic acid, arbutin, and tropolone are being studied as potential anticancer drugs for melanoma therapy [

8]. In addition combination of tyrosinase inhibitors with other melanoma treatments is tested, e.g. with BRAF and MEK inhibitors [

9].

The role of ketone and hydroxyl groups

The ketone group (C=O) is particularly effective in chelating copper ions present in the active site of tyrosinase as well as being included in the hydrogen bonds network with aminoacids within the catalytic site. This disruption of the active site structure prevents the enzyme from catalyzing oxidative reactions, such as the conversion of L-tyrosine to L-DOPA or L-DOPA to dopaquinone [

10,

11]. An example of a compound that uses a keto group to inhibit tyrosinase is kojic acid (KA). Kojic acid has a mixed mechanism of tyrosinase inhibition, meaning that it can bind to both the active site of the enzyme and other allosteric sites. This property leads to a decrease in the maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) and an increase in the Michaelis constant (Km) [

10].

Hydroxyl groups (-OH) also play an important role in tyrosinase inhibition. They can form hydrogen bonds with amino acids in the active site of tyrosinase or interact directly with copper ions [

11,

12]. The number and position of hydroxyl groups in aromatic rings significantly affect activity of the inhibitor. Studies have shown that compounds with multiple hydroxyl groups, such as butein, exhibit stronger tyrosinase inhibition than compounds with single hydroxyl groups [

12]. This observation suggests that the presence of multiple hydroxyl groups may enhance the ability of the inhibitor to form stable complexes with the active site of the enzyme [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

With the aim to explore and compare the potential interactions of the synthesized compounds with the tyrosinase enzyme molecular docking studies were conducted. he three-dimensional structure of the target enzyme was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 5M8M) [

14]. FlexX docking program from the LeadIT 2.3.2 software package was chosen for the in-silico simulations due to its accuracy in predicting the native ligand’s binding position within the active site, with acceptable RMSD values. Additionally, FlexX’s capability to predict interactions with metal ions, which may be crucial for inhibition activity, was a key factor in its selection [

15]. The radius of the binding site was expanded from the standard 6.5 Å to 9 Å. The zinc ion located within the binding site was included in the simulation region. The structures of the investigated compounds were minimized using Avogadro software, applying molecular mechanics with the MMFF94 force field over 10,000 cycles [

16]. The native ligand, kojic acid, was utilized for the redocking validation procedure to confirm the reliability of the selected docking parameters [

17]. Additionally, tropolone, a known experimentally validated tyrosinase inhibitor, was included in the compound set [

18]. The docking scores obtained for kojic acid and tropolone were subsequently used as reference points for quantitative comparison with the synthesized compounds. Biovia Discovery studio visualizer v21.1 was used for the visualization of the obtained results.

The Gromacs software package implemented into the SibioLead server were used to perform molecular dynamics simulations [

19]. The complexes were carefully placed within a cubic simulation box and solvated using the SPC water model to mimic aqueous conditions. The force field AMBERSS9B was chosen for performing the simulations [

20]. The Na

+ and Cl

- ions were added to the system at a concentration of 0.15 M for neutralization. Energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm, consisting of 5000 steps to optimize the system’s potential energy landscape. Following minimization, the system was equilibrated under canonical (NVT) and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles at a constant temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 bar for 1000 ps. This equilibration phase prepared the system for the production run. The production phase of molecular dynamics was carried out over 100 ns using the Leapfrog integrator, with trajectory data collected as 5000 discrete frames for detailed analysis.

The binding free energy (ΔG binding) of protein-ligand complexes was calculated at 2-nanosecond intervals throughout the entire 100 ns simulation, resulting in 50 extracted frames from the GROMACS simulation. The estimates were obtained using an automated plugin for the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) method via the SiBioLead server. The results were subsequently analyzed and visualized using Microsoft Excel.

The frontier molecular orbitals, namely the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), were calculated using Spartan 24. The optimized structures obtained before were used for the calculations. Subsequently, geometry optimizations were performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the B3LYP hybrid functional and the 6-31G(d,p) basis set on the gas-phase optimized geometries [

21].

Following optimization, a single-point energy calculation was conducted at the same level of theory to obtain the molecular orbital energies. All orbital energies were retained in atomic units (a.u.; 1 a.u. = 1 Hartree = 27.2114 eV). The same unit system was used to derive and report the global reactivity descriptors—vertical ionisation potential (

I = −E

HOMO ), electron affinity (

A = −E

LUMO) [

22], chemical hardness (η = ΔE⁄2) [

23], global electronegativity (χ = (

I +

A)⁄2) [

24] and electrophilicity index (ω = χ²⁄2η) [

25] ensuring internal consistency and avoiding unit-conversion artefacts.

3. Results

The validation procedure confirmed the ability of the selected software and used parameters to reproduce the position of the ligands inside the binding site with a sufficient level of accuracy (RMSD = 1.252).

Docking studies revealed the big potential of the compound’s whole series because of the higher docking scores compared to the reference ligands. The best results showed the compound 6 with a 3-flourphenyl substituent.

Table 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Real and Predicted Positions of Kojic Acid in the Binding Site. A comparison between the experimentally determined position and the computationally predicted position of kojic acid within the active site of Tyrosinase-Related Protein 1 (TYRP1). The real position is based on crystallographic data, while the predicted position was obtained through molecular docking simulations. (b) 2D Interaction Scheme of Kojic Acid in the Binding Site. A schematic representation of the interactions between kojic acid and key residues in the TYRP1 binding site. This diagram was generated using the PDB structure 5M8M and visualized with Discovery Studio Visualizer. Interactions include hydrogen bonding between the hydroxy and keto groups of kojic acid and the residues in the active site, without direct coordination with the zinc ions.

Figure 1.

(a) Real and Predicted Positions of Kojic Acid in the Binding Site. A comparison between the experimentally determined position and the computationally predicted position of kojic acid within the active site of Tyrosinase-Related Protein 1 (TYRP1). The real position is based on crystallographic data, while the predicted position was obtained through molecular docking simulations. (b) 2D Interaction Scheme of Kojic Acid in the Binding Site. A schematic representation of the interactions between kojic acid and key residues in the TYRP1 binding site. This diagram was generated using the PDB structure 5M8M and visualized with Discovery Studio Visualizer. Interactions include hydrogen bonding between the hydroxy and keto groups of kojic acid and the residues in the active site, without direct coordination with the zinc ions.

Figure 2.

3D and 2D schemes of the interaction of Compound 12 with tyrosinase (PDB ID: 5M8M) .

Figure 2.

3D and 2D schemes of the interaction of Compound 12 with tyrosinase (PDB ID: 5M8M) .

Compound 12 forms hydrogen bond with Arg374, measuring 4.86 Å, and two strong hydrogen bonds with Arg321 with the short distances near 2.30 Å and 1.86 Å. The 3-fluoro substituent anchors in the cavity by three halogen non covalent interactions with Gln390, gly388 and Gly389. Additionally, Leu382 and His381 interact with the imidazo[1,2-a]imidazol-5-one and phenyl cores, further enhancing the binding stability of the ligand. The number of aminoacids interact with the ligand by weak van der Waals force.

It should be noted that there are no direct donor-acceptor interactions between the Zn ion and compounds. However, kojic acid and Tropolone also bind near the metal ions, approximately 3 Å away, which is too distant for effective coordination [30]. Despite the lack of direct coordination, their proximity to the zinc ions still allows them to interfere with the enzyme’s catalytic activity, contributing to their inhibitory effects. Therefore, the high docking scores, which exceed those of the reference ligands, suggest that the synthesized compounds may bind strongly to tyrosinase and compete with its natural substrates, such as tyrosine or DOPA, for access to the enzyme’s active site.

Considering that existing and potential tyrosinase inhibitors must physically hinder substrate entry into the enzyme’s active site, the stability of enzyme-inhibitor complexes is a key factor. Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the GROMACS software package for a simulation time of 100 ns, which is sufficient to evaluate the stability of the complexes. Additionally, molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using kojic acid as a reference molecule. The stability of both complexes was compared using standard parameters, including root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), the number of hydrogen bonds, and the radius of gyration (Rg).

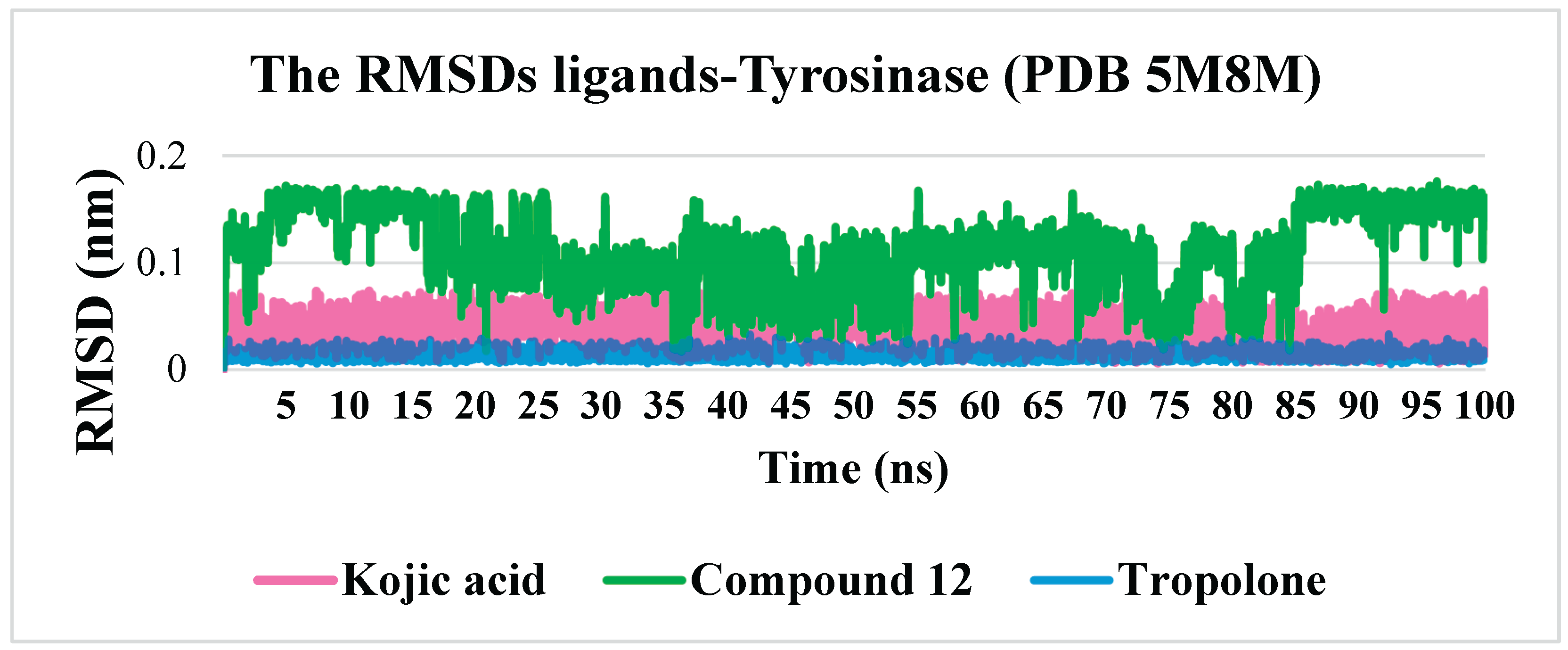

The RMSD values demonstrated a sufficient level of stability for the tyrosinase–compound 12 complex, as the RMSD did not exceed 0.3 nm. At its peak, the RMSD reached an average value of approximately 0.16 nm between 4–15 ns and 85–100 ns. Notably, the reference compounds, kojic acid and tropolone, exhibited exceptional complex stability, with RMSD values of approximately 0.05 nm and 0.015 nm, respectively. This remarkable stability is attributed to the planar structure of kojic acid and tropolone molecules, which have either a single torsion point or none (in the case of tropolone), thereby reducing molecular fluctuations after binding within the active site.

Figure 3.

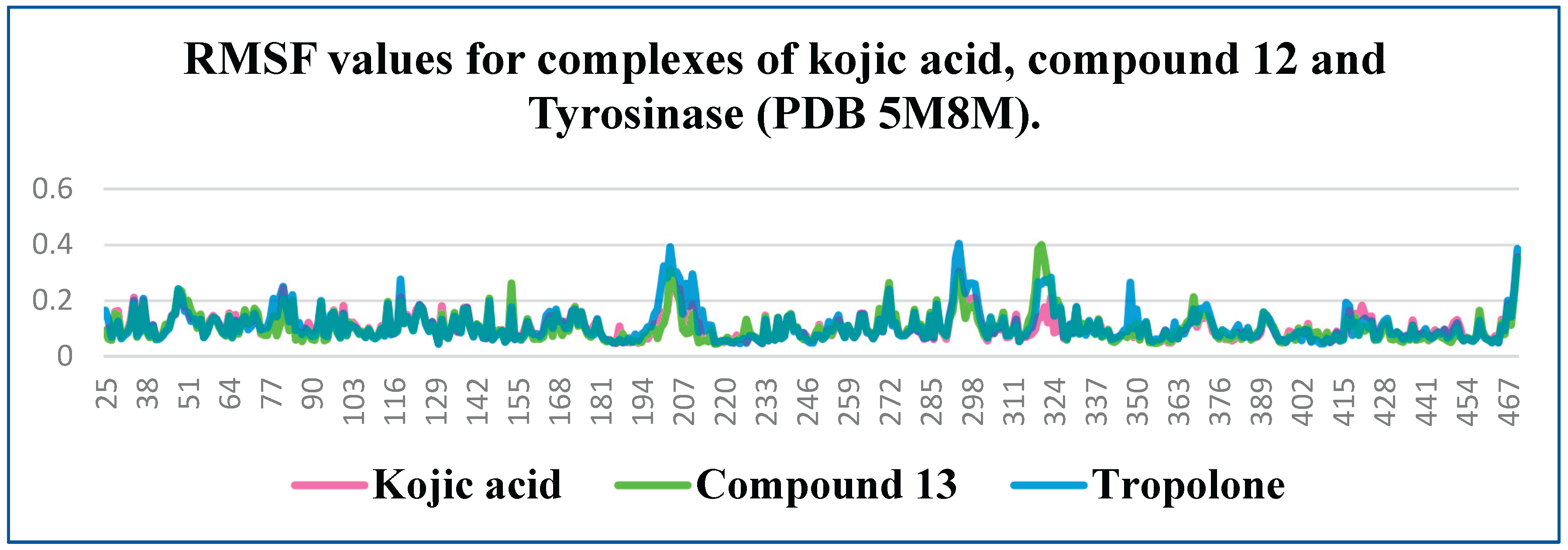

RMSF is a metric used to assess the average amplitude of atomic or residue-level fluctuations in a molecule during a molecular dynamics simulation. Typically, the C- and N-termini of proteins exhibit greater fluctuations compared to the core regions due to their higher flexibility. In contrast, secondary structure elements such as α-helices and β-sheets are generally more rigid and show lower fluctuations compared to disordered or unstructured regions of the protein.

In protein-ligand systems, low RMSF values in the binding region often indicate complex stability, as reduced fluctuations suggest that the ligand is firmly anchored within the active site. This relationship underscores the importance of RMSF analysis in understanding molecular flexibility and the dynamics of biomolecular interactions. RMSF plots reveal minor differences among all three complexes, particularly in the binding region (residues 360–391). This observation suggests comparable stability among the complexes.

Figure 4.

The protein RMSF of Tyrosinase in complex with the kojic acid (pink colored), Tropolone (blue colored) and compound 12 (green colored).

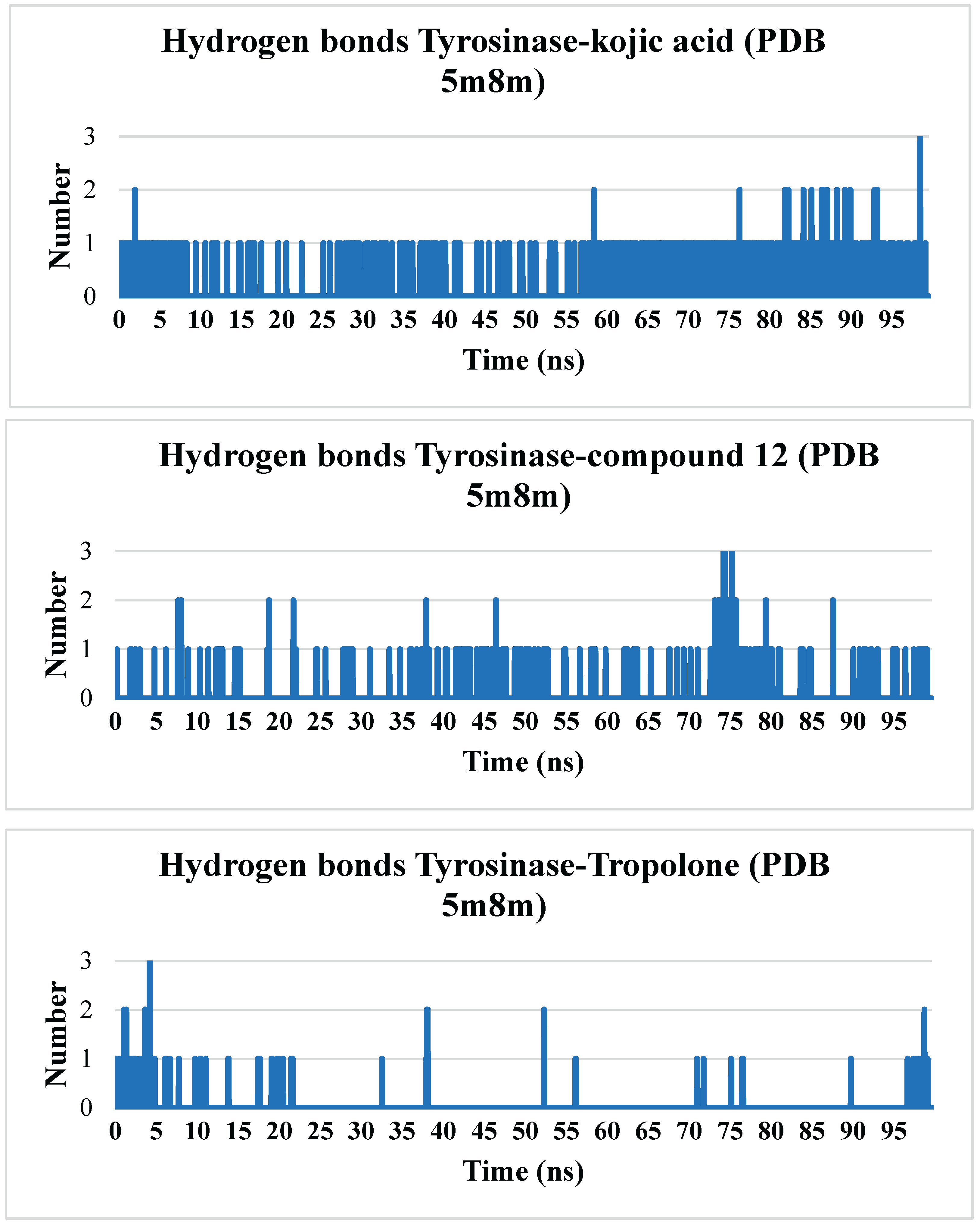

Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role in stabilizing protein structures and ligand-protein complexes. During molecular dynamics simulations, analyzing the number and stability of these bonds helps assess the strength of ligand-protein interactions, which serves as a key indicator of binding stability.

Hydrogen bonds between the ligand and protein help anchor the ligand in the active site or another specific protein region. A stable number of hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation indicates reliable binding.

Kojic acid and compound 12 form hydrogen bonds with the protein, but kojic acid maintains a more stable number of hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation. Compound 12 forms, on average, one to two hydrogen bonds, with intermittent periods where no hydrogen bonds are observed. Tropolone, owing to its simple single-phenyl core scaffold, typically does not form hydrogen bonds but occasionally forms one to three hydrogen bonds.

Figure 5.

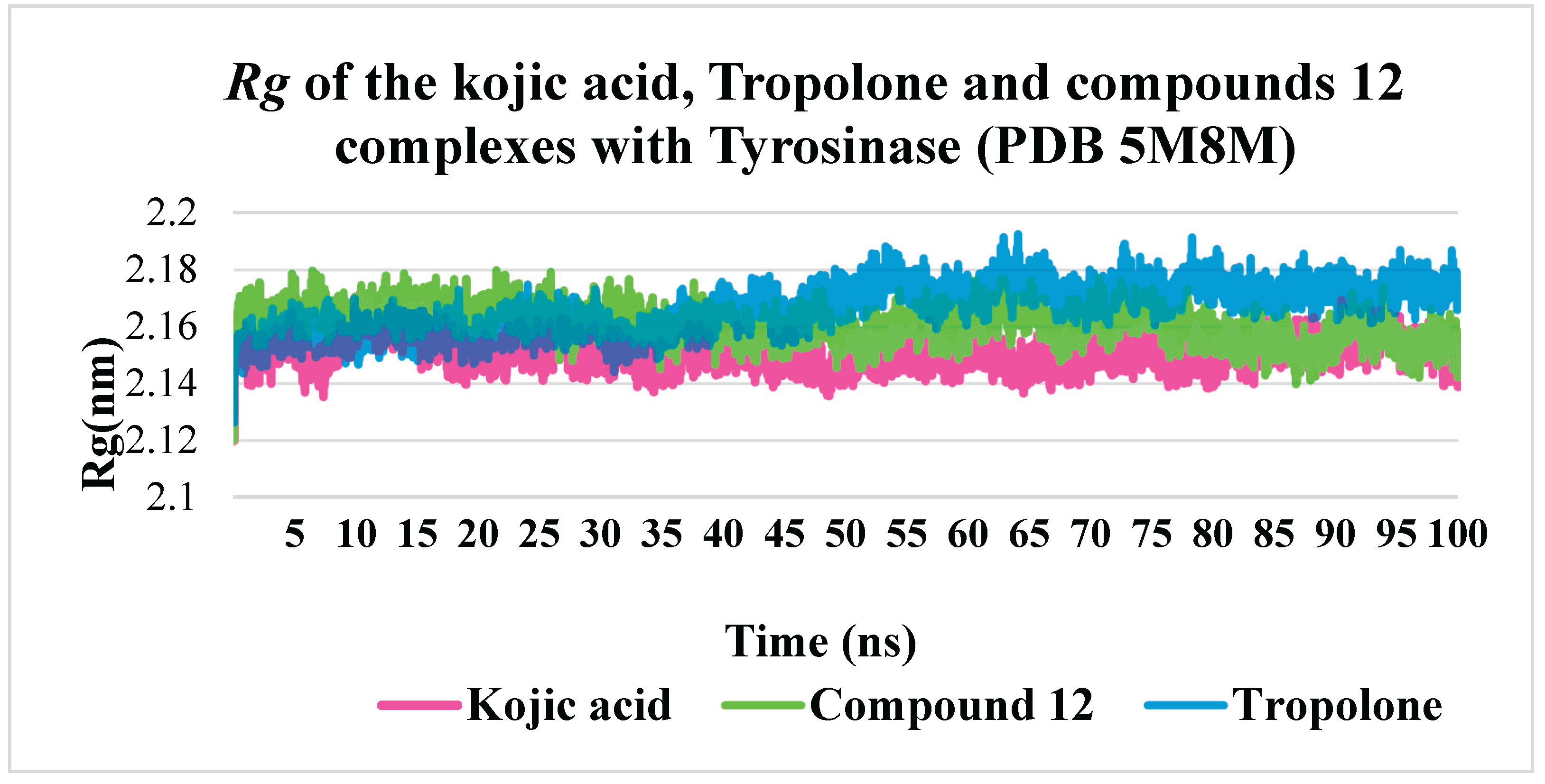

The radius of gyration (

Rg) quantitatively measures the compactness or spatial distribution of a molecule’s atoms relative to its center of mass. Consequently, the trajectory analysis of

Rg reflects changes in the overall dimensions of the protein throughout the molecular dynamics simulation. The average

Rg value for the kojic acid–tyrosinase complex was 2.15 nm, while the complex with compound 12 exhibited a slightly higher value (2.16–2.17 nm). Similarly, the tropolone–tyrosinase complex demonstrated comparable stability, with slightly elevated

Rg values from 50 ns onward. Ultimately, all three complexes remained stable over the 100 ns simulation period, indicating comparable compactness and stability under the given simulation conditions.

Figure 6.

Table 2.

MM-PBSA binding-energy decomposition for tyrosinase (PDB ID 5M8M) in complex with kojic acid, compound 12 and tropolone.

Table 2.

MM-PBSA binding-energy decomposition for tyrosinase (PDB ID 5M8M) in complex with kojic acid, compound 12 and tropolone.

| Complex |

ΔG |

Van der Waal energy |

Electrostatic energy |

Polar solvation energy |

Non-polar solvation energy |

Solvation Energy |

| 5M8M-kojic acid |

-13.41±2.92 |

-23.37±2.03 |

-5.41 ± 2.04 |

15.37 ± 3.31 |

-1.84 ± 0.04 |

15.36± 3.31 |

| 5M8M-Compound 12 |

-15.80±3.10 |

-25.70±2.10 |

-7.00 ± 2.10 |

18.60± 3.40 |

2.00 ± 0.08 |

16.60± 3.40 |

| 5M8M-Tropolone |

-11.50±2.20 |

-20.20±2.00 |

-3.40 ± 1.90 |

13.40 ± 2.50 |

-1.60 ± 0.26 |

11.80± 2.50 |

The MM-PBSA results indicate that compound 12 exhibits the most negative binding free energy, signifying its strong affinity for the tyrosinase active site. Van der Waals interactions contribute substantially to this enhanced binding, with electrostatic components also playing a key role. In contrast, tropolone shows a less negative free energy despite its planar structure and low RMSD values, suggesting fewer stabilizing hydrogen bonds. Kojic acid demonstrates moderate binding energy, reflecting a balance between electrostatic and solvation effects. Overall, these findings highlight the binding potential of compound 12, warranting further investigation as a tyrosinase inhibitor.

HOMO–LUMO Transition and Biological Activity

The calculated HOMO–LUMO energy gap, together with the derived reactivity descriptors, provides insight into the potential bioactivity of the proposed compounds. The HOMO level reflects the electron-donating capacity of the molecule, which is critical for coordinating with the metal center, while the LUMO indicates the ability to accept electrons from the enzymatic environment. A moderate HOMO–LUMO gap facilitates these interactions, potentially enhancing inhibitory potency.

In the present study, the HOMO–LUMO gaps (ΔE) lie between 0.147 and 0.184 a.u. (≈ 4.0 – 5.0 eV). Frontier-orbital and global-reactivity indices derived from our B3LYP calculations delineate clear electronic differences among compounds 1–13.

The HOMO–LUMO gaps span 0.147–0.184 a.u., corresponding to chemical hardness values (η = ΔE⁄2) of 0.074–0.092 a.u. and confirming that every molecule remains soft enough for ligand-to-metal charge transfer within the tyrosinase active site. Compound 2 shows the narrowest gap and lowest hardness, whereas compound 9 is the hardest member of the series. Ionisation potentials, approximated by −E_HOMO, fall between 0.206 and 0.228 a.u.; the smallest values for 2 and 5 mark them as the best electron donors. Electron affinities, taken as −E_LUMO, peak at 0.070 a.u. for 9 and exceed that of the reference kojic acid (0.040 a.u.) for all analogues, signalling an enhanced capacity to accept charge from the enzyme. The global electronegativity χ = (I + A)/2 reaches its maximum in 9 (0.149 a.u.) and minimum in 2 (0.132 a.u.), reflecting the donor–acceptor balance in each molecule. Most instructive is the electrophilicity index ω = χ²⁄2η, which integrates χ with hardness to estimate the stabilization energy achievable after electron uptake; here values range from 0.104 to 0.134 a.u. Compounds 8 (0.134 a.u.) and 6 (0.133 a.u.) top this scale, outperforming kojic acid (0.120 a.u.) by roughly 12%, whereas compound 7 is the least electrophilic (0.104 a.u.). The conjunction of high ω and moderate hardness predicts that 8 and 6 will most efficiently stabilise the Cu(I)–ligand charge-transfer state that underlies catalytic inhibition.

Compounds 1, 3, 10, 11 and 12 occupy an intermediate zone, displaying balanced donor–acceptor profiles that should support respectable inhibitory activity. By contrast, the rigidity and low electrophilicity of 7 and the excessive hardness of 9 are expected to diminish their binding efficiency.

Collectively, the descriptor pattern yields a predicted reactivity hierarchy of 8 ≈ 6 > 2 > 1 ≈ 3 ≈ 10 ≈ 11 ≈ 12 > 5 > 13 > 4 > 9 > 7.

Table 3.

Frontier-orbital energies and global reactivity descriptors for compounds 1–13 and kojic acid calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level; all values are given in atomic units (1 a.u. = 27.2114 eV).

Table 3.

Frontier-orbital energies and global reactivity descriptors for compounds 1–13 and kojic acid calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level; all values are given in atomic units (1 a.u. = 27.2114 eV).

| Compound |

E_HOMO (a.u.) |

E_LUMO (a.u.) |

ΔE (a.u.) |

η (a.u.) |

I (a.u.) |

A (a.u.) |

χ (a.u.) |

ω (a.u.) |

| 1 |

-0.22417 |

-0.06247 |

0.1617 |

0.08085 |

0.22417 |

0.06247 |

0.14332 |

0.12704 |

| 2 |

-0.2058 |

-0.0588 |

0.147 |

0.0735 |

0.2058 |

0.0588 |

0.1323 |

0.11907 |

| 3 |

-0.2205 |

-0.06247 |

0.15802 |

0.07901 |

0.2205 |

0.06247 |

0.14148 |

0.12668 |

| 4 |

-0.2205 |

-0.05512 |

0.16537 |

0.08269 |

0.2205 |

0.05512 |

0.13781 |

0.11484 |

| 5 |

-0.20947 |

-0.0588 |

0.15067 |

0.07534 |

0.20947 |

0.0588 |

0.13413 |

0.11941 |

| 6 |

-0.21682 |

-0.06615 |

0.15067 |

0.07534 |

0.21682 |

0.06615 |

0.14148 |

0.13286 |

| 7 |

-0.21682 |

-0.04777 |

0.16905 |

0.08452 |

0.21682 |

0.04777 |

0.1323 |

0.10354 |

| 8 |

-0.22785 |

-0.06615 |

0.1617 |

0.08085 |

0.22785 |

0.06615 |

0.147 |

0.13363 |

| 9 |

-0.22785 |

-0.06982 |

0.18375 |

0.09187 |

0.22785 |

0.06982 |

0.14883 |

0.12056 |

| 10 |

-0.22417 |

-0.06247 |

0.1617 |

0.08085 |

0.22417 |

0.06247 |

0.14332 |

0.12704 |

| 11 |

-0.21315 |

-0.06247 |

0.15067 |

0.07534 |

0.21315 |

0.06247 |

0.13781 |

0.12605 |

| 12 |

-0.21682 |

-0.06247 |

0.15435 |

0.07717 |

0.21682 |

0.06247 |

0.13965 |

0.12635 |

| 13 |

-0.2205 |

-0.0588 |

0.1617 |

0.08085 |

0.2205 |

0.0588 |

0.13965 |

0.1206 |

| Kojic acid |

-0.23152 |

-0.04042 |

0.15435 |

0.07717 |

0.23152 |

0.04042 |

0.13597 |

0.11979 |

E_HOMO—energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital; E_LUMO—energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; ΔE = E_LUMO − E_HOMO (band gap); η = ΔE/2 (chemical hardness, a measure of resistance to charge deformation); I = −E_HOMO (vertical ionisation potential, approximating electron-donor ability); A = −E_LUMO (vertical electron affinity, reflecting electron-acceptor strength); χ = (I + A)/2 (global electronegativity, overall tendency to attract charge); ω = χ² / (2η) (electrophilicity index, the energetic stabilisation achievable upon accepting electrons).

Figure 7.

HOMO, LUMO of the compound 6, 8, 12 and kojic acid.

Figure 7.

HOMO, LUMO of the compound 6, 8, 12 and kojic acid.

4. Conclusions

Comprehensive in-silico profiling has revealed the d library to be a fertile source of new tyrosinase inhibitors. Flexible docking identified ten of the thirteen synthesised molecules as energetically superior to the reference ligands, with compound 12 achieving the most favourable FlexX score -23.5156 and exhibiting an extensive hydrogen-bond/halogen-bond network within the 5M8M binding cleft. One-hundred-nanosecond molecular-dynamics simulations corroborated the reliability of the docking poses: the tyrosinase–12 complex remained structurally stable (RMSD ≤ 0.16 nm) and retained a compact global fold (Rg ≈ 2.16 nm) comparable to that of the kojic-acid complex. MM-PBSA analysis further ranked 12 as the strongest binder (ΔG= -15.8 ± 3.1 kcal mol⁻¹), with van-der-Waals and electrostatic components jointly dominating the interaction energy.

Frontier-orbital calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level showed HOMO–LUMO gaps of 0.147–0.184 a.u. for all analogues, confirming sufficient electronic softness for π → π* or n → π* charge transfer. Global reactivity descriptors singled out compounds 8 and 6 (ω ≈ 0.134 a.u.) as the most electrophilic, suggesting a strong propensity for Cu-centred redox interactions. Although 12 is electronically mid-ranking (ω = 0.126 a.u.), its superior shape complementarity and multivalent non-covalent contacts appear to offset this, yielding the most stable enzyme complex in silico.

Taken together, the data delineate two complementary optimisation avenues: (i) compound 12 as a lead whose favourable binding geometry can be fine-tuned to reinforce hydrogen-bond persistence, and (ii) compounds 8, 6 as electronically privileged scaffolds that merit structural elaboration aimed at enhancing steric fit. The convergence of docking, MD stability, free-energy estimations and quantum-chemical descriptors underscores the overall promise of the series and provides a rational basis for prioritising synthetic expansion and biochemical validation.

In summary, tyrosinase inhibitors, especially those containing ketone and hydroxyl groups, show significant potential in various fields. In cosmetology, their ability to reduce hyperpigmentation makes them valuable ingredients in skin care products. In the food industry, they can prevent undesirable enzymatic browning, improving the quality and shelf life of products. Most importantly, tyrosinase inhibitors show promising prospects in the treatment of melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer.

Melanoma is a major health problem worldwide, and its early detection and effective treatment are crucial to improve patient prognosis. Therefore, research on tyrosinase inhibitors that can inhibit melanoma cell growth and proliferation is extremely important. Compounds such as kojic acid, arbutin, and tropolone, due to their chelating and inhibitory properties, are promising candidates for anticancer drugs.

However, the development of effective melanoma therapies based on tyrosinase inhibitors requires further intensive research. Clinical trials are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of these compounds in melanoma patients. Furthermore, it is important to develop strategies that will overcome melanoma cell resistance to treatment and minimize potential adverse effects.

Future research should focus on:

Designing new tyrosinase inhibitors with better pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

Studying the mechanisms of action of tyrosinase inhibitors at the molecular and cellular level.

Evaluating the efficacy of combinations of tyrosinase inhibitors with other anticancer therapies, such as immunotherapy and targeted therapies.

Identifying biomarkers that will predict patient response to tyrosinase inhibitors.