1. Introduction

Software Defined Network (SDN) has emerged as a transformative paradigm in modern network architecture [

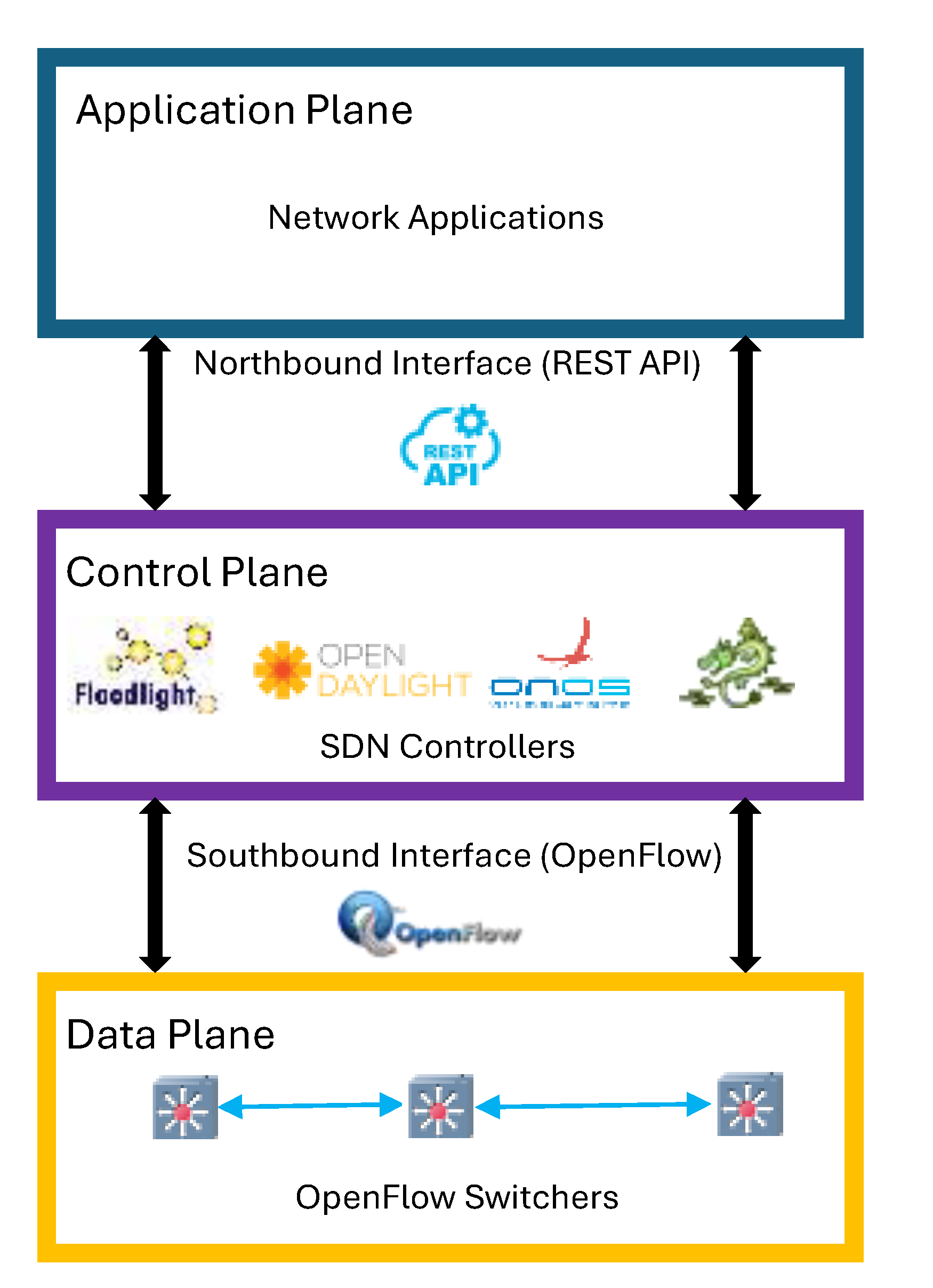

1]. Shown in

Figure 1, a typical simplified SDN architecture is organized into three functional layers: the data plane, control plane, and application plane. The data plane comprises OpenFlow-enabled switchers that serve as packet-forwarding devices. The control plane includes logically centralized SDN controllers, responsible for configuring and directing the operation of switchers in the data plane. The application plane contains network applications running. The decoupling of control and data plane simplifies network management and allows rapid deployment of network conditions [

2]. SDN enables real-time reconfiguration of flow rules through standardized southbound protocols such as OpenFlow [

3]. Northbound Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) of SDN architecture allow SDN controllers to programmatically influence network behaviors. These capabilities make SDN well-suited for complex environments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and energy systems.

Microgrid systems are increasingly recognized as vital components of the smart grid and the broader IoT energy ecosystem [

4]. Microgrid systems could enable efficient incorporation of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) into existing smart grids [

5]. Microgrid systems could also improve smart grid resilience, since they can function individually when needed [

6]. Microgrid systems rely on stable communications between distributed power sources, loads, and controllers for stable operations and real-time monitoring [

7,

8]. It is significant to secure the communications of microgrid systems to support advanced functions such as droop control [

9,

10]. Integrating SDN into microgrid systems provides a unified control framework for microgrid network communications. SDN provides dynamic path control and flexible network policy for operational efficiency and adaptability of microgrid systems [

11]. The coupling of SDN and microgrid systems also introduces novel attack surfaces to disrupt control flows, manipulate routing, and compromise microgrid stability [

12].

Studies have identified a range of attacks that can exploit SDN architecture’s centralized control and global visibility. Attackers can launch flow table overflow attacks to exhaust switch resources and packet-in flooding to overwhelm the SDN controller [

13]. Yoon et al. [

14] systematically examined the SDN attack surface and validated different attack vectors through experiments, covering the control plane, control channel, and data plane. These attacks, including control plane Denial of Service (DoS), switch table exhaustion, network topology poisoning, and control channel eavesdropping, threaten the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of SDN systems.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based intrusion detection and mitigation strategies have shown promise in addressing cyberattacks [

15]. In [

16], Yang et al. detected cyberattacks by applying offline learning combined with online analysis of transient processes in microgrid systems. Dehghani et al. [

17] employed deep learning techniques, Deep Auto-Encoders (DAE), to capture hidden signal features and detect False Data Injection (FDI) attacks. These methods are inherently data-driven, requiring high-quality and labeled Intrusion Detection System (IDS) datasets [

18]. Datasets are especially important for SDN-enabled microgrid systems, where both network layer and physical layer measurements need to be considered to detect intrusions.

A key issue in constructing IDS datasets is the privacy of benign and malicious data. Existing datasets have deployed strategies such as replaying traffic[

19], generating traffic directly using hardware appliances, simulating networks [

20], and emulating environments [

21]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and drawbacks. For SDN-enabled microgrid systems, the availability of realistic data is even more critical. Therefore, real-world SDN-enabled microgrid testbeds and activities are necessary to build realistic and effective datasets.

The motivation of this study is to develop a dataset that captures the full data of realistic SDN-enabled microgrid systems’ operations and communications. Currently, there is a lack of representative datasets constructed in realistic SDN-enabled microgrid testbeds. The proposed dataset includes real enterprise-level activities, microgrid communications, SDN control-plane and data-plane interactions, and diverse attack scenarios. This dataset provides a foundation for evaluating intrusion detection systems in SDN and microgrid environments. The effectiveness and explainability of AI-based detection models can also be improved by realistic and comprehensive IDS datasets.

The main contributions of this research are:

The development of a comprehensive and heterogeneous SDN-MG25 dataset constructed from a realistic SDN–microgrid testbed.

The proposed dataset integrates multiple heterogeneous data sources, including network traffic, SDN control information, system call traces, and microgrid power measurements.

The collected heterogeneous data are generated from realistic enterprise-level user activities and microgrid communications.

SDN-specific attack scenarios, such as fake link injection, flow rule tampering, and packet-in flooding, are implemented in an isolated environment.

A preliminary analysis of the dataset is provided to demonstrate its applicability for intrusion detection research in SDN-based microgrid environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of existing IDS datasets.

Section 3 describes the architecture and configuration of the proposed SDN–microgrid testbed.

Section 4 details the design of benign scenarios, including the enterprise-level user activities and microgrid operations.

Section 5 outlines the attack scenarios implemented in the testbed.

Section 6 presents a preliminary analysis of the collected dataset. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses potential future research directions.

2. Existing Datasets

A variety of IDS datasets have been developed to support the training and evaluation of intrusion detection systems using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Existing IDS datasets deploy multiple strategies to capture or generate data, including recording live data, replaying modified packet payloads [

19], synthetic traffic generation [

22], simulation [

20], and emulation [

21]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and drawbacks in scalability, coverage, and realism.

Most existing IDS datasets are primarily focused on conventional network environments and lack consideration for cyber-physical domains such as microgrid systems, particularly those operating under SDN architectures. Capturing realistic data of SDN-based microgrid systems is challenging due to the heterogeneous nature of the required data sources. The ideal dataset should include enterprise-level user activity traffic, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) communications, system call traces, SDN control-plane events, and microgrid power measurements.

To provide a structured overview of the current landscape, existing IDS datasets can be categorized according to their primary focus areas and intended application scenarios as follows:

2.1. SDN Datasets

SDN-IoT (2020) [

23]: This dataset targets intrusion detection in IoT-based SDN network environments and is built using Mininet and the Ryu controller with malicious traffic generated by hping3 and Slowloris.

InSDN (2020) [

24]: This dataset is designed specifically for SDN environments, capturing diverse attack vectors across the data, control, and application planes. It includes network traffic generated from a virtualized SDN testbed with attacks such as DoS, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), Web, User to Root (U2R), Botnet, and brute-force

SDN-SlowRate-DDoS (2023) [

25]: This dataset is designed for detecting slow-rate DDoS attacks in SDN, including SlowHTTP, SlowTCP, and SlowUDP. It is generated using the Mininet simulator.

SDNFLow (2024) [

13]: SDNFlow is an OpenFlow-based intrusion detection dataset for SDN. SDNFlow supports the evaluation of machine learning methods such as K-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) in detecting DDoS and port scan attacks.

HLD-DDoSDN (2024) [

26]: HLD-DDoSDN dataset targets the evaluation of high and low-rate DDoS flooding attacks, including TCP, UDP, and ICMP against SDN controllers, reflecting diverse traffic fluctuation scenarios.

SDN-DDoS-IoT (2025) [

27]: This dataset is an SDN-IoT dataset comprising eight types of DDoS attacks and normal traffic, generated using Mininet and Ryu with the OpenFlow protocol. It simulates various IoT scenarios, enabling robust evaluation of machine learning models against both high-rate and low-rate DDoS attacks in SDN-IoT environments.

2.2. IoT Datasets

TON-IoT (2020) [

28,

29]: This dataset supports the assessment of AI-driven cybersecurity solutions, with a focus on both IoT and Industrial IoT (IIoT) contexts. It comprises records from IoT devices, data from Windows and Linux operating systems, and network traffic, all sourced from a realistic Industry 4.0 environment.

CIC IoT (2023) [

30]: This dataset was collected from 33 types of attacks, classified into seven categories: DDoS, DoS, Recon, Web, Brute-force, Spoofing, and Mirai. Launched by malicious IoT devices against other IoT devices on a topology containing 105 real IoT devices, this dataset emphasizes IoT attacking IoT and large-scale real-world scenarios.

CIC IoV (2024) [

31]: CICIoV2024 dataset was performed on a 2019 Ford production vehicle. CAN-BUS communication within the vehicle is collected via OBD-II, including normal traffic and five types of attacks (DoS, steering wheel, RPM, speed, and throttle spoofing), more closely resembling real IoV threat scenarios.

CIC IoT-DIAD (2024) [

32]: This dataset targets device identification and anomaly detection within dynamic IoT settings. It is constructed from authentic HTTPS traffic sourced from seven categories of IoT devices. The dataset features include HTTPS-specific attributes, TLS handshake details, and User-Agent strings to support device classification, along with stream-level metrics like channel behavior and jitter for detecting anomalies.

2.3. Specialized Datasets

ADFA IDS (2014) [

33,

34]: Designed for host-based intrusion detection systems on both Linux and Windows platforms, this dataset captures system call sequences linked to different types of attacks. Although it serves as a reference for threat detection, some malicious behaviors in the dataset closely resemble normal system activities.

TSE-DS (2022) [

35]: This microgrid dataset presents stealthy FDI attacks crafted using a nonlinear AC model. The proposed dataset is based on a case study of the Western System Coordinating Council (WSCC) nine-bus microgrid system and aims to support the development of advanced FDI detection algorithms.

UNSW-MG24 (2025) [

22]: UNSW-MG24 is a realistic cybersecurity dataset designed for microgrid environments, capturing normal communication behaviors and various attack types across four different departments. It combines synthetic enterprise-level user activities, microgrid control protocols, and pivoting-based attacks, offering high diversity for microgrid security research.

2.4. Comparison with Existing Datasets

Existing datasets have established baselines for AI–based intrusion detection, but most datasets were generated in general simulation or emulation scenarios. Few datasets focus on the cyber-physical characteristics of microgrid systems supported by SDN architecture. Models validated using these datasets may face limitations when migrated to microgrid systems. In particular, datasets that rely on synthetic profiles, traffic replay, or single-layer trace data provide limited support for integrating all information in evaluations.

The proposed SDN-MG25 dataset addresses these gaps by instrumenting a realistic SDN-based microgrid testbed and collecting heterogeneous data. Benign traffic is produced by enterprise-level user activities, such as emailing, web browsing, and videoing. Besides, microgrid control communications using SCADA and Energy Management Systems (EMS) are implemented in an SDN network architecture. The infrastructure is an SDN deployment with an SDN controller and OpenFlow-capable switches, enabling the capture of control and data plane events. In addition to network flow records, the SDN-MG25 dataset includes system call traces and microgrid power measurements, offering heterogeneous data.

Compared with existing datasets [

22,

26], SDN-MG25 distinguishes itself by deploying a live SDN–microgrid testbed. Built on a physical and operational SDN-based microgrid system, it captures routine operation data together with SDN control information. The proposed dataset includes power measurements, SCADA traffic, SDN control information, and host-level system call traces. All streams are time-aligned, enabling cross-layer analysis of causes and effects. By unifying real enterprise traffic, microgrid control communications, system call traces, and SDN control information within a single SDN-based testbed, the proposed dataset provides a benchmark for developing and validating intrusion detection systems for SDN-based microgrid systems.

3. Experimental Testbed Architecture

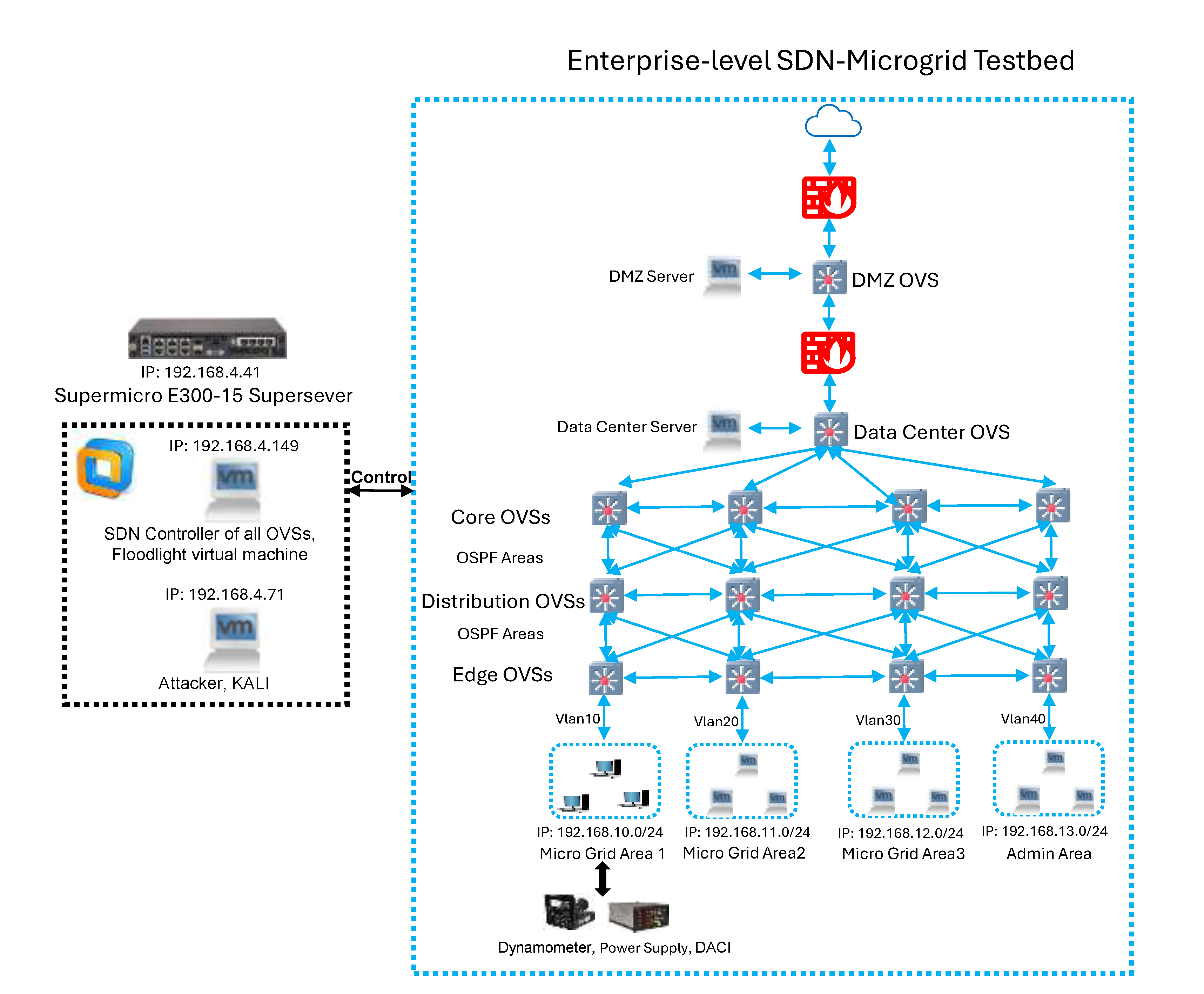

This section outlines the experimental platform used to collect the proposed SDN-MG25 dataset shown in

Figure 2. This testbed couples a physical microgrid system with an SDN architecture to reflect real operations in an enterprise-level environment. All devices and networks within this testbed are isolated in the specifically designed “Microgrid” network for safety and reproducibility. VMware Workstation is installed on a Supermicro E300-15 Superserver running Ubuntu as the host operating system, with the host IP address 192.168.4.41. VMware Workstation hosts two key virtual machines in bridged mode: the Floodlight SDN controller (IP addresses: 192.168.4.149) and the Kali attack machine (IP addresses: 192.168.4.71). Bridged mode allows these virtual machines to reside in the same subnet as the host, enabling direct control and management communications.

Building on the host/controller setup, all Open vSwitchers (OVSs) are deployed on the Ubuntu host of the Superserver and are centrally managed by the Floodlight controller. OVSs function purely as data-plane forwarding elements controlled by the Floodlight SDN controller and are not assigned Layer 3 IP addresses. The enterprise-level SDN network adopts a three-layer OVS topology, including Edge, Distribution, and Core, with four distinct OVSs in each layer. All OVSs are orchestrated by the Floodlight SDN controller, which computes logical Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) Areas using Dijkstra algorithms. Upstream, a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) OVS and a Data Center OVS sit behind two stages of firewalls to interface with external services.

On the service side, traffic is segmented into four subnet regions: Micro Grid Area 1/2/3 (IP addresses: 192.168.10.0/24, 192.168.11.0/24, 192.168.12.0/24) and an Admin Area (IP addresses: 192.168.13.0/24). Microgrid areas generate authentic SCADA and EMS communications that traverse the SDN architecture, allowing microgrid communications to be recorded. Within the service segmentation, hosts in Micro Grid Area 1 are Windows workstations connected to Superserver’s OVSs. These machines run SCADA and EMS software and interface directly with the electrical layer, including the four-quadrant dynamometer/power supply and Data Acquisition and Control Interface (DACI) modules. The electrical layer consists of standard microgrid hardware, including three-phase Pulse-Width Modulation (PWM) inverters, a synchronous machine, a four-quadrant dynamometer, a power supply, filters, DACI modules, and resistive loads. Micro Grid Area 2/3 each contains Windows virtual machines in VMware Workstation that execute SCADA and EMS software in a non-hardware-connected mode. These machines do not connect to physical microgrid devices directly, but they operate a three-phase grid-tied microgrid configuration in EMS software to produce realistic control and communication data. Machines in the Admin Area carry enterprise-level user activities such as emailing, web browsing, and videoing. Because all regions share the same SDN control, the dataset records synchronized control-plane states and data-plane data, enabling cross-layer analysis under a genuine SDN deployment. The proposed dataset was collected in this testbed over 10 days.

4. Benign Scenarios

Common approaches for designing benign scenarios include replaying previously captured traces, generating simulated traffic, and synthesizing traffic. These methods described in

Section 2 are data-rich but lack scenario control and realism. Besides, these benign scenarios can raise privacy concerns and miss the nuances of real user behaviors. Compared with prior work that relies on traffic replay [

23], packet generators [

36], and synthetic models [

22], the benign data of the proposed SDN-MG25 dataset is recorded based on real user activities and microgrid operations on a live SDN-microgrid testbed described in

Section 3. Enterprise-level benign scenarios originate from enterprise-level real user activities and microgrid control communications. All benign activities are performed in a Floodlight-controlled SDN architecture to capture network, SDN control data, system call traces, and power measurements in parallel. This design removes replay artifacts, preserves realism, and achieves a realistic benign scenario for benign data collection.

Shown in Algorithm 1, the Floodlight SDN controller implements OSPF-like routing as a

30 s control loop. Each cycle, the Floodlight SDN controller discovers the L2 topology via Link Layer Discovery Protocol (LLDP) and maintains a graph

where

V are OVSs datapaths and

E are inter-OVS links. The weights of links are assigned using an Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP) [

37] composite metric:

with defaults

, which reduces to

Bandwidth (Bw) reflects residual capacity; Delay is estimated from LLDP timing or active probes; Load Reliability (Rl) can be enabled to penalize congestion or flakiness. Metrics are normalized per iteration, and links failing health thresholds are suppressed or penalized.

For path computation, the controller builds a policy-constrained subgraph, then runs Dijkstra’s algorithm shown in Algorithm 1. A multi-source variant is used by attaching a zero-cost super-source to eligible ingress edge ports. A heap-based priority queue yields the predecessor map for all destinations. Ties are broken by fewer hops and lexicographic port. For rule realization, the controller installs symmetric OpenFlow 1.3 entries via the REST static-entry pusher. Rules are epoch-versioned, use fixed normal priorities, and set idle timeouts aligned to the loop. This produces a deterministic, policy-compliant normal-path baseline that carries both enterprise-level benign traffic and SCADA/EMS communication flows.

|

Algorithm 1 OSPF-like Path Computation using the Floodlight SDN controller |

-

Require:

LLDP-derived graph of OVS datapaths; VLAN set ; link metrics {Bandwidth, Load, Delay, Reliability}; ; health thresholds; epoch id -

Ensure:

Normal-path OpenFlow rules for all OVSs - 1:

Topology Discovery: Query switches and ports and update G

- 2:

for all links do

- 3:

EIGRP-style Cost:

- 4:

- 5:

Normalize metrics; apply a large penalty if degraded - 6:

end for - 7:

for all VLAN do

- 8:

Build policy-constrained subgraph = - 9:

Add virtual super-source x with zero-weight edges to all eligible ingress edge-ports - 10:

Dijkstra: run multi-source Dijkstra on from x using a binary-heap PQ - 11:

Break ties by (i) fewer hops, then (ii) lexicographic

- 12:

for all destinations d reachable in do

- 13:

Extract next-hop path from predecessor map - 14:

Program Forward Path: install OF 1.3 rules (match: in_port, vlan_vid [, eth_type]; action: output=<egress>) - 15:

Program Return Path: install symmetric rules to avoid asymmetry - 16:

end for

- 17:

end for - 18:

Versioning & Stability: tag rules with epoch; keep previous path if new cost unstable - 19:

Optional ECMP: if multiple equal-cost next-hops, split deterministically - 20:

Timeouts: set hard/idle timeouts to align with ∼30 s recomputation loop |

Under the normal-path policy computed by Algorithm 1, benign traffic is produced by real user activities in the admin area and by SCADA communications in the microgrid areas. On the admin side, users generate enterprise-level everyday workloads, including web browsing, emailing, and videoing, using automation routines. These user activities produce background service traffic. These routines invoke real client applications and interact with our in-house servers, ensuring authentic protocol handshakes and session behaviors rather than replayed or synthetically crafted packets.

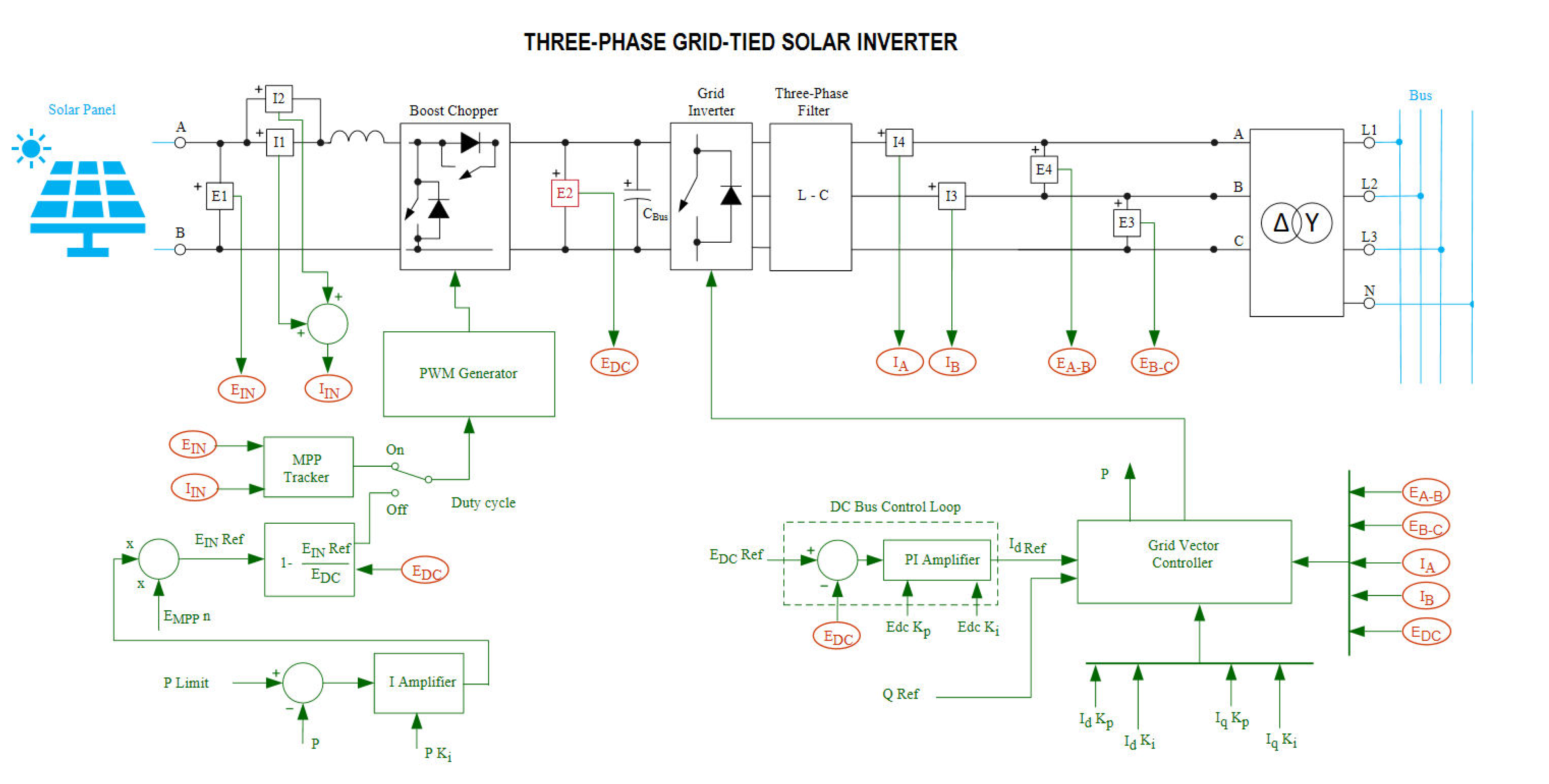

In each Micro Grid Area, the EMS runs a three-phase grid-tied solar inverter application shown in

Figure 3. The topology consists of four functional stages with their control loops: PV-side DC conversion, a DC-bus energy buffer, three-phase inversion, grid filtering, and coupling. On the left, the PV array is processed by a boost chopper that raises and stabilizes the voltage onto the DC bus. A DC-bus PI regulator compares

(DC-bus voltage) with its reference

and produces the d-axis current reference

for the downstream modulator. The grid inverter converts the DC power to three-phase AC under a PWM generator, and an LC output filter attenuates switching harmonics before coupling to the grid. On the right, a

–

Y transformer interfaces the inverter with the utility network; measurement points such as

,

and the line-to-line voltages

,

provide feedback for closed-loop control. System-level coordination is handled by the

grid vector controller, which, given the active/reactive power references (P/Q Ref), generates

and

and, together with the DC-bus loop, regulates the inverter to achieve grid-tied operation. The EMS and SCADA communications include the following measurements and set-points: DC Bus Voltage (V), Input Voltage (V), Input Current (A), Input Power (W), Active Power (W), and Reactive Power (W). These set-points and measurements are transported over normal OVS paths decided by the SDN controller. The communications of these parameters are time-stamped and recorded as the microgrid-side benign traffic in the SDN-MG25 dataset.

Using the CICFlowMeter tool [

38], more than 80 features could be generated from original network flow data and details of the most significant features are in

Section 6. The benign scenarios of the proposed dataset were collected in the testbed described in

Section 3 over 5 days. Benign scenarios of the dataset consist of more than 20,920 realistic network flows in total.

5. Attack Scenarios

While

Section 4 details the construction of normal scenarios, this section presents the attack design on the SDN–microgrid testbed in

Figure 2. Guided by the SDN architecture in

Figure 1, the attack scenarios target the SDN control plane, control channel (the OpenFlow link between control plane and data plane), and the data plane (DP). Eleven attack scenarios are implemented against these attack surfaces [

14,

22], executing them on the live platform and recording their effects across all modalities. The attacks included in the dataset are summarized below.

Eavesdropping on Control Channel: This passive attack targets the SDN control channel, which often relies on OpenFlow traffic between switches and the controller. By intercepting this traffic, an attacker can infer sensitive information such as network topology, host locations, and flow rule updates, thus gaining deep insights into the network’s structure and defense strategies. In the experiment, a Kali machine was positioned on a mirrored or bypass port to passively capture the control traffic. The following command was used to record OpenFlow communication between the controller and switches: tcpdump -i eth0 port 6633 or port 6653 -w controller_traffic.pcap. From the captured traffic, the attacker could reconstruct the network topology, determine the location of hosts, and observe changes in forwarding policies over time.

Flow Rule Flooding on Data Plane: This attack exploits the limited rule capacity of OpenFlow switches by continuously injecting fine-grained flow rules, forcing the switch flow table to saturate. As the number of rules increases, the latency of installing new flows grows significantly, eventually leading to installation failures and degraded forwarding performance. In the experiment, the Kali machine impersonated a legitimate REST NBI client to the Floodlight controller and repeatedly pushed thousands of new rules using the staticentrypusher API.

Flow Rule Injection on Control Plane: This control-plane attack abuses the northbound interface (NBI) of the SDN controller, such as the REST API for static flow rule management. By inserting high-priority drop-all rules, the attacker can instantly disrupt communication across multiple switches. In the experiment, the Kali attacker acted as an unauthorized REST client and issued crafted HTTP POST requests to the Floodlight controller’s static entry pusher module. After batch insertion of drop-all rules across multiple switches, legitimate traffic was silently dropped. To remove the injected rules and restore connectivity, the attacker could issue a corresponding DELETE request.

Flow Table Flush on Control Plane: This control-plane attack exploits the vulnerability of SDN controllers that allow remote applications or clients to clear flow tables. By repeatedly deleting all installed rules, the attacker forces the network into a cold start state, where every incoming flow must trigger a packet_in event and subsequent rule installation. This not only inflates the latency of both first and subsequent packets but can also induce bursts of packet_in messages, overwhelming the controller. In the experiment, the Kali attacker executed scripts that continuously invoked the controller’s REST API to clear all flow entries from the switch:

curl -X DELETE http://192.168.4.149:8080/wm/staticentrypusher/ clear/all/json

Flow Table Overflow on Data Plane: This data-plane-based attack exploits the limited flow table capacity of OpenFlow switches by overwhelming them with a massive number of unique flow entries. The attacker crafts high-dimensional traffic with unseen 5-tuples (source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, and protocol), triggering frequent table-miss events. Each miss prompts the switch to query the controller and install a new flow entry, eventually exhausting the table and degrading performance. To realize this attack in practice, the hping3 tool was used on the Kali machine to generate diverse TCP SYN packets with randomized source IPs and incremental destination ports, as shown below: hping3 -c 100000 -d 120 -S -w 64 -p ++50 -s 2000 –flood –rand-source 192.168.4.149. The flood of new flows results in an increased number of flow installation events handled by the controller and gradual exhaustion of switch table entries.

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) on Control Channel: This attack compromises the integrity of the SDN control channel by placing the attacker between the controller and switches. Once in the middle, the attacker can intercept, analyze, and tamper with OpenFlow messages, altering flow rules before they reach the switch. This enables malicious manipulation of network behavior, such as redirecting, dropping, or degrading legitimate traffic. In the experiment, the Kali machine used Bettercap to perform ARP spoofing and intercept control traffic, with the following command: sudo bettercap -iface eth0 -X. After successfully establishing a man-in-the-middle position, the tcp.proxy module in bettercap was configured to manipulate OpenFlow messages. Specifically, the attacker altered flow modification instructions by replacing forwarding actions with drop actions. This resulted in switches installing tampered flow entries that silently discarded packets instead of forwarding them as intended by the controller.

Mimicry actions on Hosts: Mimicry attacks were performed by executing redundant but benign system calls, such as open(), read(), write(), close(), and access(), to camouflage malicious activities. The attacker first exploited the Nmap SUID vulnerability to escalate privileges and establish a Meterpreter session. During and around the execution of real intrusion steps, dummy actions such as reading non-existent files, creating empty files, querying system information, and listing temporary directories were repeatedly executed. These actions flooded the system call traces with patterns common in normal operations, thereby mixing malicious traces with legitimate ones. As a result, detection tools were misled by the high volume of innocuous system calls, delaying or preventing accurate identification of the intrusion. This strategy enabled persistent presence and increased the success probability of subsequent malicious activities such as data theft or maintaining backdoor access.

Packet-In Flooding on Control Plane: This control-plane-based DoS attack targets the SDN controller by exploiting the OpenFlow protocol’s reactive forwarding behavior. When an OpenFlow switch receives a packet that does not match any existing flow entry, it sends a packet_in message to the controller. By generating a high rate of such unmatched packets, the attacker forces the switch to flood the controller with requests, consuming its CPU and bandwidth resources. To launch this attack in practice, the Kali machine utilized the hping3 tool to generate randomized TCP SYN packets with incremental destination ports and random source IPs: hping3 -S -p ++10000 –flood –rand-source 192.168.4.149. Unlike a flow table overflow, this attack does not rely on installing flows but instead aims to overwhelm the controller’s processing pipeline through a deluge of control messages.

Scanning on Data Plane: This reconnaissance attack leverages the data plane to probe network topology and host availability while exploiting subtle timing variations as a side-channel to infer controller behavior. By carefully observing the round-trip time (RTT) of probing packets. In the experiment, port and vulnerability scans were conducted using Nmap and Nessus. For example, the following Nmap command was used to scan all ports and detect service versions on the target:nmap -p- -sV victim_ip

Topology Poisoning on control channel: This control-channel attack exploits the trust relationship between the controller and the topology discovery process. In OpenFlow networks, the SDN controllers rely on LLDP packets reported by switches to construct the global network view. By injecting fake LLDP frames, an attacker can mislead the controller into believing that non-existent links or devices are present, thereby corrupting the network topology map and influencing routing and policy decisions. In the experiment, the Kali attacker used Scapy to craft and inject forged LLDP packets into the same Layer-2 domain as the target switch. A simplified Python script was employed to continuously generate fake discovery frames. To emulate multiple fake switches, the script randomized the source MAC address and port identifiers for each forged packet.

To analyze and evaluate these attack scenarios, the dataset ingests heterogeneous data, including network flows, system call traces, SDN-OVS states, and power measurements. As outlined in

Section 4, packet captures from real enterprise activity and SCADA/EMS communications are converted to flow records with CICFlowMeter. The generated feature tables are later described in

Section 6. Host-side behavior is recorded using Auditd and ProcMon on the SDN controller and relevant hosts. The system call traces include fields such as syscall ID, return status, parent PID, PID, argument vectors, and timestamps, which are normalized into structured tabular data with Pandas. The dataset also includes real-time monitoring and management states of the controlled OVSs by an SDN controller (SDN-OVS states). First, the dataset includes flow table rules issued by the switch, which reflect the forwarding strategies and processing logic of data packets in the network. Second, port-related information records the operational status and traffic statistics of each switch port, revealing the communication characteristics and load conditions of different links in the network. Additionally, flow table statistics provide detailed information on table entry usage, including table ID, number of active entries, lookup counts, and match counts, thereby characterizing the dynamic distribution of network traffic. Finally, topology structure information describes the connection relationships between switches, illustrating the physical and logical interconnections of the entire network. For the electrical layer, LVDAC-EMS interfaces include DC-bus voltage, input voltage/current, inverter frequency, phase currents/line voltages, and active/reactive power. During attack execution, the same set of power measurements, system call traces, SDN-OVS states, and network flows are collected, enabling cross-modal analysis. Note that certain cyberattacks may not produce an immediate or direct change in power metrics, even though they are evident in network or host traces. Ground-truth labels for benign/attack intervals are automatically derived from the orchestrated scenario timeline and applied uniformly across all synchronized modalities.

This dataset was collected over 10 working days. The benign part of this dataset contains more than 209,200 network flows, 763,040 system call traces, 17,550 SDN-OVS states, and 16,340 microgrid power measurements. The malicious part of this dataset includes more than 181,400 network flows, 711,830 system call traces, 13,280 SDN-OVS states, and 18,490 microgrid power measurements.

6. Preliminary Analysis

This section details the preliminary analysis of the SDN-MG25 dataset, including dataset preprocessing, effects of attacks on the stability of microgrid systems, and encryption of the dataset.

6.1. Dataset Preprocessing

Discussed in

Section 4 and

Section 5, the CICFlowMeter tool [

38] is deployed to process network flow data. As more than 80 features are generated in processed CSV data, it is necessary to identify the most important features. Before identifying the key features of network traffic, preprocessing was conducted. Non-essential columns, such as stream IDs, IP addresses, ports, and timestamps, were removed to reduce dimensionality and minimize bias. Outliers were handled by imputing missing values with mean interpolation, while infinite values were converted to

NaN to preserve data consistency. The remaining features were standardized using

StandardScaler, which normalized them to a zero mean and unit variance, thereby eliminating scale differences. Finally, categorical labels were encoded into integers to facilitate classification.

A Random-Forest–based wrapper feature selection method [

22] is deployed to identify the most important features in processed network flows. This method firstly trains the Random Forest model under the conditions of mean padding and standardization. Score each feature based on the reduction in impurity it contributes during tree splitting, and normalize the scores so that their sum equals 1. Then perform permutation importance analysis on the reserved test set by randomly shuffling each feature and observing the extent of model performance degradation to validate the true contribution of these features to generalization. Using this method, select a stable set of Top-K features and ensure reproducibility of results through stratified sampling and a fixed random seed. The resulting set of reliable key features facilitates dimensionality reduction and improves modeling efficiency. These selected important features can directly support future research work in evaluating and comparing various machine learning or deep learning-based IDS methods on this dataset.

Time-based features (e.g., Fl IAT Min/Max/Mean/Std, Fwd IAT Tot, Bwd IAT Tot): capture the statistical distribution of inter-arrival times between packets, which helps in identifying temporal patterns and frequency variations within network flows.

Flow Duration: represents the overall length of a traffic session, providing insights into the scale and complexity of network interactions. Extended durations typically correspond to more intensive or prolonged data exchanges.

Packet Transmission Rate (e.g., Fwd Pkts/s, Bwd Pkts/s): quantifies the rate of packet flow in forward and reverse directions, serving as a key metric for evaluating traffic density and network utilization.

Packet Count Metrics (e.g., Tot Fwd Pkts, Sub Fwd Pkts): denote the total and segmented counts of transmitted packets, highlighting the volume of data transfer and the intensity of session activity.

Header Size Feature (Fwd Hdr Len): measures the aggregate size of forward packet headers, reflecting the proportion of control or protocol overhead; larger values often suggest complex signaling or management traffic.

Traffic Intensity (Fl Pkts/s): indicates the overall rate of packet transmission across the flow, with elevated values pointing to high-load conditions or peak usage scenarios.

For the system call trace data, logs from Auditd and ProcMon are parsed. A single record is retained per Syscall event, capturing the system call number, execution status, command name, and executable path. The Syscall field is cast to an integer, the success flag is normalized, malformed rows are removed, and the remaining fields are consolidated into a structured DataFrame. A binary label is attached based on the trace source. To make textual attributes usable, comm and exe are converted into numeric identifiers via a corpus-fitted LabelEncoder. The resulting tabular form standardizes heterogeneous logs and can be extended with sequences. These preprocessing steps provide a consistent, machine-readable input that subsequent research can directly use to benchmark a wide range of IDS methods on this dataset.

6.2. Preliminary Analysis of Attack Effects

This section discusses how attacks influence the control and data plane of the SDN network and the collected power measurement data. Based on the collected state data of the SDN control and data plane, including flow rules, switch ports, switch tables, and topology links, the effects of attacks on the SDN network are preliminarily analyzed. During the attack time window, the flow rule log states show abnormal churn bursts of newly injected high-priority actions, such as drop or redirect. Followed by rapid vacillation, the flow rules eventually suffer rule starvation. Switch port statistics show a surge in receiving and forwarding counters, together with rising drops and errors. Flow table metrics escalate in active count and lookup count, then collapse, indicating table pressure and subsequent resets. Topology states reveal forged or flapping LLDP links, producing inconsistent path computation.

A representative symptom during the attack window is that the SDN controller’s REST endpoint stops returning structured statistics and instead responds with error logs. Shortly afterward, several polling cycles degrade to empty returns, indicating a loss of switch–controller communications. The collected data precisely describes the behaviors expected when the SDN network is being stressed by attacks. These SDN–OVS state data are time-aligned with system call traces and network flows, and they provide a control and data plane ground truth.

Cyberattacks on SDN-managed microgrid systems disrupt communications between SCADA and EMS. These attacks also perturb the tightly coupled control loops of the power converter. In our dataset, the physical consequences are captured by time-stamped SCADA measurements from the three-phase grid-tied inverter DC-bus voltage , input voltage, input current, input power, active power P, and reactive power Q. These signals provide a direct, observable trace of how cyber events propagate into microgrid behaviors.

The instrumentation in Fig.

Figure 3 explains these couplings. A DC-bus PI regulator compares

with its reference and generates the d-axis current command

, while the grid-vector controller produces

and

to track

set-points through the PWM-driven VSI and the

output filter before grid coupling via the

transformer. When attackers distort the timing and paths of the SDN network, the control loops misregulate. This misregulation manifests as DC-bus sag with correlated surges in input current, oscillations, and drift in

Q that degrade power factor.

6.3. Encryption of SDN-MG25 Dataset

Given the sensitivity of microgrid datasets, we encrypt all processed CSV files—including network flows, system call traces, and power measurements—using the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). To ensure both confidentiality and integrity, we adopt AES that operates per file with a fresh random nonce and a key. The encrypted payload is stored together with the required metadata to enable reproducible decryption under proper authorization. While AES encryption introduces some real-time concerns, it is not a limiting factor in microgrid settings because most data is consumed for planning and analysis rather than real-time control. Workloads such as load forecasting, demand response evaluation, and energy market optimization are typically batch or near-batch and tolerate the time of processing. Therefore, AES encryption remains a practical and effective security enhancement. An encrypted copy of every processed file is included in the SDN-MG25 dataset to facilitate future research on privacy-preserving analytics and secure IDS benchmarking using the same data.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents SDN-MG25, a comprehensive and heterogeneous dataset built for intrusion detection research in SDN-enabled microgrid systems. Constructed on a live and operational SDN–microgrid testbed, the dataset captures synchronized multimodal data across network flows, system call traces, SDN control and forwarding states, and microgrid power measurements. The proposed dataset reflects the complexity and realism of real-world enterprise-level user activities and microgrid operations. The implemented attack scenarios span data plane, control plane, and control channel attack surfaces, enabling cross-modal analysis. Preliminary analysis demonstrates the value of this dataset in supporting feature selection and benchmarking for future intrusion detection systems. Future work will focus on expanding attack diversity to stealthy FDI attacks.

Acknowledgement

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process. During the preparation of this work, the authors used Grammarly and Claude in order to improve the readability and language of the work. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Singh, M.P.; Bhandari, A. New-flow based DDoS attacks in SDN: Taxonomy, rationales, and research challenges. Computer Communications 2020, 154, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, J.C.C.; Imbachi, J.C.; Vega, J.F.B. Security in SDN: A comprehensive survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2020, 159, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, N.; Anderson, T.; Balakrishnan, H.; Parulkar, G.; Peterson, L.; Rexford, J.; Shenker, S.; Turner, J. OpenFlow: enabling innovation in campus networks. ACM SIGCOMM computer communication review 2008, 38, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitharthan, R.; Vimal, S.; Verma, A.; Karthikeyan, M.; Dhanabalan, S.S.; Prabaharan, N.; Rajesh, M.; Eswaran, T. Smart microgrid with the internet of things for adequate energy management and analysis. Computers and Electrical Engineering 2023, 106, 108556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Guo, F.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Du, X.; Zhang, J. Enhancing Reliability and Performance of Load Frequency Control in Aging Multi-Area Power Systems under Cyber-Attacks. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Mo, H.; Wu, J.; Pan, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, F. A hybrid stacking model for enhanced short-term load forecasting. Electronics 2024, 13, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Wu, Y.; Xie, P.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Abusorrah, A. New challenges in the design of microgrid systems: Communication networks, cyberattacks, and resilience. IEEE Electrification Magazine 2020, 8, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nand, K.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J. A Comprehensive Survey on the Usage of Machine Learning to Detect False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2025, 6, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pota, H.R. Droop control for islanded microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Power &, Energy Society General Meeting. IEEE; 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Turnbull, B.; Kermanshahi, S.K.; Pota, H.; Damiani, E.; Yeun, C.Y.; Hu, J. A survey on resilient microgrid system from cybersecurity perspective. Applied Soft Computing 2025, p. 113088.

- Zhong, J.; Chen, C.; Bie, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. Strategic SDN-Based Microgrid Formation for Managing Communication Failures in Distribution System Restoration. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2025, 40, 2506–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherian-Fard, E.; Niknam, T.; Sahebi, R.; Javidsharifi, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Aghaei, J. A Software Defined Networking Architecture for DDoS-Attack in the Storage of Multimicrogrids. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 83802–83812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzio-García, J.; Vergara, J.; Ríos-Guiral, S.; Garzón, C.; Gutiérrez, S.; Botero, J.F.; Quiroz-Arroyo, J.L.; Pérez-Díaz, J.A. Exploring Traffic Patterns Through Network Programmability: Introducing SDNFLow, a Comprehensive OpenFlow-Based Statistics Dataset for Attack Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42163–42180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Park, T.; Shin, S.; Yegneswaran, V.; Porras, P.; Gu, G. Flow Wars: Systemizing the Attack Surface and Defenses in Software-Defined Networks. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2017, 25, 3514–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ning, H.; Shi, F.; Farha, F.; Xu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, F.; Choo, K.K.R. Artificial intelligence in cyber security: research advances, challenges, and opportunities. Artificial Intelligence Review 2022, pp. 1–25.

- Yang, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; He, H. A data-driven detection strategy of false data in cooperative DC microgrids. In Proceedings of the IECON 2021–47th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society. IEEE; 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Niknam, T.; Ghiasi, M.; Bayati, N.; Savaghebi, M. Cyber-attack detection in dc microgrids based on deep machine learning and wavelet singular values approach. Electronics 2021, 10, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Lohiya, R. A review of the advancement in intrusion detection datasets. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 167, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Mohay, G.; Tickle, A.; Bhatia, S. Use of ip addresses for high rate flooding attack detection. In Proceedings of the Security and Privacy–Silver Linings in the Cloud: 25th IFIP TC-11 International Information Security Conference, SEC 2010, Held as Part of WCC 2010, Brisbane, Australia, September 20-23, 2010. Proceedings 25. Springer, 2010, pp. 124–135.

- Mirkovic, J.; Fahmy, S.; Reiher, P.; Thomas, R.K. How to test dos defenses. In Proceedings of the 2009 cybersecurity applications &, technology conference for homeland security. IEEE; 2009; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, M.; Terzis, M.A. My botnet is bigger than yours (maybe, better than yours): why size estimates remain challenging. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Understanding Botnets, Cambridge, USA, 2007, Vol. 18, p. 5.

- Zhang, Z.; Turnbull, B.; Kermanshahi, S.K.; Pota, H.; Hu, J. UNSW-MG24: A Heterogeneous Dataset for Cybersecurity Analysis in Realistic Microgrid Systems. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2025, 6, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaan Sarica, A.; Angin, P. A Novel SDN Dataset for Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM); 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.S.; Le-Khac, N.A.; Jurcut, A.D. InSDN: A Novel SDN Intrusion Dataset. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165263–165284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yungaicela-Naula, N.M.; Vargas-Rosales, C.; Perez-Diaz, J.A.; Jacob, E.; Martinez-Cagnazzo, C. Physical Assessment of an SDN-Based Security Framework for DDoS Attack Mitigation: Introducing the SDN-SlowRate-DDoS Dataset. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 46820–46831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahashwan, A.A.; Anbar, M.; Manickam, S.; Issa, G.; Aladaileh, M.A.; Alabsi, B.A.; Rihan, S.D.A. HLD-DDoSDN: High and low-rates dataset-based DDoS attacks against SDN. Plos one 2024, 19, e0297548. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, K.; Shalinie, S.M. SHAP-based Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks Using Quantum Neural Networks on IonQ Hardware. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2025, p. 105133.tection in IoT Networks Using Quantum Neural Networks on IonQ Hardware.

- Booij, T.M.; Chiscop, I.; Meeuwissen, E.; Moustafa, N.; Den Hartog, F.T. ToN_IoT: The role of heterogeneity and the need for standardization of features and attack types in IoT network intrusion data sets. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 9, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Keshky, M.; Debiez, E.; Janicke, H. Federated TON_IoT Windows datasets for evaluating AI-based security applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 19th international conference on trust, security and privacy in computing and communications (TrustCom). IEEE; 2020; pp. 848–855. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos Pinto Neto, E.; Taslimasa, H.; Dadkhah, S.; Iqbal, S.; Xiong, P.; Rahman, T.; Ghorbani, A. CICIoV2024: Advancing realistic IDS approaches against DoS and spoofing attack in IoV CAN bus. Hamideh and Dadkhah, Sajjad and Iqbal, Shahrear and Xiong, Pulei and Rahman, Taufiq and Ghorbani, Ali, Ciciov2024: Advancing Realistic Ids Approaches Against Dos and Spoofing Attack in Iov Can Bus 2024.

- Rabbani, M.; Gui, J.; Nejati, F.; Zhou, Z.; Kaniyamattam, A.; Mirani, M.; Piya, G.; Opushnyev, I.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. Device Identification and Anomaly Detection in IoT Environments. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Creech, G.; Hu, J. Generation of a new IDS test dataset: Time to retire the KDD collection. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE wireless communications and networking conference (WCNC). IEEE; 2013; pp. 4487–4492. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M.; Hu, J.; Slay, J. Evaluating host-based anomaly detection systems: Application of the one-class SVM algorithm to ADFA-LD. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD). IEEE; 2014; pp. 978–982. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.N.; Pota, H.R.; Tran, Q.N.; Yin, X.; Hu, J. Designing false data injection attacks penetrating AC-based bad data detection system and FDI dataset generation. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2022, 34, e5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostinato. Ostinato - Packet/Traffic Generator and Analyzer. https://ostinato.org/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-01-07.

- Shahid, K.; Ahmad, S.N.; Rizvi, S.T.H. Optimizing Network Performance: A Comparative Analysis of EIGRP, OSPF, and BGP in IPv6-Based Load-Sharing and Link-Failover Systems. Future Internet 2024, 16, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, A.H.; Gil, G.D.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of tor traffic using time based features. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy. SciTePress, Vol. 2; 2017; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).