Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

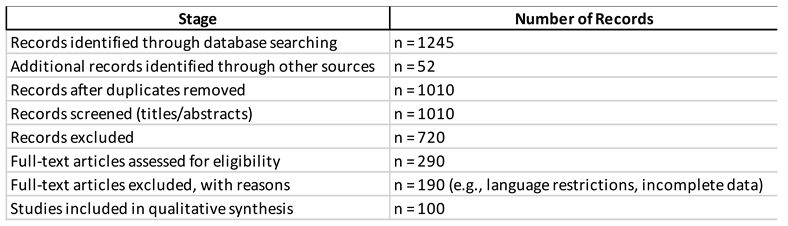

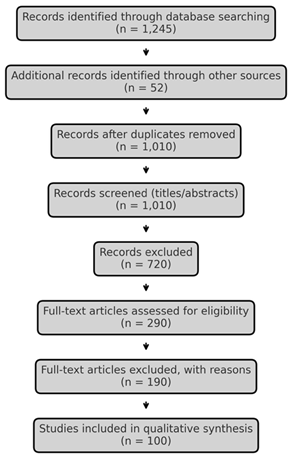

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

Eligibility Criteria

- Pathophysiology of vascular pain (ischemia, microvascular dysfunction, neuroinflammation, nociplastic mechanisms).

- Clinical characteristics of pain in VLUs, including prevalence, severity, and patient-reported outcomes.

- Diagnostic approaches integrating vascular and pain assessment.

- Management strategies, including conservative, pharmacological, interventional, and bioengineering-based approaches.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Quality Considerations and Scientific Reasoning

Referencing and Transparency

Limitations of Methodology

Results

Epidemiology and Patient-Reported Burden

Pathophysiology of VLU Pain

Clinical Phenotype and Assessment

Diagnostic Framework (Vascular and Wound)

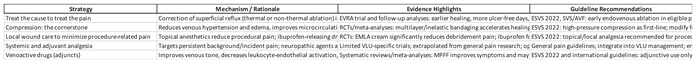

Management Strategies for Pain in VLUs

Quality of Life, Adherence, and Person-Centered Care

Special Populations and Comorbidity

Evidence Gaps and Future Directions

Limitations of This Review

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical approval

References

- Stanek A, Mosti G, Nematillaevich TS, Valesky EM, Planinšek Ručigaj T, Boucelma M, Marakomichelakis G, Liew A, Fazeli B, Catalano M, Patel M. No More Venous Ulcers-What More Can We Do? J Clin Med. 2023 Sep 23;12(19):6153. [CrossRef]

- Attaran RR, Edwards ML, Arena FJ, Bunte MC, Carr JG, Castro-Dominguez Y, Espinoza A, Feldman DN, Firestone S, Fukaya E, Harth K. 2025 SCAI Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Venous Disease: This statement was endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine (SVM). J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025 Jun 30:103729. [CrossRef]

- Sussman C, Bates-Jensen B. Management of wound pain. Wound Care: A Collaborative Practice Manual for Health Professionals. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007.

- O’Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA, Marston WA, Ennis WJ, Dalsing M, Kistner RL, Lurie F, Henke PK, Gloviczki ML, Eklöf BG, Stoughton J, Raju S, Shortell CK, Raffetto JD, Partsch H, Pounds LC, Cummings ME, Gillespie DL, McLafferty RB, Murad MH, Wakefield TW, Gloviczki P; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Venous Forum. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery ® and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014 Aug;60(2 Suppl):3S-59S. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann AG, Deinsberger J, Oszwald A, Weber B. The Histopathology of Leg Ulcers. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2024 Jan 29;11(1):62-78. [CrossRef]

- Probst S, Schobinger E, Saini C, Larkin P, Bobbink P. Unveiling the hidden pain and daily struggles of individuals with a venous leg ulcer: a thematic analysis. J Tissue Viability. 2025 Aug;34(3):100906. [CrossRef]

- Weir D, Davies P. The impact of venous leg ulcers on a patient’s quality of life: considerations for dressing selection. Wounds Int. 2023 Feb 7;14(1):36-41. Available at: https://www.molnlycke.co.nz/SysSiteAssets/master-and-local-markets/documents/master/wound-care-documents/vlu/wint14-1_davies-web.pdf.

- Todd M. Assessment and management of older people with venous leg ulcers. Nurs Older People. 2018 Jul 26;30(5):39-48. [CrossRef]

- Jia H, Tan Y, Li H, Bu X, Li L, Lei X. A nomogram model for predicting risk factors and the outcome of skin ulcer. Ann Med. 2025 Dec;57(1):2525404. [CrossRef]

- Ketteler E, Cavanagh SL, Gifford E, Grunebach H, Joshi GP, Katwala P, Kwon J, McCoy S, McGinigle KL, Schwenk ES, Shutze WP, Vaglienti RM, Rossi P. The Society for Vascular Surgery expert consensus statement on pain management for vascular surgery diseases and interventions. J Vasc Surg. 2025 Jul;82(1):1-31.e2. [CrossRef]

- Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019 Mar 26;4:5. [CrossRef]

- Lim CS, Baruah M, Bahia SS. Diagnosis and management of venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 2018 Aug 14;362:k3115. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Team V, Qiu Y, Weller CD. Measurement properties of quality of life instruments for adults with active venous leg ulcers: a systematic review protocol. Wound Practice & Research: J Austr Wound Man Ass. 2021 Jun 1;29(2):104-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Team V, Qiu Y, Weller CD. Investigating quality of life instrument measurement properties for adults with active venous leg ulcers: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2022 Jul;30(4):468-486. [CrossRef]

- Olsson M, Wadin L, Åhlén J, Friman A. A qualitative study of patients’ experiences of living with hard-to-heal leg ulcers. Br J Community Nurs. 2023 Jun 1;28(Sup6):S8-S13. [CrossRef]

- Probst S, Saini C, Gschwind G, Stefanelli A, Bobbink P, Pugliese MT, Cekic S, Pastor D, Gethin G. Prevalence and incidence of venous leg ulcers-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2023 Nov;20(9):3906-3921. [CrossRef]

- Price P, Harding K. Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule: the development of a condition-specific questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life in patients with chronic wounds of the lower limb. Int Wound J. 2004 Apr;1(1):10-7. [CrossRef]

- Bland JM, Dumville JC, Ashby RL, Gabe R, Stubbs N, Adderley U, Kang’ombe AR, Cullum NA. Validation of the VEINES-QOL quality of life instrument in venous leg ulcers: repeatability and validity study embedded in a randomised clinical trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015 Aug 11;15(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Granado-Casas M, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Martínez-Alonso M, Dòria M, Alcubierre N, Valls J, Julve J, Verdú-Soriano J, Mauricio D. Psychometric Validation of the Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule Questionnaire in a Spanish Population with Diabetic Foot Ulcer. J Clin Med. 2021 Sep 6;10(17):4023. [CrossRef]

- Saharay M, Shields DA, Porter JB, Scurr JH, Coleridge Smith PD. Leukocyte activity in the microcirculation of the leg in patients with chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 1997 Aug;26(2):265-73. [CrossRef]

- Raffetto JD, Ligi D, Maniscalco R, Khalil RA, Mannello F. Why Venous Leg Ulcers Have Difficulty Healing: Overview on Pathophysiology, Clinical Consequences, and Treatment. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 24;10(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Attaran RR, Carr JG. Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Extremities: A State-of-the Art Review. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022 Nov 26;2(1):100538. [CrossRef]

- Coelho GA, Secretan PH, Tortolano L, Charvet L, Yagoubi N. Evolution of the Chronic Venous Leg Ulcer Microenvironment and Its Impact on Medical Devices and Wound Care Therapies. J Clin Med. 2023 Aug 28;12(17):5605. [CrossRef]

- Krizanova O, Penesova A, Hokynkova A, Pokorna A, Samadian A, Babula P. Chronic venous insufficiency and venous leg ulcers: Aetiology, on the pathophysiology-based treatment. Int Wound J. 2023 Oct 19;21(2):e14405. [CrossRef]

- Hart O, Adeane S, Vasudevan T, van der Werf B, Khashram M. The utility of hyperspectral imaging in patients with chronic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2022 Nov;10(6):1325-1333.e3. [CrossRef]

- Leren L, Johansen E, Eide H, Falk RS, Juvet LK, Ljoså TM. Pain in persons with chronic venous leg ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2020 Apr;17(2):466-484. [CrossRef]

- Mayrovitz HN, Wong S, Mancuso C. Venous, Arterial, and Neuropathic Leg Ulcers with Emphasis on the Geriatric Population. Cureus. 2023 Apr 25;15(4):e38123. [CrossRef]

- Pan Q, Zhai X, Wang H, Du J, Shi Y, Yu X, Yan S, Wu X, Li HH, Sun T, Guo L, Zhao J, Fan B. Real-World Pharmacological Treatment Pattern of Neuropathic Pain in China: A Retrospective, Database, Multicenter Study (ReTARdant) Protocol. Pain Ther. 2025 Aug 11. [CrossRef]

- De Maeseneer MG, Kakkos SK, Aherne T, Baekgaard N, Black S, Blomgren L, Giannoukas A, Gohel M, de Graaf R, Hamel-Desnos C, Jawien A, Jaworucka-Kaczorowska A, Lattimer CR, Mosti G, Noppeney T, van Rijn MJ, Stansby G, Esvs Guidelines Committee, Kolh P, Bastos Goncalves F, Chakfé N, Coscas R, de Borst GJ, Dias NV, Hinchliffe RJ, Koncar IB, Lindholt JS, Trimarchi S, Tulamo R, Twine CP, Vermassen F, Wanhainen A, Document Reviewers, Björck M, Labropoulos N, Lurie F, Mansilha A, Nyamekye IK, Ramirez Ortega M, Ulloa JH, Urbanek T, van Rij AM, Vuylsteke ME. Editor’s Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Feb;63(2):184-267. Epub 2022 Jan 11. Erratum in: Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Aug-Sep;64(2-3):284-285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2022.05.044. [CrossRef]

- Valesky EM, Hach-Wunderle V, Protz K, Zeiner KN, Erfurt-Berge C, Goedecke F, Jäger B, Kahle B, Kluess H, Knestele M, Kuntz A, Lüdemann C, Meissner M, Mühlberg K, Mühlberger D, Pannier F, Schmedt CG, Schmitz-Rixen T, Strölin A, Wilm S, Rabe E, Stücker M, Dissemond J. Diagnosis and treatment of venous leg ulcers: S2k Guideline of the German Society of Phlebology and Lymphology (DGPL) e.V. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2024 Jul;22(7):1039-1051. [CrossRef]

- Weller CD, Team V, Ivory JD, Crawford K, Gethin G. ABPI reporting and compression recommendations in global clinical practice guidelines on venous leg ulcer management: A scoping review. Int Wound J. 2019 Apr;16(2):406-419. Epub 2018 Nov 28. Erratum in: Int Wound J. 2019 Aug;16(4):1074. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13165. [CrossRef]

- Gohel MS, Mora MSc J, Szigeti M, Epstein DM, Heatley F, Bradbury A, Bulbulia R, Cullum N, Nyamekye I, Poskitt KR, Renton S, Warwick J, Davies AH; Early Venous Reflux Ablation Trial Group. Long-term Clinical and Cost-effectiveness of Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2020 Dec 1;155(12):1113-1121. [CrossRef]

- Shawa HJ, Dahle SE, Isseroff RR. Consistent application of compression: An under-considered variable in the prevention of venous leg ulcers. Wound Rep Reg. 2023 May;31(3):393-400. [CrossRef]

- Weller C, Richards C, Turnour L, Green S, Team V. Vascular assessment in venous leg ulcer diagnostics and management in Australian primary care: Clinician experiences. J Tissue Viability. 2020 Aug;29(3):184-189. [CrossRef]

- Winders S, Lyon DE, Kelly DL, Weaver MT, Yi F, Rezende de Carvalho M, Stechmiller JK. Sleep, Fatigue, and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Older Adults with Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers Receiving Intensive Outpatient Wound Care. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2024 Oct;13(10):508-517. [CrossRef]

- Nair HK, Mosti G, Atkin L, Aburn R, Ali Hussin N, Govindarajanthran N, Narayanan S, Ritchie G, Samuriwo R, Sandy-Hodgetts K, Smart H, Sussman G, Ehmann S, Lantis J, Moffatt C, Naude L, Probst S, White W. Leg ulceration in venous and arteriovenous insufficiency: assessment and management with compression therapy as part of a holistic wound-healing strategy. J Wound Care. 2024 Oct 1;33(Sup10b):S1-S31. [CrossRef]

- Epstein DM, Gohel MS, Heatley F, Liu X, Bradbury A, Bulbulia R, Cullum N, Nyamekye I, Poskitt KR, Renton S, Warwick J, Davies AH; EVRA trial investigators. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a randomized clinical trial of early versus deferred endovenous ablation of superficial venous reflux in patients with venous ulceration. Br J Surg. 2019 Apr;106(5):555-562. [CrossRef]

- Gohel MS, Heatley F, Liu X, Bradbury A, Bulbulia R, Cullum N, Epstein DM, Nyamekye I, Poskitt KR, Renton S, Warwick J, Davies AH; EVRA Trial Investigators. A Randomized Trial of Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31;378(22):2105-2114. [CrossRef]

- Zheng H, Magee GA, Tan TW, Armstrong DG, Padula WV. Cost-effectiveness of Compression Therapy With Early Endovenous Ablation in Venous Ulceration for a Medicare Population. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Dec 1;5(12):e2248152. [CrossRef]

- Cai PL, Hitchman LH, Mohamed AH, Smith GE, Chetter I, Carradice D. Endovenous ablation for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jul 27;7(7):CD009494. [CrossRef]

- Franks PJ, Morgan PA. Health-related quality of life with chronic leg ulceration. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2003 Oct;3(5):611-22. [CrossRef]

- Holloway S, Ahmajärvi K, Frescos N, Jenkins S, Oropallo A, Slezáková S, Pokorná A, Coaccioli S, Colwill A, Woo K. Holistic management of wound-related pain: an overview of the evidence and recommendations for clinical practice. J Wound Man. 2024 Apr 1;25(1). [CrossRef]

- Dissemond J, Schicker C, Breitfeld T, Keuthage W, Häuser E, Möller U, Thomassin L, Stücker M. An innovative multicomponent compression system in a single bandage for venous leg ulcer and/or oedema treatment: a real-life study in 343 patients. J Wound Care. 2025 Jan 2;34(1):31-46. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz MJS, Moll NV, Gálvez MM, Jiménez MG, Muñoz LA. Compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2025 Jul 1;23(3):256-264. [CrossRef]

- Nair HKR, Bin Othman AF, Hariz Bin Ramli AR, Bin Md Idris MA, Azmi NM, Jaafar MA. Utilizing the adjustable Velcro system Compreflex® for patients with chronic venous leg ulcers: An observational multicenter clinical follow-up study. Phlebology. 2025 Jul 20:2683555251357361. [CrossRef]

- Buset CS, Fleischer J, Kluge R, Graf NT, Mosti G, Partsch H, Seeli C, Anzengruber F, Kockaert M, Hübner M, Hafner J. Compression Stocking With 100% Donning and Doffing Success: An Open Label Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021 Jan;61(1):137-144. [CrossRef]

- Weller CD, Richards C, Turnour L, Team V. Patient Explanation of Adherence and Non-Adherence to Venous Leg Ulcer Treatment: A Qualitative Study. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Jun 3;12:663570. [CrossRef]

- Bar L, Brandis S, Marks D. Improving Adherence to Wearing Compression Stockings for Chronic Venous Insufficiency and Venous Leg Ulcers: A Scoping Review. Pat Prefer Adher. 2021 Sep 17;15:2085-2102. [CrossRef]

- Perry C, Atkinson RA, Griffiths J, Wilson PM, Lavallée JF, Cullum N, Dumville JC. Barriers and facilitators to use of compression therapy by people with venous leg ulcers: A qualitative exploration. J Adv Nurs. 2023 Jul;79(7):2568-2584. [CrossRef]

- Turner BRH, Jasionowska S, Machin M, Javed A, Gwozdz AM, Shalhoub J, Onida S, Davies AH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise therapy for venous leg ulcer healing and recurrence. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2023 Jan;11(1):219-226. [CrossRef]

- Holm J, Andrén B, Grafford K. Pain control in the surgical debridement of leg ulcers by the use of a topical lidocaine--prilocaine cream, EMLA. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70(2):132-6. PMID: 1969197.

- Lok C, Paul C, Amblard P, Bessis D, Debure C, Faivre B, Guillot B, Ortonne JP, Huledal G, Kalis B. EMLA cream as a topical anesthetic for the repeated mechanical debridement of venous leg ulcers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Feb;40(2 Pt 1):208-13. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal D, Murphy F, Gottschalk R, Baxter M, Lycka B, Nevin K. Using a topical anaesthetic cream to reduce pain during sharp debridement of chronic leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 2001 Jan;10(1):503-5. [CrossRef]

- Briggs M, Nelson EA, Martyn-St James M. Topical agents or dressings for pain in venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11(11):CD001177. [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen B, Friis GJ, Gottrup F. Pain and quality of life for patients with venous leg ulcers: proof of concept of the efficacy of Biatain-Ibu, a new pain reducing wound dressing. Wound Repair Regen. 2006 May-Jun;14(3):233-9. [CrossRef]

- Gottrup F, Jørgensen B, Karlsmark T, Sibbald RG, Rimdeika R, Harding K, Price P, Venning V, Vowden P, Jünger M, Wortmann S, Sulcaite R, Vilkevicius G, Ahokas TL, Ettler K, Arenbergerova M. Less pain with Biatain-Ibu: initial findings from a randomised, controlled, double-blind clinical investigation on painful venous leg ulcers. Int Wound J. 2007 Apr;4 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):24-34. [CrossRef]

- Fogh K, Andersen MB, Bischoff-Mikkelsen M, Bause R, Zutt M, Schilling S, Schmutz JL, Borbujo J, Jimenez JA, Cartier H, Jørgensen B. Clinically relevant pain relief with an ibuprofen-releasing foam dressing: results from a randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial in exuding, painful venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2012 Nov-Dec;20(6):815-21. [CrossRef]

- Imbernon-Moya A, Ortiz-de Frutos FJ, Sanjuan-Alvarez M, Portero-Sanchez I, Merinero-Palomares R, Alcazar V. Pain and analgesic drugs in chronic venous ulcers with topical sevoflurane use. J Vasc Surg. 2018 Sep;68(3):830-835. [CrossRef]

- Latina R, Varrassi G, Di Biagio E, Giannarelli D, Gravante F, Paladini A, D’Angelo D, Iacorossi L, Martella C, Alvaro R, Ivziku D, Veronese N, Barbagallo M, Marchetti A, Notaro P, Terrenato I, Tarsitani G, De Marinis MG. Chronic Non-cancer Pain Management in a Tertiary Pain Clinic Network: a Retrospective Study. Pain Ther. 2023 Feb;12(1):151-164. Epub 2022 Oct 17. Erratum in: Pain Ther. 2023 Jun;12(3):891-892. doi: 10.1007/s40122-023-00503-3. [CrossRef]

- Nalamachu S, Mallick-Searle T, Adler J, Chan EK, Borgersen W, Lissin D. Multimodal Therapies for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain: The Role of Lidocaine Patches in Combination Therapy: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2025 Jun;14(3):865-879. [CrossRef]

- Simon DA, Dix FP, McCollum CN. Management of venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 2004 Jun 5;328(7452):1358-62. [CrossRef]

- Scallon C, Bell-Syer SE, Aziz Z. Flavonoids for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 May 31;2013(5):CD006477. [CrossRef]

- Li KX, Diendéré G, Galanaud JP, Mahjoub N, Kahn SR. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction for the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency, with a focus on postthrombotic syndrome: A narrative review. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021 May 8;5(4):e12527. [CrossRef]

- Gianesini S, De Luca L, Feodor T, Taha W, Bozkurt K, Lurie F. Cardiovascular Insights for the Appropriate Management of Chronic Venous Disease: A Narrative Review of Implications for the Use of Venoactive Drugs. Adv Ther. 2023 Dec;40(12):5137-5154. [CrossRef]

- Pasek J, Szajkowski S, Cieślar G. Quality of Life in Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers Treated by Means of Local Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy or Local Ozone Therapy-A Single Center Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 Nov 24;59(12):2071. [CrossRef]

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Interventions for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 2;3(3):CD008378. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Stechmiller J, Weaver M, James G, Stewart PS, Lyon D. Associations Among Wound-Related Factors Including Biofilm, Wound-Related Symptoms and Systemic Inflammation in Older Adults with Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2024 Oct;13(10):518-527. [CrossRef]

- Guest JF, Gerrish A, Ayoub N, Vowden K, Vowden P. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of three alternative compression systems used in the management of venous leg ulcers. Journal of wound care. 2015 Jul 2;24(7):300-10. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).