1. Introduction

Symmetry plays a central role in biology [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], mathematics [

11], physics [

12,

13], and chemistry [

14,

15], where it serves as a guiding principle for understanding structure, stability, and invariance. In crystallography, for example, the classification of atomic lattices is determined by symmetry groups [

16,

17], while in physics, conservation laws are intimately connected with symmetries through Noether’s theorem [

18,

19]. Finite sets of points with prescribed symmetries arise naturally in diverse contexts, including molecular geometry [

20], cluster formation [

21,

22,

23], coding theory [

24], and discrete models of physical systems [

25,

26,

27].

The question of symmetry stability—namely, how resistant a symmetric structure is to perturbations—has received considerable attention in various forms. Most existing approaches investigate deterministic stability, where specific points or components are removed or displaced, and one asks whether symmetry is preserved [

28]. Such studies are closely connected to structural rigidity, graph automorphisms, and geometric stability theory [

29]. However, in many realistic situations, perturbations occur randomly rather than deterministically. Instead, systems are exposed to random fluctuations, such as thermal noise in physical systems, random deletions in networks, mutations in biological molecules [

30], or stochastic failures in engineered structures.

This motivates the development of a probabilistic framework for measuring the robustness of symmetry under random deletions/perturbations. In our recent work, we considered symmetry stability of Jordan curves [

31]. In the present work, we extend the notion of symmetry stability to finite sets of points with nontrivial symmetry groups. Specifically, we consider the following problem: given a finite set of points together with its symmetry group, points are removed randomly and independently. We then ask: with what probability does such a removal destroy all nontrivial symmetry, reducing the symmetry group to the trivial group

?

We develop and formalize a probabilistic measure of symmetry stability for such finite point sets, and we provide explicit calculations for representative families of symmetric configurations. The method captures the interplay between local fragility (how easily a given configuration loses its symmetry under single deletions) and global resilience (the persistence of symmetry under multiple deletions).

Beyond its mathematical interest, this probabilistic perspective enriches classical symmetry analysis by incorporating randomness directly into the structural framework. It offers new conceptual insights and potential applications in crystallography, molecular stability, network resilience, coding theory, and other domains where symmetry governs stability but systems are inevitably subject to random perturbations.

2. Results

2.1. Introducing the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability

In our recent work we investigated the following question: given a symmetric Jordan curve, how many points must be removed in order to reduce its symmetry group to the trivial group

? We demonstrated that removing a single point suffices to reduce the symmetry group to

provided, that the point does not lie on an axis of symmetry of the curve [

31]. The only remarkable exception is the circle, for which this approach fails [

31].

However, this method does not extend directly to finite sets of points. For example, consider the vertices of a regular polygon: removing a single vertex does not reduce the symmetry group of the set to . In the present paper we extend the proposed approach to sets of points with nontrivial symmetry groups. Specifically, let a finite set of points be given together with its symmetry group, different from the trivial group . We reformulate the problem as follows: points are removed randomly and independently from the set. Let denote the probability that removing a single point reduces the symmetry group of the set to the trivial group . We define the probabilistic symmetry stability of the set under removal of one point denoted as:

(1)

Introduced with Eq. 1 measures how resistant the symmetry of the set is to the random removal of a single point. If , then almost always at least one symmetry survives when you delete one point. If , then deleting a single point almost always destroys all symmetry.

Analogously, let us denote the probability that random removing a pair of points reduces the symmetry group to . The corresponding probabilistic symmetry stability is defined with Eq. 2:

(2)

Introduced measures the robustness of the symmetry under the random removal of two points. More generally, let denote the probability that random removing N points from the set containing points, reduces the symmetry group to . We then define the symmetry stability in this case as:

(3)

is then the probability that some nontrivial symmetry still survives after random removing N points. In physics language, we can think of as an “order parameter” for symmetry stability, namely , means that symmetry is maximally stable under random removing N points. In turn, means that symmetry is fragile under random removing N points. So, the sequence provides a profile of the robustness of the symmetry group of the point set against random deletions.

First of all, note that for the random distribution of points the sequence is not defined. Indeed, the symmetry group of randomly distributed points is the trivial group We address a number of examples, in which the given location of points is described by the non-trivial symmetry group. Secondary, when we remain after deletion with a single point, characterized with the symmetry group for the planar configuration of points, whatever is their initial symmetry.

2.2. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for 2p Equidistant Points Placed on the Same Straight Line

Consider 2p points placed symmetrically on one straight line (equally spaced and symmetric about the center). The original symmetry of the point set is the two-element group , where is the reflection (or half-turn) that sends each point to its mirror partner. The 2p points form p mirror-pairs; because 2p is even there is no single point fixed by . Now we remove The only way the reflection can survive after removing a set R of points is that R is invariant under . For our configuration this means R must be a set of whole mirror-pairs. Equivalently: if we remove an odd number of points, cannot survive (because mirror-pairs have size 2), so symmetry is certainly destroyed.

If we remove (even) points, survives exactly when the removed set consists of r entire mirror-pairs. Now consider particular cases:

. Removing a single point leaves its partner unpaired, so no longer maps the remaining set to itself. Thus, we calculate . There are unordered pairs of points that could be removed. Exactly p of those pairs are mirror-pairs (one per mirror-pair). If the removed pair is one of these p pairs, the reflection survives; otherwise, symmetry is lost. So the probability that the removed pair is a mirror-pair is given by Eq. 4:

(4)

It is seen from Eq. 4 that the probabilistic measure of symmetry may be seen as the function of number p mirror-pairs, Quite expectedly and reasonably, Indeed, it is intuitively clear, that for a very large (or infinite) symmetric configuration the chance that a randomly chosen pair is exactly a mirror-pair tends to zero, so a random deletion almost surely destroys the reflection symmetry.

Correspondingly, for the probability we calculate:

(5)

It is easily seen that This is also intuitively clear: the probability of the reducing of the symmetry to group by deleting a random pair of points from infinite set of points tends to unity. The initial symmetry group of the set is ; for very large (or infinite) p, a randomly chosen pair is almost certainly not a mirror-pair, so a random deletion almost surely destroys the reflection symmetry.

Now consider the general case. If is odd, then, as already noted, . If N is even symmetry survives. if the removed points are exactly r whole mirror-pairs. The number of ways to choose r mirror-pairs to remove is The total number of choices of points to remove is Finally we calculate:

(6)

(7)

Finally, we establish:

(8)

2.3. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for Symmetrical Triangles

Consider the set of vertices of equilateral triangle possessing full dihedral group of symmetry of order six, number of vertices Remove one vertex . The remaining set has two points and nontrivial symmetry, described by dihedral group . Thus, we calculate Let us remove two vertices : the remaining set has 1 point, and nontrivial symmetry, described by the full orthogonal group . Thus, we establish . Similar results are true for isosceles triangles. We conclude that equilateral and isosceles triangles’ symmetry is maximally stable under deleting 1 or 2 vertices: we never (with the uniform choice model) end up with only the identity symmetry; consequently .

2.4. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for the Sets Built of Four Points

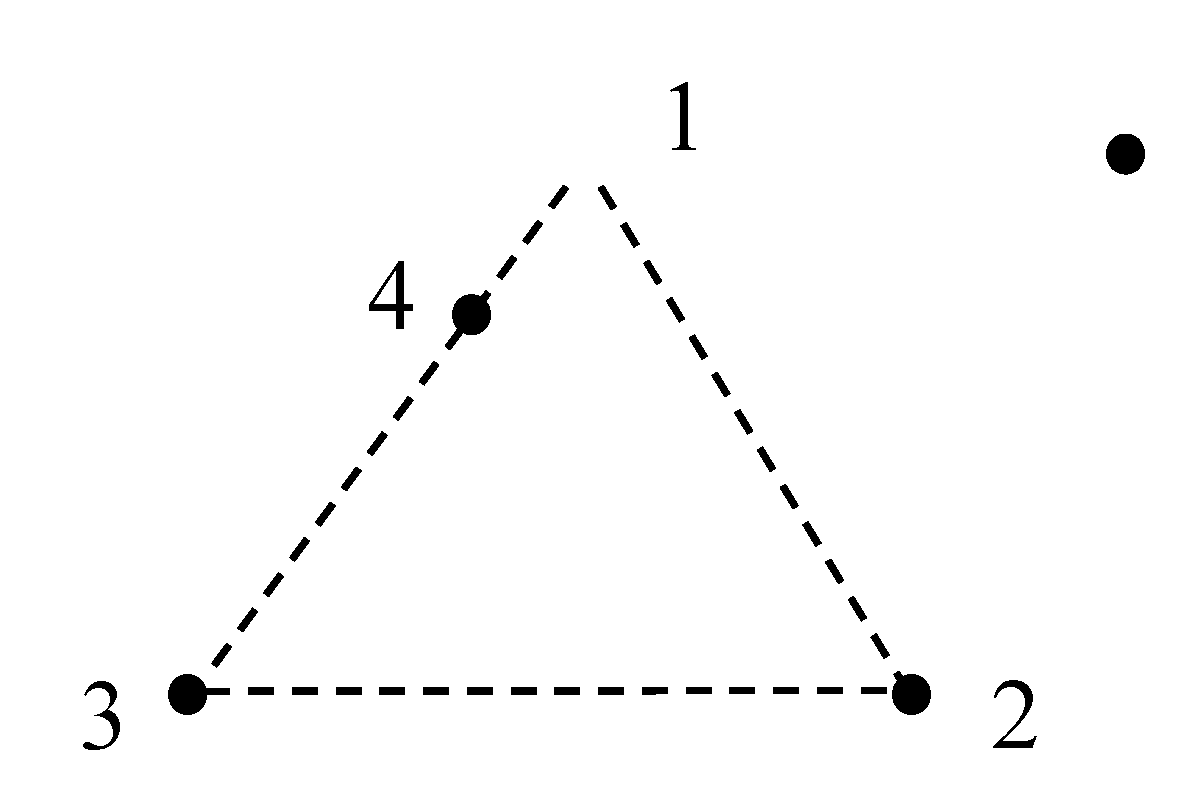

Consider the set of four points, denoted “1”, “2”, “3” and “4”, belonging to the same plane. Three of them, namely the points labeled “1”, “2” and “3” are vertices of equilateral triangle (see Figure 1). The fourth point, labeled “4”, lays on the side of the equilateral triangle and does not belong to the axis of symmetry of the triangle (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The set of four points, denoted “1”, “2”, “3” and “4” is depicted. Points labeled “1”, “2” and “3” are vertices of equilateral triangle. Point “4”, lays on the “13”of the equilateral triangle and does not belong to the axis of symmetry of the triangle. Dashed lines are supplied for eye guiding only.

Figure 1.

The set of four points, denoted “1”, “2”, “3” and “4” is depicted. Points labeled “1”, “2” and “3” are vertices of equilateral triangle. Point “4”, lays on the “13”of the equilateral triangle and does not belong to the axis of symmetry of the triangle. Dashed lines are supplied for eye guiding only.

We are going to calculate the set of probabilistic measures of the symmetry for the given set of points. Let us remove one point. If we remove point “4” (probability ), the remaining three points are the vertices “1”, “2” and “3” of an equilateral triangle possessing full nontrivial symmetry (group If we remove any one of 1”, “2” and “3” (total probability is ) the remaining three points are generically a scalene triple, or a non-symmetric collinear triple (points are collinear but not evenly spaced), when point “2” is removed, and have only the trivial symmetry . Thus, the probability that a nontrivial symmetry survives is , consequently . After removing two points, we always have exactly two distinct points left. Any unordered set of two distinct points in the plane has a nontrivial symmetry (it is preserved by the half-turn about their midpoint and reflections that swap them), so a nontrivial symmetry always survives. Therefore When we remove three points, one point survives characterized by nontrivial symmetry, described by the full orthogonal group O(2), hence , Eventually we summarize: Group O(2) appears because a single point is fixed by every isometry of the plane.

The same results remain true for the set of four points, when three of them are vertices of the isosceles triangle. The fourth point lays on the side of the triangle and does not belong to the axis of symmetry of the triangle. The same reasoning yields Now let us calculate the probabilistic measures of symmetry for the vertices of rectangle. When we remove one of its vertices the emerging triangle is scalene and therefore has no nontrivial symmetry (no reflection or rotation preserving it). Hence, every single-vertex deletion produces a remaining set whose symmetry group is thus, Now, we remove from the rectangle two points. The remaining set has exactly two distinct points. Any two distinct points admit a nontrivial symmetry that swaps them (reflection in the perpendicular bisector, or rotation about the midpoint). So the symmetry group of a 2-point set is nontrivial, hence we conclude Removing three vertices leaves a single point, described by the full orthogonal group . Eventually, . Consider, that unlike the equilateral/isoceles case, there is no deletion option that preserves a 3-point rotational symmetry.

2.5. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for Regular Polygons

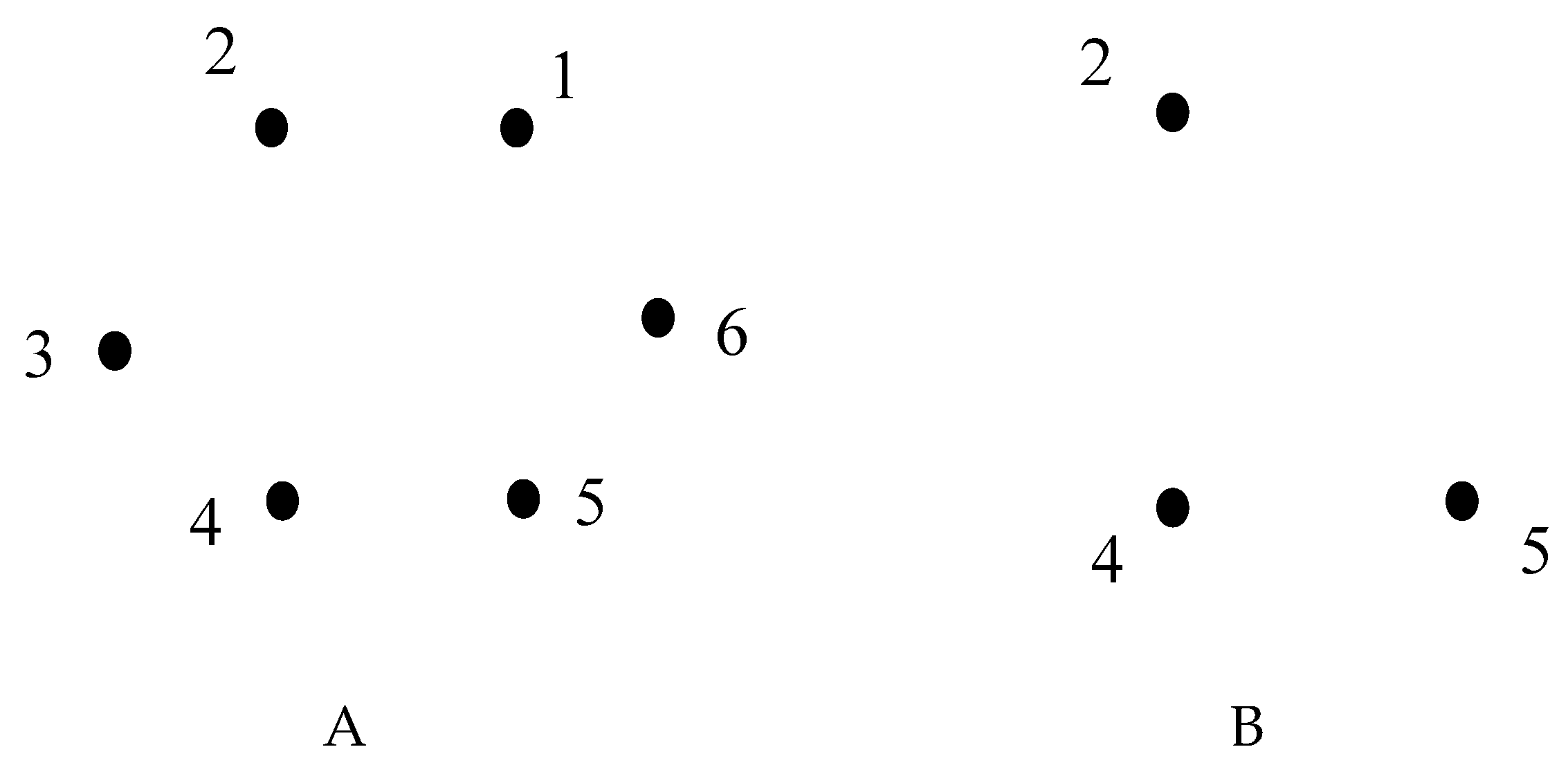

This is, perhaps, the most surprising result presented in the paper. It is simple to demonstrate that for regular quadrangles, and pentagons all of and all of , and the inductive thinking hints that this is true for the vertices of all of the regular polygons. However, this conclusion is wrong. Consider the vertices of the regular hexagon depicted in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

A. Vertices of regular hexagon numbered

Figure 2.

A. Vertices of regular hexagon numbered

are depicted. B. Points are removed. The emerging triangle is characterized by the trivial symmetry group .

Let us calculate explicitly. is defined as a probability that after deleting N vertices (chosen uniformly at random) the remaining set still has a nontrivial symmetry. Equivalently we re-shape in in Eq. 9:

, (9)

where is the number of deleted N-subsets, whose complementary has a nontrivial symmetry. We consider ; the cases and are trivial. It is easy to demonstrate that Consequently In other words removing of points reduces the symmetry of regular hexagon to the symmetry group different from the trivial group . We start from . Indeed, delete points “3” and “6”. We obtain the rectangle “1245”, and symmetry survives. Deleting adjacent points “1” and “2” remains the reflection symmetry untouched. Deleting adjacent points “1” and “4” also remains the reflection symmetry untouched. The same is true for other pairs points; hence The same check holds for The non-trivial result we obtain for , as illustrated with Figure 2B. Consider elimination of the triad of points numbered . The emerging scalene triangle denoted and depicted in inset B of Figure 2 possesses the trivial symmetry group .

Now let us calculate The number of total choices We must count the 3-vertex remaining sets (complements) that are symmetric. There are two types of symmetric 3-vertex patterns on the hexagon: Three consecutive vertices (a block of length 3). There are 6 such blocks (one starting at each vertex, wrapping around). Each gives a reflection symmetry (axis through the middle of the block). Every-other-vertex triangle (vertices , and ) has 3-fold rotation symmetry. There are two such triples. So total symmetric remaining 3-sets = 6+2=8. Therefore, Thus, there are 8 deleted 3-subsets whose complements are symmetric, hence . Thus, we conclude, that deleting points remains the symmetry of hexagon not-trivial, whereas, deleting of points may reduce the symmetry of hexagon to the trivial group, with Solution of the general problem for arbitrary regular polygons is complicated and challenging and we remain it unsolved.

2.6. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for Tetrahedron and Octahedron

It is instructive to extend the suggested idea for 3D shapes. Let us start from the calculation of the probabilistic measure of symmetry for the set of vertices of tetrahedron. The total number of vertices is: Only are allowed (). Let us start from When we remove one vertex, the remaining set is the three vertices of one face of the tetrahedron. Those three points are the vertices of an equilateral triangle, whose point-set symmetry group is nontrivial (dihedral . Therefore every single-vertex removal leaves a nontrivial symmetry, so the probability that the symmetry is reduced to the trivial group is . Now consider If we remove two vertices, the remaining set is built of two distinct points. Any two-point set has a nontrivial isometry exchanging the two points (reflection in the perpendicular bisector plane, or a half-turn about an appropriate axis), so its symmetry group is nontrivial (contains a swap of the two points). Thus, every pair removal leaves nontrivial symmetry, so . Now address Removing three vertices created the remaining set, containing a single point. A single point has nontrivial, infinite) symmetry group which is in 3D space the group which includes all rotations/reflections fixing that point), so . Thus, we conclude that the set of vertices of tetrahedron demonstrates remarkable stability of its symmetry against random removing its vertices. Similar calculations lead to the conclusion that for the vertices of octahedron, another Platonic solid.

2.7. Calculation of the Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability for Cubic Crystallographic Cells

Now, we address the structures important for crystallography [

16]. Let us start from the simple cubic lattice. It is easy to see that no matter which

vertices we delete from eight vertices, some nontrivial symmetry of the cube still preserves the remaining set. Hence the whole sequence of probabilistic measures of symmetry equals to unity, namely

. The same is true for the BCC and FCC cubic units (consider that the number of vertices will be different for these crystallographic systems). Thus, we conclude the simple cubic, FCC and BCC systems demonstrate remarkable stability/robustness of their symmetry. Calculation of the sequence of the probabilistic measures of the symmetry stability for HCP crystallographic cells represents a challenging mathematical task (see

Section 2.4).

2.8. Shannon Probabilistic Measure of the Symmetry Stability

The suggested probabilistic measure of the symmetry stability enables introducing the Shannon measure of the symmetry stability [

32,

33]. Consider a given finite set of points (the number of points in the set is

) together with its symmetry group, different from the trivial group

. Points are removed randomly and independently from the given set. Let

denote the probability that removing a single point reduces the symmetry group of the set to the trivial group

. More generally

denotes the probability that randomly removing

points from the set containing points reduces the symmetry group to

. The Shannon measure of the symmetry stability is defined with Eq. 9:

(9)

Let us explain Eq. 9. Removing points remains in the set a single point possessing the symmetry group , which is different from , hence . What is the meaning of the Shannon entropy introduced with Eq. 9?

The Shannon entropy defined in Eq. (9) can be interpreted as the average uncertainty associated with destroying the symmetry of the set through the elimination of points of all possible removal sizes. In other words, Sh quantifies the overall information-theoretic uncertainty associated with the full profile of probabilities .

Let us exemplify the introduced Shannon measure of the symmetry stability with its calculation for regular hexagon, addressed in

Section 2.4. It was demonstrated in

Section 2.4 that for the regular hexagon

Thus the Shannon measure of the symmetry stability for hexagon equals

. For regular triangles, quadrangles, and pentagons all of

hence

For rectangle

(see

Section 2.3), hence

For the configuration of points depicted in

Figure 1 we calculate:

3. Discussion

Classical symmetry studies (in geometry, crystallography [

16,

17,

34] , group theory, graph automorphisms) usually deal with exact symmetries: describing the full symmetry group of a configuration. They rarely ask how fragile that symmetry is under perturbations [

35]. Symmetry breaking is a fundamental concept in physics and chemistry (

e.g. phase transitions, molecules, crystal defects), but it is typically studied deterministically: you introduce a defect and check whether symmetry survives. The idea of quantifying the probability that symmetry survives after random perturbations seems unexplored in the mathematical literature. We introduce the probabilistic measure of the symmetry stability

which may be interpreted as a symmetry robustness metric for finite point-sets (including vertices of polygons, polyhedra, etc.). This makes introduced approach closer in spirit to “stability” concepts in graph theory and network science, but tailored to geometric symmetry groups. For regular polygons, Platonic solids, and other symmetric point-sets, one can compute

explicitly, which leads to new combinatorial results. This has potential connections with: probabilistic group theory (probability that a random subset has trivial stabilizer), Ramsey-type problems (minimal deletions that destroy structure), symmetry breaking in physics/chemistry (quantitative models of defect-induced asymmetry). Introduced

provides a bridge between deterministic symmetry (group theory) and random perturbations (probabilistic combinatorics / statistical physics).

Consider the following example, related to physics. We address the defect stability in crystalline solids, namely crystal lattices with high symmetry (cubic, hexagonal, etc.). Consider random perturbations of the lattice, such as: thermal motion, point defects (vacancies, interstitials), or irradiation damage randomly remove or displace atoms. Introduced probabilistic measure of symmetry

quantifies the probability that after introducing

N random vacancies the residual point configuration still preserves a nontrivial subgroup of the original space group. For example: a simple cubic lattice with a few vacancies often preserves inversion or rotational symmetries. And the same is true for FCC and BCC lattices But in more delicate lattices (like HCP), a single defect may destroy all nontrivial symmetry (see

Section 2.4, in which random breaking of symmetry of hexagon is treated). Thus, introduced

gives a statistical measure of symmetry robustness of a lattice, relevant for understanding defect tolerance, phonon spectra stability, and mechanical properties.

Let us envisage the directions of future investigations. The probabilistic framework for symmetry stability introduced in this work opens several promising avenues for further research, both theoretical and applied:

- i)

Extension to higher-dimensional and complex point sets. While we considered 2D polygons and 3D polyhedra, many systems of interest—such as quasicrystals, complex molecular clusters, and high-dimensional lattices—pose challenging combinatorial problems. Extending calculations to these structures could uncover novel symmetry robustness patterns.

- ii)

Study of probabilistic symmetry in dynamic systems. In physical and biological systems, perturbations often occur continuously rather than as discrete deletions. Developing a time-dependent or stochastic version of could quantify the resilience of symmetry under fluctuating forces, thermal noise, or dynamic defects. Study of the time evolution of is of a particular interest.

- iii)

Connection with statistical physics and phase transitions:

The Shannon measure of symmetry stability introduced with Eq. 9 suggests a link between symmetry robustness and information-theoretic order parameters. Investigating the relationship between and critical phenomena in disordered systems may provide a new perspective on symmetry breaking and defect-driven phase transitions.

- iv)

Systematic computation of for various crystal lattices (including HCP and more complicated structures) can inform defect-tolerance studies, mechanical stability, and design of robust nanostructures. The probabilistic framework could guide the development of materials resistant to random defects.

- v)

Integration with network theory and combinatorics looks attractive. Symmetry stability can be generalized to networks with geometric embedding, where nodes or edges are removed randomly. This opens potential connections with probabilistic graph theory, random automorphism groups, and combinatorial optimization.

- vi)

Algorithmic and computational development is instructive. Efficient algorithms for exact or approximate computation of the introduced and the Shannon symmetry entropy Sh for large or high-symmetry point sets will be crucial. Monte Carlo simulations, group-theoretic enumeration, and probabilistic combinatorial techniques can all play a role.

- vii)

Experimental validation of the suggested ideas is desirable. Measuring symmetry survival probabilities in real physical systems—such as nanoparticles under random vacancy formation, molecules with isotopic substitutions, or lattice defects under irradiation, could validate and calibrate the theoretical framework, bridging theory with experimental observation.

In summary, the introduced probabilistic approach to symmetry stability provides a versatile framework that can be expanded in multiple directions, linking combinatorial geometry, group theory, statistical physics, and applied materials science. Its future development promises both fundamental insights and practical applications in systems where symmetry is subject to randomness.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced a probabilistic framework for studying the stability of finite point-set symmetries under random perturbations. Instead of addressing symmetry breaking deterministically, as is usually done in geometry, crystallography, and physics, we defined the probability that the removal of N points reduces the symmetry group of a configuration to the trivial group and the complementary symmetry stability measure defined as . The resulting sequence ) characterizes the robustness of a given symmetric configuration to random deletions.

We demonstrated explicit calculations for several representative cases: symmetric linear arrays, equilateral and isosceles triangles, four-point configurations, rectangles, regular polygons, tetrahedron, octahedron and cubic crystallographic cells. These examples reveal both expected and surprising behaviors. For instance, cubes, tetrahedron and octahedron exhibit maximal robustness, with nontrivial symmetry always surviving the removal of any number of vertices, while regular hexagons display partial fragility, losing all symmetry with probability under the deletion of three vertices. Such results illustrate that symmetry stability is highly sensitive to both geometry and group structure of the given configuration of the points. Our results indicate that the proposed probabilistic symmetry stability captures both local vulnerability (symmetry-breaking caused by specific single deletions) and global persistence (the inevitability of nontrivial symmetry in sufficiently reduced systems). Indeed, once the system reduces to two or one point, these configurations inherently admit reflection or rotational invariances.

We also proposed a Shannon entropy measure of symmetry stability, which captures the overall information-theoretic uncertainty of symmetry breaking across all deletion sizes. This connects probabilistic symmetry stability with broader concepts in statistical physics and information theory.

The introduced framework provides a bridge between deterministic group-theoretic symmetry analysis and probabilistic models of random perturbations. It offers a quantitative language for discussing the robustness of symmetry in systems ranging from molecular clusters and nanoparticles to crystallographic lattices and disordered networks. Beyond the explicit examples treated here, the approach suggests new directions for research in probabilistic group theory, combinatorial geometry, and the physics of defect-induced symmetry breaking. We believe that the suggested framework provides both a unifying language and a flexible tool for studying how symmetry persists - or collapses - under the unavoidable randomness present in natural and engineered systems.