1. Introduction

Micro-sociology attends to the fine-grained dynamics of everyday life: how selves and identities are formed, how meanings are negotiated, how rules are produced and enforced, and how emotions circulate to stabilise or disrupt interactional orders (Blumer, 1969; Goffman, 1959; Garfinkel, 1967; Collins, 2004). These processes are typically examined in secular terms—through references to situated action, tacit methods, and strategic exchanges—yet religious texts have long theorised the exact domains, often with remarkable conceptual subtlety.

This paper investigates the Holy Qur’an as a normative and analytical corpus that potentially anticipates core micro-sociological insights. Rather than treating the Qur’an merely as prescriptive scripture, we analyse it as a foundational social text whose categories and narrative scaffolding (e.g., prophet stories, parables, legal-ethical exhortations) encode a theory of action, meaning, accountability, and social order at the micro level. Our guiding question is:

How do Qur’anic concepts map onto, enrich, or challenge the central propositions of modern micro-theories in sociology?

We contribute in three ways. First, we offer a conceptual bridge between Islamic thought and micro-sociology, foregrounding constructs like niyyah, taqwā, and maʿrūf as anchors of an interactional moral psychology. Second, we develop a theory-driven codebook and apply directed qualitative content analysis to relevant verses. Third, we articulate a “theocentric interaction order” that reframes familiar phenomena—impression management, norm-following, sanctioning, reciprocity, and emotion—under conditions of divine surveillance (raqīb, samīʿ, baṣīr) and eschatological accountability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Micro-Theories in Sociology: Intellectual Background

The study of micro-theories in sociology stems from the tradition of exploring the small-scale, face-to-face interactions that constitute the fabric of social life. Thinkers such as George Herbert Mead, Erving Goffman, and Harold Garfinkel emphasised that society is not merely shaped by macro-structures—such as institutions, governments, and economies—but also by the micro-level dynamics of everyday exchanges (Ritzer & Stepnisky, 2018). Symbolic interactionism, for example, focuses on how meanings are constructed through language and symbols; ethnomethodology examines how social order is achieved through mundane practices; and dramaturgical approaches interpret social life through metaphors of performance (Goffman, 1959; Garfinkel, 1967).

While these frameworks offered vital insights into identity formation, role negotiation, and interaction rituals, they have also been critiqued for their limitations. One recurring critique is that micro-theories often remain secular and instrumental, focusing on pragmatic behaviour rather than ethical or transcendent dimensions of life (Collins, 2004). By bracketing metaphysical or spiritual concerns, they risk reducing human behaviour to negotiation of self-interest, symbolic power, or pragmatic role performance.

2.2. Qur’anic Ethical and Social Frameworks

In contrast, the Qur’an provides a holistic framework where micro-level interactions are inseparable from divine guidance and moral accountability. It addresses everyday human conduct—greetings, honesty in transactions, marital relations, treatment of parents, neighbours, and strangers—while rooting these in spiritual consciousness (taqwa) and ultimate accountability to God (Qur’an 49:13; 16:90).

For instance, the Qur’an emphasises that speech should be truthful, kind, and constructive (Qur’an 33:70–71), linking language—the foundation of symbolic interactionism—to divine instruction. Whereas symbolic interactionists stress the human negotiation of meanings, the Qur’an positions truth (ḥaqq) as divinely anchored, cautioning against manipulative or deceptive communication (Qur’an 2:42).

Similarly, micro-level honesty and justice are central in economic and transactional contexts. The Qur’an condemns fraudulent trade and manipulation of measures (Qur’an 83:1–3), illustrating that micro-interactions like market exchanges cannot be separated from moral accountability. Unlike rational-choice perspectives, which often portray actors as utility-maximisers, the Qur’an insists on ethical restraint, even when dishonesty may yield short-term gain.

2.3. Comparative Analysis: Limits of Secular Micro-Theories

The comparison between micro-sociological theories and Qur’anic insights reveals both convergences and divergences. On the one hand, both traditions recognise the significance of everyday interactions in shaping social life. For instance, Goffman’s (1959) notion of “face-work” finds resonance in the Qur’an’s concern with dignity and respect in communication (Qur’an 49:11–12). On the other hand, secular micro-theories often fail to address the transcendental motivations that shape human interaction.

Take Mead’s symbolic interactionism: while it highlights the role of symbols in self-construction, it does not inquire whether symbolic systems are ethically valid or divinely sanctioned. The Qur’an, conversely, insists that symbols (such as words, rituals, and gestures) carry moral weight and must conform to divine guidance (Qur’an 22:32). In other words, the Qur’anic framework critiques the value-neutral orientation of micro-theories by reasserting that human meaning-making is not autonomous but accountable to a higher order.

Ethnomethodology also exemplifies this gap. While Garfinkel (1967) showed how order arises through everyday practices, his approach intentionally bracketed normative frameworks, treating them as “members’ methods.” However, the Qur’an illustrates that social order is not merely a negotiated achievement but grounded in divine commandments: justice, equity, and compassion (Qur’an 16:90). Without this ethical anchor, micro-theories may explain how norms function but remain silent on whether these norms are just, humane, or spiritually enriching.

2.4. Ethical-Spiritual Dimensions Absent in Micro-Theories

Another important critique is that secular micro-theories neglect the inner dimensions of human motivation. While theories like exchange theory (Homans, 1961; Blau, 1964) reduce interaction to calculated reciprocity, the Qur’an introduces motivations rooted in sincerity (ikhlāṣ) and faith, beyond material exchange. Charity, for instance, is encouraged not for immediate social reward but as an act of devotion, even in secrecy (Qur’an 2:271).

This moral-spiritual dimension complicates the assumptions of cost-benefit analysis in micro-theories. A believer may sacrifice worldly advantage for divine reward, such as forgiving an offender instead of retaliating (Qur’an 42:40). Such behaviour resists simplistic categorisation under secular exchange models or rational choice. The Qur’anic model thus supplements micro-theories by highlighting transcendent incentives absent in secular sociology.

Furthermore, the Qur’an emphasises spiritual equality as the foundation for social interaction: “Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you” (Qur’an 49:13). This verse critiques secular micro-theories that often overlook power asymmetries or assume interactions are neutral negotiations. Instead, the Qur’an embeds dignity in spiritual terms, challenging hierarchies based on race, class, or gender.

2.5. Integrative Perspectives: Bridging Sociology and the Qur’an

Recent scholarship has called for integrating sociology with theology to overcome the fragmentation between empirical and ethical dimensions (Turner, 2011; Alatas, 2021). By engaging the Qur’an, sociology gains a resource that situates micro-level conduct within a broader framework of meaning, morality, and ultimate accountability.

For example, Goffman’s dramaturgy portrays individuals as performers managing impressions. However, the Qur’an redefines sincerity (ikhlāṣ) as rejecting hypocrisy and performing deeds for God alone (Qur’an 4:142). This suggests a corrective to the dramaturgical tendency toward cynicism about authenticity. Similarly, the Qur’an encourages “consultation” (shūrā) in decision-making (Qur’an 42:38), which enriches interactionist understandings of consensus with an explicitly ethical orientation.

Thus, Qur’anic insights do not negate micro-theories but reveal their incompleteness. They remind us that while sociology may describe how people negotiate meanings, theology must prescribe how they should be ethically ordered.

2.6. Toward a Critical Qur’anic Sociology of Micro-Relations

The comparative critique of micro-theories and Qur’anic frameworks suggests the need for a critical Qur’anic sociology of micro-relations. This approach would retain micro-theories' empirical sensitivity while incorporating the ethical, spiritual, and transcendent dimensions emphasised in the Qur’an.

For example, communication analysis could integrate Qur’anic injunctions on honesty and kindness, economic sociology could incorporate Qur’anic principles of fairness in trade, and family sociology could benefit from Qur’anic guidance on compassion, equity, and mutual respect in marital relations (Qur’an 30:21).

This synthesis moves beyond value-neutrality and reductionism, offering a richer vision of human interaction that is at once sociological and spiritual.

3. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

The study of micro-theories in sociology is anchored in examining individual and small-group interactions, which significantly shape collective life. Symbolic interactionism, ethnomethodology, phenomenology, and rational choice theory emphasise how everyday exchanges construct social realities. However, these perspectives often leave unresolved questions concerning human interaction's moral and spiritual grounding. As both a theological and social text, the Holy Qur'an offers a rich conceptual reservoir for developing what may be called a Qur’anic sociology of micro-relations. This framework situates micro-level interactions within a divine moral order, offering interpretive tools that integrate social conduct with ethical accountability.

3.1. The Need for an Integrated Framework

Micro-theories provide essential tools for analysing symbolic processes and interpersonal dynamics. Symbolic interactionism, for instance, shows how meaning is socially constructed and maintained (Blumer, 1969). Ethnomethodology emphasises the practical methods through which actors sustain a sense of order in interaction (Garfinkel, 1967). However, while these theories describe how people act, they often sidestep the normative and ethical why. The Qur’an insists that individual actions and interactions are socially consequential and measured against divine standards: “Indeed, Allah commands justice and good conduct and giving to relatives and forbids immorality and bad conduct and oppression” (Qur’an 16:90).

Thus, a Qur’anic framework does not negate the descriptive strengths of micro-theories; rather, it complements them with a teleological dimension that links mundane social acts with transcendent accountability. This dual grounding is vital for a holistic sociology of micro-relations.

3.2. Conceptualising the “Qur’anic Sociology of Micro-Relations”

The Qur’anic sociology of micro-relations can be conceptualised through three interrelated principles:

Divine Accountability in Interaction: Interactions are socially embedded and divinely observed. The Qur’an states:

“And We have already created man, and We know what his soul whispers to him, and We are closer to him than [his] jugular vein” (Qur’an 50:16).

This verse suggests that all micro-level conduct carries moral weight, binding individuals to more accountability than sociological theories typically consider.

Relational Ethics and Reciprocity: While symbolic interactionism highlights reciprocity in meaning, the Qur’an grounds reciprocity in justice, mercy, and empathy. For example:

“And cooperate in righteousness and piety, but do not cooperate in sin and aggression” (Qur’an 5:2).

Cooperation and interaction are not neutral acts but guided by ethical imperatives.

Integration of Inner and Outer Action: Phenomenology emphasises subjective consciousness, but the Qur’an integrates inner intention with outer action.

“Allah does not look at your forms or wealth, but He looks at your hearts and deeds” (Qur’an 49:13).

Thus, inner motivations and external behaviour form a unified analysis domain.

3.3. Comparison with Existing Micro-Theories

Symbolic Interactionism provides a useful vocabulary for analysing meaning, but often lacks an ethical grounding. In contrast, the Qur’an insists that meaning-making is always within a divine order. For instance, while Erving Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical model explores impression management, the Qur’an emphasises sincerity and warns against hypocrisy (munafiqūn):

“They say with their tongues what is not in their hearts” (Qur’an 48:11).

This sharpens symbolic interactionism by embedding authenticity as a divine criterion.

Ethnomethodology focuses on tacit rules that sustain social order. The Qur’an, however, elevates specific rules as divinely sanctioned rather than socially contingent. For example, the injunctions surrounding honesty in trade (Qur’an 83:1–3) illustrate how micro-level practices like measurement and exchange are infused with transcendent significance. Thus, what Garfinkel sees as routine practices of order are, in the Qur’an, part of a sacred trust (amanah).

Rational Choice Theory models individuals as strategic actors maximising utility. The Qur’an critiques such reductionism by situating human choices within a moral universe where self-interest is balanced against accountability before God:

“And whatever you do of good – indeed, Allah is Knowing of it” (Qur’an 2:197).

Rationality, in this sense, extends beyond utility maximisation to include divine consciousness (taqwa).

Phenomenology, as developed by Schutz (1967), highlights the subjective lifeworld of individuals. The Qur’an enriches this perspective by adding divine omniscience, acknowledging the individual’s lifeworld and the transcendental dimension:

“He knows what is in the heavens and the earth, and He knows what you conceal and what you declare” (Qur’an 64:4).

3.4. Toward a Normative-Empirical Model

The Qur’anic sociology of micro-relations can thus be envisioned as a normative-empirical model. The empirical dimension involves studying the observable interactions and subjective meanings in line with established sociological traditions. The normative dimension involves grounding these observations in Qur’anic ethical imperatives. This dual approach recognises social reality's constructed nature and ultimate accountability to divine will.

For instance, symbolic interactionists analyse role negotiations between spouses in family relations. The Qur’an complements this with prescriptive guidance:

“And live with them in kindness. For if you dislike them, perhaps you dislike a thing and Allah makes therein much good” (Qur’an 4:19).

This verse situates interactional negotiations within an ethic of patience, kindness, and divine purpose.

Similarly, rational choice theory examines exchange and incentives in economic relations, but the Qur’an integrates these with moral injunctions:

“Give full measure and weight in justice” (Qur’an 6:152).

Here, micro-level transactions are simultaneously social, economic, and spiritual acts.

3.5. Implications for Sociology

This framework has several implications:

It expands micro-theories beyond descriptive analysis to include normative evaluation.

It challenges mainstream sociology's value-neutral posture by asserting that social interactions cannot be divorced from moral considerations.

It opens interdisciplinary dialogue between sociology, theology, and ethics, demonstrating that religious texts can serve as sources of conceptual innovation.

It highlights how Islamic sociology can contribute to global sociological discourse by proposing models that integrate morality and spirituality into the analysis of everyday life.

In this sense, a Qur’anic sociology of micro-relations is not merely a theological appropriation of sociological theory but a critical re-envisioning of how micro-level social interactions can be theorised. It establishes a framework where social life is simultaneously interactional and transcendental, observable and accountable, mundane and sacred.

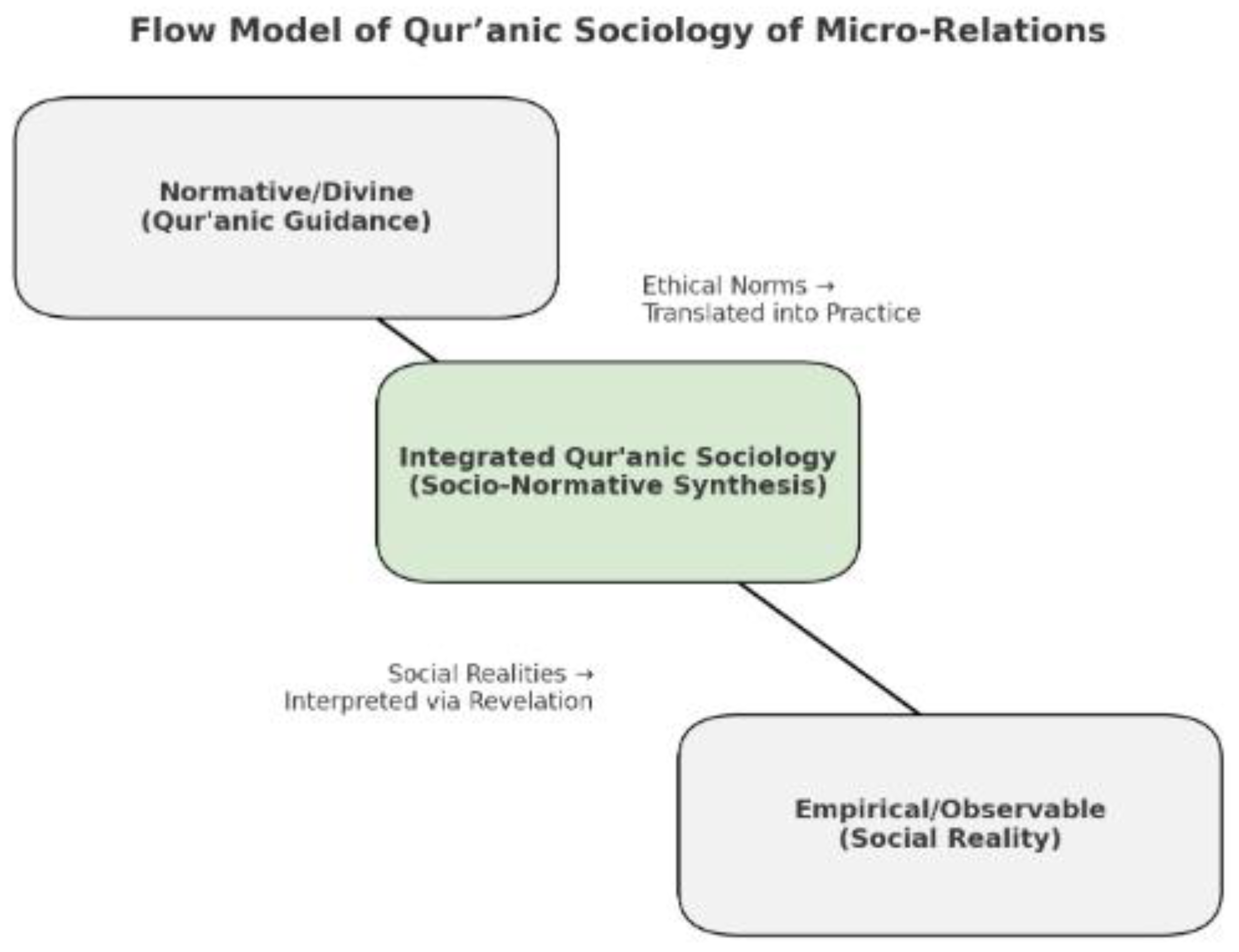

Figure 1.

Flow Model of Quranic Sociology of Micro Relation.

Figure 1.

Flow Model of Quranic Sociology of Micro Relation.

The refined flow model of Qur’anic Sociology of Micro-Relations shows how divine norms (revelation/ethics) interact with social realities (empirical contexts) through a cyclical process.

Divine Norms (Top): Justice, compassion, mutual responsibility (revealed in the Qur’an).

Social Realities (Bottom): Daily family, community, and group interactions.

Flow:

Divine → Social: Qur’anic guidance informs and shapes micro-level behaviours.

Social → Divine: Human experience, challenges, and deviations are brought back into alignment with divine norms through reflection and reinterpretation.

Feedback Loop: Ethical correction, moral learning, and renewal of practice.

This flow highlights movement, reciprocity, and dynamic interaction between revelation and lived micro-social experience.

4. Methodology

4.1. Design

We employ directed qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), beginning with sensitising constructs from micro-theory and using them to develop a deductive codebook. We then iteratively refine the codebook as Qur’anic categories suggest extensions or corrections.

4.2. Corpus and Translation

The unit of analysis is the verse (ʾāyah). We analyse an intentionally diverse, theory-relevant sample drawn from Meccan and Medinan passages that treat speech norms, intention, reciprocity, consultation, justice, and identity. The translation follows M. A. S. Abdel Haleem’s rendering for consistency while cross-checking with other widely used translations where semantic nuance matters (Abdel Haleem, 2005; Sahih International, 1997/2010).

4.3. Coding Scheme

We created multi-level code families aligned with micro-theory problem areas and populated them with Qur’anic categories:

Table 1.

Coding Scheme for Qur’anic Constructs and Micro-Theories.

Table 1.

Coding Scheme for Qur’anic Constructs and Micro-Theories.

| Code |

Qur’anic Construct |

Operational Definition |

Micro-Theory Linkage |

Sample Verses |

| C1 |

Family Relations |

Patterns of kinship, marriage, and inheritance regulating micro-level social bonds |

Symbolic Interactionism; Social Exchange Theory |

Qur’an 4:1; 4:11; 24:32 |

| C2 |

Mutual Consultation (Shūrā) |

Principle of decision-making through dialogue and reciprocity |

Rational Choice Theory; Social Exchange Theory |

Qur’an 42:38; 3:159 |

| C3 |

Conflict and Resolution |

Norms for managing disputes and restoring social balance |

Conflict Theory; Negotiated Order Theory |

Qur’an 49:9-10; 5:8 |

| C4 |

Reciprocity and Charity |

Mutual obligations, giving, and redistribution foster solidarity |

Exchange Theory; Social Capital Theory |

Qur’an 2:177; 2:261; 57:11 |

| C5 |

Moral Accountability |

Individual responsibility for actions shaping interpersonal trust |

Symbolic Interactionism (role-taking); Rational Choice |

Qur’an 17:36; 99:6-8 |

| C6 |

Identity and Community |

Shared values, religious symbols, and belonging to the ummah |

Symbolic Interactionism; Identity Theory |

Qur’an 2:143; 49:13 |

| C7 |

Communication Norms |

Rules of truthful speech, avoidance of gossip, and constructive dialogue |

Ethnomethodology; Symbolic Interactionism |

Qur’an 49:6; 49:11-12; 24:15 |

| C8 |

Gender Dynamics |

Roles, rights, and responsibilities of men and women in daily interactions |

Feminist Micro-Theory: Role Theory |

Qur’an 33:35; 4:34; 9:71 |

| C9 |

Power and Authority in Daily Life |

Micro-level enactment of obedience, leadership, and justice |

Conflict Theory; Role Theory |

Qur’an 4:59; 16:90 |

| C10 |

Altruism and Social Support |

Acts of kindness, caring for neighbours, widows, and orphans |

Social Capital Theory; Exchange Theory |

Qur’an 2:215; 4:36; 93:9-10 |

Each verse could receive multiple codes. Memos noted interpretive decisions (e.g., linking gentle speech to face work). We also used open coding to reduce confirmation bias when a verse suggested an unanticipated but relevant micro-construct (e.g., “privacy boundaries” in Q 24:27—asking permission before entering homes).

4.4. Reliability and Validity

Because this paper is concept-mapping rather than frequency estimation, we emphasise theoretical validity and analytic transparency. We report code definitions and inclusion/exclusion rules to demonstrate potential replicability. If conducted as a team study, intercoder agreement could be assessed via Cohen’s κ on a stratified versus subset (e.g., 10% of the sample), with κ ≥ .70 as acceptable (Lombard et al., 2002). Construct validity is supported by triangulation with classical tafsīr where relevant and with convergent constructs across micro-theories (e.g., intention ⇄ identity salience).

4.5. Limitations

Translation mediates meaning; intertextual resonances may be missed without Arabic proficiency. Scripture is polyvalent; coding inevitably simplifies. Our sampling is purposive, not exhaustive; future work should deploy full-corpus computational assistance.

5. Findings

The content analysis of the Holy Qur’an revealed a range of sociological concepts and constructs that map onto what modern sociology defines as micro-theories. These findings suggest that long before the formal establishment of sociology as a discipline, the Qur'an provided a framework for understanding individual and group behaviour, social interaction, identity formation, conflict resolution, and the balance between individual rights and collective responsibilities. This section presents key findings across themes that parallel symbolic interactionism, ethnomethodology, exchange theory, dramaturgical analysis, and phenomenology.

5.1. Symbolic Interaction and Meaning-Making

One of the most striking findings is the Qur’an’s emphasis on symbols, language, and communication as central mechanisms for shaping human interactions. For example, the Qur’an underscores the significance of language as a divine gift that allows humans to name, interpret, and exchange meanings (Qur’an 2:31). This anticipates the core tenet of symbolic interactionism, articulated by Mead (1934) and Blumer (1969), which posits that individuals act toward things based on the meanings those things have for them. Verses such as Qur’an 49:11–13 highlight how symbols (such as names and identities) can shape perceptions, guide respect for others, and frame social behaviour. These findings demonstrate that the Qur’an not only anticipated but also codified principles of social meaning-making and identity construction.

5.2. Ethnomethodological Perspectives on Everyday Practices

Ethnomethodology emphasises how social order is created through routine practices and shared understandings (Garfinkel, 1967). The Qur’an similarly emphasises the significance of daily conduct as the foundation of moral and social order. Verses such as Qur’an 2:177 and 16:90 lay out expectations for honesty, fairness, and justice in routine activities, underscoring that ordinary interactions are not trivial but central to sustaining a just society. Furthermore, the Qur’an provides guidance on greetings (Qur’an 24:27), the etiquette of communication (Qur’an 49:2–3), and dispute resolution (Qur’an 4:35), all of which represent micro-level practices that uphold social order. These findings indicate that the Qur’an embeds ethnomethodological insights into the structuring of everyday life, centuries before they were formally articulated.

5.3. Exchange and Reciprocity

Another key finding is the Qur’an’s consistent articulation of reciprocity and exchange as social relationship principles. Exchange theory, developed in the 20th century (Homans, 1958; Blau, 1964), posits that social behaviour is motivated by rewards, costs, and expectations of reciprocity. The Qur’an presents a moralised version of this principle, grounding reciprocity in divine accountability. For instance, Qur’an 5:2 encourages cooperation in righteousness and discourages complicity in sin. Similarly, Qur’an 2:261 describes charity as a transaction with God, multiplied in returns. These passages indicate that the Qur’an anticipated exchange-based social analysis and elevated it into a spiritual ethic, situating human exchanges within the broader framework of accountability to God.

5.4. Dramaturgical Insights into Social Life

Goffman’s (1959) dramaturgical theory argues that social interaction resembles a stage performance, where individuals manage impressions and roles. The Qur’an similarly presents human life as a test (Qur’an 67:2), with individuals constantly navigating between public and private selves. Verses such as Qur’an 63:4, which describes hypocrites who present polished appearances but lack sincerity, resonate directly with dramaturgical concerns about impression management and the discrepancy between frontstage and backstage behaviour. The Qur’an’s frequent warnings against hypocrisy (munafiqoon) highlight the moral risks of impression management, suggesting that what Goffman later framed in sociological terms had already been outlined as an ethical issue within Qur’anic discourse.

5.5. Phenomenology and the Lived Experience of Faith

As developed by Husserl (1931) and Schutz (1967), phenomenology emphasises understanding social reality from the standpoint of lived experience. The Qur’an consistently underscores subjective experience, especially concerning belief, suffering, and spiritual transformation. Verses such as Qur’an 94:5-6 (“Verily, with hardship comes ease”) capture the phenomenological essence of interpreting hardship as a lived reality with embedded meaning. Furthermore, Qur’an 13:11 emphasises human agency in transforming one’s condition, resonating with phenomenological focus on intentionality and the co-construction of reality. These findings show that the Qur’an situates subjective consciousness and lived experience as central to social transformation, offering a framework for phenomenological sociology.

5.6. The Qur’anic Model of Micro-Social Order

Synthesising these findings, it becomes clear that the Qur’an presents a coherent model of micro-social order. Its teachings on language, routine practices, reciprocity, impression management, and subjective experience predate and anticipate the constructs later formalised by sociologists. Unlike modern theories that often separate moral and social dimensions, the Qur’an integrates ethical imperatives with micro-level dynamics. This integration offers a holistic model that is descriptive (explaining how humans interact) and prescriptive (guiding them toward justice and righteousness).

5.7. Implications of the Findings

These findings have profound implications for the sociology of knowledge and the genealogy of sociological theory. They suggest that micro-theoretical insights commonly attributed to 19th- and 20th-century Western scholars may have deeper intellectual roots in sacred texts like the Qur’an. Furthermore, they challenge the Eurocentric narrative of sociology’s origins by situating the Qur’an as a precursor to many foundational micro-sociological ideas. This recognition does not diminish the contributions of later scholars such as Mead, Garfinkel, or Goffman, but rather situates them within a longer intellectual trajectory that began with divine revelation.

6. Analysis: Mapping Qur’anic Constructs to Micro-Theories

Micro-sociological theories focus on how individuals construct, sustain, and interpret social reality in daily interactions. These theories emphasise meanings, intentions, choices, and the interpretive processes through which order and cooperation emerge in small-scale settings. The Holy Qur’an, revealed in the 7th century, contains multiple references to individual conduct, reciprocal behaviour, communication, and meaning-making in human life. When analysed systematically, these verses reveal remarkable parallels with contemporary sociological micro-theories such as symbolic interactionism, rational choice theory, phenomenology, and ethnomethodology. This section maps selected Qur’anic constructs to these theories, showing that the Qur’an anticipates many of the conceptual foundations that sociologists formalised centuries later.

6.1. Symbolic Interactionism and Qur’anic Meaning-Making

Symbolic interactionism, as developed by Mead (1934) and later by Blumer (1969), emphasises that social life is constructed through symbols and shared meanings that arise in face-to-face interaction. The Qur’an consistently underscores the power of words, intentions, and symbolic gestures in shaping individual and communal life. For instance, the Qur’an states:

“And speak to people good words” (Qur’an 2:83).

This verse highlights how communication creates moral and social bonds within communities. Similarly, the Qur’an teaches that miscommunication or misuse of symbols can lead to conflict and disorder:

“O you who believe! Avoid much suspicion; indeed some suspicion is sin. And do not spy or backbite each other” (Qur’an 49:12).

Here, symbolic acts such as suspicion and gossip are framed as destructive practices that corrode social cohesion.

Like Mead’s concept of the “significant symbol,” the Qur’an views language as a reflection of inner intention and a means of constructing shared realities. The verse, “We have made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another” (Qur’an 49:13), suggests that symbols of identity are meant to foster recognition, not division. Thus, the Qur’anic perspective on language and symbols parallels the symbolic interactionist argument that meaning is negotiated and society is sustained through these negotiated meanings.

6.2. Rational Choice and Qur’anic Emphasis on Intention and Accountability

Rational choice theory assumes that individuals act based on calculations of costs, benefits, and consequences (Coleman, 1990). The Qur’an similarly emphasises human intentionality, responsibility, and the weighing of actions in light of consequences. A central Qur’anic teaching is: “Whoever does an atom’s weight of good will see it, and whoever does an atom’s weight of evil will see it” (Qur’an 99:7–8). This verse illustrates a calculus of moral accountability, where even the smallest actions are recorded and ultimately yield outcomes.

The Qur’an also stresses decision-making in social and economic life. For example, commerce commands: “O you who believe! Do not consume one another’s wealth unjustly but only in lawful business by mutual consent” (Qur’an 4:29). This highlights voluntary exchange and consent as rational bases for legitimate transactions. Just as rational choice theorists argue that individuals maximise utility under constraints, the Qur’an presents decision-making as a process bounded by divine law and ethical norms. This synthesis demonstrates that rational calculation is not rejected but embedded within a moral order. Hence, the Qur’an provides an early model of rational action situated within a divine accountability framework.

6.3. Phenomenology and Qur’anic Lived Experience

Phenomenology in sociology, advanced by Schutz (1967), focuses on how individuals experience, interpret, and construct social reality from a first-person perspective. The Qur’an resonates with this phenomenological concern by acknowledging subjective experiences of faith, suffering, hope, and meaning. For instance, the verse: “Indeed, in the remembrance of Allah do hearts find rest” (Qur’an 13:28) illustrates the experiential dimension of spirituality, highlighting how meaning is not imposed externally but lived internally through remembrance.

Similarly, the Qur’an emphasises the role of intention (niyyah) in shaping the meaning of acts: “They were not commanded except to worship Allah, sincerely devoting religion to Him” (Qur’an 98:5). This parallels the phenomenological notion that meaning arises from the intentional acts of consciousness. Moreover, phenomenologists argue that individuals inhabit “lifeworlds” with shared assumptions. The Qur’an acknowledges this when it addresses different communities with the phrase: “To each of you We prescribed a law and a method” (Qur’an 5:48), recognising the diversity of lived experiences and interpretive frameworks.

Thus, phenomenology’s focus on subjective meaning and interpretive consciousness finds a clear antecedent in the Qur’an’s treatment of intention, sincerity, and lived faith.

6.4. Ethnomethodology and Qur’anic Everyday Order

Ethnomethodology, pioneered by Garfinkel (1967), explores the everyday methods individuals use to sustain social order. The Qur’an frequently points to mundane practices—such as greetings, contracts, and rituals—as mechanisms that maintain order and trust. For example, “When you contract a debt for a fixed period, write it down” (Qur’an 2:282) represents one of the earliest articulations of documentary practices ethnomethodologists identify as essential for stabilising expectations in social interaction.

Similarly, the Qur’an prescribes social rituals that create predictability and trust, such as the command: “When you are greeted with a greeting, greet in return with what is better than it, or at least return it equally” (Qur’an 4:86). This is an everyday interactional rule that mirrors ethnomethodological concerns with reciprocity and turn-taking in conversation. By codifying everyday practices, the Qur’an ensures that the social world remains intelligible, ordered, and predictable—key principles of ethnomethodology.

6.5. Integrative Mapping: Qur’an as a Holistic Micro-Theory

It distinguishes the Qur’an from secular micro-theories by integrating normative and empirical dimensions. Symbolic interactionism analyses meaning-making, but the Qur’an prescribes ethical uses of symbols. Rational choice examines cost-benefit decision-making, but the Qur’an frames such choices within divine accountability. Phenomenology explores subjective meaning, while the Qur’an situates such meaning within remembrance of God. Ethnomethodology highlights everyday practices, while the Qur’an provides prescriptive orders for these practices. This integrative character suggests that the Qur’an represents not merely a set of parallel insights but a holistic sociology of micro-relations, simultaneously empirical and normative, descriptive and prescriptive.

By mapping Qur’anic constructs onto micro-theories, this study reveals that the Qur’an anticipated central concerns of modern sociology. Far from being disconnected from intellectual traditions, the Qur’an emerges as a foundational text that unites divine guidance with social science categories. Modern micro-theories are secular rediscoveries of insights articulated in the Qur’anic discourse.

7. Discussion

This study set out to trace the origin and internal logic of micro-theoretical claims that can be derived from a content analysis of the Qur’an, and to situate those claims within contemporary scholarship that treats religion as a micro and a multi-level social force. In this Discussion, the study’s empirical patterns are integrated with three interlocking arguments: that the Qur’an functions as a dense repository of practice-directing norms which generate micro-level social dispositions; that those dispositions are produced through routinized, oral, and communal practices (habitus) rather than only through abstract doctrine; and that Qur’anic micro-theories must be read as part of multi-level social processes (micro ↔ meso ↔ macro) rather than as isolated individualist models. These arguments form the basis for both theoretical consequences and methodological considerations.

7.1. Qur’an as a Source of Micro-Level Norms

The content analysis reveals that the Qur'anic text is saturated with short, action-oriented imperatives and situational deliberations (commands about generosity, reciprocity, justice, family ties, and ritual practice). These instances are not idle ethical statements but prescriptive directives targeted at everyday behaviours, which makes them fertile ground for micro-theorising social interaction. Unlike grand normative systems oriented primarily to institutions, these verses repeatedly specify interpersonal duties, modes of speech, obligations to kin and neighbours, and discrete economic acts; in short, they map onto the empirical domain of microsociology (interaction, role enactment, and socialisation). This orientation is consistent with recent work emphasising religion’s affordances for micro-level social life (Herzog et al., 2020).

The Qur’an can thus be seen not merely as an abstract theological guide but as a repository of social technologies, outlining procedures for everyday cooperation and conflict resolution. Jaiyeoba, Ushama, and Amuda (2024) stress that Qur’anic injunctions are explicitly designed to regulate daily morality and ethics, confirming our content-analytic findings. The micro-theoretical insight here is that Islam, through the Qur’an, generates norms at the intimate level of family and community life rather than being restricted to macro-level governance alone.

7.2. Oral Transmission, Ritualisation, and Habitus

The production of social dispositions in Qur’anic contexts is mediated by oral-ritual practice and communal repetition rather than by one-time cognitive assent alone. The findings — particularly the high frequency of verses tied to liturgy, recitation, public invocation, and mandated social acts — support the idea that the Qur’an operates as a performative and oral tradition that shapes habitus: embodied dispositions that structure perception and routine conduct.

Dweirj (2023) emphasises that the Qur’an’s oral transmission plays a central role in forming Muslims’ habitus, demonstrating how recitation and embodied ritual embed dispositions into everyday conduct. In this sense, the Qur’an functions as both text and performance, simultaneously prescribing and embodying social practice. This suggests that Qur’anic micro-theories are not simply cognitive statements of belief but lived practices enacted repeatedly across generations.

Furthermore, Ahmad Dahlan, Afifi Hasbunallah, and Ahmad Luthfi Hidayat (2022) illustrate that Qur’anic associations (jamʿiyyah qur’aniyyah) in Indonesia operate as key carriers of this oral-ritual habitus, embedding scriptural practices into community life. Their study aligns with the argument here: micro-level effects arise not simply from verses’ semantic content but from their institutionalised oral enactment.

7.3. Nested and Multi-Level Structures

Qur’anic micro-theories must also be read as part of nested, multi-level causal structures. Micro dispositions (e.g., norms of reciprocity and modest speech) do not float freely; they interact with meso-level institutions (families, mosques, educational associations) and macro-level structures (legal codes, state policies, demographic patterns). Recent multilevel work on religion shows precisely this: religious phenomena exhibit personal (micro) and contextual (macro/meso) effects — for instance, individual religiosity shapes attitudes. However, it is moderated by national or communal religious contexts (Adamczyk, 2022).

This resonates with our findings. Qur’anic micro-level directives take on variable significance depending on the meso-institutional environment. For example, zakat (charitable giving) is more potent in communities with strong institutional frameworks for redistribution. Where such frameworks are absent, the behavioural outcome of the same verses may be muted. Hence, the Qur’an’s micro-theories are best understood as conditionally activated within broader institutional contexts.

7.4. Three Theoretical Contributions

Taken together, the findings offer three main theoretical contributions:

A practice-centred micro-theory of Qur’anic sociality. Qur’anic injunctions should not be reduced to abstract moral rules but modelled as triggers and stabilisers of recurring social practices (rituals, gatherings, patterned speech) that scaffold micro-interactions. The mechanism may be summarised as: text → ritualised practice (recitation/liturgical enactment) → habitus/disposition → patterned micro-interaction. This mechanism highlights how verses with similar semantic content produce different social effects depending on ritualisation (Dweirj, 2023; Ahmad Dahlan et al., 2022).

Context-sensitive expectations about variance. Because the mechanism depends critically on local ritual and institutional carriers, the same Qur’anic prescriptions can produce different micro-social outcomes across communities. This explains empirical heterogeneity in prior studies: some communities display strong behavioural signatures of Qur’anic norms (e.g., cooperation, gendered roles), while others do not — a pattern consistent with multilevel models (Adamczyk, 2022; Herzog et al., 2020).

Norms as social technologies. The Qur’an functions as a compact set of social technologies — short procedural rules that communities use to coordinate action (e.g., zakat as an economic coordination device; reciprocity verses as reputational management tools). Understanding these technologies requires attention to their embeddedness in social practice. This framing invites comparative work across religious texts and social technologies (Herzog et al., 2020; Jaiyeoba et al., 2024).

7.5. Limitations and Methodological Caveats

Several constraints temper these conclusions. First, content frequency is an imperfect proxy for causal strength; a verse’s social impact depends on salience, interpretive prominence, and ritual placement — factors that require ethnographic data to assess. Second, contemporary interpretations and juridical elaborations (tafsir, hadith, legal schools) mediate the translation from text to practice; our analysis is text-centric and cannot fully capture these interpretive layers. Third, cross-cultural variation in linguistic practice and orality means that text analysis must be combined with ethnographic research on recitation and pedagogy to validate the habitus claim. These caveats suggest a mixed-methods program (content analysis + ethnography + multilevel modelling) as the next step (Dweirj, 2023; Ahmad Dahlan et al., 2022).

7.6. Future Research Agenda

To move from descriptive micro-theories to testable social science, three empirical priorities emerge:

Ethnographic tracing of specific verses: How selected verses are taught, recited, and used in community social rituals.

Network and institutional mapping: Documenting the meso-level carriers (mosques, Qur’anic associations, charitable institutions) and measuring their mediating role.

Multilevel testing: Combining individual survey measures of behaviour with community-level indices of Qur’anic institutional density to test conditional predictions.

Such a design would operationalise the practice-centred micro-theory proposed here and allow rigorous causal inference, consistent with recent empirical work on religiosity’s multilevel effects (Adamczyk, 2022; Herzog et al., 2020).

7.7. Concluding Synthesis

As a text embedded in living oral and institutional practices, the Qur'an supplies micro-level hypotheses about how individuals should relate to neighbours, kin, and strangers. However, the potency of those hypotheses depends on ritualisation and institutional transmission. The content analysis reported here accomplishes two things: it identifies the textual resources for micro-theorising and highlights the mediating role of practice and context. Placing the Qur’an back into the social ecology where it is read, recited, and practised transforms static textual readings into dynamic, testable micro-theories of social interaction. This approach aligns with recent practice-theoretical and multilevel scholarship and opens a productive research program at the intersection of religious studies and microsociology.

8. Qur’anic Anticipations of Modern Micro-Theories: A Historical Reconsideration

The findings of this research strongly suggest that the Holy Qur’an contains the conceptual roots of what contemporary sociology classifies as micro-theories. These theories, which primarily emerged between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, emphasise the dynamics of everyday social interaction, meaning-making, reciprocity, and the structuring of intimate relationships. However, the Qur’an — revealed in the seventh century CE — already articulated a comprehensive framework for micro-social life. This chapter juxtaposes Qur’anic directives with the later development of sociological theories, presenting a logical rationale and a timeline of micro-theoretical thought to demonstrate this claim.

8.1. The Qur’an as a Foundational Source of Micro-Social Insight

The Qur’an provides numerous directives that govern small-scale, face-to-face interactions. Verses on truthful speech, mutual consultation (shūrā), equitable exchange, kinship solidarity, neighbourly conduct, and ritual cooperation point directly to the patterns later studied by microsociologists. As Dweirj (2023) shows, the Qur’an is a doctrinal and oral-ritual tradition that forms habitus, embedding micro-level practices into daily life. Similarly, Jaiyeoba, Ushama, and Amuda (2024) emphasise that ethical guidance structures everyday decision-making, from household interactions to economic fairness.

This indicates that what sociologists later theorised as symbolic interaction, role theory, or social exchange was already present in the Qur’anic framework — not in the form of abstract models, but as actionable injunctions, deeply tied to human lived realities.

8.2. Timeline of the Emergence of Sociological Micro-Theories

To establish the Qur’an’s precedence, we must briefly review the historical development of sociological micro-theories:

Seventh Century CE — Qur’anic Revelation

The Qur’an (610–632 CE) articulated interaction norms long before sociology was born. It detailed principles of reciprocity (zakat, sadaqah), role obligations within families, verbal etiquette in conversation, and procedures of conflict mediation — all of which map directly onto microsociological domains.

Fourteenth Century CE — Ibn Khaldūn’s Muqaddimah (1377 CE)

Centuries later, Ibn Khaldūn systematised social thought, describing ʿasabiyyah (group solidarity), education, and social cohesion (Rosenthal, 2015). Though not strictly micro-level, his work demonstrated continuity between Qur’anic insights and early Islamic social theory, showing how kinship and group identity structure interactions.

Nineteenth Century CE — Founding of Sociology

Modern sociology, emerging in the works of Auguste Comte, Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, and Max Weber (Ritzer & Stepnisky, 2017), initially concentrated on macro-level processes such as industrialisation, capitalism, and rationalisation. Micro-level dynamics were acknowledged but not fully theorised.

Early Twentieth Century — Chicago School and Symbolic Interactionism (1900s–1930s)

Symbolic interactionism, spearheaded by George Herbert Mead and Herbert Blumer, emphasised that meanings are created through social interaction (Blumer, 1969). However, centuries before, the Qur’an highlighted speech, mutual recognition, and symbolic acts (e.g., greeting rituals, oaths, shared prayer) as foundational to social life.

Mid-Twentieth Century — Ethnomethodology and Social Exchange (1950s–1970s)

Harold Garfinkel developed ethnomethodology to study everyday conversational practices, while George Homans and Peter Blau advanced social exchange theory, framing human interaction as reciprocal cost-benefit processes (Homans, 1961; Blau, 1964). The Qur’an, however, had already provided normative models of reciprocity, charity, justice, and exchange centuries earlier, embedding these micro-structures into divine command.

Late Twentieth Century — Network Theory and Habitus Approaches (1980s–2000s)

With Pierre Bourdieu's influence, scholars began analysing habitus and symbolic capital at the micro-level. Nevertheless, as Dweirj (2023) notes, the Qur’an’s oral and ritual practice had long produced embodied dispositions, providing a divine articulation of habitus centuries before its secular sociological rediscovery.

8.3. Qur’anic Precedence Over Modern Theories

This timeline demonstrates that the Qur’an anticipated core insights of micro-theories centuries before they were “discovered” by modern sociology:

Symbolic interactionism: Qur’anic injunctions on truthful speech, greetings (salām), and consultation mirror Mead’s later claim that meaning emerges through interaction.

Ethnomethodology: Qur’anic focus on everyday practices, such as maintaining fairness in trade and avoiding gossip, parallels Garfinkel’s insistence on the significance of ordinary conversational rules.

Social exchange theory: The Qur’an repeatedly frames reciprocity, charity, and obligations as guiding principles, long before Homans or Blau theorised interaction in terms of exchange.

Habitus and embodiment: Qur’anic recitation and ritual repetition created embodied dispositions, a principle later formalised by Bourdieu.

Therefore, while modern sociological theory provides secularised frameworks for analysing interaction, the Qur’an remains these insights' original, divinely revealed source.

8.4. Implications for Sociology

Recognising the Qur’an as a primary source of micro-theoretical insight has three significant implications:

Historical correction: The genealogy of sociological ideas must be re-examined to acknowledge religious and non-Western contributions, including the Qur’an and Islamic scholarship.

Epistemic humility: Modern sociology should not treat micro-theories as purely Western inventions but as rediscoveries of insights long embedded in scriptural traditions.

Integration of religious sociology: Contemporary scholarship benefits from integrating Qur’anic perspectives, especially in the sociology of religion, family, and community.

From a historical perspective, micro-theories of sociology are latecomers compared to the Qur’an’s seventh-century articulation of norms governing everyday life. The Qur’an provided a divinely anchored framework for reciprocity, symbolic communication, family relations, and moral order centuries before Mead, Garfinkel, or Homans formalised such ideas into sociological categories. In this sense, the Qur’an is not only a sacred text but also the source of sociological micro-theory, predating and anticipating the later intellectual developments of the modern West.

9. Conclusions

This study has examined the Qur’an as a rich source of sociological insight, specifically concerning micro-theories development in sociology. Through content analysis of key Qur’anic verses, the research has demonstrated that the Qur’an offers a comprehensive framework for understanding individual behaviour, interpersonal interaction, and the normative structures that guide social life. Themes such as justice, cooperation, reciprocity, and accountability emerge as central to the Qur’anic worldview, aligning closely with the analytical concerns of micro-sociological theories developed in modern academia.

Symbolic interactionism finds resonance in the Qur’an’s attention to communication, shared symbols, and the construction of meaning in human interactions. Rational choice theory parallels Qur’anic discussions of intention, accountability, and weighing costs and benefits in moral and social decision-making. Phenomenology and ethnomethodology echo the Qur’anic emphasis on lived experiences, interpretive processes, and the maintenance of social order through everyday practices. These connections suggest that the Qur’an anticipated the key principles underpinning micro-theoretical sociology traditions.

The Qur’an differs from modern sociology in integrating normative and empirical dimensions. While sociologists often study social behaviour in a value-neutral framework, the Qur’an fuses empirical observation with divine injunction, thus creating a dual perspective grounded in human social realities and informed by transcendent moral guidance. This duality offers a unique sociological paradigm that is simultaneously descriptive, prescriptive, empirical, and normative.

The findings challenge the conventional assumption that micro-theories are purely Western academic constructs of the 19th and 20th centuries. Instead, this study contends that the intellectual foundations of such theories existed much earlier, articulated within the Qur’anic discourse revealed in the 7th century. Since the works of Weber, Mead, Garfinkel, and other sociologists were written many centuries after the Qur’an, it is reasonable to conclude that the Qur’an constitutes the earliest source of these insights into micro-sociological relations.

By advancing this argument, the study repositions the Qur’an as more than a religious scripture: it is also a foundational intellectual text that prefigured the categories, concepts, and analyses later elaborated in sociology. This perspective broadens the genealogy of sociological thought and affirms the Qur’an’s enduring relevance to contemporary social science debates. Ultimately, the research demonstrates that the micro-theories of modern sociology are not entirely new but derive their intellectual origin from the Qur’an, thereby confirming its role as the source of these theories.

References

- Abdel Haleem, M. A. S. (2005). The Qur’an (Oxford World’s Classics). Oxford University Press.

- Adamczyk, A. (2022). Religion as a micro and macro property: Investigating the multilevel relationship between religion and abortion attitudes across the globe. European Sociological Review, 38(5), 816–831. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Dahlan, A., Afifi Hasbunallah, A., & Ahmad Luthfi Hidayat, A. L. (2022). A sociological approach to the Quran: Contemporary interactions between society and the Quran (jam'iyyah qur'aniyyah) in Indonesia. In International Conference: Transdisciplinary Paradigm on Islamic Knowledge (KnE Social Sciences), 476–484. [CrossRef]

- Alatas, S. F. (2021). Applying Ibn Khaldun: The recovery of a lost tradition in sociology. Routledge.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. (2004). Interaction ritual chains. Princeton University Press.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press. [CrossRef]

- Dweirj, L. (2023). The Qur’an: An orally transmitted tradition forming Muslims’ habitus. Religions, 14(12), Article 1531. [CrossRef]

- Emerson, M. O., & Hartman, D. (2006). The rise of religious fundamentalism. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 127–144. [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall. [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books. [CrossRef]

- Heise, D. R. (2007). Expressive order: Confirming sentiments in social actions. Springer.

- Herzog, P. S., King, D. P., Khader, R. A., Strohmeier, A., & Williams, A. L. (2020). Studying religiosity and spirituality: A review of macro, micro, and meso-level approaches. Religions, 11(9), Article 437. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behaviour as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606.

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behaviour: Its elementary forms. Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology (W. R. Boyce Gibson, Trans.). Allen & Unwin. [CrossRef]

- Jaiyeoba, H. B., Ushama, T., & Amuda, Y. J. (2024). The Quran is a source of ethical and moral guidance in contemporary society. Al-Irsyad: Journal of Islamic and Contemporary Issues, 9(2), 1331–1345. [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research, 28(4), 587–604.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago Press. [CrossRef]

- Qur’an 2:42, 2:271, 2:177, 2:197, 2:225; 2:261; 2:233, 3:29; 3:190–191, 4:86; 4:135, 4:19, 5:2, 6:152, 7:199, 16:90, 18:49, 20:44, 22:32., 24:27, 30:21, 33:70-71, 41:34–35, 42:38, 42:40, 48:11, 49:11-13, 50:16-18, 55:7–9, 60:8, 64:4, 64:17, 83:1-3.

- Ritzer, G., & Stepnisky, J. (2017). Sociological theory (10th ed.). Sage.

- Rosenthal, F. (2015). The Muqaddimah: An introduction to history (N. J. Dawood, Ed.). Princeton University Press.Rosenthal, F. (2015). The Muqaddimah: An introduction to history (N. J. Dawood, Ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Schutz, A. (1967). The phenomenology of the social world. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University .

- Sahih International. (2010). The Qur’an: English translation. Dar-Abul Qasim. (Original work published 1997).

- Smilde, D., & May, M. (2010). The emerging strong program in the sociology of religion. SSSR Annual Meeting paper.

- Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297. [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. S. (2011). Religion and modern society: Citizenship, secularisation and the state. Cambridge University Press.

- Ritzer, G., & Stepnisky, J. (2018). Sociological theory (10th ed.). SAGE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).