Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Empirical Analysis

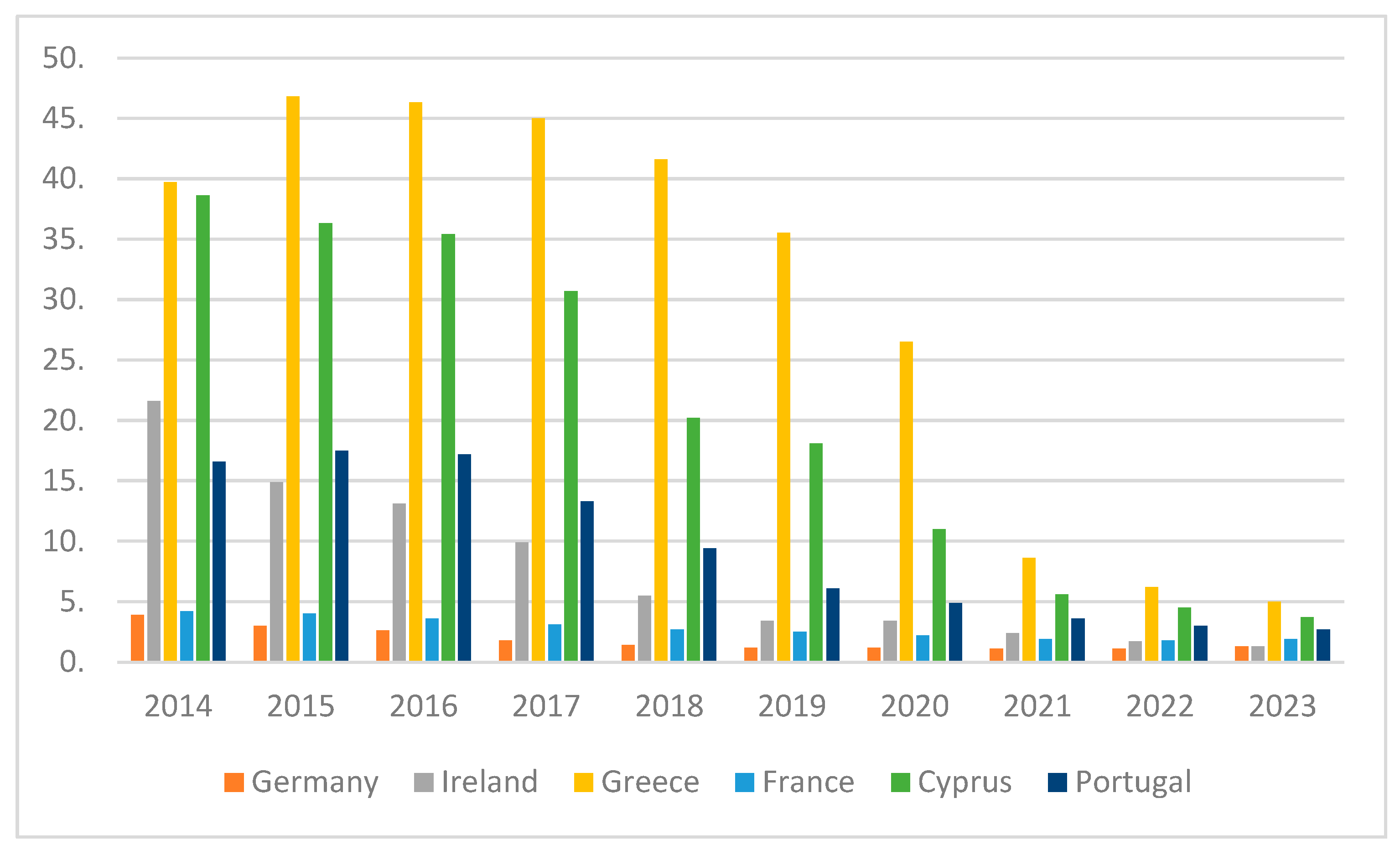

- Non-performing loan (NPL) ratios (2008–2022), transactional data on the sale and management of NPLs portfolios, including the entry and activity of PDIs to consider the impact of the CMU.

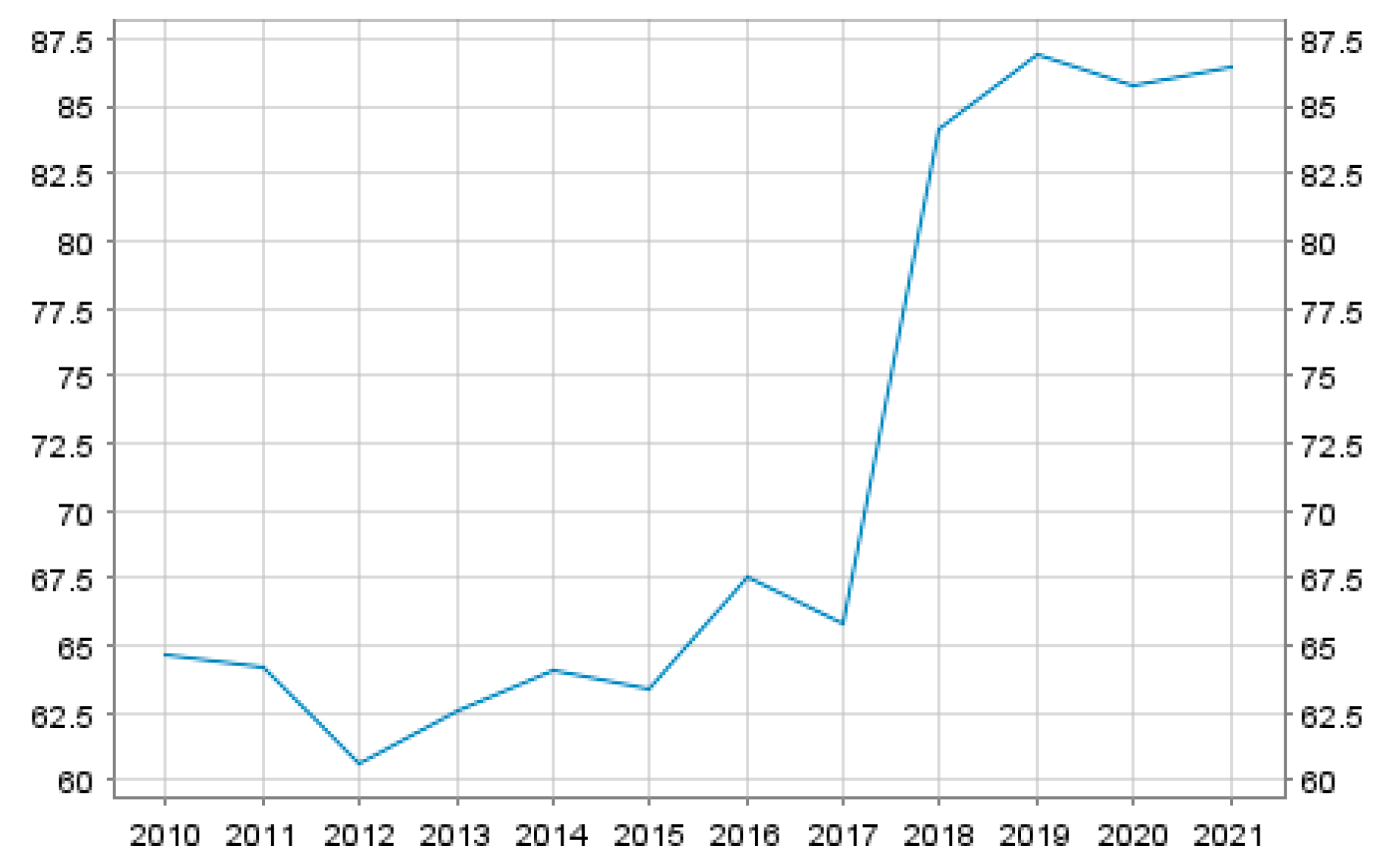

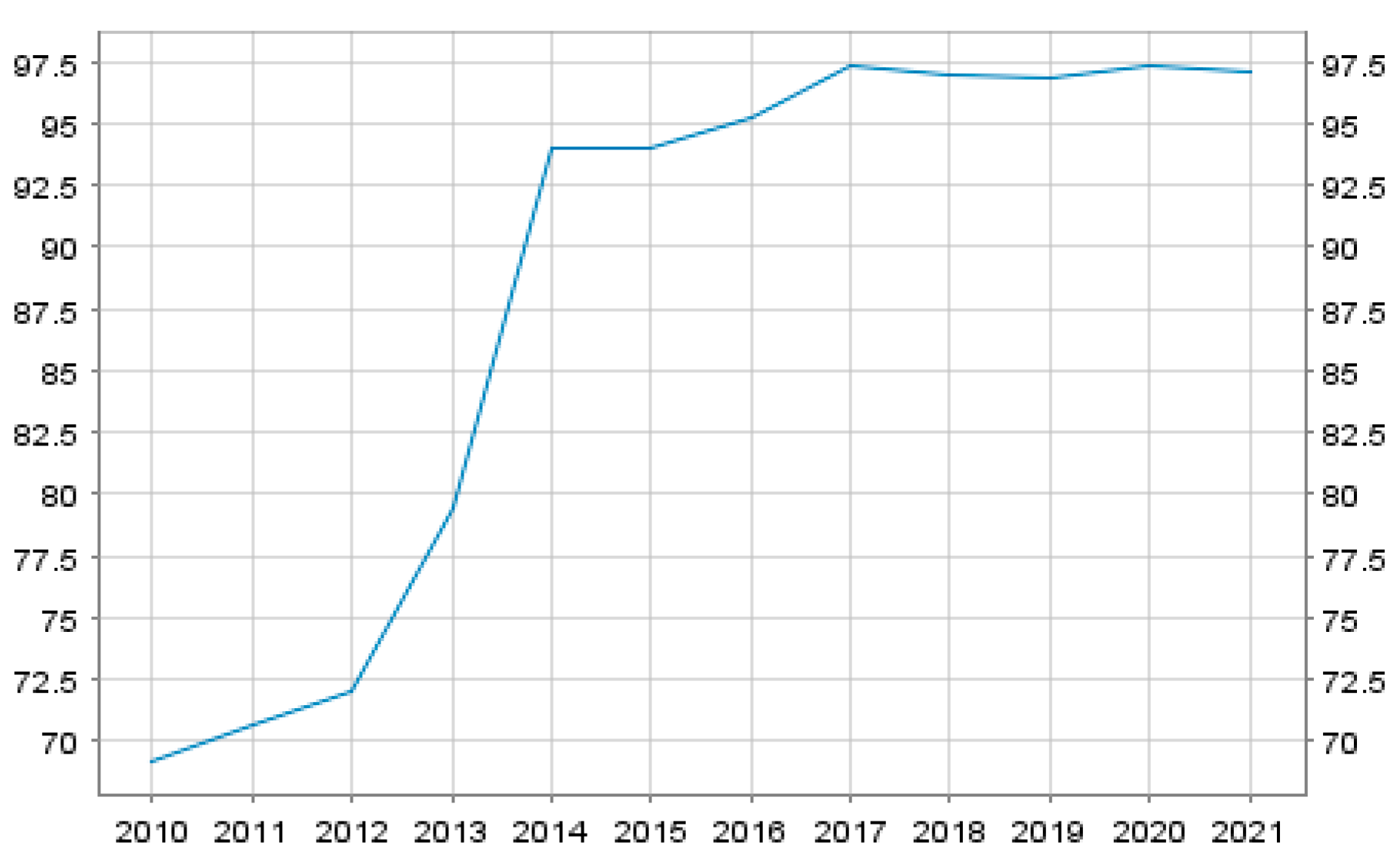

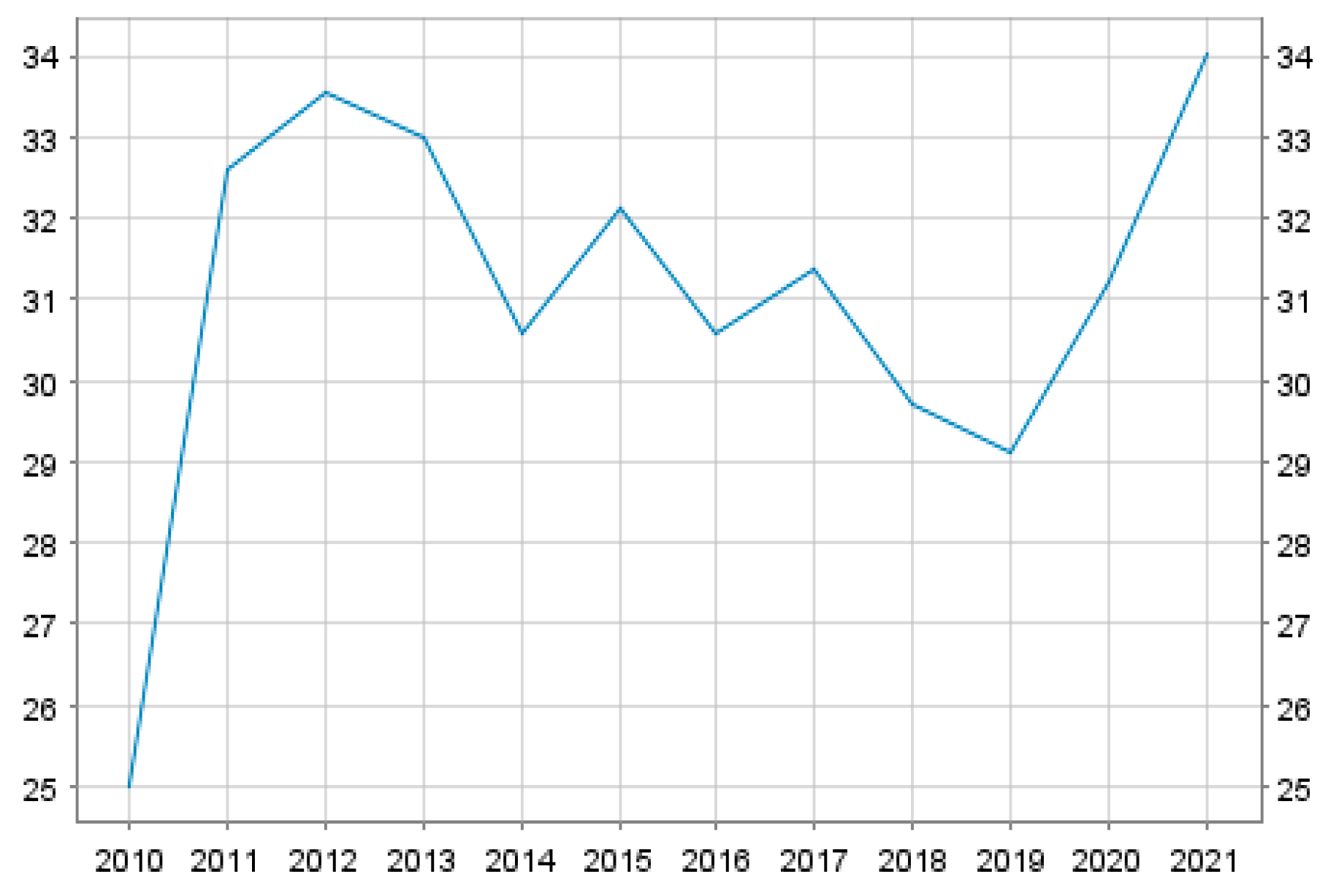

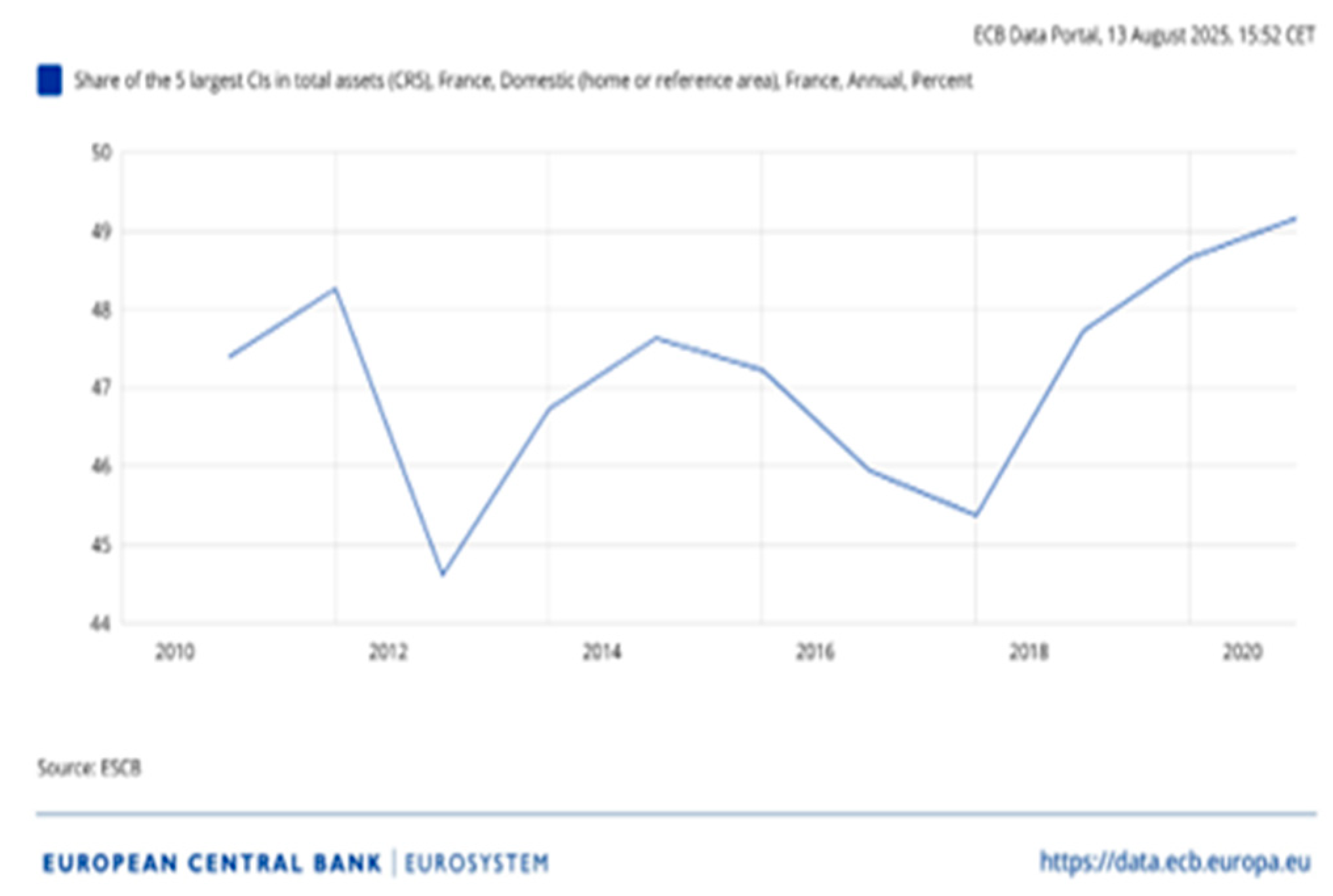

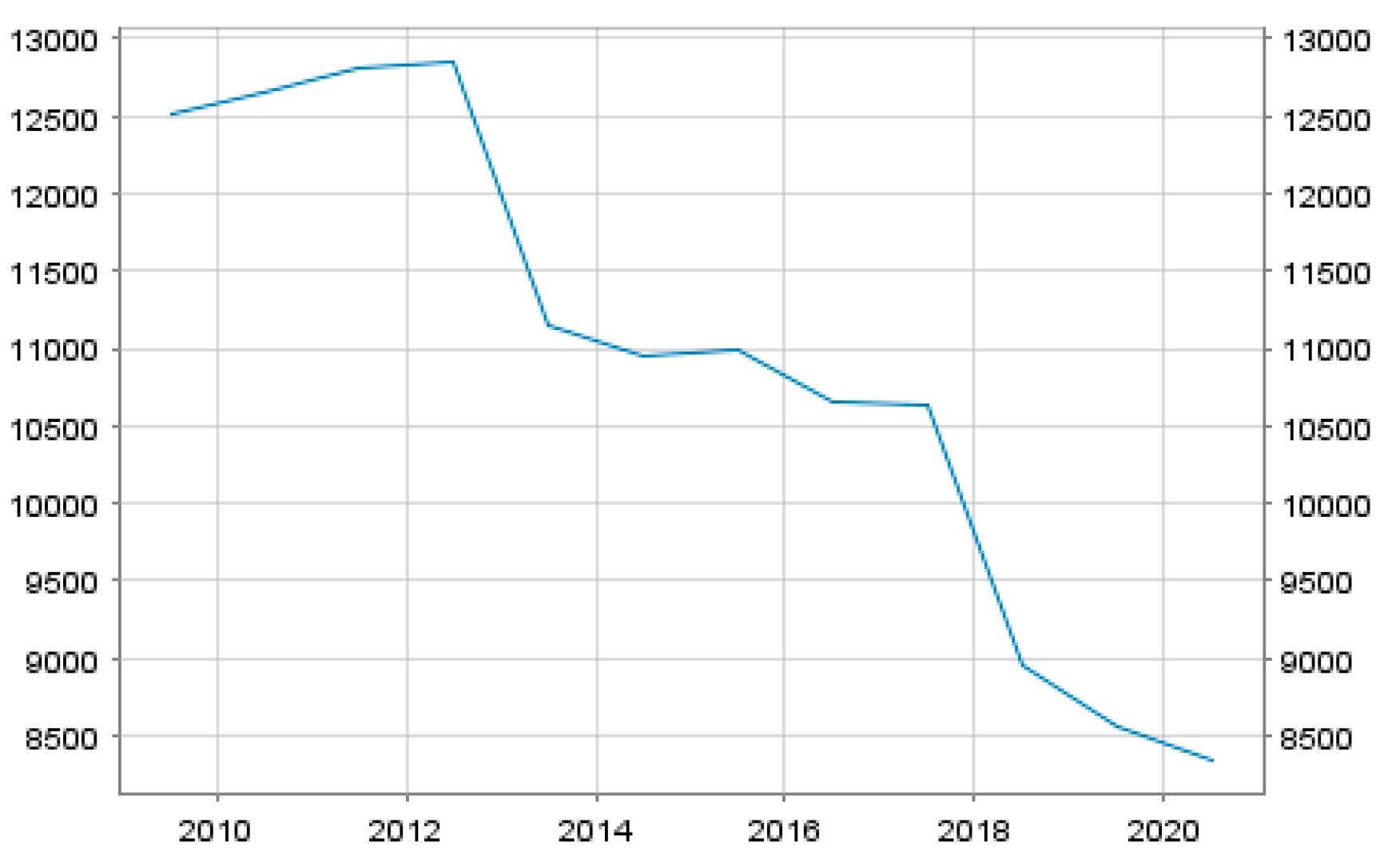

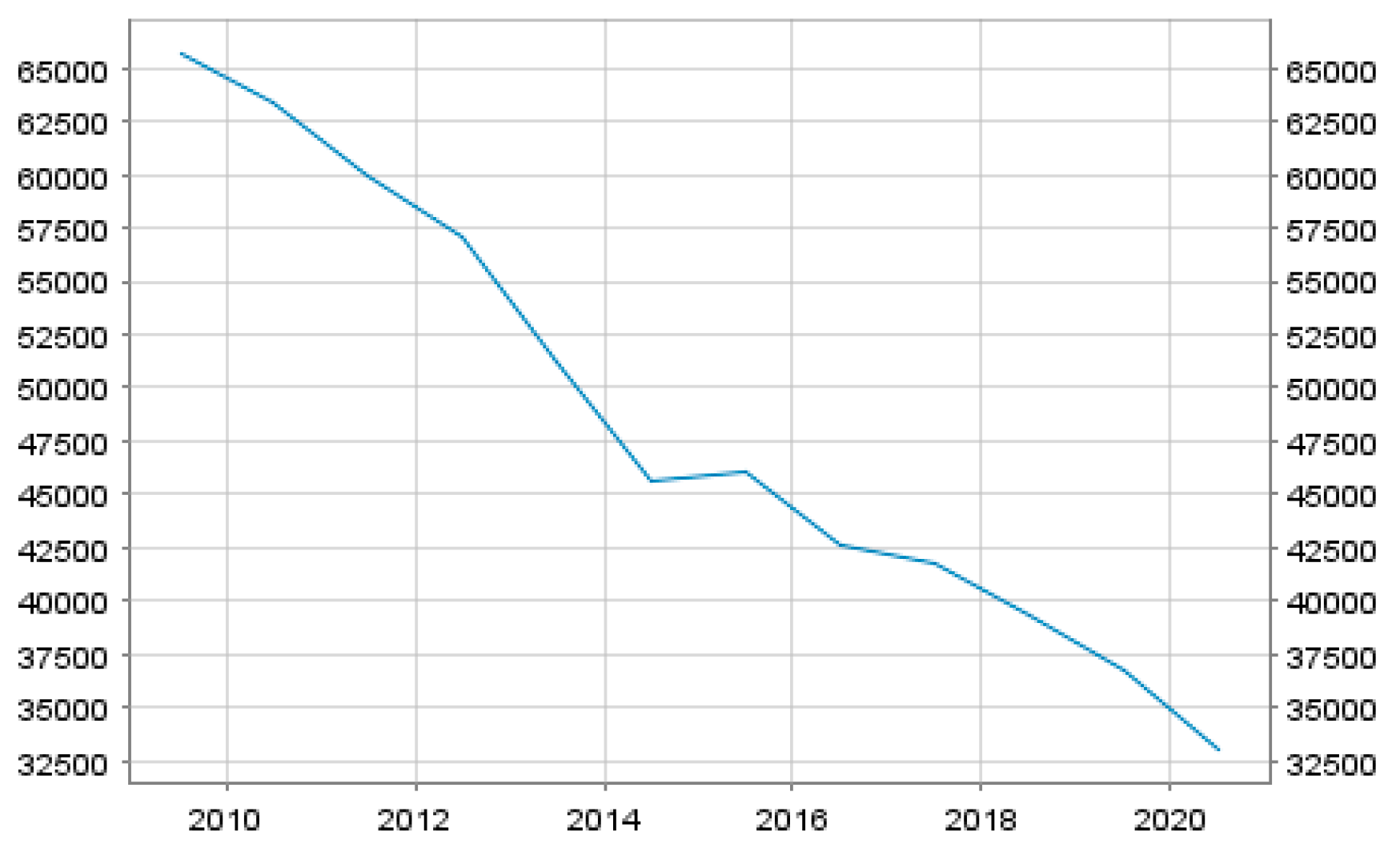

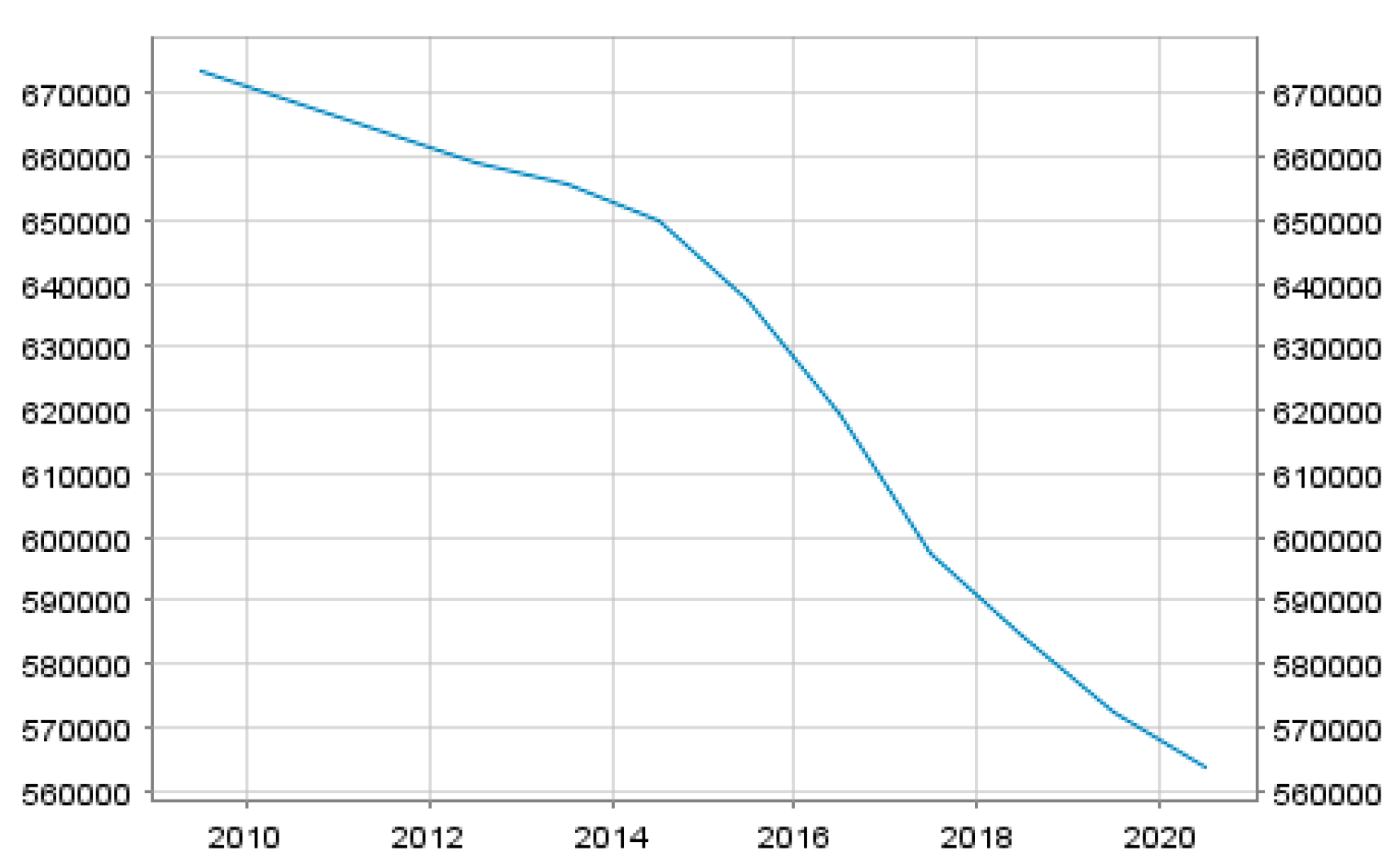

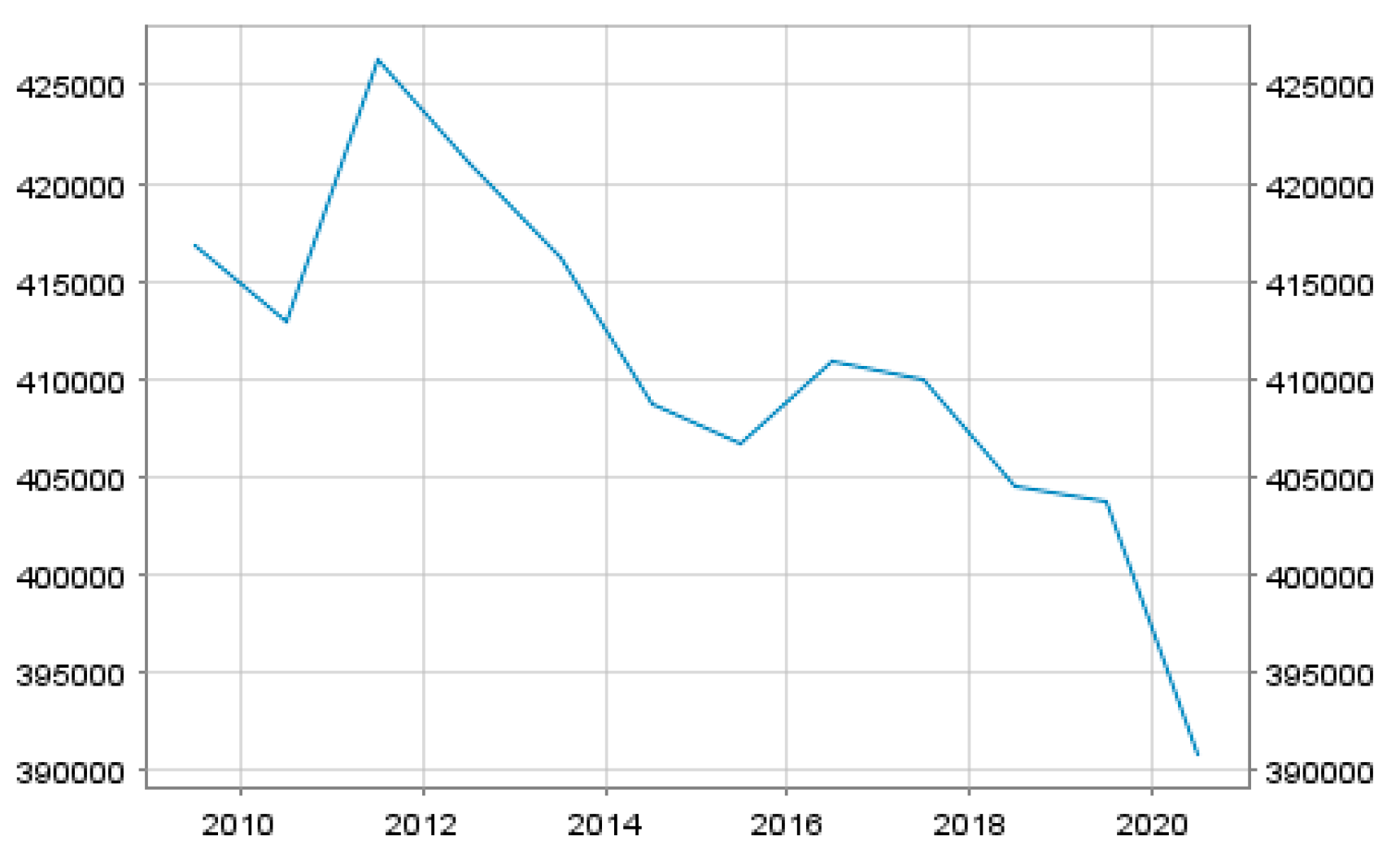

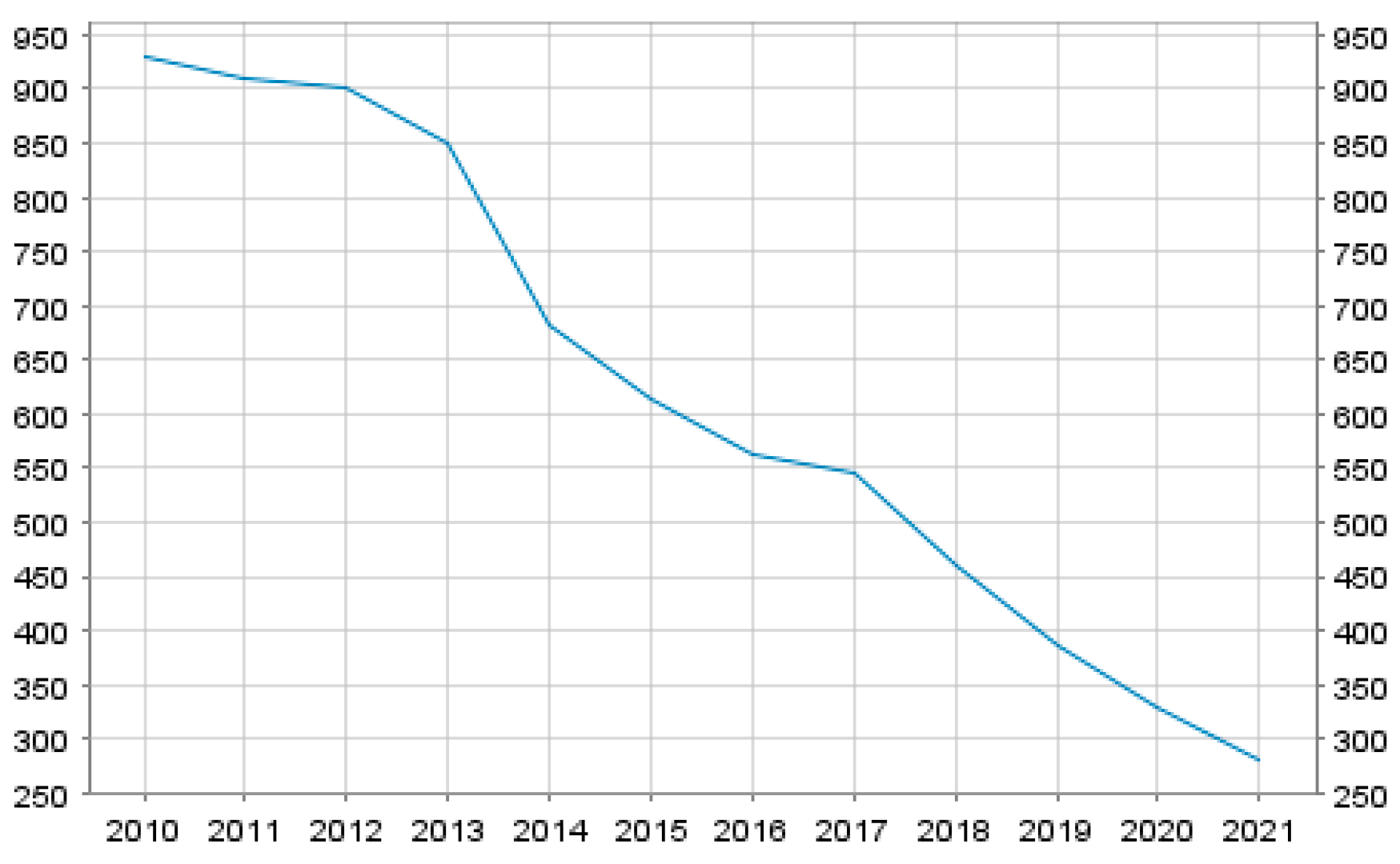

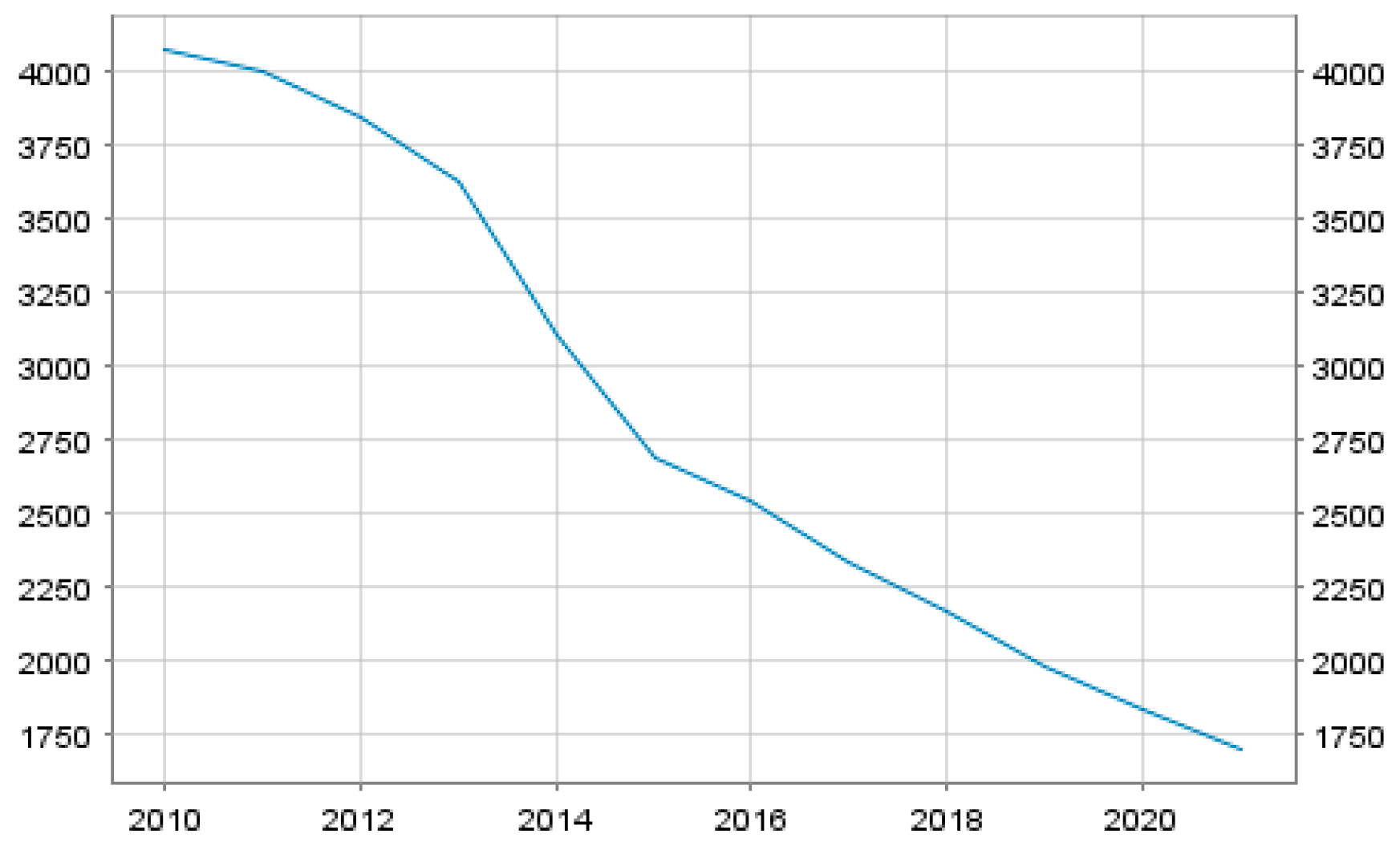

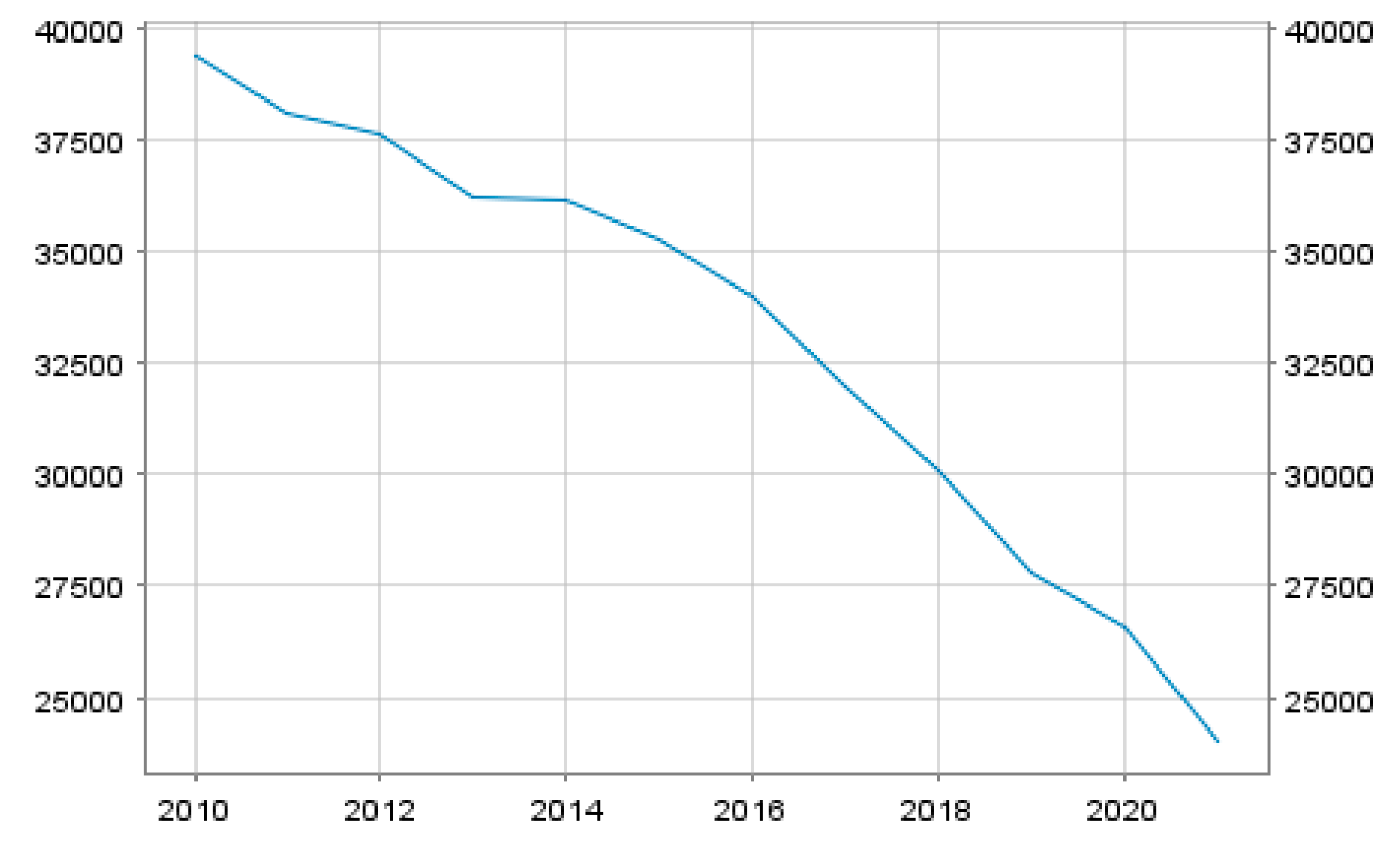

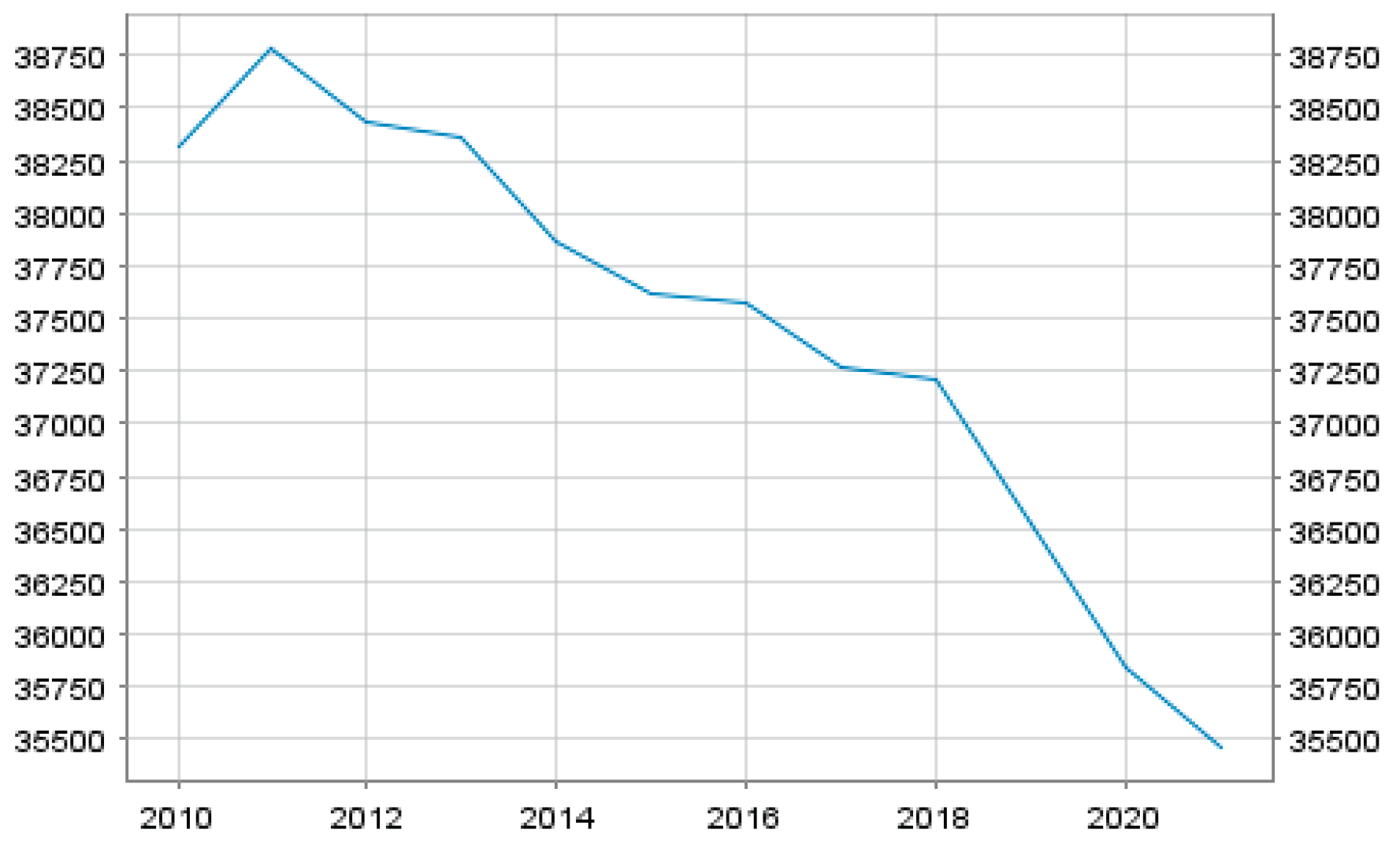

- Market concentration metrics, specifically the share of the five largest credit institutions-CIs in total banking assets (CR5, domestic), sectoral employment and branch data (specifically the number of offices) to evaluate trends in asset consolidation and document the consequences of restructuring and downsizing with a focus on the periphery’s pronounced contraction.

2.2. Qualitative Policy and Institutional Analysis

- EU-level policy frameworks and legal instruments (BU, CMU).

- Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and national legislation underpinning EAPs in Greece and Cyprus, with particular attention to financial structural changes

3. The Capital Markets Union and Private Debt Investors in Cyprus and Greece: Vulture Funds, Financialization, and Systemic Risk

3.1. Non-Banking Financing and Non-Performing Loans in the Capital Markets Union

3.1.1. The Interplay between Private Debt Investors and Credit Institutions in Cyprus and Greece within the Capital Markets Union Framework

| Cyprus | PDI | Credit Institution | Assets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apollo Global Management (AGM) | Bank of Cyprus (2018) | 14,000 loans of €2.8 billion (of which €2.7 billion relate to NPLs) and secured by real estate collateral, to AGM for a gross cash consideration of some €1.4 billion. | |

| Altamira Asset Management (AGM was shareholder) | Cyprus Cooperative Bank prior to the latter’s dissolution and merger to the Hellenic Bank | €7 billion worth NPLs | |

| APS | Hellenic Bank | €2.5 billion share in NPLs | |

| Pepper European Servicing | Bank of Cyprus | €850 million of default collaterals | |

| PIMCO (owned by Allianz SE | Bank of Cyprus | Portfolio of NPLs with a gross book value of €916 mn |

| Greece | PDI | Credit Institution | Assets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apollo Global Management (AGM) | Alpha Bank | non-performing corporate loans with real estate collateral claiming €1 bn and 1,756 mortgages with an estimated value of €543 m | |

| Fortress Investment Group LLC | Consortium of Banks Piraeus, National, Eurobank and Alpha | non-performing loans of a value around €1,8 billion | |

| Fortress Investment Group LLC | Alpha Bank | a pool of Non-Performing Loans to Greek SMEs mainly secured by real estate assets (the “Neptune Portfolio”), of a total on-balance sheet gross book value of Euro 1.1 billion | |

| Bain Capital | Piraeus Bank | € 430 million Amoeba non-performing loan portfolio, with more than 2,000 properties at collateral and face value of €1.95bn. | |

| Centerbridge Partners& Elliott Advisors (UK) Limited | National Bank of Greece | €0.9 billion portfolio of 12,800 NPLs, with 8,300 real estate collateral | |

| PIMCO (owned by Allianz SE | Bank of Cyprus | portfolio of NPLs with a gross book value of €916 mn |

3.2. The Banking Union, Structural Changes in Cyprus and Greece, and the Increasing Concentration of Credit Institution Assets

3.2.1. Findings of Increasing Concentration in the Periphery

3.3. The EAP-Driven Reconfiguration of the Banking Sector in Cyprus

| Date/Period | Event/Action | Key Institutions Involved | Relationship/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (March 25) | Bail-in and Stability Levy imposed | Eurogroup, Cypriot Government, Parliament, All Banks | First-ever bail-in on both resident and non-resident, insured and uninsured depositors; foundational for future EU Banking Union; comprehensive sector overhaul |

| 2013 | New resolution legal framework introduced | All Credit Institutions (CIs) | Provided legal basis for restructuring and downsizing of sector |

| 2013 | Direct intervention in major banks | Bank of Cyprus (BoC), Laiki Popular Bank (LPB) | LPB resolved; “good bank” assets absorbed by BoC; BoC becomes dominant player |

| 2013–2018 | COOP under state/ECB governance; NPL management JV | Cooperative Central Bank (COOP), ECB, Debt Servicers | COOP manages NPLs via joint venture; no Greek bond exposure |

| 2018 (June 15) | Sale of COOP to Hellenic Bank | COOP, Hellenic Bank, KEDIPES | COOP’s assets (except NPLs) transferred to Hellenic Bank; NPLs moved to state-owned KEDIPES |

| 2015 (Q1) | NPLs peak at €15.2bn (63% of gross loans) | All Banks, PDIs | Financial stability pursued through deleveraging; PDIs acquire NPLs at discounts |

| 2015 onwards | New legal framework for foreclosures and insolvency | All Credit Institutions, Legislators | Facilitates NPL resolution, supports sales to private investors |

| 2013–2018 | Forced mergers and consolidation | Major Banks, Regulatory Authorities | Mergers promoted to ensure viability; increased concentration and monopolistic tendencies |

3.3.1. The MoU-Driven Reconfiguration of the Banking Sector in Greece

| Sequence/Stage | Key Event/Policy | Description & Relationships |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-Crisis & Initial Shock | Global Financial Crisis (2008–2009) | Exposed vulnerabilities in Greece; banking sector not original source of instability (EU, 2010: 6) |

| Loss of Market Access | Banks lose wholesale market access by end-2009; deposit outflows; reliance on ECB refinancing (EU, 2010: 23) | |

| 2. First EAP (2010–2012) | Programme Objective | Restore credibility, fiscal sustainability, financial system stability, growth (EU, 2010: 11) |

| ECB Collateral Policy | ECB accepts Greek government debt as collateral, regardless of rating (EU, 2010: 35) | |

| Banking Sector Measures | Liquidity support, recapitalisation (competition-compliant), HFSF established, restructuring plan | |

| Strategic Review | HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Lazard propose mergers, privatisation, liquidation (EU, 2010: 24) | |

| Labour Reform | New law allows banks to negotiate employment directly (EU, 2010: 25) | |

| Forced Restructuring | Viable banks recapitalised; non-viable dissolved (e.g., TT Bank resolved; assets to Postbank/Proton Bank) (EU, 2012: 3–4) | |

| Government Exit | Gradual withdrawal from banking sector | |

| 3. Fiscal/Structural Adjustment & Recession | Austerity & Contraction | Recession “deeper and longer” than projected; credit contracts; NPLs rise (EU, 2011: 1, 76) |

| Sovereign Debt Restructuring | Capital shortfalls; targeted recapitalisation strategy | |

| 4. Second EAP (2012–2015) | Programme Focus | Debt sustainability, competitiveness, fiscal consolidation, privatisation, structural reforms |

| Troika Task Force | Permanent presence in Greece | |

| Constitutional Amendment | Prioritises external debt servicing over social needs | |

| NPLs Escalate | NPLs reach 15.5% by 2011 | |

| Private Sector Involvement (PSI) | 53.5% haircut for bondholders; funds for bank recapitalisation; PSI-II causes further bank losses (€43bn) (EU, 2012: 17–18) | |

| Core Bank Strategy | Core banks recapitalised via HFSF; non-core banks to seek private capital (EU, 2013: 37) | |

| Market Consolidation | Core banks as “integrators”; state banks dissolved/sold; private banks expand (Piraeus acquires BCP Portugal subsidiary); cooperative assets transferred to core banks (EU, 2014: 46, para. 83) | |

| Foreclosure Reform | Law 4224/2013 lifts restrictions to address NPLs (39.9% in 2014) | |

| Return to Bond Market | New 5-year bond issued after four years | |

| MoU (ESM, 2015) | Prioritises NPL resolution, recapitalisation, private management/strategic investment in recapitalised banks (EU, 2015: 18) | |

| NPL Framework | Rapid reform of insolvency laws; “sales markets” for distressed assets (EU, 2015: 8, 18–19); Law 4354/2015 enables non-bank servicers/loan transfers; Government Council for Private Debt Management created | |

| Troika/EU Influence | HFSF leadership panel: 50% appointed by lenders | |

| 5. Supplemental MoUs & Final Developments (2016–2018) | Supplemental MoU (2016) | No unilateral national actions undermining banks; all measures to be coordinated with EC/ECB/IMF/ESM (EU, 2016) |

| NPL Market Finalised | Sale of distressed assets (including primary residences) to Private Debt Investors; NPE ratio at 45% | |

| Out-of-Court Framework | Expedites debt restructuring, minimises creditor losses | |

| Liquidation/E-Auctions | Accelerated liquidation of non-viable businesses; electronic auctions for enforcement | |

| MoU Supplement (2017) | Reduces tax disincentives for loan loss provisioning/write-offs; more staff for household insolvency cases (Law 3869/2010) | |

| Fiscal Surplus & Exit | Primary surplus >4% GDP; Greece exits EAP (Aug 2018); four core banks achieve envisaged positions; secondary NPL market operational; NPL sales completed | |

| 6. Outcome | Consolidation & Recovery | Core banks preserved/consolidated; NPLs transferred to secondary market; reforms embedded in law; economic recovery promoted via resolutions, mergers, recapitalisations |

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGM | Apollo Global Management |

| BRRD | Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive |

| BU | Banking Union |

| CIs | Credit Institutions |

| CMU | Capital Markets Union |

| CRDIV/CRR | Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation |

| DGSs | Deposit Guarantee Schemes |

| EAPs | Economic Adjustment Programmes |

| EMU | Economic Monetary Union |

| ESM | European Stability Mechanism |

| EFSF | European Financial Stability Facility |

| EU | European Union |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| MoUs | Memorandum of Understanding |

| NPLs | non-performing loans |

| PDIs | Private Debt Investors |

| SSM | Single Supervisory Mechanism |

| SRM | Single Resolution Mechanism |

| VFs | Vulture Funds |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Amin, S. (1988). Eurocentrism. London: Zed Press.

- Amin, S. (1996). The challenge of globalization. Review of International Political Economy, 3(2), 216–259. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. (2019). The new imperialist structure. Monthly Review, 71(3). [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N., Fafaliou, I., & Polemis, M. L. (2016). New evidence on assessing the level of competition in the European Union banking sector: A panel data approach. International Business Review, 25(1), 395–407. [CrossRef]

- Apollo Offshore Credit Strategies Fund Ltd. (n.d.). European overview. https://www.apollo.com/site-services/european-overview.

- Apollo takes over Citi’s global real estate funds platform. (2010, November 15). https://realassets.ipe.com/apollo-takes-over-citis-global-real-estate-funds-platform/37924.article.

- AURA Real Estate Experts. (2019, June 6). Greece: doBank buys servicing licence and is renamed to doValue. https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/greece-dobank-buys-servicing-licence-and-is-renamed-to-dovalue/.

- AURA Real Estate Experts. (2019, November 13). Funds flood the market with real estate. https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/funds-flood-the-market-with-real-estate/.

- AURA Real Estate Experts. (2020, January 30). NPL servicers have started the sales of real estate. https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/npl-servicers-have-started-the-sales-of-real-estate/.

- Avlijaš, S., Hassel, A., & Palier, B. (2021). Growth strategies and welfare reforms in Europe. In Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: How have growth regimes evolved (pp. 372-436).

- Baiardi, D., & Morana, C. (2018). Financial development and income distribution inequality in the euro area. Economic Modelling, 70, 40-55. [CrossRef]

- Bank of Cyprus confirms Apollo NPLs sale. (2018, August 31). https://www.news.cyprus-property-buyers.com/2018/08/31/bank-of-cyprus-confirms-apollo-npls-sale/id=00154648.

- Bank of Cyprus Holdings. (2020, August 3). Agreement for sale of a portfolio of non-performing loans. https://www.bankofcyprus.com/globalassets/investor-relations/press-releases/eng/20200803-helix2announcement_eng_final.pdf.

- Bavoso, V. (2019). [Review of the book Capital Markets Union in Europe, by D. Busch, E. Avgouleas, & G. Ferrarini (Eds.)]. Journal of International Banking Law & Regulation, 34(5), 183–185.

- Bayoumi, T., & Eichengreen, B. (1993). One money or many? On analyzing the prospects for monetary unification in various parts of the world.

- Becker, J., Jäger, J., Leubolt, B., & Weissenbacher, R. (2010). Peripheral financialization and vulnerability to crisis: A regulationist perspective. Competition & Change, 14(3–4), 225–247. [CrossRef]

- BloombergQuint. (n.d.). HSBC reaches agreement to sell Greek bank branches to Pancreta. https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/hsbc-reaches-agreement-to-sell-greek-bank-branches-to-pancreta.

- Bryant, C. (2011, September 29). German banks can stomach Greek debt. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/7cbdc3f4-e9f0-11e0-b997-00144feab49a.

- Campos, N. F., & Macchiarelli, C. (2021). The dynamics of core and periphery in the European monetary union: A new approach. Journal of International Money and Finance, 112, 102325. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G. (2020). The 2012 private sector involvement in Greece. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Corporate Finance Institute. (n.d.). What are vulture funds? https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/vulture-funds/.

- Costamagna, F. (2012). Saving Europe under strict conditionality: A threat for EU social dimension? Centro Einaudi – Comparative Politics and Public Philosophy Lab, Working Paper- LPF 7/12.

- Council of the EU. (2016, June 17). Council conclusions on a roadmap to complete the Banking Union (Press Release).

- Council of the EU. (2017, July 11). Council conclusions on action plan to tackle non-performing loans in Europe. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/07/11/conclusions-non-performing-loans/.

- Council of the EU. (2017, July 11). ECOFIN Council in July 2017. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/07/11/conclusions-non-performing-loans/.

- Council of the European Union. (2010, May 9–10). Economic and Financial Affairs: Extraordinary Council meeting (Press Release 9596/10).

- Creel, J., & El Herradi, M. (2024). Income inequality and monetary policy in the euro area. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 29(1), 332-355.

- De Grauwe, P., & Ji, Y. (2020). Structural reforms, animal spirits and monetary policies. European Economic Review, 124, Article 103395. [CrossRef]

- De Rynck, S. (2016). Banking on a union: The politics of changing eurozone banking supervision. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 119-135. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. (2019, October). Deleveraging Europe. Financial Advisory. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/corporate-finance/deloitte-uk-deleveraging-europe-2019.pdf.

- Denk, O., & Cournède, B. (2015). Finance and income inequality in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1224, OECD Publishing.

- Deutschmann, C. (2011). Limits to financialization: Sociological analyses of the financial crisis. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie, 52(3), 347-389.

- Donnelly, S. (2018). Liberal economic nationalism, financial stability, and Commission leniency in Banking Union. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 21(2), 159–173. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, G. A. (Ed.). (2005). Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Epstein, G., & Jayadev, A. (2005). The rise of rentier incomes in OECD countries: Financialization, central bank policy and labor solidarity. In G. Epstein (Ed.), Financialization and the world economy (pp. 46–74). Edward Elgar.

- Epstein, R., & Rhodes, M. (2018). From governance to government: Banking union, capital markets union and the new EU. Competition & Change, 22(2), 205–224. [CrossRef]

- Eurogroup. (2016, May 9). Eurogroup statement on Greece. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/05/09/eg-statement-greece/.

- European Central Bank. (2021). SSI: Banking structural financial indicators. https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/browse.do?node=9689719.

- European Commission. (2012). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: A roadmap towards a banking union (COM/2012/0510 final).

- European Commission. (2015). Commission staff working document: Economic analysis accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union (SWD/2015/0183 final).

- European Commission. (2015, August 11). Memorandum of understanding between the European Commission acting on behalf of the European Stability Mechanism and the Hellenic Republic and the Bank of Greece. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/01_mou_20150811_en1.pdf.

- European Commission. (2015, August 14). Report on Greece’s compliance with the draft MOU commitments and the commitments in the Euro Summit statement of 12 July 2015.

- European Commission. (2016, June 16). Supplemental memorandum of understanding.

- European Commission. (2017). Factsheet: Completing the banking union.

- European Commission. (2017, July 5). Supplemental memorandum of understanding (second addendum to the memorandum of understanding) between the European Commission acting on behalf of the European Stability Mechanism and the Hellenic Republic and the Bank of Greece (p. 26). https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/smou_final_to_esm_2017_07_05.pdf.

- European Commission. (2018, June 20). Supplemental memorandum of understanding: Fourth review of the ESM Programme [Draft].

- European Commission. (n.d.). Supplemental memorandum of understanding: Greece third review of the ESM Programme. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/third_smou_-_final.pdf.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2010). The economic adjustment programme for Greece: First review – summer 2010 (Occasional Papers 68/August 2010).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2010). The economic adjustment programme for Greece: Second review – autumn 2010 (Occasional Papers 72).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2011). The economic adjustment programme for Greece: Third review – winter 2011 (Occasional Papers 77).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2011). The economic adjustment programme for Greece: Fourth review – spring 2011.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2012). Statement by the Eurogroup: 21 February 2012. In The second economic adjustment programme for Greece: March 2012 review. Publications Office. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2012). The second economic adjustment programme for Greece: March 2012 review. Publications Office. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2013). The economic adjustment programme for Cyprus: Memorandum of understanding on specific economic policy conditionality (Occasional Papers 149).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2013). The second economic adjustment programme for Greece: Second review – May 2013 (Occasional Papers 148).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2014). The second economic adjustment programme for Greece: Fourth review – April 2014 (Occasional Papers 192).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2015, December 21). Report on Greece’s compliance with the second set of milestones of December 2015.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2016, June 9). Compliance report: The third economic adjustment programme for Greece: First review June 2016.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2017, June 16). Compliance report: The third economic adjustment programme for Greece: Second review June 2017.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2018, July 9). Compliance report: ESM stability support programme for Greece: Fourth review July 2018.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (n.d.). European economy occasional papers No. 61.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (n.d.). The second economic adjustment programme for Greece – Fourth review presentation.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union. (2017). Communication from the Commission: Completing the banking union.

- European Court of Auditors. (2019). Control of State aid to banks. Audit preview Information on an upcoming audit.

- European Stability Mechanism. (2017). Evaluation of EFSF and ESM financial assistance.

- European Stability Mechanism. (2018, September 14). Staff statement following the first post-programme mission to Greece.

- Financial Stability Board. (2021).

- Furceri, D., Loungani, P., & Zdzienicka, A. (2018). The effects of monetary policy shocks on inequality. Journal of International Money and Finance, 85, 168–186.

- Gianviti, F., Krueger, A. O., Pisani-Ferry, J., Sapir, A., & von Hagen, J. (2010). A European mechanism for sovereign debt crisis resolution: A proposal. Bruegel Blueprint Series.

- George, S. (1990). Disarming debt: We could—but will we? Food Policy, 15(4), 328-335.

- Gouliamos, K. (2014). Το τερατώδες είδωλο της Ευρώπης. Σύγχρονοι Oρίζοντες.

- Gräbner, C., Heimberger, P., Kapeller, J., & Schütz, B. (2020). Is the Eurozone disintegrating? Macroeconomic divergence, structural polarisation, trade and fragility. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 44(3), 647-669.

- Greece. (2010, August 6). Updated memorandum of understanding on specific economic policy conditionality.

- Hardouvelis, G. A., & Gkionis, I. (2016). A decade long economic crisis: Cyprus versus Greece. Cyprus Economic Policy Review, 10, 3–40.

- Harvey, D. (2011). The enigma of capital and the crisis this time. In Business as Usual (pp. 89–112). New York University Press.

- Höpner, M., & Lutter, M. (2018). The diversity of wage regimes: Why the Eurozone is too heterogeneous for the Euro. European Political Science Review, 10(1), 71-96.

- Howarth, D., & Schild, J. (2018). Special edition on reforming Banking Union: Introduction. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 21, 175-177. [CrossRef]

- In Business News. (2017, November 24). Τα διοικητικά στελέχη της Altamira Asset Management (Cyprus). https://inbusinessnews.reporter.com.cy/business/economics/article/174264/ta-dioikitika-stelechi-tis-altamira-asset-management-cyprus.

- International Monetary Fund. (2013, May 15). Press release No. 13/175: IMF Executive Board approves €1 billion arrangement under extended fund facility for Cyprus. IMF Country Report No. 13/125.

- Johnston, A. (2021). Always a winning strategy? Wage moderation’s conditional impact on growth outcomes. In Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: How have growth regimes evolved (pp. 291-319).

- Johnston, A., & Regan, A. (2016). European monetary integration and the incompatibility of national varieties of capitalism. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(2), 318-336.

- Johnston, A., & Regan, A. (2021). Introduction: Is the European Union capable of integrating diverse models of capitalism? In Is the European Union Capable of Integrating Diverse Models of Capitalism? (pp. 1-15). Routledge.

- Kaltenbrunner, A., Lindo, D., Painceira, J. P., & Stenfors, A. (2010). The euro funding gap and its consequences. Central Banking, 11(2), 86-91.

- Laffan, B. (2016). Core-periphery dynamics in the Euro area: From conflict to cleavage? In J. M. Magone, B. Laffan, & C. Schweiger (Eds.), Power and conflict in a dualist economy. London: Routledge.

- Lapavitsas, C. (2009). Financialised capitalism: Crisis and financial expropriation. Historical Materialism, 17, 114–148. [CrossRef]

- Lapavitsas, C. (2012). Crisis in the Eurozone. Verso.

- Lapavitsas, C. (2019). Political economy of the Greek crisis. Review of Radical Political Economics, 51(1), 31–51. [CrossRef]

- Lapavitsas, C., Mariolis, T., & Gavrielides, C. (2018). Economic policy for the recovery of Greece. (E. Screpanti, Preface). Livanis. [In Greek].

- Loorbach, D., Schoenmaker, D., & Schramade, W. (2020). Finance in transition: Principles for a positive finance future. Rotterdam: Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

- Martino, E. D., & Perini, A. (2025). Rescued banks back to the market? The theory, practices and future perspectives of the EU precautionary recapitalization. European Company and Financial Law Review, 22(2), 267-308.

- Miró, J., Kyriazi, A., Natili, M., & Ronchi, S. (2023). Buffering national welfare states in hard times: The politics of EU capacity-building in the social policy domain. Social Policy & Administration. [CrossRef]

- Momirović, D., Janković, M., & Ranđelović, M. (2017). EU-Banking Union – Expectations, deficiencies, and criticisms. In S. S. (Ed.), Advances in Finance, Accounting, and Economics (Vol. 18). [CrossRef]

- Moody’s. (2020, August 6). Bank of Cyprus toxic debt sale to PIMCO is credit positive. https://www.financialmirror.com/2020/08/06/moodys-bank-of-cyprus-toxic-debt-sale-to-pimco-is-credit-positive/.

- Orphanides, A. (2014). What happened in Cyprus? The economic consequences of the last communist government in Europe (IMFS Working Paper Series No. 79). Goethe University Frankfurt, Institute for Monetary and Financial Stability.

- Parker, O., & Tsarouhas, D. (2018). Causes and consequences of crisis in the Eurozone periphery. In O. Parker & D. Tsarouhas (Eds.), Crisis in the Eurozone periphery: The political economies of Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal (pp. 1–27). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pepper completes Bank of Cyprus servicing contract. (2020, September 2). Mortgage Finance Gazette. https://www.mortgagefinancegazette.com/market-news/arrears/pepper-completes-bank-cyprus-servicing-contract-02-09-2020/.

- Petras, J., & Veltmeyer, H. (2007). Multinationals on trial. Ashgate.

- Prebisch, R. [1949a] (1991j). Teoria Dinámica de la Economia (I,II,III,IV,V,VI,VII,VIII). In R. Prebisch, Obras 1919–1949. Tomo IV: 1944–1949. Cursos universitarios e indagatorias teóricas (II) (pp. 410–489). Buenos Aires, Fundación Raúl Prebisch.

- Private Debt Investor. (2018, September). The NPL deal that could unlock the Cyprus market. https://www.privatedebtinvestor.com/npl-deal-unlock-cyprus-market/.

- Quaglia, L. (2019). The politics of an ‘incomplete’ Banking Union and its ‘asymmetric’ effects. Journal of European Integration, 41(8), 955–969. [CrossRef]

- Rama, J., & Hall, J. (2021). Raúl Prebisch and the evolving uses of ‘centre-periphery’ in economic analysis. Review of Evolutionary Political Economy, 2(2), 315-332. [CrossRef]

- Rathgeb, P., & Tassinari, A. (2022). How the Eurozone disempowers trade unions: The political economy of competitive internal devaluation. Socio-Economic Review, 20(1), 323-350. [CrossRef]

- Saigol, L., & Bucak, S. (2020, April 17). Vulture funds prepare to swoop in and feast on troubled company debt. MarketWatch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/vulture-funds-prepare-to-swoop-in-and-feast-on-troubled-company-debt-2020-04-15.

- Sassen, S. (2017). Predatory formations dressed in Wall Street suits and algorithmic math. Science, Technology and Society, 22(1), 6–20. [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. (2018). Is high-finance an extractive sector? Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 25(2), 583-593. [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F. W. (2021). Forced structural convergence in the Eurozone. In A. Hassel & B. Palier (Eds.), Growth and welfare in advanced capitalist economies: How have growth regimes evolved? (pp. 161–200). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Schulten, T., & Müller, T. (2012). A new European interventionism? The impact of the new European economic governance on wages and collective bargaining. Social Developments in the European Union, 181-213.

- Schwartz, M. (2014). A memorandum of misunderstanding - The doomed road of the European Stability Mechanism and a possible way out: Enhanced cooperation. Common Market Law Review, 51, 389-397. [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. M. (2019). Vultures, debt and desire: The vulture metaphor and Argentina’s sovereign debt crisis. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12(5), 382–400. [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D., & Peek, T. (2014). The state of the banking sector in Europe (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1102). OECD Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, E. (2013). Financialization, income distribution and the crisis. In Financial crisis, labour markets and institutions (pp. 116–138). Routledge.

- Taylor, E. (2010, July 27). Deutsche discloses higher exposure to Greece and Spain. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-deutschebank-sovereign-idUKTRE66Q1XR20100727.

- Toussaint, E., & Millet, D. (2010). Debt, the IMF, and the World Bank: Sixty questions, sixty answers. NYU Press.

- van der Zwan, N. (2014). Making sense of financialization. Socio-Economic Review, 12, 99–129. [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, I., Collins, R., Mann, M., Derluguian, G., & Calhoun, C. (2013). Does capitalism have a future? Oxford University Press.

- Weissenbacher, R. (2019). Persistent core–periphery divide in the EU. In The core-periphery divide in the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H. (2022, March 14). HSBC reaches agreement to sell Greek bank branches to Pancreta. SA. https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/hsbc-reaches-agreement-to-sell-greek-bank-branches-to-pancreta.

- Wood, E. M. (2003). Empire of capital. London: Verso.

- Wozny, L. (2017). National anti-vulture funds legislation: Belgium’s turn. Columbia Business Law Review, 697.

- Zeitlin, J., & Vanhercke, B. (2014). Socializing the European Semester? Economic governance and social policy coordination in Europe 2020. SIEPS Report 2014:7. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, December.

- Zeitlin, J., & Vanhercke, B. (2018). Socializing the European Semester: EU social and economic policy co-ordination in crisis and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 149-174. [CrossRef]

- Zenios, S. A. (2013). The Cyprus debt: Perfect crisis and a way forward. SSRN Journal.

| 1 | Although Spain did take structural measures, these were in the framework of country-specific recommendations under the European semester and not in the form of specific MoU conditionalities as in the case of Cyprus, Greece, Ireland and Portugal. See MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING ON FINANCIAL-SECTOR POLICY CONDITIONALITY. SPAIN MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING ON FINANCIAL-SECTOR POLICY CONDITIONALITY 20 JULY 2012 pp. 54-63 in European Union (2012). The Financial Sector Adjustment Programme for Spain. EUROPEAN ECONOMY. Occasional Papers 118 https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2012/pdf/ocp118_en.pdf

|

| 2 | Weissenbacher (2019) also shows that “the dependency paradigm has never completely disappeared from the critical political economy in Vienna.: |

| 3 | A loan, other than held for trading, is considered as non-performing if it satisfies either or both of the following criteria: (a) It is a material loan which is more than 90 days past-due; (b) The debtor is assessed as unlikely to pay its credit obligations in full without realisation of collateral, regardless of the existence of any past-due amount or of the number of days past-due. Source European Central Bank |

| 4 | |

| 5 | European Stability Mechanism-Conditionality Dashboard https://www.esm.europa.eu/financial-assistance/programme-database/conditionality

|

| 6 | For an excellent exploration and presentation of the metaphor of vulture funds see Sonya Marie Scott (2019) Vultures, debt and desire: the vulture metaphor and Argentina’s sovereign debt crisis, Journal of Cultural Economy, 12:5, 382-400, DOI: 10.1080/17530350.2019.1613254. She traces the metaphorical connection between ‘vultures’ and the extraction of debt back to Elizabethan England, to Shakespeare’s poem Venus and Adonis (1593) while in the same period English law’s earliest cases of the predatory purchasing of land titles in order to dispossess the poor, is observed. As the author suggests contemporary cases involving states “defending against vulture funds have cited case law in the Elizabethan context in order to invoke a moral claim against speculation in distressed sovereign debt. The moral charge of the vulture metaphor – laden with connotations of greed, desire and manipulation – contrasts with legal arguments about repayment based on the rationality of contract law which demands repayment of debt and presumes equality of party.” |

| 7 | Vulture creditors may even prevent a settlement or a restructuring of the debt that is in the collective interest of the creditors (for example mainstream creditors include banks) in order to maximise their joint payoff (see Gianviti, F., A. Krueger, J. Pisani-Ferry, A. Sapir and J. von Hagen (2010), “A European mechanism for sovereign debt crisis resolution: A proposal”, Bruegel Blueprint Series Vol. 10) . This type of predatory funds pursue legal action and pose obstacles to restructuring and legal battles under Anglosaxon law may result against the debtor country which often pays the triple price to redeem the vulture (see the case of Elliot against Peru in 1996). |

| 8 | What are Vulture Funds? https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/trading-investing/vulture-funds/

|

| 9 | Vulture funds prepare to swoop in and feast on troubled company debt. Published: April 17, 2020 at 4:46 a.m. ET By Lina Saigol and Selin Bucak https://www.marketwatch.com/story/vulture-funds-prepare-to-swoop-in-and-feast-on-troubled-company-debt-2020-04-15

|

| 10 | |

| 11 | The European Commission denotes NPLs as “bank loans that are subject to late repayment or are unlikely to be repaid by the borrower” . https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/financial-supervision-and-risk-management/managing-risks-banks-and-financial-institutions/non-performing-loans-npls_en

|

| 12 | The term "borrower" is here used for the counterpart that demands funding independent on whether funding is requested in the form of debt or equity. |

| 13 | To the extent that these monopolies operate in the peripheries of the globalized system, this monopoly rent becomes an imperialist rent Amin, S. (2019). The New Imperialist Structure. Montly Review Volume 71, Issue 03 (July-August 2019) |

| 14 | Apollo Offshore Credit Strategies Fund Ltd . (“Fund”), is “a Cayman Islands exempted company, is an open-ended, actively managed long/short credit fund focusing on event-driven and value-oriented investments. Information on the Fund’s investment strategy can be found in the Private Placement Memorandum (“PPM”) Utilizing an opportunistic mandate, the Fund aims to take advantage of long and short catalyst-driven opportunities across market cycles. https://www.apollo.com/site-services/european-overview

|

| 15 | Alpha, is a measure of the difference between a fund’s actual returns and its expected performance given its level of risk. Funds that generate positive alpha provide financial advisors and their clients’ superior returns at the same level of risk as the benchmark, which is often what advisors use for their passive investment approach. https://multi-funds.com/portfolio-posts/alphacentric-funds/

|

| 16 | Bank of Cyprus confirms Apollo NPLs sale. August 31, 2018. https://www.news.cyprus-property-buyers.com/2018/08/31/bank-of-cyprus-confirms-apollo-npls-sale/id=00154648

|

| 17 | The NPL deal that could unlock the Cyprus market. Private Debt Investor. September 2018. https://www.privatedebtinvestor.com/npl-deal-unlock-cyprus-market/

|

| 18 | |

| 19 | Τα διοικητικά στελέχη της Altamira Asset Management (Cyprus). In Business News, 24/11/2017 07:13. https://inbusinessnews.reporter.com.cy/business/economics/article/174264/ta-dioikitika-stelechi-tis-altamira-asset-management-cyprus

|

| 20 | Pepper completes Bank of Cyprus servicing contract. Mortgage Finance Gazette. 2nd September 2020. https://www.mortgagefinancegazette.com/market-news/arrears/pepper-completes-bank-cyprus-servicing-contract-02-09-2020/

|

| 21 | MOODYS: Bank of Cyprus toxic debt sale to PIMCO is credit positive. 6th August 2020. https://www.financialmirror.com/2020/08/06/moodys-bank-of-cyprus-toxic-debt-sale-to-pimco-is-credit-positive/

|

| 22 | Bank of Cyprus Holdings. Agreement for sale of a portfolio of non-performing loans. Nicosia, 3 August 2020. https://www.bankofcyprus.com/globalassets/investor-relations/press-releases/eng/20200803-helix2announcement_eng_final.pdf

|

| 23 | Alpha Bank announces that it has entered into a binding agreement for the disposal of a mixed pool of Non-Performing Loans to Greek SMEs secured by real estate assets (Neptune Portfolio) Athens, 1 July 2020 https://www.alpha.gr/-/media/alphagr/files/group/press-releases/2020/20200701b_deltio_typou_en.pdf

|

| 24 | Greece: doBank buys servicing licence and is renamed to doValue. AURA REAL ESTATE EXPERTS. 6/6/2019 https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/greece-dobank-buys-servicing-licence-and-is-renamed-to-dovalue/

|

| 25 | 637 residential properties, 288 commercial properties, such as offices, shops and warehouses, as well as 89 hotels, which were loan collateral of about 300 borrowers – entrepreneurs. |

| 26 | NPL Servicers have started the sales of Real Estate. AURA REAL ESTATE EXPERTS/ 30/1/2020 https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/npl-servicers-have-started-the-sales-of-real-estate/

|

| 27 | Funds flood the market with real estate. AURA REAL ESTATE EXPERTS. 13/11/2019 https://www.auraree.com/greece/real-estate-news/funds-flood-the-market-with-real-estate/

|

| 28 | COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL A Roadmap towards a Banking Union /* COM/2012/0510 final */ https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0510&from=EN

|

| 29 | Council of the EU Press release 17 June 2016 16:30 Council Conclusions on a roadmap to complete the Banking Union, par.1,2 |

| 30 | Ibid. par.2 |

| 31 | European Commission (2017) Factsheet: Completing the banking union file:///F:/PhD/New%20folder/BANKING%20UNION/171011-banking-union-factsheet_en.pdf |

| 32 | DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FISMA Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union. Communication from the Commission: Completing the banking union (2017). p.3: “Together with the Capital Markets Union (CMU), a complete Banking Union will promote a stable and integrated financial system in the European Union. It will increase the resilience of the Economic and Monetary Union towards adverse shocks by substantially facilitating private risk-sharing across borders, while at the same time reducing the need for public risk-sharing”. |

| 33 | All data on the Share of the 5 largest CIs in total assets (CR5) were last updated: 12 June 2025 14:05 CEST Series key: SSI.A.DE.122C.S10.X.U6.Z0Z.Z |

| 34 | Data on the Number of employees were last updated: 12 June 2025 14:05 CEST Series key: SSI.A.DE.122C.N30.1.U6.Z0Z.Z |

| 35 | Data on Number of offices were last updated: 12 June 2025 16:13 CEST Series key: SSI.A.CY.122C.N40.1.A1.Z0Z.Z |

| 36 | Memorandum of Understanding on Specific Economic Policy Conditionality “to restore the soundness of the Cypriot banking sector and rebuild depositors' and market confidence by thoroughly restructuring and downsizing financial institutions, strengthening supervision and addressing expected capital shortfalls, in line with the political agreement of the Eurogroup of 25 March 2013;”p.66 in European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2013) The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus EUROPEAN ECONOMY Occasional Papers 149 |

| 37 | The haircut, or bail in, or one-off levy for uninsured depositors included “… some EUR 1.4 billion of subordinated debt. All insured deposits at Cyprus Popular Bank, together with Cypriot and UK assets were moved to the Bank of Cyprus. Uninsured deposits, together with the remaining assets and the foreign subsidiaries remained in the legacy part of Cyprus Popular Bank, which is to be liquidated over time. Simultaneously, uninsured deposits at the Bank of Cyprus were subject to an immediate bail-in of 37.5%, implying a deposit-to-share swap. Another 22.5% of the uninsured deposits were frozen with the view to ensuring that all capital needs of the institution will be entirely covered by the own contributions of large depositors. Should the bank turn out to be over-capitalized, i.e. have its Core Tier 1 over 9%, due to this measure, the excess will be unfrozen and returned to the depositors. The resolution of Cyprus Popular Bank and the consolidation of Bank of Cyprus as the leading Cypriot bank resulted in a further immediate deleveraging of the sector by some 80% of GDP (Graph 23b). The capital needs of Cyprus Popular Bank and of Bank of Cyprus, which together totaled about EUR 10 billion (over 50% of Cypriot GDP), have been covered, exclusively through the contributions of uninsured depositors with full contribution of equity shareholders and bond holders”. |

| 38 | European Union European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2010). The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece First review – summer 2010 Occasional Papers 68/August 2010 |

| 39 | This was an institutional framework to deal with the recapitalisation and restructuring of financial institutions. |

| 40 | Ibid “Markets are overestimating the risk of default /debt restructuring and are underestimating the costs…Not only would debt restructuring come at very high costs for Greece, also other euro-area countries would suffer high costs. EU commercial banks’ exposure to Greece amounts to EUR 120 billion, including both claims on the public and the private sector”. P.17 |

| 41 | GREECE Updated Memorandum of Understanding on Specific Economic Policy Conditionality August 6, 2010, p.92 |

| 42 | German banking exposure to Greece was immense. Included bank ownership (i.e. Postbank owned then by Deutsche Bank) and according to FT some “€10bn of Germany’s roughly €18bn exposure to Greece is held by two state-backed “bad bank” agencies set up during the crisis to deal with legacy assets belonging to troubled lenders Hypo Real Estate and WestLB”. Therefore, the extent to which Deutsche Bank could conduct an unbiased study of the Greek Banking System at that moment was questionable. See “German banks can stomach Greek debt” Chris Bryant in Frankfurt SEPTEMBER 29 2011 https://www.ft.com/content/7cbdc3f4-e9f0-11e0-b997-00144feab49a The Deutsche Bank had 1.1bn exposure to Greek sovereign Deutsche discloses higher exposure to Greece and Spain Edward Taylor JULY 27, 201012:03 PM Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-deutschebank-sovereign-idUKTRE66Q1XR20100727 HSBS ended up with 15 Greek bank branches sold in 2022 to Pancreta Bank, see SA HSBC Reaches Agreement to Sell Greek Bank Branches to Pancreta Harry Wilson 03:00 PM IST, 14 Mar 2022 Read more at: https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/hsbc-reaches-agreement-to-sell-greek-bank-branches-to-pancreta Copyright © BloombergQuint. Both Deutsche Bank and HSBC where members of the Committee for the Greek PSI in 2012, the former being member of the Steering Committee. promote their own interests in any debt workout or exert strong restructuring pressure on the debtor country. As Cheng emphasizes (2020) “a handful of creditors could use (power) to promote their own interests in any debt workout or exert strong restructuring pressure on the debtor country” Cheng, G. (2020) The 2012 private sector involvement in Greece. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020. The private sector involvement, PSI, “restructured sovereign bonds issued by the Greek government and selected state-owned enterprises and held by private investors in March 2012, alleviating Greece’s overall debt burden” in same. |

| 43 | “The public pillar in the banking sector has to be restructured”… ATE will be thoroughly restructured as a stand-alone institution…The CDLF will be unbundled by end-March 2011…Concerning the Government stakes in Postbank and Attica, a sale is considered”.p.26 European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece Second review – autumn 2010 EUROPEAN ECONOMY Occasional Papers 72 |

| 44 | 11% of the GDP deficit reducing measures, complete restructuring of state-owned companies, scaling up of privatisations, pension and health care system reforms and many other structural reforms visited later in the course of this project. |

| 45 | fiscal austerity was considered necessary by the lenders “for several years to durably reduce the debt ratio” p.14 in EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece Fourth Review – Spring 2011. |

| 46 | Statement by the Eurogroup: 21 February 2012 in European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, The second economic adjustment programme for Greece : March 2012 review, Publications Office, 2012, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/20212

|

| 47 | “The Eurogroup considers that the necessary elements are now in place for Member States to carry out the relevant national procedures to allow for the provision by EFSF of (i) a buy back scheme for Greek marketable debt instruments for Eurosystem monetary policy operations, (ii) the euro area's contribution to the PSI exercise, (iii) the payment of accrued interest on Greek government bonds, and (iv) the residual (post-PSI) financing for the second Greek adjustment programme, including the necessary financing for recapitalisation of Greek banks in case of financial stability concerns”. Statement by the Eurogroup: 21 February 2012 |

| 48 | A previous less comprehensive PSI- I was conducted in July 2011 |

| 49 | “…the four core banks will have to acquire existing bridge banks and participate in purchase and assumption transactions with other banks undergoing resolution and to immediately start ambitious operational restructuring – including the downsizing of staff and the branch network. Concerning core banks that will not have been able to remain under private control, the strategy will include options and operational steps for the HFSF to promptly proceed with their privatisation”. European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece Second review – May 2013 EUROPEAN ECONOMY Occasional Papers 148 p.4 |

| 50 | The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece – Fourth Review presentation pp. 8-10 |

| 51 | European Commission Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece Fourth Review – April 2014 EUROPEAN ECONOMY Occasional Papers 192 p. 1 |

| 52 | MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION ACTING ON BEHALF OF THE EUROPEAN STABILITY MECHANISM AND THE HELLENIC REPUBLIC AND THE BANK OF GREECE https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/01_mou_20150811_en1.pdf

|

| 53 | EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS 9 JUNE 2016 Compliance Report The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece First Review June 2016, p.8 |

| 54 | “Action 25 - Amendments to the corporate insolvency law The Omnibus law (subparagraph C3) includes amendments to the corporate insolvency law necessary as a first step in the short term to improve the efficiency of legislative framework and procedure and help banks' efforts to recover NPLs. The institutions have received an action plan for addressing the issues associated to corporate bankruptcy judges (i.e. additional judges, longer term and training). DONE Action 26 - Amendments to the household insolvency law The Omnibus law (subparagraph A4) amends the household insolvency law to ameliorate the framework and address the excessive backlog of pending cases that lead to overly debtor friendly environment prone to abuse. The main changes to the framework refer to the introduction of a timebound stay on enforcement in line with cross country experience, the establishment of a stricter screening process to deter strategic defaulters from filing under the law, include public creditor claims in the scope of the law providing eligible debtors with a fresh start. Further measures to address the large backlog of cases were agreed (e.g. increasing the number of judges and judicial staff, prioritization of high value cases, and short-form procedures for debtors with no assets and no income). The Omnibus law demands to a Ministerial Decree the setting of criteria for the protection of the primary residence of truly vulnerable debtors. The authorities should issue primary legislation to tighten the eligibility criteria for protection of the primary residence while protecting the vulnerable debtor in line with the proposal made by the institutions”. EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 14 August 2015 Report on Greece's compliance with the draft MOU commitments and the commitments in the Euro Summit statement of 12 July 2015 p.8 |

| 55 | EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS Athens, 21 December 2015 Report on Greece's compliance with the second set of milestones of December 2015, p.4 |

| 56 | “Further measures have been put in place to help resolve the high amount of non-performing loans (NPLs). As part of the milestones package in December 2015, the authorities partially liberalised the market for the servicing of NPLs by non-bank financial companies and created the possibility for banks to sell certain categories of NPLs to non-banks. As prior action for the 1st review, the legislation dealing with NPLs was modified to remove tax and other impediments to the efficient functioning of these markets. The authorities liberalised the sale of all performing and non-performing loans with the only temporary exception for the sale of loans secured by primary residences with an objective value of the property up to EUR140,000, for which the liberalisation will enter into force on 1 January 2018”. EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS 9 JUNE 2016 Compliance Report The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece First Review June 2016 p.8 |

| 57 | Ibid, p.8 |

| 58 | Eurogroup Statements and remarks 9 May 2016 19:00 Eurogroup statement on Greece https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/05/09/eg-statement-greece/

|

| 59 | “…adopt amendments to Law 4354/2015 (Law on the Management of Non-Performing Loans, pay-setting arrangements and other emergency provisions in application of the agreement on budgetary targets and structural reforms) in order to allow without Greek law requiring a license the sale of all performing and non-performing loans to legal entities incorporated in any State member of the European economic area without exclusions or in any other State excluding non-cooperative States and States identified on 1 May 2016 as having a preferential tax regime (in the sense of article 65 paragraphs 1 to 7 of law 4172/2013). For loans secured by primary residences with an objective value of the property below €140,000 the liberalisation will enter into force on 1 January 2018;” Supplemental Memorandum of Understanding 16. 06. 2016 p.21 |

| 60 | EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS 16 JUNE 2017 Compliance Report The Third Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece Second Review June 2017, p. 15 |

| 61 | SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING (second addendum to the Memorandum of Understanding) BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION ACTING ON BEHALF OF THE EUROPEAN STABILITY MECHANISM AND THE HELLENIC REPUBLIC AND THE BANK OF GREECE 5 July 2017 p.26 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/smou_final_to_esm_2017_07_05.pdf

|

| 62 | SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING (second addendum to the Memorandum of Understanding) BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION ACTING ON BEHALF OF THE EUROPEAN STABILITY MECHANISM AND THE HELLENIC REPUBLIC AND THE BANK OF GREECE 5 July 2017 p.27 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/smou_final_to_esm_2017_07_05.pdf

|

| 63 | Supplemental Memorandum of Understanding: Greece Third Review of the ESM Programme p.21 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/third_smou_-_final.pdf

|

| 64 | EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE GENERAL ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL AFFAIRS UPDATE 9 JULY 2018 Compliance Report ESM Stability Support Programme for Greece Fourth Review July 2018 p.6 |

| 65 | “The two first NPL sales of Greek banks under the NPL market law were conducted in the second half of 2017 and the first quarter 2018 and involved highly provisioned unsecured loan portfolios, with a focus on consumer loans. Several additional NPL transactions are underway in 2018. In May the sale of the first major NPL transaction involving secured loans in Greece was announced by a Greek bank, marking an important next step in the creation of a dynamic NPL market in Greece. The transaction includes the sale of non-performing real-estate backed corporate credit exposures with a gross amount of around EUR 1,961 million”. Ibid p.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).