Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

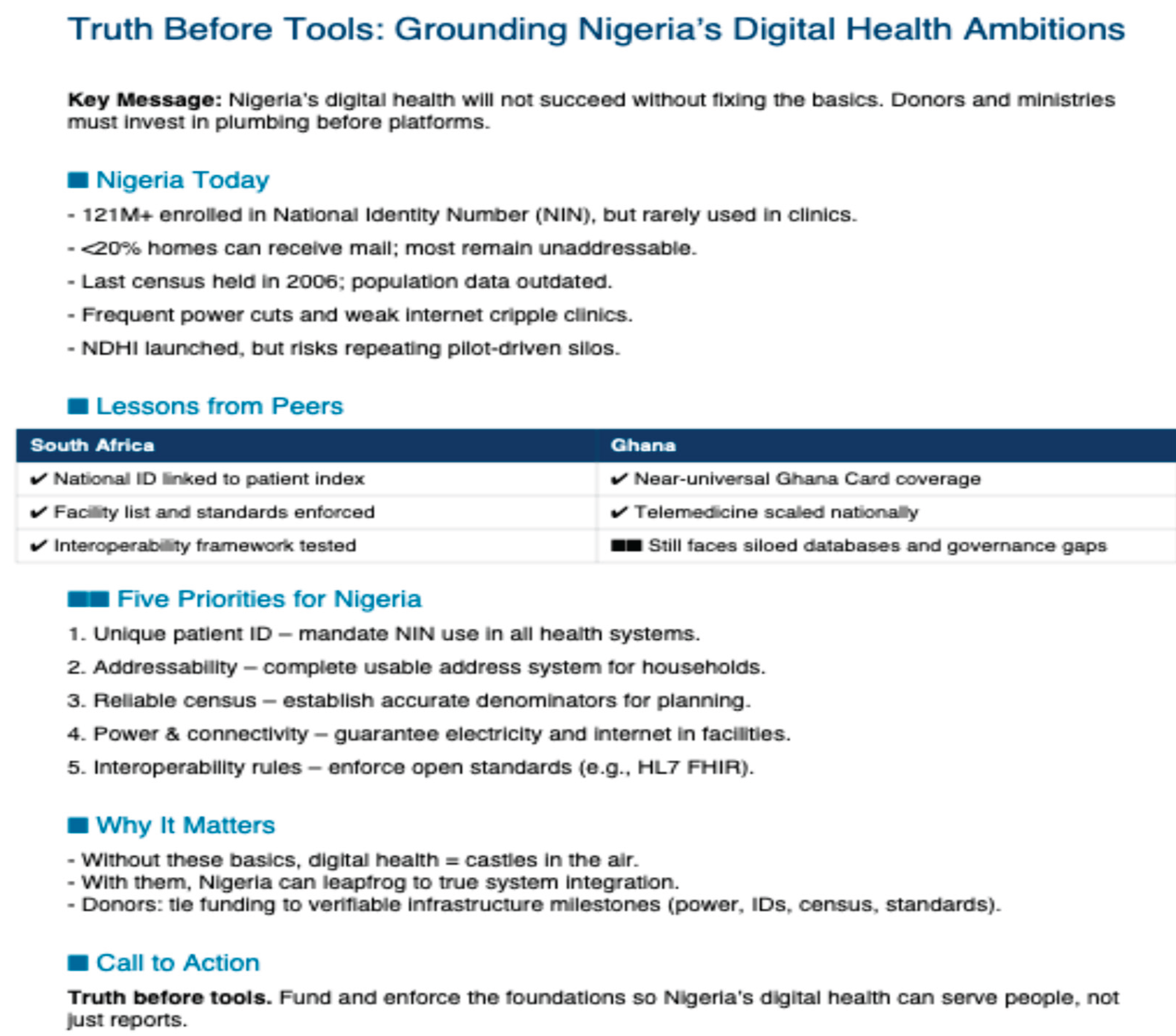

1. Summary Box

2. Introduction

- Addressability: Whole-country address systems (digital or hybrid) that enable accurate location of patients for care and logistics [1].

3. Conclusions

References

- Gbadeyanka M. NIPOST adopts 3 word addresses. Business Post Nigeria [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://businesspost.ng/general/nipost-adopts-3-word-addresses/.

- National Identification Authority (Ghana). Registration statistics [Internet]. 2025 Aug 20 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://nia.gov.gh/nia-registration-statistics/.

- National Identity Management Commission (Nigeria). NIN enrolment report—June 2025 [Internet]. 2025 Jun 30 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://nimc.gov.ng/nin/enrolment-report/june-2025.

- Reuters. Nigeria again postpones first census in 17 years. Reuters [Internet]. 2023 Apr 29 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigeria-again-postpones-first-census-17-years-2023-04-29/.

- South African National Department of Health. Annual Report 2023/24 [Internet]. Pretoria: NDoH; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/NDoH-Annual-Report-2023-24.pdf.

- IQVIA Institute. Digital Health Systems in Africa: A convergence of opportunities [Internet]. 2023 Sep 29 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/mea/white-paper/iqvia-digital-health-system-maturity-in-africa.pdf.

- Babatope AE, Adewumi IP, Ajisafe DO, Adepoju KO, Babatope AR. Assessing the factors militating against the effective implementation of electronic health records in Nigeria. Sci Rep. 2024;14:31398. [CrossRef]

- Cole OK, Abubakar MM, Isah A, Sule SH, Ukoha-Kalu BO. Barriers and facilitators of provision of telemedicine in Nigeria: A systematic review. PLOS Digit Health. 2025;4(7):e0000934. [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (Nigeria). Nigeria Digital in Health Initiative—overview and updates [Internet]. 2024–2025 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.ng/.

- National Department of Health, South Africa. National Digital Health Strategy for South Africa 2019–2024 [Internet]. Pretoria: NDoH; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/national-digital-strategy-for-south-africa-2019-2024-b.pdf.

- Knowledge Hub (South Africa). National Digital Health Strategy for South Africa 2019–2024—summary [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/elibrary/national-digital-health-strategy-south-africa-2019-2024.

- IQVIA Middle East & Africa. Digital Health Systems in Africa—landing page [Internet]. 2023 Sep 29 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/locations/middle-east-and-africa/library/white-papers/digital-health-systems-in-africa.

- Amon S. De facto health governance policies and practices in the decentralized health system of Ghana: implications for digital health. Health Policy Technol. 2024;13(2):100847. [CrossRef]

- Novartis Foundation. Ghana Telemedicine Program Evaluation. 2018. https://www.novartisfoundation.org/sites/novartisfoundation_org/files/2020-11/2018-the-promise-of-digital-health-exsum-en.pdf.

- Department of Health, South Africa. National 2021 Normative Standards Framework for Interoperability in Digital Health. Government Gazette No. 47337. Pretoria: Government of South Africa; 2022 Oct 21. Available from: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/HNSF_Gazette_21_October_2022.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025 [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020924.

| Dimension | Nigeria | South Africa | Ghana |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique ID | NIN enrolment > 121M; limited health use [3] | Universal national ID used in health [5,10] | Ghana Card with 18.9M enrolments [2] |

| Address system | Weak; 20% coverage; what3words adopted [1] | Functional postal and civic addressing [5] | Stronger urban addressing; rural gaps remain [13] |

| Census data | Last census 2006; repeated delays [4] | Regular censuses; reliable denominators [5] | Regular census updates [13] |

| Infrastructure | Frequent power cuts, poor connectivity [7,8] | Load-shedding but widespread broadband [5] | Mixed; better telecoms than Nigeria [6] |

| Interoperability | Fragmented, siloed systems [7,9] | National standards framework, enforced [10,14] | Siloed systems; weak enforcement [6,13] |

| Governance | NDHI launched; early stage [9] | National strategy (2019–2024) [10] | Emerging frameworks; partial implementation [6] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).