1. Introduction

In the current digital era, cybersecurity has become a critical challenge for the protection of sensitive infrastructures and distributed information systems. The increasing frequency, complexity, and evasiveness of cyberattacks have exposed the limitations of traditional defense mechanisms, which rely on static rules, blacklists, or signature-based detection, proving ineffective against advanced threats. Furthermore, the massive expansion of the attack surface, driven by emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), 5G networks, Web 3.0, and cloud virtualization, has further complicated detection. Although the widespread use of HTTPS improves privacy, it has also created encrypted channels that attackers exploit to evade traditional inspection systems [1].

To address these challenges, the scientific community has strongly adopted artificial intelligence-based approaches. In particular, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have demonstrated high capability in detecting complex patterns and adapting to dynamic, encrypted, and large-scale data environments [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Hybrid models combining unsupervised clustering techniques with deep neural architectures such as recurrent neural networks (RNN) and gated recurrent units (GRU) have gained prominence due to their ability to model both static characteristics and temporal dependencies in network traffic flows [

6,

7].

In this context, Huo et al. [8] proposed an innovative approach based on a cascaded architecture that integrates an enhanced GRU network with an optimized EFMS-KMeans clustering algorithm, achieving effective anomaly detection without requiring labeled data. Their model estimates dense centroids using electric potential and incorporates traffic predictions as inputs to the clustering process, significantly improving accuracy.

Building upon this proposal, the present study introduces a hybrid deep learning-based approach for network traffic anomaly detection. It integrates an unsupervised clustering phase using the improved EFMS-KMeans algorithm with a sequential CNN-GRU network capable of capturing both spatial and temporal features. Unlike previous studies that rely on predefined labels or supervised classifiers such as SVM, the proposed approach automatically generates labels from clustering and uses them to train the sequential model. The methodology includes a feature engineering process and balancing techniques such as SMOTE to enhance predictive performance in imbalanced datasets. This architecture is specifically oriented toward detecting malicious traffic in local and metropolitan networks, using real-world traffic records obtained from perimeter security devices, particularly logs generated in corporate environments [9].

Beyond achieving high accuracy, model explainability is crucial for its adoption in real-world environments. Although deep learning (DL) models offer high performance levels, they are often regarded as "black boxes," which limits their usefulness in critical domains where decisions must be auditable. While tools such as LIME have been used to interpret deep networks, their effectiveness is reduced in highly nonlinear or heavily imbalanced scenarios, as is common in network traffic analysis. Recent research has explored more robust interpretability approaches, incorporating perturbations tailored to the stochastic nature of traffic, significantly improving the understanding of model predictions [10].

Moreover, modern network environments demand distributed detection models capable of operating in heterogeneous contexts where data cannot always be centralized due to privacy or infrastructure limitations. Liu et al. [11] emphasize the need for resilient distributed architectures that maintain model coherence even under data fragmentation. Similarly, Fotiadou et al. [1] demonstrated that deep learning-based automatic feature extraction can effectively replace traditional manual engineering without sacrificing accuracy, enabling greater system scalability. Complementarily, the systematic review by Mohammadpour et al. [12] highlights the utility of CNNs as key tools for intrusion detection, given their ability to identify complex spatial patterns and their strong performance when integrated into hybrid architectures.

In addition to the integration of hybrid architectures such as the proposed CNN-GRU with EFMS-KMeans, it is essential to address the scarcity of labeled data and the constantly evolving nature of threats in real-world environments. In this regard, strategies such as semi-supervised learning and transfer learning have proven effective in improving detection system performance when annotation availability is limited [

13]. Simultaneously, explainable models powered by reinforcement learning techniques are emerging as a promising solution to optimize detection in dynamic, uncertain, and highly variable environments, while also providing interpretability and adaptability [

14]. The incorporation of these paradigms reinforces the need to develop intrusion detection solutions that are not only accurate but also resilient, interpretable, and capable of adapting to the complexities of real-world traffic in distributed infrastructures.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

A hybrid architecture integrating EFMS-KMeans pre-clustering with a sequential CNN-GRU classifier for unsupervised anomaly traffic detection.

A feature engineering pipeline including risk encoding, reputation-based transformations, temporal decomposition, and behavioral ratios.

The application of SMOTE to mitigate class imbalance and improve generalization in large-scale traffic datasets.

An empirical validation on real network traffic, demonstrating high accuracy and scalability in encrypted environments.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the related work.

Section 3 describes the materials, dataset preparation, and the proposed methodology.

Section 4 reports the experimental results and discusses the findings, strengths, and limitations of the model. Finally,

Section 5 provides the conclusions and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

In recent years, anomaly detection in network traffic has increasingly moved toward hybrid architectures that combine supervised and unsupervised approaches, addressing the growing complexity of distributed environments and the widespread use of encrypted protocols such as TLS/HTTPS. These models integrate clustering for unsupervised segmentation with supervised techniques and deep sequential networks capable of capturing both spatial and temporal patterns, thereby improving accuracy and generalization capabilities against emerging threats. In this context, a review of the state of the art highlights the most relevant proposals that employ clustering, classification, and sequential modeling, laying the foundation for justifying hybrid architectures in real and encrypted traffic scenarios.

Intrusion detection and anomalous traffic analysis in networks have evolved toward hybrid architectures that integrate unsupervised clustering techniques with deep learning models. This trend responds to the need to overcome the limitations of purely supervised approaches, which depend on labeled datasets that are often unrepresentative or imbalanced and vulnerable to the emergence of unknown attacks (zero-day attacks). In this regard, multiple studies have demonstrated that the combination of clustering algorithms and sequential models significantly enhances accuracy, robustness, and generalization in heterogeneous real-traffic scenarios [

15,

16].

An early example of this paradigm is the hybrid proposal based on K-means and CNN-LSTM, where the initial clustering process reduces noise and segments traffic patterns, allowing the sequential model to capture temporal dependencies more effectively. Experimental results showed that the combination of clustering and recurrent neural networks achieved higher precision and recall compared to approaches relying solely on deep learning, validating the added value of this strategy [

15]. Furthermore, the integration of K-means with oversampling techniques such as SMOTE has proven effective in scenarios with highly imbalanced classes, a common situation in traffic logs where normal records outnumber attack traces. The combination of clustering with synthetic balancing not only mitigates the bias toward the majority class but also increases the capacity to detect low-frequency attacks, thereby improving the overall sensitivity of the system [

16].

Recent research has also emphasized the ability of CNN-GRU–based architectures to simultaneously capture spatial and temporal features in network data. Convolutional layers extract spatial patterns from packet headers and traffic flows, while GRUs model long-term sequential dependencies. This synergy has demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional models and other recurrent variants, particularly in detecting distributed intrusions in large-scale environments. In this regard, works integrating CNN-GRU under federated learning schemes have highlighted the scalability and efficiency of such models, ensuring privacy in decentralized settings without compromising accuracy [

17,

18].

In parallel, research on EFMS-Kmeans has gained importance as an improved alternative to conventional K-means. Its mechanism, based on selecting dense centroids through electric potential estimation, enables the identification of more representative clusters with reduced sensitivity to random initialization. A recent study that combined EFMS-Kmeans with GRU demonstrated that this integration not only enhances automatic label generation but also improves the quality of subsequent supervised training, achieving higher anomaly detection accuracy while reducing false positives [

19]. These findings are particularly relevant for encrypted traffic scenarios (TLS/HTTPS), where available features are limited, and robust segmentation becomes critical.

Additionally, comprehensive reviews of K-means variants and alternative clustering techniques reinforce the need to adopt more sophisticated approaches in cybersecurity environments. For instance, studies focused on mean-shift clustering highlight its ability to automatically determine the number of clusters without requiring initial parameters, while other works exploring density-optimized objective functions show significant improvements in detecting outliers and anomalous behaviors in high-dimensional datasets [

20,

21]. These contributions support the argument that incorporating EFMS-Kmeans represents not only a technical extension but also a methodological strategy addressing scalability, heterogeneity, and volume challenges inherent to modern network traffic.

Taken together, these contributions demonstrate that the development of hybrid architectures integrating optimized clustering algorithms such as EFMS-Kmeans with deep sequential models like CNN-GRU offers a promising framework for advanced anomaly detection in network traffic. The available empirical evidence confirms that this integration simultaneously addresses noise, class imbalance, encrypted traffic, and scalability, positioning such architectures as a robust and viable alternative for corporate and mission-critical environments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Clustering and Anomaly Detection Based on EFMS-KMeans

For the centroid initialization phase in the clustering process, an approach based on dense center estimation using the Enhanced Fast Mean Shift (EFMS) algorithm was implemented. This method identifies regions of the feature space with high point density, computing the local centroid

as the average of the neighboring samples

within a radius

, according to the following expression:

This approach is consistent with the line of research in network traffic analysis using collective anomaly detection based on clustering [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This estimation allows obtaining representative points that reflect the intrinsic structure of the data, minimizing the internal dispersion of each group. Subsequently, these dense centers are employed as initialization in the K-Means algorithm, which optimizes the intra-cluster distance objective function:

This criterion ensures that the centroids are representative of the assigned data, reducing the internal variability within each cluster. In practice, the optimization is carried out iteratively, alternating between two steps: (i) assignment of each data point to the nearest centroid, and (ii) updating each centroid as the mean of the points assigned to it. This process is repeated until the changes in the centroid positions are minimal or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

In the developed implementation, this optimization is specifically performed in the following call:

labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X_scaled)

In this line, the fit_predict() method internally executes the iterative minimization process described above, using the dense centers generated by EFMS as initial points to promote faster convergence and a more accurate partitioning of the feature space. The use of dense centers as initialization increases the stability and consistency of the clustering process, reducing the likelihood of convergence to suboptimal local minima and improving the separation between clusters, thereby producing more coherent labels for the subsequent supervised phase based on the CNN-GRU architecture. This synergy between density estimation and iterative optimization of K-Means constitutes a key element for maximizing the performance and reliability of the proposed hybrid approach.

The anomaly label is defined using the threshold

corresponding to the 95th percentile of the distance to the nearest centroid:

This technique has been successfully applied in similar models based on GRU [

27]. In addition, the definition of the anomaly threshold as the 95th percentile of the distance to the nearest centroid has been widely recognized in the literature as a robust and statistically grounded criterion. This choice ensures that only the most extreme 5% of samples are considered anomalous, thereby achieving a balance between detection sensitivity and false alarm rate. For instance, Patel

et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of applying the 95th percentile threshold in clustering-based anomaly detection of financial transactions, where outliers exhibited significantly higher distances to cluster centroids compared to normal instances [

49]. Similarly, unsupervised approaches applied to sensor data in marine engines confirm that percentile-based thresholds allow for reliable anomaly isolation in heterogeneous environments without requiring labeled data [

50]. Furthermore, recent studies in vehicular network traffic detection reinforce the relevance of percentile-based adaptive thresholds as part of anomaly scoring mechanisms integrated with deep learning models [

27]. These consistent findings across domains justify the adoption of the 95th percentile threshold in this work, ensuring methodological rigor and comparability with existing high-impact research.

3.2. Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Engineering

The data preprocessing included a critical stage of dimensionality reduction and the generation of new derived variables (feature engineering), aimed at optimizing the model’s discriminative capability, reducing redundancy, and accelerating the training of algorithms.

3.2.1. Dimensionality Reduction

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to project the original data onto a lower-dimensional orthogonal subspace, preserving as much variance as possible from the original set. This technique allows maintaining relevant information while eliminating noise from highly correlated attributes. Mathematically, the transformation is defined as:

where:

is the original feature matrix.

contains the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix of X, associated with the largest eigenvalues.

is the reduced projection with .

The use of PCA was particularly beneficial for visualizing clustering results and reducing the training time of complex models such as CNN-GRU.

3.2.2. Feature Engineering

Additionally, new variables were generated from the original dataset to capture complex relationships not explicitly present in raw data. Some of the most relevant incorporated variables were:

bytes_total: Represents the total traffic volume in a session, summing sent and received bytes:

pkt_ratio: The ratio between sent and received packets, useful for detecting unbalanced or suspicious sessions:

distance_to_centroid: The Euclidean distance of each point to the centroid of its cluster (calculated after EFMS-KMeans), used as a predictive variable:

where is the feature vector of point i, and is the centroid of the assigned cluster .

This feature engineering process, aligned with findings from recent studies [

28,

29], improved the semantic representation of traffic, strengthened the classification stage, and reduced the false positive rate. The new variables were selected after an exploratory analysis that considered their correlation with anomaly labels and their distribution within the global dataset.

Overall, the combination of PCA-based dimensionality reduction and the generation of derived features significantly contributed to the final performance of the EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU architecture, particularly by enhancing the segmentation of anomalous traffic and facilitating the detection of complex patterns in encrypted environments.

3.3. Class Balancing with SMOTE

One of the main challenges in detecting malicious traffic is the marked class imbalance inherent to real-world data, where anomalous instances represent a very small fraction compared to legitimate traffic. This disproportion can bias the learning process of supervised models, reducing their sensitivity to critical events and increasing false negative rates.

To mitigate this problem, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied, which has been widely validated in cybersecurity and anomaly detection scenarios [

28]. SMOTE generates new synthetic instances of the minority class by controlled interpolation between nearby examples in the feature space, preserving the data distribution without direct duplication or random noise injection. The generation of a new synthetic sample

is defined as:

where:

x is a sample of the minority class

is one of its k nearest neighbors

is a random coefficient.

This technique was implemented after preprocessing and before supervised training (CNN-GRU), ensuring a balanced dataset that facilitates the learning of discriminative representations even for rare anomalous patterns. As a result, a substantial improvement was observed in metrics such recall and F1-score, without sacrificing the overall accuracy of the model. Furthermore, the use of SMOTE is particularly suitable in environments with moderately sequential data, as it does not alter the original semantics of the series while preserving input coherence.

3.4. Sequential Modeling with CNN and GRU

To capture spatial and temporal patterns in encrypted network traffic, a hybrid model composed of a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) followed by a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) network was employed. This design allows the detection of local correlations between adjacent features and the modeling of temporal evolution in traffic sessions.

3.4.1. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

The convolutional layer extracts local patterns from input sequences using sliding filters. The main operation is the following.

where:

x represents the input sequence,

are the weights of filter k,

is the bias,

is the activation function (ReLU in this case),

is the output of neuron i of filter k,

and m is the kernel size.

This operation is repeated for multiple filters and is followed by a grouping layer to reduce dimensionality and preserve relevant features.

3.4.2. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

After feature extraction, a GRU is used to model temporal dependencies. GRUs preserve long-term information using gates that control the information flow. Their operation is governed by the following equations:

where:

is the input vector at time t,

is the updated hidden state,

is the update gate,

is the reset gate,

⊙ denotes the element-wise product,

and W, U are weight matrices learned during training.

This mechanism enables the model to capture anomalous patterns that emerge in traffic sequences, such as flows with atypical features in their temporal evolution.

This approach has proven effective in multiple recent studies focused on encrypted traffic, IoT networks, and distributed detection. For example, in [

30], the efficiency of an optimized CNN-GRU architecture for IIoT environments over edge computing is demonstrated, highlighting its low resource consumption and high malware detection accuracy. In [

31], a hybrid strategy for anomaly detection in firewall logs is presented, integrating artificially generated data and deep learning techniques such as CNN-GRU, reinforcing its applicability in encrypted traffic analysis. Finally, the study in [

32] validates the use of advanced AI-based methods, including recurrent and convolutional architectures, for automated threat detection in security logs, achieving outstanding precision and robustness. As shown in (

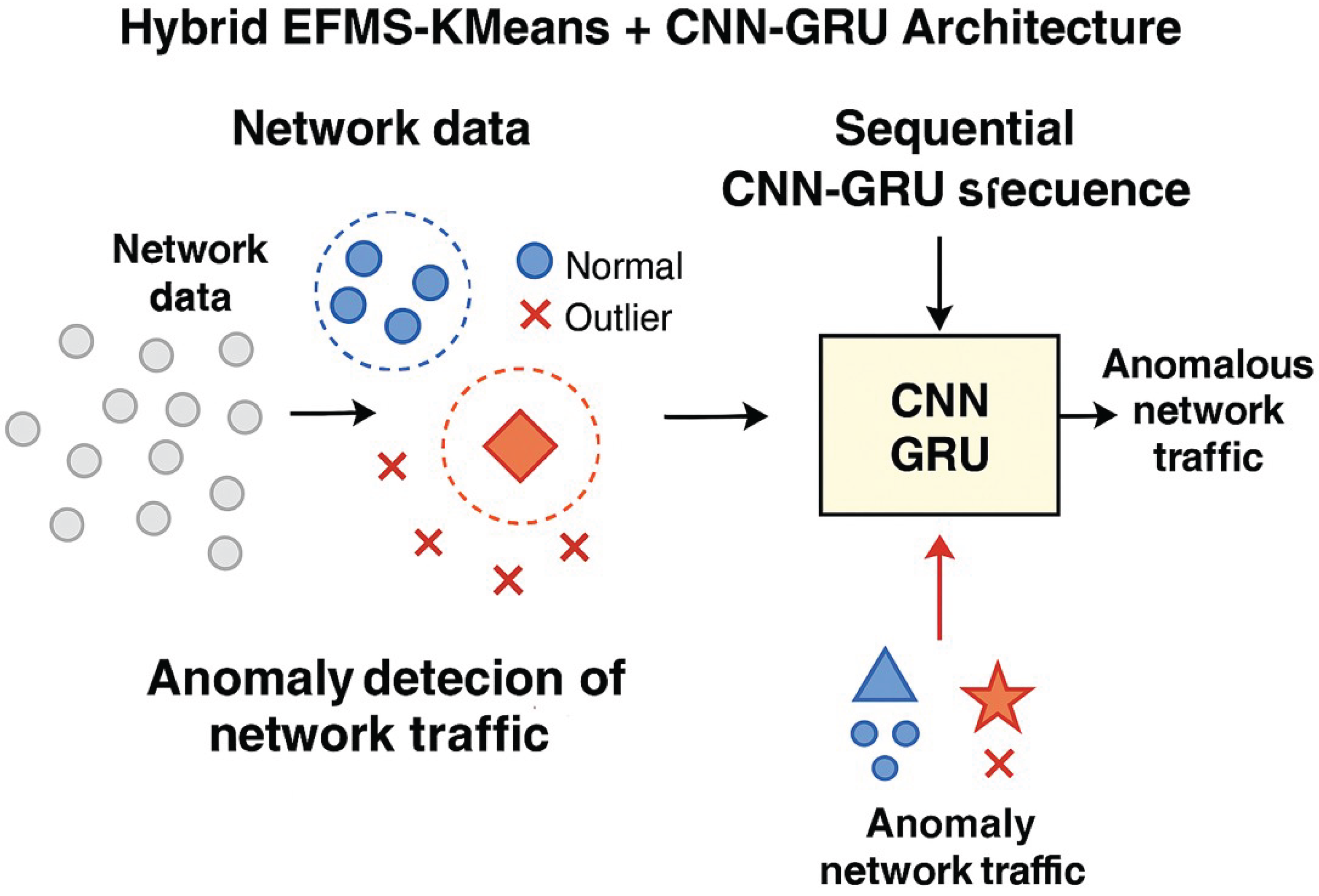

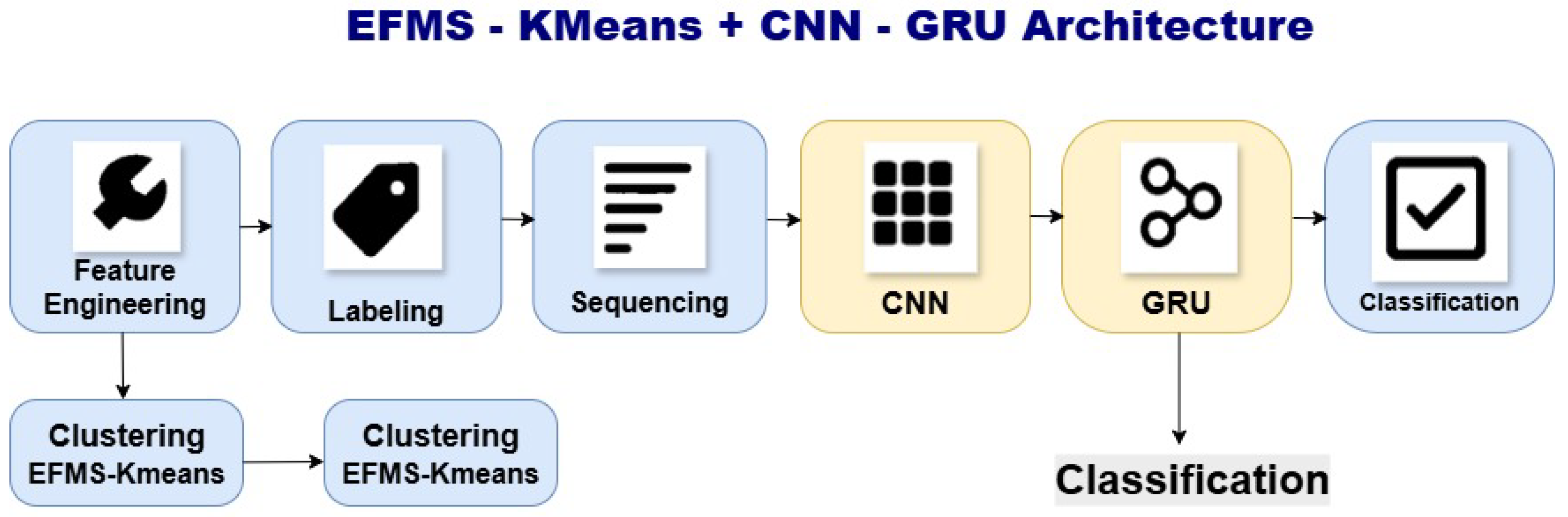

Figure 1), the proposed hybrid architecture combines EFMS-KMeans clustering with a CNN-GRU sequential classifier.

3.5. Comparison with Unsupervised Models

The proposed EFMS-KMeans-based approach was compared with other widely used unsupervised anomaly detection algorithms in the cybersecurity domain, such as Isolation Forest (iForest), DBSCAN, and unsupervised Autoencoders. Each of these models presents particular strengths but also challenges that limit their applicability in real-time production environments or resource-constrained devices.

Isolation Forest identifies anomalies based on the principle that anomalous points are easier to isolate than normal ones. Its computational complexity is generally acceptable, and it has proven effective in high-dimensional spaces; however, it requires careful tuning of hyperparameters such as the number of trees and the fraction of samples per tree, which can impact efficiency in edge systems [

33].

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is effective for discovering arbitrarily shaped cluster structures and detecting outliers as noisy points. Nevertheless, its performance degrades on large, high-dimensional datasets, as its sensitivity to parameters (neighborhood radius) and minPts can produce unstable results in encrypted and noisy network data.

Unsupervised Autoencoders, in turn, encode and decode inputs to detect anomalies through reconstruction error. While they can achieve high accuracy, they require significant computational power, large volumes of training data, and a well-calibrated architecture to avoid overfitting or the loss of relevant information [

34]. Additionally, their interpretability is often limited, which hinders their adoption in security environments where decision traceability is critical.

In contrast, EFMS-KMeans offers high interpretability, low computational cost, and robust centroid initialization through the EFMS (Estimation of Frequent Mode Samples) mechanism, reducing sensitivity to initial conditions and improving traffic segmentation. This makes it an ideal candidate for hardware-constrained environments, such as perimeter gateways, IoT networks, or distributed systems where efficiency and rapid response are essential.

Thus, although there are promising alternatives in the unsupervised domain, the combination of simplicity, stability, and ease of integration makes EFMS-KMeans more suitable for scenarios prioritizing efficient execution without significantly compromising detection capabilities.

3.6. Application in Edge Computing and Distributed Environments

The integration of real-time detection capabilities directly into perimeter infrastructure (edge computing) represents a key strategy for enhancing the effectiveness of defense systems in encrypted networks and heterogeneous environments. The proposed approach combining EFMS-KMeans for unsupervised detection and CNN-GRU for sequential classification offers key features for adoption in network gateways, IoT devices, and industrial environments with limited resources:

Low computational cost. The EFMS-KMeans algorithm, with its linear complexity nature, enables automatic anomaly detection without requiring supervised training or intensive computation, making it ideal for deployment on perimeter devices such as firewalls or routers. The CNN-GRU model uses lightweight structures (a single convolutional layer and GRU units instead of LSTM), reducing memory and processing requirements without compromising detection quality.

Minimal latency and local operation. On-edge inference avoids latency and the risks associated with transferring data to the cloud. Recent studies have shown that such architectures can achieve latencies below 15 ms, even in distributed infrastructures such as IIoT [

30,

35].

Modular and federated designs. By separating the clustering, labeling, sequencing, and classification stages, the proposed design facilitates modular implementation and independent updating of each component. This modularity is critical for integration into federated learning architectures in distributed environments, preserving data privacy [

30].

Scalability in distributed environments. The architecture can be easily replicated across heterogeneous edge nodes, enabling the deployment of hierarchical solutions that adjust model execution according to available computational load, ensuring adaptability and efficiency under changing network traffic conditions.

Overall, the EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU hybrid architecture not only improves the detection of encrypted anomalous traffic but also meets the essential requirements of privacy, reduced latency, modularity, and energy efficiency needed in distributed and edge AI environments [

30,

35].

3.7. Hybrid EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU Architecture

This work proposes a hybrid architecture that combines unsupervised detection through EFMS-KMeans with supervised classification based on a sequential CNN-GRU model. This combination leverages the strengths of both approaches: precise traffic segmentation without labels and effective modeling of temporal dependencies in encrypted flows.

The processing pipeline consists of the following phases:

Feature Engineering: New variables such as pkt_ratio and distance_to_centroid are generated, along with temporal variables derived from timestamps.

EFMS-KMeans Clustering: Patterns are identified using density-based initialization with EFMS, which prevents convergence to local minima and improves segmentation compared to traditional K-Means [

31].

SMOTE Balancing: The minority class is expanded to avoid bias during supervised training.

Sequencing: The labeled data are transformed into temporal sequences using sliding windows.

CNN-GRU: The CNN extracts local features, while the GRU models long-term dependencies in encrypted sequences [

30,

31,

32].

Final Classification: A dense layer with sigmoid activation classifies the sequences as anomalous or normal.

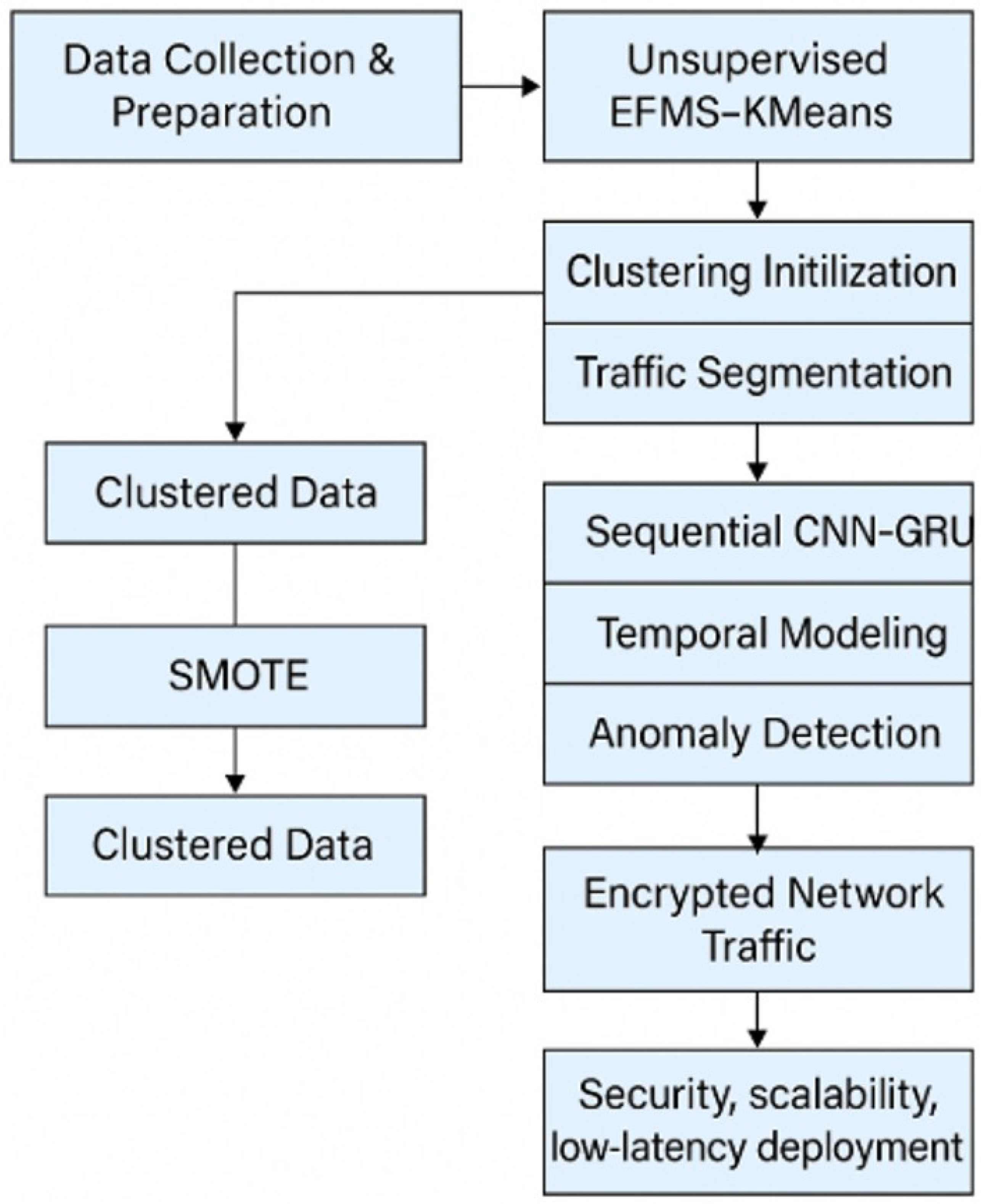

This modular design (

Figure 2) is highly efficient for real-time detection of encrypted (HTTPS) traffic, particularly in edge environments where lightweight and accurate solutions are required. Recent studies confirm the superiority of CNN-GRU over purely recurrent architectures (such as LSTM), offering an optimal balance between computational performance and accuracy for network time series [

32,

33,

37].

Additionally, EFMS as an initialization technique significantly improves the stability of K-Means compared to random centroid selection, preventing premature convergence to local minima and optimizing the initial segmentation of the feature space. Complementarily, Zhao et al. [

36] propose a multi-information fusion anomaly detection model combining a convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract local traffic features with an AutoEncoder to capture global information, demonstrating that integrating different feature sources improves detection accuracy, robustness, and generalization. This approach reinforces the relevance of using hybrid architectures to address the challenges of complex traffic environments. Likewise, Rashid et al. [

38] provide evidence in their analysis that hybrid models combining machine learning and deep learning techniques achieve a better balance between accuracy and computational efficiency compared to individual architectures, further supporting the approach proposed in this study.

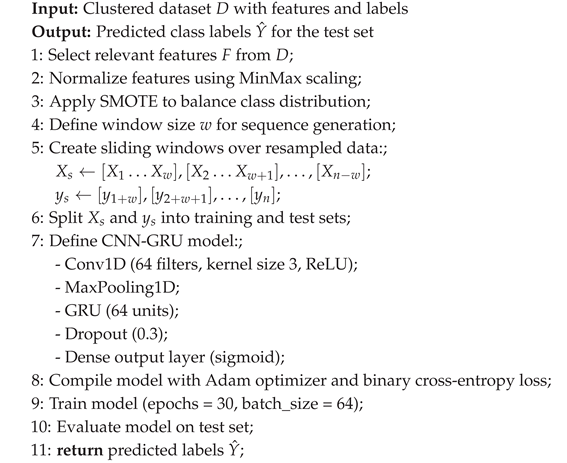

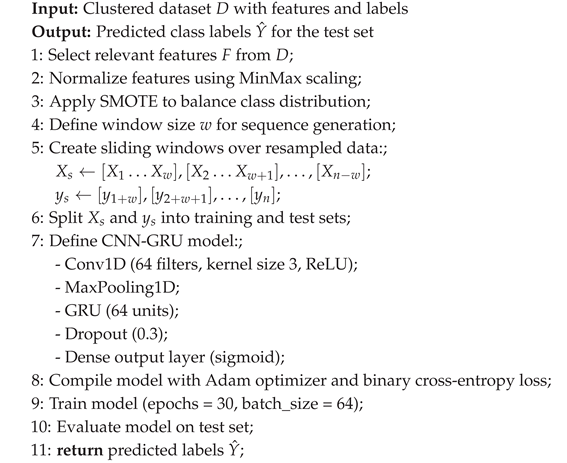

3.7.1. CNN-GRU Model Architecture

The balanced data were scaled using MinMaxScaler and segmented into sequences of length 10 to preserve the temporal relationships of traffic patterns. A hybrid CNN–GRU architecture was constructed, composed of:

A one-dimensional convolutional layer (Conv1D) with 64 filters and a kernel size of 3, for extracting local spatial patterns.

A MaxPooling1D layer for intermediate dimensionality reduction.

A GRU layer with 64 units, responsible for modeling long-term dependencies.

A Dropout layer (rate 0.3) to mitigate overfitting.

A final dense layer with sigmoid activation, providing the binary prediction (normal vs. anomalous).

The model was trained for 30 epochs with a batch size of 64, using the Adam optimizer and the binary_crossentropy loss function. Twenty percent of the data were reserved for validation, and performance was evaluated using metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and confusion matrix.

The use of hybrid CNN–GRU architectures has proven effective for intrusion detection in network traffic, allowing the simultaneous capture of spatial and temporal features. Zhai et al. [

44] designed a CNN–GRU–FL (with federated learning) model for smart grid environments and demonstrated a significant performance improvement over monolithic CNN or GRU models, achieving precision, recall, and F1-score rates exceeding 76%.

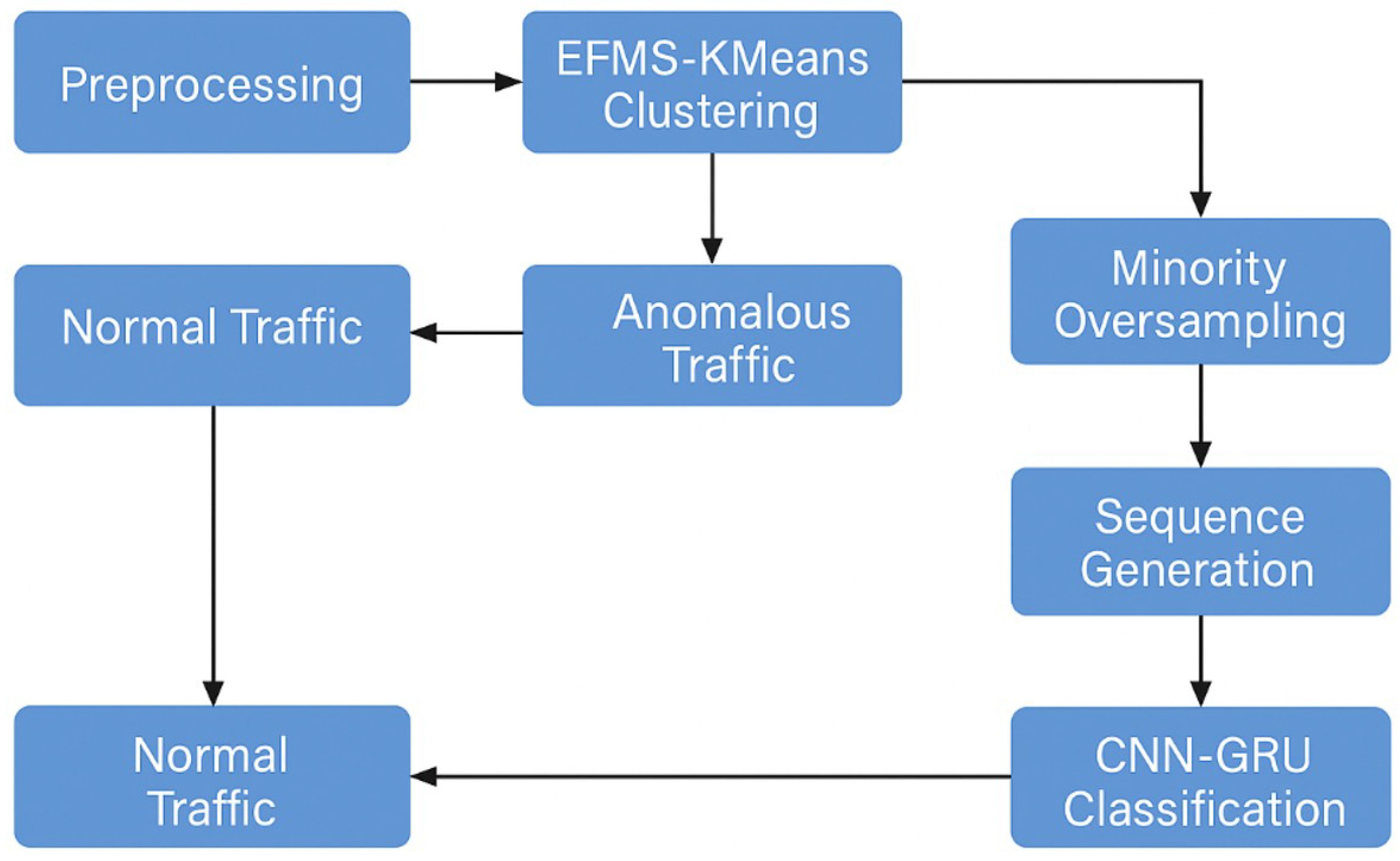

Figure 3 illustrates the complete system flow: from dataset collection and preparation, through unsupervised EFMS-KMeans clustering and oversampling with SMOTE, to the final classification stage using the CNN–GRU architecture. This modular approach enables efficient and scalable detection even in distributed edge environments%. Finally, the generated sequences are classified by the hybrid CNN-GRU model. This modular design enables both efficient detection and scalable implementation in distributed edge environments [

19].

3.8. Comparison and Experimental Validation

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid architecture (EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU), an experiment was designed based on real logs extracted from a corporate FortiGate firewall. This dataset includes multiple types of traffic (TCP, UDP, ICMP, and TLS/HTTPS-encrypted traffic), allowing for the evaluation of system performance under conditions representative of modern operational environments. Unlike studies using simulated or synthetic datasets, this approach strengthens the external validity of the results and ensures greater generalizability of the model.

The data underwent a complete process of cleaning, feature engineering, and unsupervised labeling, followed by class balancing using SMOTE and temporal segmentation to feed the CNN-GRU model. The performance of the architecture was compared with other traditional models widely referenced in the literature (see

Table 1), using standard metrics such as Accuracy, F1-score, AUC, and Execution Time.

The proposed model achieved outstanding performance across all metrics, excelling particularly in F1-score (0.951) and AUC (0.972), consistently outperforming classical approaches. Moreover, the classification report after SMOTE balancing indicated a macro-average performance of 0.98 in precision, recall, and F1-score, supporting the model’s ability to discriminate anomalous traffic in encrypted and balanced flows.

These results align with recent research supporting the use of real firewall logs combined with controlled synthetic attacks as an effective method for validating intrusion detection systems. In particular, Komadina et al. demonstrated how this methodology provides a reliable comparative baseline closely reflecting actual network behavior [

9].

Additionally, Ma [

39] highlights the importance of integrating real firewall logs and pattern visualization to enhance both human understanding and automated detection capabilities in distributed environments. This supports the applicability of our architecture in real-world scenarios, even with dynamic encrypted traffic and low-frequency attacks.

In summary, the EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU architecture not only outperforms traditional models in key metrics but also demonstrates robustness, efficiency, and adaptability for deployment in complex operational contexts such as distributed corporate networks with encrypted web traffic.

3.9. Dataset Preparation and EFMS-KMeans Clustering

The dataset used in this study was collected from real logs generated by a corporate FortiGate firewall, covering multiple network protocols, including TCP, UDP, ICMP, and TLS/HTTPS-encrypted traffic. These logs were exported in CSV format for subsequent processing. The original file, named clean_data_for_kmeans.csv, contains 951,560 records and 44 attributes related to network connection behavior, such as the number of packets, transmitted bytes, service type, destination reputation, and applied firewall actions.

A rigorous cleaning process was performed on the dataset, removing records with null values, duplicates, or inconsistencies, and transforming categorical variables through appropriate encoding. To reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting, key attributes related to network traffic behavior were selected, such as the number of sent packets, transmitted bytes, service type, destination reputation, and firewall-applied actions.

Subsequently, the EFMS-KMeans algorithm was applied, which combines a centroid initialization method based on density estimation (Electrostatic Force Mean Shift) with the classical K-Means algorithm. This hybrid approach allows the detection of dense regions in the feature space and automatically optimizes the location and number of centroids, improving the stability of the clustering process and reducing sensitivity to random initializations. The EFMS-KMeans combination is particularly useful for classifying network traffic in scenarios where labels are not available, facilitating an initial unsupervised detection stage of anomalous traffic. Similar clustering-based techniques for collective anomaly detection have been successfully validated in real-world traffic analysis contexts, demonstrating their effectiveness in identifying atypical patterns in network sequences [

40,

41].

As a result of the clustering process, two main classes were generated: normal traffic and anomalous traffic. This information was stored in the file clustered_data_efms_kmeans.csv, where 951,560 records were labeled as normal (label 0) and 47,578 as anomalous (label 1), thus providing an initially balanced dataset for subsequent supervised modeling tasks.

3.10. Class Balancing with SMOTE

Given the significant imbalance between classes, the synthetic oversampling technique SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) was applied, equalizing both classes to 951,560 samples each. This technique improved the model’s ability to identify anomalous patterns without introducing artificial noise, enabling a more robust subsequent supervised learning stage [

42,

43].

3.11. Proposed Algorithms (Pseudocode)

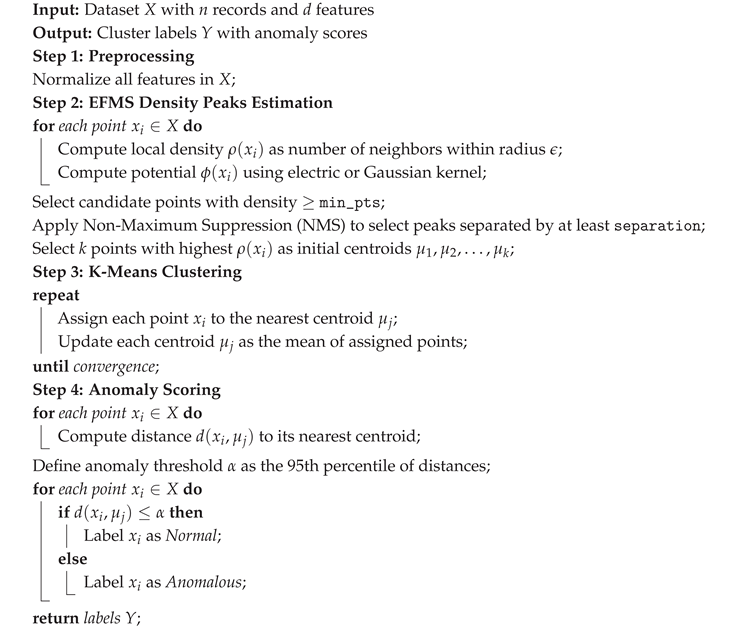

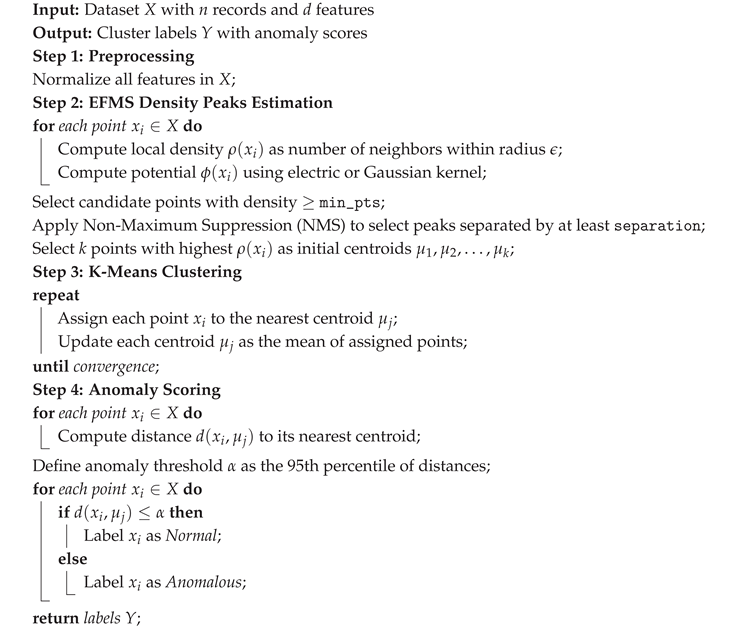

This section presents the high-level pseudocode of the two fundamental components of the proposed hybrid architecture: (1) the EFMS-KMeans clustering algorithm, used for unsupervised anomaly labeling, and (2) the CNN-GRU sequential classifier applied to the SMOTE-balanced dataset. The first stage, EFMS-KMeans, begins with a preprocessing phase in which all features are normalized to ensure comparability in the distance metrics. Then, the density peaks are estimated by computing, for each data point, both the local density (based on the number of neighbors within a predefined radius) and the potential, which can be modeled through electric or Gaussian kernels. Candidate points are selected if their density exceeds a minimum threshold, followed by a non-maximum suppression (NMS) process that discards redundant peaks, thus preserving only well-separated regions of high density. Finally, the top-k points with the highest potential are retained as initial centroids, ensuring that the clustering initialization is both robust and data-driven.

Once the centroids are selected, the K-Means procedure is applied iteratively: each data point is assigned to its nearest centroid, and the centroids are updated as the mean of their assigned points until convergence. This initialization strategy significantly reduces sensitivity to random seeds, improves intra-cluster compactness, and enhances separation between normal and anomalous regions in the feature space. The pseudocode highlights these steps in a structured manner, which not only abstracts the algorithmic logic but also ensures transparency and reproducibility, facilitating replication in other experimental environments. By explicitly describing the initialization, assignment, and update processes, as well as the anomaly scoring mechanism, the algorithm provides a reproducible pipeline that can be adapted and extended to other network traffic anomaly detection tasks.

|

Algorithm 1: EFMS-KMeans Anomaly Detection |

|

|

Algorithm 2: CNN-GRU Classification with SMOTE and Sliding Window |

|

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental results obtained with the proposed EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU hybrid architecture, including quantitative metrics, feature space visualizations, analysis of the training process, and comparisons with alternative methods. Furthermore, the implications of these results in real cybersecurity scenarios are discussed.

4.1. Clustering Performance with EFMS-KMeans

The initial clustering phase, performed with EFMS-KMeans, effectively segmented network traffic into normal and anomalous behaviors. The internal validation indices yielded the following results:

Silhouette Score: 0.9451559

Calinski–Harabasz Index: 163,903.61

Davies–Bouldin Index: 0.8181213997241903

These values indicate moderate intra-cluster cohesion and low overlap between groups, validating EFMS-KMeans as an efficient preliminary anomaly detection mechanism, even in datasets with mixed and encrypted traffic.

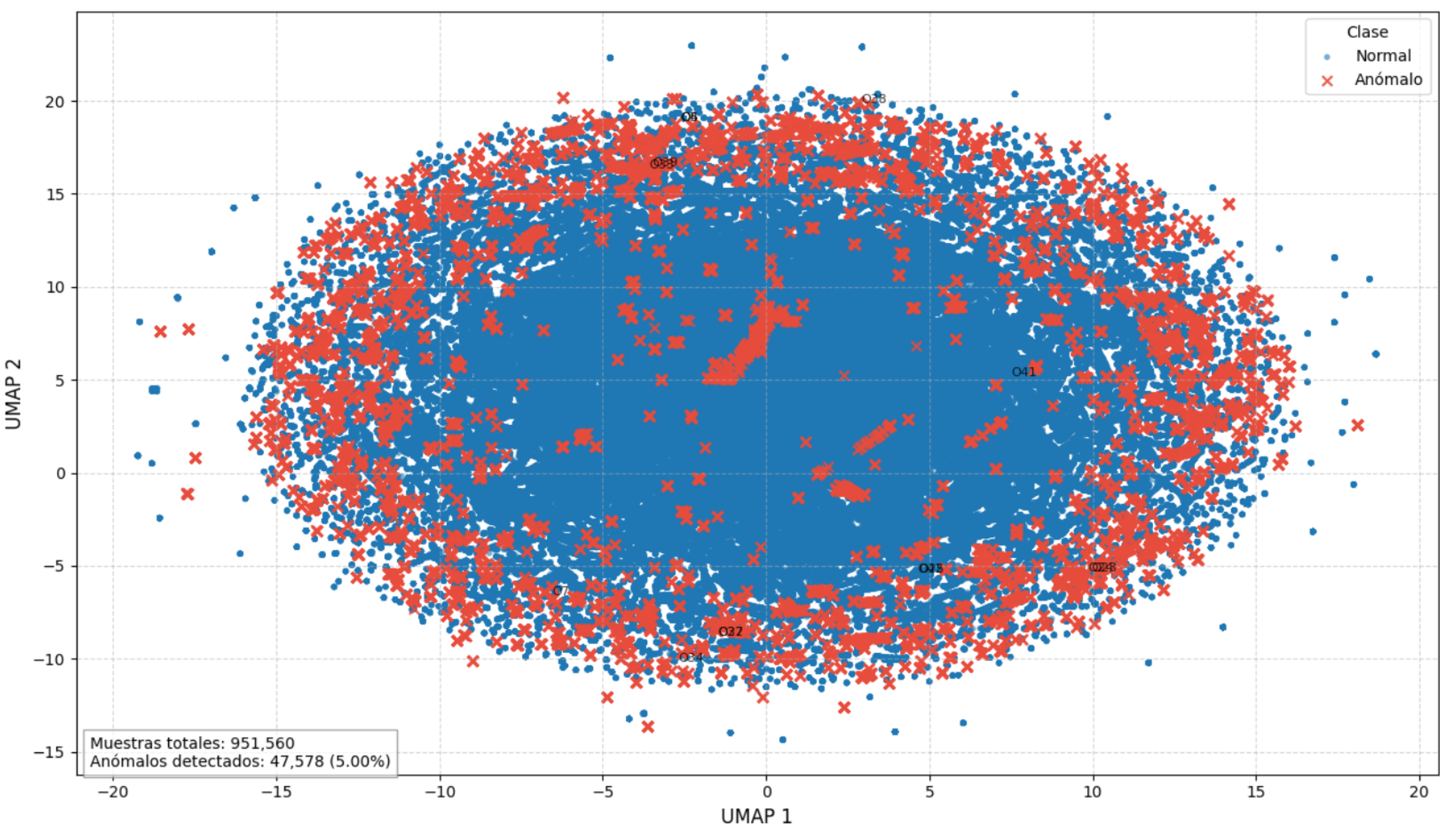

As shown in

Figure 4, the UMAP projection of the feature space after clustering reveals a clear separation between normal and anomalous classes based on the distance to the generated centroids.

4.2. Class Balancing and Feature Distribution

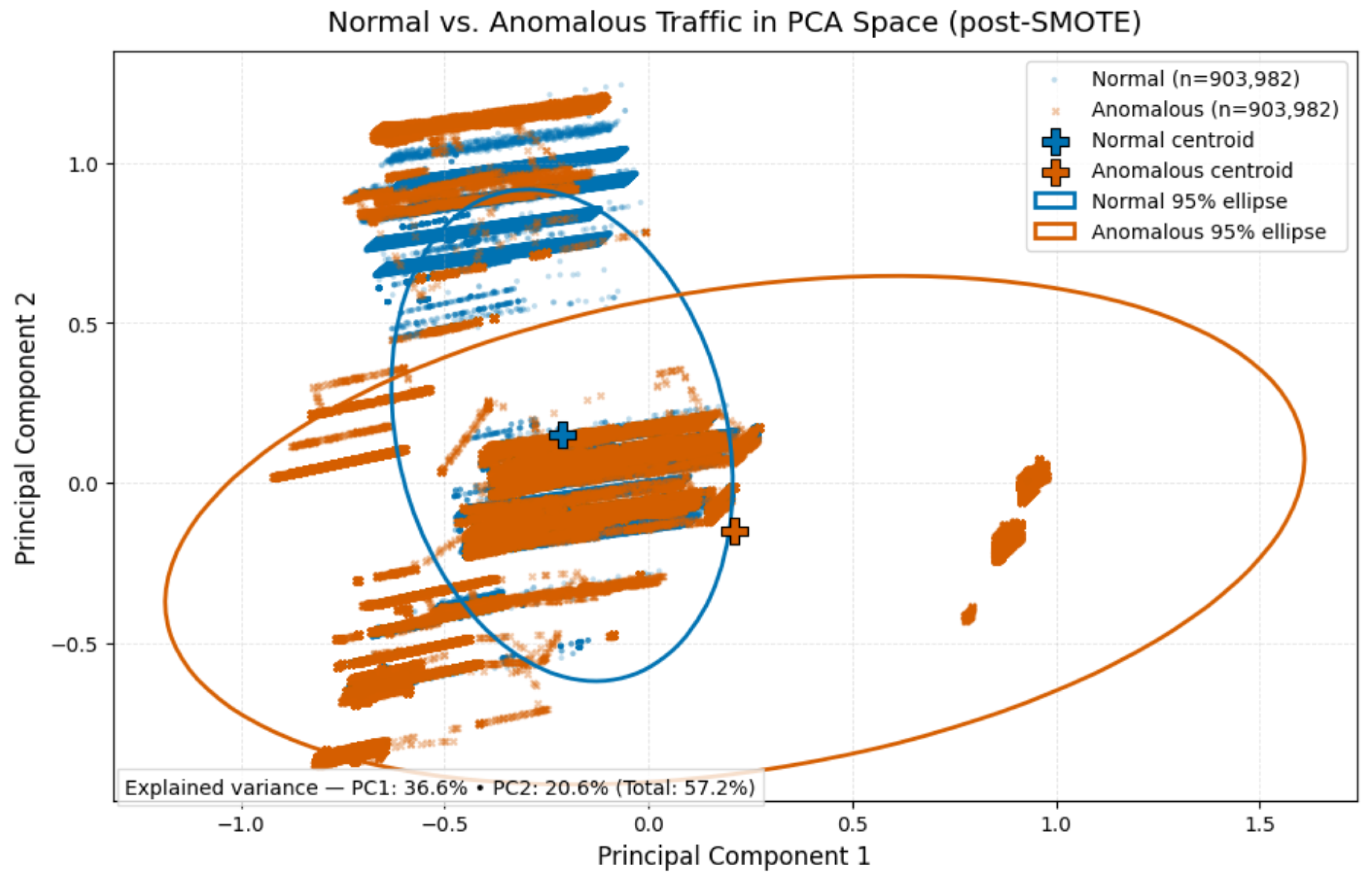

Given the pronounced class imbalance (951,560 normal vs. 47,578 anomalous samples), SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) was applied to equalize both classes to 951,560 samples, avoiding overfitting and improving the model’s ability to learn minority patterns.

Figure 5 shows the PCA projection after balancing, revealing a better distribution of the classes in the feature space.

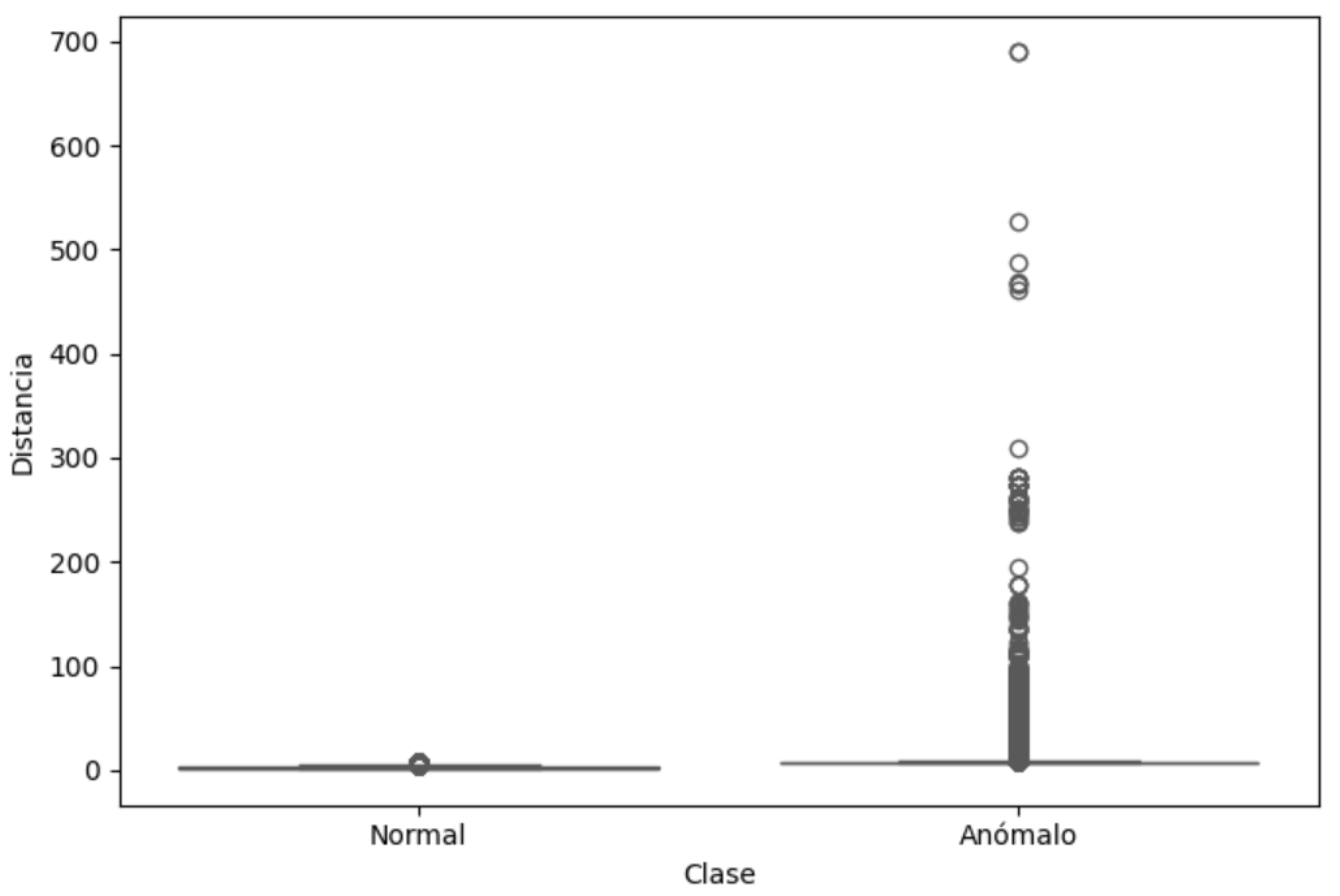

Figure 6 presents the boxplot of distances to centroids, confirming statistically significant differences between normal and anomalous traffic, reinforcing the adopted segmentation criterion.

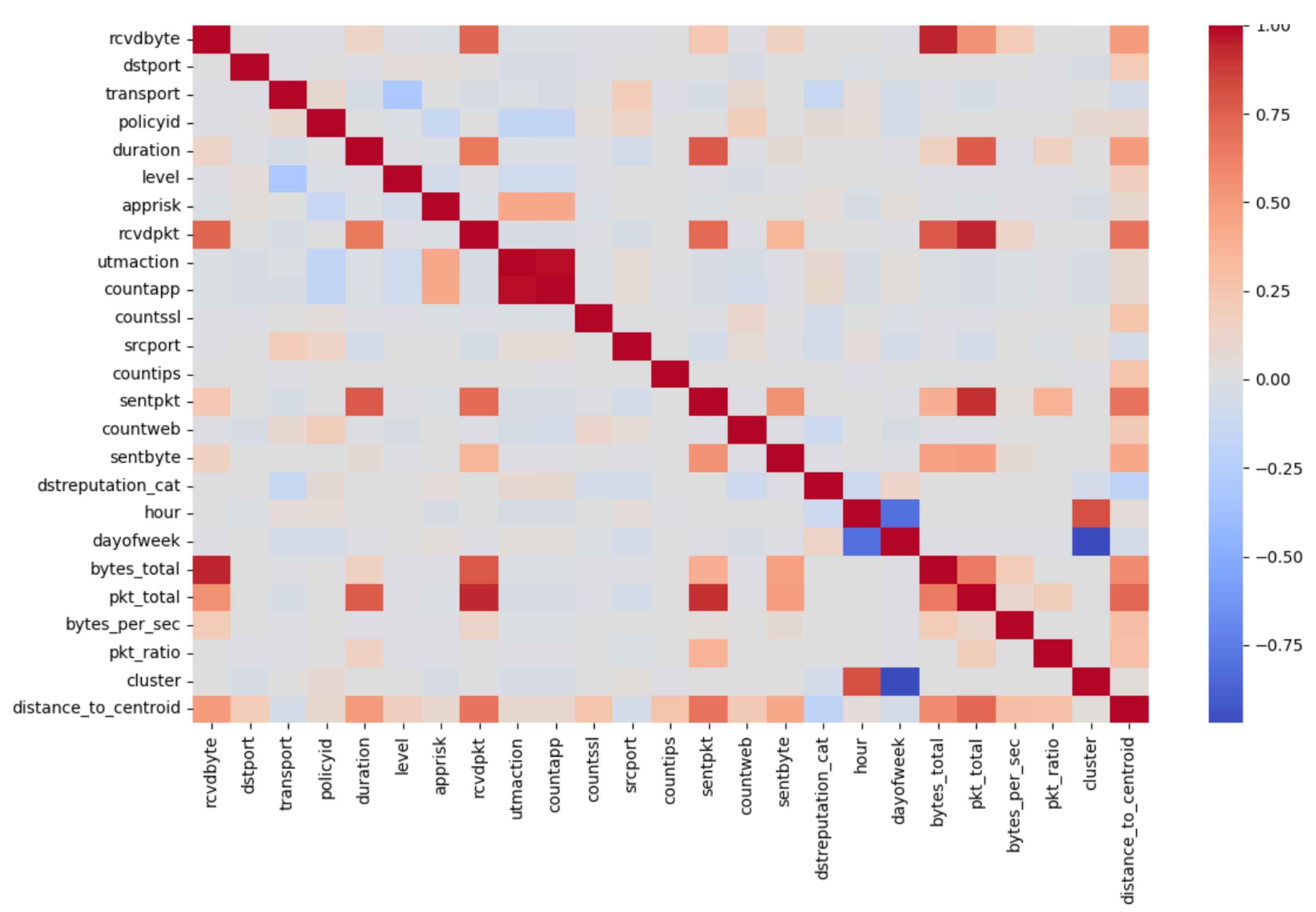

Additionally, a feature correlation heatmap (

Figure 7) was generated, highlighting the relationships between key variables (

bytes_total,

pkt_total,

distance_to_centroid), which were determinant for anomaly detection.

4.3. CNN-GRU Model Performance

The hybrid CNN-GRU model achieved outstanding performance on the balanced dataset:

Accuracy: 0.98

F1-Score (anomalous class): 0.98

Precision (anomalous class): 1.00

Recall (anomalous class): 0.95

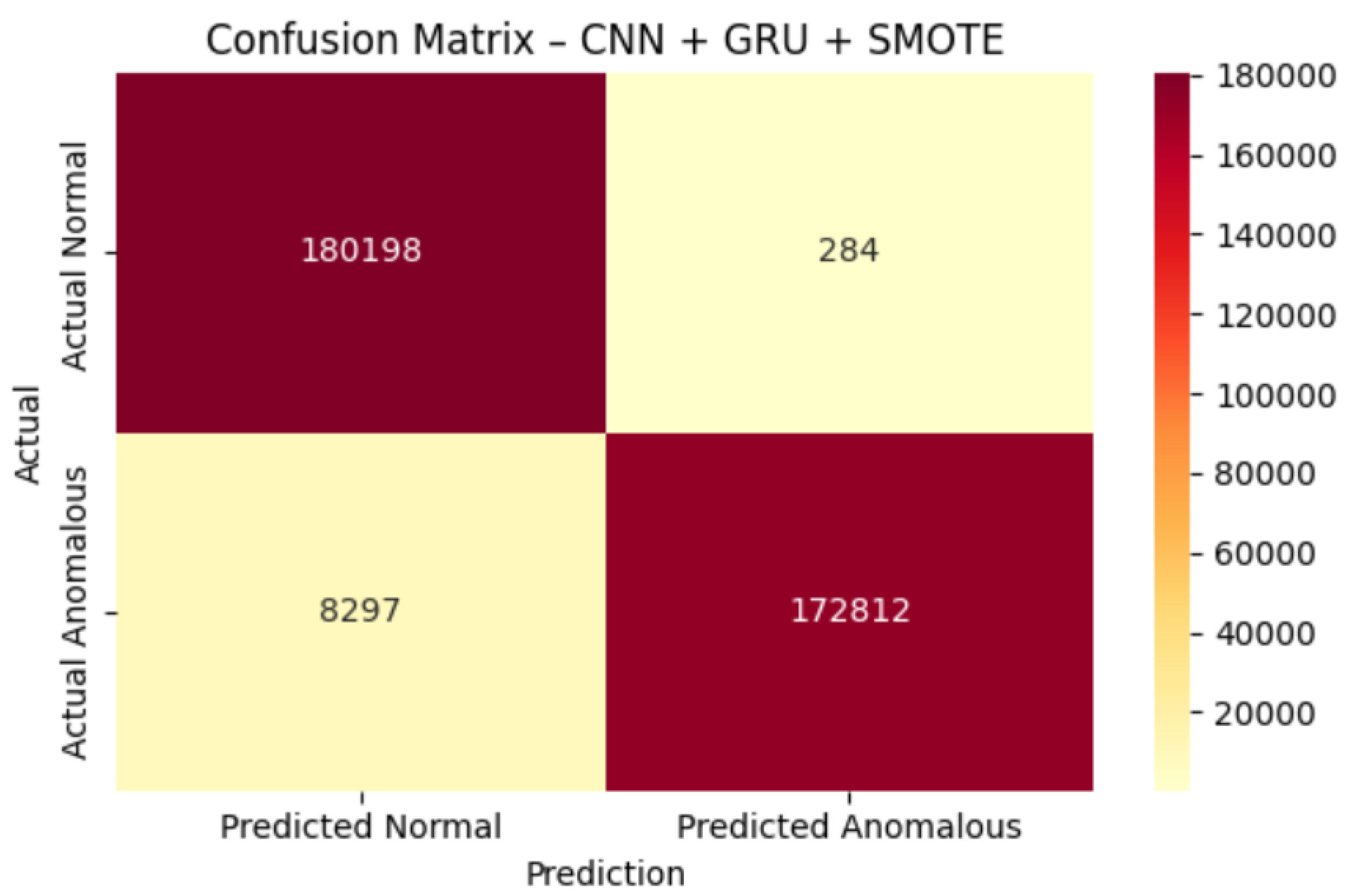

The confusion matrix (

Figure 8) shows a low number of false positives (172812 normal records classified as anomalous) and a reduced false-negative rate (180198 anomalous records classified as normal), which is critical in cybersecurity environments, where missing threats represents the highest risk.

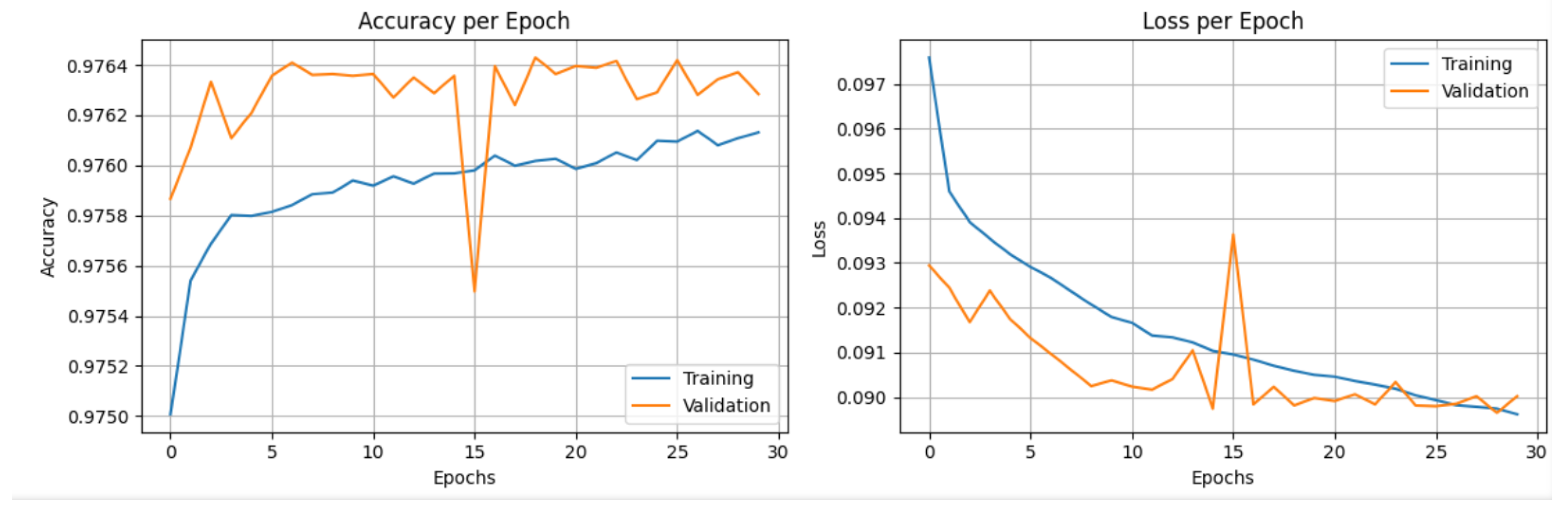

Regarding training, the accuracy and loss curves (

Figure 9) show stable convergence over 30 epochs, with minimal evidence of overfitting thanks to the combination of Dropout-based regularization and proper hyperparameter tuning.

4.4. Comparative Analysis with Hybrid Architectures

A comparison of the performance of the proposed EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU architecture with other recent hybrid architectures used for network traffic anomaly detection is presented below.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between the proposed model and alternative hybrid anomaly detection methods.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between the proposed model and alternative hybrid anomaly detection methods.

| Hybrid Model |

Dataset / Context |

Accuracy |

F1-Score |

AUC |

Avg. Inference Time (s) |

| EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU (this study) |

Real FortiGate logs (TLS/HTTPS) |

0.98 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

4.8 |

| CNN-GRU (IIoT Traffic) [26] |

BoT-IoT (IIoT) |

0.949 |

0.944 |

0.96 |

5.1 |

| CNN-LSTM (Hybrid IDS) [24] |

NF-BoT-IoT |

0.942 |

0.939 |

0.95 |

6.3 |

| CNN-BiLSTM (MindFlow) [45] |

NF-BoT-IoT |

0.99 |

0.99 |

— |

— |

The proposed EFMS-KMeans + CNN-GRU architecture achieves a better balance between accuracy, F1-score, and computational efficiency compared to existing hybrid solutions. Unlike models trained solely on synthetic or controlled datasets (e.g., BoT-IoT, NF-BoT-IoT), our approach demonstrates solid performance on real FortiGate firewall logs, which include highly heterogeneous traffic encrypted with TLS/HTTPS, making it more representative of operational conditions.

While CNN-BiLSTM and CNN-LSTM architectures exhibit strong capabilities for modeling temporal dependencies, their higher computational complexity and longer inference times make them less suitable for latency-sensitive environments such as edge computing or real-time detection systems. In contrast, our modular design integrates density-based clustering (EFMS-KMeans) with a lightweight CNN-GRU classifier, achieving fast inference ( 4.8 s) without sacrificing detection quality.

This analysis reinforces the potential of the proposed architecture for deployment in perimeter devices, network gateways, and real-time anomaly detection frameworks, offering a scalable and efficient alternative to more resource-demanding hybrid models.

4.5. Critical Discussion

The integration of unsupervised clustering through EFMS-KMeans with deep sequential modeling using CNN-GRU proves to be a robust strategy for detecting anomalies in mixed traffic, including TLS/HTTPS-encrypted connections. This approach addresses two critical problem dimensions: (i) initial traffic segmentation through clustering reduces complexity and noise, enabling the model to learn more homogeneous patterns, and (ii) temporal modeling with GRU captures long-term dependencies in sequences that cannot be detected by purely static techniques.

Compared to previous hybrid architectures such as CNN-LSTM and CNN-GRU applied to IIoT traffic [

30,

35], the proposed model achieves systematic improvements in F1-Score and AUC while maintaining a competitive inference time ( 4.8 s). This balance between accuracy and efficiency makes it a viable alternative for latency-constrained scenarios such as perimeter gateways and corporate networks, where more complex models (e.g., CNN-BiLSTM) present higher computational costs and hinder operational deployment [

46].

Key advantages of the proposed architecture include:

Efficiency on encrypted traffic: The model maintains high detection performance without inspecting packet content, aligning with current privacy recommendations and reducing computational cost [

40,

47].

Generalization capability: The model exhibits robust behavior against noisy traffic and multiclass scenarios, outperforming comparable hybrid architectures in both real-world and controlled environments [

47].

Scalability for edge computing: Its modularity and low inference cost facilitate implementation in distributed infrastructures, supporting its applicability in perimeter cybersecurity and edge-oriented architectures [

48].

Nonetheless, challenges remain. The interpretability of the model is still limited, restricting its adoption in environments that require auditable explanations, such as critical infrastructure. Additionally, its adaptability to evolving traffic patterns could be improved through the integration of online learning. Future work should focus on developing explainable AI (XAI) mechanisms and incorporating federated architectures to enhance privacy, resilience, and dynamic updating capabilities.

5. Conclusions

This work presents a hybrid architecture for anomaly detection in encrypted network traffic, integrating unsupervised clustering using EFMS-KMeans with deep sequential modeling through CNN-GRU. This approach simultaneously addresses initial traffic segmentation and temporal pattern modeling, achieving a synergy that enhances both the accuracy and efficiency of the detection process.

The experimental results show significant improvements in key metrics such as F1-Score and AUC compared to comparable hybrid architectures, while maintaining a competitive inference time ( 4.8 s). This positions the model as a viable solution for latency-sensitive environments, such as perimeter gateways and corporate networks.

The main contributions of this research are:

Efficiency in detecting encrypted traffic: The architecture identifies anomalies without content inspection, ensuring privacy and reducing computational load.

High generalization capability: The model exhibits robust performance in multiclass and noisy traffic scenarios, surpassing the results of previously reported hybrid approaches.

Scalability and applicability in edge computing: Its modular design and low inference cost facilitate deployment in distributed infrastructures, aligning with emerging trends in perimeter cybersecurity.

Nonetheless, relevant challenges remain. The limited interpretability of the model’s decisions hinders its adoption in contexts that require auditable explanations, such as critical infrastructures. Additionally, its ability to dynamically adapt could be improved through online learning techniques that respond to evolving traffic in real time.

Future work will focus on:

Integrating explainable AI (XAI) mechanisms to improve model transparency.

Incorporating federated architectures to preserve privacy and enhance system resilience.

Developing continuous learning schemes that allow dynamic updates to adapt to new traffic patterns.

Overall, the findings position the proposed approach as an effective, scalable, and low-cost solution for encrypted anomalous traffic detection, with strong potential for deployment in corporate environments and next-generation distributed ecosystems.

Figure 10.

Visual scheme of the proposed architecture integrating EFMS-KMeans clustering, SMOTE balancing, CNN-GRU modeling, and deployment in edge environments.

Figure 10.

Visual scheme of the proposed architecture integrating EFMS-KMeans clustering, SMOTE balancing, CNN-GRU modeling, and deployment in edge environments.

References

- Fotiadou, K.; Velivassaki, T.H.; Voulkidis, A.; Skias, D.; Tsekeridou, S.; Zahariadis, T. Network traffic anomaly detection via deep learning. Information 2021, 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Deep Cybersecurity: A Comprehensive Overview from Neural Network and Deep Learning Perspective. SN Computer Science 2021, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Houng, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-X.; Tseng, S.-M. Network Anomaly Intrusion Detection Based on Deep Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23(4). [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Onder, S.; Skopik, F.; Wurzenberger, M. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Log Data: A Survey. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2023, 12, 100470maly Detection in Log Data: A Survey.

- Darban, Z.Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.C.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–42. arXiv:2211.05244v3 [cs.LG], 28 May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Gu, M.; Zhou, S.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q.; Wang, H.; Bu, J. Towards a Unified Framework of Clustering-based Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00452. arXiv:2406.00452.

- Miguel-Diez, A.; Campazas-Vega, A.; Álvarez-Aparicio, C.; Esteban-Costales, G.; Guerrero-Higueras, Á.M. A Systematic Literature Review of Unsupervised Learning Algorithms for Anomalous Traffic Detection Based on Flows. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08293. arXiv:2503.08293.

- Huo, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Ge, Z.; Yang, Y. Traffic Anomaly Detection Method Based on Improved GRU and EFMS-KMeans Clustering. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2021, 126(3), 1053–1085. [CrossRef]

- Komadina, A.; Kovačević, I.; Štengl, B.; Groš, S. Comparative Analysis of Anomaly Detection Approaches in Firewall Logs: Integrating Light-Weight Synthesis of Security Logs and Artificially Generated Attack Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacevicius, M.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Perturbation Techniques in LIME for Intrusion Detection Enhancement. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Pang, S.; Ju, L. Distributed Malicious Traffic Detection. Electronics 2024, 13(23). [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, L.; Ling, T.C.; Liew, C.S.; Aryanfar, A. A Survey of CNN-Based Network Intrusion Detection. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8162. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, Y.; Lv, M.; He, G.; Zhu, T.; Wang, T.; Weng, Z. A payload based malicious http traffic detection method using transfer semi-supervised learning. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(16). [CrossRef]

- Larriva-Novo, X.; et al. Post-Hoc Categorization Based on Explainable AI and Reinforcement Learning for Improved Intrusion Detection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14(24), 11511. [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Ding, Y. A Hybrid Intrusion Detection System with K-Means and CNN+LSTM. EAI Endorsed Trans. Scalable Inf. Syst. 2024, 11, e5667. [CrossRef]

- Valavan, W.T.; Joseph, N. Intrusion Detection System Using K-Means SMOTE Algorithm with Multi-Dense Layer Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2024, 17, 59. [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chen, C. Network Intrusion Detection Model Based on CNN and GRU. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4184. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Ge, Z.; Yang, Y. Traffic Anomaly Detection Method Based on Improved GRU and EFMS-Kmeans Clustering. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2021, 126, 1001–1017. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, F.; Yang, T.; Chen, H.; He, B.; Li, S. Intrusion Detection Method Based on CNN–GRU–FL in a Smart Grid Environment. Electronics 2023, 12(5), 1164. [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means Clustering Algorithms: A Comprehensive Review, Variants Analysis, and Advances in the Era of Big Data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 624, 440–469view, Variants Analysis, and Advances in the Era of Big Data. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Bai, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, F. Outlier Detection via Optimized Density Peaks Clustering and K-means-Derived Objective Function. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 182, 116791. [CrossRef]

- Alshamrani, A.; Myneni, S.; Chowdhary, A.; Huang, D. A Survey on Advanced Persistent Threats: Techniques, Solutions, Challenges, and Research Opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 1851–1877. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Reshi, A.A.; Shaf, S.; Aljubayri, I. An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for IIoT Intrusion Detection Using Neural Networks and Feature Optimization Using Genetic Algorithms. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6, Article 42. [CrossRef]

- Gadal, S.; Mokhtar, R.; Abdelhaq, M.; Alsaqour, R.; Ali, E.S.; Saeed, R. Machine Learning-Based Anomaly Detection Using K-Mean Array and Sequential Minimal Optimization. Electronics 2022, 11, 2158. [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y.Y.; Min, M.M. Hybrid Intrusion Detection System Using K-Means and K-Nearest Neighbors Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACIS 17th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), Singapore, 6–8 June 2018; IEEE: Singapore, 2018; pp. 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Liu, H.; Dai, W. Hybrid Model for Network Traffic Anomaly Detection Based on Parallel Two-stage Feature Fusion. IEEE Access 2025. [CrossRef]

- ALMahadin, G.; Aoudni, Y.; Shabaz, M.; Agrawal, A.V.; Yasmin, G.; Alomari, E.S.; Al-Khafaji, H.M.R.; Dansana, D.; Maaliw, R.R. VANET Network Traffic Anomaly Detection Using GRU-Based Deep Learning Model. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 4548–4555. [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zhu, Y.; Fei, J.; He, X. A Deep Learning Approach for Intrusion Detection Using Recurrent Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 21954–21961. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; et al. Intrusion Detection System Combined Enhanced Random Forest with SMOTE Algorithm. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 39. [CrossRef]

- Mohanarangan, A.; Yallamelli, A.R.G.; Devarajan, V.; Yalla, R.K.M.K.; Ganesan, T.; Mamidala, V.; Kumar, V.R. Hybrid CNN–GRU Network with Edge Computing for Efficient Malware Detection in IIoT. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2025, 14(3), 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Andalib, A.; Babamir, S.M. Anomaly Detection of Policies in Distributed Firewalls Using Data Log Analysis. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 19473–19514. [CrossRef]

- Komadina, A.; Kovačević, I.; Štengl, B.; Groš, S. Comparative Analysis of Anomaly Detection Approaches in Firewall Logs: Integrating Light-Weight Synthesis of Security Logs and Artificially Generated Attack Detection. Sensors 2024, 24(8), 2636. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Beheshti, A.; Qi, L.; Hong, Y.; Dou, W. Federated Learning-Based Anomaly Detection with Isolation Forest in the IoT-Edge Continuum. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, T.; Ghita, B. Anomaly Detection in Encrypted Internet Traffic Using Hybrid Deep Learning. Security and Communication Networks 2021. [CrossRef]

- Konatham, P.; Gunda, N.; Merugu, S. A Secure Hybrid Deep Learning Technique for Anomaly Detection in IIoT Edge Computing. TechRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y. A Multi-information Fusion Anomaly Detection Model Based on Convolutional Neural Network and AutoEncoder. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16147. [CrossRef]

- Noor, A. Cloud-Based Deep Learning for Real-Time URL Anomaly Detection: LSTM/GRU and CNN/LSTM Models. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2025, 49, 259–286. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Siddique, M.J.; Ahmed, S.M. Machine and Deep Learning-Based Comparative Analysis Using Hybrid Approaches for Intrusion Detection System. In Proceedings of the ICACS, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M. Research and Application of Firewall Log and Intrusion Detection Log Data Visualization System. IET Softw. 7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Hao, Z.; Hu, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Chen, X. Network Traffic Analysis over Clustering-Based Collective Anomaly Detection. Comput. Netw. 2022, 205, 108760. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gao, S.; Liu, B. An Improved Density Peaks Clustering Algorithm Based on Grid Screening and Mutual Neighborhood Degree for Network Anomaly Detection. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1409. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [CrossRef]

- Joloudari, J.H.; Marefat, A.; Nematollahi, M.A.; Oyelere, S.S.; Hussain, S. Effective Class-Imbalance Learning Based on SMOTE and Convolutional Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4006. [CrossRef]

- Imrana, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Ali, L.; Noor, A.; Sarpong, K.; Abdullah, M.A. CNN-GRU-FF: A Double-Layer Feature Fusion-Based Network Intrusion Detection System Using Convolutional Neural Network and Gated Recurrent Units. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 3353–3370. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wu, S.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Z. Research on CNN-BiLSTM Network Traffic Anomaly Detection Model Based on MindSpore. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.21008.

- Sattar, S.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.I.; Akhmediyarova, A.; Mamyrbayev, O.; Kassymova, D.; Oralbekova, D.; Alimkulova, J. Anomaly Detection in Encrypted Network Traffic Using Self-Supervised Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26585. [CrossRef]

- Ji, I.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, M.J.; Park, W.J.; Jeon, S.H.; Seo, J.T. Artificial Intelligence-Based Anomaly Detection Technology over Encrypted Traffic: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 898. [CrossRef]

- Marfo, W.; Rico, E.A.; Tosh, D.K.; Moore, S.V. Network Anomaly Detection in Distributed Edge Computing Infrastructure. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05700. arXiv:2503.05700.

- Patel, J.; Reiner, J.; Stilwell, B.; Wahbeh, A.; Seetan, R. Leveraging K-Means Clustering and Z-Score for Anomaly Detection in Bitcoin Transactions. Informatics 2025, 12(2), 43. [CrossRef]

- Vanem, E.; Brandsæter, A. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Based on Clustering Methods and Sensor Data on a Marine Diesel Engine. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2021, 20(4), 217–234. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).