Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

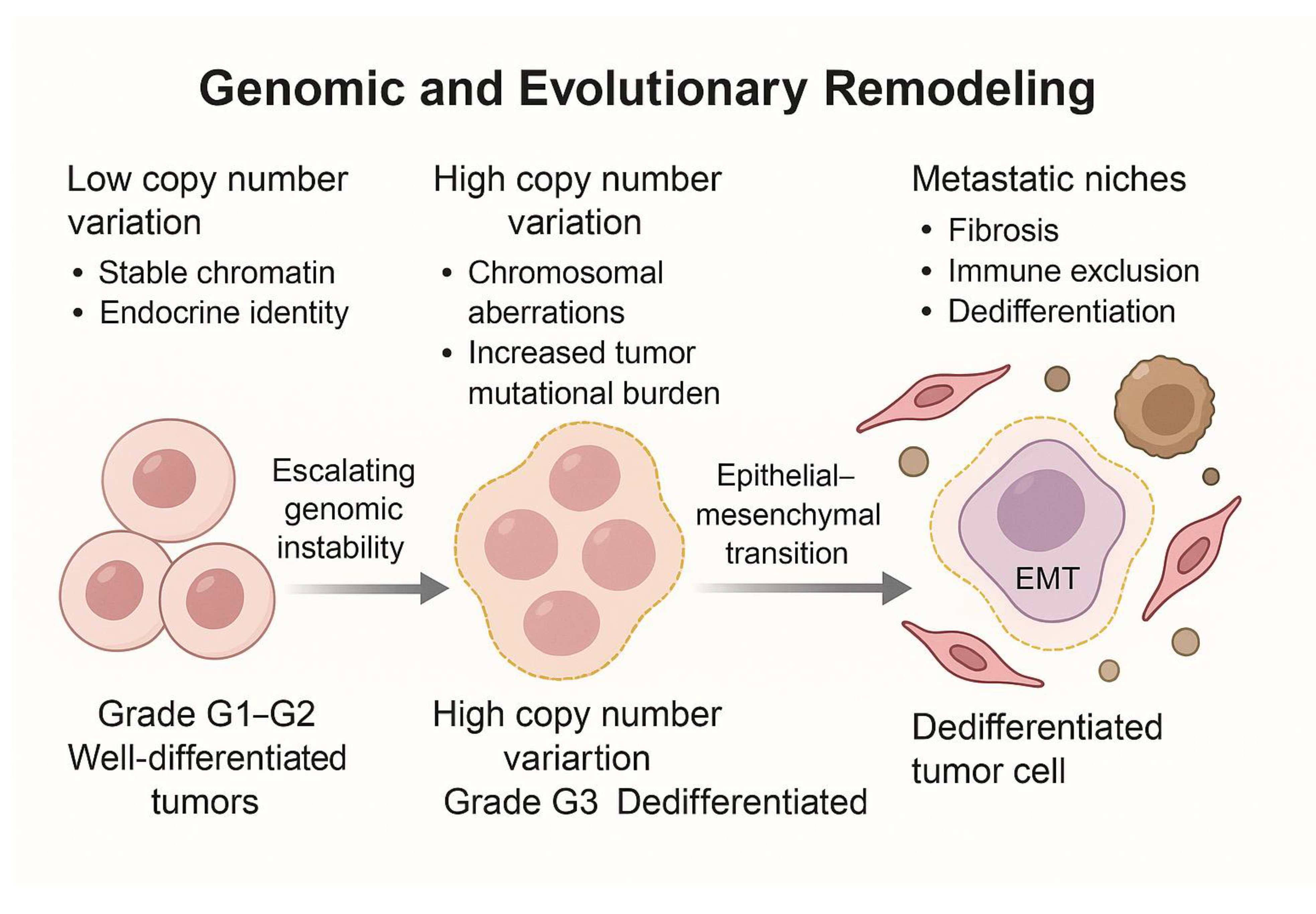

2. Genomic and Evolutionary Remodeling

2.1. Genomic Instability as a Diver of Dedifferentiation and Transcriptomic Plasticity

2.2. Clonal Evolution and the Pre-Configuration of Metastatic Niches

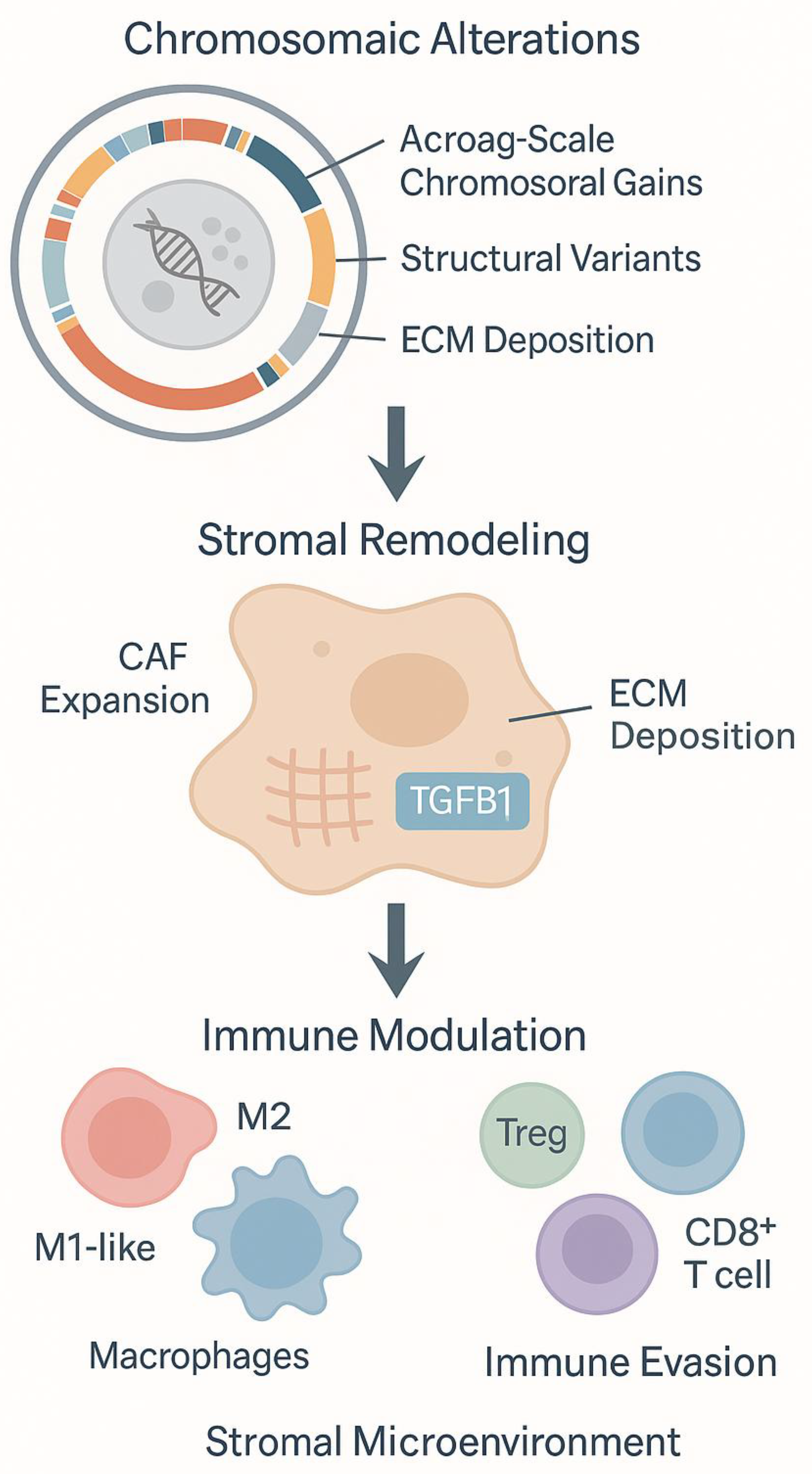

3.1. Integrated Omics Profiling of Tumor-Stroma Interactions

3.2. CAF-Driven Niches Promoting Dedifferentiation and Immune Exclusion

4. Immune Landscape and Functional States

4.1. Immune Phenotypes in PNET Progression

4.2. Spatial and Molecular Determinants of Immune Modulation

5. Translational Implications and Biomarker Discovery

6. Future Outlook and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reid, M.D., et al., Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: current concepts and controversies. Endocr Pathol, 2014. 25(1): p. 65-79.

- Lawrence, B., et al., The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 2011. 40(1): p. 1-18, vii. [CrossRef]

- Cives, M. and J.R. Strosberg, Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018. 68(6): p. 471-487.

- Simon, T., et al., DNA methylation reveals distinct cells of origin for pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Genome Med, 2022. 14(1): p. 24. [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.S., et al., ATRX, DAXX or MEN1 mutant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are a distinct alpha-cell signature subgroup. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 4158. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R., et al., Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE). Ann Oncol, 2010. 21(9): p. 1794-1803. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., et al., Recurrence in Resected Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. JAMA Oncol, 2018. 4(4): p. 583-585. [CrossRef]

- Inzani, F., G. Petrone, and G. Rindi, The New World Health Organization Classification for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 2018. 47(3): p. 463-470. [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal, I.D., et al., The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology, 2020. 76(2): p. 182-188. doi:10.1111/his.13975.

- Tang, L.H., et al., Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors with a Morphologically Apparent High-Grade Component: A Pathway Distinct from Poorly Differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res, 2016. 22(4): p. 1011-7. [CrossRef]

- Crona, J., et al., Multiple and Secondary Hormone Secretion in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016. 101(2): p. 445-52. [CrossRef]

- de Mestier, L., et al., Metachronous hormonal syndromes in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a case-series study. Ann Intern Med, 2015. 162(10): p. 682-9.

- Botling, J., et al., High-Grade Progression Confers Poor Survival in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology, 2020. 110(11-12): p. 891-898. [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E. and J.A. Joyce, The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell, 2023. 41(3): p. 374-403.

- Xiao, Y. and D. Yu, Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Ther, 2021. 221: p. 107753. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., et al., Turning cold tumors hot: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Trends Immunol, 2022. 43(7): p. 523-545. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., et al., Hot and cold tumors: Immunological features and the therapeutic strategies. MedComm (2020), 2023. 4(5): p. e343. [CrossRef]

- Baghban, R., et al., Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun Signal, 2020. 18(1): p. 59. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, A., et al., Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature, 2017. 543(7643): p. 65-71.

- Jiao, Y., et al., DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science, 2011. 331(6021): p. 1199-203. [CrossRef]

- Hong, X., et al., Whole-genome sequencing reveals distinct genetic bases for insulinomas and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: leading to a new classification system. Gut, 2020. 69(5): p. 877-887. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., et al., Targeted deep sequencing reveals the genetic heterogeneity in well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with liver metastasis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2023. 12(3): p. 302-313. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T., M.A. Keaton, and A. Dutta, Genomic instability in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2013. 5(3): p. a012914.

- Ciriello, G., et al., Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat Genet, 2013. 45(10): p. 1127-33. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., et al., Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals spatiotemporal heterogeneity and malignant progression in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Int J Biol Sci, 2021. 17(14): p. 3760-3775. [CrossRef]

- Sadanandam, A., et al., A Cross-Species Analysis in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Reveals Molecular Subtypes with Distinctive Clinical, Metastatic, Developmental, and Metabolic Characteristics. Cancer Discov, 2015. 5(12): p. 1296-313.

- Miki, M., et al., CLEC3A, MMP7, and LCN2 as novel markers for predicting recurrence in resected G1 and G2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Med, 2019. 8(8): p. 3748-3760. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z., et al., Single-cell sequencing reveals the heterogeneity of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors under genomic instability and histological grading. iScience, 2024. 27(9): p. 110836. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., et al., Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression? Cell Death Dis, 2023. 14(9): p. 587. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., X. Gao, and X. Wang, Identification of tumor mutation burden-associated molecular and clinical features in cancer by analyzing multi-omics data. Front Immunol, 2023. 14: p. 1090838. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A., et al., Proteogenomic characterization of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors uncovers hypoxia and immune signatures in clinically aggressive subtypes. iScience, 2024. 27(8): p. 110544. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., et al., Cell Cycle Protein Expression in Neuroendocrine Tumors: Association of CDK4/CDK6, CCND1, and Phosphorylated Retinoblastoma Protein With Proliferative Index. Pancreas, 2017. 46(10): p. 1347-1353.

- April-Monn, S.L., et al., EZH2 Inhibition as New Epigenetic Treatment Option for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (PanNENs). Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(19). [CrossRef]

- Niedra, H., et al., Tumor and alpha-SMA-expressing stromal cells in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors have a distinct RNA profile depending on tumor grade. Mol Oncol, 2025. 19(3): p. 659-681. [CrossRef]

- Gisder, D.M., et al., DAXX, ATRX, and MSI in PanNET and Their Metastases: Correlation with Histopathological Data and Prognosis. Pathobiology, 2023. 90(2): p. 71-80. [CrossRef]

- Heaphy, C.M. and A.D. Singhi, Reprint of: The Diagnostic and Prognostic Utility of Incorporating DAXX, ATRX, and Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) to the Evaluation of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PanNETs). Hum Pathol, 2023. 132: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.T., et al., TCF4 induces enzalutamide resistance via neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer. PLoS One, 2019. 14(9): p. e0213488. [CrossRef]

- Forrest, M.P., et al., The emerging roles of TCF4 in disease and development. Trends Mol Med, 2014. 20(6): p. 322-31. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, K., G. Song, and G. Ouyang, Role of hypoxia in the hallmarks of human cancer. J Cell Biochem, 2009. 107(6): p. 1053-62. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z., et al., The stromal microenvironment endows pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with spatially specific invasive and metastatic phenotypes. Cancer Lett, 2024. 588: p. 216769. [CrossRef]

- Avsievich, E., et al., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: The Case Report of a Patient with Germline FANCD2 Mutation and Tumor Analysis Using Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. J Clin Med, 2024. 13(24). [CrossRef]

- Pilati, C., et al., Mutational signature analysis identifies MUTYH deficiency in colorectal cancers and adrenocortical carcinomas. J Pathol, 2017. 242(1): p. 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H., et al., Deficiency of Wnt10a causes female infertility via the beta-catenin/Cyp19a1 pathway in mice. Int J Med Sci, 2022. 19(4): p. 701-710. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H., et al., Deletion of Wnt10a Is Implicated in Hippocampal Neurodegeneration in Mice. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Li, P., et al., Clinical significance and biological role of Wnt10a in ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett, 2017. 14(6): p. 6611-6617. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., et al., FANCD2 and RAD51 recombinase directly inhibit DNA2 nuclease at stalled replication forks and FANCD2 acts as a novel RAD51 mediator in strand exchange to promote genome stability. Nucleic Acids Res, 2023. 51(17): p. 9144-9165. [CrossRef]

- Backman, S., et al., The evolutionary history of metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours reveals a therapy driven route to high-grade transformation. J Pathol, 2024. 264(4): p. 357-370. [CrossRef]

- Ji, S., et al., Proteogenomic characterization of non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors unravels clinically relevant subgroups. Cancer Cell, 2025. 43(4): p. 776-796 e14. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.P., et al., Identification of EMT signaling cross-talk and gene regulatory networks by single-cell RNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2021. 118(19). [CrossRef]

- Young, K., et al., Immune landscape, evolution, hypoxia-mediated viral mimicry pathways and therapeutic potential in molecular subtypes of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Gut, 2021. 70(10): p. 1904-1913. [CrossRef]

- Olson, P., et al., MicroRNA dynamics in the stages of tumorigenesis correlate with hallmark capabilities of cancer. Genes Dev, 2009. 23(18): p. 2152-65. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.C., et al., Proteotranscriptomic classification and characterization of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Cell Rep, 2021. 37(2): p. 109817. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).