Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Masonry Materials

2.1. Brick

- Elastic modulus, Eb = 11850 MPa

- Shear modulus, Gb = 4740 MPa

- Poisson’s ratio, μb=0.113

2.2. Mortar

-

Series KRO-1:

- Mortar strength, fm=10.9MPa

- Elastic modulus, Em=10580 MPa

- Shear modulus, Gm= 4232 MPa

- Poisson’s ratio, μm=0.17.

-

Series KRO-2:

- Mortar strength, fm=7.9 MPa

- Elastic modulus, Em=9210 MPa

- Shear modulus, Gm= 3684 MPa

- Poisson’s ratio, μm=0.19.

-

Series KRO-3:

- Mortar strength, fm=3.1 MPa

- Elastic modulus, Em=4600 MPa

- Shear modulus, Gm= 1840 MPa

- Poisson’s ratio, μm=0.23.

3. Research Methodology

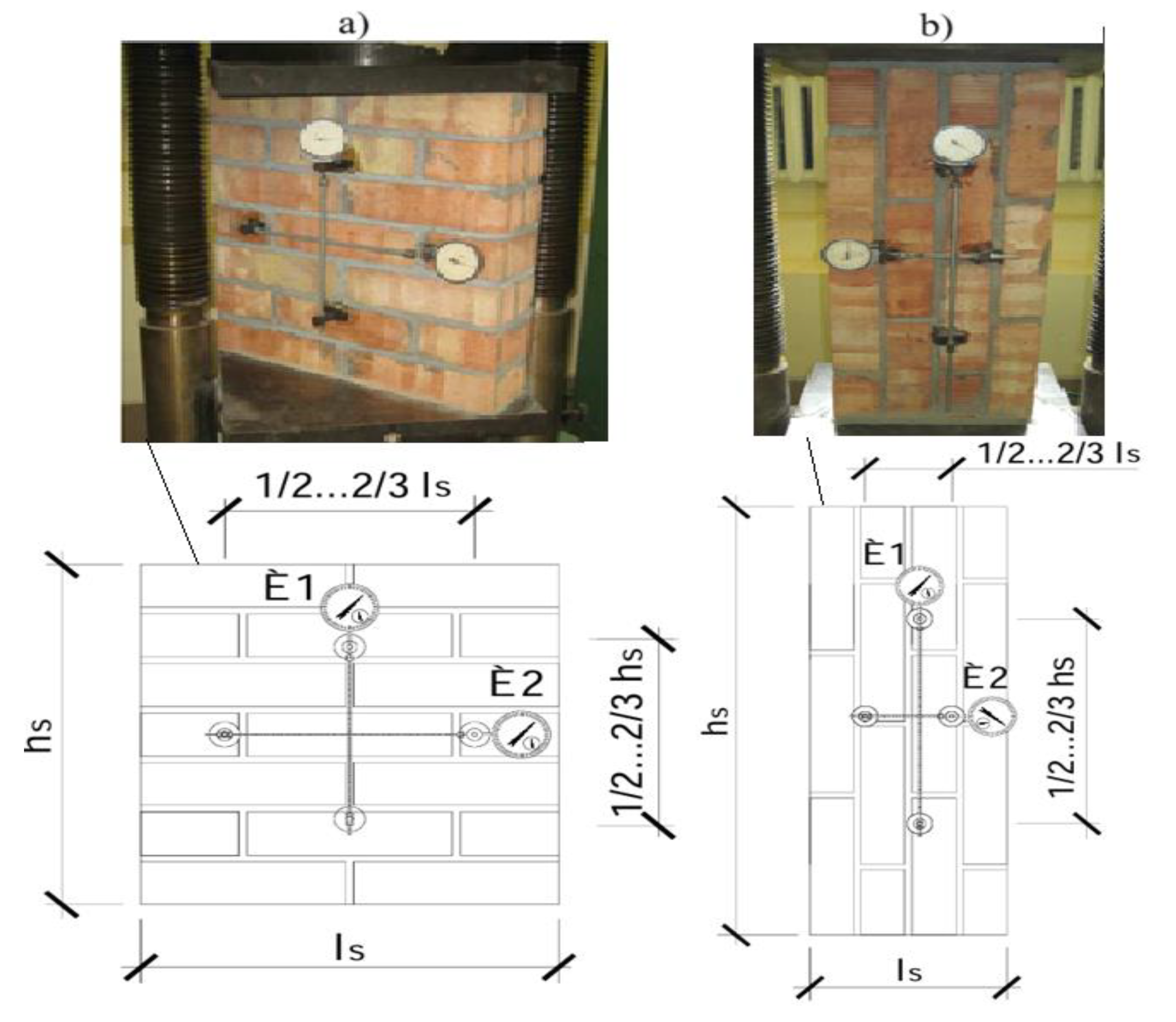

Masonry Specimens

- a.

- Experimental Investigations

- b.

- Analytical method for determining the stiffness matrix of anisotropic brick masonry.

- c.

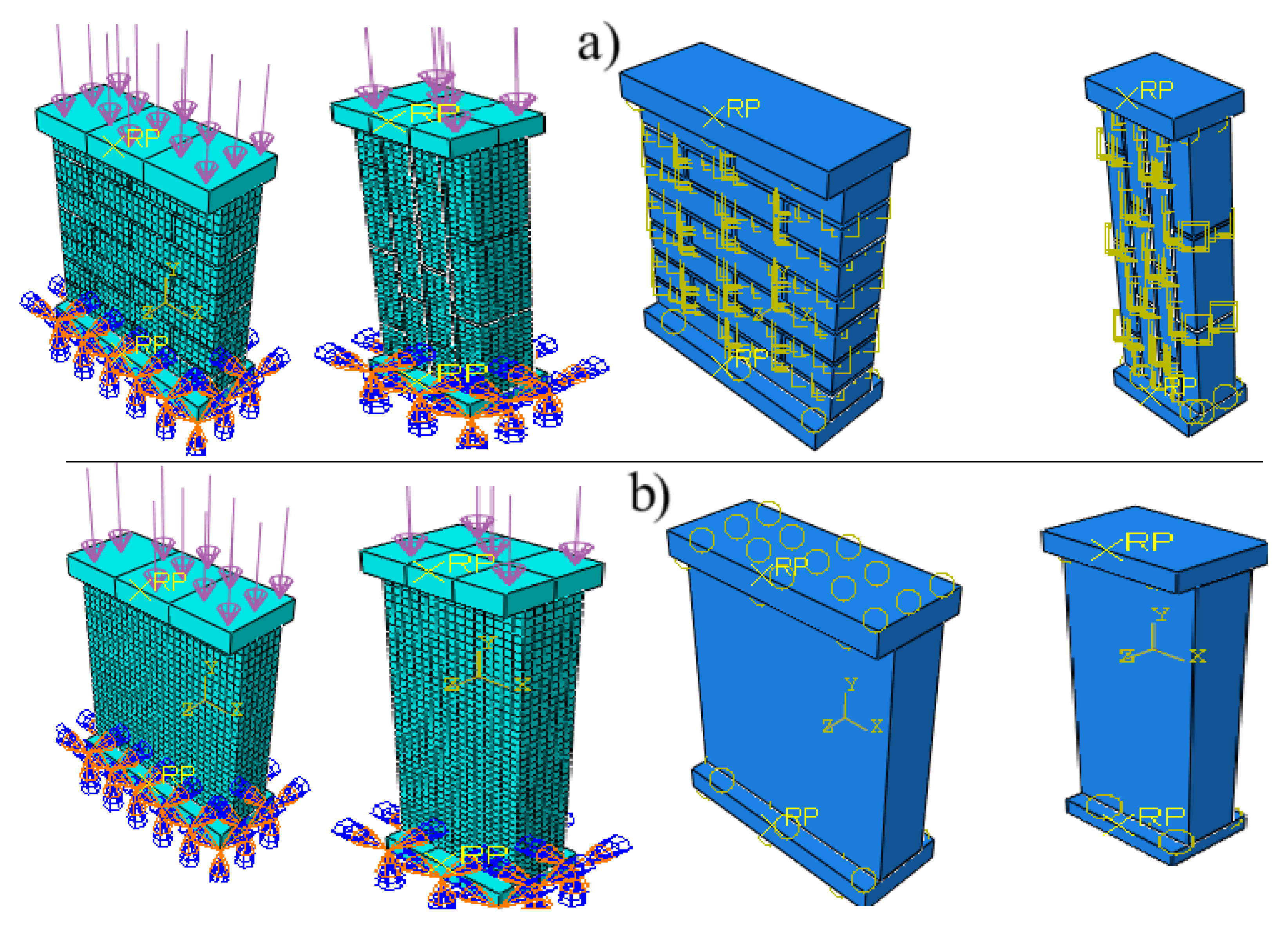

- Numerical Modeling

- Macromodel EXP – A homogenized model based on experimentally measured elastic properties (Young’s moduli Ex, Ey, Poisson’s ratios μxy, μyx and shear modulus Gxy) from reference [20].

- Macromodel Dij – A refined model incorporating the asymmetric stiffness matrix (calculated via Eqs. 8–9), where D12≠D21.

| Series | contact stiffness in Abaqus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb (MPa) | Em (MPa) | Gb (MPa) | Gm (MPa) |

(MPa)/мм |

(MPa)/мм |

|||

| KRO -1 | 11850 | 10580 | 4740 | 4232 | 0.113 | 0.17 | 987.2 | 394.9 |

| КRО-2 | 9210 | 3684 | 0.19 | 413.4 | 165.4 | |||

| KRO -2 | 4600 | 1840 | 0.23 | 75.2 | 30.1 | |||

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

- Model Validation:

- 2.

-

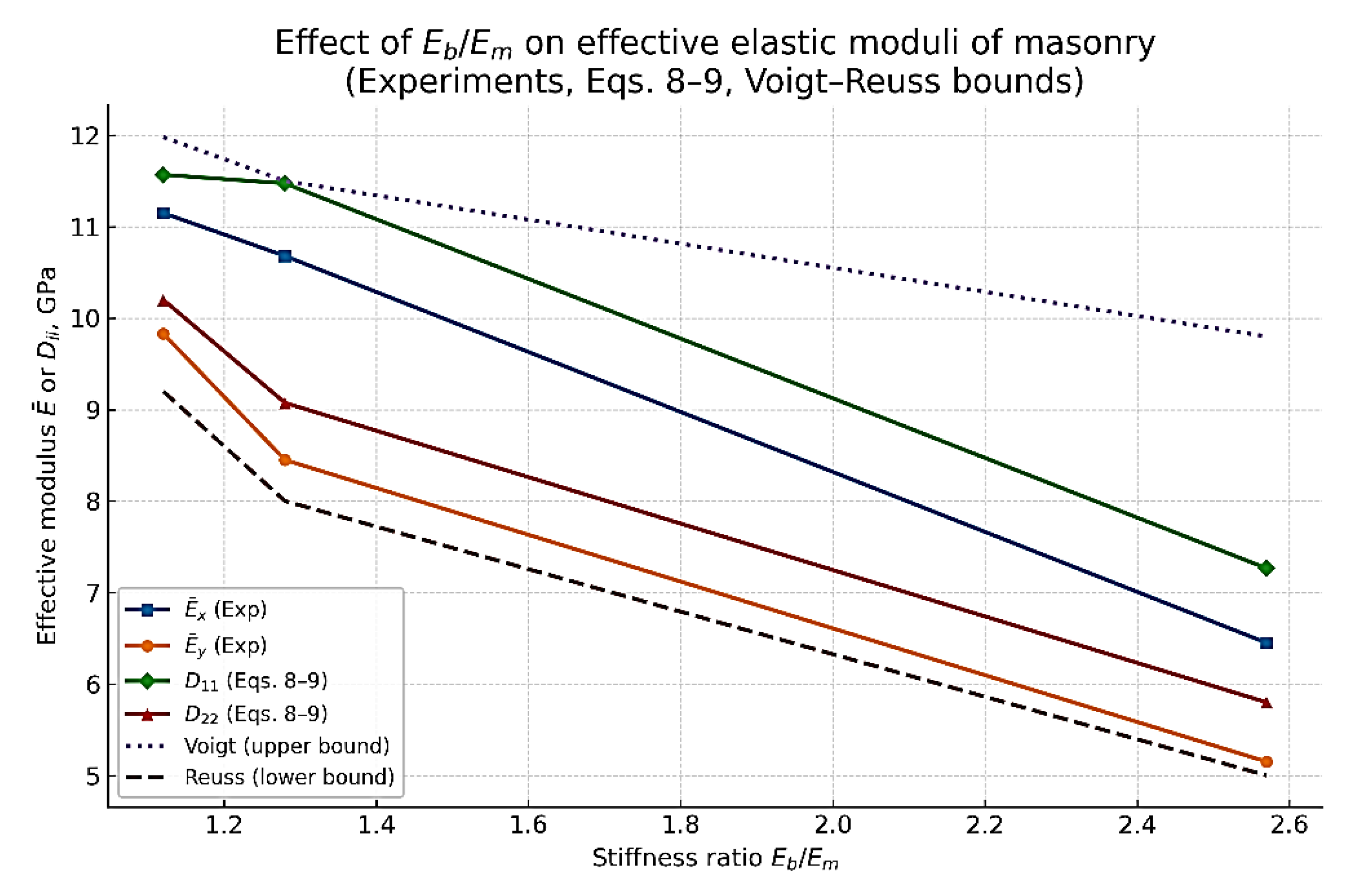

Anisotropy Trends:

- Maximum anisotropy occurs in KPO-2 (Ex/Ey=1.264)

- Minimum anisotropy is observed in KPO-1 (Ex/Ey=1.134)

- 3.

- Unexpected Stiffness Behavior:

- k quantifies the degree of stiffness anisotropy between orthogonal directions (x - along mortar joints, y - across joints), with k=1 indicating isotropic material (Eₓ=Ey) and k≠1 confirming anisotropy;

- m reflects the combined influence of shear stiffness (Gₓᵧ) and transverse deformations on anisotropy, where m=0 for isotropic materials and m>0 for masonry due to low shear stiffness of mortar joints;

- n serves as a comprehensive parameter combining longitudinal and shear anisotropy effects, with n=2 for isotropic cases and n≠2 demonstrating anisotropy.

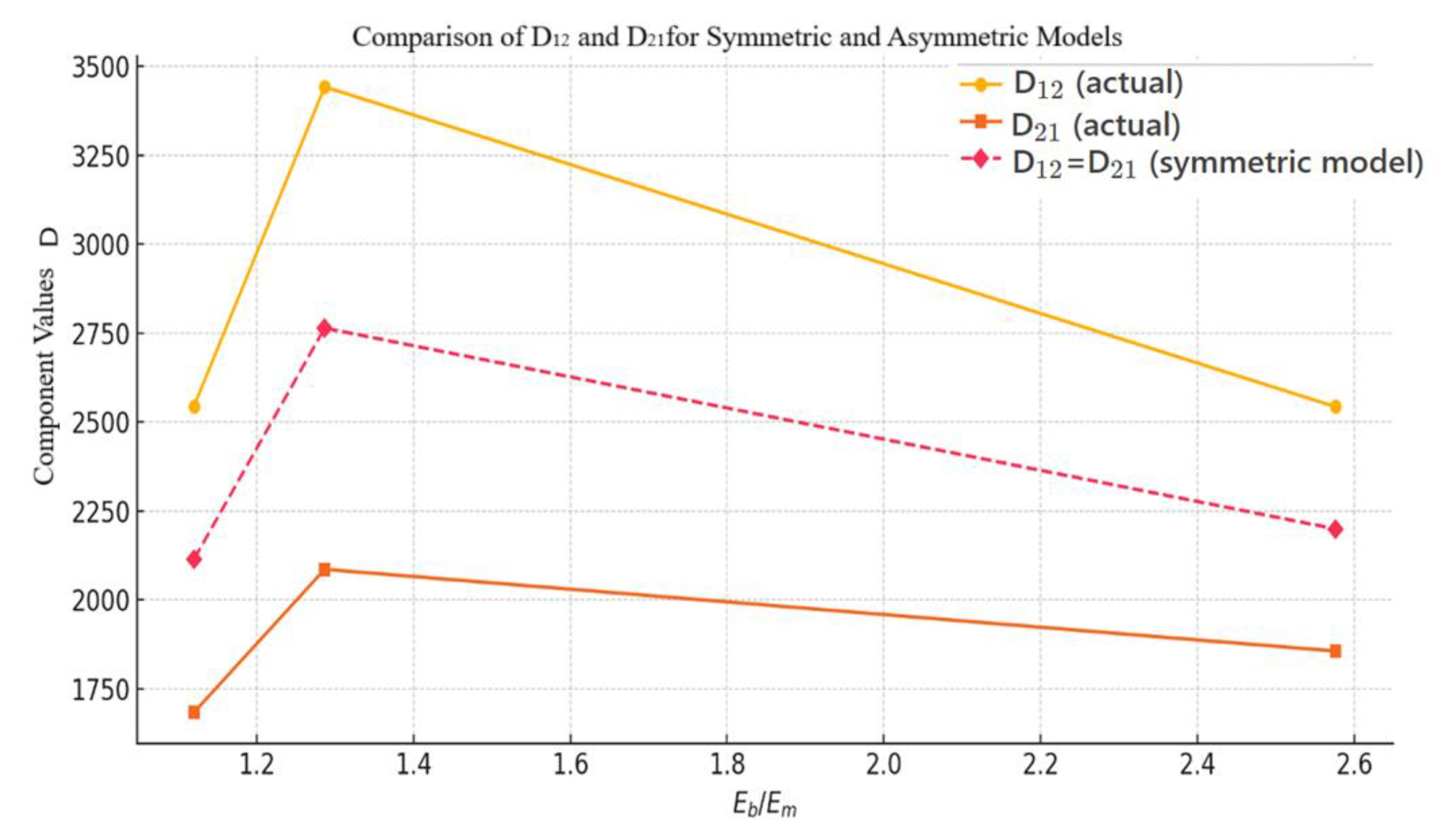

- Effect of stiffness matrix asymmetry:

- 2.

- Critical case for KRO-2 series:

- 3.

- Theoretical implications:

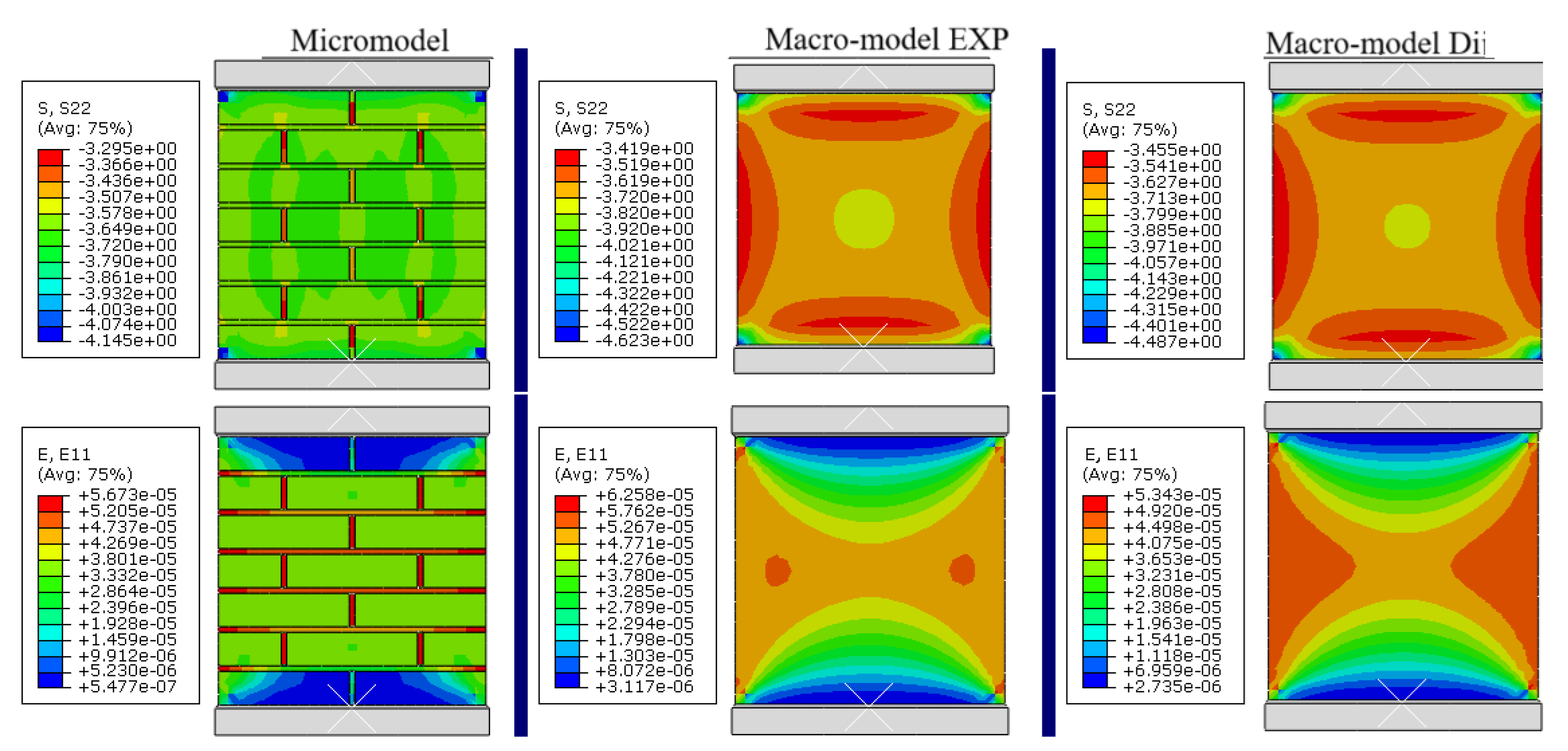

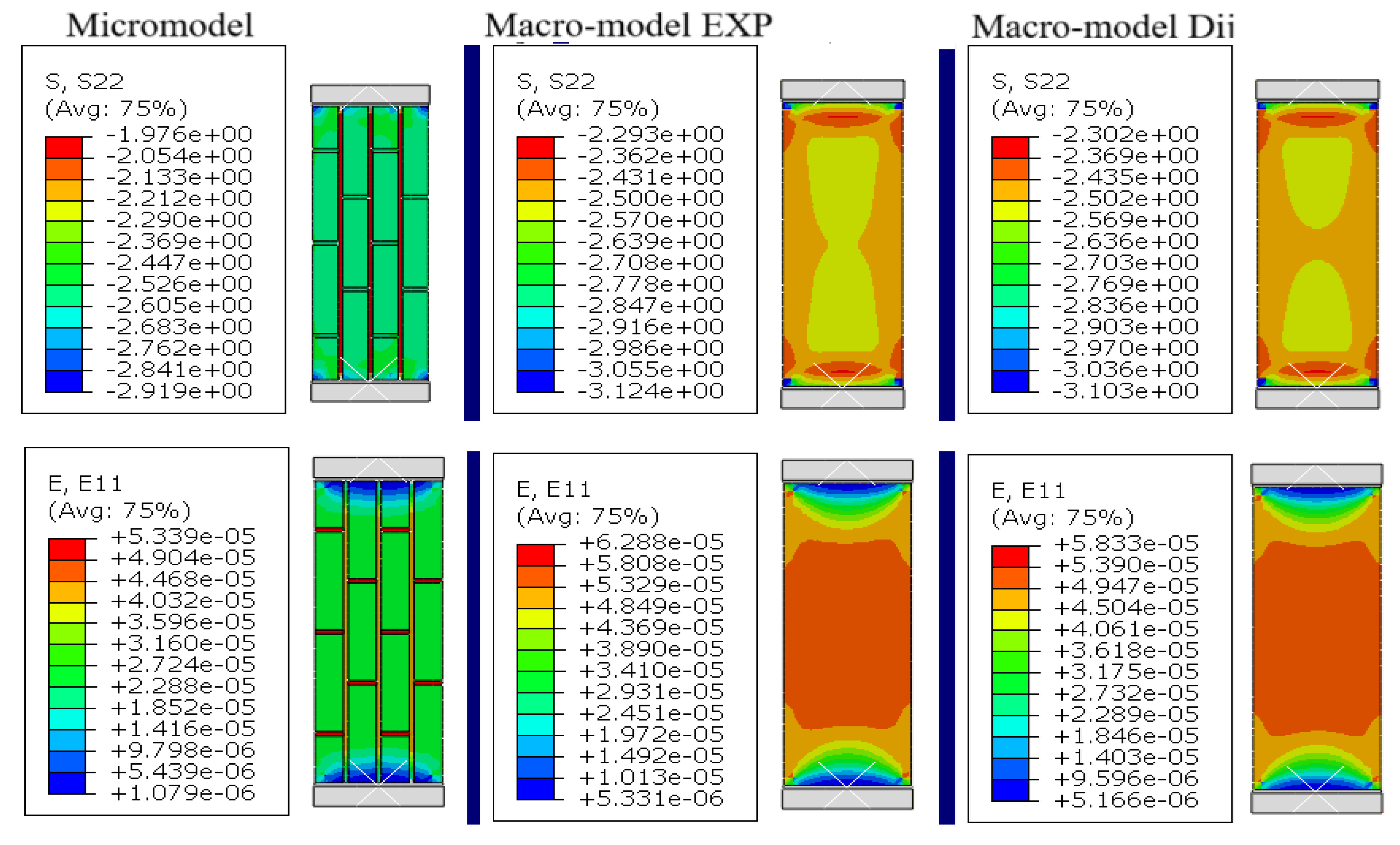

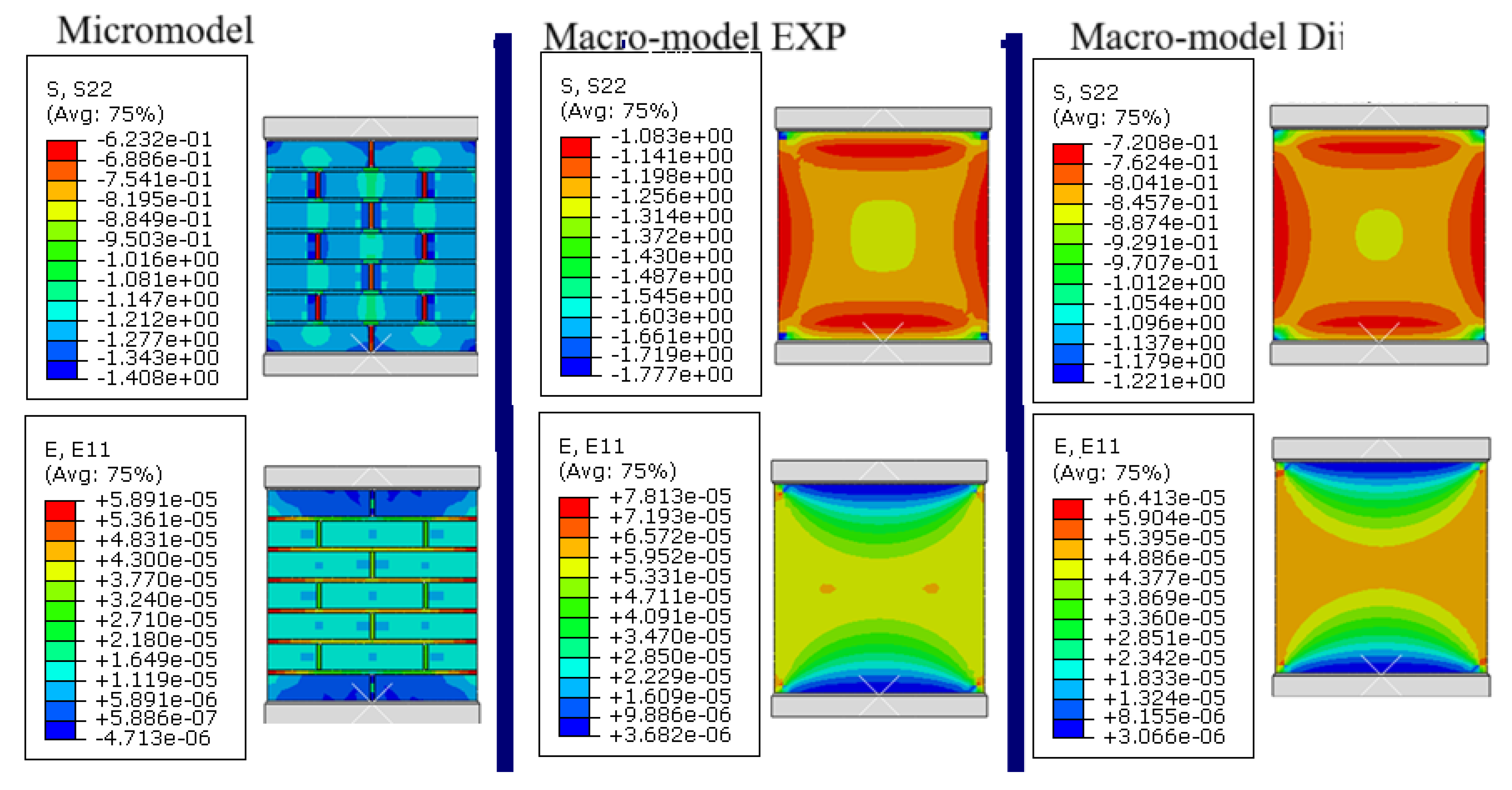

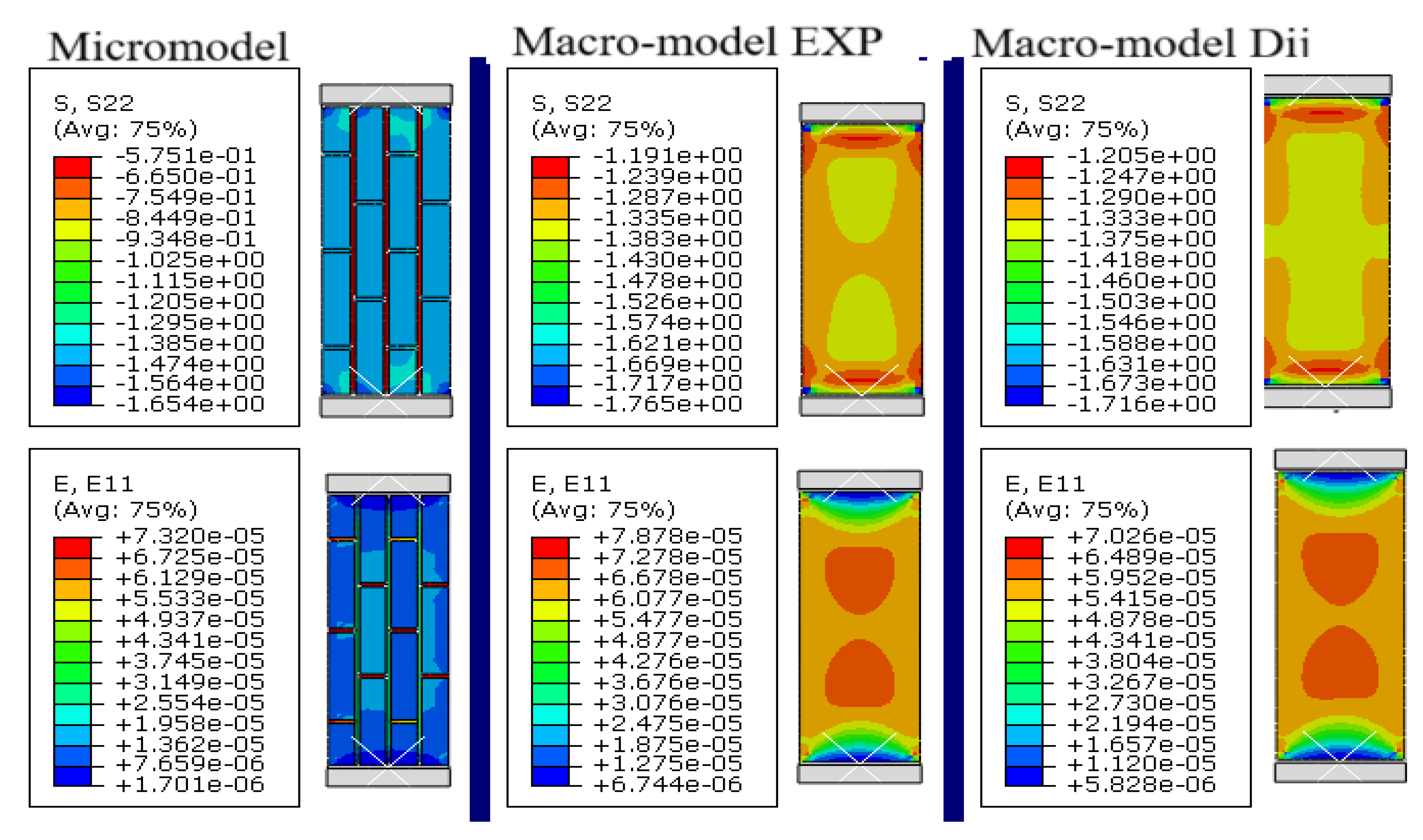

- Figure 5a (loading perpendicular to joints, KRO-2): A uniform distribution of vertical stresses (σy) is observed, with localized concentrations (up to 15%) in edge zones, while horizontal strains (εx) exhibit elevated values near boundaries (EXP errors: up to 29%, D-model: up to 18.3%), confirming the influence of edge effects, partially mitigated by the orthotropic model.

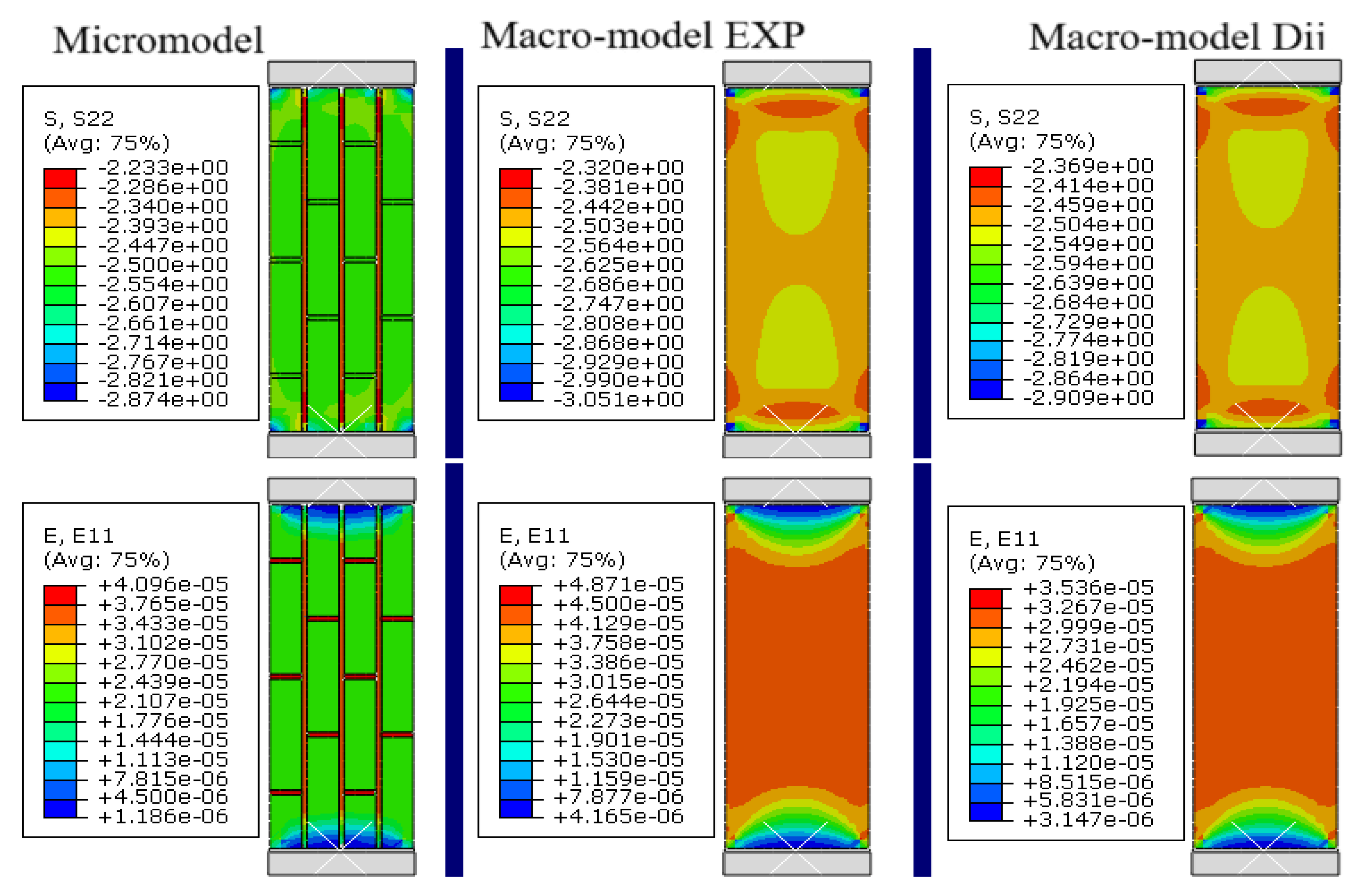

- Figure 5b (loading parallel to joints, KRO-2): Stress distribution is less uniform, with pronounced concentrations near vertical joints (σy errors up to 15.1%), and strains (εx) in edge zones show significant deviations (EXP errors: up to 35.7%, D-model: up to 28.6%), highlighting the critical role of brick-mortar contact micromechanics and the need for larger RVEs to minimize inaccuracies.

4.2. Discussion

- (a)

- Material and geometric constraints: The model requires validation for reinforced masonry, thin-bed joints, or alternative brickwork patterns (e.g., English bond).

- (b)

- Loading scenarios: Nonlinear effects (cracking, creep) and multidirectional stresses were not considered.

- (c)

- Scale effects: The RVE size (4 courses for vertical loading) may not capture behavior in full-scale structures under complex boundary conditions.

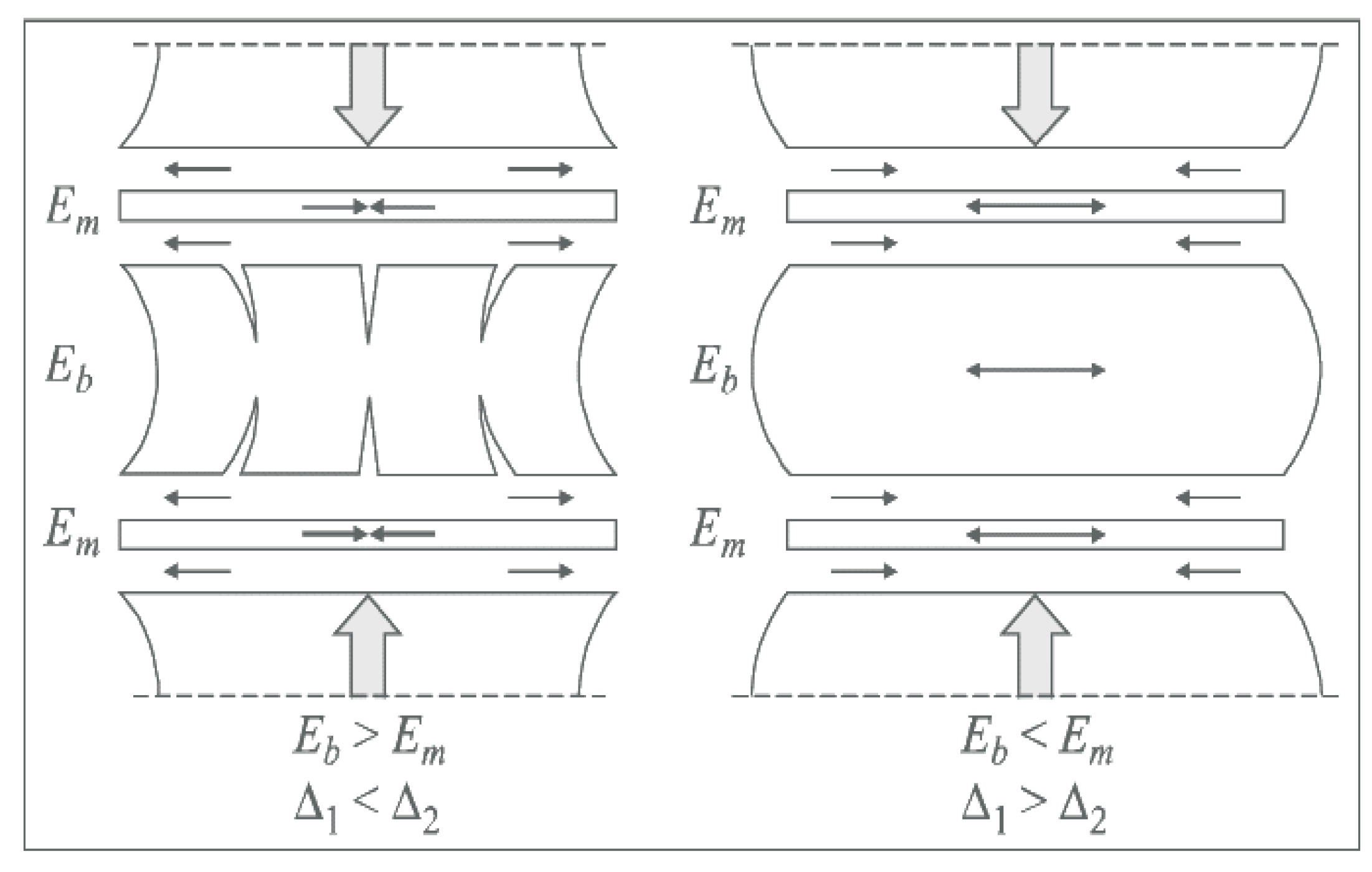

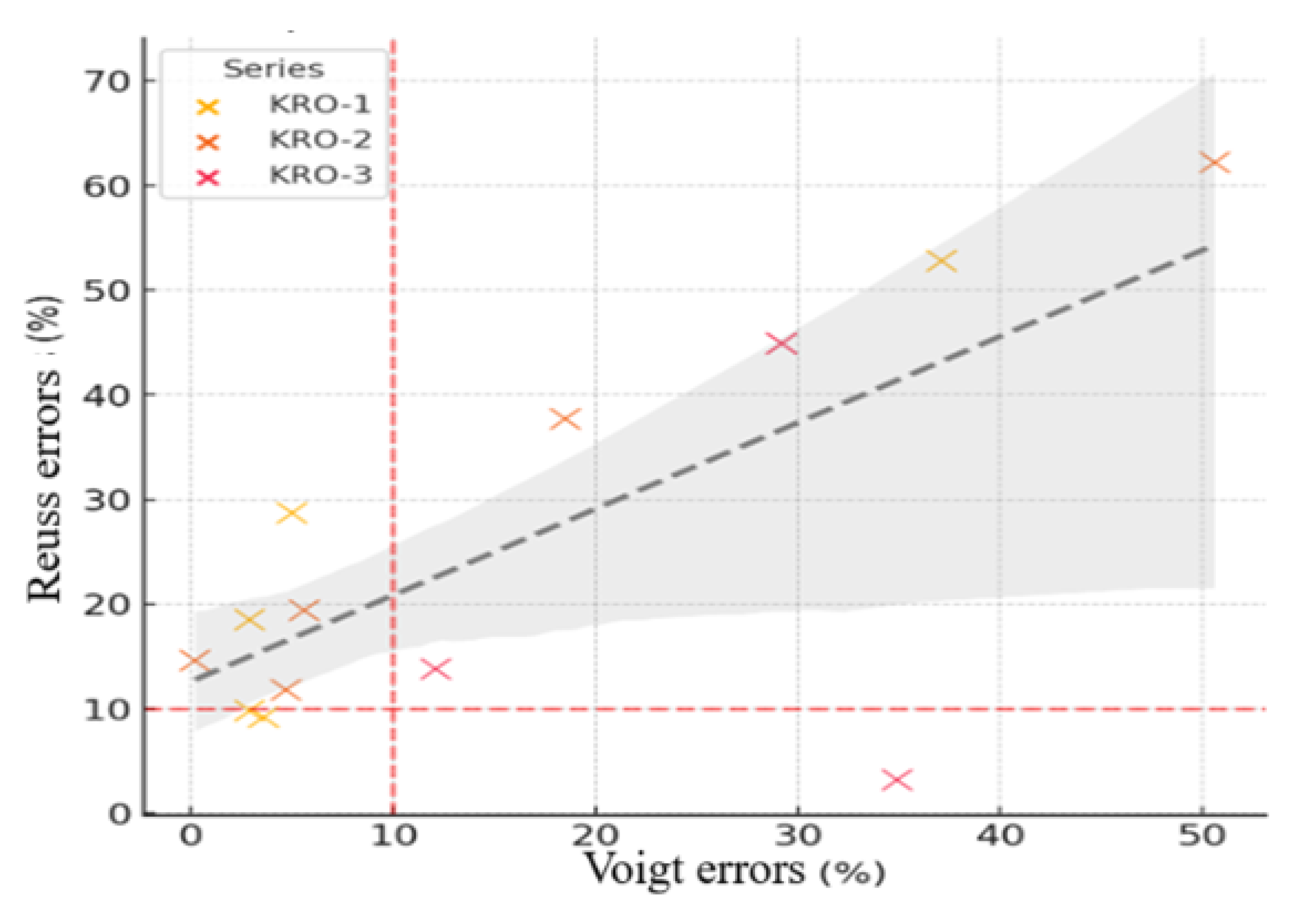

5. Comparison of Voigt and Reuss Methods for Masonry Stiffness Assessment Considering RVE

5.1. RVE Determination via Indicator Zones

- (a)

- Y-axis loading (vertical, perpendicular to joints): RVE encompasses 4 brick courses (indicator zones)

- (b)

- X-axis loading (horizontal, parallel to joints): RVE comprises 2 brick rows (indicator zones)

5.2. Stiffness Evaluation Methods

- Voigt Method: Assumes uniform strain across components, computing stiffness as volume-weighted average:

- Y-axis (perpendicular to joints): = 86.7%, = 13.3%

- X-axis (parallel to joints): = 86.7%, = 13.3%

- 2.

- Method Reuss:

6. Conclusions

- a)

- Material anisotropy driven by brick-mortar stiffness disparity

- b)

- Edge effects, particularly pronounced in low-strength mortar specimens

- c)

- Elastic property asymmetry, necessitating classical orthotropic model modifications

- d)

- Real service conditions, including loading direction and masonry component interactions

- Extension to reinforced masonry and non-standard geometries.

- Incorporation of nonlinear material models for damage analysis.

- Experimental validation under shear and combined loading.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

References

- Pindera, M.-J.; Khatam, H.; Drago, A.S.; Bansal, Y. Micromechanics of spatially uniform heterogeneous media: A critical review and emerging approaches. Composites Part B Engineering 2009, 40, 349–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrister, O.I.; Okoli, C.E.E.; Shanbhag, S. Micromechanics predictions for two-phased nanocomposites and three-phased multiscale composites: A review. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2015, 34, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buryachenko, V.A. Multiparticle effective field and related methods in micromechanics of composite materials. Applied Mechanics Reviews 2001, 54, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.; Hiremath, S.R.; Mahapatra, D.R. A review of micromechanics-based models for effective elastic properties of reinforced polymer matrix composites. Composite Structures 2018, 204, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. A review of analytical micromechanics models on composite elastoplastic behaviour. Procedia Engineering 2017, 173, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.M. A critical evaluation for a class of micromechanics models. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 1990, 38, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzel, S.D.; Bonhin, E.P.; Guimarães, N.M.; Guidi, E.S. Application of the finite element method in the analysis of composite materials: A review. Polymers 2020, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, S.; et al. Generation of 3D representative volume elements for heterogeneous materials: A review. Progress in Materials Science 2018, 96, 322–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.O.; Lee, W.J.; Cho, D.H.; et al. Finite element analysis of compressive behavior of hybrid short fiber/particle/mg metal matrix composites using RVE model. Metals and Materials International 2015, 21, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.V.; Shedbale, A.S.; Mishra, B.K. Material property evaluation of particle reinforced composites using finite element approach. Journal of Composite Materials 2016, 50, 2757–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V. Integrated structures and materials design. Materials and Structures 2007, 40, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellippallil, A.B.; Allen, J.K.; Gautham, B.P.; Singh, A.K.; Mistree, F. Integrated design of materials, products, and associated manufacturing processes. In Architecting Robust Co-Design of Materials, Products, and Manufacturing Processes; Springer: Cham, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reznikov, B.S.; Nikitenko, A.F.; Kucherenko, I.V. Prediction of macroscopic properties of structurally heterogeneous media. Part 1. News of Higher Educational Institutions Construction 2008, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, R. Introduction to the Mechanics of Composites; Mir: Moscow, 1982; 334p. [Google Scholar]

- Shermergor, T.D. Theory of Elasticity of Microheterogeneous Media; Nauka: Moscow, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Polilov, A.N. Etude Problems of Composite Mechanics: Textbook; Educational and Scientific Testing Complex for Technical Universities of Moscow: Moscow, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimenko, V.N.; Olein, I.P. Theoretical Foundations of Methods for Calculating the Strength of Structural Elements Made of Composites; Publishing House of the Novosibirsk State Technical University: Novosibirsk, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nemirovsky, Y.V.; Reznikov, B.S. Strength of Structural Elements Made of Composite Materials; Nauka. Sib. Department: Novosibirsk, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T.; Dzako, M. Fracture Mechanics of Composite Materials; Mir: Moscow, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Galalyuk, A.V. Anisotropy of Elastic and Strength Characteristics of Ceramic Brick Masonry under Axial Uniaxial Compression: Dissertation. Brest State Technical University, 2024; 140p.

- Adishchev, V.V.; Shakarneh, O.M.D. Homogenization method for determining the matrix of effective stiffness coefficients of masonry. News of Higher Educational Institutions Construction 2025, 4, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Adishchev, V.V.; Shakarneh, O.M.D. Identification of effective stiffness characteristics of masonry based on comparative analysis of numerical and physical experiments. News of Higher Educational Institutions Construction 2024, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galalyuk, A.V.; Demchuk, I.E. Mathematical modeling of masonry samples under compression. Problems of Modern Concrete and Reinforced Concrete 2012, 4, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Shakarneh, O.M.D. Homogenization method for determining the matrix of effective stiffness coefficients of reinforcement masonry wall. Proceedings of the Novosibirsk State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakarneh, O.M.D.; Adishchev, V.V. Numerical modeling of the stress-strain state in masonry reinforced with reinforcing meshes. News of Higher Educational Institutions Construction 2023, 3, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekhnitsky, S.G. Theory of Elasticity of an Anisotropic Body; Nauka: Moscow, 1977; 467p. [Google Scholar]

- Derkach, V.N. Anisotropy of deformation properties of masonry. Scientific and Technical Bulletin of SPbSPU Science and Education 2011, 1, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1052-1:1998; Methods of Test for Masonry – Part 1: Determination of Compressive Strength. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels.

- Lourenço, P.B. Computational Strategies for Masonry Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanooni-bagha, M.; Tarvirdi Yaghbasti, M.; Ranjbar, M.R. Determination of Homogeneous Stiffness Matrix for Masonry Structure by means of Homogenizing Theorem. Journal of Materials and Environment al Science 2016, 7, 1773–1790. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanooni-bagha, M.; Tarvirdi Yaghbasti, M.; Ranjbar, M.R. Determination of Homogeneous Stiffness Matrix for Masonry Structure by means of Homogenizing Theorem. Journal of Structural Engineering 2021, 147, 04021045. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, L.; et al. Machine Learning-Assisted Homogenization of Masonry Walls Under Seismic Loads. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 472, 111648. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, A.; Sab, K. A New Homogenization Approach for Periodic Masonry Based on Strain Energy Equivalence. Engineering Structures 2022, 250, 113422. [Google Scholar]

| Series | Experimental values from work [20] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb/Em | Ex (MPa) | Ey (MPa) | GXY (MPa) | Ex / Ey | |||

| KRO -1 | 1.12 | 11150 | 9830 | 0.165 | 0.22 | 4786.5 | 1.134 |

| КRО-2 | 1.28 | 10680 | 8450 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 4341.5 | 1.264 |

| KRO -2 | 2.57 | 6450 | 5150 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 2443.2 | 1.252 |

| Series | Results of calculation of the stiffness matrix Dij | ||||||

| Eb/Em | D11 (MPa) | D12 (MPa) | D21 (MPa) | D22 (МПа) | D33 (MPa) | D₁₁/D₂₂ | |

| KRO -1 | 1.12 | 11568.3 | 2545.0 | 1684.2 | 10201.4 | 4786.5 | 1.134 |

| КRО-2 | 1.28 | 11473.7 | 3442.1 | 2085.9 | 9074.1 | 4341.5 | 1.264 |

| KRO -2 | 2.57 | 7264.9 | 2542.8 | 1856.1 | 5799.5 | 2443.2 | 1.253 |

| Series | Accounting for Symmetry in Anisotropy Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | ||||

| KRO -1 | 2114.6 | 1.065 | 2 | 2.03 |

| КRО-2 | 2764 | 1.126 | 2 | 2.06 |

| KRO -3 | 2199.45 | 1.118 | 2 | 2.06 |

| Series | Accounting for an asymmetric in Anisotropy Coefficients | |||

| KRO -1 | 1.51 | 1.61 | 1.945 | 2.27 |

| KRO -2 | 1.65 | 1.86 | 1.93 | 2.38 |

| KRO -3 | 1.37 | 1.53 | 1.97 | 2.24 |

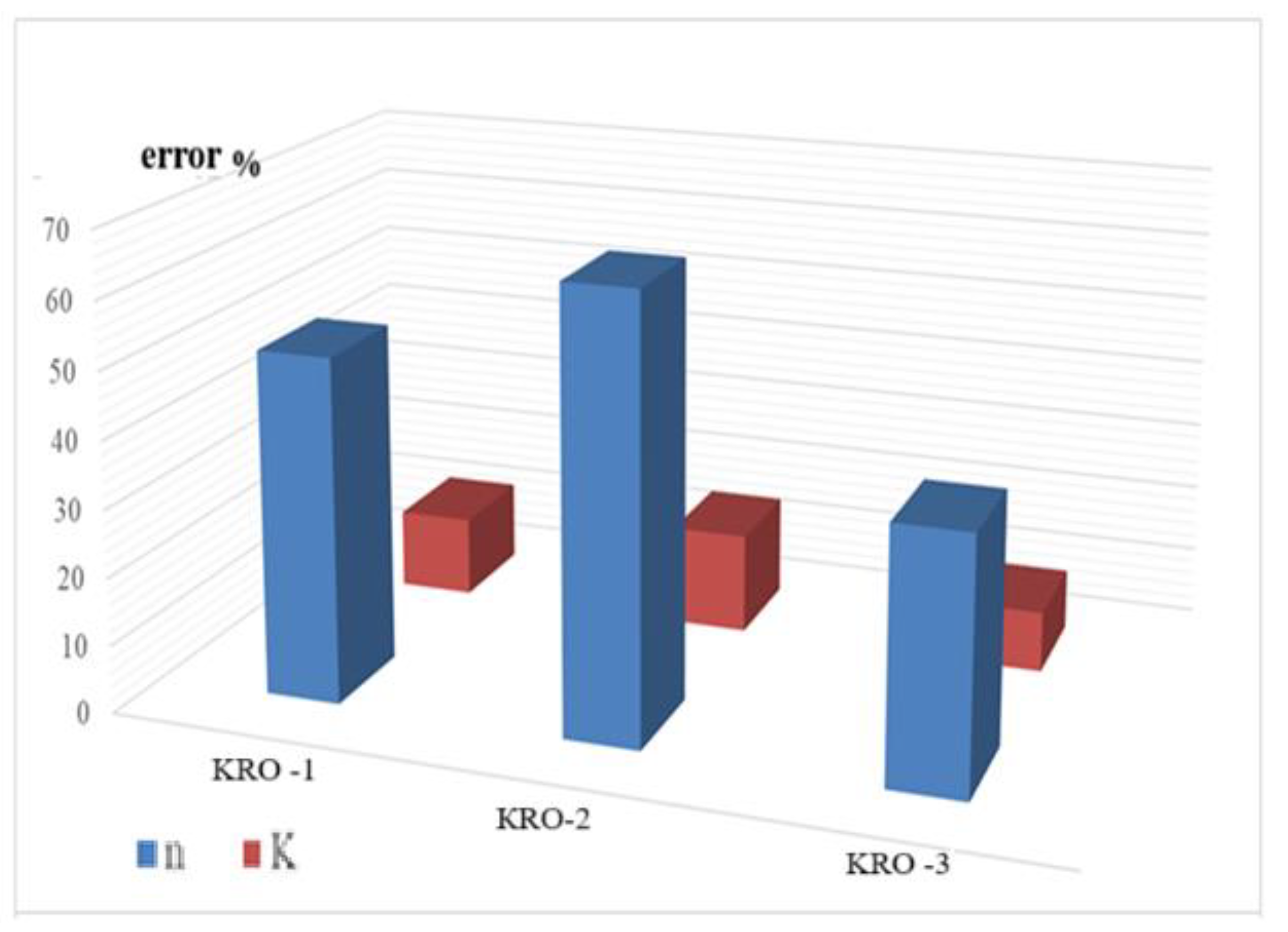

| Series | Parameters | D12 ≠ D21 | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRO -1 | 1.065 | 1.61 | 51% | |

| 2.03 | 2.27 | 12% | ||

| KRO -2 | 1.126 | 1.86 | 65% | |

| 2.06 | 2.38 | 15% | ||

| KRO -3 | 1.118 | 1.53 | 37% | |

| 2.06 | 2.24 | 9% |

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 2 | -3.36 | -3.51 | 4.46 | -3.54 | 5.36 |

| 6 | -3.64 | -3.92 | 7.69 | -3.88 | 6.59 |

| 10 | -3.93 | -4.32 | 9.92 | -4.22 | 7.38 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D (E11) | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000052 | 0.000057 | 9.62 | 0.000049 | 5.77 |

| 6 | 0.000033 | 0.000037 | 12.12 | 0.000032 | 3.03 |

| 10 | 0.000014 | 0.000017 | 21.43 | 0.000015 | 7.14 |

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | -2.28 | -2.38 | 4.39 | -2.41 | 5.70 |

| 6 | -2.50 | -2.62 | 4.80 | -2.19 | 12.40 |

| 10 | -2.71 | -2.86 | 5.54 | -2.77 | 2.21 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D (E11) | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000037 | 0.000045 | 21.62 | 0.000032 | 13.51 |

| 6 | 0.000024 | 0.00003 | 25 | 0.000021 | 12.50 |

| 10 | 0.000011 | 0.000015 | 36.36 | 0.000011 | 0.00 |

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 1 | -1.501 | -1.482 | 1.27 | -1.489 | 0.8 |

| 5 | -1.692 | -1.718 | 1.54 | -1.716 | 1.42 |

| 10 | -1.931 | -2.012 | 4.19 | -2 | 3.57 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000036 | 0.000039 | 8.3 | 0.000036 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.000021 | 0.000026 | 23.8 | 0.000024 | 14.3 |

| 10 | 0.0000093 | 0.000012 | 29.0 | 0.000011 | 18.3 |

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | -2.05 | -2.36 | 15.1 | -2.36 | 15.1 |

| 6 | -2,36 | -2.63 | 11.4 | -2,63 | 11.4 |

| 10 | -2.68 | -2.91 | 8.6 | -2.9 | 8.2 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000049 | 0.000058 | 18.4 | 0.000053 | 8.2 |

| 6 | 0.000031 | 0.000038 | 22.6 | 0.000036 | 16.1 |

| 10 | 0.000014 | 0.000019 | 35.7 | 0.000018 | 28.6 |

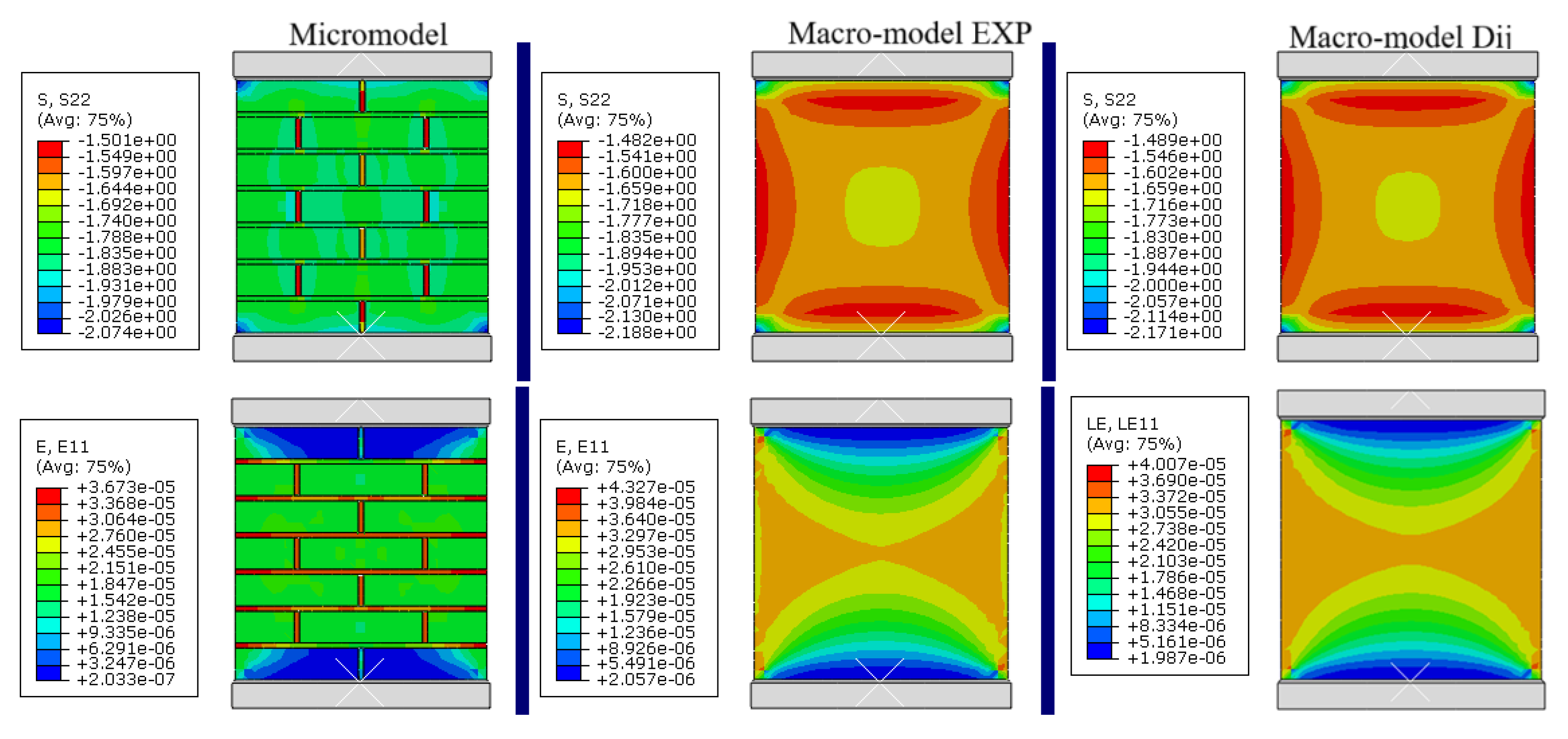

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 2 | -0.68 | -1.14 | 67.65 | -0.76 | 11.76 |

| 6 | -0.95 | -1.37 | 44.21 | -0.92 | 3.16 |

| 10 | -1.2 | -1.6 | 33.33 | -1.01 | 15.83 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load perpendicular to the seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000053 | 0.000071 | 33.96 | 0.000059 | 11.32 |

| 6 | 0.000032 | 0.000047 | 46.88 | 0.000038 | 18.75 |

| 10 | 0.000011 | 0.000022 | 100 | 0.000018 | 63.64 |

| № | (MPa) | -EXP (MPa) | EXP (%) | -D (MPa) | D (%) |

| Calculation of errors for vertical stresses under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | -0.66 | -1.2 | 81.82 | -1.2 | 81.82 |

| 6 | -1 | -1.4 | 40 | -1.4 | 40 |

| 10 | -1.3 | -1.6 | 23.08 | -1.5 | 15.38 |

| № | -EXP | EXP (%) | -D | D (%) | |

| Calculation of errors of horizontal deformations under load parallel to seams | |||||

| 2 | 0.000067 | 0.000072 | 7.46 | 0.000064 | 4.48 |

| 6 | 0.000043 | 0.000048 | 11.63 | 0.000043 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.000019 | 0.000024 | 26.32 | 0.000021 | 10.53 |

| Series | Parameter | Calculation by Dij (MPa) | Voigt Method (MPa) | Voigt errors (%) | Reuss Method (MPa) | Reuss errors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| КRО-1 | D11 | 11568.3 | 11980 | 3.6 | 10500 | 9.2 |

| D12 | 2545.0 | 1600 | 37.1 | 1200 | 52.8 | |

| D21 | 1684.2 | 1600 | 5.0 | 1200 | 28.7 | |

| D22 | 10201.4 | 10500 | 2.9 | 9200 | 9.8 | |

| D33 | 4786.5 | 4650 | 2.9 | 3900 | 18.5 | |

| КRО-2 | D11 | 11473.7 | 11500 | 0.2 | 9800 | 14.6 |

| D12 | 3442.1 | 1700 | 50.6 | 1300 | 62.2 | |

| D21 | 2085.9 | 1700 | 18.5 | 1300 | 37.7 | |

| D22 | 9074.1 | 9500 | 4.7 | 8000 | 11.8 | |

| D33 | 4341.5 | 4100 | 5.6 | 3500 | 19.4 | |

| КRО-3 | D11 | 7264.9 | 9800 | 34.9 | 7500 | 3.2 |

| D12 | 2542.8 | 1800 | 29.2 | 1400 | 44.9 | |

| D21 | 1856.1 | 1800 | 29.2 | 1400 | 44.9 | |

| D22 | 5799.5 | 6500 | 12.1 | 5000 | 13.8 | |

| D33 | 2443.2 | 4100 | 67.8% | 3500 | 43.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).