2.1. Watermark

A digital watermark is identification information intentionally incorporated into an image, sound, video, or document that remains associated with the file during processing. Its basic functions include confirming the source or owner of the content, tracking its distribution, and, in some systems, user authorization. A watermark can be visible, such as a semi-transparent logo that discourages unauthorized use, or hidden, embedded in the spatial or frequency domain in a way that is invisible to the viewer but can be read after typical editing operations such as compression, scaling, or cropping [

10,

18].

The key features of a well-designed watermark include: robustness, imperceptibility to the end user, capacity to store additional bits, and security against counterfeiting. In practice, this requires a compromise: the more robust the mark, the greater the interference with the data and the potential deterioration in quality; the more discreet it is, the more difficult it is to ensure its readability after aggressive processing. In the case of publicly published content, a hybrid approach is often employed – a visible logo serves as a deterrent against simple copying. At the same time, a hidden identifier facilitates the enforcement of rights in the event of a dispute [

19].

This analysis considers two extreme variants of watermarking – visible and invisible – as they represent two basic content protection strategies, directly noticeable or completely invisible to the end user. The research does not focus on preserving the semantic content encoded in the watermark, but on assessing its resistance to DeepFake-type modifications.

2.1.1. Visible Watermark

The analysis employed an explicit watermark in the form of a QR code spanning the entire frame. This solution ensures the uniform distribution of the mark’s pixels in the image and eliminates the risk of omitting any area when assessing the marking’s impact.

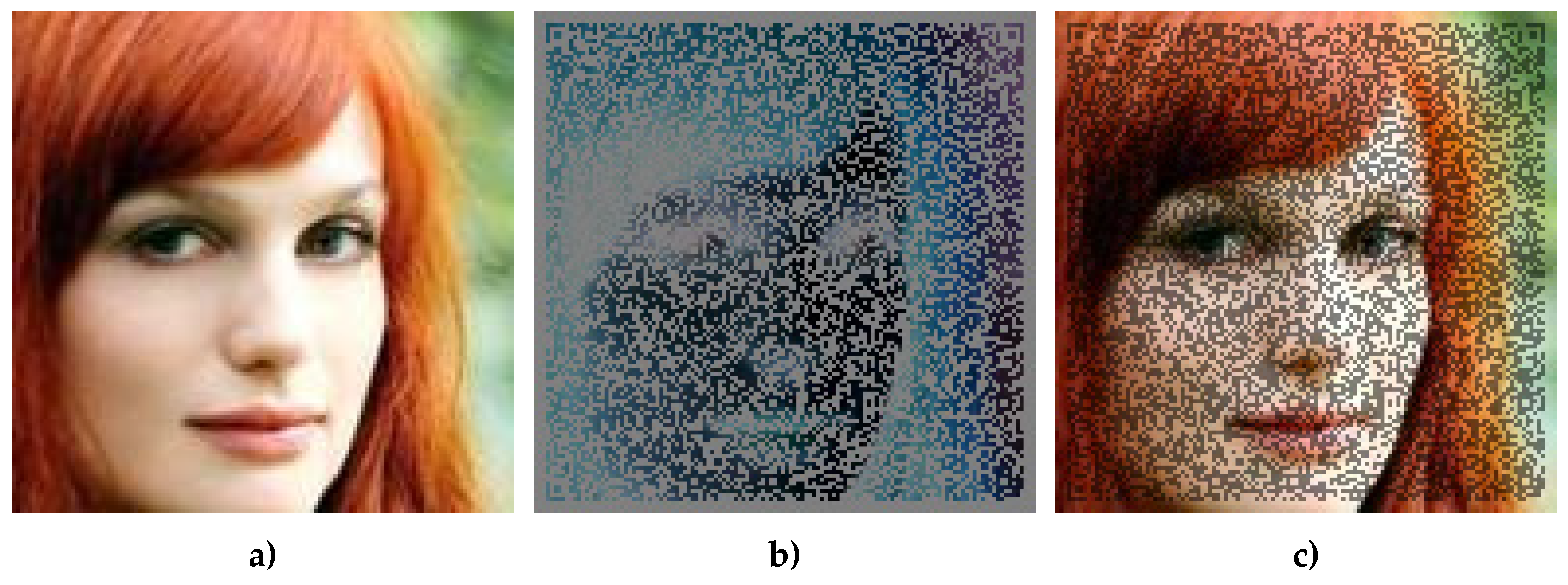

For clarity, a single example – a synthetic face image – is presented in three variants: (a) reference image without a watermark, (b) the difference between the image with a watermark and the reference image, and (c) a composition of both images with a selected level of transparency (

Figure 1a–c). This presentation enables us to evaluate the degree to which an explicit watermark affects the image’s details, even before DeepFake methods are applied.

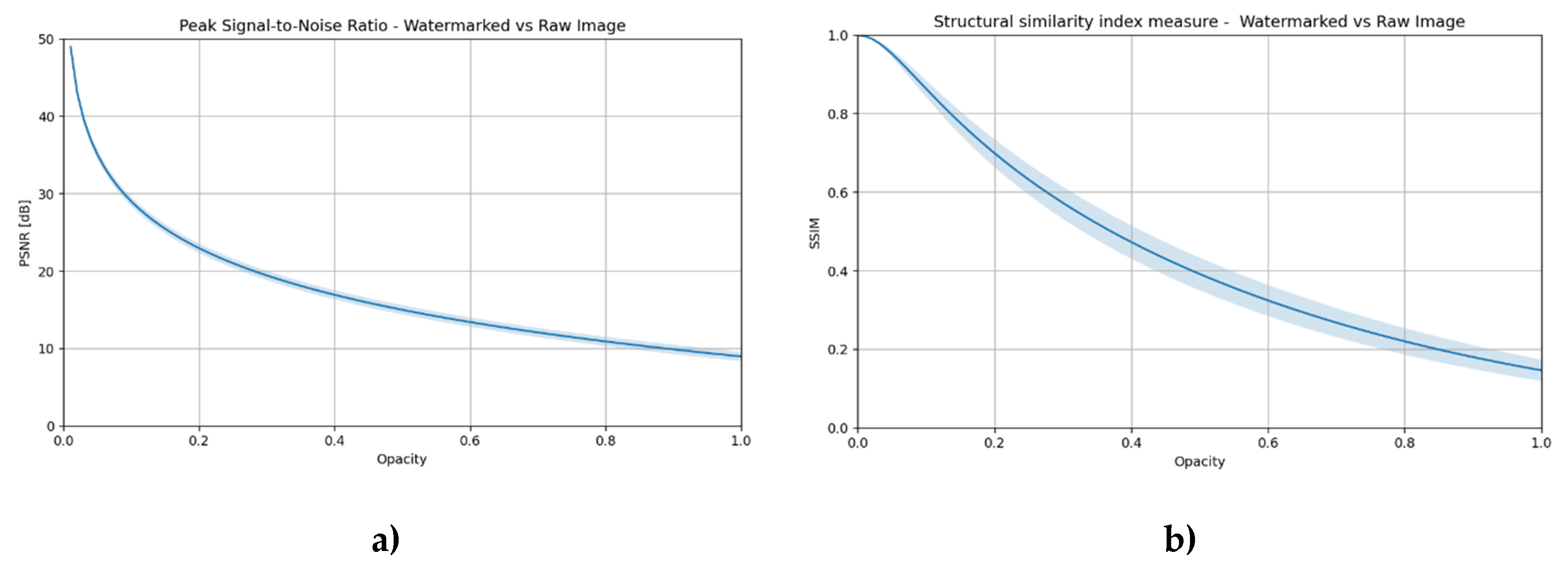

The impact of transparency on image distortion was determined using two commonly used quality metrics: PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (Structural Similarity Index) [

20].

Figure 2 illustrates the dependence of these metrics on the opacity parameter, which ranges from 0 to 1, corresponding to the level of watermark visibility. The observed curves illustrate a decrease in image quality as the visibility of the mark increases. These graphs serve as a reference point in both subsequent chapters and the experimental part, where the impact of different transparency levels on the effectiveness of DeepFake methods will be analyzed.

2.1.2. Invisible Watermark

The second option analyzed is a hidden watermark embedded using a neural network. Its purpose is to remain completely invisible to the recipient while remaining resistant to typical image processing operations. Many methods of this type have been described in the literature; however, in most cases, it is not possible to precisely control the strength of the interference [

7,

8]. In studies focused solely on assessing the effectiveness of watermark reading or its impact on a selected task (e.g., classification) [

9], such a limitation may be acceptable. However, in a broader analysis—especially when the goal is to generalize the results to an entire group of algorithms (in our case, local face replacement)—it can significantly complicate interpretation.

For this reason, a proprietary model has been developed that allows for smooth adjustment of the watermark signal amplitude – from virtually undetectable to deliberately visible. This allows for a precise examination of the relationship between the strength of the mark and its susceptibility to local modifications, such as DeepFakes.

The designed architecture is based on the classic encoder–decoder approach. The encoder receives an image, to which it matches a watermark, and a message to be embedded. The generated watermark, controlled by the “watermark strength” parameter, is then added to the original image. The resulting image can be manipulated in any way (e.g., face swap), and its degraded version is sent to the decoder, whose task is to recover the encoded message. The invisible watermark used here is purposefully a controllable test instrument rather than a proposed state-of-the-art algorithm. Its novelty for this paper lies in its practicality: the strength parameter is continuously tunable, which enables calibrated sweeps that isolate how watermark energy interacts with generator-induced transforms. This controllability is required to compare visible vs. invisible marks under identical experimental conditions and is not intended as a claim of algorithmic novelty in watermarking.

The encoder was built based on a modified U-Net architecture [

21], equipped with FiLM (Feature-wise Linear Modulation) layers [

22], which enable the entry of message information at different resolution levels. Residual connections have also been added [

23] between successive U-Net levels, which improves gradient flow—a crucial aspect in architectures where part of the cost function is calculated only after the decoder. The encoder output is transformed by a tanh function (with a range of -1 to 1) and then scaled by the “watermark power” parameter (default: 0.1). The default value of the “watermark strength” parameter = 0.1 was adopted experimentally as the midpoint of the range [-1, 1] used in the training process. It ensured a clear yet moderate level of interference with the image, allowing for tests of both greater subtlety and higher visibility of the marker.

To increase the generality of the model and avoid situations where the network hides the watermark only in selected locations, a set of random perturbations was used during training: Gaussian noise, motion blur, Gaussian blur, brightness and contrast changes, resized crop, and random erasing. These were not intended to teach resistance to specific attacks (e.g., face swap), but to force the even distribution of the watermark throughout the image.

The decoder is based on the ResNet architecture [

24], whose task is to reduce a tensor containing a degraded image to a vector representing the encoded message.

The learning process involved two primary components of the cost function. The first concerned the correctness of message reading by the decoder.:

where z – output tensor from the decoder, m – coded message.

The second component was responsible for minimizing the visibility of the watermark. For this purpose, a combination of mean square error (MSE) and LPIPS metrics was used [

25], better reflecting the difference between images as perceived by humans:

where

- image with watermark,

– original image.

All images were scaled to a resolution of 128 × 128 pixels. The adopted resolution of 128×128 pixels is lower than typical in practical applications. This limitation was due to the computational requirements associated with training multiple deepfake networks and a watermarking model in real time, given the available hardware resources. For the comparative analysis, maintaining consistent experimental conditions was more important than achieving absolute image resolution. The message length was set to 64 bits, generated randomly during training. VGGFace2 [

26] was used as the dataset, containing photos of different people, which allowed for consistency with the rest of the experiments.

In the case of this model, the key indicator in the context of comparative analysis is not the fact that the message was read correctly (full effectiveness was achieved during training), but the impact of the “strength” parameter of the watermark on its actual visibility and level of interference with the image.

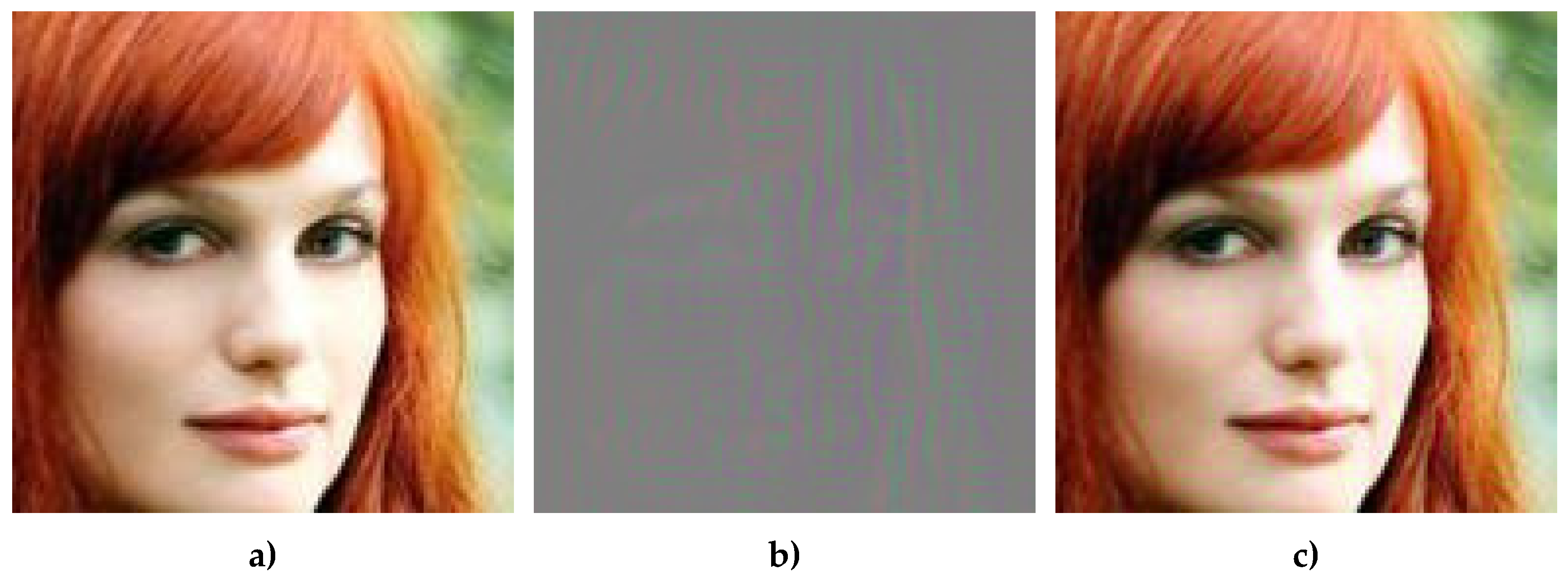

Figure 3 illustrates an example of an image in the default configuration (watermark strength = 0.1) along with its corresponding difference map.

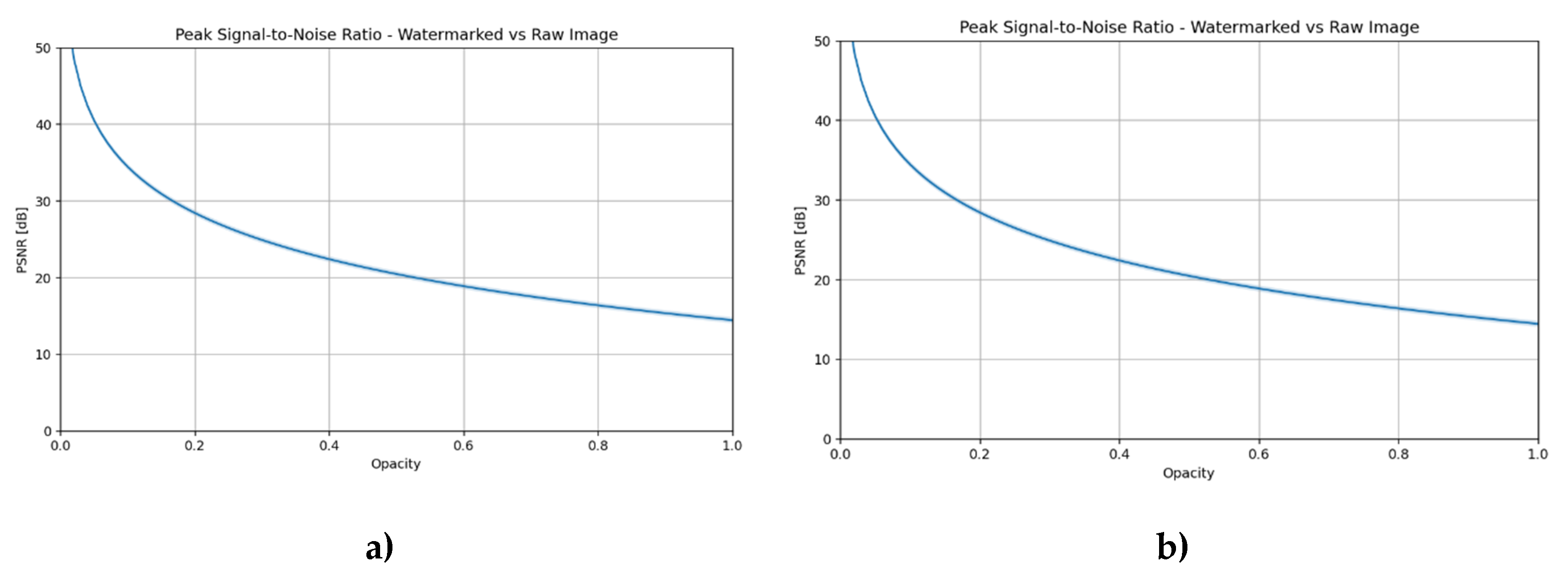

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of the “strength” parameter on PSNR and SSIM metrics compared to the original image [

8].

2.2. Face Swap

Face swap is a class of generative algorithms whose goal is to insert a source face into a target image or video in a way that is believable to a human observer, with no visible traces of modification [

11,

27]. The typical process includes: face detection and alignment, extraction of its semantic representation (embedding), reconstruction or conditional generation of a new texture, and applying it with a blending mask to the output frame [

11].

Although theoretically the modification should be limited to the face area, in practice many models – especially those based on generative adversarial networks (GANs) – also affect the background, lighting, and global color statistics. There are many reasons for this behavior, ranging from the nature of the cost functions used to the specifics and complexity of the model architecture.

In the context of watermarking, this leads to two significant consequences. First, even local substitution can unintentionally distort the signal hidden throughout the image, reducing the effectiveness of invisible watermarking techniques. Second, suppose the visible watermark is located near a face or its pattern resembles an image artifact. In that case, the model may attempt to “correct” it, resulting in reduced legibility of the mark.

For further analysis, popular end-to-end networks such as SimSwap [

12] and FaceShifter [

13] were selected, as well as newer designs incorporating additional segmentation models, key point generation (Ghost [

14], FastFake [

15]), or closed solutions – InsightFace [

16]. Each of these methods controls the scope of editing differently and achieves a different compromise between photorealism and precise control of the modification region.

In some cases, it was necessary to reimplement or adapt the models to meet the established experiment criteria, which may result in slight differences from the results presented by the authors of the original algorithms. Where possible, the same architectures and cost functions as in the original implementations were retained.

To establish a reference point, a proprietary reference method was also developed, based on classic inpainting in the face segmentation mask area. This method edits only the face region, preserving the background pixels, which allows for estimating the minimal impact of a perfectly localized face swap on the watermark. A comparison of these approaches will enable us to determine the extent to which modern, intensely trained models interfere with image content outside the target modification area and to present the theoretical reasons for this behavior.

2.2.1. SimSwap

SimSwap [

12] is one of the first publicly available architectures that enable identity swapping for arbitrary pairs of faces without requiring retraining of the network. It combines the simplicity of a single encoder–decoder–GAN setup with the ability to work in many-to-many mode.

The key element of SimSwap is the ID Injection module. After encoding the target frame, the identity vector from the source—obtained from a pre-trained ArcFace model [

28]—is injected into the deep layers of the generator using Adaptive Instance Normalization (AdaIN) blocks [

29].

To preserve the facial expressions, pose, and lighting of the target image, the authors introduced Weak Feature Matching Loss, which compares the deep output representations of the discriminator between the target image and the reference image. This function promotes the consistency of visual attributes by treating the discriminator as a measure of realism rather than identity consistency.

Identity is enforced through a cost function based on the cosine distance between ArcFace embedding vectors. The realism of the generated images is improved by classic hinge-GAN loss and gradient penalty [

30]. Additional Reconstruction Loss is activated when the source and target images depict the same person – in this case, the network learns to minimize changes in the image.

In practice, this combination of cost functions means that modifications are concentrated mainly in the face area, while the background and clothing elements remain largely unaffected. However, the lack of an explicit segmentation mask means that subtle color corrections may occur throughout the frame when there are substantial exposure changes or low contrast.

2.2.2. FaceShifter

FaceShifter [

13] is a two-stage face swap network designed to preserve the identity of the source without requiring training for each pair. In the first phase (AEI-Net), the following components are combined: an identity embedding obtained from ArcFace [

28] and multi-level attribute maps generated by a U-Net encoder.

Integration is achieved using the Adaptive Attentional Denormalization (AAD) mechanism, which dynamically determines whether a given feature fragment should originate from the embedding ID or the attribute maps. In addition to identity loss, adversarial loss, and reconstruction loss, the cost function also uses attribute loss, which enforces attribute consistency between the target image and the replaced image.

The lack of an explicit segmentation mask means that, in cases of significant differences in lighting or color, AAD can also modify the background, which, from a watermarking perspective, increases the risk of distorting the invisible watermark. At the same time, precise attention masks within AAD keep the primary energy of changes within the face.

2.2.3. Ghost

Authors of GHOST [

14] presented a comprehensive, single-shot pipeline that covers all stages – from face detection to generation and super-resolution. However, only the GAN core is relevant in the context of this analysis. The basic architecture is a variation of AEI-Net known from FaceShifter, but with several significant modifications.

Similar to FaceShifter, the identity vector obtained from the ArcFace model is injected into the generator using Adaptive Attentional Denormalization (AAD) layers. A new feature is the use of an additional network targeting the eye region, along with a redesigned cost function – specifically, eye loss – which enables the stable reproduction of gaze direction in the generated image.

The second improvement is the adaptive blending mechanism, which dynamically expands or narrows the face mask based on the differences between the landmarks of the source and target images. This solution enhances the fit of the face shape and edges, thereby increasing the realism of the generated image.

However, in this work, the adaptive blending and super-resolution stages were omitted to focus solely on the analysis of pixel destruction introduced by the generator itself. Furthermore, some of the elements introduced in GHOST, such as adaptive blending, are not differentiable, which could disrupt the training process if a labeling model is to be used, treating face swaps as noise in the learning process.

2.2.4. FastFake

Fast Fake [

15] is one of the newer examples of a lightweight GAN-based face swap, where the priority is fast and stable learning on small datasets, rather than achieving photographic perfection in each frame. The core of the model is a generator with Adaptive Attentional Denormalization (AAD) blocks, borrowed from FaceShifter [

13]. Still, the entire architecture was designed in the spirit of FastGAN [

31], featuring fewer channels, a skip-layer excitation mechanism [

32], and a discriminator capable of reconstructing images, which helps limit the phenomenon of mode collapse.

The key difference from the previously discussed models lies in the way segmentation is utilized. The authors include a mask from the BiSeNet network [

33] only at the loss calculation stage – pixels outside the face area are sent to the reconstructive MSE, and features obtained from the parser are additionally blurred and compared with analogous maps of the generated image. As a result, the generator learns to ignore the background, because any unjustified change in color increases the loss value. During inference, the mask is no longer used, keeping the computation flow clean and fast.

From the perspective of analyzing the impact of DeepFake on watermarking, this approach has significant implications. The scope of FastFake interference is even narrower than in SimSwap or FaceShifter – global color statistics change minimally, which potentially favors the protection of watermarks placed outside the face area. In theory, the GAN cost function should interfere to some extent with the component that enforces background preservation. However, it cannot be ruled out that the generator will still harm unusual elements of the image, such as watermarks.

Thanks to its low data requirements and fast learning process, FastFake is a representative example of the “economical” branch of face swap methods, which will be compared with other models in terms of their impact on the durability and legibility of watermarks later in this article.

2.2.5. InsightFace

The InsightFace Team [

16] has not published a formal article describing the Inswapper module; however, this model is widely used in open-source tools, including Deep-Live-Cam [

34], and functions as an informal “market standard” in the field of face swapping.

Similar to the previously discussed methods, Inswapper uses a pre-trained ArcFace model to determine the target’s identity. Although the implementation details are not fully known, a significant difference is the surrounding pipeline: InsightFace provides a complete SDK with its own face detection module and predefined cropping, which also includes arms and a portion of the background. If the detector does not detect a face or rates its quality below a certain threshold, the frame remains unchanged. In the context of watermarking, this means that elements outside the detected face mask can remain completely intact. This feature is also valuable for experiments – it allows you to assess whether the degradation of the watermark is significant enough to prevent the image from being used by popular face swap algorithms.

For this paper, the analysis is limited to the generator block and the mandatory face detector, omitting subsequent stages of the pipeline, such as skin smoothing and super-resolution. In this context, Inswapper serves as a realistic but minimal attack: any violation of the watermark is solely the result of identity substitution—provided that the face is detected and passed on for processing—which reflects a typical use case in popular consumer tools.

2.2.6. Baseline

The last face swap algorithm analyzed is a proprietary reference method explicitly developed for this comparison. Although it does not achieve SOTA results on its own, it stands out with its local face replacement range and an interesting approach to separating information from sources of the same type. Unlike the previously discussed GAN models, the training process uses elements characteristic of currently popular diffusion models [

35].

The algorithm consists of three main components:

U-Net – typical for diffusion models, responsible for removing the noise.

Identity encoder – compresses input data into a one-dimensional hidden space; receives a photo of the same person, but in a different shot, pose, or lighting.

Attribute encoder – also compresses data into a hidden space, but accepts the target image in its original form.

At the input, U-Net receives an image with a noisy face area (following the diffusion model approach) and a set of conditions: noise level, attribute vector, and identity vector.

The goal of the model is to recreate the input image based on additional information provided through conditioning. During inference, when a face of another person is fed to the identity encoder, the U-Net generates an image with the identity swapped, while preserving the pose, facial expressions, and lighting resulting from the attribute vector.

The key challenge is to motivate the model to utilize information from the identity encoder, rather than solely from the attribute encoder, which, in the absence of constraints, could contain all the data necessary for reconstruction. To prevent this, three modifications to the attribute vector were applied:

Masking – randomly zeroing fragments of a vector, which forces the model to draw information from the identity encoder, as they may be insufficient on their own.

Dropout – increases the dispersion of information in the vector, preventing data concentration in rarely masked fragments.

Normal distribution constraint (KL divergence loss) – inspired by the VAE approach [

36]; forces the elements of the attribute vector to carry a limited amount of information about the details of a specific image.

Thanks to these modifications, the model distributes information more evenly in the hidden space and obtains most of the identification features from the identity encoder.

During inference, the user can control both the noise step (typical for diffusion models) and the masking level of the attribute vector. Only one diffusion step was used in the study – subsequent steps would only improve the visual quality of the face swap without significantly affecting the hidden watermark.

The selection of masking levels within the Baseline method was based on a series of preliminary tests with a trained network. The parameters were selected to ensure that the effect of masking on the extent of image modification was subjectively visible, while maintaining a comparable quality of the generated face. This differentiation enabled the analysis of how varying degrees of attribute isolation impact the degradation of the watermark.

The ability to control the noise level enables the generation of multiple test samples for various initial settings. In addition to analyzing the impact on the watermark, this approach can be used to augment training data for face-swap-resistant tagging systems.

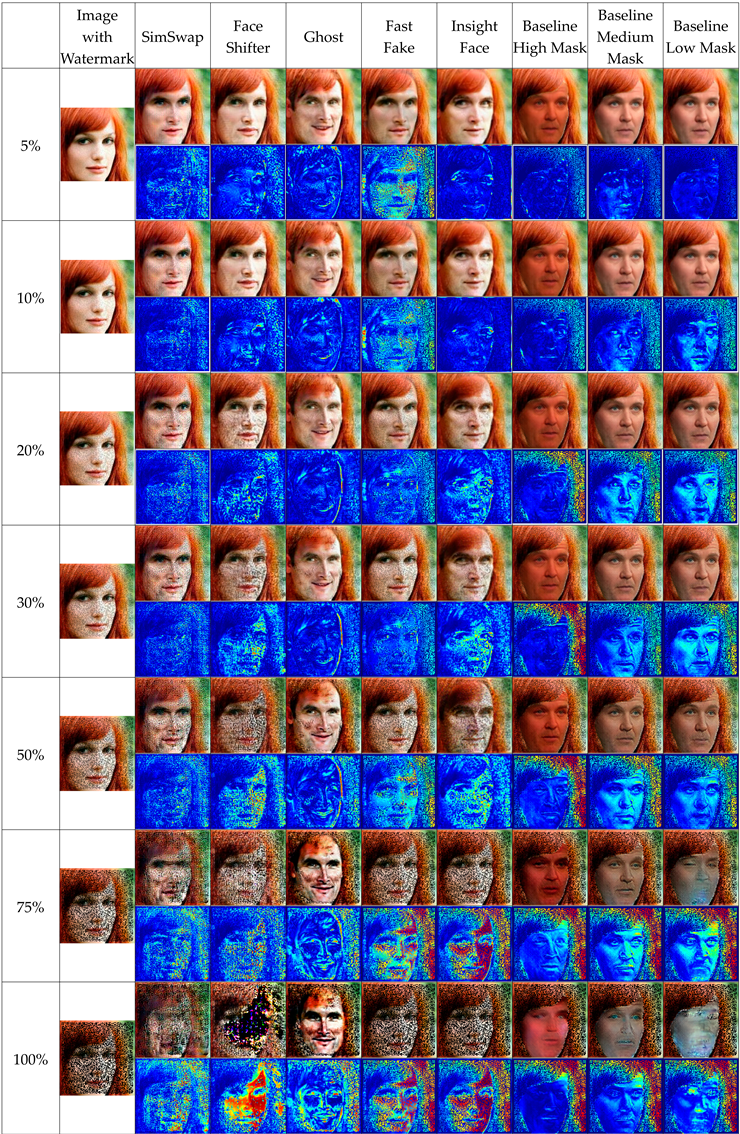

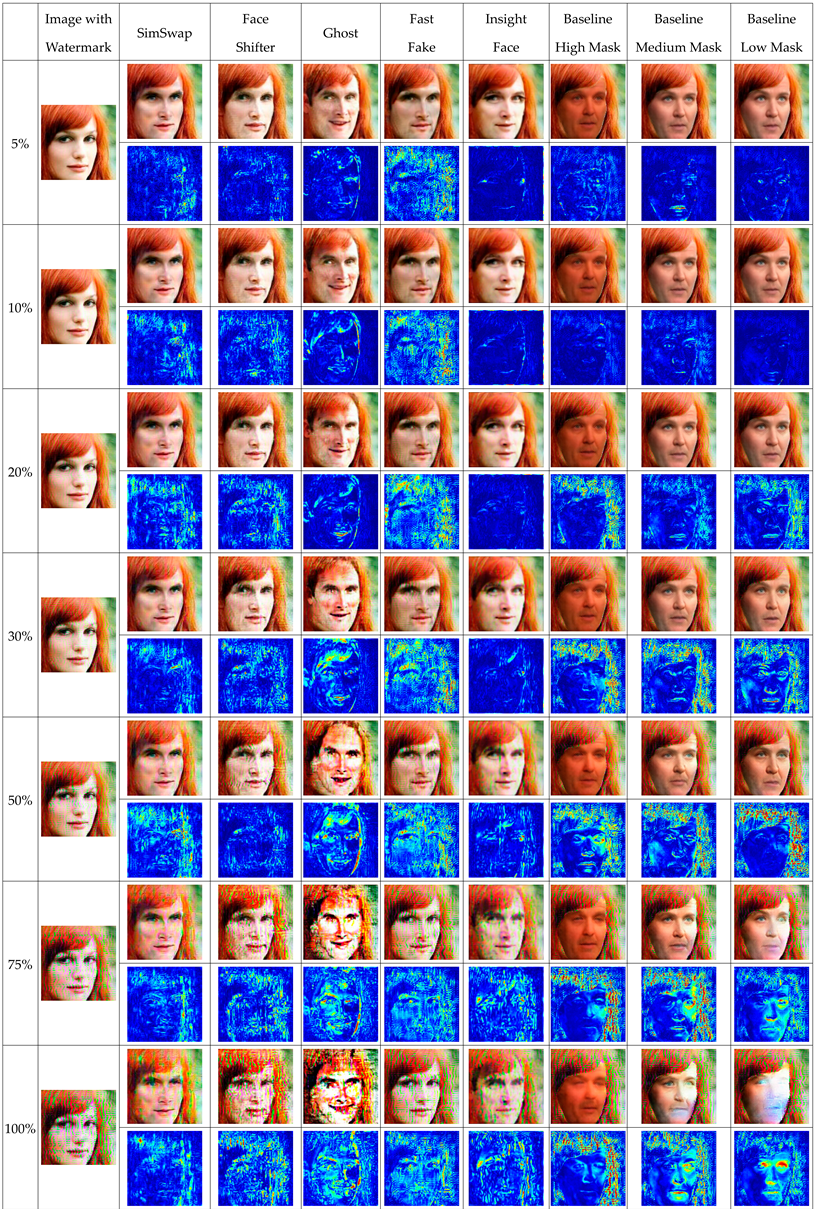

2.2.7. Examples of Implemented Deepfakes

Images from the VGGFace2 [

26] dataset were used for unit testing, shown in

Figure 5:

- a)

image of the target face – the one that will be replaced,

- b)

source identity for face swap algorithms.

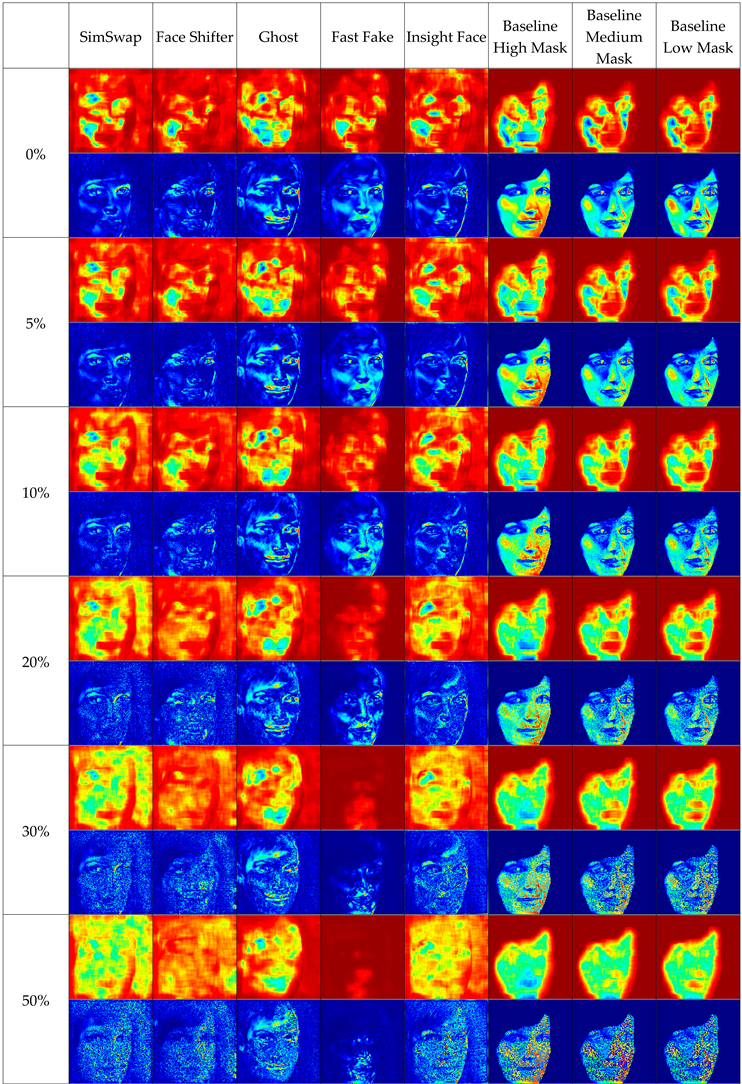

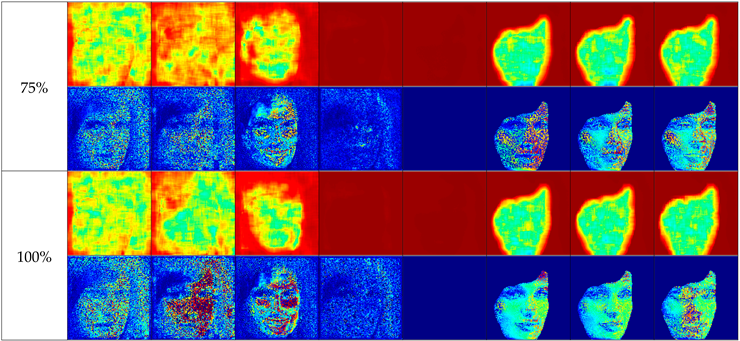

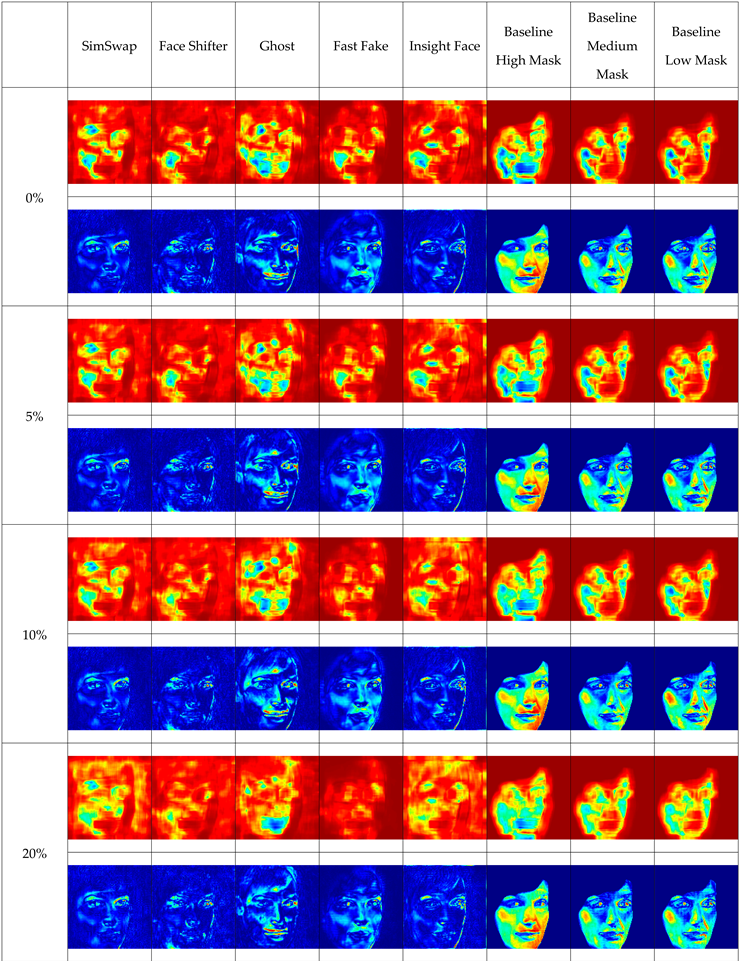

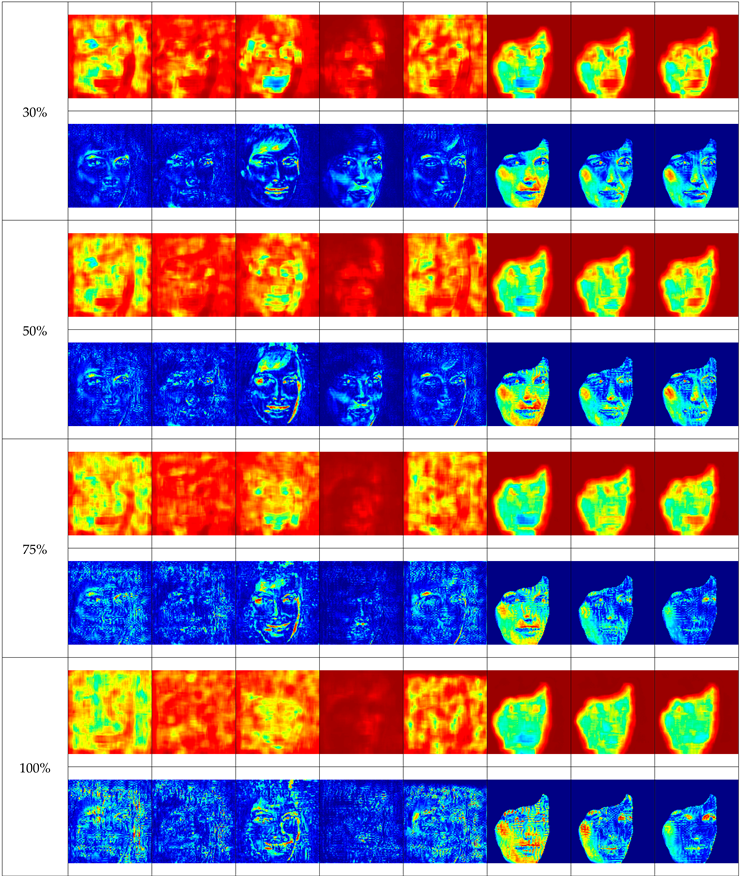

Table 1 presents the sample face replacement results obtained for all models discussed (SimSwap, FaceShifter, GHOST, FastFake, InsightFace, and Baseline), along with heat maps illustrating the changes made. For the baseline model, three variants are presented, corresponding to different levels of attribute vector masking (high, medium, low).

The table shows that some deepfake algorithms also introduce changes in the background of the image. This is particularly evident in the SimSwap and FaceShifter methods, where the right side of the heat maps indicates significant modifications outside the face area.

2.3. Experiments

Several research scenarios were conducted as part of the analysis. Due to the intertwining nature of the individual experiments, they were divided into two main blocks: visible tagging and hidden tagging. Each block broadly covers analogous types of analysis, specifically examining the impact of tagging on face swapping on a global scale, broken down into face and background areas.

First, the results for visible tagging will be presented, followed by those for hidden tagging. In both cases, individual examples of the impact of tagging with different parameter configurations are presented, followed by a statistical overview based on a test set.

The primary metrics used in the analyses are:

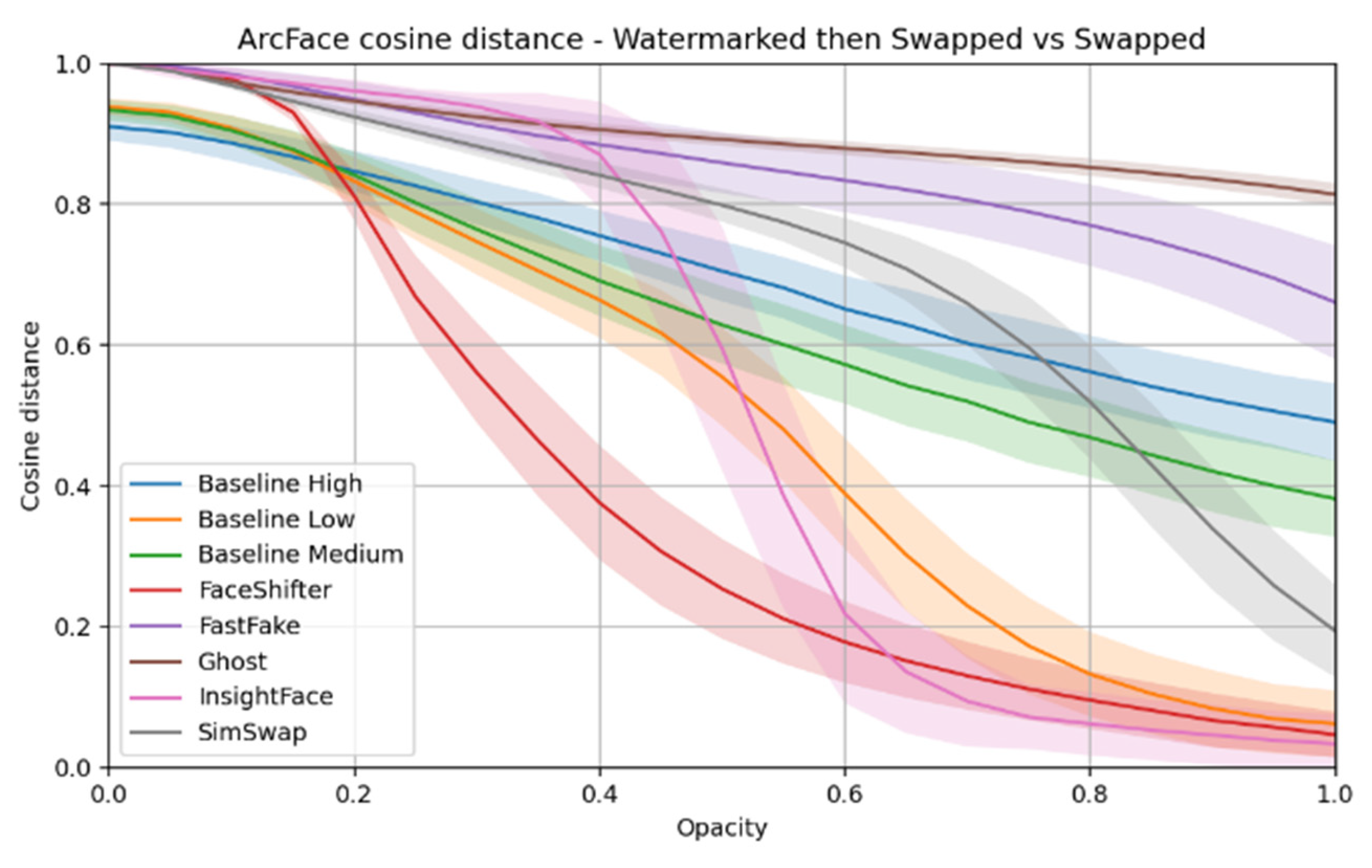

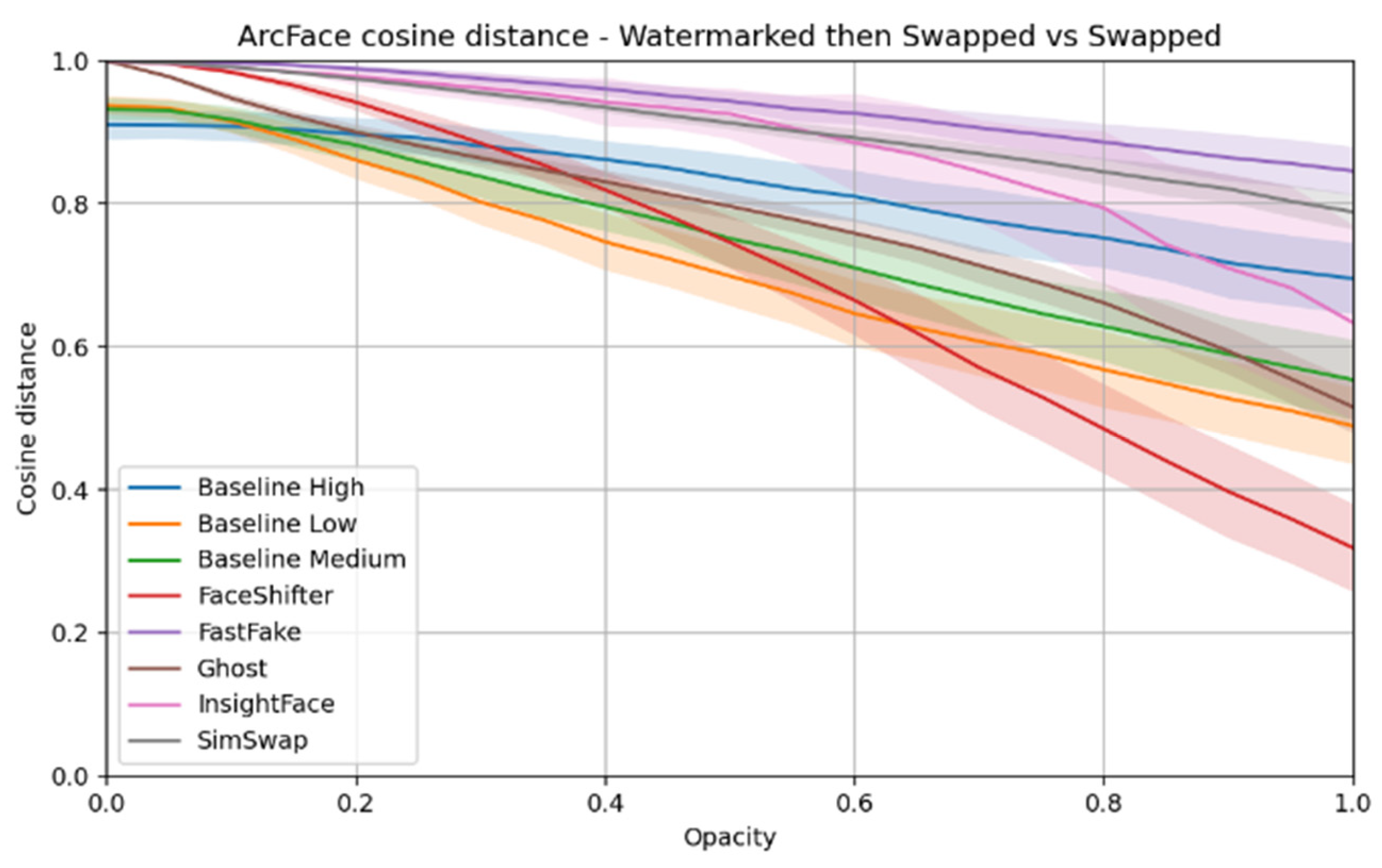

ArcFace distance – the cosine distance between feature vectors extracted by the ArcFace model, allowing to assess whether the persons depicted in the compared images are recognized as the same.

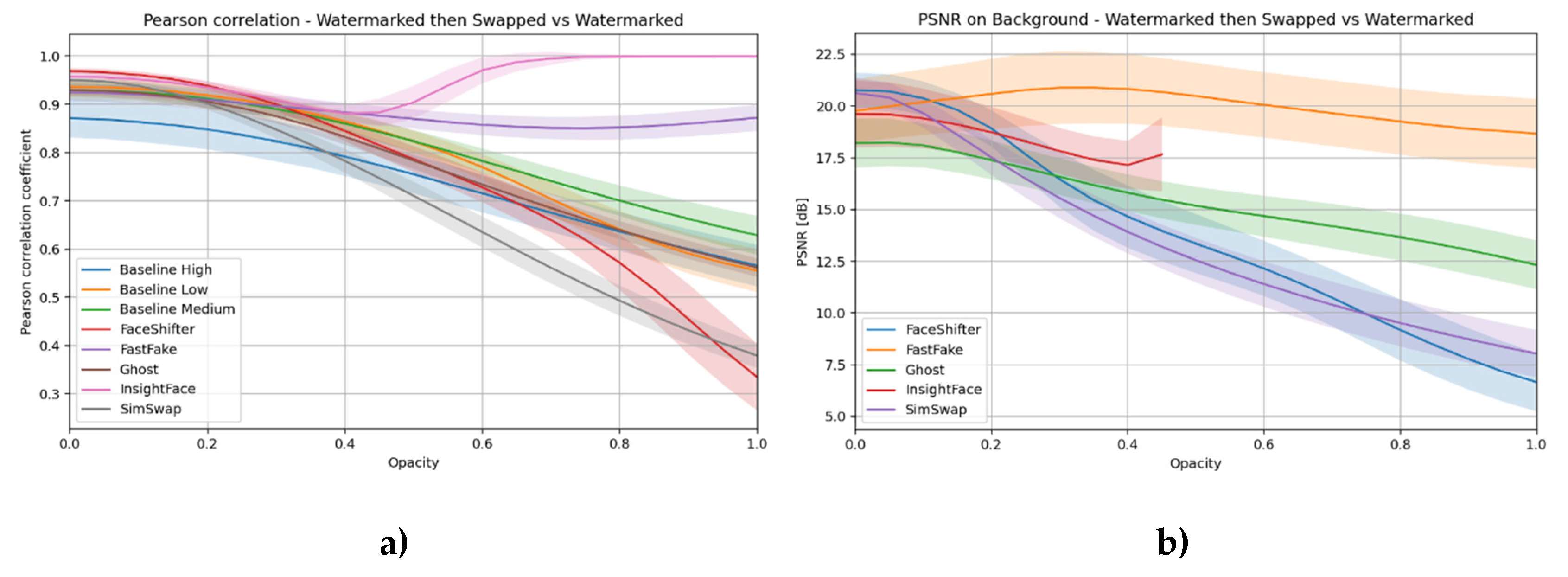

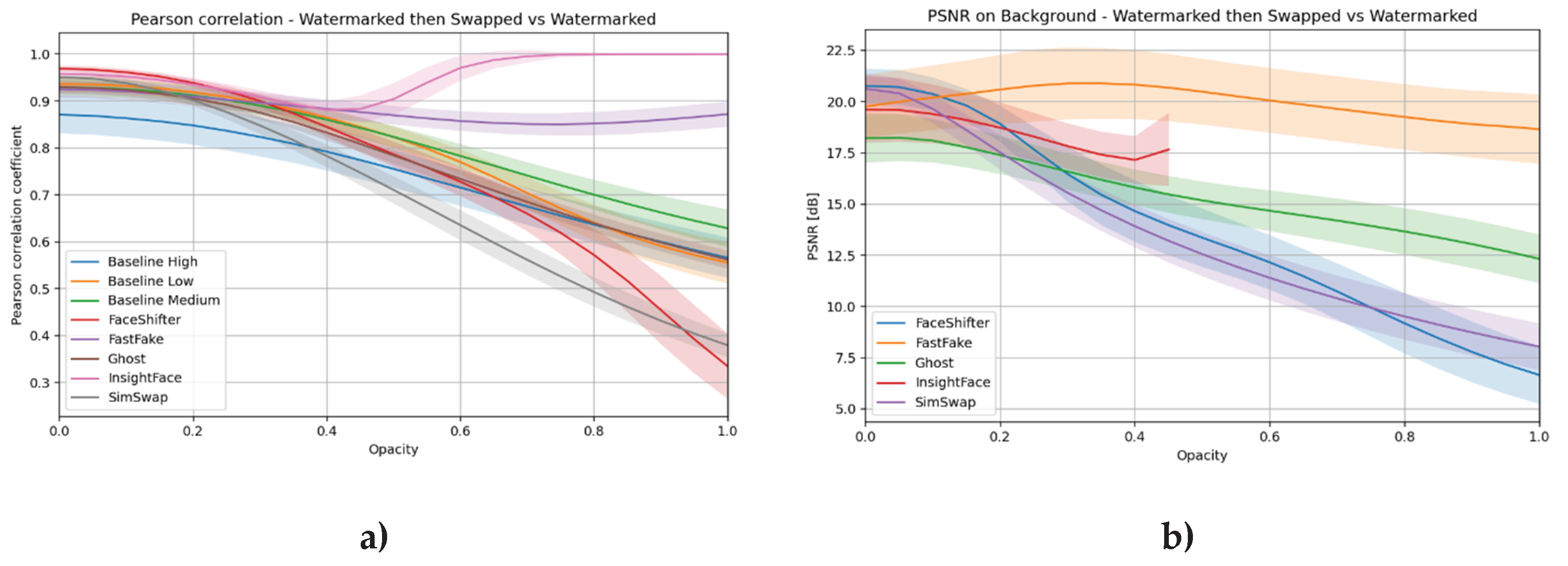

Pearson correlation – Pearson correlation coefficient between the image with the watermark and the image after applying face swap to the material containing the watermark.

PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) – used additionally in local analyses for a selected area (background).

The study analyzed two fundamental aspects:

The impact of watermarks on face swaps:

Heatmaps of differences between the image after face swap performed on material with a watermark and the image after face swap performed on material without a watermark were compared.

The ArcFace distance between these two variants was calculated to assess the impact of marking on identity recognition.

Watermark retention:

The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated between the original image with the watermark and the image after face swapping was performed on the same image.

Correlation maps and heat maps showing the distribution of changes in the image were generated.

In local analyses, the background area was examined separately by calculating the PSNR for this region to estimate the impact of face swap outside the face area.

All experiments were performed on the VGGFace2 dataset. The VGGFace2 dataset includes photographs with varying lighting conditions, quality, compression, and cropping, which allowed us to naturally incorporate the diversity typical of images obtained from the web into our experiments. For each combination of parameters, calculations were performed on 1000 examples, allowing for statistically significant comparisons. We compare the results with a local baseline, which allows us to quantitatively demonstrate the non-locality of editing outside the face area.