1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

The epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) in elderly patients has changed over the past decade, with a rise in oropharyngeal cancers, likely due to HPV, and a fall in tobacco- and alcohol-related cancers in the oral cavity, larynx, and hypopharynx [

1]. The limited data available may not apply to older patients in current practice, and high-level evidence must be available to guide the treatment.

Elderly patients also often have more health problems in general, and they are less capable of tolerating treatment. [

2]. In addition, studies have found that older adults do not benefit from extra treatment, such as chemotherapy, which can be given together with radiation therapy (RT).

RT is the most feasible treatment for older patients presenting with locally advanced (LA) head and neck carcinoma. The association with chemotherapy has been shown to have detrimental results in terms of toxicity [

3]. This may result in an unsatisfactory response to radiotherapy, and attempts should be made to enhance treatment outcomes. It has been hypothesized that hypofractionated schemes have the potential to be more biologically effective and reduce overall treatment times. However, particular attention should be focused on the potential increase in toxicity associated with these dose regimens. An emerging therapeutic approach is spatially fractionated radiotherapy (SFRT), which treats bulky tumoral mass to stimulate the immunologic response against the tumor [

4].

In this study, we present a case of advanced cheek cancer that has infiltrated and ulcerated the skin of the face. The patient was treated with a metabolic-guided non-geometric Lattice approach in combination with a normofractionated radiation scheme.

2. Case Presentation

An 82-year-old woman presented with an ulcerating lesion of the right cheek with pain, mucopurulent discharge, and fixed to the underlying planes. Confluent lymphadenopathies in the right laterocervical region at the IB level were visible.

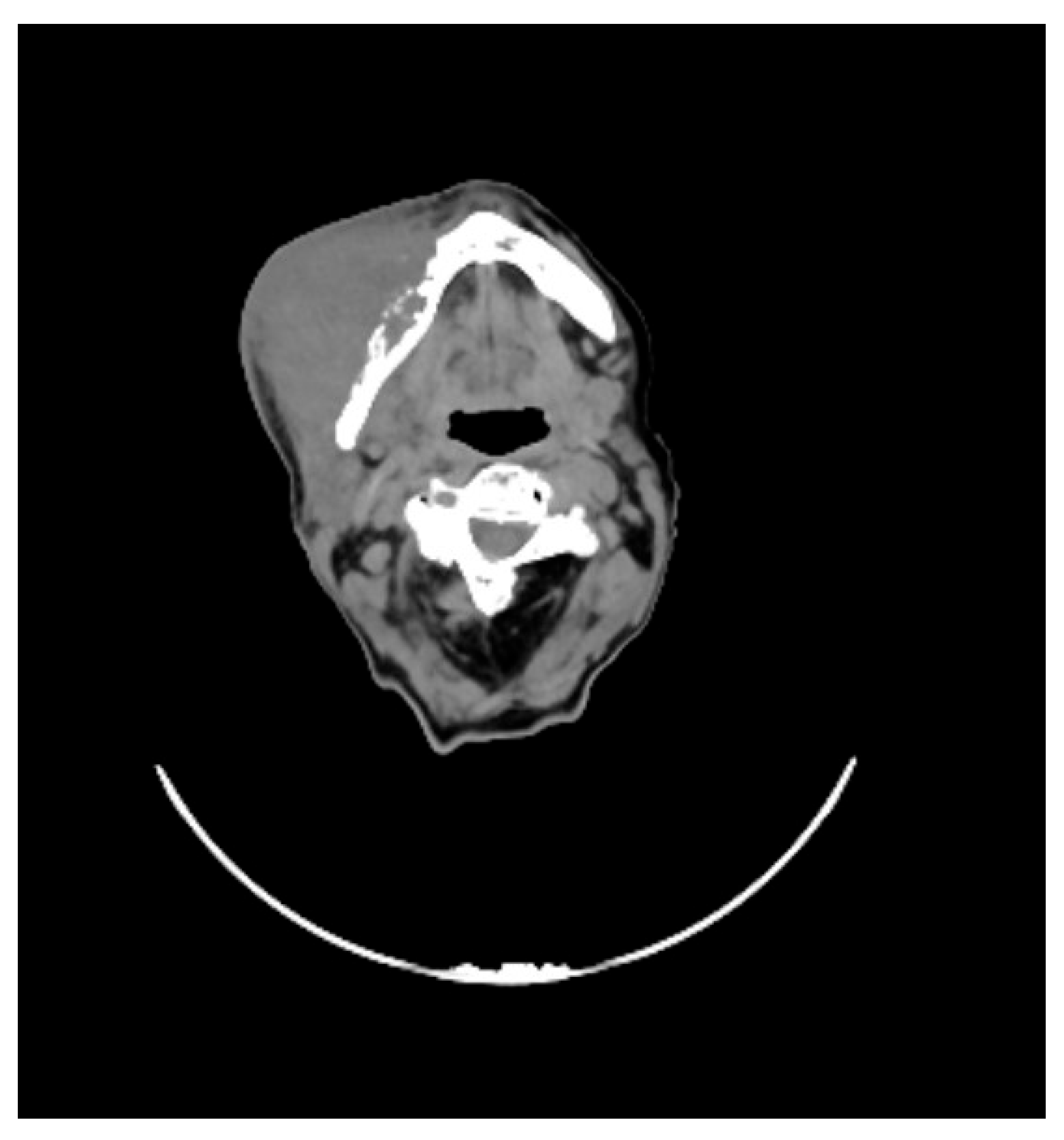

She underwent maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed a lesion of the right genial mucosa with infiltration of the skin, buccinator muscle, and the cortex of the mandibular bone, affecting the alveolar canal, other than the presence of necrotic, colliquative, and confluent lymphadenopathies (

Figure 1).

A Positron emission tomography (PET) scan revealed intense uptake of the radiopharmaceutical of the known right cheek lesion (SUV max 12.20) and the presence of contextual hypodense areas of necrotic colliquative significance. The presence of lymphadenopathies in the ipsilateral submandibular level was evident.

The patient underwent an incisional biopsy of the lesion, which revealed the presence of high-grade squamous cell carcinoma with a proliferating index (Ki67) of 50%.

The patient was staged as cT4N2a based on the 8th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging of Head and Neck Cancer.

After acquiring written consent, the patient was deemed suitable for exclusive radiotherapy.

RT treatment was delivered using a combined approach; in fact, the patient received a single session of LATTICE radiotherapy (LRT), followed, after 72 hours, by conventional volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy (cVMAT). The patient was simulated in the treatment position and immobilized with a thermoplastic mask. The CT planning images were acquired on the SOMATOM Sensation 16 Slice CT (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Slices of 3 mm thickness were obtained from the vertex of the skull to the sternoclavicular junction level. Subsequently, simulation plan data were transferred to the Monaco treatment planning system (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden). For LRT, CT scans for planning purposes were co-registered with an 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan.

A bulky Gross Tumor Volume (B-GTV) was contoured, and this comprised both the primary tumoral mass and the gross lymphadenopathies visible on imaging studies. We chose a “metabolism-guided” lattice radiation treatment planning that we have previously described [

5], delivering a spatially fractionated high radiation dose in two spherical deposits (vertices, Vs) within the bulky disease. Vs were allocated in a non-geometrical fashion between areas with different 18FDG/CT-PET metabolic activity (

Figure 2). The dose delivered to the Vs was a single fraction of 10 Gy using a Stereotactic Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (SVMAT) technique.

Three days after, the patient was treated with conventional radiotherapy. We defined a clinical target volume (CTV) expanding, isotropically, the B-GTV with a margin of 5 mm in all directions but taking in account adjacent clinical structure as bones and skin and a dose of 60Gy in 30 fractions was delivered (

Figure 3). Furthermore, a low-risk clinical nodal volume (CNV) including the right Robbin levels from IA to IV and delivered a dose of 54 Gy in 30 fractions.

The dosimetric analysis was based on the International Commission of Radiological Units and Measurements Reports 50 and 62. All plans were optimized to ensure target coverage and adhere to OAR dose constraints, referring to the Corsair parameters [

6] as D mean, Dmax, and percentage of volume receiving any dose (Vx). For CTV and CNV we evaluated V95, V107, and Dmax; Dmean for the parotids and submandibular glands; Dmean for the oral cavity, Dmax, V50, and V42 for the mandible; Dmean for the constrictor muscles; Dmean, V35, V50, and V70.

The patient completed the treatment without interruption. Ninety days after the conclusion of the treatment course the patient was re-evaluated with a PET-CT scan, which revealed a significant diminution in the extent and intensity of the gradient uptake when compared to the preceding examination (

Figure 4). From a clinical perspective, there was unequivocal evidence of complete resolution of the ulcerative lesion that involved the skin, with an excellent cosmetic outcome (

Figure 5). Regarding the toxicity treatment related, the patient experienced G2 mucositis, which was resolved with topical medication.

3. Discussion

Most patients with HNSCC present with LA disease (stages III-IVB) [

7]. LA HNSCC is often curable but requires combined-modality therapy to maximize disease eradication and minimize toxicities. Each modality is uniquely difficult to deliver in older adults, who are more likely to have comorbidities, making them poor surgical candidates. They are also more vulnerable to aspiration and have lower nutritional status, which complicates the treatment delivery. They may also have a lower baseline reserve, increasing vulnerability to chemotherapy toxicity. If a patient is fit for surgery and/or RT, oncologists typically decide on therapeutic intensification strategies that have been shown to improve overall survival and locoregional recurrence. These include concomitant chemotherapy (CRT), cetuximab, and altered fractionation of RT dosing, using high conformal delivery techniques [

8]. None of these strategies has shown any survival benefit in patients over 70.

These intensification strategies may be less effective at eradicating tumors in older adults due to the biological and microenvironmental differences associated with head and neck cancers in this age group. The beneficial effects of these intensive treatment regimens are likely to be offset by toxic side effects and other non-cancer-related causes of death [

9]. Older adults with cancer, such as HNSCC, are also more likely to have comorbidities and age-related pharmacodynamics that affect the metabolism of cancer drugs [

10]. Advanced age is a strong predictor of increased late-term treatment-related toxicities in HNSCC, including aspiration pneumonia, dysphagia, and gastrostomy tube dependence, as well as non-cancer-associated mortality after CRT [

11].

SFRT, also known as GRID radiotherapy (GRT) and LRT, is an interesting radiotherapy modality to treat tumours by delivering a spatially modulated dose with highly non-uniform dose distributions. This treatment modality is of growing interest in radiation oncology, physics, and biology. There are clinical experiences that SFRT can achieve a high response and low toxicity in the treatment of refractory and bulky tumours [

12].

The first GRID therapy was performed by Mohiuddin et al [

13] in which an acerrobend block collimator (also called GRID collimator) was used, and one fraction of a large nominal dose was given before starting conventional radiation therapy. The pencil beam obtained using this collimator has a regular geometric distribution inside the target, regardless of the metabolic tumor microenvironment heterogeneity.

A further concern is that SFRT may facilitate clinical translation of the immunostimulatory effects of radiotherapy. Nevertheless, SFRT has been observed to elicit exceptional clinical responses, despite its deviation from the notes radiobiological principles. The advent of modern three-dimensional SFRT delivery techniques, such as lattice, can enhance the normal tissue sparing and safety of this treatment modality. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that these techniques may impact both the tumor and metastatic sites [

14]

.

In the present case study, the spherical deposits of high dose are allocated at the interface between regions exhibiting high metabolic activity, as determined by PET scan, and those exhibiting low metabolic activity. Our

hypothesis concerns that both the high-dose (''peak dose'') regions of SFRT and the low-dose (''valley dose'') regions can promote an immunomodulatory effect against the cancer. The high radiation dose causes damage, which activates the innate (rapid) response, including the activation of APC cells (e.g. dendritic cells) by the release of tumor-associated antigens [

15]. Conversely, low-dose radiation (i.e., 0.5–2 Gy) has been observed to modulate the tumor microenvironment (TME), inducing a shift towards M1 macrophage polarization. Consequently, iNOS-positive M1 macrophages secrete chemokines that play a key role in the recruitment of effector T cells. Moreover, these macrophages enhance the tumor vasculature and inflammation, facilitating T-cell infiltration [

16]. This treatment modality, administered before conventional therapy, has been shown to stimulate the immune system against tumor cells, thereby counteracting the immunosuppressive effects of the latter therapeutic course. This approach has been observed to promote a subsequent, slow adaptive response, which could counterbalance the immunosuppressive effect on locoregional lymph node germinal centers subjected to higher doses of radiotherapy used in standard treatments.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example in the literature that uses a metabolism-guided spatially fractionated radiotherapy (lattice-like approach) for curative purposes

The present study suggests that a heterogeneous dose distribution inside a B-GTV and in localized radioresistant areas using the SFRT can promote an anti-tumor immune response, thereby enhancing the antitumour activity of radiotherapy. The evidence indicates that LRT may be a viable therapeutic option for cases that would otherwise be challenging to manage [

17].

4. Conclusions

The present study reports on a patient with LA cheek cancer treated with SFRT with curative intent. The findings demonstrate that this combination of high “localized” doses and low-dose irradiation can produce immunological effects, and that the treatment is both feasible and safe, with an acceptable toxicity profile. Further studies are necessary to determine the validity of this therapy for this clinical scenario.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.I. and G.F.; methodology, G.I.; software, Si.Pa.; validation, G.I., Si.Pa. and St.Pe.; formal analysis, Si.Pa.; investigation, G.F.; resources, Si.Pa.; data curation, G.I.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I.; writing—review and editing, G.I.; visualization, G.F.; supervision, St.Pe.; project administration, G.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

This case report involves a human participant. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the departmental research committee. An informed consent form was obtained from the patient involved.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HNSCC |

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| RT |

Radiotherapy |

| LA |

Locally advanced |

| SFRT |

Spatially Fractionated Radiotherapy |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| AJCC |

American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| LRT |

LATTICE radiotherapy |

| cVMAT |

Conventional Volumetric Modulated Arc Radiotherapy |

| Vs |

Vertices |

| SVMAT |

Stereotactic Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy |

| B-GTV |

Bulky-Gross Tumor Volume |

| Vx |

Percentage of volume receiving any dose |

| CTV |

Clinical Target Volume |

| CNV |

Clinical nodal volume |

| Dmax |

Maximum of dose |

| Dmean |

Mean dose |

| CRT |

Chemo-radiotherapy |

| GRT |

GRID radiotherapy |

References

- Zumsteg ZS, Cook-Wiens G, Yoshida E, Shiao SL, Lee NY, Mita A, Jeon C, Goodman MT, Ho AS. Incidence of Oropharyngeal Cancer Among Elderly Patients in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, Garden AS, Weber RS, Cooper JS, Forastiere A, Ang KK. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26, 3582–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haehl E, Rühle A, David H, Kalckreuth T, Sprave T, Stoian R, Becker C, Knopf A, Grosu AL, Nicolay NH. Radiotherapy for geriatric head-and-neck cancer patients: what is the value of standard treatment in the elderly? Radiat Oncol. 2020, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yan W, Khan MK, Wu X, Simone CB 2nd, Fan J, Gressen E, Zhang X, Limoli CL, Bahig H, Tubin S, Mourad WF. Spatially fractionated radiation therapy: History, present and the future. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2019, 20, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferini G, Parisi S, Lillo S, Viola A, Minutoli F, Critelli P, Valenti V, Illari SI, Brogna A, Umana GE, Ferrantelli G, Lo Giudice G, Carrubba C, Zagardo V, Santacaterina A, Leotta S, Cacciola A, Pontoriero A, Pergolizzi S. Impressive Results after "Metabolism-Guided" Lattice Irradiation in Patients Submitted to Palliative Radiation Therapy: Preliminary Results of LATTICE_01 Multicenter Study. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bisello S, Cilla S, Benini A, Cardano R, Nguyen NP, Deodato F, Macchia G, Buwenge M, Cammelli S, Wondemagegnehu T, Uddin AFMK, Rizzo S, Bazzocchi A, Strigari L, Morganti AG. Dose-Volume Constraints fOr oRganS At risk In Radiotherapy (CORSAIR): An "All-in-One" Multicenter-Multidisciplinary Practical Summary. Curr Oncol. 2022, 29, 7021–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maggiore R, Zumsteg ZS, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Trevino KM, Gajra A, Korc-Grodzicki B, Epstein JB, Bond SM, Parker I, Kish JA, Murphy BA, VanderWalde NA; CARG-HNC Study Group. The Older Adult With Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Knowledge Gaps and Future Direction in Assessment and Treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017, 98, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pontoriero A, Iatì G, Aiello D, Pergolizzi S. Stereotactic Radiotherapy in the Retreatment of Recurrent Cervical Cancers, Assessment of Toxicity, and Treatment Response: Initial Results and Literature Review. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2016, 15, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michal SA, Adelstein DJ, Rybicki LA, Rodriguez CP, Saxton JP, Wood BG, Scharpf J, Ives DI. Multi-agent concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer in the elderly. Head Neck. 2012, 34, 1147–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi D, Barzan L, Franchin G, Cinelli R, Balestreri L, Tirelli U, Vaccher E. Treatment of head and neck cancer in elderly patients: state of the art and guidelines. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005, 53, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiris A, Brockstein BE, Haraf DJ, Stenson KM, Mittal BB, Kies MS, Rosen FR, Jovanovic B, Vokes EE. Competing causes of death and second primary tumors in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 1956–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Wu X. Which Modality of SFRT Should be Considered First for Bulky Tumor Radiation Therapy, GRID or LATTICE? Semin Radiat Oncol. 2024, 34, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin M, Fujita M, Regine WF, Megooni AS, Ibbott GS, Ahmed MM. High-dose spatially fractionated radiation (GRID): a new paradigm in the management of advanced cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999, 45, 721–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan MT, Khan AJ, Powell SN, Humm J, Deasy JO, Haimovitz-Friedman A. Spatially Fractionated Radiotherapy in the Era of Immunotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2024, 34, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carvalho HA, Villar RC. Radiotherapy and immune response: the systemic effects of a local treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018, 73 (Suppl. 1), e557s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herrera FG, Ronet C, Ochoa de Olza M, Barras D, Crespo I, Andreatta M, Corria-Osorio J, Spill A, Benedetti F, Genolet R, Orcurto A, Imbimbo M, Ghisoni E, Navarro Rodrigo B, Berthold DR, Sarivalasis A, Zaman K, Duran R, Dromain C, Prior J, Schaefer N, Bourhis J, Dimopoulou G, Tsourti Z, Messemaker M, Smith T, Warren SE, Foukas P, Rusakiewicz S, Pittet MJ, Zimmermann S, Sempoux C, Dafni U, Harari A, Kandalaft LE, Carmona SJ, Dangaj Laniti D, Irving M, Coukos G. Low-Dose Radiotherapy Reverses Tumor Immune Desertification and Resistance to Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferini G, Valenti V, Tripoli A, Illari SI, Molino L, Parisi S, Cacciola A, Lillo S, Giuffrida D, Pergolizzi S. Lattice or Oxygen-Guided Radiotherapy: What If They Converge? Possible Future Directions in the Era of Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).