Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

05 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

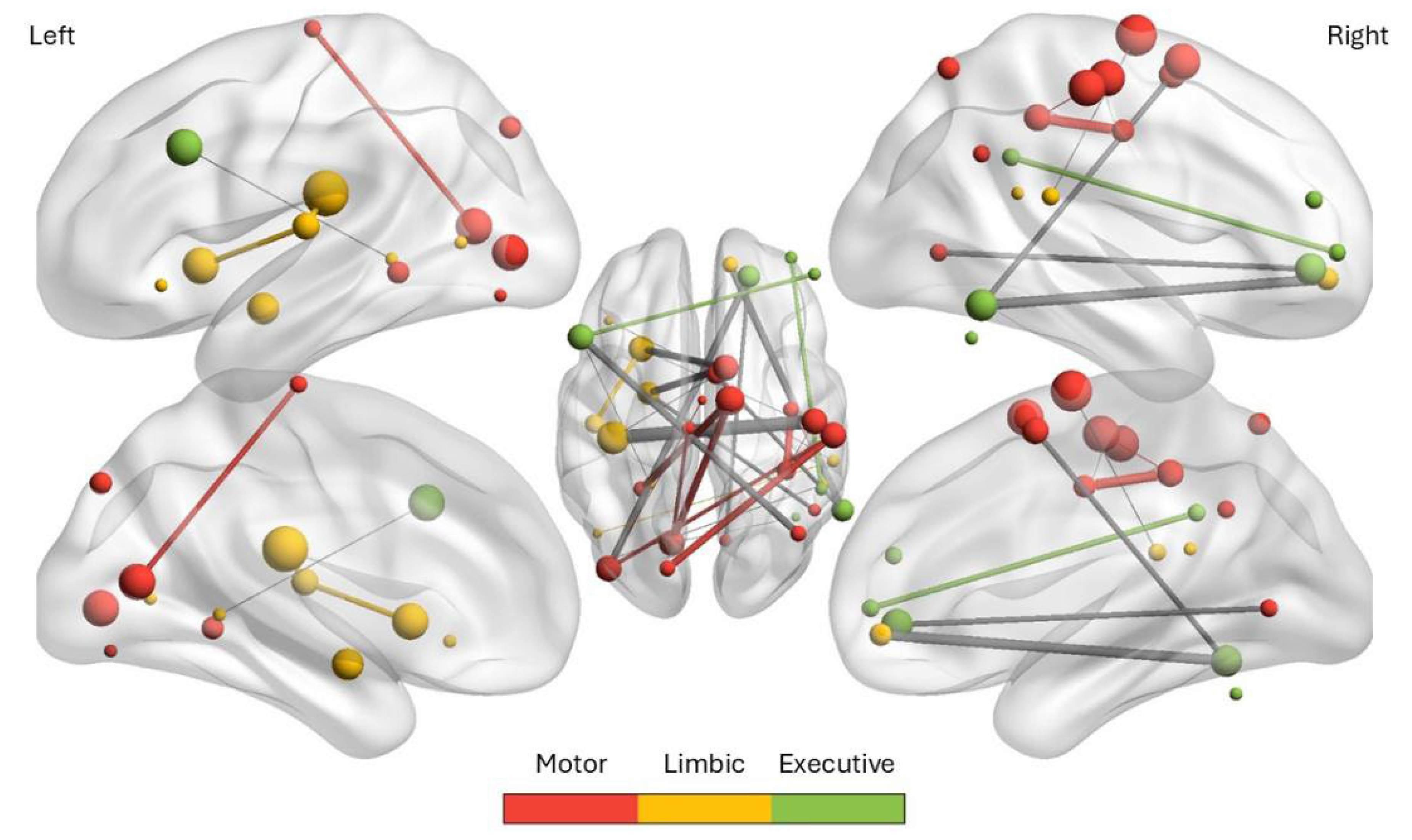

2. Distinctive Connectivity Patterns Underlying Functional Movement Disorders

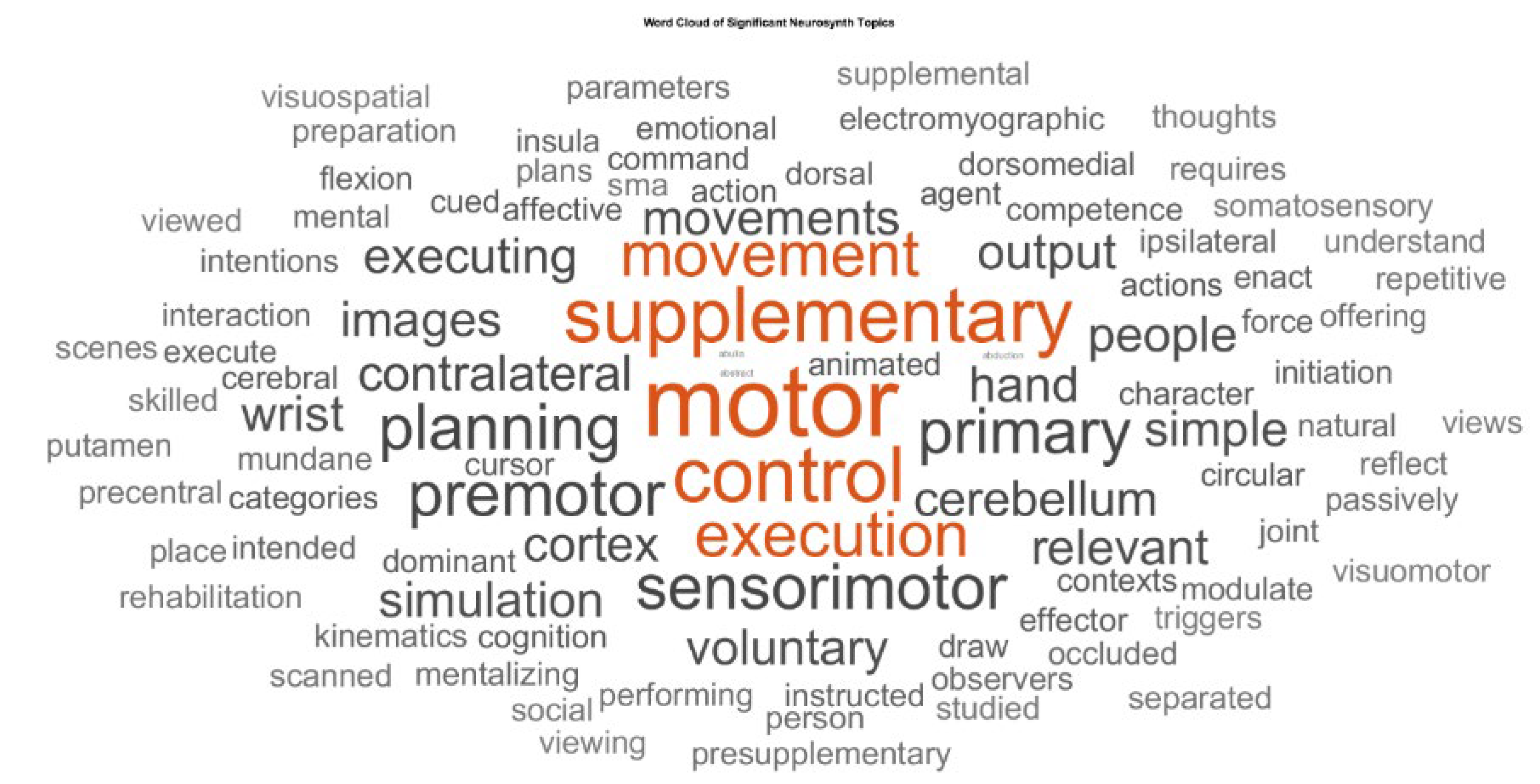

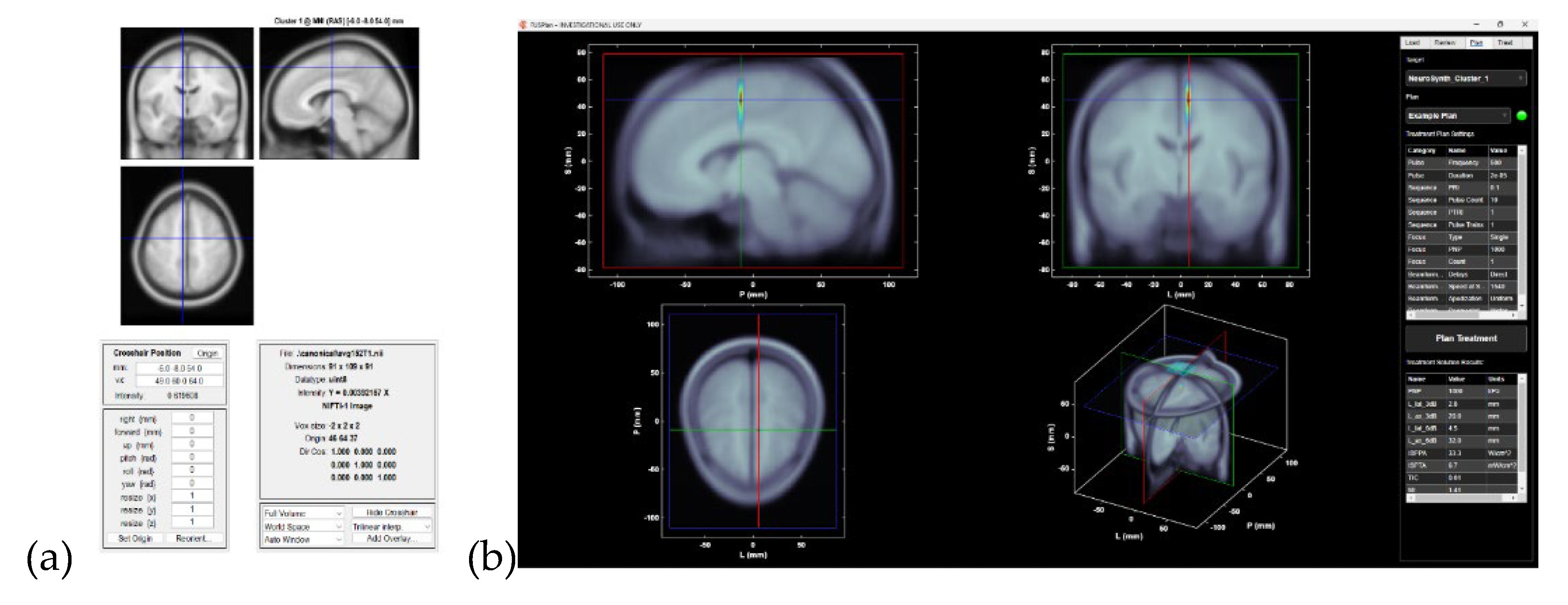

3. Meta-Analysis By Linking Neurosynth Studies To Subnetworks To Guide Ultrasond Neuromodulation

4. Action-Mode Network In Relation To SCAN For Neuromodulation

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

References

- E. M. Gordon et al., ‘A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex’, Nature, vol. 617, no. 7960, pp. 351–359, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. U. F. Dosenbach, M. E. N. U. F. Dosenbach, M. E. Raichle, and E. M. Gordon, ‘The brain’s action-mode network’, Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 158–168, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, ‘Neurocomputational Mechanisms of Sense of Agency: Literature Review for Integrating Predictive Coding and Adaptive Control in Human–Machine Interfaces’, Brain Sciences, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 396, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. Roelofs, ‘Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 372, no. 1718, p. 20160206, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Porges, ‘Orienting in a defensive world: mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory’, Psychophysiology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 301–318, Jul. 1995. [CrossRef]

- A. Milano, M. A. Milano, M. Moutoussis, and L. Convertino, ‘The neurobiology of functional neurological disorders characterised by impaired awareness’, Front. Psychiatry, vol. 14, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Weber, J. Bühler, T. A. W. Bolton, and S. Aybek, ‘Altered brain network dynamics in motor functional neurological disorders: the role of the right temporo-parietal junction’, Transl Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 167, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Ren et al., ‘The somato-cognitive action network is the core neuromodulation target in Parkinson’s disease’, Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 523–524, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Das and, A. Dutta, ‘Functional seizure therapy via transauricular vagus nerve stimulation’, Medical Hypotheses, vol. 191, p. 111462, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , ‘Extended Reality Biofeedback for Functional Upper Limb Weakness: Mixed Methods Usability Evaluation’, JMIR XR and Spatial Computing (JMXR), vol. 2, no. 1, p. e68580, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Waugh, J. A. R. E. Waugh, J. A. Parker, M. Hallett, and S. G. Horovitz, ‘Classification of Functional Movement Disorders with Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging’, Brain Connect, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 4–14, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Stone, A. J. Stone, A. Zeman, and M. Sharpe, ‘Functional weakness and sensory disturbance’, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, vol. 73, no. 3, pp. 241–245, Sep. 2002. [CrossRef]

- V. Voon et al., ‘Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder’, Brain, vol. 133, no. 5, pp. 1526–1536, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Grippe, N. T. Grippe, N. Desai, T. Arora, and R. Chen, ‘Use of non-invasive neurostimulation for rehabilitation in functional movement disorders’, Front Rehabil Sci, vol. 3, p. 1031272, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Maurer, K. W. Maurer, K. LaFaver, R. Ameli, S. A. Epstein, M. Hallett, and S. G. Horovitz, ‘Impaired self-agency in functional movement disorders’, Neurology, vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 564–570, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Badke, D’Andrea; et al. , ‘Action-mode subnetworks for decision-making, action control, and feedback’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 122, no. 27, p. e2502021122, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Yarkoni, R. A. T. Yarkoni, R. A. Poldrack, T. E. Nichols, D. C. Van Essen, and T. D. Wager, ‘Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data’, Nat Methods, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 665–670, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Poldrack, J. A. R. A. Poldrack, J. A. Mumford, T. Schonberg, D. Kalar, B. Barman, and T. Yarkoni, ‘Discovering Relations Between Mind, Brain, and Mental Disorders Using Topic Mapping’, PLOS Computational Biology, vol. 8, no. 10, p. e1002707, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Bawiec et al., ‘A Wearable, Steerable, Transcranial Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound System’, J Ultrasound Med, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 239–261, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- ‘SPM - Statistical Parametric Mapping’. Accessed: Jun. 17, 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.

- M. Gordon et al., ‘A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex’, Nature, vol. 617, no. 7960, pp. 351–359, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Dum, D. J. R. P. Dum, D. J. Levinthal, and P. L. Strick, ‘Motor, cognitive, and affective areas of the cerebral cortex influence the adrenal medulla’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 35, pp. 9922–9927, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Gilmour et al., ‘Management of functional neurological disorder’, J Neurol, vol. 267, no. 7, pp. 2164–2172, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Dosenbach, M. N. Dosenbach, M. Raichle, and E. Gordon, ‘The brain’s cingulo-opercular action-mode network’, Jan. 27, 2024, OSF. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, ‘”Hyperbinding” in functional movement disorders: role of supplementary motor area efferent signalling’, Brain Communications, vol. 7, no. 1, p. fcae464, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Desmurget and A. Sirigu, ‘Revealing humans’ sensorimotor functions with electrical cortical stimulation’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 370, no. 1677, p. 20140207, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Ospina, R. J. P. Ospina, R. Jalilianhasanpour, and D. L. Perez, ‘The Role of the Anterior and Middle Cingulate Cortices in the Neurobiology of Functional Neurological Disorder’, Handb Clin Neurol, vol. 166, pp. 267–279, 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Breton-Provencher, G. T. V. Breton-Provencher, G. T. Drummond, and M. Sur, ‘Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine in Learned Behavior: Anatomical Modularity and Spatiotemporal Integration in Targets’, Front. Neural Circuits, vol. 15, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Miall, D. J. R. C. Miall, D. J. Weir, D. M. Wolpert, and J. F. Stein, ‘Is the cerebellum a smith predictor?’, J Mot Behav, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 203–216, Sep. 1993. [CrossRef]

- A. Monti, N. A. Monti, N. Wintering, F. Vedaei, A. Steinmetz, F. B. Mohamed, and A. B. Newberg, ‘Changes in brain functional connectivity associated with transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in healthy controls’, Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 19, p. 1531123, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).