1. Introduction

Achieving carbon neutrality has emerged as the core strategic objective for nations to combat climate change. Among various emission reduction strategies, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology serves as a critical pillar for deep decarbonization and net-zero emissions, particularly for high-emission sectors (e.g., steel, cement, and thermal power industries) (Dos Santos, 2024, Hammed et al., 2023, International Energy Agency, 2023, Rockström et al., 2017). Authoritative bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) emphasize that realizing global carbon neutrality by mid-century requires scaling CCUS deployments at least fivefold by 2030 (Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change, 2022, International Energy Agency, 2023). However, CCUS systems entail complex couplings of capture, conversion, transportation, and geological storage processes, characterized by multi-physical field, multi-scale, and multidisciplinary complexities. Traditional engineering modeling approaches increasingly face performance bottlenecks in addressing nonlinear couplings and system uncertainties (Kelemen et al., 2019, Mim et al., 2023). This challenge necessitates leveraging next-generation data-driven intelligent technologies to develop solutions for system optimization, collaborative integration, and predictive control.

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) in engineering science and energy systems, its integration with CCUS has emerged as a focal research area, forging a multi-level, multi-dimensional interdisciplinary research landscape. Numerous studies have applied data-driven approaches—including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL)—to model critical CCUS tasks, such as predicting adsorption performance in CO₂ capture, optimizing carbon conversion reaction pathways, performing nonlinear inversion in reservoir simulations, and forecasting storage safety via time-series analysis (Bui et al., 2018, Liu et al., 2023, Xiao et al., 2024, Zheng et al., 2023). At the scenario level, AI has been widely deployed across key engineering processes, including high-throughput screening of novel adsorbents like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) (Choudhary et al., 2022, Li et al., 2024), modeling CO₂ plume migration and leakage risks in reservoirs, and predicting carbon market dynamics—significantly enhancing modeling efficiency and system sensing capabilities (Manna et al., 2025, Shin et al., 2025). Recent advancements have seen the integration of emerging AI techniques—such as graph neural networks (GNN), physics-informed neural networks (PINN), digital twins, and multimodal architectures—driving AI's evolution from an "auxiliary modeling tool" to a "systemic collaboration hub" (D'Elia et al., 2022, Liu et al., 2025, Ma et al., 2024, Wang et al., Yan et al., 2022). Researchers are now focusing on frontiers like multi-source heterogeneous data fusion, interpretable model development, and frameworks for integrating AI with geoscientific knowledge, forming a rich "algorithm-scene-system" integration landscape that provides the technical foundation for AI to empower CCUS at scale.

Despite significant advances in "AI+CCUS" interdisciplinary research, the current framework faces multi-faceted challenges that demand systematic and integrated solutions. Methodologically, most AI models remain black-box architectures, lacking embedding of physical constraints and geological boundary conditions, which compromises model interpretability, restricts generalization, and limits applicability to high-risk, strongly coupled engineering scenarios (Karniadakis et al., 2021). CCUS tasks often involve high-dimensional integration of nonlinear multiphase flow, complex subsurface structures, and multi-source heterogeneous data, where traditional data-driven models exhibit performance degradation under data sparsity, spatiotemporal discontinuities, and scenario transfer (Zhao et al., 2024). A critical challenge is the "semantic gap" between AI modeling and geoscientific knowledge representation—most algorithms cannot adequately access or integrate geoscientific ontologies (e.g., reservoir mechanics, storage mechanisms), hindering deep cognitive integration and abstract reasoning in engineering contexts (Sun et al., 2022). Additionally, large-scale CCUS deployment lacks AI-aligned standardized modeling frameworks, safety assessment protocols, and policy-regulatory interfaces, restricting AI applications to experimental validation rather than supporting closed-loop engineering optimization (Asere et al., 2025, Yao et al., 2023, Zhang et al., 2025). Thus, while "AI+CCUS" research is booming, critical gaps persist in fundamental theory, model architecture, and system deployment, necessitating the development of an integration paradigm with physical consistency, cognitive generality, and operational transferability.

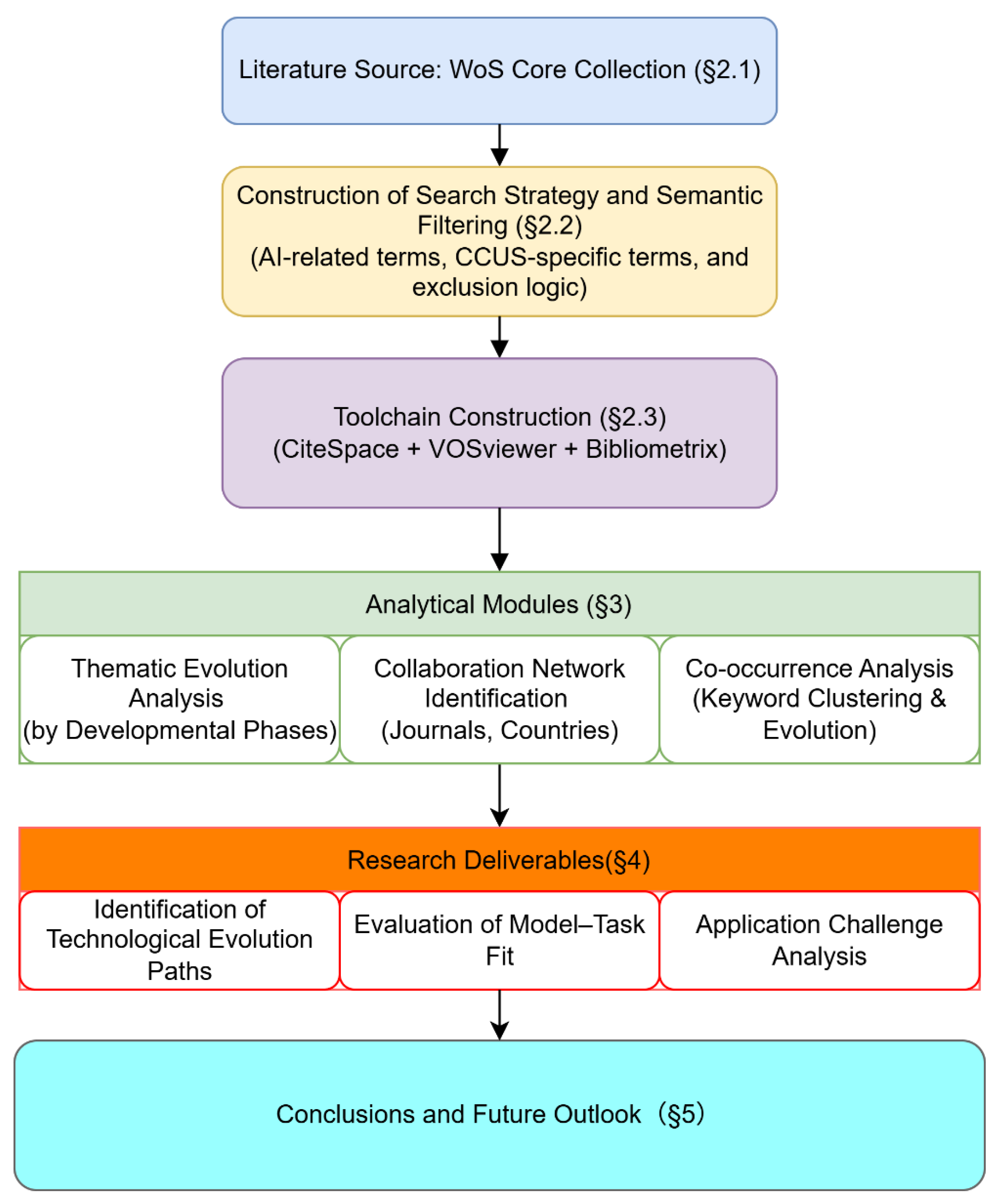

To tackle the aforementioned challenges, this study investigates the "evolutionary pathway of AI-empowered CCUS systems", aiming to systematically map AI’s developmental trajectory, core technical landscape, and collaborative integration routes across CCUS segments, while deciphering its evolutionary patterns and methodological transfer mechanisms. We constructed a multi-dimensional dataset of AI+CCUS literature (2001–2025) from the Web of Science Core Collection, leveraging bibliometric tools (CiteSpace, VOSviewer, Bibliometrix) to establish cross-disciplinary knowledge graphs and term evolution networks for identifying research hotspots, stage-specific characteristics, and systemic architectures. The research comprises four core modules: (1) Stage division: Proposing a four-stage model—"instrumental adoption, task integration, methodological breakthrough, systemic collaboration"—based on publication and citation trends; (2) Technical analysis: Mapping the task-specific application trajectories of mainstream AI algorithms (ANN, ML, DL, GNN, PINN, Transformer) across key CCUS processes; (3) Policy-technology synergy: Constructing synchronic relationships between technological advancements and policy milestones (IPCC reports, Paris Agreement, dual-carbon targets); (4) Challenges and outlook: Identifying critical bottlenecks (data heterogeneity, model interpretability, knowledge representation gaps) and proposing future integration modeling/deployment roadmaps. Distinct from previous single-model assessments or case studies, this work emphasizes full-chain AI empowerment at the CCUS system level, focusing on dynamic synergies among technological evolution, scenario expansion, and cognitive coupling to provide data-driven frameworks for an AI-anchored CCUS integration paradigm.

Collectively, this study makes four key contributions: First, methodologically, it establishes a stage classification model for AI-empowered CCUS evolution, identifying four developmental phases—"preliminary tool adoption, multi-scene integration, collaborative modeling, and systemic fusion"—thereby addressing the absence of a full-cycle evolutionary framework. Second, conceptually, it constructs a three-dimensional co-evolutionary landscape integrating algorithmic advancements, research objectives, and policy milestones, uncovering the synergistic coupling between AI paradigm shifts (ANN/ML/DL→GNN/PINN/LLM) and climate policy trajectories (IPCC reports, Paris Agreement). Third, application-wise, it systematically identifies core bottlenecks in AI+CCUS—data scarcity, black-box limitations, knowledge integration gaps, and deployment standardization—and proposes four research directions: open-data infrastructure, physics-constrained modeling, semantic knowledge graph construction, and end-to-end deployment frameworks. Finally, perspectively, it elevates AI from a localized tool to a core collaborative layer for CCUS system modeling, emphasizing its strategic role in enabling intelligent decision-making for complex energy-geoscience systems. This work provides both theoretical foundations and a systematic roadmap for an "expandable, interpretable and deployable" AI-CCUS research paradigm.

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

To systematically map the knowledge evolutionary trajectory and technological integration trends of AI in CCUS, this study constructed a structured literature search strategy for cross-disciplinary themes, forming the basis for data analysis. All literature data were sourced from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS Core Collection), with the search deadline set as May 11, 2025. No restrictions were applied to document types or publication years to ensure comprehensive coverage of frontier research dynamics in interdisciplinary fields.

The search query design integrated mainstream AI terminology with core CCUS engineering segments to enhance thematic focus and technical representational capability. AI-related keywords encompassed learning paradigms (e.g., "artificial intelligence", "machine learning", "deep learning", "neural network", "reinforcement learning", "transfer learning") as well as model-specific terms (e.g., "support vector machine", "graph neural network", "XGBoost", "transformer", "digital twin", "large language model", "pretrained language model", "ChatGPT"). CCUS-related terms were structured around the "capture-utilization-storage-monitoring" workflow, including scene-specific phrases (e.g., "CO₂ capture", "chemical looping", "mineral carbonation", "geological storage", "saline aquifer", "CO₂ plume monitoring", "carbon mineralization") to ensure semantic alignment with engineering practice.

Given the high interdisciplinarity of AI and CCUS terminology with substantial semantic overlap, there is a risk of semantic drift and ambiguity-induced interference. This paper introduces a threefold control framework to enhance retrieval precision and semantic binding: (1) Keyword co-occurrence constraint: For easily confused abbreviations (e.g., "DAC", "CCS", "ML"), entries are included in the sample only when co-occurring with "CO₂" or "carbon"-related vocabulary. For example, "pressure monitoring" is retained only if accompanied by "CO₂ plume" or "geological storage"; (2) Logical exclusion filtering (NOT): For high-frequency yet irrelevant semantic clusters (e.g., "soil organic carbon", "biodiversity modeling", "fuel cell"), Boolean logic is employed to exclude content from peripheral disciplines (e.g., agriculture, ecology, medicine); (3) Manual feedback refinement mechanism: During initial retrieval, interference items are manually validated via batch-exported samples, and the retrieval formula is iteratively optimized to significantly enhance retrieval accuracy and topic coherence.

Given the high interdisciplinarity of AI and CCUS terminology, which introduces risks of semantic drift and ambiguous interpretations, this study implemented a threefold control mechanism to enhance search precision and semantic rigor: (1) Keyword co-occurrence constraint: Ambiguous abbreviations (e.g., "DAC", "CCS", "ML") were included only if co-occurring with "CO₂"/"carbon" keywords (e.g., "pressure monitoring" was retained only when paired with "CO₂ plume" or "geological storage"); (2) Logical exclusion (NOT operator): High-frequency but irrelevant terms (e.g., "soil organic carbon", "biodiversity modeling", "fuel cell") were filtered using Boolean logic to exclude non-CCUS disciplines (agriculture, ecology, medicine); (3) Manual feedback iteration: Initial search results were manually screened in batches to identify false positives, enabling iterative refinement of the search query and improving thematic focus.

2.2. Data Analysis Tools and Methods

To comprehensively map the evolutionary trajectory and structural features of AI in CCUS, this study constructed a composite knowledge graph analytical framework featuring three mainstream tools—VOSviewer, CiteSpace, and Bibliometrix. Grounded in bibliometric principles, the framework integrates network modeling, cluster analysis, hotspot detection, and visualization capabilities to synergistically uncover the technical pathways and epistemic evolution of AI+CCUS interdisciplinary research across three dimensions: micro-level terminology, meso-level structural patterns, and macro-level trend dynamics.

First, as a core tool for structural clustering and network construction, VOSviewer was employed to model collaborative networks among authors, institutions, and national research entities, identifying core research teams and international collaboration patterns in AI+CCUS studies (Wong, 2018). Leveraging its Overlay Visualization module, we further constructed keyword temporal diffusion maps to characterize the penetration pathways and hotspot dynamics of mainstream AI approaches (ML, DL, PINN, GNN) across CCUS subdomains.

Second, CiteSpace was employed to identify research frontiers and high-impact publication nodes (Chen, 2016). In this study, it facilitated multi-dimensional analyses of highly cited publications, citation bursts, and author bursts, enabling the identification of critical breakthroughs and paradigm shifts in AI applications for CCUS. Through Timezone View and Burst Detection, we uncovered the evolutionary trajectory of CCUS research paradigms—from early modeling aids to systemic collaborative hubs.

Third, Bibliometrix—an R platform-based open bibliometric framework—offers flexible statistical modeling and multi-field cross-structure identification capabilities (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017). In this study, it was used to analyze publication trends, identify highly cited authors and institutions, and construct visualizations including a Three Field Plot (author-keyword-journal interactions), Thematic Evolution Map, and Word Growth Map, enabling characterization of knowledge coupling between AI and CCUS. Leveraging its Geopolitical Map function, we mapped research focuses of major nations across CCUS technical segments and cross-regional collaboration patterns.

The knowledge graph analytical framework—constructed synergistically with the three tools—established a fusion paradigm of "structural visualization, data semantic mining, and multi-scale integrated modeling", significantly enhancing the capability to analyze the complex AI+CCUS interdisciplinary system. In comparison to traditional literature review methods, this systematic methodology not only facilitates deeper awareness of semantic structures and evolutionary tracking but also provides systematic support for identifying critical challenges and formulating future research roadmaps (

Figure 1).

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Stage Division

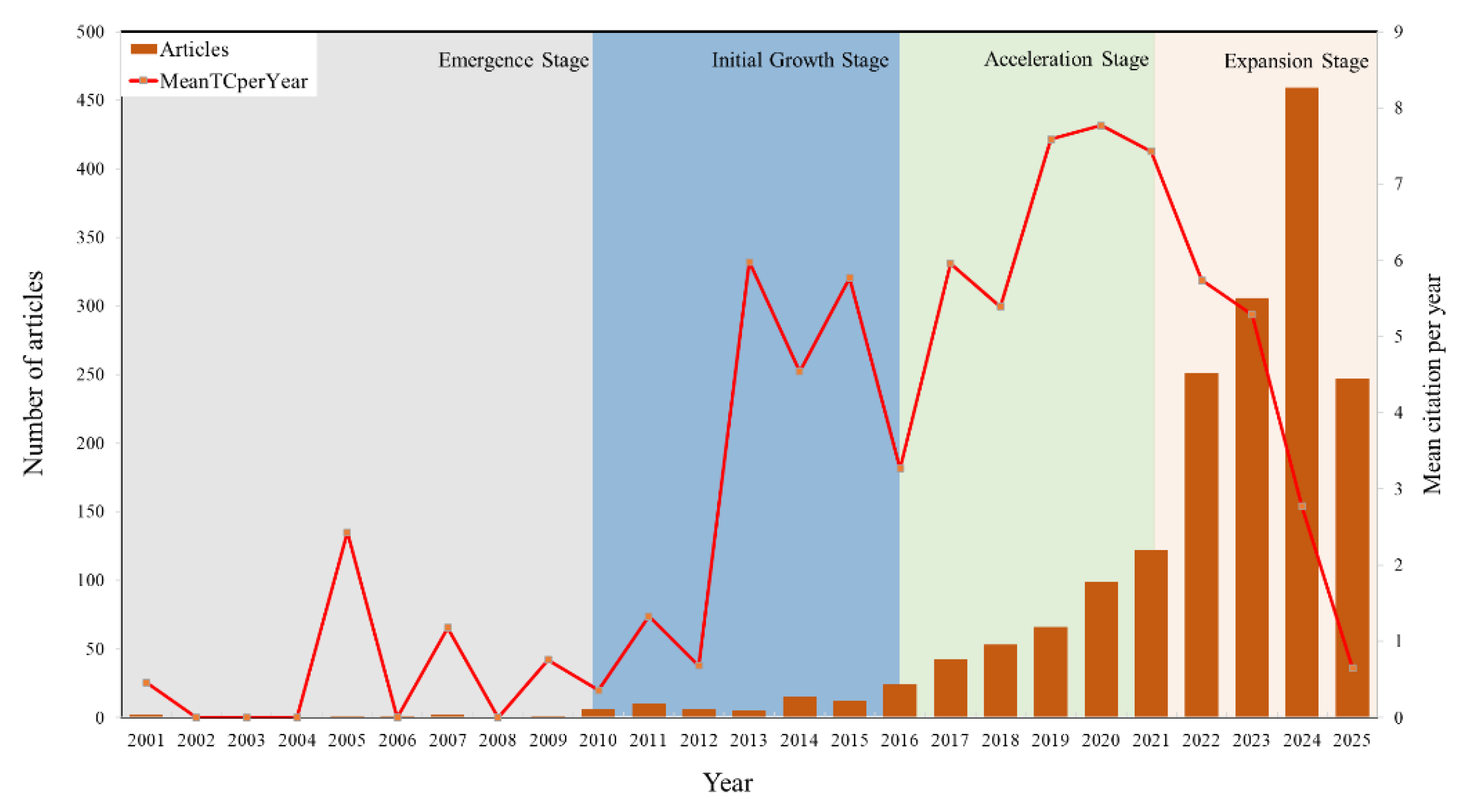

To systematically map the evolutionary trajectory of AI in CCUS, we developed a time-series analytical framework based on two metrics: annual articles and mean annual citation frequencies (MeanTCperYear). Integrating algorithmic development cycles, engineering application demands, and global climate policy milestones, we identified four developmental phases of AI+CCUS research: Emergence stage (2001–2010), Initial growth stage (2011–2016), Accelerating Stage (2017–2020), and Expansion Stage (2021–2024) (

Figure 2).

During the Emergence stage (2001–2010), AI+CCUS research remained in its infancy, with annual publication counts below 10 and low citation rates, indicating an immature knowledge base. Research focused on geological storage feasibility assessment and reservoir parameter identification, with AI first applied to small-sample modeling as an auxiliary computational tool. Shallow models like support vector machines (SVM), artificial neural networks (ANN), and random forests (RF) were used for CO₂ adsorption material prediction and parameter inversion, though hampered by data scarcity and computational constraints(Liu et al., 2001, Xiang, 2009). The 2005 IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage—which first integrated CCUS into global climate governance frameworks—marked a key policy impetus for AI adoption in CCUS engineering (Metz et al., 2005).

During the Initial growth stage (2011–2016), research momentum stabilized with annual publications rising to double digits, driven by advancing engineering pilot projects. CCUS initiatives like SACROC (US) and Sleipner (Norway) demanded higher precision in geological reservoir modeling, spurring AI model advancements in formation parameter inversion and storage stability prediction (Shahkarami et al., 2015, Zhang and Agarwal, 2014). Structural models (CNN, XGBoost) were progressively applied to feature extraction and multi-field coupling tasks, enhancing computational efficiency and model robustness (Jordan and Mitchell, 2015, Paris-Saclay et al., Weimer et al., 2016, Wuest et al., 2016, Zhao et al., 2016). The 2015 Paris Agreement—establishing global carbon neutrality targets—prompted national carbon reduction strategies, thereby accelerating AI integration with carbon capture management (Paris Agreement, 2015).

During the Accelerating Stage (2017–2020), research intensity surged, with annual publications increasing from 42 (2017) to 99 (2020) and mean citations rising steeply. Larger-scale CCUS projects and improved data acquisition enabled exploration of expressive deep learning frameworks. Deep neural networks (DNN), GNN, and PINN were applied to critical tasks—reservoir multiphase flow simulation, CO₂ plume migration modeling, and anomaly detection—with some models replacing traditional numerical methods for core simulations (Alakeely and Horne, 2020, Huntingford et al., 2019). Notably, PINN integrated data-driven approaches with physical consistency by incorporating geological boundary constraints and governing equations (Jin et al., 2019). Meanwhile, demands for fusing multi-source remote sensing, logging, and seismic data spurred the development of multi-modal learning architectures. The 2020 launch of China’s dual carbon goals, alongside the EU Green Deal and North American fiscal incentives, marked a new era of global policy coordination.

The Expansion Stage (2021–2024) has seen exponential growth in AI+CCUS research, with annual publications hitting 306 (2023) and 459 (2024)—signaling a paradigm shift from methodological exploration to systemic integration. Here, AI has evolved beyond modeling tools to become the technological backbone for system coordination, strategic optimization, and process control. Cutting-edge applications include large language models (LLM) for literature reasoning and knowledge extraction, digital twin integration for CCUS process simulation and real-time control, and multi-modal perception model deployments in material screening, carbon price forecasting, and anomaly detection (Han et al., 2025, Wang et al., 2024). Industrial implementations like Canada’s Quest CCS Project have adopted AI-assisted injection-production monitoring systems, while edge computing and IoT integrations into CCUS architectures are fostering the development of preliminary intelligent carbon cycle systems (Bielka, 2023, Hasan et al., 2022, Ma et al., 2024).

In conclusion, AI development in CCUS has followed an evolutionary trajectory from instrumental application to systemic collaboration. Algorithmic paradigm shifts, scenario migrations, and policy drivers across periods have collectively shaped the evolutionary mainstream of the AI+CCUS technology spectrum and knowledge ecosystem. The subsequent section will explore its knowledge dissemination architecture and interdisciplinary positioning through the lens of academic journals and research platforms.

3.2. Journal Distribution

Journal distribution analysis serves as a pivotal approach for characterizing the knowledge architecture and disciplinary affiliations of a research domain, enabling the revelation of research dissemination patterns of AI in CCUS, identification of mainstream academic platforms, and tracking of interdisciplinary evolution trends. To systematically map the knowledge dissemination ecosystem of AI+CCUS interdisciplinary research, this study statistically analyzed publication counts and citation frequencies of journals using a Web of Science Core Collection literature sample. By employing the Bradford core zone classification method, we conducted hierarchical analysis of journal knowledge-carrying structures to identify agglomeration trends and diffusion pathways of research paradigms.

In terms of publication counts, AI+CCUS research predominantly appears in applied journals of energy, chemical, and geological engineering, reflecting a strong engineering problem orientation. Analysis shows that 2001–2024 literature spans over 300 journals, with top performers including

Journal of Cleaner Production (60 articles),

Fuel (52),

Energy (51),

Energies (38),

Applied Energy (36), and

Geoenergy Science and Engineering (34)—among others (

Table 1). These journals focus on sustainable energy systems, carbon reduction engineering approaches, and subsurface geological process modeling, indicating that AI methods primarily serve as technical tools embedded in specific CCUS contexts rather than driving independent algorithm-focused research trajectories.

In citation analysis, energy and engineering general journals occupy a central role in knowledge diffusion and methodological influence building. Applied Energy leads with 2,570 total citations, followed by

Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research (2,231),

Fuel (2,078), and

Energy (1,880)—among others (

Table 1). These high-impact journals not only feature seminal AI-CCUS integration studies but also facilitate the dissemination of key modeling techniques and advancement of system optimization paradigms. Notably, Applied Energy and Energy—ranking top five in both publication counts and citations—embody a bridging role in the "AI-empowered energy system modeling" research agenda.

Application of Bradford's law for core zone classification (

Table 2) identified Zone 1 core journals comprising flagship titles in energy science, chemical engineering, environmental, and geological engineering—including Journal of Cleaner Production, Fuel, Applied Energy, and

Geoenergy Science and Engineering. These journals collectively account for over 60% of research outputs and citation density, forming a highly concentrated knowledge source. Notably, core journals exhibit functional specialization across CCUS technical segments: Fuel focuses on CO₂ adsorption/capture modeling,

Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research emphasizes reaction pathway design and CCU engineering, while

Geoenergy Science and Engineering specializes in geological reservoir modeling and storage simulation. This journal-based "function-oriented knowledge node architecture" signals the emergence of a specialized division of labor in AI+CCUS systematic modeling.

Notably, despite AI algorithmic innovation being a key driver, pure computer science journals focusing on algorithmic mechanisms and theoretical advances (e.g., Neural Networks, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems) exhibit low publication and citation rates. This indicates that AI research in CCUS remains dominated by "engineering demand-driven embedded modeling", with findings primarily published in traditional CCUS parent discipline journals rather than diffusing to AI core platforms focused on methodological frontiers. This trend reflects AI's technical migration pathway in energy engineering but may hinder bidirectional cross-disciplinary knowledge flow and the penetration rate of advanced AI technologies.

In conclusion, journal distribution in AI+CCUS exhibits a typical "annular knowledge structure" with engineering-technical journals as the core and AI methods journals as auxiliaries. Application-oriented energy journals (e.g., Applied Energy, Energy, Fuel, Journal of Cleaner Production) form the knowledge dissemination core, undertaking dual roles in CCUS system modeling and AI method integration. This distribution pattern not only reflects the engineering-driven nature of CCUS research but also illuminates the evolutionary path of AI technology—from "auxiliary computation" to "systemic support" in carbon reduction—providing a communication studies perspective for analyzing integration mechanisms across interdisciplinary paradigms.

3.3. National Research Landscape and Collaboration Networks

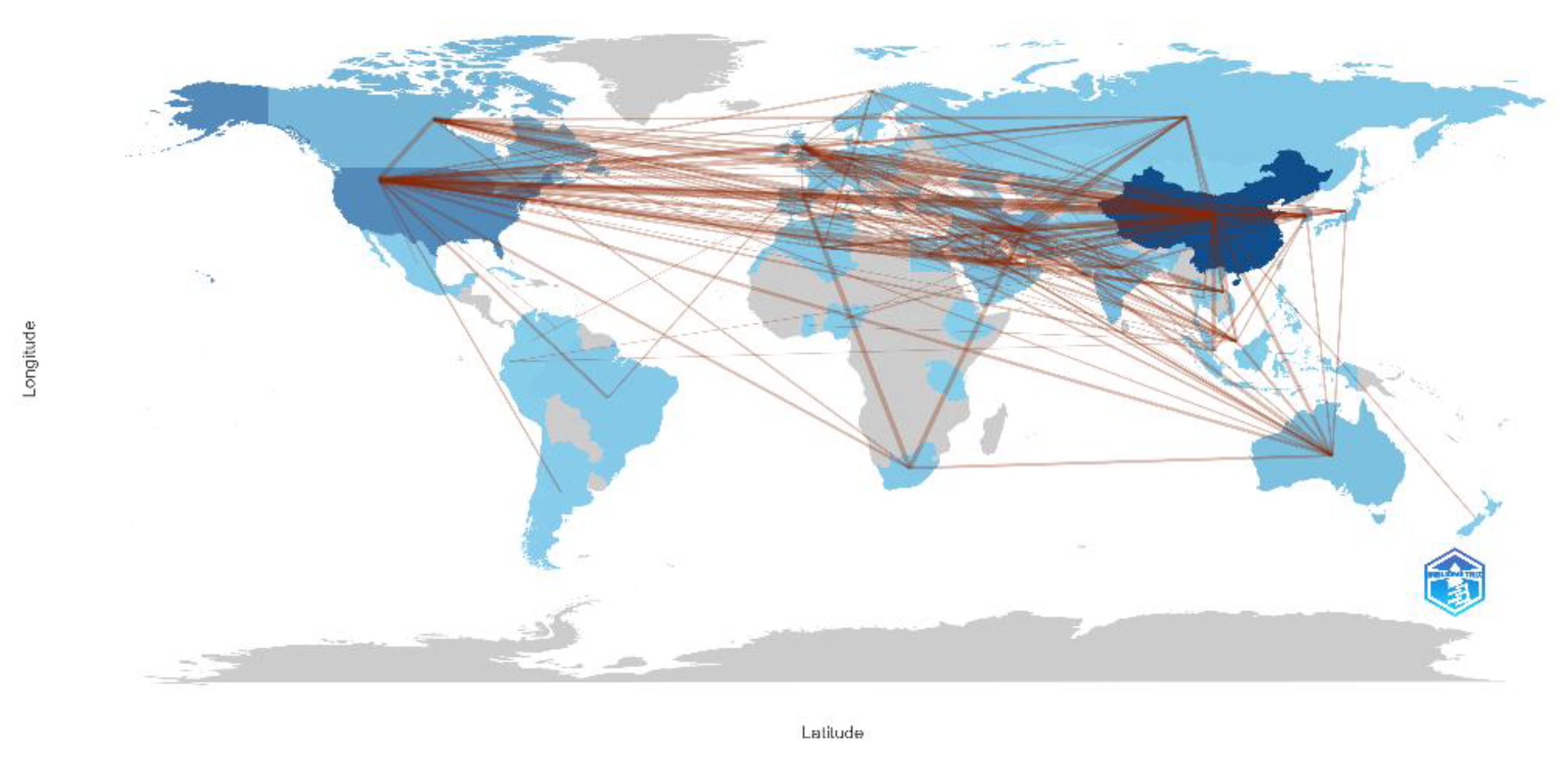

With the expanding integration of AI and CCUS research, nations have assumed distinct roles in research output, methodological innovation, and international collaboration, forming a typical "multi-center-multi-scale" knowledge diffusion framework. To map the global research landscape, this study conducts statistical analyses across four dimensions—national publication counts, total citations, citations per article, and international collaboration rate (MCP)—and integrates research stage classifications with collaboration network mapping to quantify research activity and cooperative structures among leading research nations.

In terms of publication counts (

Table 3), China led globally with 640 articles (37.0% of the total) during the sample period, demonstrating robust research output capability. However, its 26.4% MCP lagged slightly behind the U.S. and European nations, indicating a research focus on endogenous tasks and localized technology deployment with scenario-specific adaptation

(Chen et al., 2022, Chen et al., 2023, Cheng et al., 2024, Ren et al., 2023) . The U.S. ranked second with 242 publications and a high 25.3 citations per article, underscoring its core influence in model algorithm development and research paradigm formation. Countries like Canada, the UK, and South Korea—characterized by high MCP—developed multilateral collaboration-oriented research ecosystems, producing synergistic outcomes that integrated engineering adaptation with methodological innovation (Du et al., 2023, Manikandan et al., 2025, Ren et al., 2023, Seabra et al., 2024, Seabra et al., 2024).

Stage-based analysis (

Table 4) reveals distinct "functional heterogeneity" among nations in AI+CCUS development. China demonstrates a "late-start—fast-growth—task-intensive" leapfrog trajectory, focusing on CO₂ storage, plume modeling, and system integration. The U.S. exhibits a "early-lead—sustained-stability—systematic-collaboration" dominance pattern, leveraging first-mover advantages in methodological frontiers, technical integration, and platform development. Developing countries like Iran and India follow a "regionally-concentrated—locally-collaborative" model, aligning research with energy security, resource optimization, and local model adaptation. Meanwhile, the UK and Canada—backed by policy platforms and international funding—have established "high-collaboration—high-precision" research ecosystems (Delpisheh et al., 2024, Hamed and Shirif, 2025, Ma et al., 2025, Zingaro et al., 2025).

Figure 3 depicts the international collaboration network of global AI+CCUS research, where dark-shaded countries denote high-publication hubs and connecting lines signify cross-national co-authorship. Topologically, China, the U.S., UK, Germany, and Australia emerge as core nodes, forming a "multi-center-high-density" cooperative backbone spanning Asia, Europe, and North America. Bilateral collaboration between China and the U.S. is most prominent, driving collaborative diffusion to the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and beyond; as an EU representative, the UK exhibits high connectivity and brokerage roles, enhancing research integration and methodological transfer across Eurasia; while Australia, Canada, and South Korea serve as cross-regional bridge nodes, boosting network robustness and diversity.

In conclusion, AI+CCUS interdisciplinary research has established a "regional-dominance—multipolar-collaboration—functional-differentiation" global research landscape. Emerging research powers like China have established research hubs through large-scale project deployment, while technological leaders such as the U.S. maintain dominance via diffusion of methodological paradigms and model platforms. Strengthening multinational collaboration networks not only bridges the knowledge divide but also paves the way for more transferable and scalable AI-empowerment of CCUS systems. The subsequent section will focus on institutional-level research networks to identify key research teams and collaborative architecture features.

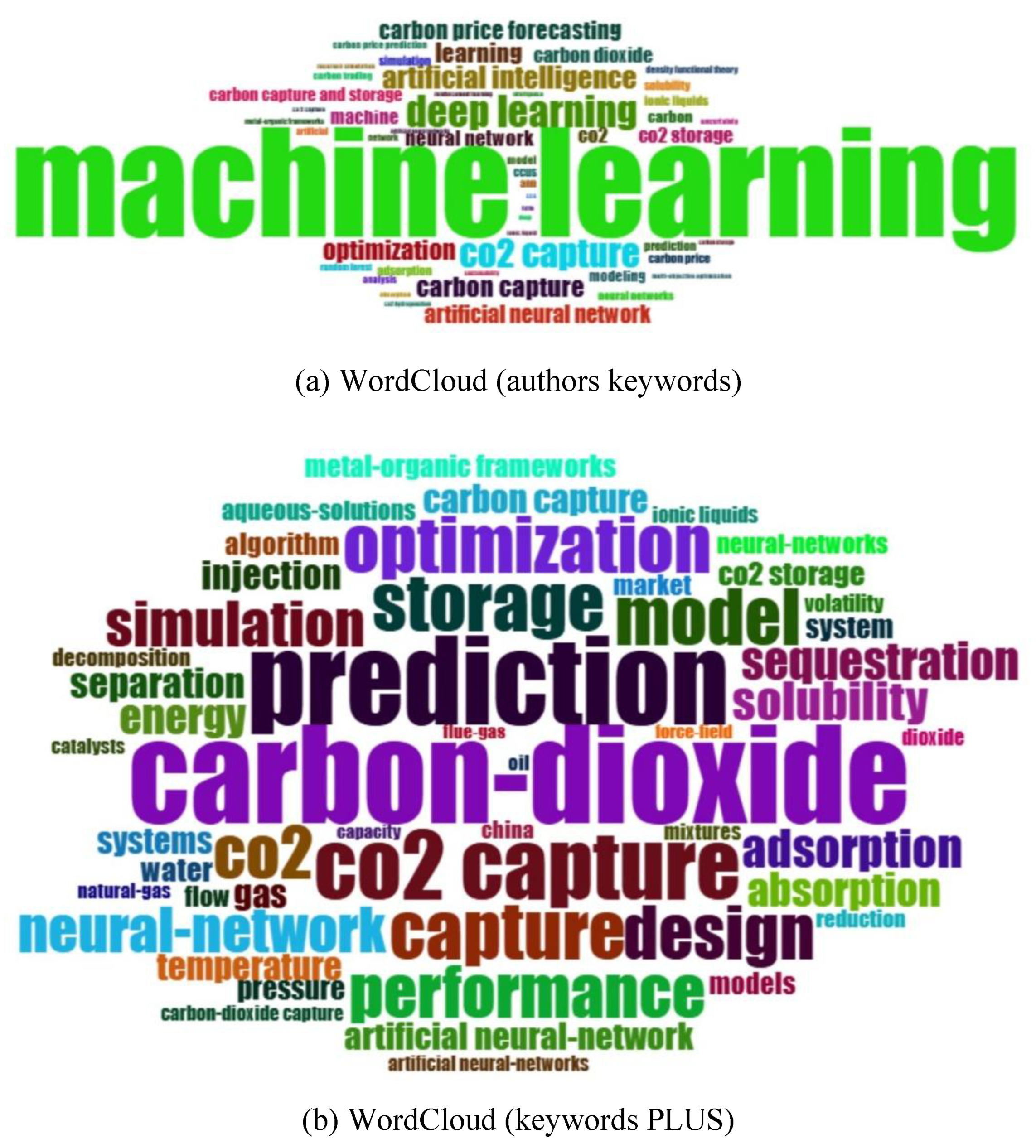

3.4. Keyword Clustering

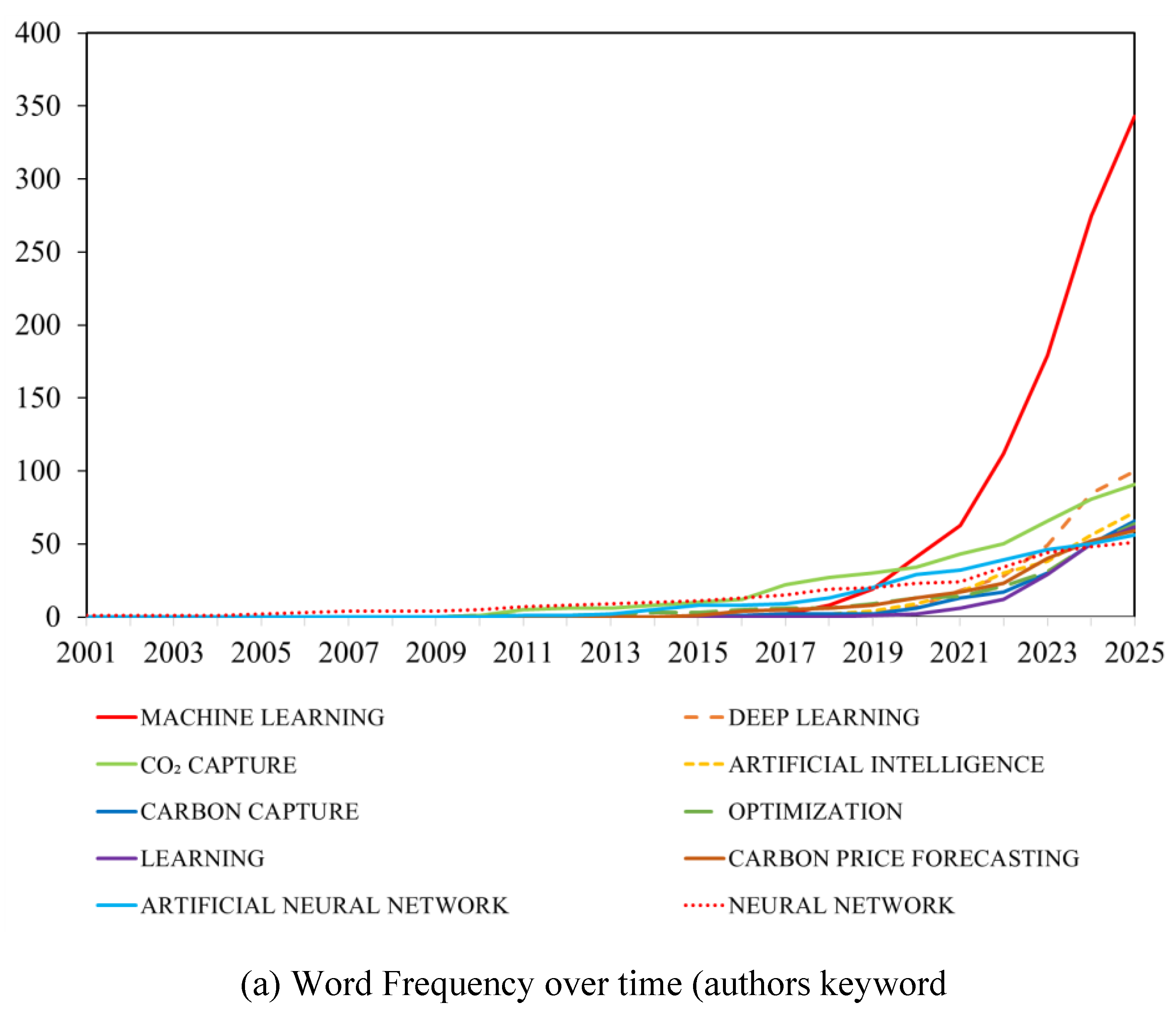

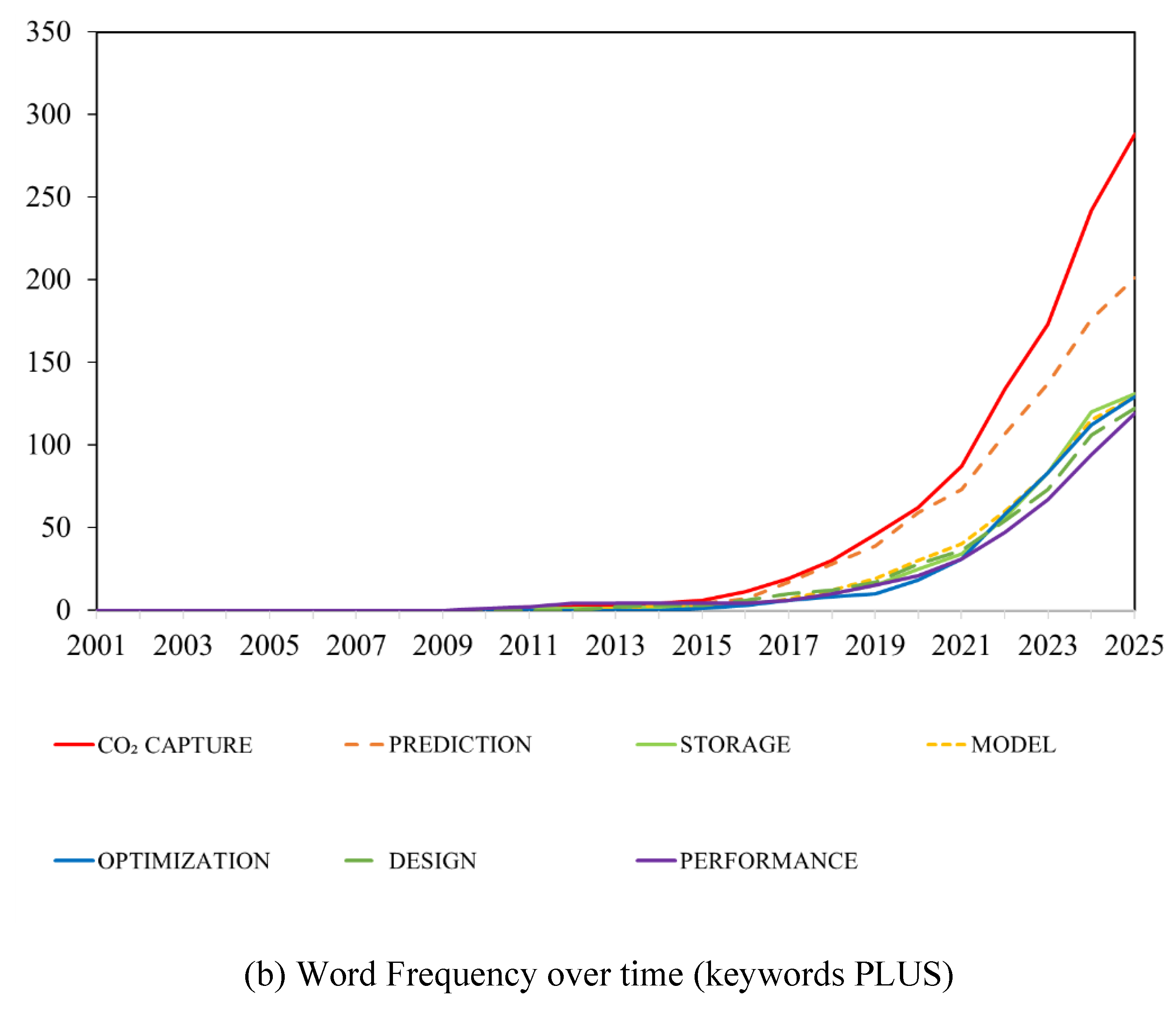

As highly condensed representations of document content, keywords serve as effective conduits for gaining insight into research fields' core themes, technological frontiers, and evolutionary trajectories. In this section, we characterize the "AI+CCUS" interdisciplinary knowledge architecture, technical preferences, and dynamic evolution by quantitatively and qualitatively analyzing Authors Keywords (reflecting authors' distillations of research cores and innovations, often signaling emerging concepts) and Keywords Plus (revealing deeper-level knowledge foundations and cross-field implicit linkages via citation networks). By integrating static analyses of high-frequency keywords (

Figure 4 (a),

Figure 4 (b)) with dynamic trend tracking (

Figure 5 (a),

Figure 5 (b)), this study has systematically mapped the "AI+CCUS" integration pathway from methodological innovation to engineering application maturation.

High-frequency analysis of Authors Keywords (

Figure 4 (a)) and Keywords Plus (

Figure 4 (b)) in AI+CCUS literature reveals core research foci and technological convergence zones. Overall, "prediction" (Authors: 30; Keywords Plus: 201), "optimization" (Authors: 64; Keywords Plus: 129), and "model" (Authors: 28; Keywords Plus: 129) rank among the top in both categories, indicating data-driven prediction and system optimization are core research foci. Basic CCUS concepts like "CO2 capture" (Authors: 91; Keywords Plus: 156) and "carbon dioxide"/"carbon-dioxide" (Authors: 48; Keywords Plus: 224) appear prominently, confirming carbon capture and CO2 management remain research cornerstones. Authors Keywords (

Figure 4 (a)) highlight AI methodological emphasis and innovation: "Machine learning" (343) and "deep learning" (100) dominate the list, outpacing all CCUS technical terms—evidence that AI itself drives research agendas. At the methodology level, "artificial neural network" (56) and "neural network" (51) remain prevalent, alongside diverse models like "random forest" (22), "LSTM" (17), and "reinforcement learning" (15)—reflecting active adoption of advanced AI for nonlinear modeling, time-series prediction, and intelligent control in CCUS. On the application front, "carbon price forecasting" (59) and "carbon price prediction" (24) underscore AI’s value in CCUS economic modeling and carbon market analysis. Keywords like "ionic liquids" (31) and "metal-organic frameworks" (18) further demonstrate AI applications in designing and screening novel carbon capture materials.

In contrast, Keywords Plus (

Figure 4 (b)) emphasize CCUS basic concepts, engineering processes, and physical–chemical mechanisms, reflecting the field’s knowledge base and established technical framework. Prominent terms like "carbon-dioxide" (224), "capture" (132), "storage" (131), "solubility" (90), "adsorption" (88), "absorption" (77), "separation" (70), and "injection" (68) systematically cover CCUS full-chain processes—capture, transport, utilization, storage—and their underlying physical–chemical mechanisms. Terms such as "design" (122), "performance" (119), "simulation" (105), and "systems" (60) highlight enduring focuses on systematic research, engineering design, and performance evaluation in CCUS. Despite being algorithm-generated, Keywords Plus frequently feature AI-related terms: "neural network" (104), "prediction" (201), "optimization" (129), and "model" (129)—confirming AI tools have become essential for addressing core CCUS engineering challenges.

In essence, the divergence between Authors Keywords and Keywords Plus exemplifies the deep interdisciplinary nature of AI+CCUS: the former emphasizes cutting-edge AI methodology innovations and emerging applications (e.g., carbon price forecasting), representing dynamic research frontiers; the latter anchors CCUS engineering fundamentals and basic scientific problems, forming the knowledge base. Semantically, method terms like "machine learning" and "deep learning" reside in the input layer; task terms such as "optimization" and "prediction" occupy the intermediate modeling layer; while "performance" and "carbon price forecasting" reflect research outputs and application focal points—together constructing the knowledge semantic framework of AI+CCUS.

Annual trend analysis of high-frequency keywords (

Figure 5 (a),

Figure 5 (b)) illuminates the evolutionary trajectory of research hotspots and technological integration dynamics in AI+CCUS. Authors Keywords trends (

Figure 5 (a)) show "machine learning" and "deep learning" have exhibited exponential growth since 2016—with "machine learning" publications surging from 1 in 2016 to 343 in 2025, and "deep learning" jumping from 2 in 2019 to 100 in 2025. This outpaces the steady growth of traditional AI methods (e.g., artificial neural networks and neural networks), confirming machine and deep learning as the most dynamic AI paradigms in AI+CCUS. This trend reflects researchers leveraging big data and high-performance computing through deep learning models to process CCUS’ complex, multi-modal datasets—enabling sophisticated prediction and optimization. Concurrently, "carbon price forecasting" has grown steadily (4 to 59 mentions 2016–2025), underscoring AI’s rising role in CCUS economic modeling and policy impact assessment. This signals a paradigm shift from pure technical focus to broader socioeconomic dimensions.

Contrasting Keywords Plus trends (

Figure 5 (b)), core CCUS engineering terms—"CO2 CAPTURE", "STORAGE", "OPTIMIZATION", "DESIGN", "PREDICTION", "PERFORMANCE"—exhibit sustained growth: "CO2 CAPTURE" rose from 2 in 2011 to 288 in 2025; "PREDICTION" from 1 in 2013 to 201 in 2025. This steady growth contrasts sharply with AI’s explosive surge yet reinforces it—evidence that AI advances complement rather than supplant CCUS’ traditional research agenda. As enabling tools, AI technologies have expanded CCUS research depth and breadth in capture efficiency, storage safety, system optimization, and performance modeling. Notably, "prediction" and "optimization" persist as high-frequency terms in both keyword categories, underscoring AI’s universal significance and critical role in enhancing CCUS operational efficiency and decision support. Collectively, keyword dynamics reveal a "method-driven problem-solving" trajectory: Authors Keywords reflect AI methodological innovations (especially deep learning) as direct drivers for CCUS advancement, while Keywords Plus highlight the core engineering challenges these innovations address—demonstrating how advanced AI tools enable deeper understanding of CCUS complex processes.

In conclusion, AI+CCUS research demonstrates a dual character of "AI method-driven" innovation and "CCUS problem-oriented" focus. Authors Keywords indicate that machine learning and deep learning have emerged as core AI paradigms, driving the rise of new applications like carbon price forecasting. Keywords Plus, conversely, focus on CCUS core engineering challenges—carbon capture, storage, optimization, prediction—highlighting the enduring importance of fundamental research. Collectively, keyword dynamics map the evolutionary trajectory: from early adoption of traditional AI methods to widespread deep learning integration, with increasing convergence across all CCUS process stages.

3.5. Keyword Evolution

For in-depth analysis of research frontier dynamics, this section quantitatively examines keyword life cycles. Tercile time points (Q1, Median, Q3) precisely map the developmental trajectory of specific terms—from emerging to mainstreaming before maturing.

Trend theme analysis (

Table 5) reveals remarkable paradigm shifts and dominance of AI in AI+CCUS research. "Machine learning", "deep learning", and "artificial intelligence" cluster around Q1=2022 and Median=2023–2024—collectively indicating these general AI methods have rapidly transitioned from exploratory use to dominant research paradigms.

Figure 6 (a) validates this exponential growth: 'machine learning' publications surged from 1 (2016) to 343 (2025). These algorithms now underpin core tasks—capture efficiency prediction, CO₂ reservoir modeling, carbon price analysis—driving AI+CCUS breakthroughs. In contrast, 'artificial neural network' and 'neural network' exhibit earlier lifecycle milestones (Median=2020 and 2022), representing foundational AI applications. Their relevance has since been iterated or integrated into more complex deep learning frameworks, reflecting rapid AI algorithm evolution in CCUS.

With AI enablement, CCUS core tasks exhibit steady growth and structural evolution. "CO₂ capture" (Q1: 2018, Median: 2022) and "CO₂ storage" (Q1: 2019, Median: 2021)—key terms in CCUS core processes—remain consistently active, indicating a shift in research focus from capture to full-chain operations, particularly the storage stage. Task-oriented terms like "prediction", "modeling", and "optimization"—central to AI-driven process efficiency and system robustness in CCUS—pervade the research timeline, underscoring AI’s strategic long-term value. Notably, the rise of macroeconomic terms such as "carbon price forecasting" (Q1: 2021, Median: 2023) signals AI applications have expanded to carbon market mechanism analysis, marking a paradigm shift from single-process modeling to broader system-level decision-making and policy simulation.

In the CCUS domain, AI-empowered micro-methodologies and emerging interdisciplinary themes are in continuous emergence. Emerging terms such as "time series" and "molecular" exhibit that their Q1, Median, and Q3 years all cluster in the 2023–2025 period, clearly indicating that they represent the most recent and growth-potential emerging directions in this field. These methods are particularly well-suited for tasks like high-frequency carbon price data analysis and molecular-scale screening and design of novel carbon materials, foreshadowing the disruptive application potential of AI in the deep crossfields of CCUS (such as computational chemistry and materials genomics). Meanwhile, the activity of early AI models such as "decision tree" and "LSSVM" (with Q1 generally concentrated around 2017 and Q3 concluding in 2021–2022) has shown a relative decline, reflecting that the algorithmic paradigms within the field are undergoing rapid update and iteration to better adapt to the increasingly complex data characteristics and model requirements of CCUS scenarios. This dynamic shift highlights the field's constant pursuit of technological advancement to tackle the evolving challenges in carbon capture, utilization, and storage.

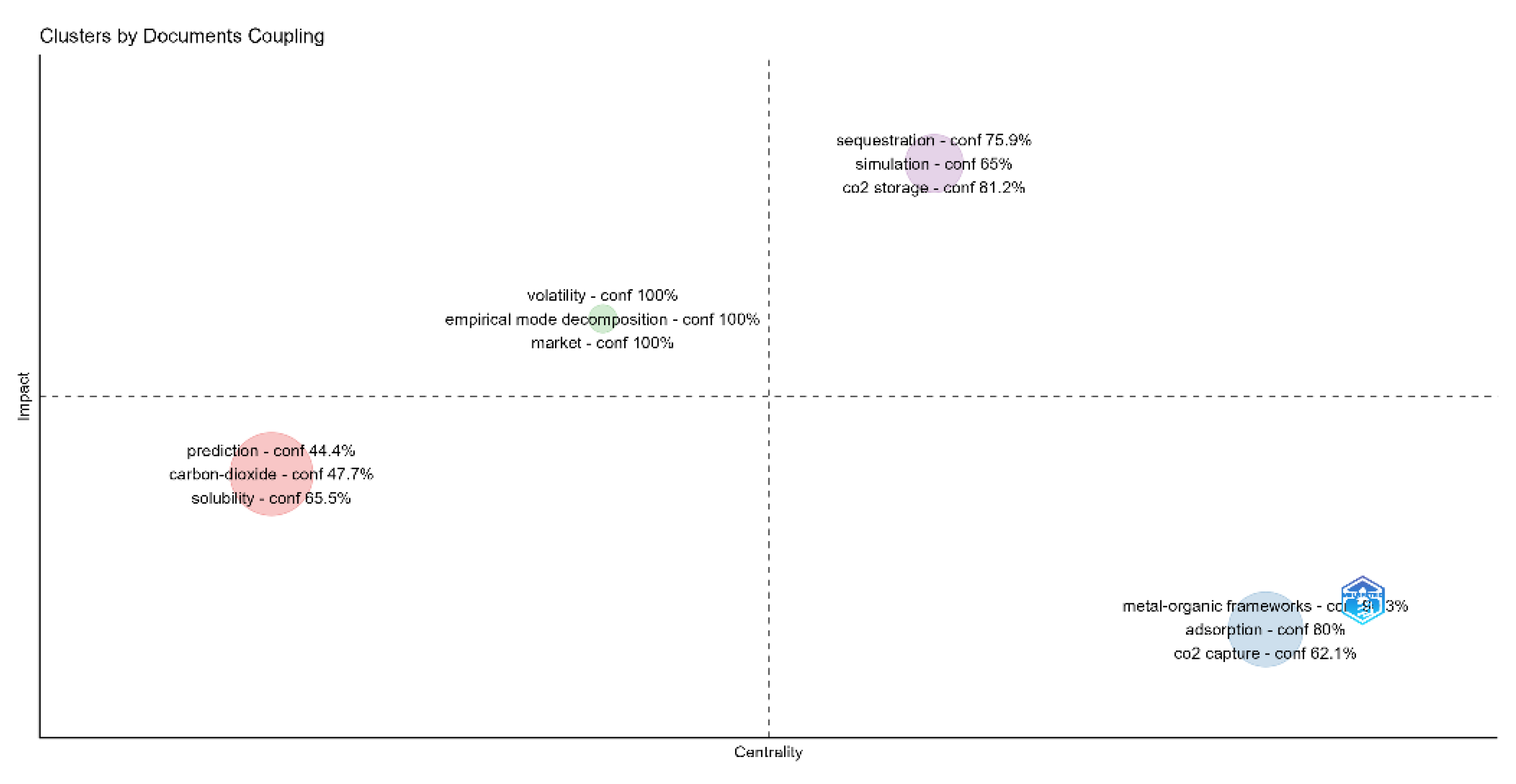

Visual analysis of the keyword co-occurrence network (

Figure 6) identifies four representative thematic clusters (see

Table 5 for manual induction and interpretation). These clusters represent key knowledge modules in AI+CCUS and illuminate AI’s functional roles and enabling pathways across CCUS technical domains: Cluster 1 centers on "prediction" and CO₂ solubility modeling, optimizing AI-based prediction accuracy for complex thermodynamics and phase equilibrium systems. With high influence (3.592), this cluster provides foundational support for system modeling and process optimization—AI enhances complex property prediction and uncertainty quantification here. Cluster 2 focuses on novel adsorbent materials (e.g., MOFs) and adsorption mechanisms, where AI enables material performance prediction, high-throughput screening, and structural analysis. Its high centrality (0.523) positions it as a knowledge network hub connecting Materials Science and Process Engineering, underscoring AI’s role in accelerating material R&D and capture process optimization. Cluster 3 addresses market fluctuations and time series analysis, reflecting emerging AI applications in carbon trading and environmental policy. Despite low frequency (25), its high influence index (4.630) signals strategic value for CCUS deployment and sustainability—AI supports market trend prediction and risk assessment here. Cluster 4 highlights AI’s role in subsurface reservoir modeling, storage safety assessment, and long-term monitoring. With the highest influence (5.510), this cluster is critical for CCUS industrialization, emphasizing AI’s necessity in reducing storage uncertainties. The clusters do not operate in isolation but form a close coupling chain under the deep enablement of AI technology, jointly constructing the knowledge ecosystem of "AI+CCUS": in terms of basic prediction and application support, the accurate basic prediction model provided by Cluster 1 provides key data and model support for the material design and optimization of Cluster 2 (material screening and capture technology) and the complex geological behavior prediction of Cluster 4 (storage simulation and system evaluation). In terms of economic orientation and strategy feedback, the macroeconomic analysis results of Cluster 3 (carbon market and economic prediction) can feed back the cost-benefit assessment and policy adaptability path formulation of technical links such as Clusters 2 and 4 to ensure the economic feasibility and social sustainability of CCUS technical paths. As the core technical hub running through all clusters, AI plays an indispensable bonding and amplifying role in driving data modeling, realizing multi-source heterogeneous information integration, and optimizing decision-making processes, so that the synergistic effect between different technical modules can be maximized.

Based on the comprehensive analysis of keyword life cycles and co-occurrence structures, "AI+CCUS" research is in a critical leap stage from initial exploratory applications to comprehensive paradigm transformation. This transformation is prominently manifested as: the deep evolution of AI methodologies, where the research focus has fully shifted from traditional machine learning algorithms to more advanced AI paradigms dominated by deep learning; the broad expansion of research scope, where application scenarios have extended from local modeling of single engineering links to system-level macro-policy and economic benefit analysis; the systematic integration of optimization objectives, where research goals are evolving from local single-task optimization to full-process, cross-scale, and multi-objective system collaboration and integration.

4. Discussion

4.1. Enabling Logic of AI for Different CCUS Stages

AI’s prowess in data processing, pattern recognition, and complex system modeling has enabled its deep penetration into all CCUS research stages and application scenarios—emerging as a core driver for knowledge innovation and technological advancement. Keyword co-occurrence analysis (

Figure 6) and high-frequency keyword statistics (

Figure 4) uncover tight integration of AI with CCUS core tasks: AI methodology terms ("machine learning", "deep learning") exhibit strong co-occurrence with CCUS task terms ("CO₂ capture", "storage", "optimization", "prediction"), demonstrating AI’s extensive embedding in CCUS technical stages. This is manifested in AI’s high adaptability and architectural capabilities in task logic, model design, and system coordination (see

Table 6).

In the front end of the CCUS technology chain for CO₂ capture, AI applications have significantly accelerated the R&D of new high-efficiency capture materials and improved the efficiency of capture processes (Charalambous et al., 2024, Ismail et al., 2025). For instance, in Keyword Cluster 2, themes like "metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)" and "adsorption" show strong co-occurrence, highlighting AI’s central role in screening porous adsorbents and predicting their performance (

Figure 6). Researchers leverage AI algorithms (e.g., GNN, AutoML) to perform high-throughput virtual screening and adsorption performance prediction for candidate materials (e.g., MOFs, ionic liquids), substantially shortening R&D cycles and reducing experimental costs (Feng et al., 2024, Raza et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2022) . AI’s enabling logic resides in its capacity to learn from vast chemical structure spaces and construct precise "structure-performance" prediction models, overcoming the efficiency and coverage limitations of traditional trial-and-error experiments and computational simulations. This provides a core driving force for source innovation in the CO₂ capture stage.

In the CO₂ utilization stage, AI technologies are facilitating efficient catalyst design and CO₂ conversion pathway optimization, aiming to transform captured CO₂ into valuable fuels or chemicals (Aklilu and Bounahmidi, 2024, Dmitrieva et al., 2024). Although no independent CO₂ utilization cluster emerged in this keyword analysis, search terms like "CO₂ hydrogenation" and "CO₂ electroreduction" highlight the significance of utilization pathways. DNN and Transformer models are applied to predict catalyst activity, selectivity, and reaction pathway energy barriers—addressing the data volume and computational efficiency limitations of traditional density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Araujo et al., 2022, Singh and Sunoj, 2023). AI’s enabling logic manifests in its ability to learn complex catalytic mechanisms and multi-dimensional parameter space, guiding rational catalyst design and intelligent reaction condition optimization. This enhances the economic viability and feasibility of CO₂ resource utilization.

In CO₂ geological sequestration, AI is critical for enhancing reservoir modeling accuracy, predicting long-term CO₂ plume migration, monitoring leakage risks, and evaluating sequestration safety (Du et al., 2025, Sori et al., 2024). Keyword Cluster 4 (core terms: "sequestration", "simulation", "CO₂ storage") and Cluster 1 (core terms: "prediction", "carbon dioxide", "solubility") together reflect AI’s deep penetration in this domain (

Figure 6). Emerging AI algorithms like PINNs integrate physical governing equations with monitoring data to enable rapid, accurate simulation of reservoir heterogeneity, CO₂ plume migration, CO₂ injection-production dynamics, and potential leakage pathways (Mao and Ghahfarokhi, 2024, Wang et al., 2024a). AI’s enabling logic lies in its capacity to efficiently process and integrate multi-source heterogeneous data (geological, geophysical, logging), thereby overcoming traditional numerical simulation challenges in computational efficiency and uncertainty quantification. This provides key technical support for ensuring long-term CO₂ sequestration safety and effectiveness.

Notably, AI applications have transcended CCUS’ traditional engineering boundaries, expanding into emerging crossfields like carbon market analysis and environmental-economic decision-making (Oladokun et al., 2024, Xu et al., 2024). Keyword Cluster 3 highlights AI’s role in carbon trading and market prediction—featuring thematic terms ("volatility", "market") and analytical methods (e.g., "empirical mode decomposition") (

Figure 6). Additionally, "carbon price forecasting" emerged as a high-frequency author keyword, indicating AI is being used to analyze carbon market price volatility, predict trends, and support investment strategy and policy formulation (Liu et al., 2024, Yue et al., 2023). AI’s enabling logic here is leveraging robust time-series analysis and complex system modeling to provide data-driven decision support for CCUS economic feasibility assessments and macro-policy design.

In summary, AI applications in CCUS exhibit multi-scenario penetration and deep integration. AI not only delivers innovative solutions for capture, utilization, sequestration, and carbon market domains but, more importantly, reshapes and integrates CCUS knowledge structures as a core methodology. Analysis of keyword co-occurrence networks (

Figure 6) reveals AI serving as a knowledge integrator, systematically connecting materials science, chemical engineering, geosciences, and economics within the CCUS framework—facilitating interdisciplinary knowledge flow and integration. This transition from "instrumental modeling" to "systematic support" signifies AI’s emergence as an indispensable component of CCUS knowledge innovation, making critical contributions to achieving carbon neutrality.

4.2. Analysis of Technological Evolution Path and Trends

Since the early 21st century, AI’s integration into CCUS has exhibited stage-wise evolution, reflecting multi-dimensional synergies across the technology lifecycle. Central to this progression is the transformation of AI’s role in CCUS—from early "instrumental modeling" addressing isolated challenges to "systematic integration" driving holistic value chain optimization. This shift is not a linear accumulation of technologies but a complex interplay co-driven by policy imperatives and AI breakthroughs. Based on keyword evolution and lifecycle analysis (

Figure 4,

Figure 5), this study classifies the technological evolution of AI+CCUS into four stages: emergence stage, initial growth stage, accelerating stage, and Expansion Stage (

Table 7). Each stage demonstrates distinct differences in dominant algorithms, model sophistication, and applicable tasks, while underlying them is the collaborative evolution trajectory between varying policy contexts and technological capabilities.

During the emergence stage, AI remained in the early phase of functional modeling exploration, primarily applied to single-point prediction with structured small-sample data (Liu et al., 2001, Xiang, 2009) . As

Table 7 shows, typical algorithms included SVM, decision trees (DT), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), and early ANN. CCUS itself was in technical exploration and policy infancy, with research focused on adsorbent development and geological sequestration feasibility. Although AI methods like SVM and early ANNs were occasionally used, applications remained fragmented, and no systematic research direction emerged

(Drage et al., 2009, Figueroa et al., 2008). Keyword analysis shows AI-related terms (e.g., "neural network") appeared sporadically, with no established research focus (

Figure 4). Models were shallow, highly regular, and interpretable—suitable for preliminary performance fitting and rule extraction. AI primarily added value by reducing screening costs and accelerating modeling, but showed limited cross-task transfer and data integration—exhibiting "weak integration, strong focus on local tasks". Policy-wise, global climate governance was in its inception stage. While foundational agreements like the Kyoto Protocol existed, CCUS lacked clear positioning and systemic deployment incentives (Cook, 2008), providing little external traction for AI applications. Technically, early-stage AI faced algorithmic limitations, computing resource constraints, and data acquisition bottlenecks—hindering progress. These policy-technical constraints together defined AI’s "marginal exploration" role in early CCUS development.

During the initial growth stage, the application paradigm shifted from "single-point optimization" to "multi-scenario exploration", with this transition marking ML’s initial expansion in CCUS. As

Table 7 shows, this period saw gradual adoption of complex ANNs, RF, and ensemble methods (e.g., Boosting). Compared to earlier shallow models, these approaches enhanced nonlinear relationship modeling, multi-variable processing, and high-dimensional data adaptation—delivering higher prediction accuracy and generalization (Ghafouri-Kesbi et al., 2016, Mishina et al., 2015). Studies also proposed fusing RF and ANN to create "neural forest" models, effectively expanding AI’s representational power in complex system modeling (Welbl, 2014). CCUS research expanded from material adsorption prediction to catalyst performance evaluation, CO₂ injection prediction, and sequestration leakage risk assessment. For instance, ML and numerical simulation were explored for sequestration risk assessment, monitoring design, and process optimization—showing early cross-task modeling despite shallow model structures, which primarily served rule extraction and sensitivity analysis (Asamoto et al., 2013, Augustin, 2014, Peter et al., 2011) . Policy-wise, climate consensus (e.g., Copenhagen Accord) deepened global understanding of CCUS. Although non-binding, the Accord spurred voluntary emission reduction commitments, "from the bottom up" driving diversified carbon policies (Buhi, 2011, Jotzo, 2011). Rising complexity in CCUS deployment—driven by cost, efficiency, and safety imperatives—generated policy momentum for AI in optimization, technical evaluation, and system integration (Beecy and Simbeck, 2011, Tokushige and Akimoto, 2011). Technically, matured ML methods, combined with growing computational power and experimental data (e.g., CCP3 pilot projects), strengthened AI’s data foundation for CCUS modeling

(Miracca et al., 2014). Concurrently, policy efforts to regulate large-scale CCUS projects enabled embedded AI applications

(Huang et al., 2014).

The accelerating stage marks a critical transition for AI+CCUS from "empirical modeling" to "intelligent perception and structured modeling", with deep learning (DL) advancements driving this paradigm shift. As

Table 7 shows, researchers adopted deep models (CNN, LSTM) for core image recognition, nonlinear feature extraction, and injection-production time-series modeling—accumulating technical frameworks for industrial process modeling and dynamic prediction, which informed intelligent modeling of CCUS physical processes (Emam et al., 2020, Xing et al., 2019, Yuan et al., 2020). In carbon capture, deep models enabled nonlinear mapping between adsorbent microstructures and macroscopic properties. For example, DNN predicted CO₂ adsorption in porous carbons by extracting pore size distribution and specific surface area to build efficient models

(Zhang et al., 2018). GNN optimized MOF structure-performance mapping, enhancing virtual screening efficiency

(Wang et al., 2020), while ensemble methods (e.g., RF) identified key adsorption influencers (micropore volume, surface polarity) with strong generalization

(Zhu et al., 2020). In geological sequestration, AI processed multi-source geological data (lithology, porosity, faults) to enable high-resolution reservoir modeling—predicting CO₂ plume migration and pressure dynamics via deep neural networks and gradient boosting models

(Amini and Mohaghegh, 2019). Clustering and dimensionality reduction integrated multi-source data to improve leakage risk and uncertainty identification

(Chen et al., 2018), evolving research toward spatio-temporal and cross-task intelligent systems. Policy-wise, the Paris Agreement and national carbon neutrality strategies elevated CCUS policy status, driving large-scale deployment and full-life-cycle governance. Article 6 supports CCUS through international cooperation (Carey and Yang, 2020), while Japan and the U.S. strengthened policy-technology frameworks (Edwards and Celia, 2018, Yanagi and Nakamura, 2020). Technically, GPU computing, mature DL frameworks, and enhanced data acquisition enabled complex CCUS modeling. This stage saw AI evolve from local optimization to systematic modeling with structural understanding—laying the groundwork for system-level collaboration.

Since 2021, AI research in CCUS has accelerated rapidly, advancing toward systematic integration and intelligent ecosystem development—marking AI+CCUS’ entry into a new phase of cognitive integration and cross-domain synergy. The Expansion Stage is characterized by marked increases in model diversity, application complexity, and methodological systematicity. As

Table 7 shows, next-generation AI approaches (Transformer architecture, LLM, PINN, generative adversarial networks (GAN), variational autoencoders (VAE)) have emerged and been applied to CCUS subsystems. PINN enhances model generalization in data-sparse regions via embedded physical governing equations, showing promise in scale-transition geological modeling (Shu et al., 2024). GAN-Transformer hybrids improve generative modeling for image and time-series synthesis, enabling material design and reaction pathway exploration (Xu et al., 2021, Zhu and Yen, 2024). VAE-GAN architectures facilitate chemical space exploration, supporting closed-loop catalyst design workflows (Cai, 2024). LLM and AI agents are being used for carbon market policy modeling, price prediction, and trading strategy generation. In energy system scheduling, AI agents integrate "perceive-reason-act" loops to optimize control strategies in real time, demonstrating multi-agent coordination (Sanabria and Vecino, 2024, Zhang, 2024, Zhao et al., 2024). Digital twin platforms provide high-fidelity test environments integrating data, control, and physical domains (Gulyamov et al., 2024) , enabling AI models to perform multi-variable testing, cross-scale prediction, and real-time control in virtual spaces—facilitating virtual-real strategy optimization (Bassey, 2022, Koeva and Kutkarska, 2024). Policy-wise, carbon neutrality drives CCUS toward "systems engineering" with whole-process, cross-sectoral collaboration, where AI supports advanced tasks like economic assessment and life-cycle management (Cong et al., 2024, Luqman et al., 2024). Keyword co-occurrence networks (

Figure 6) show frequent macroeconomic terms (e.g., "carbon price forecasting"), indicating AI’s expansion into non-engineering domains. This stage features three key leaps: technological paradigm shifting from task-oriented modeling to system-embedded approaches, functional role upgrading from modeling tools to knowledge construction and strategy generation platforms, and system positioning evolving from point-scale deployment to full-life-cycle intelligent ecosystem development. These advancements signify AI’s evolution from a "modeling tool" to a cognitive integration center in CCUS, providing foundational support for intelligent CCUS systems.

4.3. Analysis of Application Challenges and Prospects

While AI has achieved notable advancements in core CCUS stages—showcasing potential in material screening, reservoir modeling, and monitoring optimization—scaling up from lab validation to engineering deployment remains challenged by technical bottlenecks and systemic barriers. AI’s full integration into CCUS is hindered by limitations in data infrastructure, model interpretability, geoscientific semantic fusion, and deployment architecture, urgently needing systematic reengineering (

Table 8).

First, heterogeneity and scarcity of multi-source data pose key technical bottlenecks for AI-enabled CCUS modeling. CCUS systems require fusing data across scales—3D seismic inversion, downhole logging, core properties, and numerical simulations—heterogeneous in spatial resolution, physical semantics, and acquisition methods. For instance, seismic data (meter-to-hundred-meter resolution) characterize macrostratigraphy, while logging core data (micro-to-centimeter scales) provide pore structure details, creating resolution mismatches. Such mismatches challenge AI models in representing high-dimensional low-frequency and low-dimensional high-frequency information, degrading prediction accuracy (Bassoult, 2023). Although AI can reconstruct missing logging acoustic data to improve well-seismic matching, prediction accuracy deteriorates with insufficient data density or hierarchical inconsistencies (Yusuf et al., 2024). Joint modeling of seismic attributes and logging data shows promise for fracture or porosity-permeability modeling but requires high-resolution, quality-controlled labeled data. Without open-access sharing platforms, AI models lack cross-regional generalization (Cho, 2021). Thus, constructing multi-source datasets, standardizing acquisition and quality control, and promoting open-source platforms are critical pathways to address data bottlenecks.

Second, the "black-box nature" of AI models and lack of physical consistency with geological laws restrict their reliable application in high-risk engineering scenarios. While deep learning models (e.g., CNN, LSTM) achieve high accuracy in geological modeling and pressure prediction, their opaque decision processes challenge trust from engineers and regulators—particularly in high-stakes CO₂ injection operation (Chowdhury et al., 2025). Mainstream interpretability methods (SHAP, LIME) excel in discrete tasks (e.g., medical imaging) but struggle with high-dimensional continuous data (seismic profiles, logging curves). For instance, inconsistent definitions of feature "importance" across methods lead to interpretation inconsistencies in complex oil-gas datasets, undermining method reliability (Chowdhury et al., 2025). Most AI models omit explicit embedding of geophysical constraints (Darcy's law, mass conservation), leading to unphysical predictions in data-scarce regions (Delpisheh et al., 2024, Jenkins, 2024). While PINN incorporate governing equations as loss terms (Zhang et al., 2025), they face convergence challenges and high computational complexity in heterogeneous multi-scale media and coupled multi-physics systems (Wang et al., 2024b).

Third, the "semantic gap" between AI models and geoscientific knowledge limits deep interdisciplinary integration and high-quality knowledge transfer in CCUS. Geological knowledge primarily exists as unstructured text and images without unified semantic representation, hindering direct AI model input. Traditional data-driven AI models fail to integrate geological experts’ causal reasoning frameworks and unstructured knowledge (annotated profiles, lithology briefings) (Keefer, 2023, Qiu et al., 2023, Rajput and Pathak, 2025). To address this, studies have developed "geological knowledge graphs"—encoding reservoir structures, lithology, and faults as "concept-relationship-attribute" triples to enable semantic query and AI modeling (Guo et al., 2021). These graphs enhance semantic consistency, support reasoning, and assist AI models in geoscientifically informed input selection and interpretation (Ma, 2022). Researchers have also proposed "multi-layer semantic modeling" frameworks (concept-entity-relationship layers) to transform expert knowledge into machine-readable formats, validated in mineral prediction and reservoir characterization (Tian et al., 2024). However, most geological knowledge graphs remain in prototype stages, facing challenges like inconsistent ontology standards, poor cross-scenario transfer, and lack of engineering deployment (Zhou et al., 2021). These limit their ability to support dynamic CCUS modeling. Thus, developing standardized, AI-embeddable geoscientific knowledge graphs with reversible semantic mapping among geoscientific concepts, numerical features, and predictive reasoning is critical for deepening AI-CCUS integration.

Engineering deployment of AI in CCUS also faces multi-dimensional challenges: strong scenario dependency, high integration complexity, fragmented standards, and security gaps. First, diverse geological settings, monitoring systems, and operational strategies across CCUS projects limit AI model generalization, requiring repeated retraining and fine-tuning for site-specific deployment—escalating costs and delays (Dzhusupova et al., 2022). Second, AI systems require deep integration with industrial automation (e.g., SCADA), but fragmented protocol standards (OPC UA, Modbus) necessitate manual interface adaptation, hindering model portability and reuse (Stanko et al., 2024). Third, inconsistent containerization and operation norms in industrial AI frameworks, coupled with rapid LLM evolution, complicate model versioning, updating, and edge deployment (Parejo and Sánchez, 2023). Critically, absent safety verification and liability auditing for AI decision systems pose risks: model errors in high-stakes CO₂ sequestration could cause major incidents, but unclear legal liability frameworks hinder adoption (Wang et al., 2024). Thus, developing CCUS-specific AI deployment frameworks—standardizing protocols, containerization, security auditing, and cross-scenario generalization—is critical for transitioning AI from research prototypes to engineering applications.

To address these challenges, the integrated development of AI+CCUS requires collaborative advancement in four dimensions: data infrastructure, reliable model systems, semantic fusion mechanisms, and deployment architecture standards, to build an intelligent ecosystem with engineering feasibility and long-term evolution capabilities (

Table 9). At the data level, efforts should be accelerated to construct an open data platform covering diverse geological conditions, demonstration projects, and multi-scale observation methods. This platform should standardize the structure and semantics of multi-source heterogeneous data (3D seismic volumes, remote sensing images, well logging, core experiments, multiphase simulations) and introduce joint annotation, quality assessment, and version control to enhance data reusability and training representativeness (Li et al., 2021, Zelba et al., 2024). For model development, it is essential to enhance the interpretability and physical consistency of deep learning models, promote integration of explainable AI (XAI) with physics-constrained networks (e.g., PINN, PGNN), and establish reliable model frameworks with causal tracing, cross-scenario generalization, and multi-task adaptation

(Liu et al., 2021). In semantic fusion, a CCUS-specific knowledge graph system is recommended to define logical relationships between core concepts (reservoir types, physical parameters, fault structures). By integrating ontology embedding with graph neural networks, this system can establish mapping between geological semantics and AI model feature spaces, enabling deep collaboration between expert knowledge and machine learning

(Rodríguez et al., 2023). For engineering deployment and supervision, unified standards for model interfaces and operational safety should be set, while containerized modular architectures and "cloud-edge-end" collaboration should be promoted to enhance model portability and cross-platform compatibility

(Helmer et al., 2024). Additionally, a regulatory system covering algorithm auditing, traceability, data privacy, and result verification is needed to ensure AI robustness, safety, and compliance in critical scenarios, providing institutional support for high-risk applications

(Zelba et al., 2024).

In summary, AI’s enabling value in CCUS has evolved from tool-based applications to system-level integration. Future development should be guided by the four-in-one integration of data, knowledge, physics, and deployment—driving the creation of intelligent CCUS systems with cognitive reasoning, autonomous optimization, and real-time response capabilities. This paradigm shift will not only enhance CCUS engineering efficiency and economic viability but also deliver essential digital support for achieving carbon neutrality.

5. Conclusion

Using bibliometric analysis, this paper presents a systematic review and analysis of AI’s deep integration trajectory and technological evolution in CCUS during 2001–2025. The study reveals that AI has evolved from an "auxiliary tool" to a central hub for "systematic support" and "intelligent collaboration" across the CCUS industry chain. Specifically, the integration of AI methodologies with CCUS engineering tasks exhibits the following key characteristics and evolutionary patterns.

Technologically, AI applications in CCUS have undergone a four-stage evolution. In the emergence stage (<2010), shallow ML models (SVM, DT, KNN, early ANNs) dominated, primarily used for regression prediction and small-sample fitting of capture material properties, simple geological parameters, or fluid characteristics. Here, AI served as a computational accelerator rather than a systematic research framework. During the initial growth stage (2011–2016), driven by global CCUS pilots and initial ML applications (RF, Boosting, deeper ANNs) in material screening and monitoring, AI expanded to complex multivariate tasks—CO₂ utilization optimization, leakage risk assessment—though still in a multi-scenario trial phase. The accelerating stage (2017–2020) saw deep learning (CNN, LSTM), GNN and PINN enable stronger feature extraction and physical consistency for CCUS modeling. Breakthroughs emerged in reservoir heterogeneity simulation, CO₂ plume prediction, and long-term storage assessment, with AI models integrating into engineering workflows to demonstrate cross-scale, multi-task optimization. In the Expansion Stage (2021–present), large pre-trained models (Transformer, LLM), multimodal DL, and digital twins have penetrated CCUS—from carbon capture material discovery to carbon market prediction and intelligent monitoring. AI now drives the "perceive-model-predict-decide" closed loop across CCUS lifecycles, marking a paradigm shift from instrumental modeling to systematic integration.

Keyword evolution analysis of Authors’ Keywords and Keywords Plus reveals the dynamic interplay between AI methodologies and CCUS research priorities. Early keywords centered on basic methods and single tasks ("neural network", "support vector machine", "optimization", "model"), while mid-late stage saw rapid emergence of "machine learning", "deep learning", "graph neural network", "carbon price forecasting"—signaling AI’s paradigm shift from "shallow models-traditional algorithms" to "deep learning-hybrid frameworks" in CCUS. CCUS-related enhanced keywords ("CO₂ capture", "storage", "solubility", "adsorption") remained persistently high-frequency, reflecting sustained focus on engineering and physicochemical processes. Notably, economy- and policy-related terms ("carbon price forecasting", "market volatility") have entered the research spotlight, indicating AI’s expansion from technical modeling to techno-economic-policy integrated analysis—a hallmark of multidisciplinary convergence.

Multi-source heterogeneous data and semantic fusion pose deep bottlenecks for AI in CCUS. As dissected in

Section 4.3, core challenges include: data scarcity and heterogeneity, model interpretability gaps, physics-inconsistent modeling, geoscience-AI semantic divides, and deployment and regulatory barriers. CCUS data—seismic profiles, logging curves, core analyses—vary drastically in scale and semantics. Without unified cross-scale fusion frameworks, AI models overfit in small-sample environments and fail to migrate. Black-box DL models lack interpretability, eroding trust in high-risk applications (CO₂ leakage warning). Physics-constrained networks (PINN, PGNN) address this partially but remain limited by training overheads and incomplete physical priors. Tacit geoscientific knowledge (lithology evolution, fault genesis) remains unstructured, creating semantic divides with AI. Heterogeneous engineering setups—fragmented SCADA systems, non-standardized deployment—hinder AI scaling from pilots to industry. Institutional gaps—including missing safety certification, interpretability auditing, and data privacy rules—compound adoption barriers.

Globally, this study examines CCUS research ecology and collaboration networks, analyzing institutional outputs and international cooperation patterns across China, the U.S., Europe, Canada, and emerging economies. It reveals an "engineering-led, AI-augmented" paradigm with geographical concentration. China’s research, dominated by universities, excels in applied case studies but has room for higher international collaboration. The U.S., led by top institutions (UT Austin, Stanford), leads in algorithm innovation and multi-scale physical modeling. Canada, the UK, and others focus on integrating multi-scale modeling with economic policies, establishing high-impact research niches. Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian nations build localized AI+CCUS ecosystems driven by regional engineering needs and policies. While institutional research agendas often overlap, inter-institutional collaborative pathways—especially between engineering-focused, computer science, and comprehensive research universities—remain underdeveloped. Future efforts should establish interdisciplinary research hubs and industry-academia platforms to foster deep collaboration between AI and geological engineering teams, overcome research paradigm lock-in, and build more open global innovation networks.

In summary, this study makes three significant innovative contributions:

1.Revealing AI’s evolutionary trajectory in CCUS

Using CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and Bibliometrix, this research has mapped AI’s progression in CCUS—from shallow algorithms to deep learning, and from local optimization to system-level support. It identifies technological milestones across CCUS sub-processes (capture, utilization, storage, monitoring), clarifying AI’s role, evolution patterns, and collaborative mechanisms to provide a comprehensive research roadmap.

2.Analyzing integration barriers and future pathways

The study systematically examines core challenges—data heterogeneity, model interpretability gaps, physical inconsistency, geoscience-AI semantic divides, and deployment and regulatory barriers. This analysis provides theoretical and practical guidance for four key directions: trustworthy AI models, knowledge graph-semantic embedding, standardized deployment frameworks, and multi-source open data. By doing so, it accelerates AI’s transition from "point solutions" to systematic reconstruction in CCUS.

3.Mapping the global AI+CCUS research ecosystem

Through bibliometric analysis of journal distributions, national/institutional outputs, and collaboration networks, this work depicts global R&D resource allocation and developmental disparities. It offers policymakers and industry stakeholders insights into international competition landscapes and collaboration opportunities. Comparative analyses of research focuses in China, the U.S., Europe, Canada, and emerging economies further facilitate cross-regional cooperation and complementary innovation.

Based on the above research findings, the "AI+CCUS" field urgently needs further in-depth exploration in the following aspects: First, it is necessary to accelerate the construction of multi-level, high-quality open-source datasets covering seismic, logging, core, remote sensing, and simulation results, and formulate unified collection, storage, and sharing specifications to break disciplinary and regional data silos, providing a solid data foundation for the cross-scale integration and generalization capabilities of AI models. Second, hybrid model architectures that integrate physical constraints and interpretability mechanisms should be further developed. Physical guidance network models represented by PINN should make breakthroughs in "multi-physics field coupling", "efficient solution", and "causal interpretability" to enhance the engineering credibility of models in industrial scenarios. Third, a joint learning framework of "geoscience ontology + knowledge graph + semantic embedding" needs to be constructed to structure geological tacit knowledge such as strata, faults, and porosity, and seamlessly connect with AI feature vectors to enhance the model's ability to understand complex geological problems and provide decision support. Fourth, at the engineering deployment and supervision level, it is necessary to formulate AI model safety certification and audit standards for CCUS scenarios, construct containerized deployment and online learning systems suitable for cloud-edge-end environments, and form supporting institutional guarantees in terms of law, ethics, and data privacy. Only by advancing simultaneously in the four dimensions of "data-model-semantics-deployment" can AI truly achieve efficient empowerment of the entire CCUS life cycle and help the strategic implementation of the carbon neutrality goal.

In summary, AI has revolutionized CCUS with intelligent innovations. Its evolutionary trajectory from tool-based applications to systematic integration has not only reshaped geological process modeling and carbon reduction engineering paradigms, but also provided key technical support for tackling global climate change and energy transition challenges. In the future, through interdisciplinary collaboration, open data sharing, construction of model trustworthiness, and optimization of engineering deployment paths, AI is expected to drive CCUS technology from demonstration scenarios to large-scale strategic deployment, serving as a key driver for global green and low-carbon development.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF0801201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1911202), and the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2020B1111370001).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the valuable feedback and insightful suggestions provided by the reviewers, which have significantly improved the quality of this manuscript. We also extend our gratitude to the editorial team for their careful handling of our submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

TS=(

(

"artificial intelligence" OR "artificial intelligent"

OR "machine learning"

OR "deep learning"

OR AI

OR "supervised learning"

OR "unsupervised learning"

OR "semi-supervised learning" OR "semisupervised learning"

OR "reinforcement learning"

OR "deep reinforcement learning"

OR "transfer learning"

OR "meta-learning"

OR "neural network"

OR "convolutional neural network" OR CNN

OR "recurrent neural network" OR RNN

OR "long short-term memory" OR "long short term memory" OR LSTM

OR "graph neural network" OR GNN

OR "generative adversarial networks" OR GAN

OR "autoencoder"

OR "decision tree"

OR "random forest"

OR "gradient boosting"

OR "XGBoost"

OR "support vector machine" OR SVM

OR "Bayesian network"

OR "ensemble learning"

OR "digital twin"

OR "attention mechanism"

OR "transformer model"

OR "transformer-based model"

OR "pretrained model"

OR "pre-trained model"

OR "pretrained language model"

OR "foundation model"

OR "foundation models"

OR "large language model" OR "large language models" OR LLM OR LLMs

OR "generative pretrained transformers"