Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

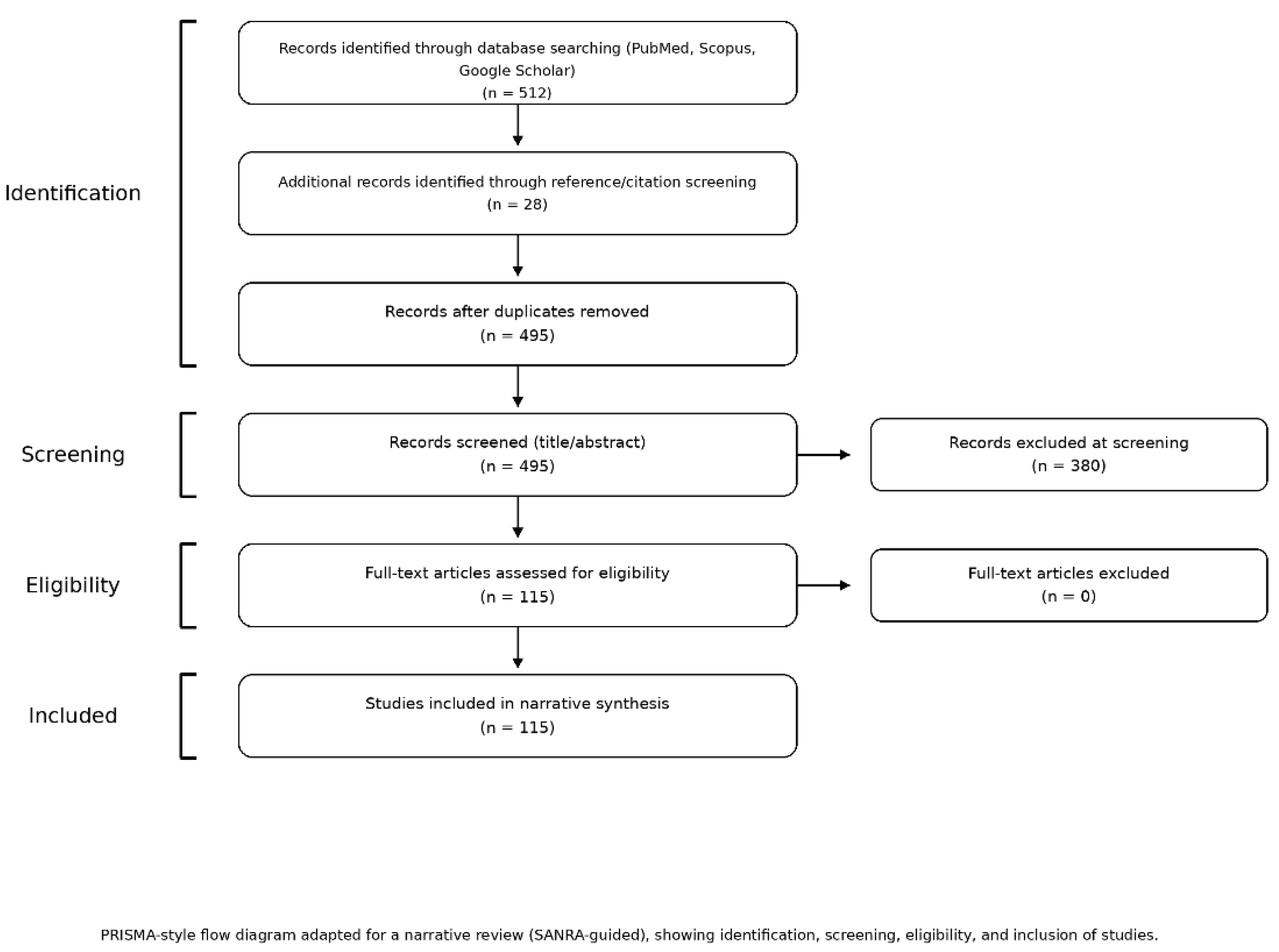

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Time frame: Publications from 2010 onwards (January 2010 through June 2025) to capture the last 15 years of research and current knowledge.

- Population focus: Studies involving preterm infants (typically <37 weeks gestation or low birth weight neonates) with outcomes related to bone health, osteopenia of prematurity, or metabolic bone disease.

- Intervention/Exposure: Research examining nutritional factors or interventions – including enteral nutrition (e.g., breast milk fortification, preterm formulas, nutritional supplements), parenteral nutrition strategies, or specific nutrients (calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, etc.) – and their impact on bone mineralization or the risk of osteopenia/rickets in the target population.

- Article types: Given the narrative scope, a wide range of scientific literature was eligible. This included peer-reviewed original research articles (randomized trials, observational cohort or case–control studies, cross-sectional studies), clinical reviews and meta - analyses, relevant animal studies providing mechanistic insight, clinical guidelines or protocols, and other authoritative sources (such as textbook chapters or official reports on neonatal nutrition), provided they contained pertinent data on nutrition and bone outcomes.

- Availability: Full-text access had to be available for assessment (through academic databases or institutional access), to ensure we could thoroughly review the methods and results.

- Exclusion criteria were applied to omit sources that were not relevant or of insufficient quality:

- Outside time frame: Articles published before 2010 (older than 15 years) were generally excluded, to focus on up-to-date evidence (unless identified as a seminal study in reference scanning).

- Language: Publications in languages other than English or Polish were excluded, due to the feasibility of analysis and to avoid translation-related biases.

- Non-peer-reviewed literature: We excluded letters to the editor, editorials, opinion pieces, and other non–non-peer-reviewed reports, as well as anecdotal case reports lacking robust data.

- Out-of-scope content: Studies that did not directly address the interplay between nutrition and bone health in preterm infants were excluded. For example, we omitted papers focused on technical complications of feeding (such as intravenous extravasation injuries during parenteral nutrition administration or methods of drug delivery via feeding tubes) and studies examining unrelated outcomes of enteral feeding (e.g., gastrointestinal complications not tied to bone metabolism). Such topics were beyond the scope of this review.

- Quality concerns: If a study’s methodology or data quality was notably poor or if essential details were unavailable, we chose to exclude it in order to base our review on reliable evidence. In practice, all included sources were screened to ensure they met a minimum standard of scientific credibility (clear objectives, appropriate methodology, and reasonable sample size or rationale).

Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results—Focus and Human Evidence

Human Studies: Nutritional Interventions and Bone Outcomes

- Early fortified enteral feeding improves bone outcomes. In a comparison of preterm infants fed unfortified breast milk vs fortified/supplemented feeds, rickets occurred in 40% without fortification vs 16% with fortification; serum phosphate was lower in the unfortified group (Bandara 2010). In a NICU cohort, 41% had osteopenia at 1 month (ALP > 900 IU/L); lack of HMF and irregular/no vitamin D use were over-represented among osteopenic infants (Bijari 2019).

- Prolonged parenteral nutrition and delayed enteral advancement are associated with osteopenia. In a prospective series of <1250 g infants, osteopenia cases had longer TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition) (≈ 11 vs 6 days), later transition to enteral feeding (≈ 27 vs 32 days) of enteral nutrition by 6 weeks), and lower protein intake (Mohamed 2020). A larger cohort of <30 weeks’ gestation infants reported 30.9% MBD with lower early Ca, P, vitamin D, and protein intakes, more PN exposure, and greater illness burden (Viswanathan 2014).

- Optimizing mineral delivery reduces MBD incidence. A unit-level quality-improvement program introducing higher Ca:P in TPN from day 1 and routine HMF from ~day 14 reduced MBD from 35% to <20% (Sureshchandra 2025).

Animal and Experimental Evidence

3.1. Nutritional Treatment - Definition, Classification, Characteristics

3.2. Osteopenia of Prematurity - Symptoms, Risk, Factors, Diagnosis

3.3. The Role of Nutritional Intervention in Preterm Infants

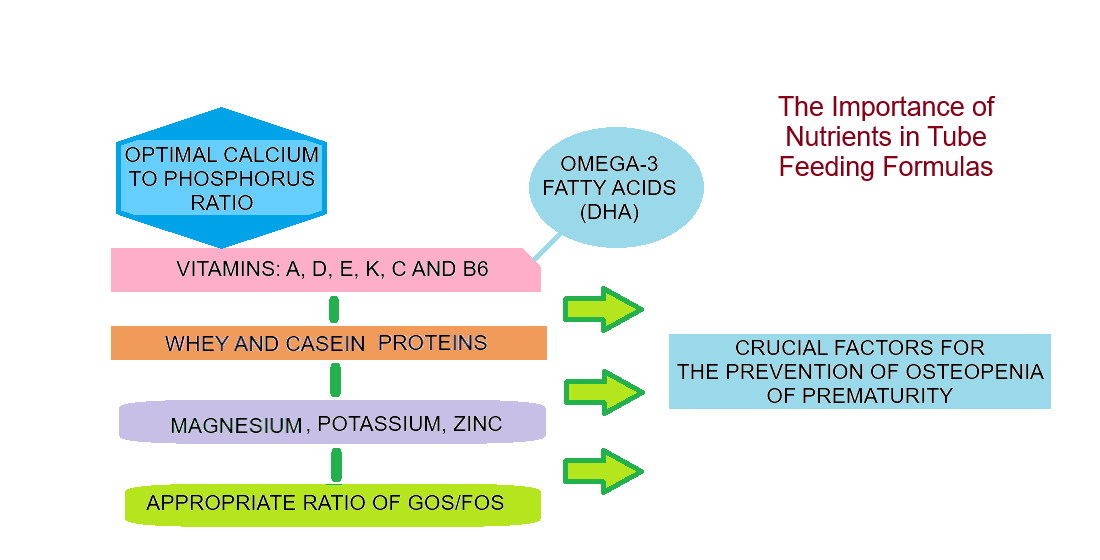

3.4. The Significance of Nutrients Found in Milk Mixtures for Preemies

3.4.1. Nutrients That Improve the Bioavailability of

3.4.1.1. Calcium

3.4.1.2. Zinc

3.4.1.3. Phosphorus

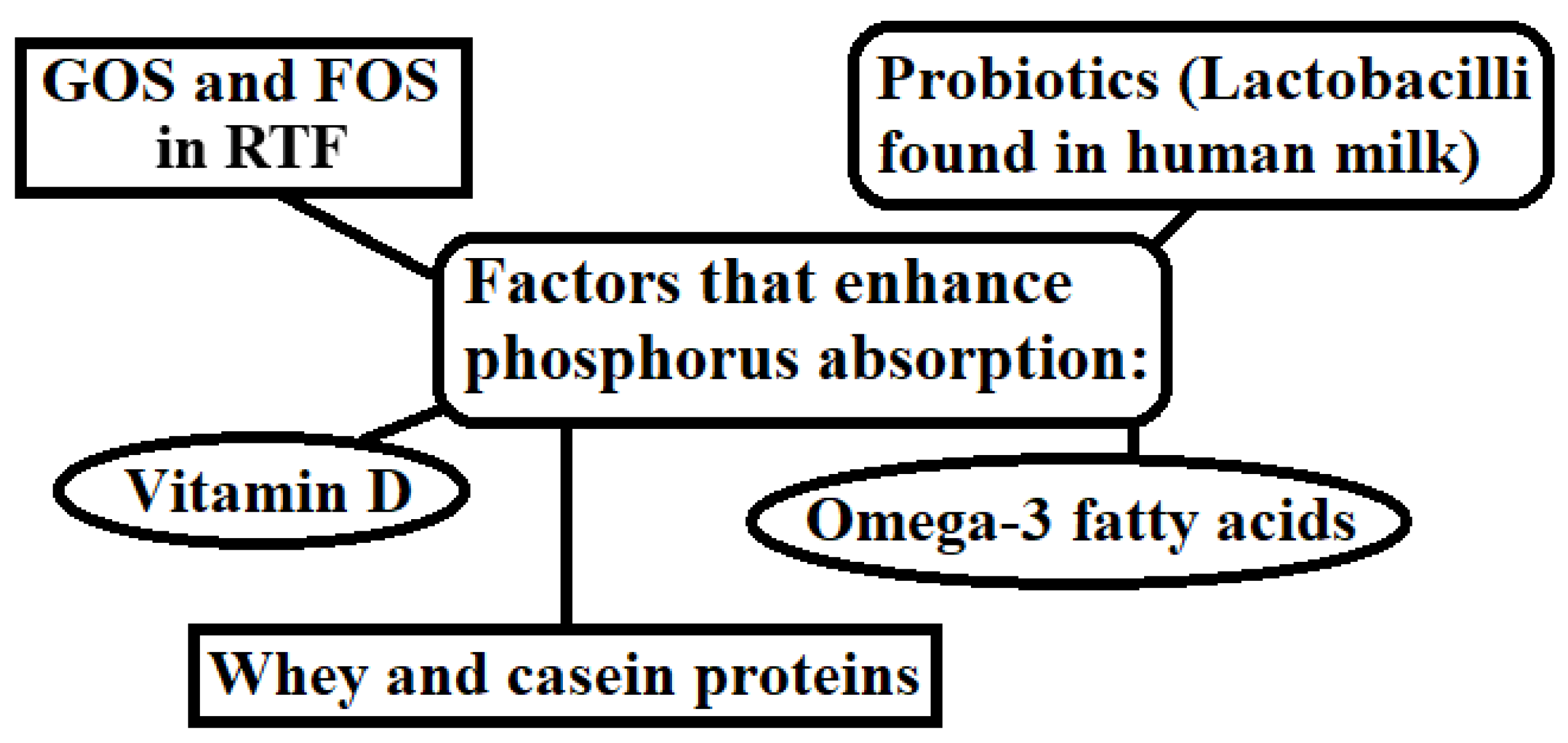

3.5. The Role of Phosphorus in Calcium Absorption

3.6. The Importance of ω-3 Fatty Acids for the Bioavailability of Calcium and Phosphorus

3.7. Vitamin D3: Factors That Increase Its Uptake and Its Role

3.8. Research Findings Highlighting the Significance of Nutrients in the Nutritional Treatment of Preterm Infants

3.9. Interaction of Nutrients in Enteral Feeding for Preterm Infants

3.10. Practice Points for NICU Teams (Concise, Evidence-Informed)

- Initiate fortified human milk early once minimal feeds are tolerated; target Ca:P ≈ 1.6–1.8, adequate protein (~3.5–4 g/kg/day), and vitamin D per local guidance.

- Minimize duration of exclusive PN where feasible; ensure adequate Ca:P in PN from day 1 per unit protocol.

- Monitor phosphate and ALP using consistent thresholds; address low 25(OH)D and low P promptly.

- Standardize protocols (nutrition + monitoring) through multidisciplinary NICU teams; audit OOP/MBD incidence over time.

3.11. Research Agenda

- Consensus OOP/MBD definitions (biochemical cut-offs + imaging) for preterm infants.

- Multicenter protocols comparing fortification strategies and PN mineral targets.

- Longitudinal follow-up into childhood/adolescence to link early nutrition to bone mass/fracture outcomes.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kłęk, S.; Kapała, A. Nutritional treatment. Varia Medica 2019, 3, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ciborowska, H.; Rudnicka, A. Nutrition for preterm and low birth weight infants. Dietetics. Nutrition of healthy and sick man; Medical Publishing House PZWL Warsaw, Poland, 2016; 515-520.

- Westin, V.; Klevebro, S.; Domellöf, M.; Vanpée, M.; Hallberg, B.; Sjöström, E.S. Improved nutrition for extremely preterm infants - a population-based observational study. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2018, 23, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelika, D.; Etika, R.; Mapindra, M. P.; Utomo, M. T.; Rahardjo, P.; Ugrasena, D. I. G. Associated neonatal and maternal factors of osteopenia of prematurity in low resource setting: A cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2021, 64, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Rychter, A.M.; Zawada, A.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Nutrients in the Prevention of Osteoporosis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B. C. F.; Lima, L. M.; Moreira, M. E. L.; Priore, S. E.; Henriques, B. D.; Carlos, C. F. L. V.; Sabino, J. S. N.; Franceschini, S. D. C. C. Micronutrient supplementation adherence and influence on the prevalences of anemia and iron, zinc and vitamin A deficiencies in preemies with a corrected age of six months. Clinics 2016, 71, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciborowska, H.; Rudnicka, A. Nutritional treatment. Dietetics. Nutrition of healthy and sick man; Medical Publishing House PZWL Warsaw, Poland, 2016; 359-370.

- Osteopenia - premature infants. Neonatal rickets; Brittle bones - premature infants; Weak bones - premature infants; Osteopenia of prematurity. https://ssl.adam.com/content.aspx?productid=617&pid=1&gid=007231&site=makatimed.adam.com&login=MAKA1603 (06-01-2025).

- Pinto, M. R. C.; Machado, M. M. T.; de Azevedo, D. V.; Correia, L. L.; Leite, Á. J. M.; Rocha, H. A. L. Osteopenia of prematurity and associated nutritional factors: case–control study. BMC pediatrics 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshchandra, S.; Maheshwari, R.; Nowland, T.; Elhindi, J.; Rundjan, L.; D’Cruz, D.; Luig, M.; Shah, D.; Lowe, G.; Baird, J.; Jani, P.R. Implementation of Parenteral Nutrition Formulations with Increased Calcium and Phosphate Concentrations and Its Impacton Metabolic Bone Disease in Preterm Infants: A Retrospective Single-Centre Study. Children 2025, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, Y.; Oh, S.; Heo, J. S. Risk factors and outcomes of vitamin D deficiency in very preterm infants. Pediatrics and Neonatology 2025, 66, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabiel, N.; Nugroho, H. W.; Moelyo, A. G. Vitamin D Deficiency is Associated with Hypocalcemia in Preterm Infants. Molecular and Cellular Biomedical Sciences 2024, 8, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Jiang, D.; Shi, G.; Song, Y. The association between dietary zinc intake and osteopenia, osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2024, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FUROSEMIDE injection, for intravenous or intramuscular use Initial U.S. Approval: 1982 https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/018267s029lbl.pdf (Revised: 10/2024).

- Mohn, E.S.; Kern, H.J.; Saltzman, E.; Mitmesser, S.H.; McKay, D.L. Evidence of Drug–Nutrient Interactions with Chronic Use of Commonly Prescribed Medications: An Update. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ali, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sohail, S.; Saleem, S.M.; Khan, M.; Naz, F.; Khan, W.A.; Salat, M.S.; Hussain, K.; Ambreen, G. Relationship of caffeine regimen with osteopenia of prematurity in preterm neonates: a cohort retrospective study. BMC Pediatrics 2022, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyona 20 mg/mL solution for infusion and oral solution. Summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/peyona-epar-product-information_en.pdf (03-03-2014).

- Wada, Y.; Hisamatsu, T.; Naganuma, M.; Matsuoka, K.; Okamoto, S.; Inoue, N.; Yajima, T.; Kouyama, K.; Iwao, Y.; Ogata, H.; Hibi, T.; Abe, T.; Kanai, T. Risk factors for decreased bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Nutrition 2015, 34, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekimoğlu, B. S. Risk factors and clinical features of osteopenia of prematurity: Single-center experience. Trends in Pediatrics 2023, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakova, N.A.; Abramova, I.V.; Rybasova, V.P.; Trukhina, I.Y.; Lukina, L.V.; Nasyrova, R.F.; Mikhailov, V.A.; Mazo, G.E. The Effect of Anticonvulsants on Bone Mineral Density: Brief Review. Personalized Psychiatry and Neurology 2023, 3, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.B.; Rhu, M.; Jung, J.; Jeon, G.W.; Sin, J. A Comparative Study of Two Different Heel Lancet Devices for Blood Collection in Preterm Infants. Journal of the Korean Society of Neonatology 2010, 17, 239–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, R.A.R.; Remaley, A.T. Interferences from blood collection tube components on clinical chemistry assays. Biochemia Medica 2014, 24, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraszula, Ł.; Eusebio, M.; Pietruczuk, M.; Kuna, P. Serum stability of sodium, potasium and chloride concentration.

- in special tubes containing separator and clotting activator. Laboratory Diagnostics 2018, 54, 23–28.

- Lokossou, G.A.G.; Kouakaniu, L.; Schumacher, A.; Zenclussen, A.C. Human Breast Milk: From Food to Active Immune Response With Disease Protection in Infants and Mothers. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, L.F.; George, A.; Gridneva, Z.; Jin, X.; Lai, C.T.; Geddes, D.T. Effects of Different Thawing and Warming Processes on Human Milk Composition. The Journal of Nutrition 2024, 154, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królak-Olejnik, B.; Czosnykowska-Łukacka, M. Nutrition of a newborn born prematurely after discharge from a neonatal unit. Neonate born prematurely patient of a primary care physician; Wroclaw Scientific Publishers Atla 2, Poland, 2018, 23-34.

- Dobosz, A.; Smektala, A. Osteoporosis-pathophysiology, symptoms, prevention and treatment. Polish Pharmacy 2020, 76, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan-Mei, C.; Xin-Zhu, L.; Rong, Z.; Xi-Hong, L.; Xiao-Mei, T.; Ping-Yang, C.; Zhi-Chun, F. Expert consensus on clinical management of metabolic bone disease of prematurity (2021). Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 2021, 23, 761–772. [Google Scholar]

- Dardzińska, J.; Chabaj-Kędroń, H.; Małgorzewicz, S. Osteoporosis as a social and civilisation disease-methods of prevention. Hygeia Public Health 2016, 51, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Salomão, N.A.; Geraldes, A.A.; Lima-Silva, A.E. Influence of lactose intolerance and physical activity level on bone mineral density in young women. Revista Brasileira de Educação Física e Esporte 2017, 31, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, E. F.; Moretti, D.; Ly, S. C.; Dekkers, R.; van den Heuvel, E. G.; Fitri, A.; Boelsma, E.; Stomph, T.J.; Zeder, C.; Melse-Boonstra, A. Zinc Absorption from Milk Is Affected by Dilution but Not by Thermal Processing, and Milk Enhances Absorption of Zinc from High-Phytate Rice in Young Dutch Women. The Journal of nutrition 2017, 147, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Park, B.; Yoon, D.S.; Kwon, S.-H.; Shin, D.M.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, H.G.; Shim, J.-H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.M. Zinc inhibits osteoclast differentiation by suppression of Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc1 signaling pathway. Cell Communication and Signaling 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, J.; Hwang, J.H. Caffeine-induced hypokalemia: a case report. BMC Nephrology 2021, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melse-Boonstra, A. Bioavailability of Micronutrients From Nutrient-Dense Whole Foods: Zooming in on Dairy, Vegetables, and Fruits. Frontiers in Nutrition 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavado-García, J.; Roncero-Martin, R.; Moran, J.M.; Pedrera-Canal, M.; Aliaga, I.; Leal-Hernandez, O.; Rico-Martin, S.; Canal-Macias, M.L. Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid dietary intake is positively associated with bone mineral density in normal and osteopenic Spanish women. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maditz, K.H.; Smith, B.J.; Miller, M.; Oldaker, C.; Tou, J.C. Feeding soy protein isolate and oils rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids affected mineral balance, but not bone in a rat model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. BMC Nephrology 2015, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelli, V.; D’Incecco, P.; Pellegrino, L. Vitamin D Incorporation in Foods. Formulation Strategies, Stability, and Bioaccessibility as Affected by the Food Matrix. Foods 2021, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, A.; Razzaque, M. S. Zinc and its role in vitamin D function. Current research in physiology 2022, 5, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balwierz, R.; Madej, A. How can you prevent vitamin and mineral deficiencies while taking medication. Pharmacotherapy. When Food Matters. Drug-Food Interactions in Dietetics; University Publishing House Opole, Poland, 2023; 1, 131-140.

- Bahman, B. B.; Salmeei, S.; Niknafs, P.; Jamali, Z.; Mousavi, H.; Sabzevari, F.; Daee, Z.; Mehdi, B. M. Osteopenia of prematurity and its meternal and nutrition-related factors among preterm infants admitted to the NICU department of Afzalipour Medical Center. Journal of Kerman University of Medical Sciences 2023, 30, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, S.A. Vitamin D in Preterm and Full-Term infants. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2020, 76, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Kamleh, M.; Muzzy, J.; Groh-Wargo, S.; Abu-Shaweesh, J. Association of Protein and Vitamin D Intake With Biochemical Markers in Premature Osteopenic Infants: A Case-Control Study. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2020, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; D’Amato, E.; Natale, M.P.; Grano, M.; Chiarito, M.; Brunetti, G.; D’Amato, G. Metabolic Bone Disease of Prematurity: Diagnosis and Management. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Khasawneh, W.; McNelis, K.; Dykstra, C.; Amstadt, R.; Super, D.M.; Groh-Wargo, S.; Kumar, D. Metabolic bone disease: a continued challenge in extremely low birth weight infants. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2014, 38, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithika, M. V.; Balakrishnan, U.; Amboiram, P.; Shaik, M. S. J.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Ninan, B. Early calcium and phosphorus supplementation in VLBW infants to reduce metabolic bone disease of prematurity: a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Quality 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, A.L.; Siener, R. The Efficacy of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids as Protectors against Calcium Oxalate Renal Stone Formation: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbahnasawy, A.S.; Valeeva, E.R.; El-Sayed, E.M.; Stepanova, N.V. Protective effect of dietary oils containing omega-3 fatty acids against glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Journal of Nutrition and Health 2019, 52, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin - Bautista, E.M.; Muñoz - Torres, J.; Fonolla, M.; Quesada, A.; Poyatos, A.; Lopez – Huertas, E. Improvement of Bone Formation Biomarkers After 1- Year Consumption With Milk Fortified With Eicosapentaenoic Acid, Docosahexaenoic Acid, Oleic Acid, and Selected Vitamins. Nutrition Research 2010, 30, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Goldberg, G.R.; Raqib, R.; Roy, S.K.; Haque, S.; Braithwaite, V. S.; Pettifor, J.M.; Prentice, A. Aetiology of nutritional rickets in rural Bangladeshi children. Bone 2020, 136, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbová, D.; Švábová, P.; Beňuš, R.; Hozáková, A.; Sulis, S.; Vorobeľová, L. Association Between Self-Reported Lactose Intolerance, Additional Environmental Factors, and Bone Mineral Density in Young Adults. American Journal of Human Biology 2025, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N. D.; et al. Enteral nutrition in preterm infants (2022): a position paper from the ESPGHAN committee on nutrition and invited experts. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2023, 76, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenda, M.; Kolmas, J. K. The Role of Zinc in Bone Tissue Health and Regeneration—a Review. Biological Trace Element Research 2023, 201, 5640–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Gomis, R.; Bosch-Gimenez, V.; Juste-Ruiz, M.; Vázquez-Gomis, C.; Izquierdo-Fos, I.; Pastor-Rosado, J. Zinc concentration in preterm newborns at term age, a prospective observational study. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2019, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, L.; Qi, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Dual function of magnesium in bone biomineralization. Advanced healthcare materials 2019, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihatsch, W.; Fewtrell, M.; Goulet, O.; Molgaard, C.; Picaud, J. C.; Senterre, T. ESPGHAN/ESPEN/ESPR/CSPEN guidelines on pediatric parenteral nutrition: calcium, phosphorus and magnesium. Clinical Nutrition 2018, 37, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavani, Z,; Asadi, A. H.; Shamshirgardi, E.; Akbarzadeh, M. Vitamin D, Magnesium and Their Interactions: A Review. International Journal of Nutrition Sciences 2021, 6, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, A. Correlation of serum magnesium and vitamin D levels in patients attending a tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Academic Medicine and Pharmacy 2025, 7, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.; Mohammed, A. Magnesium: The Forgotten Electrolyte—A Review on Hypomagnesemia. Medical Sciences 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, V.; Vergatti, A.; Altavilla, N.; Garofano, F.; Salcuni, A.S.; Rendina, D.; De Filippo, G.; Vescini, F.; D’Elia, L. Potassium Intake and Bone Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, W.; Kushwaha, P. Potassium: a frontier in osteoporosis. Hormone and Metabolic Research 2024, 56, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humalda, J. K.; et al. Effects of potassium or sodium supplementation on mineral homeostasis: a controlled dietary intervention study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2020, 105, e3246–e3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, M.M.F.; Chin, K.-Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S.; Wong, S.K. Vitamin A and Bone Health: A Review on Current Evidence. Molecules 2021, 26, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khojah, Q.; AlRumaihi, S.; AlRajeh, G.; Aburas, A.; AlOthman, A.; Ferwana, M. Vitamin A and its dervatives effect on bone mineral density, a systematic review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2021, 10, 4089–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samedi, V.; Abdul Aziz, A.; AlJouburi, S.; Mugarab-Samedi, N. Does vitamin K deficiency aggravate osteopenia in preterm infants: Case report and literature review. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 2019, 47, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Olleros Rodríguez, C.; Díaz Curiel, M. Vitamin K and Bone Health: A Review on the Effects of Vitamin K Deficiency and Supplementation and the Effect of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants on Different Bone Parameters. Journal of Osteoporosis 2019, 2019, 2069176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaseth, J.O.; Finnes, T.E.; Askim, M.; Alexander, J. The Importance of Vitamin K and the Combination of Vitamins K and D for Calcium Metabolism and Bone Health: A Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.; Khani, F.; Sturmlechner, I.; et al. Vitamin C epigenetically controls osteogenesis and bone mineralization. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanian, P.; Hall, S.; Wongworawat, M. D.; Mohan, S. The roles and mechanisms of actions of vitamin C in bone: new developments. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2015, 3, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Scotto di Carlo, F.; Gianfrancesco, F. The osteoclast traces the route to bone tumors and metastases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10, 886305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Peroni, G.; Fossari, F.; Vecchio, V.; Faliva, M.A.; Naso, M.; Perna, S.; Di Paolo, E.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; et al. Evidence of a Positive Link between Consumption and Supplementation of Ascorbic Acid and Bone Mineral Density. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, R.A.; Irwin, R.; Quach, D.; Schaefer, L.; Zhang, J.; Lee, T.; et al. Probiotic treatment with L. reuteri prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. Journal of cellular physiology 2014, 229, 1822–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K. C.; Samanta, S.; Mondal, S.; Mondal, S. P.; Mondal, K.; Halder, S. K. Navigating the frontiers of mineral absorption in the human body: Exploring the impact of probiotic innovations: Impact of probiotics in mineral absorption by human body. Indian Journal of Experimental Biology (IJEB) 2024, 62, 475–483. [Google Scholar]

- St-Jules, D. E.; Jagannathan, R.; Gutekunst, L.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Sevick, M. A. Examining the proportion of dietary phosphorus from plants, animals, and food additives excreted in urine. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2017, 27, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stremke, E.R.; Hill Gallant, K.M. Intestinal Phosphorus Absorption in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.; Mathew, S.; Patel, S.; Fordjour, L.; Chin, V.L. Genetic Disorders of Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism. Endocrines 2022, 3, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, D.; Costa, V.; De Luca, A.; Maglio, M.; Pagani, S.; Fini, M.; Giavaresi, G. Vitamin D level between calcium-phosphorus homeostasis and immune system: new perspective in osteoporosis. Current osteoporosis reports 2024, 22, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, L.J.; Veronese, N.; Guerrero-Romero, F.; Barbagallo, M. Magnesium in Infectious Diseases in Older People. Nutrients 2021, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentini, D.; Cappadone, C.; Farruggia, G.; Prata, C. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouteau, E.; Kabir-Ahmadi, M.; Noah, L.; Mazur, A.; Dye, L.; Hellhammer, J.; Pickering, G.; Dubray, C. Superiority of magnesium and vitamin B6 over magnesium alone on severe stress in healthy adults with low magnesemia: A randomized, single-blind clinical trial. PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0208454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maares, M.; Haase, H. A. Guide to Human Zinc Absorption: General Overview and Recent Advances of In Vitro Intestinal Models. Nutrients 2020, 12, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, L.I.; Ferrao, K.; Mehta, K.J. Role of zinc in health and disease. Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, A.; Dumanoğlu Doğan, İ.; Uyanık, M.; Köle, M. T.; Pişmişoğlu, K. The clinical significance of vitamin D and zinc levels with respect to immune response in COVID-19 positive children. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 2022, 68, fmac072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhang, J.; Regenstein, J. M.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, P. α-Lactalbumin: Functional properties and potential health benefits. Food Bioscience 2024, 60, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D. C.; Neto, H. A.; Lima, J. S.; de Assis, D. C.; Keller, K. M.; Campos, S. V.; Oliveira, D.A.; Fonseca, L. M. Determination of the lactose content in low-lactose milk using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and convolutional neural network. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, M.; D’amico, F.; Brigidi, P.; Turroni, S. Gut microbiome–micronutrient interaction: The key to controlling the bioavailability of minerals and vitamins? Biofactors 2022, 48, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratajczak, A.E.; Zawada, A.; Rychter, A.M.; Dobrowolska, A.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Milk and Dairy Products: Good or Bad for Human Bone? Practical Dietary Recommendations for the Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendołowicz, A.; Stefańska, E.; Ostrowska, L. Influence of selected dietary components on the functioning of the human nervous system. Annals of the National Institute of Hygiene 2018, 69, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mada, S. B.; Garba, N. A. Effect of Omega-3 Fatty acid on Osteoanabolic Markers and Bone-resorbing Cytokines in Ovariectomized Rats. Journal of Innovative Research in Life Sciences 2024, 6, 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgou, D.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P.; Katapodis, P.; Matsakas, L.; Patel, A. Benefits of supplementation with microbial omega-3 fatty acids on human health and the current market scenario for fish-free omega-3 fatty acid. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2023, 136, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Abou-Saleh, H.; Rahman, M.M. Unraveling the Omega-3 Puzzle: Navigating Challenges and Innovations for Bone Health and Healthy Aging. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, T. Fat-soluble vitamins: Essential nutrients for human health. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2024, 13, 71–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Lin, Z. Y.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Y. X.; Yang, S. Q.; Guo, J. L.; Zhang, S.; Sun, D. L. A cross-sectional study on the effect of dietary zinc intake on the relationship between serum vitamin D3 and HOMA-IR. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 945811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleizgys, A. Zinc, Magnesium and Vitamin K Supplementation in Vitamin D Deficiency: Pathophysiological Background and Implications for Clinical Practice. Nutrients 2024, 16, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemińska, M.; Sieklucka, B.; Pawlak, K. Vitamin K and D Supplementation and Bone Health in Chronic Kidney Disease—Apart or Together? Nutrients 2021, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingess, K.A.; Gazi, I.; van den Toorn, H.W.P.; Mank, M.; Stahl, B.; Reiding, K.R.; Heck, A.J.R. Monitoring Human Milk? - Casein Phosphorylation and O-Glycosylation Over Lactation Reveals Distinct Differences between the Proteome and Endogenous Peptidome. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnerdal, B. Bioactive proteins in human milk: Health, nutrition, and implications for infant formulas. The Journal of pediatrics 2016, 173, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allawi, A. A. D.; Alwardi, M. A. W.; Altemimi, H. M. Effects of Omega-3 on vitamin D activation in Iraqi patients with chronic kidney disease treated by maintenance hemodialysis. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2017, 9, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Rodzik, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Sagandykova, G.N.; Buszewski, B. Interactions of Whey Proteins with Metal Ions. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.G.; King, J.C. The Molecular Basis for Zinc Bioavailability. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, G.; Wang, J. Novel casein-derived peptide-zinc chelate: zinc chelation and transepithelial transport characteristics. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2023, 71, 6978–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Z.; Yuan, J.; Li, D. Biological activity of galacto-oligosaccharides: A review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 993052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G. T.; Vasconcelos, Q. D. J. S. .; Abreu, G. C.; Albuquerque, A. O.; Vilar, J. L.; Aragão, G. F. Systematic review of the ingestion of fructooligosaccharides on the absorption of minerals and trace elements versus control groups. Clinical nutrition ESPEN 2021, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijo, M.; Bryk, G.; Zeni Coronel, M.; et al. Effect of Adding a Galacto-Oligosaccharides/Fructo-Oligosaccharides (GOS/FOS®) Mixture to a Normal and Low Calcium Diet, on Calcium Absorption and Bone Health in Ovariectomy-Induced Osteopenic Rats. Calcified Tissue International 2019, 104, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, D.; Misra, S.; Mohapatra, S.; Sahu, P. S. Prebiotics and synbiotics: Recent concepts in nutrition. Food bioscience 2018, 26, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilesanmi-Oyelere, B. L.; Kruger, M. C. The role of milk components, pro-, pre-, and synbiotic foods in calcium absorption and bone health maintenance. Frontiers in Nutrition 2020, 7, 578702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadim, M.; Darma, A.; Kartjito, M.S.; Dilantika, C.; Basrowi, R.W.; Sungono, V.; Jo, J. Gastrointestinal Health and Immunity of Milk Formula Supplemented with a Prebiotic Mixture of Short-Chain Galacto-oligosaccharides and Long-Chain Fructo-Oligosaccharides (9:1) in Healthy Infants and Toddlers: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition 2025, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, G.; Coronel, M. Z.; Lugones, C.; et al. Effect of a mixture of GOS/FOS® on calcium absorption and retention during recovery from protein malnutrition: experimental model in growing rats. European journal of nutrition 2016, 55, 2445–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.; Mattia, C.; Decembrino, N.; Polizzi, A.; Ruggieri, M.; Betta, P. The Critical Role of Vitamin D Supplementation for Skeletal and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Neonates. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, M.; Ashraf, A. P.; Bowden, S. A.; Calabria, A.; Diaz-Thomas, A.; Krishnan, S.; Miller, J.L.; Robinson, M.E.; DiMeglio, L. A. Invited mini review metabolic bone disease of prematurity: overview and practice recommendations. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2025, 98, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saif, S.A.; Maghoula, M.; Babiker, A.; Abanmi, M.; Nichol, F.; Al Enazi, M.; Guevarra, E.; Sehlie, F.; Al Shaalan, H.; Mughal, Z. A Multidisciplinary and a Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Fragility Fractures in Preterm Infants. Current Pediatric Reviews 2024, 20, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Study (Year) |

Design / Sample |

Intervention / Comparison |

Key findings |

| Bandara (2010) | Retrospective; preterm infants | Breast milk with vs without fortification/ supplementation |

Rickets: 40% without vs 16% with fortification; lower serum phosphate without fortification. |

| Bijari (2019) | Cross-sectional; NICU n = 100 | HMF use vs none among breast-fed | Osteopenia (ALP > 900 IU/L): 41%; 78% of osteopenic infants had no Ca:P supplements; vitamin D regular use 32% vs 88% in non-osteopenic. |

| Mohamed (2020) | Prospective case – control; <1250 g, n = 26 |

Early nutrition in osteopenia vs non-osteopenia |

TPN: 11 vs 6 days; enteral by 6 weeks: 27 vs 32 days; 25(OH)D: 21 vs 39 ng/mL; protein lower in osteopenia. |

| Viswanathan (2014) | Retrospective cohort; <30 weeks, n = 230 | Nutrient intake and outcomes (MBD vs no MBD) | MBD 30.9%; lower early Ca, P, vitamin D, protein; more PN, BPD, steroids/diuretics; mortality 14.1% vs 4.4%. |

| Sureshchandra (2025) | Pre–post QI in VLBW | Higher Ca:P in TPN day 1 + HMF by ~day 14 | MBD decreased from 35% to <20% after implementation. |

| Study | Osteopenia definition/ incidence |

Sample characteristics |

Nutrition exposure |

Outcomes (osteopenia vs comparison) |

| Bandara 2010 | Radiographic rickets: 40% (no fortifier) vs 16% (fortified) | Preterm infants (details not reported) |

Unfortified breast milk vs fortified/ supplemented |

Lower phosphate and higher rickets without fortification. |

| Bijari 2019 | ALP > 900 IU/L at 1 month: 41% |

NICU preterms n = 100 |

HMF absent vs present; vitamin D irregular/ none vs regular |

Higher osteopenia with no HMF; vitamin D regular 32% vs 88%. |

| Mohamed 2020 | DXA/radiographic evidence by 6 weeks: 50% | <1250 g, n = 26 | Longer TPN, lower protein, later enteral | TPN: 11 vs 6 days; 25(OH)D: 21 vs 39 ng/mL; shorter enteral duration. |

| Viswanathan 2014 | Radiographic MBD or ALP > 500 IU/L: 30.9% | <30 weeks, n = 230 | Lower early Ca/P/vit D/protein; more PN and meds | Higher mortality (14.1% vs 4.4%), BPD, cholestasis. |

| Sureshchandra 2025 | Unit incidence: 35% → <20% | VLBW infants (QI cohort) |

Early Ca:P in TPN + HMF protocol | Lower MBD after protocol adoption. |

| Nutrient | Effects on Skeletal Development |

| Zinc | Zinc plays a crucial role in the deposition of citrate in bone apatite, which facilitates bone mineralization. This happens because citrate stabilizes liquid calcium phosphate precursors and enriches collagen fibers [52]. A study conducted by Vázquez-Gomis R. examined preterm infants and found a positive correlation between the z-score of bone mineral density relative to body length and serum Zn concentration at discharge. The results suggest that Zn plays a crucial role in bone growth [53]. |

| Magnesium | Crucial for growth and the mineralization of bone [54]. The release of parathormone (PTH) is triggered by conditions that prevent the occurrence of hypocalcemia [55]. It plays a role in the biosynthesis, transport, and activation of cholecalciferol as a cofactor [56]. Joseph A.’s research indicated a rise in serum magnesium levels that was directly proportional to vitamin D levels in humans [57]. Helps prevent the loss of potassium [58]. |

|

Potassium Citrate in RTF |

Jehle et al. demonstrated that potassium citrate significantly ↓ decreases the excretion of calcium in urine [59]. |

| Potassium | Encourages the development and maturation of cells responsible for bone formation [60]. The study by Humald J.K. et al. indicated that potassium supplementation led to increased phosphate reabsorption [61]. |

|

Retinol (Vitamin A) |

A study by Choi M.J. indicates a connection between osteopenia and retinol deficiency, suggesting that vitamin A may help protect against osteopenia [62]. Essential for bone development, as it promotes the differentiation of cells that form bone [63]. |

| Vitamin K | M-Samedi V. and colleagues demonstrate that vitamin K inhibits bone turnover in infants [64]. Vitamin K plays a key role in synthesizing osteocalcin, which regulates bone structure and growth [65]. Menaquinone K2 activates osteocalcin, which transports calcium from the blood to the bones, positively affecting bone mineralization [66]. |

|

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid, AA) |

AA plays a vital role in the differentiation of osteoblasts [67]. Vitamin C is essential for the apoptosis of osteoclasts, the cells that degrade bone tissue [68,69]. The research by Martínez-Ramírez M.J. reveals an inverse correlation between blood AA levels and the likelihood of bone fractures [70]. |

|

Probiotics (Lactobacilli found in human milk) |

The results of Britton’s study show that probiotics ↓ the quantity of osteoclasts [71]. Probiotic bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids, which increase the solubility of calcium, magnesium, and zinc, which are crucial for bone development [72]. |

| Prebiotics (GOS) in RTF | Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) reduce the pH in the large intestine, which enhances passive calcium absorption and stimulates bone mineralization [101]. |

| Nutrient | Factors that increase bioavailability | References |

| Potassium | Probiotics (Lactobacilli found in human milk) | [72] |

| Phosphorous | Vitamin D (Cholecalciferol) |

[73,74,75] |

| Calcium | [75,76] | |

| Magnesium | [77] | |

|

Magnesium |

Peptides from casein or whey | [78] |

| Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | [79] | |

| Zinc | Citrates found in human milk | [80,81] |

| Vitamin D | Zinc | [82] |

| Calcium | Alpha-lactalbumin (alpha-LA) present in human milk | [83] |

|

Calcium Magnesium |

Lactose |

[84] |

|

Zinc Magnesium |

Probiotics (La[85,86ctobacilli found in human milk) | [85,86] |

| Calcium Phosphorus | [86] | |

| Zinc | Vitamin A and E | [87] |

| Calcium | ω-3 fatty acids | [88,89,90] |

| Vitamins: A, D, E, K | Lipids | [91] |

| Zinc | Vitamin D | [92] |

| Vitamin D | Magnesium | [93] |

| Calcium | Vitamin K | [94] |

|

Zinc Calcium |

Casein proteins in human milk/HMF | [95,96] |

| Vitamin D | ω-3 fatty acids | [97] |

| Zinc | Whey protein (alpha-LA), peptides from casein | [98,99,100] |

| Calcium | Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) in RTF | [101] |

|

Calcium Magnesium Zinc |

Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) in RTF | [102] |

|

Magnesium Phosphorus |

GOS and FOS in RTF | [103] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).