Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. The Multiple Facades of Lupus Nephritis

1.1. General Overview

1.2. The Central Role of the Histopathological Classification

1.3. Dynamic Class Switching in Repeat Biopsies

2. Pure Membranous Lupus Nephritis

2.1. Introduction to Pure Membranous Lupus Nephritis

2.2. Clinical Phenotype of Pure Membranous Lupus Nephritis

2.3. Pathogenesis: How Membranous Lupus Nephritis Leads to Kidney Injury

2.4. Towards Precision Medicine: Biomarkers in Membranous Lupus Nephritis

2.5. Long-Term Renal Outcomes in Membranous Lupus Nephritis: Risk Factors and Survival

2.6. Comparative Outcomes: Pure Membranous vs Proliferative/Mixed Lupus Nephritis

2.7. Therapeutic Strategies for Membranous Lupus Nephritis: From Guidelines to Clinical Practice

3. Current Management and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gensous N, Boizard-Moracchini A, Lazaro E, Richez C, Blanco P. Update on the cellular pathogenesis of lupus. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021, 33, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, CC. Towards new avenues in the management of lupus glomerulonephritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016, 12, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok CC, Tang SSK. Incidence and predictors of renal disease in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med 2004, 117, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanly JG, O’Keeffe AG, Su L, et al. The frequency and outcome of lupus nephritis: results from an international inception cohort study. Rheumatology 2016, 55, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh S, V. , Almaani S, Brodsky S, Rovin BH. Update on Lupus Nephritis: Core Curriculum 2020. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2020, 76, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajema IM, Wilhelmus S, Alpers CE, et al. Revision of the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification for lupus nephritis: clarification of definitions, and modified National Institutes of Health activity and chronicity indices. Kidney Int 2018, 93, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Vercelloni PG, Quaglini S, et al. Changing patterns in clinical–histological presentation and renal outcome over the last five decades in a cohort of 499 patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018, 77, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin BH, Caster DJ, Cattran DC, et al. Management and treatment of glomerular diseases (part 2): conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2019, 95, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto M, Frontini G, Calatroni M, et al. Effect of Sustained Clinical Remission on the Risk of Lupus Flares and Impaired Kidney Function in Patients With Lupus Nephritis. Kidney Int Rep 2024, 9, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Gatto M, Tamborini F, et al. Lack of EULAR/ERA-EDTA response at 1 year predicts poor long-term renal outcome in patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020, 79, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri M, Orbai A-M, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019, 78, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzzo M, Kronbichler A, Alberici F, Bajema I. Nonlupus Full House Nephropathy: A Systematic Review. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2024, 19, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudose S, Santoriello D, Bomback AS, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD, Markowitz GS. Sensitivity and Specificity of Pathologic Findings to Diagnose Lupus Nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 14, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Porata G, Raffiotta F, et al. Beyond ISN/RPS Lupus Nephritis Classification: Adding Chronicity Index to Clinical Variables Predicts Kidney Survival. Kidney360 2022, 3, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004, 15, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHURG J BJGR. Renal Disease: Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Diseases. 1995, 2nd ed.

- Sloan R, Schwartz M, Korbet S, Borok R. Long-Term Outcome in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Membranous Glomerulonephritis1 [Internet]. 1996. Available from: http://journals.lww.

- Mercadal L, Tézenas du Montcel S, Nochy D, et al. Factors affecting outcome and prognosis in membranous lupus nephropathy [Internet]. Available from: https://academic.oup. 1771.

- Colvin RB and AChang. Diagnostic Pathology: Kidney Diseases. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Moroni G, Quaglini S, Gravellone L, et al. Membranous Nephropathy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Long-Term Outcome and Prognostic Factors of 103 Patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012, 41, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharouf F, Li Q, Whittall Garcia LP, Jauhal A, Gladman DD, Touma Z. Short- and long-term outcomes of patients with pure membranous lupus nephritis compared with patients with proliferative disease. Rheumatology.

- Gasparotto M, Gatto M, Binda V, Doria A, Moroni G. Lupus nephritis: clinical presentations and outcomes in the 21st century. Rheumatology.

- Hahn BH, McMahon MA, Wilkinson A, et al. American College of Rheumatology guidelines for screening, treatment, and management of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok CC, Teng YKO, Saxena R, Tanaka Y. Treatment of lupus nephritis: consensus, evidence and perspectives. Nat Rev Rheumatol.

- Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Cheema K, et al. 2019 Update of the Joint European League against Rheumatism and European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020, 79, S713–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh S, V. , Almaani S, Brodsky S, Rovin BH. Update on Lupus Nephritis: Core Curriculum 2020. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2020, 76, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Depetri F, Ponticelli C. Lupus nephritis: When and how often to biopsy and what does it mean? J Autoimmun 2016, 74, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatto M, Radice F, Saccon F, et al. Clinical and histological findings at second but not at first kidney biopsy predict end-stage kidney disease in a large multicentric cohort of patients with active lupus nephritis. Lupus Sci Med 2022, 9, e000689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava A, Fenaroli P, Rosenberg A, et al. History of proliferative glomerulonephritis predicts end stage kidney disease in pure membranous lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 2022, 61, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Fernández L, Otón T, Askanase A, et al. Pure Membranous Lupus Nephritis: Description of a Cohort of 150 Patients and Review of the Literature. Reumatol Clin 2019, 15, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok CC, Ying KY, Lau CS, et al. Treatment of Pure Membranous Lupus Nephropathy with Prednisone and Azathioprine: An Open-Label Trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2004, 43, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin HA, Illei GG, Braun MJ, Balow JE. Randomized, controlled trial of prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine in lupus membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009, 20, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatroni M, Conte E, Stella M, De Liso F, Reggiani F, Moroni G. Clinical and immunological biomarkers can identify proliferative changes and predict renal flares in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2025, 27, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassock, RJ. Prophylactic anticoagulation in nephrotic syndrome: a clinical conundrum. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, 2221–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponticelli C, Moroni G, Fornoni A. Lupus Membranous Nephropathy. Glomerular Dis. 2021, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii K, DKNK; et al. Role of thMembrane attack complex in murine lupus membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 1993, 43, 342–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ronco P, Plaisier E, Debiec H. Advances in membranous nephropathy. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Sandor DG, Beck LH. The role of complement in membranous nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 2013, 33, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song D, Guo W-Y, Wang F-M, et al. Complement Alternative Pathway׳s Activation in Patients With Lupus Nephritis. Am J Med Sci 2017, 353, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz AR, Tesar V. Lupus nephritis and ANCA-associated vasculitis: Towards precision medicine? Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2021, 36 (Suppl. S2), II37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano S, Milone A, Nicoletti GF, Isenberg DA, Ciccia F. Precision medicine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava A, Buyon J, Magder L, et al. Urine proteomic signatures of histological class, activity, chronicity, and treatment response in lupus nephritis. JCI Insight.

- Gu Y, Xu H, Tang D. Mechanisms of Primary Membranous Nephropathy. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni G, Quaglini S, Radice A, et al. The Value of a Panel of Autoantibodies for Predicting the Activity of Lupus Nephritis at Time of Renal Biopsy. J Immunol Res 2015, 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fava A, Wagner CA, Guthridge CJ, et al. Association of Autoantibody Concentrations and Trajectories With Lupus Nephritis Histologic Features and Treatment Response. Arthritis Rheumatol 2024, 76, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia X, Li S, Wang Z, et al. Glomerular Exostosin-Positivity is Associated With Disease Activity and Outcomes in Patients With Membranous Lupus Nephritis. Kidney Int Rep 2024, 9, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran A, Casal Moura M, Fervenza FC, et al. In Patients with Membranous Lupus Nephritis, Exostosin-Positivity and Exostosin-Negativity Represent Two Different Phenotypes. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2021, 32, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Miranda MF, Sobrino-Vargas AM, Hernández-Andrade A, et al. Exostosin-1/exostosin-2 expression and favorable kidney outcomes in lupus nephritis: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Rheumatol 2024, 43, 2533–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Liu Y, Zhang M, et al. Glomerular Exostosin as a Subtype and Activity Marker of Class 5 Lupus Nephritis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2022, 17, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caza TN, Hassen SI, Kuperman M, et al. Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 is a novel autoantigen in membranous lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 2021, 100, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia X, Li S, Jia X, et al. Clinicopathological phenotype and outcomes of NCAM-1+ membranous lupus nephritis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2024, 40, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang ES, Ahn SM, Oh JS, et al. Long-term renal outcomes of patients with non-proliferative lupus nephritis. Korean Journal of Internal Medicine 2023, 38, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Vilet JM, Córdova-Sánchez BM, Uribe-Uribe NO, Correa-Rotter R. Immunosuppressive treatment for pure membranous lupus nephropathy in a Hispanic population. Clin Rheumatol 2016, 35, 2219–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpechi IG, Ayodele OE, Jones ESW, Duffield M, Swanepoel CR. Outcome of patients with membranous lupus nephritis in Cape Town South Africa. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012, 27, 3509–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun HO, Hu WX, Xie HL, et al. Long-term outcome of Chinese patients with membranous lupus nephropathy. Lupus 2008, 17, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastén V R, Massardo V L, Rosenberg G H, et al. Curso clínico de la nefropatía membranosa lúpica pura. Rev Med Chil.

- Farinha F, Barreira S, Couto M, et al. Risk of chronic kidney disease in 260 patients with lupus nephritis: analysis of a nationwide multicentre cohort with up to 35 years of follow-up. Rheumatology.

- Farinha F, Pepper RJ, Oliveira DG, McDonnell T, Isenberg DA, Rahman A. Outcomes of membranous and proliferative lupus nephritis – analysis of a single-centre cohort with more than 30 years of follow-up. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 3314–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson B V. , Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019, 78, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin BH, Ayoub IM, Chan TM, Liu Z-H, Mejía-Vilet JM, Floege J. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of LUPUS NEPHRITIS. Kidney Int 2024, 105, S1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammaritano LR, Askanase A, Bermas BL, et al. 2024 American College of Rheumatology ( ACR ) Guideline for the Screening, Treatment, and Management of Lupus Nephritis. 2025.

- Hahn BH, McMahon MA, Wilkinson A, et al. American College of Rheumatology guidelines for screening, treatment, and management of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan J, Moutzouris D-A, Ginzler EM, Solomons N, Siempos II, Appel GB. Mycophenolate mofetil and intravenous cyclophosphamide are similar as induction therapy for class V lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 2010, 77, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YAP DY, YU X, CHEN X, et al. Pilot 24 month study to compare mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus in the treatment of membranous lupus nephritis with nephrotic syndrome. Nephrology 2012, 17, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarot N, Verhelst D, Pardon A, et al. Rituximab alone as induction therapy for membranous lupus nephritis. Medicine 2017, 96, e7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Zhang H, Liu Z, et al. Multitarget Therapy for Induction Treatment of Lupus Nephritis. Ann Intern Med 2015, 162, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin BH, Teng YKO, Ginzler EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of voclosporin versus placebo for lupus nephritis (AURORA 1): a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2070–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, et al. Two-Year, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Belimumab in Lupus Nephritis. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovin BH, Furie R, Teng YKO, et al. A secondary analysis of the Belimumab International Study in Lupus Nephritis trial examined effects of belimumab on kidney outcomes and preservation of kidney function in patients with lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 2022, 101, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furie RA, Rovin BH, Garg JP, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Obinutuzumab in Active Lupus Nephritis. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2025, Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3992.

| Class | Name | Definition | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Minimal mesangial lupus nephritis | Normal by LM with mesangial deposits by IF or EM | May have other features such as podocytopathy or tubulointerstitial disease (beware of unsampled class III). |

| II | Mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis | Purely mesangial hypercellularity by LM with mesangial deposits by IF; may be rare subepithelial or subendothelial deposits by IF or EM (not by LM). | May have other features such as podocytopathy, tubulointerstitial disease (beware of unsampled class III), or thrombotic microangiopathy. |

| III | Focal lupus nephritis | Active or inactive segmental or global endocapillary and/or extracapillary glomerulonephritis by LM in < 50% of glomeruli; usually with subendothelial deposits. | Active (A) & chronic (C) lesions defined in Modified NIH Activity & Chronicity Scoring System; replaces A & C designation. |

| IV | Diffuse lupus nephritis | Active or inactive endocapillary and/or extracapillary glomerulonephritis by LM in ≥ 50% of glomeruli. | Omitted segmental (S) & global (G) designations due to lack of reproducibility & clinical correlation; A & C lesions as defined in Modified NIH Activity & Chronicity Scoring System. |

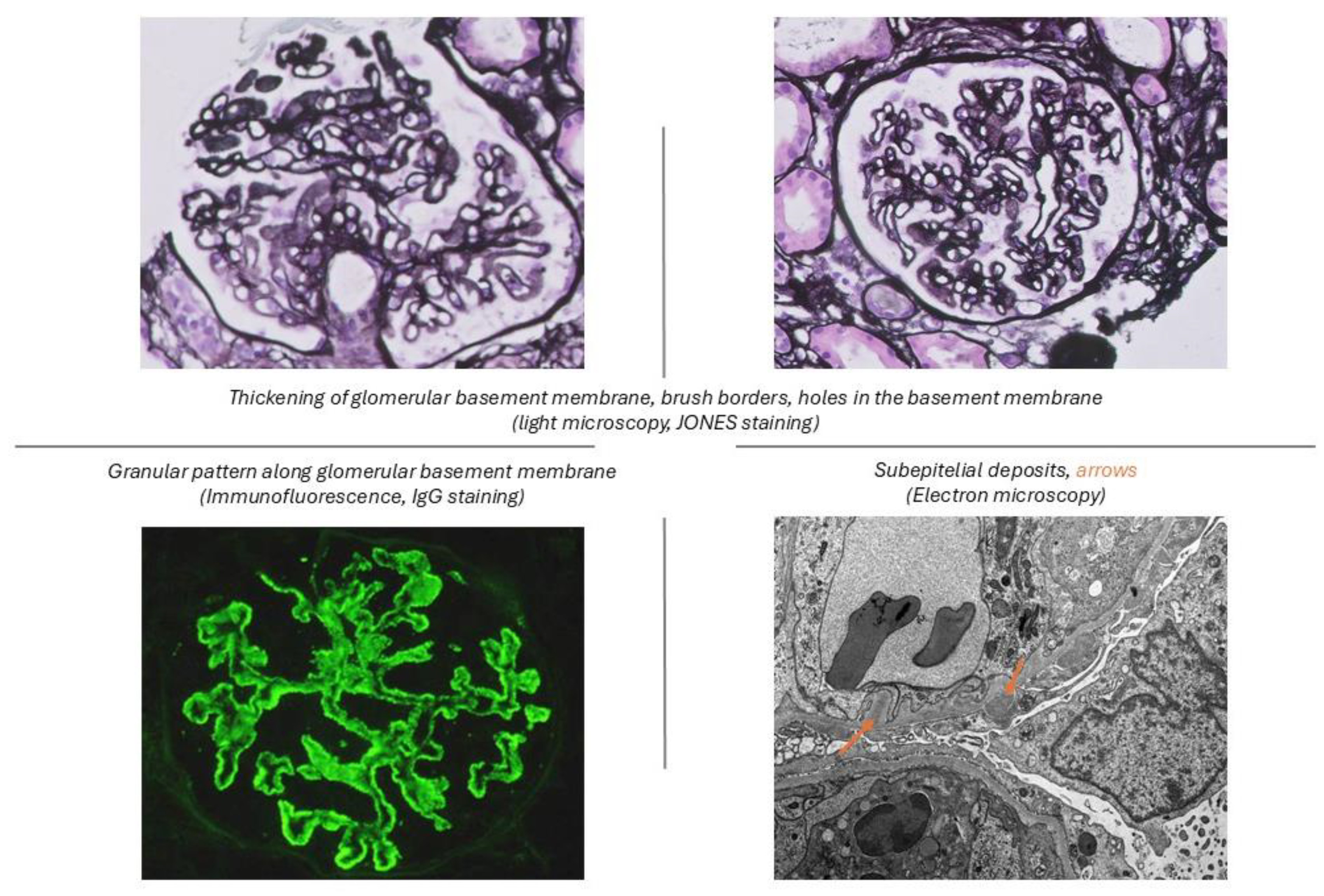

| V | Membranous lupus nephritis | Global or segmental granular subepithelial deposits along GBM by LM & IF or EM; if class III or IV is present, needs to be in > 50% of capillaries or > 50% of glomeruli; ± mesangial alterations. | May occur with class III or IV, which are designated class III/V or class IV/V, respectively. |

| (VI) | Advanced sclerosing lupus nephritis | ≥ 90% of glomerular sclerosis without residual activity. | Should be eliminated or reevaluated due to the recognizability of globally sclerotic glomeruli resulting from preceding lupus nephritis active lesions versus nonspecific global sclerosis associated with other factors (i.e., aging, hypertension, or healed TMA lesions). |

| NIH Activity Index | Definition | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Endocapillary hypercellularity (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 |

| Neutrophils/karyorrhexis (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 × 2 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 × 2 |

| Wire loops or hyaline thrombi (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 |

| Cellular or fibrocellular crescents (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 × 2 |

| Interstitial inflammation (% cortex) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of cortex | 0–3 |

| Total (Activity Index): | 0–24 | |

| NIH Chronicity Index | Definition | Score |

| Glomerulosclerosis score, global and/or segmental (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 |

| Fibrous crescents (% glomeruli) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of glomeruli | 0–3 |

| Tubular atrophy (% cortex) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of cortex | 0–3 |

| Interstitial fibrosis (% cortex) | None (0), < 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), > 50% (3+) of cortex | 0–3 |

| Total (Chronicity Index): | 0–12 |

| N° |

Kidney biopsy histology | Race | Year | Follow-up (yr) | Main Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kang et al. [53] |

50 | Classes V/II+V* (non-proliferative) |

Asian | 2022 | 8.6 | At last follow-up: 29% had eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Low eGFR levels at 6 months were associated with poor renal outcomes. |

|

Silva-Fernandez et al. [31] |

150 | Pure class V* | Caucasian | 2017 | 7.6 | 20% impaired eGFR at diagnosis. At last observation: 5% kidney failure, 6% death. |

|

Mejia et al. [54] |

60 | Pure Class V* | Caucasian | 2016 | 4.3 | 38.3% impaired eGFR at diagnosis; at last observation: 3.3% kidney failure, 5% death. |

|

Okpechi et al. [55] |

42 | Pure Class V* | African-American | 2012 | NA | 26.2% of patients reached the composite endpoint (death, end-stage renal failure, or persistent doubling of serum creatinine). |

|

Sun et al. [56] |

100 | Pure Class V* | Asian | 2008 | 6.4 | 29.9% relapses, 21 patients re-biopsied after 33 months: 8 (38.1%) transformed (class V + class IV in 5, class V + III in 2, and class VI in 1). Patient survival at 5 and 10 years: 98%. Renal survival at 5 and 10 years: 96.1% and 92.7% |

|

Pasten et al. [57] |

33 | Va/Vb° | Caucasian | 2005 | 5.3 | At last observation: 33% death, 25%, CrCl <15ml/min at 5 years |

|

Mok et al. [32] |

38 | Va/Vb° | Asian | 2004 | 7.5 | 67% complete remission, 19% renal flares, 13% had a decline of Cr/Cl by 20%. |

|

Mercadal et al. [19] |

66 | Va/Vb° | 48% Caucasian, 47% African-American | 2002 | 6.9 | 49% relapses; renal survival at 5- ad at 10 years 97%, and 88%; kidney failure 9% . |

| N° | Comparison | Pure membranous | Mixed classes | Pure proliferative | Race | Year | Follow-up (yr) | Main Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kharouf et al. [22] |

215 | Class V vs Classes III or IV vs classes VII+V/IV + V* |

51 | 44 | 120 | Australian | 2024 | 8 | No differences in complete renal response, proteinuria recovery. PLN vs pMLN/mixed LN : trend towards worse long-term outcomes |

|

Farinha et al. [58] |

260 | Class V vs Classes III or IV* | 47 | (10^) | 203 | Caucasian | 2024 | 8 |

pMLN: lower creatinine at onset PLN: low C3-C4, higher anti-DNA positivity. At last observation: CKD:17% PLN vs 7% pMLN; ESKD 4% vs 2%, Deaths 7% vs 2% |

|

Moroni et al. [21] |

103 | Class V vs Classes III+V/IV + V* | 67 | 36 | NA | Caucasian | 2012 | 13 |

Mixed classes: more frequent nephrotic syndrome at onset, low C3-C4, anti-DNA positivity, higher activity-chronicity indexes. No differences in remission (94.5 vs 94.0%) and kidney survival (85.8 vs 86.0%) at 10 years between groups |

|

Sloan et al. [18] |

79 | WHO Va/Vb vs Vc/Vd° | 36 | 43 | NA | American | 1996 | 4 |

Va/Vb better prognosis than Vc/Vd: 10-y renal survival 72% Va/Vb vs 20-49% Vc/Vd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).