Submitted:

30 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

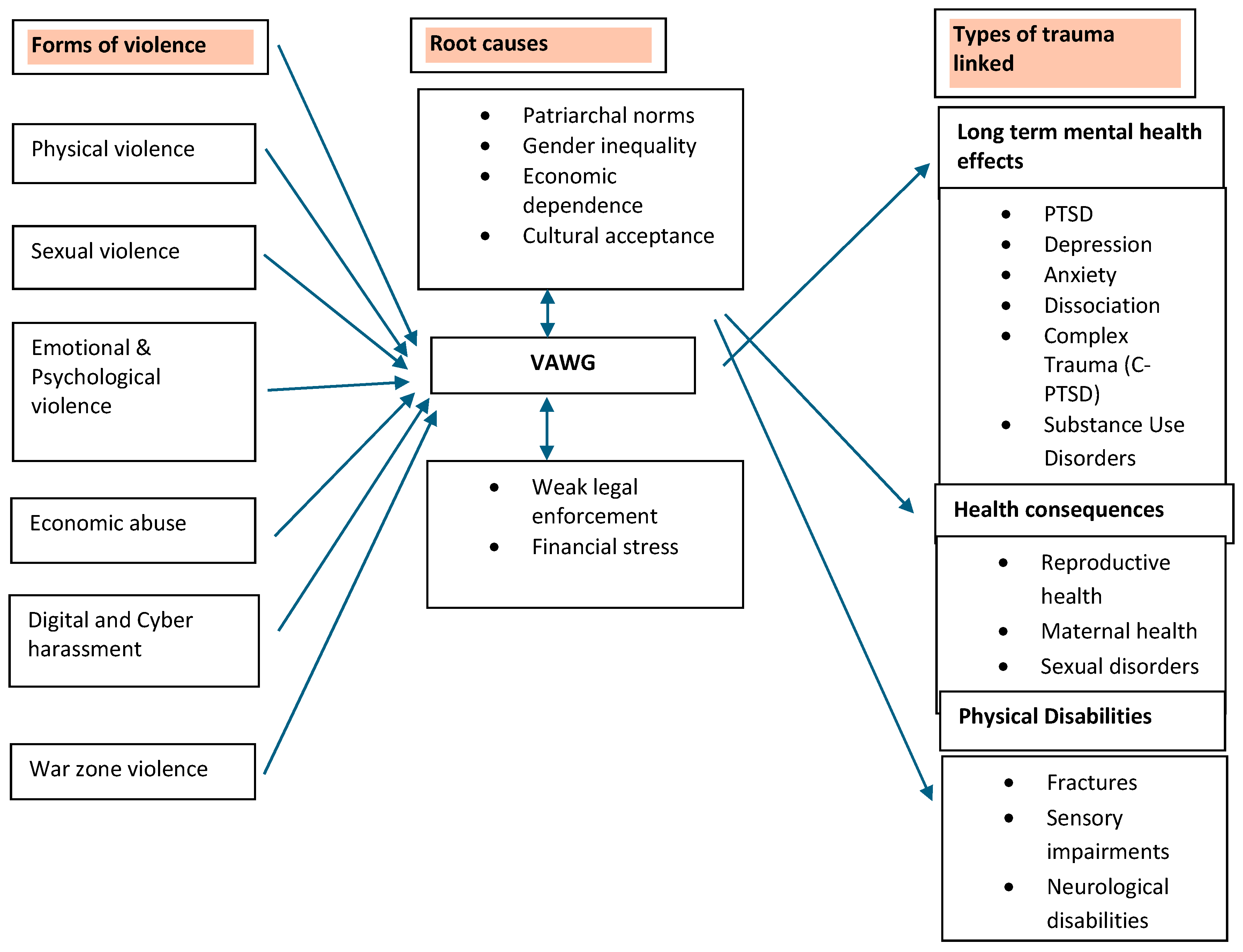

Background

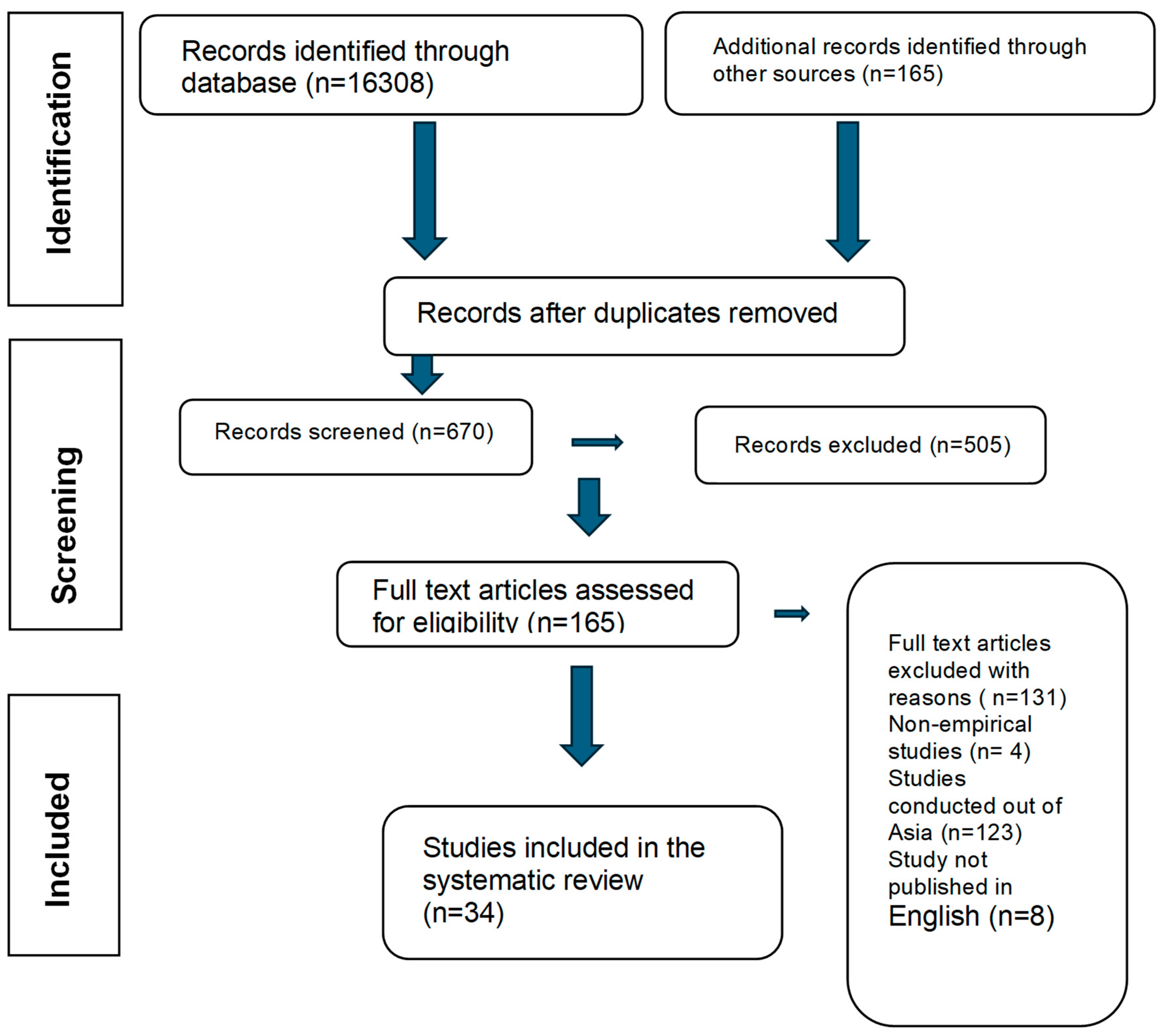

Methods

Study Design

Aims

Eligibility Criteria

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction

Data Analysis

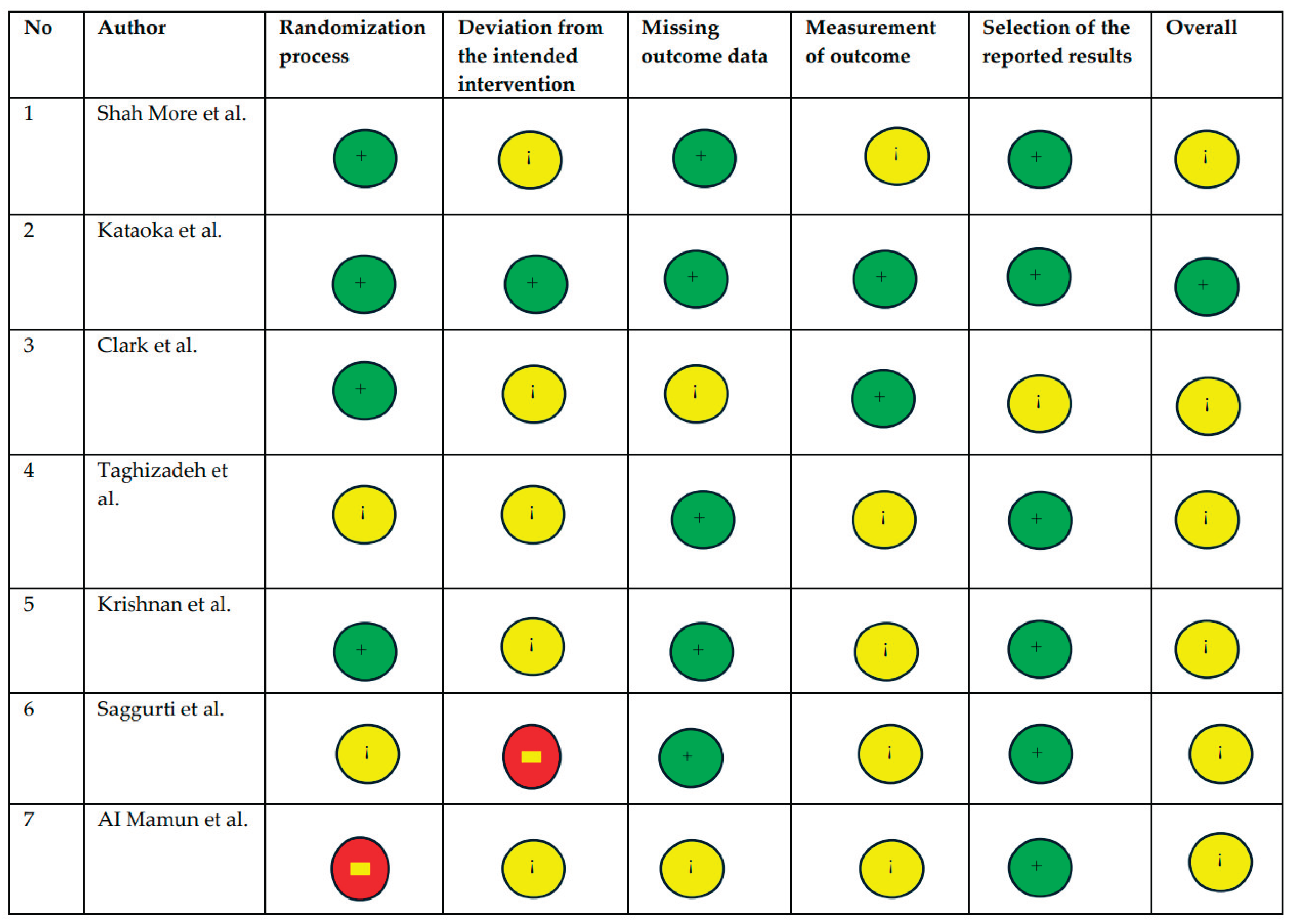

Risk of Bias Assessment

-

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied to observational studies (cohort and case-control designs). Studies were rated based on selection, comparability, and outcome/exposure domains. Studies were classified as:

- ○

- Low risk: 7–9 stars;

- ○

- Moderate risk: 5–6 stars;

- ○

- High risk: 0–4 stars.

- The Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (ROB-2) tool was used for randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Risk was assessed across five domains including randomisation, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting.

Results

Study Selection

Study Characteristics

Legal and Institutional Gaps

Health Impacts and Intergenerational Effects

Intervention Evidence and Prevention Strategies

Contextual Variations and Emerging Forms of Violence

Thematic Analysis

Socio-Cultural Determinants

Economic Determinants

Legal and Institutional Determinants

Regional and Demographic Variations

Emerging Forms of Violence

Interplay Between Determinants of Violence Against Women and Girls

Sub-group Analysis

Psychological Intimate Partner Violence

Physical Intimate Partner Violence

Sexual Intimate Partner Violence

Economic Coercion

Socio-Cultural Factors

Legal and Institutional Factors

Demographic Variations

Emerging Forms of Intimate Partner Violence

Risk of Bias

Discussion

Socio-Cultural Determinants: Entrenched Patriarchy and Harmful Norms

Economic Dependency: Structural Poverty as an Enabler of Violence

Legal and Institutional Gaps: Protection Without Enforcement

Demographic and Regional Variations: Intersectionality of Risk

Strengths and Limitations

Implications for Policy and Practice

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

Code Availability

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gautam, S.; Jeong, H.S. Intimate Partner Violence in Relation to Husband Characteristics and Women Empowerment: Evidence from Nepal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerson, L.K.; Kawachi, I.; Barbeau, E.M.; Subramanian, S.V. Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: A population-based study of women in India. Am J Public Health 2008, 98, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, R.; Tamang, J. Sexual coercion of married women in Nepal. BMC Womens Health 2010, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhungel, S.; Dhungel, P.; Dhital, S.R.; Stock, C. Is economic dependence on the husband a risk factor for intimate partner violence against female factory workers in Nepal? BMC Womens Health 2017, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, P.S.; Satyanarayana, V.A.; Carey, M.P. Women reporting intimate partner violence in India: Associations with PTSD and depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009, 12, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuba, K.; Mainali, A.; Alvesson, H.M.; Karki, D.K. Experience of intimate partner violence among young pregnant women in urban slums of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2016, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongrum R, Thomas E, Lionel J, Jacob KS. Domestic violence as a risk factor for maternal depression and neonatal outcomes: A hospital-based cohort study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014, 36, 179–181. [CrossRef]

- AU - Silwal A, AU - Thapa B, 2020/06/30 P-, 2025/08/17 Y-, Article S-O, 10.31729/jnma.4886 D-; et al. Prevalence of Domestic Violence among Infertile Women attending Subfertility Clinic of a Tertiary Hospital. J Nepal Med Assoc. 58(226).

- Sheikhan, Z.; Ozgoli, G.; Azar, M.; Alavimajd, H. Domestic violence in Iranian infertile women. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran (MJIRI) 2014, 28, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, T.; Lu, L.; Xing, Z.W. The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries. Cmaj 2011, 183, 1374–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygül Akyüz GŞ, Memnun Seven, Bilal Bakır. The Effect of Marital Violence on Infertility Distress among A Sample of Turkish Women. International Journal of Fertility and Sterility. 2014, 8.

- Ardabily HE, Moghadam ZB, Salsali M, Ramezanzadeh F, Nedjat S. Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011, 112, 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Yount KM, Krause KH, VanderEnde KE. Economic Coercion and Partner Violence Against Wives in Vietnam: A Unified Framework? J Interpers Violence. 2016, 31, 3307–3331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs A, Corboz J, Jewkes R. Factors associated with recent intimate partner violence experience amongst currently married women in Afghanistan and health impacts of IPV: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 593.

- Bondade S, Iyengar RS, Shivakumar BK, Karthik KN. Intimate Partner Violence and Psychiatric Comorbidity in Infertile Women - A Cross-Sectional Hospital Based Study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018, 40, 540–546. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourey C, Stephenson R, Hindin MJ. Reproduction, functional autonomy and changing experiences of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2013, 39, 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Satheesan SC, Satyaranayana VA. Quality of marital relationship, partner violence, psychological distress, and resilience in women with primary infertility. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health. 2018, 5(2).

- Coskuner Potur D, Onat G, Dogan Merih Y. An evaluation of the relationship between violence exposure status and personality characteristics among infertile women. Health Care Women Int. 2019, 40, 1135–1148. [CrossRef]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Acharya R, Barrick L, Ahmed S, Hindin M. Domestic violence and early childhood mortality in rural India: Evidence from prospective data. Int J Epidemiol. 2010, 39, 825–833. [CrossRef]

- Neena Shah More SD, Ujwala Bapat, Mahesh Rajguru, Glyn Alcock, Wasundhara Joshi, Shanti Pantvaidya and David Osrin. Community resource centres to improve the health of women and children in Mumbai slums: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Bio med central.

- Saggurti N, Nair S, Silverman JG, Naik DD, Battala M, Dasgupta A; et al. Impact of the RHANI Wives intervention on marital conflict and sexual coercion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014, 126, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- Clark CJ, Ferguson G, Shrestha B, Shrestha PN, Batayeh B, Bergenfeld I; et al. Mixed methods assessment of women’s risk of intimate partner violence in Nepal. BMC Womens Health. 2019, 19, 20.

- Kalokhe A, Del Rio C, Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Metheny N, Paranjape A, Sahay S. Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Glob Public Health. 2017, 12, 498–513. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh Z, Pourbakhtiar M, Ghasemzadeh S, Azimi K, Mehran A. The effect of training problem-solving skills for pregnant women experiencing intimate partner violence: A randomized control trial. Pan Afr Med J. 2018, 30, 79.

- Suneeta Krishnan KS, Prabha Chandra3 and Krishnamachari Srinivasan. Minimizing risks and monitoring safety of an antenatal care intervention to mitigate domestic violence among young Indian women: The Dil Mil trial. BMC Public health. 2012.

- DilekAkkuş ASM. Domestic Violence Against 116 Turkish Housewives: A Field Study. Women & Health. 2004, Vol. 40(3).

- Pun KD, Rishal P, Darj E, Infanti JJ, Shrestha S, Lukasse M; et al. Domestic violence and perinatal outcomes - a prospective cohort study from Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2019, 19, 671.

- Clark CJ, Spencer RA, Shrestha B, Ferguson G, Oakes JM, Gupta J. Evaluating a multicomponent social behaviour change communication strategy to reduce intimate partner violence among married couples: Study protocol for a cluster randomized trial in Nepal. BMC Public Health. 2017, 17, 75.

- Al Mamun M, Parvin K, Yu M, Wan J, Willan S, Gibbs A; et al. The HERrespect intervention to address violence against female garment workers in Bangladesh: Study protocol for a quasi-experimental trial. BMC Public Health. 2018, 18, 512.

- Leung TW, Leung WC, Ng EH, Ho PC. Quality of life of victims of intimate partner violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005, 90, 258–262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayda AS, Akkus D. Domestic violence against 116 Turkish housewives: A field study. Women Health. 2004, 40, 95–108.

- Sis Celik A, Kirca N. Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in a Turkish setting. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018, 231, 111–116. [CrossRef]

| Id | Author | Country | Study type | Methods | Setting | Population | Age | Sample size | Findings/ outcomes | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yount et al. | Vietnam | Population-based household | Survey | Community | Married women | 18-50 years | 533 | Determinants of economic coercion and common forms of IPV | Survey questionnaire |

| 2 | Silwal et al. | Nepal | Cross-sectional | Descriptive | Acute | Infertile women | 15-44 years | 112 | Women experiencing infertility are exposed to various forms of domestic violence | Standard tool used in Nepal demographic and health survey (NDHS),2016 |

| 3 | Z. Sheikhan, et al. | Iran | Cross- sectional | Descriptive | Fertility centre, (private) | Infertile women | Nr | 400 | Domestic violence and fertility | Researcher made questionnaire |

| 4 | Akyüz et al. | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Descriptive | In vitro fertilization (IVF) centre at military medical academy | Married women who applied to an in vitro fertilization | Nr | 139 | Marital violence is a factor increasing the distress of infertile women. | A descriptive questionnaire developed by the researcher |

| 5 | Bondade et al. | India | Cross-sectional | Descriptive | Oxford medical college hospital And research centre, Bangalore |

Women with primary infertility | 18 -45 years | 100 | A significant number of women who had infertility reported IPV. Women with IPV had higher psychiatric comorbidity and may require psychotherapeutic intervention. |

Psychiatric diagnosis-dsm-5. Hamilton anxiety rating scale (ham-a) and Hamilton depression rating scale (ham-d) IPV -who violence against women instrument. |

| 6 | Leung et al. | China | Case-control | Quantitative | Queen Mary Hospital | Patients seeking medical help from the department Of obstetrics and gynaecology |

Nr | 1614 |

Prevalence of intimate partner violence The quality of life of abused women. |

Structured questionnaire modified from the abuse assessment screen questionnaire |

| 7 | Pun et al. | Nepal | Prospective cohort study | Quantitative | Two hospitals in Nepal | Pregnant women | 1381 | Violence is a potential risk factor for severe morbidity and mortality in newborns. | The abuse assessment screen (modified) | |

| 8 | Satheesan SC et al. | India | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Infertility hospital in Bangalore | Adult women | 18+ years | 30 | High rates of intimate partner violence (47%) Poorer quality of marital relationship was associated with higher levels of psychological distress and lower resilience |

Marital quality scale, domestic violence Questionnaire, depression anxiety stress scale-21, and Connor Davidson resilience scale |

| 9 | Gibbs et al. | Afghanistan | Cross-sectional | Descriptive | Villages | Married women | 18 -49 years | 935 | Importance of economic empowerment interventions to reduce women’s experiences of IPV | Structured paper and pencil questionnaires |

| 10 | Al Mamun et al. | Bangladesh | Quasi-experimental | Quantitative | Factories | Garment workers | Nr | 800 | Evaluate the impact on IPV and WPV | |

| 11 | Kataoka et al. | Japan | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Prenatal clinic | Pregnant women | 328 | Self-administered questionnaire versus interview as a screening method for intimate partner violence | Self-administered questionnaire and interviews | |

| 12 | Clark et al. | Nepal | Randomised control trial | Mixed methods | Community | Female participants | Nr | 1440 individuals | The effectiveness of a promising strategy to prevent IPV | Survey, focus group discussions, interviews |

| 13 | Taghizadeh et al., | Tehran | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Health centres of Tehran | Pregnant women | Nr | 142 | The effectiveness of training problem-solving skills on IPV against pregnant women | Conflict tactics scale questionnaire |

| 14 | Shah more et al. | India | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Urban slum areas | Women and children | Women-15 to 49 years Children undue age 5 |

600 households | The number of consultation for violence against women or children | Interviews |

| 15 | Krishnan et al. | India | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Primary health centres and community | Young pregnant women in 1st or 2nd trimesters | Nr | 144 | Incidence of domestic violence, the empowerment of daughter-in -law and mother -in -law | Interview |

| 16 | Bourey et al., | India | Prospective cohort | Quantitative | Rural areas | Married women | Nr | 4,749 | Economic contribution, pregnancy, and violence | Survey |

| 17 | D. Cos¸kuner potur et al., | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Descriptive | Acute | Infertile women | Nr | 315 | Infertility treatment duration and violence | An introductory information form, The Eysenck personality questionnaire revised-abbreviated Form (EPQR-a), and the infertile women’s exposure to Violence determination scale (IWEVDS) |

| 18 | Atilla s. Mayda and Dilek akkus | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Survey | Community | Housewives | Nr | 116 | Prevalence and forms of domestic violence (physical, emotional, sexual); demographic correlates | Survey |

| 19 |

H.E. Ardabil et al. | Iran | Cross sectional | Survey | Valais reproductive health research centre, Tehran university of medical science | Infertile women | Nr | 400 | Infertility and domestic violence | Revised conflict tactics scales questionnaire |

| 20 | Adhikari and Tamang | Nepal | Cross sectional | Survey | Community | Married women | 15-49 years | 1536 | About three in five women (58%) had experienced some form of sexual coercion by them Husbands. |

Structured questionnaire |

| 21 | Deuba et al. | Nepal | Qualitative | Interview | Urban slums | Young pregnant women | 15-24 years | 20 | Having a husband who has alcohol use Disorder, identification of foetal gender, and refusal to Have sex were fuelling factors that instigated IPV among Young pregnant women in urban slums |

in depth interviews |

| 22 | Nongrum et al. | India | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Urban | Women | Nr | 126 | High IPV; lack of services in ne region | Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, abuse assessment screen, maternal and neonatal outcome pro forma |

| 23 | Gautam and Jeong | Nepal | Cross sectional | Survey | Community and hospital setting | Men and women | 15–49 years | 12,862 women and 4063 men | Gender-based violence (or IPV) produces significant public health concerns resulting in physical, Sexual and reproductive, and psychological health problems and presents a violation of women’s Human rights. |

Nepal demographic And health survey (NDHS) 2016 |

| 24 | Saggurti et al. | India | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Low income community | Married women | 18–40 years | 220 | Community intervention reduced IPV significantly | Survey |

| 25 | Dhungel et al. | Nepal | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Factory | Working women | 15–49 years |

236 | Workplace harassment and economic coercion reported | A standardized, closed Ended questionnaire |

| 26 | Koenig et al. | India | Prospective cohort | Survey | Rural areas | Women | 15–49 years | 89199 | IPV prevalence tracked across regions and time |

Survey |

| 27 | A. Sis Celik, n. Kırca | Turkey | Cross sectional | IVF centre, community | Infertile women | 423 | High IPV rates among infertile women; stigma influences violence | Sociodemographic questionnaire” and “infertile women’s expo- Sure to violence determination scale |

||

| 28 | Chandra et al. | India | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Adult psychiatry outpatient unit of National institute of mental health and neurosciences |

Women | 18 to 49 years | 105 | 56% of this sample of Indian women seeking help for common Mental health problems reported at least one form of intimate partner violence. |

Structured interview Severity of abuse was assessed by the index of spouse abuse (isa; Hudson and McIntosh Sexual coercion was assessed using the sexual experiences scale (ses; Koss and Oros Depression was assessed using the beck depression inventory Post-traumatic symptom checklist |

| 29 | Ackerson et al. | India | Cross sectional | Descriptive | Community | Ever-married women | 15 To 49 years |

83627 |

Reporting IPV is high when women educational level is higher. | Survey |

| 30 | Ackerson and Subramanian | India | Cross sectional | Rural areas | Ever-married women | 15 To 49 years |

69,072 |

Domestic violence and malnutrition indicators | Survey | |

| 31 | Choudhary et al. | Nepal | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Urban and rural areas | Women | Nr | 3708 | Sub-optimal water access and the probability of IPV against Women. |

Interview |

| 32 | Bhatta, Assanangkornchai, & Rajbhandari, 2021 | Nepal | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Women in pregnancy | 15 To 49 years |

660 | DV is significantly associated with husband’s alcohol consumption, controlling behaviour | Validated questionnaire |

| 33 | Akar et al. | Turkey | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Primary care health centres affiliated with Gazi university, Ankara | Married women | Nr | 1178 | Lifetime IPV prevalence: 77.9% | Structure questionnaire |

| 34 | Bloom et al. | Eswatini | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women | Nr | 406 | Women who were food insecure or reported constrained agency (e.g., sex due to poverty, pressure) were at greater risk of reporting IPV. | Who violence against women Scale |

| Themes | Sub-themes | Study | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Intimate Partner Violence | Public humiliation | Yount et al. Choudhary et al. |

Between 9% and 15% of women reported lifetime exposure to specific forms of psychological IPV; 27% reported lifetime exposure to any psychological IPV. |

| Insult & Degradation | Satheesan et al. | Psychological IPV linked to lower marital quality and higher psychological distress in women facing infertility. | |

| Fear &Intimidation | Deuba et al. Pun et al. |

Alcohol use by husbands and sex refusal led to fear-inducing behaviour and violence against young pregnant women. Both violence and fear was significantly associated with giving birth to a preterm infant |

|

| Threat & Expulsion | Gautam & Jeong Atilla & Akkus Deuba et al. Satheesan et al. |

IPV produces long-term psychological, physical, and sexual health problems and violates women’s rights. | |

| Emotional abuse | Akyüz et al. Gibbs et al. T.W.Leung et al. |

Emotional abuse is prevalent, linked to depression and low marital satisfaction among Turkish women. Majority (61.5%) of the victims suffered from emotional or verbal abuse |

|

| Physical Intimate Partner Violence | Slap & strike | Yount et al. A. Sis Celik, N. Kırca Choudhary et al. |

29% reported lifetime exposure to any physical IPV. 30% expressed to be injured as a result of the violence |

| Shoving | Pun et al. Yount et al. |

IPV is a risk factor for poor maternal and neonatal health outcomes. | |

| Punching | Al Mamun et al. Choudhary et al. |

IPV prevalence remains high among garment workers, links to workplace stress and partner control | |

| Beating | Adhikari & Tamang Choudhary et al. H.E. Ardabily et al. |

58% of married women experienced sexual coercion; physical force commonly used to assert control. 8% of infertile women experienced injuries. |

|

| Chocking | Bondade et al. | Infertile women reported higher rates of physical IPV and associated psychiatric morbidity. | |

| Threatening | Gibbs et al. | Economic interventions are key to reducing IPV, which often includes physical threats. | |

| Sexual Intimate Partner Violence | Coerced sex | Adhikari & Tamang Saggurti et al. |

About 58% of women had experienced sexual coercion by their husbands. |

| Pregnancy-related abuse | Taghizadeh et al. | IPV against pregnant women decreased through problem-solving training, showing strong preventive potential. | |

| Economic Coercion | Financial control/ dependency | Yount et al. Bondade et al. Pun et al. Clark et al. Bourey et al., Deuba et al. |

3%–21% of women reported economic coercion such as being denied financial autonomy. Infertile women reported higher IPV and psychiatric morbidity due to dependency. IPV is a risk factor for poor maternal and neonatal outcomes, particularly in low-income settings. Economic interventions and empowerment programs effectively reduce IPV. Changes in financial autonomy and freedom of movement were reported by 38% and 44% of the women. |

| Dowry-related abuse | Shah More et al. Bourey et al. |

Consultations for IPV often related to dowry demands; economic expectations used to justify abuse. | |

| Employment restrictions | Dhungel et al. Al Mamun et al. Krishnan et al. Shah More et al. |

Working women in factories experienced harassment and economic coercion tied to gender roles. Workplace IPV is linked to economic vulnerability among garment workers. Empowerment of women (and mothers-in-law) can reduce IPV during pregnancy. Consultations for IPV were tied to economic factors like dowry demands. |

|

| Socio-Cultural Factors | Patriarchy & gender norms | Sheikhan et al. Silwal et al. Adhikari & Tamang |

Cultural beliefs reinforcing male dominance and stigma toward infertile women sustain IPV. 58% of married women experienced sexual coercion; physical force used to assert control. |

| Victim blaming | Leung et al. | Women reporting IPV had reduced quality of life and often faced judgment from health professionals. | |

| Religious influences | Deuba et al. | Alcohol use and sex refusal fuelled IPV; influenced by cultural and possibly religious values. | |

| Gendered family roles | Yount et al. Sheikhan et al. Satheesan et al. Gautam & Jeong Atilla & Akkus |

Lifetime exposure to psychological and physical IPV often stems from traditional roles. Infertility and IPV linked to poor marital quality and increased psychological distress. IPV leads to physical, sexual, and reproductive health issues, and violates human rights. Elder housewives face emotional control and neglect due to traditional expectations. |

|

| Legal & Institutional Factors | Weak justice systems | Clark et al. Saggurti et al. |

Legal reforms and community-based strategies can effectively reduce IPV incidence. RCT shows interventions can reduce IPV through structured community engagement. |

| Limited support services | Deuba et al. | Lack of counselling and police responsiveness discourages IPV reporting. | |

| Access to justice | Deuba et al. Nongrum et al. |

IPV is underreported due to stigma and lack of police responsiveness. Women in conflict-affected or remote areas struggle to access protection. |

|

| Institutional responsiveness | Taghizadeh et al. Kataoka et al. Shah More et al. |

Training in problem-solving skills effectively reduced IPV during pregnancy. IPV screening improved with self-administered questionnaires in clinical settings. IPV related to dowry and cyber harassment indicates gaps in institutional response. |

|

| Demographic Variations | Rural vs urban disparity | Bourey et al. Nongrum et al. | Rural women face normalized abuse due to tradition, while urban women are more exposed to cyber-harassment. |

| Conflict zones | Gibbs et al. | High IPV rates among displaced women; compounded by lack of institutional protection. | |

| Emerging Forms of Intimate partner Violence | Cyber violence | Shah More et al. | Digital harassment is increasingly reported among young and unmarried women in urban slums |

| Workplace violence | Al Mamun et al. | Workplace IPV is linked with economic vulnerability and informal labour settings | |

| Elder neglect | Atilla & Akkus | Elder housewives in patriarchal settings experience neglect and emotional control. |

| No | Authors | Selection (S) | Comparability (C) | Exposure / Outcome (E/O) | Total stars | Conclusion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| 1 | Silwal et al.,2020 | * | * | ** | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 2 | Z.Sheikhan, et al.,2014 | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 3 | Akyüz et al. | * | * | ** | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 4 | Bondade et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | ******** | Low risk | |

| 5 | T.W.Leung et al. | * | * | * | * | * | ***** | Moderate risk | |||

| 6 | Pun et al. | * | * | * | * | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | ||

| 7 | Satheesan SC et al. | * | * | * | * | * | ***** | Moderate risk | |||

| 8 | Gibbs et al. | * | * | * | * | * | ***** | Moderate risk | |||

| 9 | Bourey et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 10 | D. Cos ̧Kuner Potur et al. | * | * | ** | **** | High risk | |||||

| 11 | Koenig et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | ******** | Low risk | |

| 12 | Yount et al. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ******* | Low risk | |

| 13 | H.E. Ardabily et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 14 | Chandra et al.,2009 | * | * | * | * | * | ***** | Moderate risk | |||

| 15 | Ackerson et al.,2008 | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 16 | Ackerson and Subramanian | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Moderate risk | |||

| 17 | Atilla S. Mayda and Dilek Akkus | * | * | * | High risk | ||||||

| 18 | Gautam and Jeong | * | * | * | ** | * | ****** | Low risk | |||

| 19 | Choudhary et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | * | ******* | Low risk | ||

| 20 | A. Sis Celik, N. Kırca | * | * | * | * | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | ||

| 21 | Dhungel et al. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ******* | Low risk | |

| 22 | Clark et al., 2019 | * | * | * | * | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | ||

| 23 | Akar et al. (2010) | * | * | * | * | * | * | ****** | Moderate risk | ||

| 24 | Bhatta, Assanangkornchai, & Rajbhandari, 2021 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | ******* | Low risk | ||

| 25 | Bloom et al. | * | * | * | ** | * | * | ******* | Low risk | ||

| 26 | Nogrum et al. | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | ********* | Low risk |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).