Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Traditional satellite ocean color algorithms for chlorophyll-a and inherent optical property retrieval rely on deterministic regression models that typically produce single-point predictions without explicit uncertainty quantification. The absence of uncertainty awareness undermines in-situ/model match-ups, reduces predictive reliability, and ultimately erodes user confidence. In the present study, I address this limitation by demonstrating how to implement a complete Bayesian workflow applied to the foundational chlorophyll-a retrieval problem. To that end, I use a set of well-established Bayesian modeling tools and techniques to train and evaluate probabilistic models that approximate the underlying data-generating process and yield posterior distributions conditioned on both data and model structure. The posterior distribution is an information-rich construct that can be mined for diverse insights. I develop and compare models of increasing complexity, beginning with a baseline polynomial regression and culminating in a hierarchical partial pooling model with heteroscedasticity. Similar to classical machine learning, model complexity in a Bayesian setting must also be scrutinized for its potential to overfit. This is addressed through efficient cross-validation and uncertainty calibration that exploit the full posterior distribution. Within this framework, the most complex model performed best in terms of out-of-sample uncertainty calibration and generalizability. Persistent localized mismatches across models point to domains where predictive power remains limited. Taken together, these results show how placing uncertainty at the center of inference allows a Bayesian approach to produce transparent, interpretable, and reliable chlorophyll- a retrievals from satellite ocean color data, paving the way for the development of more robust marine ecosystem monitoring products.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Limitations of Existing Approaches

1.3. Overcoming Limitations

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset, Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

2.2. Modeling Approach

2.2.1. Model Progression

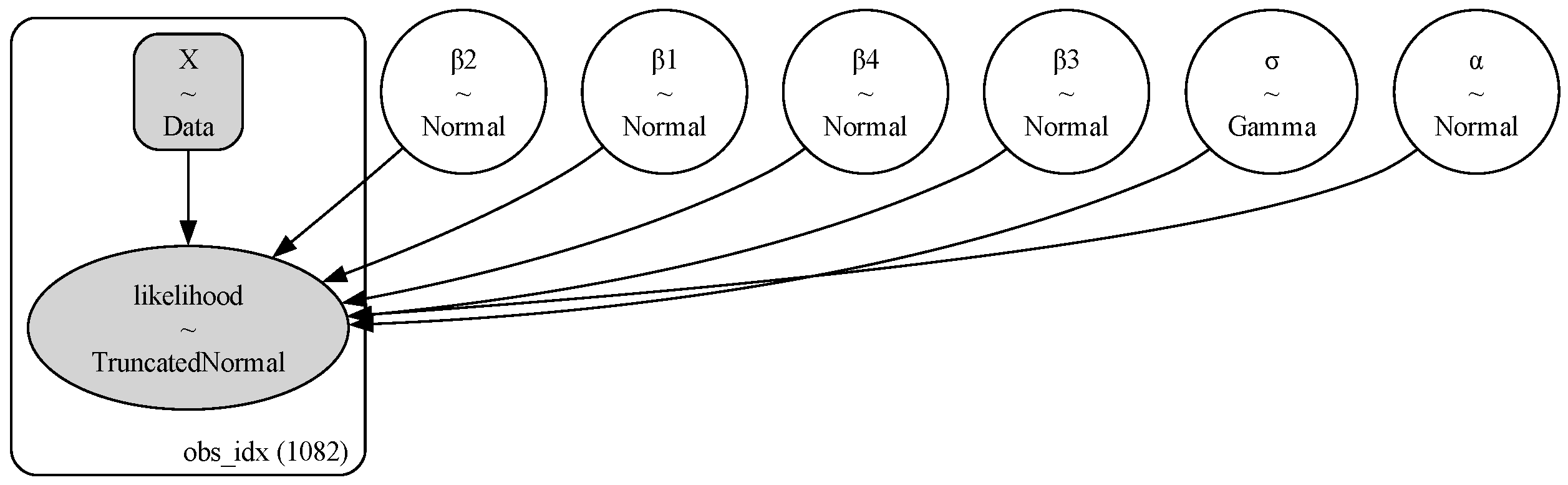

2.2.2. Model Structures and Priors

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance Overview

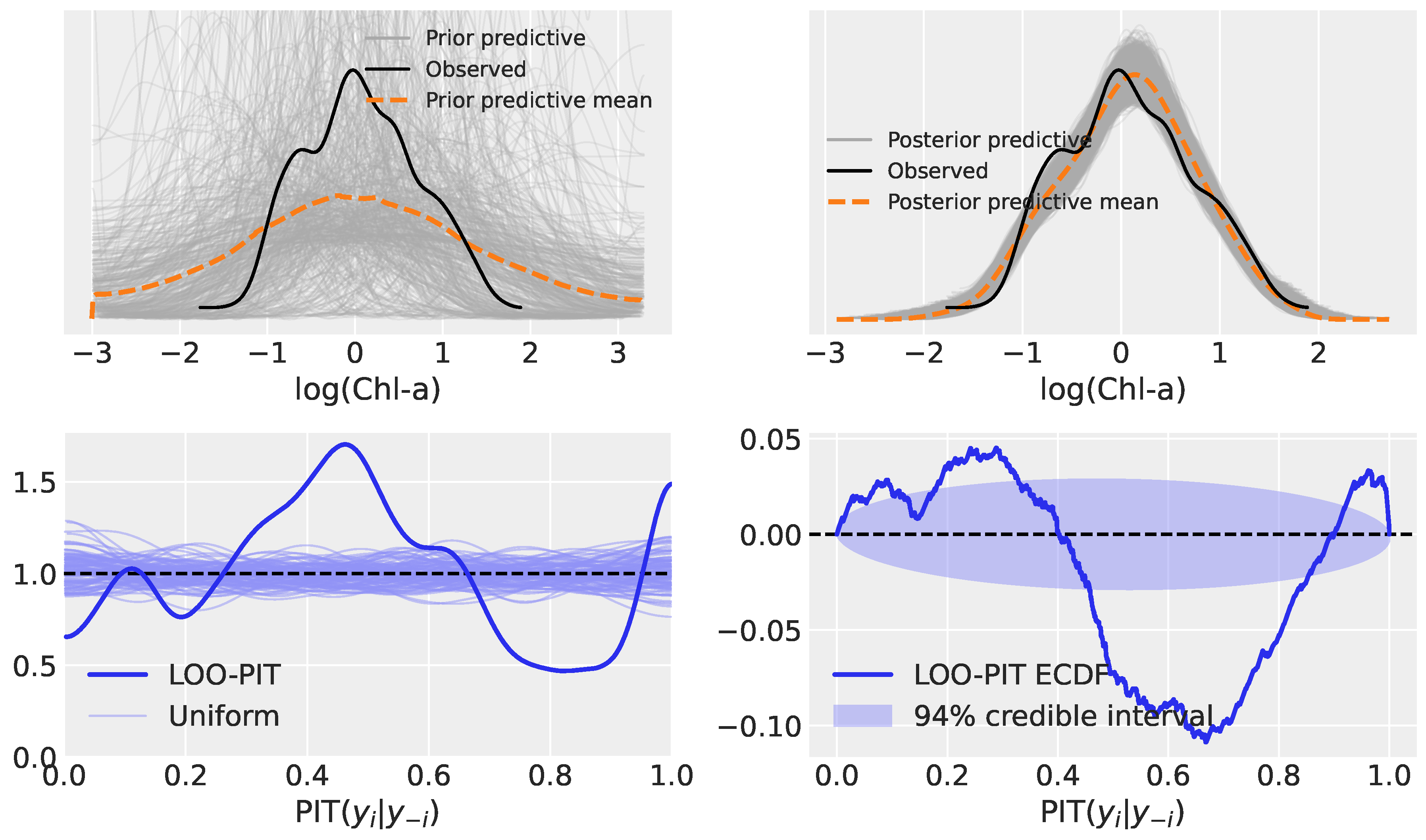

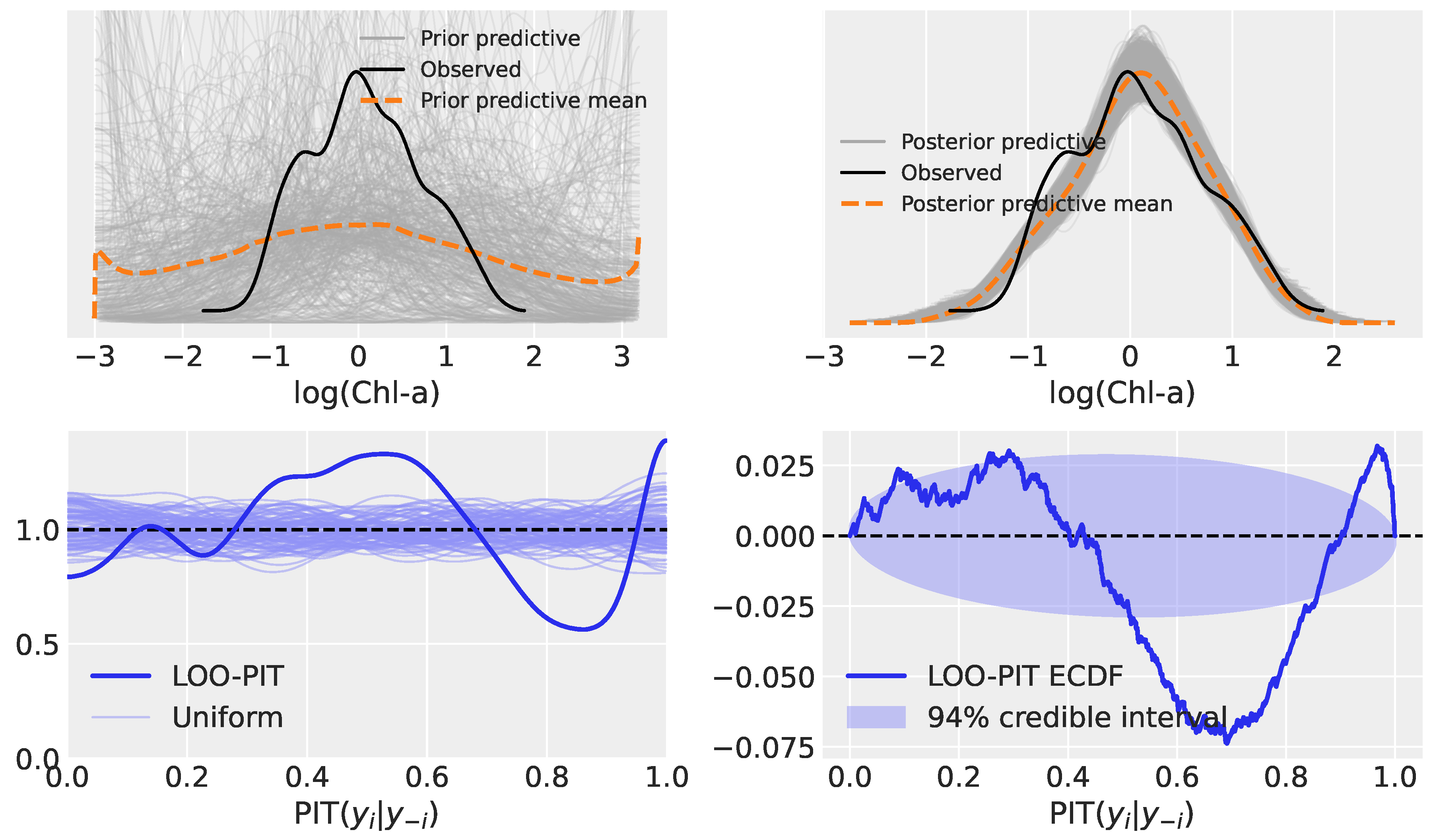

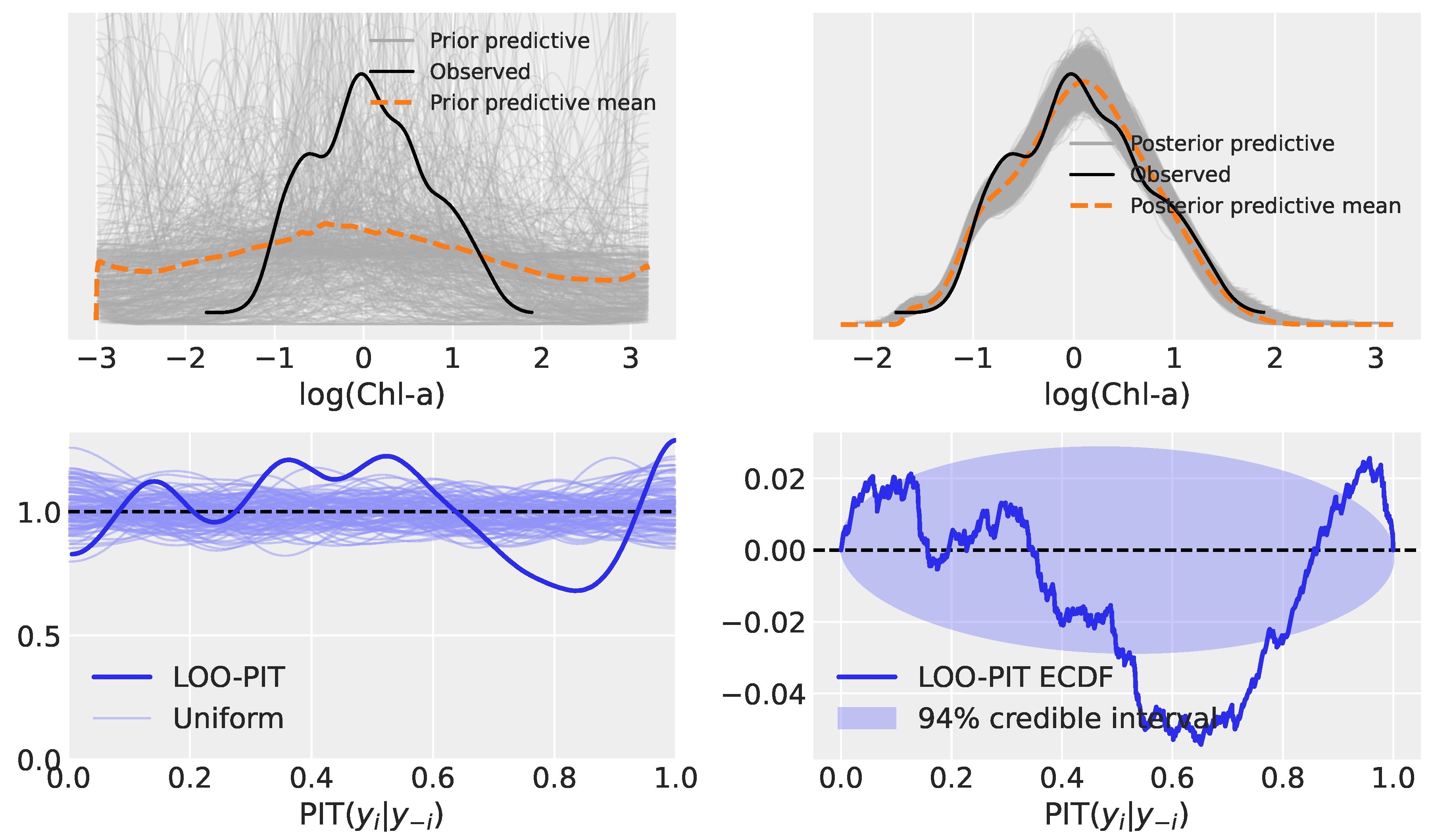

3.2. Model Evaluation: Prior Predictive, Posterior Predictive, and LOO-PIT

3.2.1. Model 1: Polynomial Regression

3.2.2. Model 2: Hierarchical Linear Regression

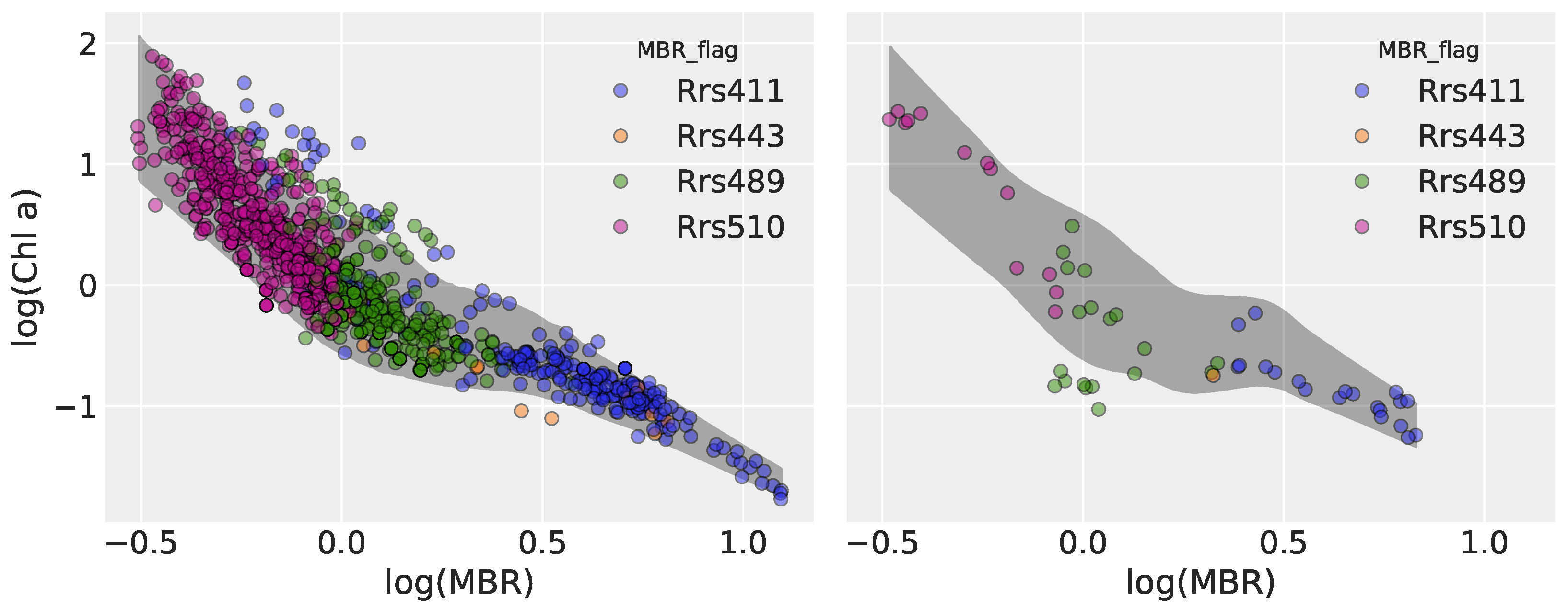

3.2.3. Model 5: Heteroscedastic Hierarchical Linear Regression

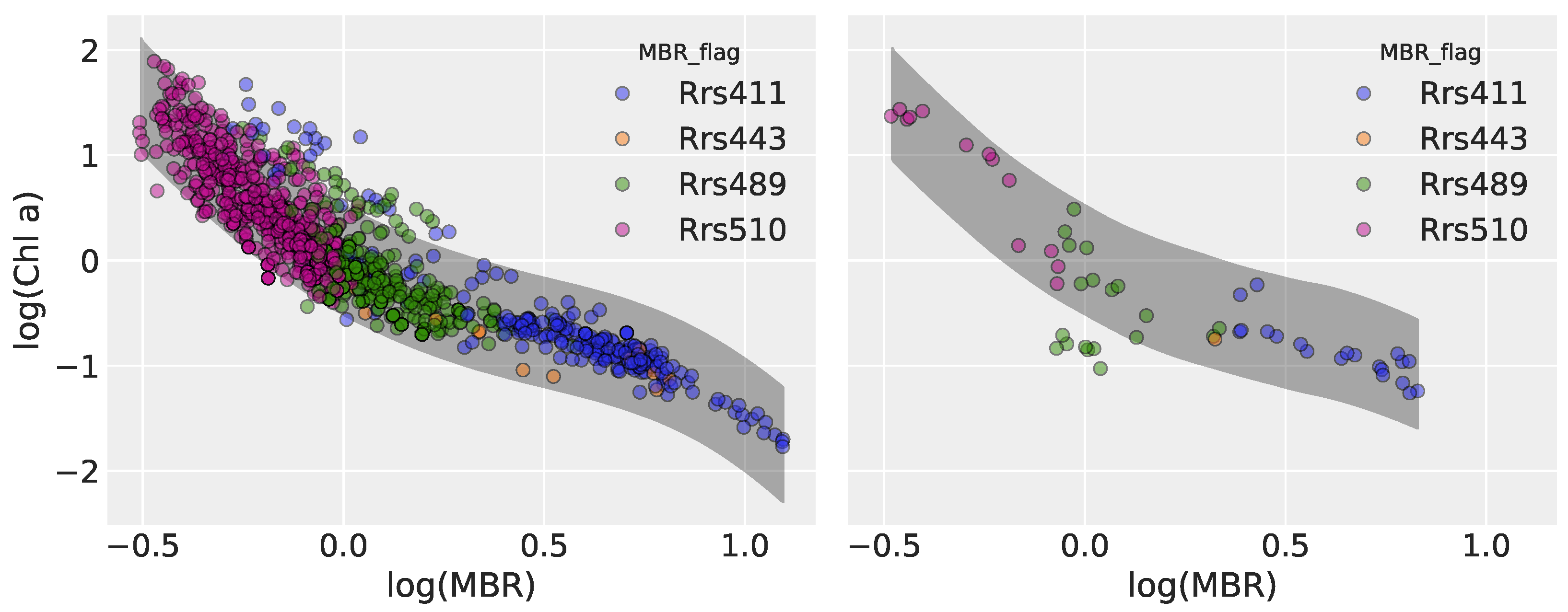

3.3. Predictive Coverage

3.3.1. Model 1

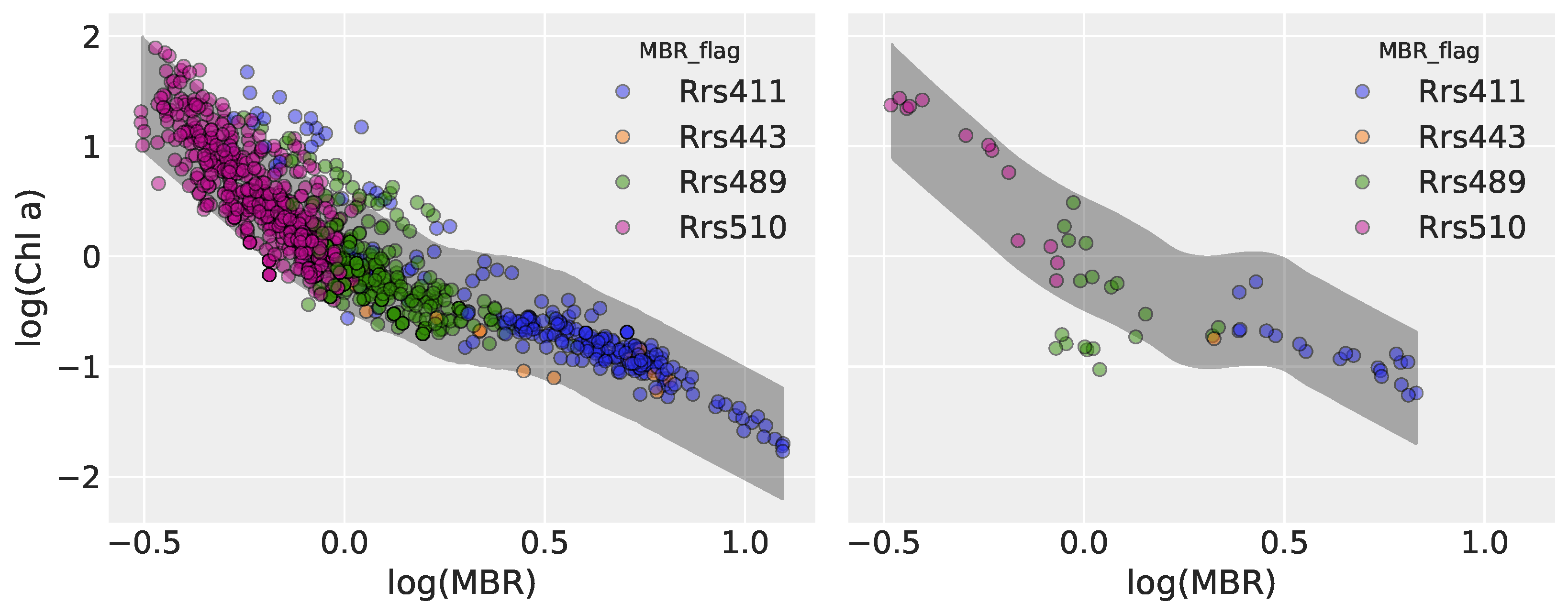

3.3.2. Model 2

3.3.3. Model 5

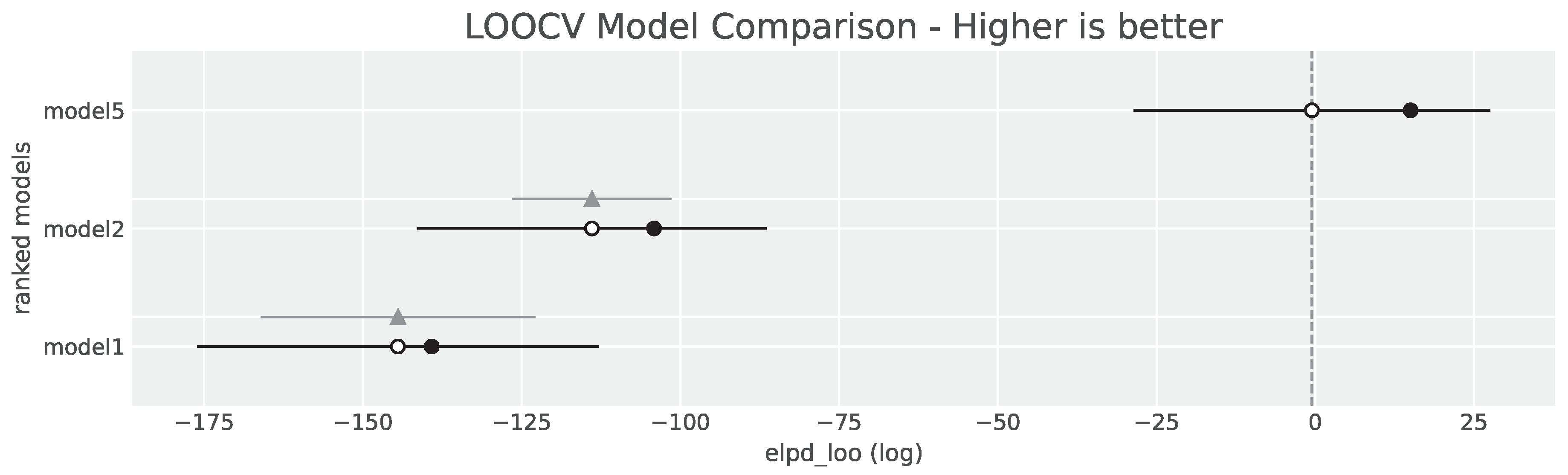

3.4. Model Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Comparison with Classical and Machine Learning Approaches

4.3. Sources of Predictive Mismatch

4.4. Future Directions

4.5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Use of Artificial Intelligence

References

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Maritorena, S.; Mitchell, B.G.; Siegel, D.A.; Carder, K.L.; Garver, S.A.; Kahru, M.; McClain, C. Ocean color chlorophyll algorithms for SeaWiFS. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1998, 103, 24937–24953. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Maritorena, S.; Siegel, D.A.; O’Brien, M.C.; Toole, D.; Mitchell, B.G.; Kahru, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Strutton, P.; Cota, G.F.; et al. Ocean color chlorophyll a algorithms for SeaWiFS, OC2, and OC4: Version 4. SeaWiFS postlaunch calibration and validation analyses, Part 2000, 3, 9–23.

- Hu, C.; Lee, Z.; Franz, B. Chlorophyll aalgorithms for oligotrophic oceans: A novel approach based on three-band reflectance difference. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2012, 117. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Werdell, P.J. Chlorophyll algorithms for ocean color sensors - OC4, OC5 & OC6. Remote Sensing of Environment 2019, 229, 32–47. [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.; Bretthorst, G. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science; Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Scheemaekere, X.D.; Szafarz, A. The Inference Fallacy From Bernoulli to Kolmogorov, 2011. CEB Working Paper N° 11/006, February 2011.

- Clayton, A. Bernoulli’s Fallacy: Statistical Illogic and the Crisis of Modern Science; Columbia University Press, 2022.

- Baker, M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 2016, 533, 452–454. [CrossRef]

- Cobey, K.D.; Ebrahimzadeh, S.; Page, M.J.; Thibault, R.T.; Nguyen, P.Y.; Abu-Dalfa, F.; Moher, D. Biomedical researchers’ perspectives on the reproducibility of research. PLoS biology 2024, 22, e3002870.

- Gal, Y. Uncertainty in Deep Learning. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 2016.

- Ghahramani, Z. Probabilistic machine learning and artificial intelligence. Nature 2015, 521, 452–459.

- Werther, M.; Burggraaff, O. Dive Into the Unknown: Embracing Uncertainty to Advance Aquatic Remote Sensing. Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 3, 0070. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer, 2006.

- Gruber, C.; Schenk, P.O.; Schierholz, M.; Kreuter, F.; Kauermann, G. Sources of Uncertainty in Supervised Machine Learning – A Statisticians’ View, 2025, [arXiv:stat.ML/2305.16703].

- Seegers, B.N.; Stumpf, R.P.; Schaeffer, B.A.; Loftin, K.A.; Werdell, P.J. Performance metrics for the assessment of satellite data products: an ocean color case study. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 7404–7422. [CrossRef]

- Frouin, R.; Pelletier, B. Bayesian methodology for inverting satellite ocean-color data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2015, pp. 332–360. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Shi, L.; Ma, S. Merging Satellite Ocean Color Data With Bayesian Maximum Entropy Method. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2015, 8, 3294–3304. [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.E.; Karaköylü, E.M. Bayesian Models for Deriving Biogeochemical Information from Satellite Ocean Color. EarthArXiv 2019. [CrossRef]

- Werther, M.; Odermatt, D.; Simis, S.G.H.; Gurlin, D.; Lehmann, M.K.; Kutser, T.; Gupana, R.; Varley, A.; Hunter, P.D.; Tyler, A.N.; et al. A Bayesian approach for remote sensing of chlorophyll-a and associated retrieval uncertainty in oligotrophic and mesotrophic lakes. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 283, 113295. [CrossRef]

- Werther, M.; Burggraaff, O.; Gurlin, D.; Saranathan, A.M.; Balasubramanian, S.V.; Giardino, C.; Braga, F.; Bresciani, M.; Pellegrino, A.; Pinardi, M.; et al. On the generalization ability of probabilistic neural networks for hyperspectral remote sensing of absorption properties across optically complex waters. Remote Sensing of Environment 2025, 328, 114820. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, Z.K.; McKinna, L.I.W.; Werdell, P.J.; Cetinić, I. Bayesian approach to a generalized inherent optical property model. Optics Express 2023, 31, 22790 – 22801. [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Vehtari, A.; Simpson, D.; Margossian, C.C.; Carpenter, B.; Yao, Y.; Kennedy, L.; Gabry, J.; Bürkner, P.C.; Modrák, M. Bayesian Workflow, 2020, [arXiv:stat.ME/2011.01808].

- Wolkovich, E.; Davies, T.J.; Pearse, W.D.; Betancourt, M. A four-step Bayesian workflow for improving ecological science, 2024, [arXiv:q-bio.QM/2408.02603].

- JCGM. Evaluation of Measurement Data – Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Technical Report JCGM 100:2008, Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM), Sèvres, France, 2008. GUM 1995 with minor corrections.

- Tilstone, G.; Mélin, F.; Jackson, T.; Valente, A.; Bailey, S.; Moore, T.; Kahru, M.; Boss, E.; Mitchell, B.G.; Wang, M.; et al. Uncertainties in Ocean Colour Remote Sensing. Technical Report Report 18, International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG), Dartmouth, Canada, 2020. IOCCG Report Series, 124 pp.

- Werdell, P.; Bailey, S. An improved bio-optical data set for ocean color algorithm development and satellite data product validation. Remote Sensing of Environment 2005, 98, 122–140.

- Abril-Pla, O.; Andreani, V.; Carroll, C.; Dong, L.; Fonnesbeck, C.J.; Kochurov, M.; Kumar, R.; Lao, J.; Luhmann, C.C.; Martin, O.A.; et al. PyMC: a modern, and comprehensive probabilistic programming framework in Python. PeerJ Computer Science 2023, 9, e1516. [CrossRef]

- Homan, M.D.; Gelman, A. The No-U-turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1593–1623.

- McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan, 2 ed.; CRC Press, 2020.

- Säilynoja, T.; Bürkner, P.C.; Vehtari, A. Graphical test for discrete uniformity and its applications in goodness-of-fit evaluation and multiple sample comparison. Statistics and Computing 2022, 32. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.B.; Bonici, M.; McGee, G.; Percival, W.J. LOO-PIT: A sensitive posterior test. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2025, 2025, 008. [CrossRef]

- Vehtari, A.; Simpson, D.; Gelman, A.; Yao, Y.; Gabry, J. Pareto Smoothed Importance Sampling, 2024, [arXiv:stat.CO/1507.02646].

- Vehtari, A.; Gelman, A.; Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Statistics and Computing 2016, 27, 1413–1432. [CrossRef]

| Model | Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Polynomial Regression | Bayesian re-framing of OCx (OC6-style), with a 4th-order polynomial on log(MBR) predicting log(Chl) |

| Model 2 | Hierarchical Linear Regression (HLR) | Partial pooling across MBR numerator groups, each with its own intercept and slope |

| Model 5 | Heteroscedastic HLR | Extends Model 2 by modeling log() as a linear function of log(MBR), with group-specific slopes and intercepts. |

| Model | Rank | ELPDLOO | pLOO | ELPD diff | Weight | SE | dSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5 | 1 | -0.53 | 15.55 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 28.08 | 0.00 |

| Model 2 | 2 | -113.92 | 9.77 | 113.39 | 0.00 | 27.58 | 12.53 |

| Model 1 | 3 | -144.47 | 5.32 | 143.94 | 0.04 | 31.64 | 21.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).