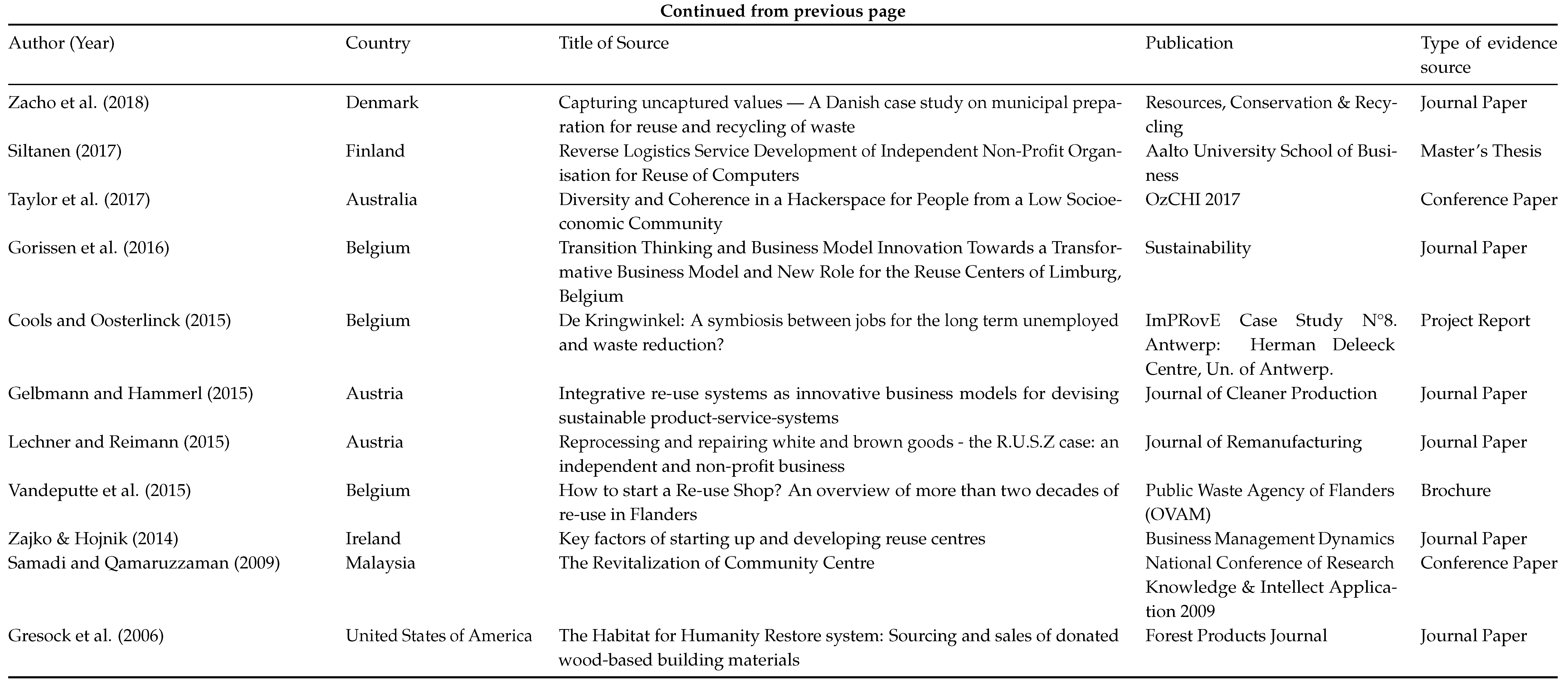

3.1. Source Selection & Organisational Archetypes

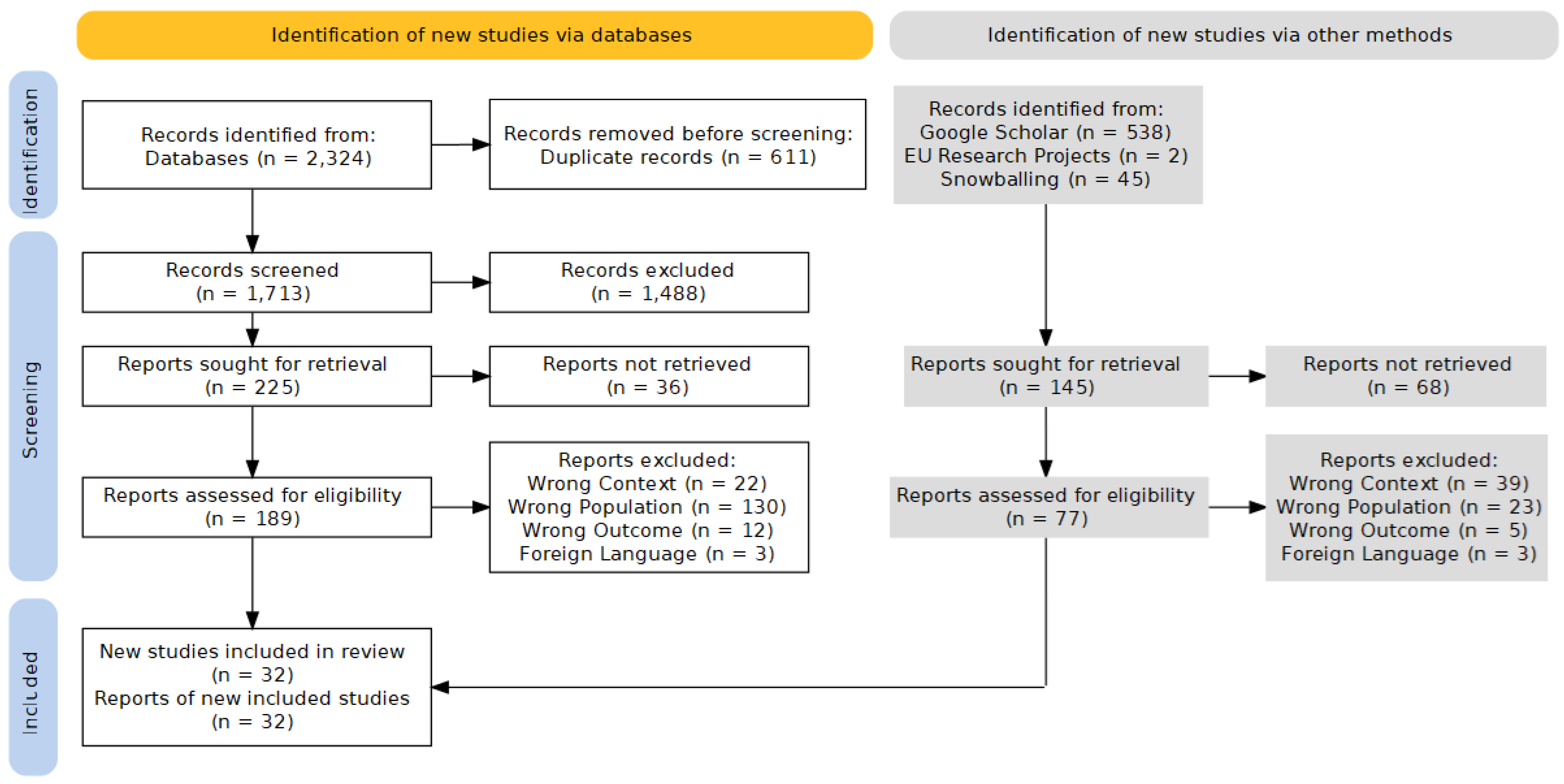

A total of 2,324 records were retrieved through database searches, and an additional 585 were obtained through grey literature and hand-searching. The process of identifying, screening, and selecting sources is depicted in a PRISMA-ScR flow diagram in

Appendix C. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 266 sources were evaluated for eligibility, after reading their full-texts and further applying the eligibility criteria. Of these, 30 sources were included in the review, from which 42 unique organizations were identified and analyzed.

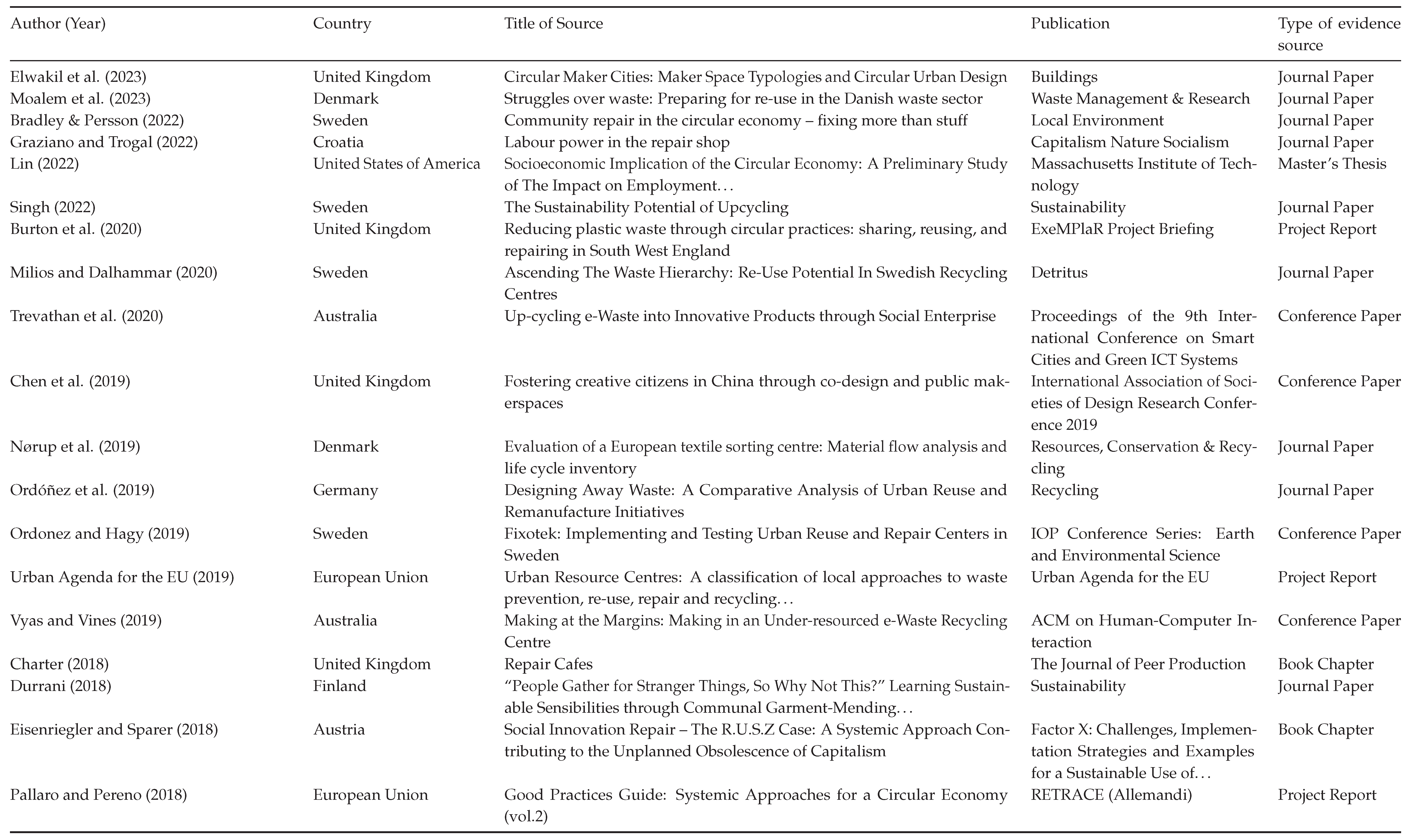

The complete list of sources selected and analyzed can be found in

Appendix D, including the country that hosted the research and the type of evidence source. Among the countries hosting the most sources, Sweden and the United Kingdom stand out with 4 each, while Austria, Belgium, Denmark, and Australia have hosted three sources each.

Appendix E summarizes the research methods employed by the 23 scientific studies. Case Study is the most commonly employed method, found in 12 studies, followed by mixed-methods (4) and Action Research (3).

Appendix F presents the list of 42 organizations retrieved from the sources, the number of units, and the source(s) in which they were identified.

Table 1 presents the archetypes identified during the coding process. Six main archetypes and five sub-types were identified, organized by the CE’s recovery possibilities in the Butterfly Diagram, with one additional category, hereby called "Multi-purpose Social CE". Most of the archetypes identified are explicitly used by the organizations themselves—e.g., Library of Things, Repair Cafés, or Reuse Shops—while "Sorting and Recovery Hubs" and "Social-support Enterprises" are inferred; no explicit naming was identified other than their functional labeling (e.g., recycling center). With a Share functional emphasis, the

Library of Things (LoT) lends or rents household appliances, toys, kitchenware, and musical instruments—services normally offered via e-commerce platforms. LoTs are often constituted as Social Enterprises and funded via membership fees and donations. Three such organizations are identified.

With a Maintain/Prolong functional emphasis, Repair Workshops (RpW) mainly run repair events called Repair Cafés—sessions where you can bring defective appliances with the expectation of getting them fixed by some of the volunteers also attending those sessions. These venues often offer toolkits for the repair of many different products. They are frequently constituted as associations and are supported by public and private funding. Seven of these organizations are identified, with the Stitching Repair Café Association, based in The Netherlands, achieving international status as it gathers thousands of initiatives promoting repair cafés around the world. Most of these initiatives are not legally constituted, however. Out of the seven RpW identified, four are a special type of RpW: the Do-it-yourself bicycle repair (), which provides the tools and support for any bicycle owner to take their bicycle there and fix it on their own.

With a Reuse/Redistribute emphasis, Reuse Centres (RuC) focus on recovering, redistributing, and/or reselling second-hand products such as household appliances, toys, bicycles, textiles, and books, which are sourced from collection points and individual pick-ups. Constituted as social enterprises (SEs) or Charities, RuCs are granted public and private funding, employing socially vulnerable individuals, e.g., long-term unemployed persons or refugees. They can also be called second-hand shops, reuse stores/labs, reuse networks, reuse centers, or community reuse centers/hubs. From the 13 such organizations identified, seven of them are structured as chains: the , sharing brand, label, and work methods. Makerspaces () have the functional emphasis of refurbishing and repurposing products. They can also be called hackerspaces, located in warehouses where they incubate design or art projects developed by social innovators or socially vulnerable employees. These projects can be funded via employment subsidies or other private sources. Six such organizations are identified.

With an emphasis on Recycling, Sorting and Recovery Hubs (SRH) are often conceived as purpose-built centers that handle construction materials and recyclables, such as paper and plastic, facilitating the recycling of materials received from retailers and companies. SRHs can be funded through municipal waste management fees collected. They can also employ socially vulnerable individuals and are called "recycling centers/stations". Eight SRHs have been found, three of which also feature small shops where second-hand products are redistributed or recommercialized. Finally, another category is added to the typology to include those organizations that are primarily focused on social wellbeing: the Multi-purpose social CE, for which the archetype Social-support enterprise (SsE) is proposed based on the four organizations identified.

The proliferation of terminology in the analyzed literature reflects a broader conceptual fragmentation. Multiple definitions have been proposed, each covering a different perspective on these organizations. These definitions are also gathered and compared in the following subsection.

3.2. A Fragmented Conceptual Landscape

Although numerous terms are used to describe organizations operating in this space, these labels are often inconsistently defined and rooted in context-specific policy or project discourses. Furthermore, constructs supported by formal disciplinary theorization have limited analytical utility and transferability. This fragmentation reflects the plural origins of these initiatives, which emerge from such different domains as social entrepreneurship, waste management, grassroots innovation, urban sustainability, and community development. Thus, the same or similar organizational forms can be classified differently, depending on the analytical framework employed: in terms of their physical infrastructure (e.g., Circular Maker Spaces), their governance logic (e.g., work-integrated social enterprises),or by their function within policy agendas (e.g., Urban Resource Centres).

Table 2 presents seven overlapping definitions proposed as a result of a focused study or formalized as theoretical frameworks, along with their stance regarding physical space and formal constitution.

Community Organisations and

ECO-WISES arise from studies in the health sector and policy, respectively. Both definitions are specific about the legal constitution - Social Enterprise -; however, neither is explicit about a physical space. The

Reuse Centre’ is also specific about social enterprise as a legal constitution and about the physical space. Definitions of

URC,

CURE,

Repair Cafés, and

Circular Makers explicitly state the need for a physical space without specifying any formal constitution as a requirement. Furthermore, the term URC has been previously used in scientific literature in the context of a Pakistani NGO involved in the settlement of low-income populations. CURE refers to remanufacturing as multiple recovery processes, which can be misleading since little evidence of remanufacturing activities taking place within any of the 42 organizations investigated was found.

The identification and analysis of the seven definitions, their limitations, and the observation of consistent patterns across diverse examples led to the emergence of a construct. This construct specifies the need for a physical space, explicitly calling for a formal constitution—one that is not limited to SEs, but that can assume the most convenient formal constitution for the organization’s mission. Such constructs should also support positioning such initiatives more clearly within CE discourse and policy design. The Community-oriented Reuse Organisation model (COREO), which represents an ideal version of organizations recovering products and materials while engaging local communities and generating social wellbeing, is proposed and explained in the following subsection.

3.3. The Community-Oriented Reuse Organisation Model

Departing from the concept of URC, the COREO construct emerged inductively during data synthesis. The primary objective was to identify initiatives that exhibited characteristics similar to those found for the URCs. As evidence was gathered and synthesized, it became evident that, despite being presented through fragmented terminology, a subset of initiatives working with R-strategies consistently exhibited a localized physical infrastructure aimed at fostering social engagement through community-facing activities and some sort of organizational structure that conferred legitimacy, stability, and resilience. These features co-occurred across diverse contexts and institutional settings, suggesting the presence of an emergent model not yet coherently conceptualized in the literature. Through the inductive synthesis of the reuse initiatives analyzed, the Community-Oriented Reuse Organization (COREO) is defined as a

formally structured organisation that operates systems for reuse, repair, or redistribution, engaging local communities through dedicated physical spaces, combining material stewardship with social inclusion.

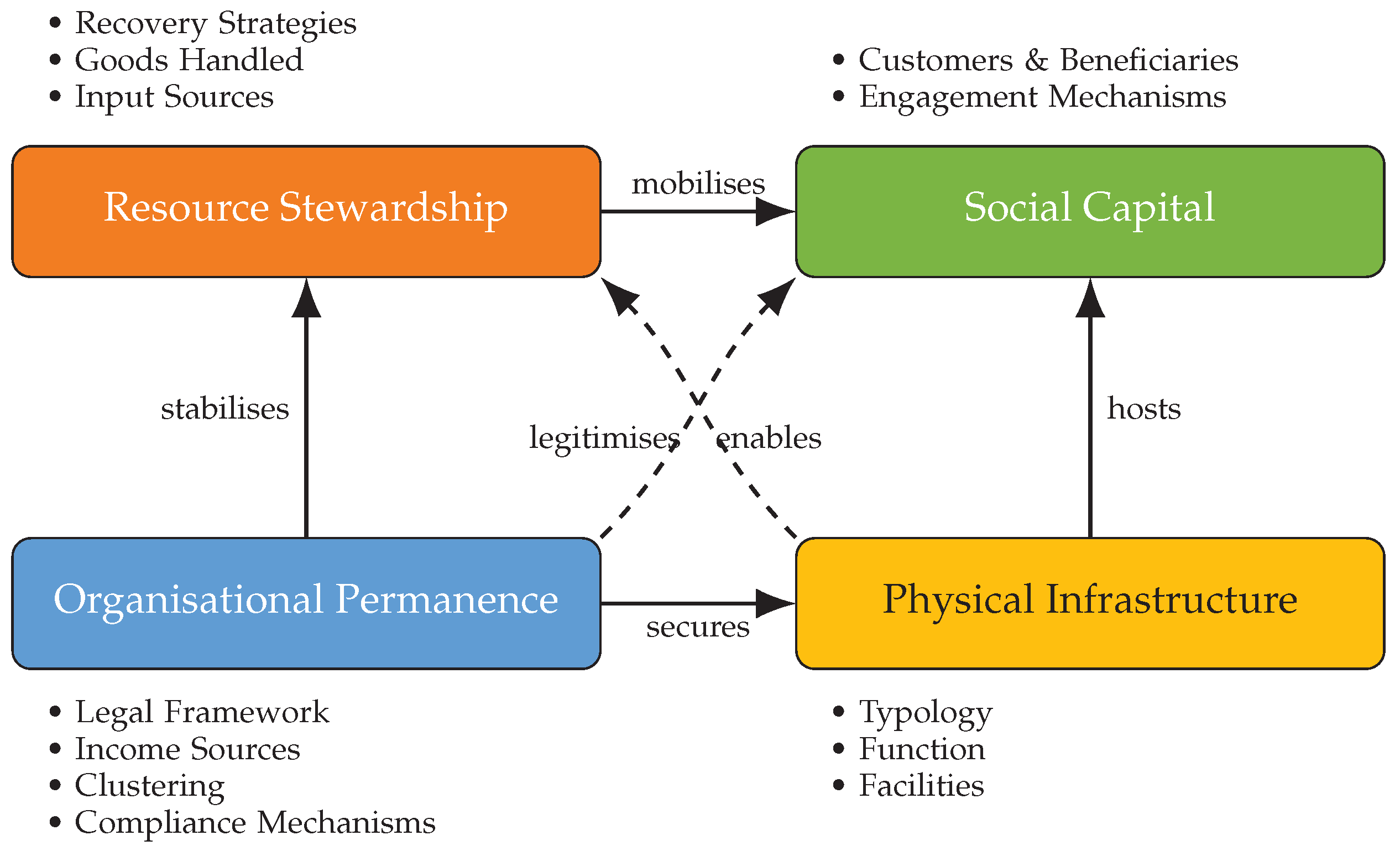

Based on the COREO definition, we propose four interdependent core elements through which COREO’s operations can be understood:

Resource Stewardship stems from the commitment to preserve material value across a wide range of circular strategies;

Social Capital refers to both the input and outcome of community engagement, social trust, and collective empowerment;

Physical Infrastructure anchors activities spatially and enables public access and visibility;

Organizational Permanence reflects the ability to maintain structure, partnerships, and financial stability over time.

The four core elements of the model should not be seen in isolation but as

interwoven capabilities, as depicted in

Figure 2. Together, they constitute a viable configuration for sustained, community-integrated circular practice. Each element addresses a necessary domain of organizational functioning: social legitimacy, institutional resilience, environmental effectiveness, and spatial embedding. Although individually observable, their full significance becomes apparent in their interaction. Physical infrastructure without permanence risks precarity; material recovery without social engagement limits public trust and uptake; permanence without community ties can lead to institutional inertia. In this sense, COREOs exemplify the logic of

strong sustainability, where environmental goals are inseparable from social and institutional foundations.

The following subsections articulate the four elements as mutually reinforcing conditions that empower reuse organizations to drive sustainability transitions at multiple levels.

3.3.1. Resource Stewardship

The COREO plays an important role in extending product lifecycles and reducing material waste through diverse and adaptive recovery practices. Their stewardship approach encompasses a wide range of strategies, from sharing and maintenance to refurbishment and preparation for recycling. These recovery efforts span a broad array of materials, including textiles, electronics, furniture, household goods, and construction materials. Rather than specializing in a single activity, most organizations operate across multiple strategies, often in combination, enabling them to intervene in the material lifecycle at various points, creating multiple recovery loops that maximize value retention.

What distinguishes COREOs is not only the breadth of recovery strategies but also the systemic coordination of these strategies across various input sources. Items are sourced from a mix of private donations, drop-offs, community waste centers, take-back systems, and commercial partners (e.g., retailers, demolition contractors). This diversity highlights COREOs’ embeddedness in multiple material flows and their capacity to adapt practices based on available streams.

Their contribution to the CE and sustainability is legitimized through the monitoring of outcomes listed in

Table 3. Among the most commonly reported metrics are recovery and rejection rates—with remarkable medians of 0.935 and 0.060, respectively—and GHG emissions avoided—with an average of 130,170 tonnes of

avoided in one year. These main aspects of COREOs are summarized in our first proposition:

Proposition 1: COREOs enact resource stewardship by bridging diverse product and material streams for which recovery strategies are mobilised, resulting in high yields of resource recovery and indirect environmental benefits in the form of avoided emissions.

COREOs apply a layered logic of reuse; for instance, household goods may be received via drop-off, sorted for repair or redistribution, and then offered through second-hand retail, lending schemes, or donation platforms. By dealing with a broad set of materials—from furniture and e-waste to clothing, garden waste, and even hazardous or construction waste—these organizations expand the scope of circularity beyond conventional categories. Moreover, COREOs operate through diverse sourcing mechanisms, from private donations and collection points to partnerships with retailers, community waste centres, and construction take-back schemes. This infrastructural openness is key to their effectiveness, enabling them to bridge gaps in public waste systems while tailoring recovery efforts to local contexts.

The recovery rates observed suggest that many COREOs outperform typical municipal waste management facilities in terms of material efficiency. Although reporting inconsistencies remain, the data reflect COREOs’ potential to redefine circularity as a place-based, socially integrated system for environmental impact.

3.3.2. Social Capital

In addition to managing material flows, COREOs play an important role in cultivating the social foundations that support CE transitions. These organizations engage the public through a variety of channels—from communication platforms and pop-up events to volunteer programs and educational activities. These forms of engagement build familiarity, trust, and a sense of inclusion in circular practices. Three main types of engagement mechanisms are observed. First, communicative strategies such as websites, social media, newspapers, and public campaigns are used to raise awareness and maintain visibility. Second, COREOs organize occasional activities like repair cafés, workshops, exhibitions, and school visits, which offer low-barrier opportunities for participation and learning. Third, they foster more sustained, binding relationships through volunteering, internships, social employment, and co-creative projects. This combination enables multiple entry points for engagement—each tailored to different levels of commitment and capacity.

A wide range of social impact indicators can be monitored, as summarized in

Table 4, including current personnel—with an average of roughly 7,500 people, including employees and volunteers—a median of 732 employees trained, and millions of people benefitted. Importantly, the target audiences extend beyond individual citizens to include local businesses, charities, schools, waste operators, and authorities. These connections help COREOs build legitimacy and strengthen their role as civic actors embedded in the community. In doing so, COREOs do not only divert waste or provide goods—they create inclusive, participatory environments where circular practices become socially meaningful and culturally embedded.

Proposition 2. COREOs cultivate social capital by engaging diverse audiences through communication, learning, and participation mechanisms that strengthen trust and embed circular practices in the community.

Community-oriented reuse initiatives activate and produce social value. Many of the initiatives studied involved marginalized groups, promoted local skills, facilitated volunteering, or enacted participatory governance. Social capital appears as both a resource, enabling operational execution, and an outcome, building trust, reciprocity, and empowerment. This dimension positions COREOs as a social infrastructure: embedded, inclusive, and capable of contributing to community cohesion and wellbeing. It also opens space to connect circularity with broader equity and justice goals, reinforcing the argument for integrating social metrics into circular economy assessment frameworks.

3.3.3. Physical Infrastructure

COREOs operate across a diverse set of physical spaces that support their recovery, redistribution, and educational functions. These infrastructures vary in typology, function, and specific facilities, reflecting how COREOs creatively adapt available space to meet circular and community needs. In terms of typology, COREOs operate out of shops, warehouses, garages, depots, cultural centers, and even churches or libraries. Some spaces are purpose-built for reuse or repair activities, while others are repurposed from existing retail, industrial, or civic infrastructure. This adaptability enables COREOs to function in both dense urban and peripheral settings, using whatever spatial resources are available.

These physical infrastructures are not limited to material processing. Many COREOs incorporate educational and civic functions through facilities such as classrooms, meeting rooms, DIY workspaces, and conference areas. Others offer public-facing spaces, such as swap corners or exhibition areas, to engage the community more directly. In this regard, COREOs can monitor how their spatial configurations contribute to their mission using the indicators presented in

Table 5.

Proposition 3. COREOs adapt and combine diverse physical spaces to create circular infrastructures that support recovery, redistribution, and community engagement. These spaces play a crucial role in shaping community reuse practices.

Whether in the form of reuse depots, repair workshops, or makerspaces, these dedicated sites provide not only logistical capacity but also public visibility, community anchoring, and spaces for informal social exchange. The availability and layout of physical spaces influence the types of activities that can be hosted—ranging from retail to co-creation—and directly affect user access and engagement. Physical presence is not only functional; it also fosters a tangible identity that entails legitimacy and reach. This dimension is closely aligned with the perspectives of architectural and urban studies on social infrastructure and place-based engagement.

3.3.4. Organisational Permanence

To maintain their activities over time, COREOs rely on a mix of legal, financial, and institutional strategies that help stabilize their operations. These mechanisms fall into four main categories: legal frameworks, income sources, clustering forms, and compliance practices. COREOs operate under a wide range of legal forms, including social enterprises, charities, associations, cooperatives, and public–private partnerships. This legal diversity reflects both national regulatory environments and strategic decisions regarding mission alignment, access to funding, and eligibility for public support.

To sustain their activities financially, COREOs draw from multiple income sources: membership fees, donations, repair reimbursements, grants, crowdfunding, and even waste management fees. Many also benefit from employment subsidies, particularly when engaging vulnerable or long-term unemployed populations. This diversification supports resilience and reduces over-reliance on any single funding stream. In terms of clustering, COREOs often belong to broader networks, brands, or federations that provide visibility, knowledge sharing, or shared principles. Some operate as franchises or community-led initiatives within urban or regional networks. These connections support scale and coordination while retaining local autonomy. Finally, COREOs employ various compliance mechanisms to demonstrate accountability. These include audits, performance reports, customer satisfaction surveys, product warranties, and formal procedures or policy documents.

Organizational permanence supports strategic planning, the accumulation of technical and relational capital, and the development of institutional memory. Many of the most impactful cases in the sample were embedded in local governance or public-private ecosystems that grounded their positions and extended their influence. In contrast, ad hoc or project-based initiatives often struggle with high turnover, mission drift, and financial precarity.

Table 6 shows indicators that can help track financial health. Permanence, in this context, does not equate to size or centralization, but to structural anchoring and resilience within their socio-institutional setting.

Proposition 4. COREOs stabilise their operations through diverse legal forms, income streams, partnerships, and compliance practices that support long-term viability and accountability.

COREOs consistently exhibit formal structures—such as legal incorporation, multi-year funding, or enduring partnerships—that enable operational continuity. While many COREOs operate as registered non-profits, others exhibit more hybrid characteristics; several initiatives maintain close institutional ties with municipal or national governments yet operate with considerable self-governance.

3.4. Interpreting Organisational Diversity Through the COREO Lens

The COREO model offers a conceptual lens for understanding the recurring characteristics of the COREOs. Currently at the forefront at the forefront of short-loop CE initiatives, COREOs tend to be economically fragile, and formally unstable, risking to shut down their operations due to disturbances, or transforming themselves into regular for-profit businesses and loosing their social character. This model can be used as a benchmark for assessing the COREOs and establishing development pathways that may increase their economic sustainability and legitimacy within the community they are embedded.

In this section, we examine the degree to which the organizations analyzed and archetypes identified align with the four core dimensions of the model. By synthesizing both structural diversity and available performance indicators, we assess how COREOs are realized in practice and explore the flexibility and coherence of the model across a variety of contexts. Without aiming for empirical verification, our analysis demonstrates its interpretive utility in describing current configurations and development paths.

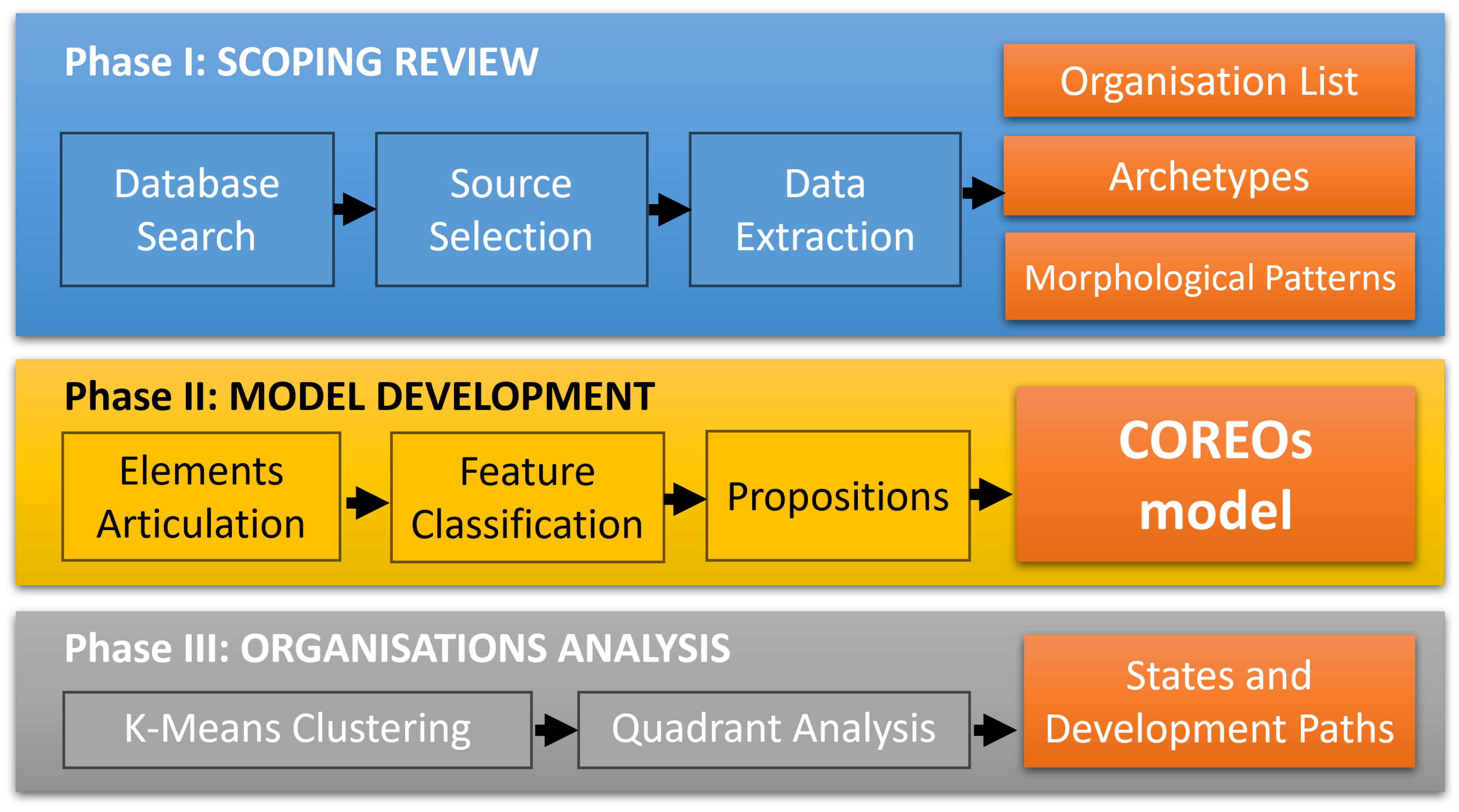

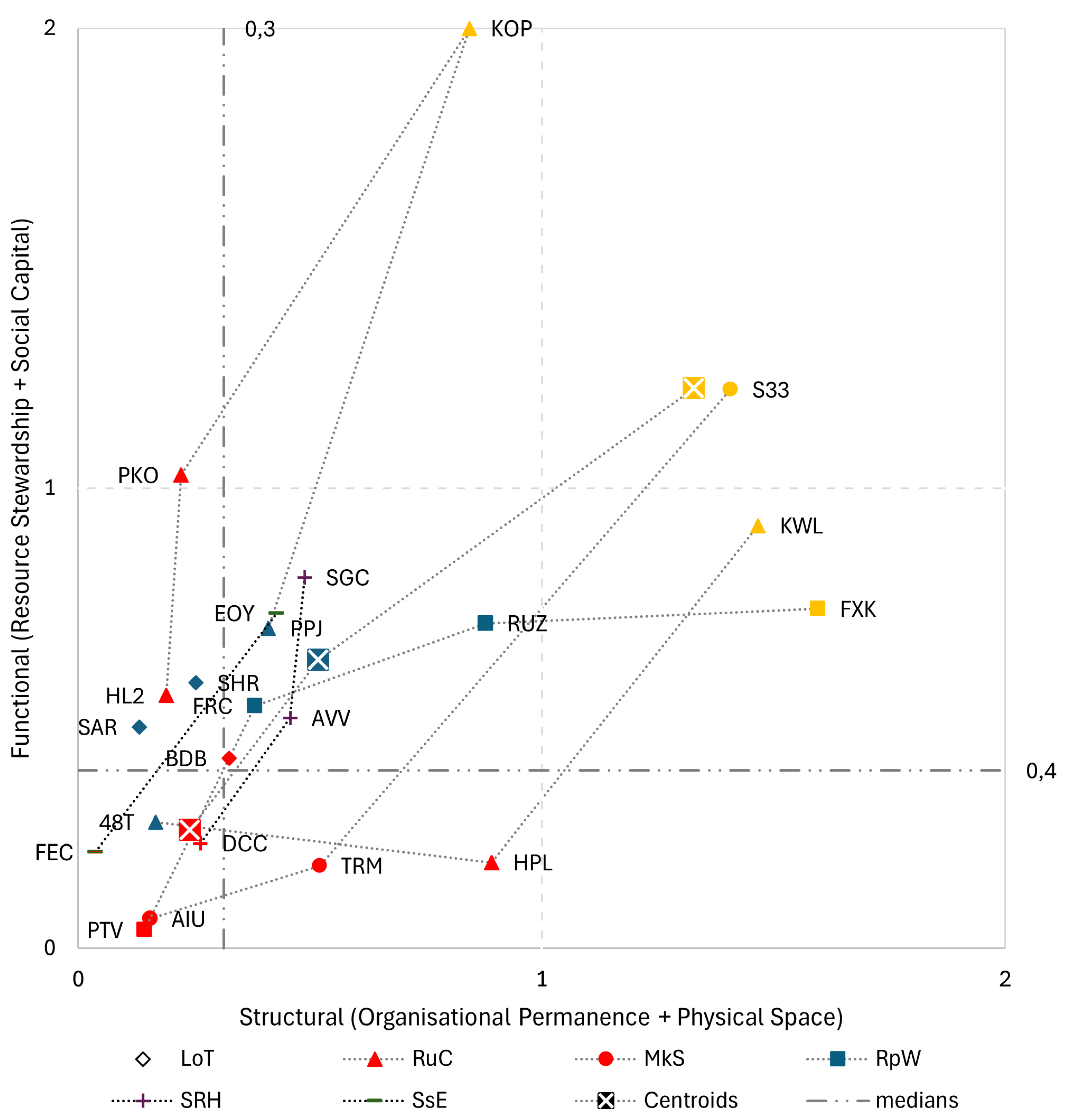

Figure 3 depicts the resulting three clusters along the structural (X-axis) and functional (Y-axis) dimensions. Archetypes feature one shape each, while Clusters receive different colors. Cluster A (red) groups organizations with lower scores on both functional and structural dimensions, suggesting smaller scale, early-stage, or niche configurations. Cluster B (blue) includes organizations with mid-range functionality and moderate structural embeddedness. Cluster C (yellow) features organizations that score highly on both axes, reflecting strong operational capabilities and institutional maturity. In the figure, the centroids for each cluster are plotted, as well as the medians for structural and functional dimensions. The medians divide the graph area into four quadrants: Q1 (bottom-left), Q2 (bottom-right), Q3 (upper-left), and Q4 (upper-right). Clusters and Quadrants are employed to outline current states and potential development paths in the following subsections.

3.4.1. Current States and Potential Development Paths

Organizations in Q1 are typically lean in structure and modest in reach, operating on the strength of reuse and repair practices, civic engagement, and informal economies. Most rely on earned income from second-hand retail and repair services, often focusing on furniture, clothing, and bicycles. Their infrastructure is minimal: DIY spaces, toolkits, and basic storage facilities. Social capital is strong: citizens are engaged through volunteering, workshops, and educational formats. They often lack long-term funding or extensive governance structures, serving as incubators of resource circularity.

Organizations in Q2 distinguish themselves by the strength of their physical and operational infrastructure. Equipped with permanent facilities such as retail shops, industrial workshops, and donation reception systems, they serve as reliable nodes in urban reuse ecosystems. Their focus is on processing volume and material flow — furniture, clothing, and textiles feature prominently — often through repair, resale, and upcycling. While functionally competent, they show fewer signs of civic engagement or participatory programming than their community-centric counterparts. Many draw support from a blend of earned income, private donations, and occasional municipal funding.

Organizations in Q3 operate at the intersection of repair culture, community education, and grassroots material circularity. Common to both clusters is a strong orientation toward public-facing services: reuse and repair workshops, informal education, and donation-based product flows. They work across household goods, electronics, and wood/furniture, often in response to local needs. These organizations are locally embedded, with strong ties to schools and community groups, broader social engagement, and basic infrastructure such as depots or multi-use warehouses.

Last, organizations in Q4 represent the mature, high-capacity end of the spectrum. Combining robust physical infrastructure with expansive community programming, they are embedded in local economies through material reuse, civic engagement, and hybrid governance. Their activities span resale, repair, upcycling, and recycling, often complemented by education, employment services, and volunteering. Cluster C organisations in this quadrant are typically mainstream actors — civic reuse centres or social enterprises with policy alignment, stable funding, and diverse operational formats.

When organizations in the same archetype but spread across different quadrants and clusters are linked, potential development paths can be drafted. For example, a makerspace like AIU could enhance their infrastructure by following what TRM presents, later developing mechanisms and programs adopted by S33. In the same way, A RuC like HL2 can expand their engagement mechanisms to resemble more closely those of PKO, and even further, like KOP—if there is the opportunity and desire. Other development paths for the archetypes SRH and RpW are also depicted; LoT organizations are too few and too similar to allow for a development pathway to be drafted.