2.1. The equation of heat movement in soil by conduction

The differential equation that describes the heat movement occurring through conduction in a three-dimensional heterogeneous-isotropic porous medium is expressed as follows [

23,

24,

26,

27]:

where

T(x,y,z, t) - is the soil temperature (K or °C) at point

z (m) at time moment

t (sec); ∂

T/∂

x, ∂

T/∂

y,

∂T/∂z - is the temperature change in the direction of the

ox, oy and

, oz axis;

∂T/∂t - is the temperature change in unit time;

ρs - is the soil bulk density (kg m

-3);

cs is the specific heat capacity (J kg

-1 °C

-1);

λx λy λz – is the component of the thermal conductivity of the soil in the

x,

y and

z directions, respectively (Wm

-1 °C

-1);

r - the source of heat inside the soil is (°C).

Experiments have shown that ∂ρs/∂T~0, ∂Cs/∂T~0, ∂λ/∂T~0 are correct for the important soil properties: density, volumetric heat capacity and thermal conductivity parameters when the temperature ranges from -50 ≤ T ≤ + 50 ºC [26, p. 13].

The general one-dimensional heat transfer equation for a homogeneous isotropic porous medium can be written as follows:

where

T(z, t) - is the soil temperature (°C) at point

z (m) at time moment

t (sec);

∂T/∂z - is the temperature change in the direction of the oz axis;

∂T/∂t - is the temperature change in unit time;

ρs - is the soil bulk density (kg m

-3);

cs is the specific heat capacity (J kg

-1 °C

-1);

λz – is the component of the thermal conductivity of the soil in the z direction (Wm

-1 °C

-1);

r - the source of heat inside the soil is (°C).

It is known that when modeling soil processes occurring in the soil-plant-atmosphere system, the main stages are identification (selection of equations describing these processes and boundary conditions) and realization implementation (solution of direct and inverse problems) of the model

Therefore, a systematic approach to analyzing the thermal regime of soil (depending on laboratory or field conditions) should sometimes involve simplification of the heat transfer equation and boundary conditions [

36].

Essential simplification of equation (1) is possible for some problems if the coefficients of heat capacity, thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of soil are set constant

It is known that one-dimensional heat transfer in soil is described by the classical thermal conductivity equation, which has the form [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]:

where T(z, t) is the soil temperature (

°C) at point z(m) at time t – time (hour, day, year); κ – thermal diffusivity of the soil (m

2 s

-1);

λ – is the thermal conductivity of the soil (Wm

-1 °C

-1); C

v = ρ

s c

s – volumetric heat capacity of the soil (J m

-3 °C

-1);

ρs - is the soil bulk density (kg m

-3); and c

s - is the specific heat capacity (J kg

-1 °C

-1); L is soil depth (m) starting from which T(z, t) = const or ∂T(L, t)/∂z = 0.

There are a number of works [

19,

20,

21,

23,

24,

25] in which solutions of the heat conduction equation (2.3) under different boundary conditions are considered. In this work we will also consider equation (2.3). In order to determine the change in soil temperature under the influence of various environmental factors depending on a time and depth, equation (1) must be solved analytically or numerically. For this purpose, Equation (1) must be defined and supplemented with initial and boundary conditions that account for the various factors influencing temperature variations in soils.

2.4. Solution of the direct problem of thermal conductivity in soil

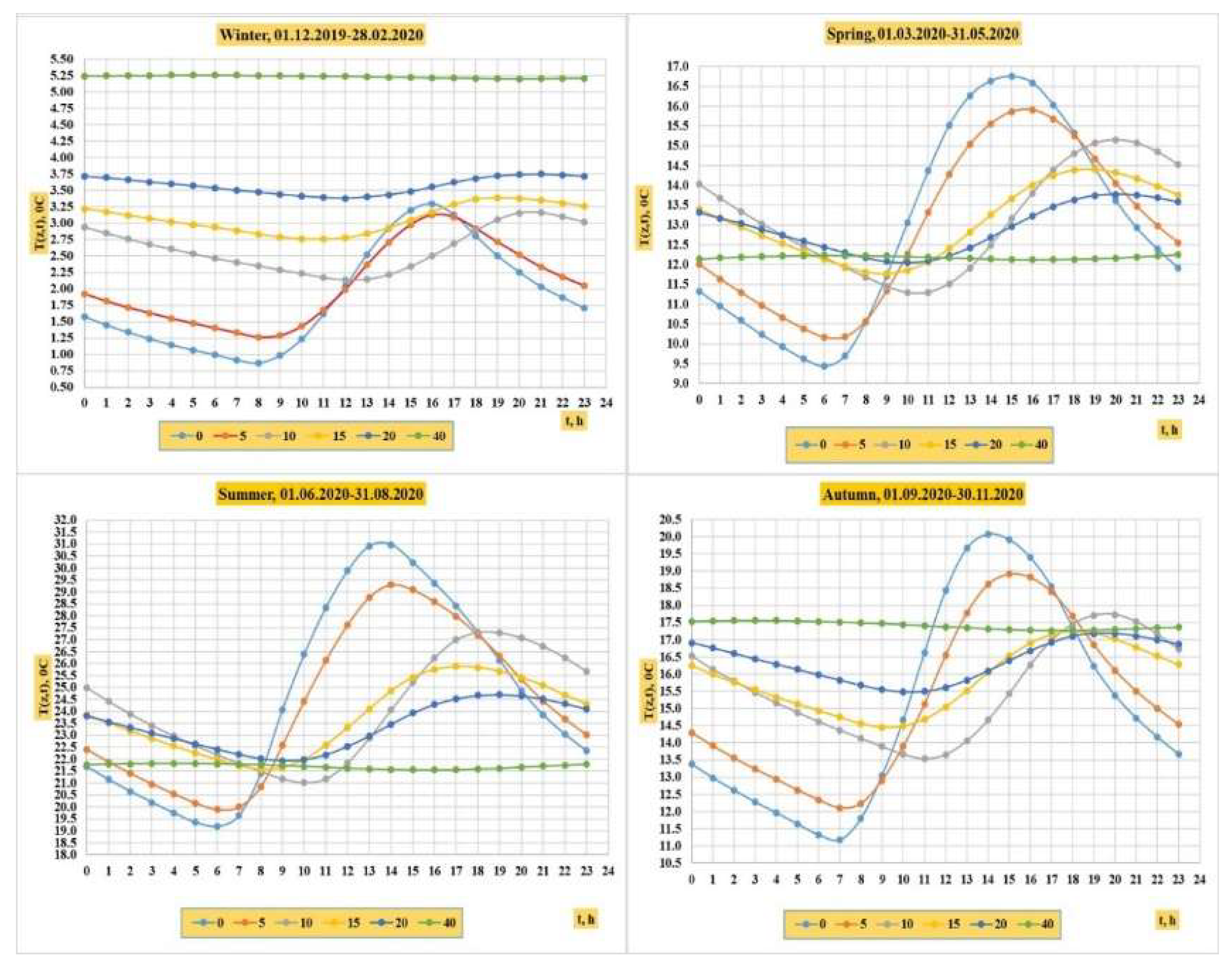

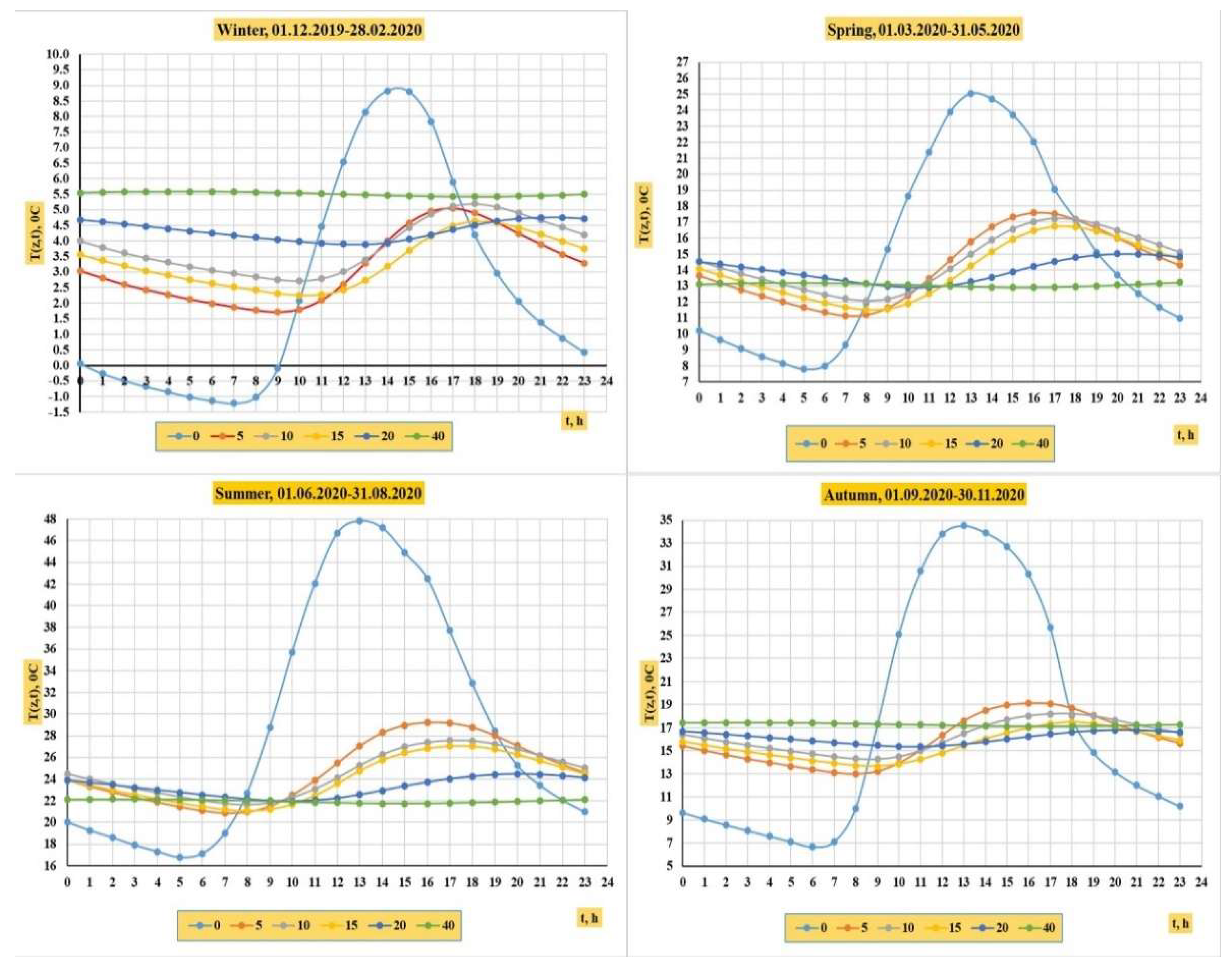

Given the initial and boundary conditions, different solutions can be proposed for the direct problem of heat transfer, i.e., the determination of the temperature dynamics at a specific depth.

In particular, of great practical interest are the problems of thermal conductivity in soils with periodically varying temper atures on the surface of soil.

Problem-1. First, let us consider the heat transfer problem for a semi-infinite homogeneous soil region, i.e. [0 ≤ z < ∞):

The solution of equation (2.16), with the initial (2.17) and boundary conditions (2.18)-(2.19), in dimensionless variables and parameters is as follows [

33]:

where,

Фj (bj, у) is the amplitude of temperature fluctuations at the dimensionless depth y; αj (bj, у) is the phase angle of the wave at the surface level for the jth harmonic at dimensionless depth y (radians).

This problem was studied by Fourier; it was first used by Kelvin to determine the course of temperature in the soil of Edinburgh [

23]:

As correctly noted in [

33,

35,

38], when performing practical calculations, it is impossible to set as input data the values of soil temperature at infinity, since they are unknown. And it is impossible to measure it. Therefore, instead of

T(z→∞,

t) it is necessary to set the temperature at some depth

L, starting from which at z >

L the value

T(z,

t) = const or ∂

T(

L, t) / ∂z = 0. Thus, condition (2.15) (∂

T(

L,

t) / ∂z = 0) is more consistent with the real conditions than boundary condition (2.14) (

T(z→∞, t) =

T0=const) [

34]. Therefore, the following boundary value problem for equation (2.16) should also be considered.

Problem-2. Next, consider the boundary value problem for the thermal conductivity equation in a finite [0 ≤z ≤ L] homogeneous soil region in the following form:

The solution of the problem (2.16), (2.18) и (2.22) with dimensionless variables and parameters is as follows [

33,

34,

36,

38]:

Where

and

- are the hyperbolic cosine and sine, respectively.

In the analytical methods developed for the determination of the parameters of the heat and mass transport models, it has been shown that the data at any depth

z = zi of the soil profile are determined with statistically greater variation than the average data in the [0, L] layer of the soil. In other words, the average temperature of a certain soil layer (e.g. 0-20 or 0-40 cm layer), varies less than the temperature at a certain depth

z = zi [

39,

40].

Therefore, the average values of soil layer temperature should be used to determine the thermal diffusivity coefficient from the data of field and laboratory experiments.

The use of average temperature values in determining the heat emission parameter is called the average integral method.

For this purpose, to determine the average temperature in the layer 0 ≤

z ≤

L, let us calculate the definite integral of the dimensionless solution (2.20) of equation (2.16) in the interval 0 ≤

y ≤ 1 with respect to the variable

y.

Similarly, for the solution (2.23) with arbitrary harmonic m, the average temperature in the layer 0 ≤ z ≤

L can be determined as follows:

These solutions are widely used in soil science for two purposes: estimating temperature values in the soil profile and calculating thermal conductivity (k).

2.5. Solution of the inverse problem of thermal conductivity in soil

Most methods for determining the thermal diffusivity of soil are based on solving inverse problems of thermal conductivity, which are obtained under given boundary conditions. Depending on the boundary conditions, different methods are obtained.

A more detailed review of studies on the determination of the diffusion parameter in soils is given in many works [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

27,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

This paper details methods for determining the thermal diffusivity using analytical solutions (2.20) and (2.23) found by second-order boundary conditions ∂T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0 and ∂T(z=L, t)/∂z=0.

Depending on the use of measured temperature values of the soil profile, these methods are divided into 3 classes: layered, point, and numerical (harmonic) methods.

These methods are based on using 1) temperature values at two different depths of the soil profile, e.g. z=zi and z=zi+1, 2) temperature values at a certain depth z=zi and 3) the value of the average temperature in the [0, L] layer of the soil.

2.5.1. a. layered methods

These methods are based on temperature measurements at two different soil profile depths z=zi and z=zi+1 and are called layerd methods. In addition, these layered (classical) methods will be denoted as M1, M2, M3, M4 algorithms.

2.5.1. b. Point methods

These methods are based on the use of measured temperature values at a certain depth

z = zi of the soil profile and the amplitude (Ta) of the soil surface temperature wave and are called

point methods [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

38]. In addition, these point (proposed) methods will be denoted as algorithms M5, M6, M7, M8.

2.5.1. c. Numerical (Harmonic) methods

The value of heat diffusion (κ) is selected iteratively in a way that minimizes the sum of the differences between the measured temperature values

Tmes(

zi,

ti) at the desired depth z

i and the temperature values

Tcal (

zi,

ti) estimated according to solutions (2.20) or (2.23) [

27,

28,

29,

30,

33]:

For example, the iteration can be continued until the condition is met. The sum of squares will be composed of 24 whole (r=0,1,2,…,24) or half-hour (r=0.5,1.5,…,23.5) differences between measured and calculated temperature.

The existing and proposed methods for calculating the thermal diffusivity parameter, developed respectively for the boundary conditions ∂T(∞, t)/∂z=0 and ∂T(z=L, t)/∂z=0, are given below.

The existing (Classical) methods for calculating the thermal diffusivity parameter derived from the boundary condition ∂T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0 are as follows

Classical methods. Below we present classical algorithms based on the solution of inverse problems of the heat transfer equation obtained for a semi-infinite homogeneous soil region under the boundary conditions ∂T(∞, t)/∂z=0 when the diurnal temperature variation at the soil surface is represented by one (M1, M4) and two (M2, M3) harmonics;

М1. Amplitude Method. [

19,

21,

23]:

M2. Arctangent Method [

22]:

M3. Logarithmic Method [

20]:

M4. Phase Method [

24]:

where τ

0 in algorithms (2.30)– (2.33) is the period of the heat wave (for example, 24 hours for daily observations);

Tmin (z) and

Tmax (z) are minimum and maximum tem-perature values during measurements at depths z = z

i and z =

zi+1, respectively;

Ti(z) and

Ti+1(z) in algorithms (2.31) and (2.32) are the values of soil temperature at depths z = z

i and z =

zi+1, respectively, at time

ti =

iτ0/4 (

i=1,2,3,4) (for this example,

τ0 = 24 h and

t1 = 6, t

2 = 12, t

3 = 18 and t

4 = 24 h); εi is the initial phase of the soil temperature at depth

zi in algorithm (2.33).

Improved methods. In contrast to the above algorithms, we continued to develop new methods that take into account the real process of heat exchange in the soil. For this purpose, we used the solution of the heat transfer equation, under the boundary conditions ∂

T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0 and ∂

T(z

=L, t)/∂z=0, obtained for limited and semi-limited soil thickness. These methods are based on the use of measured temperature values at a certain depth z = z

i of the soil profile and the amplitude (T

a) of the soil surface temperature wave and are called

point methods [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Tthese point (proposed) methods will be denoted as algorithms M5, M6, M7, M8. The proposed methods for calculating the thermal diffusivity of soil are presented below.

The following methods (M5 and M6) are developed on the basis of a boundary condition of the second kind in the infinity z→∞, i.e. ∂T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0, when the diurnal temperature fluctuations at the soil surface is represented by one (m=1) (M5) and two (m=2) (M6) harmonics.

These methods, unlike the classical ones (М1-М4), include the amplitude of fluctuations (Ta) of the soil surface temperature

M5. Proposed Point method.

Algorithm including the amplitude of fluctuations (T

a) of the soil surface temperature and the logarithm (

m=1)[

36]:

where;

T(zi, tj) in the algorithm (2.34) are the soil temperature values at the depth

z=zi, at the time at the time moment

tj=j·τ0 / 4 (

j=1,2,3,4) (for

τ0 = 24 h and

t1=6,

t2=12,

t3=18 and

t4=24 h).

M6. Proposed Point method.

Algorithm including the amplitude of fluctuations (T

a) of the soil surface temperature and the logarithm (

m=2)

[36,38]:

where;

T(zi, tj) in the algorithm (2.35) are the soil temperature values at the depth

z=zi, at the time at the time moment

tj=j·τ0 / 8 (

j=1,2,…,8) (for

τ0 = 24 h and

t1=3,

t2=6,

t3=9,…,

t8=24 h).

The following methods (M7 and M8) are developed on the basis of the boundary condition of the second kind at a finite depth z=L, i.e. at ∂T(z=L, t)/∂z=0, when the daily temperature fluctuation at the soil surface is represented by one (m=1) (M7) and two (m=2) (M8) harmonics.

These methods, in addition to the amplitude of fluctuations (Ta) of the soil surface temperature, also take into account the depth of the soil profile (L).

M7. Proposed Point method.

Algorithm including the amplitude of fluctuations (

Ta) of the soil surface temperature and also take into account the depth of the soil profile (

L) (

m=1) [

36]:

where;

T(zi, tj) in the algorithm (2.36) are the soil temperature values at the depth

z=zi, at the time moment

tj=j·τ0 / 4 (

j=1,2,3,4) (for

τ0 = 24 h and

t1=6,

t2=12,

t3=18 and

t4=24 h).

Using the amplitude of fluctuations (Ta) of the soil surface temperature and the temperature values T(zi,tj) measured at different moments of time (ti = 1, 2, 3 and 4) at a given depth z = zi (in the dimensionless notation 0 ≤ yi ≤ 1) of the soil layer [0, L], we first find the value of the left side of equation (2.36), i.e. . Then, the values of the expression on the right-hand side of equation (2.36) are calculated using different values of bi > 0 for each yi=zi/L.

Then the value of

b* satisfying the condition

is determined. Finally, using the found value of

b*, the thermal diffusivity (

κi) of soil at a given depth is calculated

z=zi according to the following equation:

M8. Proposed Point method.

Algorithm including the amplitude of fluctuations (

Ta) of the soil surface temperature and also take into account the depth of the soil profile (

L) (

m=2) [

32,

33,

34]:

This method differs from M7 in that the number of harmonics on the soil surface is m=2. Also, after calculating the values of the left Mmesm=2 (b) and right Mcalm=2(b) sides of equation (2.38), the value of b*i is determined which satisfies the condition .

Finally, using the b* value, the value of the thermal diffusivity (κi) is calculated using the equation (2.37).

2.5.2. Calculation of Thermal Properties of Soil

2.5.2. a. Volumetric heat capacity

The volumetric heat capacity of the soil was calculated using the generally accepted formula [

43,

51,

52]:

where, the

Cm,s is the specific heat of the soil's solid part, J/(kg·

oC);

ρb is the soil bulk density, kg/m

3;

Cv,w is the volumetric heat capacity of the soil moisture equal to 4186.6 kJ/( m

3 oC);

Cw is the specific heat of water, J/(kg

oC);

ρw is the water density, kg/m

3;

θ is the volumetric moisture content (m

3/m

3);

Cm, org and

Cm, min are the specific heats of the organic and mineral components of the soil solid phase respectively, J/(kg

oC);

morg is the mass of soil organic matter, kg;

m is the soil mass (kg);

morg /

m is the content of organic substance in soil, %.

2.5.2. b. Calculation of other thermal properties

Other thermophysical parameters such as thermal conductivity (

λ), damping depth (

d), thermal effusion (

e), heat wave velocity (

υ) and heat wave length (

Λ), will be calculated using the following formulas, respectively [

23,

24,

27,

53,

54]:

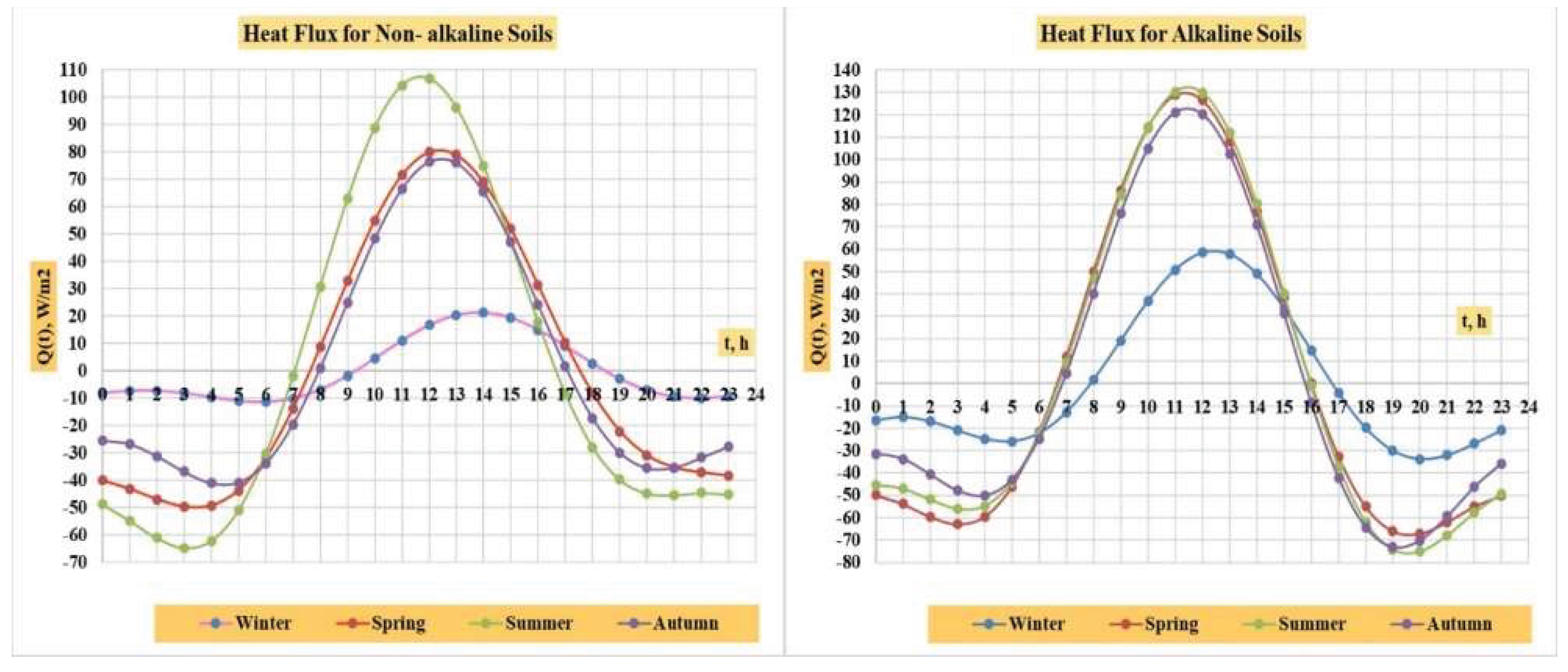

2.5.2. c. Calculation of heat flux in soil

Calculation of heat flux in soil is based on the use of values of known thermal properties. If these properties (volumetric heat capacity - Cv, diffusivity - κ and average daily soil surface temperature - T0, amplitudes - Ti and phase shifts - εi) are determined, it is possible to calculate the amount of heat and heat flux (J) passing through the soil surface and causing a certain temperature change.

The soil heat flux in a soil (J) at depth z and time t is given by the Fourier law of heat conduction can be expressed as [

19,

21,

23,

24,

50]:

where J is the soil heat flux (Wm

−2); λ is the thermal conductivity of the soil (Wm

−1 K

−1); T is the soil temperature (

oC or K) and

z is the depth from the soil surface (m); ∂T/∂z is the gradient of temperature. When referring to J at the soil surface (z=0), it is denoted

G.

Existing methods for calculating heat flow based on the found solution for the boundary condition ∂T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0.

The heat flux into the soil

q (z, t) is calculated by substituting the solution of equation (2.3) into equation (2.41). To calculate the heat flux from the soil surface to the depth, we first use the general solution (2.20) obtained for the boundary condition of the second kind, i.e. ∂T(z→∞, t)/∂z=0 in equation (2.41). It can be easily shown that the heat flux into the soil at any depth z=

h and time t is of the form [

23,

24]:

Proposed methods for calculating heat flow based on the found solution for the boundary condition ∂T(z=L, t)/∂z=0.

Similarly, using the general solution (2.23) obtained for the boundary condition of the second kind, i.e., ∂T(z=L, t)/∂z=0 into equation (2.41), we have [

32,

33]:

where,

2.5.3. Comparison of Methods, Models assessment

To determine the values of the parameters of empirical models (type (2.10)), as well as to compare the measured T

mes(z

i,t

j) and calculated T

cal(z

i,t

j) temperature values of the studied soils using formulas (2.20) and (2.23) for one and two harmonics, various criteria are used, which are given below [

54,

55,

56]:

1. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (

r):

2. Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient (NSE) [

56].

This formula can be applied for linear regression and original data on any model.

3. Adjusted coefficient of determination or adjusted R-squared (R

2adj)

4. Root mean squared error (RMSE):

5. Normalized root mean square error (NRMSE),

6. Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE):

7. Mean absolute error (MAE),

8. The bias is used as a measure for a systematic underlying mismatch between the observed and predicted temperature values of soils

9. Agreement index or Willmott’s index of agreement (D):

10. Theil's forecast accuracy coefficient:

11. Akaike information criterion:

In equations (2.46)-(2.53), the following notation is adopted: Ti represents the observed values of the dependent variable; represents the estimated values of the dependent variable; represents the average of the observed values; n represents the number of data points; p represents the number of estimable parameters in the approximating model, including the intercept term, where p<n; R2represents the coefficient of determination; ESS represents the sum of squared errors and is given by .

In our study, the computation of model parameters is carried out using the implementation of the Levenberg-Marquardt method in the STATISTICA-7 software package.