1. Introduction

Hip fractures are one of the most frequently treated fractures in the world, with over 10 million fractures treated yearly worldwide[

1].

Subtrochanteric fractures are a subtype of hip fractures defined as fractures of the proximal femur that occur within 5 cm of the distal extent of the lesser trochanter[

2]. Overall incidence of these fractures is estimated to be around 15-20 per 100,000 population, accounting for 10% to 30% of all hip fractures[

2,

3].

This fracture is difficult to treat and is prone to nonunion. It is estimated that, with modern techniques of treatment, about 7-20% of subtrochanteric fractures will develop nonunion[

3].

The main factors involved in this high rate of nonunion are twofold. First, the high mechanical stress in this zone. The subtrochanteric area bears a very high varus stress in anatomic conditions, which is even higher if a non-anatomical reduction of the fracture (in varus) is achieved when fixation is carried out[

4]. Second, the high cortical bone composition of this area. The cortical bone has less vascular flow, and its capacity to heal is somewhat less than trabecular bone[

4]. These two factors make this area more prone to nonunion than neighboring areas, like the intertrochanteric region[

4].

Many good papers have recently reviewed the treatment of subtrochanteric fracture nonunion[

2,

5]. DeRogatis[

5] recently published the best review on the treatment of subtrochanteric hip fracture nonunions. In their conclusions, they claimed that study heterogeneity precluded a formal meta-analysis. Many techniques and procedures are mixed in many papers, making it difficult to retrieve clear conclusions.

Every surgical technique comprises many surgical steps. Many of them are possible to combine, and everyone has the potential to enhance or worsen healing.

We have recently reported the results of the first 5 patients with a novel technique that implies a dynamic fixation of the nonunion site, allowing for full correction of varus and leg length discrepancy.

The objective of this review is to describe the technique in detail and to analyse in detail in the literature, several key surgical steps when reconstructing a subtrochanteric nonunion.

2. Materials and Methods

A general view of this technique has just been published by us[

6]. Some details of that technique were missing in the original article. So, a detailed report of the technique is here.

The bibliographic review was performed according to the principles of de PRISMA ScR requirements[

7]. The detailed protocol has been revised by all authors. The final protocol was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework on 23 July 2025 (

https://osf.io/2tygw/).

To be included in the review, papers should be centered on the surgical technique to treat subtrochanteric nonunions. Peer-reviewed journal papers were included if they were: published between the period of 2000–2025, written in English or Spanish, involved human participants, and described the surgical technique employed in sufficient detail (at least: implant used, osteotomy or not, bone graft used, postoperative protocol). Case reports and review papers were discarded. Nonunions due to previous surgical osteotomies (not fractures) were also discarded. Pediatric patients (less than 18 years old) were also discarded.

To identify potentially relevant documents, the following bibliographic databases were searched from 2000 to July 2025: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane review databases, and the Google search engine. The search strategies were drafted by consensus between authors. The PubMed (MEDLINE) search was done with the keywords “Subtrochanteric” AND “nonunion” between the years 2000 and July 2025. We also identified reports lacking the aforementioned keywords, but which were found while searching other identified reports. The final search results were exported into Zotero, and duplicates were removed.

A data-charting form was jointly developed by the authors to determine which variables to extract. The reviewers independently charted the data, discussed the results, and continuously updated the data-charting form in an iterative process.

We grouped the studies by the types of surgical procedure involved: implant, graft, osteotomy, reduction, and postoperative treatment. We also summarized the type of settings, populations, and study designs for each group, along with the measures used and broad findings. Where we identified a systematic review, we counted the number of studies included in the review that potentially met our inclusion criteria and noted how many studies had been missed by our search, adding them to it.

3. Detailed Surgical Technique

3.1. Patient Selection

This technique is intended for non-infected (aseptic) nonunions or loss of fixation (breakage, cut-out, or any other form) of subtrochanteric hip fractures. So, to indicate this technique, all these requirements must have been followed:

- a)

Subtrochanteric: Original fracture line in the area between the upper part of the lesser trochanter and 5 cms below the inferior margin of the lesser trochanter.

- b)

Nonunion: Original implant breakage or loss of original fixation at any time. Also, more than 6 months with pain on walking and no imaging signs of healing (X-ray or CT).

- c)

No infection present: C-reactive protein levels should be within normal levels. If a previous surgery was done less than 6 weeks before, two separate samples must show a decreasing value. No other clinical sign of infection (redness, pus, open wound) should be present.

3.2. Preoperative Planning

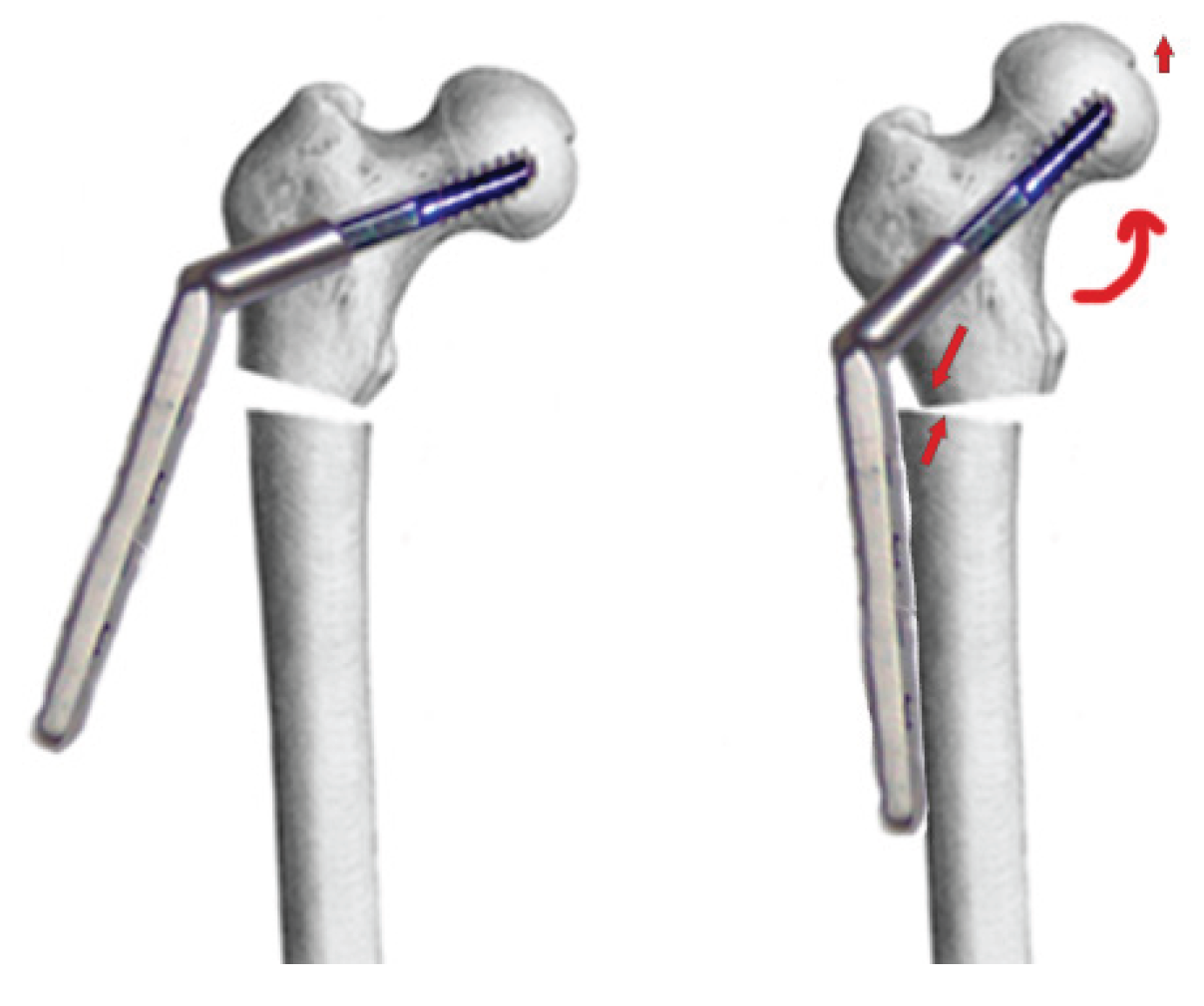

The goal of the surgical technique is to overcorrect the varus deformity to get a final 150º valgus angle at the femoral neck. It is also important that the distal part of the proximal side of the nonunion be in contact with the distal part (diaphyseal bone), to get a dynamic compression from the first postoperative day (

Figure 1).

The plate to use should be a DHS (dynamic hip screw, several trademarks sell it), with at least 4 holes, and an angulation of 135 to 150 degrees.

A radiographically calibrated image of the proximal femur of the patient should be used. An AP Pelvis X-ray should be taken with both knees in 15º of internal rotation. Over this template, measurements are done.

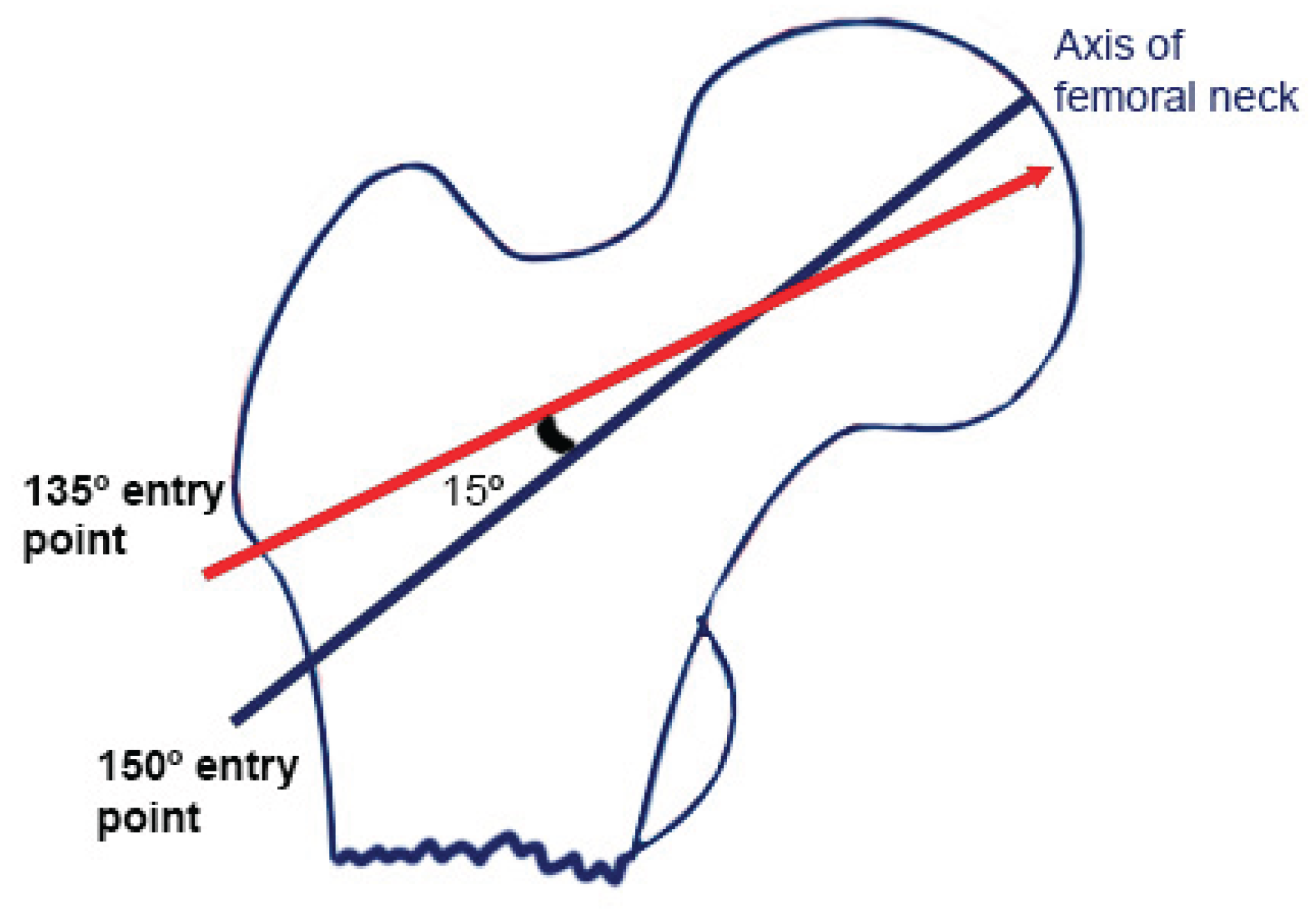

It is recommended to use a 135° plate. So, to get 150°, the path for the cephalic screw must be 15° of varus. The tip of the screw should be as near to the center of the hip as possible. Anyway, a slight downward position of the tip of the screw is possible (as seen in

Figure 1), if necessary, to avoid the same hole as the previous implant. If a 150° plate is used, one should follow the center of the axis of the femoral neck.

Lines are drawn as seen in

Figure 2. It is useful to measure the distance of the entry point to de tip of the greater trochanter, or the hole of the previous implant, or any other reference to be seen later on fluoroscopy. That will be the final position in AP view. In the lateral view, the screw should be just in the center (

Figure 2).

3.3. Patient Position

Preoperative antibiotics should be administered, as usual in the hospital (2gr cefazolin in our center). Anesthesia should be given to last at least two hours (mean duration of surgery is 112 min)[

6].

Patient is set in a traction table, and the limb is rotated 15º inward (referring to the intercondylar axis of the distal femur). This allows for a perfect AP view of the hip. No traction is given; the traction table is only necessary to hold the limb and to facilitate the approach to the hip.

Skin preparation is done as usual, and the patient is draped.

3.4. Implant Retrieval and Surgical Approach

Previous material should be retrieved using previous incisions. If a nail is broken inside the bone, some percutaneous techniques can be used to retrieve it[

8].

The surgical approach is a subvastus lateral approach. Incision is performed just lateral to the greater trochanter, going down for about 15 cm (

Figure 3). After skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised, the fascia lata is incised in line with the skin incision. Vastus lateralis is identified and separated from the linea aspera in the posterior part of the femur. A Hohmann retractor is set in order to separate de muscle anteriorly.

Three samples of the nonunion site are taken for microbiological study to rule out infection. If macroscopically signs of infection are detected now (pus, smell…), the technique should be aborted, nonunion debrided, and an external fixator used to provisionally fix de nonunion till infection is solved.

3.5. Head Preparation: Filling the Void and Insertion of the Cephalic Screw

There is a void in the previously retrieved cephalic screw of the blade. This void is worth filling to get a better purchase of the new screw. A 40-gr stick of allogenic trabecular bone is prepared as follows: the width of the previous hole is measured, and a trephine is used to get a barrel of the same width (

Figure 4). This is impacted in the hole with an impactor.

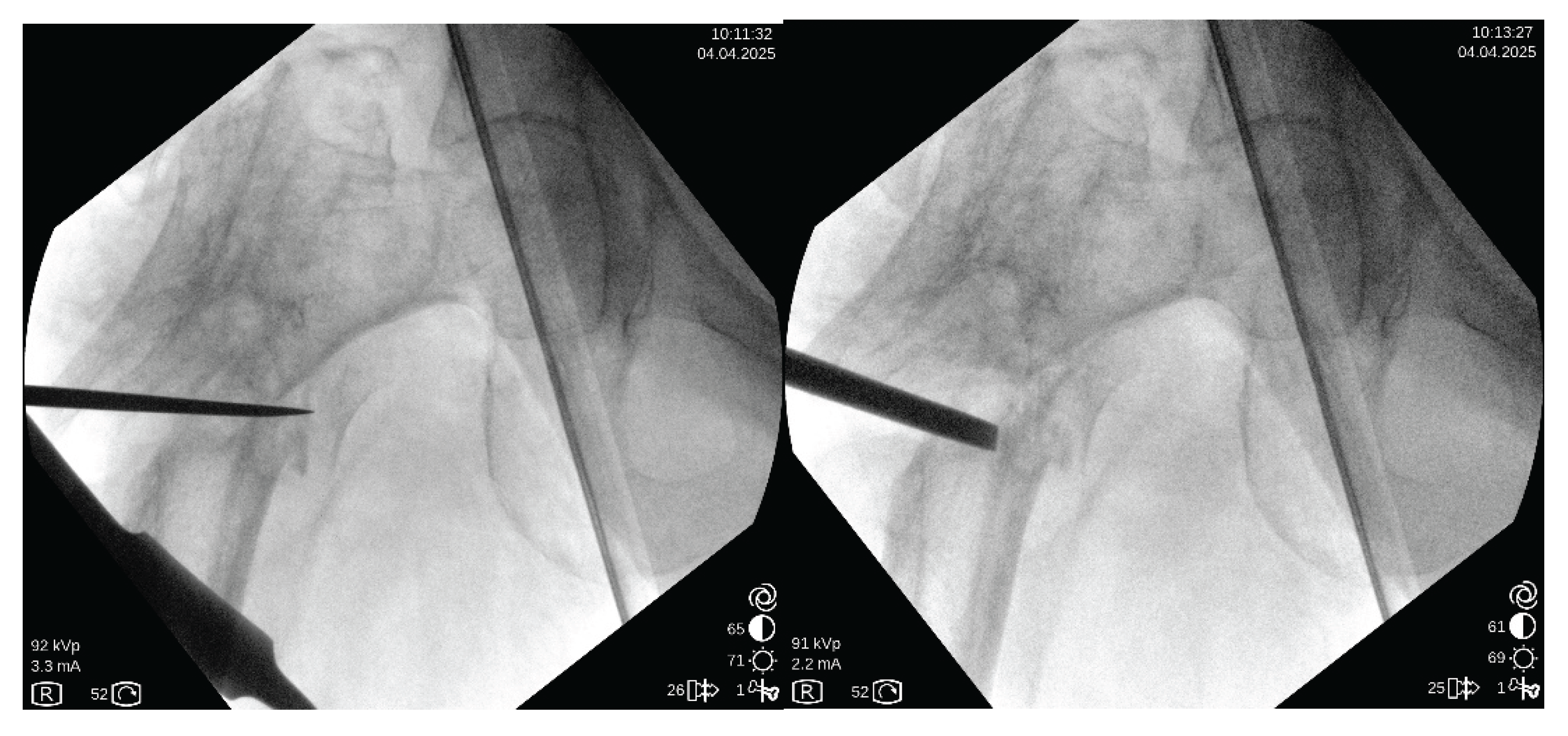

As previously planned, the guidewire is inserted in the femoral head as deeply as possible to get into the hard bone of the femoral head. After drilling, a cephalic screw of correct length is inserted.

3.6. Decompaction of the Nonunion Site

This is a key point. After identification of the nonunion site, a chisel is carefully inserted through the nonunion site. The idea is to decompact both fragments to be able to mobilize them later. Opening the medial space is quite important. Usually, it is not necessary to break the bone, but if any bar of bone is present, it can be broken with a chisel. Do not separate the periosteal envelope of the zone. It is also paramount not to violate the vascular flow to this area (

Figure 5). No bone graft is added, and no decortication is done.

3.7. Over-Valguization of the Nonunion

In this moment, the DHS is introduced to the previously introduced cephalic screw. To correct the position of the femoral head, the plate should be placed just over the diaphyseal bone. To accomplish this, a Lowman retractor is recommended. Softly, the retractor is tightened, and the plate comes to the diaphyseal bone, reducing the nonunion (

Figure 6).

3.8. Final Fixation and Wound Closing

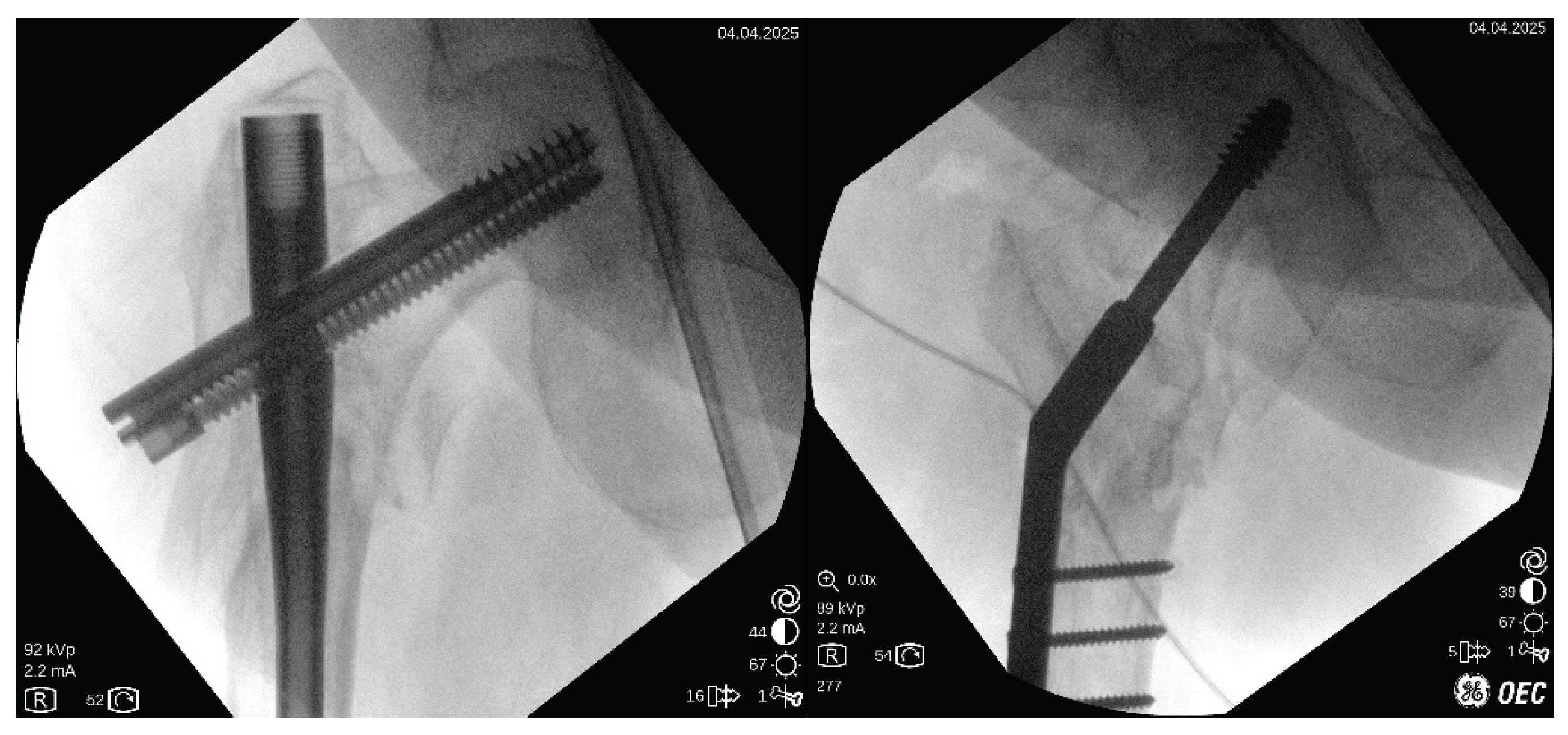

After plate gathering to the femoral shaft, 3,5 cortical screws are applied. It is recommended that at least 4 bicortical screws with good purchase be inserted. When a longer plate is applied, the more distal screw can be a monocortical screw to diminish stress at the distal tip of the plate.

Good purchasing is verified by moving the construct under fluoroscopic vision (

Figure 7).

The vastus is left in situ with no stitches. Fascia lata, subcutaneous tissue, and skin are closed in the usual fashion.

3.9. Postoperative Treatment

Immediate weight-bearing is allowed with crutches on the first postoperative day. No limitation on activities is given.

4. Review of Literature

Searching PubMed retrieved 347 results. A title search discarded 309 results, so 37 titles were available for further review. Review articles were also revised, and 2 citations were added to the search. EMBASE search added no papers to the search. Google search added 1 paper.

After careful review of full papers, 14 papers were discarded: 2 had mixed results with other pathologies, 4 did not focus on nonunion, 2 were commentaries on papers, and 8 were about femoral neck or shaft nonunion. So, finally, 24 papers were available for full scanning (

Table 1).

The overall quality of the papers was generally poor; 22 were retrospective case-series studies, with an evidence level of IV. Patients included in every study were generally low, between 2-136 (mean 23 patients). Criteria for nonunion were also quite variable, ranging from clinical or radiological criteria of nonunion from one year after fracture to 4 weeks after it.

4.1. Varus Correction

Nearly all papers agree that varus is quite important factor for nonunion. All scanned papers stated that varus was corrected somehow if it was present. Only one paper compared one group just adding a plate (without correction)(7 patients) versus changing nail and adding plate (12 patients)[

9]. Healing rates were better for the non-corrected group (100% versus 92%). Nevertheless, it is supposed that those patients were assigned to that group because no varus malalignment was found.

For varus correction, most papers do not perform osteotomy. They perform correction mainly by debridement of the nonunion zone and then valgus alignment of the proximal fragment. Open reduction is the most common system, but one paper performs it percutaneously[

10].

Many papers do not indicate the degree of correction. Many of them just state that a correction has been made. Most of them try to get the anatomical valgus compared to the contralateral side [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Only one paper states that an overcorrection to 150º valgus is the objective[

6].

In summary, there is wide agreement that an anatomical or slightly overcorrected valgus is necessary for good healing.

4.2. Shortening

This is a problem frequently found in clinical practice but, surprisingly, not registered in many papers. Twelve papers present the shortening of the cases before and after revision surgery[

6,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Most papers accept or even increase the leg length discrepancy. A final shortening of between 11-23 mm is commonly accepted[

13,

15,

16,

17].

Only four papers try to restore or at least diminish this leg-length discrepancy.

One way to achive this is by inserting bone graft. Wu et al[

18] designed a technique in which the nonunion area is distracted, and structural bone autograft from the posterior iliac crest is inserted. Finally, a nail is used to fix it. It is claimed to work fine for leg-length discrepancies of 2-5 cm, and a mean of 1 cm lengthening is described in their series of 21 patients, with 100% healing.

Other way to achieve lengthening of the shortened leg is through valguization. Kim et al[

21], using a 95º blade plate achieved a lengthening of about 7-9 mm just by correcting the valgus angle, and adding bone graft. El-Alfy et al[

20] also achieved increased leg length (up to 13 mm) through valguization of the proximal femur and adding bone graft. In both cases a static construction was performed. Delgado-Martinez et al[

6], performing a dynamic over valgus correction of the nonunion also achieved a mean leg lengthening of 8 mm in their series of 5 patients with 100% healing. No graft is used in his method[

6], avoiding the morbidity of the donor zone.

In summary, it is necessary to take into account the leg-length discrepancy and to try to correct it, if possible.

4.3. Debridement of Nonunion

Most papers do perform a debridement, or even a cortical delamination, in order to promote biological healing. It is difficult to ascertain if a nonunion in this zone is atrophic or hypertrophic. Some papers deal only with atrophic nonunions[

14], so the debridement and the addition of osteoinductive products (bone graft, RIA, BMPs, and so on) seem warranted. Most of them also use it to get correction of the varus deformity, but at the expense of increasing shortening[

13,

16,

17].

Two papers do not perform a debridement of the nonunion zone: De Biase et al[

25], in a case report of just two cases, state that it just opens the nonunion zone, without debridement. Delgado-Martinez et al[

6], in a 5-case prospective study, just opened de nonunion zone, without debridement. In both papers, healing achieves 100%.

In summary, if a nonunion is atrophic, it may be useful to perform debridement. For hyperthophic nonunions, it seems useless.

4.4. Bone Graft

Many types of bone grafts have been used. Autografts are usually preferred when available, due to their better osteogenic properties[

14]. Most papers use other grafts, mainly allografts, when an autograft is not available. Some papers use structural allografts[

24,

26]. RIA (reamer-irrigator-aspirator) from bone marrow from the same patient has also been used[

14,

27].

Just 4 papers claim not to use bone grafts in any case[

6,

22,

23,

25]. When comparing healing rates between the groups of patients, there is no clear advantage to using bone grafts. Healing rates in non-grafting papers range from 69-100% and grafting papers range from 84-100%.

In summary, it seems appropriate to use grafting in atrophic nonunions, but it does not seem useful in hyperthrophic nonunions.

4.5. Device: Dynamic or Static?

Several types of devices have been used to fix the nonunion zone. Most of them work in a static mode.

An intramedullary nail is the most common material used. It is claimed to ream the canal and to use a wider nail, to get better purchase[

4,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18,

22,

26,

28]. To get some correction of the varus, the medialization of the entry point has been marked as important. Some advancements have been published regarding this item, as the use of poller screws to help the nail maintain the entry point in a medial position (to avoid varus)[

10].

The addition of a plate to the intramedullary nail is another system to enhance fixation[

4,

12,

15]. Some papers just add a plate (3,5 or 4,5 locked plate) to the previous fixation if the position is acceptable[

4,

9,

12,

15].

The second most used implant is a blade plate of 95º or a Dynamic condylar screw (DCS) of 95º[

11,

13,

14,

15,

20,

23,

25,

26,

27]. It is used to fix the nonunion in a static mode. Some papers bend the plate to achieve some 100-120º of angulation of the plate[

13,

20]. Union rates range from 67-100%, but rates of complications (infections, loss of fixation, and so on) are higher than with the intramedullary nail. Nevertheless, the capacity to correct varus-valgus is greater.

Another implant used is the proximal femoral LCP plate[

19,

29]. It is quite similar to the blade plate or DCS, but more screws are anchored to the head of the femur. Similar results to those with the other extramedullary systems have been reported. A femoral locking compression plate placed in reverse has been also used[

30].

Only one dynamic system has been used in this indication[

6]. A dynamic sliding hip screw (DHS) of 135-150º. The nonunion zone is opened, the varus deformity overcorrected, and then fixed in a completely dynamic fashion, allowing the patients to bear weight from the first operative day. Even a few patients have been reported (5), results seem promising, with 100% healing and nearly no complications.

In summary, many systems to fix the nonunion have been reported. Intramedullary systems are the most commonly used and present fewer complications, but their capacity to correct varus deformity is limited. Extramedullary systems can be used to enhance or substitute the intramedullary nail, with a higher risk of complications. Extramedullary dynamic devices are promising.

4.6. Immediate Weight Bearing or Not?

Immediate weight bearing is important. As most of the patients are elderly, they can get a lot of complications due to long-term rest. Nevertheless, most papers do not allow the patients to immediately engage in full weight-bearing.

Many papers that use intramedullary fixation do promote immediate weight bearing[

10,

12,

17,

18]. It is considered a stable method of fixation, but not all intramedullary papers allow immediate weight bearing[

22].

Nevertheless, all papers using extramedullary fixation with a non-dynamic device, do avoid immediate weight bearing, in some cases waiting even 3 months[

14,

19,

20,

23,

25,

27,

29]. The extramedullary dynamic fixation (DHS) of Delgado-Martinez et al[

6] does permit and even enhance immediate weight bearing.

In summary, a device that allows weight bearing must be sought when fixing the subtrochanteric nonunion. Intramedullary devices and Dynamic DHS usually allow for achieving this goal.

5. Conclusion

To achieve healing in a subtrochanteric nonunion, it is paramount to correct varus-valgus deformity, and to correct leg-length discrepancy. It is also desirable to allow immediate weight bearing.

Many devices and systems have been used. If a nail can correct deformity, the implant is preferred by many. If not, an extramedullary device should be used. Graft is recommended only in atrophic nonunions.

A technique that can fully achieve all the requirements in all cases is the new dynamic technique explained here.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, Delgado-Martinez AD.; methodology, All authors.; validation, all authors.; data curation, Cañada-Oya H and Zarzuela-Jimenez C.; writing—original draft preparation, Delgado-Martinez AD.; writing—review and editing, Rodriguez-Merchan ED.; supervision, Delgado-Martinez AD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding.”

Acknowledgments

We thank the Spanish group of investigation into subtrochanteric nonunions for their valuable considerations regarding this paper. The group is formed by: Renovell-Ferrer P; Videla M; Murcia-Asensio A; Olias-Lopez B; Boluda J; Rodrigo A; Romero E; Ferrero F; Aguado H; Carrera I; Hernandez-Hermoso JA; Gómez-Vallejo J; Cano-Porras JR; Parron R; Delgado-Rufino FB. No GenIA has been used in any form for the preparation of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Sing C-W, Lin T-C, Bartholomew S, Bell JS, Bennett C, Beyene K, et al. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post-Fracture Treatment, and All-Cause Mortality. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2023;38:1064–75. [CrossRef]

- Garrison I, Domingue G, Honeycutt MW. Subtrochanteric femur fractures: current review of management. EFORT Open Rev 2021;6:145–51. [CrossRef]

- Lo YC, Su YP, Hsieh CP, Huang CH. Augmentation Plate Fixation for Treating Subtrochanteric Fracture Nonunion. Indian J Orthop 2019;53:246–50. [CrossRef]

- Lo YC, Su YP, Hsieh CP, Huang CH. Augmentation Plate Fixation for Treating Subtrochanteric Fracture Nonunion. Indian J Orthop 2019;53:246–50. [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis MJ, Kanakamedala AC, Egol KA. Management of Subtrochanteric Femoral Fracture Nonunions. JBJS Reviews 2020;8:e19.00143. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Martínez AD, Cañada-Oya H, Zarzuela-Jiménez C. Dynamic, Over-Valgus Correction Without Osteotomy for Nonunion of Subtrochanteric Hip Fractures Using a Dynamic Hip Screw. Applied Sciences 2025;15:1236. [CrossRef]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. [CrossRef]

- Tadros A, Blachut P. Segmentally fractured femoral Küntscher nail extraction using a variety of techniques. American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, NJ) 2009;38:E59-60.

- Kim J-W, Oh C-W, Park K-H, Oh J-K, Yoon Y-C, Hong W, et al. The role of an augmentative plating in the management of femoral subtrochanteric nonunion. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023;143:4915–23. [CrossRef]

- Yoon Y-C, Oh C-W, Kim J, Park K, Oh J, Ha S-S. Poller (blocking) screw with intramedullary femoral nailing for subtrochanteric femoral non-unions: clinical outcome and review of concepts. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022;48:1295–306. [CrossRef]

- Lotzien S, Rausch V, Schildhauer TA, Gessmann J. “Revision of subtrochanteric femoral nonunions after intramedullary nailing with dynamic condylar screw.” BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19. [CrossRef]

- Dietze C, Brand A, Friederichs J, Stuby F, Schneidmueller D, Von Rüden C. Results of revision intramedullary nailing with and without auxillary plate in aseptic trochanteric and subtrochanteric nonunion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022;48:1905–11. [CrossRef]

- De Vries JS, Kloen P, Borens O, Marti RK, Helfet DL. Treatment of subtrochanteric nonunions. Injury 2006;37:203–11. [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis PV, Ahmad MA, Mineo GV, Tosounidis TI, Calori GM, Kanakaris NK. Subtrochanteric fracture non-unions with implant failure managed with the “Diamond” concept. Injury 2013;44:S76–81. [CrossRef]

- Dheenadhayalan J, Sanjana N, Devendra A, Velmurugesan PS, Ramesh P, Rajasekaran S. Subtrochanteric femur nonunion - Chasing the elusive an analysis of two techniques to achieve union: Nail-plate fixation and plate-structural fibula graft fixation. Injury 2024;55:111462. [CrossRef]

- Kang, SH. Treatment of subtrochanteric nonunion of the femur: whether to leave or to exchange the previous hardware. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2013;47:91–5. [CrossRef]

- Barquet A, Mayora G, Fregeiro J, López L, Rienzi D, Francescoli L. The Treatment of Subtrochanteric Nonunions With the Long Gamma Nail: Twenty-Six Patients With a Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2004;18:346–53. [CrossRef]

- Wu C-C. Locked Nailing for Shortened Subtrochanteric Nonunions: A One-stage Treatment. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research 2009;467:254–9. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian N, Babu G, Prakasam S. Treatment of subtrochanteric fracture non unions using a proximal femur plate. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2016;6.

- El-Alfy B, Abououf A, Darweash A, Fawzy S. The effect of valgus reduction on resistant subtrochanteric femoral non-unions: a single-centre report of twenty six cases. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 2024;48:1105–11. [CrossRef]

- Kim SM, Rhyu KH, Lim SJ. Salvage of failed osteosynthesis for an atypical subtrochanteric femoral fracture associated with long-term bisphosphonate treatment using a 95° angled blade plate. The Bone & Joint Journal 2018;100-B:1511–7. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar MK, Tekin AÇ, Kir MÇ, Ayaz MB, Ocak O, Mihlayanlar FE. Nail breakage in patients with hypertrophic pseudoarthrosis after subtrochanteric femur fracture: treatment with exchanging nail and decortication. Acta Orthop Belg 2023;89:59–64. [CrossRef]

- Rollo G, Tartaglia N, Falzarano G, Pichierri P, Stasi A, Medici A, et al. The challenge of non-union in subtrochanteric fractures with breakage of intramedullary nail: evaluation of outcomes in surgery revision with angled blade plate and allograft bone strut. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2017;43:853–61. [CrossRef]

- Mardani-Kivi M, Karimi Mobarakeh M, Keyhani S, Azari Z. Double-plate fixation together with bridging bone grafting in nonunion of femoral supracondylar, subtrochanteric, and shaft fractures is an effective technique. Musculoskelet Surg 2020;104:215–26. [CrossRef]

- De Biase P, Biancalani E, Martinelli D, Cambiganu A, Bianco S, Buzzi R. Subtrochanteric fractures: two case reports of non-union treatment. Injury 2018;49:S9–15. [CrossRef]

- Rehme-Röhrl J, Brand A, Dolt A, Grünewald D, Hoffmann R, Stuby F, et al. Functional and Radiological Results Following Revision Blade Plating and Cephalomedullary Nailing in Aseptic Trochanteric and Subtrochanteric Nonunion. JCM 2024;13:3591. [CrossRef]

- Vicenti G, Solarino G, Bizzoca D, Simone F, Maccagnano G, Zavattini G, et al. Use of the 95-degree angled blade plate with biological and mechanical augmentation to treat proximal femur non-unions: a case series. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;22:1067. [CrossRef]

- Khanna A, MacInnis BR, Cross WW, Andrew Sems S, Tangtiphaiboontana J, Hidden KA, et al. Salvage of failed subtrochanteric fracture fixation in the elderly: revision internal fixation or hip arthroplasty? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2024;34:3097–101. [CrossRef]

- Mittal KK, Agarwal A, Raj N. Management of Refractory Aseptic Subtrochanteric Non-union by Dual Plating. IJOO 2021;55:636–45. [CrossRef]

- Patil SSD, Karkamkar SS, Patil VSD, Patil SS, Ranaware AS. Reverse distal femoral locking compression plate a salvage option in nonunion of proximal femoral fractures. IJOO 2016;50:374–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).