Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

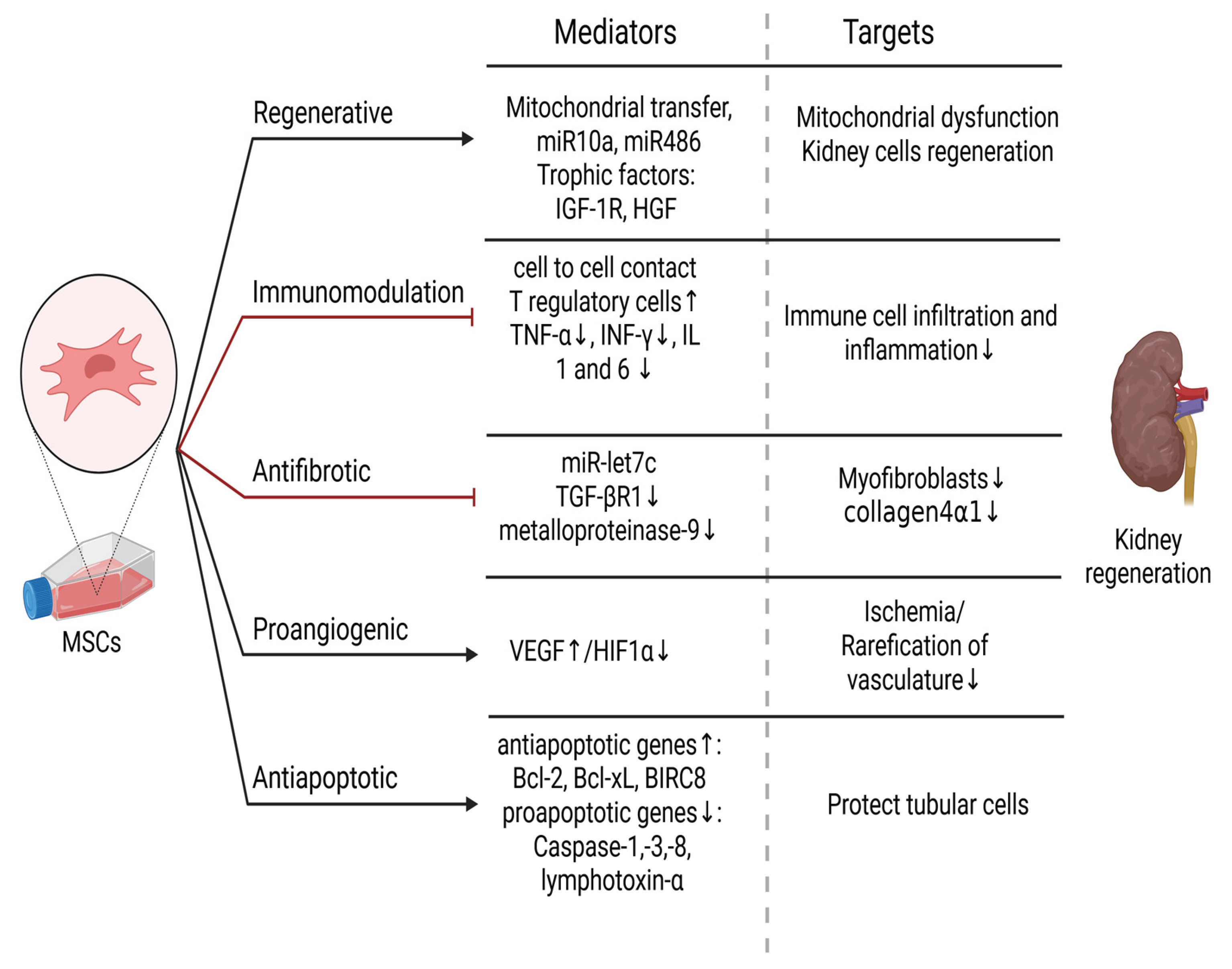

2. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Kidney Diseases

3. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Kidney Diseases

4. Assessment of Economic Potential of MSCs and iPSCs in Kidney Diseases

Conclusions

Author Contributions

References

- Francis et al., “Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus,” Nature Reviews Nephrology 2024 20:7, vol. 20, no. 7, pp. 473–485, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hewitson, T. D. “Renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis: Common but never simple,” Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, vol. 296, no. 6, pp. 1239–1244, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Salybekov, A.; Kinzhebay, A.A.; Kobayashi, S. Cell therapy in kidney diseases: advancing treatments for renal regeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 12, p. 1505601, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S. et al., “Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature,” Cytotherapy, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 1019–1024, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, E. M. et al. “Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement,” Cytotherapy, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 393–395, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Jeon, J. Kim, J. H. Cho, H. M. Chung, and J. Il Chae, “Comparative Analysis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Bone Marrow, Placenta, and Adipose Tissue as Sources of Cell Therapy,” J Cell Biochem, vol. 117, no. 5, pp. 1112–1125, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Kunimatsu et al., “Comparative characterization of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth, dental pulp, and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells,” Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 501, no. 1, pp. 193–198, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue under xeno-free conditions for cell therapy,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 6, no. 1, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Margiana et al., “Clinical application of mesenchymal stem cell in regenerative medicine: a narrative review,” Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2022 13:1, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–22, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Popielarczyk, W. R. Huckle, and J. G. Barrett, “Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Home via the PI3K-Akt, MAPK, and Jak/Stat Signaling Pathways in Response to Platelet-Derived Growth Factor,” Stem Cells Dev, vol. 28, no. 17, pp. 1191–1202, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Shahror, A. A. A. Ali, C. C. Wu, Y. H. Chiang, and K. Y. Chen, “Enhanced Homing of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 to Injury Site in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 20, no. 11, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Chen, C. Y. Lin, Y. H. Chiu, C. P. Chen, P. J. Tsai, and H. S. Wang, “IL-1 β-Induced Matrix Metalloprotease-1 Promotes Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration via PAR1 and G-Protein-Coupled Signaling Pathway,” Stem Cells Int, vol. 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Lotfy, N. M. AboQuella, and H. Wang, “Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–18, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Galipeau and L. Sensébé, “Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities,” Cell Stem Cell, vol. 22, no. 6, p. 824, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Birtwistle, X. M. Chen, and C. Pollock, “Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles to the Rescue of Renal Injury,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 22, no. 12, p. 6596, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Song, M. Scholtemeijer, and K. Shah, “Mesenchymal Stem Cell Immunomodulation: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential,” Trends Pharmacol Sci, vol. 41, no. 9, pp. 653–664, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Khwaja, “KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury,” Nephron Clin Pract, vol. 120, no. 4, pp. c179–c184, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Stevens et al., “KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease,” Kidney Int, vol. 105, no. 4, pp. S117–S314, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, M. Hanouneh, and C. E. Cervantes, “Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury: A Review of Current Approaches and Emerging Innovations,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, Vol. 13, Page 2455, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 2455, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Zeisberg and E. G. Neilson, “Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 1819–1834, 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Boor, T. Ostendorf, and J. Floege, “Renal fibrosis: novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets,” Nature Reviews Nephrology 2010 6:11, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 643–656, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., “Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous MicroRNA-let7c via exosomes to attenuate renal fibrosis,” Molecular Therapy, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 1290–1301, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Sean Eardley and P. Cockwell, “Macrophages and progressive tubulointerstitial disease,” Kidney Int, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 437–455, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- N. Li and J. Hua, “Interactions between mesenchymal stem cells and the immune system,” Cell Mol Life Sci, vol. 74, no. 13, p. 2345, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Mudrabettu et al., “Safety and efficacy of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells transplantation in patients undergoing living donor kidney transplantation: a pilot study,” Nephrology (Carlton), vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 25–33, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. English, J. M. Ryan, L. Tobin, M. J. Murphy, F. P. Barry, and B. P. Mahon, “Cell contact, prostaglandin E2 and transforming growth factor beta 1 play non-redundant roles in human mesenchymal stem cell induction of CD4+CD25Highforkhead box P3+ regulatory T cells,” Clin Exp Immunol, vol. 156, no. 1, p. 149, Apr. 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Gandolfo et al., “Foxp3+ regulatory T cells participate in repair of ischemic acute kidney injury,” Kidney Int, vol. 76, no. 7, pp. 717–729, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Jin, Y. Xie, Q. Li, and X. Chen, “Stem Cell-Based Cell Therapy for Glomerulonephritis,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2014, p. 124730, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Rampino et al., “Mesenchymal stromal cells improve renal injury in anti-Thy 1 nephritis by modulating inflammatory cytokines and scatter factors,” Clin Sci, vol. 120, no. 1, pp. 25–36, Jan. 2011. [CrossRef]

- U. Kunter et al., “Transplanted mesenchymal stem cells accelerate glomerular healing in experimental glomerulonephritis,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 2202–2212, 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Zedan et al., “Effect of Everolimus versus Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells on Glomerular Injury in a Rat Model of Glomerulonephritis: A Preventive, Predictive and Personalized Implication,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Gregorini et al., “Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody- associated renal vasculitis treated with autologous mesenchymal stromal cells: Evaluation of the contribution of immune-mediated mechanisms,” Mayo Clin Proc, vol. 88, no. 10, pp. 1174–1179, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Tapparo et al., “Renal Regenerative Potential of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from miRNA-Engineered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 20, no. 10, p. 2381, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Plotnikov, T. G. Khryapenkova, S. I. Galkina, G. T. Sukhikh, and D. B. Zorov, “Cytoplasm and organelle transfer between mesenchymal multipotent stromal cells and renal tubular cells in co-culture,” Exp Cell Res, vol. 316, no. 15, pp. 2447–2455, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou et al., “Exosomes released by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 1–13, Apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Perico, F. Casiraghi, and G. Remuzzi, “Clinical Translation of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies in Nephrology,” J Am Soc Nephrol, vol. 29, no. 2, p. 362, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Perico et al., “Safety and Preliminary Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell (ORBCEL-M) Therapy in Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial (NEPHSTROM),” J Am Soc Nephrol, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 1733–1751, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Stavas et al., “Rilparencel (Renal Autologous Cell Therapy-REACT®) for Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: Phase 2 Trial Design Evaluating Bilateral Kidney Dosing and Redosing Triggers,” Am J Nephrol, vol. 55, no. 3, p. 389, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. De Groot et al., “Uremia causes endothelial progenitor cell deficiency,” Kidney Int, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 641–646, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Tajiri et al., “Regenerative potential of induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients undergoing haemodialysis in kidney regeneration,” Scientific Reports 2018 8:1, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Caldas et al., “Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Reduce Progression of Experimental Chronic Kidney Disease but Develop Wilms’ Tumors,” Stem Cells Int, vol. 2017, no. 1, p. 7428316, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Shankar et al., “Kidney Organoids Are Capable of Forming Tumors, but Not Teratomas,” Stem Cells, vol. 40, no. 6, p. 577, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi et al., “Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells,” Cell Stem Cell, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 53–67, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Imberti et al., “Renal progenitors derived from human iPSCs engraft and restore function in a mouse model of acute kidney injury,” Sci Rep, vol. 5, p. 8826, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Toyohara et al., “Cell Therapy Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Renal Progenitors Ameliorates Acute Kidney Injury in Mice,” Stem Cells Transl Med, vol. 4, no. 9, pp. 980–992, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Araoka et al., “Human iPSC–derived nephron progenitor cells treat acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease in mouse models,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 17, no. 792, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. de C. Ribeiro et al., “Therapeutic potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells and renal progenitor cells in experimental chronic kidney disease,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Tsujimoto et al., “A Modular Differentiation System Maps Multiple Human Kidney Lineages from Pluripotent Stem Cells,” Cell Rep, vol. 31, no. 1, p. 107476, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Mae et al., “Expansion of Human iPSC-Derived Ureteric Bud Organoids with Repeated Branching Potential,” Cell Rep, vol. 32, no. 4, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Mae et al., “Generation of branching ureteric bud tissues from human pluripotent stem cells,” Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 495, no. 1, pp. 954–961. [CrossRef]

- T. Traitteur, C. Zhang, and R. Morizane, “The application of iPSC-derived kidney organoids and genome editing in kidney disease modeling,” iPSCs - State of the Science, pp. 111–136, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kishi et al., “Proximal tubule ATR regulates DNA repair to prevent maladaptive renal injury responses,” J Clin Invest, vol. 129, no. 11, pp. 4797–4816, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Ning, Z. Liu, X. Li, Y. Liu, and W. Song, “Progress of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Renal Organoids in Clinical Application,” Kidney Diseases, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Oishi, N. Tabibzadeh, and R. Morizane, “Advancing preclinical drug evaluation through automated 3D imaging for high-throughput screening with kidney organoids,” Biofabrication, vol. 16, no. 3, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Osafune, “iPSC technology-based regenerative medicine for kidney diseases,” Clin Exp Nephrol, vol. 25, no. 6, p. 574, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Darlington et al., “Costs and Healthcare Resource Use Associated with Risk of Cardiovascular Morbidity in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Evidence from a Systematic Literature Review,” Adv Ther, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 994–1010, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aghajani Nargesi, L. O. Lerman, and A. Eirin, “Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for kidney repair: current status and looming challenges,” Stem Cell Res Ther, vol. 8, no. 1, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Jha et al., “Global Economic Burden Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Pragmatic Review of Medical Costs for the Inside CKD Research Programme,” Adv Ther, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 4405–4420, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. T. J. Hickson, S. M. Herrmann, B. A. McNicholas, and M. D. Griffin, “Progress toward the Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Other Disease-Modulating Regenerative Therapies: Examples from the Field of Nephrology,” Kidney360, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 542–557, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Elshahat, P. Cockwell, A. P. Maxwell, M. Griffin, T. O’Brien, and C. O’Neill, “The impact of chronic kidney disease on developed countries from a health economics perspective: A systematic scoping review,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Cheng, S. Pan, and Z. Liu, “Stem cells: a potential treatment option for kidney diseases,” Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2020 11:1, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–20, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Vanholder et al., “Reducing the costs of chronic kidney disease while delivering quality health care: a call to action,” Nat Rev Nephrol, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 393–409, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Perico, F. Casiraghi, and G. Remuzzi, “Clinical Translation of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies in Nephrology,” J Am Soc Nephrol, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 362–375, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chen et al., “Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Kidney Diseases: Potential and Challenges,” Cell Transplant, vol. 32, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. E. Barry et al., “Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy compared to SGLT2-inhibitors and usual care in treating diabetic kidney disease: A cost-effectiveness analysis,” PLoS One, vol. 17, no. 11, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Silva, S. S. Rosa, J. A. L. Santos, A. M. Azevedo, and A. Fernandes-Platzgummer, “Enabling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Extracellular Vesicles Clinical Availability-A Technological and Economical Evaluation,” Journal of extracellular biology, vol. 4, no. 3, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Childs, S. Reid, M. Salmeron-Sanchez, and M. J. Dalby, “Hurdles to uptake of mesenchymal stem cells and their progenitors in therapeutic products,” Biochemical Journal, vol. 477, no. 17, p. 3349, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Russell, R. C. Lefavor, and A. C. Zubair, “Characterization and cost-benefit analysis of automated bioreactor-expanded mesenchymal stem cells for clinical applications,” Transfusion (Paris), vol. 58, no. 10, pp. 2374–2382, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. De Carvalho Ribeiro, L. F. Oliveira, M. A. Filho, and H. C. Caldas, “Differentiating Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells into Renal Cells: A New Approach to Treat Kidney Diseases,” Stem Cells Int, vol. 2020, p. 8894590, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Thanaskody, A. S. Jusop, G. J. Tye, W. S. Wan Kamarul Zaman, S. A. Dass, and F. Nordin, “MSCs vs. iPSCs: Potential in therapeutic applications,” Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 10, p. 1005926, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nießing, R. Kiesel, L. Herbst, and R. H. Schmitt, “Techno-Economic Analysis of Automated iPSC Production,” Processes 2021, Vol. 9, Page 240, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 240, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Kim, E. Kawase, K. Bharti, O. Karnieli, Y. Arakawa, and G. Stacey, “Perspectives on the cost of goods for hPSC banks for manufacture of cell therapies,” npj Regenerative Medicine 2022 7:1, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–8, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Mills, T. Donnelly, M. Brennan, and B. Marques, “Transitioning to Scalable Bioreactors for Allogeneic iPSC-Derived Cell Therapies: Cost Savings and Global Patient Access,” Cytotherapy, vol. 27, no. 5, p. S148, May 2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).